1. Introduction

During the late Qing and the Republican era of China, Chinese Buddhism encountered a dual crisis. Externally, this crisis was characterized by the loss of sovereignty, collapse of the traditional economic foundation, and social disorder stemming from colonial influences. Simultaneously, an internal crisis of cultural identity emerged, rooted in the disconnection between ancient and modern values and the collision between Chinese and Western civilizations. A more profound crisis was reflected in the modern deconstruction of the Buddhist value and belief system, representing a systemic dilemma for traditional civilization amid the processes of modernization. This situation was further exacerbated by the frequent destruction and expropriation of Buddhist temples, which served as the material carriers of religious connotations. As Hu put forward, “the dichotomy of ‘East and West’ and ‘tradition and modernity’, i.e., how to choose between ‘East and West’ and ‘tradition and modernity’, was a major issue that modern China pondered at the crossroads.” (

Hu 2024, p. 1). Following the Revolution of 1911 (辛亥革命

Xinhai geming), the Chinese Buddhist Community increasingly engaged with secular society. However, this interaction reflected an unavoidable paradox: Buddhism, in such a historical context, needed to leverage state power for institutional reforms while remaining cautious of the potential alienation of religious beliefs that could arise from excessive secularization.

Scholars have extensively examined the interplay—marked by both contention and dialectical tension—between reformist efforts toward disenchantment (dismantling anachronisms and responding to modernity) and traditionalist commitments to discipline preservation during the modernization of Chinese Buddhism in the Republican era. Facing a crisis in early 20th-century Buddhism, Taixu (1890–1947) proposed the theory of Humanistic Buddhism (人間佛教,

renjian fojiao), advocating a shift from “transcending the Three Realms” (出世超越三界,

chushi chaoyue sanjie) to “purifying the human realm through worldly engagement” (入世净化人間,

rushi jinghua renjian). This represented a deliberate disenchantment of rigid, dogmatic religious paradigms, aiming to realize Buddhist ideals within secular society, exemplified by his vision of establishing a Pure Land on Earth (

Kieschnick 1999). As the leading reformist, Taixu sought to eradicate superstitious practices and world-renouncing tendencies, realigning Buddhism with the demands of modern society. He criticized traditional Buddhism‘s excessive focus on “post-mortem concerns”, urging a reconstruction of Buddhist doctrine (教理,

jiaoli), institutions (教制,

jiaozhi), and property management (教產,

jiaochan) through scientific rationality. Among these efforts, monastic robe reform was integral to his institutional restructuring (

Shengkai 2014). Traditional monastic communities vehemently resisted Taixu‘s reforms, viewing them as a threat to the core foundation of Buddhism, particularly monastic discipline and community (

saṃgha, 僧伽,

sengqie) authority (

Sueki 2010). Subsequent radical reformists, however, exacerbated tensions by advocating wholesale rejection of tradition and uncritical adoption of Western models (

Yuan 1923). As Qiuyu Yu (

Yu 2000) observed, “Conservative and radical positions exist on a spectrum—from extreme conservatism (rejecting all change) to extreme radicalism (demolishing all existing structures).” A critical distinction emerged in practice: “worldly engagement” (入世,

rushi—infusing society with Buddhist wisdom) versus “secularization” (俗化,

suhua—eroding religious sanctity). While Taixu insisted on preserving the essence of discipline, radical factions risked desacralization through excessive accommodation (

Hong 2024). Nevertheless, since the reformism was led by Taixu, its problems were inadvertently shifted onto him, which not only obscured a fair evaluation of alternative modernization paths but also deepened factional divides (

Li 2022). Both traditionalist and reformist factions during the Republican era ultimately shared a common goal: to transform secular society through Buddhism, rather than to secularize Buddhism itself. The key to Buddhist modernization thus lies in negotiating the tension between disenchantment and discipline preservation. Striking a balance between these two required upholding monastic discipline without lapsing into uncritical traditionalism and engaging with society while resisting excessive secularization. The debates over Han Chinese Buddhist monastic robe reform (漢傳佛教僧服改式之爭,

Hanchuanfojiao sengfu gaishi zhizheng) offer a particularly concrete and visible manifestation of this dialectic and its inherent dilemmas.

Raoul Birnbaum emphasized that “Buddhists were not separated from the political, social, and intellectual transformations in the air at this time, and from various angles these individuals collectively produced a creative restatement of Chinese Buddhist life.” (

Birnbaum 2003, p. 431). In the reform movement of Chinese Buddhism, the controversy surrounding monastic robe reform deeply reflected the intricate interplay between tradition and modernity. As Raoul Birnbaum stated, “The responses of this cohort group to the particular challenges of the age may be set into two distinctive categories. an approach powerfully framed within traditional discourse that in some ways may be viewed as ‘fundamentalist’, and a call for comprehensive reform that conscientiously embraces the ‘fundamentalist’ approach. for comprehensive reform that consciously embraced a certain vision of modernity.” (

Birnbaum 2003, p. 433)

Taixu’s monastic robe reform illustrates the inherent tension between traditional precepts and contemporary adaptability. He safeguarded the fundamentals of the Buddhist discipline through the principle “Follow the Buddhist monastic discipline (遵佛制

zun fozhi)” (

Taixu 2004i, On Organizing the Community System 整理僧伽制度論, p. 152) while simultaneously facilitating localized adaptation. This dual institutional reconstruction not only reflects the superficial significance of robe modification but also signifies a systematic innovation in the modern transformation of the Buddhist discipline.

In particular, Birnbaum noted that “he provides more than enough encouragement by his repeated creation of ‘world-wide’ or national Buddhist associations of very modest membership in which he was a principal officer, or his various grand schemes for a tightly controlled clergy that would wear the new vestments of his design.” (

Birnbaum 2003, p. 436). By integrating organizational reconfiguration with image rebranding, Taixu aimed to strengthen the organizational discipline within the Community through the revitalization of the visual symbol system. However, deep divisions emerged among the reformers regarding the scope of the reform: moderates, represented by Yinshun 印順, advocated for improvement within the framework of the traditional Dharma robe, while radicals, represented by Lengjing 楞鏡, called for comprehensive modernization. These proposals encountered strong opposition from traditionalist monks, who countered by reviving the ancient system and emphasizing the sanctity of the

kāṣāya (袈裟,

jiasha, monastic robe).

However, research on Chinese Buddhist monastic robes has largely concentrated on the textual and historical examination of the evolution of their forms and systems. For instance, Shuja Zhou 周叔迦 (

Zhou 2004) employed textology to trace the origins and transformations of the monastic robe system. His study revealed the ritual adaptations and functional transformations that accompanied the Sinicization of Buddhist monastic robes, thereby establishing a historiographical paradigm for subsequent research. Yong Fei費泳 (

Fei 2012) systematically constructed a framework for distinguishing the forms of Buddha’s robe and monks’ robe through an in-depth interpretation of Buddhist classics. Yuexin Chen 陳悅新 (

Chen 2009) clarified the institutional boundaries of religious clothing from a semantic perspective and outlined the normative framework for robe reform to adhere to the dual system of “Dharma robe and regular robe”. Japanese scholar Yoshimura Ryo吉村憐 (

Yoshimura 2005) identified the Chinese monastic robe system of “partial robe (部分长袍,

bufen changpao), straight robe (直裾深衣,

zhiju shenyi)”. North American scholar John Kieschnick (

Kieschnick 1999) interpreted the essence of Taixu‘s robe reform as a reconstruction of religious identity within the context of colonial modernity. In contrast, Huawen Bai (

Bai 1998) and Shengkai 聖凱 (

Shengkai 2001) uncovered the functional symbiosis between the forms of monastic robe and religious rituals from the perspectives of Vinaya studies and Buddhist liturgy. Huizhen Guo 郭慧珍 (

Guo 2001) advocated for the functional transformation of the “

tricīvara (三衣,

sanyi)” system in contemporary contexts. Their typological analyses under the ritualization of Dharma robes and functionality of regular robes have provided a critical categorical framework for the whole controversy.

While numerous papers have touched upon topics related to the controversy of monastic robe reform, few have provided specialized discussion and in-depth analysis. However, it is essential to focus on the controversy surrounding the reform in a targeted manner. This issue serves as a microcosmic lens for observing the broader modernization of Chinese Buddhism, encapsulating the identity anxiety arising from the collision between Eastern and Western cultures. Furthermore, it touches upon the perennial tension between religious sanctity and secular adaptability. The controversy over the modification of monastic robe, which spanned more than two decades, reflected a threefold division of Buddhism during the Republican era: the traditionalists upheld the ancestral view that “the inheritance of the Buddhist principles should not be violated; the reformers advocated for functional modifications, asserting that the tricīvara not be changed, while the regular uniforms should evolve with the times”; the radicals sought to achieve a modern integration of “Dharma robe and regular robe” through the concept of desacralization. Essentially, all factions explored how the material representation of Buddhist identity could be reconciled with the demands of modern society. Therefore, the controversy surrounding the monastic robe reform was not merely a localized phenomenon in the history of religious clothing but rather a critical entry point for understanding the modern transformation of Chinese Buddhism, warranting systematic analysis and in-depth study.

2. Buddhist Monastic Robes and Their Localized Evolution

To discuss the issues related to the conversion of Buddhist monastic robes and associated controversies during the Republican era, it is essential to first clarify the original monastic robe codes and trace the historical evolution of the robe in Chinese Buddhism. As John Kieschnick noted, “The monastic robes were just as important as a mark of distinction in China as they were in India” (

Kieschnick 1999, p. 11). However, during the process of Sinicization, both the Dharma and regular robes transformed across different periods and regions, while the core spirit of the Buddhist tradition persisted in various forms.

- (1)

Buddhist Monastic Robes

Buddhist monastic robes are traditionally divided into two categories: Dharma robes and regular robes. The Dharma robes, commonly known as the

tricīvara, consist of the outer robe (

saṃghāṭī, 僧伽梨,

sengqieli), the upper robe (

uttarāsaṃga, 鬱多羅僧,

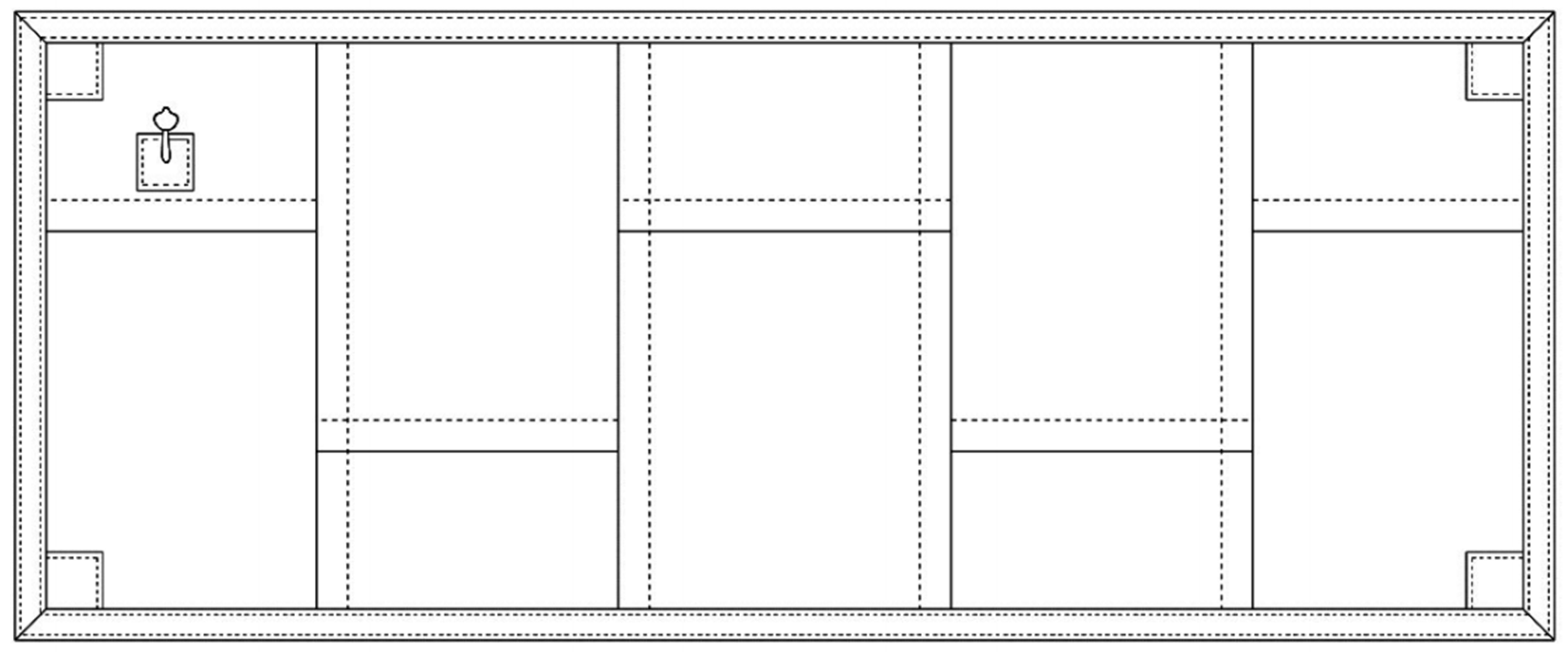

yuduoluoseng), and the lower robe (

antarvāsas, 安陀會,

antuohui).

Tricīvara not only serve to identify the monks but also embody the essence of the Buddha’s teachings, possessing the “great power to propagate the Dharma and to benefit living beings” (

Taixu 2004b, p. 121). These robes adhere to specific rules and regulations. In what follows, their characteristics will be discussed in terms of style, material, color, and function.

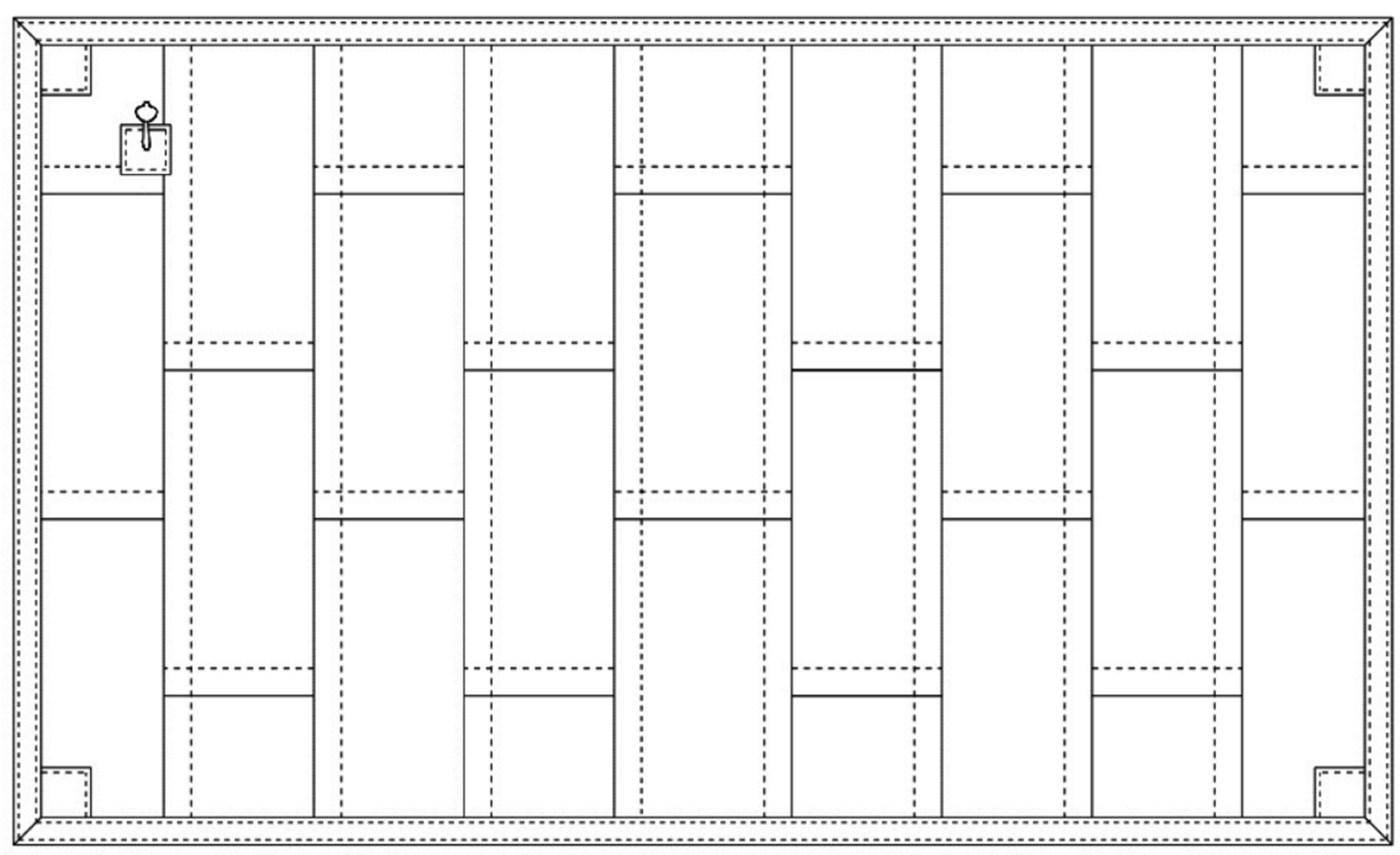

From a stylistic perspective, the outer robe, commonly referred to as the nine-stripe robe (九條衣,

jiutiaoyi), is a symbol of the fully ordained monk (

bhikṣu, 比丘,

biqiu). Wearing these robes during major pujas (a worship ritual performed by Hindus) cultivates public respect, as the Buddha proclaimed: “The great field of merit robe brings ten blessings. While regular clothing stirs desire, but Dharma robe can conceal the world’s shame, and is perfected to give birth to the field of blessings.” 大福田衣十勝利,世間衣服增欲染,如來法服不如是。法服能遮世羞恥,慚愧圓滿生福田。 (

Bore 1988, p. 314). The upper robe, also known as the seven-strip robe (七條衣,

qitiaoyi) (

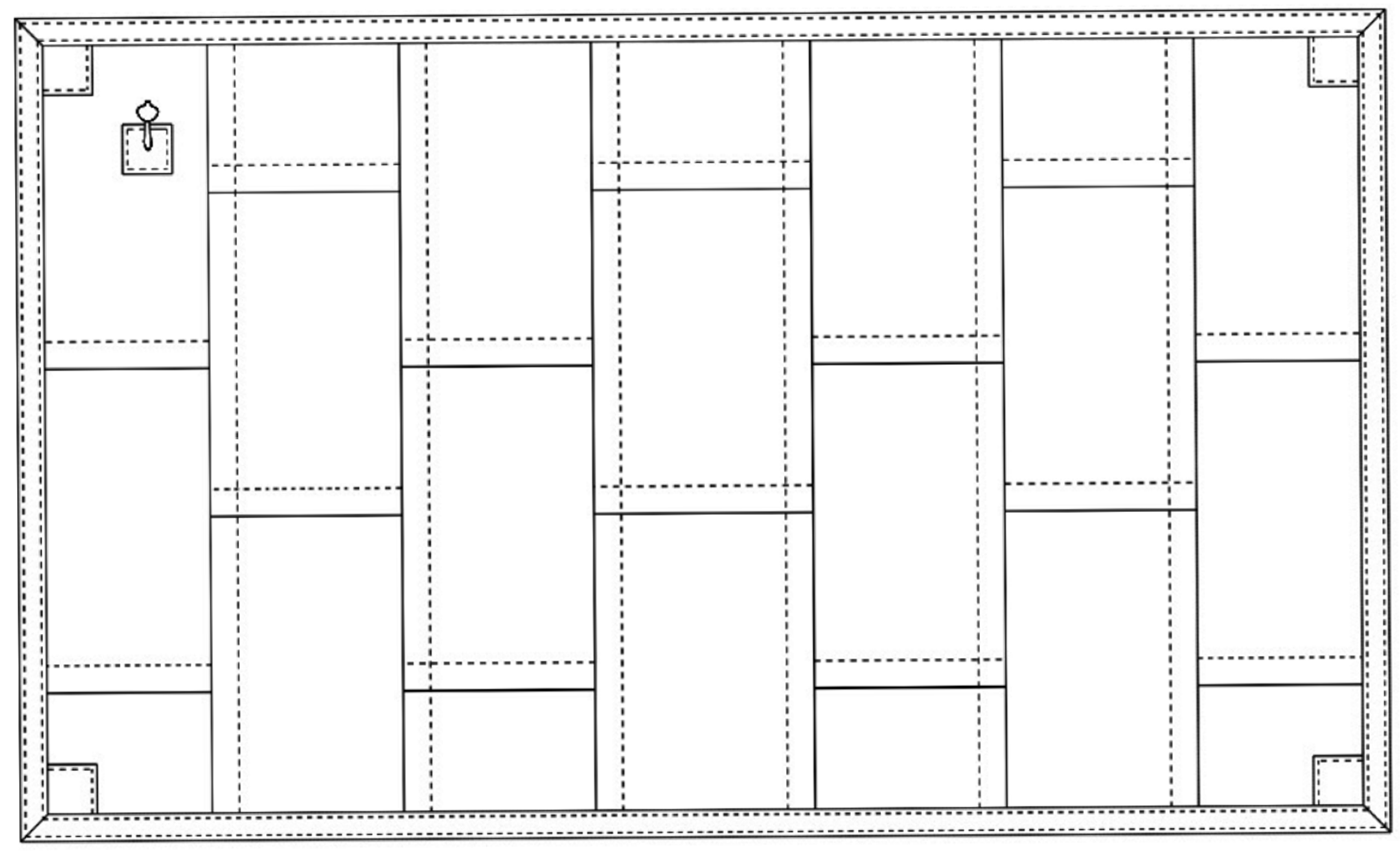

Figure 1), is donned by fully ordained monks during sutra recitation and worship, providing greater convenience than the outer robe while preserving dignity. The lower robe, also referred to as the five-strip robe (五條衣,

wutiaoyi) (

Figure 2), or the work robe (作务衣,

zuowuyi), is worn during daily tasks.

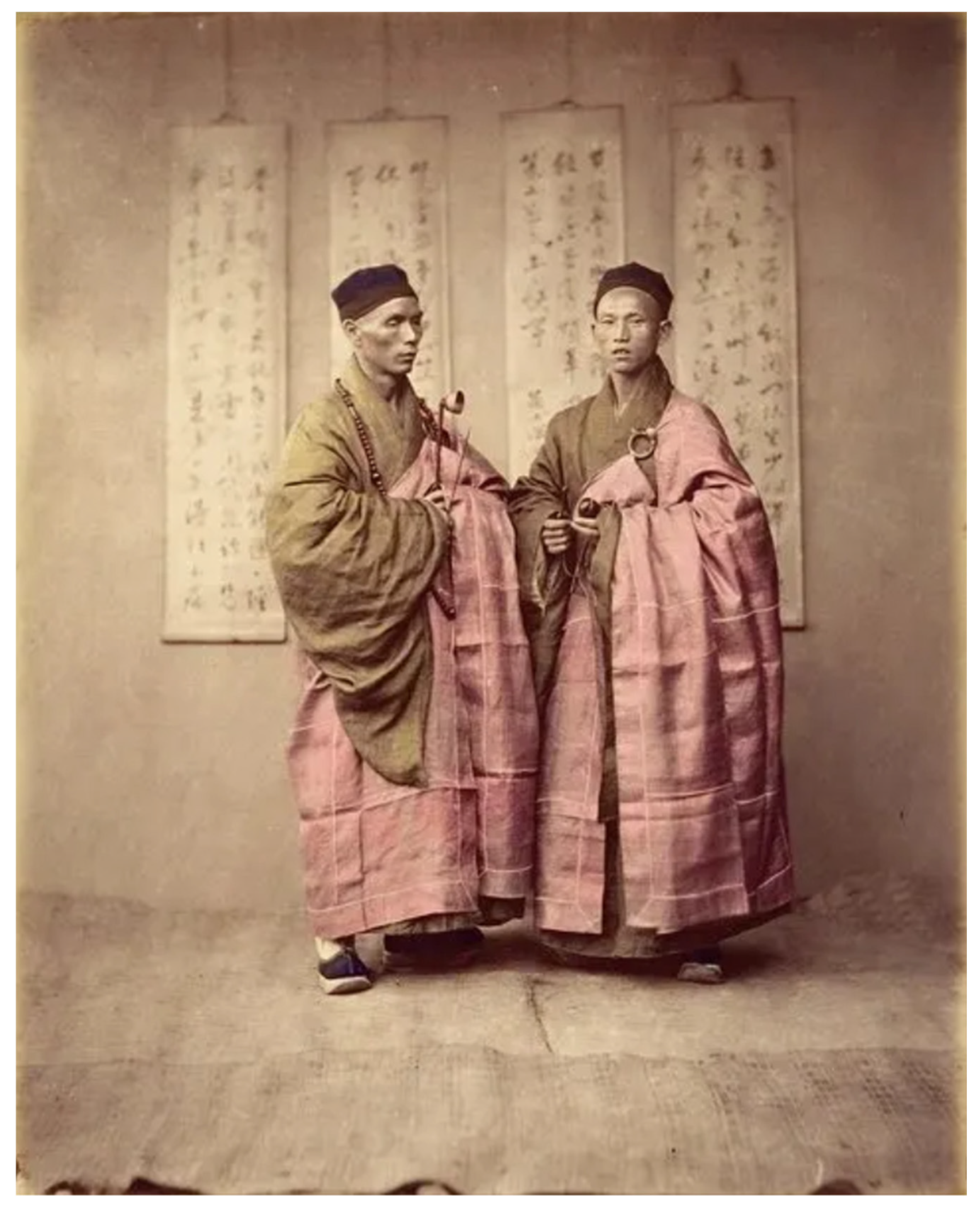

From a material perspective, early Buddhist robes were primarily constructed from a range of materials, including bark, bird feathers, wool, cotton, hemp, and silk, which were sewn together (

Figure 3). Monks predominantly utilized discarded rags, commonly referred to as “dung sweeping robes (糞掃衣,

fensaoyi)” or “ragged robes (百衲衣,

bainayi)” collected from refuse. This practice was instituted by the Buddha to curb the monks’ desire for extravagant garments and to conserve material resources.

In terms of color, the patchwork nature of discarded fabrics made color uniformity difficult. As a result, the Sanskrit term

kāṣāya connotes “impure color”, “abnormal color”, or “tarnished color”. The Buddha articulated that “the abnormal color corresponds to the Buddha’s teachings” 壞色與道相應 (

Kumārajīva 1988, p. 1008). Consequently, the term specifically denoted a mixed hue resembling taupe, which served to dissuade monks from coveting decorative robes.

From a functional perspective,

tricīvara can be collectively referred to as Dharma robes. Only

bhikṣu and

bhikṣuṇī who have received the full precepts are permitted to wear these robes, marking their status. Monks adorned in the

tricīvara are empowered to propagate the Buddha’s teachings on his behalf and are eligible to receive offerings from sentient beings, which serves as a blessing for all. Consequently, the

tricīvara created by the Buddha are described as “having the appearance of a field, and are therefore called the robes of the blessing of the field 皆有田相, 故謂之福田衣” (

Taixu 2004i, On Organizing the Community System 整理僧伽制度論, p. 150).

Buddhist Dharma robes are governed by clearly defined regulations. Although the external forms of these Dharma robes have evolved over time and across different regions since their introduction to China, the essential spirit of the Buddha’s teachings embodied in these robes has remained unchanged.

- (2)

Localized Evolution of Buddhist Monastic Robes

After the transmission of Buddhism into China, “especially after the Dao’an period, monks generally adhered to the Buddhist scriptures and precepts; the alms bowl and

tricīvara never left the body, which became the norm for all monks.” (

Taixu 2004f, Tang Dynasty Zen and Modern Thought 唐代禪宗與現代思潮, p. 191). Over time, the form, material, color, and function of Chinese Buddhist monastic robes underwent adaptations due to a variety of factors, including political influence, climate, and local customs. However, as Shengyan said, “The text of the precepts may reflect its own time and place, but the fundamental spirit of the precepts never ages.” (

Shengyan 2010b, The Unification and Improvement of Monastic Robes 僧裝的統一與改良, p. 147)

In terms of form and function, the

tricīvara took on an even more pronounced role in signifying monastic identity after being introduced to China. In terms of sewing style, each of the

tricīvara is divided into three grades and nine levels, symbolizing the seniority of the monks. However, Taixu emphasized that “The

saṃghāṭī is correct with nine strips.” 僧伽梨以九條為正 (

Taixu 2004i, On Organizing the Community System 整理僧伽制度論, p. 149). In contemporary times, however, the significance of this practice is largely misunderstood, as many perceive the number of strips to correlate with higher value. Consequently, they mistakenly regard the twenty-five strips as the standard for high-level uniform, which reflects a fundamental misconception.” (

Taixu 2004i, On Organizing the Community System 整理僧伽制度論, p. 149). He further proposed that “the lower seat should wear a five-stripe robe, the middle seat the seven-strip robe, and the upper seat the nine-strip robe (

Figure 4), then the sequence of the precepts receiving can be seen at a glance. If one practiced special Dharma deeds, then both the lower and middle seats could wear seven- or nine-strip robes” (

Taixu 2004i, On Organizing the Community System 整理僧伽制度論, p. 150). In Taixu’s view, during the Buddha’s time, robe strips were randomly picked up and used to sew the robe. Different numbers of strips of robes were sewn to differentiate the status of the Community; however, the three shapes of Dharma robe, namely five, seven, and nine-strip robes, were sufficient, and further subdivisions were unnecessary.

From the perspective of the colors of the

tricīvara, although the Buddhist system prohibits the use of orthodox colors such as green, red, yellow, white, and black, the colors of the

tricīvara in Chinese Buddhism are quite diverse. Historical records indicate that during the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties, Dharma robes predominantly featured “non-orthodox colors”. In the Tang and Song Dynasties, the imperial court frequently bestowed purple and scarlet

kāṣāya to monks as a mark of honor. Additionally, during the Yuan Dynasty, the practice of bestowing yellow

kāṣāya became more prevalent, resulting in Dharma robes appearing in purple, scarlet, yellow, and other colors. During the Hongwu洪武 period of the Ming Dynasty, regulations were established regarding the colors of monk robes. These regulations categorized the uniforms into three distinct types based on their functions: Meditation (Zen), Lecture, and Teaching. Zen monks were required to wear tea-brown regular robes with green tapes and jade-colored

kāṣāya; lecturing monks donned jade-colored regular robes with green tapes and light red

kāṣāya; and teaching monks wore soapy-colored regular robes with black tapes and light red

kāṣāya (

Lin 1620, 林堯俞: Ritual Department Zhi Gao 禮部志稿, p. 302). By the late Ming Dynasty, the rigidity of the color system weakened. For example, lecturing monks wore blue and teaching monks appeared in onion-white

kāṣāya and other variations (

Zhou 2004, A Study of Han Chinese Monastic Robes, p. 723). Since the Qing Dynasty, the common monk robe primarily featured colors such as brown, yellow, black, and gray, while

kāṣāya included shades of yellow, red, and light yellowish green. During the Republican era, the palette of monk robes became even more diverse. Yinshun emphasized that the robe of the time had become “a mess of different colors” 服色紛亂 (

Yinshun 2009a, A Discussion of the Dyeing of Monastic Robes -Written for the Unification Movement of the Color 僧衣染色的論究——為服色統一運動而寫, p. 46). As for the “abnormal color”, the later interpretive practice known as the “dotting for purity” 点净 involved the use of non-orthodox color ink on the solid color of the Dharma robes, which were dotted with color dots to symbolize that the uniforms are regulated according to the “abnormal color”. The

Mahāsaṃghika-Vinaya (摩訶僧祇律,

Mohe Sengqi Lv) states, “The largest dots are the width of four fingers, and the smallest like peas. … Dotting shall not be done in parallel, or one, three, five, seven, or nine; they shall not be done in the shape of a flower.” (

Buddhabhadra and Faxian 1988, p. 369). The shape, color, and function of the

tricīvara have undergone significant localization in China, with the transformation of regular robes being more pronounced.

As early as the Eastern Wei, the monk—official Fashang 法上 (495–580) stipulated that the style of the regular robes should be distinguished from the clothes of the laypeople. During the Sui and Tang dynasties, the types of regular robes became increasingly diversified. By the Song and Ming dynasties, the haiqing 海青—an outer robe inspired by traditional Han Chinese clothing— had become a robe commonly worn by monks during puja. Since Haiqing is not classified as a Dharma robe, it could be worn by both monks and Lay Buddhists居士 during formal gatherings to show uniformity. In the Qing Dynasty, the state mandated Manchu-style clothing (滿族服飾) for laypeople; however, monks were allowed to retain the Han-style robe of the Ming era to distinguish themselves from the secular society.

Despite evolving over time, Chinese Buddhist monastic robes remain distinct from the clothing of laypeople, becoming a customary dress code for monks.

3. Three Major Propositions on the Buddhist Monastic Robe Reform in the Republican Era

During the Republican era, the strong impact of Western culture transformed deeply rooted traditional Chinese concepts, and monks were not exempt from this influence. As suits became fashionable, some monks lamented that the traditional monastic robes were outdated, and thus, the change in robes became a significant aspect of Buddhist reform.

- (1)

Preservation of Traditional Dharma Robes and Adaptive Modification of Regular Robes

As a leader of Buddhist reform, Taixu was the first to call for the robe reform. However, his proposals were cautious. Initially, he considered “reforming the robe to a simpler style and adopting the Japanese

kāṣāya as the regular robe to refresh the society’s perception towards monks” 改制簡潔的冠服,仿用日本方便袈裟為常禮服, 一新世人對於僧徒的觀感 (

Taixu 2004e, Autobiography of Taixu 太虛自傳, p. 278). However, this idea was not fully developed and ultimately not implemented. Later, he suggested that “except for the

kāṣāya and straight robes, other items may also follow the prevailing social norms” (

Taixu 2004d, Submission to the National Federation of Branch Departments of the General Buddhist Association 上佛教總會全國支會部聯合會意見書, p. 292). Over time, Taixu’s opinion became increasingly clear. Eventually, he concluded that “the great

kāṣāya must follow the Buddhist system” (

Taixu 2004c, Removing Several Errors of the Young Monks 去除稚僧的幾種錯誤, p. 115) and further emphasized that “although there is no need to be conservative about the regular robes, the monk robe should be different from that of the laypeople.” 常服雖無保守之必要,但僧服應與通俗不同 (

Taixu 2004c, Removing Several Errors of the Young Monks, p. 115).

Concerning the reform of regular robes, Taixu advocated for them to be “altered to suit contemporary times” (

Taixu 2004h, The First Epistle with Cihang 與慈航書一, p. 116), but he also stressed that these changes should be “carefully considered and not altered easily” (

Taixu 2004c, Removing Several Errors of the Young Monks, p. 115). Taixu designed a new style of regular robe that resembles a Chinese long gown but is slightly shorter in length. This design takes the form of a knee-length, button-down tunic with a collar made from two overlapping pieces of fabric. It featured openings for ventilation on both sides of the hem, and the front included four close-fitting pockets positioned at the top, bottom, left, and right. Initially, this robe was referred to as “Taixu long gown” 太虛褂 due to its endorsement by Master Taixu, it was later renamed the “

Arhat long gown” 羅漢褂. (

Shengkai 2001, p. 142) Taixu also designed a set of “short shirt and pants”短衫褲, commonly known as the “monks’ short set”僧短衣. The shirt’s upper body extends just above the hips, with a Chinese-style stand-up collar, two pockets at the lower end. The pants are made from the loose-fitting fabric typically worn by the populace and must be tied tightly at the ankle. Taixu actively promoted this robe to the Community Ambulance Corps:

“When I initially advocated for the establishment of the Community Ambulance Corps, I proposed that they wear the traditional ‘short set’ worn by monks, which would differentiate the corps from conventional military style and make it immediately recognizable as a community organization.” (

Taixu 2004a, Serving the Nation and Promoting Buddhism 服務國家宣揚佛教, p. 384)

Taixu advocated for all Community Ambulance Corps to adopt the “monks’ short set” as their uniform, not only for the convenience of ambulance service but also to convey Buddhism’s image of compassionate relief to the world. However, at that time, it was challenging to standardize all uniforms across various locations. In June 1946, during a training class for the Chinese Buddhist Association held at Jiao Shan Buddhism Academy, Taixu further promoted the change in monastic robe and wrote to Zhifeng 芝峰, stating that “The monastic robe of the training class are a creation for trial use. However, it is a special robe that was created and is not the same as the laypeople’s clothing.” (

Taixu 2004h, The First Epistle with Cihang 與慈航書一, p. 116). However, this trial and promotion did not have a significant impact due to differing views among the training class members.

Taixu’s advocacy of “Dharma robes adhering to the monastic discipline and regular robes being reformed at appropriate times” represents a prudent approach. Its purpose is to enable monks to better integrate into society, serve the nation, promote Buddhism, and lead all sentient beings toward enlightenment.

- (2)

Weakening of Dharma Robes and Modification of Regular Robes

Dongchu’s proposal for reforming the style of Dharma robes was even more radical than that of Taixu. After the victory in the Anti-Japanese War in 1946, Dongchu, who was the abbot of Dinghui Temple 定慧寺 in Jiaoshan 焦山 by then, seized the opportunity provided by the establishment of the “Chinese Buddhist Organizational Committee” 中國佛教整理委員會 to publish “

Reform of monastic robe and Enhancement of formal clothing” 改革僧裝與提高禮服 in

Haichao Yin 海潮音 (

Dongchu 2006). In this article, Dongchu argued for a comprehensive transformation of the monastic robe in an attempt to revolutionize the image of the Community.

Several of Dongchu’s points are worth noting: First, when referring to monks wearing traditional Han Chinese clothing, he was speaking of what Taixu called regular robes. Second, amidst the call for complete westernization during the Republican era, the perception of tradition as a form of backwardness influenced some monks. Third, Dongchu believed that Buddhism’s failure to integrate into society and the limited social participation of monks were largely due to their distinctive clothing. He therefore saw urgent reform of the monastic robe as essential to overcoming the social alienation caused by these outdated appearances. Consequently, Dongchu proposed a comprehensive plan to reform both Dharma robes and regular ones.

Regarding Buddhist monastic robes, Dongchu proposed that the haiqing with a seven-strip robe as the superior attire for monks. He aimed to replace the traditional Dharma robes with this “superior formal attire”. However, the challenge was that the Haiqing was not classified as a robe, and while the seven-strip robes were indeed Dharma robes, substituting the tricīvara with it effectively weakens the symbolic and religious significance of the monastic robes. Additionally, Dongchu stipulated that only scholar monks and abbots could wear the superior formal attire, while other monks could wear it only when presiding over a ceremony or delivering a sermon. As the Dharma robe became exclusive to certain positions, its symbolic function was ultimately diminished, bringing it one step closer to potential replacement eventually.

In terms of regular robes, Dongchu designed three sets of robes (

Table 1). First, the virtue-monk robe (德僧服,

desengfu) is intended for abbots, retired monks, leaders, virtuous monks, and missionary monks. The design features a pair of lapels, with the back length measuring approximately eight inches. The pants are designed to be tied up, and the socks are made of imported gauze. The shoes can either be round-toed cloth shoes or leather shoes. The lapel collar should not exceed three inches in width, the sleeve length should not extend beyond the hands, and the overall robe length should not surpass the ankles, with cuff width being appropriately measured. The color palette consists of gray, black, and navy blue, making the robe suitable for both indoor and outdoor activities, welcoming guests, traveling, and serving as formal attire when paired with a new

kāṣāya. Secondly, the duty-monk robe is designated for monks such as scholar monks, missionary monks, abbots, and administrative personnel. This robe is characterized by its flexibility, cost-effectiveness, and ease of movement. The trousers are designed to avoid constricting the wearer. The length of the top should extend beyond the knee, with cuffs measuring five inches. The length of the pants should align with the ankle bone, and the width of the trousers should be approximately five inches. The color should match that of the virtue-monk robe. Scholar monks who attend puja or participate in a special ceremony (法會,

fahui) may wear this robe. If worn out, it may still serve as a formal attire when paired with a new

kāṣāya worn over it. The third type is the scholar-monk robe. It is intended for students in Buddhist academies, trainees, and young duty monks. The length of the upper robe should reach the thighs, the sleeves should not extend beyond the palms, and the cuffs should match the ordinary students’ uniforms. Colors remain coordinated in shades of gray, black, and navy blue. There are no restrictions on the occasions for wearing this robe, serving as formal attire when a new

kāṣāya is worn over it. The early design of the virtue-monk robes, duty-monk robes, and scholar-monk robes was inspired by suits and coats. The differences between these robes and common clothing are quite minimal, and wearing any of them with a new

kāṣāya on top can replace Dharma robes, while diminishing the significance.

Overall, compared to Taixu’s cautious approach of upholding the traditional Dharma robes while reforming regular robes, Dongchu’s proposals were bolder and more radical. However, compared with Lengjing, Dongchu displayed a more reserved and moderate stance, which led Taixu to refrain from opposing his views. In contrast, Lengjing completely disregarded the significance of Dharma robes and advocated for full conformity to secular fashion, which directly opposed Taixu’s principles.

- (3)

Disregard for Dharma Robes and Indiscrimination of Secularization

Under the banner of supporting Dongchu, Lengjing followed Dongchu and published “On the Reform of Monastic Robe and Formal Attire” 論僧裝改革及其禮服 in the sixth issue of Haichao Yin in the same year. In this work, he presented even more radical views on the reform of the monastic robe based on Dongchu’s thoughts.

Lengjing’s opinions can be roughly summarized as follows: First, he called for the Chinese Buddhist Association and Buddhist academies nationwide to implement initial reforms to set an example for monks nationwide. Second, based on Dongchu’s designs, he advocated that scholar monks adopt the same hat styles worn by students in secular society, with only the word Buddha printed in a circular seal script on the tongue of the hats to distinguish them. He also proposed that monks wear white or black sneakers as footwear. Lengjing’s perspective was to replace the traditional monastic robe with contemporary lay clothing. This viewpoint represented the views of a group of the Community at that time, who believed that “the current Chinese monastic robe is essentially nothing more than ancient secular clothing; therefore, it might as well be transformed into contemporary secular clothing” (

Shengyan 2010b, The Unification and Improvement of Monastic Robes, p. 149).

As for the Dharma robe, Lengjing completely disregarded it, not mentioning it at all. He suggested that regardless of whether they were abbots, retired monks, or scholar monks, all should wear Haiqing during worship or ceremonies. Differences in rank would be distinguished by colors; for instance, abbots and retired monks would wear yellow, purified monks and senior monks would wear gray, scholar monks from various Buddhist academies would be attired in black, while duty monks would wear navy blue. (

Lengjing 2006, On the Reform of Monastic Robe and Formal Attire, pp. 456–57). This approach effectively sought to abolish the traditional Dharma robe system altogether. To some extent, Lengjing’s perspective was influenced by Western Christianity and the modernization of Japanese Buddhist monastic robes following the Meiji Restoration (明治維新 a political revolution in Japan that began in 1868). However, as Shengyan noted, “Japanese monks hang a cloth bag on their chests as a symbol of their ordinary status, which is indeed overly symbolic” (

Shengyan 2010a, On Monastic Robes 論僧衣, p. 127). Shengyan further articulated, “If removing the traditional Chinese robes and donning a suit is considered reform, then I would prefer Buddhism to remain conservative for good rather than talking about ‘reform’. In reality, this is not a genuine reform, but a regression into vulgarity. Genuine reform involves improvement, discarding the old and bringing forth the new. When individuals observe the traditional robes, they undoubtedly recognize it as that of a

bhikṣu; similarly, when they encounter the new robes, it still conveys the essence of a

bhikṣu, appearing more solemn, dignified, and inspiring of reverence.” (

Shengyan 2010b, The Unification and Improvement of Monastic Robes, pp. 149–50). The problem was that for younger monks who embraced modern ideas, “Actual refuse rags, however, came to be considered as symbolic of extreme austerity; as such, they were certainly not favored by the general monastic community.” (

Heirman 2014, p. 485)

Since then, the so-called “New Community” 新僧伽 has sought to change the style of monastic robes, leading to endless debates. At that time, many radical monks were seen frequenting various social venues in suits, resulting in a situation that was nearly out of control, leaving Taixu in a dilemma.

4. Debates from All Sides on the Buddhist Monastic Reform During the Republican Era

The traditionalist Community critically opposed the New Community’s approach to robe reform. Within the reformist camp, the debates centered on different opinions on the proposed styles, reflecting a disagreement over esthetic differences.

- (1)

Traditionalist Community’s Directional Criticism of Buddhist Monastic Robe Reform

Taixu’s cautious proposals for the monastic robe reform did not provoke controversy within the Buddhist Community; however, the radical proposals put forth by Dongchu and Lengjing ignited widespread uproar. “Chinese monks firmly wed to their Buddhist identity did not give up their robes without reluctance, and we have many accounts of monks who risked persecution rather than surrender their robes.” (

Kieschnick 1999, pp. 9–32). The traditionalist Community exhibited a resolutely critical stance toward the alteration of monastic robes. For instance, Genghui 根慧, the abbot of Guanzong Temple 觀宗寺 in Ningbo寧波, strongly criticized the reforms:

“The image of a monk adorned in a Dharma robe, holding a mantle, can naturally inspire individuals to pursue the path of Buddhism, encouraging them to set aside malevolent thoughts and cultivate a genuine respect for the teachings... This raises the question: why must we adopt the robes of contemporary students as fashionable attire? 圓頂方袍, 搭衣持缽, 令人目擊道存, 起想起見, 觀摩興起, 閑邪存誠… 何必厭古喜新, 效法現代學生所著之短後服裝, 以誇耀時髦耶!” (

Genghui 2006, p. 265)

The perspectives of Genghui reflect the fundamental perspective of traditionalist monks. As Shengyan articulated, “From the perspective of appearance, modern robe lacks the transcendence and freedom of the ancient one. In terms of comfort, it also falls short in terms of spaciousness and elegance. While a traditional robe has its drawbacks—such as hindering vigorous movements and requiring more fabric— the primary concern for a

bhikṣu is maintaining solemnity. If a

bhikṣu conducts a religious ceremony while all attendees are dressed in suits, the sacred atmosphere will be inevitably diminished.” (

Shengyan 2010b, The Unification and Improvement of Monastic Robes, p. 149). In this regard, Genghui also pointed out that reforming the monastic robe was akin to “putting the cart before the horse”. He argued that if the new robes were to resemble secular robes, this could cause serious consequences. Monks might adopt secular lifestyles—wearing suits, marrying, raising children, and engaging in speculative business—ultimately becoming indistinguishable from laypeople (

Genghui 2006, p. 266). If this continues, “the extinction of Buddhism may be anticipated soon.” (

Genghui 2006, p. 266).

As Diane Elizabeth Riggs discussed, “In an era when not even monks can keep the precepts, the Buddhist robe becomes the lone signifier of the Buddhist monk.” (

Riggs 2010, p. 9)

In his novel

Monastic Robe 僧裝, Zhenhuan 震寰 elaborates the traditionalist criticism of monastic robe reform. The protagonist, Fazhi 法智, a young monk who supports the new robes, believes that the monastic robe must change for Buddhism to rejuvenate. However, his master criticizes that, “You scholar monks don’t study all day, but make trouble. Nowadays, Buddhist academies are terrible! It only cultivates trouble makers.” (

Zhenhuan 2008, p. 423). It can be observed that Fazhi’s master criticized the reform itself; in other words, he opposed the reformers’ tendency to favor the new and reject the old. As for the “young

bhikṣu, most of them lack fundamental ideals and clear plans, and the reform is often a mere echo of others. Of course, young people tend to be fashionable, so it would be nice to abolish the traditional robes with long collars and wide hems and replace them with tight, lightweight suits!” (

Shengyan 2010b, The Unification and Improvement of Monastic Robes, p. 149)

The traditionalist monks’ criticism of the reform reflects a fundamental difference in their understanding of protecting and propagating the Dharma compared to that of the reformers. Traditionalists believe that respecting and adhering to the Buddhist tradition is key to safeguarding the Dharma, asserting that only through maintaining established forms could the public recognize and respect the monks, dispelling evil thoughts and maintaining sincerity in both mind and behavior. Thus, “the great power of the Dharma to benefit living beings” can be brought into play. (

Taixu 2004b, The Rites and Precepts of the Seven Kinds of People are not to be Exceeded 七眾律儀不得逾越, p. 121). For traditionalist monks, the robes symbolize the Buddha and his teachings, marking a stark contrast with the New

saṃgha’s approach to propagating the Dharma.

- (2)

Differing Views within the Reformers on the Different Proposals towards Monastic Robes

At that time, the controversy surrounding the reform involved not only traditionalists and reformers but also differing factions within the reformers themselves. Unlike the traditionalists, who debated whether or not to change the robes at all, the reformers argued over what kind of changes should be made, reflecting differences in esthetic preferences, cultural orientations, and interpretations of Buddhist disciplines.

In 1946, Cihang, a student of Taixu, expressed strong opposition to an article published by Dongchu and others in Haichao Yin regarding the reform. Without fully understanding the context, he assumed that the article must have been endorsed by Taixu himself. In response, he published a special article titled “On Protecting the Dharma” in the ninth issue of Xingzhou Chinese Buddhism 星洲中國佛學, which he edited. In this issue, Cihang prominently raised the banner of “protecting the Dharma” and explicitly aimed to challenge what he called the “fake” remarks made by Dongchu and others.

Cihang’s opposition towards Dongchu and others was based on three main arguments. First, he maintained that any modification of the monastic robe should not violate the established Buddhist system. Second, he argued that the designs proposed by Dongchu and others were indistinguishable from secular clothing, which could potentially lead young monks to engage with secular society, breaking precepts and even committing crimes, thus tarnishing the reputation of Buddhism. Third, if reforms were indeed necessary, Cihang insisted they should follow the styles worn in Southern Buddhist countries such as Ceylon (historical name of Sri Lanka), Burma (historical name of Myanmar), and Nepal. In addition to criticizing the proposed changes, Cihang offered his proposals, which can be summarized as follows: adherence to the Buddhist system, respect for customs, consideration of climate, alignment with national traditions, and no objection from society. He emphasized the need for simplicity, convenience, and acceptance among elder monks. Cihang proposed that “the yellow robe distinct from secular clothing, and the

kāṣāya represents the image of monks” (

Cihang 慈航 2008, pp. 135–37). Cihang argued that all monks in China should wear yellow robes from head to toe, following the standards of Southern Buddhist countries, and adjust their attire seasonally according to the climate. He emphasized that monks should wear the robes throughout their daily activities. Furthermore, Cihang created a dozen sets of monastic robes, wore them himself, and published photographs on “Xingzhou China Buddhism” as visual examples.

Cihang’s recklessness and his theory of the reform were also refuted by Taixu, who pointed out that Cihang “failed to clearly distinguish between ‘disguise’, ‘robe variation’, and ‘Buddhist disciplines’” 沒有把偽裝, 變裝, 佛制範圍認清 (

Taixu 2004g, The Second Epistle with Cihang 與慈航書二, p. 116). He criticized:

The Buddhist system has only three robes. The five-strip robe is like a skirt; everything else is simply adaptation to time and place; there is no such thing as “disguise”, everything we have discussed are examples of “variation”. 佛制只有三衣, 五衣即裙, 此外都是隨時隨地的變裝, 只變裝也無所謂偽 (

Taixu 2004g, The Second Epistle with Cihang 與慈航書二, p. 116)

Taixu’s criticism provoked a stronger reaction from Cihang, who responded by asserting that the monastic robe should either remain unchanged or follow the styles of Southern Buddhist countries. Cihang demanded that Taixu publicly clarify his stance; otherwise, he would announce his departure from the “Lineage Registration for New Monks” 新僧籍 and focus on opposing the faction led by Taixu. Taixu condemned Cihang’s actions as “shameful”, emphasizing that the reform of the monastic robe was not about replacing it with “secular clothing”. He argued that, since the traditional Chinese monastic robes were already reminiscent of ancient secular ones, there was no problem in adapting them to align with contemporary styles. Nevertheless, Taixu’s explanation failed to persuade Cihang, who subsequently issued an “ultimatum” challenging Taixu on the matter of the “New Community “, mockingly referring to Taixu as the “leader of the reformers” who refused to acknowledge the existence of this group. The dissemination of Cihang’s opinions drew criticism and backlash from various quarters.

In 1947, Ziyan 子彥 published “The Waves of Reform in Monastic Robes” (僧裝改革的波瀾 Sengzhuang gaige de bolan) in Zhengxin 正信 magazine, where he asserted that Buddhism in Burma, Ceylon, and Siam had struggled to thrive due to their cultural limitations. He argued that it was just the profound Chinese culture that allowed Buddhism to flourish, suggesting that monks do not need to conform to the standards of southern Buddhist countries by adopting the yellow robes. He also critiqued Cihang’s representation of the monastic robe, claiming it did not fully align with Buddhist disciplines and criticizing his extreme rhetoric and views. In the same year, Yinshun published articles in Juequn Weekly 覺群周報, offering separate critiques of both Cihang and Dongch. He first condemned Cihang’s reckless approach in confronting Taixu, highlighting his lack of understanding and empathy towards Chinese Buddhism. Yinshun pointed out that Cihang’s insistence on the yellow robes was not only inconsistent with Buddhist principles but also led to an over-casual attitude toward the kāṣāya. Additionally, Yinshun “thoroughly criticized” the reform proposals put forward by Dongchu.

Yinshun was a clear advocate for reforming monastic robes; however, the motivation for this change required re-examination. He disagreed with Dongchu’s viewpoints, asserting that his reasoning was flawed and misdirected. Additionally, Yinshun criticized Dongchu’s designs, stating that they neither represented the Community externally nor were sufficiently innovative internally. Such a half-hearted reform of the monks’ uniform was intolerable and deserved a thorough critique (

Yinshun 2009b, Commentary on the Reform of Monastic Robe 僧裝改革評議, pp. 28–29). Regarding the adaptation of monks’ clothing to contemporary times and environments, Yinshun put forward his views.

In March 1947, Taixu passed away in Shanghai. Subsequently, in May 1947, the National Congress of the Buddhist Association of China was held in Nanjing. On the opening day, a group of young monks, eager to reform monastic robes, displayed a banner stating, “Monastic robe reform should not be delayed.” The delegates spent considerable time discussing this issue; however, the atmosphere remained contentious. Despite extensive debates over the proposal to reform monastic robes, the Congress ultimately decided that the matter would be studied further by the Standing Council after the meeting. Unfortunately, the Standing Council did not offer any resolution, and this issue was eventually unresolved.

5. Conclusions: Disenchantment and Preservation of Monastic Discipline in the Modernization of Buddhism

During the Republican era, Chinese Buddhism underwent a transformative shift from traditional to modern society. The reform of monastic robes, as part of broader monastic system reforms, adhered to the principle of “adapting vinaya to local conditions” (隨方毗尼, Suifang pini). In this process, Buddhism sought a balance between “disenchantment” and “preservation of monastic discipline” to achieve an evolution suitable for the times. Taixu advocated for monastic robe reform during this period with the aim of fostering greater societal acceptance of monastics in the new social context, thus facilitating the progressive development of Buddhism.

- (1)

Taixu’s Reformist Vision and His Passive Endurance of Criticism as a Radical

The reform principle proposed by Taixu during the Republican era— “Ritual robes adhere to Buddhist precepts; daily wear adapts to contemporary needs”—demonstrates a dialectical wisdom in responding to historical change while upholding the fundamental tenets of

vinaya discipline. Raoul Birnbaum stated that “One Buddhist leader who resisted such attacks and tried to establish a new, revitalized Buddhism was Taixu (1889–1947). He attempted to change Chinese Buddhism radically and establish a humanistic Buddhism. Taixu contended that Buddhism should not be a religion that encourages one to transcend this world and attain enlightenment. Rather, it should be a religion that endeavors to realize the ideal within this secular society.” (

Kieschnick 1999).

A fundamental characteristic of Taixu’s Humanistic Buddhism is its dual commitment to accordance with truth (契理) and adaptation to circumstances (契機), where the observance of Buddhist systems is inherently embodied in the principle of accordance with truth. As Shengyan emphasized, “

Bhikṣu, regardless of the circumstances, must not deviate from the principles of the Buddhist system.” (

Shengyan 2010b, The Unification and Improvement of Monastic Robes, p. 151.) However, against the backdrop of cultural confrontation between East and West, and between antiquity and modernity, among the students who studied under Taixu, “while some indeed progressed along the authentic path of modern Buddhism, others regressed into ossified traditionalism, and still others pursued only a crude vulgarization of Buddhism, resulting in numerous manifestations of ideological immaturity.” (

Taixu 1928, “An Instruction to the Revolutionary Monks of Chinese Buddhism” 對於中國佛教革命僧的訓詞). Some even “judged everything solely by its novelty or foreign origin—worshiping and treasuring anything new or imported without scrutinizing its actual merits or flaws.” (

Yuan 1923).

Regarding monastic robe reform, Dongchu diminished the significance of ritual robes, while Lengjing abolished them entirely by adopting Western suits. These radical propositions reflected the profound existential anxiety among Buddhist reformists during the unique historical period of the Republican era, as they confronted the pressures of modernization. Indeed, Taixu had long articulated his dissent from radical reforms, issuing a clear admonition that “monks who are unable or unwilling to uphold monastic discipline should voluntarily return to secular society—while monastic robe may vary across times and regions, it must remain distinct from secular clothing; those unwilling to wear monastic robes ought to relinquish their monastic status.” (

Taixu 1928, “An Instruction to the Revolutionary Monks of Chinese Buddhism”). The crux lies in the following: “Although Taixu opposed radical approaches, once a binary opposition solidified, the transgressions of the radical faction were unjustly attributed to him as well.” (

Li 2022). As a result, even Venerable Cihang, one of Taixu’s disciples, publicly opposed him. In reality, the responsibility and consequences stemmed from Dongchu and Lengjing, yet Taixu passively bore the burden of their actions and was subjected to criticism.

- (2)

Reasons for the Failure of Buddhist Reform Analyzed by the Reformists

During the Republican era, the success or failure of Buddhist reforms, including monastic robe modernization, resulted from a complex interplay of multiple forces. Between the traditionalist and reformist monastic factions, the traditionalists held numerical superiority. Moreover, as the majority of abbots, they controlled monastic economies and wielded decisive authority in institutional governance and discourse power. In contrast, the reformist “New Community” faction drew its primary strength not from established temples but from newly formed Buddhist associations. However, these national and regional Buddhist organizations were loosely structured, although they received nominal recognition and rhetorical support from the Republican government, they failed to obtain substantive backing—neither financial allocations nor tangible administrative authority were granted. Thus, “within the state-religion dynamics, modern Chinese Buddhism occupied a structurally passive position—a condition that fundamentally constrained its path toward world-engaged transformation” (

Hong. 2024). As Holmes Welch observed, even national Buddhist organizations during the Republican era lacked substantive influence at the local level, functioning like “a head without a body” (

Welch 1967). The reformist faction failed to establish a reliable economic foundation, which meant their capacity to exercise effective decision-making and influence remained severely limited.

Furthermore, some traditionalist abbots would identify and cultivate future leaders from within the “New Community” faction. As for the members themselves, their perspectives often evolved as their roles changed. “Once a cohort of ‘old monks’ stepped down from the stage, a generation of ‘new monks’ likely transformed into ‘old monks’, making it impossible for the monastic community to reach a consensus on the reform.” (

Shao 2017). Therefore, during the National Congress of the Chinese Buddhist Association convened in Nanjing in May 1947, although young monks proposed that “monastic robe reform admits no delay”, no prominent figures spoke out in support—a silence that laid bare the self-evident power imbalance at play.

In addition, lay Buddhists generally opposed monastic robe reforms. For instance, Jingwu Ouyang 歐陽竟無, observing that contemporary monks often failed to uphold monastic discipline rigorously, issued scathing critiques and even advocated for the revival of the dhutaguṇa (a system of ascetic practices in Buddhism that involves extreme simplicity in lifestyle for spiritual cultivation)of the Buddha’s era. He insisted that the monastic robe should also revert to its original Buddhist form, thus resolutely condemning any tendency to secularize the monastic robe.

For ordinary lay devotees, both their faith and emotional attachment inclined them to desire that monks strictly adhere to monastic discipline, in order to preserve Buddhism’s sacred character. Traditional monastic robes, as embodiments of the Buddha’s prescribed system, served as potent symbols of this sacredness. These laypeople were primarily concerned with securing both spiritual and material benefits through their faith and practices. Consequently, Buddhist reforms held little appeal for them, especially since “elite lay Buddhists with economic influence possessed their devotional preferences... and their deeply ingrained religious habits rendered them resistant to accepting radical transformations within the community.” (

Shao 2017). They would find it strenuously difficult to accept the secularization of monastic robes.

- (3)

Adaptive Development between Disenchantment and Preservation of Monastic Discipline during the Republican Era

Chinese Buddhism ultimately refrained from emulating Christianity or Japanese Buddhism in secularizing clerical attire, steadfastly preserving its tradition of ritual robes instead. The Republican-era debates over monastic robe reform, serving as a microcosm of broader Buddhist reforms, revealed the multidimensional dilemmas confronting traditional Buddhism amid modernization: it is necessary to both safeguard the institutional foundations that upheld its sacred character and simultaneously demystify outdated traditions that no longer aligned with contemporary development. Navigating this tension between disenchantment and system preservation became essential for Buddhism’s adaptive evolution in response to the needs of the times. It was this dialectical interplay between tradition and reform that fueled the internal momentum driving Buddhism forward.

Indeed, during the Republican era, the rapid spread of Christianity throughout China drew close attention from Buddhist circles. Visionaries such as Wenhui Yang 楊文會, Xuyun 虛雲, Yuanying 圓瑛, and Taixu —while reflecting on Buddhism’s decline and seeking paths for its revitalization—not only closely observed but also critically engaged with the development and worldly activities of Christianity, drawing inspiration from its model to propel Buddhism’s transformation toward greater social involvement (

Hong. 2024). Taixu’s proposal for monastic robe reform, along with Dongchu and Lengjing’s trend toward sartorial secularization, was partially influenced by Christianity. As Taixu acknowledged, “Over the past two to three decades, some of my efforts to reform Buddhism arose from the inspiration brought by Christianity’s introduction to China... I felt it imperative to learn from Christianity to advance Buddhism’s modernization.” (

Taixu 1938, China Needs Christianity, and the West Needs Buddhism 中國需耶教與歐美需佛教).

When Christianity and other Western religions, as emblems of modernity, penetrated Chinese society with formidable influence, and when Japanese Buddhism began adopting Western-style robes, Chinese monks confronted an acute identity crisis. Under these circumstances, although their reformist proposals deviated from traditional systems, they were historically justified, shaped by the specific conditions of the time. As Tankha insightfully indicated, “Dress reflected the changes in religious institutional structures and ideas that were carried out in response to the impact of Christianity and its projection as a modern religion of the advanced Western world” (

Tankha 2018, p. 318). The enduring vitality of Buddhism hinges upon a dynamic equilibrium between upholding the animating spirit of the Buddhist system and adapting to the times—neither rigidly clinging to tradition nor fully succumbing to the secularization that would dissipate its sacred essence. Through sustained discipline negotiations and intellectual collisions, Republican-era Buddhism ultimately forged a harmonious path that simultaneously embraced disenchantment and discipline preservation, rooted firmly in tradition while responding to contemporary imperatives. Raoul Birnbaum also noted that “many current practices take their shape from the innovations that transformed Chinese Buddhist life in the late Qing and Republican periods. While profound political, economic, and social changes have occurred in the past few decades, some of the most pressing issues are extensions of questions raised at that time.” (

Birnbaum 2003, p. 428).

It must be acknowledged that the debates over monastic robe reform reflect the inherent tension between the preservation of traditional discipline and the push for modern world-engagement in Buddhism’s modernization process. This tension crystallized in the interplay of disenchantment and observance of the monastic robe. Through dynamic adaptation amid this dual framework, Buddhism navigated its path forward.

Taixu’s reform agenda extended beyond monastic robes to encompass systematic efforts toward the modernization of Buddhism. These efforts included innovations in Buddhist music, such as The Three Jewels rendered in Western notation; international diplomatic engagement through conference delegations sent to Germany, France, and the United States; and curricular innovations in Buddhist higher education, including the introduction of English and Japanese studies. Although his comprehensive reform program ultimately proved unsustainable, its integrated vision, particularly the symbolic significance of the robe reform within broader institutional changes, provides enduring insights for contemporary Buddhist modernization.