The Social Network of the Holy Land

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Social Network Analysis and the Study of Literature

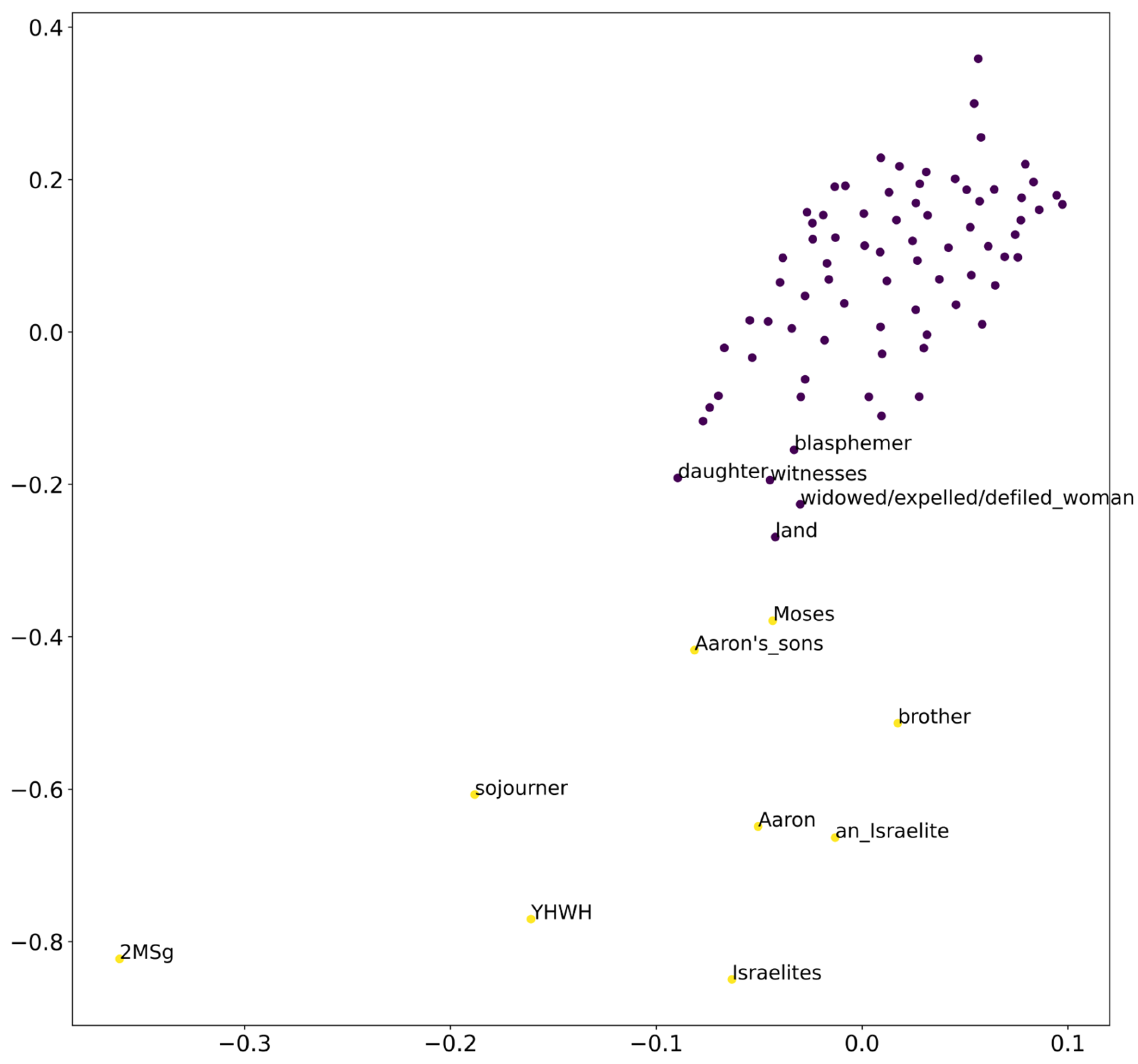

2.2. Social Space

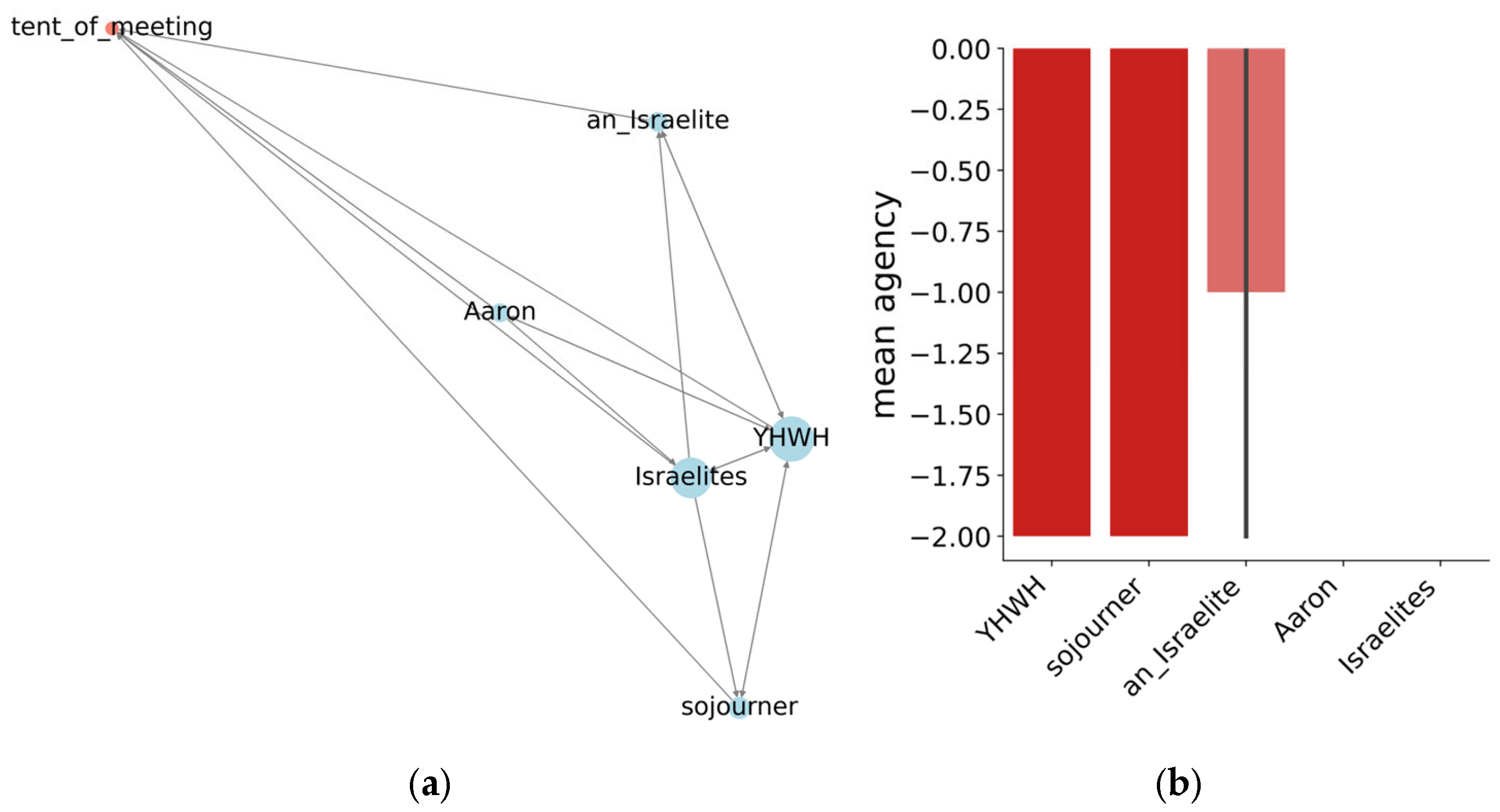

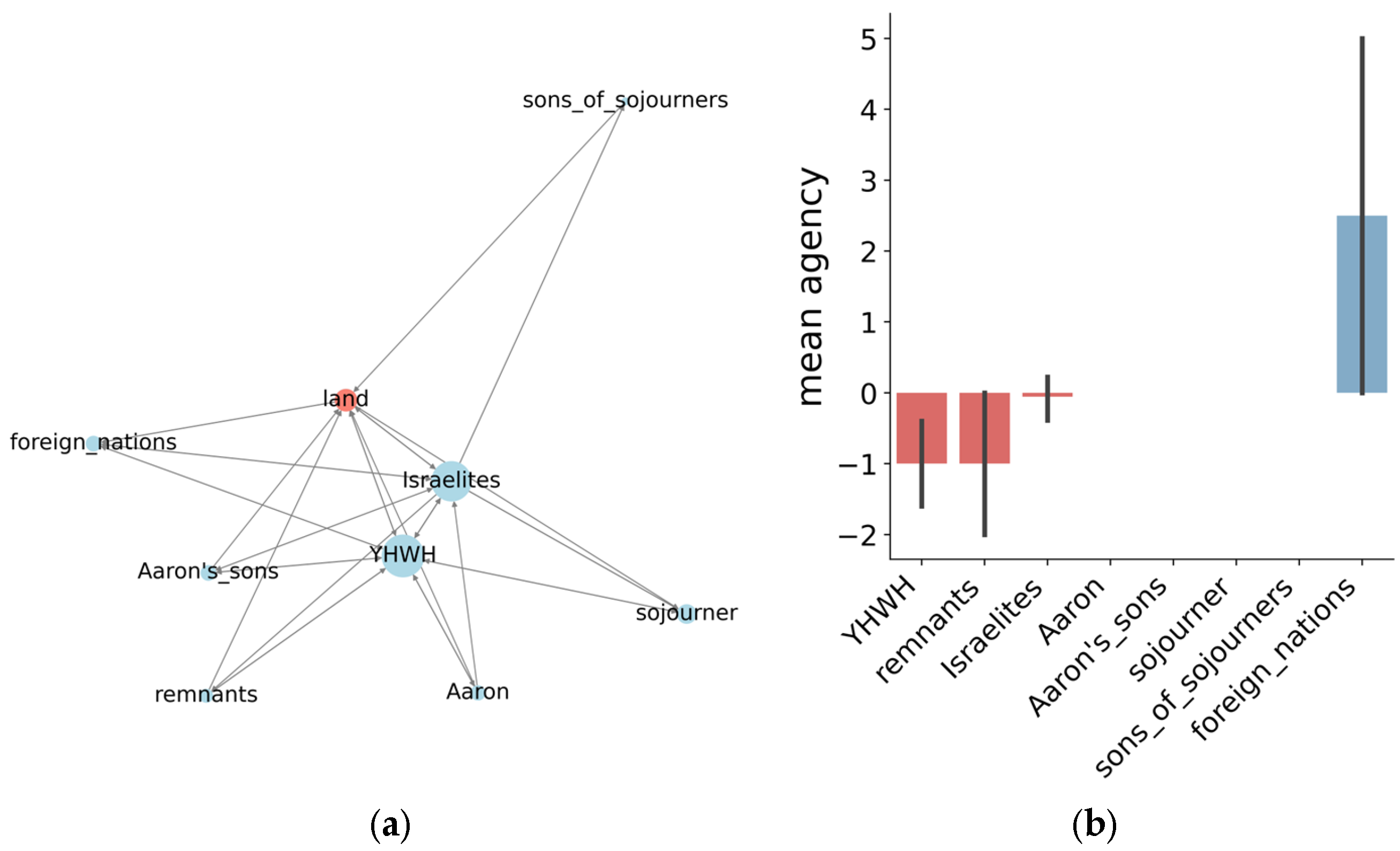

2.3. Agency of Space

3. Results

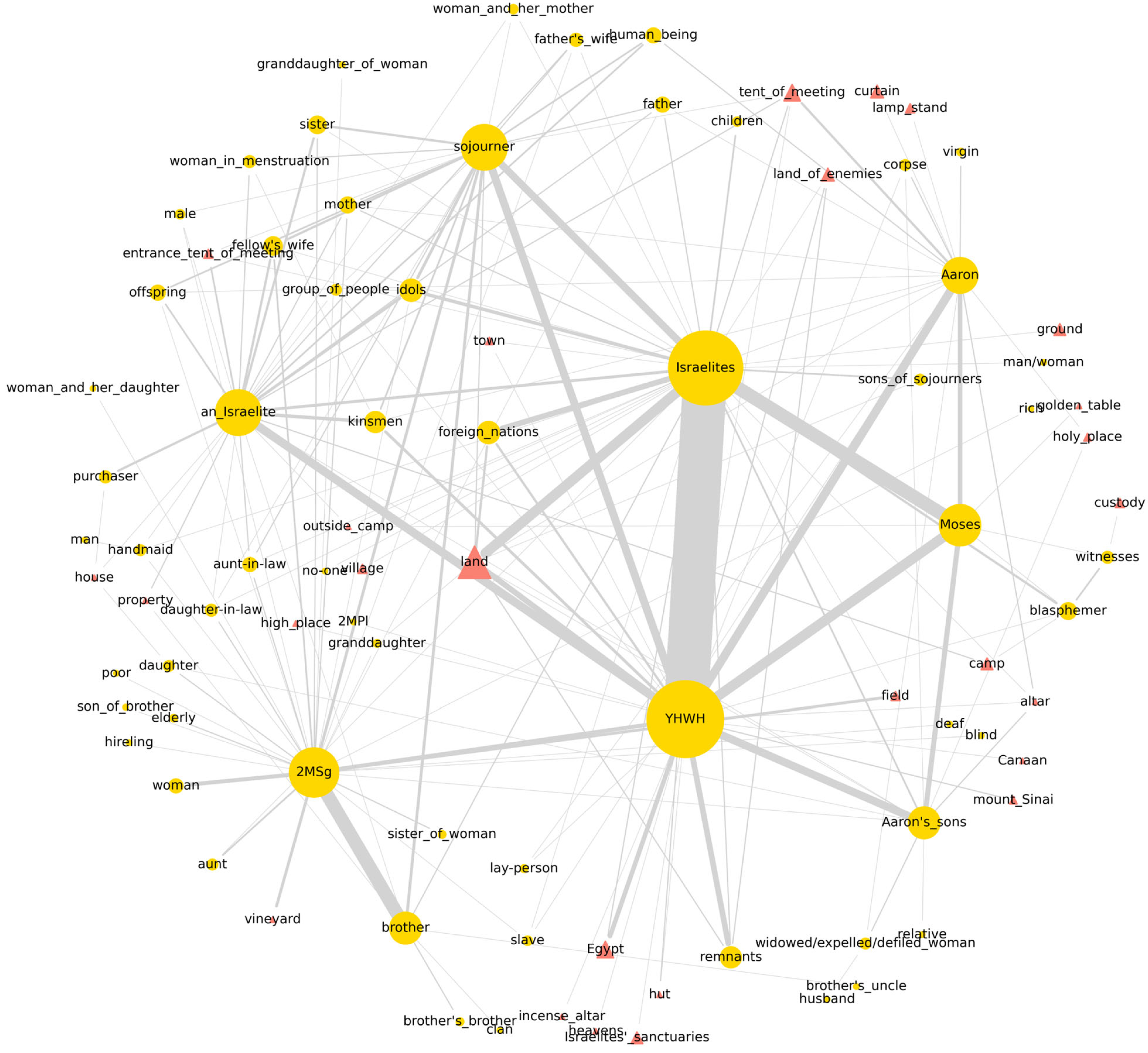

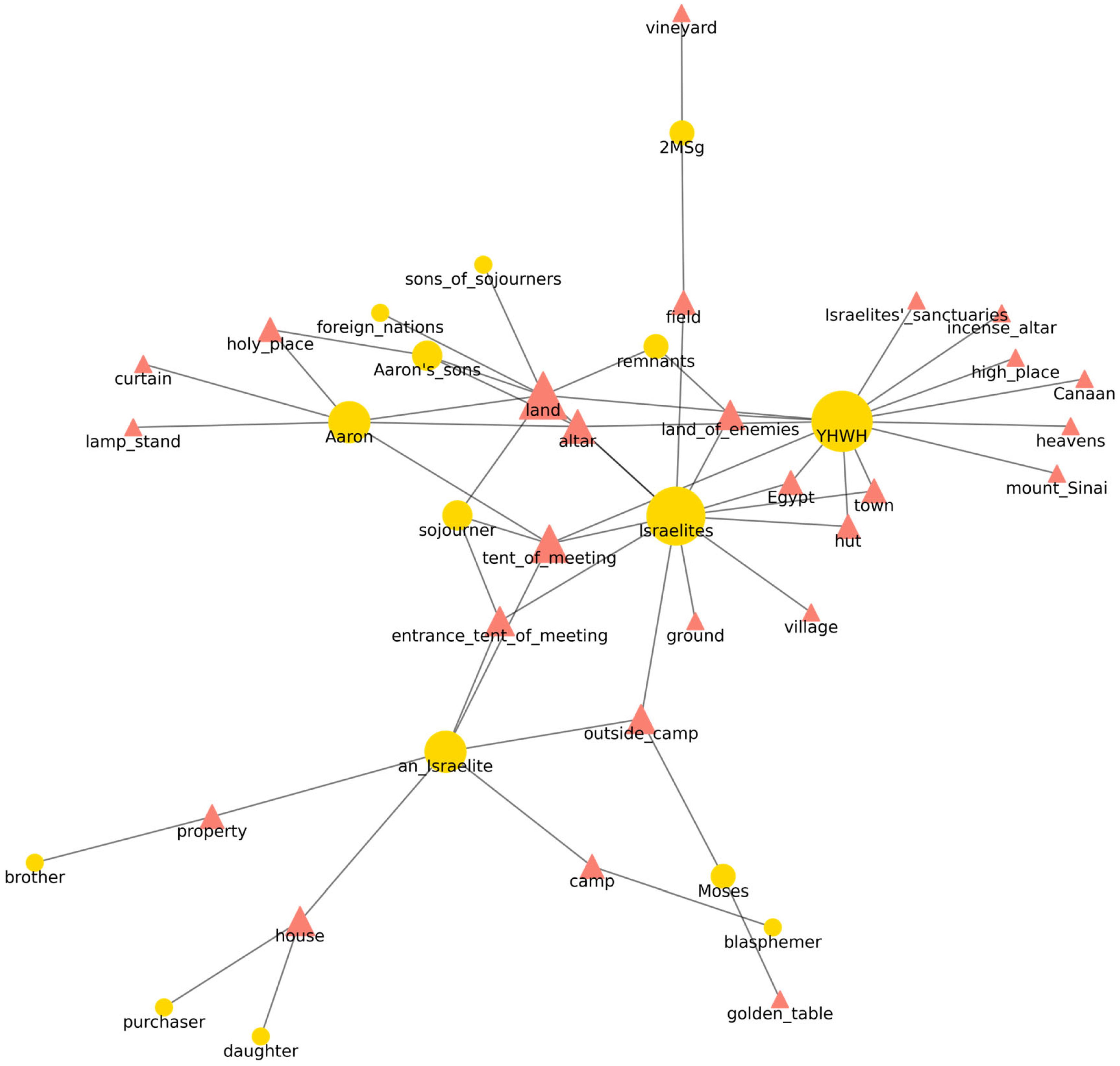

3.1. Land Access

3.2. Personified Land

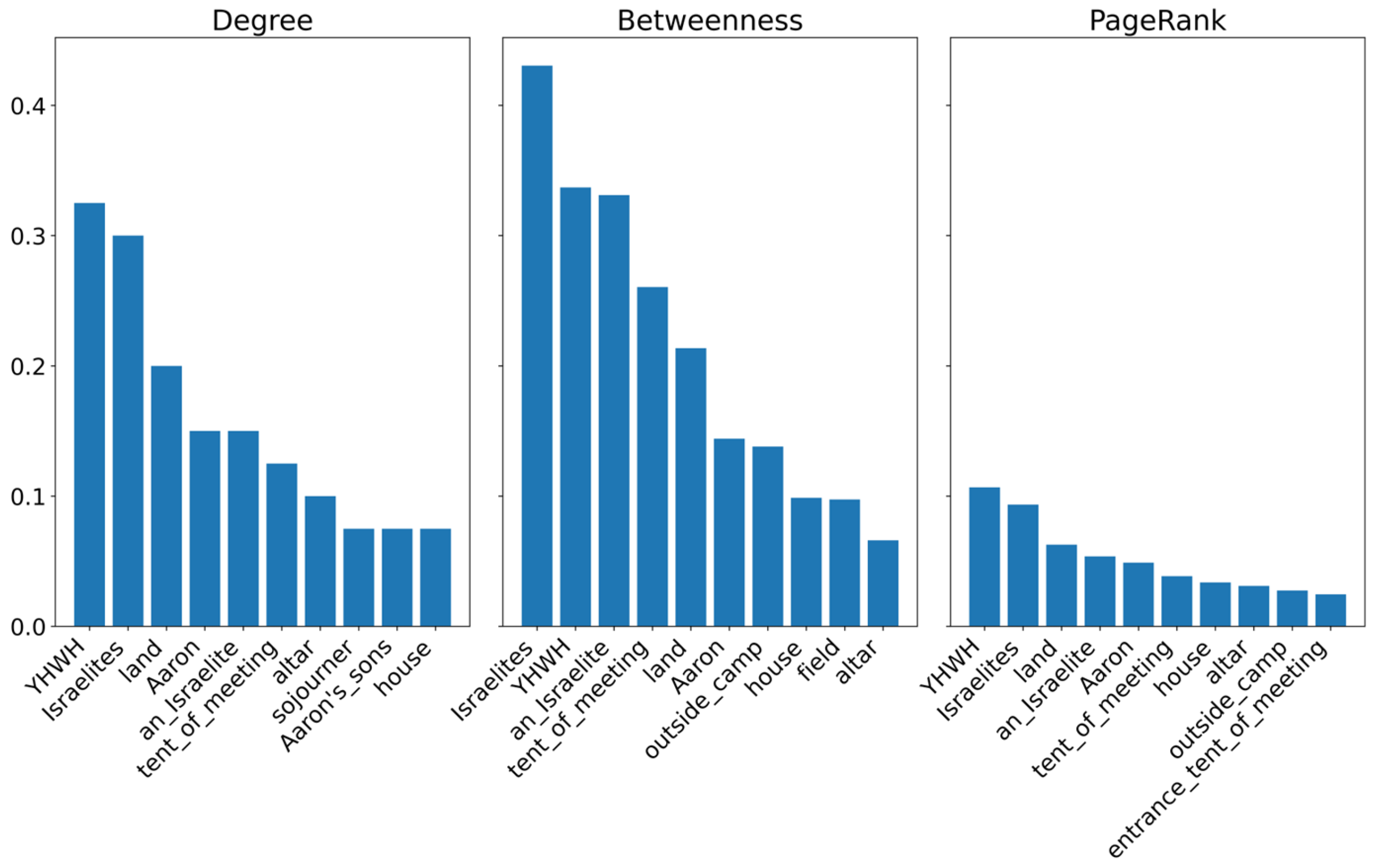

3.3. Structural Role

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role of the Land

4.2. The Potential of Social Network Analysis for Literary Analysis

5. Materials and Methods

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | confidence interval |

| MDS | multidimensional scaling |

| SNA | social network analysis |

| 1 | For general introductions to SNA, see Marin and Wellman (2014); Scott (2017); Scott and Carrington (2014); Tang (2017). |

| 2 | The distinction between Israelites (plural addressees), 2MSg (singular addressees), and an Israelite (singular but not addressed, typically used in case laws) was inherited from the original network in Højgaard (2024, esp. 110–14), where it served to differentiate semantic and rhetorical notions pertaining to the Israelites. |

| 3 | In two-mode networks, relationships exist between two types of nodes, and edges are only established between nodes belonging to different types. |

| 4 | Degree refers to the number of edges tied to a node. In the graph, the degree is normalized by the maximum number of ties possible. Betweenness is a measure of how often a node occurs on the shortest path between two other nodes. High betweenness scores are usually associated with control because transactions will often pass through nodes with high betweenness (Brass 1984). PageRank ranks nodes based on the number of ties from other nodes and the centrality of those nodes (Page et al. 1998). |

References

- Agarwal, Apoorv, Augusto Corvalan, Jacob Jensen, and Owen Rambow. 2012. Social Network Analysis of Alice in Wonderland. Paper presented at the NAACL-HLT 2012 Workshop on Computational Linguistics for Literature, Montréal, QC, Canada, June 3–8; Edited by David Elson, Anna Kazantseva, Rada Mihalcea and Stan Szpakowicz. Stroudsburg: Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Barbiero, Gianni. 2002. Studien Zu Alttestamentlichen Texten. Stuttgart: Verlag Katholisches Bibelwerk. [Google Scholar]

- Brass, Daniel J. 1984. Being in the Right Place: A Structural Analysis of Individual Influence in an Organization. Administrative Science Quarterly 29: 518–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Chebineh. 2017. Participants, Characters and Roles. A Text-Syntactic, Literary and Socioscientific Reading of Genesis 27–28. Ph.D. dissertation, Vrije University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, William. 2022. Morphosyntax: Constructions of the World’s Languages. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donati, Pierpaolo. 2017. Relational versus Relationist Sociology: A New Paradigm in the Social Sciences. Stan Rzeczy 12: 15–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emirbayer, Mustafa. 1997. Manifesto for a Relational Sociology. American Journal of Sociology 103: 281–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenewegen, Peter, Julie E. Ferguson, Christine Moser, John W. Mohr, and Stephen P. Borgatti, eds. 2017. Structure, Content and Meaning of Organizational Networks: Extending Network Thinking. Bingley: Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, Aditya, and Jure Leskovec. 2016. Node2vec: Scalable Feature Learning for Networks. Paper presented at the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, August 13–17; New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 855–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg, Aric A., Daniel A. Schult, and Pieter J. Swart. 2008. Exploring Network Structure, Dynamics, and Function Using NetworkX. Paper presented at the 7th Python in Science Conference, Pasadena, CA, USA, August 19–24; Edited by Gael Varoquaux, Travis Vaught and Jarrod Millman. Pasadene: SciPy. [Google Scholar]

- Hieke, Thomas. 2014. Levitikus 16–27. Freiburg: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Højgaard, Christian Canu. 2023. Rational Actors and the Ancient Israelite Jubilee Legislation. In Modern Economics and the Ancient World: Were the Ancients Rational Actors? Selected Papers from the Online Conference, 29–31 July 2021, Muziris. Edited by Sven Günther. Münster: Zaphon, pp. 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Højgaard, Christian Canu. 2024. Roles and Relations in Biblical Law: A Study of Participant Tracking, Semantic Roles, and Social Networks in Leviticus 17–26. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, John D. 2007. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Computing in Science & Engineering 9: 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, Jan. 1996. People and Land in the Holiness Code: An Exegetical Study of the Ideational Framework of the Law in Leviticus 17–26. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, Jan. 1997. «Tu» et «vous» Dans Le Code de Sainteté (Lév. 17–26). Revue Des Sciences Religieuses 71: 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, Jan. 2010. La Persuasion Coopérative Dans Le Discours Sur La Loi: Pour Une Analyse de La Rhétorique Du Code de Sainteté. In Congress Volume Ljubljana 2007, Supplements to Vetus Testamentum. Edited by André Lemaire. Leiden: Brill, pp. 381–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Renming, and Arjun Krishnan. 2021. PecanPy: A Fast, Efficient and Parallelized Python Implementation of Node2vec. Bioinformatics 37: 3377–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, Alexandra, and Barry Wellman. 2014. Social Network Analysis: An Introduction. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis. Edited by John Scott and Peter J. Carrington. London: SAGE Publications, pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Steven E. 2016. Social Network Analysis of the Biblical Moses. Applied Network Science 1: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, Esias E. 2015. People and Land in the Holiness Code: Who Is YHWH’s Favourite? Old Testament Essays 28: 433–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, Franco. 2011. Network Theory, Plot Analysis. New Left Review 68: 80–102. [Google Scholar]

- Næss, Åshild. 2007. Prototypical Transitivity. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Mark E. J., and Michelle Girvan. 2004. Finding and Evaluating Community Structure in Networks. Physical Review E 69: 026113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padgett, John F., and Christopher K. Ansell. 1993. Robust Action and the Rise of the Medici, 1400–1434. American Journal of Sociology 98: 1259–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Lawrence, Sergey Brin, Rajeev Motwani, and Terry Winograd. 1998. The PageRank Citation Ranking: Bringing Order to the Web. Stanford Digital Library Working Paper SIDL-WP-1999-0120. Stanford: Stanford InfoLab. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, Fabian, Gaël Varoquaux, Alexandre Gramfort, Vincent Michel, Bertrand Thirion, Olivier Grisel, Mathieu Blondel, Peter Prettenhofer, Ron Weiss, Vincent Dubourg, and et al. 2011. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 12: 2825–30. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, John. 2017. Social Network Analysis, 4th ed. London and Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, John, and Peter Carrington. 2014. The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talstra, Eep. 2018. Participant Tracking Dataset of Leviticus 17–26. Version 1.01. Geneva: Zenodo. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Jie. 2017. Computational Models for Social Network Analysis: A Brief Survey. Paper presented at the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web Companion, Perth, Australia, April 3–7; Geneva: ACM Press, pp. 921–25. [Google Scholar]

- Waerzeggers, Caroline. 2014. Social Network Analysis of Cuneiform Archives. A New Approach. In Documentary Sources in Ancient Near Eastern and Greco-Roman Economic History: Methodology and Practice. Edited by Heather D. Baker and Michael Jursa. Oxford and Philadelphia: Oxbow Books, pp. 207–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskom, Michael L. 2021. Seaborn: Statistical Data Visualization. Journal of Open Source Software 6: 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Semantic Role | Agency Score |

|---|---|

| Agent | 5 |

| Force | 4 |

| Affected Agent | 3 |

| Instrument | 2 |

| Frustrative | 1 |

| Neutral | 0 |

| Volitional Undergoer | −1 |

| Patient | −2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Højgaard, C.C. The Social Network of the Holy Land. Religions 2025, 16, 843. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070843

Højgaard CC. The Social Network of the Holy Land. Religions. 2025; 16(7):843. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070843

Chicago/Turabian StyleHøjgaard, Christian Canu. 2025. "The Social Network of the Holy Land" Religions 16, no. 7: 843. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070843

APA StyleHøjgaard, C. C. (2025). The Social Network of the Holy Land. Religions, 16(7), 843. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070843