Translating Medicine Across Cultures: The Divergent Strategies of An Shigao and Dharmarakṣa in Introducing Indian Medical Concepts to China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Earliest Chinese Translation of Yogācārabhūmi

2.1. Background Overview

2.2. Corresponding Content of Chinese Translations in Sanskrit Medical Texts

2.3. Did Dharmarakṣa Refer to An Shigao’s Translations?

3. Different Strategies for Translating Indian Medical Terminology

3.1. Appropriate Timing for Seeking Medical Treatment

3.1.1. Xueji

血忌:丑、未、寅、申、卯、酉、辰、戌、巳、亥、午、子35

Xueji (appearing on the following Earthly Branches): Chou, Wei, Yin, Shen, Mao, You, Chen, Xu, Si, Hai, Wu, Zi.

正月丑、二月未、三月寅、四月申、五月卯、六月酉、七月辰、八月戌、九月巳、十月亥、十一月午、十二月子。右十二日,忌血日也。一名“致忌”。一名“禁忌”。其日不可灸刺,见血忌凶。

First month: Chou, second month: Wei, third month: Yin, fourth month: Shen, fifth month: Mao, sixth month: You, seventh month: Chen, eighth month: Xu, ninth month: Si, tenth month: Hai, eleventh month: Wu, twelfth month: Zi. These twelve days are known as the “blood taboo” days. They are also called Zhiji or Jinji. On these days, acupuncture and any activity involving blood are considered inauspicious.

春心,夏輿鬼,秋婁,冬虛,不可出血若傷,必死。血忌,帝啓百虫口日也。甲寅、乙卯、乙酉不可出血,出血,不出三歲必死。38

In spring: Heart constellation, in summer: Ghost constellation, in autumn: Bond constellation, in winter: Void constellation. (When influenced by these constellations,) bloodletting or injuries are forbidden, as they are believed to be fatal. Xueji days are also the days when the “Di” opens the mouths of a hundred insects. On the days Jiayin, Yimao, and Yiyou, bloodletting is forbidden; if blood is let, death will occur within three years.

如以殺牲見血,避血忌、月殺,則生人食六畜,亦宜辟之。海内屠肆,六畜死者,日數千頭,不擇吉凶,早死者,未必屠工也。天下死罪,冬月斷囚,亦數千人,其刑於市,不擇吉日,受禍者,未必獄吏也。(王充《論衡·譏日》)

If it is believed that the slaughter of livestock and the sight of blood should be avoided on Xueji and Yuesha days, then people consuming livestock should also avoid these days. Across the nation, thousands of livestock are slaughtered daily in butcher shops without regard for auspicious or inauspicious days, yet those who die prematurely are not necessarily the butchers. Similarly, thousands of criminals sentenced to death are executed in the winter months without choosing auspicious days, yet those who suffer misfortune are not necessarily the prison officials. (Wang Chong, Lunheng [Balanced Discourses], “On Criticizing the Selection of Auspicious Days.”)

3.1.2. Siji

入月七日及冬未、春戌、夏丑、秋辰,是胃(謂)四敫,不可初穿門、爲户牖、伐木、壞垣、起垣、徹屋及殺,大凶;利爲嗇夫。(《日書》甲種《門》)

On the seventh day of each month, as well as the Wei day in winter, the Xu day in spring, the Chou day in summer, and the Chen day in autumn, are the so-called “Four Jiao”. On these days, it is highly inauspicious to dig doorways, construct doors and windows, fell trees, demolish walls, build walls, dismantle houses, or kill (livestock?). (However,) they are deemed appropriate for agricultural officials (to carry out their duties) (Rishu jiazhong [Daybook A], “Men [Door].”)41

夏三月丑敫。春三月戊(戌)敫。秋三月辰敫。冬三月未敫……凡敫日,利以漁邋(獵)、請謁、責人、摯(執)盗賊,不可祠祀、殺生(牲)。(《日書》甲種《臽日敫日》)

… In the third month of summer, the Chou day is a Jiao day; in the third month of spring, the Xu day is a Jiao day; in the third month of autumn, the Chen day is a Jiao day; in the third month of winter, the Wei day is a Jiao day… On these Jiao days, fishing, hunting, paying respects, pursuing fugitives, and capturing thieves are appropriate activities, but worship and killing livestock are prohibited. (Rishu jiazhong [Daybook A], “Xianrijiaori [Xian day and Jiao day].”)42

3.1.3. Fanzhi

孝明皇帝嘗問今旦何得無上書者?左右對曰:“反支故。”帝曰:“民既廢農遠來詣闕,而復使避反支,是則又奪其日而寃之也。”乃勅公車受章,無避反支。(王符《潛夫論·愛日》)

Emperor Xiaoming once asked why no memorials had been submitted that morning. His attendants replied, “It is because today is a Fanzhi day.” The Emperor said, “The people have already abandoned their farming and traveled far to the capital, and now we make them avoid Fanzhi days, thus depriving them of their time and causing them unjust suffering. “He then ordered the officials to receive petitions regardless of Fanzhi days. (Wang Fu, Qianfu Lun [Essays of a Recluse], “On Cherishing the Day.”)

“及王莽敗,二人俱客於池陽,竦爲賊兵所殺。”(班固《漢書·陳遵傳》)顏師古注引李奇注:“竦知有賊當去,會反支日,不去,因爲賊所殺。桓譚以爲通人之蔽也。”

“When Wang Mang was defeated, the two men were guests in Chiyang, and Song was killed by bandits.” (Ban Gu, Han shu [Book of Han], “Biography of Chen Zun.”) Yan Shigu’s commentary quoted Li Qi’s annotations: “Song knew there were bandits and planned to leave, but it happened to be a Fanzhi day, so he stayed and was killed by the bandits. Huan Tan believed that even wise people could be misled (by such beliefs).”

世傳術書,皆出流俗,言辭鄙淺,驗少妄多。至如反支不行,竟以遇害;歸忌寄宿,不免凶終:拘而多忌,亦無益也。(顏之推《顏氏家訓·雜藝》)

The divination and fortune-telling books circulating in the world are all produced by common, unsophisticated people, and their content is crude and shallow, with few predictions coming true and many being false. For example, not leaving home on Fanzhi days ultimately leads to harm; encountering taboo days for travel or return and staying overnight en route cannot prevent dying an unnatural death. Adhering too rigidly to these superstitions is ultimately of no benefit. (Yan Zhitui, Yanshi jiaxun (Yan’s Family Instructions), “Miscellaneous Skills.”)

子朔巳亥,丑朔子午,寅朔子午,卯朔丑未,辰朔丑未,巳朔寅甲,午朔寅申,未朔【酉卯,申朔酉卯,酉朔戌辰,戌朔戌辰】亥朔巳亥,是胃(謂)反支。以徙官,十徙;以得憂者,十喜;以亡者,得十;𣪠(繫)囚,亟出。不可冠帶、見人、取(娶)婦、嫁女、入臣妾。不可生歌樂鼓橆(舞),殺畜生見血,人死之,利以出,不利以入,得一失十,以受賀喜,十憂。以[去]入官者,必去。以歐(敺)治(笞)人者,必蓐(辱)。(《日書》乙種《反支》)45

If the first day of a lunar month is Zi, then Si and Hai days are Fanzhi days. If the first day is Chou, then Zi and Wu days are Fanzhi days. If the first day is Yin, then Zi and Wu days are Fanzhi days. If the first day is Mao, then Chou and Wei days are Fanzhi days. If the first day is Chen, then Chou and Wei days are Fanzhi days. If the first day is Si, then Yin and Jia days are Fanzhi days. If the first day is Wu, then Yin and Shen days are Fanzhi days. If the first day is Wei, then You and Mao days are Fanzhi days. If the first day is Shen, then You and Mao days are Fanzhi days. If the first day is You, then Xu and Chen days are Fanzhi days. If the first day is Xu, then Xu and Chen days are Fanzhi days. If the first day is Hai, then Si and Hai days are Fanzhi days. These are termed “Fanzhi” days. On these days, those who are transferred to new positions will be transferred tenfold (in the opposite direction). Encountering sorrowful events will be met with tenfold joy. Lost items will be recovered tenfold. Prisoners who are bound will be released immediately. One should not wear a hat or belt, meet people, marry, arrange marriages for daughters, or purchase male and female servants. Singing, playing music, killing livestock, and seeing blood are also prohibited, as these actions can lead to death. It is favorable to give things away on this day but not to receive them; gaining one thing will result in losing ten. Receiving congratulations will bring tenfold sorrow. Officials holding office on this day are certain to lose their positions, and those who beat or whip others will inevitably be disgraced. (Rishu yizhong [Daybook B], “Fanzhi.”)

3.1.4. Shangxiang: An Early-Stage Scribal Error

〼【爲】上朔,名爲女淉(媧),不可祭祀、訶(歌)藥(樂)、行、作事、𢱭(拜)受爵,必有大咎,百事莫可,女子之事蜀(獨)甚。(《陰陽五行甲篇》雜占之二《上朔》)52

… is the Shangshuo day, (and the deity influencing this day) is called Nüwa. It is forbidden to perform sacrifices, sing, play music, travel, undertake tasks, or receive titles. Such actions bring great misfortune, and all activities should be avoided, especially those related to women. (Yin yang wuxing A, Miscellaneous Divinations II, “Shangshuo.”)

又云:月建、月殺、反支、天季、上朔、自刑日,此不可用。自刑日者,如寅生人不得用寅和藥、服藥,他准此。(《醫心方》卷二《針灸服藥吉凶日第七》引《大清經》)53

It is also said: Yuejian, Yuesha, Fanzhi, Tianji, Shangshuo, and Zixing days are unsuitable (for medicine). On Zixing (self-injury) days, such as when a person born on a Yin day cannot prepare or take medicine on a Yin day, this rule applies accordingly. (Taiqing jing cited in Ishinpō, Volume 2, “Seventh Section on Auspicious and Inauspicious Days for Acupuncture and Medicine.”)

春戊辰,夏丁已、戊申、己巳、丑未辰,秋戊戌、已亥、辛亥、庚子,冬戊寅、己卯、癸酉、未戌,及壬丙、戊丁、亥土、戌癸、辛巳、日建、日殺、反支、天季、孟仲季月收閉、晦朔、上朔、八魁、往亡、留後日,皆凶,作藥不成矣。……(《三十六水法·作丹忌日》)54

In spring: Wuchen; in summer: Dingyi, Wushen, Jisi, Chouwei; in autumn: Wuxu, Yihai, Xinhei, Gengzi; in winter: Wuyin, Jimao, Guiyou, Weixu; as well as Renbing, Wuding, Haitu, Xujue, Xinsi, Riji, Risha, Fanzhi, Tianji, the end of the first, second, and third months of each season, dark moon, new moon, Shangshuo, Bakui, Wangwang, and Liuhou days are all inauspicious and will result in failed medicine preparation… (Sanshiliu shui fa [A Guide on Preparing Thirty-six Types of Divine Water], “prohibited days for making elixirs.”)

3.1.5. Early Chinese Buddhism and An Shigao’s Expertise

戊己、丙丁、庚辛旦行,有二喜。甲乙、壬癸、丙丁日中行,有五喜。庚辛、戊已、壬癸餔时行,有七喜。壬癸、庚辛、甲乙夕行,有九喜。己酉從遠行入,有三喜。(《日書》甲種《禹須臾》)

If traveling at dawn on Wuji, Bingding, Gengxin days, two auspicious events will occur. If traveling at noon on Jiayou, Renji, Bingding days, five auspicious events will occur. If traveling at dusk on Gengxin, Wuxi, Renji days, seven auspicious events will occur. If traveling at night on Renji, Gengxin, Jiayou days, nine auspicious events will occur. If entering home from a long journey on a Jiyou day, three auspicious events will occur. (Rishu jiazhong, “Yu xuyu.”)

其為人也,博學多識,貫綜神谋、七正、盈縮、風氣、吉凶、山崩、地動、鍼䘑諸術,覩色知病,鳥獸鳴啼,無音不照。58

He was a man of prodigious learning. He had mastered the full range of divinatory and therapeutic arts: celestial “numinous calculations,” the Seven Regulators that chart the movements of the heavens, techniques for gauging (or prolonging) the span of human life, wind-based augury that reads the four-quarters’ currents for omens of good or ill, the scrutiny of auspicious and inauspicious signs, portents of landslides and earthquakes, and the skills of acupuncture and moxibustion. By a mere glance at a person’s complexion he could diagnose hidden illnesses, and from the cries of birds and beasts he could interpret every omen—there was no sound whose meaning eluded him.

七曜五行之象、風角雲物之占、推步盈縮,悉窮其變;兼洞曉醫術,妙善鍼䘑,覩色知病,投藥必濟,乃至鳥獸嗚呼,聞聲知心。59

He excelled in divination through observing the seven stars, five elements, wind directions, and cloud colors. He was proficient in astronomical calendars and predicting lifespans. Additionally, he was skilled in medicine and acupuncture, able to diagnose illnesses by observing a person’s complexion, and his prescribed medicines were always effective. He could even understand the sounds of birds and beasts.

3.2. Medical Specializations and Renowned Physicians

如是病痛相,不可治,設鶣鵲亦一切良醫并祠祀盡會,亦不能愈是。62

After the patient has shown the aforementioned symptoms, it means that he is beyond saving. Even if renowned physicians and wizards like Bian Que were to come, they could not cure him.

- “Body treatment” (療身病, equivalent to kāyacikitsitā, general internal medicine);

- “Treatment of ears and eyes” (主治耳目, śālākya, otorhinolaryngology);

- “Treatment of wounds” (瘡醫, śalya, surgery);

- “Pediatrics” (小兒醫, kaumārabhṛtya);

- “Demonology” (鬼神醫, bhūtavidyā, exorcism and psychiatry).

3.2.1. Leading Figures in Each Branch

3.2.2. Other Notable Figures

3.2.3. Dharmarakṣa’s Translation Strategies and Audience Adaptation

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | See Needham (2000, pp. 57–58, 162–64, 165–66). Apart from the testimony found in transmitted sources—such as Buddhist scriptures and classical Chinese medical treatises—a wealth of manuscripts excavated along the Silk Road likewise attests to medical exchanges among China, India, and the Western Regions. M. Chen (2017, pp. 205–25) offers a fairly comprehensive survey of this evidence. |

| 2 | It appears that the full details of Saṅgharakṣa are preserved only in the Chinese Tripiṭaka. For a thorough historical analysis of Saṅgharakṣa and his Yogācārabhūmi, see Demiéville (1954) and Deleanu (1997). |

| 3 | Demiéville (1954), in his landmark study of the Yogācārabhūmi text, provided a thorough analysis of its authorship, historical and doctrinal importance, and its profound influence on the evolution of Chinese Dhyāna (Zen) Buddhism. Additionally, he offered a concise review of its three Chinese translations—T607, T606, and T608. Subsequent studies by Ui (1971, pp. 411–36) and Deleanu (1997) further explored the content and doctrinal positions of the Yogācārabhūmi by comparing these parallel texts, focusing primarily on T607 and T606. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | A typical example is T13 Chang ahang shibaofa jing 長阿含十報法經, which can be compared with its Sanskrit parallel, the Daśottarasūtra, and its Pali counterpart, the Dasuttarasutta. |

| 6 | In the southern editions of the Buddhist canon, T606 is followed by an epilogue of unknown authorship, which provides a detailed account of the translation’s date and participants: 罽賓文士竺侯征……齎此經本來至燉煌。是時月支菩薩沙門法護……於此相值共演之。其筆受者,菩薩弟子沙門法乘、月氏法寶、賢者李應榮、承索烏子、剡遲時、通武、支晉、支晉寶等三十餘人,咸共勸助,以太康五年二月二十三日始訖。(“The scholar Zhu Houzheng from Jibin… brought this text to Dunhuang. At that time, the Yuezhi Bodhisattva monk Dharmarakṣa… met him and they collaborated on its translation. The scribes included the bodhisattva disciples, the monks Fasheng, Fabao from Yuezhi, the venerable Li Yingrong, Chengsuowuzi, Shan Chishi, Tongwu, Zhi Jin, and Zhi Jinbao, among others, totaling more than thirty individuals. They all contributed to the effort, which was completed on the twenty-third day of the second month in the fifth year of the Tai Kang era.”) It should be noted that the personal names here are difficult to segment accurately. Therefore, I have followed the punctuation provided by Tang ([1938] 2011, pp. 90–91). |

| 7 | Dao’an seems to believe that T607 originates from a foreign original text that had already been abridged at the source. (《大道地經》二卷。安公云:《大道地經》者,《修行經》抄也,外國所抄。CBETA, T55, no. 2145, p. 5, c28–29). However, Sengyou 僧祐 suggested that this abridgment was undertaken by An Shigao himself (抄經者,蓋撮舉義要也。昔安世高抄出《修行》為《大道地經》,良以廣譯為難,故省文略說。及支謙出經亦有《孛抄》,此並約寫胡本,非割斷成經也。“Abridged texts likely aimed to extract the essential meaning. An Shigao once condensed the Yogācārabhūmi into the Da daodi jing, simplifying the text due to the difficulty of a comprehensive translation. By the time of Zhi Qian’s translations, he also created works like the Bei chao, which were abridged versions of foreign originals rather than excerpts.” CBETA, T55, no. 2145, p. 37, c1–4). Nonetheless, T607 is not a condensed version of the entire T606 Xiuxing daodi jing but corresponds only to its beginning. The reasons for this “selection” are unclear, whether due to the nature of the original text or some unfinished work by An Shigao. A similar issue arises with An Shigao’s T603 Yin chi ru jing, which only corresponds to part of the sixth chapter of its Pali counterpart, the Peṭakopadesa (see Zacchetti 2002). |

| 8 | Nearly all discussions of T607 involve comparative reading with T606. Deleanu (1997) and Ui (1971, pp. 431–36) attempt to resolve some problematic terms through textual comparison. Ui (1971, pp. 411–31) provided a full Japanese translation of T607 but acknowledges in the annotations that many terms remain unclear. Deleanu (1997) provides a comparative analysis of the translations by An Shigao and Dharmarakṣa, highlighting differences in content and structure that may be due to variations in source texts, translation techniques, or editorial decisions. He further contributes valuable interpretations of certain terms, though some of these remain questionable in my view. For example, both Ui (1971, p. 433) and Deleanu (1997, p. 36) suggest that the “Liu zu jing” (六足經) mentioned in T607 might refer to the Ṣaṭpādābhidharma (i.e., the six Sarvāstivāda treatises, metaphorically described as the “feet” supporting the “body” (體) represented by Kātyāyanīputra’s Abhidharmajñānaprasthāna-śāstra). However, this interpretation may be an over-reading. It seems more plausible that “six-legged” (六足) here is simply a literal translation of ṣaṭpada (bee) and does not form a compound with “jing” (經). Compare T607: “六足經蜜” (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 231, c12) with Dharmarakṣa’s translation in T606: “譬蜂採華味” (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 183, a20). |

| 9 | There is considerable debate regarding the dating of the Caraka-saṃhitā. Meulenbeld (1999, p. 105) summarizes this discussion, noting that, since Bhartṛhari referenced it, the text must have been completed no later than his death (651/652 AD). Furthermore, through records in the Chinese translation of the T203 Za baozang jing 雜寶藏經, it is evident that Caraka was known as a physician at least by the time of King Kaniṣka (around the late 1st to early 2nd century CE). |

| 10 | Meulenbeld (1999, pp. 331–52) summarizes the discussions on this matter and suggests that the Suśrutasaṃhitā might contain multiple historical layers, with its formation potentially beginning in the last few centuries BCE. The extant Suśruta-saṃhitā should date to at least the time of Dṛḍhabala (active approximately 300–500 CE). |

| 11 | Meulenbeld (1999, pp. 613–35) dates the formation of the Aṣṭāṅgahṛdaya to after the Caraka-saṃhitā and Suśruta-saṃhitā but before the Mādhavanidāna (7th century). |

| 12 | The period from its inception to its present form spans approximately 700–800 to 1000–1100 CE (see Rocher 1986, pp. 136–37). |

| 13 | It might be the oldest Purāṇa, likely formed around the 4th to 5th centuries CE. See Rocher (1986, p. 245). |

| 14 | The content of the Skanda Purāṇa is relatively larger and more complex (the content discussed in my study mainly comes from SP. 4.1.42). The earliest known Skanda Purāṇa is a palm-leaf manuscript written in Gupta script, discovered by Haraprasad Shastri and Cecil Bendall around 1898. Based on the script, it is determined to have been formed before 659 CE. See Rocher (1986, p. 237). |

| 15 | Premonitory dreams are a recurring theme in Indian epic, religious, and medical literature, where certain dream scenes are believed to foretell imminent death. Beyond the texts discussed in this study, similar accounts of dreams containing auspicious or inauspicious omens can be found in the Ayodhyākāṇḍa and Sundarakāṇḍa of the Rāmāyaṇa, as well as in chapters 258–275 of the Āraṇyakaparvan in the Mahābhārata. For further discussion, see De Clercq (2009). |

| 16 | An Shigao’s T607: 死人亦擔死人亦除溷人共一器中食;亦見是人共載車行。(CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 232, a27–28) Dharmarakṣa’s T606: 夢與死人、屠魁(=屠膾)、除溷者共一器食,同乘遊觀。(CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 183, c10–11) The differences between Dharmakṣema’s T374 and the above two are more pronounced, with two relevant passages: 或與獼猴遊行坐臥。(CBETA, T12, no. 374, p. 481, c2) 復與亡者行住坐起,携手食噉。(CBETA, T12, no. 374, p. 481, c5–6) Cf. the following Sanskrit texts: Ca.5.5.17 snehaṃ bahuvidhaṃ svapne caṇḍālaiḥ saha yaḥ pibet Su.1.29.64 …śunā sakhyaṃ kapisakhyaṃ… rākṣasaiḥ pretair… AP.228.12 krīḍā piśācakravyādavānarāntyanarair |

| 17 | An Shigao’s T607: 麻油、污泥污足亦塗身;亦見是時時飲。(CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 232, a28–29) Dharmarakṣa’s T606: 或以麻油及脂、醍醐自澆其身,又服食之,數數如是。(CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 183, c11–12) Dharmakṣema’s T374: 服蘇油脂及以塗身。(CBETA, T12, no. 374, p. 481, c1) Cf. the following Sanskrit texts: Ca.5.5.33 snehapānaṃ tathābhyaṅgaḥ Su.1.29.65 …-pānaṃ snehasya AP.228.14 snehapānāvagāhau |

| 18 | An Shigao’s T607: 亦狗、猴亦驢,南方行。(CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 232, b17) Dharmarakṣa’s T606: 或乘驢狗而南遊行。(CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 184, a5–6) Dharmakṣema’s T374: 乘壞驢車正南而遊。(CBETA, T12, no. 374, p. 481, c8) Cf. the following Sanskrit texts: Ca.5.5.37 raktamālī … dakṣiṇāṃ diśam | dāruṇām aṭavīṃ svapne kapiyuktena yāti vā Ca.5.5.8 śvabhir uṣṭraiḥ kharair vāpi yāti yo dakṣiṇāṃ diśam AH.2.6.42 mahiṣaśvavarāhoṣṭragardabhaiḥ | yaḥ prayāti diśaṃ yāmyāṃ AH.2.6.46–47 yānaṃ kharoṣṭramārjārakapiśārdūlasūkaraiḥ yasya pretaiḥ śṛgālair vā AP.228.5 varāhaśvakharoṣṭrāṇāṃ tathā cārohaṇakriyā AP.228.11 dakṣiṇāśāpragamanaṃ VP.19.13 ṛkṣavānarayuktena rathenāśāṃ tu dakṣiṇāṃ gāyann atha vrajet VP.19.27 uṣṭrā vā rāsabhā vāpi yuktāḥ svapne rathe … dakṣiṇābhimukho gataḥ |

| 19 | An Shigao’s T607: (null) Dharmarakṣa’s T606: 體多垢穢。(CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 184, a18) Dharmakṣema’s T374: 頭蒙塵土。(CBETA, T12, no. 374, p. 481, c10–11) Cf. the following Sanskrit texts: Su.1.29.14 deśe tv aśucau AH.2.6.3 malinaṃ AH.2.6.4 tailapaṅkāṅkitaṃ |

| 20 | An Shigao’s T607: 不潔惡衣。(CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 232, b25) Dharmarakṣa’s T606: 衣被弊壞。(CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 184, a18) Dharmakṣema’s T374: 著弊壞衣。(CBETA, T12, no. 374, p. 481, c11) Cf. the following Sanskrit texts: Ca.5.12.67 śuklavāsasam (as a good omen) Su.1.29.6 …-jīrṇa-…malina-…-vāsasaḥ AH.2.6.4 jīrṇavivarṇārdraikavāsasam AP.294.26 vivarṇavāsāḥ |

| 21 | An Shigao’s T607: 自手摩抆鬚髮。(CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 232, b27) Dharmarakṣa’s T606: 而數以手摩抆鬚髮。(CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 184, a20–21) Dharmakṣema’s T374: (null) Cf. the following Sanskrit texts: Ca.5.12.19–20 …keśa… spṛśanto … Su.1.29.8 -keśa- … -spṛśaḥ AH.2.6.8 spṛśanto…-keśaroma-… |

| 22 | An Shigao’s T607: 視南方,復見烏、鵄巢有聲。(CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 232, c15) Dharmarakṣa’s T606: 南方狐鳴,或聞烏、梟聲。(CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 184, b16–17) Dharmakṣema’s T374: 復聞南方有飛鳥聲,所謂烏鷲、舍利鳥聲,若狗、若鼠、野狐、兔、猪。(CBETA, T12, no. 374, p. 482, a6–8) Cf. the following Sanskrit texts: Ca.5.12.29 mṛgadvijānāṃ krūrāṇāṃ giro dīptāṃ diśaṃ prati Su.1.29.35 dīptakharasvarāḥ | purato dikṣu dīptāsu vaktāro AH 2.6.19 dīptāṃ prati diśaṃ vācaḥ krūrāṇā mṛgapakṣiṇām |

| 23 | An Shigao’s T607 and Dharmarakṣa’s T606: (null) Dharmakṣema’s T374: 見人持火自然殄滅。(CBETA, T12, no. 374, p. 481, c25–26) Cf. the following Sanskrit texts: Ca.5.12.38 … jyotiś caivopaśāmyati nivāte sendhanaṃ … AH 2.5.126–127 nivāte sendhanaṃ yasya jyotiś cāpy upaśāmyati āturasya gṛhe yasya … |

| 24 | An Shigao’s T607: (null) Dharmarakṣa’s T606: 眼睫為亂。(CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 184, b23) Dharmakṣema’s T374: (null) Cf. the following Sanskrit texts: Ca.5.8.4 jaṭībhūtāni pakṣmāṇi Ca.5.3.6 tasya cet pakṣmāṇi jaṭābaddhāni syuḥ Ca.5.12.55 jaṭāḥ pakṣmasu Su.1.31.10 luṇḍanti câkṣipakṣmāṇi AH.2.5.8 lulita pakṣamaṇī |

| 25 | An Shigao’s T607: 鼻頭曲戾,皮黑咤幹。(CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 232, c22) Dharmarakṣa’s T606: 鼻孔騫黃,顏彩失色。(CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 184, b24) Dharmakṣema’s T374: (null) Cf. the following Sanskrit texts: Ca.5.10.5 jihmīkṛtya ca nāsikām Su.1.31.8 kuṭilā sphuṭitā vāpi śuṣkā vā yasya nāsikā VP.19.23 vakrā ca nāsā bhavati AH.2.5.8–9 nāsikā ’tyarthavivṛtā saṃvṛtā piṭikācitā || ucchūnā skhuṭitā mlānā AH.2.5.104 nāsāṃ ca jihmatām |

| 26 | An Shigao’s T607: 牽髮不復覺。(CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 232, c23–24) Dharmarakṣa’s T606: 捉髮搯鼻,都無所覺。(CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 184, b26) Dharmakṣema’s T374: (null) Cf. the following Sanskrit texts: Ca.5.3.6 athāsya keśalomāny āyacchet tasya cet keśalomāny āyamyamānāni pralucyeran na ced vedayeyus Ca.5.8.8 āyamyotpāṭitān keśān yo naro nāvabudhyate AH.2.5.67 keśaluñcanavedanām |

| 27 | The text here contains numerous scribal errors, which I have indicated using the notation A (←B), where the original text uses the character B, but it appears to be a scribal error for the character A: An Shigao’s T607: 便醫意念:“是病痛命未(←求)絕,應當避已。”便告家中人言:“是病所求(←未)所思欲,當隨意與,莫制禁,我家中有小事,事竟當還(←遠)。”屏語病者家人言:“不可復治。”告已便去。(CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 233, a11–15) Dharmarakṣa’s T606: 醫心念言:“曼命未斷,當避退矣!”便語眾人:“今此病者,設有所索,飯食美味,恣意與之,勿得逆也!吾有急事而相捨去,事了當還。”故興此緣,便捨退去。於是頌曰:命欲向斷時,得病甚困極,與塵勞俱合,罪至不自覺。怪變自然起,得對陰熟(←熱)極,正使執金剛,不能濟其命。(CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 185, b9–16) Dharmakṣema’s T374: 爾時良醫見如是等種種相已,定知病者必死不疑,然不定言是人當死,語瞻病者:“吾今劇務,明當更來,隨其所須,恣意勿遮。即便還家。明日使到,復語使言:“我事未訖,兼未合藥。”智者當知,如是病者,必死不疑。(CBETA, T12, no. 374, p. 482, a24–28) Cf. the following Sanskrit texts: Ca.5.12.62 maraṇāyeha rūpāṇi paśyatā ’pi bhiṣagvidā | apṛṣṭena na vaktavyaṃ maraṇaṃ pratyupasthitam || Ca.5.12.63 pṛṣṭenāpi na vaktavyaṃ tatra yatropaghātakam | āturasya bhaved duḥkham athavānyasya kasya cit || Ca.5.12.64 abruvan maraṇaṃ tasya naỿnam icchec cikitsitum | yasya paśyed vināśāya liṅgāni kuśalo bhiṣak || AH.2.5.129 kathayen na ca pṛṣṭo ’pi duḥśrava maraṇaṃ bhiṣak | gatāsor bandhumitrāṇāṃ na cec chettaṃ cikitsitum || |

| 28 | For example, Zhi Qian’s T225 Da mingdu jing 大明度經 mainly revised the earlier translation T224 道行般若經 by Lokakṣema, changing the colloquial style to a more elegant Chinese and translating certain transliterated terms more accurately, though Zhi Qian probably also had a Sanskrit original as a reference (see Zürcher 1991, pp. 280–81; Nattier 2010, pp. 309–17; Karashima 2011). |

| 29 | There is still controversy over whether certain extant translations were performed by Zhi Qian or Dharmarakṣa (or revised by the latter), such as T474 Weimojie jing 維摩詰經, T558 Longshi pusa benqi jing 龍施菩薩本起經, T361 Wuliang qingjing pingdeng jue jing 無量清淨平等覺經, and T362 Da amituo jing 大阿彌陀經 (see Nattier 2008, pp. 86–87, 140; Radich 2019). |

| 30 | Notably, Dao’an’s preface makes no mention of Dharmarakṣa’s translation. Fang (2004, pp. 105–6) suggests that this preface was likely written during Dao’an’s period of refuge in Huozhou, around 360 CE, a time when he may not yet have had access to Dharmarakṣa’s version. It was only later, after Dao’an relocated to Xiangyang and began compiling the Zongli zhongjing mulu, that he likely encountered Dharmarakṣa’s translation. Both Link (1957) and Fang (2004, pp. 106–7) point out that in his Daodi jing xu 道地經序 (Preface to the Daodi jing), Dao’an extensively borrowed Daoist terminology, indicating that he had not fully moved away from the geyi 格義 (matching concepts) method that he otherwise criticized. For a detailed discussion of Dao’an’s preface and its translation into modern language, see Link (1957) and Ui (1956, pp. 63–72). |

| 31 | CBETA, T55, no. 2145, p. 69, b21–23. |

| 32 | However, all three Chinese translations seem to overlook a critical issue: the dates in Sanskrit medical texts are based on a fortnightly cycle, from new moon to full moon (śuklapakṣa, 白分 “bright half”) and from full moon to the next new moon (kṛṣṇapakṣa, 黑分 “dark half”), with dates typically less than fifteen. For instance, “ṣaṣṭhī” (the sixth tithi) could be either the sixth day or the twenty-first day of the month. |

| 33 | In volume two of the Chu sanzang ji ji, it is recorded that Dharmarakṣa translated a one-volume text called “Hu’eryi jing,” also known as the “Ershiba xiu jing” (“《虎耳意經》一卷(一名《二十八宿經》)”). However, Sengyou believed that this text had already been lost at that time. In volume four, there is a record of an anonymous one-volume sutra titled “Shetoujian taizi ershiba xiu jing,” which notes that the “Old Catalog” refers to it as “Shetoujian jing” or “Hu’er” (“《舍頭諫太子二十八宿經》一卷(舊錄云《舍頭諫經》,一名《虎耳》)”). The T1301 Shetoujian taizi ershiba xiu jing 舍頭諫太子二十八宿經 in the Taishō Canon is currently attributed to Dharmarakṣa. I tend to believe this attribution is correct, not only because its title closely resembles that of Dharmarakṣa’s translation as recorded in the Chu sanzang ji ji but also because T1301 contains many unique terms and expressions that are strongly characteristic of Dharmarakṣa’s style, which are rarely found in the works of other translators (I will discuss several such examples in Section 3.2 of this study). This suggests that the extant T1301 was likely translated by Dharmarakṣa himself, or it could have been modified based on his original translation. In the Lidai sanbao ji 歷代三寶紀 by Fei Zhangfang 費長房 of the Sui dynasty, the Shetoujian jing was erroneously attributed to An Shigao, an attribution later corrected by Zhisheng 智昇 in the Kaiyuan shijiao lu 開元釋教錄. The extant T1301 is attributed to Dharmarakṣa, though its attribution has been questioned by scholars such as Mei (1996). Despite these doubts, an analysis of the translation of proper nouns and terms in both T1301 and T606 suggests a strong connection to Dharmarakṣa (see Section 3.2 for further discussion), and it is well established that Dharmarakṣa had previously translated a Chinese version of the Śārdūlakarṇāvadāna. The names of the constellations mentioned in Suśruta-saṃhitā (1.29.17) and Aṣṭāṅga Hṛdaya (2.6.11–12) also appear in T1301. Notably, in T1301, Dharmarakṣa often substituted the constellation names with the names of their chief deities. For instance, Kṛttikā, whose chief deity is Agni, is translated as “Fire God” (火天). For additional discussion, see Zhou (2020, pp. 115–16). |

| 34 | The Xieji bianfang shu 協紀辨方書, compiled in 1739, is a significant work in this field. However, since many methods for calculating deities and determining auspicious and inauspicious activities have changed, this study primarily uses materials from An Shigao’s era as evidence, with later almanacs serving as supplementary sources. |

| 35 | 73EJT23:316. |

| 36 | The Huangdi hama jing has been lost in China; the extant version is part of the Eisei eihen 衛生彙編 published in Japan in 1823. The Ishinpō 醫心方, compiled by Japanese scholar Tanba Yasuyori 丹波康赖 (912–995 CE), includes 46 sections from the Hama jing, preserving some content not found in the current edition. In the preface to Hama jing written in the fourth year of the Bunsei era (1821), Tanba Mototaka noted: “The Taiping Yulan cites the Baopuzi, which states: ‘The Huangdi Jing contains the Frog Diagram, describing that when the moon begins to wax on the second day, frogs begin to emerge, and humans should avoid acupuncture at that time’” (《太平御覽》引《抱朴子》曰:《黃帝經》有《蝦蟆圖》,言月生始二日,蝦蟆始生,人亦不可針灸其處). This indicates that the text was already in circulation during the Jin and Song dynasties. For further examination of its composition period, see Zhu (2011) and J. Liu (2016). |

| 37 | The bamboo slips housed in the Art Museum of the Chinese University of Hong Kong also record a very similar correlation between Xueji and constellations (see S. Chen 2001, p. 38). As Cheng (2015, pp. 140–41) points out, although earlier scholarship generally believed that the computation of Xueji days remained stable from the Han dynasty to the Qing dynasty, excavated texts such as the Kongjiapo Han slips reveal considerable complexity and variation in these reckoning techniques. |

| 38 | (For the transcription and annotation of this slip text, see Hubei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and Suizhou Archaeological Team (2006, p. 179)). |

| 39 | For all occurrences of Xueji in currently excavated texts and an explanation of this concept, see Zhang (2018, pp. 121–23). For the influence of Han dynasty Xueji on later Daoism and medicine, refer to Jiang (2014). |

| 40 | |

| 41 | |

| 42 | |

| 43 | For all occurrences of Siji or Sijiao in excavated texts, as well as changes in its auspicious and inauspicious connotations in later periods, see Zhang (2018, pp. 105–7). |

| 44 | For all occurrences of Fanzhi in excavated texts and discussions on its calculation methods, see Zhang (2018, pp. 212–14). |

| 45 | The collation and annotation can be found in Sun (2013, pp. 152–53). |

| 46 | For a detailed discussion on the calculation methods of Fanzhi in Qin and Han bamboo slips, see Sun and Lu (2017, pp. 165–68). |

| 47 | The name “Ritingtu” can be found in Lunheng in the section Jieshu 詰術, where Wang Chong argued that the term “Ri” (日) should be interpreted as referring to daily matters (“daily business” 日更用事), rather than the sun (非端端之日名也). Thus, “Riting” refers to the orientation of daily affairs. For a related discussion, see Huang (2013, pp. 54–57). |

| 48 | Xieji bianfang shu, Volume 6, entry on “Shangshuo,” citing the Lifa 曆法 (Calendar Methods). |

| 49 | ibid., citing the Kanyu jing 堪輿經 (Classic of Geomancy). |

| 50 | Wang Chong, Lunheng, “On Discerning Spirits (辨祟).” |

| 51 | |

| 52 | For the compiled edition, refer to Qiu (2014, p. 73). |

| 53 | The Taiqing jing is now lost, and its date of composition and compiler are unknown. Baopuzi neipian 抱朴子內篇 cited the Taiqing jing in different section. For more information on the Taiqing jing and its commentaries, refer to Pregadio (2005, pp. 54–55). |

| 54 | The dating of the Sanshiliu shui fa is quite complex. It is generally believed to have been composed during the Western Han period, but it underwent revisions in later centuries. Ren and Zhong (1995, p. 423) suggests that it might be a work from the Six Dynasties period. |

| 55 | 《後漢書·方術傳序》:“其流又有風角、遁甲、七政、元氣、六日七分、逢占、日者、挺專、須臾、孤虛之術。”李賢注:“須臾,陰陽吉凶立成之法也。今書《七志》有《武王須臾》一卷。” (“Xuyu is a method for determining auspicious and inauspicious outcomes through Yin and Yang. The Seven Catalogs list a one-volume text titled Wuwang Xuyu.”). |

| 56 | For the collation and annotation of the Yu xuyu, see W. Chen (2016, pp. 390–91, 454–55). For all occurrences of Yu xuyu in excavated texts, along with an explanation of its meaning and related divination methods, see Zhang (2018, pp. 219–21). |

| 57 | The Keyi chapter of the Zhuangzi contains one of the earliest textual references to breath regulation as a means of prolonging life: 吹呴呼吸,吐故納新,熊經鳥申,為壽而已矣 (“They blow, exhale, inhale, and draw in fresh breaths while expelling the old; they stretch like bears and extend like birds—such exercises are practiced merely in the pursuit of longevity”). This notion of nourishing life through controlled breathing and physical movement is further illuminated by archaeological discoveries such as the Quegu shiqi 卻谷食氣, Daoyin tu 導引圖, and Yinshu 引書 manuscripts unearthed at Mawangdui and Zhangjiashan, as well as breath-regulation (xingqi 行氣) inscriptions on jade artifacts from the Warring States period. These materials offer a much fuller picture of how such techniques were concretely practiced in early China. For a comprehensive overview, see Harper ([1998] 2009, pp. 24–25). |

| 58 | CBETA, T15, no. 602, p. 163, b23–26. |

| 59 | CBETA, T55, no. 2145, p. 95, a10–13. |

| 60 | 及七曜五行、醫方異術,乃至鳥獸之聲,無不綜達。(CBETA, T50, no. 2059, p. 323, a26–27). |

| 61 | Since neither of these two translated texts is listed among An Shigao’s works in the Chu sanzang ji ji, modern scholars generally consider them unreliable attributions to An Shigao. For a detailed discussion of T553 and T701 from the perspective of Buddhist medicine, see Salguero (2014, pp. 46–47, 76–78, 126–28). For a more comprehensive examination of the attribution of T553, refer to Salguero (2009, pp. 186–89). |

| 62 | CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 233, a10–11. |

| 63 | |

| 64 | 《史記·扁鵲倉公列傳》:“扁鵲名聞天下。過邯鄲,聞貴婦人,即爲帶下醫;過洛陽,聞周人愛老人,即爲耳目痹醫;來入咸陽,聞秦人愛小兒,即爲小兒醫。” (“Bian Que’s reputation spread across the land. When he passed through Handan, upon hearing that women were highly regarded, he became a gynecologist; when he passed through Luoyang, upon learning that the Zhou people valued the elderly, he became an ophthalmologist and specialist in treating paralysis; and when he arrived in Xianyang, upon discovering that the Qin people cherished children, he became a pediatrician.”). |

| 65 | The three branches not mentioned are agadatantra (toxicology), rasāyanatantra (rejuvenation therapies), and vājīkaraṇatantra (aphrodisiacs and fertility treatments). |

| 66 | CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 185, b3–4. |

| 67 | The regional vernacular elements of early Buddhist scriptures were gradually Sanskritized over time. In the early stages of Chinese translation of Buddhist scriptures, many translations still retained features of Middle Indic languages. For example, the differences between Dharmarakṣa’s translation of the Zhengfa hua jing (正法華經) and the Sanskrit Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra can often be explained by semantic divergences arising from confusion between Middle Indic languages (particularly Gāndhārī) and Sanskrit. For further discussion, see Boucher (1996, pp. 103–56), Boucher (1998), and Karashima (2006). |

| 68 | Atri is cited as an authoritative figure throughout the Brahmanical corpus, from the early Vedic hymns to the later Smṛti literature. Ṛg-veda 5.40.6 proclaims: … gūḻhaṃ sūryaṃ tamasāpavratena turīyeṇa brahmaṇāvindad atriḥ—“… Atri with the fourth formulation found the sun, hidden by darkness because of (an act) contrary to commandment” (Eng. trans. Jamison and Brereton 2014, p. 740). Mānava-Dharmaśāstra 1.34–35 likewise declares: ahaṃ prajāḥ sisṛkṣus tu tapas taptvā suduścaram | patīn prajānām asṛjaṃ maharṣīn ādito daśa || marīciṃ atry-aṅgirasau pulastyaṃ pulahaṃ kratum | pracetasaṃ vasiṣṭhaṃ ca bhṛguṃ nāradam eva ca ||—“Desiring to bring forth creatures, I heated myself with the most arduous ascetic toil and brought forth in the beginning the ten great seers, the lords of creatures: Marīci, Atri, Aṅgiras, Pulastya, Pulaha, Kratu, Pracetas, Vasiṣṭha, Bhṛgu, and Nārada.” (Eng. trans. Olivelle 2005, p. 88). Because Atri thus stands both as a Vedic mantra-seer and a primordial progenitor, the early Āyurvedic literature—including the Caraka-saṃhitā—traces its medical pedigree to his line, presenting the legendary physician Punarvasu Ātreya (“descendant of Atri”) as the founding teacher of the Kāyacikitsā (internal medicine) school and a principal authority for subsequent medical tradition. |

| 69 | “Ātreya-saṃpradāya”, cf. P. V. Sharma (1992, p. 317). |

| 70 | The Viṣṇu-purāṇa 4.5.9 records that Nimi chose to “dwell in the eyes of all beings” rather than revive his physical body, resulting in the continuous blinking of the eyes of all living creatures. For the English translation by Horace Hayman Wilson and the original Sanskrit text, refer to Joshi (2020, p. 332). Additionally, a lost Śālākya treatise, Nimi-tantra, is referenced in other sources (see P. V. Sharma 1992, p. 313; Meulenbeld 1999, pp. 171–73). |

| 71 | Although, traditionally, the meaning of Jātūkarṇa has been understood as “bat ear,” see Monier-Williams’s Sanskrit-English Dictionary. |

| 72 | Car 1.1.30–31: atha maitrīparaḥ puṇyamāyurvedaṃ punarvasuḥ | śiṣyebhyo dattavān ṣaḍbhyaḥ sarvabhūtānukampayā || agniveśaśca bhelaś ca jatūkarṇāḥ parāśaraḥ | hārītaḥ kṣārapāṇiśca jagṛhustanmunervacaḥ ||. |

| 73 | CBETA, T55, no. 2145, p. 98, a9–10. |

| 74 | For an overview of Dharmarakṣa’s translation activities, see Zürcher ([1972] 2007, pp. 67–69) and Boucher (2006). |

| 75 | Ui (1971, p. 434) also provides several similar examples. For instance, T606 adopts the term “Five Lakes and Nine Rivers” (五湖九江) from T607, which typically refers to China’s rivers and lakes. At the same time, T606 introduces the concept of Tai Shan 太山/大山 (“Mount Tai”), which is absent in T607 and other reliably attributed translations by An Shigao. In medieval China, Mount Tai was regarded as the destination for souls after death. |

| 76 | |

| 77 | This approach is consistent with An Shigao’s general method in his other reliable translations: he tended to use interpretative translations for Buddhist terms, resorting to transliteration only for specific personal and place names. In contrast, other translators from An Shigao’s time, such as Lokakṣema, preferred to transliterate all proper nouns whenever possible, while An Xuan, in his translation of the Ugraparipṛcchā Sūtra, T322 Fajing jing (法鏡經), represented the other extreme by attempting to translate all proper nouns. |

| 78 | See Dao’an’s Preface to the Sūtra of the Twelve Gates (《大十二門經序》): 然世高出經,貴本不飾,天竺古文,文通尚質,倉卒尋之,時有不達 “An Shigao, in translating Buddhist scriptures, prioritized fidelity to the original texts and refrained from rhetorical embellishment. The ancient Indian writings he worked from were composed in a literary style that emphasized simplicity and austerity. As a result, when read hastily, they could at times be difficult to fully grasp.” |

| 79 | In contrast to his praise for An Shigao, Dao’an frequently criticized translators such as Zhi Qian for their overly refined and rhetorically ornate style. See Dao’an’s Preface to the Extracts from the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra (《摩訶鉢羅若波羅蜜經抄序》): 前人出經,支讖世高,審得胡本,難繫者也。叉羅支越,斵鑿之巧者也。巧則巧矣,懼竅成而混沌終矣。“Earlier translators of Buddhist scriptures, such as Lokakṣema and An Shigao, were able to convey the meaning of foreign texts with remarkable fidelity—truly exemplary figures whose achievements are difficult to emulate. In contrast, Mokṣala and Zhi Qian were highly skilled in rhetorical embellishment. While their translations are undeniably elegant and artful, I fear that in carving out too many ‘seven apertures,’ the original simplicity is lost, and the primordial clarity ultimately extinguished.” |

| 80 | See again the Preface to the Sūtra of the Twelve Gates: 此經世高所出也,辭旨雅密,正而不艶,比諸禪經,最為精悉。“This scripture was translated by An Shigao. Its phrasing is elegant and subtle, correct without flamboyance. Compared with other meditation scriptures, it is the most refined and comprehensive.” And also Dao’an’s Preface to the Ren ben yu sheng jing (《人本欲生經序》): 斯經似安世高譯為晉言也,言古文悉,義妙理婉,覩其幽堂之美、闕庭之富,或寡矣。“This scripture appears to have been rendered into Jin Chinese by An Shigao. Its language is fully classical, its meanings are subtle, and its reasoning graceful. The beauty of its hidden structure and the richness of its doctrinal hall—such qualities, alas, are rarely recognized.” |

| 81 | See Huijiao’s Gaoseng zhuan: 安公以為若及面稟,不異見聖。“Master An believed that to have personally received his instruction would have been no different from seeing the Sage [the Buddha].” |

| 82 | 於是有三藏沙門,厥名眾護,仰惟諸行,布在群籍,俯愍發進,不能悉洽,祖述眾經,撰要約行,目其次序,以為一部二十七章。(“At that time, there was a monk named Saṅgharakṣa who believed that various methods of practice were scattered across different scriptures. Out of compassion for those who wished to pursue these practices but were unable to study all the texts, he expounded upon numerous scriptures, distilled their essential teachings, and compiled them into a text consisting of 27 chapters.” CBETA, T55, no. 2145, p. 69, b12–15). Sengyou also provided a brief account in the biographical section on An Shigao: 初外國三藏眾護撰述經要,為二十七章。 (“Saṅgharakṣa, a foreign Tripiṭaka master, originally compiled the essentials of various scriptures into a text comprising 27 chapters.” CBETA, T50, no. 2059, p. 323, b8). |

| 83 | 此土修行經大道地經,其所集也。(“The Xiuxing {jing} da daodi jing in this region (China) were compiled by him (Saṅgharakṣa).” CBETA, T55, no. 2145, p. 71, b5–6). In earlier versions of the Chu sanzang ji ji, such as the Korean edition and the Sixi edition, this preface is attributed to an anonymous author. However, upon closer examination of its content, it seems highly probable that it was penned by Dao’an. The later editions of the Buddhist canon, such as the Puning edition of the Yuan dynasty and the Fangce edtion of the Ming dynasty, explicitly attribute the preface to Dao’an. |

| 84 | Dharmakṣema’s translation includes content not mentioned in T607 and T606 but supported by Sanskrit medical texts, indicating that he likely based his translation on a different source. For example, Table 3 includes the passage: 若是秋時、冬時,及日入時、夜半時、月入時,當知是病亦難可治 “If it is in autumn, winter, sunset, midnight, or moonset, one should know that this illness is also difficult to cure.” Similar cases can be found in Notes 16–27. |

References

- Boucher, Daniel. 1996. Buddhist Translation Procedures in Third-Century China: A Study of Dharmarakṣa and His Translation Idiom. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, Daniel. 1998. Gāndhārī and the Early Chinese Buddhist Translations Reconsidered: The Case of the Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra. Journal of the American Oriental Society 118: 471–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, Daniel. 2006. Dharmarakṣa and the Transmission of Buddhism to China. Asia Major 13: 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Jingfeng 蔡景峰. 1986. Tang yiqian de Zhong-Yin yixue jiaoliu 唐以前的中印醫學交流 [Medical Exchanges between China and India before the Tang Dynasty]. Zhongguo keji shiliao 中國科技史料 [The Chinese Journal for the History of Science and Technology] 7: 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Ming 陳明. 2005. Dunhuang chutu huyu yidian Qipo shu yanjiu 敦煌出土胡語醫典《耆婆書》研究 [A Study of the Dunhuang Discovered Hu-Language Medical Text “Qipo Shu”]. Taipei: Xin Wenfeng Chuban Gongsi 新文豐出版公司. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Ming 陳明. 2017. Silu yiming 絲路醫明 [Medical Culture along the Silk Road]. Guangzhou: Guangdong Education Press 廣東教育出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Songchang 陳松長. 2001. Xianggang Zhongwen Daxue Wenwuguan Cang Jiandu 香港中文大學文物館藏簡牘 [Bamboo and Wooden Slips in the Art Museum Collection]. Hong Kong: Art Museum, The Chinese University of Hong Kong 香港中文大學文物館. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Wei 陳偉, ed. 2016. Qin jiandu heji: Shiwen zhushi xiudingben (Yi, Er) 秦簡牘合集·釋文注釋修訂本(壹、貳)[A Collection of Qin Bamboo Slips: Revised Edition with Annotations (Volumes 1 and 2)]. Edited by Hao Peng 彭浩 and Lexian Liu 劉樂賢. Wuhan: Wuhan Daxue Chubanshe 武漢大學出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Shaoxuan 程少軒. 2015. Jianshui Jinguan Han jian (san) shushu lei jiandu chutan 肩水金關漢簡(叁)術數類簡牘初探 [A Preliminary Study of the Divination-Related Bamboo Slips from the Jianshui Jinguan Han Slips (Part III)]. In Jianbo yanjiu 2015 qiudong juan 簡帛研究·2015秋冬卷 [Bamboo and Silk Studies, Autumn-Winter 2015]. Edited by Zhenhong Yang 楊振紅 and Wenling Wu 鄔文玲. Guilin: Guangxi Shifan Daxue Chubanshe 廣西師範大學出版社, pp. 129–43. [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq, Eva. 2009. Sleep and Dreams in the Rāma-Kathās. In The Indian Night: Sleep and Dreams in Indian Culture. Edited by Claudine Bautze-Picron. New Delhi: Rupa & Co., pp. 303–28. [Google Scholar]

- Deleanu, Florin. 1997. A Preliminary Study on An Shigao’s 安世高 Translation of the Yogācārabhūmi 道地經. Journal of the Department of Liberal Arts, Kansai Medical University 17: 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Demiéville, Paul. 1954. La Yogācārabhūmi de Saṅgharakṣa. Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient 44: 339–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Guangchang 方廣錩. 2004. Dao’an pingzhuan 道安評傳 [A Critical Biography of Dao’an]. Beijing: Kunlun Chubanshe 昆崙出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, Donald J. 2009. Early Chinese Medical Literature: The Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts. London and New York: Routledge. First published 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashiya, Tomojirō 林屋友次郎. 1945. Ieki Keirui no Kenkyū 異譯經類の研究 [A Study of Differently Translated Scriptures]. Tokyo: Tōyō Bunko 東洋文庫. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Ruxuan 黃儒宣. 2013. Rishu tuxiang yanjiu 《日書》圖像研究 [A Study of the Iconography of the Daybook]. Shanghai: Zhongxi Shuju 中西書局. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Ruxuan 黃儒宣. 2017. Mawangdui boshu ‘Shangshuo’ zonglun 馬王堆帛書《上朔》綜論 [A Comprehensive Study of the “Shangshuo” Text from the Mawangdui Silk Manuscripts]. Wenshi 文史 [Literature and History] 2: 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology湖北省文物考古研究所, and Suizhou Archaeological Team隨州市考古隊, eds. 2006. Suizhou Kongjiapo Hanmu jiandu 隨州孔家坡漢墓簡牘 [Bamboo Slips from the Han-Dynasty Tomb at Kongjiapo]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Jamison, Stephanie W., and Joel P. Brereton. 2014. The Rigveda: The Earliest Religious Poetry of India. 3 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Xianlin 季羨林. 2008. Zhong-Yin wenhua jiaoliu shi 中印文化交流史 [History of Sino-Indian Cultural Exchange]. Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe 中国社会科学出版社. First published 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Shoucheng 姜守誠. 2014. Handai ‘xueji’ guannian dui daojiao zeri shu zhi yingxiang 漢代“血忌”觀念對道教擇日術之影響 [The Influence of the Han Dynasty “Blood Taboo” Concept on Daoist Date-Selection Practices]. Zongjiaoxue yanjiu 宗教學研究 [Religious Studies] 1: 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, Kashi Lal, ed. 2020. Viṣṇu Purāṇa: Sanskrit Text and English Translation According to H.H. Wilson. Delhi: Parimal Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Karashima, Seishi 辛嶋靜志. 2006. Underlying Languages of Early Chinese Translations of Buddhist Scriptures. In Studies in Chinese Language and Culture: Festschrift in Honour of Christoph Harbsmeier on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday. Edited by Christoph Anderl and Halvor Eifring. Oslo: Hermes Academic Publishing, pp. 355–66. [Google Scholar]

- Karashima, Seishi 辛嶋靜志. 2011. Liyong ‘fanban’ yanjiu Zhonggu Hanyu yanbian: Yi Daoxing bore jing ‘yiyi’ yu Jiuse lu jing wei li 利用“翻版”研究中古漢語演變:以《道行般若經》“異譯”與《九色鹿經》爲例 [Using “Counterparts” to Study the Evolution of Medieval Chinese: A Case Study of the ‘Different Translations’ of the Daoxing bore jing and the Jiuse lu jing]. Zhongzheng daxue Zhongwen xueshu nian kan 中正大學中文學術年刊 [National Chung Cheng University Journal of Chinese Studies] 18: 165–88. [Google Scholar]

- Link, Arthur E. 1957. Shyh Daw-An’s Preface to Sangharaksa’s Yogacarabhumi-Sutra and the Problem of Buddho-Taoist Terminology in Early Chinese Buddhism. Journal of the American Oriental Society 77: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Jingyao 劉婧瑤. 2016. Huangdi Hama jing de wenxian yanjiu 《黃帝蝦蟆經》的文獻研究 [A Textual Study of the Huangdi hama jing]. Master’s thesis, Changchun Zhongyiyao Daxue 長春中醫藥大學, Changchun, China. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Lexian 劉樂賢. 1994. Shuihudi Qin jian rishu yanjiu 睡虎地秦簡日書研究 [A Study of the Daybook from the Qin Slips of Shuihudi]. Beijing: Wenjin Chubanshe 文津出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Xinfang 劉信芳. 1993. ‘Rishu’ Sifang Siwei yu Wuxing Qianshuo 《日書》四方四維與五行淺說 [A Brief Discussion on the Four Directions, Four Dimensions, and the Five Elements in “Rishu”]. Kaogu yu wenwu 考古與文物 [Archaeology and Cultural Relics] 2: 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Loukota, Diego. 2020. La India filosófica explicada en la China de los Han posteriores: Encuentros y desencuentros en el primer texto budista compuesto en la China. In La tradición filosófica china en un mundo cosmopolita y multicultural: Perspectivas y análisis. Edited by Gabriel Terol and Filippo Costantini. San José: Costa Rica, pp. 207–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, Naiwen 梅迺文. 1996. Zhu Fahu de fanyi chutan 竺法護的翻譯初探 [A Preliminary Study on the Translations of Dharmarakṣa]. Zhonghua Foxue xuebao 中華佛學學報 [Chinese Buddhist Journal] 9: 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Meulenbeld, Gerrit Jan. 1999. A History of Indian Medical Literature. Groningen: Egbert Forsten Publishing, vol. 1A. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyaya, Sujitkumar, ed. 1954. The Śārdūlakarṇāvadāna. Santiniketan: Viśvabharati. [Google Scholar]

- Nattier, Jan. 2008. A Guide to the Earliest Chinese Buddhist Translations: Texts from the Eastern Han 東漢 and Three Kingdoms 三國 Periods. Tokyo 東京: The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology, Soka University. [Google Scholar]

- Nattier, Jan. 2010. Who Produced the Da mingdu jing 大明度經 (T225)? A Reassessment of the Evidence. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 33: 295–338. [Google Scholar]

- Needham, Joseph. 2000. Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 6: Biology and Biological Technology, Part 6: Medicine. With the Collaboration of Lu Gwei-djen. Edited and with an Introduction by Nathan Sivin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olivelle, Patrick, trans. 2005. Manu’s Code of Law: A Critical Edition and Translation of the Mānava-Dharmaśāstra. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pregadio, Fabrizio. 2005. Great Clarity: Daoism and Alchemy in Early Medieval China. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Xigui 裘錫圭, ed. 2014. Changsha Mawangdui Han mu jian bo jicheng 長沙馬王堆漢墓簡帛集成 [A Collection of Bamboo and Silk Manuscripts from the Han Tombs at Mawangdui, Changsha]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Radich, Michael. 2019. Zhu Fahu shifou xiuding guo T474? 竺法護是否修訂過T474?[Did Dharmarakṣa Revise T474?]. Foguang xuebao 佛光學報 [Fo Guang Journal] 2: 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Jiyu 任繼愈, and Zhaopeng Zhong 鐘肇鵬, eds. 1995. Daozang tiyao 道藏提要 [A Conspectus of the Daoist Canon]. Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe 中國社會科學出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Rocher, Ludo. 1986. The Purāṇas. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Salguero, C. Pierce. 2009. The Buddhist Medicine King in Literary Context: Reconsidering an Early Medieval Example of Indian Influence on Chinese Medicine and Surgery. History of Religions 48: 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salguero, C. Pierce. 2014. Translating Buddhist Medicine in Medieval China. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Priya Vrat, ed. 1992. History of Medicine in India. New Delhi: Indian National Commission for History of Science. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Priya Vrat, ed. and trans. 1994. Caraka Saṃhitā. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Orientalia. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Priya Vrat, ed. and trans. 1999. Suśruta-saṃhitā. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Visvabharati. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Sudarshan Kumar, trans. 2008. Vāyu Purāṇa. Delhi: Parimal Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Zhanyu 孫占宇. 2013. Gansu Qin-Han jiandu jishi Tianshui fangmatan Qin jian jishi 甘肅秦漢簡牘集釋 天水放馬灘秦簡集釋 [Collected Explanations of Qin and Han Bamboo Slips in Gansu: Collected Explanations of the Qin Slips from Fangmatan, Tianshui]. Edited by Defang Zhang 張德芳. Lanzhou: Gansu Wenhua Chubanshe 甘肅文化出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Zhanyu 孫占宇, and Jialiang Lu 魯家亮. 2017. Fangmatan Qin jian ji Yuelu Qin jian “Mengshu” yanjiu 放馬灘秦簡及岳麓秦簡《夢書》研究 [A Study of the Fangmatan Qin Slips and the Yuelu Qin Slips “Mengshu”]. Wuhan: Wuhan Daxue Chubanshe 武漢大學出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Yongtong 湯用彤. 2011. Han Wei Liang Jin Nanbeichao Fojiao shi (Zengding ben) 漢魏兩晉南北朝佛教史(增訂本)[The History of Buddhism in the Han, Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties (Revised Edition)]. Beijing: Beijing Daxue Chubanshe 北京大學出版社. First published 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Ui, Hakuju 宇井伯壽. 1956. Shakudōan Kenkyū 釋道安研究 [A Study of Dao’an]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten 岩波書店. [Google Scholar]

- Ui, Hakuju 宇井伯壽. 1971. Yakukyōshi Kenkyū 訳経史研究 [A Study of the History of Buddhist Translations]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten 岩波書店. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Qiupeng 伍秋鵬. 2021. Handai huaxiangshi shang de Bian Que tuxiang tanxi 漢代畫像石上的扁鵲圖像探析 [An Analysis of Bian Que Images on Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs]. Zhongguo meishu yanjiu 中國美術研究 [Chinese Art Research] 3: 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Xiaoqiang 吳小强. 2000. Qin jian rishu jishi 秦簡日書集釋 [Collected Explanations of the Daybook from Qin Bamboo Slips]. Changsha: Yuelu shushe 岳麓書社. [Google Scholar]

- Yamabe, Nobuyoshi. 2013. Parallel Passages between the Manobhūmi and the Yogācārabhūmi of Saṃgharakṣa. In The Foundation for Yoga Practitioners: The Buddhist Yogācārabhūmi Treatise and Its Adaptation in India, East Asia, and Tibet. Edited by Ulrich Timme Kragh. Harvard Oriental Series 75. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 596–737. [Google Scholar]

- Zacchetti, Stefano. 2002. An Early Chinese Translation Corresponding to Chapter 6 of the Peṭakopadesa: An Shigao’s Yin chi ru jing T 603 and Its Indian Original: A Preliminary Survey. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 65: 74–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacchetti, Stefano. 2004. Teaching Buddhism in Han China: A Study of the Ahan Koujie shi’er yinyuan jing T 1508 Attributed to An Shigao. Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University for the Academic Year 2003 7: 197–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zacchetti, Stefano. 2010. Defining An Shigao’s 安世高 Translation Corpus: The State of the Art in Relevant Research. Xiyu lishi yuyan yanjiu jikan 西域歷史語言研究集刊 [Historical and Philological Studies of China’s Western Regions] 3: 249–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Defang 張德芳, and Hua Han 韓華. 2016. Juyan xin jian jishi 6 居延新簡集釋 6 [Collected Explanations of the New Juyan Bamboo Slips, Volume 6]. Lanzhou: Gansu Wenhua Chubanshe 甘肅文化出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Guoyan 張國艶. 2018. Jiandu rishu wenxian yuyan yanjiu 簡牘日書文獻語言研究 [A Study on the Language of Daybook Documents in Bamboo and Wooden Slips]. Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe 中國社會科學出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Gang 鄭剛. 1993. Lun Shuihudi Qin jian “Rishu” de jiegou tezheng 論睡虎地秦簡《日書》的結構特徵 [On the Structural Features of the “Daybook” from the Qin Bamboo Slips of Shuihudi]. Zhongshan daxue xuebao (shehui kexue ban) 中山大學學報(社會科學版) [Journal of Sun Yat-sen University (Social Science Edition)], 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Liqun 周利群. 2020. Huer piyu jing wenben yu yanjiu 虎耳譬喻經文本與研究 [The Text and Study of the Hu’er Piyu Jing]. Shanghai: Shanghai Jiaotong Daxue Chubanshe 上海交通大學出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Xianmin 朱現民. 2011. Guanyu zhenjiu guji Huangdi hama jing de tankao 關于針灸古籍《黃帝蝦蟆經》的探考 [An Exploration of the Ancient Acupuncture Text Huangdi hama jing]. Liaoning zhongyi zazhi 遼寧中醫雜志 [Liaoning Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine] 1: 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher, Erik. 1991. A New Look at the Earliest Chinese Buddhist Texts. In From Benares to Beijing: Essays on Buddhism and Chinese Religion in Honor of Prof. Jan Yün-hua. Edited by Marc Kalinowski. Oakville: Mosaic, pp. 277–304. [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher, Erik. 2007. The Buddhist Conquest of China. Leiden: E. J. Brill. First published 1972. [Google Scholar]

| T607 | T606 | T374 | Caraka-saṃhitā | Suśruta-saṃhitā | Aṣṭāṅga Hṛdaya | Purāṇa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [A.1] Dreams of a dying patient | 232a22–b24 | 183c4–184a12 | 481b29–c9 | 5.5 | 1.29 | 2.6 | AP.228 VP.19 SP.4.1 |

| [A.2] Omens on the messenger sent to seek a physician | 232b24–c2 | 184a13–26 | 481c9–13 | 5.12 | 1.29 | 2.6 | AP.294 |

| [A.3] Inauspicious dates, constellations, and times for seeking medical help | 232c2–12 | 184a27–b13 | 481c13–24 | 5.12 | 1.29 | 2.6 | AP.294 |

| [A.4] Omens seen and heard by the physician in the home of a dying patient | 232c12–17 | 184b14–18 | 481c24–482a9 | 5.12 | 1.29 | 2.5–6 | |

| [A.5] Physical symptoms of an incurable patient | 232c17–233a10 | 184b18–c26 | 482a9–24 | 5.1–4, 7–12 | 1. 28, 31–32 | 2.5 | VP.19 SP.4.1 |

| [B] The most skilled physicians | 233a10–11 | 184c26–185b8 | / | ||||

| [C] The benevolent lies of the physician | 233a11–15 | 185b9–16 | 482a24–28 | 5.12 | 2.5 |

| T607 Daodi jing | T606 Xiuxing daodi jing | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 從若干經得明堅,不老不死甘露 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 231, b23) | 從若干經採明要,立不老死甘露言 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 182, c22–23) |

| 2 | 如是在一貫珠,一時俱行,五陰更如是。 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 232, a10–11) | 如是五陰,如一貫珠,一時俱行 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 183, b19–20) |

| 3 | 自手摩抆鬚髮 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 232, b27) | 而數以手摩抆鬚髮 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 184, a20–21) |

| 4 | 復見小兒俱相坌土;復胆裸,相挽頭髮,破瓶盆瓦甌 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 232, c15–16) | 或見小兒,以土相坌,而復裸立,相挽頭髮,破甖瓶盆 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 184, b17–18) |

| 5 | 譬如人死時有死相,為口不知味,耳中不聞聲 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 233, a6–7) | 人臨死時,所現變怪:口不知味,耳不聞音 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 184, c17–18) |

| 6 | 中止者或住一日,或住七日止 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 233, c7–8) | 在中止者,或住一日,極久七日 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 186, b9–10) |

| 7 | 大腸、小腸、肝、肺、心、脾、腎,亦餘藏,令斷截 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 233, b5–6) | 大小之腸、肝肺心脾,并餘諸藏,皆令斷絕 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 185, c12–13) |

| 8 | 二十五七日,生七千脈,尚未具成 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 234, b17) | 二十五七日,生七千脈,尚未具成 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 187, b14–15) |

| 9 | 二十六七日,諸脈悉徹,具足成就,如蓮花根孔 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 234, b17–18) | 二十六七日,諸脈悉徹,具足成就,如蓮華根孔 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 187, b15–16) |

| 10 | 三十六七日,爪甲生 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 234, b24–25) | 三十六七日,爪甲成 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 187, b22) |

| 11 | 三十七七日,母腹中若干風起 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 234, b25) | 三十七七日,其母腹中,若干風起 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 187, b22–23) |

| 12 | 三十八七日,為九月不滿四日,骨節皆具足。兒生宿行有二分:一分從父,一分從母 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 234, c4–6) | 是為三十八七日。九月不滿四日,其兒身體、骨節,則成為人……其小兒體而有二分:一分從父,一分從母。 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 187, c6–13) |

| 13 | 如是并四百四病在身中。譬如木中出火還燒木 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 235, a14–16) | 凡合計之,四百四病,在人身中。如木生火,還自燒然 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 188, c8–9) |

| 14 | 是身為譬如餓鬼,常求食飲 (CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 236, b12–13) | 是身如餓鬼,常求飲食 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 219, b14–15) |

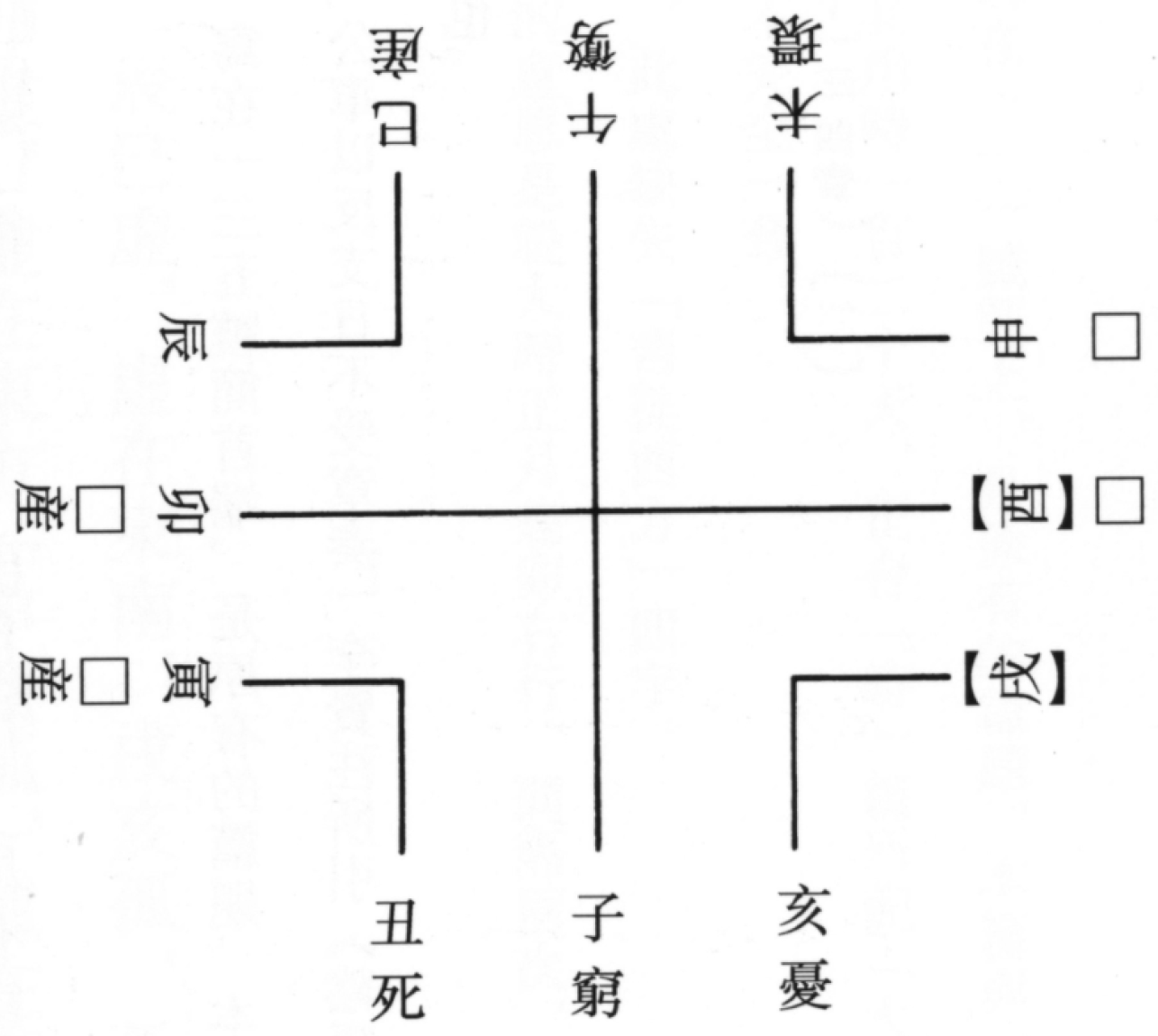

| T607 | 亦如是諱日來呼:[i] 若四、若六、若九、若十二、若十四來至到,復觸忌諱日,人所不喜醫,[ii] 復何血忌、上相 1、四激、反支來喚?是亦不必日時、漏刻、星宿、須臾,……(CBETA, T15, no. 607, p. 232, c2–5) … or seeking the physician on inauspicious days, such as the fourth, sixth, ninth, twelfth, or fourteenth days (of each month), or on other unfavorable days when it’s not advisable to consult a physician, such as on dates of Xueji, Shangxiang,* Siji, and Fanzhi. However, there are situations where one doesn’t necessarily have to adhere to specific dates, times, constellations, or fortune-telling, … |

| T606 | [i] 又其日惡,若四日、六日、十二日、十四日,以此日來者皆為不祥,醫即不喜,[ii] 以觝星宿,失於良時,神仙先聖所禁之日。醫心念言:“雖值此怪星宿吉凶,或可治療。” (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 184, a29–b3) If the day is inauspicious, such as the fourth, sixth, twelfth, or fourteenth days (of a month), seeking medical attention on these days is considered unlucky. The physician won’t be pleased because it conflicts with the celestial alignments and is not a favorable time. These are days that the sages (ṛṣi) have prohibited. However, the physician may think, “Even though it’s an inauspicious time astrologically, the patient might still be treatable.” |

| T374 | [i] 復作是念:“使雖不吉,當復占日,為可治不?” 若四日、六日、八日、十二日、十四日,如是日者,病亦難治。[ii] 復作是念:“日雖不吉,當復占星,為可治不?” 若是火星、金星、昴星、閻羅王星、濕星、滿星,如是星時,病亦難治。[iii] 復作是念:“星雖不吉,復當觀時。” 若是秋時、冬時,及日入時、夜半時、月入時,當知是病亦難可治。(CBETA, T12, no. 374, p. 481, c13–20) He further reflects, saying: “Even if the messenger is inauspicious, should I observe the day to determine if treatment is possible?” If it is the fourth, sixth, eighth, twelfth, or fourteenth day (of a month), then on such days, the illness is also difficult to treat. He further reflects, saying: “Even if the day is inauspicious, should I observe the stars to determine if treatment is possible?” If it is under the influence of Mars, Venus, the Pleiades, Yama’s star, the “Moist Star”, or the “Full Star”, then during such times, the illness is also difficult to treat. He further reflects, saying: “Even if the stars are inauspicious, should I observe the timing?” If it is during autumn, winter, sunset, midnight, or moonset, it should be understood that the illness is also difficult to treat. |

| Ca. | 5.12.68 [iii] …-asandhyāsv agraheṣu ca | [ii] adāruṇeṣu nakṣatreṣv anugreṣu dhruveṣu ca || 5.12.69 [i] vinā caturthīṃ navamīṃ vinā riktāṃ caturdaśīm | [iii] madhyāhnamardharātraṃ ca … (The physician should regard the messenger of the following description as auspicious, i.e., … arriving at times other than) those marked by the two twilights, inauspicious conjunction of planets, constellations which are unstable and of a fierce or baleful aspect, the “void” days of the fortnight comprising the fourth, ninth and fourteenth days, the mid-day and the midnight… 2 |

| Su. | 1.29.17 [iii] madhyāhne cārdharātre vā sandhyayoḥ kṛttikāsu ca | [ii] ārdrāśleṣāmaghāmūlapūrvāsu bharaṇīṣu ca || [i] caturthyāṃ vā navamyāṃ vā ṣaṣṭhyāṃ sandhidineṣu ca | (A messenger, seeking the interview of a physician …) at noon or at midnight, at morning or at evening, or during the happening of any abnormal physical phenomenon, or at an hour under the influence of any of the following asterisms (lunar mansions), viz. the Ārdra, the Aśleṣā, the Maghā, the Mulā, the two Pūrvas, and the Bharaṇī, or on the day of the fourth, ninth, or the sixth phase of the moon (whether on the wane or on the increase), as well as on the last days of months and fortnights, should be considered as a messenger of evil augury. 3 |

| AH | 2.6.11–12 [iii] … tathārdharātre madhyāhne saṃdhyayoḥ parvavāsare || [i] ṣaṣṭhīcaturthīnavamī- [ii]rāhuketūdayādiṣu | [ii] bharaṇīkṛttikāśleṣāpūrvārdrāpaitryanairṛte || So also he, who approaches (the physician) at midnight, midday, sunrise and sunset, on a crucial (bad) day; on the sixth, fourth, and ninth days (of the two fortnights), on days of rise of rāhu and ketu, on days of stars like Bharaṇi, Kṛttikā, Aśleṣā, Pūrvā, Ārdrā, Paitra (Maghā) and Nairṛta (Mūla). |

| Shuo 朔 |  EPT52 1: 194 |  EPT43 2: 62 |  EPT43: 99 |

| Xiang 相 |  EPT56: 77B |  EPT59: 524A |  EPT57: 64 |

| T606 (CBETA, T15, no. 606, p. 184, c26–185, a8) | English Translation |

|---|---|

| 古昔良醫,造結經文,名曰: | In ancient times, there were many skilled physicians who wrote scriptures, and their names were: |

| 於彼、除恐、 | “In There (=Ātreya),” “Remove Fear (=? Abhayadatta),” |

| 長耳、灰掌、 | “Growth-ears (=Jatūkarṇa),” “Ashen Palms (=Kṣārapaṇi),” |

| 養言、長育、 | “Cultivate Language,” “Nurture (=? Janaka),” |

| 急教、多髯、 | “Eagerly Educate,” “Many Beards,” |

| 天又 1、長蓋 2、 | “Divine Blessing,” “Long Umbrella,” |

| 大首、退轉、 | “Big Skull,” “Retreat,” |

| 燋悴 3、大白 4、 | “Emaciated,” “Venus (=? Uśanas),” |

| 最尊、路面、 | “Most Revered (=? Vasiṣṭha),” “Road Surface,” |

| 調牛、岐伯、 | “Taming Bull (=Gautama 5),” “Qi Bo,” |

| 醫徊、扁鵲, | “Physician Wandering (=Caraka),” and “Bian Que.” |

| 如是等輩, 悉療身病。 於是頌曰: | All of these individuals specialized in treating physical ailments (kāyacikitsitā). A verse praises them in this way: |

| 於彼之等類, 尊法梵志仙, 正救所有果, 及餘王良醫。 此為主成敗 6, 博知能度厄, 愍以經救命, 猶如梵造法。 | Brahmin sages revered in the law, like “In There,” and other royal physicians can rescue all from the fruits of karma. They are well-learned, decisive in success or failure, able to assist in overcoming calamities, compassionate in their hearts, saving lives according to the scriptures, just as crafted by Brahma himself. |

| Śārdūlakarṇāvadāna 1 | kiṃ pūrvaḥ? āha: Ātreyaḥ. |

|---|---|

| T1301 Shetoujian taizi ershiba xiu jing, translated by Dharmarakṣa 2 | 時弗袈裟聞說如是,則逆問曰:“仁何種姓?”答曰:“於是。” 3 |

| T1300 Modengjia jing, anonymous 4 | 蓮華實言:“汝姓何等?”曰:“姓三無”。 5 |

| English Translation | Puṣkarasārin, upon hearing him speak this way, counter-asked, “To which family do you belong?” The reply came, “I am an Ātreya (offspring of Atri).” |

| Śārdūlakarṇāvadāna | pūrvabhādrapadānakṣatraṃ dvitāraṃ padakasaṃsthānaṃ triṃśanmuhūrtayogaṃ māṃsarudhirâhāramahirbudhnyadaivataṃ jātūkarṇyaṃ gotreṇa | |

| T1301, by Dharmarakṣa | 前賢迹宿者,有二要星,相遠對立,行三十須臾,而侍從矣,餅肉為食,主人是天,姓生耳。(CBETA, T21, no. 1301, p. 415, c26–27) |

| T1300, anonymous | 室有二星,形如人步,一日一夜,與月共行,血肉祠祀,其宿屬在富單那神,姓闍罽那。(CBETA, T21, no. 1300, p. 405, a20–22) |

| Pūrvabhadrapāda, two stars, shaped like footprints, correspond to thirty muhūrtas. Meat and blood are its food, Ahirbudhnya is the ruling deity, and it belongs to the Jātūkarṇya gotra |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, L. Translating Medicine Across Cultures: The Divergent Strategies of An Shigao and Dharmarakṣa in Introducing Indian Medical Concepts to China. Religions 2025, 16, 844. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070844

Lu L. Translating Medicine Across Cultures: The Divergent Strategies of An Shigao and Dharmarakṣa in Introducing Indian Medical Concepts to China. Religions. 2025; 16(7):844. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070844

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Lu. 2025. "Translating Medicine Across Cultures: The Divergent Strategies of An Shigao and Dharmarakṣa in Introducing Indian Medical Concepts to China" Religions 16, no. 7: 844. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070844

APA StyleLu, L. (2025). Translating Medicine Across Cultures: The Divergent Strategies of An Shigao and Dharmarakṣa in Introducing Indian Medical Concepts to China. Religions, 16(7), 844. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070844