Abstract

Proclamation of the gospel is a perennial practice of congregational leadership demanding responsiveness to issues, trends, and events impacting congregations, their local and regional communities, and the challenges of the world. How do congregational leaders equip themselves for the important and ever-changing task of preaching? Lifelong learning, the fastest-growing and least-resourced aspect of theological education in North America, provides this opportunity. Through a 2024 survey, this quantitative study provides insight into the lifelong learning needs of Methodist preachers, including differences based on gender and race/ethnicity. Time for additional learning is the major perceived obstacle for preachers desiring to improve their craft. Thus, lifelong learning programs must make the case for how the required time and energy will benefit the preacher participating in such programs. Specifically, the activities of reviewing recordings of sermons (both one’s own and those of other preachers), receiving constructive feedback on sermons, and realizing the collaborative potential of preaching must be structured in ways that prove the value of these investments for preachers. This data on the lifelong learning needs of Methodist preachers has implications on multiple levels: conceptual, institutional, congregational, and personal.

1. Introduction

Proclamation of the gospel is a perennial practice of congregational leadership. Yet, the effective practice of preaching is also constantly responsive to issues, trends, and events impacting congregations, their local and regional communities, and the challenges of the world. Homiletical agility was essential during the COVID-19 pandemic (Alcántara 2020), for example, and that need has not abated. According to a 2023 survey, 80 percent of Protestant churchgoers in the United States agreed that “A pastor must address current issues to be doing their job,” and 96 percent of Methodists agreed with this statement (Lifeway Research 2023). The act of preaching provides the most prominent way of addressing current issues. Even in traditions in which engagement with social issues is not a primary concern for preaching, innovations in homiletical methods are highly valued. New media, such as podcasts, social media, and streaming services, are quickly leveraged to proclaim the eternal word of God. Whether through new content, new methods of communication, or both, preachers are constantly challenged to hone their craft.

How do congregational leaders equip themselves for the important and ever-changing task of preaching? A 2022–2023 study by the Association of Theological Schools (ATS) shows the importance of preaching for congregational leadership. When asked, “What skills/knowledge/competencies do you rely on most heavily to do your work?,” alumni/ae of ATS-member schools working in congregational contexts ranked preaching first by a wide margin (Gin et al. 2025, p. 158). Yet, the study authors observed a misalignment between graduate theological education and the competencies congregational leaders most rely upon in their work (Gin et al. 2025, p. 149). They found that only 5 percent of full-time faculty specialize in homiletics, and preaching ranked seventh on the list of course offerings, far behind Bible, theology, formation, church history, and other areas of study (Gin et al. 2025, p. 164). The study authors suggested, “Lifelong learning is one way that theological schools are addressing gaps between curricula and competencies” (Gin et al. 2025, p. 173). A degree program lasts only a few years; continuing education and formation lasts a lifetime.

Ministry practitioners and graduate school administrators express a growing awareness of the need for lifelong learning. Many leaders and researchers identify lifelong learning as crucial to the future of ministry and theological education (Blier 2023; Blier and Gin 2022; Conde-Frazier 2021, pp. 92–97; Gin and Deasy 2024, 43–45 min.; González 2015, pp. 138–39; Smith 2023, p. 179). It is especially critical for ministry practices, such as preaching: “The call to preach is … the call to a lifelong journey of ongoing personal and professional development.” (Tucker 2017, p. 201). Preachers are attuned to this need, as evidenced by a clear demand for ongoing educational opportunities. Non-degree (certificate and lifelong learning) enrollment in ATS-member schools grew by 24% between 2023 and 2024—the only significant area of growth and “the most promising enrollment trend” within theological education (Meinzer 2024).

Lifelong learning is the fastest-growing and least-resourced aspect of theological education in North America. Programs of lifelong learning for ministry are under-resourced (Blier 2022). Recognizing lifelong learning as one of five primary sectors providing care for clergy, researchers from a Duke University study observed that “there is very little dialogue occurring between the academic community and other providers,” creating an untapped opportunity for collaboration and support (Austin and Comeau 2022, p. 60). The Duke study determined that lifelong learning programs need “research-informed tangible guidelines and practical frameworks” to flourish (Austin and Comeau 2022, p. 72). The present study provides quantitative data to inform the development of such guidelines and frameworks.

This article contributes to the development of lifelong learning for preachers by presenting the results of a survey of preachers. This quantitative study was conducted in the spring of 2024 within the Greater New Jersey and Eastern Pennsylvania Annual Conferences of The United Methodist Church. This survey was designed to assess preachers’ interest in skill development and learning opportunities, collaboration with listeners, and obstacles to improved preaching. This data on the lifelong learning needs of Methodist preachers has implications on multiple levels: conceptual, institutional, congregational, and personal.

2. Materials and Methods

The United Methodist Church (UMC) entrusts the task of preaching to laity and clergy alike, resulting in an elaborate list of official categories. The UMC ordains both permanent (vocational) deacons and elders (presbyters). Deacons and elders are commissioned for a trial period of two or more years before ordination. Licensed local pastors function as presbyters in specific locations on a year-to-year basis. All three categories of clergy are appointed by a bishop to their specific ministry settings. Lay preachers (including certified lay preachers and supply pastors) are “assigned” by the bishop rather than “appointed.” Formal education in the practice of preaching varies widely among and within all categories of United Methodist preachers.

Survey data were collected using an online questionnaire distributed to United Methodist preachers in the Greater New Jersey and Eastern Pennsylvania Annual Conferences in the spring of 2024. The questionnaire was distributed via direct email invitations to ordained, commissioned, or licensed pasters under bishop appointment, lay preachers assigned to regional congregations, and ordained or commissioned deacons. Additionally, as a regular reminder, a link to the questionnaire was included in a weekly email newsletter shared with all conference members. The survey remained open during March and April 2024.

Of the 203 total responses submitted, 38 individuals either failed to answer any questions or answered only the background questions presented on the first page of the survey. These responses were omitted from the sample prior to analysis. Thus, a total of n = 165 usable responses were collected. The response rate can be calculated in two ways, comparing the sample size (n) to the target population (N). The total number of clergy members (N = 1453) in the conferences studied includes retired clergy and those not under appointment but does not include data about lay preachers assigned to congregations, resulting in a response rate of 11.4%. This N differs from the number of invitational emails (N = 712) sent to active preachers, lay and clergy, resulting in a response rate of 23.2%. While the smaller N is more accurate for calculating the response rate among active preachers, no demographic information is available for this subset. Demographic information is only available for clergy (N = 1453), who comprise 80.6% of the sample. Because respondents were self-selected (non-random), and because some sample characteristics were found to differ significantly from the parent population of United Methodist preachers in the conferences studied, statistically significant findings should be interpreted with caution.

For all Tables in this article, valid counts and percentages are reported, and characteristic percentages do not always total 100 percent due to rounding errors. For gender identity, the category “Declined/Unknown/Undefined” does not include true missing values. Bar charts were visually examined to assess the assumption of similarly shaped distributions across groups; while no substantial distributional differences were observed, both medians and means were provided.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Demographics

The sample closely reflected conference demographics (see Table 1), with most respondents identifying as male and White. Although the distribution of respondents across racial/ethnic categories was not found to differ significantly from the population, female preachers were overrepresented among study participants.1

Table 1.

Sample and conference demographics.

All but four respondents reported that they are not conference staff (see Table 2) and, when asked to indicate their role as a conference member, over three-quarters reported that they are either an elder appointed to a local congregation or a licensed local pastor. Additionally, most participants have eight or more years of preaching experience, are the primary preacher in their ministry setting, and preach primarily in person. Only 2.4% of respondents, compared to an estimated 4% of active preachers in the two conferences, preach regularly in a language other than English.

Table 2.

Respondent background characteristics.

3.2. Study Findings

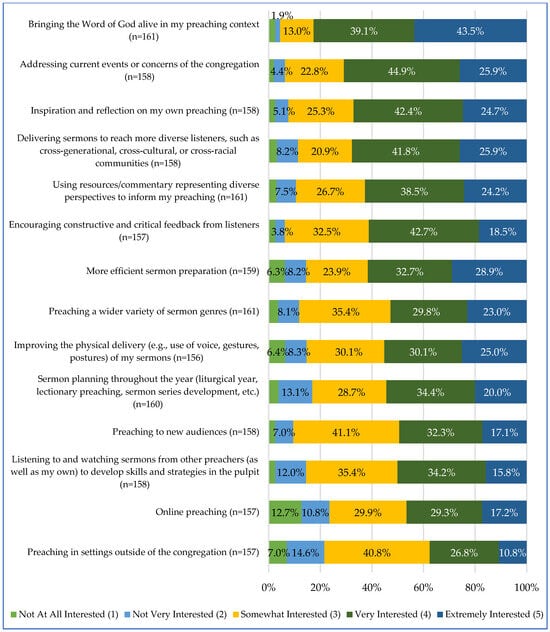

As shown in Figure 1, among the preaching skills listed in the questionnaire, respondents averaged the greatest interest in improving their ability to bring the Word of God alive in their preaching context (M = 4.19). Likewise, most indicated that they are “very” or “extremely interested” in improving their ability to the following: address current events and congregational concerns (70.8%); feel inspired about and reflect upon their own preaching (67.1%); deliver sermons that reach more diverse audiences (67.7%); utilize resources representing diverse perspectives to inform their preaching (62.7%); encourage listener feedback (61.2%); and prepare sermons efficiently (61.6%). In contrast, participants averaged the least interest in improving their ability to preach in settings outside of their congregation (M = 3.20). About half of respondents reported that they are only “somewhat” or less interested in improving their preaching skills in the remaining areas listed, such as preaching a wider variety of sermon genres, online preaching, and sermon planning and delivery. Curiously, only 50% reported they are very or extremely interested in “Listening to and watching sermons … to develop skills and strategies,” contrasting with 67% who expressed the same level of interest in “Inspiration and reflection on my own preaching.”2

Figure 1.

Interest in preaching skill development.

Results from a series of Mann–Whitney U tests (see Table 3) revealed one significant gender difference and a multitude of significant racial/ethnic differences on items measuring interest in preaching skill development. Specifically, female preachers expressed significantly less interest in improving their ability to preach to new audiences compared to males (Z = 2.08, p < 0.05), while White preachers expressed significantly less interest in developing or improving nearly all skills listed in this portion of the questionnaire compared to preachers of color (p < 0.05, respectively).

Table 3.

Significant Mann–Whitney U test results for demographic comparisons on interest in preaching skill development measures.

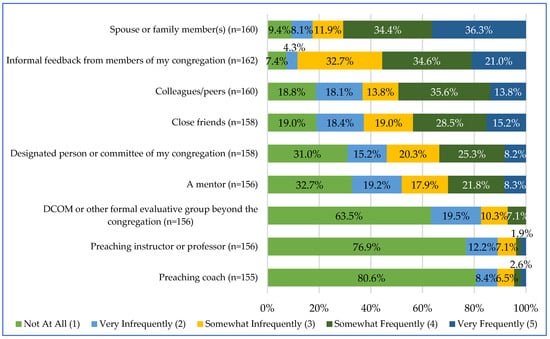

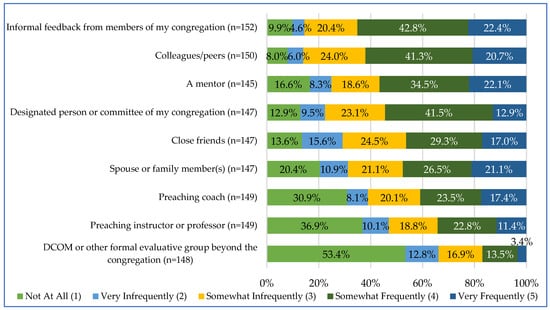

Regarding listener feedback (see Figure 2), most participants reported that they “somewhat” or “very frequently” solicit feedback on their preaching from their spouse or family members (70.7%) and members of their congregation (55.6%). Additionally, nearly half reported soliciting feedback at least “somewhat” frequently from colleagues or peers (49.5%) and close friends (43.7%), and about a third indicated receiving frequent feedback from a designated person or committee within their congregation (33.6%) and their mentor(s) (30.1%). On the other hand, as shown in Figure 3, respondents overwhelmingly reported that they seek feedback from formal evaluative groups (92.9%), preaching instructors (96.2%), and preaching coaches (95.5%) either infrequently or not at all.3

Figure 2.

Current frequency of preaching feedback.

Figure 3.

Desired frequency of preaching feedback.

As shown in Table 4, testing revealed that, compared to males, female preachers more frequently seek feedback from their colleagues and peers (Z = −2.53, p < 0.05), while preachers of color were found to solicit more frequent feedback from both mentors (Z = 2.25, p < 0.05) and formal evaluative groups (Z = 2.33, p < 0.05) compared to their White counterparts.

Table 4.

Significant Mann–Whitney U test results for demographic comparisons on current frequency of preaching feedback measures.

When asked to indicate the frequency with which they would like to receive feedback on their preaching from the same sources (see Figure 3), respondents provided the greatest share of “somewhat” or “very frequently” ratings for members of their congregation (65.2%) and the smallest share for formal evaluative groups outside of the congregation (16.9%) (see Figure 3, next page). Notably, compared to their current feedback ratings, participants averaged higher desired feedback ratings for all categories apart from their spouse and family members (current M = 3.80; desired M = 3.17). On average, the greatest disparities between current and desired feedback were observed for mentors (current M = 2.54; desired M = 3.37), preaching instructors (M = 1.40; desired M = 2.62), and preaching coaches (M = 1.37; desired M = 2.89).

As shown in Table 5, test results showed that, compared to males, female preachers desire more frequent feedback from both their spouse or family members (Z = 2.06, p < 0.05) and preaching instructors (Z = 2.01, p < 0.05). Additionally, results revealed that White preachers desire significantly less frequent feedback from mentors compared to preachers of color (Z = 2.23, p < 0.05).

Table 5.

Significant Mann–Whitney U test results for demographic comparisons on desired frequency of preaching feedback measures.

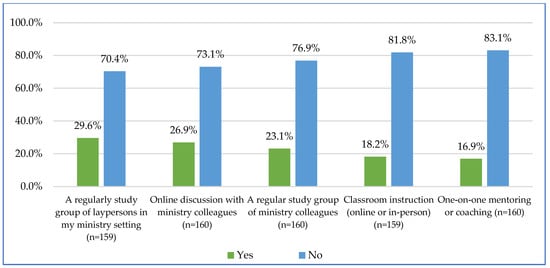

As shown in Figure 4, relatively few respondents reported employing collaborative methods in their preaching preparation, with 20–30% of preachers indicating that they hold a regular study group with laypersons and/or ministry colleagues and engage in online discussions with colleagues, and fewer reporting engagement in classroom instruction (18.2%) and one-on-one mentoring or coaching sessions (16.9%).

Figure 4.

Collaborative methods employed in preaching preparation.

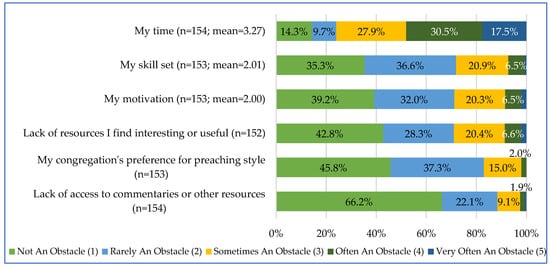

Participants overwhelmingly reported that most of the potential obstacles listed in the questionnaire pose little to no challenge to working toward improved preaching practices (see Figure 5). Specifically, while most indicated that their time “sometimes” or more often presents an obstacle to working toward improvements (76.0%), over two-thirds view their skillset, motivation, congregation’s preference for preaching style, and a lack of both interesting/useful resources and access to such materials as “rarely” if at all posing an obstacle to improved preaching practices.4

Figure 5.

Obstacles to improved preaching.

As shown in Table 6, only one significant racial/ethnic difference was observed among demographic comparisons on the obstacle items, with test results revealing that White preachers view their congregation’s preference for preaching style as less of an obstacle to working toward improvements compared to preachers of color (Z = 2.60, p < 0.01).

Table 6.

Significant Mann–Whitney U test results for demographic comparisons on obstacles to improved preaching measures.

4. Discussion

4.1. Results

The Methodist preachers participating in this survey are generally open to developing their preaching skills through both personal and collaborative means. They are responsive to feedback on their preaching practices from both listeners and colleagues and are interested in taking advantage of future learning opportunities.

Specifically, respondents are most interested in improving their preaching skills by bringing the word of God alive in their preaching context, addressing current events and congregational concerns in their sermons, and through self-reflection on their preaching style and content. Conversely, respondents are least interested in preaching to new audiences and in new settings, reflecting on others’ sermons (or their own) to improve their own preaching, and online sermon delivery.

It is disconcerting that half of the survey respondents seem reluctant to learn from their own sermons and those of others. The difference in interest in “Inspiration and reflection on my own preaching” (67%) contrasted with “Listening to and watching sermons … to develop skills and strategies” (50%) suggests that preachers may be inspired but tired, lacking the time and energy to develop the skills needed to improve their craft. When asked to rate the extent to which various factors pose obstacles to developing improved preaching practices, time constraints received the highest average rating, with few indicating that other factors such as their skill set, motivation, and available resources present challenges to such efforts.

Receiving constructive feedback is an important part of growing as a preacher. Preachers surveyed most frequently solicit feedback from close family and friends, congregation members, and colleagues, with far fewer reporting consultations with designated committees, mentors, and instructors or coaches. When asked the frequency with which they would like to receive more constructive feedback from various groups, most indicate that they would prefer “somewhat” or more frequent feedback from mentors and designated committees, as well as their colleagues and congregation members.

Collaboration among preachers and between preachers and listeners is also a significant avenue for growth in the art of preaching. Lifelong learning draws on life experiences and peer learning, and working together is the most direct way to activate this learning and to lighten the load. There is a case to be made for collaboration in the task of preaching (Hannan 2021). Notably, fewer than a third of respondents employ one or more collaborative methods in their preaching preparation, with the most common being study groups with laity and colleagues, and online discussions with peers.

Formal statistical testing revealed numerous significant or marginally significant differences based on respondent demographic characteristics. Regarding gender differences, female preachers express less interest in preaching to new audiences and greater interest in addressing current events or congregational concerns through sermons; more frequently solicit feedback from colleagues and mentors, and desire more frequent feedback from family members, peaching coaches, and instructors; express less interest in becoming a trained peer facilitator; and are more likely to view their skill set and a lack of access to resources as obstacles to improved preaching.

Regarding racial/ethnic differences, preachers of color express greater interest in improving their preaching skills across all areas; more frequently solicit feedback from mentors and formal evaluative groups, and similarly desire more frequent feedback from these sources; are more likely to view congregational preferences as an obstacle to improved preaching; and are less likely to view their motivation as a challenge. Notably, only two respondents preach primarily in languages other than English.

Lastly, with regard to differences based on years spent preaching, those with fewer years of experience are generally more interested in using diverse perspectives to inform their preaching; more frequently solicit feedback from a peaching coach, and desire more frequent feedback from nearly all sources; express greater interest in a hybrid certificate program offering; and are more likely to view their skill set and a lack of access to commentaries or resources as obstacles to improved preaching. Although most observed differences were found to be weak to moderate in size, these findings may nonetheless warrant further consideration when designing lifelong learning opportunities for preachers.

4.2. Interpretation

Lifelong learning is an important though undervalued part of a preacher’s professional development. Although lifelong learning is essential to ongoing development, the practice of ministry lacks a professional association to standardize continuing education or oversee licensing. Clergy have no equivalent to the American Association of Nurse Practitioners or the American Psychological Association or other national guilds. Ordination and licensing standards vary from church to church, denomination to denomination, as do expectations for continued learning and development. Nevertheless, preachers benefit tremendously when they pursue lifelong learning.

Amid the current state of rapid social change within the United States and Canada, graduate theological schools are increasingly expected to provide structured lifelong learning opportunities to hone ongoing, effective ministerial practice. ATS claims 270 graduate schools of theology as members in the United States and Canada. For the first time, in June 2020, ATS adopted an accrediting standard pertaining to lifelong learning: “The school demonstrates an understanding of learning and formation as lifetime pursuits by helping students develop motivations, skills, and practices for lifelong learning” (ATS 2020, §3.5). Furthermore, seminary graduates are requesting such opportunities. Recent data from ATS’s “Mapping the Workforce of ATS Grads” survey show lifelong learning as a significant area of growth in theological education (Gin 2024; Gin and Deasy 2024). A graduate degree program, no matter how robust, simply cannot offer a “complete” education for ministry practitioners.

For more than a century, the preparation of mainline Protestant clergy for careers in ministry has adhered to a “preservice professional education” model (Reber and Roberts 2010, p. 44). This model assumes that ministry is a profession, parallel with other helping professions, and that professional formation and education for ministry occur prior to entering the profession. For example, this educational paradigm is presumed in a landmark study of clergy education sponsored by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Daniel Aleshire, former executive director of the Association of Theological Schools, lauded the first volume of The Preparation for the Professions Series, Educating Clergy: Teaching Practices and Pastoral Imagination (Foster et al. 2006), as “[t]he most important study of North American theological education in this century” (Aleshire 2010, p. 512). The Carnegie Series described “three apprenticeships of professional education”: normative, cognitive, and practical—or, more colloquially, the being, knowing, and doing of professional formation (Foster et al. 2006, p. 5). In the preservice model, such professional formation occurs within a degree program. Thus, the team of researchers led by Charles R. Foster addressed neither the kind of learning that might occur in venues other than graduate theological education, such as non-degree programs offered by judicatories or bible institutes, nor the kind of learning that might happen or might need to happen after clergies graduate from seminary. Likewise, lifelong learning is mentioned on only a few of the 800+ pages of the encyclopedic Handbook of Theological Education in World Christianity (Werner et al. 2010). Yet, the preservice model of education cannot by itself provide the integration necessary for effective preaching.

Integration occurs only by practicing in the profession. In his “Introduction” to Educating Clergy, William M. Sullivan noted that the ability to (re)integrate knowledge with practice “provides the great challenge” for professional schools, including seminaries (Foster et al. 2006, p. 5). Thus, nearly every helping profession—medicine, nursing, social work, teaching, law—requires practitioners to continue their education beyond a professional degree. The most effective curricula for such continued learning go beyond simply updating one’s knowledge base, instead providing opportunities for professionals to exercise problem solving—often, through community-building learning opportunities—thus integrating continuing education and practice (Reber and Roberts 2010, pp. 44–46). The preservice model of education is necessarily incomplete without a form of ongoing education that can accompany the practitioner throughout a career of evolving expectations and changing contexts.

The lifelong learning needs of preachers are distinct from the education they might gain in a degree program. Specifically, the means and ends of preservice education differ from that of continuing education. Adult education, or andragogy, differs from classical pedagogy in its participative planning, design, and evaluation (Knowles 1970, p. 54). Adults learn best when they can shape their learning experiences to find answers to questions that arise in practice, when they are supported and challenged in a community of learners guided by a skilled facilitator, and when they are involved in assessing the outcomes and determining what to learn next (Reber and Roberts 2010, p. 86).

Succinctly, andragogy is based on the following six assumptions: (1) just-in-time learning, based on need; (2) self-directed participants who are agents of their own learning; (3) participants’ life experiences as a resource for learning; (4) a readiness to apply learning to real-life situations; (5) practical application to tasks and problems; and (6) internal motivation (St. Clair 2024, pp. 7–8). Where graduate theological education focuses on formation (Foster et al. 2006), lifelong learning for practitioners involves a more dialogical method designed for wrestling with complex problems and refining professional practice (Reber and Roberts 2010, p. 83). Thus, lifelong learning for ministry is a form of just-in-time learning in which the learner (practitioner) sets the agenda and determines their goals.

What does andragogy look like for preachers? D. Bruce Roberts reported on a persuasive example of peer group learning offered through the Methodist Educational Leave Society (Reber and Roberts 2010, pp. 86–89). This program in Alabama operated from 1985 to 1996 and included 130 Methodist preachers who met in groups ten to fifteen days per year, ranging from three to six years. Self-selected groups of 6–8 preachers were assigned a facilitator, who assisted them in deciding on learning goals, developing a learning plan, applying their learning, and evaluating their progress on a continued basis. The features of andragogy are clearly present in this program’s design, from self-direction by participants to practical application to tasks and problems. Furthermore, peer learning was a centerpiece of this program’s design, in which each group became a community of learners teaching each other. Roberts and his co-investigator, Robert E. Reber, also identified the important role of the facilitator in guiding the process and managing group dynamics (Reber and Roberts 2010, pp. 87–88). Based on interviews and surveys, they reported that “there is little doubt that the peer group process improved preaching in general as well as helped create new energy in pastoral leadership” (Reber and Roberts 2010, p. 88). Not only did preachers learn about preaching, but they also became better leaders in their congregations.

A ten-year initiative of Vanderbilt Divinity School to strengthen the quality of preaching provides another example. Established in 2013 with a grant from the Lilly Endowment, Inc., the program in homiletic peer-coaching was motivated by the fact “that preachers seldom experience ongoing mentoring or coaching after their seminary years” (McClure and Utley 2023, p. 1). The program equipped and trained preachers based on a collaborative peer-learning model. Such a program is rare. “There are few situations where preachers can reflect on their lives and practices as preachers with one another in groups that are well-coached with an eye toward vocational formation, renewal, change, and accountability” (McClure and Utley 2023, p. 1). This depiction of need fits precisely the distinctive qualities of adult learning described above.

4.3. Implications

How can congregational leaders tasked with the responsibility of preaching be nurtured and equipped for the lifelong learning they seek? The rich insights yielded by the quantitative data on the lifelong learning needs of Methodist preachers have implications on multiple levels: conceptual, institutional, congregational, and personal.

On a conceptual level, lifelong learning has meaning professionally and vocationally. Most (if not all) other helping professions have professional guilds that provide opportunity and accountability for ongoing professional development. The profession of ministry is exceptional. There are no common standards of care, competence, or excellence for congregational leaders or preachers, in particular. What counts as compelling, responsible, or effective preaching varies from sect to sect, denomination to denomination, culture to culture, and even congregation to congregation. Yet, preachers are practitioners of a helping profession who are in positions of public prominence. Continuous formation through lifelong learning is integral to maintaining a sense of pastoral identity and being fully equipped as a congregational leader. Thus, preachers have a professional obligation to renew and improve their craft on an ongoing basis despite and because of the contextually specific expectations they face.

As persons called by God and affirmed by the church through representative ministry, preachers also have a vocation obligation to themselves, God, and the church to grow continually in their life of faith and their proclamation of the gospel. Wesleyan theology emphasizes the importance of growth in sanctification, expecting continual growth toward Christian maturity. Without such growth in the person of the preacher, a Wesleyan understanding of grace cannot be effectively proclaimed with integrity. Preachers must find ways to attend to their own spiritual growth as they preach the importance of the same to others. Lifelong learning about preaching and the practice of preaching in itself can become spiritual disciplines conducive to professional and vocational growth. The practice of preaching, the activities of preparing a sermon, and the lifelong learning necessary to improve as a preacher can all become means of grace. How are preachers’ lifelong learning and vocational growth supported or hindered?

On an institutional level, there are many potential and actual supports and barriers to lifelong learning participation by preachers, including denominational policies, resource allocation, and other structural factors. Judicatory leaders, ministry educators, and program administrators should be attuned to practical considerations such as dedicating protected time for ongoing education, offering financial support for continuing formation, and designing inclusive, multilingual learning programs that reflect the diverse needs of preachers, particularly non-English-speaking pastors. Multivocational or bivocational preachers and those who are employed in ministries outside the judicatory’s purview face additional constraints of time and resources. Hospital chaplains, for example, often must take vacation days to attend denominationally required workshops. Bivocational pastors who work a secular job face similar constraints, receiving no “protected time” for professional development as a preacher, despite judicatory efforts to the contrary. Denominations and judicatories must invest in their preachers if they expect their preachers to invest in themselves.

Ecumenical partnerships can be leveraged to provide resources and learning opportunities for preachers in multiple languages—if differences in denominational culture and theological perspectives do not become insurmountable barriers. For example, how can las predicadoras (Spanish-speaking female preachers) in the UMC find collaborative learning opportunities in partnership with los predicadores (Spanish-speaking male preachers) in conservative denominations that do not allow women to preach? Gender identity and sexual orientation are often barriers to partnership. LGBTQIA+ preachers must be vigilant when attempting to partner with outside organizations and churches, many of which are hostile and threatening to their existence. These barriers require deep work to overcome, and preachers in marginalized groups should not be expected to do this work on behalf of the church. Thus, on a practical level, some potential ecumenical partnerships in lifelong learning for preaching are severely limited or prevented altogether.

On the congregational level, there is great potential for cultivating an ethos of lifelong learning. The congregation is the immediate context in which preaching is determined effective and faithful. What matters to the congregation has direct relevance to the preacher, regardless of their level of agreement. The sermon cannot effectively communicate the gospel if the listeners and preacher are not finding common ground to address common concerns. Potentially, there is much to be learned within the preacher’s immediate context, and this realization should provide motivation for learning. Yet, it often takes an outside perspective to see the water in which one swims. Lifelong learning often requires collaboration with others.

The ongoing educational development and spiritual growth of the preacher requires fostering a culture of mutual growth among preachers and between preachers and their listeners. However, survey respondents reported low levels of engagement in collaborative learning methods. This reality is contrary to the collaborative means of learning promoted in contemporary pedagogical paradigms in homiletics. Whether inspired by the image of “the roundtable pulpit” (McClure 1995), “place-centered preaching pedagogy” (Clark 2024), “the people’s sermon” (Hannan 2021), “Communal Prophetic Proclamation” (Schade 2019, p. 120), or the need for “improvisational teaching” (Alcántara 2020, p. 13), the idea of collaboration before, during, and after the sermon event is very much on the minds of modern-day homileticians. Barriers to collaboration may include a perceived lack of opportunity, time required to coordinate scheduling, navigating interpersonal and group dynamics, geographical distance, and a general sense of isolation among clergy.

Congregations can help preachers overcome barriers to collaborative learning by encouraging, resourcing, and valuing collaborative learning opportunities for their preachers. Local churches and regional networks can support regular mentoring sessions and peer learning cohorts, for example, by offering time and compensation for professional development and being open to what the preacher may learn from colleagues who preach in other contexts. Local churches can also encourage participation in digital or hybrid learning platforms to facilitate networking across geographic and demographic boundaries. Congregations can also publicly affirm ongoing learning as a vital part of their leader’s development.

On the personal level, the individual preacher must be ready and willing to learn. From the perspective of andragogy, the preacher as an adult learner must be able to identify a need, take initiative for learning how to meet that need, draw on their experience as a source of knowledge and wisdom, connect their learning to real-life situations, apply their learning to tasks and problems, and evaluate their success in order to determine what they need to learn next. The process of lifelong learning requires internal motivation and external support. As an adult learner, the preacher must be able to identify their next-level preaching goal, whatever that may mean for them in their context, and seek the necessary resources to learn how to achieve that goal. Identifying a need and setting an appropriate learning goal are critical steps in the process of lifelong learning. These steps can be facilitated through collaboration with both colleagues and parishioners, as the preacher seeks to improve their craft of preaching. Tools for learning include peer mentoring, collaborative goal setting, and self-directed learning communities. Finally, the preacher’s motivation and initiative may be tempered by the very real constraints of time and money, as indicated by survey respondents.

4.4. Limitations and Future Avenues of Research

This survey was limited in scope to two geographic conferences of one Protestant denomination. Additional research would need to be conducted to provide comparative data showing differences based on geographic region, theological commitments, denominational traditions, and prior educational experiences of preachers. The absence of random selection in the sampling process further limits the generalizability of findings from this study and underscores the need to interpret the results with caution. Although the sample was originally collected for evaluative rather than predictive purposes and was found to closely match combined conference demographics, respondents may over- or underrepresent unmeasured attitudinal and behavioral characteristics that influence preaching perceptions and practices. For this reason, future quantitative research seeking to draw broader generalizations should employ established probability sampling methods while collecting additional data relevant to the practice of preaching to ensure sample representativeness and reduce the likelihood of spurious or erroneous results.

Additionally, this study was limited to quantitative survey data, making it difficult to gain an understanding of the complex, lived experiences of preachers—particularly in relation to the prominent obstacle of time constraints and preachers’ hesitancy to engage in collaborative methods of sermon preparation and learning. Complementing this quantitative study with qualitative research methods could yield rich, contextualized insights into how and why time scarcity affects preachers’ professional development, for example. A future avenue of research with this survey population includes soliciting feedback from preaching cohorts and engaging in focus groups.

5. Conclusions

This quantitative assessment provides insight into the lifelong learning needs of Methodist preachers, though many questions remain. Overall findings provide insight into the needs of clergy as they aim to take their preaching to their perceived “next level” of practice in style or content. Respondents recognize a need for more support as well as express interest in pursuing continued learning opportunities, time allowing. This is a significant caveat: respondents identify time constraints as the biggest obstacle to continued learning.

Lifelong learning programs for preachers will need to make the case for how the investment of time and energy in preaching will benefit the preacher. The hard work of reviewing recordings of sermons (both one’s own and those of other preachers) to develop skills may be a hard sell. Likewise, the trust required to receive feedback on sermons must be built into programs providing such structured learning opportunities. Given the lukewarm responses expressed on this topic in the survey, it is likely that preachers generally lack a structured way of receiving effective feedback. Likewise, the collaborative potential of preaching seems unrealized among the preachers surveyed. Lifelong learning programs may need to cultivate an ethos of collaboration and prove the value of investing the time for collaboration for adult learners to recognize and embrace the value of this aspect of the preaching task.

Newer preachers, female preachers, and non-White preachers all express significantly more interest in improving their preaching support in the ways identified in this survey. As significant differences in demographic groups were discovered in this process, it is critical that educational program content and instructors reflect the demographics expressing interest in continued learning opportunities through visuals, examples/stories in content, and in instructor identities. Furthermore, the needs of preachers who primarily preach in languages other than English were not well represented in the survey sample. To learn about this subpopulation’s lifelong learning needs will require a survey conducted in their primary language, and lifelong learning opportunities will likewise need to be offered in languages other than English.

Shaping lifelong learning programming around these findings will help bolster successful curricular design, program outreach, and enrollment in educational offerings. Future research directions based on these results encourage exploration of some of the common challenges and pathways toward strengthening preacher impact that are identified from this research such as the following: improved preaching support, determining the approach one takes to managing preaching identity with congregational preferences, the role of preaching mentors, and the role of supportive individuals more broadly across a preacher’s career, the social and professional capital that a preacher may have or need as it impacts preaching style, preaching confidence, and preaching identity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.W.S. and M.M.; methodology, M.M. and R.P.C.; software, R.P.C.; validation, M.M. and R.P.C.; formal analysis, M.M. and R.P.C.; investigation, D.W.S. and M.M.; resources, M.M. and R.P.C.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.W.S. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, D.W.S.; visualization, R.P.C.; supervision, D.W.S. and M.M.; project administration, D.W.S.; funding acquisition, D.W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted with the support of a grant from Lilly Endowment Inc. through its Compelling Preaching Initiative, grant number 2023 1772.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Moravian University (11 November 2024), which determined it (#24-0060) exempt (category 2) from further review (45 CFR 46.104).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATS | Association of Theological Schools |

| DCOM | District Committee on Ministry |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| UMC | The United Methodist Church |

Notes

| 1 | In Table 1, the sample proportions of males and females differ significantly from the corresponding population proportion based on Z-test for equality of proportions [p < 0.05]. |

| 2 | In Figure 1, due to limited space, “Not At All Interested” category percentages of 5.0% or less are not labeled. |

| 3 | In Figure 2, due to limited space, “Very Frequently” category percentages of 5.0% or less are not labeled. |

| 4 | In Figure 5, due to limited space, “Very Often An Obstacle” category percentages of 5.0% or less are not labeled. |

References

- Alcántara, Jared E. 2020. On the Future of Teaching Preaching in the Midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acta Theologica 40: 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshire, Daniel O. 2010. Theological Education in North America. In Handbook of Theological Education in World Christianity: Theological Perspectives—Regional Surveys—Ecumenical Trends. Edited by Dietrich Werner, David Esterline, Namsoon Kang, Ruth Padilla DeBorst, Hwa Yung, Wonsuk Ma, Damon So and Miroslav Volf. Regnum Studies in Global Christianity Series; Oxford: Regnum. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Theological Schools (ATS). 2020. Standards of Accreditation for The Commission on Accrediting of The Association of Theological Schools. Available online: https://www.ats.edu/Standards-Of-Accreditation (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Austin, Thad S., and Katie R. Comeau. 2022. Caring for Clergy: Understanding a Disconnected Network of Providers. Eugene: Cascade. [Google Scholar]

- Blier, Helen. 2022. The Current State of Lifelong Learning Programs Webinar. ATS, December 8. Available online: https://www.ats.edu/eshop-events-one/details/42/The-Current-State-of-Lifelong-Learning-Programs-Webinar (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Blier, Helen. 2023. Why Lifelong Learning Matters. In Trust Center for Theological Schools. Podcast Episode 44, May 2. Available online: https://www.intrust.org/how-we-help/resource-center/podcast/ep-44-why-lifelong-learning-matters (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Blier, Helen, and Deborah H. C. Gin. 2022. Hot Takes and Trends in Theological Education. Association of Leaders in Lifelong Learning for Ministry (ALLLM) Webinar, April 7. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h7CJgn5CAUs (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Clark, E. Trey. 2024. Forming Preachers: An Examination of Four Homiletical Pedagogy Paradigms. Religions 15: 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Frazier, Elizabeth. 2021. Atando Cabos: Latinx Contributions to Theological Education. Theological Education Between the Times. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Charles R., Lisa E. Dahill, Lawrence A. Golemon, and Barbara Wang Tolentino. 2006. Educating Clergy: Teaching Practices and Pastoral Imagination. The Preparation for the Professions Series; San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Gin, Deborah, and Jo Ann Deasy. 2024. Ep. 83: A Misalignment in Theological Schools—And a Way Forward. In Trust Center Good Governance Podcast, December 23. Available online: https://www.intrust.org/how-we-help/resource-center/podcast/ep-83-a-misalignment-in-theological-schools-and-a-way-forward (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Gin, Deborah H. C. 2024. Mapping the Workforce of ATS Grads: Have Jobs and Needs Changed? ATS. Colloquy Online, September. Available online: https://www.ats.edu/files/galleries/mapping-the-workforce-of-ats-grads-have-jobs-changed.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Gin, Deborah H. C., Jo Ann Deasy, and Grego Pena-Camprubí. 2025. Reimagining the Role of Graduate Theological Education in Clergy Formation. Christian Higher Education 24: 148–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Justo L. 2015. The History of Theological Education. Nashville: Abingdon. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan, Shauna K. 2021. The Peoples’ Sermon: Preaching as a Ministry of the Whole Congregation. Minneapolis: Fortress. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, Malcolm S. 1970. The Modern Practice of Adult Education: Andragogy Versus Pedagogy. Chicago: Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lifeway Research. 2023. Protestant Churchgoer Views on Pastors’ Addressing Current Issues. Available online: https://research.lifeway.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/American-Churchgoers-Sept-2023-Current-Issues-Report.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- McClure, John S. 1995. The Roundtable Pulpit: Where Leadership and Preaching Meet. Nashville: Abingdon. [Google Scholar]

- McClure, John S., and Allie Utley, eds. 2023. Learning Together to Preach: How to Become an Effective Preaching Coach. Eugene: Cascade. [Google Scholar]

- Meinzer, Chris A. 2024. ATS Reports Favorable Preliminary Enrollment Data for Fall 2024. The Association of Theological Schools. The Commission on Accrediting. Available online: https://www.ats.edu/files/galleries/ats-reports-favorable-preliminary-enrollment-data-for-2024.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Reber, Robert E., and D. Bruce Roberts. 2010. A Lifelong Call to Learn: Continuing Education for Religious Leaders. Herndon: Alban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Schade, Leah D. 2019. Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Ted A. 2023. The End of Theological Education. Theological Education Between the Times. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- St. Clair, Ralf. 2024. Andragogy: Past and Present Potential. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 2024: 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, John. 2017. Upgrading Our Preaching: Professional Development for Preachers Today. In Text Messages: Preaching God’s Word in a Smartphone World. Edited by John Tucker. Eugene: Wipf and Stock, pp. 200–14. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, Dietrich, David Esterline, Namsoon Kang, and Joshva Raja, eds. 2010. Handbook of Theological Education in World Christianity: Theological Perspectives—Regional Surveys—Ecumenical Trends. Regnum Studies in Global Christianity. Oxford: Regnum. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).