Renaissance Vienna Under the Ottoman Threat: Rethinking the Biblical Imagery of the City (1532–1559)

Abstract

1. Introduction

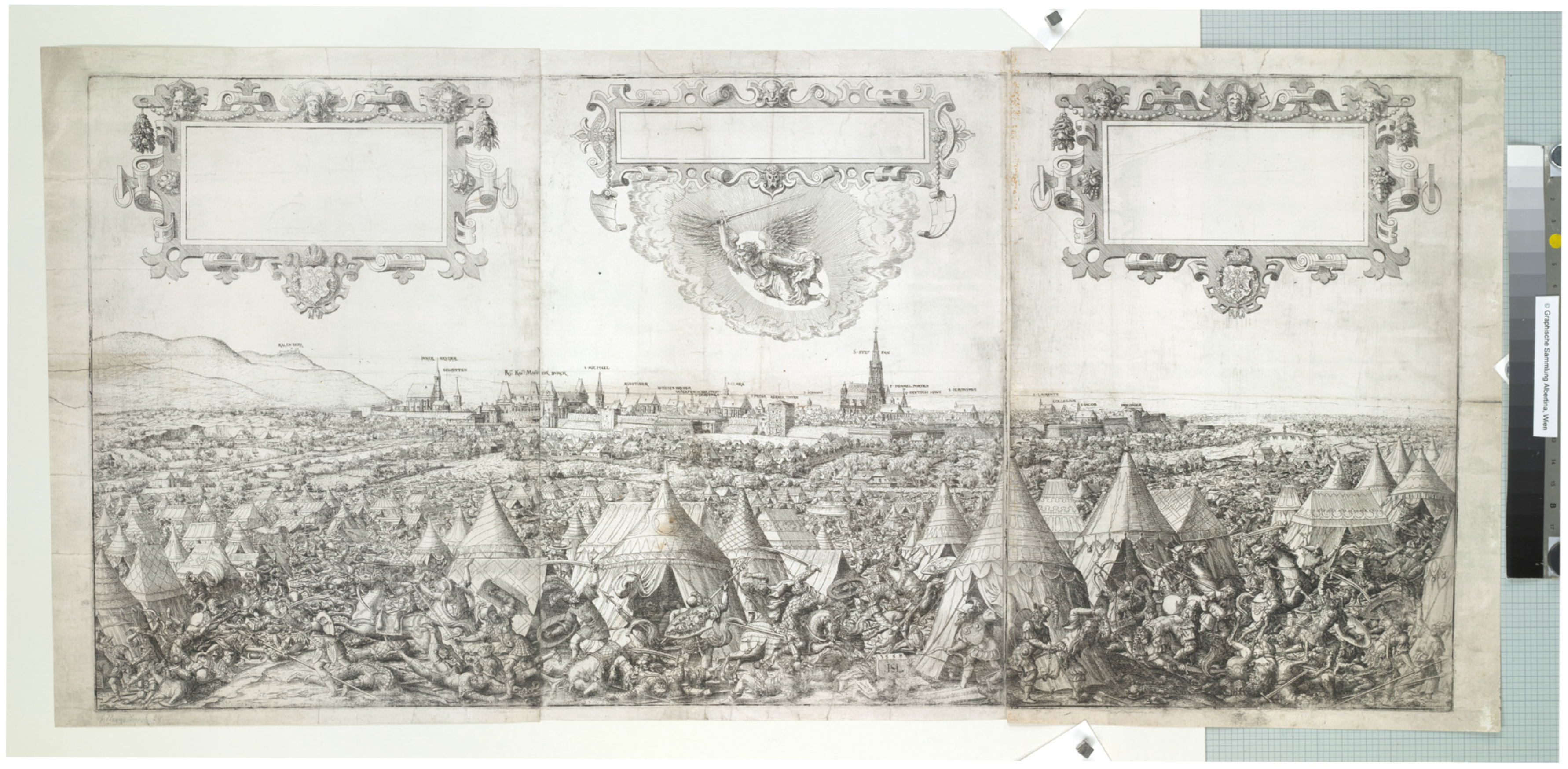

“Given that all Biblical history displays either God’s wrath or His grace and is written for the purpose of warning and admonishment, so too does the present glorious battle—taking place before the majestic city of Jerusalem, between the two mighty kings, the God-fearing Hezekiah of Judah and the blasphemer Sennacherib of Assyria—now stand before the renowned city of Vienna in Austria, as a reminder and admonition of God’s help in times past and future”.1

2. Historiographic Perspective on the Imagery of the Turks Before Vienna

2.1. Lautensack, Lazius, and Sennacherib Before Vienna

2.2. Vienna vs. the Turks: Urban Identity and Religious Antagonism

3. In the Beginning Was the Preached Word: Fabri’s (1532) Sermons Against the Turks

3.1. The Preaching Behind the Pictures: Luther, Fabri, and the Biblical Interpretation of the Turks

3.2. Vienna as Jerusalem, Suleyman as Sennacherib, and Ferdinand as Hezekiah

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Nachdem alle Biblische historia zorn oder huldt Gottess anzaigen, vnd zue warnungen oder vermanungen geschriben sein, ist auch gegenwertige herrliche schlacht, so sich vor der ansechenlichen Statt Hierusalem zwischen den zwayen grossmechtigen khünnigen, als dem gottsfurchtigen Ezechia in Juda vnd dem gottsslesterischen Sennacherib aus Assiria begeben, der weit berüembten Statt Wienn in Österreich zu errinerung vnd vermanung der empfangenen vnnd zuekhümfftigen göttlichen hilff khünstlich gestelt worden. |

| 2 | Confluit frequens contio, audit avide vocem pastoris, milites etiam, qui alioqui natura ferociores sunt, templum complent, piae ac religiosae rei sacrae operam dant, animo alacri et erecto quottidie supra modum concordibus votis Tyranni furientis adventum expectant. |

| 3 | Sunt fortassis plerique, Nausea ornatissime, qui me fortem & magnanimum putent, quod his turbulentissimis temporibus, aula relicta, ausus fuerim, huc me ad oves meas, in medios Turcarum exercitus & tumultus bellicos conferre. At ego mehercle multo praeclarius esse, et maioris animi opus existimo, quod ausus sim inter tot & tam varia nationum genera, de diversis absque dubio sectis, verbum Dei absque timore publicitus intonare. […]. Illud tamen mihi iure sumere possum, me et Lutheranos et Zvinglianos et Anabaptistas, sine omni contradictione, auditores habuisse. |

| 4 | Cogitate queso charissimi an forte non simus sub eadem conditione ne dicam damnatione, qui cum Hierosolymitis peccaverimus, ideo gladius domini educatur super nos. Avertetur autem facillime, & in vaginam mittetur, si humiliantes nos, nec nostris confisi viribus confugiamus ad dominum. |

| 5 | gentem peccatorum fortasse nostrorum ultricem ac flagellum orbis Christiani, de extremis terrae finibus in similitudinem Aquilae volantis cum impetu. |

| 6 | Trepidantibus vobis […] ob immanissimi Turcorum Tyranni […] impressionem […] urbis Viennensis obsidionem, & expugnationem forte cogitantibus ». |

| 7 | Viriliter agite et confortamini. Nolite timere, nec paveatis Regem Assyriorum, & universam multitudinem quae est cum eo, multo enim plures nobiscum sunt quam cum illo, Cum illo enim est brachium Carneum, nobiscum Dominus Deus noster, qui auxiliator, pugnatque pro nobis. |

| 8 | Occidit autem una nocte angelus, Centum octoginta quinque millia. Cumque Senacherib diluculo surrexisset, Vidit omnia corpora mortuorum et recedens abiit, Et reversus est rex Assyriorum & mansit in Ninive |

| 9 | Hoc honorificum signum erectum fuit in monte Calvariae titulum habens Hebraicae Grecae ac Latinae scriptum, quod hoc signum habiturum esset triumphum per tres orbis partes Europam videlicet Asiam & Aphricam, ac inter omnes nationes, ita ut ab ortu solis usque ad occasum fieret manifestum magnum nomen eius. |

| 10 | A cuius Ezechiae regis exemplo nos qui alteram a Turcis obsidionem expectamus quotidie, docemur ut & nos muros nostros, turres nostras & propugnacula nostra fortiora reddamus. Sed inventi sunt nostris temporibus non nulli de se multa praesumentes, qui etiam suis editis libris ac tractatibus, ausi sunt in publico docere, nemini Christiano licere praeliari contra Turcos, quoniam omne bellum, quod contra Turcos moveatur, evangelio contrarietur |

| 11 | contra impios & sanguinis Christiani persecutores atrocissimos turcos. |

References

- Almási, Gábor. 2009. The Uses of Humanism: Johannes Sambucus (1531–1584), Andreas Dudith (1533–1589), and the Republic of Letters in East Central Europe. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Beham, Bartel. 1529. Vienna obsessa a Solimanno anno domini 1529. Das Feldlager der Türken vor Wien mit Ansicht der Stadt von Süden. Pen and Ink Drawing. Inventory Number 97022. Vienna: Wien Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Buttlar, Gertrud. 1974. Die Niederlage der Türken am Steinfeld 1532. Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst. [Google Scholar]

- Camesina, Albert. 1856. Über Lautensacks Ansicht Wiens vom Jahre 1558 mit dem von Wolfgang Laz gelieferten Texte und Beiträgen zur Lebensgeschichte des Letzteren. Berichte und Mitteilungen des Altertums-Vereines zu Wien 1: 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Camesina, Albert, and Wolfgang Lazius. 1855. Hirschvogel’s und Lautensack’s Ansichten von Wien in den Jahren 1547 und 1558, nebst erklärendem Text zu letzterer von Wolfgang Laz. Vienna: Wien, kais.-königl. Hof- u. Staatsdruckerei. [Google Scholar]

- Colding Smith, Charlotte. 2014. Images of Islam, 1453–1600: Turks in Germany and Central Europe. London: Pickering and Chatto. [Google Scholar]

- Czeike, Felix. 1974. Das Wiener Stadtbild in Gesamtansichten. Die Darstellungen der gotischen Stadt. Handbuch der Stadt Wien 88: II, 13–44. [Google Scholar]

- Czeike, Felix. 1994a. Lautensack Hans Sebald. In Historisches Lexikon Wien in 5 Bänden. Vienna: Kremayr and Scheriau, p. 694. [Google Scholar]

- Czeike, Felix. 1994b. Lazius Wolfgang. In Historisches Lexikon Wien in 5 Bänden. vol. 3: Ha-La. Vienna: Kremayr and Scheriau, p. 699. [Google Scholar]

- Donecker, Stefan, Petra Svatek, and Elisabeth Klecker. 2021. Wolfgang Lazius (1514–1565): Geschichtsschreibung, Kartographie und Altertumswissenschaft im Wien des 16. Jahrhunderts. Vienna: Praesens Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Eisler, Max. 1919. Historischer Atlas des Wiener Stadtbildes. Vienna: Verlag der Deutschösterreichischen Staatsdruckerei. [Google Scholar]

- Fabri, Johann. 1528. Oratio de origine, potentia ac tyrannide Thurcorum. Ad Serenissimum et potentissimum Henricum Angliae et Franciae Regem. etc. Eius nominis Octavum. Dicta Londini a D. Ioanne Fabro. Vienna: Johann Singriener d.Ä. [Google Scholar]

- Fabri, Johann. 1532. Sermones consolatorii: Reverendiss. in Christo Patris, ac Domini, Domini Ioannis Fabri Episcopi Viennensis. habiti ad plebem eius, ac Christi milites, super immanissimi Turcorum Tyranni altera imminenti obsidione Inclytae ubris Viennensis. Vienna: Johann Singriener d.Ä. [Google Scholar]

- Feierfeil, Wenzel. 1907. Die Türkenpredigten des Wiener Bischofs Johannes Fabri aus dem Jahre 1532. Jahresbericht des Kaiserlich-Königlichen Staats- Obergymnasiums in Teplitz-Schönau 7: 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Karl. 1996/1997. Blickpunkt Wien—Das kartographische Interesse an der von den Türken bedrohten Stadt im 16. Jahrhundert. Jahrbuch des Vereines für Geschichte der Stadt Wien 52/53: 101–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Karl. 2020. Die Meldeman-Rundansicht im Rahmen der zeitgenössischen Darstellungen der bedrohten Stadt. In Die Osmanen vor Wien. Der Meldeman-Plan von 1529/1530: Sensation, Propaganda und Stadtbild. Edited by Ferdinand Opll and Martin Scheutz. Vienna: Böhlau, pp. 219–39. [Google Scholar]

- Grebe, Anja. 2014. Lautensack, Hanns. In Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon: Die bildenden Künstler aller Zeiten und Völker. vol. 83: Lalix—Leibowitz. Edited by Andreas Beyer, Bénédicte Savoy and Wolf Tegethoff. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 307–8. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmsmann, Damaris. 2016. Krieg mit dem Wort: Türkenpredigten des 16. Jahrhunderts im Alten Reich. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Günzel, Stephan. 2008. Spatial Turn—Topographical Turn—Topological Turn. Über die Unterschiede zwischen Raumparadigmen. In Spatial Turn: Das Raumparadigma in den Kultur- und Sozialwissenschaften. Edited by Jörg Döring and Tristan Thielmann. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, pp. 219–38. [Google Scholar]

- Helbling, Leo. 1941. Dr. Johann Fabri: Generalvikar von Konstanz und Bischof von Wien (1478–1541). Beiträge zu seiner Lebensgeschichte. Münster and Westfalen: Aschendorff. [Google Scholar]

- Hollstein, Friedrich W. 1978. Hollstein’s German Engravings Etchings and Woodcuts. Ca. 1400–1700. vol. XXI: Georg Lang to Hans Leinberger. Edited by Fedja Anzelewsky and Robert Zijlma. Amsterdam: Van Gent and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Immenkötter, Herbert. 1984. Johann Fabri (1478–1541). In Katholische Theologen der Reformationszeit. Edited by Erwin Iserloh. Münster: Aschendorff, vol. 1, pp. 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Knappe, Emil. 1949. Die Geschichte der Türkenpredigt in Wien. Ein Beitrag zur Kulturgeschichte einer Stadt während der Türkenzeit. Ph.D. thesis, Universität Wien, Philosophische Fakultät, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Koreny, Fritz. 2003. Hanns Lautensack. Die Vernichtung von Sanheribs Heer als Allegorie auf die Niederlage der Türken vor Wien 1529. In Geschichte der bildenden Kunst in Österreich. vol. 3: Spätmittelalter und Renaissance. Edited by Artur Rosenauer, Christian Beaufort-Spontin and Hermann Fillitz. Munich: Prestel, p. 569. [Google Scholar]

- Lautensack, Hanns. 1552a. Nürnberg von Osten. Etching. Inventory Number DG1963/99. Vienna: Albertina Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Lautensack, Hanns. 1552b. Nürnberg von Westen. Etching and Engraving. Inventory Number DG1963/101. Vienna: Albertina Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Lautensack, Hanns. 1554. Wolfgang Lazius. Engraving and Etching. Inventory Number DG1933/44. Vienna: Albertina Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Lautensack, Hanns. 1556. Ferdinand I., König von Böhmen. Engraving, Etching. Inventory Number DG1933/38. Vienna: Albertina Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Lautensack, Hanns. 1558. Der Untergang von Sanheribs Heer. Allegorie auf den Sieg über die Türken vor Wien. Etching. Inventory Number DG1933/2281/1-3. Vienna: Albertina Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Lautensack, Hanns. 1559a. Türken vor Wien. Etching. Inventory Number DG1964/178/1-2. Vienna: Albertina Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Lautensack, Hanns. 1559b. Ansicht der Stadt Wien von Südwesten mit Untergang des Assyrerkönigs Sennacherib vor Jerusalem (allegorisch für die Türkenbelagerung 1529). Etching. Inventory Number HMW 306423. Vienna: Wien Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Lautensack, Hanns. 1559c. Ansicht der Stadt Wien von Südwesten mit Untergang des Assyrerkönigs Sennacherib vor Jerusalem (allegorisch für die Türkenbelagerung 1529). Etching. Inventory Number 31041. Vienna: Wien Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Lazius, Wolfgang. 1546. Vienna Austriae. Rerum Viennensium Commentarij in Quartuor Libros distincti. Basel: Joannes Oporinus. [Google Scholar]

- Lazius, Wolfgang. 1558/1559. Text zu Lautensacks Ansicht von Wien (Inv. 1933/2281). DG 1963/103/1-6. Vienna: Albertina Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Lazius, Wolfgang. n.d.a. Der Statt Wienn Endtliche beschreibung, was sich wehrunder vergangner zeit verloffen hierinen zu vernemmen, Manuscript of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, cod. 8459, fol. 22r-34r.

- Lazius, Wolfgang. n.d.b. Descriptio germanica urbis Vindobonensis, Manuscript of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Codex 8219, fol. 34r-39v.

- Leeb, Rudolf. 2003. Der Streit um den wahren Glauben—Reformation und Gegenreformation in Österreich. In Geschichte des Christentums in Österreich: Von der Spätantike bis zur Gegenwart. Edited by Rudolf Leeb, Maximilian Liebmann, Georg Scheibelreiter and Peter G. Tropper. Wien: Ueberreuter, pp. 145–279. [Google Scholar]

- Leeb, Rudolf, Walter Öhlinger, and Karl Vocelka. 2017. Brennen für den Glauben: Wien nach Luther. Salzburg and Wien: Residenz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Louthan, Howard. 1997. The Quest for Compromise. Peacemakers in Counter-Reformation Vienna. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luther, Martin. 1518. Resolutiones Disputationum de Virtute Indulgentiarum. Basel: Froben. [Google Scholar]

- Luther, Martin. 1529. Vom Kriege wider die Türken. Wittenberg: Hans Weiss. [Google Scholar]

- Luther, Martin. 1530. Das Newe Testament Mar. Luthers. Wittenberg: Hans Lufft. [Google Scholar]

- Luther, Martin. 1533–1534. De Biblie vth der vthleggine Doctoris Martini Luthers yn dyth düdesche vlitich vthgesettet, mit sundergen vnderrichtingen, als men seen mach. Lübeck: Ludwig Dietz. [Google Scholar]

- Luther, Martin. 1534. Biblia, das ist die gantze Heilige Schrifft Deudsch. Wittenberg: Hans Lufft. [Google Scholar]

- Moger, Jourden Travis. 2016. Gog at Vienna: Three woodcut images of the Turks as apocalyptic destroyers in early editions of the Luther bible. Journal of the Bible and its Reception 3: 255–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nausea, Friedrich, and Valerius Philarchus. 1550. Epistolarvm Miscellanearum ad Fridericum Nauseam Blancicampianum, Episcopum Viennensem, etc. sigularium personarum, Libri X: Harum uerò editionis rationem atque usum in Præfatione reperies. Additvs Est Svb Finem Operis, eiusdem Episcopi Viennensis lucubrationum Catalogus. Basel: Johannes Oporinus. [Google Scholar]

- Neubeck, Johann Caspar. 1594. Zwo Christliche Sieg vnd Lob Predigten, wegen etlich ansehnlicher Victorien wider den Türcken Anno Domini 1593. Vienna: Leonhard Formica. [Google Scholar]

- Opll, Ferdinand. 2002a. Zum städtischen Identitätsbegriff im Spätmittelalter und in der frühen Neuzeit: Das Beispiel Wien. In Stadt und Prosopographie. Zur quellenmäßigen Erforschung von Personen und sozialen Gruppen in der Stadt des späten Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit. Edited by Peter Csendes and Johannes Seidl. Linz: Österreichischer Arbeitskreis für Stadtgeschichtsforschung, pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Opll, Ferdinand. 2002b. Was ist Wien? Studien zur städtischen Identität in Spätmittelalter und Früher Neuzeit (13. bis frühes 18. Jahrhundert). Studien zu Wiener Geschichte. Jahrbuch des Vereins für Geschichte der Stadt Wien 57/58: 125–96. [Google Scholar]

- Opll, Ferdinand. 2004. Innensicht und Außensicht. Überlegungen zum Selbst- und Fremdverständnis Wiens im 16. Jahrhundert. Wiener Geschichtsblätter 59: 188–208. [Google Scholar]

- Opll, Ferdinand. 2008/2009. Die Wiener Türkenbelagerungen und das kollektive Gedächtnis der Stadt. Studien zur Wiener Geschichte. Jahrbuch des Vereins für Geschichte der Stadt Wien 64/65: 171–97. [Google Scholar]

- Opll, Ferdinand. 2013. Wien und die türkische Bedrohung (16.–18. Jahrhundert): Überlegungen und Beobachtungen zu Stadtentwicklung und Identität. In Das Bild des Feindes: Konstruktion von Antagonismen und Kulturtransfer im Zeitalter der Türkenkriege: Ostmitteleuropa, Italien und Osmanisches Reich. Edited by Eckhard Leuschner and Thomas Wünsch. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, pp. 183–97. [Google Scholar]

- Opll, Ferdinand. 2023a. Die Stadt sehen: Frühe Stadtdarstellungen von Wien in ihrem thematischen und internationalen Kontext. Vienna: Böhlau. [Google Scholar]

- Opll, Ferdinand. 2023b. Wien um 1500—Das Antlitz der Stadt in Stadtbildern und Stadtplänen im internationalen Kontext. Jahrbuch des Kunsthistorischen Museums Wien 22: 171–83. [Google Scholar]

- Opll, Ferdinand, and Martin Scheutz. 2020. Die Osmanen vor Wien. Der Meldeman-Plan von 1529/1530: Sensation, Propaganda und Stadtbild. Vienna: Böhlau. [Google Scholar]

- Opll, Ferdinand, and Martin Stürzlinger. 2013. Wiener Ansichten und Pläne von den Anfängen bis 1609: Mit einem Neufund aus Gorizia/Görz aus der Mitte des 16. Jahrhunderts. Vienna: Verein für Geschichte der Stadt Wien. [Google Scholar]

- Opll, Ferdinand, Heike Krause, and Christoph Sonnlechner. 2017. Wien als Festungsstadt im 16. Jahrhundert: Zum kartografischen Werk der Mailänder Familie Angielini. Vienna, Cologne and Weimar: Böhlau Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Poumarède, Géraud. 2009. Pour en finir avec la Croisade: Mythes et réalités de la lutte contre les Turcs au XVIe et VIIe siècles. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, Clarisse. 2015. La frontière incertaine. Recomposition de l’identité chrétienne à Vienne au XVIe siècle (1523–1594). Ph.D. thesis, Sorbonne Université, Centre Roland Mousnier (UMR 8596), Paris, France, November 20. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, Clarisse. 2023. An Erasmian Jewish Convert in 16th Century Vienna? Christian Concord and Jewish Sources in the Work of Paulus Weidner. Religions 14: 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenauer, Artur, Christian Beaufort-Spontin, and Hermann Fillitz. 2003. Geschichte der bildenden Kunst in Österreich. Vol. 3: Spätmittelalter und Renaissance. Munich: Prestel. [Google Scholar]

- Sagstetter, Urban. 1567. Gaistliche Kriegsrüstung. Vienna: Caspar Stainhofer. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Annegrit. 1957. Hanns Lautensack. Nürnberg: Selbstverlag des Vereins für Geschichte der Stadt Nürnberg. [Google Scholar]

- Svatek, Petra. 2020. Die Wiener Kartographie im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Eine Analyse im Kontext der “Cultural Turns”. In Die Osmanen vor Wien. Der Meldeman-Plan von 1529/1530: Sensation, Propaganda und Stadtbild. Edited by Ferdinand Opll and Martin Scheutz. Vienna: Böhlau, pp. 187–99. [Google Scholar]

- Vocelka, Karl, and Anita Traninger. 2003. Wien: Geschichte einer Stadt, vol. 2: Die frühneuzeitliche Residenz (16. bis 18. Jahrhundert). Vienna: Böhlau. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelbauer, Thomas. 2003. Ständefreiheit und Fürstenmacht. Länder und Untertaten des Hauses Habsburg im konfessionellen Zeitalter. Vienna: Ueberreuter, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roche, C. Renaissance Vienna Under the Ottoman Threat: Rethinking the Biblical Imagery of the City (1532–1559). Religions 2025, 16, 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060784

Roche C. Renaissance Vienna Under the Ottoman Threat: Rethinking the Biblical Imagery of the City (1532–1559). Religions. 2025; 16(6):784. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060784

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoche, Clarisse. 2025. "Renaissance Vienna Under the Ottoman Threat: Rethinking the Biblical Imagery of the City (1532–1559)" Religions 16, no. 6: 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060784

APA StyleRoche, C. (2025). Renaissance Vienna Under the Ottoman Threat: Rethinking the Biblical Imagery of the City (1532–1559). Religions, 16(6), 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060784