Science Expanding Amid Political Challenges: Translation Activities During the al-Mutawakkil ‘Alā’llāh Period (232–247 H/847–861 CE)

Abstract

1. Introduction: Historical Context Before the Caliph al-Mutawakkil ‘Alā’llāh

2. Political Instability and Suppressed Debates: The Impact of al-Mutawakkil’s Political Activities on Translation Efforts

3. Translation Initiatives and Power Dynamics: Shaping the Golden Age of Translation Under al-Mutawakkil

4. Conclusions

Funding

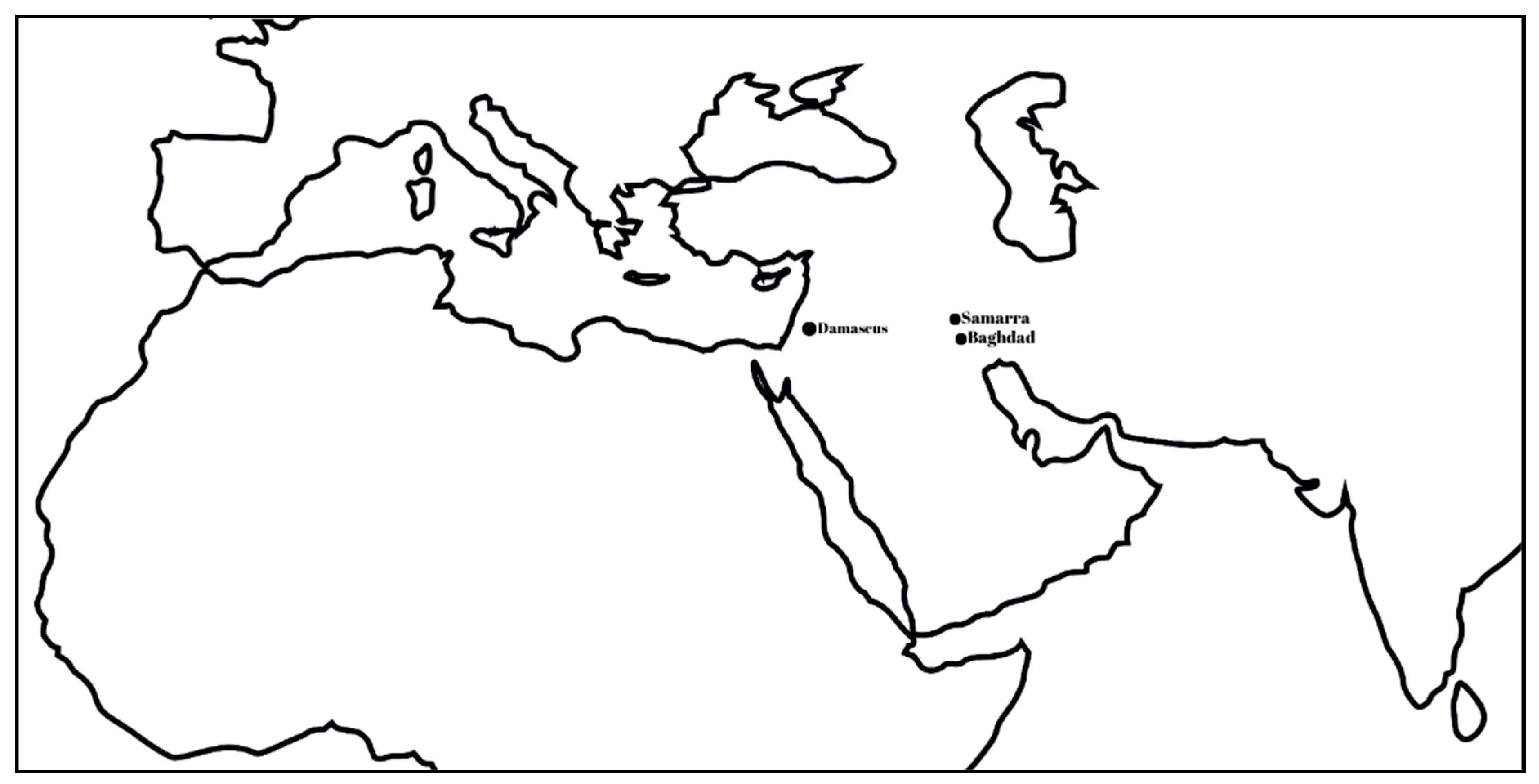

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

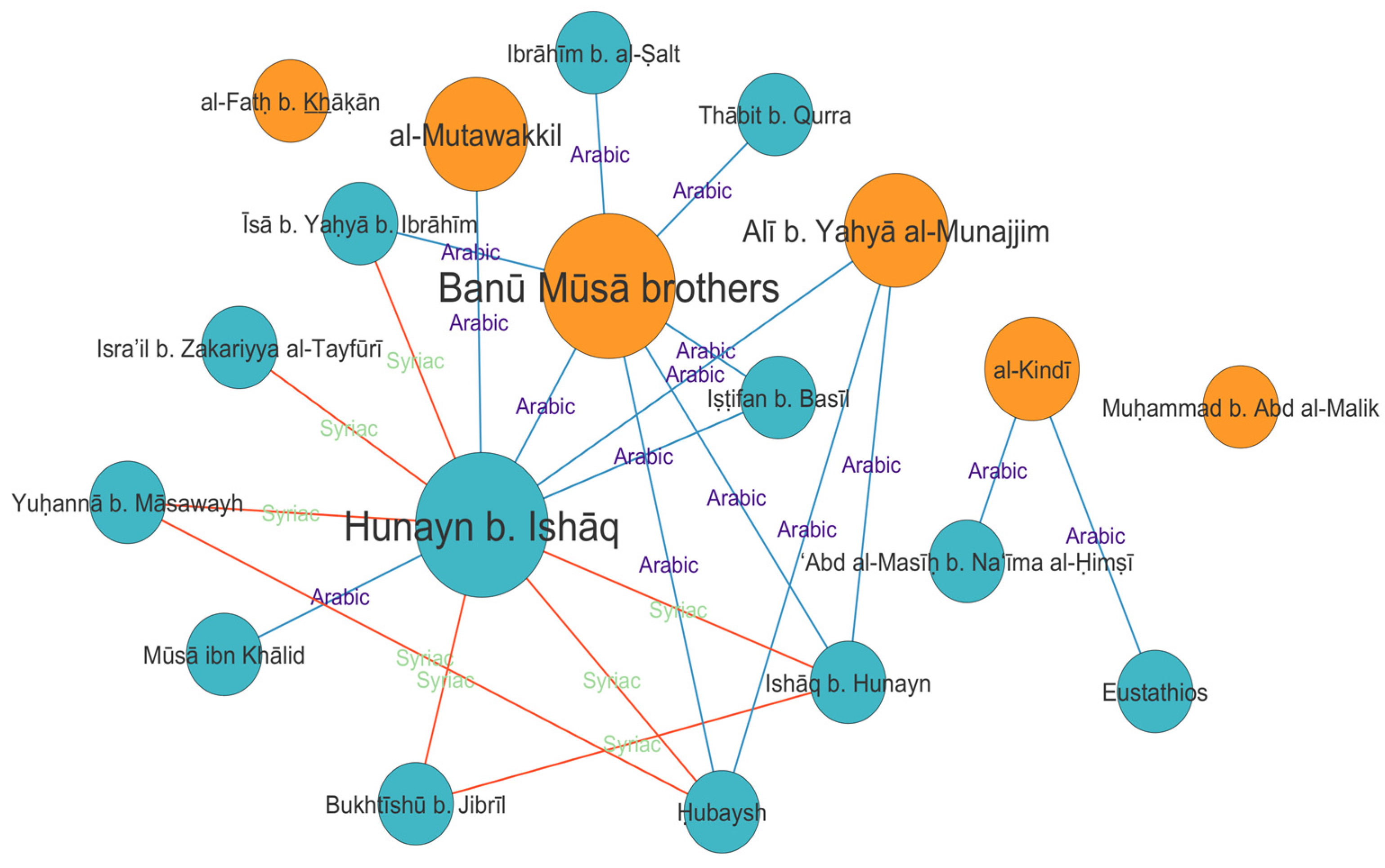

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Scholars have extensively examined translation activities, proposing numerous periodizations and interpretations of translation efforts in the Islamic world over the past two centuries. Modern researchers generally divide into two main groups regarding the origins of translation activities. The first group maintains that translation efforts began during the Umayyad period, whereas the second argues they emerged during the Abbasid era (Gutas 1999; Pormann and Savage-Smith 2007; Saliba 2011). Consequently, the latter group frequently attributes all activities from the Umayyads to the Abbasids or dismisses individuals from the earlier period as mere historical figures. At the heart of this debate lies a fundamental question: Should translation be viewed as an activity or a organized movement during these periods? When examining early translation efforts, it becomes evident that the period from the late reign of al-Ma’mun to nearly a century afterward marked a phase of systematic and intensified activity. Nonetheless, even during this period, it remains debatable whether translation efforts can be classified as a fully organized movement. Before and after this phase, translation activities appear to have fluctuated, alternating between periods of decline and resurgence. Drawing on the framework of my study, I present this phenomenon as an activity rather than an organized movement and have provided a concise overview of its trajectory leading up to the reign of al-Mutawakkil. Additionally, for a detailed analysis of the concept of Early Islam (Yılmaz et al. 2024). |

| 2 | For a detailed discussion on the scholarly activities of the Syriacs during the Umayyad period, see (Şenel 2021, 2022; Hugonnard-Roche 2007; D. King 2019). |

| 3 | Meyerhof mistakenly considered the city of Karkh as a location in Baghdad. He failed to recognize the existence of cities with similar names (Meyerhof 1926, p. 704). |

| 4 | İhsanoğlu, who has authored a comprehensive study on Bayt al-Ḥikma, does not consider Yaḥyā b. Khālid b. Barmak as its founder but rather as someone who served there along with the caliph (İhsanoğlu 2023). |

| 5 | Al-Mutawakkil placed great importance on poets and actively fostered their development within the court. During his reign, Arabic poetry evolved through interactions with diverse cultural influences, adopting new literary forms, which poets then performed in the courtly setting (Mas‘ūdī 1988, vol. 4, pp. 3–40; Aslan 2022, pp. 11–12). |

| 6 | The abolition of the Mihna under al-Mutawakkil marked a decisive moment in Abbasid intellectual history, shifting the state’s ideological orientation toward Sunni traditionalism. This shift coincided with al-Mutawakkil’s attempts to honor Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal, the prominent traditionist persecuted during the Mihna. However, despite the caliph’s overtures, Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal remained distant from state patronage and rejected official recognition, maintaining his independence from political authority (Muḥammad ’Ābid al-Jābirī 2019). Western scholars have often equated the Mihna with Mu‘tazilism; however, this perspective does not fully capture the diversity of theological positions involved in the controversy. Those who supported the doctrine of the createdness of the Qur’an were not exclusively Mu‘tazilites but also included Kharijites, Zaydis, Murji’ites, and Rafidites. Al-Mutawakkil’s policies, particularly his appointments, should therefore be viewed not merely as a reaction against Mu‘tazilism but as part of a broader effort to redefine the religious and political landscape of the Abbasid Caliphate (Hinds 1993, vol. 7, pp. 2–6; Melchert 1997, 2019). While some scholars argue that this ideological transition influenced al-Mutawakkil’s approach to translation—favoring scientific and medical works over speculative philosophy—recent scholarship suggests that his patronage decisions were shaped by a broader framework of Abbasid administrative continuity. His preference for Quraysh lineage and Basra-educated officials, a pattern also observed under al-Ma’mun, demonstrates that his intellectual policies were not solely dictated by doctrinal shifts but were also informed by established bureaucratic and political considerations (Melchert 2019, pp. 106–19). While discussions about al-Mutawakkil’s views on speculative philosophy continue, his rule did not halt philosophical translation. Instead, it signified a reorganization of the patronage systems that supported scientific and medical translations. This change indicates a transition in Abbasid intellectual priorities rather than a complete stifling of philosophical exploration. |

| 7 | During the reign of Abbasid Caliph al-Mutawakkil, elections for the Christian patriarch were marked by significant controversy and intrigue. Disputes in these elections, coupled with the sudden deaths of several candidates, prompted al-Mutawakkil to intervene in the process. Notably, the interference of palace doctors Buhtishu and other influential Christian bureaucrats in the elections elicited a strong reaction from the caliph. Consequently, Theodore, elected patriarch through bribery and manipulation, was imprisoned shortly thereafter, leading to increased pressure on Christians in Sāmarrā. Churches were demolished, clergy members were exiled, and Christian officials were removed from their government positions (Mārī b. Sulaymān 1899; Öztürk 2012; Kırkpınar 1996). Furthermore, al-Mutawakkil issued a decree in 235 (849) demanding the removal of Christian officials from state roles. However, it was noted that Christians continued to serve at state levels in the years that followed. Events such as the mass dismissal of Christian officials in Sāmarrā in 238 (852) and the destruction of patriarch tombs are directly linked to the political tensions of the era. Christian sources suggest that al-Mutawakkil’s anger towards Buhtishu provoked these harsh measures. Similarly, public pressure and the bureaucratic influence of Christians compelled al-Mutawakkil to make new decisions consistently. Nevertheless, it can be understood that even his severe policies were not fully realized in the long term, and Christians persisted within the state. For a detailed analysis of al-Mutawakkil’s activities toward his Christian subjects, consult Levent Öztürk, İslam Toplumunda Hristiyanlar (Christians in Islamic Society) (Öztürk 2012). |

| 8 | Ibn Juljul mentions a translator named Yaḥyā b. Hārūn as part of the group of translators surrounding Hunayn. However, Hunayn himself does not refer to anyone by this name. Instead, he mentions Īsā b. Yaḥyā in his epistle, attributing several Arabic translations to him. Uwe Vagelpohl and Ignacio Sánchez, who examine patrons and translators in biographical sources, do not provide any information about this individual. However, it is likely that this figure should be identified as ʿĪsā b. Yaḥyā (Ḥunayn b. Ishāq 2005; Ibn Juljul 1985, p. 69; Vagelpohl and Sánchez 2022, p. 306). |

| 9 | Among the scholars supported by al-Fatḥ was al-Jāḥiẓ, who in turn authored works such as The Virtues of the Turks (Manāqib al-Turk), Ar-Radd ʿalā al-Naṣārā (The Refutation Against the Christians), Al-Tāj fī Akhlāq al-Mulūk (The Crown on the Ethics of Kings) specifically for him (Ibn al-Nadīm 2014, pp. 578–88; Şeşen 1993; Toorawa 2005). |

| 10 | Hunayn retranslated some of the books previously translated for al-Kindī, possibly to refine their content, adapt them to new concepts, or apply updated translation methods (Adamson and Pormann 2012; Şahin 2018). However, Treiger interprets these retranslations differently, viewing them as part of a rivalry between two Christian communities—the Nestorians and the Melkites. According to him, the Melkites formed the group of translators around al-Kindī, and their translations were often criticized. In contrast, the Nestorians, particularly those within Hunayn’s intellectual circle, were portrayed more favorably. Many of the works listed in Hunayn’s Risāla were initially translated into Syriac, and their patrons were primarily Nestorian scholars. Treiger notes this reflects an implicit attempt to elevate the Nestorians as the group producing superior translations (Treiger 2022). |

| 11 | Although Yuḥannā passed away in the mid—reign of al-Mutawakkil, Ḥunayn b. Ishāq translated fī tarkīb al-adwiya (On the Composition of Drugs) from Greek into Syriac for him during this period (Ḥunayn b. Ishāq 2005, p. 45). |

| 12 | For the works translated by Hunayn into Arabic and Syriac, as well as his original compositions, see (Ibn Abī Uṣaybi‘ah n.d.; Sa’di 1934; Watt 2021). |

| 13 | To evaluate the translation method, see (Brock 1991; Acat et al. 2018). |

| 14 | In addition to his translation efforts, Ishāq also authored original works upon request from the Abbasid court. One notable example was a treatise commissioned by Qabīha, the wife of Caliph al-Mutawakkil, who requested a work on embryology. In response, Ḥunayn b. Ishāq composed Kitāb al-Mawlūdīn li-Samāniyyat Ashur (The Book of Those Born in Eight Months), reflecting his expertise in medical sciences (Ibn Abī Uṣaybi‘ah n.d., p. 273; Gutas 1999, p. 126). |

References

- Abdulla, Adnan K. 2021. Translation in the Arab World. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Acat, Yaşar, Ahmet Yasin Tomakin, and Harun Takcı. 2018. Tercüme Hareketleri Döneminde Yunanca-Süryanice-Arapça Çeviri Örnekleri Ekseninde Bir Değerlendirme. In Din Bilimleri: Klasik Sorunlar-Güncel Tartışmalar. Edited by M. Nesim Doru and Ömer Bozkurt. Mardin: Mardin Üniversitesi Yayınları, pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Adamson, Peter. 2006. Vision, Light and Color in al-Kindī, Ptolemy and the Ancient Commentators. Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 16: 207–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, Peter. 2007. Al-Kindī. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adamson, Peter, and Peter Pormann. 2012. The Philosophical Works of al-Kindī. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, Zahir. 2022. Hayru’l-Kırâ fī Sharḥ Umm al-Qurā: Muḥammad b. ’Abd al-Mun’im al-Jawjarī. İstanbul: Kitap Dünyası Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Sebastian. 1991. The Syriac Background to Ḥunayn’s Translation Techniques. ARAM 3: 139–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bsoul, Labeeb Ahmed. 2019. Translation Movement and Acculturation in the Medieval Islamic World. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Chipman, Leigh. 2021. Dioscorides. In Encyclopaedia of Islam Three Online. Leiden: Brill. Available online: https://referenceworks.brill.com/doi/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_26047 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- D’Ancona, Cristina. 2011. Translations from Greek into Arabic. In Encyclopedia of Medieval Philosophy. Edited by Henrik Lagerlund. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 1318–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ancona, Cristina. 2015. ‘“Arisṭū ‘inda l-‘Arab,” and Beyond’. In Aristotle and the Arabic Tradition, 1st ed. Edited by Ahmed Alwishah and Josh Hayes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endress, Gerhard. 1987. ‘Die Wissenschaftliche Literatur’. In Grundriss Der Arabischen Philologie. Edited by Gatje Helmut. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 400–506. [Google Scholar]

- Endress, Gerhard. 1992. ‘Die Wissenschaftliche Literatur’. In Grundriss Der Arabischen Philologie. Edited by Wolfdietrich Fischer. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, vol. 3, pp. 3–152. [Google Scholar]

- Endress, Gerhard. 1997. ‘The Circle of al-Kindī: Early Arabic Translations and the Rise of Islamic Philosophy’. In The Ancient Tradition in Christian and Islamic Hellenism: Studies in the Transmission of Greek Philosophy and Sciences. Edited by Gerhard Endress and Remke Kruk. Leiden: Research School CNWS, pp. 43–76. [Google Scholar]

- Genç, Mustafa, and Habib Kartaloğlu. 2022. Siyasî Bir Mühendislik Projesi Olarak Karşı Mihne Uygulamaları. Trabzon İlahiyat Dergisi 9: 167–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutas, Dimitri. 1999. Greek Thought Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early ‘Abbasid Society (2nd–4th/8th–10th Centuries). London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Donald R. 2016. Studies in Medieval Islamic Technology: From Philo to al-Jazari—from Alexandria to Diyar Bakr. Edited by David A. King. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hinds, Martin. 1993. Mihna. In The Encyclopaedia of Islam New Edition. Leiden and New York: Brill, vol. 7, pp. 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyland, Robert. 2004. ‘Theomnestus of Magnesia, Ḥunayn Ibn Ishaq, and the Beginnings of Islamic Veterinary Science’. In Islamic Reflections, Arabic Musings: Studies in Honour of Alan Jones. Edited by Robert Hoyland and Alan Jones. Cambridge: Gibb Memorial Trust, pp. 150–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hugonnard-Roche, Henri. 2007. Le Corpus Philosophique Syriaque Aux VIe–VIIe Siècles. In The Libraries of the Neoplatonists. Edited by Cristina D’Ancona. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 279–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ḥunayn b. Ishāq. 2005. Risālat ilā ‘Alī b. Yaḥyā. Tehran: Society for the Appreciation of Cultural Works and Dignitaries. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Abī Uṣaybi‘ah. 2024. ‘Uyūn al-Anbā fī Ṭabaqāt al-Aṭibbā: A Literary History of Medicine. Edited by Emilie Savage-Smith, Simon Swain and Geert Jan van Gelder. Translated by Emilie Savage-Smith, and Simon Swain. 5 vols. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Abī Uṣaybi‘ah, Abū al- ‘Abbās Aḥmad b. al-Qāsim. n.d. ‘Uyūn al-Anbā fī Ṭabaqāt al-Aṭibbā. Beirut: n.p.

- Ibn al-Nadīm, Abū al-Faraj Muḥammad Ibn Isḥāq. 2014. Kitāb al-Fihrist. 4 vols. London: al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn al-Qifṭī. n.d. Tārīkh al-Ḥukamā. 2 vols. Kuveyt: al-Maktabah Ibn Qutaybah.

- Ibn Juljul, Abū Ayyūb Sulaymān ibn Ḥassān. 1985. Ṭabaqāt al-Aṭibbā wal-Ḥukamā. Beirut: Muassasat al-Risāla. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Khallikān, Abū al-‘Abbās Shams al-Dīn Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr. 1968. Wafayāt al-A‘yān wa-Anbā Abnā al-Zamān. 8 vols. Beirut: Dār al-Thaqāfah. [Google Scholar]

- İhsanoğlu, Ekmeleddin. 2023. The Abbasid House of Wisdom: Between Myth and Reality. Abingdon: Oxon. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, Mahmut. 2002. ‘Kindî, Ya‘qūb b. İshak (Hayatı ve Şahsiyeti)’. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Ankara: TDV Yayınları, vol. 26, pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, Mahmut. 2018. Kindî: Felsefî Risâleler. İstanbul: Klasik Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- King, Daniel, ed. 2019. The Syriac World. London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Kırkpınar, Mahmut. 1996. Abbâsî Halifesi Mütevekkil ve Dönemi (232–247/847–861). Ph.D. thesis, Marmara Üniversitesi, İstanbul, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Lamoreaux, John C., and Grigory Kessel. 2016. Ḥunayn Ibn Isḥāq on His Galen Translations: A Parallel English-Arabic Text Edited and Translated By. Provo: Brigham Young University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mas‘ūdī, Abū al-Ḥasan ‘Alī b. al-Ḥusayn b. ‘Alī. 1988. Murūj al-Dhahab wa Ma‘ādin al-Jawhar. Edited by As‘ad Dāghir. 4 vols. Qom: Dār al-Hijrah. [Google Scholar]

- Mārī b. Sulaymān. 1899. Akhbāru Fatyārikati Kursiyy al-Mashriq. Roma: n.p. [Google Scholar]

- Melchert, Christopher. 1997. The Transformation of the Sunni Schools of Law, 9th–10th Centuries C. E. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Melchert, Christopher. 2019. Sünnî Düşüncenin Teşekkülü: Din, Yorum, Dindarlık. Translated by Ali Hakan Çavuşoğlu. Istanbul: Klasik Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhof, Max. 1926. New Light on Hunain Ibn Ishâq and His Period. Isis 8: 685–724. [Google Scholar]

- Muḥammad ’Ābid al-Jābirī. 2019. Arap-İslam Medeniyetinde Entelektüeller. Translated by Numan Konaklı. Istanbul: Mana Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, Levent. 2012. İslam toplumunda Hristiyanlar. İstanbul: Ensar Neşriyat. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, Levent. 2013. İslâm Tıp Tarihi Üzerine İncelemeler. İstanbul: Ensar Neşriyat. [Google Scholar]

- Pormann, Peter E., and Emilie Savage-Smith. 2007. Medieval Islamic Medicine. Washington, DC: Georgetown Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raiola, Tommaso. 2020. Galen’s Surgical Commentaries in Oribasius’ Collectiones Medicae: An Overview and Some Remarks. AION (Filol.) Annali Dell’Università Degli Studi Di Napoli “L’Orientale” 42: 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, Ulrich. 2017. The Late Ancient Background. In Philosophy in the Islamic World. Edited by Ulrich Rudolph, Peter Adamson and Rotraud Hansberger Hansberger. Translated by Rotraud Hansberger. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 29–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, Ulrich, Rotraud Hansberger, and Peter Adamson, eds. 2016. Philosophy in the Islamic World. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Sa’di, Lutfi M. 1934. ‘A Bio-Bibliographical Study of Ḥunayn Ibn Is-Haq al-Ibadi (Johannitius) (809–877 A.D.)’. Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine 2: 409–46. [Google Scholar]

- Saliba, George. 2004. Revisiting the Syriac Role in the Transmission of Greek Sciences into Arabic. Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies 4: 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, George. 2011. Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sezgin, Fuat. 1970. Geschichte Des Arabischen Schrifttums: Medizine, Pharmazie, Zoologie, Tierheilkunde BIS ca 430 H. In Geschichte Des Arabischen Schrifttums. Leiden: Brill, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sezgin, Fuat. 1974. Geschichte Des Arabischen Schrifttums: Mathematik BIS ca 430 H. In Geschichte Des Arabischen Schrifttums. Leiden: Brill, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Sezgin, Fuat. 1978. Geschichte Des Arabischen Schrifttums: Astronomie BIS ca 430 H. In Geschichte Des Arabischen Schrifttums. Leiden: Brill, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Sidoli, Nathan. 2023. Translations in the Mathematical Sciences. In Routledge Handbook on the Sciences in Islamicate Societies: Practices from the 2nd/8th to the 13th/19th Centuries. Edited by Sonja Brentjes. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ṣafadī, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn Khalīl b. Aybak b. ‘Abd Allāh. 2000. Al-Wāfī bi’l-Wafayāt. 29 vols. Beirut: n.p. [Google Scholar]

- Şahin, Eyüp. 2018. ‘Kindî ve Antik Yunan Felsefe Geleneği’. Diyanet İlmi Dergi 54: 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Şenel, Samet. 2021. Fetihten Bilime: Antik Bilimlerin İslam Dünyasına İntikali (651–750). İstanbul: Siyer Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Şenel, Samet. 2022. Halife Me’mûn’a Kadar İslâm Dünyasında Çeviri Faaliyetleri. Ph.D. thesis, Sakarya Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Sakarya, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Şenel, Samet, and Levent Öztürk. 2021. Abbâsî Halifesi Mu’tasım-Billâh Döneminde (218–227/833–842) Saraydaki Bilimsel Faaliyetler. Bilimname 1: 491–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şeşen, Ramazan. 1993. Câhiz. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: TDV Yayınları, vol. 7, pp. 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Toorawa, Shawkat M. 2005. Ibn Abī Ṭāhir Ṭayfūr and Arabic Writerly Culture: A Ninth-Century Bookman in Baghdad. London: RoutledgeCurzon. [Google Scholar]

- Treiger, Alexander. 2022. From al-Biṭrīq to Ḥunayn: Melkite and Nestorian Translators in Early ’Abbāsid Baghdad. Mediterranea. International Journal on the Transfer of Knowledge 7: 143–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ṭabarī, Abū Ja‘far Muḥammad b. Jarīr b. Yazīd al-Āmilī. 1967. Tārīkh al-Rusul wa-l-Mulūk wa Ṣilat Tārīkh al-Ṭabarī. 11 vols. Beirut: Dār al-Turāth. [Google Scholar]

- Vagelpohl, Uwe. 2018. ‘The User-Friendly Galen: Ḥunayn Ibn Isḥāq and the Adaptation of Greek Medicine for a New Audience’. In Greek Medical Literature and Its Readers. New York: Routledge, pp. 113–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vagelpohl, Uwe, and Ignacio Sánchez. 2022. ‘Why Do We Translate? Arabic Sources on Translation’. In Why Translate Science?: Documents from Antiquity to the 16th Century in the Historical West (Bactria to the Atlantic). Edited by Dimitri Gutas. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 254–376. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, John. 2004. Syriac Translators and Greek Philosophy in Early Abbasid Iraq. Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies 4: 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, John. 2021. Why Did Ḥunayn, the Master Translator into Arabic, Make Translations into Syriac? On the Purpose of the Syriac Translations of Ḥunayn and His Circle. In The Place to Go: Contexts of Learning in Baghdad, 750–1000 C.E. Edited by Jens Scheiner and Damien Janos. Berlin: Gerlach Press, pp. 363–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ya‘qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ. 1964. Tarīkh. 3 vols. Najaf: Maktabat al-Ḥaydarīyah. [Google Scholar]

- Ya‘qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ. 2019. Mushākalat al-Nās li-Zamānihim wa-mā Yaglibu ’alayhim fī Kull ‘Aṣr. Beirut: Jadawel. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, H. İ., Mahmut Cihat İzgi, Enes Ensar Erbay, and Samet Şenel. 2024. Studying early Islam in the third millennium: A bibliometric analysis. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11: 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Şenel, S. Science Expanding Amid Political Challenges: Translation Activities During the al-Mutawakkil ‘Alā’llāh Period (232–247 H/847–861 CE). Religions 2025, 16, 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16040430

Şenel S. Science Expanding Amid Political Challenges: Translation Activities During the al-Mutawakkil ‘Alā’llāh Period (232–247 H/847–861 CE). Religions. 2025; 16(4):430. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16040430

Chicago/Turabian StyleŞenel, Samet. 2025. "Science Expanding Amid Political Challenges: Translation Activities During the al-Mutawakkil ‘Alā’llāh Period (232–247 H/847–861 CE)" Religions 16, no. 4: 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16040430

APA StyleŞenel, S. (2025). Science Expanding Amid Political Challenges: Translation Activities During the al-Mutawakkil ‘Alā’llāh Period (232–247 H/847–861 CE). Religions, 16(4), 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16040430