Abstract

This study examines critical challenges associated with religious literacy in contemporary South Korea and educational approaches to address them. By analyzing data from the Religious Literacy Survey 2023 (n = 2022), we reveal that these paradoxical attitudes stem from a declining religious literacy, manifested as limited knowledge of religious traditions and their teachings. Amid the rise in the number of the religiously unaffiliated, our analysis indicates that this trend reflects not a rejection of religion but rather an urgent need for education to enhance religious literacy. Based on this analysis, we examine religious education curricula at Dongguk and Yonsei Universities as exemplars that not only deepen students’ understanding of specific religious traditions but also help them recognize religion’s enduring relevance in addressing contemporary societal challenges. Building on these cases, while recognizing their limitations as religiously affiliated institutions, we emphasize the need for an integrated educational approach to religious literacy—one that extends beyond specific traditions and incorporates religious studies examining various dimensions of religion itself. We further suggest the broader implementation of religious literacy education across higher education institutions. Such educational approaches provide insights into fostering social cohesion and meaningful interreligious engagement in South Korea and beyond.

1. Introduction

Religious literacy is often used to represent the ability to discern, understand, and engage with religious traditions and various religious phenomena that intersect broader social, historical, and cultural contexts through multiple lenses (Hannam et al. 2020). The concept has evolved significantly since Andrew Wright’s influential work, Religious Education in the Secondary School: Prospects for Religious Literacy, which connected religious literacy to religious education. Wright (1993) first defined religious literacy as the ability to understand and engage with religious phenomena in (an) informed way(s). This approach emphasizes active engagement with religious truth claims and their implications for understanding the transcendent realities that shape our ways of thinking and behavior in the world.

Building on Wright’s approach, many scholars in (but not limited to) the fields of religious studies and education have elaborated on the concept of religious literacy (e.g., Moore 2015; Prothero 2007). For instance, Prothero (2007) further developed this concept by focusing on its practical components, defining religious literacy as mastery of the basic elements of religious traditions—their terms, symbols, doctrines, practices, and narratives. He emphasized how this knowledge enables meaningful participation in civic life, particularly within religiously diverse societies. Moore (2007, 2015) synthesized and expanded these perspectives by suggesting that religious literacy includes both knowledge of religious traditions and the ability to analyze religious dimensions in political, social, and cultural contexts. Her definition highlights the importance of understanding how religion permeates and influences all dimensions of human experience, including contemporary social issues and cultural dynamics. While perspectives on religious literacy vary, they all have a shared point of view: this multifaceted ability allows people to discern how religion intersects with and influences various aspects of human life—from personal beliefs to public policy, from cultural expressions to social institutions. Religious literacy, therefore, is not merely about understanding religions but serves as a crucial competency for engaging with complex issues in which religious dynamics intersect with the social, political, and cultural landscape of society.

Recently, research on religious literacy has gained significant attention in South Korea’s religious studies communities, particularly through the works of MINDLAB, a non-profit research organization. MINDLAB’s research team1 conducted the Religious Literacy Survey in April to June 2023, and subsequently published a comprehensive five-volume series on religious literacy in March 2024. This surge in scholarly attention culminated in an academic conference held in June 2024, entitled “Religious Literacy and the Social Role of Religious Studies”, demonstrating the growing recognition of religious literacy as a critical area of inquiry within the field.2

Based on the data from the Religious Literacy Survey 2023, this study identifies current challenges regarding religious literacy in contemporary South Korea. The survey results reveal several significant issues we need to consider. One issue that emerges from the survey data concerns the paradoxical relationship between South Koreans’ acceptance of religious diversity and their approach to practical interreligious engagement. While the data show that over 79% of respondents expressed positive attitudes toward religion in general, demonstrating openness and respect for religious freedom, they simultaneously exhibited the ambivalent attitudes regarding personal interactions with individuals from other religious backgrounds. This tension highlights South Koreans’ complex attitudes toward other religions.

Given this point, we articulate that religion continues to influence contemporary South Korean society, albeit in more complex ways than traditionally perceived. One critical point emerging from the survey data is the paradoxical relationship between acceptance of religious diversity and practical interreligious engagement among South Koreans. This divergence between broad tolerance and personal hesitation highlights a critical gap in religious literacy, where general acknowledgement of religious diversity has yet to foster meaningful interreligious engagement.

Another issue identified in the survey data concerns the significant transformation of South Koreans’ engagement with institutional religions—the religiously unaffiliated population has increased significantly, rising from 47.1% in 2005 to 56.1% in 2015. This notable demographic shift reflects broader changes in the ways in which South Koreans perceive and engage with institutional religions.

One potential explanation regarding this transformation in religious demographics and the related issue of declining religious literacy stems from the advancement of science and the ongoing trend of secularization (Arthur 2006). This point is often supported by significant transformations in a number of countries, particularly in terms of the declining population of traditional religious affiliation. According to data and projections from the Pew Research Center (2015, 2022), the proportion of the religiously unaffiliated increased from 11.77% in 2007 to 16% in 2015. Their projections indicate that this trend will continue, with the religiously unaffiliated population expected to grow from 1.1 billion to 1.2 billion by 2050, most notably in developed regions.

However, this perspective raises a critical question: do these transformations represent an inevitable stage in societal progress? Put differently, do they indicate the emergence of a perception that religion is no longer necessary in contemporary life? The results of the Religious Literacy Survey 2023 challenge the potential explanation based solely on the advancement of science and the ongoing trend of secularization. The survey data suggest that the significant increase in the religiously unaffiliated population in South Korea does not indicate negative attitudes toward religion itself, but rather points to issues of religious literacy.

One primary purpose of surveys is to collect and analyze information about the characteristics, opinions, and behaviors of large populations. In line with this general principle, the Religious Literacy Survey 2023 was also designed and developed for practical applications, which means its findings carry significant implications for social implementation (Seong 2024a). In this study, we thus articulate that education serves as both a practical application of the survey findings and a key approach to address the challenges of religious literacy they reveal.

Aligned with the survey data and many scholarly works (e.g., Seong 2024a, 2024b; Gu and Kim 2024a, 2024b; Min 2020, 2024), this study proposes that education for enhancing religious literacy serves two essential functions: First, it enables people to deepen their understanding of various religious traditions (e.g., their teachings, doctrines, practices, etc.). Second, it promotes recognition of newly emerging religious perspectives by fostering public engagement with fundamental discourses that address contemporary social and cultural needs. By implementing educational approaches that develop these two functions and thereby enhance religious literacy, we suggest that this enhanced literacy can contribute to addressing the issues we identified. As Seong (2024a) demonstrates, religious education effectively improves understanding of religion at both individual and community levels. This point highlights the importance of educational programs for enhancing religious literacy. Religious education in South Korea, however, faces significant limitations. For example, religious education at the elementary and secondary levels in South Korea remains largely ineffective (Kim 2020), and even institutions for higher education offer extremely limited opportunities for students to study religions (Seong 2024a). In this context, Dongguk and Yonsei Universities, both renowned religiously affiliated private institutions, are exemplary cases of religious education in South Korea (Gu and Kim 2024a, 2024b; Min 2020, 2024). Therefore, this study examines these two universities as institutions with exemplary effective educational approaches for enhancing religious literacy to address the critical issues we identified.

To recapitulate, our analysis proceeds in three key stages: First, we explore the current state of religious literacy in South Korea through an extensive examination of the results of the Religious Literacy Survey 2023. Second, we investigate the ways in which religious education can effectively engage with the core aspects of religious traditions, beliefs, and practices within (but not limited to) the context of South Korea by drawing on the cases of Dongguk and Yonsei Universities. Third, we then highlight the point that education aimed at enhancing religious literacy emerges as crucial for broader social cohesion and interreligious engagement in (but not limited to) contemporary South Korean society.

2. Religious Literacy in South Korea: An Empirical Perspective

In this section, we analyze the results of the Religious Literacy Survey 2023 to explore the current state of religious literacy in South Korea. The survey provides valuable empirical data regarding how South Koreans perceive and engage with religious issues in contemporary society. With an in-depth analysis of these data, we aim to examine not only South Koreans’ general attitudes toward religion but also specific aspects of these that relate to the issue of religious literacy.

Our analysis in this section proceeds in three parts, where the examination of data (i.e., Section 2.2 and Section 2.3) covers different dimensions of the survey findings. First, we explore the concept of religious literacy, and provide an overview about the survey methodology in detail. Second, we analyze the paradoxical relationship between acceptance of religious diversity and practical interreligious engagement among South Koreans. Third, we examine the transformation of South Koreans’ engagement with institutional religions, which is entwined with the growing population of the religiously unaffiliated in South Korea.

2.1. Religious Literacy Survey 2023 in South Korea

As described, Wright (1993) first defined religious literacy as the ability to understand and engage with religious phenomena in (an) informed way(s). This approach emphasizes active engagement with religious truth claims and their implications for understanding the transcendent realities that shape our ways of thinking and behavior in the world.3,4 Indeed, religious literacy is not merely about understanding religions but serves as a crucial competency for engaging with complex issues in which religious dynamics intersect with the social, political, and cultural landscapes of society.

Recently, research on religious literacy has gained significant attention in South Korea’s religious studies communities as well. MINDLAB’s research team, in collaboration with Hankook Research, developed and conducted the Religious Literacy Survey 2023 (hereafter “the survey”) to examine South Koreans’ understanding of and attitudes toward religion. According to MINDLAB and Hankook Research (2023), the purpose of this survey is to assess various perceptions and levels of understanding regarding religion among Koreans, providing foundational data for analyzing religious perspectives in South Korea. This survey employed a structured data collection process, gathering responses from 2022 adults aged 18 and above through quota sampling stratified by gender, age, and regional distribution (see Table 1). The survey utilized a web-based questionnaire from 17 to 24 April 2023, with responses being measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The survey was designed to investigate a detailed set of demographic data and examine religious perspectives, including both personal beliefs and societal attitudes. The demographic section collected data on various demographic variables such as residence, gender, age, religious affiliation, education level, marital status, occupation, and monthly household income.

Table 1.

Overview of the Religious Literacy Survey 2023 (MINDLAB and Hankook Research 2023, p. 3).

The survey questionnaires consisted of two key domains: (a) universal religious literacy (42 items) and (b) religious tendencies (11 items). The first domain, universal religious literacy, explored four critical areas that focused on knowledge and understanding of religious traditions: (1) spiritual practice and life (Questions 1.1.–1.11., 11 items), (2) multi-religious coexistence (Questions 2.1.–2.11., 11 items), (3) attitudes toward religion (Questions 3.1.–3.9., 9 items), and (4) religious understanding (Questions 4.1.–4.11., 11 items). As its name indicates, the universal religious literacy domain assessed general understanding of religion and religious phenomena (Seong 2024a, p. 13). The survey examined meanings and roles of religion for individuals and communities, beginning with definitional aspects and measuring knowledge about various religions through 42 questions. Regarding this domain, Seong (2024a) explained that it was chosen not to examine specific elements constituting religious traditions such as doctrines, organizations, and rituals, in the survey, given that it represents a pioneering survey in South Korea. The survey also excluded in-depth knowledge about denominational differences, historical development of individual religions, and interreligious exchange history. Rather, the questionnaires in this domain primarily addressed social dimensions of religion, including relationships between religion and other social domains, religious significance in contemporary society, peaceful coexistence among religions, and religion’s influence on social integration or conflict.

The second key domain, religious tendencies, addressed personal beliefs and attitudes toward contemporary social issues through questions on (1) sexual ethics (Questions 5.1.–5.4., 4 items), (2) homosexuality (Questions 6.1.–6.5., 5 items), and (3) religiously motivated conscientious objection to military service (Questions 7.1.–7.2., 2 items). According to Seong (2024a), the second domain measured the ways individuals view various social issues based on their religious affiliation or differences in religious background. The questionnaires in this domain focused on verifying whether religion functions as a variable in perceiving prominent social issues. Through this approach, this domain attempted to assess both religion’s potential positive functions in addressing social conflicts and, conversely, ways that religion might amplify these conflicts.

The collected data were processed using SPSS, with demographic weights being applied based on the resident registration data from the Korean Ministry of the Interior and Safety (2023) in South Korea (MINDLAB and Hankook Research 2023). This weighting procedure ensured that the sample accurately reflected South Korea’s population distribution across regions, gender, and age groups (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of respondents (MINDLAB and Hankook Research 2023, p. 8).

As described, the results revealed significant contrasts in South Koreans’ attitudes toward religious freedom, diversity, and interreligious engagement. The results indicated a notable dichotomy between the broad acceptance of religious diversity and the hesitation toward practical engagement with it. The highest agreement rates emerged in questions relating to respect for freedom of religion and social coexistence, with 79.9% of respondents supporting religious freedom and 79.5% being willing to engage in social activities with people of different religions. However, this positive attitude did not lead to a willingness towards personal interreligious engagement. The data showed lower agreement rates in questions about direct interactions with other religious traditions. Only 20.6% of respondents expressed an interest in learning about other religions’ doctrines and rituals, and 23.9% indicated an openness to interreligious marriage. With this overview, we now turn to the details of the survey data and prominent patterns within them in the following section, so as to examine specific aspects of religious literacy in South Korea.

2.2. The Tension Between Acknowledgement of and Practical Engagement with Religious Differences

One critical point emerging from the survey data is the paradoxical relationship between acceptance of religious diversity and practical interreligious engagement among South Koreans. This dynamic manifests as a prominent contrast between broad societal recognition of religious differences and a hesitation toward personal interreligious interactions. This divergence indicates a critical gap between the general acknowledgement of religious plurality and practical engagement with religious differences, which creates a tension that might shape the ways in which South Koreans address religious issues in their daily lives.

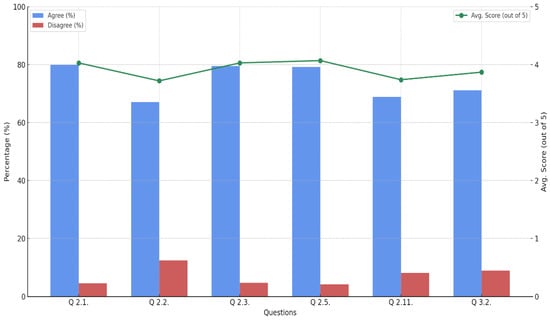

The survey data and response patterns offer substantial support regarding this critical gap. For instance, we first find substantial support for religious diversity at a societal level (see Table 3 and Figure 1). A significant majority of respondents (79.9%) affirmed their respect for religious freedom, and 71.1% of respondents endorsed the view that religious communities should be inclusive of other religious traditions. This general religious acknowledgement extended to the questions about social acceptance, with 79.5% of respondents expressing a willingness to engage in social activities with people of different religions. Moreover, respondents demonstrated strong support for religious autonomy, with 79.2% believing that religious communities should respect an individual’s choice of faith. The data also reveal broad recognition of religious values and familial respect, with 68.9% acknowledging each religion’s inherent value and 67.1% indicating respect for family members holding different religious beliefs. These high agreement rates, coupled with relatively low disagreement rates, suggest a general acknowledgement of religious plurality in both public and familial spheres across South Korea.

Table 3.

Results for religious acknowledgment and social acceptance.

Table 3.

Results for religious acknowledgment and social acceptance.

| Question Number5 | Question | Agreement (%)6 | Disagreement (%)7 | Average Score (Out of 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q. 2.1. | I respect freedom of religion (faith) | 79.9 | 4.6 | 4.03 |

| Q. 2.2. | I respect my family members who hold different religious beliefs | 67.1 | 12.4 | 3.72 |

| Q. 2.3. | I can engage in social activities (e.g., work and social organizations) with people of different religions | 79.5 | 4.8 | 4.03 |

| Q. 2.5. | I think religious communities should respect individual’s choice of faith | 79.2 | 4.2 | 4.07 |

| Q. 2.11. | I think each religion has its own inherent value | 68.9 | 8.1 | 3.74 |

| Q. 3.2. | I think all religions should be inclusive of other religious traditions | 71.1 | 8.9 | 3.87 |

Figure 1.

Results for religious acknowledgment and social acceptance.

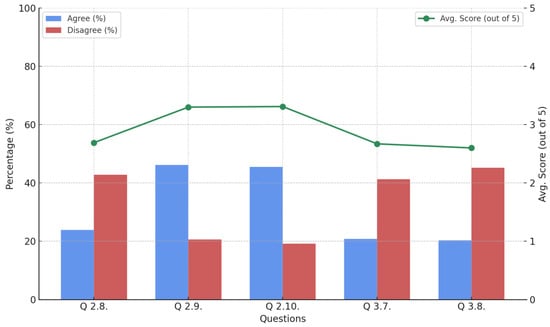

However, when it comes to practical engagement with religious differences, we find patterns that differ from those related to general acknowledgment described above (see Table 4 and Figure 2). When asked about accepting their children’s choice of different religions, 46.2% of respondents expressed agreement, while 20.6% disagreed. Similarly, 45.5% showed acceptance of a son-in-law or daughter-in-law of a different religion, with 19.1% expressing disagreement. These data indicate a contrast from the responses to Q. 2.2 in Table 3, where 67.1% of respondents expressed respect for family members who hold different religious beliefs. Furthermore, the acceptance rate dropped sharply for marital relationships. Only 23.9% of respondents indicated willingness to accept a devout member of another religion as a spouse, while 42.8% explicitly rejected this possibility. This notable decline points to marital relationships as a challenging area for interreligious acceptance in the context of South Korea. While this decline clearly demonstrates the significant pattern, the data per se do not provide sufficient explanation for this lower acceptance of interreligious marriage compared to other family relationships. As these data illustrate, practical engagement with religious differences reveals different aspects from general acknowledgment we noted above. We suggest that explicating these differing aspects would require further in-depth studies with diverse research approaches.

Table 4.

Results for engagement with religious differences.

Table 4.

Results for engagement with religious differences.

| Question Number | Question | Agreement (%) | Disagreement (%) | Average Score (Out of 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q. 2.8. | I can accept a devout member of another religion as a spouse | 23.9 | 42.8 | 2.69 |

| Q. 2.9. | I can accept if my children choose a different religion than mine | 46.2 | 20.6 | 3.3 |

| Q. 2.10. | I can accept a son-in-law or daughter-in-law of a different religion | 45.5 | 19.1 | 3.31 |

| Q. 3.7. | I am interested in the doctrines and rituals of other religions | 20.6 | 41.3 | 2.67 |

| Q. 3.8. | I am willing to learn about other religions’ doctrines and rituals when given the opportunity | 20.3 | 45.2 | 2.60 |

Figure 2.

Results for engagement with religious differences.

In this study, we pay attention to religious literacy as one of these research approaches. The significant gap between general acceptance and practical interaction with religious difference suggests an unfamiliarity with different religious traditions as a factor that might shape these ambivalent attitudes. The data show that 20.6% of respondents expressed interest in the doctrines and rituals of other religions, while 20.3% indicated willingness to learn about other religions’ doctrines and rituals when given the opportunity. These relatively low rates of interest and engagement with learning other religions also stand in contrast to the broader acceptance of religious diversity we noted earlier.

Nevertheless, it is also important to acknowledge that the data regarding interest in learning about other religions’ doctrines and rituals might be interpreted from differing perspectives. For instance, one might argue that individuals who understand their deep religious significance may actually be reluctant to participate in other religions’ rituals. From this perspective, individuals with profound religious knowledge might feel more hesitant to engage in religious practices outside their faith, considering it offensive to their hosts to engage without the attendant meaning.

This interpretation, however, might not fully capture the South Korean context, despite its validity. The survey data show that 71.1% of respondents agreed that “all religions should be inclusive of other religious traditions” (Q. 3.2.). This result indicates that religious inclusivity is widely accepted as a commonsense in South Korea as a multi-religious society. Not only do the survey data support this point, but many South Koreans also seem to actually practice such inclusivity in their daily lives. One prominent example of this inclusivity is the widespread acceptance and integration of diverse religious practices into cultural events regardless of individuals’ differing faith backgrounds. Yeondeunghoe, the Lantern Lighting Festival (Kor. 연등회; Chi. 燃燈會), stands as a notable example of such inclusivity. Originated from a Buddhist celebration commemorating the birth of Buddha, the festival is now widely participated in by numerous South Koreans as a cultural event (see Figure 3). As UNESCO describes, the festival “takes place throughout the Republic of Korea. As the eighth day of the fourth lunar month (Buddha’s birthday) approaches, the entire country lights up with colourful lanterns” (UNESCO 2020, n.p.). The festival involves diverse participants including temples, local communities, and various cultural organizations who come together to celebrate this tradition. Designated as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity and Korea’s National Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2020, the Lantern Lighting Festival exemplifies a shared practice in South Korea.

Figure 3.

The Lantern Lighting Festival parade held in Seoul, 26 April 2025 (Yeondeunghoe Safeguarding Association 2025).

These points underscore the paradoxical relationship we identified earlier: while South Koreans demonstrate support for religious inclusivity and practice this commonsense in their cultural contexts, the survey data are paradoxical. This inconsistency, often revealed by the ambivalent attitudes toward interreligious interactions, we thus suggest, stems from limited familiarity with religious knowledge.

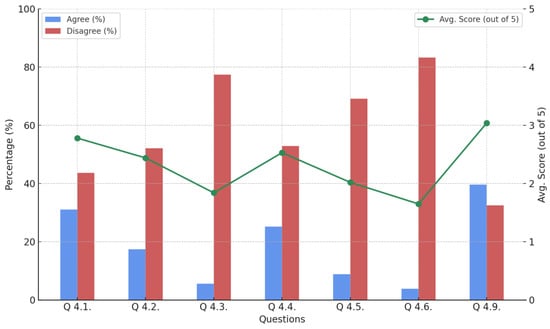

In other words, the lack of basic religious knowledge (e.g., the teachings, doctrines, and practices of religious traditions) creates significant barriers to meaningful interreligious engagement, as unfamiliarity often leads to uncertainty and hesitation about potential interactions. Therefore, despite their strong support for religious freedom and diversity, most South Koreans’ limited religious knowledge continues to hinder meaningful interreligious engagement. The empirical data clearly support this point, as they reveal strikingly low levels of familiarity with major religious traditions (see Table 5 and Figure 4).

Table 5.

Results for knowledge of religious teachings and traditions.

Table 5.

Results for knowledge of religious teachings and traditions.

| Question Number | Question | Agreement (%) | Disagreement (%) | Average Score (Out of 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q. 4.1. | I can explain the main teachings of Jesus | 31.1 | 43.7 | 2.78 |

| Q. 4.2. | I can explain the main teachings of Buddha | 17.4 | 52.1 | 2.44 |

| Q. 4.3. | I can explain the main teachings of Muhammad | 5.6 | 77.4 | 1.84 |

| Q. 4.4. | I can explain the basic content of the Old and New Testaments | 25.2 | 52.9 | 2.53 |

| Q. 4.5. | I can explain the basic differences between early Buddhism and Mahāyāna Buddhism | 8.9 | 69.1 | 2.02 |

| Q. 4.6. | I can explain the basic content of the Quran | 3.9 | 83.3 | 1.65 |

| Q. 4.9. | I can explain the difference between Catholicism and Protestantism | 39.6 | 32.5 | 3.04 |

Figure 4.

Results for knowledge of religious teachings and traditions.

For instance, when asked about their ability to explain core religious teachings, 31.1% of respondents felt confident explaining Jesus’s main teachings, and fewer (17.4%) could explain Buddha’s primary teachings. This lack of knowledge became more evident regarding Islam, with merely 5.6% of respondents being able to explain Muhammad’s main teachings. The limited understanding of various religious traditions extended to sacred texts and denominational differences as well. A total of 25.2% of respondents indicated that they could explain the basic contents of the Old and New Testaments, and a mere 3.9% felt capable of explaining the basic contents of the Quran. The data also revealed a limited understanding of differences between religions: 39.6% of respondents could explain the difference between Catholicism and Protestantism, but only 8.9% could explain the differences between early Buddhism and Mahāyāna Buddhism.

Given the variations in religious knowledge levels revealed in the data, we suggest that such differences might correlate with the proportion of religiously affiliated educational institutions in South Korea. According to Gu and Kim (2024a, 2024b), private institutions constitute 87.8% of all higher education institutions in South Korea, with religiously affiliated ones accounting for a substantial portion. Among these religiously affiliated institutions, the majority are affiliated with Christian organizations, followed by those of Buddhism and Confucianism, while there are no Islamic-affiliated educational institutions. This institutional distribution might help explain South Koreans’ relatively higher familiarity with Christian teachings (31.1%) compared to Buddhist teachings (17.4%) and the significantly lower knowledge of Islamic teachings (5.6%). In this sense, the variations in religious knowledge levels seem to have a correlation with the proportion of religiously affiliated institutions in South Korea, given the institutional numbers following a descending order (i.e., Christianity-Buddhism-Islam) corresponding to the data pattern. However, it is also important to note that religion is addressed in extremely limited ways within national and official curricula from elementary to higher education despite the presence of these religiously affiliated institutions (Kim 2020; Seong 2024a).

All these points thus help explain the pattern revealed in the data we described—a significant divergence between general support for religious diversity and actual interreligious engagement in practice. The limited understanding of various religious traditions creates substantial barriers to interaction, making interfaith encounters more challenging for many South Koreans. Religious literacy thus emerges as a crucial bridge between general acknowledgement of religious diversity and meaningful interreligious engagement in contemporary South Korean society. In this context, education aimed at enhancing religious literacy becomes essential for fostering actual interreligious engagement as well as broader social cohesion in contemporary South Korean society.

2.3. The Religiously Unaffiliated and Religious Literacy

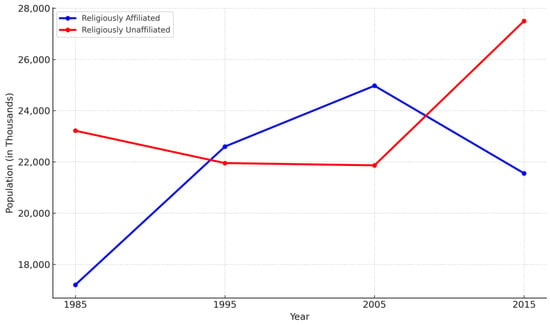

Another critical point emerging from the survey data concerns the transformation of South Koreans’ engagement with institutional religions. The survey results, aligned with demographic trends from census data (Statistics Korea 2016), indicate significant shifts in how South Koreans affiliate with institutional religions. The census data from 1985 to 2015 provide substantial support for this transformation (see Table 6 and Figure 5). After reaching its peak at 53% in 2005, the proportion of religiously affiliated individuals in South Korea decreased to 43.9% in 2015—a comparable level to that of 1985 (42.6%).

Table 6.

Religious population from census data, 1985–2015 (Statistics Korea 2016)8 (units: thousands; percentages of total population).

Table 6.

Religious population from census data, 1985–2015 (Statistics Korea 2016)8 (units: thousands; percentages of total population).

| Category | 1985 | 1995 | 2005 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 40,420 | 44,553 | 47,041 | 49,052 |

| Religiously Affiliated | 17,203 (42.6) | 22,598 (50.4) | 24,971 (53.0) | 21,554 (43.9) |

| Buddhism | 8060 (19.9) | 10,321 (23.2) | 10,726 (22.8) | 7619 (15.5) |

| Protestant Christianity | 6489 (16.1) | 8760 (19.6) | 8616 (18.3) | 9676 (19.7) |

| Roman Catholicism | 1865 (4.6) | 2950 (6.6) | 5146 (10.9) | 3890 (7.9) |

| Won Buddhism | 92 (0.2) | 87 (0.2) | 130 (0.3) | 84 (0.2) |

| Confucianism | 483 (1.2) | 210 (0.5) | 105 (0.2) | 76 (0.2) |

| Others | 212 (0.5) | 268 (0.6) | 247 (0.5) | 208 (0.4) |

| Religiously Unaffiliated | 23,216 (57.4) | 21,953 (49.2) | 21,865 (46.5) | 27,499 (56.1) |

Figure 5.

Trends in religiously affiliated and unaffiliated populations (Statistics Korea 2016).

What is noteworthy in these census data is the significant increase in the religiously unaffiliated population, rising from 46.5% in 2005 to 56.1% in 2015. This notable demographic shift reflects broader changes in the ways in which South Koreans perceive and engage with institutional religions. This transformation aligns with recent scholarly works regarding the religiously unaffiliated population in South Korea (e.g., Lim and Chong 2017; Chong 2019; Lim 2019). In other words, this trend suggests not a diminishing interest in religion per se, but rather an increasing disengagement from institutional forms of religious practice.

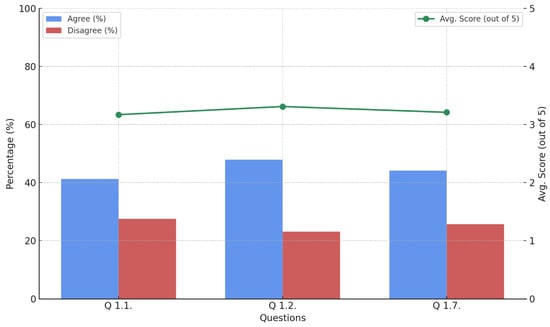

At the core of this disengagement lies South Koreans’ prevalent perception that the practices, teachings, and guidance that are offered by institutional religions are becoming less relevant to their daily lives. We suggest that the survey data support this perception, indicating relatively low rates of agreement regarding religious life’s role and impact in daily life (see Table 7 and Figure 6): when asked about the practical impact of religious life, only 41.3% of respondents believed that religious faith plays an important role in life, and just 44.1% thought that religion can contribute positively to family relationships. Similarly, regarding the value of religious practices, less than half of respondents (47.9%) believed that spiritual practices (e.g., prayer, meditation, etc.) offer meaning in life.

Table 7.

Results on perceptions of religious life’s role and impact in daily life.

Table 7.

Results on perceptions of religious life’s role and impact in daily life.

| Question Number | Question | Agreement (%) | Disagreement (%) | Average Score (Out of 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q. 1.1. | I believe religious faith plays an important role in life | 41.3 | 27.5 | 3.17 |

| Q. 1.2. | I think spiritual practices like prayer or meditation offer meaning to life | 47.9 | 23.1 | 3.31 |

| Q. 1.7. | I believe religion can contribute positively to family relationships | 44.1 | 25.7 | 3.21 |

Figure 6.

Results on perceptions of religious life’s role and impact.

A significant factor in this pattern of disengagement stems from the structural limitations of religious institutions in South Korea. While these institutions concentrate heavily on expanding their membership and spreading their religious teachings, they pay insufficient attention to educating people about the fundamental roles and values of religions in contemporary society. For instance, in the current context of South Korea, religious institutions often overlook their crucial educational responsibility to demonstrate how religion engages with and contributes to addressing contemporary social challenges. This type of religious education, as we examined elsewhere (Gu and Kim 2024a, 2024b), is instead undertaken by religiously affiliated educational institutions. This fact underscores the results discussed above, highlighting South Koreans’ limited knowledge of religious traditions.

Despite their limited religious knowledge and disengagement from institutional religions, South Koreans continue to grapple with profound existential uncertainties such as death and the afterlife—the fundamental questions that religious traditions have addressed since their beginning. These existential concerns create a deep anxiety that persists in our contemporary world, even amid unprecedented scientific and technological progress. Such fundamental questions about human existence permeate all aspects of human life—from personal beliefs to public policy, from cultural expressions to social institutions—in ways that science and technology cannot fully address. In this sense, South Koreans still recognize religion’s essential role in contemporary society, especially in helping people address these fundamental uncertainties about human existence.

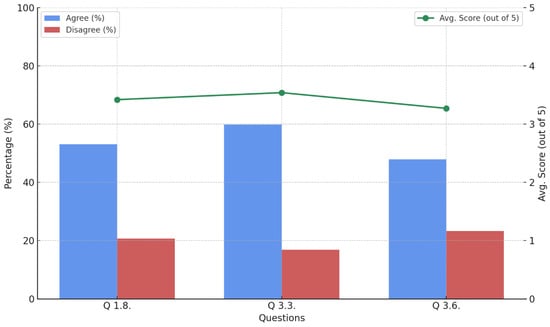

Nevertheless, while acknowledging this essential role, South Koreans perceive that religion’s engagement in contemporary society requires an evolution that resonates with ongoing social and cultural changes. The decreasing interest in institutional religions in South Korea, in that sense, can be attributed to their failure to adequately fulfill that essential role in ways that remain relevant and viable for contemporary societal needs. The survey data strongly support this dual perception among South Koreans regarding the role of religion and the need for adaptation (see Table 8 and Figure 7): 53.1% of respondents agreed that religion helps overcome the fear of death, affirming its role in addressing existential questions. The data also reveal that 59.8% believed that religious doctrine should change in accordance with social change, and 47.9% of respondents indicated that religious truths change according to the times.

Table 8.

Results of South Koreans’ perceptions of religion’s role and the need for adaptation.

Table 8.

Results of South Koreans’ perceptions of religion’s role and the need for adaptation.

| Question Number | Question | Agreement (%) | Disagreement (%) | Average Score (Out of 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q. 1.8. | I think religion helps overcome the fear of death | 53.1 | 20.7 | 3.42 |

| Q. 3.3. | I think religious doctrine should change in accordance with social change | 59.8 | 16.8 | 3.54 |

| Q. 3.6. | I think religious truths change according to the times | 47.9 | 23.3 | 3.27 |

Figure 7.

Results on perceptions of religion’s role and the need for adaptation.

Given this dual perception seen in the survey data, the significant increase in the religiously unaffiliated population in South Korea does not indicate negative attitudes toward religion itself. Rather, South Koreans continue to recognize religion’s enduring necessity in their lives, especially for addressing existential concerns. However, institutional religions have largely failed to fulfill this essential role by not adequately addressing these existential concerns in ways that respond to social and cultural changes, leading to South Koreans’ diminishing interest in religion. The positive response rates regarding religion’s role and its need for adaptation demonstrate this recognition, while highlighting South Koreans’ expectation that religion must adapt to engage effectively with changing social and cultural contexts.

This perspective finds substantial support in the fact that religious rituals remain deeply embedded in contemporary South Korean society. Sasipgujae (Kor. 사십구재; Chi. 四十九齋), a Buddhist funeral rite that is widely practiced in South Korea, offers one prominent example of this support (Gu 2023). While developed within the Buddhist tradition and performed in its temples, Sasipgujae is generally accepted by South Koreans, regardless of their religious background. The ritual seems to extend beyond individual religious practice, as illustrated by its performance for victims of social tragedies such as the Sewol Ferry disaster in 2014. This type of persistent engagement with religious rituals indicates its broader social and cultural functions, demonstrating the ways in which religion maintains its relevance in contemporary South Korean society through its adaptation to social and cultural needs.

Considering these findings, the growing religiously unaffiliated population in South Korea requires careful consideration. The survey data indicate that the significant increase in the religiously unaffiliated population in South Korea does not indicate negative attitudes toward religion per se. Instead, they highlight issues with religious literacy. The data challenge the potential explanation grounded solely on the advancement of science and the ongoing trend of secularization.9 Our analysis thus suggests that while South Koreans seem to demonstrate a gradual shift away from institutional religions, this pattern does not indicate a rejection of religious or spiritual concerns.10

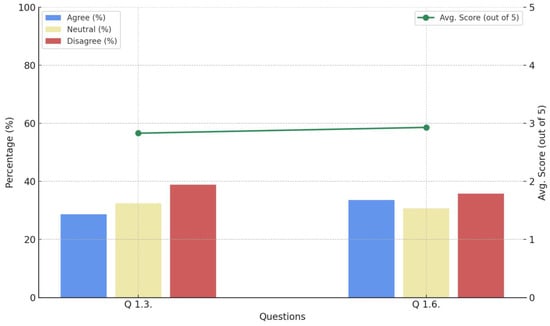

In this context, the survey data provide valuable insights into the critical role of religious literacy (see Table 9 and Figure 8): when asked about spiritual and existential issues, 28.7% of respondents believed that spiritual life holds more value than material life, with 32.4% remaining neutral on this question. Similarly, 33.6% of respondents believed that the afterlife and the present world are related, with 30.7% expressing a neutral perspective on this issue (see Table 8). In other words, South Koreans are not excessively materialistic in their worldview, while at the same time holding skeptical or ambivalent attitudes towards non-scientific knowledge. This pattern reveals a critical insight: not only does it highlight the ongoing significance of metaphysical discourse as a fundamental function that religious traditions have historically addressed, but it also underscores the crucial need to enhance religious literacy, thus enabling deeper public engagement with these fundamental discourses in contemporary society.

Table 9.

Results on perceptions of spiritual and existential issues.

Table 9.

Results on perceptions of spiritual and existential issues.

| Question Number | Question | Agreement (%) | Neutral (%) | Disagreement (%) | Average Score (Out of 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q. 1.3 | I believe spiritual life holds more value than material life | 28.7 | 32.4 | 38.9 | 2.83 |

| Q. 1.6 | I believe a connection exists between the afterlife and the present world | 33.6 | 30.7 | 35.8 | 2.93 |

Figure 8.

Results on perceptions of spiritual and existential issues.

Overall, a critical point emerges from our in-depth analysis of the survey data: not only does religion need to pursue interreligious engagement, but it must also engage with metaphysical and ideological questions in the context of contemporary society. Given these crucial roles that are held by religion, we articulate that education with the aim of enhancing religious literacy serves two essential functions: First, it enables people to deepen their understanding of various religious traditions (e.g., their teachings, doctrines, practices, etc.). Second, it promotes recognition of newly emerging religious perspectives by fostering public engagement with fundamental metaphysical and ideological discourses that address contemporary social and cultural needs. These educational functions, we argue, help address South Koreans’ religious challenges by strengthening both religion’s fundamental roles and its positive influence in contemporary society.

From this perspective, we now turn to the cases of Dongguk and Yonsei Universities as exemplars of curricula enhancing religious literacy to serve these essential functions. By examining their educational approaches and their alignment with our in-depth analysis, we demonstrate how education that aims to enhance religious literacy emerges as a crucial factor in broader social cohesion and interreligious engagement in (but not limited to) the context of South Korea.

3. Religious Education Enhancing Religious Literacy: The Cases of Dongguk and Yonsei Universities

As described, this section examines the cases of Dongguk and Yonsei Universities as exemplars of education that enhances religious literacy by exploring their religious education courses. The section pays close attention to the ways in which these courses foster the two essential functions of religious literacy in contemporary society. In doing so, we illustrate how their educational approaches address the critical challenges relating to religious literacy that were revealed in our previous analysis.

3.1. The Case of Dongguk University: Buddhism and Human Beings and Practice in Seon

Dongguk University, as an institution that is religiously affiliated with The Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism (Kor. 대한불교조계종; Chi. 大韓佛敎曹溪宗), has maintained two mandatory courses for religious education: Buddhism and Human Beings and Practice in Seon. These courses have served as essential components of the general education curriculum since 1996. With these courses, the university provides religious education to all students each semester, primarily focusing on first-year students, for whom these foundational courses represent their initial engagement with the institution’s religious education framework (The Founding Committee for Development of Dongguk University 2024). In recent years, these mandatory courses have required critical revisions to address several challenges in their educational implementation. A primary concern emerged regarding inconsistencies in the course delivery, as the content varied substantially depending on the instructor. Some classes, for instance, relied on outdated materials and terminology that students found difficult to engage with, which often reinforced students’ perception of Buddhism as inaccessible (Gu and Kim 2024a). To address these challenges, the university reformed its educational approach by establishing unified guidelines for these courses through standardized contents, teaching methods and materials, and assessment criteria (Kwon et al. 2024). In doing so, the university aimed to enhance their religious education framework to make religion more accessible to their students.

First, Buddhism and Human Beings (2 credits) is a course that introduces students to Buddhism and its teachings, helping them understand Buddhism as a religion and its deep relevance to contemporary life. This course consists of 15 weekly sessions that progress from foundational Buddhist concepts (e.g., the Four Noble Truths, karma and rebirth, etc.) and their historical development to their applications in contemporary society (see Table 10). At its core, this course emphasizes Buddhist doctrines and perspectives that illuminate human challenges, including the nature of suffering and paths to a meaningful life. Furthermore, the course relates these doctrines to contemporary issues such as human rights, climate change, and artificial intelligence to demonstrate how religious teachings can provide insights into current societal needs. Through this approach, the course not only helps students learn Buddhist teachings and perspectives but also makes them accessible in their daily lives.

Table 10.

The course description for Buddhism and Human Beings (Gu and Kim 2024a, p. 10).

Second, Practice in Seon is another course that introduces students to Buddhist meditations through a pedagogical approach for experiential learning. This is a year-long course, therefore spanning two semesters (1 credit per semester), with each semester consisting of 15 weekly sessions that guide students through various meditation practices and techniques. The sessions progress from fundamental meditation methods (e.g., breathing and walking meditations) to advanced meditative practices, including Ganwhaseon (see Table 11). Rather than emphasizing doctrinal aspects related to Buddhism per se, this course focuses on practical engagement with meditation in temple spaces within the university campus. The course employs a pass/fail grading system without examinations, allowing students to concentrate on their meditative practice and personal development. Through regular practice sessions in these dedicated spaces, students develop mental resilience and self-awareness while learning to integrate mindfulness into their daily routines. With this distinct pedagogical approach, this course especially aims to foster students’ ability to understand themselves and manage the various challenges that they encounter in contemporary life (Gu and Kim 2024a; Kwon et al. 2024).

Table 11.

The course description for Practice in Seon 1 (Gu and Kim 2024a, p. 9).

Given our analysis of religious literacy in South Korea, the religious education in Dongguk University effectively addresses key challenges in contemporary South Korean society while serving two essential functions: (a) deepening students’ understanding of religious traditions (e.g., their teachings, doctrines, practices, etc.) and (b) promoting recognition of newly emerging religious perspectives through engagement with fundamental metaphysical and ideological discourses that address contemporary social and cultural needs. With its two mandatory courses, the university has developed an integrated approach for religious education that combines the foundational teachings of Buddhism with practical engagement through various practices, including meditations. This educational approach serves to enhance religious literacy in two crucial ways: not only does it enable students to gain an in-depth understanding of Buddhist teachings and practices, it also helps them recognize the ways in which Buddhist perspectives can meaningfully engage with contemporary social and cultural needs.

More specifically, the course Buddhism and Human Beings directly addresses the limited knowledge of Buddhism that was demonstrated in the survey data. Through its coverage of basic Buddhist concepts and their historical development, the course helps students understand Buddhist teachings and doctrines that are embedded within their historical and cultural contexts in South Korea. Furthermore, the course extends beyond doctrinal knowledge of Buddhism to demonstrate its contemporary relevance through sessions examining current societal challenges such as human rights, climate change, and artificial intelligence. In doing so, the course illustrates the ways in which Buddhist teachings can meaningfully engage with contemporary social and cultural concerns. Not only does this approach make Buddhism more relevant to students’ daily lives, it also responds to the critical issue that we previously identified—religion’s inadequate adaptation to contemporary social and cultural needs.

Relatedly but distinctively, Practice in Seon offers direct experiential engagement with Buddhist meditative practices, addressing this critical issue in a different way. While Buddhism and Human Beings addresses this challenge by fostering an in-depth understanding of Buddhist teachings and doctrines, this course focuses specifically on religious practices through guided meditation sessions in dedicated temple spaces. Through its pedagogical approach of experiential learning, Practice in Seon helps students enhance their understanding of Buddhism beyond doctrinal knowledge, enabling them to experience how religious practices can be integrated into their daily lives and influence them in positive ways. In doing so, the course fulfills two essential functions of religious literacy: not only does it help students develop an in-depth understanding of Buddhist traditions through direct engagement with their practices, but it also enables students to recognize the ways in which religion can offer effective pathways to address emerging contemporary needs relating to deep existential concerns—from managing immediate personal challenges in one’s daily life (e.g., daily stress, anxiety, etc.) to addressing uncertainties about human existence (e.g., the nature of suffering, paths to a meaningful life, etc.). As our previous analysis revealed, these concerns are intrinsically linked with fundamental metaphysical and ideological questions and continue to shape people’s lives, despite unprecedented scientific and technological progress. Practice in Seon, in that context, enables students to understand how religious practices effectively address both immediate challenges and deeper existential questions in contemporary society, while retaining their essential principles.

Overall, through these two complementary courses, religious education in Dongguk University demonstrates an effective educational (and pedagogical) approach to enhancing religious literacy in contemporary South Korean society. While Buddhism and Human Beings provides students with an in-depth understanding of Buddhist traditions and their contemporary relevance, Practice in Seon offers experiential engagement with Buddhist meditative practices, helping students integrate religious practices into their daily lives. Not only does this integrated educational approach address the critical challenges that we identified regarding religious literacy, but it also demonstrates how religious education can address two functions of religious literacy in ways that respond to contemporary societal needs in (but not limited to) South Korea.

3.2. The Case of Yonsei University: Understanding Christianity

Yonsei University, as one of the oldest and most renowned private institutions affiliated with Protestant denominations, has developed its religious education framework by integrating Christianity with a mandatory common curriculum for general education. This integration manifests primarily through the section Understanding Christianity, which consists of three different courses: Bible and Christianity, Christianity and World Culture, and Modern World and Christianity. As a crucial part of the common curriculum at this university, students must complete at least one of these courses (3 credits) for graduation. These courses have evolved significantly since their beginning, particularly after the establishment of the University College in 1999, which took responsibility for managing the general education curriculum. This organizational change led the university to approach religious education by situating Christianity within broader academic and cultural contexts (Min 2024). While their specific objectives, topics, and contents vary by instructor, these interrelated courses all aim to provide students with an in-depth understanding of Christian perspectives and their constitutive values.

First, Bible and Christianity is a course that provides students with an in-depth understanding of Christianity through biblical texts and their historical development. The course explores the central teachings of Christianity by examining the Bible’s formation, transmission, and interpretation, alongside Jesus’s life and ministry, while considering their ongoing development and implications for contemporary society (see Table 12). Through this extensive study of Christian doctrines and their principles, students engage with both historical contexts and contemporary interpretations of Christian teachings, particularly as they relate to the context of South Korean society. In doing so, this course enables students to develop an in-depth understanding of Christian perspectives and virtues, as well as to recognize their deep relevance in their daily lives.

Table 12.

A description of one of the Bible and Christianity courses held in 2024 (Gu and Kim 2024b, p. 8).

On the other hand, the courses Christianity and World Culture and Modern World and Christianity both examine Christianity’s engagement with contemporary society, with each offering (a) distinctive way(s) of engaging with this relationship. Christianity and World Culture, for instance, provides an in-depth exploration of how Christianity has both influenced and been shaped by diverse world cultures throughout history and in contemporary society. Through an extensive examination of the historical development of Christianity, this course explores the ways in which Christian beliefs and practices have adapted to different political, social, and cultural contexts across the globe, with particular emphasis on its encounters with other religious traditions. By doing so, the course investigates these complex interactions to demonstrate the ways in which Christian teachings and practices have been reconciled within various local cultural traditions, shaping diverse forms and expressions of Christianity in contemporary society. Meanwhile, Modern World and Christianity delves deeper into Christianity’s manifestation and relevance in contemporary society. To do so, this course explores the ways in which biblical meanings and Christian perspectives can address current social, political, and ethical challenges. The course critically examines fundamental questions of human existence through Christian perspectives, especially within the context of rapid globalization alongside the advancement of science and technology. Through engagement with contemporary issues such as climate change, refugee crises, and extreme nationalism, the course enables students to examine societal issues using Christian perspectives and values (see Table 13).

Table 13.

A description of one of the Modern World and Christianity courses held in 2024 (Gu and Kim 2024b, p. 7).

Similarly to the previously examined case of Dongguk University, Yonsei University also offers an integrative educational approach to enhance students’ religious literacy. Through its mandatory common curriculum, which is centered on Christianity and consists of three interconnected courses (i.e., Bible and Christianity, Christianity and World Culture, and Modern World and Christianity), the university provides a religious education framework that enables students to explore Christianity from various perspectives—including its relationship with other religious traditions, its religious function in addressing fundamental ideological questions of human existence, and its adaptation to contemporary social and cultural needs. This framework thus serves two essential functions to develop students’ religious literacy: (a) deepening their understanding of Christian traditions through an extensive examination of Christian texts and doctrinal principles alongside their historical development and (b) fostering their recognition of the ways in which Christian teachings can engage meaningfully with emerging social and cultural needs in contemporary society.

More specifically, the course Bible and Christianity helps students increase their religious knowledge by providing an in-depth examination of Christian traditions. By employing multiple analytical approaches, this course offers an educational opportunity to explore biblical texts not merely as religious documents but as significant works in human history. This critical engagement with religious texts and Christian traditions deepens students’ understanding of Christian doctrines and teachings within broader cultural, philosophical, and political contexts (Min 2020, 2024). In doing so, the course enables students to engage with both historical contexts and contemporary interpretations of Christian teachings, as they relate to the current South Korean society. This course, in that sense, helps students address the critical issue that we previously identified: the lack of substantive knowledge of religious traditions and their core teachings, which often prevents meaningful engagement with religion in contemporary society.

Furthermore, the courses Christianity and World Culture and Modern World and Christianity enhance students’ religious literacy by providing diverse perspectives on Christianity’s relationship with our society. By exploring Christianity’s interactions with different cultural (and religious) traditions and contemporary issues (e.g., climate change, refugee crises, extreme nationalism, etc.), these courses enable students to recognize the ways in which religious perspectives continue to address timeless fundamental questions of human existence, as well as religion’s enduring relevance in contemporary society. For instance, when examining Christian traditions’ historical development and their ongoing engagement with contemporary challenges, students learn two essential aspects to develop their religious literacy: (a) Christian teachings that address metaphysical and ideological discourses relating to deep existential uncertainties (e.g., life, death, afterlife) and (b) the ways in which religious traditions adapt to and engage with current societal challenges while preserving their essential principles and values.

Taken together, Yonsei University also demonstrates an effective approach to enhancing religious literacy in contemporary South Korean society. Through its integrative educational framework based on a mandatory common curriculum that is centered on Christianity, the university enables students to develop their religious knowledge while recognizing the enduring significance of Christianity in contemporary life. This integrative approach not only addresses the critical challenges regarding religious literacy but also indicates how religious education can foster meaningful engagement with religion for broader social cohesion in contemporary society.

3.3. Religious Literacy Education and Its Implications for Higher Education

Based on our exploration of Dongguk and Yonsei Universities, we have demonstrated the ways in which their religious education curricula contribute to enhancing students’ religious literacy. As part of our exploration, we now return to the challenges of religious literacy in contemporary South Korean society. Our analysis of the data from the Religious Literacy Survey 2023 revealed three critical issues: First, South Koreans demonstrated a paradoxical set of attitudes regarding religion, indicating a significant tension between their general acceptance of religious diversity and their hesitation toward practical engagement with religious differences, with that hesitation primarily stemming from insufficient knowledge of religious traditions. Second, despite the increasing trend toward being religiously unaffiliated, many South Koreans continued to recognize religion’s essential role in addressing profound existential uncertainties that persist, even amid scientific and technological advancement. Third, South Koreans expected religious traditions to adapt to contemporary social and cultural contexts while preserving their core functions; however, many institutional religions have largely failed to meet this expectation. These challenges highlight the crucial importance of religious literacy and its two essential functions: (a) deepening individuals’ understanding of various religious traditions and (b) promoting recognition of newly emerging religious perspectives that respond to contemporary societal and cultural needs. These functions, we suggest, contribute to addressing the identified issues by reducing barriers to interreligious engagement and demonstrating religion’s enduring relevance and its positive influences in contemporary society.

The emerging scholarly discourses in South Korea also support our argument that education to enhance religious literacy is critical for addressing these challenges (e.g., Lee 2023; Park 2023; Seong 2024a, 2024b). Seong (2024a, 2024b), for instance, provides an in-depth analysis of the current religious landscape in South Korea, highlighting the urgent need for religious literacy education. His research demonstrates that the fundamental existential questions that religions have historically engaged with continue to shape human experience, albeit in the context of the significant increase in religiously unaffiliated individuals in South Korea. In this context, he emphasizes that disengagement from institutional religions does not signal a rejection of spiritual concerns but rather reveals an increasing deficit in religious literacy—a phenomenon that calls for educational approaches rather than passive acceptance of an inevitable process of social evolution. Similarly, Lee (2023) underscores the importance of religious education by examining the rising number of religiously unaffiliated individuals, particularly among younger generations in South Korea, who live with persistent anxiety, emotional distress, and a deep sense of unhappiness. His work specifically suggests “spirituality education” as an approach to religious education that enables students to explore fundamental questions relating to religiosity without feeling obligated to engage with institutionalized religion.

Synthesizing these discourses with our in-depth analysis from this study, we articulate that the cases of Dongguk and Yonsei Universities serve as exemplars of effective educational and pedagogical approaches to enhancing religious literacy within the landscape of higher education. As described, these institutions have developed integrative educational frameworks that cultivate students’ foundational knowledge of particular religious traditions (e.g., Protestant Christianity and Buddhism) while enabling them to engage meaningfully with contemporary societal and cultural issues through this religious understanding. In other words, these cases highlight the significant potential of religious education to foster religious literacy that can contribute to broader social cohesion and interreligious engagements in and for contemporary South Korean society.

Furthermore, aligned with other scholars (e.g., Park 2023; Seong 2024a, 2024b), we advocate for the broader dissemination of these educational approaches throughout the higher education landscape in (but not limited to) South Korea. At this point, we must acknowledge the inherent limitations of the cases of Dongguk and Yonsei Universities, despite their effective approaches to enhancing religious literacy: as private educational institutions that are affiliated with specific religious organizations, they necessarily focus on particular religious traditions (e.g., Protestant Christianity and Buddhism). This specificity, while providing students with thorough knowledge of particular religious traditions, may pose challenges in fostering a more comprehensive and diverse approach to religious literacy education.

Given these challenges, we emphasize the need for a more integrated approach that extends beyond those that are typically employed by religiously affiliated private institutions. In addition to courses that focus on specific religious traditions, curricula for religious literacy education should incorporate broader perspectives on religion itself. This curricular framework would include rigorous religious studies across various fields that examine the historical, philosophical, sociological, and cultural dimensions of religion in ways that are not confined to any particular tradition. Through this interdisciplinary approach, students would develop not only knowledge of religion, including various religious traditions, but also the necessary critical thinking skills to navigate complex religious landscapes in contemporary society.

Moreover, we argue that this integrative approach to religious literacy should become a foundational element of general education curricula across institutions for higher education. By incorporating religious literacy education into fundamental educational frameworks, the institutions would cultivate students, regardless of their religious affiliations, with a more comprehensive understanding of religious diversity, interreligious dynamics, and the role of religion in contemporary society. As students develop religious literacy through general education curricula, they will engage more meaningfully with complex religious issues that are embedded in their daily lives, fostering deeper and more thoughtful interactions with diverse religious perspectives and values in and for contemporary society. In that sense, this curricular integration will help address the widening gap between the general acknowledgment of religious diversity and practical engagement with religious differences—a critical challenge that we identified in contemporary South Korean society.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we identified the notable challenges relating to religious literacy in contemporary South Korean society. By analyzing the data from the Religious Literacy Survey 2023, we traced that the paradoxical attitudes stem primarily from an increasing deficit in religious literacy among South Koreans. One of the challenges is the paradoxical relationship between acceptance of religious diversity and practical interreligious engagement among South Koreans. The significant gap between general acceptance and practical interaction with religious difference points to an unfamiliarity with different religious traditions, which might shape these ambivalent attitudes. This unfamiliarity manifests in limited knowledge of various religious traditions and their fundamental teachings, thereby creating barriers to meaningful interreligious interaction in South Korea. Our findings further illustrate that many South Koreans expect that religious traditions should evolve in response to contemporary societal changes while maintaining their essential functions in addressing profound existential uncertainties. In this context, we propose that the growing religiously unaffiliated population in South Korea does not signify a rejection of religion per se but rather reflects declining religious literacy that often prevents meaningful interreligious engagement. We thus suggest that education aimed at enhancing religious literacy emerges as crucial for contemporary society in addressing the challenges that we identified in this study.

Based on our in-depth analysis, we examined the religious education curricula in Dongguk and Yonsei Universities as cases of religious literacy education in South Korea. These institutions serve as exemplars, having developed curricula for religious education that not only deepen students’ understanding of specific religious traditions but also help them recognize religion’s enduring relevance in addressing contemporary societal and cultural challenges. Building on these cases, while recognizing their limitations as religiously affiliated institutions that are focused primarily on particular religious traditions, we emphasize the need for a more integrated educational approach to religious literacy—one that extends beyond specific traditions and incorporates religious studies that examine historical, philosophical, sociological, and cultural dimensions of religion itself. With this integrated approach, we further suggest the broader implementation of religious literacy education across higher education institutions as a crucial pathway to address the paradoxical attitudes that we identified, thus bridging the gap between the general support for religious diversity and practical interreligious engagement. Such educational approaches, we suggest, provide valuable insights into fostering social cohesion and meaningful interreligious engagement in South Korea and beyond.

Our findings in this study suggest a crucial direction for future research. At the outset, as the Religious Literacy Survey 2023 and its relevant studies represent an initial pioneering effort in South Korea, longitudinal follow-up of these studies is necessary. Research conducted at regular intervals would be able to accumulate data for long-term analysis, which is essential for extending our understanding of religious literacy in contemporary South Korea. Furthermore, prospective studies could investigate various ways in which educational (and pedagogical) approaches effectively balance specialized knowledge of specific religious traditions with broader religious studies that engage with fundamental aspects of religion per se. In addition, researchers could explore how these approaches can be adapted across different institutional contexts, including public and non-religiously affiliated universities. These kinds of prospective studies could also incorporate another critical research direction—comparative studies that analyze the differences between university students who have and have not received religious education, which would assess the impact of education for enhancing religious literacy. Such research would provide valuable insights into the integration of religious literacy education into general education requirements, making it more accessible to students from diverse backgrounds, while respecting institutional differences. These prospective studies will contribute to addressing ongoing challenges associated with religious literacy, which is essential for fostering more meaningful interreligious engagement in increasingly diverse educational and societal contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G. and J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G. and J.K.; writing—review and editing, J.G. and J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the exclusive use of publicly available data from the Religious Literacy Survey 2023, officially published by MINDLAB and Hankook Research. This waiver is in accordance with Article 13 of the Enforcement Rule of Bioethics and Safety Act of the Republic of Korea, which exempts research utilizing existing data or documents related to research subjects without the collection of personally identifiable information from IRB review requirements.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This survey was designed and developed by MINDLAB as part of their religious literacy project and conducted by Hankook Research. As a non-profit incorporated association in South Korea, MINDLAB focuses on exploring religious and humanistic wisdom traditions and spirituality for the cultivation of practical wisdom for a meaningful life. The organization has various projects, including religious literacy research, spiritual human studies, and archiving of wisdom traditions. |

| 2 | This academic conference, hosted by the Korean Association for the Study of Religion, featured Hae-Young Seong, who participated in MINDLAB’s religious literacy research. He not only served as a keynote speaker but also took on the role of chair for the Religious Literacy Special Session. |

| 3 | As the concept of religious literacy has gradually developed in recent years, the contrasting concept of religious illiteracy has also been widely used. However, it is important to note that religious illiteracy should be understood as a concept that exists in opposition to religious literacy. |

| 4 | It is interesting that this approach resembles recent scholarship on defining the concept of religion itself. One substantial example of this scholarship is offered by Nongbri (2013): “The real problem is that the particular concept of religion is absent in the ancient world. The very idea of “being religious” requires a companion notion of what it would mean to be “not religious,” and this dichotomy was not part of the ancient world” (p. 4, italics in original). |

| 5 | The question numbers correspond to the original survey report (MINDLAB and Hankook Research 2023). |

| 6 | The agreement rate combines “strongly agree” and “agree” responses. |

| 7 | The disagreement rate combines “strongly disagree” and “disagree” responses. |

| 8 | Statistics Korea has included religious population surveys as part of the Population and Housing Census every ten years since 1985. While the Population and Housing Census is conducted every five years, religious population data are collected in a ten-year cycle, reflecting the assessment that religious demographics indicate relatively stable patterns of change. The survey has been conducted four times, with the most recent being from 22 October to 15 November 2015. Statistics Korea published the results of this survey on 19 December 2016. |

| 9 | A number of scholars in the field of religious studies have recently published in-depth studies regarding secularization. For some notable examples, please see Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity by Asad (2003) and A Secular Age by Taylor (2007). |

| 10 | The lack of understanding about other religions in multi-religious societies represents a prominent example of declining religious literacy, regardless of one’s own religious faith and/or conviction. Regarding this point, especially related to the context of South Korea, Seong’s (2024a) explanation is noteworthy: Korean society represents an unprecedented case—a multi-religious society that simultaneously experiences prominent dereligionization trends. This situation underscores the importance of religious literacy, as religion remains a fundamental element of identity formation that shapes the ways individuals live and behave. Therefore, literacy regarding one’s own religion, the religions of others, and religion in general plays vital roles in understanding and transforming the dynamics of individuals and collective (pp. 12–16). |

References

- Arthur, James. 2006. Faith and Secularisation in Religious Colleges and Universities. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Asad, Talal. 2003. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, Chae-Yong 정재영. 2019. Hangukinui Dayanghan Jonggyojeok Chawon한국인의 다양한 종교적 차원: 한국인의 종교성 척도 개발을 위한 기초 연구 [Various Religiosity of Koreans: An Essay on the Development of Standard on Korean Religiosity]. Hyonsang-Gwa-Insik 현상과 인식 43: 135–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Jahyun. 2023. The Interdisciplinary Study about Sasipgujae (四十九齋): Based on the Theory of Antarābhava. Ph.D. dissertation, Dongguk University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, January. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Jahyun, and Juhwan Kim. 2024a. Navigating the Intersections of Religion and Education Reflected in the Institutional Mission: Examining the Case of Dongguk University as a Buddhist-Affiliated Institution in South Korea. Religions 15: 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]