Elusive Notions of Bodhisattvas: Personified, Idealized, Mystified, Naturalized, and Integral

Abstract

1. Introduction

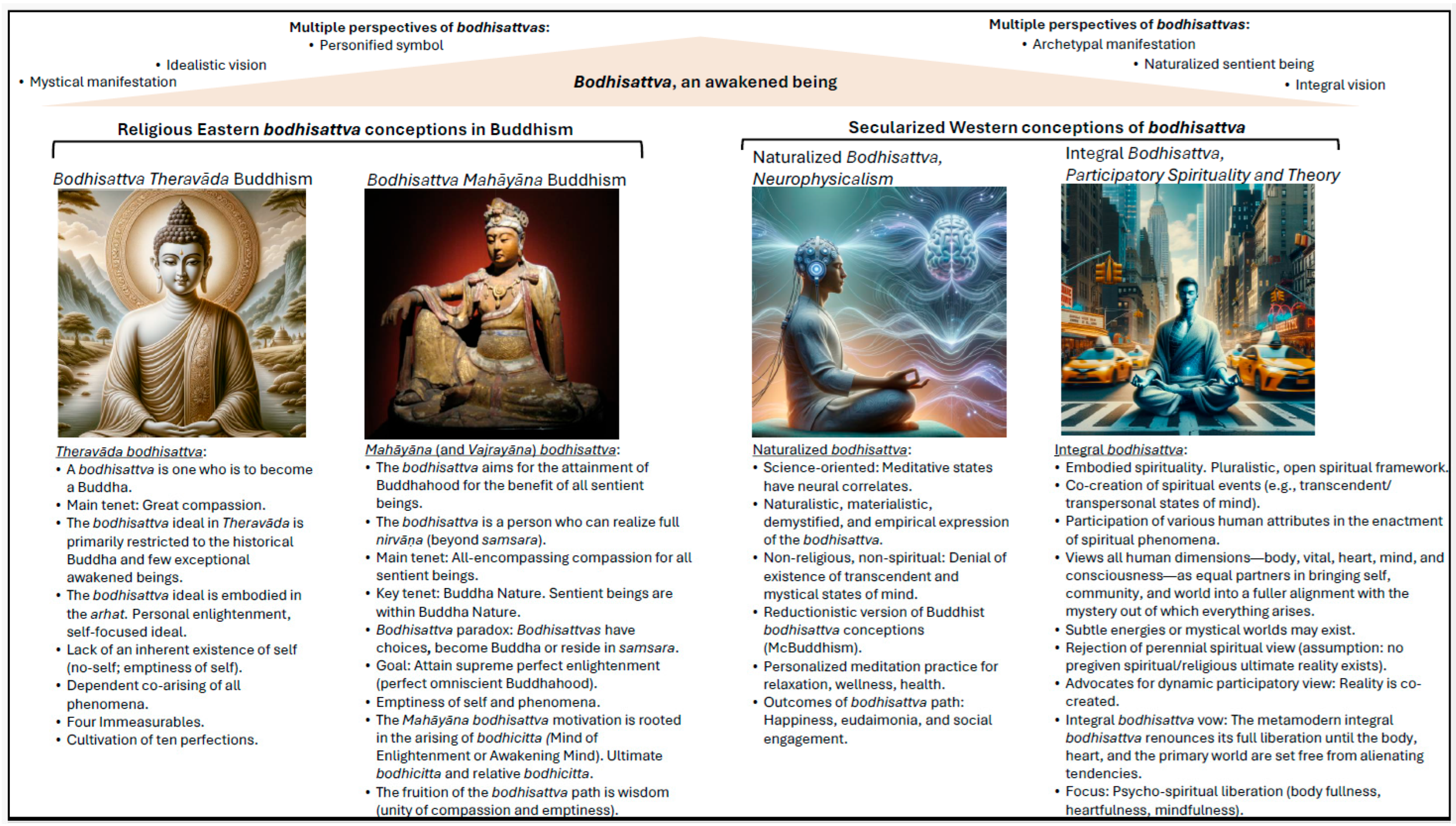

2. Historical and Traditional Buddhist Bodhisattva Conceptions

2.1. Buddhist Bodhisattvas

2.1.1. The Bodhisattva in Theravāda Buddhism

2.1.2. The Bodhisattva in Mahāyāna Buddhism

“In this kind of “top-down” approach to awakening, it may no longer be correct to say that “deluded individuals have buddha-nature” or that “individuals become buddhas;” rather, it might be more accurate to say that buddhas just appear to be deluded individuals and that all living beings are simply buddhas in the process of waking up from this delusion. That is, rather than saying that buddha-nature is within sentient beings, we can more properly say that sentient beings are within buddha-nature, in the sense that it is buddhas who appear as and for sentient beings. In the same vein, it no longer holds that ordinary beings become buddhas, but rather, that buddhas become buddhas”.

“May the precious spirit of awakeningArise where it has not arisen,Where it has arisen, may it not dissipate,But further and further increase”.

3. Philosophical and Psychospiritual Views of Buddhist Bodhisattvas

3.1. Buddhist Philosophical Views—No-Self, Emptiness, Personhood, Buddha Nature

3.2. Personified, Idealized, and Mystified Bodhisattvas

“Living beings are infinite; I vow to free them.Delusions are inexhaustible; I vow to cut through them.Dharma gates are boundless; I vow to enter them.The Buddha Way is unsurpassable; I vow to realize it.”.

4. Non-Buddhist Bodhisattvas

4.1. Naturalized Bodhisattvas

4.2. Integral Bodhisattvas

5. Buddhist Bodhisattvas’ Morals: Paradoxes and Obstacles

5.1. Key Tenets and Obstacles to Buddhist Bodhisattvas’ Motivations

5.2. The Bodhisattva Paradox

6. Ethical Implications of Becoming and Being a Bodhisattva

6.1. Buddhist Ethics and the Eastern Bodhisattva

“The Buddha is approached and asked by the bodhisattva mahāsattva Avalokiteśvara about the qualities that should be cultivated by a bodhisattva who has just generated the altruistic mind set on attaining awakening. The Buddha briefly expounds seven qualities that should be practiced by such a bodhisattva, emphasizing mental purity and cognitive detachment from conceptuality”.

6.2. Non-Buddhist Ethics and Western Bodhisattva Conceptions

6.3. Tensions Between Bodhisattva Morals and Contemporary Moral Relativism in the U.S

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Airoboman, Felix Airoboman. 2021. Ethical Relativism, Environmental Ethics, and Global Environmental Care. NIU Journal of Social Sciences 6: 141–54. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Larry, and Michael Moore. 2020. Deontological Ethics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available online: https://stanford.library.sydney.edu.au/archives/win2015/entries/ethics-deontological/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Ardelt, Monika, and Sabine Grunwald. 2018. The Importance of Self-Reflection and Awareness for Human Development in Hard Times. Research in Human Development Journal 15: 187–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiner, Allan Hunt. 1990. Dharma Gaia: A Harvest of Essays in Buddhism and Ecology. Berkeley: Parallax Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, Monica. 2022. Embracing the Paradox: A Bodhisattva Path. Religions 13: 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhikkhu, Bodhi, ed. 2005. In the Buddha’s Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon. Somerville: Wisdom. [Google Scholar]

- Blofeld, John. 2009. Bodhisattva of Compassion: The Mystical Tradition of Kuan Yin. Boulder: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Brunnhölzl, Karl. 2018. A Compendium of the Mahāyāna: Asaṅga’s Mahāyānasaṃgraha and Its Indian and Tibetan Commentaries. Boulder: Shambhala, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Buddhist Text Translation Society. 2014. Sutra of the Past Vows of Hte Earth Store Bodhisattva. Translated by Tang Dynasty Tripitaka Master Shikshananda of Udyana. Burlingame: Buddhist Text Translation Society. [Google Scholar]

- Buswell, Robert E., Jr., and Donald S. Lopez. 2014. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cabot, Zayin. 2018. Ecologies of Participation: Agents, Shamans, Mystics, and Diviners. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, Christine. 2014. Mindfulness and Bodyfulness: A New Paradigm. The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry 1: 69–88. Available online: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1009&context=joci (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Cho, Francisca. 2017. Buddhism and Science as Ethical Discourse. In The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism. Edited by Michael Jerryson. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 687–700. [Google Scholar]

- Chödrön, Pema. 2007. No Time to Lose: A Timely Guide to the Way of the Bodhisattva. Edited by Helen Berliner. Boston: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Chödrön, Pema. 2018. Becoming Bodhisattvas: A Guidebook for Compassionate Action. Edited by Helen Berliner. Boulder: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. 2010. Training the Mind and Cultivating Loving Kindness. Edited by Judy L. Lief. Boston: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. 2013. The Profound Treasury of the Ocean of the Dharma: The Bodhisattva Path of Wisdom and Compassion. Edited by Judy L. Lief. Boston: Shambhala, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. 2014. The Bodhisattva Path of Wisdom and Compassion: The Profound Treasury of the Ocean of Dharma. Edited by Judy L. Lief. Boston: Shambhala, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, Scott D. 2023. Embodiment, Empathy, and the Call to Compassion: Engendering Care and Respect for ‘the Other’ in a More-than-Human World. In Empathy and Ethics. Edited by Magnus Englander and Susi Ferrarello. London: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 347–74. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, Barbra R. 2018. The Changing Way of the Bodhisattva: Superheroes, Saints, and Social Workers. In The Oxford Handbook of Buddhist Ethics. Edited by Daniel Cozort and James Mark Shields. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 135–61. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, Thomas. 1993. The Flower Ornament Scripture: A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sūtra. Boston: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Colman, Andrew M. 2015. Oxford Dictionary of Psychology, 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conze, Edward. 2001. Buddhist Wisdom: The Diamond Sutra and the Heart Sutra. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Coseru, Christian. 2017. Freedom from Responsibility: Agent-Neutral Consequentialism and the Bodhisattva Ideal. In Buddhist Perspectives on Free Will—Agentless Agency? Edited by Rick Repetti. New York: Routledge, pp. 92–106. [Google Scholar]

- Dalai Lama. 2009a. Tenzin Gyatso. In For the Benefits of All Beings: A Commentary on the Way of the Bodhisattva. Translated by The Padmakara Translation Group. Boston: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Dalai Lama. 2009b. The Heart of Understanding: Commentary on the Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra. Edited by Peter Levitt. Berkeley: Parallax Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dalai Lama. 2018. The Bodhisattva Guide. Translated by The Padmakara Translation Group. Boulder: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, Michael. 2005. Shadow, Self, Spirit: Essays in Transpersonal Psychology. Exeter: Imprint Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Danto, Arthur C. 1987. Mysticism and Morality: Oriental Thought and Moral Psychology. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Gordon. 2013. Traces of Consequentialism and Non-Consequentialism in Bodhisattva Ethics. Philosophy East and West 63: 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degé Kangyur. 2016. The Noble Mahāyāna Sūtra ‘The Inquiry of Avalokiteśvara on the Seven Qualities’. University of Calgary Buddhist Studies Team, Led by J.B. Apple, Trans.). Toh 150. Vol. 57 (mdo sde, pa), folios 331.a–331.b. 84000: Translating the Words of the Buddha. Available online: http://read.84000.co/section/all-translated.html (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Dervin, Fred. 2012. Cultural Identity, Representation and Othering. In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Intercultural Communication. Edited by Jane Jackson. London: Routledge, pp. 181–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbordes, Gaëlle, Tim Gard, Elizabeth A. Hoge, Britta K. Hölzel, Catherine Kerr, Sara W. Lazar, Andrew Olendzki, and David R. Vago. 2015. Moving beyond Mindfulness: Defining Equanimity as an Outcome Measure in Meditation and Contemplative Research. Mindfulness 6: 356–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovidio, John F., Jane Allyn Piliavin, David A. Schroeder, and Louis A. Penner. 2012. The Social Psychology of Prosocial Behavior. New York: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Drewes, David. 2021. The Problem of Becoming a Bodhisattva and the Emergence of Mahāyāna. History of Religions Journal 61: 145–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, John J. 2023. Why Empathy Means Nothing—And Everything—For Ethics. In Empathy and Ethics. London: Rowan & Littlefield, pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, Douglas S. 2014a. How Nonsectarian Is ‘Nonsectarian’? Jorge Ferrer’s Pluralist Alternative to Tibetan Buddhist Inclusivism. Sophia 53: 339–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, Douglas S. 2014b. Onto-Theology and Emptiness: The Nature of Buddha-Nature. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 82: 1070–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, Douglas S. 2019a. The Profound Reality of Interdependence: An Overview of the Wisdom Chapter of the Way of the Bodhisattva. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, Douglas S. 2019b. Tibetan Buddhist Philosophy of Mind and Nature. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, Douglas S. 2023. Two Dimensions of a Bodhisattva. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 42: 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, Chandra. 2023. Embodying Tara: Twenty-One Manifestations to Awaken Your Innate Wisdom. Boulder: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Effron, Daniel A., and Beth Anne Helgason. 2022. The Moral Psychology of Misinformation: Why We Excuse Dishonesty in a Post-Truth World. Current Opinion in Psychology 47: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, Leela. 2003. Transforming Feminist Practice: Non-Violence, Social Justice, and the Possibilities of a Spiritualized Feminism. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, Jorge N. 2002. Revisioning Transpersonal Theory: A Participatory Vision of Human Spirituality. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, Jorge N. 2006. Embodied Spirituality, Now and Then. Tikkun 21: 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, Jorge N. 2008. What Does It Mean to Live a Fully Embodied Spiritual Life? International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 27: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, Jorge N. 2011. Participatory Spirituality and Transpersonal Theory: A Ten-Year Retrospective. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 43: 1–34. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1067.2045&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Ferrer, Jorge N. 2017. Participation and the Mystery: Transpersonal Essays in Psychology, Education, and Religion. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, Kieran, and Peter C. Jupp, eds. 2001. Virtue, Ethics, and Sociology: Issues of Modernity and Religion. New York: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, Owen. 2011. The Bodhisattva’s Brain: Buddhism Naturalized. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fowers, Blaine J., Lukas F. Novak, Alex J. Calder, and Nona C. Kiknadze. 2024. Can a Theory of Human Flourishing Be Formulated? Toward a Science of Flourishing. Review of General Psychology 28: 123–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, Jay L. 1995. The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield, Jay L. 2010. What Is It like to Be a Bodhisattva? Moral Phenomenology in Śāntideva’s Bodhicaryāvatāra. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 33: 333–57. Available online: https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/jiabs/article/viewFile/9285/3146 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Garfield, Jay L. 2022a. Buddhist Ethics: A Philosophical Exploration. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield, Jay L. 2022b. Losing Ourselves: Learning to Live Without a Self. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield, Jay L., Maria Heim, and Robert H. Sharf. 2025. How to Lose Yourself: An Ancient Guide to Letting Go. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard, Jessica. 2021. The Uneducated and the Politics of Knowing in ‘Post Truth’ Times: Ranciere, Populism and in/Equality. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 42: 155–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gethin, Rupert. 1998. The Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gleig, Anne. 2019. American Dharma: Buddhism Beyond Modernity. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, Jonathan C., and Douglas S. Duckworth, eds. 2019. Readings of Śāntideva’s Guide to Bodhisattva Practice. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, Daniel, and Richard J. Davidson. 2017. Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind, Brain, and Body. New York: Penguin Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Charles. 2009. Consequences of Compassion: An Interpretation and Defense of Buddhist Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Charles. 2016a. Consequentialism, Particularism, and the Emptiness of Persons: A Response to Vishnu Sridharan. Philosophy East and West 66: 637–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, Charles. 2016b. Śāntideva. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophie. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/shantideva/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Goodman, Charles. 2017. Ethics in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2017/entries/ethics-indian-buddhism/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Goodman, Charles. 2019. Śāntideva’s Ethics of Impartial Compassion. In Readings of Śāntideva’s Guide to Bodhisattva Practice. Edited by Jonathan C. Good and Douglas S. Dougworth. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 209–20. [Google Scholar]

- Grosso, Michael. 2015. The ‘Transmission’ Model of Mind and Body. In Beyond Physicalism: Toward Reconciliation of Science and Spirituality. Edited by Edward F. Kelly, Adam Crabtree and Paul Marshall. London: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 79–114. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald, Sabine. 2021. Embodied Liberation in Participatory Theory and Buddhist Modernism Vajrayāna. Journal of Dharma Studies 4: 159–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunwald, Sabine. 2023a. Ecosattvas and Ecodharma: Modern Buddhist Perspectives of Soil and the Environment. In Cultural Understanding of Soils. Edited by Nikola Patzel, Sabine Grunwald, Erik C. Brevik and Christian Feller. New York: Springer, pp. 245–60. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald, Sabine. 2023b. Take Care of Soils: Toward a Pluralistic Integral Soil Ethics. In Cultural Understanding of Soils. Edited by Nikola Patzel, Sabine Grunwald, Erik C. Brevik and Christian Feller. New York: Springer, pp. 429–52. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald, Sabine. 2024. Critical Hermeneutical Inquiry: Participatory Spirituality, Buddhist Modernism, and Secularized Buddhism in North America. In The Routledge Handbook of Research Methods in Spirituality and Contemplative Studies. Edited by Bernadette Flanagan and Kerri Clough. New York: Routledge, pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hadash, Yuval, Natalie Segev, Galia Tanay, Pavel Goldstein, and Amit Bernstein. 2016. The Decoupling Model of Equanimity: Theory, Measurement, and Test in a Mindfulness Intervention. Mindfulness 7: 1214–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, Clarence H. 1950. The Idea of Compassion in Mahāyāna Buddhism. Journal of the American Oriental Society 70: 145–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, Michael. 2023. The Politics of Post-Truth. Critical Review 35: 40–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, Tobin. 1999. The Refinement of Empathy. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 39: 111–25. Available online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0022167899394007 (accessed on 10 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Harvey, Peter. 2000. An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hasenkamp, Wendy, and Janna R. White, eds. 2017. The Monastery and the Microscope—Conversations with the Dalai Lama on Mind, Mindfulness, and the Nature of Reality. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, Stephen R. C. 2011. Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault. Roscoe: Ockhams’s Razor. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenback, Jess B. 1996. Mysticism: Experience, Response, and Empowerment. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hursthouse, Rosalind, and Glen Pettigrove. 2016. Virtue Ethics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-virtue/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Jennings, William H. 1996. Agape and Karuna: Some Comparisons. Journal of Contemporary Religion 11: 209–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Robert, and Adam Cureton. 2018. Kant’s Moral Philosophy. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Spring 2018 ed. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Stanford: Stanford University. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/kant-moral/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Jordan, Judith V. 1997. Clarity in Connection: Empathic Knowing, Desire, and Sexuality. In Women’s Growth in Diversity. Edited by Judith V. Jordan. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 50–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kaparo, Risa F. 2012. Awakening Somatic Intelligence: The Art and Practice of Embodied Mindfulness. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Karma Lekshe Tsomo. 2001. Death, Identity, and Enlightenment in Tibetan Culture. The International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 20: 151–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, Leslie S., ed. 1981. The Bodhisattva Doctrine in Buddhism. Calgary: Wilfried University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khensur Rinpoche Jampa Tegchok. 2012. Insight into Emptiness. Edited by Thubten Chodron. Translated by Steve Carlier. Somerville: Wisdom. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, Bassam. 2019. Compassion: Embodied and Embedded. Mindfulness 10: 2363–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, Bassam, Bärbel Knäuper, Francesco Pagnini, Natalie Trent, Alberto Chiesa, and Kimberly Carrière. 2017. Embodied Mindfulness. Mindfulness 8: 1160–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Young Woon. 2010. The Beauty of Balance: A Theological Inquiry into Paradox. Lanham: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, Bryan, and Ian Q. Whishaw. 2021. Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology, 7th ed. New York: Worth Publ. [Google Scholar]

- Kubo, Tsugunari, and Akira Yuyama. 2007. The Lotus Sūtra. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. Available online: http://www.bdk.or.jp/document/dgtl-dl/dBET_T0262_LotusSutra_2007.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Lahood, Gregg. 2007. The Participatory Turn and the Transpersonal Movement: A Brief Introduction. ReVision: A Journal of Consciousness and Transformation 29: 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighton, Taigen Dan. 2012. Faces of Compassion: Classic Bodhisattva Archetypes and Their Modern Expression. Boston: Wisdom. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Neil. 2002. Moral Relativism. London: Oneworld Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, Ullrich K. H. Ecker, and John Cook. 2017. Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and Coping with the ‘Post-Truth’ Era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 6: 353–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, Alan C., Susan H. Berman, Brian M. Berman, and Susan L. Prescott. 2021. Healing Anthropocene Syndrome: Planetary Health Requires Remediation of the Toxic Post-Truth Environment. Challenges 12: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Look, Brandon C. 2020. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/leibniz/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Loy, David R. 1983. How Many Nondualities Are There? Journal of Indian Philosophy 11: 413–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, David R. 1998. Nonduality: A Study in Comparative Philosophy. Amherst: Humanity Books. [Google Scholar]

- Loy, David R. 2015. A New Buddhist Path: Enlightenment, Evolution and Ethics in the Modern World. Boston: Wisdom. [Google Scholar]

- Loy, David R. 2019. Ecodharma: Buddhist Teachings for the Ecological Crisis. Somerville: Wisdom. [Google Scholar]

- Lyotard, Jean-Francois. 2003. Postmodern Fables. Translated by G. van den Abbeele. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, Matthew. 2014. Buddhism Naturalized? Review of Owen Flanagan, the Bodhisattva’s Brain: Buddhism Naturalized. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 13: 503–6. Available online: https://philpapers.org/rec/MACBNR (accessed on 4 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mahipalan, Manju. 2022. The Interplay between Spirituality, Compassion and Citizenship Behaviours in the Lives of Educators: A Study. International Journal of Ethics and Systems 39: 804–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makransky, John J. 1997. Buddhahood Embodied: Sources of Controversy in India and Tibet. New York: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marlock, Gustl, and Halko Weiss, eds. 2015. The Handbook of Body Psychotherapy & Somatic Psychology. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, Ken. 2014. Reflections on Silver River: Tokme Zongpo’s Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva. Sonoma: Unfettered Mind Media. [Google Scholar]

- Mickey, Sam, Sean Kelly, and Adam Robbert, eds. 2017. The Variety of Integral Ecologies: Nature, Culture, and Knowledge of the Planetary Era. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, Mario, and Phillip R. Shaver, eds. 2010. Prosocial Motives, Emotions, and Behavior. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Modood, Tariq, and Simon Thompson. 2022. Othering, Alienation and Establishment. Political Studies 70: 780–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, Chris. 2012. The Republican Brain: The Science of Why They Deny Science and Reality. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Moscowitz, David. 2018. Affect, Cruelty, and the Engagement of Visual Intimacy. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 15: 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattier, Jan. 2003. A Few Good Men: The Bodhisattva Path According to the Inquiry of Ugra (Ugraparipṛcchā). Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, Kristin D. 2003. The Development and Validation of a Scale to Measure Self-Compassion. Self and Identity 2: 223–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnuma, Reiko. 1998. The Gift of the Body and the Gift of Dharma. History of Religions 37: 323–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnuma, Reiko. 2019. Bodies and Embodiment in the Bodhicaryāvatāra. In Readings of Śāntideva’s Guide to Bodhisattva Practice. Edited by Jonathan C. Gold and Douglas S. Duckworth. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 114–31. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Richard K., ed. 2021. Secularizing Buddhism: New Perspectives on a Dynamic Tradition. Boulder: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Pelden, Kunzang. 2007. The Nectar of Manjushri’s Speech: A Detailed Commentary on Shantideva’s Way of the Bodhisattva. Translated by Padmakara Translation Group. Boulder: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Perrett, Roy W. 1986. The Bodhisattva Paradox. Philosophy East and West 36: 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, John W. 1999. Mipham’s Beacon of Certainty: Illuminating the View of Dzogchen. Somerville: Wisdom. [Google Scholar]

- Pond, Philip. 2020. Why Does Nobody Know Anything Anymore? In Complexity, Digital Media and Post Truth Politics: A Theory of Interactive Systems. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, John. 2007. Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism. Boston: Snow Lion. [Google Scholar]

- Puhakka, Kaisa. 2000. An Invitation to Authentic Knowing. In Transpersonal Knowing: Exploring the Horizon of Consciousness. Edited by Tobin Hart, Peter L. Nelson and Kaisa Puhakka. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Weiguo. 2015. Dehistoricized Cultural Identity and Cultural Othering. In The Discourse of Culture and Identity in National and Transnational Contexts. Edited by Christopher Jenks, Jackie Lou and Aditi Bhatia. London: Routledge, pp. 148–64. [Google Scholar]

- Queen, Christopher S., ed. 2000. Engaged Buddhism in the West. Somerville: Wisdom. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, Reginald A. 2000. Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism. Boston: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, Reginald A. 2002. Secret of the Vajra World: The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet. Boston: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Ronkin, Noa. 2018. Abhidharma. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/abhidharma/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Rosmarin, David H., Caroline C. Kaufman, Stephanie Friree Ford, Poorvi Keshava, Mia Drury, Sean Minns, Cheri Marmarosh, Avijit Chowdhury, and Matthew D. Sacchet. 2022. The Neuroscience of Spirituality, Religion, and Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Synthesis. Journal of Psychiatric Research 156: 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothberg, Donald. 2006. The Engaged Spiritual Life: A Buddhist Approach to Transforming Ourselves and the World. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, Maggie. 2024. Bodhisattva. In Encyclopedia of Heroism Studies. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahdra, Baljinder K., Joseph Ciarrochi, and Philip Parker. 2016. Nonattachment and Mindfulness: Related but Distinct Constructs. Psychological Assessment 28: 819–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, Jeffrey. 1997. The Bodhisattva Ideal in Theravāda Buddhist Theory and Practice: A Reevaluation of the Bodhisattva-Śrāvaka Opposition. Philosophy East and West 47: 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, Vincent. 2017. Buddha’s Mom: The Neurobiology of Spiritual Awakening. Charleston: LuLu Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shantideva. 2011. The Way of the Bodhisattva: A Translation of the Bodhicharyāvatāra. Translated by Padmkara Translation Group. Boston: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Simmer-Brown, Judith. 2001. Dakini’s Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism. Boston: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, Sharon A. 2017. Buddhism and Gender. In The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism. Edited by Michael Jerryson. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 635–49. [Google Scholar]

- Surowiec, Pawel, and Christopher Miles. 2021. The Populist Style and Public Diplomacy: Kayfabe as Performative Agonism in Trump’s Twitter Posts. Public Relations Inquiry 10: 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temprano, Victor Gerard. 2013. Defining Engaged Buddhism: Traditionists, Modernists, and Scholastic Power. Buddhist Studies Review 30: 261–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thich Nhat Hanh. 1987. Interbeing: Fourteen Guidelines for Engaged Buddhism, 3rd rev. ed. New York: Parallax Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Caroline L., Mariana Cuceu, Hyo J. Tak, Marija Nikolic, Sakshi Jain, Theodore Christou, and John D. Yoon. 2019. Predictors of Empathic Compassion: Do Spirituality, Religion, and Calling Matter. Southern Medical Journal 112: 320–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traer, Robert, and Harlan Stelmach. 2007. Doing Ethics in a Diverse World. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tuffley, David, and Śāntideva. 2011. The Bodhicaryavatara: A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life. Scotts Valley: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, Lynn G. 2009. Compassionate Love: A Framework for Research. In The Science of Compassionate Love: Theory, Research, and Application. Edited by Beverley Fehr, Susan Sprecher and Lynn G. Underwood. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele, Tyler J. 2017. On the Promotion of Human Flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114: 8148–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, Francisco J. 1996. Neurophenomenology: A Methodological Remedy for the Hard Problem. Journal of Consciousness Studies 3: 330–49. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, Francisco J., Evan T. Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch. 2016. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vasen, Sīlavādin Meynard. 2018. Buddhist Ethics Compared to Western Ethics. In The Oxford Handbook of Buddhist Ethics. Edited by Daniel Cozort and James Mark Shields. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 317–34. Available online: http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198746140.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780198746140-e-30 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Vessantara. 2003. Tony McMahon. In Female Deities in Buddhism. Birmingham: Windhorse. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Zack. 2017. A Meta-Critique of Mindfulness Critiques: From McMindfulness to Critical Mindfulness. In Handbook of Mindfulness: Culture, Context, and Social Engagement. Edited by Ronald E. Purser, David Forbes and Adam Burke. Cham: Springer, pp. 153–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wellmer, Albrecht. 2007. The Persistence of Modernity: Essays on Aesthetics, Ethics and Postmodernism. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Welwood, John. 2002. Toward a Psychology of Awakening—Buddhism, Psychotherapy and the Path of Personal and Spiritual Transformation. Boston: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Paul. 2010. Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, David B. 2023. Moral Relativism and Pluralism. Oxford: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yaden, David Bryce, and Andrew Newberg. 2016. Neuroscience and Religion: Surveying the Field. In Religion: Mental Religion. Edited by Niki Kasumi Clements. New York: Macmillan, pp. 277–99. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Fuchuan. 2006. There Are No Degrees in a Bodhisattva’s Compassion. Asian Philosophy 16: 189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuo, Yuasa. 1987. The Body: Toward an Eastern Mind-Body Theory. Edited by Thomas P. Kasulis. Translated by Nagatomo Shigenori, and Thomas P. Kasulis. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler, Caroline, and Marian Radke-Yarrow. 1990. The Origins of Empathic Concern. Motivation and Emotion 14: 107–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grunwald, S. Elusive Notions of Bodhisattvas: Personified, Idealized, Mystified, Naturalized, and Integral. Religions 2025, 16, 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060764

Grunwald S. Elusive Notions of Bodhisattvas: Personified, Idealized, Mystified, Naturalized, and Integral. Religions. 2025; 16(6):764. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060764

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrunwald, Sabine. 2025. "Elusive Notions of Bodhisattvas: Personified, Idealized, Mystified, Naturalized, and Integral" Religions 16, no. 6: 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060764

APA StyleGrunwald, S. (2025). Elusive Notions of Bodhisattvas: Personified, Idealized, Mystified, Naturalized, and Integral. Religions, 16(6), 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060764