This article examines the intersection of gender, immigration, and religion in the lives and writings of three German–Jewish women: Selma Stern (1890–1981), Hannah Arendt (1906–1975), and Toni Oelsner (1907–1981). They were among the first generations of German women who earned graduate degrees and pursued an academic career.

1 They all attended university and published intellectual work before emigrating from Nazi Germany. Much of their work was published in the United States, the country in which they settled as refugees during WWII.

2 In their pre-war work, they all took up the issue of Jewish woman’s history, prompted by their own situation as pathbreakers in women’s higher education, but abandoned it in exile (

Hahn 2005, pp. 99–108). They turned instead to the historical development of antisemitism which had forced them to emigrate, and which was culminating in the unthinkable horror of the Holocaust. The whole cultural world of German Jews within which they had moved as well as many family members and friends were destroyed.

Each of these women countered Nazi antisemitism in their scholarship through the figure of the Court Jew. In these works, Stern adapted, Arendt transformed, and Oelsner critiqued what would become a central paradigm in post-war Jewish historiography—the “economic function of the Jews”.

3 This paradigm was first formulated as a historical law by a leader in the German Historical School of Political Economy, Wilhem Roscher. His argument was a philosemitic response to growing antisemitism in the 1870s, which argued that Jews’ positive economic function for Europe should win them emancipation and acceptance. He presented medieval European Jews as an advanced commercial people who provided credit and commerce until “European nations” were able to take over these functions themselves. But these nations’ trade jealousy led to an antisemitic backlash. This narrative is not only inaccurate, but also shares with antisemitic stereotypes false assumptions about Jews’ connection to money, credit, and commerce. I have written an extensive critique of this historical paradigm elsewhere and will not replicate that argument here (

Mell 2017,

2018). Rather, I wish to focus on these women’s role in the formation, alteration, and critique of this historical paradigm—a role heretofore unnoticed in postwar Jewish historiography—as well as situate it within their lived experience as émigrés and immigrants.

This article uses these women’s biographies (based on archival sources, letters, catalogs, and biographies) in order to illuminate the range of their lived experiences as women, as Jews, as immigrants, refugees, and as scholars. They share much, but their differences are illuminating. All three women were pathbreakers in women’s inclusion in the academy, and important Jewish historians and political thinkers. Early in their careers, they were drawn to women’s history by women’s marginality within the academy and to Jewish history by Jews’ exclusion from German society under Nazi rule. They were driven to emigrate by the failure of German–Jewish emancipation. Their shock over the brutality of German antisemitism spurred their path-breaking works on antisemitism in which the figure of the Court Jew plays a central role. By examining their works together with their lives, this article illuminates their shared trajectory as immigrants and women, while recovering the intellectual differences in their response to the political antisemitism which forced their immigration.

This article aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of (1) the dynamics between religion and immigration, (2) the force of gender difference, and (3) the recognition of women’s intellectual contributions to the topic of the ‘Jewish economic function’. The intellectual biographies of these women illuminate the intersection of religion and immigration in multiple ways—from religious persecution propelling their emigration and their intellectual turn to Jewish history to religious networks aiding them in their countries to which they immigrated. Their portrait extends the studies on women as émigrés and intellectuals, complementing the studies on German–Jewish émigrés, which have focused predominantly on male intellectuals.

4 Viewed together, these three scholars illustrate the range of success and failure for those disadvantaged by their status as women, as Jews, and as migrants.

5 Viewing their intellectual work together recovers these women’s significant contribution to the post-war historiography of Jewish history on the Jewish economic function. My purpose is not merely to mark women’s contribution to the formation of the paradigm, but to show how the paradigm was constructed within an experience of failed emancipation and racialized Jewish identity in the 1940s. I aim to mark the contribution these three women made to Jewish economic history, but I argue here as elsewhere that it is time Jewish history move beyond the paradigm of the economic function of the Jews (

Mell 2017,

2018).

In addition to the published works of these scholars and the literature on these scholars, the research for this article is based on the Selma Stern-Taeubler Collection (AR 7160) (

Stern-Taeubler Collection n.d.) and the Toni Oelsner Collection, 1911–1979 (AR 3970) (

Oelsner 1911–1979) held at the Leo Baeck, New York; the Hannah Arendt Personal Library housed at The Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities at Bard College, New York; the Universitätsarchiv Frankfurt am Main file for Toni Oelsner (

UAF n.d.), and published interviews with Toni Oelsner and Hannah Arendt. The methodology here is that of a comparative historical analysis of the biographical and intellectual turns in the lives of these women, who were selected for their intellectual contributions to the ”Jewish economic function”. The guiding question driving the analysis below is how did each of these women contribute, adapt, or critique the historical paradigm of the “Jewish economic function”? By placing their intellectual histories within their biographies, this article illuminates the way in which the persecution of religious identity forcing immigration shaped historical scholarship.

1. Selma Stern (1890–1981)

Stern, Arendt, and Oelsner were born to assimilated, upwardly mobile German–Jewish families in the generation spanning 1890–1910. Stern (

Figure 1), the eldest by 15 years, attained her doctorate in history in 1914.

6 In her youth, she was labeled a “Wunderkind” (wonder child) and was the first girl given permission to attend the boys’ Gymnasium in BadenBaden. “She quickly became the first in her class and, at 18, passed the Abitur [college entrance exam] with honors” (

Leo Baeck Institute–New York n.d.). When Stern’s father died, her mother supported Stern’s education despite the economic hardship. Stern studied in Heidelberg, Frankfurt, and Munich, graduating with a doctorate in 1914 with a thesis on the Prussian nobleman and anarchist Anacharsis Cloots who figured prominently in the French Revolution. Over the course of her life, she would publish five monographs in addition to the seven-volume

Der Preußischen Staat und dyie Juden [

The Prussian State and the Jews], as well as many, many articles, and a historical novel.

7 But as part of the first generation of women academics in Germany, she had no chance to achieve a university position. Her habilitation, which would have qualified her as a university professor, was neither accepted nor rejected at the University of Munich after 4 years’ wait! “For the first time, she became aware of a problem that could not be solved intellectually,” writes her biographer, Marina Sassenberg (

Sassenberg 2000, p. 76). In this period, she explored historically the problem of women’s access to intellectual life in a series of articles on the noblewomen Juliane von Krüdener, Sophie Kurfürstin von Hanover, and Madame de Staël, as well as the Jewish figure Jeanette Wohl. Her last article in women’s history was on the types of Jewish women in different historical periods (

Stern 1914,

1915,

1916,

1921,

1925b,

1926).

These last articles on Jewish women were written from her position at the Akademie für die Wissenschaft des Judentums, the most important institution for Jewish Studies in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s (

Brenner 2017). Her talent had been recognized in 1918 by Eugene Täubler, the ancient historian and director of the Gesamtarchivs der deutschen Juden. And Täubler invited her to join the first staff of the Akademie in Berlin. Stern was the first and only woman. And she held this research position until the Nazis came to power in 1933. Her shift away from women’s history by the late 1920s and 1930s reflected her own feeling that Jewish religious and political problems were much more crucial than those associated with the woman’s question (

Hahn 2005, p. 104). In 1957, Stern commented on her turn from women’s history, writing in a letter to Simon Federbusch:

this kind of work did not give me full satisfaction and I was interested in Jewish religious and political problems, I began to study the history of my people hoping to find a way to understand his [sic!] fate thereby, to understand myself.

Stern turned decisively to Jewish history at the Akademie. In 1925, she published her last piece on Jewish women and her first volume of

Der Preußischen Staat und die Juden. In 1929, her biography of the court Jew Oppenheimer appeared,

Jud Süß: Ein Beitrag zur Deutschen und zur Jüdischen Geschichte [

Jud Suss: A Contribution to German and Jewish History] (

Stern 1925a,

1925b,

1926,

1929). If the limits of women’s emancipation propelled her into Jewish history, her commitment to Jewish history without a gender lens only deepened with the breakdown of Jewish emancipation in Nazi Germany (

Hahn 2005, pp. 99–104).

In 1927, she and Täubler married. Open research ended in 1933 with the Nazi coup, and she was dismissed from her position at the Akademie. But she continued to collect documents until 1938, when the Nazis closed libraries to Jews, and thereafter with the help of friends. In 1934–1935, she and her husband unsuccessfully emigrated to England, returned to Berlin, and took the last ship out to the US in 1941 before the US entered the war. Täubler received a position at Hebrew Union College. Stern, in 1947, became the first Archivist of the Jewish American Archives in Cincinnati.

Though she had saved from destruction the research material on Court Jews that she had painstakingly gathered from 21 German archives, she was paralyzed by the shock and horror of the Holocaust (

Stern 1950, pp. xv–xvii). As she wrote in 1949, “the tragic fate of German Jewry was so stunning as to inhibit me from stirring up the memories of the past” (

Stern 1950, p. xvii). Two things helped to make the publication of

The Court Jew possible in 1950. One was the encouragement of her friend and fellow historian, Jacob Marcus (

Stern 1950, pp. xvi–xvii). The other was the cathartic process of writing the novel,

The Spirit Returneth. The novel was dedicated “to the martyrs of my people” and refracted the genocide of the Holocaust through a historical fiction set in the context of the pogroms of German Jews in the aftermath of the Black Death (

Stern 1946, p. v).

When Stern began research on

The Court Jew before the war, she understood it as a story about Jewish emancipation and assimilation, or what today we would call acculturation. She spoke of herself prior to the war as “sharing in two differing cultural heritages, the Jewish and the German”, without feeling “the tension of such a relationship as a perplexing inner conflict”. This “dual heritage” enriched “her own

Lebensgefuehl”, her way of thinking. And, it was from this position that she researched

the chief problems that interested her, namely, the emancipation of the Jews, that is, the process of their becoming an integral part of the political, economic, and social life of the Sate, and the assimilation of the Jews, that is, the process of their self-adaptation to the culture and spirit of their surroundings.

Moreover,

the writer felt that the problem of the Court Jews merited attention not only in its political and social aspects. They were for her a typical and symbolic phenomenon of general Jewish historical development. By understanding their fate one could at the same time understand the fate of the European Jew who attempted to create a synthesis of two different worlds, without surrendering his identity… The Court Jews appeared to her to be forerunners of emancipation and their history to represent the early period of this movement.

In other words, for Stern, the Court Jew was a Weberian type who concentrated in their individual person the larger process of emancipation and assimilation in Jewish history. Court Jews were not merely economic actors for Stern, but forerunners of her own lived experience of emancipation and acculturation —until the Nazi period.

Stern integrated Court Jews into the general framework of the German Historical School of Political Economy, which regarded societies as progressing through stages of economic development from barter to money to credit. Note in the quote below how Stern describes the economy of the Early Modern Period within this framework.

The period of Absolutism marked the transition from feudalism to absolutism, from Imperium to national State, from medieval economy to a money and credit economy, from traditionalism to early capitalism, from scholastic theories and canonical law to natural law, from a corporative society to one composed of autonomous individuals.

Stern also adopted Roscher’s theory of the Jews’ economic function. As described above, Wilhelm Roscher defended the emancipation of German Jews in the 1870s by arguing that medieval Jews, being more commercially adept, were the tutors of European peoples in trade and commerce. Antisemitism was, he argued, fueled by trade jealousy as European nations began taking over these roles. Roscher’s narrative was resuscitated during WWII by the émigré Jewish historian Guido Kisch and shorn of its comparative perspective and nineteenth-century theory. The economic function of the Jews in Europe was no longer an example of a general pattern, but a unique historical trajectory. Antisemitism was presented as a tragic backlash against liberal economic progress, which stemmed either from ignorance of the modern economy or from economic competition (

Roscher 1878, pp. 321–54;

Roscher 1944;

Mell 2017, pp. 31–41, 77–88).

Stern adapted this narrative to Court Jews, seeing them as the movers and shakers of the new State with its developed legal and economic structures over against the medieval patrimonial forces of the patriciate and nobility. While intrigued by their colorful and adventurous careers,

She was even more concerned with the problem of the economic and social progress of these men, whose progress was closely connected with the development of the German States away from their medieval patrimonial character and towards fully developed legal and economic structures. Thus many Jewish financiers, whose interests coincided with those of the princes and their states, were among the most prominent advisors to the princes and helped prepare the way for the new State over the opposition of the patriciate and the nobility.

This approach to the Court Jew is something Stern shared with novelists like Feuchtwanger, who wrote

Jud Süss, and filmmakers who adapted the novel to the cinema as

Jew Suss (or

Power in the US).

Stern adopted the narrative of the Jewish economic function, but squarely placed it in the early modern period, making the Court Jews’ economic and social progress go hand-in-hand with that of the German States. She also transformed the paradigm of the economic function of the Jews by asking what function Court Jews had for Jewish history. Her answer—they acted for the Jewish people as a bridge between the traditional pre-modern world and the modern emancipated and acculturated world within which she grew up. But Stern found this history painful to approach. Her whole historical standpoint was changed. She could “no longer look upon emancipation as the end of a long process which led to a kind of symbiosis between two national groups” (

Stern 1950, p. xiii). Losing faith in historical progress, she began “to believe that the very basis of historical life is…change…everything is in flux, everything dies” (

Stern 1950, p. xiii).

The Court Jew appeared in 1950 in English in the United States, the same year Hannah Arendt’s

Origins of Totalitarianism appeared. And, Arendt interestingly wrote a book review of

The Court Jews that same year. Arendt perceptively notes there that Stern “is no longer sure of precisely what the court Jews were forerunners of or where the process of emancipation would eventually lead” (

Arendt 1952, p. 177). Arendt concluded the review with the answer she gave to this question in her own

Origins of Totalitarianism.

The solution to the whole question of “Jewish responsibilities” [for antisemitism] lies quite obviously in the fact that Jews sometimes voluntarily, sometimes involuntarily, came into positions of power, objectively speaking, without, however, wanting this power or even being very much aware of its potentialities.

As we will see, Arendt too felt like Stern that the traditional historical method could no longer be used.

2. Hannah Arendt (1906–1975)

Hannah Arendt (

Figure 2) was born in 1906, sixteen years after Stern. Like Stern, she grew up in an assimilated German–Jewish household, significantly affected by the illness and death of her father. She too was recognized for her extraordinary intellectual talent as a young woman and threw herself into the study of theology, philosophy, and Greek without much concern for Judaism, Jewish history, or Zionism. After her dissertation on the concept of love in Augustine, she began research on Romanticism. She and her first husband Gunther Stern were connected with the University of Frankfurt where he sought to habilitate.

8 By 1930, she had decided to concentrate her study on the salonière Rahel Varnhagen. Through Varnhagen’s struggles with Jewish identity, Arendt was able to historicize and analyze, through a prism, her own struggles as a woman, a Jew, and a German. Arendt quotes Rahel Varnhagen’s following statement as a key to unlocking this history:

The thing which all my life seemed to me the greatest shame, which was the misery and misfortune of my life—having been born a Jewess—this I should on no account now wish to have missed.

Arendt comments:

These are the words…[of] Rahel…on her deathbed. It had taken her 63 years to come to terms with a problem which had its beginnings 1700 years before her birth…and which 100 years after her own death—she died on 7 March 1833—was slated to come to an end. It may well be difficult for us to understand our own history when we are born in 1771 in Berlin and that history has already begun 1700 years earlier in Jerusalem. But if we do not understand it…our history will take its revenge, will exert its superiority and become our personal destiny.

Varnhagen’s struggle with her Jewish identity is presented as the unbearable weight of history, a history, which did take its revenge on Arendt, Stern, and Oelsner. Although made a refugee by this history, Arendt remade herself as a conscious pariah.

Arendt’s manuscript

Rahel Varnhagen: Lebensgeschichte einer deutschen Jüdin aus der Romantik [

Rahel Varnhagen: the Life of a German Jewess in the Romantic Period] was finished in early 1933, but first published in 1957 in English and 1959 in German (

Arendt [1957] 1997,

1959). By that time, Arendt, like Stern, had sharply turned away from women’s history and the “woman question”. Commenting on her own intellectual trajectory, Arendt noted her sharp turn from interest in the category of the German Jewess (

Hahn 2005, pp. 107–8). In 1952, she wrote to Karl Jaspers about her work on Rahel Varnhagen, saying:

this whole project has not been very important to me for a long time, actually not since 1933…because I feel this whole so-called problem isn’t so very important or at least no longer important to me. Whatever of the straightforward historical insights I still consider relevant are contained in shorter form and devoid of all ‘psychology’ in the first part of my totalitarianism book. And there I’m content to let the matter rest.

Arendt would break barriers for women in the academy, but she did not return to write specifically on women’s issues after her study of Varnhagen. Feminist writers of the 1970s and 1980s grasped this. Some strongly critiqued Arendt’s classic on

The Human Condition, published in 1958. Others attempted to rescue elements of her political thought, and still others clarify that her work as an existentialist philosopher did expose the underlying dynamics of “the woman problem”, albeit in a way that did not reinforce a binary social construct. Most recently, Arendt’s “feminine thinking” has been excavated by Yemima Hadad, who focuses on the “sensibilities often associated with the ‘feminine’, but not limited in a binary way”, such as natality (being born and giving birth), in Arendt’s writings on revolution (

Dietz 1994, pp. 231–55;

Markus 1987, pp. 76–87;

Maslin 2013, pp. 585–601;

Arendt 1958;

Hadad 2025).

After 1933, Arendt turned to the study of antisemitism, which grew into

The Origins of Totalitarianism, which in turn led to her work on human rights (

Arendt 2007, pp. 46–121). The shift in Arendt’s interests came with the Nazi rise to power and the impact this had on her own life: her imprisonment by the Nazis, her immigration to France, her work for the Youth Aliyah in Paris, her internment in France, her immigration to New York City, her writing for the New York émigré journal

Aufbau, and her work for the Conference on Jewish Relations and Jewish Cultural Reconstruction.

9 Her ‘Jewish turn’ was a political one. As Richard Bernstein commented, “When Arendt was awakened to the political realities of anti-Semitism, she affirmed her identity as a Jew. It was not Judaism as a religion that attracted her…her Jewish origin had primarily a political significance” (

Bernstein 1996, p. 47). “She was ‘turned into’ a Jew by anti-Semitism”, just as she had once described Theodore Herzl and Bernard Lazare (

Bernstein 1996, p. 47;

Arendt 1942, pp. 236–37). Apart from

Eichmann in Jerusalem:

A Report on the Banality of Evil (1965), her later work was not overtly concerned with Jewish politics or Jewish history. But it did continue to address the political issues that were crystallized for her very personally with the rise of the Nazis and the experience of being a refugee.

Arendt, like Stern, regarded Court Jews as a key component of the history of European Jews. But where Stern saw their Jewish economic function as opening the door to emancipation and acculturation, Arendt saw it as forming a peculiar relationship between Jews and the nation-state, which ultimately generated antisemitism.

Modern antisemitism must be seen in the more general framework of the development of the nation-state, and at the same time its source must be found in certain aspects of Jewish history and specifically Jewish functions during the last centuries.

The focus on Jewish functions took Arendt straight into European Jewish history, even though she eschewed the historical method. Commenting on her methodology in 1946 to Mary Underwood, the editor for

The Origins of Totalitarianism, she wrote: “I kept away from historical writing in the strict sense, because I feel that this continuity is justified only if the author wants to preserve, to hand down his subject matter to the care and memory of future generations. Historical writing in this sense is always a supreme justification of what has happened” (as quoted in

Young-Bruehl 1982, pp. 200–1). Arendt did not want to preserve and justify the objects of her study—antisemitism, imperialism, and racism. But her use of the Jewish economic function did preserve an economic stereotype, despite its originality and sophistication.

Arendt broke down her analysis of Jewish functions into four historical stages linked to the rise and fall of the nation-state. Stage 1: In the 17th and 18th centuries, the nation-state slowly began to develop under the tutelage of absolute monarchies. A few individual Jews rose to the influential position of Court Jews who financed princes and their state affairs. In return, these Jews received special privileges. (Thus far, Arendt’s analysis aligns with Stern’s, but no farther.) Stage 2: Following the French Revolution, political and legal equality were widely proclaimed, but society was still composed of sharply differentiated classes. The new nation-state required large amounts of capital and credit to operate apart from all classes. But the only group who were willing to perform this function were the Jews, and they alone did not fit into class society. This served the new nation-state well. Since the bourgeoisie were uninterested in state finance, the states’ needs were met by the combined wealth of the western and central European Jewry deposited in Jewish banks. In consequence, the privileges once granted to Court Jews alone were extended to the wealthier class of Jews. Finally, emancipation was granted in full-fledged nation-states where Jews’ economic function supported the state. This particular relationship between Jews and the state relied on the indifference of the bourgeoisie to state finance. This changed in Stage 3: With the rise of imperialism, “capitalist business in the form of expansion could no longer be carried out without active political help and intervention by the state” (

Arendt [1951] 1979, p. 15). The bourgeoisie were no longer indifferent to politics and state finance. Jews consequently lost their exclusive position in state business to a group of imperialistically minded businessmen. But Jews continued to serve an important function as inter-European middlemen, who assisted in maintaining the balance of power between nation-states. Stage 4: As imperialist governments replaced nation-states, the western European Jewry was deprived of their former power. Jews as a group disintegrated together with the nation-state before WWI. After the war, the non-national inter-European Jewish element became an object of hatred because of their wealth without power, just as the French aristocracy were during the French Revolution (

Arendt [1951] 1979, pp. 9–28).

Arendt’s analysis applies the paradigm of the Jewish economic function to Court Jews and Jewish bankers from the 17th century through the 19th century. Arendt also politicizes it: Jews fulfilled an economic role in Europe as merchant–moneylenders and bankers, whose credit aided the political development from absolutist ruler to nation-state, and made possible the independence of the nation-state from all classes. Her theory is undergird with the German Historical School’s assumption of Jews’ “age-old experience as moneylenders”. The need for state credit arose together with the expansion of the state’s economic and business interests. But no group in society was willing to grant credit or actively develop state business, except the Jews.

It was only natural that the Jews, with their age-old experience as moneylenders and their connections with European nobility—to whom they frequently owed local protection and for whom they used to handle financial matters—would be called upon for help.

Arendt does not simply adopt the paradigm of the Jewish economic function. She complicates it. Arendt has substituted the European nation-state for the European economy and substituted the bourgeoisie for the Catholic Church. In the classic version of the Jewish economic function as well as Arendt’s politicized version, the Jews were the only group in European society who were willing to perform a function essential for Europe’s historical development—credit. As she wrote in her review of Selma Stern’s Court Jew:

When all attempts to ally itself with one of the major classes in society had failed, the state chose to establish itself as a tremendous business concern…The independent growth of state business was caused by a conflict with the financially powerful forces of the time, with the bourgeoisie which went the way of private investment, shunned all state intervention, and refused active financial participation in what appeared to be an “unproductive” enterprise. Thus the Jews were the only part of the population willing to finance the state’s beginnings and to tie their destinies to its further development. With their credit and international connections, they were in an excellent position to help the nation-state establish itself.

Arendt is cognizant of the paradox that Jews tied themselves to the state because they were aliens, outsiders, who did not have a place in the class system, which structured society. Arendt contends that the state maintained Jews as a separate group, albeit granting them some privileges, because the state required a group separate from society to itself function separately from society and guarantee equal rights. Separation and special rights ran against the ideal of political and legal equality. But the state needed Jews’ financial support. Consequently, the nation-state embodied a fundamental contradiction between the promised political and legal equality and the social inequality embodied in the class system. What was unique about the Jews (in Arendt’s analysis) was that they did not form a class or belong to a class. They were not political. Their status was defined purely through their relationship to the state. Therefore, they became the most obvious target for movements that sought to undermine the nation-state. Paradoxically, Arendt says, “the only non-national European people, [the Jews], were threatened more than any other by the sudden collapse of the system of nation-states” (

Arendt [1951] 1979, p. 22). Although Jews were largely uninterested and even unaware of their political power when joined to the state, non-Jews hated them when their wealth in the imperialist age no longer was justified by their influence and power. This is her explanation of antisemitism! Here, she has provided what Stern did not—a “solution to the whole question of Jewish responsibilities”—at least in her own eyes!

Arendt adopted the narrative of the economic function of the Jews with its presentation of Jews as more monetarily sophisticated than Europeans and its philosemitic, liberal presentation of their financial aid in the development of Europe, for Arendt’s political development. And as in that narrative, resentment leads to antisemitism in Arendt’s. Arendt, however, complicates the ending. Antisemitism is generated not simply by Europeans wishing to take the place of Jews, as the imperialist businessmen do in the nineteenth century. But antisemitism is generated by the close alliance between Jews and the nation-state. “If in the final disintegration, antisemitic slogans proved the most effective means of inspiring and organizing great masses of people for imperialist expansion and destruction of the old forms of government, then the previous history of the relationship between Jews and the state must contain elementary clues to the growing hostility between certain groups of society and the Jews” (

Arendt [1951] 1979, pp. 9–10). While Stern in 1950 was “no longer sure of precisely what the court Jews were forerunners of or where the process of emancipation would eventually lead,” Arendt was!

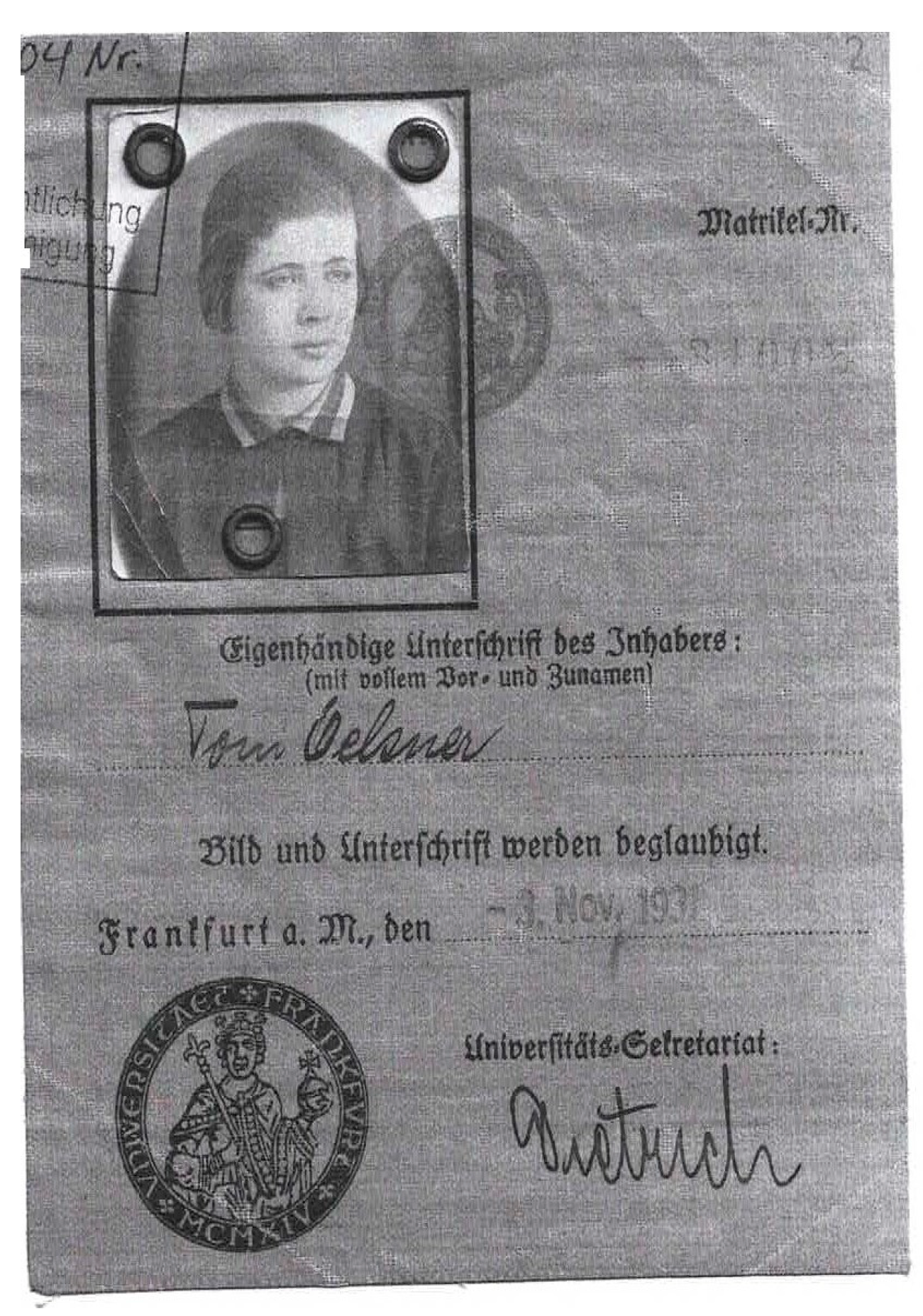

11 3. Toni Oelsner (1907–1981)

Toni Oelsner (

Figure 3) trod many of the same paths that Arendt and Stern traversed.

12 But unlike them, Oelsner received no support for her education. Oelsner’s father, like Arendt’s grandfather, was a member of the assimilationist, anti-Zionist Central Verein deutscher Staats-burger judischen Glaubens. She read Goethe, Schiller, and Heine with her mother, and her father had a copy of Graetz’ three volume

Popular History of the Jews. Oelsner’s intellectual talent was recognized by teachers early on as was Stern’s and Arendt’s, but unlike them, her family did not value a daughter’s education. When a teacher pressed her family to send Toni to the upper division of the Oberrealschule, which would have qualified her for the university, her mother flatly refused, on the basis that they could not afford it. Toni was to be sent only to the lower division, “which would qualify one only as a trainee in a modern industrial, office or technical job.” (One wonders what the response would have been had she been a son.) At the age of 15, Oelsner’s mother died, ending her education.

Her death broke the family ties. It was during the period of inflation, and my family took me out of school before I had finished high school. Without a diploma I couldn’t pursue anything decent. I began working in jobs for which I wasn’t very well suited. Most involved household work, taking care of children and teenagers, working with kindergarten teachers.

But 9–10 years later, Oelsner did begin studying at the Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main. She started in 1931, withdrew, then completed a semester as a non-degree student (

kleine Matrikel) in winter 1932–1933, just as Arendt and Günther Anders left Frankfurt for Berlin (UAF, Abt. 604, Nr. 117, bl. 1–3). Oelsner registered to study philosophy, listing additional interests in history, sociology, religious studies, and Latin (UAF, Abt. 604, Nr. 117, bl. 1v). When she had completed a semester successfully, she was eligible to apply to enter the university as a regular student with the equivalent of a

Begabtenabitur (a combination of a high-school diploma and a university entrance exam). Her application with recommendations from Max Horkheimer, Paul Tillich, and Max Wertheimer was sent off to Berlin on the fateful day of 30 January 1933, when Hitler was appointed Chancellor. By mid-February, Oelsner received a rejection. She was rejected, she said, “because I had recommendations from left-wing Jewish professors, and because I myself was Jewish” (

Oelsner 1986, pp. 102–3). In June 1933, it was decreed that Jews could not acquire the Abitur as an external student, as Oelsner had wished to do (

Oelsner 1986, pp. 102–3). On 7 June 1933, she took a leave of absence, presumably for medical reasons, and she was formally withdrawn from the university on 23 November 1933 (UAF, Abt. 604, Nr. 117, bl. 4–5, 9). During 1933, she was arrested, as was Arendt, and imprisoned for 4 weeks for illegal literature she had kept for another student (

Oelsner 1986, pp. 103–4, 109). However, Oelsner continued attending lectures as a shadow student until 1939 and continued meeting other students in the student canteen. She, like Stern, had access to the libraries until 1938 and continued archival research through 1939.

As with Stern and Arendt, the contemporary political situation and growing antisemitism in the 1930s drew her to the topic of Jewish emancipation. Along with university lectures, Oelsner attended seminars at Rosenzweig’s Freien Jüdischen Lehrhaus [the Jewish House of Free Study] and found a mentor in Josef Soudek, the financial editor of the

Frankfurter Zeitung. (Soudek was a close associate of Karl Mannheim, and Oelsner knew of him from Mannheim’s interdisciplinary seminar on liberalism.) Oelsner was working on the place of Jews in the economic life of Eastern Europe, showing that Jews worked in factories and had unions. Soudek encouraged this work and advised her to use a box of family letters to write something from a sociohistorical perspective. Her new research traced the slow process of Jewish emancipation at the level of multi-generation family history. In 1936, she presented this research to the Jüdischen Frauenbund, and it was published in their journal, as well as in the journal

Jüdische Familienforschung (

Oelsner 1937;

1986, p. 109). This research project eventually appeared in English as “Three Jewish Families in Modern Germany: Studies of the Process of Emancipation” after Oelsner immigrated to New York. Notably, this appeared 1942 in the same issue of

Jewish Social Studies in which appeared Hannah Arendt’s first English article, “From the Dreyfus Affair to France Today” (

Oelsner 1942b;

Arendt 1942).

Oelsner left Germany on 18 August 1939, shortly before war broke out. She took a ship bound for England with a one-week visa to consult with Cecil Roth. When England and France declared war on 3 September, she was required to register as a foreign enemy in London. Karl Mannheim and his wife were just ahead of her in line. She relates:

I spent a couple of hours with him one afternoon, and he became very interested in my work. As a result he wrote some people at the New School that he knew me from the University of Frankfurt and had the impression that I’d made very favorable progress and was especially talented in the area of sociological research. In addition, he said that I had struggled heroically for my intellectual existence in Germany–I was imprisoned in the fall of 1933.

Soon after, she sailed for New York City. She arrived practically broke, but for the 20 dollars the Quakers had given her. As she had nothing to show for seven years of university study, except a transcript with one semester of course work, she received a scholarship only with difficulty for the New School in 1940. But, now in her thirties, with years of study behind her, Oelsner had a rough time. She “didn’t want to study per se. Rather [she] wanted to get involved in research” (

Oelsner 1986, p. 110). She misunderstood the requirements of the American academic system and alienated the professors at the New School. But she did receive her MA in 1942 on the basis of the article that came out in

Jewish Social Studies. Although she did not have many connections with students at the New School, she eventually “made connections with the YIVO Institute and became involved in a circle of historians” (

Oelsner 1986, p. 111). She continued to pursue her research and intermittently received fellowships. She suffered ill health, probably due to malnutrition over the years, and had no support network in New York City. She eked out an existence as a secretary, translator, tutor, and author for encyclopedia articles in the

Germania Judaica and the

Encyclopedia Judaica and for

Aufbau, the German-language journal for which Arendt also wrote. But she never secured an academic position, although she applied to ones all over the US.

Despite these hardships, Oelsner published a series of path-breaking articles on the history of the Jewish ghetto in Frankfurt, a critique of Roscher’s theory of the Jewish economic function, and a comparative analysis of Wilhelm Roscher, Werner Sombart, and Max Weber (

Oelsner 1942a,

1946,

1958–1959,

1962). Her research interests followed a similar course to that of Arendt’s and Stern’s. She worked first on emancipation and family history as Nazi antisemitism was building. But as an émigré, she turned her attention to the issue which forced her emigration—antisemitism. She wrote on the history of the Jewish ghetto in the mid-1940s. And in 1943–1944, she began her research on the Jewish economic function and the German Historical School of Political Economy. These articles would only appear in the late 1950s and 1960s, and her major manuscript on Jewish agriculture in the upper Rhineland in the 13th and 14th centuries remains unpublished today (

Oelsner 1963).

In these works, Oelsner fashioned the first critique of the economic function of the Jews. She argued that the theory “deprived of [its] philo-Semitic and liberal guise could be turned into models for and instruments of the destructive Nazi ‘Jewish Science’” (

Oelsner 1958–1959, pp. 176–77). Oelsner showed how Roscher’s Jewish economic function was rooted in outdated theories of the German Historical School of Political Economy and nineteenth-century German history—notions of universal human progress, stages of economic development from a barter to credit economy, and models of civilizations as organisms following a life cycle from birth to death. Her critique exposes how the changed economic circumstances for both the nineteenth-century German nation and the German–Jewish population helped generate the “optical illusion” that Jews were “naturally gifted for trade”—that Jews were “ the incarnation of the capitalist-commercial spirit” (

Oelsner 1962, pp. 185–86). She deconstructed the image of the Rothschild family as a symbol of power, wealth, and international finance embraced by liberal historians. Oelsner critiqued core concepts central to Stern’s

Court Jews and Arendt’s “non-national European Jews”. Her critique of the Jewish economic function is still necessary today. It opens a new critical perspective on Jewish economic history, which is only slowly being taken up today.

4. Conclusions

This article has focused on three women whose intellectual contributions to the historical paradigm of the “Jewish economic function” have largely gone unnoticed. By using a comparative historical analysis of the biographical and intellectual turns in the early lives of Stern, Arendt, and Oelsner, I have demonstrated the similarities between the women’s biographies of immigration and intellectual directions, as well as the great differences between their intellectual legacies. Focusing on their thought on the ”Jewish economic function” during the 1940s, I have shown how each of these women contributed, adapted, or critiqued this historical paradigm which has predominated since WWII. By placing their intellectual histories within their biographies, this article illuminates the way in which the persecution of religious identity, forcing immigration, shaped historical scholarship.

To summarize, the similarities between these three women are marked: They were all among the first generations of women to attend the university and pursue an intellectual life. They were German Jews who grew up in acculturated families and who maintained their Judaism, without it being central to their lives. But as young scholars, they each explored the historical limits on their own emancipation as women and as Jews. Stern was propelled into Jewish history by the blocks to women attaining an academic position in the 1910s. Arendt and Oelsner turned to Jewish history as they became racialized by Nazi antisemitism. As immigrants, they fled Germany because of the racialization of their religion. They survived the Holocaust during WWII as immigrants in the USA. And they each published important works related to Jewish economic history in the post-war period. The politics behind their emigration led each to grapple with the concept of the Jewish economic function and the figure of the Court Jew—and with the very practice of history itself. Stern applied the Jewish economic function to the early modern Court Jew, making them both the symbol and first pioneers of Jewish emancipation. She was left, however, with a black hole at the center, when her belief in historical progress (i.e., emancipation and acculturation) crumbled in the dust of the Holocaust. Arendt adopted Stern’s Court Jews as the first in a series of four political stages that led to fascism and antisemitism. She politicized the economic function of the Jews, while methodologically eschewing historical practice as justifying the object of study and explained modern antisemitism as the result of Jewish banks and bankers’ economic function in the nation-state. Oelsner dissolved the very concept of the Jewish economic function, rejecting both the stereotype of Jewish economic proclivity and the reification of Jewish difference. In deconstructing an accepted historical “fact”, she never disengaged from historical practice.

These three women also illustrate the range of success and failure for women intellectuals as immigrants in twentieth-century USA. After The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt carried her work forward to deal with the human condition and human rights and became one of the most important political and philosophical thinkers of the twentieth century. She achieved the highest success in her life, which a woman or a man, a Jew or a gentile, could. Her work continues to be widely read and discussed and it is needed even more today with the dark political turn of recent years. As an immigrant, Selma Stern did not receive an appointment in the academy nor achieve fame as Arendt did. But she did create a position for herself as the first archivist for American Jewish history and culture at Hebrew Union College. She continued to carry forward her historical research after writing her novel and left a large legacy that is known and respected by Jewish scholars in early modern German history. Appreciation for her work as a historian and as a pioneering woman scholar is attested by the two monographs published about her in 2004 and 2017. Toni Oelsner stands at the far end of the spectrum. She wrote a series of path-breaking articles and struggled heroically to maintain her research without a Ph.D. or an academic appointment, and without any permanent, well-paid position. She struggled against ill health and financial hardship. She struggled as a woman, as an immigrant, and as a Jew. Yet, it is her work that we need above all when confronting the legacy of ongoing antisemitic stereotypes. Restricted by their gender in intellectual life, targeted for their religion, and forced to become immigrants, these three women struggled intellectually and heroically to understand the forces that led to the ostracization of their religion and build new lives as immigrants.