Abstract

This paper investigates the growing political alignment of Latino Evangelicals with the Republican Party, particularly their support for Donald Trump in the 2020 election. Historically, Latino political behavior has been studied with an assumption of religious homogeneity, largely focusing on the Catholic majority. However, the rise of the Latino Evangelical population has coincided with increasing Latino support for the GOP. Former President Obama attributed this shift in support to the growing Evangelical demographic. Building on Chaturvedi’s (2014) work, which found that Evangelical Latinos’ conservative views on issues like same-sex marriage vary by age, this study tests Obama’s assertion using data from the 2020 USC Dornsife Presidential Poll. Logistic regressions show that older Latino Evangelicals were significantly more likely to support Trump, driven by their desire to elect officials who align with their Evangelical policy preferences. The findings explain that the political behavior of older Latino Evangelicals is more strongly related to religious values compared to their younger counterparts. These results highlight the importance of considering religious diversity within Latino politics, pointing to religious identity as a key factor in shaping Latino political behavior and emphasizing the need for further exploration of religious variation in Latino voting patterns.

1. Introduction

Latinos have deep religious ties that shape their identity, yet the association of religion with Latino political behavior has received limited attention in political science. This gap is particularly notable considering former President Barack Obama’s 2020 claim that the growing number of Latino Evangelicals contributed to increased support for Donald Trump. President Barack Obama (2020) states:

While research on religion and Latino political behavior is still developing, existing studies suggest that religion plays a significant role in shaping partisanship and voter behavior, with Evangelicals of color generally holding more conservative views than their non-Evangelical counterparts (Kelly and Kelly 2005; Wong 2018).“People were surprised about a lot of Hispanic folks who voted for Trump, but there was a lot of Evangelical Hispanics who—the fact that Trump says racist things about Mexicans, or puts detainees, undocumented workers in cages—they think that’s less important than the fact that he supports their views on gay marriage or abortion.”

Churches within the Latino community have long served as civic associations that help boost voter turnout (Jones-Correa and Leal 2001). Additionally, religiosity, especially church attendance, is linked to greater political participation, often driven by the marginalization of underrepresented groups (Harris 1994). Minority churches, particularly those viewed as “political”, have been identified as key sources of civic engagement (Calhoun-Brown 1996).

Despite these insights, little is known about how identifying as an Evangelical specifically influences Latino political behavior. While Evangelicals are generally more conservative than Catholics (Brint and Abrutyn 2010), recent studies show that Catholic voters are becoming more conservative, with their support now more evenly split between Democratic and Republican candidates (Newman 2009). Evangelicals, however, continue to overwhelmingly support Republican candidates (Patrikios 2013; Schwadel 2017; Margolis 2020). What remains unclear is whether this trend holds for the growing population of Latino Evangelicals, who find themselves positioned between the traditionally Democratic and Republican voting blocs.

This study analyzes the voting behavior of Latino Evangelicals using data from the 2020 USC Dornsife Presidential Poll. The findings suggest that Obama’s claim was partially correct: Latino Evangelicals were indeed more likely to vote for Trump over Biden. However, the relationship is more nuanced, as the evidence suggests that while Latino Evangelicals overall favored Trump, younger Latino Evangelicals—those under 45—did not follow this trend (Chaturvedi 2014; Wong 2018). This finding is not surprising, and it provides important insights into the future of Latino politics.

2. Literature Review

2.1. History of Religion and Politics

Political researchers have been fascinated by the association between religion and politics (Scoble and Epstein 1964; Converse 1966; Thompson 1986; Gray et al. 2006; Wald and Calhoun-Brown 2014) since the historic election of John F. Kennedy (Converse et al. 1961). During this time, political scientists were intrigued by the possible impact that Kennedy’s Catholicism may have had on the 1960 presidential vote breakdown (Converse 1966). At first glance, Kennedy appeared to have over-preformed with Catholic voters by garnering 80% of the Catholic vote share in 1960, compared to 50% for Stevenson in 1956. The Protestant vote stayed roughly the same in these two elections, leading many to believe that Kennedy’s religious identity was to thank for his outstanding performance with Catholics. However, after deeper analysis, Converse found that this was not the case. With Eisenhower’s extreme popularity as a WWII hero, he managed to siphon off a large number of traditionally Democratic voters (Scoble and Epstein 1964; Converse 1966; Hyman and Sheatsley 1953), which included a significant number of Catholic and Protestant Democrats. Kennedy merely gained back those Catholics who defected to Eisenhower in 1956. However, Kennedy’s Catholicism did cost him Protestant votes (Converse 1966), as his religious identity acted as a deterrent for traditionally Democratic voting Protestants who voted for Eisenhower due to his war hero status. These findings give way to the notion that religion can have a significant impact on voter behavior, but perhaps not in the way we might expect.

Besides being able to help explain candidate vote choice, religion can also be a driving factor in ideology formation (Morgan and Meier 1980), as it can act as a guide for policy positions. This is especially true for minorities, and it can be illustrated throughout history with Black churches using the pulpit not only to advocate for civil rights (Morgan and Meier 1980; Calhoun-Brown 2000; McDaniel 2008), but also as a mobilizing tool for Black political participation. This can be seen in the Catholic Church, as it has traditionally led the fight against abortion rights (Fleishman 2000; Ferree 2002), and the Protestant Church, which has historically fought for morality-based legislation that includes outlawing gambling and pornography (Lienesch 1982; Rozell and Wilcox 1996).

It has been suggested that religion is largely related to voting more on propositions and referendums than in presidential elections (Hutcheson and Taylor 1973; Fairbanks 1977; Morgan and Meier 1980). Studies have found that Protestants are significantly more likely to support morality-based propositions, such as those related to alcohol and gambling prohibition, with these issues showing weaker relationships with candidate voting. However, these studies primarily focus on White samples, and the findings are more complex when considering racial and ethnic minorities. Research on religious and political engagement within race and ethnic politics has shown that Black churches, and to a lesser extent Latino churches, serve as mobilizing forces to advance the collective interests of these communities (Calhoun-Brown 1996; Barreto et al. 2009; Wald and Calhoun-Brown 2014). Given this, it is reasonable to conclude that if churches influence policy positions and ideological views, they are likely also associated with vote choice.

2.2. Contemporary Politics and the Influence of Religion

When trying to untangle the role of religion in contemporary US politics, researchers have placed an emphasis on the “religion gap” (Olson and Green 2006; Smidt et al. 2010). This term stems from the 2004 election when it was discovered that voters who attended church regularly had a 2-1 propensity to vote for Republican candidates, while those who did not attend church regularly had a 2-1 propensity to vote for Democrat candidates. Candidate religiosity has also been found to play a role, particularly when a candidate’s religious affiliation aligns with their party’s ideology. For example, George W. Bush secured significant support from Evangelical voters, as many aspects of the GOP platform, such as anti-abortion and anti-gay marriage stances, resonated with Evangelical values. This suggests that, in some cases, policy positions influence voters more than a candidate’s religious identity (Marti 2019; Margolis 2020).

This was exemplified in 2016, when we saw significant Anglo Evangelical support for Trump, as a large number of White Evangelicals viewed Donald Trump as the best choice given his policy stances rather than personal religiosity, which could be argued was nonexistent (Gorski 2017). These voters justified their support for Donald Trump by arguing that he represented their best chance for achieving Evangelical-oriented policies. While many initially saw him as the “lesser of two evils”, a significant portion eventually came to view him as their ideal candidate (Gorski 2017; Whitehead et al. 2018). This group of Trump supporters has also been found to endorse Christian nationalist policies, seeing their vote for Trump as an expression of their faith and a means of preserving American Christian values (Whitehead et al. 2018). However, it remains unclear whether this belief was predominantly held by White Evangelicals or if it extended to Evangelicals of all racial and ethnic backgrounds.

As noted earlier, the Evangelical population is growing among non-White groups, with approximately 25% of Evangelicals now coming from racial and ethnic minorities. Roughly 14% of Latinos identify as Evangelical (PRRI 2021). However, support for Donald Trump in 2016 was considerably lower among these groups (Gorski 2017). Gorski (2017) and Whitehead et al. (2018) point out that the lack of minority support is a key reason why the term “White Christian nationalism” is frequently used to describe radical Trump supporters. This is further evident in the fact that most ethnic and racial minorities voted for Clinton in 2016. While these studies offer valuable insights into the role of religion, they should be viewed with some caution when trying to fully understand its role within the U.S. electorate. The reason for this is that while the studies acknowledge that minority Evangelicals, despite their growing numbers, do not mirror the political behavior of their White Evangelical counterparts, they provide limited discussion of why this may be the case.

Most of these studies only provide descriptive statistics to simply show that most Evangelicals supported Trump, apart from minorities. They do not parse out the potential differences among these Evangelical minority groups (see Wong (2018), as she does separate by race/ethnicity). They go on to explain why White Evangelicals supported Trump, but not why or which minority Evangelicals did not. By grouping all minority groups together (Gorski 2017; Whitehead et al. 2018), we remain in the dark about how Latino Evangelicals voted. This is in part because it can be difficult to explain minority vote choice, especially Latino vote choice (Hero 1992; Jones-Correa and Leal 2001; Monforti and Sanchez 2010). Regardless, we were unable to use this information to assess whether President Obama’s premise that a significant chunk of the Latino electorate supported Trump due to their Evangelicalism is accurate.

2.3. Latinos, Religion, and Voting Behavior

Research on religion’s role within the Latino community highlights a significant divide between traditionally Catholic Latinos and the rapidly growing Evangelical Latino population (Ellison et al. 2011; Kelly and Kelly 2005). Ellison et al. (2011) found that Latinos are more likely to view churches as sources of information, making them influential in shaping political behavior. However, Evangelical Latinos appear to be more affected by church attendance than their Catholic counterparts (Kenski 1995; Lockerbie 2013). Studies indicate that Protestant/Evangelical Latinos not only differ from Catholics but also tend to hold more conservative views, particularly when they are regular churchgoers (Ellison et al. 2011; Bartowski et al. 2012; Chaturvedi 2014; Jones-Correa et al. 2018).

Martinez and Martí (2024) argue that increased church attendance contributed to Latino Evangelicals’ growing support for Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election. While their work provides valuable insights, focusing on church attendance alone may not fully capture the complexity of Evangelical Latino political behavior. Given that only 36% of millennials belong to a church—significantly fewer than Baby Boomers—and 49% of U.S.-born Latinos aged 18–29 are religiously unaffiliated (Gallup 2021), it is important to also consider the broader role of Evangelical identity itself. Before examining how regular church attendance shapes political engagement, it is necessary to explore whether simply identifying as Evangelical—regardless of attendance—contributes to distinct voting patterns among Latinos. These patterns often align with opposition to gay marriage, pre-marital cohabitation, and support for pro-life abortion stances. Although it remains unclear whether denomination alone drives these differences, it is evident that, unlike White Evangelicals, Latino Catholics and Evangelicals hold notably divergent political and social beliefs.

The relationship between these differences in social views and vote choice is more complex. While Latino Evangelicals are known to hold more conservative positions on issues like same-sex marriage (Chaturvedi 2014; Jones-Correa et al. 2018), the shift in voting behavior is not straightforward. For example, Chaturvedi (2014) found that identifying as Evangelical makes Latinos significantly more likely to oppose same-sex marriage. However, this tendency is less pronounced among younger individuals and second-generation or later immigrants. Jones-Correa et al. (2018) support this by showing that, in addition to age, generational status plays a crucial role in shaping political behavior, particularly party affiliation. First-generation Latino immigrants tend to identify with the Democratic Party at a 2:1 ratio, with this margin growing to 3:1 in later generations. Given these findings, it is reasonable to suggest that generational differences may be associated with vote choice among Latino Evangelicals.

When looking directly at the political attitudes of Evangelical Latinos, Wong (2018) found that this group is much more conservative than non-Evangelical Latinos, and Evangelical Black Americans. She went on to show that while Evangelical Latinos are less conservative than White Evangelicals, this group still voted for Republicans and held conservative positions at substantial rates (Wong 2018).

2.4. Explaining the Latino Vote

While a segment of Latinos vote for the GOP candidate, the majority continue to support the Democratic ticket. This trend is not surprising, as Latino and Black voters tend to follow a different model of political behavior compared to White voters. Unlike White voters, who generally align with the Michigan School of voting behavior (Converse et al. 1961), Black and Latino voters more closely follow what Dawson (1994) describes as a Dawsonian model of voting.

The Michigan School of Voting Behavior emerged from the University of Michigan’s Survey Research Center, pioneered by Campbell (1960). This model posits that party identification is primarily acquired through family socialization, with political loyalties formed in youth often persisting throughout life. Rooted in social identity theory, this model suggests that individuals have a natural inclination to belong to a group, reinforcing partisan attachments over time (Sarlamanov and Jovanoski 2014). Among Latinos, this sense of belonging is further shaped by a shared ethnic identity, which has historically been a powerful mobilizing force. For example, regardless of nativity, immigration status, generation, or age, Latinos across diverse backgrounds participated in the 2006 immigration rallies, demonstrating how ethnic solidarity can drive political engagement (Barreto 2007a).

Building on Anthony Downs’s (1957) Economic Theory of Voting—which argues that voters act as rational agents seeking to maximize personal utility using spatial voting—Dawson (1994) expanded this framework to account for group-based decision-making. In Behind the Mule, he introduced the concept of the “Black utility heuristic”, where African Americans make political decisions based on what benefits their community rather than solely individual self-interest. This idea, known as linked fate, suggests that individuals within a racial or ethnic group perceive their destinies as interconnected—what happens to one member of the group impacts them all. Linked fate continues to shape Black political behavior through social pressure and community norms (White and Laird 2020).

Applying this framework to Latino voters helps explain why many support the Democratic Party, which is often seen as more progressive on issues affecting their community (Pachon and DeSipio 1992; Arvizu and Garcia 1996; De la Garza and Cortina 2007; Barreto 2007b; Barreto et al. 2010). However, while linked fate plays a role in Latino political behavior, it does so to a significantly lesser extent than among Black voters. This distinction is evident in voting patterns: in 2020, over 90% of Black voters supported Joe Biden, compared to approximately 65% of Latino voters (Dominguez-Villegas et al. 2021). While many Latinos follow the Dawsonian-like spatial model, a significant minority do not. Who makes up this minority?

One plausible explanation is the growing Evangelical Latino population, which may help predict why certain Latinos support the GOP. The following sections of this article will present the theoretical framework and empirical findings that highlight Evangelical identity as a key predictor of Latino support for Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election. However, as Chaturvedi (2014) notes, this relationship is also shaped by age, suggesting that the influence of Evangelical identity on political preferences varies across generations.

3. Theory

Latinos have a distinctive relationship with religion, with the Catholic Church traditionally playing a central role (Barreto et al. 2009). However, the Evangelical church has increasingly swayed Latino public opinion, particularly on social issues (Chaturvedi 2014; Wong 2018; Schwadel 2017), and is associated with more political power than the Catholic Church in certain contexts. For instance, during the 2006 immigration protests, the Catholic Church had to explicitly frame HR 4437 as a Latino issue, emphasizing ethnicity in order to galvanize action. In contrast, simply identifying as Evangelical has been shown to be enough to shape negative views toward same-sex marriage among Latinos (Chaturvedi 2014; Wong 2018). This suggests that Evangelical beliefs may more directly and powerfully impact the shaping of certain political attitudes.

Many may question how this trend is possible given the GOP’s anti-Latino rhetoric, but it is understandable. Despite the harsh language surrounding immigration, Trump and the Republican Party gained traction among Latino voters in both 2016 and 2020. This shift can be explained by the weakening of ethnic ties among some Latinos, coupled with their recognition of their group’s subordinate social status, which made them more receptive to strict immigration rhetoric (Hickel et al. 2020). For these voters, the immigrant identity did not strongly resonate, making it easier for them to support tougher immigration policies (Hickel et al. 2020).

Additionally, as more Latinos distanced themselves from the immigrant label, the Republican Party found new opportunities to appeal to them through economic and social messaging that aligned with Evangelical values. According to Wakefield (2025), Latino Republicans and right-leaning independents responded favorably to moderate economic messaging from GOP candidates. While immigration policy remained a contentious issue, economic and social priorities—such as opposition to socialism and abortion—played a more significant role in shaping Latino political behavior, further driving this shift (Wakefield 2025).

This paper argues that while a Dawsonian-like spatial lens is often appropriate for analyzing Latino political behavior, it is not sufficient in this context. Instead, this study builds on the findings of Chaturvedi (2014) and Wong (2018), which offer a more precise framework for understanding the political implications of Latino Evangelical identity. Their work highlights how Latino Evangelicalism fosters more conservative political attitudes, increasing the likelihood of Latino Evangelicals voting for Republican Donald Trump over Democrat Joe Biden.

The rise of Latino Protestantism can be traced to a sense of religious displacement, as many Latinos felt disconnected from the Catholic Church and sought a more personal relationship with God (Ramos et al. 2018). Protestantism, particularly Evangelicalism, facilitated a deeper integration of faith into daily life, leading many Latinos to prioritize their religious identity over their ethnic background (Ramos et al. 2018). Furthermore, Evangelicalism is often associated with patriarchal values and aspirations for upward social mobility, which, in turn, align Latino Evangelicals with broader conservative and Christian nationalist ideologies (Ramos et al. 2018; Marti 2022; Martinez and Martí 2024). The adoption of white Evangelical identity and ideology provides a framework through which Latino Evangelicals internalize and advocate for traditional social, political, and economic values, reinforcing a sense of belonging within a dominant cultural framework (Rozell 2018; Marti 2022; Martinez and Martí 2024).

By applying Chaturvedi’s framework, this paper demonstrates that Latino Evangelicals were more likely to support Trump in 2020, as his policy positions resonated more closely with their conservative values compared to those of other Latino voters (Wong 2018). However, consistent with Chaturvedi’s findings, this association between Latino Evangelical identity and conservative political behavior is not uniform across all age groups. Specifically, the influence of Evangelical identity on political preferences is significantly weaker among younger Latinos.

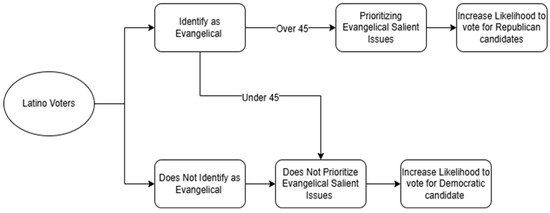

As illustrated in Figure 1, the overarching theory posited here aligns with existing literature: the majority of Latinos are more inclined to support the Democratic candidate, as Democrats are generally perceived as better representing Latino interests. However, the model also suggests that Latino Evangelicals are more likely to vote for the Republican candidate whose platform aligns more closely with Evangelical priorities. Crucially, this relationship is moderated by age, with Evangelical identity having little to no significant impact on political behavior among younger Latinos. Thus, this paper posits the following theory, also visually represented in Figure 1: Latino non-Evangelicals will prioritize Latino-centric issues when casting their votes (De la Garza and Cortina 2007; Barreto 2007b; Barreto et al. 2010), whereas Latino Evangelicals will be more likely to prioritize issues central to Evangelical ideology. However, this effect is mitigated by age, as younger Latino Evangelicals exhibit political behavior that is more similar to their non-Evangelical co-ethnics.

Figure 1.

Evangelical Latino voting theory1.

4. Hypotheses

This paper claims that Evangelical identity is associated with Latino vote choice, illustrating a political behavior that reflect broader patterns of religiosity and party alignment. Drawing on existing literature that suggests that Evangelicals tend to hold more conservative views, particularly on social issues, this researcher hypothesizes that identifying as a Latino Evangelical will be associated with support for Republican candidates, particularly Donald Trump. Using data from the 2020 USC Dornsife Presidential Poll, this research aims to address the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

Latinos were significantly more likely to cast their vote for Joe Biden in the 2020 Presidential Election.

Hypothesis 2.

Evangelical Latinos were significantly more likely to cast their vote for Donald Trump in the 2020 Presidential Election.

Hypothesis 3.

Younger Evangelical Latinos were not significantly more likely to cast their vote for Donald Trump in the 2020 Presidential Election.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Data/Variables and Measurement

This study was conducted using data from the 2020 USC Dornsife Presidential Poll. This poll was done through the USC Dornsife Center for the Political Future, and it was used as the official poll of the Los Angeles Times during the 2020 presidential election. It is important to note that this election survey was also part of a larger study called the Understanding America Study/Survey2 (UAS), which focused on COVID-19 and other nonpolitical issues. Participants were gathered by inviting roughly 8000 eligible voters, who were already active members of the USC Understanding America Study, to participate in an ongoing survey on the 2020 election. Roughly 96% of those invited agreed to participate every other week on an assigned day, leading to 6498 respondents, with a subsample of 532 Latino participants.

Like many national election polls, this survey was fielded in waves from mid-August to mid-November; however, this study will use the post-election poll to garner the most accurate results regarding vote choice. The post-election poll was an extensive post-mortem survey meant to understand actual vote choice and the reasons behind said vote choice. This polling data are highly appropriate for this study for several reasons. The first is that this survey has a significant number of Latinos, which allows for generalizable correlative results. This is key given that not many surveys are able to garner a large enough sample size to make generalizable claims about the U.S. Latino population (Barreto et al. 2018; Frasure-Yokley et al. 2020). Second, to further correct for any sampling error or generalizability issues, this survey and the subsample of Latinos has been weighted accordingly, to allow for an even greater degree of certainty. Lastly, this survey is ideal, as it asks specific questions regarding the role of religion in political attitudes. This allows for an analysis of any possible association between being Evangelical and presidential vote choice.

5.1.1. Presidential Vote Choice

As mentioned above, this study will utilize a post-election survey that asks respondents which candidate they cast their vote for in the 2020 Presidential Election. Originally, this question included all candidates listed on the ballot, which included a choice for Joe Biden, Donald Trump, Howie Hawkins, Joe Jorgensen, and “other”. However, for the sake of this study, this question was recoded to only include those who chose either Donald Trump (coded as “0”) or Joe Biden (coded as “1”), while dropping the other observations. This was done for three main reasons. The first is methodological, as less than 2% of Latinos voted for these candidates in total, so including these individuals did not seem necessary, and while some may argue that it is necessary to include these cases, they would do nothing more than act as outliers that would not add to the understanding of the role of being Evangelical on Latino voting behavior. This leads to the second reason, which is that this study is meant to understand whether Latino Evangelicals were more likely to vote for the GOP candidate, meaning that there is no need to include third-party candidates. With this in mind, this research utilizes the recoded vote choice variable as the dependent variable in several regressions that will follow in the Methods section.

5.1.2. Evangelical

Like many political surveys, the USC Dornsife Presidential Election Poll asked several questions regarding demographics, two of which happened to be about religious affiliation. One asked respondents to report their religious affiliation and listed two different choices for Christianity—Catholic and Protestant (USC Dornsife Presidential Poll 2020). The other asked if respondents identified as “Evangelical or Born Again”, which was coded as a binary (0/1 for no/yes). It is important to note that lumping the terms “Evangelical” and “Born-again” can be problematic in political polling, as Americans who claim the latter often differ politically and religiously from their Evangelical counterparts (Margolis 2022; Smidt 2022; Allen 2024). Furthermore, the Evangelical label has been rejected by many self-identifying born-again individuals due to its over-politicization and linkages to the Republican party (Margolis 2022; Smidt 2022; Allen 2024). However, building off the work of Wong (2015), Latino born-again Evangelicals do not differ politically due to the gradual alignment with the Republican party. Although it is much more pronounced among their white counterparts, Latino born-again Evangelicals tend to have conservative views, such as opposition to same-sex marriage, revealing that the born-again Evangelicals politically behave in similar patterns; therefore, it is appropriate to combine the identities (Wong 2015).

This paper will focus on the latter question, which is more appropriate for this study, as it does not focus on Protestant Latinos as a whole, but specifically on those who identify as Evangelical. Furthermore, the binary measurement used for the Evangelical question allows one to clearly observe the relationship between identifying as Evangelical and vote choice (Chaturvedi 2014).

5.1.3. Party Affiliation

While the focus of this study is to analyze the role that identifying as Evangelical plays in presidential vote choice, it is always important to account for party identification for several reasons. Converse et al. (1961) showed that one of the strongest predictors of vote choice is party affiliation. This has been shown to hold up over time, and research has even shown that it is not only party registration status that can predict vote choice, but party affiliation (Barnes et al. 1988; Petrocik 2009; Gerber et al. 2010). This is different from registration status, as it asks respondents to report the party that they feel closest to rather than asking which party they belong to (Greene 1999; Petrocik 2009). For these reasons, the paper includes party affiliation in the logit models and is expected to be a rather strong predictor. It is measured as a binary, with those who reported an affiliation with the GOP coded as 0, and those who affiliate with the Democratic Party being coded as 1. Unlike Wong’s (2018) prior findings, the party is expected to be rather meaningful. Furthermore, it is important to note that ideology was left out of this study, as it caused issues of collinearity given its strong correlation with party identity when initially included in the model.

5.1.4. Immigration Status

When it comes to Latino politics, it is important to account for immigration status, as roughly 72% of Latinos are either first- or second-generation immigrants (López et al. 2017). This common bond among Latinos is also a determinant of vote choice, as it has been demonstrated by Jones-Correa et al. (2018) that Latinos who are first-generation immigrants significantly differ from other generations when it comes to voting, with there being only a 2-1 likelihood of voting for the Democratic Party. In turn, the second generation and beyond are more likely to vote for Democrats at a 3-1 margin. Therefore, a 4-point measure of immigration status is included, which begins at 1 for first-generation immigrants and ends at 4 for fourth generation and beyond/non-immigrant.3 This is ideal as it allows me to account for the unique experiences of second- and third-generation immigrants, whereas a binary measurement would not accurately capture the differences between second-generation Latino immigrants and those whose ancestors resided in the southwest when it was ceded to the U.S. via the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (Castillo 1992).

5.1.5. Control Variables—Education, Age, and Gender

Aside from the primary independent variable, there are several control variables, one of which is education. It is key to include education, as it has been found to be a major predictor in voting behavior, with education being shown to make individuals more politically sophisticated, which translates into a greater likelihood to vote (Luskin 1990; Sondheimer and Green 2010; Dun and Jessee 2020). While little relationship has been shown between education and vote choice, it is best to include to avoid omitted variable bias (Clarke 2005; Gschwend and Schimmelfennig 2007). Education is measured on a 14-point scale where respondents select the highest level of education they have attained, with the lowest value being 5th/6th grade completion and the highest being a doctoral degree.

The other demographic control variables included in the models are age and gender (Pollock and Edwards 2019). For age, respondents are divided into two key groups: those 45 and under, classified as “younger”, and those over 45, classified as “older”. A binary variable is created, coded as 0 for younger respondents and 1 for older respondents, to better capture potential generational divides. Gender is also coded as a binary with women coded 0, and men coded as 1.4

5.2. Methodology

Using these variables, several binary logistic regression models were created in STATA to analyze how identifying as Evangelical links to vote choice. Before getting to these models, there is a breakdown of general and Latino vote choice in the 2020 election in Table 1 and Table 2. As one can see, roughly 65% of Latino voters cast their ballot for Joe Biden, while about 32% voted for Donald Trump. This shows that a rather large majority of Latinos supported Biden, while a sizable minority went for Trump. To understand the association of being Latino on vote choice, one can see Appendix A, where a model that includes all respondents who voted in the 2020 Presidential Election, and it includes Latino as a variable to show that being Latino was a significant predictor of casting a vote for Joe Biden.

Table 1.

Effects of Being Evangelical on Latino Vote Choice.

Table 2.

Interaction of Religion and Age on Latino Vote Choice.

To explore the relationship between Evangelical identity and Latino vote choice, several binary logistic regressions were conducted, focusing solely on Latino respondents. Table 1’s model examines whether identifying as Evangelical is associated with voting for Donald Trump. This model incorporates various variables, including party affiliation, age, and education level, to assess their effects on vote choice.

Table 2’s model goes on to examine whether the relationship between Evangelical identity and vote choice varies by age. Specifically, interaction terms were used to assess whether the combination of Evangelical identity and age produces significantly different outcomes (Brambor et al. 2006). Additionally, interaction terms for gender and Evangelical identity were included to investigate whether gender plays a role in shaping Latino vote choice, drawing on insights from previous research (Monforti 2017; Junn and Masuoka 2020). These interaction models allow for a more nuanced understanding of how Evangelical identity, in combination with other demographic factors, shapes Latino political behavior.

6. Results

As mentioned above, initial analysis of the general public reveals that identifying as Latino was a significant predictor of voting for Joe Biden. This finding highlights the importance of Latino identity in shaping political behavior, with Latinos more likely to support Biden. The subsequent models build on this foundation by looking more closely at the role of Evangelical identity, age, gender, and other key variables in determining Latino voting patterns. Table 1’s model confirmed Hypothesis 2 by demonstrating that identifying as Evangelical—independent of party affiliation—was a strong predictor of Latino vote choice. The results indicate that Latino Evangelical respondents were significantly more likely to vote for Donald Trump compared to their non-Evangelical counterparts. This finding underscores the distinct political behavior of Latino Evangelicals, suggesting that their religious identity plays a pivotal role in shaping their political preferences, separate from traditional partisan attachments.

One possible explanation for this pattern is the alignment between Evangelical values and key aspects of Trump’s platform, particularly on issues such as abortion, religious freedom, and opposition to progressive social policies. Previous research (Martinez and Martí 2024; Ramos et al. 2018) suggests that Evangelical communities foster strong in-group cohesion and political messaging that emphasizes conservative moral and social values. This could explain why Latino Evangelicals, despite belonging to a racial/ethnic group that traditionally leans Democratic, were drawn to Trump’s candidacy.

Furthermore, this finding raises important questions about the evolving role of religious identity in Latino political behavior. This suggests that for Latino Evangelicals, faith-based concerns may outweigh ethnic or racial group interests when making political decisions. This aligns with previous scholarship (Wong 2018; Chaturvedi 2014) that highlights how religious identity can serve as a cross-cutting cleavage within racial and ethnic communities, influencing vote choice in ways that diverge from broader group trends.

The strength of this correlation also speaks to the growing influence of Latino Evangelicals as a distinct political constituency. As the Latino Evangelical population continues to expand, particularly in states with competitive elections, understanding the extent to which religious identity influences political decision-making will be crucial for forecasting future electoral trends.

Further analysis in Table 2’s model revealed that the interaction5 between age and Evangelical identity did not yield significant results, indicating that while Latino Evangelicals overall were more likely to vote for Trump, this pattern was not as evident among younger Evangelicals. These findings align with Chaturvedi’s (2014) research, which highlights generational differences in the political behavior of Evangelical Latinos, suggesting that while Evangelical identity is associated with more conservative political preferences, this relationship appears weaker among younger cohorts.

This trend is consistent with broader patterns in political behavior, where younger generations tend to exhibit more progressive attitudes compared to older ones (Hooghe 2004; Dalton 2015). Factors such as generational shifts in social norms, increased exposure to diverse political perspectives, and evolving attitudes toward issues like immigration, race, and LGBTQ+ rights may contribute to this divergence within the Latino Evangelical population. Additionally, the political socialization of younger Latino Evangelicals may be shaped by distinct contextual influences, such as growing up in a more secularized society or being exposed to different forms of religious engagement compared to older generations.

These findings suggest that while Evangelical identity remains an important factor in shaping Latino political behavior, its influence may be mediated by generational differences, indicating a more complex relationship between religion, age, and political preferences.

Lastly, a particularly noteworthy finding is the comparison between the Latino community and the general public, as several models of the general public6 indicate that Evangelical identity is a more prominent factor in shaping political behavior among Latinos than among the broader electorate. This holds true in both the interaction and non-interaction models, further reinforcing the idea that Latino Evangelicals are more influenced by their religious affiliation compared to the average American voter (Barreto et al. 2010). This finding is especially significant given that while Latinos have long been recognized as a highly religious group, this religiosity has traditionally been attributed to Catholicism rather than Protestant or Evangelical affiliations. The detailed results for all models can be found in Appendix A.

Additionally, a replication using ANES time-series data reveals that the interaction between being younger and identifying as Evangelical is not associated with a vote for Trump, but instead correlates with support for Biden, aligning with previous findings by Chaturvedi and supporting the hypothesis. This replication, detailed in the appendices, provides further evidence of generational differences in the political behavior of Latino Evangelicals.

7. Discussion

This study underscores the significant association of Evangelical identity with Latino vote choice, especially in the context of the 2020 election. Building on the work of Peterson and Brown (2005), who demonstrated that Evangelical identity is a significant predictor of vote choice, the present analyses further reveal that, even when controlling for the interaction of age and Evangelical identity, religious affiliation remained the second strongest determinant of Latino voting behavior following party affiliation. This finding emphasizes the need for a more nuanced approach to Latino political behavior that incorporates religious identity.

One of the key insights from this study is the distinctive voting patterns of Latino Evangelicals, particularly those who are older (over 45 years old). These voters were significantly more likely to support Donald Trump and, by extension, GOP candidates. This support was not driven by nationalism or cultural alignment, as is often the case with White Evangelicals, but rather by a strategic calculus to elect politicians who would enact policies aligned with their deeply held Evangelical values. Despite Trump’s personal behavior often contradicting Evangelical moral teachings, older Latino Evangelicals focused on his policy positions, such as anti-abortion stances and conservative religious freedom protections, which resonated more strongly with their faith-driven priorities than his personal shortcomings.

This finding echoes Wong’s (2018) research, which demonstrated that Latino Evangelicals were more likely to support Trump than their non-Evangelical counterparts. However, the present study complicates this picture by showing that younger Latino Evangelicals did not exhibit the same trend, suggesting that their vote choice was swayed by factors beyond religious identity alone. This nuance is important because it challenges the simplistic notion that Evangelicalism uniformly shapes Latino political behavior and highlights the role of age and generational shifts in political alignment.

In addition to testing President Barack Obama’s (2020) claim that Latino support for Trump was driven largely by Evangelical voters, this study emphasizes that the religious diversity within the Latino community must be considered more seriously in future research. Historically, Latinos have often been treated as a monolithic group, with much of the literature assuming a Catholic majority and downplaying the political significance of Evangelical Latinos (Schmidt et al. 2000; Barreto et al. 2010; McKenzie and Rouse 2013). However, the growing population of Latino Evangelicals, particularly those who are older and more politically active, calls for a reevaluation of this assumption.

The study’s findings also point to a broader gap in the literature regarding Latino Evangelical political behavior. Researchers have often overlooked the distinct political behaviors of Latino Evangelicals, assuming that all Latinos share a similar religious orientation or political outlook. This study, along with recent work by Chaturvedi (2014), Wong (2018), and Sherkat (2017), illustrates that older Latino Evangelicals exhibit clear political differences from their Catholic and non-Evangelical peers, particularly in their voting behavior and policy preferences.

While we are post-2024 election, we do not have data to confirm that these results carry over to this contest. However, given the recent history of presidential elections discussed by Tesler (2013), it is assumed that the 2024 election is not linked as strongly to being Evangelical. We see that in the 2012 election of Barack Obama, demographic considerations were less central to American voting behavior than the economy (Tesler 2013), which is opposite of what was seen in 2008. In the 2024 election, it was expected that the perceptions of the economy would supersede other predicators.

Ultimately, this research stresses the critical importance of considering religious identity, particularly Evangelical affiliation, when analyzing Latino political behavior. With the rapid expansion of the Latino Evangelical population (Ellison et al. 2011; Reyes-Barrientez 2019), it is essential for future studies to account for religion’s role in shaping voting patterns, political ideologies, party identification, and other forms of political engagement. The increasing power of Latino Evangelicals in U.S. politics suggests that religion will continue to be a powerful factor in shaping the future of Latino political behavior and that research must adapt to capture this growing segment of the community.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health and in part by the Social Security Administration under Award Number U01AG077280. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The UAS protocol received approval from the University of Southern California (USC) Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent. Data were collected, stored, managed, and analyzed in a fully anonymized manner. Since we used de-identified, publicly available data, this study qualifies as non-human subjects research under the NIH definition.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data referenced in this article is publicly accessible through the University of Southern California’s Understanding America Study (UAS). The author utilized the “UAS 318” survey for analysis. Interested researchers can access the dataset by creating a free account at the UAS data portal: https://uasdata.usc.edu/index.php.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Donovan Wright and William Haden from Cal Poly Pomona for all their help as research assistants for this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

This appendix provides additional empirical support for the findings discussed in the main text. Included in this section is a breakdown of the 2020 presidential vote, along with regression models that reinforce key results and discussions.

- Model A examines the relationship between Latino identity and vote choice, demonstrating that being Latino was significantly associated with voting for the Democratic candidate.

- Model B replicates Model 1, extending the analysis to the general electorate to assess the broader impact of Evangelical identity on vote choice.

- Model C replicates Model 2, analyzing the interaction between age and Evangelical identity to further explore generational differences in political behavior.

- Lastly, Model D and Model E are replications of Model 1 and Model 2 using ANES data and provide an additional robustness check, ensuring the validity of the findings across different datasets.

These models collectively reinforce the study’s central arguments, offering a deeper understanding of the relationship between religious identity, age, and Latino political behavior.

Appendix A.1. Vote Breakdown

Above is a breakdown of the overall 2020 presidential vote, as well as a specific breakdown of the Latino vote. The data confirm that Latinos were significantly more supportive of Biden than Trump; however, a sizable minority still cast their vote for Trump. This variation in Latino vote choice highlights the complexity of political behavior within the community, underscoring the need to examine factors such as religion and age to better understand these patterns.

Table A1.

2020 Presidential vote.

Table A1.

2020 Presidential vote.

| JOE BIDEN | 51% |

| DONALD TRUMP | 47% |

Table A2.

2020 Latino vote.

Table A2.

2020 Latino vote.

| JOE BIDEN | ~65% |

| DONALD TRUMP | ~32% |

Appendix A.2. The Impact of Latino Identity

Below is a regression model demonstrating that simply identifying as Latino is significantly associated with voting for the Democratic candidate. This finding highlights the powerful role that identity plays in shaping political behavior, as it suggests that partisan preferences are often deeply rooted in shared social and cultural experiences. The strong correlation between Latino identity and Democratic vote choice aligns with the existing literature on group-based voting, which emphasizes that individuals often align with political parties that they perceive as representing their community’s interests and values.

This pattern lends credence to the broader argument that identity-based affiliations—such as religion—may also significantly influence vote choice. Just as Latino identity remains a strong predictor of Democratic support, identifying as an Evangelical may be similarly correlated with political behavior, potentially pushing individuals toward more conservative candidates. This underscores the necessity of examining religious identity alongside ethnic identity to fully understand the nuances of Latino political preferences. By exploring these intersections, we gain deeper insight into how different aspects of identity shape electoral decisions, revealing both continuity and divergence within the Latino electorate.

| Regression Showing Latino as a Variable | ||||

| Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p > z | |

| Evangelical | −0.739 | 0.253 | −2.92 | 0.003 ** |

| Education | 0.234 | 0.061 | 3.84 | 0.000 *** |

| Party Affiliation | 7.206 | 0.287 | 25.12 | 0.000 *** |

| Immigrant Generation | −0.136 | 0.105 | −1.30 | 0.194 |

| Latino | 1.004 | 0.368 | 2.73 | 0.006 ** |

| Constant | −5.635 | 0.771 | −7.31 | 0.000 *** |

| Pseudo-R2-squared | 0.14 | |||

| Model A | ||||

| * = Significant at 0.05; ** = Significant at 0.001; *** = Significant at 0.000. | ||||

Appendix A.3. Comparing to the General Population

Below are replications of Models 1 and 2 using the entire sample, which allow for a direct comparison between Latino political behavior and that of the general electorate. These models demonstrate how Latino behavior is distinct, particularly in terms of religious identity and its influence on vote choice. By using a broader sample, we can examine the extent to which factors such as Evangelical identity are more pronounced within the Latino community compared to the general public. This comparison highlights the unique ways in which identity, both ethnic and religious, shapes political preferences in the Latino community.

| Looking at the General Population (Without Interactions) | ||||

| Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p > z | |

| Evangelical | −0.831 | 0.243 | −3.41 | 0.001 ** |

| Age | 0.768 | 0.250 | 3.07 | 0.002 ** |

| Education | 0.134 | 0.052 | 2.58 | 0.010 * |

| Party Affiliation | 6.936 | 0.261 | 26.61 | 0.000 *** |

| Immigrant Generation | −0.0140 | 0.122 | −0.11 | 0.909 |

| Gender | −0.0012 | 0.234 | −0.01 | 0.995 |

| Constant | −4.754 | 0.789 | −6.03 | 0.000 *** |

| Model B | ||||

| * = Significant at 0.05; ** = Significant at 0.001; *** = Significant at 0.000. | ||||

| Looking at the General Population (With Interactions) | ||||

| Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p > z | |

| Evangelical | −0.585 | 0.398 | −1.47 | 0.142 |

| Age | 0.770 | 0.316 | 2.44 | 0.015 * |

| Evangelical * Age | 0.037 | 0.487 | 0.08 | 0.940 |

| Education | 0.134 | 0.052 | 2.56 | 0.010 * |

| Party Affiliation | 6.944 | 0.262 | 26.55 | 0.000 *** |

| Immigration Gen | −0.014 | 0.123 | −0.11 | 0.909 |

| Gender | 0.209 | 0.306 | 0.68 | 0.495 |

| Gender * Evangelical | −0.514 | 0.475 | −1.08 | 0.279 |

| Constant | −4.868 | 0.804 | −6.05 | 0.000 |

| Model C | ||||

| * = Significant at 0.05; ** = Significant at 0.001; *** = Significant at 0.000. | ||||

Appendix A.4. ANES Replications

Below are replications of Models 1 and 2 using ANES data to further validate the findings and compare them with the original analysis conducted using USC polling data. These replications replicate the main findings related to age, religious affiliation, and vote choice among Latinos, showing similar trends and correlations between religious identity and political behavior. However, one notable limitation of these replications is the omission of an immigrant generation variable. Due to the absence of a continuous measure for immigrant generation in the ANES dataset, we were unable to accurately examine the impact of being a second-generation Latino or beyond. The binary immigrant question available in the dataset lacks the explanatory power necessary to make nuanced inferences about generational differences. As a result, while we were able to identify some broader patterns, this limitation prevented us from fully understanding how generational status might interact with political behavior among Latinos.

Despite this limitation, the replication models using ANES data largely align with the conclusions drawn from the USC poll, especially in terms of the interaction between Evangelical identity and political affiliation. This consistency across datasets strengthens the argument that religious affiliation, particularly when identifying as an Evangelical, plays a significant role in shaping political attitudes and vote choice among Latinos. That being said, the power of party affiliation as a predictor in the USC dataset appears to be stronger than in the ANES data. This difference is likely attributed to the unique structure of the USC Presidential Poll, which required respondents to explicitly choose a party, thereby forcing them to engage more directly with their political affiliation. This design element may explain why party affiliation is a more potent predictor of vote choice in the USC data, whereas in the ANES dataset, party affiliation may be less strongly defined for some respondents.

Overall, these replications provide valuable insights into the relationship between Latino identity, religious affiliation, and vote choice. While some discrepancies are evident, particularly regarding the strength of party affiliation as a predictor, the overall trends suggest that Latino religious identity, especially among Evangelicals, plays a significant role in shaping political behavior. Future studies would benefit from further examining the generational aspect of Latino identity and utilizing datasets with more precise measures of immigrant status to better understand the dynamics at play.

| ANES Replication | ||||

| Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p > z | |

| Evangelical | −0.1824 | 0.0587 | 3.108 | 0.002 ** |

| Age | 0.2178 | 0.0692 | 3.382 | 0.001 ** |

| Education | 0.1473 | 0.0489 | 3.098 | 0.002 ** |

| Party Affiliation | 0.4037 | 0.0196 | 5.588 | 0.000 *** |

| Gender | 0.2529 | 0.1768 | 1.431 | 0.152 |

| Constant | 0.2486 | 0.0793 | 3.356 | 0.000 *** |

| Pseudo-R-Squared | 0.05 | |||

| Model D (n = 822) | ||||

| * = Significant at 0.05; ** = Significant at 0.001; *** = Significant at 0.000. | ||||

| ANES Replication with Interactions | ||||

| Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p > z | |

| Evangelical | −0.1987 | 0.0598 | −3.324 | 0.001 ** |

| Age | 0.1524 | 0.0119 | 2.513 | 0.012 * |

| Evangelical * Age | 0.357 | 0.4185 | 0.853 | 0.395 |

| Education | 0.472 | 0.1881 | −2.512 | 0.001 ** |

| Party Affiliation | 0.4982 | 0.0124 | 4.017 | 0.000 *** |

| Gender | 0.1476 | 0.2089 | 0.707 | 0.479 |

| Gender * Evangelical | −0.8921 | 0.9831 | −0.91 | −0.361 |

| Constant | 0.2984 | 0.0847 | 3.524 | 0.000 *** |

| Pseudo-R-Squared | 0.18 | |||

| Model E (n = 822) | ||||

| * = Significant at 0.05; ** = Significant at 0.001; *** = Significant at 0.000. | ||||

Notes

| 1 | Keep in mind that while this is the theoretical framework that is applied to this study, it is important to note that the analyses in this article are correlative rather than causal, as cross-sectional data is utilized. |

| 2 | The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health and in part by the Social Security Administration under Award Number U01AG077280. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. |

| 3 | Please note that in the replication using ANES data, which can be found in Appendix A, “generation” was left out due to their not being a continuous variable that captures the unique experience of being second and third generations. |

| 4 | The author recognizes the issues that come with coding gender as binary, but this is how the survey was designed for this poll. |

| 5 | No reverse coding was performed. A sufficiently negative interaction term can offset or even reverse the original relationship within the evangelical subgroup, leading to the observed shift in direction. |

| 6 | This can be found in Appendix A. |

References

- Allen, Levi. 2024. The Qualitative Differences Between Self-Identification as a Born-Again and/or Evangelical Christian. American Politics Research 52: 484–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvizu, John R., and F. Chris Garcia. 1996. Latino voting participation: Explaining and Differentiating Latino Voting Turnout. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 18: 104–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Samuel H., M. Kent Jennings, Ronald Inglehart, and Barbara Farah. 1988. Party Identification and Party Closeness in Comparative Perspective. Political Behavior 10: 215–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, Matt A. 2007a. Sí Se Puede! Latino Candidates and the Mobilization of Latino Voters. American Political Science Review 101: 425–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, Matt A. 2007b. The Role of Latino Candidates in Mobilizing Latino Voters: Revisiting Latino Vote Choice. In Latino Politics: Identity, Mobilization, and Representation. Virginia: University of Virginia Press, pp. 63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, Matt A., Loren Collingwood, and Sylvia Manzano. 2010. A New Measure of Group Influence in Presidential Elections: Assessing Latino Influence in 2008. Political Research Quarterly 63: 908–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, Matt A., Lorrie Frasure-Yokley, Edward D. Vargas, and Janelle Wong. 2018. Best Practices in Collecting Online Data with Asian, Black, Latino, and White Respondents: Evidence from the 2016 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey. Politics, Groups, and Identities 6: 171–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, Matt A., Sylvia Manzano, and Ricardo Ramírez. 2009. Mobilization, Participation, and Solidaridad Latino Participation in the 2006 Immigration Protest Rallies. Urban Affairs Review 44: 736–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowski, John P., Aida I. Ramos-Wada, Chris G. Ellison, and Gabriel A. Acevedo. 2012. Faith, Race-Ethnicity, and Public Policy Preferences: Religious Schemas and Abortion Attitudes Among U.S. Latinos. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 343–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambor, Thomas, William Roberts Clark, and Matt Golder. 2006. Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses. Political Analysis 14: 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brint, Steven, and Seth Abrutyn. 2010. Who’s Right About the Right? Comparing Competing Explanations of the Link Between White Evangelicals and Conservative Politics in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 49: 328–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun-Brown, Allison. 1996. African American Churches and Political Mobilization: The Psychological Impact of Organizational Resources. The Journal of Politics 58: 935–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun-Brown, Allison. 2000. Upon This Rock: The Black Church, Nonviolence, and the Civil Rights Movement. PS: Political Science and Politics 33: 168–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Angus. 1960. The American Voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, Richard Griswold del. 1992. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, Neilan S. 2014. The next Generation? A Reexamination of Religious Influence on Mexican-American Attitudes toward Same-Sex Marriage. Politics, Groups, and Identities 2: 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Kevin A. 2005. The Phantom Menace: Omitted Variable Bias in Econometric Research. Conflict Management and Peace Science 22: 341–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Converse, Phillip. 1966. Religion and Politics: The 1960 Elections. Ann Arbor: Survey Research Center, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Converse, Philip E., Angus Campbell, Warren E. Miller, and Donald E. Stokes. 1961. Stability and Change in 1960: A Reinstating Election. The American Political Science Review 55: 269–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, Russell J. 2015. The Good Citizen: How a Younger Generation Is Reshaping American Politics. Washington, DC: CQ Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, Michael C. 1994. Behind the Mule Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African-American Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De la Garza, Rodolfo, and Jeronimo Cortina. 2007. Are Latinos Republicans But Just Don’t Know It? The Latino Vote in the 2000 and 2004 Presidential Elections. American Politics Research 35: 202–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Villegas, Rodrigo, Nick Gonzalez, Angela Gutierrez, Kassandra Hernández, Michael Herndon, Ana Oaxaca, Michael Rios, Marcel Roman, Tye Rush, and Daisy Vera. 2021. Vote Choice of Latino Voters in the 2020 Presidential Election. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA. [Google Scholar]

- Downs, Anthony. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Dun, Lindsay, and Stephen Jessee. 2020. Demographic Moderation of Spatial Voting in Presidential Elections. American Politics Research 48: 750–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Gabriel A. Acevedo, and Aida I. Ramos-Wada. 2011. Religion and Attitudes Toward Same-Sex Marriage Among U.S. Latinos: U.S. Latino Attitudes Toward Same-Sex Marriage. Social Science Quarterly 92: 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbanks, David. 1977. Religious Forces and ‘Morality’ Policies in the American States. The Western Political Quarterly 30: 411–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferree, Myra Marx, ed. 2002. Shaping Abortion Discourse: Democracy and the Public Sphere in Germany and the United States. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fleishman, Rishona. 2000. The Battle Against Reproductive Rights: The Impact of the Catholic Church on Abortion Law in Both International and Domestic Arenas. Emory International Law Review 14: 277. [Google Scholar]

- Frasure-Yokley, Lorrie, Janelle Wong, Edward Vargas, and Matt Barreto. 2020. The Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS): Building the Academic Pipeline Through Data Access, Publication, and Networking Opportunities. PS: Political Science & Politics 53: 150–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup Inc. 2021. U.S. Church Membership Falls Below Majority for First Time. Gallup.Com. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/341963/church-membership-falls-belowmajority-first-time.aspx (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Gerber, Alan S., Gregory A. Huber, and Ebonya Washington. 2010. Party Affiliation, Partisanship, and Political Beliefs: A Field Experiment. American Political Science Review 104: 720–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, Philip. 2017. Why Evangelicals Voted for Trump: A Critical Cultural Sociology. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 5: 338–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Mark M., Paul M. Perl, and Mary E. Bendyna. 2006. Camelot Only Comes but Once? John F. Kerry and the Catholic Vote. Presidential Studies Quarterly 36: 203–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, Steven. 1999. Understanding Party Identification: A Social Identity Approach. Political Psychology 20: 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschwend, Thomas, and Frank Schimmelfennig. 2007. Introduction: Designing Research in Political Science—A Dialogue between Theory and Data. In Research Design in Political Science. Edited by Thomas Gschwend and Frank Schimmelfennig. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Fredrick C. 1994. Something Within: Religion as a Mobilizer of African-American Political Activism. The Journal of Politics 56: 42–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hero, Rodney E. 1992. Latinos and the U.S. Political System: Two-Tiered Pluralism. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hickel, Flavio, Jr., Rudy Alamillo, Kassra A R Oskooi, and Loren Collingwood. 2020. The Role of Identity Prioritization: Why Some Latinx Support Restrictionist Immigration Policies and Candidates. Public Opinion Quarterly 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, Marc. 2004. Political Socialization and the Future of Politics. Acta Politica 39: 331–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcheson, John D., and George A. Taylor. 1973. Religious Variables, Political System Characteristics, and Policy Outputs in the American States. American Journal of Political Science 17: 414–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, Herbert H., and Paul B. Sheatsley. 1953. The Political Appeal of President Eisenhower. The Public Opinion Quarterly 17: 443–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Correa, Michael, Helen B. Marrow, Dina G. Okamoto, and Linda R. Tropp. 2018. Immigrant Perceptions of U.S.-Born Receptivity and the Shaping of American Identity. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 4: 47–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Correa, Michael A., and David L. Leal. 2001. Political Participation: Does Religion Matter. Political Research Quarterly 54: 751–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junn, Jane, and Natalie Masuoka. 2020. The Gender Gap Is a Race Gap: Women Voters in US Presidential Elections. Perspectives on Politics 18: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Nathan J., and Jana Morgan Kelly. 2005. Religion and Latino Partisanship in the United States. Political Science Publications and Other Works. Available online: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_polipubs/14 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Kenski, Henry. 1995. Catholic and Evangelical Voting: 1992 and 1994. International Journal of Social Economics 22: 149–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienesch, Michael. 1982. Right-Wing Religion: Christian Conservatism as a Political Movement. Political Science Quarterly 97: 403–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockerbie, Brad. 2013. Race and Religion: Voting Behavior and Political Attitudes. Social Science Quarterly (Wiley-Blackwell) 94: 1145–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Mark Hugo, Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, and Gustavo López. 2017. Hispanic Identity Fades Across Generations as Immigrant Connections Fall Away. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2017/12/20/hispanic-identity-fades-across-generations-as-immigrant-connections-fall-away/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Luskin, Robert C. 1990. Explaining Political Sophistication. Political Behavior 12: 331–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, Michele F. 2020. Who Wants to Make America Great Again? Understanding Evangelical Support for Donald Trump. Politics and Religion 13: 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, Michelle F. 2022. Born Again but Not Evangelical?: How the (Double-Barreled) Questions You Ask Affect the Answers You Get. Public Opinion Quarterly 86: 621–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, Gerardo. 2019. American Blindspot: Race, Class, Religion, and the Trump Presidency. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Marti, Gerardo. 2022. Latinx Protestants and American Politics. Sociology of Religion 83: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Brandon C., and Gerardo Martí. 2024. Latinx Blue Wave or Religious Red Shift? The Relationship between Evangelicalism, Church Attendance, and President Trump among Latinx Americans. Socius 10: 23780231241259673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, Eric L. 2008. Politics in the Pews: The Political Mobilization of Black Churches. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Brian D., and Stella M. Rouse. 2013. Shades of Faith: Religious Foundations of Political Attitudes among African Americans, Latinos, and Whites: Shades of Faith. American Journal of Political Science 57: 218–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monforti, Jessica Lavariega. 2017. The Latina/o Gender Gap in the 2016 Election. Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies 42: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monforti, Jessica Lavariega, and Gabriel R. Sanchez. 2010. The Politics of Perception: An Investigation of the Presence and Sources of Perceptions of Internal Discrimination Among Latinos. Social Science Quarterly 91: 245–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, David R., and Kenneth J. Meier. 1980. Politics and Morality: The Effect of Religion on Referenda Voting. Social Science Quarterly 61: 144–48. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Brian. 2009. Review of A Matter of Faith: Religion in the 2004 Presidential Election. Presidential Studies Quarterly 39: 155–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, Laura, and John Green. 2006. The Religion Gap. PS: Political Science & Politics 39: 455–59. [Google Scholar]

- Pachon, Harry, and Louis DeSipio. 1992. Latino Elected Officials in the 1990s. PS: Political Science and Politics 25: 212–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrikios, Stratos. 2013. Self-stereotyping as ‘Evangelical Republican’: An Empirical Test. Politics and Religion 6: 800–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Robert A., and Steven P. Brown. 2005. On the Use of Beta Coefficients in Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 90: 175–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrocik, John Richard. 2009. Measuring Party Support: Leaners Are Not Independents. Electoral Studies 28: 562–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Philip H., III, and Barry C. Edwards. 2019. The Essentials of Political Analysis. Washington, DC: CQ Press. [Google Scholar]

- President Barack Obama. 2020. Barack Obama On Our Imperfect Democracy, Marriage Pressures, Racism + What He Did For Black People. YouTube. November 25. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jezBwRpwszM (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- PRRI. 2021. 2021.prri.org. Available online: https://www.prri.org/research/2020-census-of-american-religion/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Ramos, Aida I., Gerardo Martí, and Mark T. Mulder. 2018. The Growth and Diversity of Latino Protestants in America. Religion Compass 12: e12268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Barriéntez, Alicia M. 2019. Do All Evangelicals Think Alike? An Examination of Religious Affiliation and the Partisan Identification of Latinxs. Social Science Quarterly 100: 1609–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozell, Mark J. 2018. Donald J. Trump and the Enduring Religion Factor in US Elections. In Religion and the American Presidency: The Evolving American Presidency. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozell, Mark J., and Clyde Wilcox. 1996. Second Coming: The Strategies of the New Christian Right. Political Science Quarterly 111: 271–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlamanov, Kire, and Aleksandar Jovanoski. 2014. Models of Voting. Researchers World -Journal of Arts, Science & Commerce 1: 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Ronald, Edwina Barvosa-Carter, and Rodolfo D. Torres. 2000. Latina/o Identities: Social Diversity and U.S. Politics. PS: Political Science & Politics 33: 563–67. [Google Scholar]

- Schwadel, Philip. 2017. The Republicanization of Evangelical Protestants in the United States: An Examination of the Sources of Political Realignment. Social Science Research 62: 238–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoble, Harry M., and Leon D. Epstein. 1964. Religion and Wisconsin Voting in 1960. The Journal of Politics 26: 381–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkat, Darren E. 2017. Intersecting Identities and Support for Same-Sex Marriage in the United States. Social Currents 4: 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidt, Corwin E. 2022. Born-Again Versus Evangelical: Does the Difference Make a Difference? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 61: 100–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidt, Corwin E., Kevin den Dulk, Bryan Froehle, James Penning, Stephen Monsma, and Douglas Koopman. 2010. The Disappearing God Gap?: Religion in the 2008 Presidential Election. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sondheimer, Rachel Milstein, and Donald P. Green. 2010. Using Experiments to Estimate the Effects of Education on Voter Turnout. American Journal of Political Science 54: 174–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesler, Michael. 2013. The Return of Old-Fashioned Racism to White Americans’ Partisan Preferences in the Early Obama Era. The Journal of Politics 75: 110–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Kenneth W. 1986. Religion and Politics in the United States: An Overview. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 483: 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USC Dornsife Presidential Poll. 2020. USC Dornsife 2020 Presidential Poll. Los Angeles: University of Southern California. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, Derek. 2025. It’s the Economy: The Effect of Economic Policy Appeals on Latino Independents. In Political Behavior. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, Kenneth D., and Allison Calhoun-Brown. 2014. Religion and Politics in the United States. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- White, Ishmail. K., and Chryl. N. Laird. 2020. Self-Interest versus Group Interest and “Racialized” Social Constraint. In Steadfast Democrats. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol. 19, pp. 144–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, Andrew L., Samuel L. Perry, and Joseph O. Baker. 2018. Make America Christian Again: Christian Nationalism and Voting for Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election. Sociology of Religion 79: 147–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Janelle. 2018. The Evangelical vote and race in the 2016 presidential election. The Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics 3: 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Janelle S. 2015. The Role of Born-Again Identity on the Political Attitudes of Whites, Blacks, Latinos, and Asian Americans. Politics and Religion 8: 641–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).