Holding onto Hope in Times of Crisis: The Mediating Role of Hope in the Link Between Religious Motivation, Pandemic Burnout, and Future Anxiety Among Turkish Older Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. The COVID-19 Burnout Scale

2.2.2. The Dispositional Hope Scale

2.2.3. The Intrinsic Religious Motivation Scale

2.2.4. The Future Anxiety

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

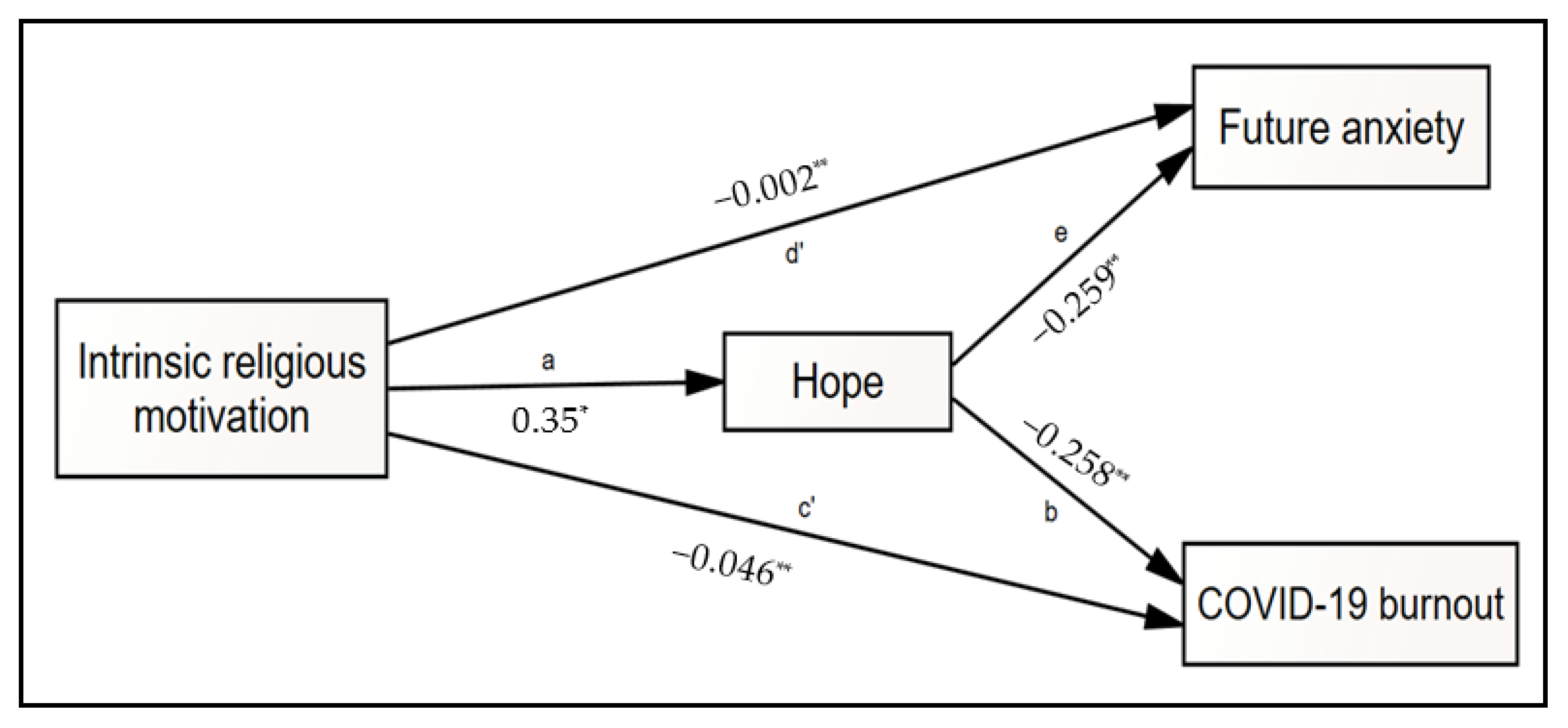

3.2. Test of Mediation Model

4. Discussion

5. Implications and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed M., Laura Nuño, Juana Gómez-Benito, and David Lester. 2019. The Relationship Between Religiosity and Anxiety: A Meta-analysis. Journal of Religion and Health 58: 1847–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul Rashid, Mohd Hazreen, Nurul Azreen Hashim, Azlina Wati Nikmat, and Mariam Mohamad. 2021. Religiosity, Religious Coping and Psychological Distress among Muslim University Students in Malaysia. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education 10: 150–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeyta, Andrew A., and Elizabeth N. Blake. 2020. The Existential Implications of Individual Differences in Religious Defensive and Growth Orientations: Fundamentalism, Quest Religiosity, and Intrinsic/Extrinsic Religiosity. In The Science of Religion, Spirituality, and Existentialism. Edited by Kenneth E. Vail and Clay Routledge. Cambridge: Academic Press, pp. 351–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Raiya, Hisham, Ali Ayten, Mustafa Tekke, and Qutaiba Agbaria. 2019. On the Links between Positive Religious Coping, Satisfaction with Life and Depressive Symptoms among a Multinational Sample of Muslims. International Journal of Psychology 54: 678–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Raiya, Hisham, Kenneth I. Pargament, and Annette Mahoney. 2011. Examining Coping Methods with Stressful Interpersonal Events Experienced by Muslims Living in the United States Following the 9/11 Attacks. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aflakseir, Abdulaziz, and Peter G. Coleman. 2009. The Influence of Religious Coping on the Mental Health of Disabled Iranian War Veterans. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 12: 175–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHadi, Ahmad N., Mohammed A. Alarabi, and Khulood M. AlMansoor. 2021. Mental Health and Its Association with Coping Strategies and Intolerance of Uncertainty during the COVID-19 Pandemic among the General Population in Saudi Arabia: Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 21: 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, Gordon W., and J. Michael Ross. 1967. Personal Religious Orientation and Prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansa, Joice Franciele Friedrich, Tatiane Trivilin, Claudio Simon Hutz, Rosa Maria Martins de Almeida, Ana Claudia Souza Vazquez, and Clarissa Pinto Pizarro de Freitas. 2024. Mental Health of Brazilian Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Gratitude, Optimism, and Hope in Reducing Anxiety. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy 46: e20220496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angın, Yasemin. 2021. Covid-19 Pandemi Sürecinden Geçerken Sağlık Çalışanlarında Dini Başa Çıkma ve Psikolojik Sağlamlık İlişkisi Üzerine Bir Araştırma. Cumhuriyet İlahiyat Dergisi 25: 331–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari Ghoncheh, Karim, Chieh-hsiu Liu, Chung-Ying Lin, Mohsen Saffari, Mark D. Griffiths, and Amir H. Pakpour. 2021. Fear of COVID-19 and Religious Coping Mediate the Associations between Religiosity and Distress among Older Adults. Health Promotion Perspectives 11: 316–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakır, Nazife, Pelin Irmak Vural, and Caner Demir. 2021. Relationship of Depression, Anxiety and Stress Levels with Religious Coping Strategies among Turkish Pregnant Women during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Religion and Health 60: 3379–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batmaz, Hakan, and Kadir Meral. 2022. The Mediating Effect of Religiousness in the Relationship between Psychological Resilience and Fear of COVID-19 in Turkey. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 1684–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, Joachim, Axel Stamm, Katharina Virnich, Karen Wissing, Udo Müller, Michael Wirsching, and Uwe Schaarschmidt. 2006. Correlation Between Burnout Syndrome and Psychological and Psychosomatic Symptoms among Teachers. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 79: 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, Selameddin. 2024. Doğal Afetler Karşısında Dini Tutum ve Ritüellerin Rolü. Sosyolojik Bağlam Dergisi 5: 142–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, Renzo, Irvin Sam Schonfeld, and Eric Laurent. 2015. Is It Time to Consider the ‘Burnout Syndrome’ a Distinct Illness? Frontiers in Public Health 3: 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, Raphael M., and Harold G. Koenig. 2013. Mental Disorders, Religion and Spirituality 1990 to 2010: A Systematic Evidence-Based Review. Journal of Religion and Health 52: 657–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, Robert, Cillian P. McDowell, Céline De Looze, Rose Anne Kenny, and Mark Ward. 2021. Depressive Symptoms Among Older Adults Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 22: 2251–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, Kevin R., Andrew Hageman, and Dawn Belle Isle. 2007. Intrinsic Motivation and Subjective Well-Being: The Unique Contribution of Intrinsic Religious Motivation. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 17: 141–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Barbara M. 2016. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamaa, Farah, Hisham F. Bahmad, Batoul Darwish, Jana M. Kobeissi, Malak Hoballah, Sibell B. Nassif, Yara Ghandour, Jean-Paul Saliba, Nada Lawand, and Wassim Abou-Kheir. 2021. PTSD in the COVID-19 Era. Current Neuropharmacology 19: 2164–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yilin, Hui Xu, Chuanshi Liu, Jing Zhang, and Chenguang Guo. 2021. Association Between Future Orientation and Anxiety in University Students during COVID-19 Outbreak: The Chain Mediating Role of Optimization in Primary-Secondary Control and Resilience. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 699388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19—Coronavirus Statistics—Worldometer. 2024. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Daoust, Jean-François. 2020. Elderly People and Responses to COVID-19 in 27 Countries. PLoS ONE 15: e0235590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, Ivone, Andreia Teixeira, Luísa Castro, Sílvia Marina, Carla Ribeiro, Cristina Jácome, Vera Martins, Inês Ribeiro-Vaz, Hugo Celso Pinheiro, Andreia Rodrigues Silva, and et al. 2020. Burnout among Portuguese Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Public Health 20: 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duplaga, Mariusz, and Marcin Grysztar. 2021. The Association Between Future Anxiety, Health Literacy and the Perception of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 9: 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edara, Inna Reddy, Fides del Castillo, Gregory S. Ching, and Clarence Darro del Castillo. 2021. Religiosity and Contentment Among Teachers in the Philippines During COVID-19 Pandemic: Mediating Effects of Resilience, Optimism, and Well-Being. Religions 12: 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, Arndt. 2022. Masks, Mosques and Lockdowns: Islamic Organisations Navigating the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany. Entangled Religions 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, David B., and C. Richard Snyder. 2005. Hope and the Meaningful Life: Theoretical and Empirical Associations Between Goal-Directed Thinking and Life Meaning. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 24: 401–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, Petros, Aglaia Katsiroumpa, Panayota Sourtzi, Olga Siskou, Olympia Konstantakopoulou, and Daphne Kaitelidou. 2023. The COVID-19 Burnout Scale: Development and Initial Validation. Journal of Mental Health 32: 985–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, Matthew W., and Shane J. Lopez. 2009. Positive Expectancies and Mental Health: Identifying the Unique Contributions of Hope and Optimism. The Journal of Positive Psychology 4: 548–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, Matthew W., Lia J. Smith, Angela L. Richardson, Johann M. D’Souza, and Laura J. Long. 2021. Examining the Longitudinal Effects and Potential Mechanisms of Hope on COVID-19 Stress, Anxiety, and Well-Being. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 50: 234–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girdhar, Ritika, Vivek Srivastava, and Sujata Sethi. 2020. Managing Mental Health Issues Among Elderly During COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Geriatric Care and Research 7: 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch, Richard L. 1994. Toward Motivational Theories of Intrinsic Religious Commitment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 33: 315–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heid, Allison R., Francine Cartwright, Maureen Wilson-Genderson, and Rachel Pruchno. 2021. Challenges Experienced by Older People During the Initial Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic. The Gerontologist 61: 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoge, Dean R. 1972. A Validated Intrinsic Religious Motivation Scale. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 11: 369–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, Daire, Joseph Coughlan, and Michael R. Mullen. 2008. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6: 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1998. Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychological Methods 3: 424–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Tzung-Jeng, Kiran Rabheru, Carmelle Peisah, William Reichman, and Manabu Ikeda. 2020. Loneliness and Social Isolation During the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Psychogeriatrics 32: 1217–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, Mohammad, Mahtab Niroomand, Fahimeh Hadavand, Kataun Zeinali, and Akbar Fotouhi. 2021. Burnout Among Healthcare Professionals During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 94: 1345–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, Zartashia Kynat, Saman Naeem, Syeda Sahar Haroon, Sidra Mobeen, and Nida Ajmal. 2024. Religious Coping and Mental Well-Being: A Systematic Review on Muslim University Students. International Journal of Islamic Studies and Culture 4: 363–76. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca, Faruk. 2001. Din Psikolojisinde Metot Sorunu ve Bir Dindarlık Ölçeğinin Türk Toplumuna Standardizasyonu [Methodological Problem in Psychology of Religion and Standardization of a Religiosity Scale for Turkish Society]. EKEV Akademi Dergisi 3: 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca, Faruk, and Mebrure Doğan. 2021. COVID-19 Salgın Sürecinde Aktif Çalışan Sağlık Çalışanlarında Ölüm Kaygısı Ile Dini Başa Çıkma Arasındaki İlişki Üzerine Bir Araştırma [An Investigation on the Relationship between Death Anxiety and Religious Coping of Actively Working Health Care Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic]. İlahiyat Tetkikleri Dergisi 55: 327–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karataş, Zeynep, and Özlem Tagay. 2021. The Relationships Between Resilience of the Adults Affected by the COVID Pandemic in Turkey and COVID-19 Fear, Meaning in Life, Life Satisfaction, Intolerance of Uncertainty and Hope. Personality and Individual Differences 172: 110592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kızılgeçit, Muhammed, and Murat Yıldırım. 2023. Fear of COVID-19, Death Depression and Death Anxiety: Religious Coping as a Mediator. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 45: 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, Rex B. 2015. Principles and Practices of Structural Equation Modelling. In Methodology in the Social Sciences. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2018. Religion and Mental Health: Research and Clinical Applications. Cambridge: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Konaszewski, Karol, Sebastian Binyamin Skalski-Bednarz, Małgorzata Niesiobędzka, and Janusz Surzykiewicz. 2022. Religious Struggles and Mental Health in the Polish Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Mediation Effects of Resilience as an “Ability to Bounce Back”. Journal of Beliefs & Values 44: 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroesbergen-Kamps, Johanneke. 2024. God Is in Control: Religious Coping in Sermons About the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Reformed Church in Zambia. Journal of Religion and Health 63: 704–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, Ram, Amit Agrawal, and Manoj Sharma. 2020. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress During COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice 11: 519–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Matthew, Grace Yukich, and Rhys H. Williams. 2021. A Divine Infection: A Systematic Review on the Roles of Religious Communities During the Early Stage of COVID-19. Journal of Religion and Health 60: 3131–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sherman A., Mary C. Jobe, Amanda A. Mathis, and Jeffrey A. Gibbons. 2020. Incremental Validity of Coronaphobia: Coronavirus Anxiety Explains Depression, Generalized Anxiety, and Death Anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 74: 102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Cindy H., Emily Zhang, Ga Tin Fifi Wong, and Sunah Hyun. 2020. Factors Associated with Depression, Anxiety, and PTSD Symptomatology During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Clinical Implications for U.S. Young Adult Mental Health. Psychiatry Research 290: 113172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lluch, Cristina, Laura Galiana, Pablo Doménech, and Noemí Sansó. 2022. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Burnout, Compassion Fatigue, and Compassion Satisfaction in Healthcare Personnel: A Systematic Review of the Literature Published During the First Year of the Pandemic. Healthcare 10: 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamid, Fayez Azez, and Dana Bdier. 2021. The Association Between Positive Religious Coping, Perceived Stress, and Depressive Symptoms During the Spread of Coronavirus (COVID-19) Among a Sample of Adults in Palestine: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Religion and Health 60: 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, Qaisar Khalid, Sara Rizvi Jafree, Malik Muhammad Sohail, and Muhammad Babar Akram. 2021. A Cross-Sectional Survey of Pakistani Muslims Coping with Health Anxiety Through Religiosity During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Religion and Health 60: 1462–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malach-Pines, Ayala. 2005. The Burnout Measure, Short Version. International Journal of Stress Management 12: 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltby, John, and Liza Day. 2004. Should Never the Twain Meet? Integrating Models of Religious Personality and Religious Mental Health. Personality and Individual Differences 36: 1275–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., William T. Hoyt, David B. Larson, Harold G. Koenig, and Carl Thoresen. 2000. Religious Involvement and Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Health Psychology 19: 211–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, Rachel E., and Ross G. Menzies. 2020. Death Anxiety in the Time of COVID-19: Theoretical Explanations and Clinical Implications. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist 13: e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, Üzeyir, Ayşe Burcu Gören, and Nükhet Bayer. 2024. The Effects of COVID-19 on Wellbeing and Resilience among Muslims in Turkey. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 27: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprisan, A., Eduardo Baettig-Arriagada, Carlos Baeza-Delgado, and L. Martí-Bonmatí. 2022. Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Associated Factors. Radiología (English Edition) 64: 119–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özer, Zülfünaz, Meyreme Aksoy, and Gülcan Bahcecioglu Turan. 2023. The Relationship Between Death Anxiety and Religious Coping Styles in Patients Diagnosed With COVID-19: A Sample in the East of Turkey. OMEGA—Journal of Death and Dying 87: 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgüç, Safiye, Emine Kaplan Serin, and Derya Tanriverdi. 2024. Death Anxiety Associated with Coronavirus (COVID-19) Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. OMEGA—Journal of Death and Dying 88: 823–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1997. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Crystal L. 2021. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Religious Motivation: Retrospect and Prospect. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 31: 213–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petretto, Donatella Rita, and Roberto Pili. 2020. Ageing and COVID-19: What Is the Role for Elderly People? Geriatrics 5: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prazeres, Filipe, Lígia Passos, José Augusto Simões, Pedro Simões, Carlos Martins, and Andreia Teixeira. 2020. COVID-19-Related Fear and Anxiety: Spiritual-Religious Coping in Healthcare Workers in Portugal. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rababa, Mohammad, Audai A. Hayajneh, and Wegdan Bani-Iss. 2021. Association of Death Anxiety with Spiritual Well-Being and Religious Coping in Older Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Religion and Health 60: 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, Noel, María López, María-José Castro, Sofía Luis-Vian, Mercedes Fernández-Castro, María-José Cao, Sara García, Veronica Velasco-Gonzalez, and José-María Jiménez. 2021. Analysis of Burnout Syndrome and Resilience in Nurses Throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 10470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roslan, Nurhanis Syazni, Muhamad Saiful Bahri Yusoff, Ab Razak Asrenee, and Karen Morgan. 2021. Burnout Prevalence and Its Associated Factors Among Malaysian Healthcare Workers During COVID-19 Pandemic: An Embedded Mixed-Method Study. Healthcare 9: 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherz, Paul. 2018. Risk in Christianity and Personalized Medicine: Three Frameworks for Understanding Risk in Scripture. Paper presented at 7th Annual Conference on Medicine & Religion, St. Louis, MO, USA, April 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Seco Ferreira, Diogo Conque, Walter Lisboa Oliveira, Zenith Nara Costa Delabrida, André Faro, and Elder Cerqueira-Santos. 2020. Intolerance of Uncertainty and Mental Health in Brazil During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Suma Psicológica 27: 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Brooke M., Alexander J. Twohy, and Gregory S. Smith. 2020. Psychological Inflexibility and Intolerance of Uncertainty Moderate the Relationship Between Social Isolation and Mental Health Outcomes During COVID-19. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 18: 162–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, Charles R. 2002. Hope Theory: Rainbows in the Mind. Psychological Inquiry 13: 249–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, Charles R., and Shane J. Lopez. 2001. Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, Charles R., Cheri Harris, John R. Anderson, Sharon A. Holleran, Lori M. Irving, Sandra T. Sigmon, Lauren Yoshinobu, June Gibb, Charyle Langelle, and Pat Harney. 1991. The Will and the Ways: Development and Validation of an Individual-Differences Measure of Hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 60: 570–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, Barbara G., and Linda S. Fidell. 2013. Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston: Pearson, 6 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Tarhan, Sinem, and Hasan Bacanlı. 2015. Sürekli Umut Ölçeği’nin Türkçe’ye Uyarlanması: Geçerlik ve Güvenirlik Çalışması. The Journal of Happiness & Well-Being 3: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Justin, and Mariapaola Barbato. 2020. Positive Religious Coping and Mental Health among Christians and Muslims in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Religions 11: 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, Rachel Sing-Kiat, Pei Hwa Goh, and Esther Zhen-Mei Ong. 2024. A Mixed-Methods Study on Religiosity, Pandemic Beliefs, and Psychological Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Malaysia. Pastoral Psychology 73: 107–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turna, Jasmine, Jasmine Zhang, Nina Lamberti, Beth Patterson, William Simpson, Ana Paula Francisco, Carolina Goldman Bergmann, and Michael Van Ameringen. 2021. Anxiety, Depression and Stress During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from a Cross-Sectional Survey. Journal of Psychiatric Research 137: 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tilburg, Theo G., Stephanie Steinmetz, Elske Stolte, Henriëtte Van der Roest, and Daniel H. De Vries. 2021. Loneliness and Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study Among Dutch Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 76: e249–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandenBos, Gary R. 2013. APA Dictionary of Clinical Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2024a. Faith-Based Partners Voice Support for Pandemic Accord. March 28. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-03-2024-faith-based-partners-voice-support-for-pandemic-accord (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2024b. World Health Organization. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Yildirim, Hilal, Kevser Işik, and Rukuye Aylaz. 2021. The Effect of Anxiety Levels of Elderly People in Quarantine on Depression During COVID-19 Pandemic. Social Work in Public Health 36: 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, Murat, and Abdurrahim Güler. 2021. Coronavirus Anxiety, Fear of COVID-19, Hope and Resilience in Healthcare Workers: A Moderated Mediation Model Study. Health Psychology Report 9: 388–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, Murat, and Fatma Solmaz. 2022. COVID-19 Burnout, COVID-19 Stress and Resilience: Initial Psychometric Properties of COVID-19 Burnout Scale. Death Studies 46: 524–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, Murat, Muhammed Kızılgeçit, İsmail Seçer, Fuat Karabulut, Yasemin Angın, Abdullah Dağcı, Muhammet Enes Vural, Nurun Nisa Bayram, and Murat Çinici. 2021. Meaning in Life, Religious Coping, and Loneliness During the Coronavirus Health Crisis in Turkey. Journal of Religion and Health 60: 2371–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, Murat, Ömer Kaynar, Gökmen Arslan, and Francesco Chirico. 2023. Fear of COVID-19, Resilience, and Future Anxiety: Psychometric Properties of the Turkish Version of the Dark Future Scale. Journal of Personalized Medicine 13: 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaleski, Zbigniew. 1996. Future Anxiety: Concept, Measurement, and Preliminary Research. Personality and Individual Differences 21: 165–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycka, Beata, Kamil Tomaka, Dariusz Krok, Sebastian Pietrzak, and Katarzyna Adamczyk. 2025. The Role of Religious Coping and Commitment in the Link Between COVID-19-Related Concerns and Mental Health. Journal for the Study of Spirituality, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Group | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 196 | 45.9 |

| Female | 231 | 54.1 | |

| Age group | 55–64 | 184 | 43.1 |

| 65–74 | 173 | 40.5 | |

| 75–84 | 60 | 14.1 | |

| 85+ | 10 | 2.3 | |

| Marital status | Single | 45 | 10.5 |

| Married | 319 | 74.7 | |

| Divorced/Separated | 63 | 14.8 | |

| Social environment | Village | 232 | 54.3 |

| District | 75 | 17.6 | |

| City | 120 | 28.1 | |

| COVID-19 experience | Yes | 240 | 56.2 |

| No | 187 | 43.8 | |

| Having chronic diseases | Yes | 239 | 56.0 |

| No | 188 | 44.0 | |

| Death of a relative due to COVID-19 | Yes | 201 | 47.1 |

| No | 226 | 52.9 | |

| Being under quarantine | Yes | 271 | 63.5 |

| No | 156 | 36.5 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRM | - | |||

| Hope | 0.305 ** | - | ||

| COVID-19 burnout | −0.158 ** | −0.242 ** | - | |

| Future anxiety | −0.083 | −0.258 ** | 0.316 ** | - |

| Mean | 3.17 | 5.29 | 2.55 | 1.47 |

| SD | 0.60 | 1.17 | 0.90 | 0.50 |

| Range | 0–4 | 1–8 | 1–5 | 0–3 |

| Cronbach (α) | 0.76 | 0.89 | 0.87 | - |

| Skewness | −0.749 | −0.696 | 0.244 | 0.299 |

| Kurtosis | 0.118 | 0.122 | 0.122 | −1.199 |

| Variable | Group | M | SD | df | t | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| COVID-19 experience | Yes | 2.64 | 0.867 | 396 | 2.92 | 0.004 | 0.087 | 0.443 |

| No | 2.38 | 0.936 | ||||||

| Having a chronic disease | Yes | 2.56 | 0.888 | 396 | 0.863 | 0.389 | −0.101 | 0.259 |

| No | 2.48 | 0.931 | ||||||

| Death of a relative due to COVID-19 | Yes | 2.73 | 0.881 | 396 | 4.44 | 0.000 | 0.220 | 0.570 |

| No | 2.34 | 0.891 | ||||||

| Being under quarantine | Yes | 2.59 | 0.874 | 396 | 1.72 | 0.085 | −0.022 | 0.345 |

| No | 2.42 | 0.953 | ||||||

| Path | Hope | COVID-19 Burnout | Future Anxiety | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | ||||

| IRM (c path) | −0.098 * | 0.076 | |||||||

| R2 | 0.010 | ||||||||

| IRM (d path) | −0.142 * | 0.133 | |||||||

| R2 | 0.020 | ||||||||

| IRM (a path) | 0.35 ** | 0.254 | |||||||

| R2 | 0.125 | ||||||||

| IRM (d′ path) | −0.002 | −0.003 | |||||||

| IRM (c path) | −0.046 ** | −0.099 | |||||||

| Hope (b path) | −0.258 ** | −0.191 | |||||||

| R2 | 0.077 | ||||||||

| Hope (e path) | −0.259 ** | −0.123 | |||||||

| R2 | 0.068 | ||||||||

| IRM > Hope > Future anxiety | −0.092 | (CI = −0.148 | −0.046) | |||||||

| IRM > Hope > COVID-19 burnout | −0.091 | (CI = −0.146 | −0.041) | |||||||

| Fit Index | Value |

|---|---|

| χ2 | 726,602 |

| df | 367 |

| χ2/df | 1.98 |

| GFI | 0.90 |

| AGFI | 0.88 |

| NFI | 0.87 |

| IFI | 0.93 |

| TLI | 0.92 |

| CFI | 0.93 |

| RMSEA | 0.048 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vural, M.E.; Geçer, H.; Hacıkeleşoğlu, H.; Yıldırım, M. Holding onto Hope in Times of Crisis: The Mediating Role of Hope in the Link Between Religious Motivation, Pandemic Burnout, and Future Anxiety Among Turkish Older Adults. Religions 2025, 16, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060666

Vural ME, Geçer H, Hacıkeleşoğlu H, Yıldırım M. Holding onto Hope in Times of Crisis: The Mediating Role of Hope in the Link Between Religious Motivation, Pandemic Burnout, and Future Anxiety Among Turkish Older Adults. Religions. 2025; 16(6):666. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060666

Chicago/Turabian StyleVural, Muhammet Enes, Harun Geçer, Hızır Hacıkeleşoğlu, and Murat Yıldırım. 2025. "Holding onto Hope in Times of Crisis: The Mediating Role of Hope in the Link Between Religious Motivation, Pandemic Burnout, and Future Anxiety Among Turkish Older Adults" Religions 16, no. 6: 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060666

APA StyleVural, M. E., Geçer, H., Hacıkeleşoğlu, H., & Yıldırım, M. (2025). Holding onto Hope in Times of Crisis: The Mediating Role of Hope in the Link Between Religious Motivation, Pandemic Burnout, and Future Anxiety Among Turkish Older Adults. Religions, 16(6), 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060666