1. Church-Related Institutional Betrayal and Institutional Courage

Survivors of domestic violence (DV) have shared numerous accounts of betrayals by entities, organizations, and institutions, including law enforcement, the family court system, the military, universities, healthcare facilities, places of employment, and religious communities. Such experiences are known as institutional betrayal (IB).

Smith and Freyd (

2014) describe IB as a “description of individual experiences of violations of trust and dependency perpetrated against any member of an institution” (p. 577). Although multiple institutions commit betrayals in cases of DV, as stated above, this article specifically addresses IB by the church, as described through qualitative quotes provided by survivors themselves. These survivors faced injustices from beloved faith communities after already experiencing the interpersonal injustice of DV.

Institutional courage (IC) is a response opposite to that of IB. Organizations act with IC through bold, proactive policies that can lead to a reduction in harm. Common to supportive entities and institutions, as reported by

Gómez (

2022), are environments that recognize problems and are willing to discuss them.

Smidt et al. (

2023) described IC as accountability, transparency, justice, and reparations and stated that courageous behavior and compassionate actions on the part of institutions could counter the effects of IB. Once again, although IC can be displayed by a variety of organizations, this article speaks directly to IC by the church in cases of DV. Throughout this article, the terms church, congregation, and faith community will be used interchangeably because they represent terms used by various participants in this study to describe the organizational context of religious and spiritual group participation.

DV is more than physical assault. It can also include tactics of emotional, verbal, sexual, financial, spiritual, electronic/digital abuse, and stalking. Often, multiple forms of abuse are present in the same relationship, as evidenced in this study. The

National Domestic Violence Hotline (

n.d.) defines DV as “a pattern of behaviors used by one partner to maintain power and control over another partner in an intimate relationship” (para. 2). The severity of abuse can vary over time which makes it difficult to quantify in a single measure; therefore, this study sought to understand which forms were experienced, instead of attempting to determine the intensity of that experience.

All of our study participants claimed a faith background. Each had experienced more than one form of DV. Of the 10 forms of abuse named in the survey, the mean of participant responses was 8.01 (

SD = 1.97), which indicates a significant rate of DV in the sample. Although one would hope that religion has a mitigating effect on the perpetration of abuse, unfortunately, the presence of DV in religious families is quite similar to that of those who do not practice a religion (

Simonič 2021). Bringing that abuse to the attention of clergy and faith communities is not a decision made lightly. Religious messaging from faith communities and sacred texts is often used to dissuade those experiencing abuse from reporting the harm or leaving the abusive relationship. The culture within religious communities prioritizes power, and victims often find themselves oppressed on multiple fronts.

2. The Study

Due to the inherent patriarchal power given to (usually male) clergy in religious settings and men in many religious homes, we desired to raise consciousness of an issue brought forward in a prior study. Survivors of DV were not only experiencing harm at home; they were also experiencing additional harms when seeking assistance and support from their churches (

Goertzen et al. 2024). Therefore, we sought to highlight a particular oppression within a common social issue and create a call to action for transformation. In addition to a quantitative survey (reported on in other literature), we wanted to explore qualitative answers to the frequent betrayal after disclosing abuse. We also note the positionality of the first author, who experienced the issue being researched, and state that the experiences were acknowledged but bracketed for the data collection and analysis.

Following

Creswell and Poth (

2018), we wanted to explore the uniqueness of the situation from silenced voices to provide a more detailed understanding of this social context, and to witness their empowerment despite the struggles. Our approach is both constructivist and transformative. Using these frameworks, we place value on the participants’ subjective views and meanings, acknowledge the power and social relationships in society, and seek structural improvements for these marginalized individuals (

Creswell and Poth 2018). Their dynamic realities are rooted in their experiences.

The overarching question for our study was, “What is the response of the church to domestic violence?” The purpose of the research was to examine the role of the institutional church in the response to DV among a diverse set of individuals. After receiving Institutional Review Board approval from the university, we recruited a purposive sample of adults who had experienced domestic violence and identified with a faith community. Prior to beginning the online survey, participants were provided with an informed consent form indicating the purpose of the study and stating that their participation was voluntary and confidential. Those who completed the survey were provided with a USD 20 gift card in appreciation for their time.

The study remained open for three months with a goal of 200 participants. After removing four incomplete responses, the final participation count was 187. The participants ranged in age from 18 to 65+. They included both women and men, who self-identified as heterosexual or non-heterosexual. They lived across the United States (33 of 50 states) and in three additional regions (North America, Northern Europe, and West Africa). Eighty-four percent of the participants were white, with the balance being Black, Latina/Latino, Indigenous, and multiracial.

There were four optional qualitative questions for this portion of the study. Each asked what the participants felt comfortable sharing and requested that no specific names, places, or institutions be shared. The first question asked them to describe their experiences with IB and how it affected their healing after DV. The second question invited participants to share how any IB impacted grief, loss, isolation, or social support. The third question asked about the experiences of IC and how it may have influenced healing. The fourth question inquired about how IC may have assisted recovery, resilience, growth, and social support. Of the 187 respondents to the quantitative portion of the survey, 78% (n = 147) chose to provide additional qualitative data by answering these questions.

Coding is a process central to making sense of qualitative data (

Creswell and Poth 2018). Multiple readings of the data in the study identified recurring themes and patterns. Based on the theories supporting this research and having conducted prior research on DV and the church, we knew that certain themes would arise, yet we were also open to the new themes that would surface during analysis. Therefore, our approach utilized both deductive and inductive approaches. Key concepts that emerged from the data on IB included betrayal, unhelpful comments, unhelpful actions, emotional distress, and spiritual distress. Key concepts that emerged from the data on IC were positive responses from the church, positive responses outside the church, and healing. Excel and NVivo were both used in the thematic analysis.

3. Findings

In our study, the length of time since disclosing the DV experienced to someone in a faith community ranged from less than a year to more than 11 years. Although most had left the DV relationship, several indicated that they had not yet left the relationship. Of the 187 participants, all answered affirmatively to multiple forms of abuse. Emotional abuse, verbal abuse, neglect, and control were all in the 90th percentile. Financial abuse and spiritual abuse were in the 80th percentile. Physical abuse was in the 70th percentile, and sexual abuse was in the 60th percentile (see

Figure 1). In these religious families, the rates of abuse were high, despite virtues such as love, peace, gentleness, goodness, kindness, and humility being prominent in religious literature.

Our purposive sample included adults who had experienced any form of DV and had disclosed, or desired to disclose, that abuse to their faith community. In qualitative research, there is an inductive–deductive thinking process and an adherence to the meaning and context of participant experiences (

Creswell and Poth 2018). Having already conducted research on this topic, the results of which led to the formulation of this study, we were aware that certain themes were going to arise, but we allowed the data to bring additional themes to the surface.

The participants’ own words illuminated deep and diverse perspectives regarding their experiences with their faith communities. To best understand the incidence of IB/IC in our target population, a spectrum of answers was desired while seeking to understand commonalities in the responses. We describe participant experiences below, as written in the qualitative questions at the end of our quantitative survey. Survivor accounts accompany the constructs named in this article. All names that appear in this article are pseudonyms.

4. Institutional Betrayal

The theory of IB comes out of betrayal trauma theory, introduced by Dr. Jennifer Freyd in 2008. IB specifically refers to the wrongdoings that institutions perpetrate against individuals who depend on them, including the failure to prevent wrongdoing and the lack of a supportive environment concerning misconduct (

Freyd n.d.). This leads to both physical and psychological distress. Examples of harms emanating from IB include post-traumatic stress, eating disorders, alcohol use, depression, anxiety, dissociation, sleep disturbance, and suicidal ideation (

Christl et al. 2024). IB can occur via commission or omission. IB by

commission involves refusing access to records and reports, cover-ups, and punishing those who report, while IB by

omission is the absence of preventative action, failure to respond to reports, and the lack of civil rights for oppressed groups (

Smith and Freyd 2014).

IB is not limited to victims of DV. In fact, connecting IB to DV is still in its infancy. IB began as a study of campus sexual assault, but survivors of betrayals by other organizations have also described this occurrence. These include universities, residential schools, and the military covering up sexual assault, religious denominations concealing clergy sexual abuse, and sporting and scouting organizations hiding the misuse of a coach/mentor’s power over young athletes or scouts (

Smith and Freyd 2014). It also includes medical centers betraying those who expose practices that cause patient harm (

Ahern 2018), legal systems betraying minority survivors of intimate partner violence (

Freetly Porter et al. 2025), sexual minority students experiencing betrayal after assault (

Smidt et al. 2021), and police, courts, and DV professionals betraying victims of technology-facilitated coercive control (

Woodlock et al. 2023), among others.

IB expands the concept of personal betrayal to include how institutions have engaged in perpetrating similar harms (

Ahern 2018). When individuals who depend on an institution subsequently have their expectations violated, there is potential for betrayal. That betrayal shatters assumptions about basic meaning-making, worldviews, and belonging. When one’s safety is dependent on an institution, lack of personal safety and any betrayals that follow lead to increased post-traumatic symptoms when the individual remains in that institution. Organizational behavior deeply impacts those connected to the institution.

Betrayal from an organization occurs in much the same way as interpersonal relationships, and the complex post-traumatic outcomes are much the same as well. IB is a significant predictor of the negative physical and mental health outcomes, increased distress, post-traumatic symptomology, and heightened risk in victims (

Lee et al. 2021;

Smith and Freyd 2017). Additionally, members of marginalized groups may already have less trust in these organizations, which can complicate their recovery. In our sample, survivors described the deep pain felt as they experienced betrayal by their faith communities, clergy, and individuals within the church. Several stated that the betrayal by the church was worse than the abuse itself. Institutions definitely play a role in victims’ experiences of trauma (

Christl et al. 2024).

IB also occurs when an institution values its own reputation over the safety or wellbeing of the individuals the organization serves (

Ahern 2018). This occurs during cover-ups, denials, and punishment of whistleblowers. When an individual reaches out to an organization for help, that person trusts that the organization will deliver the required assistance. However, survivor stories indicate that when someone reaches out for help after abuse or assault, whether it be law enforcement, legal, medical, mental health, or religiously oriented organizations, they are at risk of disbelief, blame, shame, and refusals for aid.

Since people choose their institutional affiliation, when that chosen entity engages in betrayal, it creates a unique form of harm (

Smith and Freyd 2017). Continued affiliation can lead to continued betrayal, but it can also be hard to leave when the betraying organization is your university, employer, or is related to military service (

Pinciotti and Orcutt 2021). This would be true of a chosen faith community as well. Leaving a church home, particularly for survivors who have invested years or decades into a particular congregation, brings its own set of betrayal-related grief and loss responses. Furthermore, a lack of sound spiritual counsel leaves some survivors at a decided disadvantage regarding their own personal faith and views of church benevolence.

5. Institutional Betrayal by the Church

Victims and survivors of DV have already experienced betrayal by their partner, the person they believed would love and care for them the rest of their marriage. Religious institutions have also betrayed DV victims and survivors, the institution they believed would love and care for them throughout their attendance or membership. This study revealed multiple reports in which participants stated that their pastors and churches backed their abusers while dismissing their accounts of the abuse. Additionally, a lack of knowledge among clergy about the appropriate response to abuse put the participants at risk.

Public awareness and published research regarding how institutions are involved in harming individuals is growing, but there is little focus on this issue in the context of DV, and even less in conjunction with the institutional church’s response. Abuse, neglect, and abandonment represent violations of trust, and this creates betrayal trauma. The closer the relationship, the greater the betrayal (

Birrell et al. 2017). Victims of DV who take their faith and religious involvement seriously can feel a deep sense of connection to that institution. Some victims of DV lean into their faith for support in bewildering, horrific cases of personal betrayal and trauma. Relying on one’s faith community for added emotional and spiritual provision is a natural extension of that. Finding, instead, an absence of support is deeply devastating.

Understanding an institution’s involvement in traumatic experiences requires that we examine how institutions might be involved in abuse. In many cases, powerful administrations have protected the institution rather than the individuals served by the institution (

Smith and Freyd 2014). In the church, this relates to religious harm or spiritual abuse.

Oakley et al. (

2024) define spiritual abuse as “a systemic pattern of coercive or controlling behavior in a religious context or with a religious rationale” and can have a “damaging impact on those who experience it” (p. 190). One would hope that the intersection of IB and spiritual abuse would never occur within the church, but it has, repeatedly.

The IB that some survivors face while seeking assistance from their churches adds yet another layer to the healing they must navigate, often without the benefit of supportive resources needed for their full recovery. This is illustrated by the following survivor comments:

For Dawn, the church seemed supportive until she said the only way she would be safe would be to file for divorce. Then, the tables turned on her, and she went from being supported to being made to resign her position as a children’s worker.

Juanita wrote that her church experience was horrible. Her children had reached out for help, and the leaders of the faith-based organization cut them off within 24 h, despite having been with the organization for nearly two decades. She took our survey as a reminder that the abuse was real, she was not crazy, and the church had chosen to abandon them in their time of need.

There was disappointment for Camille when, after reporting physical abuse and harm, the pastoral response was to talk about mutual sin.

Diana said it was both scary and deeply distressing that hypocritical behavior was so common in the church, and that fear tactics were used to keep women subordinate.

Tommy told his wife’s grandfather about their marriage problems, and the response was to just pray about it. He had hoped for intervention, but this just pushed him away.

The church Estella attended was silent. They knew and yet they said nothing. Her ex actively stalked her, even showing up at church, and no one protected her. When she left the service, no one made sure she was safe. No calls, no texts, nothing.

Taylor mentioned having never felt more alone in a crowded room, completely isolated from any spiritual help. This was particularly difficult because it was the only LGBTQ+ affirming faith community in the area.

Lizette was in church leadership when she disclosed the abuse. At first, she was told to work on the marriage, which only caused further trauma. When she ended the relationship, she was made to feel guilty about what she had done to the reputation of the church.

Other participants in our study mentioned that they suffered in silence due to fear and shame. They were instructed to be better wives, to stick it out, and told not to leave the marriage even when safety was an issue. Some were ignored, and others were berated. Multiple participants discovered that church leadership had taken the side of their abuser. Nothing was done, even when the abusive spouse spread lies or bullied the victimized spouse on church property. They reported that these betrayals made their healing more difficult.

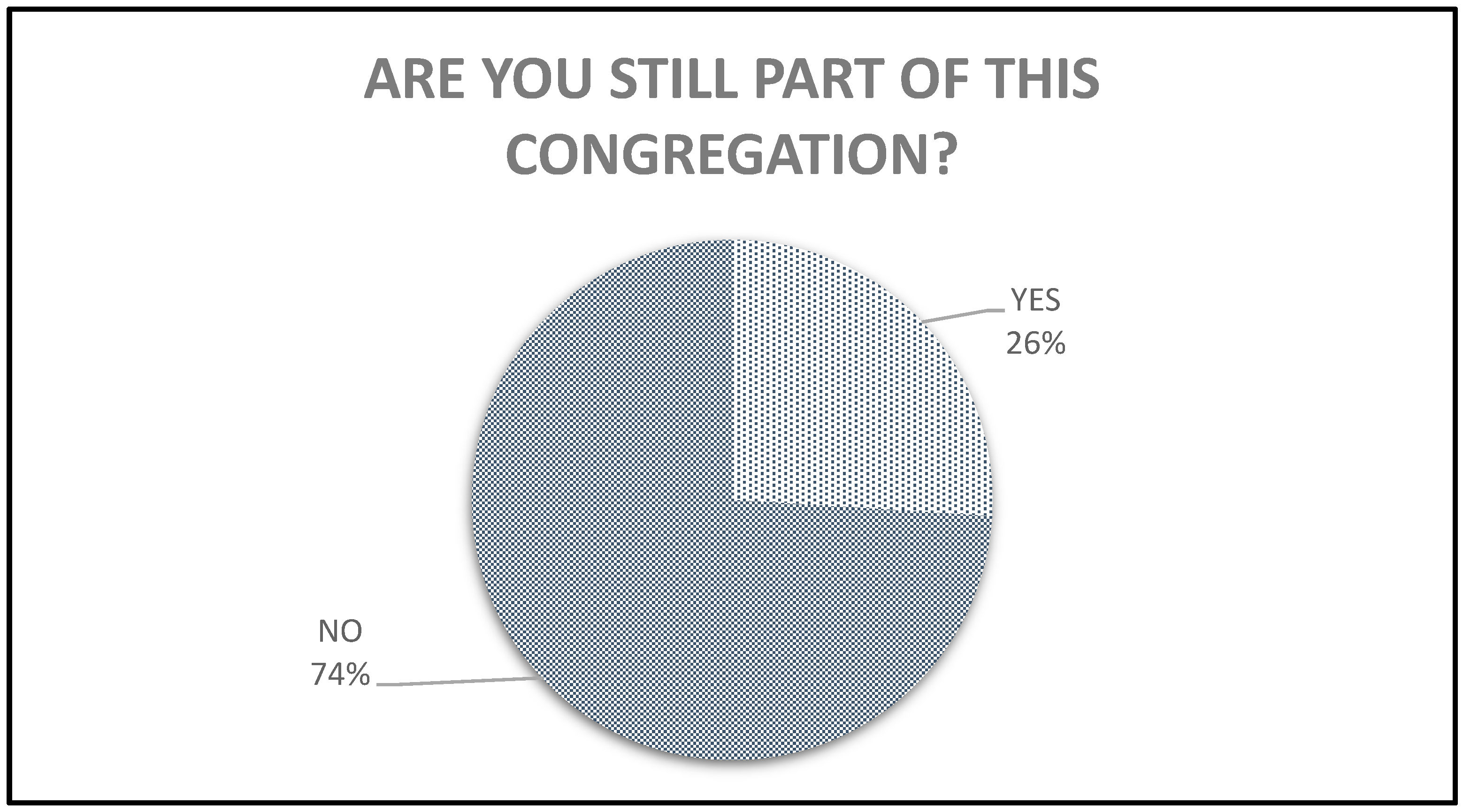

Many survivors leave an institution after experiencing betrayal. In this study, 74% of the participants (

n = 139) no longer attended the church that betrayed them, despite 87% (

n = 162) declaring that prior to this experience, they felt a “good deal” or “very much” a part of the church. This is illustrated in

Figure 2, which shows a significant number stepping away from the church due to harm. After such deep betrayals, multiple participants mentioned that they now struggle to trust anyone in church leadership. The connection with their religious group has been severed.

More than one participant in this study stated that never again would they set foot into a church. Several stated they had to leave their church homes, some were forced out, others were asked to leave, and still others chose to leave when the leadership supported their abuser over them and their children. Loss of community and disconnection negatively impact healing and growth (

Birrell et al. 2017). This was evidenced in our study, including descriptions of grief, loss, and isolation.

Participants noted that churches need to be better equipped. One stated that maybe clergy try to help with the knowledge they have, but being undereducated about DV means they do not respond appropriately. Faith leaders often do not recognize the signs of abuse or trauma, and the topic of therapy can be controversial among church leadership. Pastoral or Biblical counseling for the marriage is often recommended over individual licensed, professional counseling because clergy do not know that couples counseling is contraindicated in cases of DV. A study by

Goertzen and Fox (

2023) noted that 96% of the 349 faith leaders surveyed in that study agreed that the church has a role in intervening in cases of DV. The question that follows, then, is what does that intervention look like, and is it based on betrayal or courage?

One particular form of betrayal frequently mentioned in our study was that church leadership was not willing to call out the acts of abuse, nor to confront the person causing harm. Among respondents to this study, the perpetrators of abuse were seldom held accountable. Survivors were cut off and left to feel like outcasts, while the perpetrators were supported and their continued presence in the church was often welcomed. In some cases, participants reported that even the faith leaders participated in gossip, smear campaigns, and spreading rumors.

Relationships within the community are also damaged. Fellow church members who had been friends would even show up in court to testify against them at divorce hearings, which is an example of another form of betrayal. IB includes members of the organization participating in betrayal behaviors. Religious congregations are entities in which the gospel ought to be displayed in word and deed, including ministering to the physical and emotional needs of congregants (

Costello and Yancey 2022). When the opposite occurs, survivors may struggle with both personal and communal aspects of their faith.

Our participants mentioned that trite advice from a person uninformed about the nature of abuse created additional damage. One participant said that knowing how little help was available in the church was depressing. Another stated that the congregation’s response was bewildering and disorienting. While some survivors mentioned retaining their faith despite the church’s harmful actions, others mentioned how their children had walked away from the church, or even away from the faith, because of the negative treatment within their faith community. In these cases, the children noticed that those already being harmed at home experienced further harm by those in the church. One participant stated that her children did not believe that Christians were good people.

6. Institutional Courage

Institutional courage (IC) is the proposed remedy for IB (

Freyd and Smidt 2019). It is the supportive, proactive climate offered by institutions to those who have been harmed, and it may offset the negative effects of IB (

Smidt et al. 2023).

Nightingale and Cousineau (

2024) summarize IC into four categories: transparency, accountability, support, and resources. Transparency is about being open and clear; accountability is listening, apologizing, and caring for those who report; support includes trauma-informed, survivor-centered response efforts; resources involve not only support for the survivor, but also financial and personnel assets allocated to make sure all four of these areas exceed the bare minimum (

Nightingale and Cousineau 2024). For the church, this requires prioritizing proper response and caregiving to those harmed, being willing to assist with finances or other resources, and holding perpetrators accountable. IC is a matter of justice for survivors.

In her Resources for Changemakers,

Freyd (

2022), who coined the terms IB and IC, emphasized steps toward change. These include education, compliance with civil laws, balancing power dynamics, cherishing truth-tellers, responding appropriately to disclosures of harm, using the organization as a means of addressing systemic issues, and an ongoing commitment of resources to these actions of courage. Freyd stated that these steps are “crucial to ensuring that courageous ideas become courageous practices” (para. 1). Without knowledge of the IB and IC constructs, these are the kinds of changes that survivors indicated that they want to see: education, recognition of criminal behavior, addressing power dynamics and systemic harm, appropriate and compassionate response to disclosure, and the use of congregational resources to improve support for survivors and their children.

These are “courageous moral actions that prioritize the safety and needs” of the individuals who were harmed over the institution itself (

Adams-Clark et al. 2024, p. 2). Engaging in IC may help reduce instances of IB through the presence of preventative processes and protective policies (

Gómez et al. 2023). True courage is evidenced in sustained action over time (

Brewer 2023). Maintaining policies, increasing resources, promoting authenticity, and appropriately handling public response takes years of dedicated effort. IC involves the ongoing assessment of the institution (

Gómez et al. 2023). In some situations, this would be carried out through anonymous surveys that assess institutional climates.

Faith communities can accomplish this through transparent conversation with those who have been victimized. If there is any institution that should be eager to embrace courage, display compassion, and be protective of those feeling the weight of oppression, it should be the church. Among the components of religious culture is the responsibility to relieve suffering and care for the vulnerable. Making the needed changes (Proverbs 3:27 KJV) and upholding justice for the oppressed (Psalm 82:3 KJV) are concepts found in the Christian scriptures.

Especially in faith communities, focusing on the reputation of the institution or that of the perpetrator should never be the emphasis. An approach focused on liability and risk-reduction in congregational settings undermines the seriousness of the situation. Courage must be more commonplace (

Brown 2021). With IC comes needed change. Educating and encouraging faith communities to display courage instead of betrayal would begin to change these additional harms. Individuals within faith-based organizations can be courageous in seeking to identify institutional and religious values and living according to them. The presence of social support can alleviate the negative effects of DV (

Cheng et al. 2025). Survivors will be able to see and feel this support. They will know they do not have to stand alone.

7. Institutional Courage in the Church

IC is displayed when there are proactive steps to prevent damage, create safe environments, encourage the reporting of harm, making harm easy to report, handling reports with integrity, exposing inherent problems instead of covering them up or denying their existence, providing supportive resources and assistance, stating that the institution will be improved due to the reporting, and creating a place in which continued involvement with the institution is valued (

Freyd and Smidt 2019). Churches may not have a formal reporting process for DV in the same way that helping professions do. However, victims of DV still frequently reach out to their faith leaders for assistance. Courageous responses are evidenced in the following participant experiences:

Chantel mentioned how the elders in her church are now believers in good therapy. The church is also seeking training on how to understand the signs of abusive marriages and how they can help.

Octavia wrote that her pastoral staff could not have supported her better.

Brigette was thankful that not only did her pastor believe her, but an attorney in the church helped with her case.

What helped Marta was that a family in the church allowed her and her daughter to stay in their home. The hosts approached the church and facilitated a conversation that led to the help she received.

For Liz, what really made a difference was that the women in her church backed her up and shared their own stories with her.

Kimmy appreciated that the church helped with her children and covered her in prayer.

Rissa discovered that sharing her story with more than one church helped her see that some individuals were caring, understanding, and willing to listen. She was not treated poorly, nor did anyone make anything more difficult for her.

A pastor supported Ellen when CPS opened three cases against her husband. The pastor told her to cooperate and let them do their job. She was encouraged to share the truth about his behavior. The church’s love, care, and protection positively impacted her healing journey. The pastor acted with humility and even apologized for mishandling things in the beginning.

When survivors of DV are on the receiving end of courageous actions by their faith communities, they feel encouraged and empowered. Promoting autonomy and choice is an important part of this, as empowerment can improve mental health and alleviate distress (

Cheng et al. 2025). The perception of available support, and the reality of that support being accessible, bolsters coping ability and can improve mental health (

Kocot and Goodman 2003). Religious congregations are often recognized as pillars in the community. Providing both tangible and emotional support should not be difficult for faith communities where social and spiritual capital exist among leadership and congregants.

When churches demonstrate bravery, survivors find community. Instead of feeling betrayed, they realize there are safe, kind people in the world who will help them process the grief and pain they have endured. Finding their voices and being heard was vitally important to the participants in our study. Not feeling judgement or condemnation after disclosing abuse or going through a divorce meant that they could more freely share with those in their faith communities. When the church believed them, it helped them heal and become stronger versions of themselves. Supportive group dynamics lead to stronger communities.

Positive experiences with faith leaders mentioned by participants in this study included humility, kindness, and patience. Food, utility payments, holiday gifts, paying for therapy, sending survivors to supportive retreats, and placing the perpetrators under church discipline were all named as courageous responses that impacted their recovery in a positive way. There were participants who mentioned that their pastors chose to become more educated about abuse as they helped them. One participant said the pastor was a champion for the abused. Another stated that the genuinely kind faith leaders are worth their weight in gold.

8. Betrayal and Courage Together

It is not always all bad or all good. Some institutions display both betrayal and courage (

Adams-Clark et al. 2024), sometimes at multiple levels simultaneously (

Smidt et al. 2023). In Smidt et al.’s study, participants who experienced courage in addition to betrayal had more positive workplace outcomes than if there were only betrayal. To overcome broken trust, an institution must begin to rebuild that trust through IC (

Brewer 2023), and expressions of IC can form a point at which healing starts to happen (

Adams-Clark et al. 2024). This is instructive for faith communities, where caring for people is generally a top priority. When a church can identify acts of betrayal and instead begin to engage in courageous responses to DV, survivors feel supported, and the healing continues.

In this current study, there were multiple participants who shared both positive and negative responses. Some congregations had changes of heart. Some pastors saw the error in how they originally handled things and made efforts to respond in better ways. Some participants stated they found restoration in a subsequent congregation after experiencing multiple betrayals in the initial church. One survivor stated that it was hard to answer the survey questions because she experienced both betrayal and courage from the same church.

Bonnie experienced years of ruthless betrayal by her church. She eventually left that church and attended another, which also betrayed her in some ways. Eventually, there was a change in leadership at the first church, and the new leadership not only came to her to apologize but also engaged in making restitution, including paying for her therapy and creating a guide for handling cases of abuse. The second church, in time, also came around and supported her. After a mixture of experiences with the church, the courageous responses are part of her survivor story and healing journey.

Matthew understood that the church wanted to help, but they admonished him to continue to try to make the marriage work. Eventually, they understood why he had to get a divorce, but he claimed they struggled to see the problem for what it was.

For Antionette, there were individuals who responded appropriately, but they were mostly people who had experienced abuse themselves. She stated there were zero congregational examples of handling her case with grace.

When Sondra first disclosed to her priest, he named it as abuse and was supportive, but as time went on, he became vague and did not follow through on the ways he had offered to help.

Polly did not feel betrayed but noticed how few in the church understood abuse. She had support, but there were also people telling her to stay in the marriage, even when they knew the details.

The pastor who married Darcy and her husband at first offered to counsel them, but suddenly stopped with no explanation. The assumption was that the destructive marriage was her lot in life, which made it feel like the church condoned the abuse as long as her husband did not hit her again.

While Inez did not experience direct cover-ups or invalidation, there was still a minimization of the abusive behavior, and they asked her what her part in the abuse was. There were no proactive steps taken to stop the abuse or support her.

Roberta’s church offered counseling and support and encouraged the involvement of the police. But, they also recommended couples counseling and gave her harmful, uninformed books. She was grateful to have secular resources that provided clarity about the abuse.

When support systems are inconsistent and ambiguous, the stress and emotional burdens of the survivor can be amplified (

Kocot and Goodman 2003). At times, there is a less obvious betrayal that

Brown (

2021) labeled

institutional cowardice. These are the murky, gray areas of IB that were less about outright harm and more about neglect, i.e., the refusal of an institution to try harder, overcome inconvenience, and not being willing to get involved. Brown noticed that it was often accompanied by ‘risk management’ professionals. Included in this institutional cowardice were rumor, favoritism, not apologizing, and ghosting, all of which were experienced by our participants.

Faith leaders told many of the survivors in this current study that they would help, but then, to the survivors’ utter dismay, they were completely ignored. Faith leaders must never be so busy that they walk away from the poor, the weary, the oppressed, and those suffering injustice in silence. The

United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (

2025) declare that solidarity with the vulnerable means committing to the common good, building community, defending human rights, and working together for justice and peace. The Christian scriptures clearly indicate that God is a refuge for the oppressed (Psalm 9:9 KJV) and that God’s people are to show their faith through their good works (James 2:18 KJV).

9. Why Addressing IB and IC Matters

Based on the qualitative survivor responses in our study, there was an evident lack of religious community support available for those exiting DV relationships. Significant stressors, such as the presence of IB, can disrupt healthy functioning. Recovering from DV is a lengthy, non-linear journey that is best accomplished with the support of formal and informal structures. Supportive community networks strengthen resilience (

Howell et al. 2018). Survivors who want to connect their spirituality to healing and recovery mentioned having a hard time receiving the help they need and sometimes must rely on finding an online support group on their own or navigating their own path to growth outside of an uninformed or unavailable faith community. One participant noted that there is so much at play in this discussion: theology, gender roles, submission, etc. She loves the church and wants to see it flourish, but she also sees an epidemic of abuse within marriages and families that does not reflect the heart of God.

Addressing IB and embracing IC would go a long way in making changes that provide both tangible and moral support for victims and survivors of DV, and their children. This requires a willingness to identify and live by stated values, to institute change, and hold perpetrators accountable (

Brown 2021). Institutions will need to engage in continual self-assessment and follow through with corrective actions (

Gómez et al. 2023). Education initiatives are imperative for faith communities, and interventions should include training paid church staff, committee personnel, and those involved in lay leadership. Single-session training cannot cover all the needed information; instead, ongoing education is a better model (

Freyd and Smidt 2019). Research-based education will provide knowledge drawn from empirical evidence to illuminate these topics.

Further research on these constructs from the authors of this article will be forthcoming. It is also hoped that other researchers will begin to address IB and IC in conjunction with the institutional church and/or domestic violence. Additional suggestions for research aligned with IB and IC include God-image in survivors of DV, gendered stereotypes, and bystander involvement. Although the harms committed upon DV survivors by their religious communities have been addressed in prior research, it has not yet been presented in conjunction with IB, nor has IC been suggested as the remedy. This article brings those ideas together. Further research is vital to illuminating, understanding, and responding to betrayal via courage in our communities.

10. Implications for Faith Communities

The Centers for Disease Control lists faith communities among the vital sectors needed for implementing community protective factors (

CDC 2025). Congregations must intervene and become supportive institutions as a matter of justice for the oppressed. Faith communities are known as helping entities that provide spiritual guidance and social support to those in the community. Churches can be ideal entities to help those who have fled abusive relationships if they have adequate education and awareness of this subject. Numerous sacred texts encourage love, service, kindness, and helping those in need. Faith leaders should take DV allegations seriously and be willing to accept feedback without being defensive. They should be proactive in reducing their congregations’ chance of committing IB by actively seeking and participating in courageous action.

Implications for adjusting strategies within faith communities are as follows: institutions should prioritize member safety, review policy, and take proactive measures to change or implement policies that protect members (

Christl et al. 2024). Faith-based entities can consider their mission and purpose within the community. Clergy should enact policies and procedures to use victim-centered approaches and promote IC (

Smidt et al. 2023). Both actions and inactions contribute to IB, and both need to be part of the plan to reduce risk to victims and survivors of DV. Important aspects toward courageous response are for churches to be educated, provide training for leadership, consider the role of women in ministry in the church, address church messaging, and have a written policy outlining a proper and compassionate response to the issue of DV (

Goertzen 2024).

In our current study, pastors, priests, rabbis, elders, deacons, Sunday School teachers, small group leaders, other congregants, and ‘the guy who collects the offering’ were all named as individuals who created harm. This is not limited to a single denomination or faith group, or a particular role within the congregation. Male and female pastors were both named in betrayal and courageous acts, and this happens in both small and large congregations. Faith communities have a choice in how they respond to DV; they have the opportunity to choose betrayal or courage. As stated by the interfaith partnership,

Safe Havens (

n.d.), clergy are often at the front lines of DV response, which places them in a unique position to provide support and encourage safety measures for those impacted.

After experiences of betrayal, finding a supportive community, whether in the church or not, was a lifeline to DV survivors. Sometimes support came from a new congregation. At times, it came from a DV shelter. Survivors also mentioned friends, family, neighbors, and counselors who helped. Others found support in groups outside of their own faith. When local support could not be found, books, websites, podcasts, and online forums provided much-needed validation and comfort to these survivors. Online support groups allow survivors to discover that they are not alone and that there are many others also trying to recover after DV. In these groups, deep friendships can be formed, even across great distances. For some survivors, this is their only measure of meaningful support.

In follow-up emails to the first author, participants called the survey in this study validating, important, a sign of solidarity, and another step in the healing journey. One wrote that if there had been more access to resources, changes might have been made sooner in her case. Another said that there is still fogginess and confusion about the truth of things related to the DV. One female who identified herself as being “older” stated that she has been slow to share publicly about the abuse and mentioned that it took a long time for her to realize how toxic the relationship really was; but, a great therapist and realizing that the Divine wanted her to be treated well led to her healing. Many said they are still in the process of recovery, and acknowledged how taboo this topic is in the church context.

11. Conclusions

We know that some victims and survivors of DV will experience IB to the extent that it will create significant barriers to healing. Institutions can either worsen or improve post-traumatic outcomes through their betrayal or by demonstrating justice and support for those who have been oppressed by DV. We also know that this is a pervasive, collective issue across the country and even around the world. To address systemic and structural oppression in the home and community, it must be called out. When a congregation does not prioritize prevention, or has an absence of DV policy, or when the leadership make it hard to report, engages with misinformation, or discredits and blames the victim, we have evidence of IB. Therefore, it is vital that we actively engage with IC by engaging in brave and courageous deeds to protect the vulnerable in significant ways. This is part of the necessary formation of faith communities. We must listen to those affected and take action to support them. By examining lived experience, we can elevate the voices of those pushed to the margins and make sure they know how valued and important they are. As one participant wrote, “What is the purpose of the church, if not justice and mercy?”