1. Introduction

This study, conducted from June to September 2024, was inspired by questions asked by the authors, all Irish musicologists with a research and practical professional interest in plainchant: firstly, what is the significance of plainchant to choral singers in an Irish context today? Secondly, do Irish choral singers engage easily with learning and performing plainchant? Thirdly, can musicologists share their knowledge in an outreach sense, to enable engagement among choral practitioners with early musical forms such as plainchant?

In Western culture, plainchant is familiar to music students as the ancient source for modern Western music notation and theory, and to choral singers as the earliest surviving European sacred choral song which formed the basis for the evolution of church choral traditions. Plainchant has formed a core sacred vocal repertory for Western Christianity for over a millennium, and a surge of interest in chant as an early music repertory over the last one hundred and fifty years has meant that chant and related sacred vocal repertories have found a firm place in musicological and medieval studies internationally. Since the Reformation, chant has had a somewhat fraught history in Western Europe, with approaches to performance and dissemination determined by a wide spectrum of theological differences between Catholic and Protestant denominations, and a number of revivals of practice in English and continental contexts over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (

Bergeron 1998;

Zon 1999). In particular, a resurgence of interest in Gregorian chant associated with the Oxford movement in the 1830s, closely followed by the Cecilian movement in continental Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century, paved the way for the restitution of chant (and associated liturgical forms, such as the Divine Office) in both Catholic and Protestant jurisdictions over the course of late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The primacy of chant in Catholic liturgy was codified by Pope Pius X in his motu proprio of 1903,

Tra le sollecitudini (

Pope Pius X 1903;

Collins 2010). By the twenty-first century, chant became established as an important part of the Early Music and Historically Informed Performance movement with “an enormous expansion of plainchant studies in the last few decades [of the twentieth century]” (

Hiley 1995) For the amateur choir today, simple plainchant repertories such as Benediction hymns can be an important first step in the study of Early Music. From an educational perspective, the monophonic character and moderate tessitura of much chant repertoire would imply that this music could act as ideal material for choral training for all age groups (

Heywood 2019;

O’Neil 2025), and indeed the profusion of opportunities for performing chant in choral competitions, and in choral grade examination curricula, would suggest that it is an acknowledged part of choral culture in anglophone musical contexts.

In Ireland’s more recent past, historically and socially, plainchant has occupied a curiously paradoxical status. Gillen points out that in the early modern era (the sixteenth to the late-eighteenth century), due to the penal laws enacted by the British government, the majority of Catholic Irish worshippers did not participate in congregational singing at all, and the

missa lecta (spoken mass) was preferred; even after the Emancipation, plainchant responses were sung by clergy alternating with altar servers and choir, so that “in consequence of its outlawed status, the public celebration of the liturgy was furtive and rudimentary, in which singing hardly figured… Hymn singing … or other conspicuous displays of devotion were simply not part of the worshipping agenda” (

Gillen 2000, p. 549). In her study of early modern popular music practices in the Cork area, O’Regan points out that the silent congregation, listening to the choir but not themselves singing the plainchant Ordinary or hymns, was also a feature of English Catholic liturgical practice in the era of the penal laws, as a recusant practice, and states that “[the] musical disconnection between choir and congregation persisted in Irish Catholic churches into the twentieth century” (

O’Regan 2018, p. 203). O’Regan and Phelan point out that from the eighteenth century onwards, while Irish Catholics did cultivate paraliturgical devotional songs in the Irish language, they continued to leave liturgical singing mainly to the clergy and choir. Congregational singing, usually of psalms, but also of chant settings in the vernacular, was more associated with Anglican practice in an Irish context (

O’Regan 2018, p. 205;

Phelan 2002, p. 90). The re-establishment of chant among Irish Catholics following the penal law period was initially mainly the business of the clergy and trained musicians in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, influenced by the Cecilian movement (

Collins 2010).

Yet, in the present-day Irish context, plainchant now has a more established association with a broader Irish Christian identity and lay choral practitioners. A small selection of Gregorian chants in the original Latin was included in the Irish secondary music curriculum up until the mid-1990s (

Music 1989;

Music Syllabus 1996), reflecting both a link to Irish Catholic heritage and a nod to historically informed performance practice, in its listing alongside secular Early Music repertories such as Renaissance madrigals in the syllabi. These days, chant also features in the performance programming and competition syllabi of music and choral festivals nationwide in Ireland, with plainchant either required or recommended in sacred music competitions for both schools and adult choirs (e.g.,

Feis Ceoil 2025;

Limerick Choral Festival 2025). In the very recent past, there has also been a slowly growing appetite for chant workshops in Irish choral practice. In 2024 alone, there were three public plainchant workshops offered for amateur choral singers by high-profile Irish cultural and musical organisations: a Medieval chant workshop with French cantor and historically informed practitioner of medieval chant, Bruno de Labriolle, in the 2024 Cork Choral International Festival (

Cork Choral Festival 2024), a Plainchant Workshop for Singers as part of the Education and Outreach Programme of Pipeworks International Choral and Organ Festival 2024 (

Pipeworks 2024), and a Gregorian Chant Workshop with the Director of the Sistine Chapel Choir, with the Palestrina Choir, Dublin, at St Mary’s Pro-Cathedral (

Palestrina Choir 2024). Several Irish third-level institutions offer study in plainchant via early music specialisations, both as musicology modules and as performance ensembles, while the University of Limerick and St Patrick’s Pontifical University, Maynooth, offer postgraduate programmes with specialisms in chant study and performance (

MA in Ritual Chant and Song 2025;

Masters in Liturgical Music 2025). Many universities offer opportunities for doctoral research in the area of historically informed performance of Gregorian chant and Early Music, according to departmental expertise. All in all, it would seem that chant is now an acknowledged, established part of choral culture in an Irish context.

While chant serves these educative and evocative functions academically and culturally, it remains, however, a polarising genre in the world of its origins: that is, in the sphere of liturgical music. Traditionally associated with medieval Latin liturgical texts, chant has become caught up in the ongoing battle between what might be characterised, somewhat simplistically, as conservative and liberal liturgical sensibilities in the Irish Catholic Church today, with plainchant often (though not invariably) associated with a conservative sector preferring the Traditional Latin Mass (e.g.,

Kwasniewski et al. 2023;

Tierney 2025). The association of Gregorian chant with obscure Latin texts can be a deterrent for church choir directors, worried about the intelligibility of some of the lesser-known Latin texts for modern congregations and audiences, particularly at a time when Latin is no longer routinely taught in most Irish schools (

Johnson and Priestley 2022). Increasingly in the twenty-first century, chant settings using vernacular texts to replace the original Latin are being employed in the post-conciliar Mass (

Bartlett 2011;

Schmitz 2017), following established Anglican practices in setting chant melodies to vernacular translations (

Marshall 1964).

Perceived difficulties with older notation conventions (

Strayer 2013), rhythm, and diverse performing styles for plainchant can form another barrier to the learning and performance of chant, on the part of both choir directors and choral singers. In secular contexts, the programming of chant as a part of an earlier sacred Christian tradition can be viewed as arcane and potentially elitist by concert organisers and funding agencies. And yet, plainchant continues to hold a fascination for choral singers, congregations and audiences alike.

This paper seeks to understand how amateur Irish choral singers and directors engage with plainchant repertories, given the issues outlined above. It offers an exploratory qualitative study, which examines current attitudes to teaching and learning chant among Irish choral practitioners, and establishes levels of interest in learning about and performing chant, awareness of resource availability and perceived barriers to learning.

2. Methodology

This research began with the basic question: what is the significance of plainchant as a repertory for Irish choral singers? Is it easily accessible, given its association with older liturgical traditions and particularly, the difference in notational style from modern music? The aim of the study was to explore the current position of chant in contemporary Irish choral practice across all educational levels, to explore how people engaged with or did not engage with it in both an aesthetic and practical sense, and to understand any perceived barriers in learning and performing chant repertories by non-specialist singers given the available resources. The purpose of generating such knowledge was to benefit plainchant scholars in directing the production of resources for use and dissemination by non-specialist choirs and audiences. A final objective for the study was educational outreach, an attempt to understand the best ways to connect choral singers, choral directors and teachers with existing scholarly research and practice in chant analysis, education and performance.

We decided to employ an exploratory approach to our study, utilising mixed methods with a primary focus on generating qualitative data for a phenomenological exploration of our participants’ understanding of plainchant and its social and spiritual role in Irish society. Our research design fits Almeida’s definition of “sequential exploratory design” (

Almeida 2018, p. 140), in which we used two instruments sequentially, firstly an online questionnaire, distributed to choral singers and directors, and comprising both closed-ended and open-ended questions, and secondly a focus group interview, which explored themes raised in the open-ended questionnaire responses in more detail. Focus group interview participants were recruited from among the questionnaire respondents via a participation link included at the end of the questionnaire form. The purpose of this approach was to establish themes and topics relating to perceptions about plainchant performance important to our participants, which might be further refined and investigated in subsequent research. This fits Almeida’s description of exploratory research design, as being “[a mixed methods design] in which qualitative data is the primary source of information. This … is particularly suitable for exploring a phenomenon in which there isn’t a guiding framework or theory and measures or instruments are not available” (

Almeida 2018, p. 139). Quantitative data were generated in the use of close-ended questions in the online questionnaire which included Likert scale questions to enable participants to self-define their music literacy levels, the type of choral activity in which they usually participated, and also binary questions querying whether participants engaged (or did not engage) with chant repertories and the performance thereof (this is described in more detail in the Results section).

The objective of the focus group interviews was to explore perceptions about chant offered in the questionnaire responses in more detail and to understand the discursive positioning of chant among choral singers from diverse backgrounds. Focus group discussions were semi-structured, with the questionnaire responses used as prompts to encourage free discussion of themes by the participants (see

Supplementary Materials). The semi-structured approach was taken to enrich the qualitative data generated in the questionnaire instrument, in order to phenomenologically explore participants’ feelings and attitudes to plainchant performance in some depth, following McLafferty’s notion that focus groups “can be exploratory and aimed at generating hypotheses … and can be phenomenological, in that they give access to people’s common sense conceptions and everyday explanations” (

McLafferty 2004, p. 188)

Thematic analysis was used to extrapolate dominating themes or topics among the opinions and experiences of participants as offered in the open-ended questionnaire responses and focus group discussions, triangulated by quantitative data provided by closed-ended questionnaire responses. Thematic analysis was used to identify both explicit and implicit meanings from dominating discursive topics among our participants, a constructivist approach to analysis which as

Joffe (

2011) suggests, gives a deeper understanding of social phenomena than simple content analysis:

The concept of ‘thematic analysis’ was developed, in part, to go beyond observable material to more implicit, tacit themes and thematic structures … such material can be termed ‘themata’ and these tacit preferences or commitments to certain kinds of concepts are shared in groups, without conscious recognition of them. Thematic analysis … permits the researcher to combine analysis of the frequency of codes with analysis of their more tacit meanings, thus adding the advantages of the subtlety and complexity of phenomenological pursuits.

We recruited choral singers and directors of music via the national choral association, Sing Ireland, who kindly distributed the online questionnaire and accompanying information note in their members’ newsletter of May 2024.

3. Results

We established a four-week period for the completion of the questionnaire, and by June 2024, we had received 61 responses, of which 28 indicated interest in further participation in focus group interviews. In the end, 9 of these 28 respondents participated in a focus group interview. The focus group participants included novice and more experienced choral singers, as well as two choral directors. The questions within the questionnaire instrument (

Supplementary Materials) were intended to establish the socio-cultural, musical and educational identity of the participants, with questions 1–3 asking participants how they would define their role in their choir, the kind of choir they sing in, and their current music literacy levels. Questions 5–7 then addressed the participants’ engagement or lack thereof with plainchant, whether they had previously performed chant, and in what kind of performance contexts. Question 6 queried participants about obstacles they might encounter while learning to perform chant, while question 8 queried participants about what resources might make the learning of chant easier and more efficient. Below, we describe the emergent themes from the questionnaire responses and the expansion of these themes in the focus group discussions, where this occurred.

3.1. The Connection of Plainchant with Liturgical Contexts

Results were fairly consistent in some respects: out of 61 respondents, 55 (90.2% of respondents) felt they would prefer to perform or hear plainchant in an authentic sacred context such as a religious service. and this was a view held even by those who answered that they did not particularly like to sing plainchant.

This was in response to question 5, “In which context would you perform plainchant, given the opportunity to do so?” From this we can infer that for Irish choral singers, the experience of plainchant is inextricably linked to liturgical context and function, an important consideration for researchers of early music in understanding the best approach to reconstruct performances of plainchant for the benefit of modern Irish audiences. Consideration of venue, musical function and acoustics is a central aspect of historically informed approaches to selecting settings for performing early sacred music, as commented by Nuchelmans in his 1992 essay on reproducing the right context for early music:

“[A consideration of] setting is essential if an attempt is made to recreate the original function of music: say, for example, the reconstruction of the Office of Vespers or some other liturgical service, perhaps sung at the appropriate time of day (or night). To attempt such a reconstruction in a modern concert hall would simply be anachronistic. Convincingly ‘authentic’ surroundings can help the audience to relive something of the original ‘performance’ context.

Taking a concern for authenticity further, for our Irish respondents, hearing, performing and experiencing chant was most meaningful in relation to congregational participation in an authentic liturgy, and was not a passive auditory experience. The respondents saw themselves as active participants in the perpetuation of a liturgical form rather than mere audience members or concert performers, in this respect.

3.2. A Strong Tendency for Church Choral Participation

Not surprisingly, then, the profile of Irish choral performers who answered the questionnaire indicated that singing in liturgical contexts was a strongly defining aspect of their activities as choral singers, directors and organists, regardless of their level of involvement in singing chant per se, with 46 out of the 61 respondents (75.4%) indicating that they were members of a church choir (see

Figure 1).

This was an indicator to us as researchers that church choral participation and sacred choral singing are perhaps more central elements of Irish choral activity as a whole than we had initially anticipated, and this can be an important consideration in developing outreach resources and activities. That said, it would be worth noting that the title of the questionnaire as posted in the Sing Ireland newsletter may well have drawn active response by members of church choirs and those specifically involved in sacred music, and have otherwise been ignored by those involved in more secular choral activity. This may be confirmed by the fact that in answer to question 4 (“Are you interested in singing plainchant?”), 53 out of 61 respondents, or 86.9%, stated yes. The few that had a negative response to question 4 were also church choral musicians, who felt that plainchant was anachronistic and boring, and felt strongly enough that they clearly said so in the context of the questionnaire responses. In the open-ended responses to question 7 (“If you have performed plainchant before, please provide some details about the performing context and the repertory you chose”), of the 41 responses, 28 overtly stated that they had previously performed chant at a church service of some kind, ranging from Anglican services to Catholic Divine Office, with just 6 responses stating only a non-liturgical context for their previous experience in performing chant.

3.3. Sociocultural Dispositions to Plainchant Among Respondents

An interesting overview of sociocultural dispositions to plainchant emerged in the open-ended responses invited by question 4b (“Why are you interested/not interested in singing plainchant?”), in which many of the respondents commented on the functionality of plainchant in liturgical contexts, and confirmed that liturgical function is an important element in the advocacy of plainchant for these people. 17 out of the 61 responses to this question cited heritage and historicity as an important aspect of their engagement with plainchant, and the reason they felt that chant should be preserved and promoted, with comments such as the following:

I have a strong interest in Church Heritage. Plainchant has been part of the heritage and prayer of the Church for centuries and there is a distinct possibility that this important cultural and religious heritage will be lost if it is not practised and performed.

(Q. 4b, respondent 9)

In focus group discussions, the theme of heritage and historicity remained an important aspect of the participants’ engagement with plainchant, with one participant eloquently describing her perception of Gregorian chant as simultaneously an Irish, historic, monastic phenomenon, which she found engaging and even beautiful on a spiritual level:

If anybody asked me to define what chant was … it would be Gregorian chant and the monks of Glenstal Abbey. It combines my two loves—I love history and I adore singing. At a very basic level, I think it’s hypnotic and it calms my soul … It would occasionally come up, in the background of a film, or … the background of something historical and Irish, you know, on RTÉ [Irish national TV] or something like that. You would hear it, and I would pick up on it, and I just thought, it was so beautiful. What comes to mind … Celtic. Celtic crosses, St Brigid, they’re just words that come into my head when I think of chant.

(Respondent 31)

Later, the same participant voiced a concern that plainchant might disappear if ordinary people (rather than clergy or other religious) did not help preserve it:

I think it should be kept alive, because we shouldn’t lose it. It should be used … and it shouldn’t be allowed to die. And I love the connection … with history and the past, and just connecting the past and now together. That’s what I think is beautiful about it.

(Respondent 31)

Continuing in this vein, in the questionnaire responses, 18 out of 61 directly cited the aesthetic, emotional and spiritual effect of singing and listening to chant as the reason for their engagement with this repertory, with simple comments such as the following illustrating this kind of engagement: “Interested in singing plainchant[;]it is beautiful singing without accompaniment and lovely to sing songs in Latin” (question 4b, Res. 10), “Love the haunting sound, brings you into a lovely spiritual place” (question 4b, Res. 36) and “I like the calming effect it has on me” (question 4b, Res. 52). In the focus group discussions, several of the participants expanded discussion of the aesthetic appeal of chant to incorporate a connection between singing chant and a sense of community and well-being, with one regular singer in a chant choir pointing out that

“Chant seems very natural to me… I do find chant more unifying—it is great when you do the four-part harmony and everything; you do the great big works and there’s a great deal of ego in it… There’s no ego, I find, in chant. [In unison singing]you’re just in the moment together, and I think that is marvellous!”

(Respondent 3)

Another participant overtly stated the connection between singing chant and developing well-being through meditation and mindfulness:

Like the whole thing in schools nowadays, talking about well-being. Surely the whole medium of chant ties into that because you’ve got the breathing, the calmness; you’ve got meditation, you’ve got community, and listening to each other in that sense of community.

(Respondent 16)

Nostalgia was a motivating factor for some, with 8 of 61 questionnaire respondents to question 4b noting that they had learnt chant by ear in school, in both primary and second-level school contexts, and particular reference made by one respondent to the 1933 chant pedagogy publication,

Plainsong for Schools (

Society of St. John Evangelist 1930), as a useful resource for basic hymns and the Mass ordinary, taught in a straightforward way. Five respondents stated that they were interested in acquiring an understanding of the relationship of chant to the liturgy.

Finally, 14 of 61 respondents stated that they had a third-level music qualification, with the majority of these involved in choral direction or as competition-level choral singers. While most of these respondents had considerable experience singing and directing chant and demonstrated emotional or spiritual engagement in the genre, not all of these more advanced singers claimed mastery over their singing of chant, and four of these respondents overtly cited neumatic notation as being a challenge, as, for example, the following response by an experienced cantor indicates in some detail:

I also find reading the neumes challenging—I have had very little exposure to this. I find it much easier to learn it by ear or to read staff notated versions of the original. Our local priest kindly gave me some plainchant books, but … I struggle with the neumes. I can sight-sing most staff notated music with relative ease, but I would have to work out chant notation in advance.

[Question 8, Respondent 58]

Nonetheless, plainchant held much the same aesthetic appeal for experienced choral singers and those with third-level musical training, as it did for community singers without advanced training, with comments like the following typifying these responses:

Completed a module during under-graduate studies and there is a lovely sense of freedom and movement when singing chant. It would be lovely to engage in more.

[Question 4b, Respondent 28]

It can be so beautiful, and I like growing in my understanding of how other sacred music I sing is referring to or using it. I think it is powerful in helping us to listen to each other and feel the shape of … a musical line. It’s an interesting challenge and change of perspective.

[Question 4b, Respondent 51]

Of those with third-level training and advanced choral experience, 12 out of 14 of these respondents indicated in response to question 5 that they would be open to singing and hearing chant in secular and educational contexts, demonstrating a flexibility towards liturgical function that was absent in other cohorts.

3.4. Obstacles to Engagement with Chant

As expected, in response to question 6 (“If interested in performing plainchant, are there any obstacles that have deterred you from learning and performing this vocal style?”), lack of familiarity with reading square notation was an overt issue for 9 of the 54 respondents to this question, with comments such as the following illustrating the problems encountered:

“Initially becoming familiar with the notation and the modes was difficult. As well as understanding their place in the liturgy.”

[Question 6, Respondent 2]

“The notation and performance practice were very confusing until I got a chance to join a chant group and learn it in person from a qualified instructor”

[Question 6, Respondent 1]

The topic of the difficulty with the square notation used for Gregorian chant also arose in the focus group discussions, with one choral singer citing a feeling of being an “outsider” to the knowledge needed to understand the notation, at a chant workshop she had attended in the previous summer: “It is very difficult to follow that notation… I think I was a bit overwhelmed. I felt everybody around me knew what they were talking about, and I was just there as a curious bystander.”

(Respondent 31)

Five of the respondents added that a perceived lack of learning resources was an obstacle or deterrent to their performing chant, and respondents inferred a need for multi-modal resources, including online print scores and explanatory notes, teaching videos, and opportunities for face-to-face learning with an experienced teacher. Comments such as the following demonstrate that a lack of opportunity for the study and performance of chant interacting with low self-efficacy effectively deterred respondents from learning to chant:

“I found that there are not enough plainchant learning resources and learning opportunities available for my level of musical literacy”

[Question 6, Respondent 9]

“Don’t know of any groups and wouldn’t be that confident approaching them even if I did. I’m an experienced choral singer but have no experience in plainchant”

[Respondent 33]

“Not trained to do so. Limited opportunities to learn.”

[Respondent 35]

“[Lack of ] Knowledge/confidence of teaching it”

[Respondent 40]

Six of the 54 responses mentioned the language barrier involved in understanding ecclesiastical Latin as constituting a potential barrier to engagement with chant as a repertory by both choirs and congregations, a small but significant factor worth noting, with comments such as the following illustrating this issue:

“… the lack of knowledge and, more importantly, understanding of Latin among choir and congregation”

[Respondent 11]

“Resistance from clergy to include Latin”

[Respondent 32]

“… whilst I have become accustomed to Church Latin, most of the young cantors I work with haven’t, and would find the combination of a different style of singing coupled with a new language quite daunting.”

[Respondent 58]

In the focus group discussions, the issue of Latin as a barrier to textual comprehension was discussed in some detail by an experienced church choir director, who otherwise acknowledged the aesthetic and spiritual value in the sonic quality of sung chant:

“I know that there’s no objection to having mixed languages throughout the service, but basically, the people I meet wouldn’t have a facility with Latin first of all, and certainly wouldn’t understand it. I do have a thing about, do people understand what they’d be singing in a different language. On the other hand, I’m well aware that the fact of just being present in the atmosphere and the beauty of being present where chant is sung … it’s uplifting in its own way, and it helps people to engage in prayer at that level. So I’m kind of tied between the two things at this stage in my life”.

[Respondent 11]

Interestingly, one barrier to engagement that emerged in the focus groups in particular was a concern about the stylistic ambiguity in plainchant performance, particularly in relation to rhythm, and the implications of this for the amateur singer. One participant pointed out that this was confusing to her, and made her uncertain of the “correct” way to sing chant, as a choral singer: “… if you are going into singing the chant, and the Benedictines do it one way, and the Cistercians do it another way, and they get very religious about it, you know, and that can be very off-putting, if you are going into the detail of it.” (Respondent 3). Similarly, the experienced choir director spoke about singing chant in his youth, and having had no aural reference for this at the time, which impacted his confidence in teaching his choir chant even in the present day:

But in those days, I’m talking … the 1950s and 60s, there were no videos; there was no YouTube to help you interpret it. You just read it and hoped that you were getting there… I’d feel completely inadequate in trying to direct people into it, but I’d love for people to experience it because it’s a very rich way of celebration.

[Respondent 11]

There was a wide variety of suggestions for useful resources offered in response to question 8 (“What resources would you like to see available to enable you to learn plainchant?”), pointing towards the kind of multi-modal learning that became standardised as a pandemic learning model in recent years, combined with a significant demand for face-to-face learning models, including standard choral rehearsals, workshops with specialists, and even one-on-one tuition. Being choral singers, it was no surprise that 12 of the 44 respondents to this question indicated that they would prefer some form of face-to-face learning to better their understanding of chant, with 6 of these citing workshops as their preferred way to learn.

Those with more developed music literacy skills had some useful suggestions regarding the presentation of the original notation alongside modern notation and aural resources, with the following comments exemplifying these ideas:

“Modern editions provided alongside original neumes to aid with interpretation.”

[Question 8, Respondent 49]

“… Digitised manuscripts or additional access to manuscripts so that repertoire can be expanded- collaborations between early music academics to create a ‘whole world’ connectedness between the music and materials.’

[Respondent 18]

“(i) The music score, along the lines of an older book Plainsong for Schools; (ii) Recordings of the chants; (iii) Guidelines on how to interpret the notation”

[Respondent 11]

“Continuing improvements in cataloguing, availability and accessibility of ancient texts (including digitisation) and transcripts to broaden the repertoire.”

[Respondent 19]

Such comments revealed a curiosity among the more advanced singers to have some visual interaction with original manuscripts via digitised archives and similar resources, though with the proviso that such resources needed either verbal mediation by experts or transcriptions to make sense of the original.

4. Discussion

The results of the questionnaire and focus group responses above have confirmed a number of expectations on the part of ourselves as researchers while presenting some surprising elements as well. The inextricable linking of plainchant with liturgy by our study participants confirmed an expectation for us as Irish choral practitioners, but it is worth noting that such a connection might be more tenuous in other cultural contexts where chant may be more familiar to performers and the general public as a historical repertory and less so in its living connection with liturgy. While a statement of religious denomination was information not overtly requested in the questionnaire or in the focus groups, nonetheless, it became clear that those engaging with our study were mainly practising Catholic church musicians, with Anglican chant practices also referenced several times in the open-ended questionnaire responses, but not in the focus group discourse. For most participants, their perception was that plainchant was a style of sacred music connected with Irish Christian identity and history, rooted in medieval monastic culture, and in danger of dying out. There were four main contexts in which participants initially encountered plainchant. Eight of our 61 respondents (13%) explicitly pointed out having learnt chant in primary and second-level school contexts, sometimes confirming an age bracket of 50–75 by stating the decade of study (spanning 1960s–early 1980s) in which they had institutionally learnt chant in Irish Catholic school contexts prior to the changes instigated following Vatican II. A slightly smaller number (7 out of 61 respondents, or 11%) had initially encountered chant in their attendance at a Traditional Latin Mass; 4 of 61 respondents (6.5%) overtly stated that their first encounter with chant was at Church of Ireland (Anglican) services; while about 26% of participants (16 out of 61 questionnaire respondents) were music graduates and teachers, who had been exposed to chant history and performance in educational contexts through their third-level musical studies. In addition, it was notable that trained musicians among our respondents were more likely to have performed plainchant in both Catholic and Anglican contexts. The majority of our participants were Irish born and raised, apart from one questionnaire respondent who stated that they were an American citizen working and studying part-time in Ireland.

Individual approaches to learning chant were also of interest, with a surprising number of respondents of all levels of music literacy citing learning by ear as an important mode for learning chant repertory and style. Low self-efficacy (

Bandura 1990;

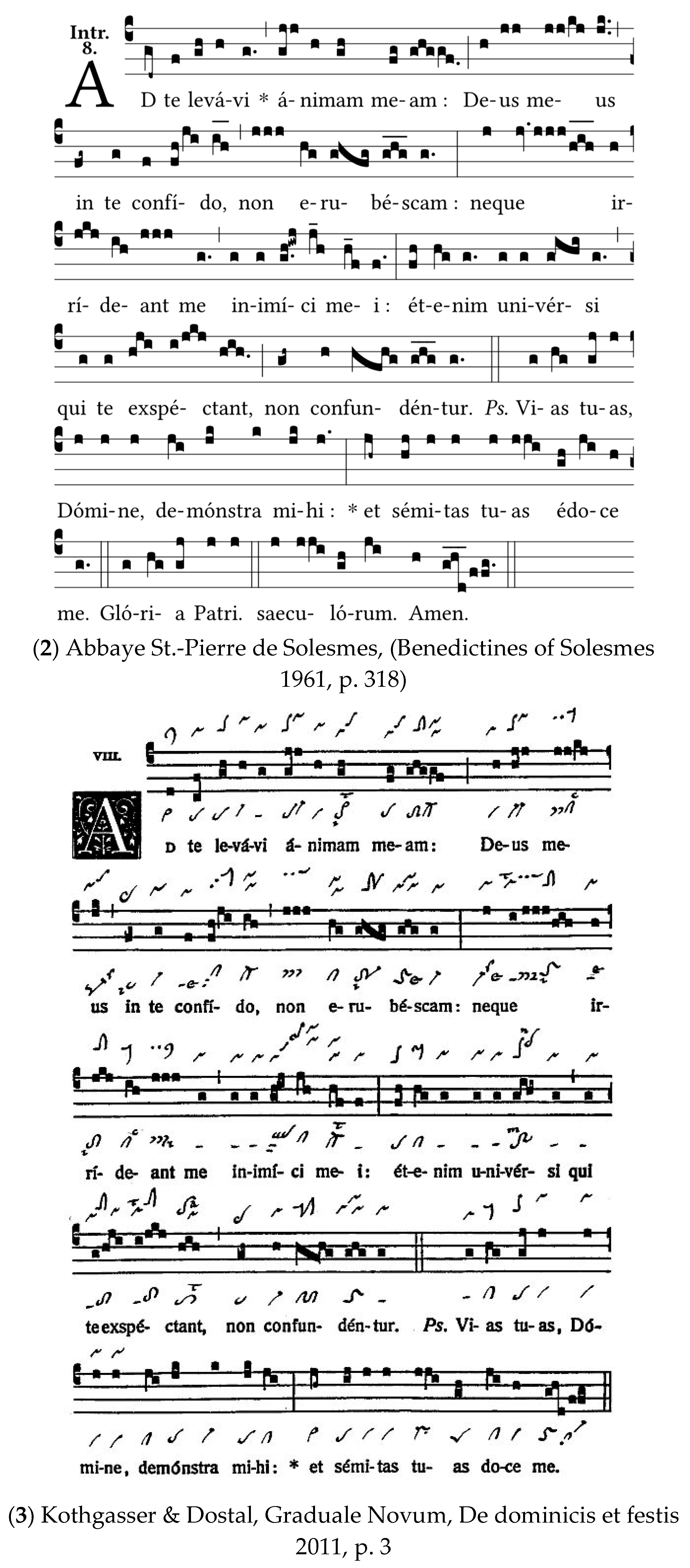

McPherson and McCormick 2006;

Zelenak 2024) seemed to characterise much of the focus group discussions, which had included novice and experienced choral singers as well as very experienced choral directors, carrying on a tendency that had manifested strongly in the questionnaire responses. While a small number (6 of 54 respondents) expressed concern about difficulties in understanding and musically articulating ecclesiastical Latin texts, it was notable that in a sizeable 30% of responses (16 out of 54) to the “learning obstacles” question, respondents expressed a lack of confidence in performing chant due to uncertainty about notation, and ambiguous stylistic aspects of directing and singing plainchant arising from this. It was an axiom in the focus group discussions and questionnaire responses that our participants’ description of chant notation as an alternative to modern staff notation was in reference to the late nineteenth-century/early twentieth-century Solesmes quadratic notation, a synthetic notational form based on 13th-century French quadratic notation, rather than to more obscure medieval adiastematic notational forms (such as the St. Gall and Laon neumes). As some 44% (27 out of 61) of respondents had indicated a general lack of confidence in sight-singing, the issue of having a specialised notation with no reference to key or standardised rhythm arose as a specific obstacle to participation. Indeed, even those more advanced music readers, including choir directors, chamber choir singers, and those with third-level music qualifications, cited the specialised chant notation as being the difficult aspect of learning and performing chant. Solutions suggested in the questionnaire responses by less experienced musicians tended towards aural and audio-visual aids (and indeed, both novice and experienced musicians among our participants endorsed learning by ear as an important means of learning chant performance style), while the main suggestion from the more advanced musicians was the provision of transcriptions alongside facsimiles of the original source.

In general, the stated difficulty with specialised chant notation across all levels of music literacy in our participants seemed to indicate that the notation itself was perhaps the core cause for low self-efficacy in performing chant across the board. Solesmes Abbey has retained a thirteenth-century style of notation in its publications as a means of disseminating chant repertories while capturing the nuances of the original neumatic scores. Yet this approach seems to have accrued an esotericism that advanced choral musicians in this study saw as a challenge, but which novice singers saw more as an obstacle to participation.

Hiley (

2009) comments on this when he endorses the utility of Solesmes notation in conserving the nuances of the original neumes but points out that this notational form is paradoxically only useful to those who know how to read it:

In the case of chant the manner of transcription is somewhat controversial. It is generally considered important that the note-groupings of neume notation should be reflected in any modern transcription, and I certainly subscribe to this view. It is largely achieved in the printed notation developed by Solesmes… Nevertheless, square notation is not universally known, and it would [be] a barrier for many [non-specialist] readers … needing a further act of translation, when the musical examples should be taken in at a glance.

Indeed, throughout the modern era, editors issuing printed editions of chant have had to deal with the persistence of much older and even anachronistic notational forms since the printing of the infamous Editio Medicaea Gradual in 1614 (

Haberl 1894), at a time when modern notation was emerging in printed instrumental music, and the divergence of printed chant from standard notation seems to have posed difficulties ever since. While the Medicean edition did simplify the older, late medieval notation into an easily readable quadratic notation that survived the massive changes generated in musical notational style and editorial practice over the course of Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, the Solesmes scholars elected to return to the older neumatic indications, because the Medicean notation had become too reductive and did not authentically capture the rhythmic nuances of the original medieval manuscripts. However, for modern choral musicians, not necessarily schooled in an understanding of the archaic conventions of chant notation, the return to a neo-medieval, obscure notational form can be a block to participation.

What then might be a way forward in providing church choirs with more easily accessible and relevant resources for learning and performing chant? Simply utilising modern notation to create an approachable Gregorian score may not be enough. A core reason for the development of Solesmes square notation in the first place was the need to represent obscure medieval chant performance indications and ways of executing notes that are not easily represented in modern notation, and hence, as Peattie points out,

Many of the signs used by scribes of the 10th, 11th and 12th centuries have no standard equivalent in modern notation, and the notation of neumes of two or more notes, often written in the original with a single stroke of the pen, adapts uneasily to modern conventions of music engraving. Even the quadratic typeface developed by Desclée for Solesmes, based on 13th-century models, does not capture many of the essential details of the earliest notations. (

Peattie 2016, p. 125)

It is widely accepted that utilising transcriptions in Solesmes notation is the best compromise in order to grasp a near-authentic sense of original aspects of medieval chant performance style, and “bridge the gap” between original neumatic notation and modern notation. Some of the key figures involved in the Solesmes chant restoration project in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such as Dom Pothier and Dom Mocquereau, wrote extensive guides to explain their quadratic notation and how to perform it, and educational work by Justine Ward in particular was an important step in transmitting principles of chant performance in an easily understood way for schoolchildren (

Bunbury 2001). However, more recently, chant scholars have felt this approach to be insufficient, and

Peattie (

2016) went one step further and proposed that

the challenges of translation can be largely avoided by creating editions in the original neumatic language, and [I would] argue that the musical notation of many 11th- and 12th-century manuscripts is perfectly accessible to singers today, and is preferable in many respects to transcriptions in modern noteheads.

The Solesmes Graduale Triplex (

Benedictines of Solesmes 1979) aligned original Laon and St. Gall neumes with the Solesmes quadratic notation, and thus offers a good example of a chant edition which meets Peattie’s criteria. Following on from the Triplex, recognising the difficulties in capturing the melodic and rhythmic subtleties of older neumatic chant notation, some efforts were made in the 1980s by musicologists involved in historically informed performance of chant to generate hybrid notational forms that captured the ancient neumes in a way that was easier for those used to singing from standard notation, with varying degrees of success, such as Geert Maessen’s “Fluxus” notation fusing St. Gall neumes with the four-line staff of quadratic notation (

Maessen 2013). In addition, a new “critical” edition of the Gradual, extending upon the work of Dom Cardine in the Graduale Triplex, was published in 2011 (

Kothgasser and Dostal 2011), utilising a simplified quadratic notation alongside Laon/St Gall neumatic indications. Most recently, in 2020, the ambitious “Neumz” audio resource project was launched, as a digitisation of the entire corpus of Gregorian chant, combining Graduale Triplex simplified quadratic notation (aligned with Laon/St Gall neumes) as scrolling scores to accompany audio recordings of the daily Office and Mass sung by Benedictine nuns of the Abbey of Notre-Dame de Fidélité and the monks of Abbaye Sainte-Madeleine du Barroux in France, recorded over a period of three years (

Odratek BV 2025). Such a resource works well to demonstrate chant performance style, and offers guidelines to the structure of the liturgy and where chant fits into this; however, it does not currently offer a guide on how to interpret notation and acts as an aid for informed listening rather than performance learning as such.

Many of the comprehensive chant publications recently issued thus still depend on a specialist understanding of different notational forms outside of the purview of the ordinary choral musician, and again, such complex approaches to notation can be a deterrent to participation among choral singers outside of academia. These editions are not for the inexperienced. Such editions, and the explanatory theories provided by Solesmes scholars, tend to be prohibitively complex for practical use by non-specialist singers, while Ward’s method was intended for longitudinal educational purposes with children and youth, and does not necessarily work well in andragogic contexts. In addition, the changing approach to interpreting Gregorian chant from Pothier and Mocquereau in the early twentieth century to the more accepted semiological approach by the Dom Cardine school in the later twentieth century has created an uncertainty that has tended to alienate church choral singers somewhat in the present day.

From the perspective of transmitting chant repertories to church choirs, in a recent doctoral study,

Wakefield (

2025) comments upon the incompatibility of explanatory manuals and chant methods in the context of teaching adult amateur singers, stating that “… while many books on Gregorian chant exist, along with webpages and YouTube channels dedicated to Gregorian chant, they do not necessarily provide information in a way or at a level that connects with adult learners’ experiences.” (

Wakefield 2025, p. 86). Wakefield goes on to suggest that a succinct, pragmatic approach which is low on theory, is more useful for adult learners in any field, because adult learners are oriented towards practical learning that solves immediate problems and they “… may not engage or may quickly disengage from learning when they do not understand the necessity of the given topic in relation to their lives” (

Wakefield 2025, p. 39). Bearing in mind also that the idea of adult learning bias, or design fixation (

Jansson and Smith 1991) means that adult singers may prefer to experience learning chant with reference to modern notation with which they are already familiar and comfortable, and it is important to incorporate this learning preference while also offering the twenty-first century choral singer some experience of seeing the original chant from which the transcription was made. Several editions of chant in modern notation, including a complete Liber Usualis (

Benedictines of Solesmes 1924,

1947), have been created since the early twentieth century, but few of these editions present the opportunity to see modern transcriptions alongside facsimile images of original chant, or alternatively, even modern editions of chant alongside Solesmes notation, to help in teaching a performative understanding of this interim notational form (see

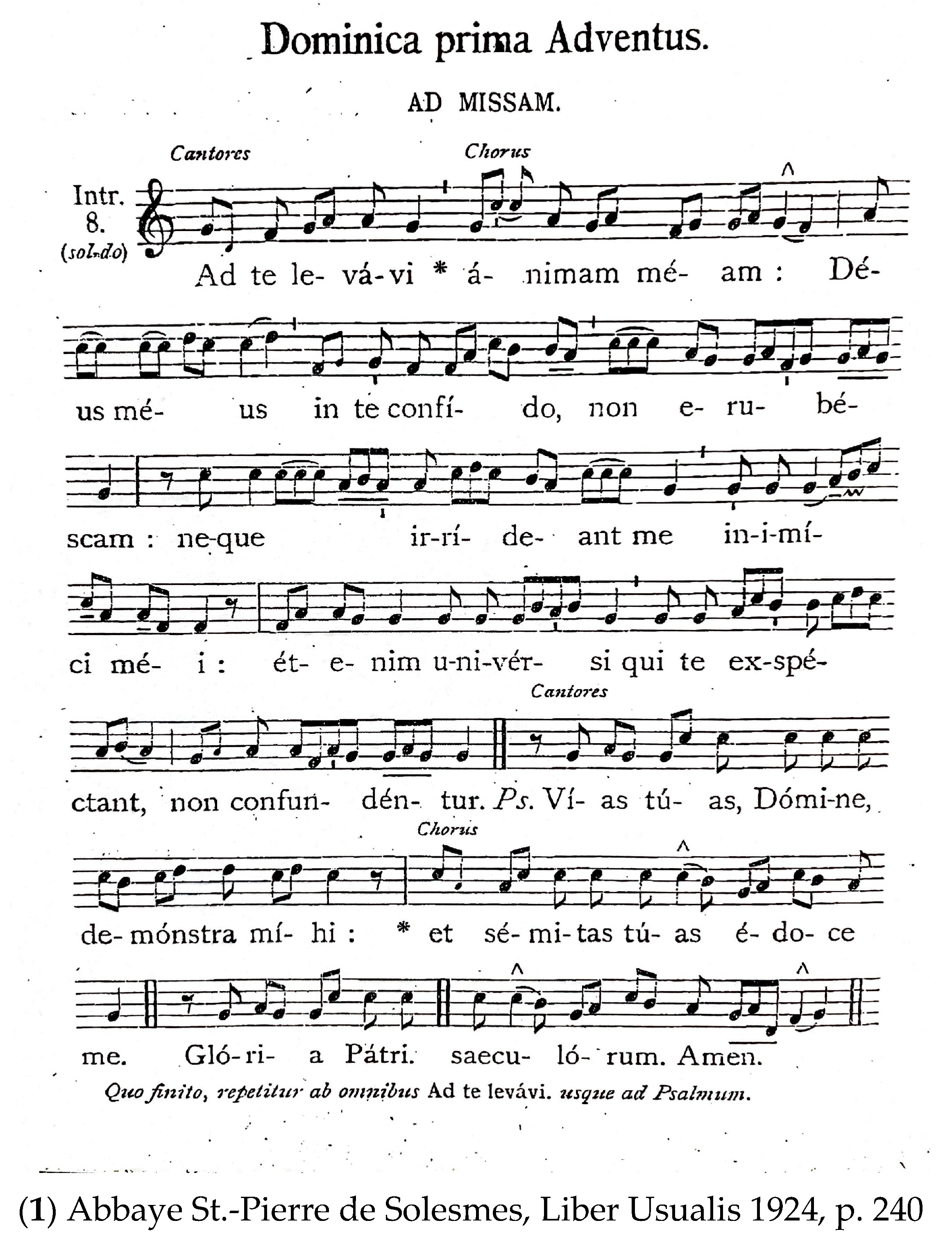

Figure 2 below, for comparison of the modern notation of the 1924 Liber Usualis with the quadratic notational forms employed in later editions).

There seems to be a continuing divide as well between the approaches to paleographic transcription of liturgical chant using quadratic notation and international musicological approaches to transcribing chant using modern staff notation and stemless note-heads, most notable in the approach to transcribing the music of Hildegard von Bingen, which typically is published for choral use using the latter approach (

Campbell et al. 1983)

1. One of the appealing features of the open-access transcriptions on the International Society of Hildegard von Bingen Studies website is the inclusion of explanatory notes, links to the codices from which the transcriptions were made, English-language translations of the Latin texts, and illustrative videos—a combination of easily accessible learning resources which precisely correlates with those requested by participants in our own study. Solesmes Abbey markets its chant notation editions towards church musicians across a broad spectrum, including religious orders, advanced singers in scholas, all the way to standard amateur church choirs with an interest in simple Vespers hymns. But perhaps the academic approach to critical editions using modern notational standards could operate as a more efficient teaching tool for standard liturgical chant for novice or non-specialist choral singers. Our study outlines a cohort of practising church musicians with a cultural disposition towards plainchant but lacking in the stylistic and notational fluency for confidently utilising Solesmes notation, and therefore it would seem that a distinct market for transcriptions in modern notation as learning editions for amateur church choirs alongside neumatic scores or facsimiles of original scores would continue to be a natural path forward for musicologists and choral score editors (a tendency which has been increasingly embraced by volunteer editors on the Choral Public Domain Library wiki site).

What may be useful for engaging both advanced choral scholars and community choral singers would be the generation of editions that juxtapose samples of manuscript facsimiles—such as those made available very early on in the

Paléographie Musicale series of manuscript facsimiles published by Solesmes Abbey (1889–c.1910), and more recently, in Dom Hourlier’s compendium of neumatic notations (

Hourlier 1996)—with transcriptions in modern notation and explanatory notes. Such editions could be easily usable by choral singers and directors without recourse to academic training in early music, meaning that an authentic and straightforward understanding of chant performance conventions could be more instantly accessible.

5. Conclusions

The findings from our exploratory case study of Irish choral singers and their attitudes to plainchant offer a commentary on the broader experience of choral musicians in anglophone contexts and their interactions with liturgical service music. The idea that plainchant is both sonically appealing and symbolic of historic sacred identities is a truism both in Ireland and beyond, for choral musicians, congregations, and secular audiences alike. At the same time, in sacred contexts, notably the Catholic church, the use of plainchant repertories has been gradually increasing internationally since the issuing of the 2007 motu proprio

Summorum Pontificum (

Muth and Montoya 2017), while simultaneously becoming a staple repertory for secular choral musicians specialising in historically informed performance practice. There is a perception, however, that “correct” plainchant performance requires erudition and scholarly knowledge outside the purview of those without academic musical training.

This study has underscored two issues here: first, that plainchant has retained its appeal in an Irish context, despite sweeping changes in approaches to liturgy and church music across different denominations, in response to increasing secularisation since the latter part of the twentieth century; second, that there is a gap to be bridged between the editing by religious houses of standard plainchant repertories for functional singing within the standard liturgy using esoteric notational forms, and the practical academic approaches to editing pre-Tridentine (sometimes liturgically obsolete) chant repertories for presentation by trained early music practitioners. Solesmes chant notation has become canonical as the means for transmitting chant for functional use among clergy and church choral musicians, but its form is so different from standard modern musical notation as to be potentially alienating for those without specialised training in solfege and Latin prosody. Charles Cole, director of the London Oratory Schola Cantorum, referring to the difficulties in interpreting chant notation, warns against “losing the sight of the wood for the trees” and suggests that

Most of what the semiology [deciphering of neumes] says seems to be towards an opening up of the text… Semiology has to be seen as an aid, not an end in itself… The singer must never feel a victim of a system and the chant must seem natural.

The kind of interpretative work performed by medievalists on editing liturgical manuscripts could be invaluable for adapting and translating core chant repertories within the Roman Gradual and the Anglican psalters for use by amateur church musicians, and such an approach may be necessary for keeping chant alive and relevant in the community, in amateur church choirs, and not just in academic contexts and among the religious professions. Presenting chant repertories in modern stemless notation alongside facsimiles of original chant manuscripts, with short explanatory notes to bridge the semiological gap between the two notational forms, could offer a genuinely fascinating and academically honest view into the medieval past via the lens of the medieval musicologist, into established chant repertories for ordinary church choirs.

The next step for our research will be to develop choral workshops utilising the above approach, where we align public domain facsimile manuscript images with Solesmes notation and modern notation in order to enable engagement among Irish choral singers with chant performance via its historical sources. Future paths for our research may include surveys of attitudes to plainchant learning and performance among experienced historical sacred music practitioners in academic and religious contexts, such as university music departments, religious communities, and professional early music ensembles.