1. Introduction

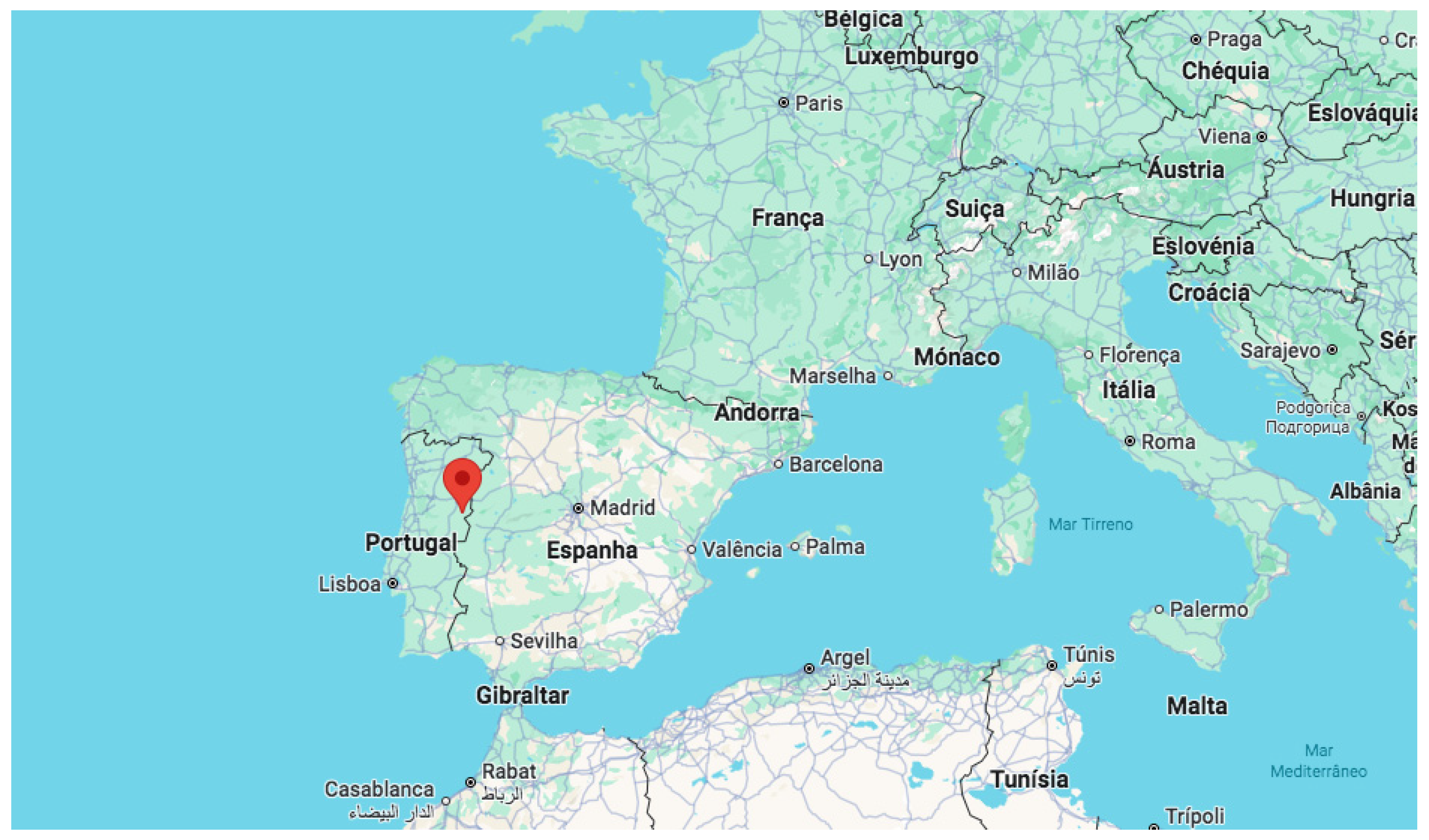

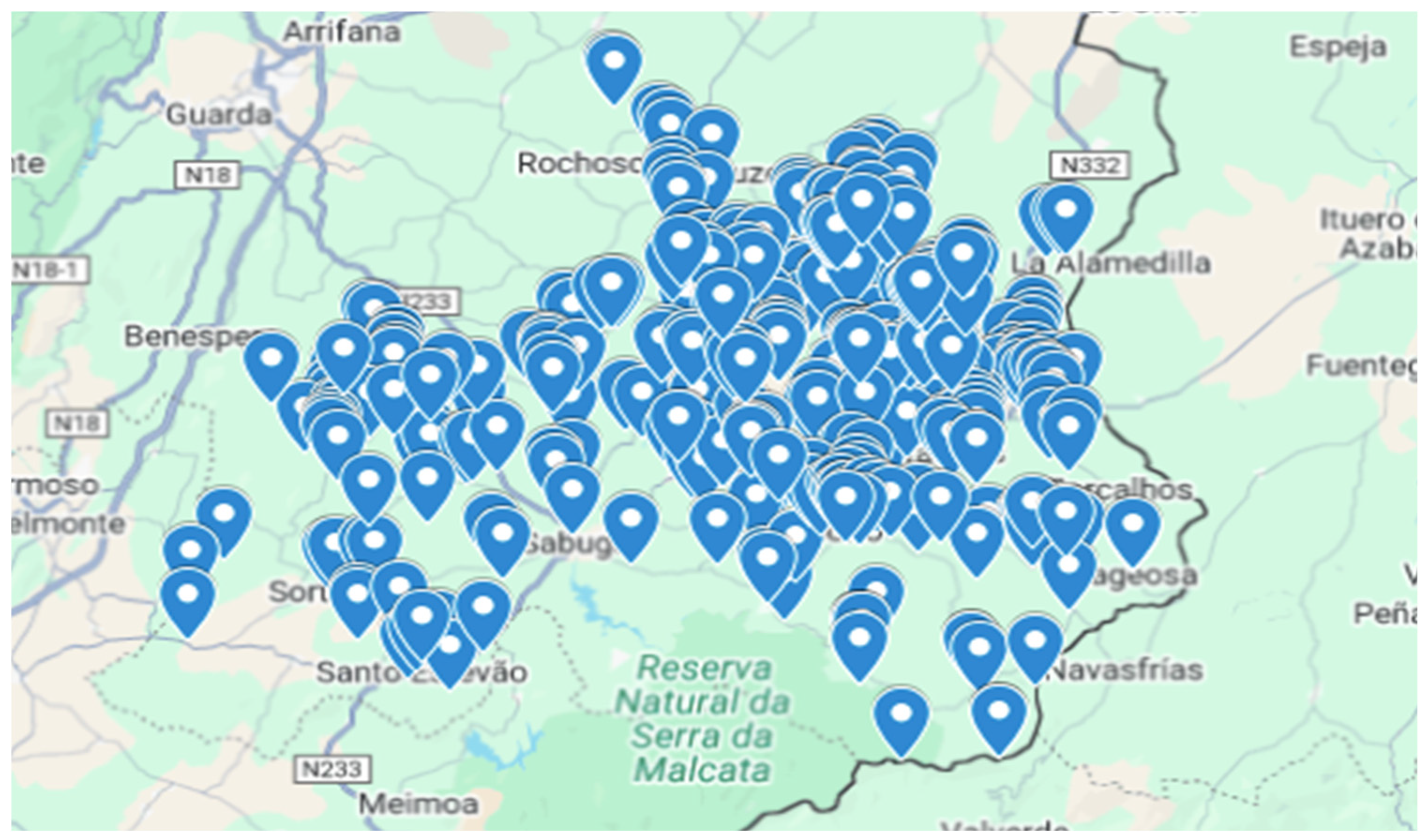

At least since the 17th century, popular religiosity has played a central role in shaping and signifying the territory, manifesting in the construction of “Alminhas” (in English, “little souls” or “shrines”), small sacred structures scattered throughout the country. The region of Sabugal, Beira Alta (

Figure 1), stands out as one of the most densely populated by these manifestations of popular faith. Additionally, in the regions of Minho and Trás-os-Montes, this type of popular religious heritage is abundant, whereas it is relatively scarce in other regions such as Alentejo.

Along with the multiplicity of typologies and scales, these examples of popular architecture have distinct stylistic affiliations. In many cases, we find a clear intersection between erudite forms and decorations (namely from the Baroque period) and a strong regional imprint, linked to the most varied aspects of popular beliefs and culture.

On paths or roads, at the entrance or inside villages, at crossroads or on top of hills, we often find small and simple religious monuments that remind us of the souls of the dead: they are the so-called “Alminhas”. They are mainly memorials built to honour and pray for the souls of the deceased, especially those in purgatory, so their primary purpose is devotional and commemorative. However, they also have a secondary, apotropaic function. Because they mark places where the living and the dead symbolically meet, they act as spiritual safeguards for travellers and communities. People believed that by showing respect and praying for the souls, they would, in return, receive protection from misfortune or evil forces.

In Antiquity, several people believed in the presence of supernatural entities along the paths. These beliefs may have been at the origin of the creation of small places of veneration and practices that, over time and with the Christianization of the peoples, contributed to the emergence of the “Alminhas” (

Torres and Osório 2016).

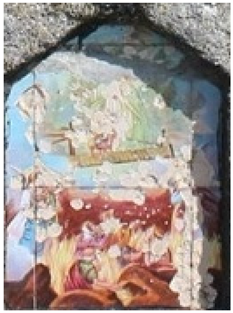

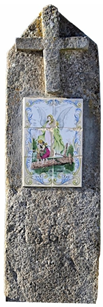

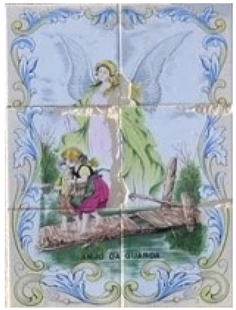

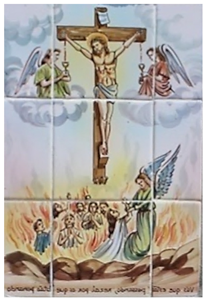

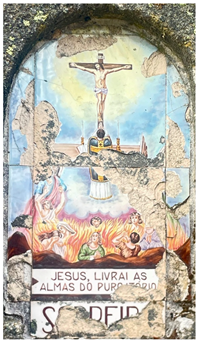

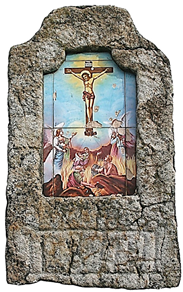

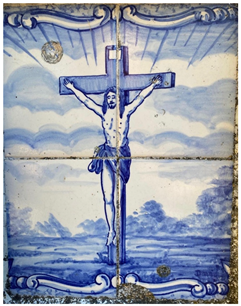

Architecturally, the “Alminhas” consist of a niche usually made of stone, topped by a cross, placed alone on a path or embedded in a rural wall, on the façade of a house, a chapel or the portal of a farm. Although the niche assumes considerable value, even for the laborious work it sometimes presents, the panel, usually embedded, is undoubtedly the central part of the construction, as it is in it that the evocation of souls is materialised. The materials used in its elaboration are diverse, ranging from wood, sheet metal, ceramics, and slate to the bottom stone of the niche itself, and to the more recent and abundant use of tile (

Silva and da Silva 2024), which has replaced most of the panels made from other materials. The taste and economic capacity of those who order it dictate the choice at each moment.

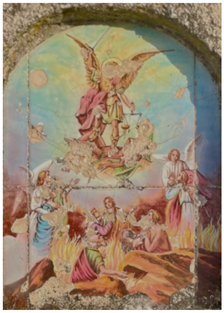

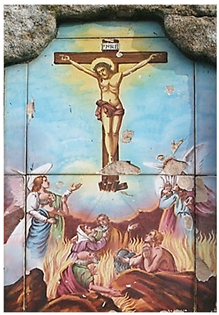

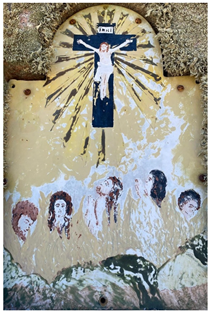

The figures on the panel are not very diverse. Christ Crucified, the Virgin Mary, or a patron saint mostly occupy the upper plane. Flanking them are almost always two angels, in a waiting position, waiting to remove the souls from the fire or, sometimes, already removing them. In the background, flanking the central figure, appear, in most cases, Our Lady (under various invocations) or local devotion saints. The lower part of the panel is intended for souls, represented anthropomorphically in a position of prayer and supplication, during which the king, the pope, the bishop, the priest or the friar may often appear, thus alerting themselves to the equality of mortals in the face of divine justice (

Silva 2001).

A hole for the introduction of alms, placed below the panel, and, in many cases, an iron grate to protect against evil intentions, complete the structure of the monument.

Although it is quite old and already present in the origins of Christianity, the cult of souls came to be represented later through the “Alminhas”. Artistic depictions of Purgatory show burning souls—identified by human figures in the flames—begging for help, while angels or saints intercede for them, symbolising purification before Heaven. These representations are prevalent in the “Alminhas”, as this study demonstrates.

The Protestant Reformation, unleashed by Martin Luther in the first half of the sixteenth century, denied the existence of purgatory and, consequently, the cult of souls (

Almeida 1964). The Counter-Reformation

1, in response to Lutheran doctrine, proclaimed the existence of purgatory in turn. Catholics, affirming their belief and devotion to souls, began to materialise them in these small monuments (

Almeida 1964).

According to

Gonçalves (

1959), in Portugal, the artistic representation of purgatory began at the end of the sixteenth century, with the “Alminhas” appearing in the seventeenth century.

The construction structure, as a religious and artistic heritage, its implantation in the territory and its importance as a testimony to the religious, spiritual, and cultural feelings of the community under study are fundamental reasons to trigger a research study. However, our attention was drawn to the large number of “Alminhas” in Beira Alta, particularly in the municipality of Sabugal, where 329 examples of this type of heritage are catalogued, a result of the intersection of religiosity and popular art. Even more so because the “Alminhas” do not exist in such large quantities in all geographical areas of Portugal.

In view of these findings, our study area is distributed in the municipality of Sabugal, located in Beira Alta, in the district of Guarda, in the northeast of Portugal. It is a border area that borders Spain, currently comprising 30 parishes and covering a geographical area of 822.70 km2.

Given the increasingly rapid degradation and even destruction of this type of religious heritage, there is a need to study and document it, particularly the panels, which have been the ones that have disappeared in greater quantity. Thus, the main objective is to survey and study various aspects of the “Alminhas” panels existing in the municipality of Sabugal.

This article focuses on beginning an inventory and study of “Alminhas”, which is developed in five sections. The first, which now ends, introduces the theme, contextualises it historically and indicates the objectives; the second approaches the existing literature and historical evolution; the third summarises the methodology used in the investigation; the fourth describes and analyses the object of study, and finally, the discussion of the themes and the conclusions reached are presented.

2. Literature Review and Historical Evolution

“Alminhas” and cruises constitute a significant body of popular religious heritage. The existing literature is scarce, and in general, it analyses the possible origins, forms, functions, historical contexts, and geographical distribution. Therefore, there is a vital need to study and preserve it.

The origins of these structures are the subject of different theories and interpretations. Some authors, including

Correia (

1916,

1937) and

Vasconcelos (

1991), propose a connection to the Roman altars dedicated to the

Lares Viales, gods of the paths and the

Lares Compitales, gods of the crossroads. This hypothesis is often based on the geographical arrangement of these oratories.

Espírito Santo (

1980) also proposes a pre-Roman origin for Portuguese oratories, also based on geographical arrangement (

Rodrigues et al. 2023). Ancient forms, such as simple wooden crosses or stone cruises, may have preceded the “Alminhas”, serving as the Church’s method of marking territory and discouraging pre-Christian practices at strategic points (

Vieira 2019). The religious phenomenon of the “Alminhas” is understandable from a historical perspective, recognising that different manifestations of the sacred varied according to times and cultures. The origin is linked to an ideology that took shape in a belief, shaped by time and history, which has grown and matured over the centuries (

Rodrigues 2010).

Popular religiosity encompasses deeply held religious feelings and a rich practice that draws on lived experiences and emotions. This experiential dimension, centred on interaction with the supernatural through the interpretation of events as having moral significance or divine intent, can be seen as a manifestation of spirituality. Religious belief emerges as the result of a process of interpretation mediated by culture and symbolic language, rather than as an immediate perception (

Martín 2009).

Popular religion is thus sometimes associated with spirituality, highlighting the growing importance of extraordinary experiences of transcendence among individuals who move away from established religious institutions. Syncretism, a characteristic of popular religiosity, also incorporates concepts associated with spirituality, such as the reinterpretation of Catholic figures (Virgin, saints) as spiritual guides (

Bastidas et al. 2021).

A crucial factor in the development and spread of the “Alminhas” was the theological formalisation of the concept of purgatory. Although discussions had already existed before the Councils of Lyon in 1274 and Florence in 1439, the Council of Trent in 1563 definitively established Purgatory as a dogma (

Rodrigues 2010). This led to a strong emphasis on the suffrage of souls through prayers, almsgiving and masses, encouraging the living to help souls in purification (

Vieira 2019). This intense devotion to the souls in purgatory became particularly prominent in Portugal, between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (

Almeida 1964).

The Confraternities and Brotherhoods dedicated to souls were fundamental in popularising the cult during the

Ancien Régime, ordering altars and disseminating specific iconography (

Cardoso 2011). The visual representation of souls suffering in flames, often depicted as naked bodies, became common from the seventeenth century onwards, sometimes taking inspiration from larger representations of purgatory located in church altarpieces (

Rodrigues 2010).

The “Alminhas” exhibit diverse morphologies, potentially evolving from ephemeral images placed on trees or walls to more permanent forms, such as monolithic structures, small chapels, niches, or oratories (

Vieira 2019). These forms, depending on the region, take on different designations and often confuse the various concepts. Similar structures, known as “Petos de Ánimas”, are referenced in Galicia from the 16th century onwards (

Bouzas 1932;

Ferro and Reboredo 2010).

From the end of the nineteenth century, a trend emerged towards simpler forms and production, characterised by more uniform compositions that reduced regional variation (

Vieira 2019).

Cruises also acquired catechetical and disciplinary roles after the Catholic Reformation. Cruises and “Alminhas” are commonly found along paths and particularly at crossroads, bridges, and territorial boundaries (

Vieira 2019).

The functions of these structures are multifaceted. The primary function of the “Alminhas” is to solicit prayers for the souls in purgatory. They also functioned as instruments of religious education or catechization (

Ladra 2013). Over time, they have become recognised as expressions of popular art and cultural manifestations that document the beliefs and behaviours of communities. They serve as a support for memory and local identity.

They can mark places perceived as sacred, such as those where atonement for sins is necessary, or places associated with historical events, disasters, or violent deaths (

Vieira 2019). Some are erected as expressions of gratitude for the supposed divine assistance. They offer significant material for the study of iconography, legends, customs and popular beliefs.

Political and social factors also impacted the “Alminhas” and cruises. The Estado Novo regime in the twentieth century, for example, actively appropriated these structures for ideological purposes, promoting their proliferation, restoration or erection as symbols of Christian Portugal (

Silva 2009;

Neto 2001). Some cruises were specifically built or received commemorative plaques during this period, for example, to mark the centenaries of 1940

2 (

Silva 2009).

Urban development and changes in infrastructure over the centuries have resulted in alterations, displacements, or the loss of specific structures (

Vieira 2019, p. 30). Modern interventions can sometimes disregard traditional forms and materials, as highlighted in the 1999 ICOMOS charter, which emphasises the need for careful physical intervention while respecting traditional methods and materials (

ICOMOS 1999).

The loss of this heritage can be attributed to several factors, including a shift in devotional focus during the Estado Novo towards the Virgin Mary, the panel being replaced by devotional images of Our Lady of Fátima, or the niche being filled with a sculpture dedicated to this Marian cult.

3. Methodology

The present study employed a qualitative methodology, focusing on direct observation and surveys of the existing “Alminhas” in the municipality of Sabugal. To identify, catalogue, and analyse these expressions of popular religiosity, fieldwork was conducted between January and June 2025, covering the 30 parishes of the municipality, where a total of 325 structures were identified (

Figure 2).

Since a survey of this type of heritage already exists, supported by the Municipality of Sabugal, we selected those that currently exist, the twenty-seven that still preserve the panel.

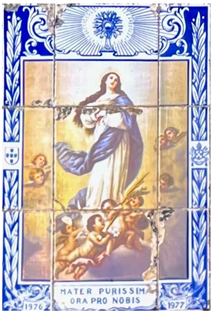

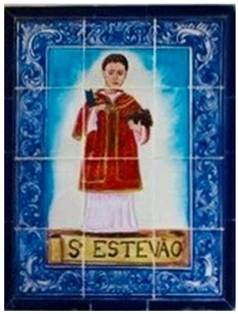

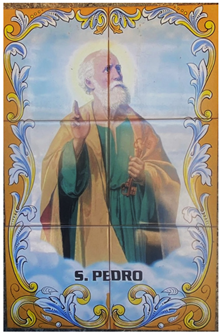

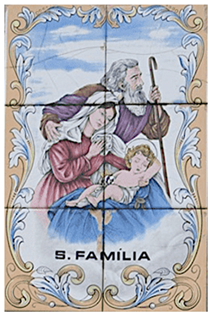

However, in most cases, it has been replaced over time by tile panels (

Figure 3). Thus, as there are few publications directly related to this theme, we searched for texts published on this type of popular religious architecture in the geographical area under study, namely in two annual magazines of the Sabugal Museum “Sabucale” (2020 and 2021 editions), edited by the Municipality of Sabugal and publications articulated with these, carried out by the anthropologist and archaeologist of the Municipality and also a monographic work by

Luís and Lages (

1979), born in this municipality.

In addition to the photographic record, each structure was georeferenced using GPS, allowing the creation of a geographic and visually accessible database. Testimonies from local inhabitants were also collected to understand the community’s perception and the current function attributed to these structures.

In addition, a documentary analysis was conducted through the consultation of bibliographic sources and existing inventories (namely, those of the Directorate-General for Cultural Heritage and local monographs) to contextualise the structures historically and, whenever possible, date their construction.

The methodology adopted thus sought to provide a comprehensive analysis of patrimonial, ethnographic, geographical, and cartographic aspects, allowing for a thorough understanding of this phenomenon within the territory of Sabugal. This approach favoured not only the inventory, but also the enhancement and preservation of a heritage at risk of disappearing.

4. Case Study: “Alminhas” and Panels of Sabugal

The “Alminhas” and the niches are a testament to the religious and cultural sentiments of various communities. They usually appear along old paths, at crossroads, and in other places to remind those who pass by of their duties to God, the Virgin, and the Saints. Often, they pray an Our Father and a Hail Mary in suffrage for the souls in purgatory (

Lopes 2015).

Its construction is diverse, faithfully reflecting a popular art that expanded in the eighteenth century as a result of the Counter-Reformation, which emerged to strengthen the religious cult of the Souls in the Catholic world. On many corners, paths, or places, the “Alminhas” appear, symbolising the cult of the dead. These are small altars where one stands to place a flower, a candle, or say a small prayer.

In the municipality studied, the “Alminhas” and their niches, as well as the cruises, are small architectural structures associated with old pilgrimage routes and paths. Their presence is familiar in strategic places, such as intersections or key geographic points, notably

portelas. In some cases, the different formats are confused, and the inhabitants also refer to the cruises and niches as “Alminhas” (

Table 1).

Some have small covers or porches. It is also common for them to be located in the centre of the villages, in some cases embedded in walls or the walls of houses. It is also common for them to be located at crossroads of old roads. Not always directly related to the journey of souls, these niches are, as a rule, places of meditation to protect hikers or travellers. In the twentieth century, there was a revaluation of the “Alminhas” and the practices associated with them. Curiously, concurrently, other modern religious formations also emerged, such as, for example, niches of “Nossa Senhora dos Caminhos” (in English, Our Lady of the paths).

Almost all the villages of Beira Alta have their own small chapel and cross, associated with liturgical rituals, notably the processions held at the time of the feast in honour of the patron saint, which are distinguished by their scale, location, and regularity of use compared to the Parish Church. In many villages, there are several chapels, although as a rule, it is not common for there to be more than one patron saint.

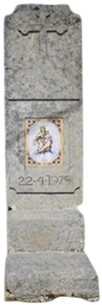

In the municipality of Sabugal, there is a wide variety of “Alminhas” with varying formats. The most common are usually made of a single piece of granite, with the niche and the cross in relief, although many that have the cross highlighted at the top. Some also have a cylindrical or rectangular lower base, but they also exist without this type of base, being integrated into walls or structures. Regardless of its size, the cross seems to be the indispensable element of these structures.

Below the cross, it is common to highlight the niche, with variable dimensions, where the image/representation existed, painted, in relief or in tile. In the older “Alminhas”, figurative representations were usually painted directly on the stone (or wood placed for this purpose). In recent cases, tiles have been used to replace older materials. Unfortunately, most niches no longer have these representations visible, in some cases due to natural wear and tear over time and in others due to undue human intervention.

Although it is not possible to determine the precise chronology of these interventions, it is observed that, from the twentieth century onwards, it became common to place tile panels as a form of reinterpretation or symbolic recovery of devotional spaces. This practice is especially evident in the niches found in the northern parishes of Sabugal. In some instances, the panels were carefully adjusted and shaped to match the original niche. In contrast, in others, this concern was not verified, with the tiles being placed outside the niche or even covering it completely. Many, below the niche, have additional decorations or legends such as dates, objects, symbols, text or letters (initials) (

Torres 2020,

2021).

The permanence of these monuments in the landscape, even when devoid of the original image—leaving only the cross or inscriptions as requests for prayer for souls—means that such structures are often reused for other forms of worship or religious expression. The placement of panels representing the Holy Family or saints of popular devotion reveals some detachment from the original meaning of the “Alminhas”, suggesting a transformation in their symbolic and devotional function.

Geographically, as in other areas of Portugal, the “Alminhas” of Sabugal are located in well-defined locations, such as along roads, paths, and crossroads (

Figure 4). The most common iconographic representations depict souls burning in the fire of purgatory, often shown as nearly naked and with their arms raised, accompanied by celestial figures who intercede on their behalf.

In the specific context of the municipality of Sabugal, there is a predominance of examples carved in a single piece of granite, featuring a niche and cross in relief, which denotes a local tradition of production and the permanence of these votive structures in public space.

The “Alminhas” that eventually received additional support for the images and were replaced by tile panels are rare, even with this type of support. Therefore, they were chosen as the focus of this study. Given the geological features of this region in Beira Alta, granite is the most commonly used material. However, accessories made of metal (such as crosses, railings, or alms boxes) are sometimes added.

The abundance of granite in the area plays a central role; it is one of the largest granite areas in Portugal, making this material readily available and affordable for construction, especially in rural contexts where other options would be scarce or too expensive. In addition, granite is highly resistant, which is particularly important in a region with a harsh climate, characterised by severe winters and significant summer thermal variations. The durability of granite ensures that these structures stand the test of time and remain visible for decades or even centuries.

The rustic aesthetics of the crudely carved granite blocks also align with the symbolism of the “Alminhas”. Its simplicity conveys a certain solemnity and humility, reflecting both the hard life of the local populations and the spiritual condition of the souls who, according to popular belief, await prayers in purgatory. This modest form directly references popular piety, which values devotional gestures over ostentation.

Another important factor is the tradition and local know-how, as many of these “Alminhas” were built by masons or workers with basic knowledge of stone carving, which explains the predominance of simple shapes, similar to one another and without much ornamentation.

It is essential to note that the “Alminhas” serve a devotional purpose rather than a monumental one. They are spiritual landmarks, in which the essential thing is not the grandeur of the play, but instead its spiritual and community purpose.

Over time, “Alminhas” were built following the tradition of marking places where a violent death had occurred, whether resulting from clashes, for example, between smugglers and authorities, since the municipality of Sabugal is a border area with strong traditions of smuggling, or more recently, of road accidents.

This “cult” of souls is associated with various rituals, carried out by congregations of believers, throughout the country, although these customs are currently more prevalent in rural areas. The Brotherhoods of Souls continue to exist in many parishes within the municipality of Sabugal, typically comprising a Judge, a treasurer, and members who hold management positions within the Brotherhood and oversee related events.

The events are directly related to funeral events, namely funerals and rituals (masses) for the souls of the deceased Brothers. To belong to the Brotherhood, members (known as Brothers) pay an annual fee of approximately €10. The Brothers, in view of the payment and belonging to the Brotherhood, benefit from rights so that the Brotherhood provides the rites of passage of their soul, namely, that they accompany the procession of their funerals, from the Church to the place where they will be buried. In this funeral procession, the members of the Brotherhood of Souls wear black cassocks and carry artefacts, including a cross, a “painting” depicting souls, lanterns, and accompany the clergy and other elements of the Church. Each Brother also has the right to have 10 Masses said for his soul. Once a month, the parish priest of the village celebrates a mass for all the deceased Brothers who belonged to this Brotherhood

3.

The survey of the iconographic representations in the images reveals a strong emphasis on Christian themes, particularly those linked to salvation, heavenly intercession, and the presence of suffering souls. In the following table (

Table 2), the iconographic representations of the oratories highlighted in the previous table are numbered.

The organisation of the themes can be achieved based on the frequency with which they appear and the combinations between the characters and sacred symbols:

- (a)

Christ crucified—the figure of Christ crucified appears in several compositions, highlighting the most recurrent theme: Christ crucified, with angels and souls on fire. This combination reinforces the idea of Christ’s redemptive sacrifice and its direct link with the salvation of souls in purgatory (6 occurrences—01 to 06);

- (b)

Christ crucified, with souls on fire (1 occurrence—07);

- (c)

Christ crucified (1 occurrence—08);

- (d)

Christ with angels and souls on fire (1 occurrences—09);

- (e)

Angel with children, angels and souls on fire (2 occurrences—12 and 13).

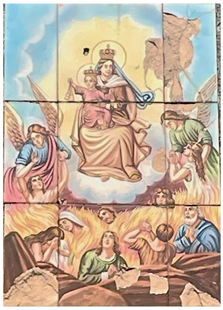

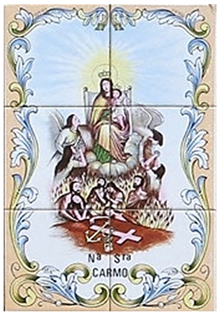

Of the 27 oratories, eight feature Christ crucified, of which seven have the presence of burning souls and six have the presence of angels. Our Lady of Mount Carmel also appears seven times, with emphasis on the following variations:

- (a)

Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Child, angels and souls on fire (3 occurrences—18, 19, 20);

- (b)

Our Lady of Mount Carmel with Child (2 occurrences—21 and 22);

- (c)

Our Lady of Mount Carmel with angels (2 occurrences—16 and 17).

Of the 27 oratories, seven feature Our Lady of Mount Carmel, 5 of which are combined with angels and Baby Jesus and three are combined with burning souls.

Our Lady of Fátima, a relatively recent cult in Portugal featuring children, angels, and souls on fire, is also represented (2 occurrences—10 and 11). The first appearance of Our Lady of Fátima, in Cova da Iria, Fátima, took place in 1917. Therefore, the two panels are from a later period, and it is notable that the “Alminhas” include modern devotional imagery within the theme of purgatory.

Other Saints and figures were also identified, including the Holy Family (2 occurrences—25 and 26); Archangel Michael (1 occurrence—15); Saint Stephen (1 occurrence—23); and Saint Peter (1 occurrence—24). The combination of Angels and Children appears twice (12 and 13).

An isolated oratory was identified—Burning Souls (1 occurrence—7) that does not contain a tile panel but is made of metal. Hence, it stands out as the only one of its kind in the entire municipality of Sabugal that maintains a panel support used in older times. Like the other “Alminhas”, it was integrated into a wall, next to the road. After detecting evidence of possible theft, a popular rescue group saved the oratory, which is currently on private property but publicly visible. This example is carved in relief and has a triangular composition at the top. Below, there are three stylised human figures, arranged side by side, with their hands on their chests—a familiar gesture in religious representations of “Alminhas”. Above these figures, one can see what appear to be decorative or symbolic elements, possibly doves or stylised leaves. Below the figures is a Latin inscription—PLALPNAM—which translates to “For Souls, Our Father, Hail Mary,” partially worn.

The presence of angels interceding for the souls of the deceased, often interpreted as those in purgatory, is depicted in several compositions. Of the 27 depictions, 18 include angels and 17 include burning souls.

The analysis of repetitions and combinations reveals that the most recurring themes centre on Christ and Marian intercession, particularly Our Lady of Mount Carmel, for the salvation of souls in purgatory, often accompanied by angels. These elements reinforce a visual discourse strongly linked to hope in salvation, the mediation of the saints and divine mercy, characteristic of popular sacred art.

The presence of the cross is visible in 22 oratories. In some cases, they are part of the granite block itself, while in others, it is placed on top of the structure.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The “Alminhas” of Sabugal are not only expressions of faith but also landmarks of collective memory and local identity. They represent the link between the living and the dead, offering as points of prayer and reflection for passersby. Their presence in strategic places, such as crossroads and ancient paths, reinforces their function as spiritual guides and protectors of travellers.

Despite their significance as expressions of popular religious culture, they lack a comprehensive inventory, which is essential for protecting this type of religious heritage. Current inventories lack systematisation, and no scientifically based study prioritises tourist-cultural dissemination above all else, leading to a holistic approach. The inventory process involves extensive fieldwork, detailed photographic documentation, and data collection on location, chronology, material, morphology, iconography, and conservation status. Challenges to preserving these structures include overgrown vegetation, moss and lichen buildup, vandalism, and structural damage, including collapses and fractures.

None of the objects inventoried in this study were found registered in the Information System for Architectural Heritage (SIPA), an information system relevant to architectural heritage managed by the Directorate-General for Cultural Heritage (DGPC), which reveals a manifest lack of interest in this type of heritage on the part of the state bodies in charge.

Although this is a tiny sample of 27 “Alminhas”, compared to the 325 that still exist today, the chronological analysis reveals a tendency to construct them in two distinct periods: in the nineteenth century and later in the 1970s of the twentieth century (

Table 3). Of the 27 studied, only 12 have the date of construction, and 5 have the date of placement of the tile panel; the oldest is from 1949.

Regarding the nineteenth century, there are five; others may have been built during that time, but we do not have their construction dates. In some cases, only the replacement date is provided, while in most cases, it is for previous panels. The oldest dates back to 1847, and the most recent to 1883.

Regarding the 70s of the twentieth century, there are seven, the two most recent being from 1979. In this decade, there appears to be an increase in the construction or replacement of panels, accompanied by the removal of existing ones. There are two identical panels in the same parish, Lameiras de Baixo (Pousafoles), and of the exact chronology.

The iconographic analysis of the 27 oratories in the municipality of Sabugal reveals a strong predominance of Christian themes with an emphasis on the salvation of souls from purgatory. This survey reveals the enduring popularity of a religiosity rooted in the doctrines of intercession and divine mercy, with a particular emphasis on the figure of Christ crucified and Our Lady of Mount Carmel as a privileged intercessor.

The figure of Christ crucified, present in eight oratories, appears in a particularly expressive manner, often accompanied by angels (in eight instances) and burning souls (in seven instances). This iconographic combination conveys to the idea of Christ as redeemer of souls in purgatory, reinforcing the role of sacrifice in the economy of salvation. The repetition of this representation testifies to its central place in the local devotional imagination, serving as a powerful symbol of hope and redemption.

Our Lady of Mount Carmel appears in 7 oratories, in 5 of which she appears accompanied by the Child Jesus and angels, and in 3 associated with burning souls. This configuration is directly associated with the dogma of the scapular and the promise of the liberation of souls from purgatory. Her presence stands out as one of the most evident forms of Marian intercession, serving as a sign of the Carmelite cult that had a profound impact in Portugal, especially after the Counter-Reformation.

There is also an isolated representation of Our Lady of Fátima, accompanied by angels and images of burning souls. This presence, although rare, evidences an attempt to integrate elements of contemporary worship into the traditional repertoire, signalling the vitality and adaptability of popular religiosity, as we have already mentioned.

The presence of angels in 19 of the 27 oratories reinforces the mediating and celestial character of these figures, primarily when associated with burning souls (17 occurrences). The motif of suffering souls is transversal, arising with great frequency and almost always in interaction with intercessory figures, such as Christ, Mary or the angels. This imagetic insistence underlines the concern with salvation after death and the role of prayer and divine mediation in the relief of purgatorial pains.

Among the secondary representations, the Holy Family (2 occurrences), St. Peter, St. Stephen, and the combination of angels and children (2 occurrences) appear. These elements indicate a thematic extension that, although less recurrent, enriches the whole with different devotional nuances.

Also noteworthy is the unique oratory in high relief, number 27, representing the Souls in flames, which lacks a tile panel and is distinguished as the only example of its kind in the entire municipality. This oratory, possibly of a more rudimentary or spontaneous nature, can testify to a particularly local or personal devotion, focused exclusively on the memory and suffrage of the souls in purgatory, without conventional iconographic mediations. Its uniqueness points to the diversity of devotional practices and materialities present in the territory. The sculptural work in granite is reminiscent of the

Petos de Ànimas Galicians. Petos de Ánimas (meaning ‘Boxes for souls’ in English are small religious shrines commonly found in rural areas of Galicia, Spain, very similar to the “Alminhas” (

Ladra 2013;

Rodrigues 2010). Both are used for praying for the dead, placed by roadsides, and dedicated to the souls in Purgatory, according to Catholic belief.

Finally, the presence of the cross in 22 oratories confirms the centrality of the symbol of Christ’s Passion in popular religiosity. Its integration into the architectural structure of the oratories—whether carved in granite or placed atop the structure—reveals the visual continuity of the crucifixion as an element that brings together faith and devotional practice.

The Portuguese “Alminhas” can, in some ways, be incorporated into a broader tradition of small devotional practices that characterise the rural and urban landscapes of southern Europe. These structures serve to mark the presence of the sacred in daily life, seek divine protection for travellers, and keep the memory of the dead alive (

Rodrigues 2010). However, the “Alminhas” possess unique features that give them a distinct identity within this shared cultural universe. Like Italian

votive capitelli, Spanish small shrines or altars, and Greek roadside sanctuaries, Portuguese “Alminhas” are expressions of popular religiosity. These religious objects function as symbolic markers connecting secular space with the divine, often placed at passageways and closely linked to the daily lives of local communities. They also share a votive and intercessory purpose, along with iconography that references protection, penitence, and the salvation of souls (

Rodrigues 2010). Despite these similarities, “Alminhas” are distinguished by their near-exclusive dedication to the souls in purgatory, making them a uniquely Portuguese expression of post-Tridentine Catholic devotion. While Italian capitelli or Spanish niches often honour protective saints, the Virgin Mary, or Christ, “Alminhas” repeatedly invoke penitential souls, depicted in flames and awaiting the prayers of the living. This specific theological focus reflects the strong influence of purgatory doctrine in Portuguese religious culture from the 17th to the 19th centuries, as well as the practice of praying for souls as a spiritual act of charity. The physical and architectural design of the “Alminhas” also demonstrates this: their simplicity contrasts with other European votive forms, emphasising the community and popular nature of this devotion. Their social role is equally distinct: as passersby walk by, they recite a brief prayer and sometimes leave an offering, a practice that reinforces the ongoing interaction between public space, the memory of the deceased, and daily devotion. In summary, although “Alminhas” share with other roadside sanctuaries of southern Europe the votive character and mediating role between humans and the divine, they are distinguished by their specific focus—the souls in purgatory—and by their subtle yet consistent integration into the Portuguese cultural landscape. Their uniqueness lies precisely in this blend of popular religiosity, collective memory, and the sacred’s physical presence in everyday spaces.

The iconographic analysis of the oratories of the municipality of Sabugal allows us to conclude that local popular religiosity is organised around a set of themes central to Catholic doctrine: the sacrifice of Christ, the intercession of the Virgin Mary (especially under the invocation of Our Lady of Mount Carmel), angelic mediation and hope in the salvation of souls in purgatory.

The frequency with which these elements emerge, as well as their combinations, reveals a consistent and articulate visual discourse, deeply rooted in the Christian tradition. This discourse reinforces values such as divine mercy, hope in eternal life and the importance of the intercession the saints and prayer for souls. At the same time, the diversity of representations—including specific saints, the presence of children, and the incorporation of elements of modern worship such as Our Lady of Fátima—testifies to the vitality and continual adaptation of the popular faith.

The oratories analysed are not only artistic and architectural testimonies, but also true landmarks of a community’s spirituality, expressed visually through powerful and universally recognisable symbols within the context of Catholicism. They represent a lived faith, in which the visible communicates the invisible and in which suffering, hope, and salvation meet in permanent dialogue.

The material used to support the niches is, in all cases, granite and structurally they are all very similar, without sculptural elaborations of relief or with characteristics that allow a more precise dating, as is the case with the baroque ones found in Minho, for example, in Paredes de Coura (

Silva and da Silva 2024). In fact, in most cases, these are simple columns, surmounted or engraved with crosses and a small niche dug, but with little depth. The simplicity of these oratories reflects the simplicity of this territory, composed chiefly of small rural towns and without extraordinary manifestations of wealth or ostentation, except for some religious architecture, which stands out from the rest of the landscape.

Unfortunately, replacing the original panels with relatively recent tiles detracts from many of their original characteristics. Because these structures are located in areas of passage, this territory borders Spain, and many of its ancient paths were used as smuggling routes, a common practice in border territories like this one. Over time, they have been subject to theft and vandalism; additionally, because they are exposed, they are also susceptible to the natural wear and tear caused by the adverse weather conditions of this region. It is also noticeable that some contemporary panels have replaced previous panels.

“Alminha” 03, built in 1907, has a fascinating, unusual and rare inscription, which attests to the fact that human action is an essential factor, probably the most common, in terms of risks and acts of vandalism, in relation to this type of heritage: Whoever breaks the old one, pays for a new one. The phrase may also suggest that it is a reconstruction and serves as a warning against repeating the act of vandalism.

Proposals to protect this heritage include advocating for its legal recognition and safeguarding, as outlined in Law No. 107/2001, which provides the foundation for cultural heritage protection. This involves establishing a continuous maintenance plan and ensuring that experts perform restorations using traditional methods and materials. It is also important to develop educational initiatives to increase public awareness. However, since managing public assets faces significant challenges, such as limited human and financial resources, various associations and other entities across the country have contributed to its inventory and raised awareness about its preservation. Furthermore, this situation is familiar to all those referred to as “minor” cultural heritage, such as religious ethnographic relics, which also fall into this category.

Based on the results presented, future research on the “Alminhas” of the municipality of Sabugal can explore different complementary avenues. First, a comparative study of oratories from other municipalities in Beira Alta and other regions of Portugal would be valuable for identifying iconographic, technical, and material similarities and differences used in both the construction of the structures and the panels, as well as in the devotional practices. A second approach could focus on material and conservation analysis, including laboratory tests of tiles, mortars, and pigments to better understand the original techniques and guide suitable restoration efforts.

Another promising area of research is the ethnographic and immaterial aspect, which enriches the collection of oral testimonies about rituals, prayers, and traditions related to the “Alminhas” before these memories fade with the ageing local population. Creating a georeferenced digital archive that includes high-resolution photographs, historical records, and interviews would not only preserve this information but also make it accessible to researchers, schools, and visitors.

Regarding preservation solutions, several options can be recommended, such as establishing preventive conservation programmes with regular monitoring of the condition of oratories and small maintenance interventions to prevent structural deterioration; forming partnerships between municipalities, parishes, and higher education institutions to involve specialists in this type of heritage and in conservation and restoration; promoting tourism and educational initiatives, for example, through interpretive itineraries and signage to raise awareness among residents and visitors about the heritage value of the “Alminhas”; or even applying for national and European heritage grants and funds to secure financial resources for restoration and dissemination. In this way, the following steps combine multidisciplinary research and tangible preservation efforts, ensuring that the “Alminhas” remain not only artistic and religious symbols but also living parts of the cultural identity of Sabugal and other areas.

(and a spiral).

(and a spiral).