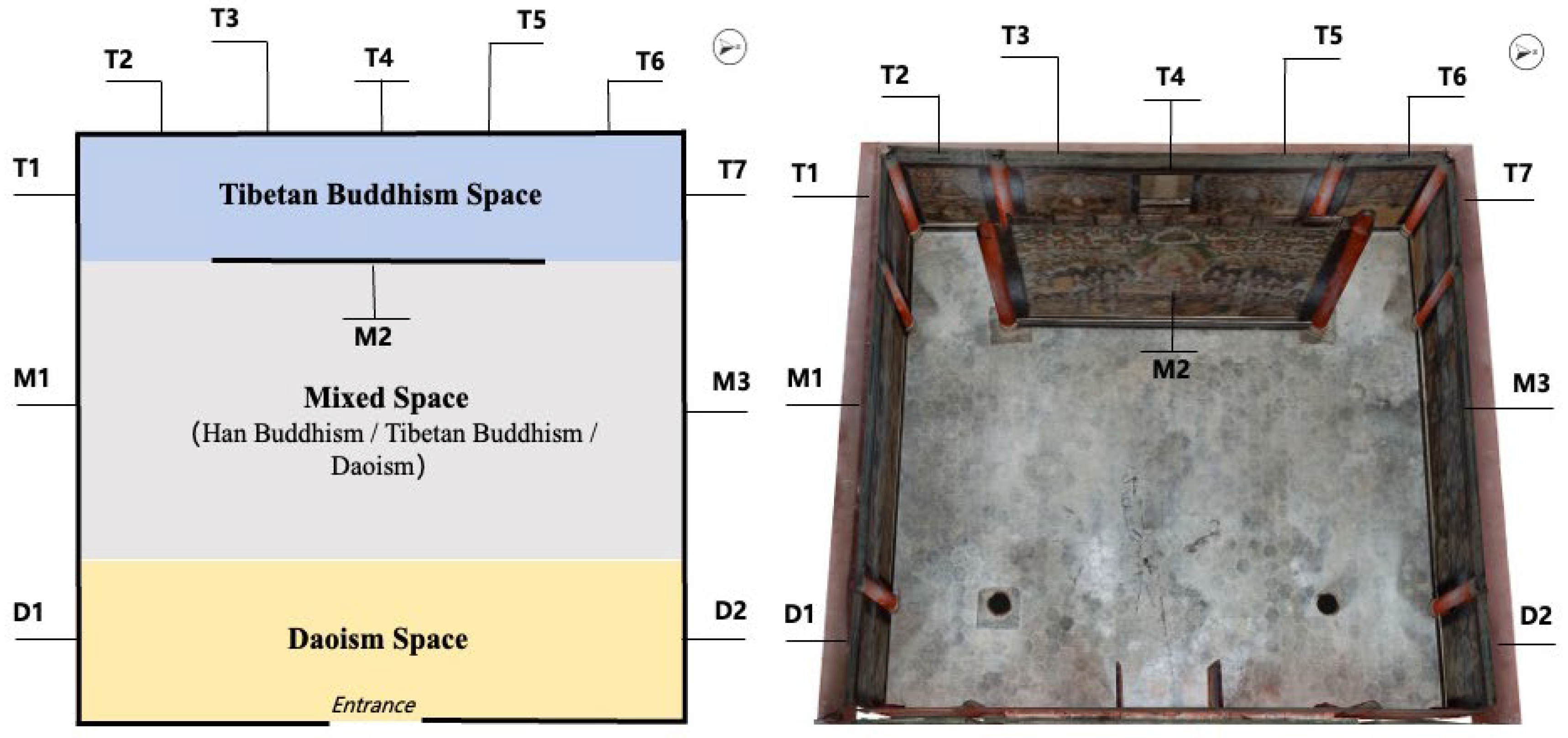

2.1. Entrance—The Introductory Space of Daoism

The murals in the eastern entrance zone—

Marīcī (D1) on the south wall and The

Three Officials of Heaven, Earth, and Water (

tiandi shui sanguan, D2) on the corresponding north wall—constitute the Daoist-themed, Han-style facade of Dabaoji Palace (

Figure 3). Situated at the forefront of the hall, this space functions as a ritual threshold, enacting the visual narrative of Han propriety (

hanli 汉礼) and introducing visitors into a sacred environment. The rise of Daoism in Ming-dynasty Lijiang was closely linked to the influx of Han cultural influence and the Ming court’s frontier policy. Although the regional chieftain system preserved local autonomy by ruling according to local customs, it operated simultaneously with the imperial agenda of transforming frontier civilizations through Han cultural values characterized by Confucian teachings (

N. Wang 2021). As a core component of Han culture, Daoism provided a channel for the Naxi elite to engage in imperial ideology while navigating their own cultural identity.

Among the Mu chieftains, Mu Gong and Mu Zeng demonstrated deep personal and political devotions in Daoist practice. Their commitment extended from Daoist alchemy and poetry to aspirations for immortality, while also manifesting in temple patronage and public rituals aimed at securing cosmic order and imperial prosperity (

N. Wang 2021). The Daoist space of Dabaoji Palace thus reflects not only spiritual devotion but also strategic engagement with Ming statecraft, establishing a visual declaration of the Mu’s allegiance to Ming authority and alignment with Han traditions. The iconography of the Daoist murals also illustrates how the Mu chieftains actively integrated Daoism into the local Naxi cultural environment and their intermediary role between local society and the imperial state.

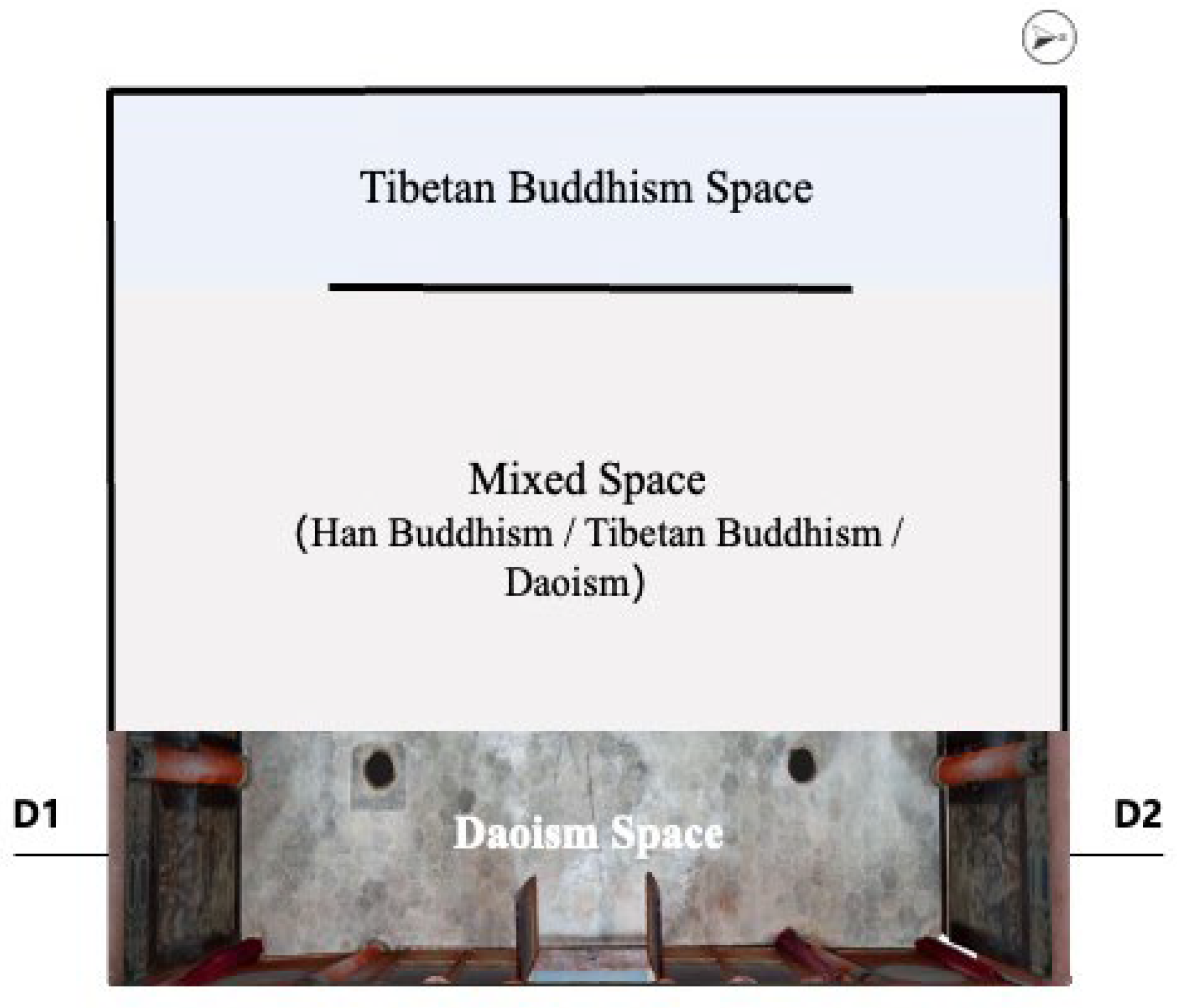

As shown in

Figure 4, the central deity of mural D1 is identified by its inscription as the Tibetan deity

Mārīcī (

Xiong et al. 2013). However, iconographic evidence suggests a more accurate identification as

Doumu Yuanjun, the Daoist Mother of the Big Dipper, based on the surrounding Daoist figures (

P. Yan 2023). Beneath her are the Four Thunder Generals of Deng, Xin, Zhang, and Tao, who serve under her command and symbolically represent the Mu chieftains’ military authority sanctioned by the Ming court for guarding the Sino-Tibetan frontier. Above her, the Heavenly Lord of Dao and its Virtue (

Daode Tianzun 道德天尊), one of the Daoist Three Pure Ones, occupies the top central position, flanked by the Four Heavenly Ministers (

Siyu 四御), high-ranking Daoist deities serving directly under the Three Pure Ones. This celestial hierarchy visually encodes the Mu chieftains’ political role as regional governors within the Ming imperial structure, projecting their identity as loyal frontier agents through Daoist cosmology and iconographic symbolism.

In mural D2 (

Figure 5), the

Three Officials of Heaven, Earth, and Water, the top central figure presents the Heavenly Lord of Spiritual Treasures (

Lingbao Tianzun 灵宝天尊), whose elevated position parallels that of Daode Tianzun in mural D1, together articulating the Mu chieftains’ aspirations for transcendence, longevity, and harmony through Daoist cosmology. To his left appears

Wenchang Dijun (文昌帝君), the God of Culture and Literature, which is associated with the Mu family’s promotion of Confucian learning; to his right is

Zhenwu Dadi (真武大帝), the God of True Valiance, whose martial associations reference the Mu chieftains’ campaigns against Tibetan polities and their defense of the northwest Yunnan frontier (

An 2014). As

N. Wang (

2021) notes,

Zhenwu also connoted unwavering loyalty to the empire, further supporting the Mu’s image as devoted vassals of the Ming. The triad of the Three Officials and the thunder gods arrayed below them address popular concerns for prosperity, weather regulation, and protection from calamities (

P. Yan 2023). Notably, the attire of the divine figures visually encodes political status. The Three Officials and their attendants are dressed in zuoren (左衽) left-lapel robes commonly associated with local Naxi elites, while Lingbao Tianzun wears a youren (右衽) right-lapel robe, symbolizing Han Chinese and imperial authority (

P. Yan 2023). This contrast in attire and divine ranking highlights the Mu chieftains’ intermediary role between indigenous identity and imperial loyalty.

Similarly to

Clunas (

2004) concept of “visibility strategy,” the Daoist imagery at the palace entrance functions as a politically charged visual rhetoric through which the Mu family constructs its political, social, and cultural status as frontier elites within the Han cultural sphere, expressing fidelity to the Ming court while reinforcing local authority. By appropriating figures such as

Wenchang and

Zhenwu, the Mu chieftains reframed Daoist deities as proxies for Confucian virtue, aligning themselves with the ideologies of the Ming empire. As a spatial and ritual threshold, the Daoist ensemble at the palace entrance constructs a distinctive Han-style facade that performs both ritual and ideological functions. It marks the initial transition from secular to sacred space while visually declaring the Mu chieftains’ cultural and political stance. Positioned within the Ming dynasty’s broader civilizing campaign of

yong xia bian yi (用夏变夷, “transforming the ethnic minorities through Chinese values”), this Daoist facade functions as a public-facing proclamation of the Mu chieftains’ identification with Han Chinese values while simultaneously asserting their status as recognized frontier rulers. As the “opening stage” within the palace’s spatial narrative, it establishes the tone for the entire visual program. Through carefully curated Han cultural norms and imperial symbology, the Daoist space constructs a narrative of political legitimacy and cultural sophistication central to the Mu chieftains’ self-representation.

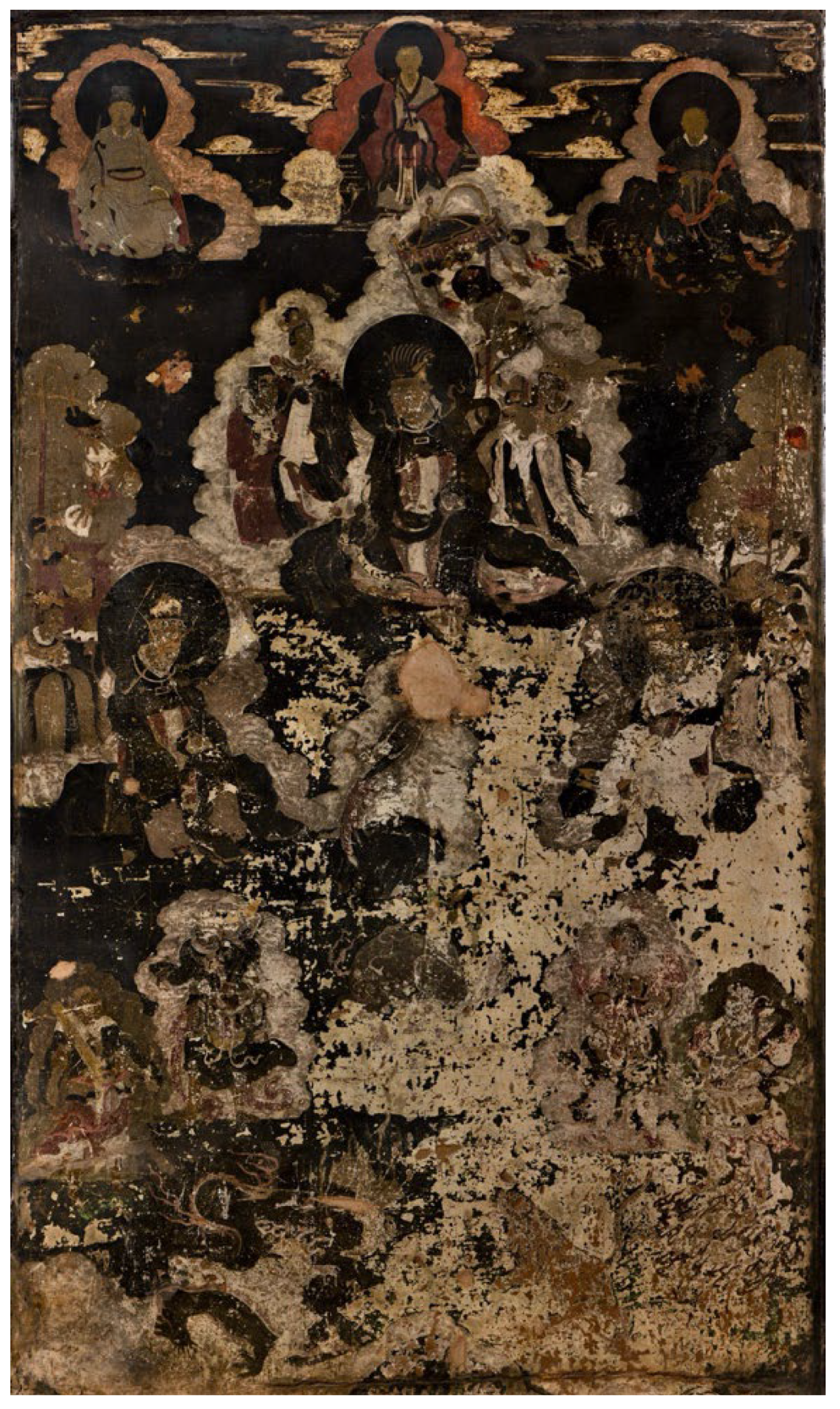

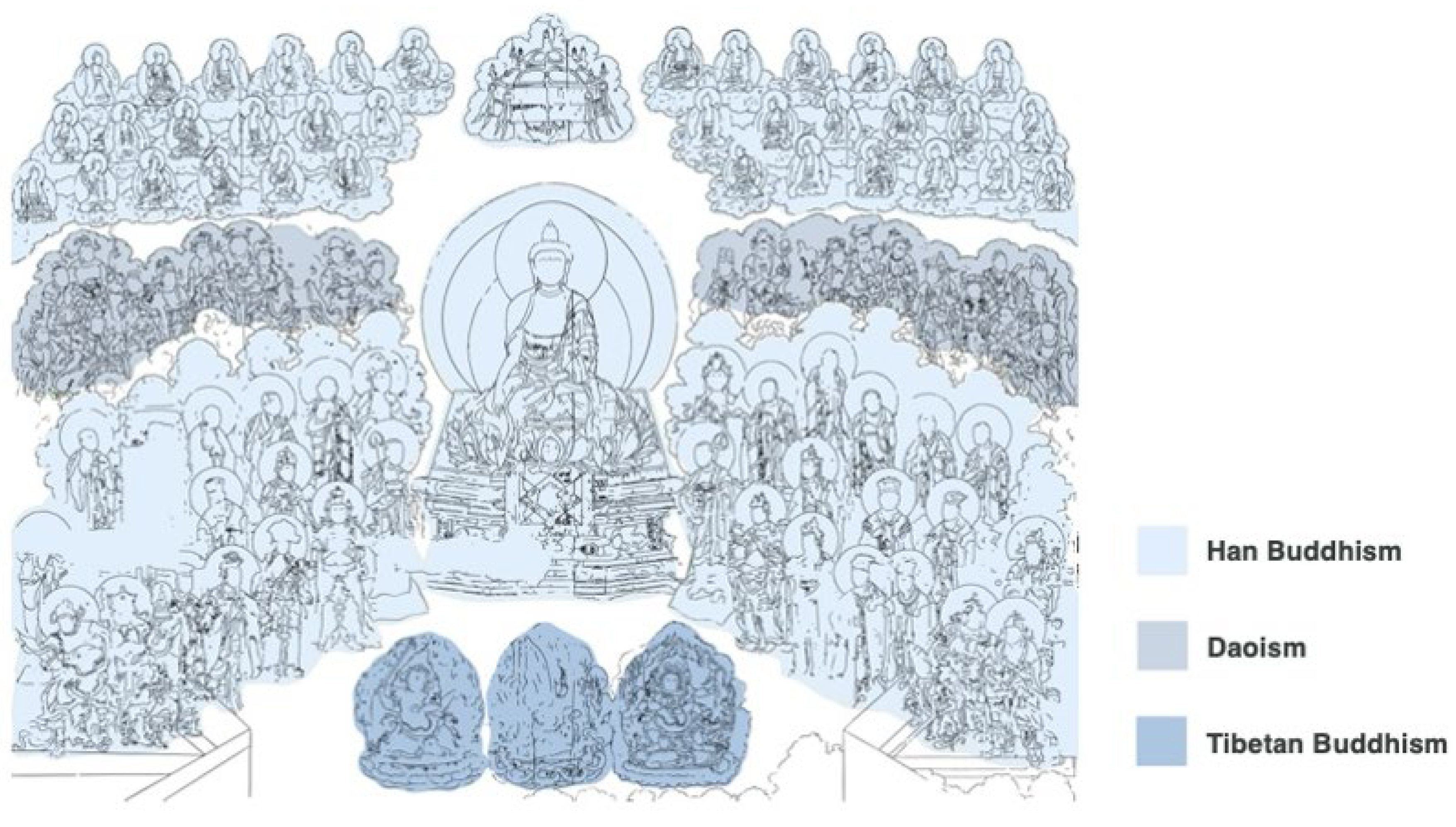

2.2. Central Zone: A Syncretic Space Dominated by Han Buddhism

Following the establishment of a Han-style Daoist facade, mural M2 on the central screen wall (originally the back screen of a now-lost Buddhist altar) draws viewers’ attention towards the palace’s main hall, a syncretic space largely shaped by Han Buddhist visual culture. This central zone reflects the Mu chieftains’ visual strategy of multi-religious coexistence to assert local agency beyond passive assimilation into the imperial order. Occupying the most prominent position within the hall, the area comprises three murals:

The Assembly of Śākyamuni Buddha (M2) on the screen wall,

The Mahāmāyūrī Water-Land Assemblage (M1) on the south wall, and Scenes from the Guanyin Pumen (M3) on the north wall (

Figure 6). Though all three reflect Han Buddhist esthetics and liturgical themes, they also incorporate Tibetan and Daoist elements, forming a visually cohesive syncretic space predominated by Han religious idioms.

Situated at the intersection of Han and Tibetan cultural spheres, Lijiang provided fertile ground for the Mu chieftains’ pluralistic religious policy. Their patronage extended from major Tibetan Kagyü monasteries to Han Buddhist temples such as Liuli Hall and Xitan Temple, while local ritual life encompassed both Daoist Star Worship rites (

Chaodouhui 朝斗会) and Buddhist Maitreya Assemblies (

Milao Hui 弥老会). Large-scale rituals often involved Daoist priests, Tibetan lamas, and Naxi Dongba shamans performing jointly (

F. Yang 1996). The

Dangmeikongpu (当美空普) ritual, translated as “Opening the Gate of the Dabaoji Palace in Baisha”, suggests that Dabaoji Palace likely functioned as a site for such multi-religious rites (

F. Yang 1996).

In

The Mahāmāyūrī Assemblage (M1,

Figure 7), the central deity is identified by inscription as the Tibetan

Mahāmāyūrī (

Xiong et al. 2013), also venerated as the Great Peacock King in Han Buddhism. While her iconography—three heads, eight arms, tantric implements—derives from Tibetan esoteric norms,

1 it also conforms to Chinese representations: a compassionate bodhisattva-like feminine form on a lotus throne upheld by a spreading peacock, consistent with Tang-style Chinese representations in the

Mahāmāyūrī Vidyārājñī Sūtra translated by Amoghavajra (

Chai 2023). She forms a triadic composition with the two attendant bodhisattvas below her, echoing traditional Chinese Buddhist assembly formats (

Liao 2010). This composition embodies Mahāyāna Buddhism ideals of salvation and is closely associated with Han Chinese rituals of dragon worship, avoidance of calamities, and prayer for rain (

Chai 2023).

The surrounding pantheon, featuring nearly 100 deities including the Eight Great Bodhisattvas, the Twenty-Eight Mansions (

Ershiba Xiu 二十八宿), thunder gods, earth deities, Sixteen Arhats, and the Four Heavenly Kings, embodies classic Han cosmology. As

Debreczeny (

2009) mentions, the composition resembles Water-Land Ritual (

shuilu fahui 水陆法会) paintings prevalent in late-Ming Buddhist temples. The genre can be traced back to Emperor Liang Wudi’s repentance ritual and Tang esoteric manuals, codified during the Song dynasty in Yang E’s Shuilu Yi, and later became central to Chinese liturgical representations (

Zhou 2006;

Dai 2008). The visual integration of Daoist, Buddhist, and popular Chinese folk deities in

shuilu fahui responds to common worldly prayers for protection from calamities (

Q. Liu 2021), aligning the Mu chieftains with Ming state rituals and projecting their agency as frontier stabilizers during periods of crisis.

Importantly, while the Mahāmāyūrī Assembly retains Han stylistic conventions, it tactically incorporates Tibetan elements in a less prominent position. For example, her mandala appears only as a miniature beneath her seat rather than dominating the composition as seen in traditional Tibetan thangkas. Through a visual hierarchy that prioritizes Han Buddhist conventions with a controlled amount of Tibetan imagery, the Mu chieftains project themselves as governors of the Yunnan-Tibetan borders in accordance with Ming policies.

On the north wall, directly opposite to the

Mahāmāyūrī Water-Land Assemblage, is

Scenes from the Guanyin Pumen (M3,

Figure 8), an illustrated episode from the

Lotus Sūtra in which Avalokiteśvāra (

Guanyin 观音), the Han bodhisattva of compassion, rescues sentient beings from various forms of suffering (

Z. Yang 2018). The mural articulates the Mahāyāna Buddhist ideal of universal salvation and reflects Guanyin’s central role in Han Buddhist devotional practice. The juxtaposition of

Mahāmāyūrī and

Guanyin echoes the established traditions both in state ritual and popular worship, where the two sutras were venerated as core texts of Han esoteric Buddhism (

Y. Yan 2006). On the top layer are the Ten Manifestations of Avalokiteśvāra, and the Four Heavenly Kings occupy the bottom corners as standard iconographic features in Chinese Buddhist art. Applying the style of

jingbian 经变 (sutra transformation tableaux) paintings, the mural arranges different narrative episodes in a symmetrical zigzag composition around the central figure, a typical visual narrative structure in Chinese pictorial exegesis (

Lin 2012). The tableau not only demonstrates the prominence of Han Buddhist visual traditions but also reinforces the Mu chieftains’ alignment with widely accepted liturgical and iconographic forms in Chinese Buddhism.

On the central screen wall is the

Assembly of Śākyamuni Buddha (M2,

Figure 9),

2 which bears no Tibetan inscriptions. Its theme derives from the Assembly of Amitayus (Buddha of Immeasurable Life) in the

Mahāratnakūṭa Sūtra of Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism, depicting Śākyamuni preaching to a large divine assembly. The main figure of Śākyamuni appears in a red kasaya adorned with golden floral scrolls, a traditional Chinese pattern design indicating clear influence from Ming imperial Buddhist art. Above him, three rows of small Buddhas represent the Thirty-Five Buddhas of Repentance and one Śākyamuni, conforming to the “thousand-Buddha” iconographic convention found in Chinese Buddhist cave temples and mural programs (

S. Wang 2022). The middle register presents bodhisattvas and Daoist deities; the bottom includes three Tibetan wrathful deities, with Mahākāla directly beneath Śākyamuni and the Four Heavenly Kings at the corners. This layered ensemble situates the mural as the visual center of the syncretic space, embedding Chinese Buddhist narrative structures and esthetics at the heart of the hall’s religious topography. It articulates the Mu chieftains’ inclusive strategy of aligning with Ming imperial authority while acknowledging their role as Tibetan frontier governors.

Originally positioned behind a now-lost central altar, the mural once formed a backdrop for the central Buddhist statuary. Its role is similar to the rear screen of the central altar in a typical Mogao Cave, which brings the object of worship from the rear to the center of the religious space (

Wu 2022). Despite the altar’s absence, the mural remains as the hall’s undisputed focal point, drawing the viewer’s gaze to the central elevated image of Śākyamuni immediately upon entry. As a spatial partition, it reshapes the hall’s internal hierarchy and reinforces its symmetrical axis, visually conferring an emperor-like presence upon the central Buddha. While incorporating deities from Han Buddhism, Daoism, and Tibetan Buddhism, the mural stylistically fuses the line techniques and esthetic features of Ming court-style figure paintings represented by the murals of Fahai Temple in Beijing, including its application of the “Eighteen Modes of Brushwork,” phoenix coronets (

Feng Guan 凤冠) worn by noblewomen, courtly robes (

chaofu 朝服), and the

Liang Guan 梁冠of Ming officials (

S. Liu 2021). Meanwhile, the mural’s overall hierarchical composition assembles the layout of Three Realms in Tibetan thangkas (

Xie 2004). The fusion of Han and Tibetan Buddhist visual traditions articulates the Mu chieftains’ inclusive strategy of aligning with Ming imperial authority while acknowledging their role as Tibetan frontier governors, reinforcing their role as active curators of a pluralistic religious program.

As shown in

Figure 10, Han Buddhist and Daoist deities dominate the composition in terms of quantity and hierarchy, while only three Tibetan Dharmapālas appear beneath Śākyamuni as protector deities. The central Śākyamuni Buddha adheres to Han Buddhist iconography, with an

uṣṇīṣa and plain

kasaya without jewelry decorations, distinguishing him from the Tibetan mode. This Han-dominated visual emphasis aligns with Naxi’s political developments in the early Ming: following the conquest of Tibet and Yunnan, the Naxi leader submitted to the Ming and was granted the hereditary title “Mu” as the native chieftain of Lijiang (

Xiong 2006). Under Ming frontier policy, the Mu’s authority expanded into historically Tibetan regions, including Diqing, Nujiang, and Batang (

Xiong 2006). Their legitimacy was further solidified through military service to the court, including suppression of rebellions and defense against Tibetan incursions (

N. Wang 2021).

Interestingly, the inclusion of Tibetan Dharmapālas beneath Śākyamuni does not merely illustrate a hierarchical arrangement but instead creates a visual

third space3, a deliberate cultural hybrid that resists assimilation into either Han or Tibetan models but transcends both. Rather than submitting to a single tradition, this creative juxtaposition suggests a new paradigm that asserts the Mu chieftains’ local agency and authority in negotiating imperial and frontier identities. The mural thus embodies their core political-religious strategy of affirming clear allegiance to the Ming court while signaling effective governance over Tibetan regions. While the Mu chieftains were officially Ming subjects, they operated as semi-autonomous vassals, managing regional affairs, offering tributes, and contributing militarily. The

Assembly of Śākyamuni visually enacts this dual identity by integrating Tibetan esoteric elements into a Han Buddhist framework, projecting a localized mode of authority within the imperial order.

These three largest, most elaborately executed murals occupy the most prominent position within Dabaoji Palace and concentrate the richest category of religious iconography, establishing the central hybrid space as both the ritual center and the prominent symbol of political authority. Reflecting the pluralistic religious environment of Naxi society, it concentrates on the Mu family’s sophisticated frontier strategy as a coherent visual program. As the centerpiece, the Assembly of Śākyamuni Buddha is organized within a Han Buddhist visual framework and serves as the focal point of the mural program. The predominance of Han Buddhist and Daoist deities across all three murals articulates the Mu chieftains’ identification with Ming authority and their alignment with the empire’s frontier cultural policies. Meanwhile, the selective incorporation of Tibetan esoteric elements indicates their role as imperial agents in managing Tibetan affairs. Through a deliberate balance of religious iconographies, the Mu chieftains crafted a space that reaffirms their allegiance to the Ming imperial court while asserting their delegated authority over Tibetan regions.

The central motifs of the ceiling’s caisson design (

Figure 11) embody a symbolic convergence of Tibetan and Daoist cosmologies. Specifically, the integration of the Tibetan Buddhist motif of

rnam bcu dbang ldan (the design of Gathering Ten Powerful Elements) and the Daoist

Bagua 八卦 diagram within the caisson’s core visual schema serves as an emblem of Han-Tibetan cosmological synthesis (

Mu 2020). This deliberate juxtaposition visually enacts a syncretic worldview wherein differing religious cosmologies are harmonized within a unified sacred space.

The central space thus exemplifies a multi-religious ritual field anchored by Han Buddhism while tactically integrating Daoist and Tibetan visual elements. This results in a visually unified program that reinforces the Mu chieftains’ identity as both loyal representatives of imperial agents and active mediators at the Ming frontier, projecting subjectivity through articulating a distinctive political-religious discourse that bridges imperial authority, Tibetan religious polities, and Naxi local governance. Its strategic location and artistic sophistication position it as the highest symbolic tier within Dabaoji Palace’s spatial and ideological hierarchy.

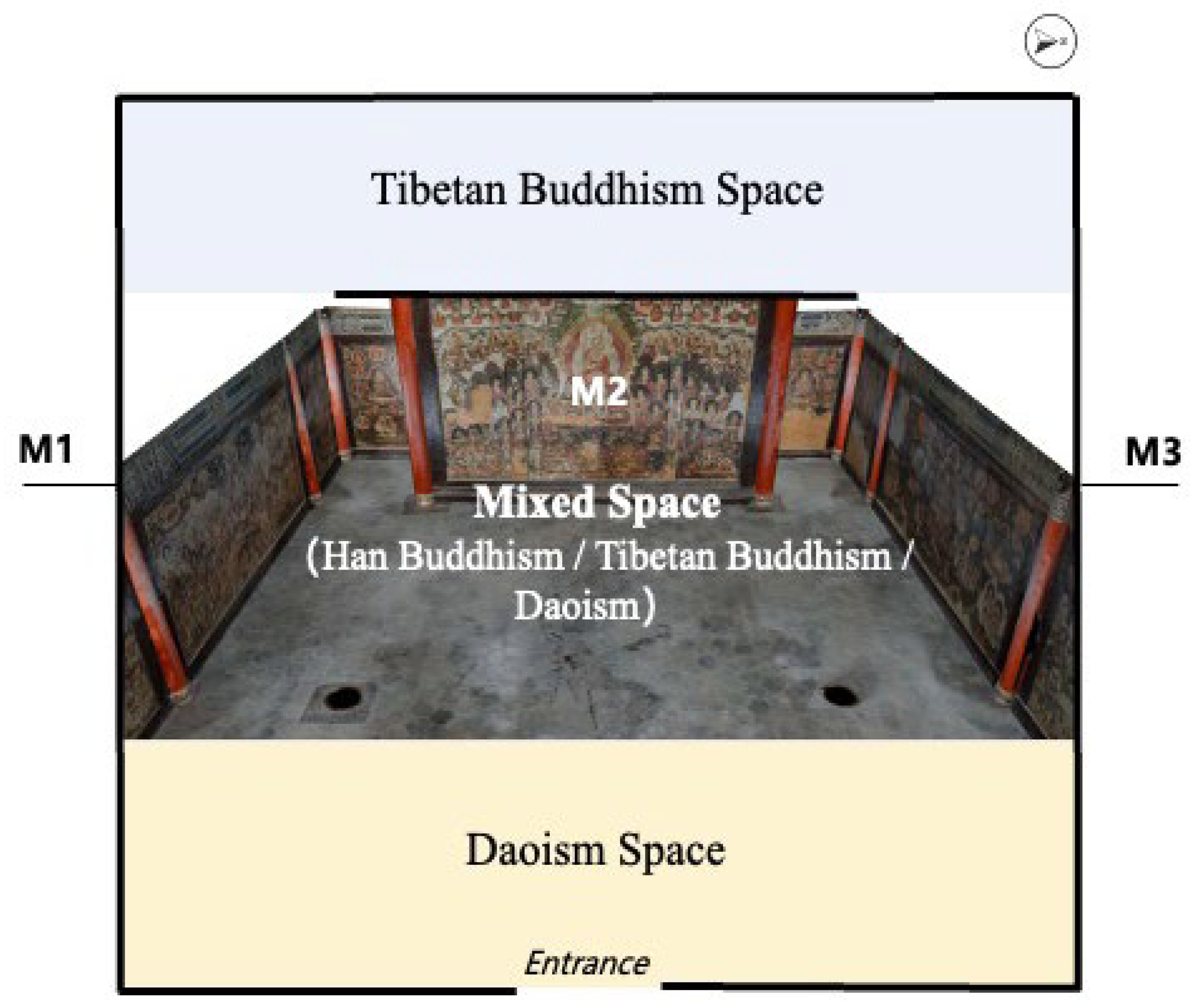

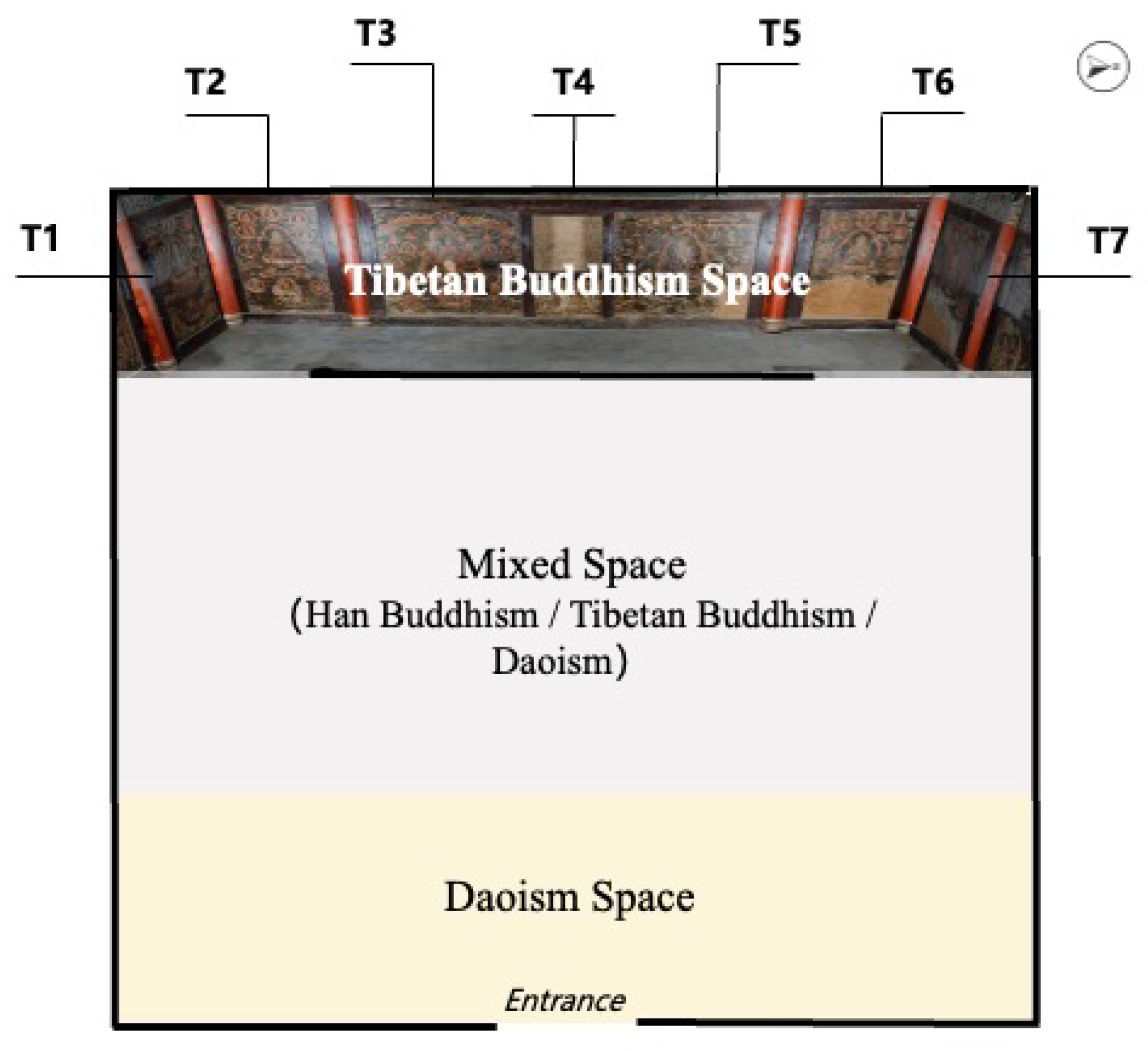

2.3. Back Zone: The Sacred Space of Tibetan Buddhism

Behind the central screen wall lies the innermost sanctum of Dabaoji Palace. Physically shielded from immediate view, this dimly lit and enclosed area forms a secluded space devoted to Tibetan tantric Buddhism. It comprises five surviving panels on the west wall and two panels at the western ends of the south and north walls (

Figure 12). According to

Debreczeny (

2009), the west wall murals, from left to right, include Vajrasattva (T2), the

Mahāmudrā Lineage (T3),

Vajradhara Surrounded by Eighty-Four Mahāsiddhas (T5), and

Vajravidāraṇa (T6), while the central panel (T4) is now lost. The south wall’s westernmost mural (T1) features

Mahākaruṇika Jinasāgara, while its northern counterpart (T7) depicts

VajravārāhĪ as Vajrayoginī (

Debreczeny 2009). The esoteric deities depicted on the walls and their compositional arrangements are in line with the Karma Kagyü school of Tibetan Buddhism, affirming the Mu chieftains’ religious status as the major Kagyü patron and thereby legitimizing their authority over Tibetan regions.

The physical characteristics of this space and the murals’ iconographic content evoke the secrecy and sanctity necessary for tantric rituals, suggesting that the space may have served specific meditative functions for Kagyü masters or members of the Mu lineage. Yet beyond its religious purpose, this realm holds significant political intent through its presentation of a systematic visual lineage of Indian and Tibetan Kagyü masters, authorizing the Karma Kagyü tradition in Lijiang and thereby reinforcing the Mu chieftains’ religious status and political role as imperial agents of Tibetan affairs.

The strategic alliance between the Mu chieftains of Ming-dynasty Lijiang and the Karma Kagyü lineage of Tibetan Buddhism was rooted in geographic proximity and sustained religious-cultural exchange. Since the time of the Second Karmapa, Karma Pakshi (1204–1283), the Black Hat Karmapas had established monasteries and disseminated teachings across Kham. This alliance was solidified in 1516, when the Eighth Karmapa, Mikyö Dorje (1507–1554), was invited to Lijiang by Mu Ding (

Feng 2008). The grand reception for his arrival marked the Mu chieftains’ official adoption of the Karma Kagyü tradition. The relationship culminated in 1623 with the completion of the Lijiang edition of the

Kangyur, the Tibetan Buddhist canon, sponsored by Mu Zeng and supervised by the Sixth Red Hat Karmapa, Chökyi Wangchuk (1584–1635) (

Feng 2008). From the Wanli period onward, the Mu family actively sponsored Kagyü monasteries and invited prominent lamas to teach locally. Among these acts of patronage, the murals of Dabaoji Palace visually assert the Mu chieftains’ alliance with the Karma Kagyü lineage, hence their religious-political legitimacy in Tibetan governance.

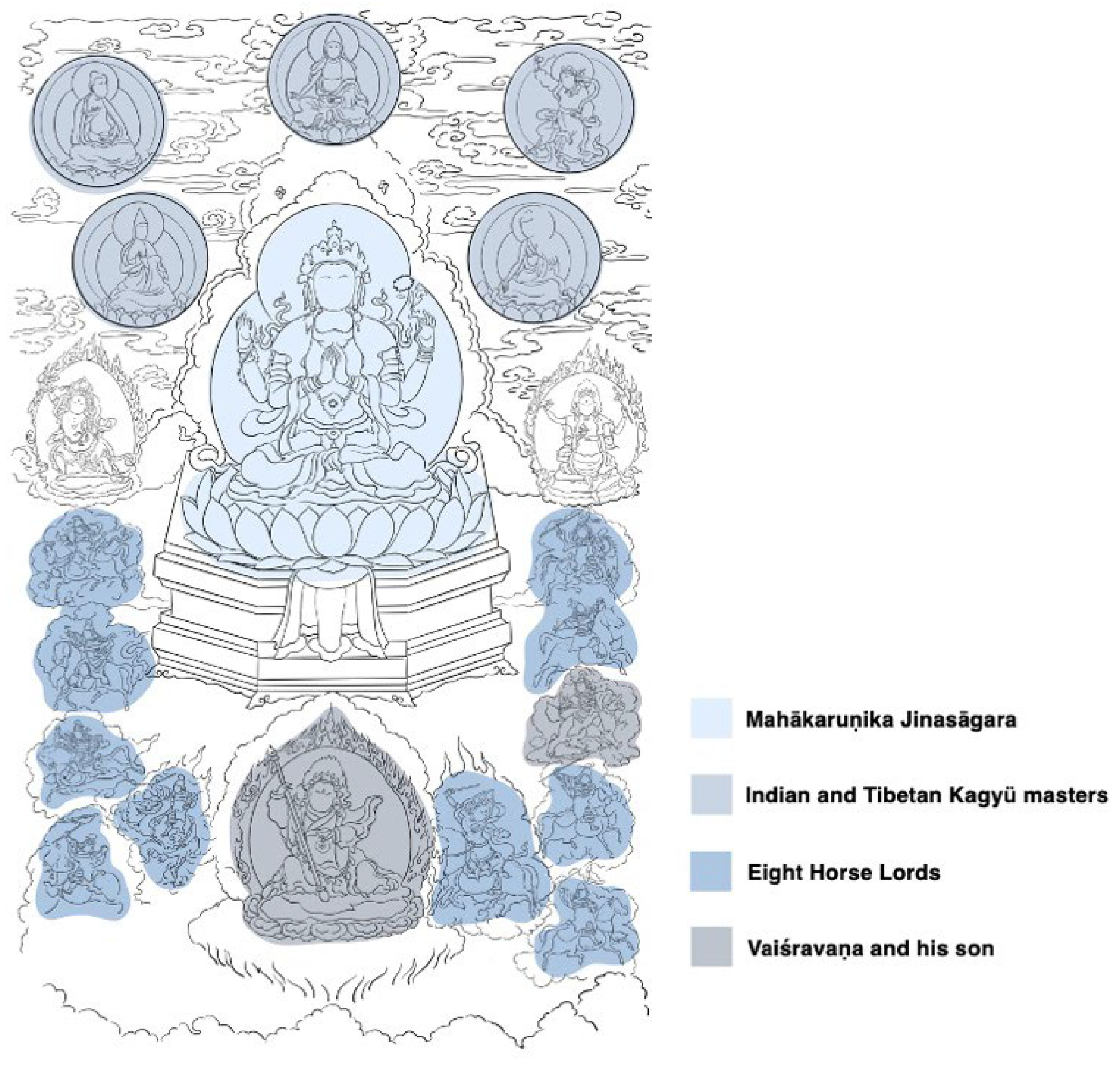

The mural

Mahākaruṇika Jinasāgara (T1,

Figure 13) exemplifies this alliance through a sacred hierarchy centered on Kagyü spiritual lineage. At the center sits Mahākaruṇika Jinasāgara (the Great Compassionate Avalokiteśvāra of the Buddha Ocean), a principal tantric deity embodying compassion, particularly venerated by the Karma Kagyü. Above are three Indian masters: Tipupa (center), Padampa Gyagar (founder of the Zhijepa order, left), and his disciple Machik Labdrön (right). Below them appear Marpa Chökyi Lodrö (founder of the Kagyü school, left) and Rechungpa (disciple of Milarepa, right). Flanking the central deity are two esoteric

Yidams: Hayagrīva (left), identifiable by a horse head emerging from his hair (

Debreczeny 2009), and a four-armed wrathful form of Guhyajñānādākinī (right), the Secret Wisdom Ḍākinī. Below the central figure are a series of worldly protector deities and warriors: directly beneath stands the Brahmin Guardian of Virtue, father of Vaiśravaṇa (guardian king of wealth), flanked by eleven mounted warriors including Vaiśravaṇa, the Eight Horse Lords (his attendants), and local road and livestock guardian gods (

Xiong 2006). As seen in

Figure 14, this vertical arrangement visually legitimizes the Kagyü transmission in Lijiang by aligning Indian masters with Tibetan transmitters. Meanwhile, the inclusion of worldly protectors likely reflects the Mu chieftains’ pragmatic concerns in regional security and economic prosperity, such as securing trade routes, including the local Tea-Horse Road.

The ancient Tea-Horse Road extended from tea-producing regions in southern Yunnan through Dali, Lijiang, and Diqing, reaching central Tibet and even parts of South Asia, traversing high-altitude and mountainous terrain. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the Mu chieftains’ inclusive frontier policies transformed the road into both a thriving trade artery and a conduit for multiethnic cultural exchange (

Li 2017). Their strategy of “governing Tibet through tea exchange (

yi cha yu fan 以茶驭番)” effectively restrained Mongol expansion into Tibetan regions and secured key strongholds along the route, positioning Lijiang as a crucial nexus linking Tibetan and Han Chinese spheres. Moreover, their integration of Tibet-Yunnan commercial trade into the Ming economy strengthened imperial cavalry with Tibetan warhorses and encouraged silver inflows via expanded Yunnan tea exports (

Xu 2020).

The mural’s juxtaposition of Indian masters and Tibetan translators visually affirms Karma Kagyü religious authority within Mu-governed territories, while its combination of esoteric and local protectors reflects the local trade environment. This iconographic program highlights the Mu chieftains’ dual function as imperial frontier agents: safeguarding regional stability and fostering economic development and intercultural exchange along the Tea-Horse Road.

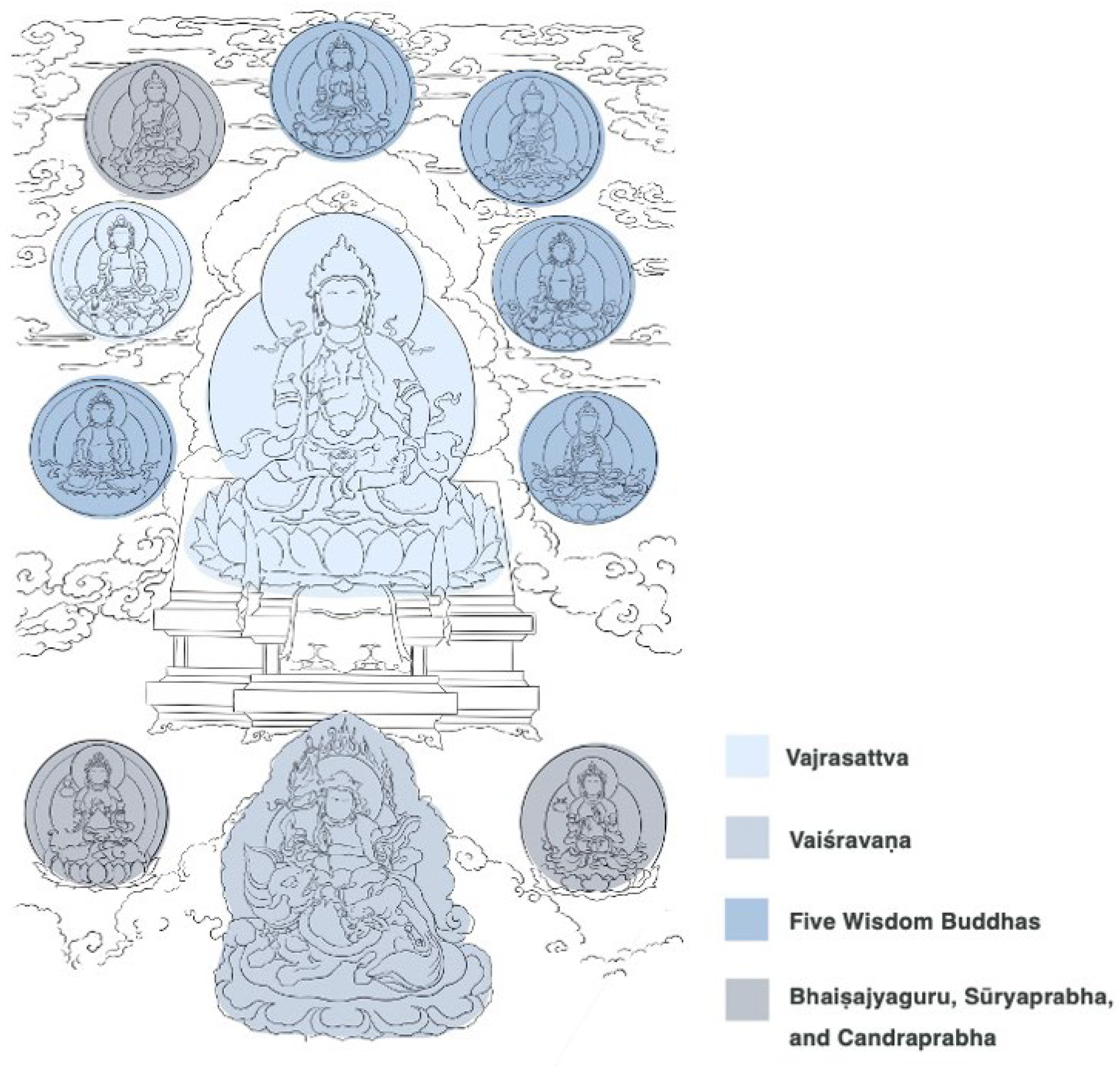

The first mural on the west wall depicts Vajrasattva and the Five Wisdom Buddhas (T2,

Figure 15). At the center, Vajrasattva embodies the primordial source of Tibetan tantric teachings (

Xiong et al. 2013). He is surrounded by Bhaiṣajyaguru (the Medicine Buddha), a smaller emanation of Vajrasattva, and the Five Wisdom Buddhas in the tantric system—Vairocana at the top center, with probable depictions of Akṣobhya (east) and Amitābha (west, inscriptions obscured), Ratnasambhava (south), and Amoghasiddhi (north). Below the central deity stands Vaiśravaṇa (also seen in T1), flanked by Sūryaprabha and Candraprabha, bodhisattvas of sunlight and moonlight (

Xiong et al. 2013). Vaiśravaṇa appears unarmored with his white lion mount holding treasure in its mouth, an image potentially reflecting the Mu chieftains’ aspiration for prosperity and Lijiang’s position as a flourishing trade hub during the Ming era. Notably, the triadic grouping of Bhaiṣajyaguru, Sūryaprabha, and Candraprabha originates in Han Chinese esoteric iconography (as seen in the Bhaiṣajyaguru assembly at Liuli Hall wherein all murals are purely Han-style), yet it is recontextualized here within a Tibetan tantric framework (

Figure 16). This deliberate synthesis embodies the Mu chieftains’ visual strategy of negotiating Han and Tibetan religious-cultural paradigms.

The adjacent mural,

Mahāmudrā Lineage (T3,

Figure 17), establishes the orthodoxy of the Karma Kagyü school through a structured hierarchy of Indian and Tibetan lineage holders, asserting its status as the preeminent Tibetan Buddhist sect in Lijiang. Centered at the base is Mahākāla, the wrathful protector deity of the Kagyü tradition (

Debreczeny 2009), whose fierce form underscores the sanctity and defensive power of the lineage.

Debreczeny et al. (

2012), in his study of the Tenth Karmapa Chöying Dorje’s exile to Lijiang in 1647 (driven by pressure from the Geluk school in Tibet), identifies him as the mural’s central figure and suggests that he may have personally overseen its creation. The mural’s prominent depiction of the Tenth Karmapa reaffirmed the Mu chieftains ’patronage and provision of sanctuary for the Karma Kagyü lineage, reinforcing its religious prestige across Tibetan regions. The Tenth Karmapa is also enthroned upon a Han Chinese-style seat adorned with six dragons, a motif invoking his title “Great Precious Dharma King” (

Da Bao Fawang 大宝法王), which was officially conferred by the Ming court. This iconographic element reflects the Mu chieftains’ integration of Ming imperial symbolism and alignment with Ming political ideology, highlighting their role as intermediaries between central authority and Tibetan religious networks.

The third surviving mural on the west wall (T5,

Figure 18),

Vajradhara and the Eighty-Four Mahāsiddhas, intensifies the focus on Karma Kagyü transmission. Vajradhara, regarded as the primordial source of Mahāmudrā teachings, presides at the center, encircled by tiered rows of eighty-four Indian siddhas, including Nāgārjuna, Nāropa, and Saraha (

Xiong et al. 2013). These figures collectively construct a visual lineage of spiritual attainment revered by Karma Kagyü practitioners, who emphasize meditation (

Debreczeny 2009). This iconographic program visually affirms the sect’s doctrinal orthodoxy and underscores the religious legitimacy of the Mu chieftains’ patronage by linking the esoteric lineage to its Indian origins.

The final mural on the west wall,

Vajravidāraṇa (T6,

Figure 19), features twelve tantric deities. The central figure, likely Vajravidāraṇa, is a major purificatory deity within the tantric tradition (

Xiong et al. 2013). Vajradhara appears again at the top center, affirming the root of the Kagyü lineage. To Vajradhara’s left sits the female deity Uṣṇīṣavijayā, distinguished by three faces and eight arms (

Xiong et al. 2013). Surrounding them are eight wrathful guardian figures, reinforcing the protective functions of the composition. The north wall’s western section continues the esoteric sequence with

Vajravārahī as Vajrayoginī (T7,

Figure 20), a fierce female tantric deity central to advanced meditative practices, affirming the ritual depth of the palace’s inner sanctum.

The murals in the rear section of the hall establish an intentionally enclosed sacred realm centered on the Karma Kagyü lineage and spiritual attainment. This esoteric spatial configuration reinforces the authority of the Karma Kagyü school in its practice and transmission while legitimizing the Mu chieftains’ rule through visual alignment with a prestigious religious tradition. This contrasts significantly with the central hybrid, public-facing space anchored by the Assembly of Śākyamuni Buddha, where both Han and Tibetan visual elements are integrated to project an inclusive ritual environment accessible to diverse audiences, including Ming officials, Tibetan practitioners, and Naxi elites. While the rear sanctum likely served private ritual or meditative purposes, the central space, through its visual inclusivity and prominent location, becomes the primary stage to express the Mu chieftains’ political-religious strategy and showcase their creative agency as frontier governors. Such spatial and visual deviations reveal the Mu chieftains’ sophisticated role as local intermediaries between regional and central powers. Their religious patronage not only bolstered Karma Kagyü institutional presence but also aligned with Ming imperial policies for managing Tibet.

By forming religious and political allegiance with Tibetan Buddhism, the Mu chieftains contributed significantly to stabilizing the Sino-Tibetan frontier, promoting cultural exchange, and integrating local economies into the empire’s trade networks. These efforts demonstrated their role in fostering a pluralistic cultural landscape that balanced Han, Tibetan, and local interests while adhering to the broader strategic objectives of the Ming court. In this way, the Mu chieftains exemplified a mode of frontier governance that reconciled regional autonomy with imperial solidarity.