1. Introduction

Islamic architecture serves as a vital material carrier for the dissemination and development of Islamic civilization, embodying profound religious and cultural significance. Since its introduction to China, Islamic architecture has undergone centuries of adaptation and integration, gradually forming a distinct Sinicized architectural system that harmoniously incorporates traditional Chinese aesthetics, craftsmanship, and regional cultural characteristics. Given China’s vast territory and diverse cultural landscapes, Islamic architecture in different regions demonstrates a wide range of local features while maintaining its core religious functions and theological expressions. As one of the four ancient mosques along China’s southeastern coast, the Phoenix Mosque in Hangzhou enjoys high recognition even among Arab nations. Its architectural and chromatic characteristics make it a crucial case for examining the Sinicization of Islamic architecture.

However, existing research on Chinese Islamic architecture remains limited in its systematic exploration of colour systems. In particular, there is a lack of in-depth analysis of the symbolic, cultural, and aesthetic meanings behind colour use, and a coherent theoretical framework has yet to be established. As a paradigmatic example of Chinese Islamic architecture, the Phoenix Mosque’s colour scheme integrates Islamic cultural symbolism with the stylistic and environmental features of the Jiangnan region, offering significant research value. Nonetheless, studies focusing on the mosque’s colour symbolism, visual characteristics, and its cultural role in expressing and transmitting Islamic identity within the Chinese context remain scarce.

Therefore, this study aims to analyse the distinctive colour features of the Phoenix Mosque to reveal the unique principles and cultural meanings underlying colour application in Chinese Islamic architecture. By examining the use of colour in both the mosque’s structural and decorative elements, the study investigates how religious beliefs, regional cultures, and other deep-seated spiritual dimensions influence architectural colour design, and how colour functions as a visual language to convey faith, cultural traditions, and local identity. Using the Phoenix Mosque as a case study, this research seeks to provide theoretical support for the preservation, inheritance, and innovative development of Chinese Islamic architecture, promote intercultural communication within a pluralistic cultural context, and enhance public understanding and appreciation of this unique architectural heritage.

2. Literature Review

Research on Islamic architecture in China began relatively late but has developed rapidly in recent years. Early studies in China mainly focused on descriptive and historical overviews, emphasising surface features such as architectural appearance, style, and decorative elements. For instance,

Sun (

2002) examined the stylistic features of traditional Islamic architecture in Xinjiang, highlighting its rich external forms, distinctive domes, and cool-toned colour palette. He further traced its developmental trajectory, noting a shift from neglecting traditional elements to incorporating modern technologies (

Sun 2002, pp. 46–47). Similarly, Yao Weixin (

Yao 1995) provided a historical overview of Islamic architectural development, with a focus on the ancient architecture of Damascus, offering broader insights into the evolution of Islamic architectural art (

Yao 1995, pp. 64–66).

Wu (

2004) contributed to the religious studies by introducing the main types and characteristics of Islamic architecture, including mosques, madrasas, palaces, and mausoleums, and analysing the formation and transformation of their artistic styles. His work emphasised the uniqueness of Islamic architecture and its capacity for multicultural integration (

Wu 2004, pp. 73–75). Building on these perspectives,

Q. Li (

2007) conducted an in-depth analysis of Islamic architecture in Xinjiang, exploring its architectural features, ornamentation, and colour schemes. He stressed the importance of local and religious identity as well as environmental harmony in shaping its cultural significance and aesthetic appeal (

Q. Li 2007, pp. 115–16).

Subsequent studies, however, have increasingly focused on the localization of Islamic architecture in China, and how local cultures influence architectural transformation across regions. For instance,

Jin (

2008) conducted a comparative analysis of four mosques in Shanghai, namely Songjiang Mosque (a blend of Chinese and Arab styles), Fuyou Road Mosque (fully Chinese), Xiaotaoyuan Mosque (featuring innovative West Asian influences), and West Shanghai Mosque (showcasing a modern Arabic style). His study revealed how these architectural forms collectively reflect the processes of localization, modernization, and cultural hybridity in Chinese Islamic architecture from the Yuan Dynasty to the present (

Jin 2008, pp. 45–48). Expanding on the theme of cultural fusion,

Y. Li (

2015) explored how traditional Arab architectural elements, such as arches, were gradually replaced by Chinese brick carving techniques. She also pointed out the incorporation of indigenous Chinese motifs, including dragons and phoenixes, into Islamic architecture, and emphasised the creative use of Chinese calligraphy and couplets. Auspicious symbols such as “Fu-Lu-Shou-Xi” were likewise integrated into religious buildings. These features collectively illustrate a dynamic interplay between Islamic culture and Chinese folk art (

Y. Li 2015, p. 43). Similarly,

Zhang and Ma (

2015) examined the Niujie Mosque, which follows the layout of a traditional Chinese palace while adhering strictly to Islamic ritual law. They emphasised spatial strategies such as the “lion turning back” layout and the prominent use of vermilion decoration as expressions of unique cultural integration in Chinese Islamic architecture (

Zhang and Ma 2015, pp. 84–85). More recently,

Niu (

2023) argued that Chinese Islamic architecture elevates localization into a comprehensive cultural practice by employing rhetorical strategies in landscape design and drawing upon the institutional legacy of Ming dynasty ritual reforms. According to

Niu (

2023), this approach resonates with the “Islam–Confucianism synthesis” model, reflecting a broader civilizational dialogue that unites nature, society, and human values (

Niu 2023, pp. 131–39).

Apart from Chinese scholars’ research results, studies from other countries in Islamic architecture boasts a longer history and a broader, more diversified scope Early studies on Islamic architecture primarily concentrated on architectural forms and structural systems. Over time, however, the scope expanded to include cultural, historical, and social dimensions. Regarding form and structure, scholars have examined the morphology, spatial organisation, and construction technologies across different regions. For example,

Salim A. Elwazani (

1995) analysed how the sanctity of the Qur’an is visually embodied in mosque architecture through calligraphy and decorative motifs. His work highlights the transmedial transformation of “sacredness” from scripture to architectural space (

Elwazani 1995, pp. 478–95). Similarly,

Kubilay Kaptan (

2013) traced the technological development and cultural symbolism of Islamic domes from the Umayyad to the Ottoman periods. By examining iconic examples such as the Dome of the Rock and the Great Mosque of Córdoba, he critiqued modern architectural practices that often detach historical elements from their original contexts and meanings (

Kaptan 2013, pp. 5–12). In addition, in the realm of decorative arts, particular attention has been given to geometric patterns and Arabic calligraphy.

Hashemi (

2023), for instance, explained how the fusion of Islamic calligraphy and sacred geometry functions as a material expression of Ihsan (beauty). This integration reveals a symbiotic relationship between religious philosophy and aesthetic logic within Islamic art and architecture (

Hashemi 2023, pp. 36–56).

Cultural studies in the colour schemes of Islamic architecture remains limited, with an especially notable lack of systematic studies focusing on Chinese Islamic architecture. Existing literature often falls short in analysing the religious symbolism, regional cultural influences, and aesthetic concepts underpinning the use of colour, and a comprehensive theoretical framework has yet to be established. As a representative example of Chinese Islamic architecture, the Phoenix Mosque in Hangzhou features a unique colour system that blends Islamic cultural elements with the stylistic and environmental features of the Jiangnan region. Despite its high research value, there has been little in-depth exploration of the mosque’s colour symbolism, visual characteristics, or its cultural roles in the transmission, expression, and dissemination of Islamic identity in the Chinese context.

3. Research Methods

To ensure the systematicity and scientific rigour of this study, a multi-method research approach was adopted, as outlined below. First, a literature-based analytical method was employed to systematically review relevant studies on Islamic architecture, traditional Chinese architecture, and colour theory both in China and abroad. This provided the theoretical foundation and academic framework for the study, clarifying its scholarly positioning and points of innovation through engagement with existing research. Second, field photography, direct observation, and documentation were used to collect first-hand visual and empirical data, focusing on the building materials, current colour conditions, light-and-shadow effects, and the relationship between the mosque and its surrounding environment. Third, a comparative analysis was conducted to examine the colour applications of the Phoenix Mosque alongside representative inland mosques such as the Huajuexiang Mosque in Xi’an and coastal mosques such as the Qingjing Mosque in Quanzhou and the Huaisheng Mosque in Guangzhou. This comparison highlights both the uniqueness and universality of the Phoenix Mosque’s chromatic expression within different regional and cultural contexts. Finally, iconographic and semiotic analysis was integrated, drawing on theories from religious studies and art history to interpret the colours, motifs, and decorative patterns found in the mosque’s architecture. This approach elucidates the underlying religious symbolism and cultural meanings, as well as the generative logic of its visual language.

4. Cultural Foundations of Colour in Islamic Architecture

Islamic architecture, as a visible carrier of Islamic culture, has accompanied the historical trajectory of the religion’s dissemination. It integrates diverse regional traditions, manifesting distinctive artistic charm and profound religious connotations. The origins of Islamic architecture can be traced back to the 7th century on the Arabian Peninsula. During that period, structures were characterised by simplicity and practicality, heavily influenced by architectural traditions from the Arabian Peninsula, as well as Roman, Byzantine, and Persian styles. These buildings commonly employed materials such as mudbrick, stone, and wood. As the Arab Empire expanded, Islamic architecture closely related to various local cultures, climates, and building traditions. Therefore, it gradually developed into a rich and diverse architectural system.

The mosque is the quintessential form of Islamic architecture, serving as a sacred space for worship, religious education, and communal gatherings. Typically centred around an open courtyard, mosque complexes include key elements such as the prayer hall and minaret. The prayer hall is oriented toward the Kaaba in Mecca, ensuring that worshippers face the qibla during prayer. Minarets, initially intended for the call to prayer, later evolved into highly symbolic architectural elements, often displaying elaborate forms and varying in height. Beyond mosques, Islamic architecture also encompasses madrasas, public baths, Sufi lodges, fountains, and commercial buildings. Collectively, these structures form a comprehensive architectural system that fulfils religious, social, and cultural functions, and testifies to the ongoing interactions and syntheses among different civilizations.

The use of colour in Islamic architecture is not merely decorative but deeply rooted in the religious beliefs and theological doctrines of Islam. It conveys complex cultural meanings and functions as a medium through which spiritual values and regional identities are articulated. From a religious perspective, colour holds explicit symbolic significance. Green, for instance, is one of the most venerated colours in Islamic architecture and is often regarded as a distinguishing feature of Islamic religious structures (

Xu and An 2014, p. 61). Closely associated with the Quranic image of Paradise, green symbolises sanctity, peace, and eternity. As a colour commonly found in nature, it also signifies life and renewal. The green dome of Al-Masjid an-Nabawi in Saudi Arabia, for example, not only serves as a powerful visual marker that evokes the promise of Paradise, but also resonates with surrounding natural vegetation, reflecting Islam’s emphasis on harmony between humanity and nature. Blue, another prominent colour, represents spirituality and Paradise, as well as the sky and sea. The Blue Mosque in Turkey, adorned with thousands of azure tiles, creates a contemplative and immersive atmosphere that guides worshippers toward spiritual reflection and connection with the divine. White is associated with purity and humility; the Islamic Centre in Ljubljana, for example, utilises white concrete and glass to construct a serene architectural environment in which light filters through, fostering introspection and spiritual concentration. Gold, symbolising divine glory and nobility, is exemplified by the golden dome of Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, constructed from anodized aluminium. This Mosque signifies both the perfection of faith and the reverence it commands. These colours, especially the life-affirming hues of green and blue, reflect the faithful’s longing for a blissful afterlife, and contribute to the dazzling visual impact of mosques, fulfilling both symbolic and aesthetic aspirations (

Zhang and Yu 2009, pp. 54–58).

Colour in Islamic architecture also reflects local cultures and ethnic aesthetics. In the Middle East, due to the arid climate and the multicultural environment, buildings often feature bright hues such as blue, green, and gold. These vibrant colours stand in stark contrast to desert landscapes and integrate Persian delicacy with Arab expressiveness. The dazzling tilework of the Isfahan Mosque, for instance, epitomises this dynamic regional spirit. In North Africa, under the influence of Mediterranean and Berber traditions, a preference for the natural textures of stone and earthy, subdued tones prevails. Ornamentation tends to rely on geometric simplicity, as seen in the coastal grandeur of the Hassan II Mosque in Morocco, which embodies both structural power and the beauty of nature.

In China, Islamic architecture blends with indigenous aesthetics. Traditional Chinese colours, red, yellow, and green, are incorporated into mosque design. Green often serves as the primary hue, supplemented by red and yellow, preserving religious symbolism while conforming to the solemn and elegant aesthetic sensibilities of Chinese architecture. Regional variations are particularly pronounced. In the Jiangnan region, influenced by its water-town culture, mosques often feature white walls and black tiles with green decorative elements, producing a refined and serene visual effect. In contrast, northwestern regions, shaped by arid landscapes, favour warm tones such as ochre and red that harmonise with desert terrain and convey a rugged, enduring regional character.

Ultimately, the use of colour in Islamic architecture represents a convergence of faith and culture. It builds spiritual spaces through religious symbolism and reveals regional diversity through local chromatic expressions. Between solemnity and vitality, colour functions as a visual epic, an unspoken dialogue between Islamic civilization and diverse cultural landscapes, narrating the depth of religious belief and the richness of geographic identity.

5. Analysis of Architectural Characteristics and Colour of the Phoenix Mosque in Hangzhou

5.1. Historical Evolution and Spatial Layout of the Architectural Structure

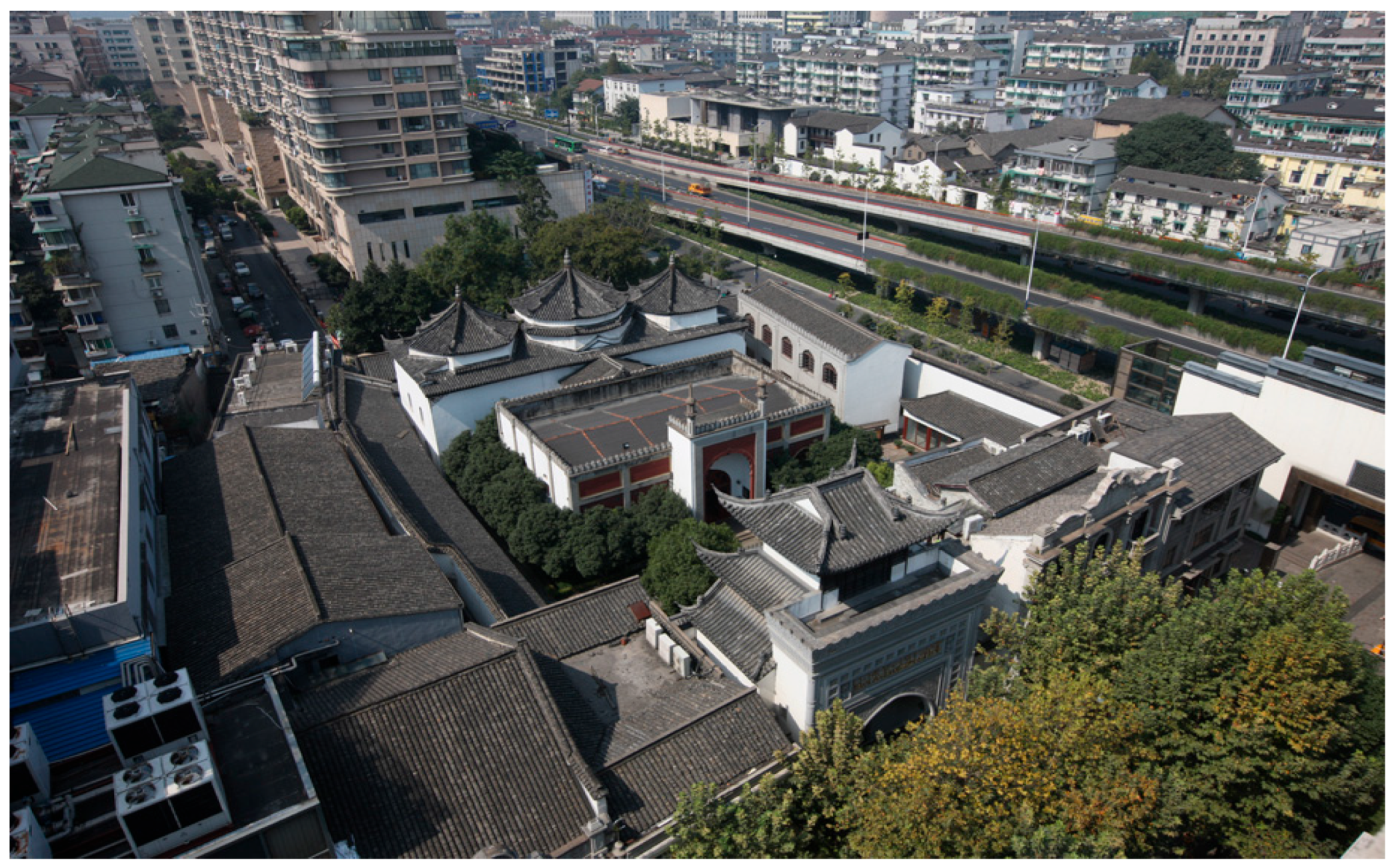

As a distinguished representative of Islamic architecture in China, the Phoenix Mosque in Hangzhou embodies a profound historical legacy and a unique architectural style that reflects the wisdom of intercultural integration, as

Figure 1 shows. Its origins date back to the Tang dynasty, a period marked by the flourishing of the Silk Road, during which the mosque emerged as a significant testament to the early transmission of Islam into Hangzhou. Following its destruction during the wars of the Song dynasty, the mosque was reconstructed in the Yuan dynasty with the financial support of Alauddin, a Muslim from Western Asia. This reconstruction marked the first integration of Arab architectural features with traditional Chinese design, establishing the foundation for the mosque’s hybrid architectural identity (

Hagras 2025, pp. 82–107). During the Ming dynasty, the Phoenix Mosque underwent substantial expansion in response to the growing prominence of Islam. This phase of development saw the deeper incorporate on of local architectural aesthetics, resulting in the formation of a cohesive and comprehensive mosque complex. The Qing dynasty witnessed another major reconstruction, during which the mosque’s scale and influence expanded significantly, elevating it to one of the most prominent Islamic religious centres in the country. It evolved into a vital hub for religious worship, cultural exchange, and community life among Muslims in the region. Although parts of the structure were demolished during the Republican period due to urban development, religious activities persisted. Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Phoenix Mosque has received considerable governmental support and has undergone systematic restoration. Today, it stands as one of the four major ancient Islamic mosques along China’s southeastern coast. It not only continues to serve as a central place of worship for Hangzhou’s Muslim community but also functions as a symbol of China’s longstanding tradition of cultural inclusivity and openness to global influences.

In the localization of Islamic architecture in China, institutional frameworks and cultural cultivation have consistently served as dual driving forces and foundational axes of development. The Phoenix Mosque in Hangzhou is no exception. Its architectural design offers a compelling interpretation of the symbiosis between traditional Chinese structural forms and the spiritual essence of Islam. The overall layout of the mosque adheres strictly to Islamic religious principles. Oriented west to east, with a pronounced axial alignment, all major structures are positioned along this axis, facing Mecca, thus forming a solemn and reverent spatial sequence appropriate for religious practice. Upon entering through the main gate, visitors pass through the front hall and proceed along the central axis to reach the main prayer hall, establishing a clear and orderly spatial hierarchy.

The main hall, considered the architectural centrepiece of the complex, showcases exceptional ingenuity. Its primary structure adopts the traditional Chinese wudian (hipped) roof, symbolising dignity and authority. Innovatively, three pagoda-style domes are superimposed atop the roof, an octagonal double-eaved dome at the centre flanked by hexagonal single-eaved domes on either side. The soaring eaves are adorned with black-ink paintings that blend Arab arabesque scrollwork with Chinese artistic techniques. This design simultaneously evokes the imagery of Islamic domes while reimagining the aesthetics of traditional Chinese roof architecture. Internally, a series of arched doorways connect the various chambers. As shown in

Figure 2, the interior of the hall is spatially connected through a series of arched doorways, with a bluestone Sumeru pedestal positioned at the rear, further enhancing the sacred atmosphere. Particularly noteworthy are the well-preserved relics in the central bay, including the Qur’an Reading Platform from the Song dynasty and a red-lacquered recessed scripture panel from the Jingtai era (Ming dynasty). These elements, featuring intricate craftsmanship, stand as tangible evidence of the deep integration between Islamic ritual practice and Chinese artisanal traditions.

This spatial composition not only fulfils the functional requirements of Islamic worship but also articulates a powerful visual language through its architectural elements (

Yang 1982, pp. 30–31). The use of solid brick-and-stone construction conveys a sense of simplicity and permanence; the interplay of light and shadow through arched windows and doorways introduces a dynamic visual depth; and the rhythmic layering of roof forms creates a striking sense of spatial dimensionality. Together, the public character of the front hall, the sanctity of the main prayer hall, and the axial layout’s sense of hierarchical order coalesce into a distinctive architectural system often described as “Chinese on the outside, Islamic at the core” (wai Zhong nei Yi). In this way, the Phoenix Mosque transcends its role as a mere site of religious practice. It stands as a material testament to the integration of Islamic spiritual principles with Chinese architectural ingenuity, leaving a lasting legacy of civilizational dialogue and mutual enrichment for future generations.

5.2. External Colour System of the Phoenix Mosque

The external colour system of the Phoenix Mosque fully embodies the aesthetic sensibilities of Jiangnan architecture. Characterised by whitewashed walls and dark grey tiles, Jiangnan buildings typically pursue a visual effect of simplicity and subtlety. The Phoenix Mosque integrates this aesthetic principle into several of its structures. For instance, the outer walls of the Prayer Hall and the Ceremony Hall are finished in pure, unadorned white, which not only aligns with the visual impression of Jiangnan architecture but also enhances a sense of serenity and peace. Under sunlight, the white walls appear bright and pleasant, harmonising with the surrounding greenery and blue sky to vividly capture the gentle beauty of the Jiangnan landscape, as shown in

Figure 3.

The hipped roof of the Prayer Hall and the overhanging eaves of the Moon-Viewing Pavilion are covered with greyish-blue tiles. The rustic texture of the tiles complements the white walls, creating a balanced and elegant contrast that conveys both stability and purity. This design not only reflects the Jiangnan architectural tradition’s distinctive understanding of chromatic harmony but also endows the ancient mosque with a profound sense of historical gravity. The Moon-Viewing Pavilion, as a symbolic structure of the Phoenix Mosque, features a dome resembling a circular crown. Its design skillfully integrates the Islamic dome with the upturned eaves of traditional Chinese architecture. The pavilion adopts a palette of alternating white and blue tones, producing a refined and tranquil yet subtly mysterious visual effect. The eaves, covered with grey-blue tiles, contrast visually with the white walls and the blue dome, highlighting the depth and elegance of traditional Chinese architectural aesthetics. Golden decorative elements are meticulously applied to the window frames and dome motifs, symbolising ideals of sanctity, nobility, and perfection, and imbuing the pavilion with a solemn and magnificent aura that enriches its religious symbolism. The contrast between the grey cylindrical tiles of the main hall roof and the blue glazed tiles of its pyramidal apex further exemplifies an aesthetic of dignity and refined elegance.

5.3. Interior Colour Scheme of the Phoenix Mosque

The decorative colour scheme of Fenghuang Mosque is equally rich and vibrant, contributing significantly to its unique artistic appeal. The use of colour in decorative elements—such as murals, carvings, and window and door frames—is both refined and skillful. These artistic applications not only demonstrate a high level of craftsmanship but also embody profound cultural meanings, playing a crucial role in enhancing the overall aesthetic expression of the architecture.

Murals constitute an essential component of the mosque’s decorative art. Although most of the concentric circle murals that once adorned the dome of the main prayer hall have deteriorated, the remaining traces still offer glimpses of their former splendour. These murals primarily feature intricate floral and arabesque motifs, occasionally interspersed with depictions of birds, landscapes, and natural elements. The vivid and luminous colour palette conveys a strong sense of vitality and beauty inspired by nature. Floral arabesques, commonly found in Islamic ornamentation, symbolise the continuity and eternity of life, reflecting a deep reverence for nature and existence. Notably, the murals also incorporate elements of traditional Chinese culture—such as bat motifs symbolising good fortune and ruyi patterns representing auspiciousness—greatly enriching their cultural significance and serving as a vivid testament to the synthesis of Islamic and Chinese cultural traditions. Dominated by profound blues, lively greens, and bright yellows, the colour scheme is meticulously coordinated to create an atmosphere that is both serene and vibrant. This carefully constructed visual space imbues the mosque with strong religious symbolism and aesthetic depth, offering a harmonious fusion of spiritual meaning and artistic beauty.

Carvings represent another major highlight of Fenghuang Mosque’s decorative art, where exquisite craftsmanship and the harmonious application of colour bring the works vividly to life. As shown in

Figure 4, the minbar (pulpit) inside the main prayer hall is shaped in the form of a Sumeru pedestal and is made of bluestone. Though simple in form, its stone carvings are refined: the waisted section is intricately adorned with vine and arabesque motifs, and the columns are carved with meticulous detail. These carvings retain the natural colour of the bluestone, conveying an understated elegance that complements the architectural surroundings, embodying Islamic architecture’s pursuit of simplicity and solemnity. In contrast, the wooden red-lacquered Qur’an case atop the minbar is brightly coloured and visually striking. The case is inscribed with Arabic verses from the Qur’an and decorative motifs; the interplay of the red lacquer background and gold-carved lines highlights both the central role of the Qur’an in religious rituals and the fusion of religious culture and decorative artistry. In Chinese culture, red symbolises auspiciousness, celebration, and prosperity; within this religious space, it also imparts a sense of sacred solemnity. Gold, associated with sanctity, nobility, and glory, resonates deeply with Islamic ideals, making the Qur’an case both a visual and spiritual focal point.

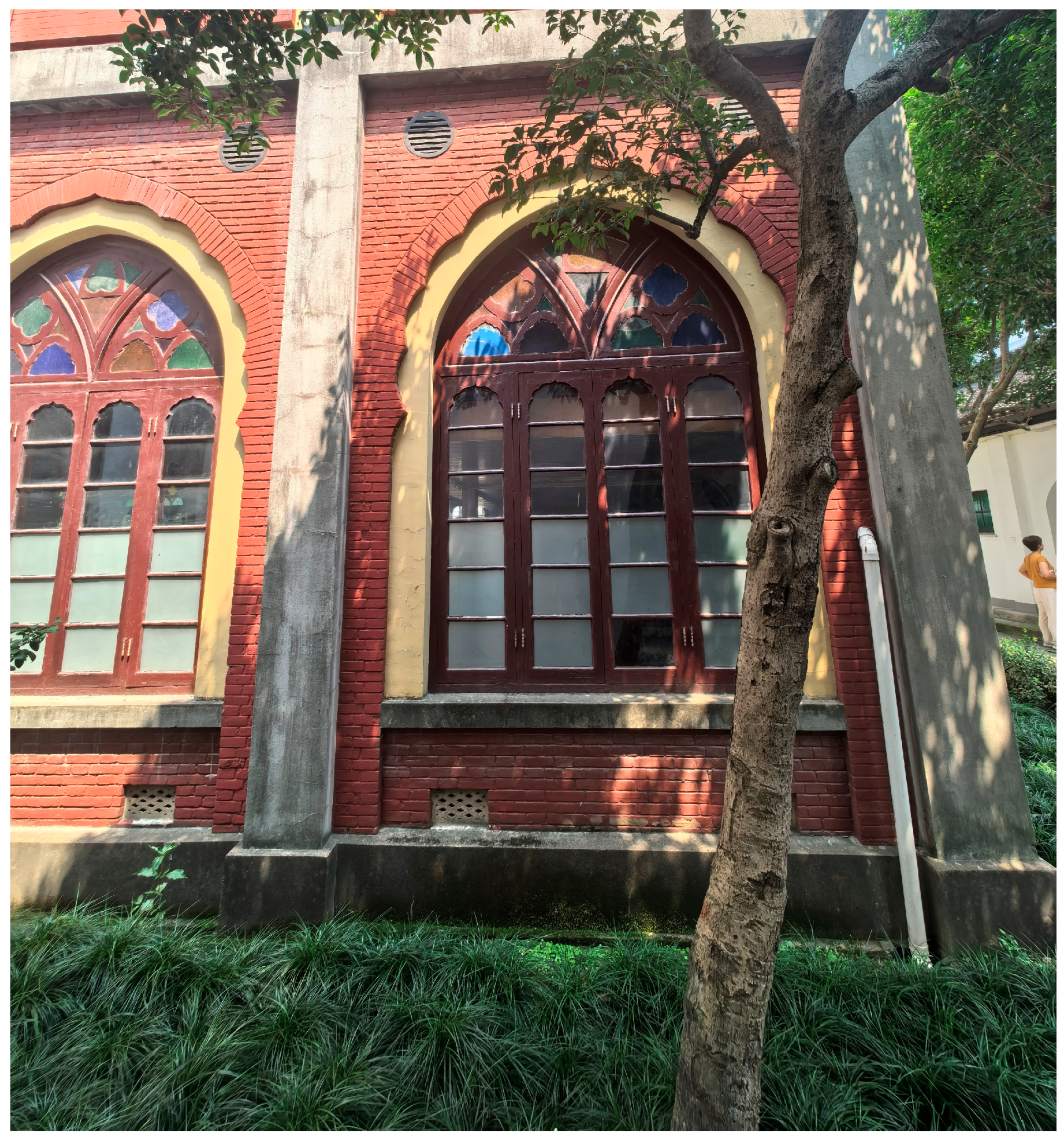

Doors and windows in Fenghuang Mosque serve both functional and decorative purposes. Their use of colour is remarkably thoughtful—harmonising with the overall architectural style while also expressing individual aesthetic character, As shown in

Figure 5. The grand entrance to the prayer hall features an arched portal of red brick, within which a vermilion wooden door is set. Above the door is a petal-shaped window inlaid with colourful glazed glass that sparkles in the sunlight. The combination of red brick walls and vermilion-painted wood vividly reflects the traditional Chinese architectural preference for red—a colour symbolising dignity and celebration. As shown in

Figure 5, from a functional perspective, traditional vermilion lacquer is also one of the most effective and commonly used protective coatings in Chinese timber architecture, providing essential resistance against moisture, decay, and insect damage. Therefore, the use of vermilion here represents a sophisticated integration of cultural symbolism and material durability. As shown in

Figure 6, This symbolism aligns seamlessly with Islamic architectural values concerning colour. The petal-shaped window’s coloured glass offers a rich palette and distinctive translucency. As sunlight passes through, it creates a dreamlike interplay of brilliant hues, appealing to Islamic aesthetic preferences while also showcasing the craftsmanship of traditional Chinese glasswork. These stained-glass elements shift in colour with changes in light, interacting beautifully with the surrounding architecture and becoming a striking visual feature of the mosque’s exterior.

The decorative colour scheme of Fenghuang Mosque stands as a successful synthesis of Islamic religious culture and the regional aesthetics of Jiangnan. It not only enriches the mosque’s visual presentation but also powerfully conveys layered cultural meanings. The colour designs significantly elevate the architectural artistry, weaving a splendid symphony of harmonious coexistence between Chinese and Islamic civilizations. As such, it forms an indispensable part of the cultural and architectural heritage of this historic mosque.

6. Origins of Colour Characteristics of Fenghuang Mosque

6.1. Integration of Religious Cultures

After the introduction of Islam into China, it underwent a long and profound process of integration with traditional Chinese culture. This intercultural fusion is particularly reflected in the use of architectural colour at Fenghuang Mosque in Hangzhou (

X. Li 2011, pp. 68–75). From a religious and cultural perspective, both Islam and Chinese tradition possess distinct systems of colour symbolism. Within the spatial and spiritual context of Fenghuang Mosque, these symbolic systems intersect and harmonise, collectively shaping a unique and culturally layered chromatic identity.

Islamic religious culture has played a direct and lasting role in shaping the mosque’s colour aesthetics. According to Islamic teachings and traditions, colours such as green, blue, and white carry sacred meanings. Green symbolises sanctity, peace, and paradise; this is echoed in the presence of potted greenery within the main prayer hall and in green accents carved into decorative motifs, conveying a spiritual aspiration for eternal blessing. Blue, associated with spirituality and introspection, once dominated the dome murals of the prayer hall. Though much of the paint has faded, traces of blue suggest an intentional effort to evoke the celestial realm and guide worshippers into contemplation. White, symbolising purity and humility, is used in portions of the mosque’s walls to create a calm, dust-free visual field, conducive to meditative stillness. Collectively, these colour choices construct a solemn and sacred visual atmosphere, with Islamic symbolism forming the foundational tone of Fenghuang Mosque’s colour language.

Importantly, this colour scheme embodies a dual cultural logic. It enables the mosque to transcend the boundaries of a single religious architectural tradition, becoming instead a vivid example of aesthetic dialogue between Chinese and Islamic civilizations. At the same time, traditional Chinese colour values lend the structure a distinctly localised character. In Chinese culture, red is a traditional colour of festivity, symbolising auspiciousness, joy, and prosperity. This cultural preference is clearly reflected in the red brick archways and vermilion-painted wooden doors of the mosque’s main entrance, which enhance the space’s dignity and ceremonial function. Gold, commonly associated with nobility and splendour, is intricately applied to carved Qur’an cases, door and window frames, and ornamental patterns throughout the mosque. These gold accents elevate the architectural richness while emphasising the sacredness of the religious space. Furthermore, Chinese auspicious motifs—such as bat patterns symbolising blessings, and ruyi motifs connoting good fortune—are embedded in the murals, infusing the architecture with multilayered cultural significance and expressing the faithful’s prayers for a prosperous and harmonious life.

Ultimately, it is this deep-level integration of religious cultures that gives rise to the mosque’s distinctive approach to colour. The cool palette of blue, white, and green preserves the spiritual solemnity central to Islamic architectural space, while the vibrant red and gold highlights resonate with Jiangnan folk aesthetics. This interplay generates a space that is at once contemplative and celebratory—solemn in its sacred function, yet richly human in its decorative expression. The mosque’s unique chromatic composition, symbolic motifs, and spatial narrative collectively reflect the creative potential of cultural exchange. As such, Fenghuang Mosque stands as a powerful visual exemplar of the sinicization of Islamic architecture, and a testament to the harmonious coexistence of two enduring civilizations.

6.2. Influence of Local Culture

The unique and profound regional culture of Hangzhou has provided fertile ground for the development of Fenghuang Mosque’s architectural colour aesthetics. The elegant simplicity of Jiangnan architectural style, the gentle beauty of the natural environment, and the richness of local folk culture have all left a profound imprint on the mosque’s use of colour, endowing it with the ethereal charm distinctive of the Jiangnan water towns.

The Jiangnan architectural tradition has had a significant influence on the colour choices of Fenghuang Mosque. Characterised by whitewashed walls and dark grey tiles, Jiangnan buildings typically strive for a visual effect of simplicity and subtle elegance. Fenghuang Mosque incorporates this aesthetic in several of its structures. For example, the external walls of the prayer hall and ceremonial hall adopt a pure and unadorned white, aligning with the visual sensibilities of Jiangnan architecture while also enhancing the sense of serenity and peace. Under sunlight, these white walls appear bright and pleasing, harmonising with the surrounding greenery and blue sky and vividly capturing the soft beauty of the Jiangnan landscape. The prayer hall’s hip roof and the overhanging eaves of the Wangyue Pavilion are covered with bluish-grey tiles. The rustic texture of the tiles complements the white walls in a balanced and elegant manner, creating a contrast between stability and purity. This not only reflects Jiangnan architecture’s distinctive understanding of colour harmony but also adds a layer of historical gravitas to the ancient temple.

At the level of decorative detail, Jiangnan architecture’s emphasis on refined craftsmanship also profoundly shapes Fenghuang Mosque’s aesthetic. Intricate carvings and murals throughout the temple showcase a rich palette. For instance, the Sumeru-shaped Qur’an reading platforms on the rear walls of the main and side bays of the prayer hall are made of bluestone and primarily retain the natural colour of the material. However, the finely detailed carvings exemplify the exquisite decorative techniques of Jiangnan architecture. The red-lacquered wooden Qur’an holders placed atop the platforms use contrasts between red lacquer and golden script lines to demonstrate a pursuit of chromatic layering and visual depth. Although the concentric circular murals on the dome have largely faded, their remaining traces still reveal the vividness of the original colours, resonating with the Jiangnan tradition of decorative polychromy and lending the mosque a distinct artistic appeal.

Hangzhou, renowned as a “paradise on earth,” provides a distinctive geographical and cultural context for the Phoenix Mosque. The use of green within the mosque not only reflects the sacred symbolism of Islam but also harmonises with the natural scenery of West Lake. Employed as an accent colour in selective architectural details, it serves as a visual and spiritual bridge between religious symbolism and the surrounding landscape, creating a unique atmosphere in which spirituality and nature coexist in harmony. Similarly, the colour blue—symbolising spirituality and the celestial garden in Islamic tradition—mirrors the azure skies and clear waters of Hangzhou. The blue dome murals inside the prayer hall and the greyish-blue tiles atop the Moon-Viewing Pavilion appear to incorporate the local sky and water directly into the sacred architecture, guiding worshippers into a meditative state of tranquillity and thereby deepening their spiritual experience.

The unique chromatic aesthetics of the Phoenix Mosque did not arise by chance; rather, they represent a synthesis shaped by Hangzhou’s regional culture, socioeconomic conditions, and historical ecology. From architectural style to natural landscape, the poetic charm of Jiangnan has provided the tonal foundation for the mosque’s colour aesthetics, allowing it to embody the spiritual essence of Islam while being deeply embedded in local visual traditions. This profound integration of colours was driven by multiple interrelated factors. The refined craftsmanship and open environment for cultural exchange in Hangzhou provided a solid technical foundation. Since the Southern Song dynasty, Hangzhou has been home to some of China’s most skilled artisans—a tradition evident in the bamboo-joint-shaped columns of the Phoenix Mosque’s prayer hall (whose decorative style resembles that of the Liuhe Pagoda) and in the finely crafted Ming-dynasty wooden Qur’an cases. These features exemplify the artisans’ mastery in assimilating local traditions into their work. The economic strength and adaptive cultural strategies of the Muslim community offered internal momentum for such integration. During the Yuan dynasty, Hangzhou’s Muslim population was economically prosperous and capable of employing the best craftsmen and using high-quality materials such as bluestone. Their adaptive strategy of “external conformity and internal preservation” was also reflected in the mosque’s colour scheme: while maintaining core Islamic symbolism, they adopted the understated tones favoured by Jiangnan scholars and added auspicious hues such as vermilion and gold, achieving a harmonious coexistence of religion and local culture. Finally, a relatively tolerant cultural policy created favourable external conditions for this synthesis. Compared with the stricter architectural regulations in Beijing, the Jiangnan region offered more flexibility in building forms, and the Yuan authorities maintained a lenient attitude toward religious practices. This openness allowed space for creative integration between Islamic culture and local aesthetics. Under the combined influence of these factors, the Phoenix Mosque in Hangzhou emerged as a paradigmatic example of successful localization in Chinese Islamic architecture—an architectural achievement of profound cultural and historical significance that embodies the fusion of regional and religious traditions.

7. Comparative Analysis of Colour Usage in Fenghuang Mosque and Other Chinese Islamic Architecture

7.1. Comparison with Representative Inland Islamic Architecture

As outstanding representatives of inland Islamic architecture in China, the Huajue Lane Mosque in Xi’an, the Niujie Mosque in Beijing, and the Phoenix Mosque in Hangzhou share certain commonalities in their use of colour while each exhibits distinctive aesthetic characteristics. Several fundamental similarities can be observed among the three. Green, as the sacred colour of Islam, holds a revered position in all three mosques, frequently appearing in plaques, decorative motifs, and other key architectural elements. Blue symbolises spirituality, while white signifies purity and holiness—together establishing a solemn and dignified visual tone throughout the mosque complexes. Moreover, all three structures demonstrate a sophisticated command of chromatic contrast and harmony, effectively enhancing both visual expression and spiritual symbolism.

Located in the ancient capital of Xi’an, the Huajue Lane Great Mosque shares many architectural features with the Daxuexi Lane Mosque, including its prayer hall, north and south chambers, and stele pavilion11 (

Hagras 2019b, pp. 97–113). Its overall colour palette is dominated by an understated combination of blue-grey bricks and dark grey tiles, conveying a sense of solemnity and elegance. The intricately painted wooden carvings make use of red, green, and gold hues, yet their stylistic conventions and decorative hierarchy remain consistent with the architectural traditions of the Central Plains, embodying a restrained yet profound aesthetic, as shown in

Figure 7.

As a paradigmatic example of the northern palace-style mosque, the Niujie Mosque in Beijing strictly follows the axial layout characteristic of traditional Chinese palatial architecture. Its colour strategy is deeply influenced by imperial aesthetics and ceremonial norms (

Hagras 2019a, pp. 134–58). Highly saturated hues such as vermilion, bright yellow, and gold are extensively employed: vermilion columns and window frames establish the architectural tone, symbolising authority and nobility. The beams and brackets are richly adorned with intricate xuanzi polychrome paintings, while the roofs are covered with green glazed tiles, all reflecting the hierarchical order and grandeur of official architecture. The mosque’s magnificent and imposing visual effect fully embodies the imperial capital’s cultural emphasis on ritual propriety and orthodoxy, as shown in

Figure 8.

In sharp contrast to the two examples above, the Phoenix Mosque in Hangzhou—shaped by the cultural milieu of the Jiangnan water towns—favours a cool colour palette dominated by blue, white, and green, creating a fresh and refined aesthetic atmosphere. These differences are deeply rooted in the regional cultural contexts of each site. Xi’an, as the heartland of Central Plains culture, tends toward a colour tradition of gravity and solemnity. Beijing, as the imperial capital, inevitably associates architectural colours with symbols of power and prestige. Hangzhou, by contrast, is imbued with the gentle climate, diffused light, and the restrained aesthetic sensibilities esteemed by Jiangnan literati, all of which contribute to the Phoenix Mosque’s elegant and understated chromatic character.

In summary, compared with the ornate grandeur of the Huajue Lane Mosque in Xi’an and the solemn opulence of the Niujie Mosque in Beijing, the Phoenix Mosque in Hangzhou stands out for its graceful and luminous colour scheme. This comparison eloquently demonstrates that the chromatic aesthetics of Chinese Islamic architecture do not conform to a single pattern. Rather, they represent an active adaptation and creative transformation of local cultural traditions under a shared religious core. The colour aesthetics of the Phoenix Mosque thus emerge as a unique product of deep aesthetic dialogue between Islamic civilization and the cultural continuum of Jiangnan.

7.2. Comparison with Coastal Islamic Architecture

In comparison with coastal Islamic architecture such as Qingjing Mosque in Quanzhou and Huaisheng Mosque in Guangzhou—both key nodes along the Maritime Silk Road—Fenghuang Mosque shares the commonality of being shaped by maritime trade and cross-cultural exchange while also exhibiting distinct characteristics shaped by its unique historical and environmental context. Coastal mosques demonstrate an openness and inclusivity in their colour choices, influenced by intercultural exchanges. White, symbolising purity and sanctity, is widely used in all three mosques: the white stone of Qingjing Mosque, the white walls of Huaisheng Mosque, and the white facades of Fenghuang Mosque all serve to evoke a solemn religious atmosphere. Furthermore, to accommodate humid climates and abundant natural light, colour selections tend to be fresh and bright across all three structures.

Despite these shared tendencies, each mosque demonstrates significant variation in its specific colour treatment. Influenced by early West Asian styles, Quanzhou’s Qingjing Mosque primarily features natural grey stone, producing a simple, dignified aesthetic with a pronounced foreign character, as

Figure 9 shows. Guangzhou’s Huaisheng Mosque integrates Lingnan regional elements and Central Plains traditions, resulting in colourful and richly layered decorations, including vibrant painted reliefs, as

Figure 10 shows. The Phoenix Mosque in Hangzhou, however, has taken a distinctive path, integrating the elegance and refinement of Jiangnan architecture with the solemn sanctity of Islamic architectural tradition. Its chromatic language is not confined to a single cool palette; rather, it employs white and grey-black as the foundational tones, accented with green and blue to evoke freshness, while incorporating bold applications of warm hues—such as red backgrounds with gilded embellishments—in key decorative elements. This combination achieves a delicate balance between simplicity and splendour. The overall style is minimalist, pure, and harmonious, creating a serene and tranquil spatial atmosphere.

The driving force behind these differences lies in the cultural environments of their respective cities. As a major international port in the Song and Yuan dynasties, Quanzhou’s architectural colours were directly influenced by West Asian culture. Guangzhou, as the heart of Lingnan culture, favours vibrant and intricate regional decoration. Hangzhou, as the epitome of Jiangnan culture, is shaped by a gentle natural environment and an aesthetic preference for light, refined elegance. This comparative analysis illustrates the diversity of colour aesthetics in coastal Islamic architecture within a shared cultural framework, offering valuable regional case studies for research and conservation of Chinese Islamic architectural colour systems.

To provide a more intuitive comparison of the similarities and differences in colour application between the Phoenix Mosque in Hangzhou and other representative mosques in China, their characteristics are summarised in

Table 1.

7.3. Comparative Summary

A cross-regional comparative analysis reveals that the colour system of Hangzhou’s Phoenix Mosque is rooted in the shared genetic foundation of Chinese Islamic architecture—namely, the universal veneration of religiously symbolic colours such as green, blue, and white. However, its ultimate manifestation is profoundly shaped by regional cultural influences. In contrast to the sumptuous solemnity of the Huajue Lane Mosque in Xi’an, the dignified richness of the Niujie Mosque in Beijing, the rustic simplicity of the Qingjing Mosque in Quanzhou, and the ornate brilliance of the Huaisheng Mosque in Guangzhou, the Phoenix Mosque stands out for its elegant and lucid aesthetic style. This “unity-in-diversity” colour pattern reveals that the essence of the localization of Islamic architecture in China lies in a creative dialogue between a shared religious core and distinct local cultural traditions. As such, the Phoenix Mosque serves as a paradigm of Jiangnan Islamic aesthetics, and its colour study not only bears individual significance but also provides critical insights into the mechanisms of cultural integration, as well as the precise preservation and contemporary innovation of architectural heritage.

8. The Contemporary Value of Architectural Colours in Phoenix Mosque

The architectural colour scheme of the Phoenix Mosque in Hangzhou serves as a model of cross-cultural integration between Chinese and foreign traditions, reflecting multifaceted core values in the contemporary context. It not only functions as a precious carrier of cultural heritage and an exemplary aesthetic model but also plays a pivotal role in tourism development and international cultural exchange, bridging historical memory with modern life, and connecting cultural spirit with economic activity.

From the perspective of cultural inheritance, the colour scheme of the Phoenix Mosque embodies the historical process of integration between Islamic and traditional Chinese cultures, serving as a vivid testimony to the localization of Islam in China. Since its inception in the Tang Dynasty and through successive restorations, the mosque’s colour aesthetics have evolved, incorporating religious beliefs, cultural elements, and prevailing stylistic trends of each era. The Islamic veneration for blue, white, and green intertwines with Chinese preferences for red and gold, forming a distinctive colour palette. This chromatic language visually manifests the mutual learning between civilizations, offering valuable material evidence for the study of the history of Islam in China and Sino-foreign exchanges. It plays a crucial role in deepening the understanding of historical trajectories, promoting the spirit of multicultural coexistence, and strengthening national cultural identity and pride.

From an artistic and aesthetic standpoint, the colour scheme of the Phoenix Mosque is uniquely captivating. While adhering to the formal norms of Islamic architecture, it creatively integrates the elegant and refined aesthetics of the Jiangnan region, resulting in a style characterised by clarity, harmony, and tranquillity. The use of cool tones—such as blue, white, and green—in the main prayer hall evokes a solemn and contemplative atmosphere, while the selective application of red and gold adds vibrancy and dignity. The colour application in murals, carvings, and window designs is exquisitely refined, showcasing the mastery of traditional craftsmanship. Even the surviving fragments of dome murals—featuring concentric circles filled with floral, avian, and landscape motifs—continue to inspire contemporary artists with their vivid hues and natural vitality, offering rich resources for innovation in colour usage, decorative design, and spatial composition, thereby contributing significantly to the advancement of contemporary art.

In the field of tourism development, the mosque’s architectural colours—blending Western and Chinese influences with Jiangnan charm—create a visually striking cultural landmark that plays an irreplaceable role in Hangzhou’s tourism industry. Visitors are drawn not only to its aesthetic appeal but also to its deep religious, historical, and intercultural significance. The Phoenix Mosque has thus become a vibrant cultural emblem that enhances the city’s visibility and reputation. Through thoughtful planning and sustainable development, its rich colour heritage can be transformed into an economic asset, stimulating local development, fostering the integration of culture and tourism, and achieving a synergy between heritage preservation and industry growth. At the international level, as a vivid representation of the “Belt and Road” cultural exchange, its unique colour language—fusing Eastern and Western aesthetics—offers a shared visual experience across diverse cultural backgrounds. This facilitates intercultural understanding, promotes inclusivity, and showcases the openness of Chinese civilization, contributing Chinese wisdom to the construction of harmonious global cultural relations.

In terms of craftsmanship inheritance and innovation, the colour aesthetics of the Phoenix Mosque encompass traditional techniques such as polychrome painting, carving, and glazed tilework, reflecting the superb skills of ancient artisans. These practices offer valuable reference points for contemporary art education and craftsmanship. The study and transmission of these colour-related techniques not only safeguard endangered skills and revitalise creative energy but also explore new paths for integrating traditional handicrafts with modern design. This effectively promotes the creative transformation and innovative development of traditional Chinese culture.

9. Conclusions

This study takes the Phoenix Mosque in Hangzhou as a case study to explore the distinctive patterns and cultural connotations of colour usage in Chinese Islamic architecture. The findings confirm that the architectural colour scheme of the Phoenix Mosque is the result of a profound integration between Islamic and traditional Chinese cultures, embodying a distinctive expression of Chinese characteristics. The formation of its colour features is primarily driven by two major forces—the fusion of religious cultures and the influence of regional traditions. The mosque’s colour system achieves a sophisticated synthesis between Islamic aesthetic principles and indigenous Chinese colours and cultural symbols, thereby creating a unique visual semiotic system.

In the contemporary context, the architectural colours of the Phoenix Mosque hold multidimensional significance. However, the preservation and development of such heritage face numerous practical challenges. From a technical standpoint, difficulties arise from pigment fading and restoration issues in ancient murals, as well as from the scarcity of traditional building materials. From a cultural perspective, there is a risk of oversimplifying complex cultural integrations into superficial symbols or commercial spectacles. Furthermore, there is an acute shortage of interdisciplinary professionals who possess combined expertise in religious studies, architectural history, and modern restoration technologies. To address these challenges, a systematic and sustainable development framework should be established, encompassing four strategic dimensions: scientific conservation and technological innovation; cultural education and public dissemination; talent cultivation and academic research; and integrative development with related industries. These measures will contribute to the creative transformation and innovative development of colour traditions in Chinese Islamic architecture—exemplified by the Phoenix Mosque—revitalising their cultural vitality in modern society.

The originality of this study lies in its systematic construction of an analytical framework for examining the colour system of the Phoenix Mosque. Through cross-regional comparison, it reveals the regional diversity of colour expressions in Chinese Islamic architecture and provides both theoretical foundations and practical pathways for their preservation and innovation. Future research could further employ digital technologies for precise colour measurement and virtual reconstruction, while extending comparative analyses to a wider range of cases, thereby enriching and refining the theoretical system of colour studies in Chinese Islamic architecture.