1. Introduction

From the Northern and Southern Dynasties (Nanbei chao 南北朝; 420–589) to the Sui 隋 (581–618) period, there were frequent cultural exchanges between China and other civilizations, which introduced a substantial influx of decorative motifs, significantly enriching China’s ornamental patterns. Many of these motifs initially took root in Buddhist art upon their arrival, becoming integral to the process of the Sinicization of Buddhism. By examining the origins and evolution of these foreign motifs, we can not only reconstruct specific processes of cross-cultural interaction but also observe how Buddhism assimilated diverse cultural elements from both Chinese and foreign traditions during its gradual Sinicization.

Among the many decorative motifs linked to foreign cultures during this period, a specific representation can be observed in Buddhist cave temples and individual statues. In this representation (

Figure 1), the human figures, either single or multiple and depicted as heads, busts or full figures, are positioned at the symmetrical center of a double-scroll pattern,

1 with the pattern symmetrical around them; these figures are hereinafter referred to as “double-scroll central figures”. This representation emerged abruptly in the latter half of the mid-Northern Wei Dynasty (

Beiwei zhongqi 北魏中期; 439–493), with no trace of its development identifiable prior to this stage. It can, thus, be regarded as one of the numerous foreign decorative motifs of that era.

In the past, scholars have conducted many discussions on peopled or inhabited scrolls (hereinafter referred to as “inhabited scrolls”), which are plant vines filled with inhabitants such as humans, birds, and animals.

Toynbee and Ward-Perkins (

1950, pp. 1–43) traced the inhabited scroll motif’s origins to the Late Classical and Hellenistic periods, noting its full development and zenith during the Roman Empire, with examples documented across nearly every province of the empire. As they observed, inhabited scrolls exhibited diverse possibilities in scroll forms, inhabitant types, and compositional relationships between scrolls and inhabitants. When this kind of motif is composed of two symmetrical single running scrolls on the left and right, and one or more human figures are depicted at the symmetrical center, it constitutes what this article calls “double-scroll central figures”. It seems that the practice of depicting figures in the center of double-scroll patterns originated from around the Mediterranean. Unfortunately, while Toynbee and Ward-Perkins’ research allows us to form a general understanding of such central figures in the Mediterranean region, it provides little detailed information regarding their developmental trajectory.

Claudine Dauphin investigated the evolution of inhabited scrolls in architectural sculpture and mosaic art from the late Roman Empire through the 7th century, analyzing the plant types, vine forms, the number of points of departure, and the types of objects around which these points were centered (

Dauphin 1987, pp. 183–212). Her research reveals that while the depiction of double-scroll central figures persisted in the Mediterranean region during the 4th–7th centuries, its occurrences became increasingly rare.

In recent years, Chang Ying 常櫻 has analyzed the development of inhabited scrolls from ancient Greece and Rome to the early Byzantine period, from Gandhāra and the Indian subcontinent, as well as from the Northern Dynasty (

Beichao 北朝; 386–581) period of China in her research on grape vine scroll patterns (

Chang 2024, pp. 299–354).

2 Her study noted the depiction of double-scroll central figures, but did not single it out as an independent type, nor did she link it with similar depictions in the West.

3The above studies on inhabited scrolls involve many examples of double-scroll central figures, and their relevant descriptions and clues of distribution over time and space offer valuable leads for this article. Based on these, we can roughly piece together a transmission trajectory from the Mediterranean to China regarding double-scroll central figures. However, previous studies focused on the decorative techniques that combined plants with images of humans, birds, and animals. Such studies encompassed all patterns that adhere to this compositional principle, which inevitably led to their generic understanding of the subject. The special depiction of double-scroll central figures in China and their inherent connection with similar examples in the West have not yet attracted enough attention from the academic community. How did the double-scroll central figures come about? How did they develop? How did they spread from the Mediterranean to China? What changes did they undergo after arriving in China? These are academic issues that need to be resolved.

In light of these considerations, this article focuses on double-scroll central figures as its primary subject. Building on a comprehensive collection of relevant materials (

Figure 2), the article centers on the depiction of these central figures, employing a combined methodology of archaeological typology and art historical stylistic analysis. First, by categorizing the figural representations according to their figural types, this article systematically examines representations from the existing materials in China to delineate their developmental trajectory. Subsequently, through comparative analysis with related examples from the Mediterranean and Central Asia, it traces the western origins and eastward transmission routes of these representations, while elucidating their innovative adaptations in China. By tracing the double-scroll central figures, this research reveals details of the Sinicization of Buddhism from a micro-perspective, while adding new evidence to the study of Sino-foreign cultural exchange.

2. Depictions of Double-Scroll Central Figures in China

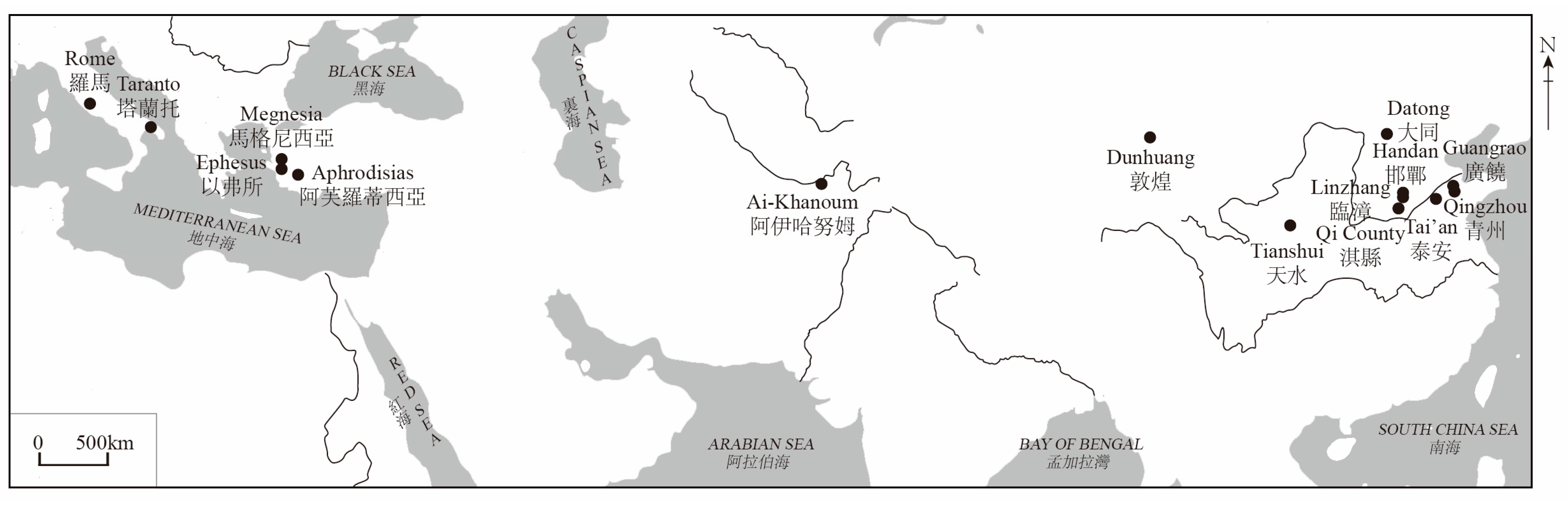

The author has compiled a total of 51 examples of double-scroll patterns with human figures as their central elements across China—all known surviving instances of the double-scroll central figures identified by the author to date—with the majority found in Buddhist cave temples and individual statues.

4 Among these cases, 37 (accounting for 72.55% of the total) originate from the Hexi Corridor, which functions as the primary hub for the development of this motif. In contrast, only 14 examples (merely 27.45% of the total) are from the Northern Central Plains (

Zhongyuan Beifang 中原北方).

5 Notable differences exist between the motifs in these two regions regarding their spatiotemporal distribution, artistic media, decorative positions, and, more crucially, the depictions of the central figures. Consequently, two relatively independent iconographic systems can be identified, which will be discussed separately in the following sections.

2.1. Hexi Corridor

The depiction of double-scroll central figures in this region flourished from the late 5th to the early 7th centuries, corresponding chronologically to the second phase (465–500) of the Northern Dynasty

6 to the Sui Dynasty

7 at the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang 敦煌. All the known examples are mural paintings adorning the arches of the image-holding shrines, predominantly concentrated at Mogao Grottoes, with isolated cases at the Western Thousand Buddha Caves (

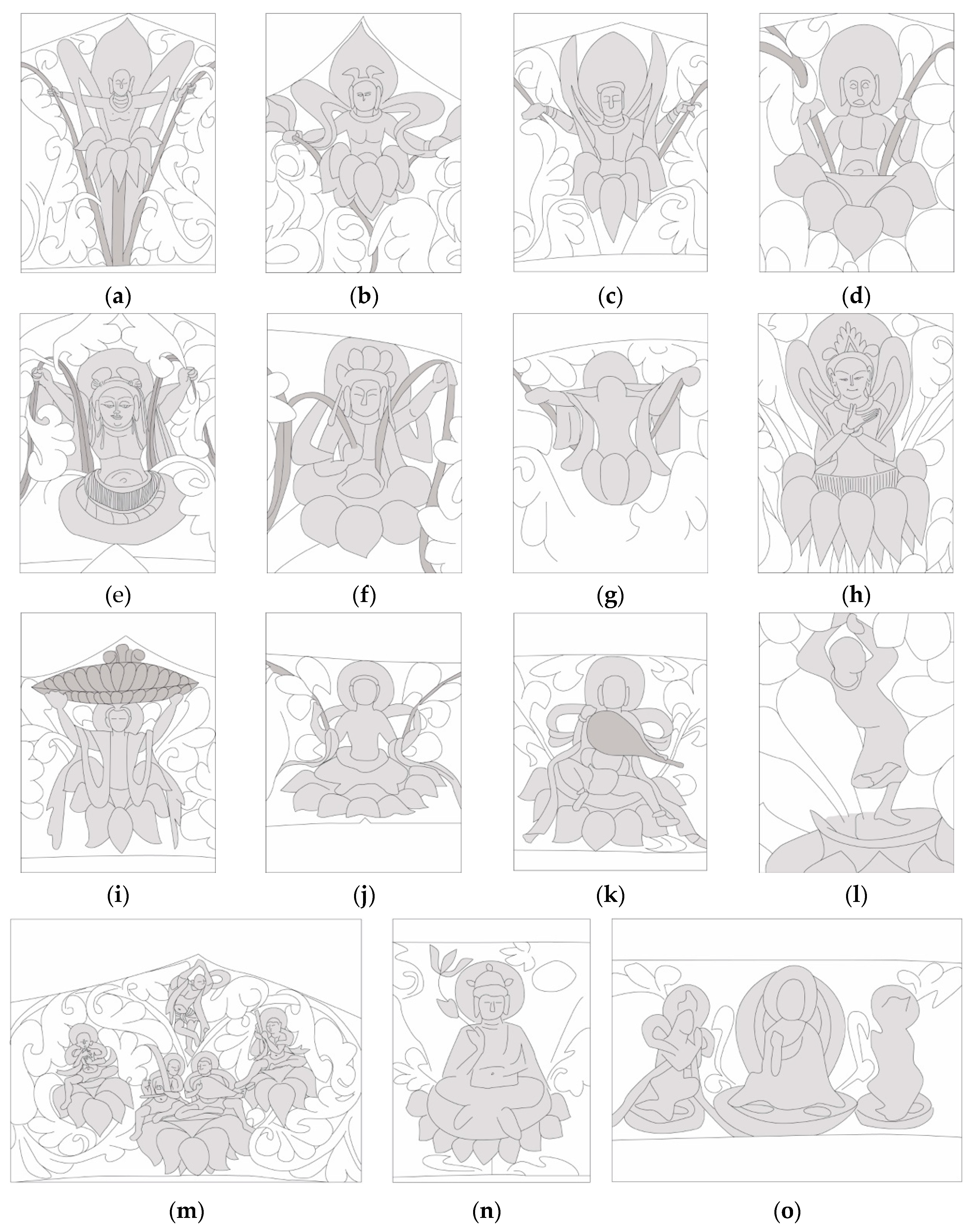

Xiqianfodong 西千佛洞). The figures can be divided into four types: lotus-born beings (

Lianhua Huasheng 蓮花化生;

Figure 3a–i), celestial beings (

Tianren 天人;

Figure 3j–m), bodhisattvas (

Figure 3n) and buddhas (

Figure 3o), and these will be examined one by one below.

2.1.1. Images of Lotus-Born Beings

There are 25 known examples of this, which constitute 67.57% of the total examples of the Hexi Corridor, representing the dominant category in this regional tradition.

In Buddhist doctrine, lotus birth refers to a type of transformation that spontaneously occurs through karmic force (

huasheng 化生), independent of the biological union of sperm and eggs. Lotus-born beings specifically refer to entities emerging from lotus blossoms, and maturing naturally following the unfurling of the lotus. In Mahāyāna and Western Pure Land sutras, lotus-born beings typically signify rebirth in the Buddhist Pure Lands. A lotus-born may take a Bodhi vow and may become an arhat, bodhisattva, or even buddha through practice.

8In this article, lotus-born beings refer specifically to individuals in the process of being born, with their heads or upper bodies emerging from lotus blossoms, and they are classified based on the ongoing lotus birth state. In contrast, celestial beings are defined by their fixed identity as deities or semi-divine entities in Buddhist heavenly realms; even if they once underwent a lotus birth, they are categorized as celestial beings according to their current divine status, rather than their birth process. For beings that have completed the lotus birth process—with some even having attained Buddhahood through spiritual practice—and stand or sit on a lotus, they will be discussed under the categories of celestial beings, bodhisattvas, or buddhas.

9From a representational perspective, the lotus wombs from which lotus-born beings emerge can be divided into two types: the side view and the oblique top view. Most depictions employ the side view, among which the inverted lotus is overwhelmingly dominant (

Figure 3a–d,f,h,i). The petals of the inverted lotus hang down like a skirt, clinging to the waist of the lotus-born figure; this not only creates a visual balance with the lotus-born image but also accentuates the figure’s slenderness and upright posture. Few examples use the oblique top view, where the corolla appears flat and circular, conveying the visual effect of looking down from a top angle slightly tilted toward the side (

Figure 3e). This abstract ring-shaped lotus has already appeared in the Mogao Grottoes during the first phase (421–439) of the Northern Dynasty (e.g., Cave 268, as illustrated in

Dunhuang wenwu yanjiusuo 1982, pl. 5), and may have been influenced by the cultural traditions of the Western Regions (

Xiyu 西域).

10The lotus wombs have different shapes, but the figures born from them show a common development trend. The known images of the lotus-born beings are all shown from the front, with round or peach-shaped halos, and are in the form of boys or celestial beings. Usually, their upper bodies are naked, adorned with shoulder shawls, necklaces, and bracelets. Their postures can be divided into the following three categories:

First emerging during the mid-Northern Wei period and persisting through the Sui period, this posture constitutes the dominant type for lotus-born figures. These figures grasp vine segments with both hands, and based on variations in their arm configurations, this study divides such postures into seven subtypes:

(4) Two arms forming a W-shaped flexion (

Figure 3d, also illustrated in

Duan 1998a, pl. 18): Elbows drawn close to the torso while maintaining forearm extensions. This posture—expansive yet restrained—represents the most prevalent vine-holding type among Dunhuang’s lotus-born figures.

(5) Two arms forming a diagonally V-upward thrust (

Figure 3e, also illustrated in

Duan 2006, vol. 3, pl. 67): This composition features the lotus-born figure’s two arms energetically raised in a steep V-angle, with pronounced muscular definition that underscores the posture’s dynamic tension. This posture exemplifies peak artistic expressiveness through its dramatic postural form.

11(6) One arm raised diagonally upward while the other bends across the chest, approximating an oblique L shape (

Figure 3f, also illustrated in

Duan 1998b, pl. 23).

(7) One arm horizontally extended with the other bent upward, forming an L shape (

Figure 3g, also illustrated in

Duan 1994, pl. 144).

The above postures gradually appeared, with the straight horizontal posture and the diagonal downward V-shaped posture in the mid-Northern Wei, the U-shaped posture and the W-shaped posture in the late Northern Wei (Beiwei wanqi 北魏晚期; 494–534), and the V-shaped posture, the oblique L-shaped posture, and the L-shaped posture in the Northern Zhou (Beizhou 北周; 557–581). Among them, the straight horizontal posture and the W-shaped posture are relatively more numerous, with the former being mainly popular in the middle of the Northern Wei and the latter being mainly popular from the Northern Zhou to the Sui period. These two postures succeeded one after another as the dominant depictions of the vine-holding lotus-born figures across different periods of Dunhuang.

- 2.

Mudra-Forming Posture

This is only seen in Cave 285 from the Western Wei (

Xiwei 西魏; 535–556). This posture features a frontal figure with both hands angled diagonally to the front left of the body in a gesture mimicking object-offering (

Figure 3h, also illustrated in

Duan 2006, vol. 2, pl. 85). Though the mudra appears unconventional compared to standardized Buddhist mudras, it is derived from the palms-together worship gesture typically seen in side-view depictions of such worshiping figures. Compared to frontal depictions of palm-raising gestures, the side-view better enhances the aesthetic articulation of hand contours. This might be the reason for combining the frontal depiction of the lotus-born figure with a side-view hand mudra.

- 3.

Lotus-Tray-Lifting Posture

This is seen in Cave 290 from the Northern Zhou (

Figure 3i, also illustrated in

Duan 1994, pl. 122) and Cave 266 from the Sui period (illustrated in

Guan 2003, pl. 167). The lotus-born figures have two arms forming a U-shaped flexion, lifting a circular-bottomed tray overhead. The posture is roughly consistent with the previously described U-shaped vine-holding posture, except that the hands are raised above the head, resulting in a wider range of motion. On the front face of the central pillar in Mogao Cave 288 of the Western Wei period, there is an image of a lotus-born holding up a tray at the center of the niche arch (illustrated in

Dunhuang wenwu yanjiusuo 1982, pl. 110). This depiction bears striking similarities to the lotus-tray-lifting figure in Cave 290, and it may have served as an inspiration for the latter. From this evidence, it seems that the emergence of lotus-born figures lifting up a lotus tray at the center of double-scroll patterns may be influenced by both the practice of placing tray-holding lotus-born figures at the center of the niche arches in the Mogao Grottoes and the images of lotus-born figures originally positioned at the center of niche arches.

Of the three postures mentioned above, the one holding vines emerged the earliest, persisted the longest, and developed the most fully. No traces of this posture’s development can be found in China prior to its appearance; as will be discussed later, it should be a product influenced by Greco-Roman motifs. After the vine-holding posture appeared, the mudra-forming posture and the lotus-tray-lifting posture emerged successively. Similar representations of these two postures can be found in local Dunhuang figure images—they were likely developed on the basis of the compositional schema of earlier vine-holding figure images, where the figures holding vines would have been replaced with those modeled in local Dunhuang style.

2.1.2. Images of Celestial Beings

There are nine known examples of such images, with one dating to the Northern Zhou Dynasty and eight to the Sui Dynasty. Their lotus bases are usually shown from the side, and their postures can be categorized into three types:

There are five known cases of Sui-dynasty celestial beings in this posture, with a naked upper body and draped sashes, wearing skirts or loincloths. Among these examples, one features a celestial being with two arms forming a diagonal downward V shape (illustrated in

Guan 2003, pl. 202), and four feature celestial beings with two arms forming a W-shaped flexion (

Figure 3j, also illustrated in

Guan 2003, pl. 173). These two postures can both be found among the lotus-born figures holding vines as described previously. From their emergence, given that these two postures in celestial beings appeared later than their counterparts in lotus-born figures, the vine-holding postures of celestial beings were probably influenced in modeling by the similar postures of lotus-born figures.

- 2.

Mudra-Forming Posture

This posture is only found in Cave 383 of the Sui Dynasty (illustrated in

Guan 2003, pl. 182). The Celestial being’s attire is roughly the same as that of the vine-holding celestial beings described previously and both of the being’s hands rest before the abdomen.

- 3.

Music-and-Dance Performing Posture

There are three known cases of such images. They have similar performances, but differ in content. In Cave 299 of the Northern Zhou (

Figure 3m, also illustrated in

Duan 2006, vol. 3, pl. 173), a celestial being is on the top, clapping his raised hands, twisting his waist and hips, kicking his right leg forward, and dancing passionately. Two celestial beings are below him, sitting symmetrically on the same lotus seat, playing the

konghou 箜篌 (plucked string instrument) and

pipa 琵琶 (plucked lute), respectively. There is a celestial being in each of the vine units on both sides, sitting on the inverted lotus and playing the

sheng 笙 (free reed pipe) and

xiao 簫 (end-blown flute), respectively. These five celestial beings are dressed in the same way, and their movements and eyes resonate with each other. They undoubtedly form a group performance, which is the most sophisticated lineup among the known examples. In Cave 314 of the Sui period (

Figure 3k, also illustrated in

Guan 2003, pl. 176), a celestial being is sitting on a lotus and playing the

pipa. His clothing and sitting posture are similar to those of the

pipa player in Cave 299.

In Cave 420 of the Sui period (

Figure 3l, also illustrated in

Dunhuang wenwu yanjiusuo 1984, pl. 65), a celestial being dances on a lotus, with a posture similar to that of the dancer in Cave 299. This dancer wears a round-necked robe reaching down to the knees and high boots, dressed as a

Hu 胡 (non-Han, specifically Central Asian) person. The same type of

Hu dancers were also found in the dance scenes on the stone couch screen unearthed from the tomb of the Sogdian An Jia 安伽 (518–579), dated to the first year of the Daxiang 大象 period (579) of the Northern Zhou (illustrated in

Shaanxi sheng kaogu yanjiusuo 2001, p. 17, Figure 21;

Shaanxi sheng kaogu yanjiusuo 2003, pl. 63). Academics generally agree that the dance depicted in the An Jia tomb reflects the

Huteng 胡騰 (

Hu Leap) Dance scene.

12 Therefore, the dancers in Dunhuang should have also performed the

Huteng Dance, which is part of the Central Asian culture that spread when the Sogdians entered China. In the Buddhist grottoes,

Hu dancers step and jump on the lotus platforms to the rhythm of Buddhist music. This scene may be a true portrayal of the local people who use the

Hu Dance to pay homage to Buddhism.

2.1.3. Images of Bodhisattvas

These are only seen in Cave 390 (illustrated in

Dunhuang wenwu yanjiusuo 1984, pl. 162) and Cave 412 (

Figure 3n, also illustrated in

Dunhuang wenwu yanjiusuo 1984, pl. 86) of the Sui Dynasty. The bodhisattvas wear jeweled crowns, with the left hand resting at the abdomen and the right hand holding a long lotus stem at chest height. The depiction of lotus stem-holding bodhisattvas flourished in Sui period Mogao Grottoes, and it potentially influenced the development of depictions of bodhisattvas at the center of double-scroll patterns.

2.1.4. Images of Buddhas

These are only seen in Caves 401 (illustrated in Dunhuang wenwu yanjiusuo 1984, pl. 139) and 397 (

Figure 3o, also illustrated in

Dunhuang wenwu yanjiusuo 1984, pl. 150) of the late Sui to early Tang 唐 (618–907) period. The buddhas sit in full lotus position, with the right hand raised in abhaya mudra (fearlessness gesture) while preaching the dharma. Interestingly, the latter depicts two bodhisattvas, each sitting with hands clasped on one side of the buddha, which actually constitutes a small scene of lecturing the dharma. As will be described later, the practice of depicting a buddha figure at the center of double-scroll patterns appeared during the mid-to-late Northern Wei period in the Northern Central Plains and continued to evolve. The practice of depicting people in a row on the niche arches was also mainly popular in the Northern Central Plains since the mid-Northern Wei period. In many cases, an image of buddha sitting cross-legged, meditating, or lecturing the dharma is depicted in the center of the arch, and one or more bodhisattvas kneeling with hands clasped on either side are symmetrically depicted (such as the arch of the second niche in the middle layer of the east wall of Cave 2 in Yungang Grottoes, Datong 大同, for illustration, see

Yungang shiku wenwu baoguansuo 1991, pl. 12). The buddha figure at the center of double-scroll patterns that appear sporadically on arches of the Mogao Grottoes are likely to be influenced by both of these depictions from the Northern Central Plains.

Two points can be observed overall. First, all double-scroll central figures in the Hexi Corridor are exclusively painted as murals on Buddhist niche arches within cave temples. Among these, lotus-born beings emerged as the earliest, most enduring, and with the most numerous samples, exhibiting the richest formal variations. They are the defining characteristic of this regional tradition. Images of celestial beings emerged during the Northern Zhou and flourished in the Sui period, while images of buddhas and bodhisattvas only emerged in the Sui and remained rare exceptions.

Second, from the mid-Northern Wei to the Western Wei period, the central figures were all depicted as lotus-born beings with their heads or upper bodies emerging from lotuses. In the Northern Zhou period, images of full-body celestial beings appeared. In the Sui period, images of bodhisattvas and buddhas appeared continuously, and the number of images of full-body figures exceeded that of the lotus-born beings, becoming an interesting cultural phenomenon of this period.

Huasheng 化生 (spontaneous birth) is regarded as the highest of the four modes of birth (

Luansheng 卵生,

Taisheng 胎生,

Shisheng 湿生,

Huasheng). The images of lotus-born beings are likely depictions that emphasize their mode of birth (i.e., emerging from a lotus). The focus of the depictions of celestial beings, bodhisattvas, and buddhas shifted toward various extraordinary figures who emerge from the lotus and grow to maturity or even attain enlightenment through practice, with emphasis likely placed on the states that can be achieved after such lotus-based emergence. This shift in figural types may reflect a transformation in people’s aspirations—from being content with rebirth in Buddhist Pure Lands

13 to striving to continue Dharma practice in pursuit of Buddhahood (i.e., ultimate liberation).

14 2.2. Northern Central Plains

The depiction of double-scroll central figures from this region was popular from the end of the 5th century to the 6th century, roughly corresponding to the latter half of the mid-Northern Wei to the Northern Qi (

Beiqi 北齊; 550–577) period. Examples are distributed in Datong 大同, Shanxi Province 山西, which is part of the Pingcheng 平城 (capital of the mid-Northern Wei, now Datong) region; Tai’an 泰安, Guangrao 廣饒, and Qingzhou 青州, Shandong Province 山東, which are part of the Qingzhou region—a major hub for Buddhist art in eastern China; Qi County 淇縣, He’nan Province 河南, and Linzhang 臨漳 and Handan 邯鄲, Hebei Province 河北, which are part of the Ye City 鄴城 (capital of the Eastern Wei [

Dongwei 東魏; 534–550] and the Northern Qi, now Linzhang) region; and Tianshui 天水, Gansu Province 甘肅, which is part of the Eastern Gansu (

Longdong 隴東) region—a vital link connecting the Western Regions to the Central Plains (

Figure 2). Most of them are stone carvings in relief, and a few are cast in gilt bronze. They are mainly applied to the halos and their adjacent areas of buddha images, and a small number are also applied to the arches of niches and the edges of steles.

2.2.1. Images of Lotus-Born Beings

There are three known examples of this. The earliest one was found in the lower western niche of the south wall of Cave 11 in Yungang, which was excavated around 470–493 CE (

Figure 4a), and later in the lower level niche of the No. 10 Buddhist stele in Cave 133 in Maijishan 麥積山 Grottoes, Tianshui, around 520 CE (

Figure 4b). The lotus-born figures at the center of both arches are born from the inverted lotus with their hands clasped together, and the lotus-born beings are carved in the vine units on both sides, which is obviously a continuation of the same tradition. This type of arch is rare in the Northern Central Plains, and it is more likely to have come from the Hexi Corridor.

On the upper front edge of the base of the Buddhist stele with inscription dated to the first year of Wuding 武定 (543) of the Eastern Wei, the upper body of the lotus-born figure emerges out of the inverted lotus, with the two arms forming a diagonal downward V shape and each hand holding a section of the vine (

Figure 5). The posture of the lotus-born figure holding vines is almost the same as that found in the aforementioned Cave 432 of the Western Wei among the Mogao Grottoes (

Figure 3b), and there is a high possibility of a connection between them. Of course, this example also contains some differences from the example of the lotus-born figure holding vines on the arch of Mogao Grottoes in terms of its placement, the attire of the lotus-born figure at the center, and the elements in vine units on both sides. These differences should result from the practical adaptation of the same motif to local aesthetic preferences.

2.2.2. Images of Celestial Beings

Two known examples of this exist. The first is found in the lower niche on the east wall of Cave 13 at the Yungang Grottoes (illustrated in

Mizuno and Nagahiro 1953, vol. 10, rubbing 2D). Here, the celestial being’s two arms form a U shape, with each hand grasping a vine segment. This represents the earliest known instance of a celestial being holding vines. The figure’s positioning and the holding of vines closely correspond to those seen in lotus-born beings from Dunhuang, suggesting it likely evolved from the Dunhuang tradition. The second example appears on a fragmented mandorla from an image of a white marble statue of the Northern Qi, excavated at the Ye City site in Linzhang (

Figure 6). Here, the celestial being flies while prone atop the halo of the destroyed main figure, pulling the vine with one hand above and the other below. The placement of the celestial being above the outer edge of the main figure’s halo aligns with the positioning seen in later images of buddhas at the center of the double-scroll pattern from the Qingzhou region. The unique configuration of hands pulling vines from both above and below has no known parallel examples, indicating a distinctive creative depiction unique to the Ye City area.

2.2.3. Images of Buddhas

Nine known examples of this exist, representing the primary type of double-scroll central figures in Northern Central Plains. Three examples from the late Northern Wei have been discovered in the Qingzhou region. The buddhas are seated in full lotus posture, either in groupings of five or nine or depicted individually. All are consistently positioned above the outer edge of the main figure’s halo. The earliest example appears on a gilt bronze mandorla from the eighteenth year of the Taihe 太和 period (494), unearthed in Wentou Village 汶口村 of Tai’an (

Figure 7a, also illustrated in

Tai’an shi wenwu guanliju 1987, p. 663, Figure 2:5).

15 Here, the buddha belongs to a grouping of five buddhas, evenly spaced along the outer rim of the halo yet detached from the vine. This is different from the previous examples that were mainly applied to niche arches where the figures were placed in the vines. This is a new development for double-scroll central figures. Later, the mandorla image unearthed in Xiwang Kongzhuang 西王孔莊, Qingzhou, in the sixth year of the Zhengguang 正光 period (525) (

Figure 7b), further combined the double-scroll central figures with the popular local motif of a dragon holding vines, which is positioned at the upper section of the mandorla. This integration is achieved via the sharing of vine elements, which bind the two components together and form a type of depiction with Qingzhou characteristics. In the mandorla image unearthed in Dazhang Village 大張村 of Guangrao (

Figure 7c), the buddha appeared individually, but was still placed above the halo, showing the strong influence of the Qingzhou tradition.

The halo of the main buddha on the central wall of Western Wei Cave 127 at the Maijishan Grottoes features a single buddha positioned at the upper section of the outer rim, serving as the central element of the halo’s double-scroll pattern, with the vines depicted at the middle rim (illustrated in

Hua and Wei 2013, pl. 100). This compositional style—characterized by the halo as the decorative carrier and the buddha figure in an elevated position—aligns with earlier examples from the Qingzhou region, suggesting artistic influence originating from the eastern Central Plains.

Five Northern Qi examples have been identified in the Xiangtangshan 響堂山 Grottoes near Handan. These all appear on the halos of the main buddha images—specifically, those on the central and side walls of the Southern Cave (Nandong 南洞) at Northern Xiangtangshan, and those on the frontal face of the central pillars in Caves 1 and 2 at Southern Xiangtangshan (

Figure 7d). Here, the central buddha within the double-scroll pattern forms part of a grouping of seven buddhas. All seven figures are relocated to the outer rim of the halo and integrated into the vines. While inheriting Qingzhou’s tradition, this configuration introduces a distinct stylistic departure.

Overall, the double-scroll central figures found in the Northern Central Plains are mostly represented in relief, and their locations have shifted from niche arches to statue halos and their adjacent areas. The shift in the motif’s carrier from Buddhist niches to nicheless free-standing statues may account for this change in placement.

In terms of the figural types, images of lotus-born beings and celestial beings appeared earlier but in extremely limited numbers, and there is no clear evolutionary connection between their Northern Wei examples and those from the Eastern Wei and Northern Qi. They were likely products of cultural exchanges at different stages. Depictions of these two figural types holding vines are closely related to examples from the Hexi Corridor, and they likely share a common cultural origin. By contrast, images of buddhas appeared in the mid-to-late Northern Wei, with relatively more examples. The evolutionary relationship between their Northern Wei examples and those from Northern Qi is fairly obvious. They likely originated in the Qingzhou region before spreading to influence regions such as Eastern Gansu and Yecheng.

3. Depictions of Double-Scroll Central Figures in the Mediterranean Region

The practice of placing human figures in the center of double-scroll patterns has no precedent in China. Based on extant evidence, as mentioned earlier, this depiction appeared in the Mediterranean world by at least the late Classical Greek period (5th–4th centuries BCE) and continued to develop through the Hellenistic (334–30 BCE), Roman Republican (509–27 BCE), and Roman Empire (27 BCE–476 CE) periods.

In the second half of the 4th century BCE, the practice of depicting human figures in the center of scroll patterns appeared in the Greek colonial city-states in South Italy and developed considerably. Examples can be found in many Apulian Red-Figure vases used for funerals.

16 The figures are either depicted in full-body or half-body. The full-body images are either one person or two people, sitting sideways on flowers and leaves (such as the neck band of the terracotta volute-krater, dated to circa 340–320 BCE, with number 17.120.240 in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York), which is quite different from the examples found in China. The half-body images are often combined with flowers and leaves, which are comparable to the examples in China. For example, the lower portion of the vase from the National Archaeological Museum of Altamura (

Figure 8a) and the neck of the vase (no. St.135026) in the Milan Archaeological Museum (

Figure 8d) feature busts emerging from acanthus leaves and flowers

17 with a design similar to the lotus-born figures. The neck of the terracotta Loutrophoros (No. 82.AE.16) in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum (

Figure 8e, also illustrated in

Jentoft-Nilsen and Trendall 1991, pls. 183, 185) shows that the lower body of a winged woman merges into acanthus leaves, with her two arms forming a diagonal downward V shape, and her hands are pulling the tendrils on both sides. The design is similar to that of a lotus-born figure, especially the figure holding vines in a diagonal downward V-shaped configuration.

By the late 3rd century BCE at the latest, this type of depiction had spread to the Eastern Mediterranean region, including modern-day Turkey. A relief from the Temple of Artemis Leukophryene at Magnesia (illustrated in

Toynbee and Ward-Perkins 1950, pl. II, 2), for example, portrays a winged goddess whose lower body merges into acanthus leaves. Her arms extend horizontally, both hands gripping the central stems of vines. The figure in this example holds the main stem, a detail that differs from the previous example (

Figure 8e), where the figure grasps the tips of the tendrils. Such stem-holding depictions were inherited by later examples from the Roman Empire (

Figure 8f). The double-scroll central figures in China consistently hold the main stem of the vine. Notably, this particular characteristic can be traced back to these Hellenistic to Roman Imperial depictions, suggesting a tighter link between Chinese and Hellenistic to Roman Imperial tradition.

From the end of the Roman Republic to the Roman Imperial period, the practice of depicting double-scroll central figures saw further development, and examples were widely found in Mediterranean coastal regions, including Southern Europe, Western Asia, and North Africa. The depiction of human figures generally continued the ancient Greek tradition, with half-body figures still combined with flowers and leaves, and full-body figures appeared in a new form of standing frontally on flowers and leaves. Both half-body and full-body figures include examples of holding vines in both hands. For example, the semi-circular arch mural unearthed from the tomb of Morlupo in Rome around 30 BCE (

Figure 8b) and the semi-circular arch relief on the upper part of the second arch of the Temple of Hadrian in Ephesus, Turkey, in the 2nd century (

Figure 8c)—the former features a winged figure, and the latter a figure with animal claws—have lower bodies merging into acanthus leaves, arms forming a diagonal downward V shape, and hands grasping a vine on each side. In the 2nd-century stucco band decoration of the Roman tomb of the Valerii (illustrated in

Toynbee and Ward-Perkins 1950, pl. VI, 2), the figure stands frontally on leaves, with the arms forming a W-shaped flexion and the hands grasping a vine on both sides.

During this period, the continuous wavy-shaped structure of the vines held by the central figures became more distinct, with the wavy sections (vine units) adorned with elements such as flowers, leaves, humans, and animals, creating a more dynamic atmosphere. For example, in the 2nd–3rd century reliefs from Aphrodisias, Turkey (

Figure 8f, also illustrated in

Toynbee and Ward-Perkins 1950, pl. XXIII;

Rawson 1984, p. 34, Figure 13b), the upper body of a winged figure emerges from acanthus leaves; the vines held in its hands form a continuous S shape; and the vine units are embossed with children in various poses. In the relief band on the upper part of the first arch of the Temple of Hadrian in Ephesus (

Figure 8g), not only the central figure but also the humans and animals within the vine units are depicted as emerging from flowers or leaves. In terms of the continuous vine structures, the inclusion of human figures within vine units, and the combination of flowers or leaves with emerging figures, the vine forms and figural representations of this period seem to be closer to the depictions found in China. When these similarities are coupled with the previously noted trait of figures holding the main stem, the origin of the Chinese double-scroll central figures appears to be further narrowed down to the Roman Imperial period.

Overall, Greco-Roman double-scroll central figures, represented in media such as vase paintings, murals, and reliefs, were mainly used in settings such as funerary contexts and temples with mythological themes. Among these figures, the full-body ones, which either sit sideways or stand frontally on flowers or leaves, bear little comparability to China’s full-body depictions of celestial beings, bodhisattvas, and buddhas, suggesting no inherent connection between these two full-body figure types. The half-body ones, integrated with flowers and leaves and grasping vines with both hands, bear strong similarities to China’s lotus-born figures—figures that emerge from lotus blossoms while holding vines. Chinese figures consistently grasp the main vines, a detail particularly resonant with examples from the Hellenistic to Roman Empire periods. Furthermore, the continuous S-shaped form of the main vine and the incorporation of human figures within vine units are more closely related to examples from the Roman Empire. Based on these observations, the depiction of Chinese double-scroll central figures, especially the lotus-born figures holding vines, likely originated from traditions associated with the Mediterranean region—with the Roman Empire’s traditions being the most prominent influence.

4. Transmission Pathways of Double-Scroll Central Figures

A crescent-shaped bronze plaque (prior to 145 BCE) from Ai-Khanoum, Afghanistan (

Figure 9, also illustrated in

Tissot 2006, p. 42), features a high-relief female bust flanked by two vines. This artifact provides clues for exploring the eastward spread of double-scroll central figure depictions. Similarly to the aforementioned early Hellenistic pottery vase pattern (

Figure 8a), this depiction is a Mediterranean cultural element that likely took shape as a direct outcome of Alexander the Great’s Eastern Expedition (334–323 BCE) and the subsequent Hellenistic movement, which persisted across Alexander’s former empire after his death. During his campaign, Alexander conquered territories spanning from Anatolia and Egypt eastward to the Indus River Valley, encompassing modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan, which later became the core of Gandhāran culture. While Roman influence, particularly during the Kushan Dynasty (c. 1st–3rd century CE), may have further shaped and sustained the depiction of double-scroll central figures in Gandhāran Buddhist art, which rested on the earlier Hellenistic foundations, the absence of surviving examples of such depictions means no further analysis of this potential continuity is currently feasible.

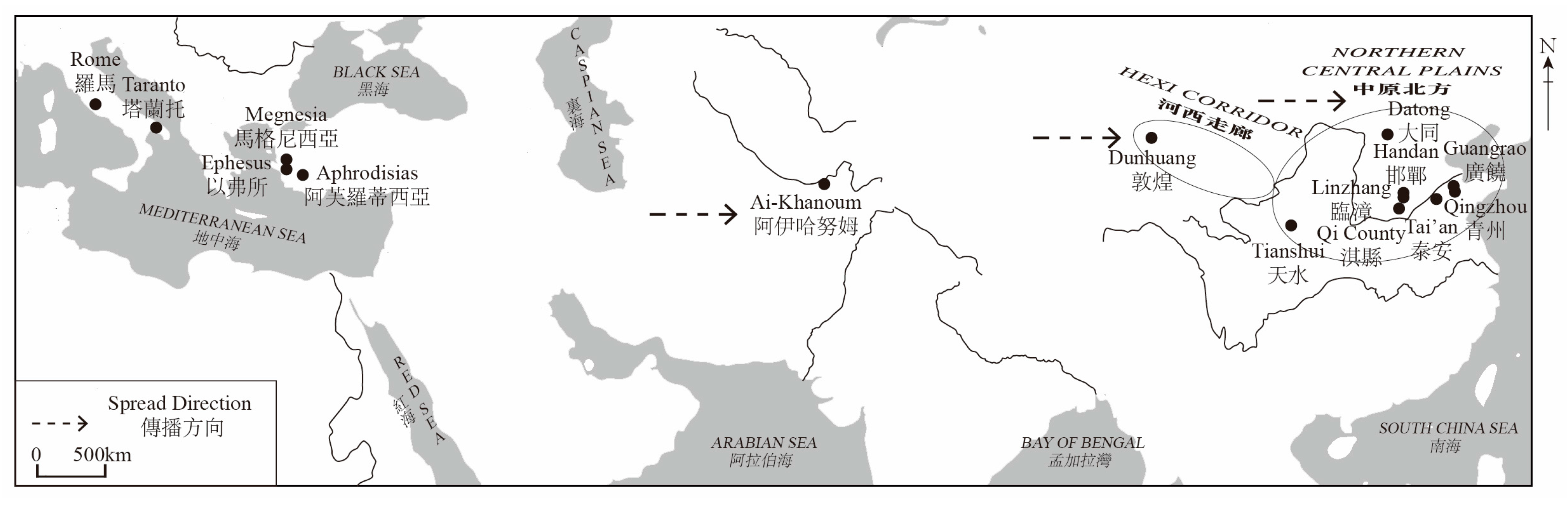

As noted earlier, all known examples of double-scroll central figures in China are distributed in the Hexi corridor and the Northern Central Plains. Considering that this motif is primarily found in Northern China, there is little doubt that it was introduced via the overland Silk Road.

To date, no such depictions have been identified in Gandhāran Buddhist images, a Greek-Roman-influenced tradition that exerted a major influence on 5th-century Chinese Buddhist art and profoundly shaped its appearance; nor in the Western Regions, a critical Silk Road hub for transmitting Buddhism and foreign cultures to the Central Plains.

18 Though both Gandhāra and the Western Regions played important roles in cultural transmission, even as this study hypothesizes that the motif spread eastward via overland routes, the absence of traces of double-scroll central figures in these regions means their role in this motif’s transmission cannot be further elaborated.

Given that no traces of the motif have been found in the Buddhist art west of the Hexi Corridor, comparable Chinese Buddhist depictions were likely the result of the creative absorption and adaptation of Greco-Roman motifs by Chinese communities, and can be regarded as the product of the Sinicization of Buddhism. The motif was probably introduced via objects linked to the Mediterranean rather than through the direct spread of Buddhism. These objects likely fall into two categories of Mediterranean cultural carriers: original Mediterranean goods and Mediterranean-style imitations made in Central Asia.

19Within China, examples from the Hexi Corridor are concentrated in the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, where they decorate niche arches. The earliest examples in the Northern Central Plains appear in the Yungang Grottoes in Pingcheng, where they also adorn niche arches. The two sets of examples emerged around the same time, decorated identical locations, and featured lotus-born figures within the vine units flanking the central figure—all indicators of shared design concepts. In the past, scholars have noticed the similarities between the two groups of examples and believed that Dunhuang’s motifs were influenced by the new artistic style of the capital Pingcheng (

Chang 2024, pp. 346–48). However, when foreign prototype examples are taken into consideration, this “capital-to-local” transmission pathway becomes difficult to sustain.

As previously noted, among Dunhuang’s double-scroll central figures, depictions of lotus-born beings are particularly notable for their advanced state of development: they emerged earliest, persisted longest, appeared in the greatest quantity, and exhibited the most diverse representations. This developed state, in turn, establishes them as the defining characteristic of such central figure motifs in the Hexi Corridor. Among these lotus-born depictions, those in vine-holding postures appeared first and remained consistently prevalent during the Northern Dynasties and Sui Dynasty. Early vine-holding postures, such as the straight line, diagonal downward V shape, and W-shaped flexion, all have parallels in Greco-Roman examples. By contrast, in Pingcheng’s central figures, lotus-born beings and celestial beings appeared earlier but exist only sporadically. Furthermore, early depictions of lotus-born beings with clasped hands and celestial beings holding vines in a U shape bear very little similarity to Greco-Roman prototypes. It is reasonable to conclude that Mediterranean double-scroll central figures were likely first introduced to Dunhuang, then spread eastward to influence Pingcheng, and later expanded to the Northern Central Plains (

Figure 10).

In the mid-5th century, Emperor Taiwu 太武帝 (408–452; r. 423–452) of the Northern Wei unified the Yellow River Basin and gained control of the Hexi Corridor, reopening the trade route connecting the Central Plains to the Western Regions and revitalizing East–West cultural and commercial exchanges (

Shi 2007, pp. 145–52). Along this route, a large number of people including Sogdian-led merchants, Sino-foreign envoys, and Buddhist practitioners traveled between East and West. Exotic artifacts (such as Mediterranean goods or their Central Asian imitations) and associated Western cultural elements flowed into the Central Plains on a large scale (

Li 2023, pp. 15–34). The Northern Wei rulers, hailing from the Tuoba Xianbei 拓跋鮮卑 (a nomadic ethnic group), maintained openness to foreign cultures; this, coupled with the elite’s fascination with exotic curiosities, further stimulated the import of foreign artifacts. In this context, cultural elements originating from Central Asia, Western Asia, and even the Mediterranean region spread relatively smoothly into the Central Plains. The artistic practice of depicting double-scroll central figures was likely one of the many exotic motifs introduced to the Northern Central Plains via the Hexi Corridor during this period.

5. Chinese Buddhist Adaptations of Double-Scroll Central Figures

In the second half of the 5th century, Emperor Wencheng 文成帝 (440–465; r. 452–465) of the Northern Wei revived Buddhism after the Fanan 法難 (the disaster of Buddhism, a large-scale persecution roughly spanning 444–451). This revival created a pivotal opportunity to expand cave excavation and statue creation. Buddhist images of this period, exemplified by those at the Dunhuang and Yungang Grottoes, underwent extensive localization (Sinicization) while actively absorbing Western cultural elements. The artistic practice of depicting double-scroll central figures was among the foreign cultural elements that contributed to this phase of Buddhist Sinicization.

From the Mediterranean to China, double-scroll central figures were integrated into Buddhist art, leading to Sinicization in both their appearance and content. Their cultural context shifted from funerary and temple settings to the Buddhist cosmos; their symbolic identity transitioned from mythological motifs to Buddhist figures; their visual traits changed from shoulder wings to head halos; and their postures and attributes were fully incorporated into Buddhist iconography.

Alongside these adaptations, the overall function and symbolic character of double-scroll central figures underwent a fundamental transformation in Chinese Buddhist art. On the one hand, the central figures of the double-scroll pattern, together with the lotuses, lotus-born beings, and celestial beings within the flanking vine units, serve a decorative role, creating a pure, serene, and blissful atmosphere befitting the Buddhist realm. On the other hand, these central figures also support the main buddha’s role in preaching and guiding sentient beings, embodying the Buddhist ideal that devotees who honor the Dharma and make pious offerings will be freed from rebirth in hell or the womb. Instead, such devotees will be reborn from lotuses in the Buddhist Pure Land to listen to the Dharma perpetually and ultimately attain Buddhahood. In this sense, the central figures and their surrounding decorative elements vividly depict the ideal spiritual destination of Buddhist practitioners.

As a frontier adjacent to the Western Regions, the Hexi Corridor adopted this foreign motif relatively early and long featured half-body figures holding vines, a form closely tied to Greco-Roman traditions. Throughout its development, the region continuously absorbed cultural elements from various areas and preserved traits of diverse cultures. The four types of central figures in Dunhuang grotto murals provide clear evidence of this synthesis. For instance, lotus-born beings retained Greco-Roman vine-holding postures while integrating the local lotus-tray-lifting posture and mudra-forming gesture, as well as the Western Regions-inspired depiction of lotuses from an oblique top view; celestial beings incorporated Sogdian cultural traits through imagery of Hu dancers; bodhisattvas conformed to local Hexi iconographic norms, either holding vines like lotus-born beings or holding a lotus stem like their counterparts; and niche-arch buddhas bore traces of artistic influence from the Northern Central Plains.

By contrast, the Northern Central Plains, rooted in the core of Han culture, adopted a more localized adaptation strategy. Examples of half-body figures holding vines are scarce here, whereas full-body Buddha images developed relatively fully. This region reimagined the foreign motif within its own cultural framework, producing distinctive variations: the fusion of the motif with Han auspicious symbols, as evidenced by dragons clutching vines; the integration into compositions featuring five or seven buddhas, which are arranged around halos to create symmetry in line with Han aesthetic preferences; and the placement of central figures above the vines, a design likely aligned with Han culture’s emphasis on prioritizing human figures over floral elements. Over time, such localized reinterpretations distanced the motif further from its Greco-Roman prototypes.

It can be seen that the adaptation of this Greco-Roman motif in Chinese Buddhist art, shaped by the dual processes of Buddhization and Sinicization, highlights the pivotal role of multicultural interaction. Local indigenous cultures, Han culture, the cultures of the Western Regions, and Central Asian Sogdian culture all contributed to driving these adaptations. Yet amid the ebb and flow of these cultural elements, regional cultural contexts played a decisive role in shaping the trajectory of the motif’s adaptation. It is precisely this dynamic, where regional contexts held sway over the interplay of diverse cultural influences, that gave rise to the divergent developmental trajectories of double-scroll central figures between the Hexi Corridor and the Northern Central Plains.

6. Conclusions

In summary, the Greco-Roman motif of double-scroll central figures was transmitted to China via the overland Silk Road during the latter half of the mid-Northern Wei period, giving rise to two distinct yet interrelated iconographic systems: one in the Hexi Corridor and the other in the Northern Central Plains.

The Hexi Corridor tradition, with the Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes as its core, was primarily applied to the arches of Buddhist niches. A defining feature of the central figures here is the depiction of lotus-born beings holding vines. Over time, these figures evolved from lotus-born beings to celestial beings, bodhisattvas, and buddhas, while their postures shifted from vine-holding to mudra-forming, lotus-tray-lifting, and music-and-dance performing, forming a clear evolutionary trajectory. By contrast, the Northern Central Plains tradition developed sequentially with Pingcheng, Qingzhou, and Yecheng as its successive hubs, and was mainly applied to the halos of buddha images. Here, the central figures were predominantly buddhas, forming a relatively complete developmental sequence, while lotus-born beings and celestial beings appeared only in small quantities and lacked systematic representation.

Notably, the depiction of lotus-born beings holding vines maintains the closest connection to ancient Greco-Roman culture, particularly the Roman Empire. This form of expression is well-documented in the Hexi Corridor, where it evolved in an orderly manner. This suggests that the motif first emerged in the Hexi Corridor before spreading eastward to the Northern Central Plains.

As an imported non-Buddhist motif, the double-scroll central figures traveled long distances to China, were absorbed by Buddhism, and flourished amid the distinct cultural environments of the Hexi Corridor and the Northern Central Plains. From the motif’s adaptation process in Chinese Buddhist art, it is evident that after Buddhism’s introduction to China, it not only integrated extensive local cultural elements but also embraced a wide range of foreign non-Buddhist cultural elements, constantly enriching and evolving itself in the process. Foreign motifs integrated into Buddhist culture were strengthened alongside the Sinicization of Buddhism, forging a mutually reinforcing dynamic between the two. These motifs were eventually incorporated into Chinese culture with a new identity, one that aligns both with Buddhist doctrines and local aesthetic values, and became an organic part of Chinese culture. The interplay between the foreign motif of double-scroll central figures and Chinese Buddhist art, thus, offers a typical case for understanding the dynamics of cultural exchange in ancient Eurasian art history and holds significant value for deepening understanding of the Sinicization of Buddhism.