My Friend the Cross: Cross-Directed Prayer in Seventh-Century Monastic Communities and New Media Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cross-Directed Prayer in the Cells of East Syrian Monastics

Dadishoʿ went on to prescribe an alternating succession of psalmody and personal prayers addressed to Christ, performed while standing in the middle of the cell facing the cross. Reflecting on his own experience of cross-directed prayer, Dadishoʿ noted that he knew some monks who tied a string between their big toes to maintain a vigilant posture before the cross throughout the night office (On Stillness 5.10–11, ed. del Río Sánchez 2001, p. 112).Get up at once, with earnest diligence, and kneel before the cross, and pray the ‘Our father who art in heaven.’ Then rise to your feet, and embrace and kiss the cross with passion and love. And while kissing, speak thus: ‘Glory to you, O our Lord Jesus Christ, son of God, who was crucified for us!’(On Stillness 5.10, ed. del Río Sánchez 2001, p. 112)

3. Discussion: Cross-Directed Prayer through the Lens of New Media Studies

3.1. Cross-Directed Prayer and Monastic Sociality

3.2. Cross-Directed Prayer and Monastic Spirituality

And when [Gewargis] saw the wood on which he would be crucified, he was in great haste and agitation. And with joy and gladness beyond compare, he approached and kissed the wood, and he readily embraced it. Then, turning his face to the east and stretching out his hands to heaven, he spoke in a clear voice before the whole great crowd that was assembled there: “I confess you, Christ our Lord, the true hope of Christians…”(Life of Gewargis, ed. Bedjan 1895, pp. 536–37)

4. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Shubḥalmaran 5.9.3 (ed. Lane 2004, p. 161). Here and following, translations are my own unless otherwise noted. |

| 2 | Although there is as yet no survey of cross imagery in Mesopotamia, several important studies of crosses from particular sites have been published (Okada 1990; al-Kaʿbi 2014; Ali Muhamad Amen and Desreumaux 2018; Lic 2017, 2023). |

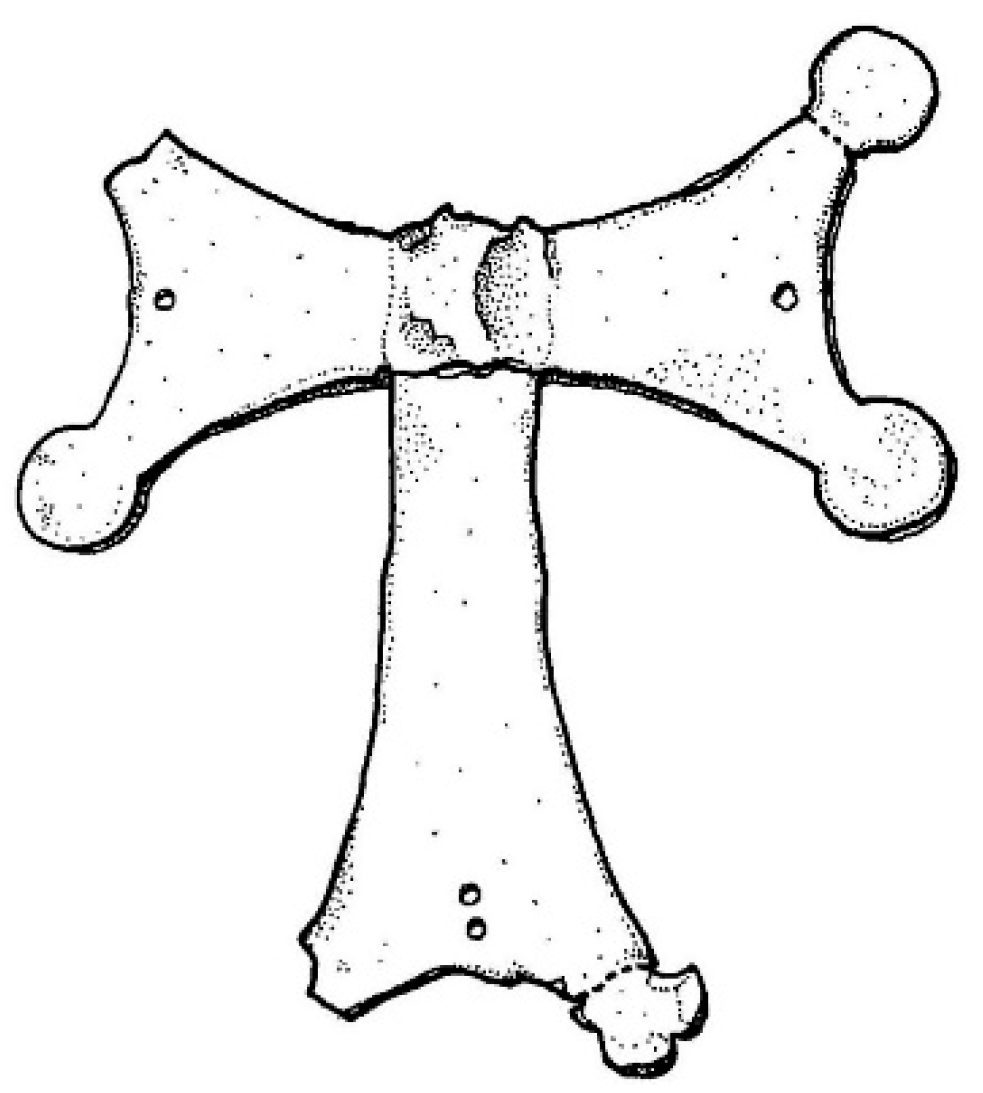

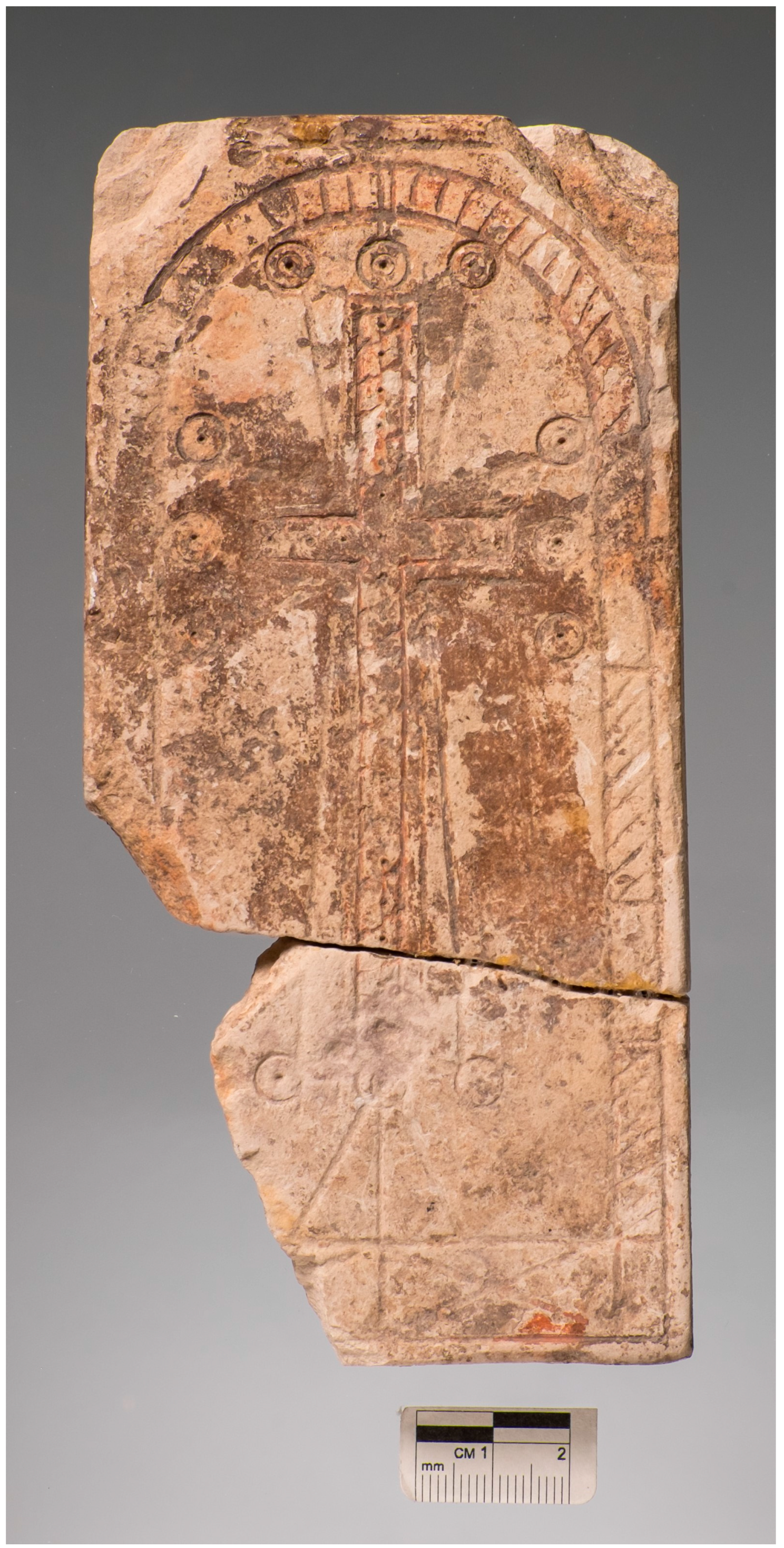

| 3 | E.g., Isaac of Nineveh, First Part (ed. Bedjan 1909, p. 58); idem, Second Part 6.4 (ed. Brock 1995, 17 [text]). |

| 4 | Robert Taft provides an overview of the East Syrian daily office (Taft 1986, pp. 225–37). |

| 5 | Shubḥalmaran 5.4.1 (ed. Lane 2004, p. 154); Dadishoʿ of Qatar, On Stillness 1.15 (ed. del Río Sánchez 2001, p. 55). Gabriel of Qatar, writing in the early seventh century, speaks of solitaries emerging from their cells on Sunday to “mingle with the coenobites and stand together before Christ in the service” (Commentary on the Liturgy 5.5 [unpublished; MS British Library Or. 3336, f. 219b]). |

| 6 | The commentary, consisting of five mēmrē, or treatises, exists entire in a single manuscript, British Library Or. 3336. Portions dealing with the eucharistic liturgy (Mēmrā 5.2) and the daily office of morning prayer (Mēmrā 2) have been published, respectively, by Sebastian Brock and Alex C. J. Neroth van Vogelpoel (Brock 2009; Neroth van Vogelpoel 2018). |

| 7 | Gabriel of Qatar, Commentary on the Liturgy 2.17 (ed. Neroth van Vogelpoel 2018, pp. 370–72). Gabriel refers here to the daily psalmody of both the “lesser monasteries” and the “great and ancient monasteries”; the latter phrase, as Gabriel elsewhere specifies (ibid. 2.13, ed. Neroth van Vogelpoel 2018, p. 306), includes the monasteries of Mount Izla and of Rabban Shabur, with which Isaac of Nineveh and Dadishoʿ of Qatar were later associated. |

| 8 | The estimate of four hours is based on the amount of time necessary to recite the psalms in English (approximately 46,000 words) at an average speed of 183 words per minute (Brysbaert 2019). It should be stressed that the time of four hours is only a rough approximation; while Brisbaert concludes that English reading rates predict reading rates in other languages relatively well at the level of wordcount, this conclusion has not been tested with respect to Syriac. |

| 9 | For the allowance that some solitaries might shorten their daily service due to weakness, see Dadishoʿ of Qatar, On Stillness 1.13 (ed. del Río Sánchez 2001, p. 54). Dadishoʿ’s contemporary Shemʿon d-Taybuteh, while strictly exhorting his readers to observe the regular canonical hours, further advised them to remain at prayer in the cell between the hours of morning prayer (ṣaprā) and the third hour: On the Cell 10–11 (unedited; tr. Louf 2002, p. 39). |

| 10 | For example, a sixth-century East Syrian commentary on the eucharist mentions a wooden cross above the altar: Pseudo-Narsai, Homily 17 (ed. Mingana 1905, p. 281). Gabriel of Qatar describes the movement of a cross (which he identifies as a stand-in for the body of Christ) between the altar and the bema, as well as the presence of a cross on the altar: Commentary on the Liturgy 5.2.8–45 (ed. Brock 2009, pp. 224–30). |

| 11 | E.g., Barḥadbshabba, Church History 32 (ed. Nau 1913, pp. 624–25); Shubḥalmaran 5.9.3–6 (ed. Lane 2004, pp. 160–62); Babai the Great, Useful Counsels on the Ascetic Life 3, in MS Vatican Sir. 592, f. 22r (tr. Chediath 2001, p. 57); Dadishoʿ of Qatar, On Stillness 5.10–14 (ed. del Río Sánchez 2001, pp. 112–14); Shemʿon d-Ṭaybutheh, On the Cell 11 (tr. Louf 2002, p. 40); Yawsep Ḥazzaya, On the Three Stages of Monastic Life 76, 81, and 85 (ed. Harb and Graffin 1992, pp. 348, 352, and 358). |

| 12 | E.g., Dadishoʿ of Qatar, On Stillness 5.10 (ed. del Río Sánchez 2001, p. 112); and Yawsep Ḥazzaya, On the Three Stages of Monastic Life 32 (ed. Harb and Graffin 1992, p. 310). |

| 13 | Isaac of Nineveh, Second Part 11.12 (ed. Brock 1995, pp. 46 [text], 56 [tr., modified]). On this passage see also the comments of Erica Hunter (Hunter 2020, pp. 318–20). |

| 14 | The excavations were published by David Talbot Rice (Rice 1932a, p. 265; 1932b, p. 280, pl. 2; 1934, p. 4, Figures 4–5). More recent scholarship has discussed these results against their local context (Simpson 2018; Hunter 2008; Müller-Wiener and Siegel 2018). |

| 15 | Cf. the descriptions in Shubḥalmaran 5.4.1 (ed. Lane 2004, p. 154); Isaac of Nineveh, First Part (ed. Bedjan 1909, p. 407); and Dadishoʿ of Qatar, On Stillness 5.6 (ed. del Río Sánchez 2001, p. 92). |

| 16 | St John Simpson has collected much of the published evidence from Mesopotamia and the Gulf, as well as some examples of clay plaque crosses from Central Asia that can also be ascribed to Church of the East contexts (Simpson 2018, pp. 14–17). In Mesopotamia, such crosses continue to be found, e.g., in recent excavations at Ḥīrtā (Müller-Wiener et al. 2015, Figure 3; Salman et al. 2023, Figure 13c). The most significant site-specific, published collections from Mesopotamia are from Ḥīrtā and Bazyan (Okada 1990; al-Kaʿbi 2014; Ali Muhamad Amen and Desreumaux 2018). |

| 17 | Crosses at Ḥīrtā were found near walls (Okada 1990, p. 109; al-Kaʿbi 2014, p. 91) and on the floors of excavated structures (Martina Müller-Wiener, personal communication, 25 September 2023, concerning a cross recently excavated at Ḥīrtā). Already in 1932, Rice noted that the plaques he found at Ḥīrtā must have been portable because of their rounded edges (Rice 1932b, p. 282). |

| 18 | The authors identify the site, whose origin they date to the sixth or seventh century, as a monastery that was also open to lay visitation. |

| 19 | The designation of the plaque crosses as “icons” goes back to Rice (1932b, p. 282), and has been repeated by subsequent scholars (e.g., Okada 1990, p. 109; Simpson 2018, p. 17). |

| 20 | Although no plaque crosses have been recovered from Seleucia-Ctesiphon, a small stucco cross was discovered attached to a wall in the suburbs of Ctesiphon (Kröger 1982, pl. 10). The author of the story about the founding of the School seems to have had a larger cross in mind, perhaps on the order of those found in a monastic church at Failaka, dating probably to the eighth century, where excavators unearthed two stucco relief crosses that measured (not including their frames) 60 and 80 centimeters in height (Bernard et al. 1991, p. 160; Lic 2017, pp. 155–56). |

| 21 | On the School’s influence, see the comments of Adam Becker (Becker 2006, pp. 158–59). Philip Wood dates the account of the School’s founding to the late sixth century on the basis of its apparent attempt to glorify the School of Seleucia through a suitable founding narrative (Wood 2013, p. 109). In any case, the story almost certainly predates the end of the School of Seleucia in the early eighth century, when the catholicos moved to the new capital in Bagdad. |

| 22 | The relic-like treatment of the cross at the School of Seleucia may be compared with that of the “true cross”, captured by a Sasanian army and brought to Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 615 CE, where it became a source of cross relics for monastic leaders in Mesopotamia: Chronicle of Khuzestan 24–5 (ed. al-Kaʿbi 2016, pp. 47–53). |

| 23 | Quoted in an interview about her monograph, Reclaiming Conversation (Suttie 2015). |

| 24 | Abraham Zabaya, Life of Rabban Bar ʿEdta (ed. Budge 1902, vol. 1, pp. 189–92). Abraham’s text is based on an earlier Life by Mar John the Persian, a disciple of Rabban Bar ʿEdta. |

| 25 | The authors adapted the “Trust in Close Relationships Scale” from an earlier study of human-to-human relationships (Rempel et al. 1985). Some questions from the original survey were removed, including the entirety of the “faith” section of the survey. For example, the statement “When I share my problems with my mobile, I know it will respond in a loving way even before I say anything” was deemed unsuitable for human-phone relationships because “a smartphone is not a responsive recipient of trust in a way known from human-human interactions” (Carolus et al. 2019, p. 922). While this is in some ways true, it is also probable that the participants of the study would have found such questions more meaningful if the authors had replaced “my mobile” with the name of a popular virtual personal assistant such as “Siri”. |

| 26 | Cf., e.g., Shubḥalmaran 5.1.2 and 5.7 (ed. Lane 2004, pp. 152 and 157), where new monastics are instructed to place their possessions before either the superior of the community or “the cross” (if the community lacked a superior) in order to obtain permission to continuing owning them within the community. Subsequently they ought to do the same with any handiwork they produced as members of the community. Shubḥalmaran seems to have in mind here a cross set up in a communal space, perhaps the church, though this is not explicit. |

| 27 | Abraham Zabaya, Life of Rabban Bar ʿEdta (ed. Budge 1902, vol. 1, p. 192); Dadishoʿ of Qatar, On Stillness 5.6 (ed. del Río Sánchez 2001, p. 111); John of Ephesus, Lives of the Eastern Saints 6 (ed. Brooks 1923, pp. 114–15). |

| 28 | Descriptive overviews of the Replika application are given in recent reporting (Murphy and Templin 2019; Bote 2023). As of March 2024, “over 10 million people have joined Replika” according to the application’s website, https://replika.com/ (accessed on 20 March 2024). |

| 29 | Christelle Jullien provides a list of crucifixions recorded in the Persian Martyr Acts (Jullien 2004, p. 260). |

| 30 | Gerrit Reinink sketches the wider ecclesiastical background of Babai’s Life (Reinink 1999). |

| 31 | Earlier in the Life, Gewargis engages in a debate with a Zoroastrian official in which he explicitly states that “we [Christians] worship the cross” (Bedjan 1895, p. 528). For Babai’s own advice concerning cross-directed prayer, see Babai the Great, Useful Counsels on the Ascetic Life 3 (Ms. Vat. Sir. 592, f. 22r). |

| 32 | For the early publicity around the iPhone discussed in this paragraph, see the study of Heidi A. Campbell and Antonio C. La Pastina (Campbell and La Pastina 2010). |

References

- al-Kaʿbi, Nasir. 2014. A New Repertoire of Crosses from the Ancient Site of Ḥira, Iraq. Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies 14: 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al-Kaʿbi, Nasir. 2016. A Short Chronicle on the End of the Sasanian Empire and Early Islam: 590–660 A.D. Piscataway: Gorgias. [Google Scholar]

- Alfeyev, Hilarion. 2000. The Spiritual World of Isaac the Syrian. Kalamazoo: Cistercian. [Google Scholar]

- Ali Muhamad Amen, Narmen, and Alain Desreumaux. 2018. Les décors des croix portatives de Bazyan. In Études Mésopotamiennes—Mesopotamian Studies N°1. Edited by Narmen Ali Muhamad Amen, Lionel Marti, Olivier Rouault and Aline Tenu. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 135–50. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, Narmin A., Simon Brelaud, Vincent Déroche, and Justine Gaborit. 2023. The Fort and the Church of Bāzyān, Latest Discoveries and New Hypotheses. In Christianity in Iraq at the Turn of Islam: History and Archaeology. Edited by Julie Bonnéric, Narmin A. Amin and Barbara Couturaud. Beirut: Presses de l’Ifpo, pp. 121–41. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Adam. 2006. Fear of God and the Beginning of Wisdom: The School of Nisibis and Christian Scholastic Culture in Late Antique Mesopotamia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bedjan, Paul. 1895. Histoire de Mar-Jabalaha, de Trois Autres Patriarques, d’un Prêtre et de Deux Laïques, Nestoriens. Paris: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Bedjan, Paul. 1909. Mar Isaacus Ninivita: De Perfectione Religiosa. Paris: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Behr, John. 2015. St Isaac of Nineveh on the Cross of Christ. In Saint Isaac the Syrian and His Spiritual Legacy. Yonkers: St Vladimir’s Seminary, pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, Vincent, Olivier Callot, and Jean-François Salles. 1991. L’église d’al-Qousour Failaka, État de Koweit: Rapport préliminaire sur une première campagne de fouilles, 1989. Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 2: 145–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beulay, Robert. 1978. La Collection des Lettres de Jean de Dalyatha. Patrologia Orientalis 39: 257–538. [Google Scholar]

- Bitton-Ashkelony, Brouria. 2019. The Ladder of Prayer and the Ship of Stirrings: The Praying Self in Late Antique East Syrian Christianity. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Bolman, Elizabeth. 2007. Depicting the kingdom of heaven: Paintings and monastic practice in early Byzantine Egypt. In Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700. Edited by Roger S. Bagnall. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 408–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bote, Joshua. 2023. Replika Wanted to End Loneliness with a Lurid AI Bot. Then Its Users Revolted. SFGate, April 27. Available online: https://www.sfgate.com/tech/article/replika-san-francisco-ai-chatbot-17915543.php (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Brelaud, Simon. 2022. L’Arbre de vie et la Croix syro-orientale. Paper presented at the 13th Symposium Syriacum, France, Paris, July 4. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Sebastian. 1995. Isaac of Nineveh (Isaac the Syrian). ‘The Second Part’, Chapters IV-XLI. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium, vols. 554–555. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Sebastian. 1999–2000. Syriac Writers from Beth Qaṭraye. ARAM 11–12: 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Sebastian. 2009. Gabriel of Qatar’s Commentary on the Liturgy. Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 6: 197–248. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, E. W. 1923. John of Ephesus: Lives of the Eastern Saints (I). Patrologia Orientalis 17: 1–307. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant Gibson, Kelli. 2020. An Early Syriac Apologia Crucis: Mēmrā 54 “On the Finding of the Holy Cross”. In Narsai: Rethinking his Work and his World. Edited by Aaron M. Butts, Kristian S. Heal and Robert A. Kitchen. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 117–32. [Google Scholar]

- Brysbaert, Marc. 2019. How many words do we read per minute? A review and meta-analysis of reading rate. Journal of Memory and Language 109: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Budge, Ernest A. Wallis. 1902. The Histories of Rabban Hôrmîzd the Persian and Rabban Bar-ʿIdtâ. 2 vols. London: Luzac. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi A., and Antonio C. La Pastina. 2010. How the iPhone became divine: New media, religion and the intertextual circulation of meaning. New Media and Society 12: 1191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolus, Astrid, Jens F. Binder, Ricardo Muench, Catharina Schmidt, Florian Schneider, and Sarah L. Buglass. 2019. Smartphones as digital companions: Characterizing the relationship between users and their phones. New Media and Society 21: 914–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, Laura. 2023. Daily Time Spent Online via Mobile for Users Worldwide 2022, by Region. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1288783/daily-time-spent-online-via-mobile/ (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Chediath, Geevarghese. 2001. Mar Babai the Great—Some Useful Counsels on the Ascetical Life. Kerala: St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- del Río Sánchez, Francisco. 2001. Los Cinco Tratados sobre la Quietud (šelyā) de Dāḏīšōʿ Qaṭrāyā. Barcelona: Editorial AUSA. [Google Scholar]

- Draguet, René. 1972. Le commentaire du livre d’Abba Isaïe (logoi I-XV) par Dadišo Qaṭraya (VII s.). Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 326. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Fullwood, Chris, Sally Quinn, Linda K. Kaye, and Charlotte Redding. 2017. My virtual friend: A qualitative analysis of the attitudes and experiences of Smartphone users: Implications for Smartphone attachment. Computers in Human Behavior 75: 347–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, Paul, and François Graffin. 1992. Lettre sur les trois étapes de la vie monastique. Patrologia Orientalis 45: 255–442. [Google Scholar]

- Harrak, Amir. 2010. Syriac and Garshuni Inscriptions of Iraq. Paris: Boccard. [Google Scholar]

- Huet, Ellen. 2023. What Happens When Sexting Chatbots Dump Their Human Lovers. Bloomberg Businessweek, March 22. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-03-22/replika-ai-causes-reddit-panic-after-chatbots-shift-from-sex (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Hunter, Erica. 2008. The Christian Matrix of al-Hira. Cahiers de Studia Iranica 36: 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, Erica. 2020. The Veneration of the Cross in the East Syrian Tradition. ARAM 32: 309–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jullien, Christelle. 2004. Peines et supplices dans les Actes des Martyrs Persans et droit sassanide: Nouvelles prospections. Studia Iranica 33: 243–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, Cyril. 2004. Symbols of the Cross in the Writings of the Early Syriac Fathers. Piscataway: Gorgias Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kerai, Alex. 2023. Cell Phone Usage Statistics: Mornings are for Notifications. Reviews.org, July 21. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230729001654/https://www.reviews.org/mobile/cell-phone-addiction/ (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Keser Kayaalp, Elif. 2021. Church Architecture of Late Antique Northern Mesopotamia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kröger, Jens. 1982. Sasanidischer Stuckdekor. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz, Scott R. 2007. He Has Risen. Player vs. Player, January 9. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20080110004652/http://www.pvponline.com:80/2007/01/09/he-has-risen/ (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Kushlev, Kostadin, and Jason D. E. Proulx. 2016. The Social Costs of Ubiquitous Information: Consuming Information on Mobile Phones Is Associated with Lower Trust. PLoS ONE 11: e0162130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, David. 2004. Šubḥalmaran: The Book of Gifts. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 612. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Langfeldt, John A. 1994. Recently discovered early Christian monuments in Northeastern Arabia. Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 5: 32–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lic, Agnieszka. 2017. Chronology of Stucco Production in the Gulf and southern Mesopotamia in the early Islamic period. Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 47: 151–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lic, Agnieszka. 2023. The Beribboned Cross in Christian Art of the Early Islamic Period in Iraq and the Gulf. In Christianity in Iraq at the Turn of Islam: History and Archaeology. Edited by Julie Bonnéric, Narmin A. Amin and Barbara Couturaud. Beirut: Presses de l’Ifpo, pp. 291–304. [Google Scholar]

- Louf, André. 2002. Discours sur la cellule de Mar Syméon de Taibouteh. Collectanea Cisterciensia 64: 34–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, Angelo. 1838. Qānunā d-Ṯʾbeylālē. In Scriptorum Veterum Nova Collectio 10.2. Rome: Typis Collegii Urbani, pp. 317–66. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit. 2013. Material Mediations and Religious Practices of World-Making. In Religion Across Media: From Early Antiquity to Late Modernity. Edited by Knut Lundby. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit. 2014. An Author Meets her Critics: Around Birgit Meyer’s ‘Mediation and the Genesis of Presence: Toward a Material Approach to Religion’. Religion and Society: Advances in Research 5: 205–54. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit. 2015. Picturing the Invisible: Visual Culture and the Study of Religion. Method and Theory in the Study of Religion 27: 333–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Birgit. 2020. Religion as Mediation. Entangled Religions 11: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingana, Alphonse. 1905. Narsai Doctoris Syri Homiliae et Carmina. Mosul: Mausilii, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Mike, and Jacob Templin. 2019. This app is trying to replicate you. Quartz, August 29. Available online: https://qz.com/1698337/replika-this-app-is-trying-to-replicate-you (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Müller-Wiener, Martina, and Ulrike Siegel. 2018. The Pre-Islamic and Early Islamic City of al-Ḥīra: First Results of the Archaeological Survey 2015. In Proceedings of the 10th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Edited by Vera Müller and Marta Luciani. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 639–52. [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Wiener, Martina, Ulrike Siegel, Martin Gussone, and Ibrahim Salman. 2015. Archaeological Survey of al-Hīra/Iraq: Fieldwork Campaign 2015. Bulletin of the Fondation Max van Berchem 29: 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nau, François. 1913. La seconde partie de l’histoire eccelsiastique de Barḥadbešabba ʿArbaïa et une controverse de Théodore de Mopsueste avec les Macédoniens. Patrologia Orientalis 9: 492–677. [Google Scholar]

- Neroth van Vogelpoel, Alex C. J. 2018. The Commentary of Gabriel of Qatar on the East Syriac Morning Service on Ordinary Days. Piscataway: Gorgias. [Google Scholar]

- Niewöhner, Philipp. 2020. The Significance of the Cross before, during, and after Iconoclasm. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 74: 185–242. [Google Scholar]

- Okada, Yasuyoshi. 1990. Reconsideration of Plaque-Type Crosses from Ain Sha’ia Near Najaf. al-Rāfidān 11: 103–12. [Google Scholar]

- Payão, Rafael. 2007. Jesus-Phone. Blog Rafael Payão: Cybercultura Criatividade, June 29. Available online: https://rafaelpay.typepad.com/rafa/2007/06/jesus-phone.html (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Payne, Richard. 2015. A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Payne Smith, J. 1903. A Compendious Syriac Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Payngot, Charles. 1981. The Cross in the Chaldean Tradition. Christian Orient 2: 106–18. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, Daniel. 1994. Nestorian Crosses from Jabal Berri. Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 5: 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassart-Debergh, Marguerite. 1988. Quelques croix kelliotes. In Nubia et Oriens Christianus. Edited by Piotr O. Scholz and Reinhard Stempel. Cologne: Dinter, pp. 373–85. [Google Scholar]

- Reinink, Gerrit. 1999. Babai the Great’s Life of George and the Propagation of Doctrine in the Late Sasanian Empire. In Portraits of Spiritual Authority: Religious Power in Early Christianity, Byzantium and the Christian Orient. Edited by Jan Willem Drijvers and John W. Watt. Leiden: Brill, pp. 171–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rempel, John K., John G. Holmes, and Mark P. Zanna. 1985. Trust in Close Relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49: 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, David Talbot. 1932a. Hira. Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society 19: 254–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, David Talbot. 1932b. The Oxford Excavations at Hira, 1931. Antiquity 6: 276–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, David Talbot. 1934. The Oxford Excavations at Ḥīra. Ars Islamica 1: 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Brett. 2014. The Marriage of Religion and Technology: Reading Apple’s Allegorical Advertising. Second Nature, January 27. Available online: https://secondnaturejournal.com/the-marriage-of-religion-and-technology-reading-apples-allegorical-advertising/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Salman, Ibrahim, Martin Gussone, Catherine Hof, Martina Müller-Wiener, Agnes Schneider, Burkart Ullrich, and Mustafa Ahmad. 2023. Al-Hira, Irak: Feldforschungen. Prospektionen und Ausgrabungen. e-Forschungsberichte des DAI 1: 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scher, Addaï. 1911. Histoire Nestorienne (Chronique de Séert): Seconde partie (I). Patrologia Orientalis 7: 95–203. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, St John. 2018. Christians on Iraq’s Desert Frontier. al-Rāfidān 29: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Skjuve, Marita, Asbjørn Følstad, Knut Inge Fostervold, and Petter Bae Brandtzaeg. 2021. My Chatbot Companion—a Study of Human-Chatbot Relationships. International Journal of Human—Computer Studies 149: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoloff, Michael. 2009. A Syriac Lexicon. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Spalding-Stracey, Gillian. 2020. The Cross in the Visual Culture of Late Antique Egypt. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Suttie, Jill. 2015. How Smartphones Are Killing Conversation: A Q&A with MIT professor Sherry Turkle about her new book, Reclaiming Conversation. Greater Good Magazine, December 7. Available online: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_smartphones_are_killing_conversation (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Taft, Robert. 1986. The Liturgy of the Hours East and West. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ta, Vivian, Caroline Griffith, Carolynn Boatfield, Xinyu Wang, Maria Civitello, Haley Bader, Esther DeCero, and Alexia Loggarakis. 2020. User Experiences of Social Support from Companion Chatbots in Everyday Contexts: Thematic Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22: e16235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, Bill, Alyson Faires, Maija Robbins, and Eric Rollins. 2014. The Mere Presence of a Cell Phone May Be Distracting: Implications for Attention and Task Performance. Social Psychology 45: 479–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieszen, Charles. 2017. Cross Veneration in the Medieval Islamic World. London: Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Trothen, Tracy J. 2022. Replika: Spiritual Enhancement Technology? Religions 13: 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, J. 1943. Un traité nestorienne du culte de la croix. Le Muséon 56: 115–27. [Google Scholar]

- Whitcomb, Donald S. 1985. Before the Roses and Nightingales: Excavations at Qasr-i Abu Nasr, Old Shiraz. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A. V. 1996. Zoroastrians and Christians in Sasanian Iran. Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 78: 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Philip. 2013. The Chronicle of Seert: Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yousif, Pierre. 1976. Le symbolisme de la croix dans la nature chez saint Éphrem de Nisibe. In Symposium Syriacum. Rome: Pontificium Institutem Orientalium Studiorum, pp. 207–28. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, D. My Friend the Cross: Cross-Directed Prayer in Seventh-Century Monastic Communities and New Media Studies. Religions 2024, 15, 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060708

An D. My Friend the Cross: Cross-Directed Prayer in Seventh-Century Monastic Communities and New Media Studies. Religions. 2024; 15(6):708. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060708

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Daniel. 2024. "My Friend the Cross: Cross-Directed Prayer in Seventh-Century Monastic Communities and New Media Studies" Religions 15, no. 6: 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060708

APA StyleAn, D. (2024). My Friend the Cross: Cross-Directed Prayer in Seventh-Century Monastic Communities and New Media Studies. Religions, 15(6), 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060708