Abstract

Religion in Europe has been undergoing two fundamental changes in the past four decades. As a side effect of secularization, religious fields have been pluralizing. On the other hand, religions themselves have taken a qualitative shift towards lived, material characteristics. Focusing exclusively on the diversification of European religious fields, we are interested in the concept of religious literacy as a tool for competent engagement in contemporary religious plural societies. To better understand the role of public media in fostering religious literacy, we offer an analysis of the public broadcaster’s coverage of smaller religious communities in Slovenia. Focusing particularly on Muslims as the largest religious minority in Slovenia, we provide an analysis of 245 episodes, consisting of 540 items, in the 2015–2020 period. We show that the coverage given to smaller religious communities is unevenly spread amongst the communities, with disproportional airtime given to Christian churches and communities. Furthermore, we pinpoint the key qualitative difference in portrayals of Slovenian Muslims and non-Catholic Christians, explaining how the process of racialized Islamophobia may continue beyond explicit hate speech. In conclusion we set out limitations of our study and provide guidelines for future research.

Keywords:

Muslims; Slovenia; religion; media; religious literacy; media representation; Islamophobia 1. Introduction

Although secularization theorists insisted otherwise (P. Berger 1980; Casanova 1994; Bruce 2011), the importance of religion in the contemporary world has not substantially declined, nor has its influence softened. Regardless of the rising popularity of “nones” (Woodhead 2017) or irreligion (Smrke 2017), what the last century has brought about is a key change in what and where religion is (P. Berger 2014). Focusing on Europe1 in particular, these changes have encompassed two key transformations, each fundamentally shaping religion as a social phenomenon: firstly, there is a quantitative dimension—rather than a wholesale decline of religion, we are witnessing an immense pluralization of religious fields in Europe, accompanied by the loosening of religious monopolies of traditional Christian churches (Kippenberg 2008; Müller et al. 2016; Beyer 2011; Tietze 2020). This development marks the onset of a post-secular society brought about by religious pluralism, which we understand in a descriptive sense as the sociological empirical fact of increased religious diversity (Giordan 2014). The second distinguishing transformation is the fundamentally qualitative change of religion, which can be characterized as a spiritual turn (Houtman and Aupers 2007) or spiritual revolution (Heelas 2005). As a phenomenon, religion is shifting towards a particularly lived-type religion (Ammerman 2021), which is marked by the increasingly popular self-identification of “spiritual but not religious” (Ammerman 2013; Marshall and Olson 2018).

Both the qualitative and the quantitative changes present important challenges to the study of religious phenomena, as well as to the way society deals with religious change—be it its qualitative or quantitative dimensions. Though it does not concern itself with it straight-on, our study’s empirical background is primarily informed by the empirical fact of the pluralization of the religious fields in Europe. Namely, due to religious diversification, we are now witnessing what Peter Berger famously labeled double pluralism (P. Berger 2014, p. 92), that is, the relationship amongst many religious communities on the one hand and the relationship between a diverse religious field and the secular state on the other. It is this second half of the double pluralism that we are interested in. Namely, we are interested in the implications that religious diversification has for state governance of religious communities (Martínez-Ariño 2019)2, meaning that we are less interested in the empirical fact of religious diversity in itself and more so in religion as a social fact of state governance. In most cases, European secularist regimes (Taylor 2009), that is, the ways in which secular states govern religious affairs, have been based on religiously monolithic societies. Thus, contemporary religious diversity necessitates a significant societal transformation, requiring states to adapt their approach to upholding a secular system while also ensuring the implementation of mechanisms that facilitate peaceful coexistence among different religious plausibility structures and practices. Multiple studies have shown that one such mechanism is the fostering of potent religious literacy (Dinham and Francis 2015a; Littau 2015; Sakaranaho 2020; Mason 2021; Walker et al. 2021), a concept central to our analytical undertaking. Religiously literate individuals—whatever their (non)religious background may be—make for competent citizens of religiously diverse societies. Consequently, it is imperative for governments of religiously diverse societies to develop religious literacy, which facilitates adept navigation of social interactions. The state has two main mechanisms for fostering religious literacy, that is, of teaching its citizens about religious diversity: (public) education and (public) media. Our study focuses on media as a means of fostering religious literacy.

The question of religious literacy—and how it is fostered in religiously plural societies—informs our present study. In this light, our study seeks to address two interconnected questions: first, to what extend does Slovenia’s primary public broadcaster provide coverage of non-Christian religious communities? Although the analysis will encompass a range of religious communities, our primary focus is the Muslim community. And secondly, what is characteristic of the portrayal of Slovenian Muslim communities? Our main hypothesis is that the public religious broadcasting service under consideration underrepresents Muslim communities in its coverage, producing implicit Islamophobia. To effectively test our hypothesis, answer the research question, and present our findings, the paper is structured as follows: initially, we will provide a brief summary of religious literacy as a concept, pinpointing those empirical studies that underscore its importance in fostering religious solidarity and tackling religious discrimination; secondly, we will examine the characteristics of Slovenia’s post-socialist religious landscape as it has been shaped during the first 30 years of independence (1991–2021). Next, we will provide a concise overview of RTV SLO, the main public broadcaster in Slovenia, which we have chosen as the key media institution able to foster religious literacy and examine how the television program in question, Duhovni utrip, aligns with RTV SLO’s content and journalistic structure. Subsequently, we will outline the protocols of our inquiry prior to proceeding with the two-step analysis. The first stage will address the issue of proportionality in the number of items and airtime provided to non-Christian religious communities, particularly to Muslim communities living in Slovenia; the second will focus on the substance of those programs, namely the content of items covering the Muslim community in Slovenia. Before making our final remarks, we will go over our findings in-depth, emphasizing the need to cultivate religious literacy. This will be performed by bringing our study to the conversation with the RELIGARE project, which took a closer look at how European public broadcasters treat the coverage of religious communities—particularly religious minorities.

2. The Promise of Religious Literacy

Contemporary societies are distinctively marked by religious pluralism, which calls for new ways of ensuring peaceful coexistence between many actors within the framework of double pluralism (P. Berger 2014, p. 92). Additionally, religious diversification has been accompanied by ever-increasing religious illiteracy, as the importance of religion in the public sphere remains unrecognized (Sakaranaho et al. 2020, p. 1). Nevertheless, religion has become a pressing matter in all fields of public life, which raises the fundamental question: how to govern religious diversity? One answer that has gained a fraction in recent years is religious literacy, which has become viewed as a prerequisite for the successful governance of religious diversity (Sakaranaho et al. 2020, p. 2). Religious diversity, namely, points to two main shortcomings of religious illiteracy: either the inability to recognize developments within the religious field as relevant or the production of religious stereotypes, which may lead to discrimination (Ibid.). As such, religious illiteracy has been recognized as a “social evil” (Meloni 2019, p. 6). In this light, studies have pointed out that religious bullying and discrimination occur when “the general public is illiterate about both religion and law”, which is why “widespread [religious] illiteracy can lead to the breakdown of social systems […] that would otherwise protect the most vulnerable among us” (Walker et al. 2021, p. 4). Therefore, religious illiteracy is directly linked to discrimination. In addition, previous studies have shown that religious illiteracy is a “sociologically documented fact” and a “historical outcome” of a particular development of the relationship between the secular and religious (Meloni 2019, p. 4; see also Giorda 2019).

At its core, then, religious literacy entails a sensitivity to diverse religious matters. Multiple studies argue that religious literacy should be recognized as a fundamental civic competence, which would “combat prejudice, and negative stereotypes of religious groups […] and build mutual respect within multifaith societies” (Halafoff et al. 2019, p. 199). However, this does not mean that defining religious literacy is a simple matter. Many definitions of religious literacy exist beyond its fundamental assumption (Davie and Dinham 2019; Seiple and Hoover 2022). Not only are there different definitions, but there are also different vantage points for approaching religious literacy (Dinham and Jones 2010, p. 6). Stephen Prothero laid the groundwork for religious literacy studies in his 2007 work Religious Literacy: What Every American needs to Know—And Doesn’t. In it, he wrote of religious literacy as “the ability to understand the religious terms, symbols, images, beliefs, practices, scriptures, heroes, themes, and stories that are employed in American public life” (Prothero 2007, p. 17), that is, “religious literacy, in short, is both doctrinal and narrative” (Ibid., p. 18). The same year, however, Diane Moore provided her celebrated definition of religious literacy in Overcoming Religious Illiteracy: A Cultural Studies Approach to the study of Religion in Secondary Education (Moore 2007). According to Moore, religious literacy includes “the ability to discern and analyze the fundamental intersections of religion and social/political/cultural life through multiple lenses”, which means that a religiously literate person will possess “a basic understanding of the history, central texts, beliefs, practices and contemporary manifestations of several of the world’s religious traditions as the arose out of and continue to be shaped by particular social, historical and cultural contexts” as well as “the ability to discern and explore the religious dimensions of political, social and cultural expressions across time and place” (Ibid., pp. 55–57). Similarly, Adam Dinham and Matthew Francis argue that an essential part of religious literacy consists of the “engagement in the detail and reality of at least some religion and belief, and an ability to ask appropriate questions with confidence about others” (Dinham and Francis 2015b, p. 14). Moore’s definition was later adopted by the American Academy of religion (AAR). In 2010, the AAR published its definition of religious literacy as the ability to “discern accurate and credible knowledge about diverse religious traditions and expressions; recognize the internal diversity within religious traditions; […] distinguish confessional or prescriptive statements made by religious from descriptive or analytical statements” (AAR 2024). It is worth noting that AAR’s definition is primarily aimed at educators.

Definitions of religious literacy in practice (Marcus and Ralph 2021, pp. 26–30) and academia (Dinham and Jones 2010, pp. 4–6) still vary greatly. Nevertheless, ever-since Prothero’s discussion in 2007, religious literacy has been increasingly recognized as a “civic endeavor” (Dinham and Jones 2010, p. 6), whose aim is “to inform intelligent, thoughtful and rooted approaches to religious faith that countervail unhelpful knee-jerk reactions based on fear and stereotype” (Ibid., emphasis added). That is, religious literacy is a civic competence that can enable the formation of a cohesive, religiously diverse society. Dinham and Jones (2010, p. 6) managed to provide a useful consensus of approaches to religious literacy. According to them, religious literacy lies “in having the knowledge and skills to recognize religious faith as a legitimate and important area for public attention” as well as having a “degree of general knowledge about at least some religious traditions, and an awareness of and ability to found out about others”. Finally, the purpose of religious literacy is then to “avoid stereotypes […] In this, it is a civic endeavor […] and seeks to support a strong, cohesive, multi-faith society” (Ibid.). The general approach advocated for by Dinham and Jones (2010) is the one that we find most useful in our study. It ties basic knowledge of religions and their diversity with the explicit aim of limiting the growth of prejudice and discrimination. As a “fundamental civic competency” (Walker et al. 2021, p. 1), religious literacy is needed in religiously plural societies in “virtually every sector of society and governance, domestically and transitionally” (Seiple and Hoover 2022, p. 5), which is why some have extended religious literacy to a cross-cultural competency (Seiple and Hoover 2022, p. 10)3.

Seen as a tool of state governance, religious literacy may be fostered via two main mechanisms: public education and public media.4 Studies have shown that education can be a very important factor in making pupils religiously literate (Bishop and Nash 2007; Enstedt 2022), even though the exact ways of fostering religious literacy through public curriculum are hotly debated (Dinham and Shaw 2017). Hence, there is no clear-cut form of fostering religious literacy in public education—even though the need for it is uniformly recognized within scientific literature (Von Brömssen et al. 2020). Some educators have been arguing that public education may be “our society’s best arena for encouraging religious literacy that is essential to active citizenry” (Rosenblith and Bailey 2007, p. 109), referring to a lack of religious education as a “gross act of miseducation” (Ibid., p. 103). Indeed, a recent study has argued that religious literacy in public education leads to a decrease in stereotypes and discrimination against religious minorities (Halafoff et al. 2019, p. 210). Given the analytical scope of our analysis, it is worth considering the case of Slovenia for a moment. There is a notable absence of secular religious teaching in both primary and secondary schools. As shown by a recent study (Črnič and Pogačnik 2021), Slovenian pupils have very limited access to any official (secular) religious education in Slovenia’s public schools. Therefore, it is crucial to examine the extent to which public media contributes to the development of religious literacy.

However, there is a limited number of studies available which specifically examine the role of public media in promoting religious literacy. Additionally, available studies suggest that news media faces important challenges. For example, a recent study of religious literacy amongst journalism students in the US found that journalism students tended to “score poorly on basic religious knowledge” while also being as religiously illiterate as other non-journalism students (Littau 2015, p. 145). Similarly, Mason has pinpointed the need for religiously literate journalists and news, delineating what counts as religiously literate journalists and news. Amongst the five dimensions of religiously literate news, two are of particular interest to our study. Firstly, a religiously literate news (item) entails going beyond “stereotypes and common parlance, with precise and accurate language” and, secondly, in includes “informational and honed storytelling that expands the public’s understanding about diversity within and among varied manifestations” of religion (Mason 2021, p. 76). Thus, we define a religiously literate TV program as one that conveys accurate knowledge about religions and their inner diversity, which enables countering religious prejudice and stereotyping.

In sum, there is a growing scientific consensus according to which religious literacy represents a vital mechanism in ensuring peaceful cohabitation in religiously (and culturally) diverse societies. Studies have shown that the state can predominantly promote religious literacy through public education, although (public) media play an important role as well. Since a recent study has shown that fostering religious literacy in Slovenia’s public education is nearly non-existent, it is the public broadcasting service that may have greater influence in instilling religious literacy, which could, if performed properly, decrease prejudice and discrimination. Before discussing Slovenia’s public broadcasting, however, we will briefly overview the characteristics of Slovenia’s religious field.

4. Religious (Public) Broadcasting in Slovenia

According to Stig Hajvard, there are three distinct forms of mediated religion, which refer to three ideal types of interactions that emerge when media and religion intersect: religious media, journalism on religion, and banal religion (Hjarvard 2020). The first refers to those attempts of a particular religious community, which “create religious community and identity based on mediated participation” (Ibid., p. 28); the second subjects “religion to the dominant discourses of the political public sphere” (Ibid.), while the latter “constructs religion as a cultural commodity for entertainment and self-development” (Ibid.). In our case, the second kind of mediated religion is crucial, as media functions as a fundamental resource of popular information about religion (Knott et al. 2013).

According to the government website (GOV.SI 2022), there are two Slovenian public service providers when it comes to media and the provision of information: RTV Slovenia (RTV SLO) and the Slovenian Press Agency (STA). While the role of both is described as “the providers and distributors of credible information” (Ibid.), we have focused on the former as it is the larger of the two.13 Although RTV SLO is a public service media provider, it should not be misconstrued as a state television. RTV SLO services are not funded directly from the state budget. Instead, they are funded by a designated tax—licensing fee—that each household must pay in order to access these services.14 RTV SLO originated from TV Slovenia, which was founded in 1957 as a component of the Yugoslav broadcasting network (Volčič and Zajc 2013). TV Slovenia operated as a monopoly in the television provider industry until the country gained independence in 1991. Confronted with significant commercial rivalry15, and in the light of technological advances, RTV SLO currently offers radio, television, and digital services that cover a wide range of issues, including daily and political events, sports, culture, entertainment, and, importantly, religious broadcasting.

Our study defines religious broadcasting as the dissemination of religious material to specific audiences.16 Additionally, our study concentrates solely on public religious broadcasting, that is, the transmission of religious content via public service media. Religious broadcasting can be categorized into two distinct sorts (Jenča et al. 2013, pp. 62–64): live broadcasts of religious ceremonies and programs broadcasting religious life. The first type aims to make “liturgy available for the believers that are unable to attend” (Ibid., p. 62), thus fulfilling the role of enabling the participation of the audience in ceremonies.17 The second type consists of programs—news bulletins and reports—covering religious life in a given religious community. The main public broadcaster in Slovenia, RTV SLO, provides both types of religious broadcasting content—both in terms of radio and television broadcasts.18 We are specifically concentrating on the latter in our study.

Journalists in the religious broadcasting editorial office create four core television programs, three of which are aired on a weekly basis. Firstly, there is Obzorja duha (Spiritual vistas), which officially focuses on covering news and events concerning the Catholic, Evangelical, and Orthodox churches. Secondly, there is Ozare (Greens), a program in which three people discuss a given religious topic. Each of these individuals represents an established religious community, a New Age community, and a non-religious perspective, respectively. Finally, there is Duhovni utrip (Spiritual pulse), a program devoted to covering Slovenia’s smaller religious communities. Given its officially stated aim and our interest in the coverage of minority religions in Slovenia, we have chosen Duhovni utrip as our case study. In addition to these weekly programs, the religious broadcasting editorial office airs a monthly roundtable debate on religious topics, named Sveto in svet (Sacred and the World), as well as occasional live broadcasts of Catholic and Evangelical masses, holiday messages from religious leaders such as bishops and imams, and a festive broadcast from the Vatican.

RTV SLO establishes a yearly plan in December to outline the number and characteristics of each television program produced in the following year. This plan delineates the strategic objectives of every editorial office. For example, the strategic aims of the editorial office for religious broadcasting for 2020 stated that one of the goals was to “assure proportionality” in their coverage of religious communities. The plan provisioned 70% of its airtime to be given to the matters of “the Catholic church and Christian topics”, 10% to the matters of the Evangelic (Lutheran) Church, and 20% to “other religious communities and spiritual topics” (RTV SLO 2019, p. 52).19 Therefore, it can be stated that the public broadcaster in Slovenia follows a proportional model in allocating airtime to religious communities. Whether the proportions mirror the characteristics of Slovenia’s religious field is a different matter, to which we will return later. Moreover, the proportional model is clearly based on what has been labeled church-type religion (Beyer 1994), preferring to focus on organized, institutionalized forms of religion, paying much less attention to contemporary market-form religious communities (Gauthier 2020). Additionally, it is crucial to acknowledge that every yearly plan explicitly mentions that one of the strategic objectives is to promote religious literacy. With regards to Duhovni utrip, the plan states that one of the aims is to “encourage interreligious dialogue” and to produce unbiased content. Duhovni utrip “targets the general public” as a program, which “consists of various items, covering current affairs and important themes in relation to smaller religious communities, registered at the Ministry of Culture” (RTV SLO 2019, p. 53). Annually, there are about 40 episodes of the program, each lasting up to 15 min; however, the duration may vary. In terms of audience, the editorial office for religious broadcasting primarily targets members of religious communities as well as the general public, interested in religious and spiritual matters. Thus, the targeted audience of Duhovni utrip is the general public aged between 25 and 80 (RTV SLO 2022, p. 47). However, data on the actual audience of Duhovni utrip are unavailable.

Before proceeding to our present study, a summary is in order. Since gaining independence, Slovenia’s religious landscape has become significantly more diverse, mostly due to the rise of numerous new religious movements, some of which are not formally recognized as religious communities. The pluralization is closely linked to the erosion of the Catholic monopoly, while it remains the largest religious community in terms of both self-identification and institutional power (Smrke 2016). Conversely, the Muslim population has grown to become the largest religious minority during the 1990s. Given the emergence of these two transformations in the religious field, it is crucial to assess the extent to which the information disseminated by RTV SLO has adjusted to the current religious constellations. Furthermore, it is essential to examine how the public is being informed about matters concerning the predominant non-Christian religious community in Slovenia.

5. Methods

Most studies on Muslim communities in media focus on their representation in various media segments (Kabir 2006; Jaspal and Cinnirella 2010; Kassimeris and Jackson 2011; Ahmed and Matthes 2017; Li and Zhang 2022). While qualitative media representation no doubt informs religious (il)literacy, we chose to focus on the quantitative side of the equation. We purposefully chose the TV program Duhovni utrip as our case study. Focused on covering smaller religious communities in Slovenia, we believe it holds the most potential from the point of view of fostering religious literacy. We selected a duration of six years spanning from 2015 to 2020.20 In our analysis, we have considered all weekly episodes aired in a given year, excluding annual review episodes (broadcasted in December each year) and reruns of episodes, which are usually aired during the weeks of particular national holidays.21 The structure of the television program Duhovni utrip has substantially changed over the six analyzed years, making a uniform analysis somewhat difficult. Amongst the biggest changes is the omission of the introductory item, recorded in a television studio, in which (usually) the editor of the program presented the items that followed within the episode. To maintain a uniform analysis, we have excluded those parts from our analysis within the years 2015–2017, taking a single item as our unit of analysis spanning across the analyzed years. As such, the sample of our study includes 245 episodes, which are composed of 540 items in a combined length of 57:09:3022 (see Table 2). The length and format of items might vary depending on the event covered. Items may include features, stories, or interviews.

Table 2.

Overview of the analyzed sample.

In terms of discrepancies, the year 2020 stands out with the least number of episodes (and items). This can be explained by the shutting down of all non-essential television programs at Slovenia’s public broadcaster during the weeks of the initial lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In our analysis, we have used standardized video analysis24 of television items25 (Graber 1985), based on qualitative coding (Baralt 2011; Adu 2019), as our core methodological principal. First, we segmented each episode into several items (usually three to four items per episode), and second, we qualitatively coded each item, facilitating final categorization. We established three orders of codes, encompassing our coding tree. First-order codes were most general—they helped categorize the dataset into Christian, Non-Christian, and “Other” categories (see Table 3). Then, both Christian and non-Christian items were further divided according to the communities they encompassed. Second-order codes were created according to the list of registered religious communities in Slovenia, with each code representing one such community. In the case of Muslim and Buddhist religious communities, they were coded uniformly, regardless of the specific (registered) religious community items pertained to. In general, coding items pertaining to just one community was a difficult task in some cases, which we expand on below. While first and second-order codes were prepared in advance, third-order codes were added during the analysis itself. On the one hand, they enabled smoother analysis as it became clear that some items cannot simply be coded as pertaining to one religious community. On the other hand, third-order codes enabled the groupings of those smaller religious communities, which did not pass the quantitative threshold of ten items within the analyzed period. Such communities were grouped together and coded as “Other”. Thus, each item was given the most appropriate code and marked for the length of airtime. Subsequently, basic statistical methods were used to determine the ratios of the number of items and the amount of airtime given to each coded category—that is, each religious community. In the second phase of our study, we conducted a brief qualitative examination of the items related to Muslim communities and compared them to those related to smaller Christian communities, specifically Evangelical churches and communities.

Table 3.

Overview of the number of items and airtime according to the Christian/non-Christian divide.

6. Results

During the initial round of study, we classified the objects based on the specific religious community26 the item was dedicated to.27 Initially, we made a distinction between items associated with Christianity and those that were not, and we introduced a category called “Other” to classify items that could not be attributed to any specific religious group—Christian or non-Christian. These items encompass news on religious studies, scientific conferences, presentations of philosophical literature, and other topics related to spirituality, such as death, relationships, and parenting (see Table 3).

During the second phase of analysis, we further differentiated between large Christian topics and churches and minor Christian communities. The first category encompasses the churches that constitute the national Council of Christian Churches, namely the Catholic Church, the Evangelical Church (Lutheran), the Orthodox Church, and the Pentecostal Church. The following are the leading institutionalized Christian churches in Slovenia. Given that the special focus of the TV program is on smaller religious communities, our main emphasis will be on comparing the coverage of minor Christian communities with that of non-Christian communities.28

The second category, minor Christian communities, consists of those items that cover all other Christian churches and communities which do not fall under the national Council of Christian Churches. Furthermore, this category includes those Christian churches and communities, which appeared at least in ten separate items within the six years under analysis. These are the Christian Adventist church, the Evangelic Christian church, the International Christian Fellowship, the Christian center, and the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Most of these churches are evangelic. Furthermore, the Evangelical Christian church is a Baptist community, while the International Christian Fellowship and Christian center are Pentecostal-charismatic churches to a varying degree, although not tied to the official Pentecostal church of Slovenia. Being evangelical churches, many of them collaborate on projects, which are regularly reported on by Duhovni utrip. Therefore, we were compelled to include a supplementary code, Evangelical churches and communities, to encompass those times when it was not possible to distinguish between covered communities. The rest of the minor Christian communities who did not pass the quantitative threshold—such as the Church of Jess Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Reformed Evangelical church, and the Greek Catholic church—have been grouped together under “Other” within the minor Christian communities (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Differentiation of minor Christian communities.

The same quantitative threshold is used in terms of the number of items applied in this case. The following communities passed that barrier: the Jewish community29, the Muslim community30, the International society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), Staroverstvo, so-called Old Faith, which encompassed contemporary communities, practicing pre-Christian, Slavic pagan religion (Belak et al. 2022), and the Baha’i community. The largest subcategory of non-Christian communities covers a variety of New Age communities and themes. Due to analytical purposes, which will be made clearer later on, we have also categorized a special category for Buddhist communities and the Trans-Universal Zombie Church of Blissful Ringing (Zombie church), a Slovenian peculiarity (Lesjak and Črnič 2016).

Taken altogether, we have coded 156 items, covering non-Christian religious communities, out of the total 540, amounting to 29 percent across the analyzed period. In terms of airtime, non-Christian communities have been given 13:14:36 or 23 percent of the whole airtime. The full overview of non-Christian communities is laid out below in Table 5, while the overview of items and airtime, categorized by large and small Christian communities on the one hand and non-Christian communities on the other, is found in Table 6.

Table 5.

Overview of non-Christian communities.

Table 6.

Comparison of the number of items and the duration of airtime.

Among the non-Christian communities, New Age topics stand out immensely, with the second-place community, the Muslim community, amounting to nearly a third of New Age’s number of items and airtime. The rest of the non-Christian communities are covered in nearly the same proportion. The general overview of non-Christian items compared with differentiated Christian communities can be found below in Table 6.

7. Analysis

The above-presented data enable us to provide an initial answer to the first research question: in what proportion are non-Christian communities covered in the framework of the television program Duhovni utrip? Firstly, it has been observed that despite the declared objective of the television program to allocate space to lesser-known religious groups in Slovenia, around half of its content and broadcasting time is dedicated to Christian communities, irrespective of their size (see Table 3). Because the focus of the program lies on minor religious communities, we can exclude the large Christian churches to obtain the following results: Minor Christian communities were allocated 37% of the total items examined, which corresponds to 41.1% of the total airtime. Non-Christian groups were covered in 28.9% of all analyzed items, which accounted for 23.2% of the program’s airtime during the period being studied. It should be noted that approximately one-third of its contents, as well as airtime, are dedicated to New Age societies. The variations among non-Christian communities are significant.

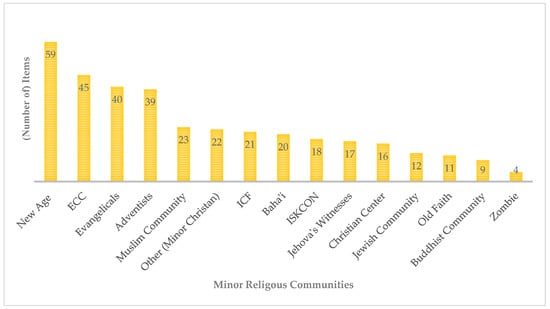

To examine the distinctions among smaller religious communities, whether they are Christian or non-Christian, we shall temporarily set aside the category of large Christian churches and direct our attention toward the Muslim population. Firstly, looking at the number of items each minor religious community was given, New Age communities stand out—perhaps surprisingly so (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparing the number of items given to a Particular Minor Religious Community, Christian or non-Christian. ECC—Evangelical Christian Church; Evangelicals—Evangelical churches and communities; ICF—International Christian Fellowship.

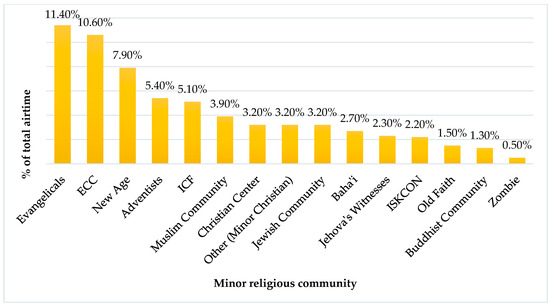

A more nuanced—and a rather different—point of view is provided by looking at the airtime afforded to each category (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparing the percentage of total airtime given to minor religious communities. Evangelicals—Evangelical churches and communities; ECC—Evangelical Christian Church; ICF—International Christian Fellowship.

We can see that the category, which groups together different evangelical churches and communities, is given by far the most airtime (11.4%). New Age communities, who have been given the largest number of items, have been given 7.9% of the total analyzed airtime. Among the top five most covered communities in terms of airtime, we find only one non-Christian category—New Age. By integrating the data from Table 6 and Figure 2, it becomes clear that the only television program within Slovenia’s public broadcaster aimed at covering minor religious communities predominantly focuses on Christian communities, regardless of their size. Our study confirms that the television program’s stated aim, which is to give space to minor religious communities, both Christian and non-Christian, is fulfilled. However, we have observed an imbalance in the coverage of minor religious communities. While the officially stated aim of the program is to proportionally reflect Slovenia’s religious field, such proportionality is clearly lacking when it comes to religious minorities.31 As we have shown above, the Muslim community is the second largest religious community in Slovenia, behind Catholics. Though the popularity of New Age communities is hard to define, it may well exceed the percentage of Muslims in Slovenia (6.2% of the religious population), though that is impossible to say based on available datasets. For example, the SPOS categorizes New Age communities as “other non-Christian”, which makes up to 0.4% of believers according to the poll conducted in 2018. Muslims in Slovenia, on the other hand, make up 6.2% of the religious population yet receive less than 4% of total airtime within Duhovni utrip. Evangelical and protestant communities have received more than a third of total airtime32, even though the SPOS found in 2018 that they make up around two percent of the religious population. Undoubtedly, these communities are intriguing, and their items provide valuable insights into an often-overlooked Christian minority. Nevertheless, considering the principle of proportionality, it is undeniable that the Muslim population is inadequately represented, confirming our initial hypothesis.

Before we discuss our findings further, it is crucial to delineate what our study understands under the label of Islamophobia. Although some trace the origins of the concept to Edward Said’s (1979) Orientalism, it truly emerged as a publicly and scientifically relevant discourse in 1997 with the publication of the Islamophobia: A Challenge for Us All report, authored by the British NGO Runnymede Trust (1997). There have been numerous attempts at defining the concept and proposing ways of measuring ever since (Allen 2010, pp. 123–93; Bleich 2011; Bleich 2012, pp. 180–83; Hajjat and Mohammed 2023, pp. 23–57). In general, we can delineate between narrow and broader definitions. Narrow definitions usually reduce Islamophobia to an active negative conception of Islam and Muslims, manifested in fear, dread, and hate (Abbas 2004, p. 28; Lee et al. 2009, p. 93; Semati 2010, p. 1), which is most commonly associated with (public) hate speech. On the other hand, broader definitions aim to move beyond explicit Islamophobia. For example, according to Stolz (2005, p. 548), Islamophobia is a “rejection of Islam, Muslim groups and Muslim individuals on the basis of prejudice and stereotypes. It may have emotional, cognitive, evaluative as well as action-oriented elements (e.g., discrimination, violence).” In similar vein, the Runnymade Trust provides one of the most authoritative definitions of Islamophobia as “any distinction, exclusion, or restriction towards, or preference against, Muslims (or those perceived to be Muslims) that has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life” (Runnymede Trust 2017, p. 1). We find this definition to be of great help. There are two key components that are relevant for our analysis and which are often left out in narrower definitions: firstly, an act may be recognized as Islamophobic, even if the conscious purpose of the actor was not; secondly, Islamophobia does not pertain only to active feelings of fear and hatred, manifested in explicitly discriminatory acts, but it may also be seen as the result of (passive) exclusion from public life—like for example media. In addition, the Runnymede Trust provides a crucial shorter definition that says that Islamophobia is “anti-Muslim racism” (Ibid.). Indeed, the racialization of Muslims is one common ground of many Islamophobia studies (Garner and Selod 2014; Kamran Sufi and Yasmin 2022; Hajjat and Mohammed 2023, p. 17). According to a useful outline by Garner and Selod (2014, p. 6), racialization “draws a line around all the members of the group; instigates ‘group-ness’, and ascribes characteristics, […] sometimes because of ideas or where the group comes from, what it believes in, or how it organizes itself socially and culturally”. In short, for the purposes of this study, we delineate between purposeful, explicit Islamophobia in terms of direct discrimination and hate speech and a broader understanding of Islamophobia as acts that may not be direct nor purposive but nevertheless be in itself discriminatory. In either case, Islamophobia entails a form of racialization of Islam or Muslims.

Returning now to our analysis, we have found no evidence of any kind of explicit Islamophobia in television’s coverage of (Slovenian) Muslims. That is, our analysis has not found any evidence of Islamophobia understood as explicit and intentional hate speech.33 However, this does not mean that the amount—and style—of coverage given to Muslims cannot be recognized as Islamophobic and be simultaneously problematic from the point of view of fostering religious literacy. We claim that the presented figures may be worrisome from two particular standpoints: firstly, they show that minor Christian religious groups are given a disproportionate amount of airtime given the number of their adherents in Slovenia—especially in comparison to the Muslim community; and secondly, as will be discussed in greater detail below, the characteristic of the Muslim coverage is in some aspects distinctively different from the items covering (smaller) Christian communities. As shown above, taken together, minor Christian communities were given 41% of airtime in the period between 2015–2020, while the Muslim community only received 3.9%. Not only does this mean that the Muslim community appears to have less access to television programs dedicated to minor religious communities, but it also means that the general public does not have a proper chance to be informed about the characteristics of, and ongoings in, the Muslim community. In other words, the general public’s religious literacy is not being fostered as well as it could be. This is due to the exclusion of Muslim communities from their fair share of television coverage, which can be labeled as Islamophobic.

Focusing now on the second critical reading of the above-discussed results, we want to propose a further qualitative viewpoint. In order to present our qualitative findings, we first offer an overview of the number of items per category per year (Table 7).

Table 7.

Number of items per community per year within the analyzed time period.

One notable observation is the consistent allocation of items to each community, particularly in the case of the Muslim community of Slovenia. This can be explained by items being, by and large, dedicated to the celebration of religious holidays, which holds true for all non-Christian communities. Retaining our focus on the Muslim community, we can see that the total number of items given to the Muslim community is 23. Almost half of these (10) are dedicated to the celebration of the month of Ramadan. A further seven are specifically dedicated to the matters of the largest Muslim community, the IC, while just one addresses the other registered Muslim community—the Slovenian Muslim community. Just two items are dedicated to the view of the Muslim doctrine when it comes to social issues (charity and euthanasia), and one addresses theological and practical differences within the global Muslim community. The last two items are dedicated to books authored by members of the IC. In comparison, items dealing with smaller Christian communities are less likely to be explicitly tied to the celebration of a particular religious holiday.34 Instead, members of smaller Christian communities are regularly invited to speak on general social issues pertaining to everyday life, such as intergenerational cohabitation and the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren; important values on which to base a healthy relationship between a husband and wife35; how to run a business successfully and how to live a better life (self-help); as well as the matter of drug addiction and rehab.

In other words, Muslims are racialized as homogenous believers, while (minority) Christians are normalized and heterogenized as citizens, competent of speaking about any given topic—religious or non-religious. Thus, we believe Muslims are subject to a nuanced process of media framing, which cannot be labeled as explicitly Islamophobic, though the underlying mechanism is Islamophobic as it produces a representation of Muslims as a relatively homogenous group. By this, we do not mean to say that such television treatment results in Islamophobia, be it implicit or explicit. We do not claim that viewers of the program in question become (more) Islamophobic as the result of their exposure to Duhovni utrip—our study has not measured the effect of such television coverage. However, we do claim that the characteristics of the television coverage can in itself be labeled as implicitly Islamophobic if we understand the term in its broader terms, which include the exclusion of a religious community from the public space. Though the audience may annually be provided with information regarding key traits of Islam—fasting, prayer, and the holy month of Ramadan—the televised framing remains important. For as long as Muslims speak only as people wholly marked by their religious creeds, they may remain seen as the racialized Other—even if they are not subject to any explicit Islamophobia. This is dissimilar to common characteristics of Muslim othering, namely, explicit islamophobia, which has been reported on extensively by the scientific literature—both international (Ahmed and Matthes 2017; Li and Zhang 2022) and Slovenian (Pucelj and Šabec 2018; Zalta 2017, 2020; Porić and Črnič 2021).

A notable exception to this trend is a study of media portrayals of Muslims in news segments of TV Slovenia (Rakuša 2008). The study found that prime-time news items of Slovenia’s public broadcaster rarely cover Muslims to inform the public about their community—instead, in most cases, they are reported on in times of social problems related to Muslims. Indeed, the study points out that Muslims are portrayed as “people, who are completely determined by their religion” (Ibid., p. 140).36 Thus, the study found that the process of Othering is not built on explicit Islamophobia but on indifference. Nevertheless, such discourse framing may be recognized as the bedrock of more explicit Islamophobia, as it builds up a community as wholly foreign to most of the population—by implicitly pointing out the differences, it is hard for the public to recognize similarities.

8. Discussion

As mentioned before, the editorial office for religious broadcasting in Slovenia adheres to a yearly plan regarding the extent of coverage provided to religious communities. We have designated this model as proportional because its objective is to accurately depict the religious communities of Slovenia in a manner proportional to their presence within Slovenia’s religious field. From this perspective, it can be stated that the creators of the TV program Duhovni utrip have successfully dedicated more time to non-Christian communities and topics (see Table 6). However, we have demonstrated that assuming the bulk of the audience consists of Catholics, the program strongly emphasizes creating content that is predominantly Christian, either Protestant or Catholic. This is also influenced by the fact that most creators—journalists—of the program personally identify as Catholic37, with a number of them having graduated from the Faculty of Theology in Ljubljana. There are no active Muslim journalists working on any religious programme38, which undoubtedly influences the variety of topics Duhovni utrip covers. In this sense, we can speak of unintentional Othering, as it is not a result of personal or collective aim to sideline Muslims; rather, it can be considered as a result of the lack of religious plurality among content creators.39 In general, the content of any religious program is, by and large, decided by its editor, although the chief editor of the editorial office for religious broadcasting regularly gives their own input. In most cases, the decision-making process has a top-down orientation, though journalists are encouraged to provide their own suggestions. The religious make-up of journalists ties well in with the fact of Slovenia’s Latin pattern of religious-cultural development (Martin 1979). In this light, the religious broadcaster can be seen as another contested field of clerical and anticlerical social forces—although currently, it is not much of a contest.

Nevertheless, while considering the issue of religious literacy, it is important to examine whether public media in countries heavily influenced by a specific religion should prioritize proportionality. One of the conclusions of the RELIGARE (Religious Diversity and Secular Models in Europe) report is that it is possible for this not to be the case (Foblets and Alidadi 2013). The initiative sought to tackle the problem of how to “strike a balance between the application of non-discrimination norms (and their further expansion) and the protection of the right to freedom of religion and belief” (Ibid., p. 3). The study examined 10 nations (Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany, Great Britain [sic], France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and Turkey), with a specific focus on four aspects of social involvement, including “access to and the use of public space and state-supported activities” (Ibid.), with the latter including the usage of public media (Ibid., p. 35–37), claiming that “public media are an important instrument for the State to protect, advance or even guarantee this [religious] pluralism” (Ibid., p. 35). As such, it is a relevant report for our study.

Though the detailed analysis of the study is beyond the scope of our paper, it is worth looking at the four-point categorization of the countries’ religious broadcasting within their public media outlets. Type A was designated for Turkey and Bulgaria, where “only dominant religious” are given access, with “no real presence of other minority religions” (Ibid., p. 36). Type B countries, such as the United Kingdom and Denmark, offer religious broadcasting, but there is “no direct access (licence) for different religious groups”, as well as guarantee “strong presence of the dominant ‘established’ religion” (Ibid.). Type C countries, on the other hand, make use of a licensing scheme to guarantee direct access to a plurality of religions. Finally, type D countries, such as Belgium and the Netherlands, offer direct access to a plurality of religious and non-religious ethnic groups.40 Though Slovenia was not part of the original study, we believe the RELIGARE project provides relevant context for our own analysis. While we accept that straight comparison is not possible, we believe it can shed further light on our own study, considering the officially delineated airtime to various religious churches and communities in Slovenia (see RTV SLO 2019). Based on that, we can roughly categorize Slovenia amongst Type B countries, which do offer some access to religious communities through their inclusion in regular television programming but maintain a dominant presence of the established (Christian) traditions.

Finally, it is worth returning to the issue of religious literacy. Other studies have shown that developing religious literacy may be key to the successful navigation of the increasing plural religious field—and religiously plural society at large (Dinham and Francis 2015b). Based on our analysis, it is impossible to conclude that Duhovni utrip is managing to foster religious literacy. If we presume that the purpose of religious literacy is to counter prejudice and stereotyping, then we can conclude that Duhovni utrip fails in fostering appropriate religious literacy when it comes to the Muslim populations of Slovenia. This points to greater problems of Slovenia’s secular regime. As shown by the RELIGARE report, the state can actively intervene where possible—including via the public broadcaster—in order to ensure a well-functioning secular regime: “The position of minorities should not be neglected, nor should the organization specificities of some minority religious in particular (as is the case for Islam) (Foblets and Alidadi 2013, p. 39). While we cannot conclude that religious minorities, such as Muslims, are necessarily neglected by Slovenian religious broadcasting, we can nevertheless claim that they are underrepresented in the context of religious broadcasting. In this light, it might be worthwhile to consider a more active state intervention in the form of a disproportional model of representation of religious communities—at least in those TV programs that are specifically aimed at covering smaller religious communities.

9. Conclusions

Our research argues that contemporary European religious diversity necessitates a revision in the way religions are governed by the state, and we identified religious literacy as an essential tool that can facilitate effective participation in a religiously diverse society. Focusing on public media as a means of fostering religious literacy, our analysis has examined religious broadcasting inside Slovenia’s public broadcaster, RTV SLO. Focusing specifically on the representation of the largest non-Christian community in Slovenia—the Muslim community—the study has revealed that Muslims are significantly underrepresented in (public) religious broadcasting, confirming our initial hypotheses. In addition, we assert that the qualitative nature of their coverage categorizes them as the (racialized) religious Other, even though the coverage itself does not employ any explicit Islamophobic tendencies. In both cases, however, we have found the coverage of Muslims to be Islamophobic due to their under-representation and racialized homogenization. Furthermore, our research has demonstrated that the assumption of a proportional model for the representation of religious communities is not universally applicable. Countries have the option to choose a different strategy based on their resources and secular models, which might potentially enhance religious literacy. It is crucial to highlight that the absence of Muslims and the inadequate representation of their experiences in Duhovni utrip is a structural problem rather than an individual one. We want to emphasize that we are not asserting that the creators of these television programs or items have any inherent bias or explicit Islamophobic tendencies. Our main contention is that the state should consistently prioritize the promotion of religious literacy and actively intervene whenever feasible to support the development of capable citizens in religiously diverse societies.

Finally, we want to outline the limitations of our research, of which there are three. Firstly, to obtain a comprehensive understanding of how the national public broadcaster covers religious communities, we must consider every program produced by its religious broadcasting editorial office. Although this was outside the parameters of our study, we are confident that such an overview would offer a comprehensive understanding of the management of religious broadcasting. Secondly, it is necessary to undertake an extensive qualitative analysis of the actual material to supplement the quantitative element of our investigation. Thirdly, our study focuses exclusively on the production of television items, setting consumption aside. We recognize that valuable insight might be gained by a study that would rather focus on who and how consumes such television items.

Nevertheless, we consider our study to be a valuable undertaking, highlighting the necessary reassessment of how states handle religious affairs as concerns of active governance to maintain meaningful cohabitation.

Funding

This research was funded by the research programme “Problems of Autonomy and Identities at the Time of Globalisation” (P6-0194) and the training of Junior Researchers. Both are funded by the Slovenian Research Agency (ARIS).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s. The datasets will be publicly available at the Slovenian ADP—the Social Science Data Archives: https://www.adp.fdv.uni-lj.si/, accessed on 30 May 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 | This is not to say that these changes are unique to Europe, with the obvious counter-example being the United States—rather our research focus pertains to Europe, particularly to Slovenia. |

| 2 | The quantitative dimension of contemporary religious change is inherently linked to global migration patterns—particularly the settling of Muslim migrants in Europe. Although Muslim communities have been present in Europe at least since the 8th century (Goody 2008; M. Berger 2014), the rise in their quantity is an unmissable mark of Europe in the past decades (AlSayyad and Castells 2002; Pettersson 2007; Statham and Tillie 2016; Duderija 2018). Becoming the largest religious minority in Europe (Hunter 2002), Islam has given rise to well-documented Islamophobic backlashes (Zalta 2020) as well as changes in state regulation of religious communities (Cesari and McLoughlin 2016; Zalta 2018). |

| 3 | This is not to say that the framework of religious literacy is without its critics. See, for example, Ellis (2023). |

| 4 | Some studies have also shown that religious literacy mechanisms can be used by religious communities themselves in order to reduce the levels of prejudice and discrimination felt within the community towards a different religious community (Burch-Brown and Baker 2016). |

| 5 | The Slovenian Catholic church, for example, notes that 50 percent of all children born in 2021 were baptized (Slovenska škofovska konferenca 2022). |

| 6 | Keep in mind that this is the number of officially registered communities. In 2010, researchers (Črnič et al. 2013) noted that many new religious movements operate as associations, the most widespread form of legal entity in private law in Slovenia. In this light, Črnič and Lesjak (2006) estimated that there may be up to 100 new religious movements in Slovenia, mostly of New Age variety. |

| 7 | The pluralization of the religious field was made possible by the expansion of the relevant legal framework (Črnič et al. 2013, pp. 213–18). |

| 8 | Triglav being the highest mountain in Slovenia. |

| 9 | Additionally, the IC unofficially estimates the number of Muslims in Slovenia at around 80 thousand, which amounts to four percent of the general population. Despite different estimates, we believe the SPOS data are valid. Despite lower estimates, they have managed to capture an increase in the size of the Muslim community using a consistent methodology. Additionally, the team behind SPOS consists of experienced researchers, which is why we believe their estimates are reliable. |

| 10 | The somewhat large increase in the Muslim population from 2016 to 2018 necessitates additional explanation despite the inability to offer definitive answers, thus leaving us with educated speculations. We believe three main factors may have contributed to this phenomenon: firstly, the influx of Muslims as a result of the so-called refugee crises since 2015; secondly, the unique demographics of the Muslim population, characterized by higher birth rates (Kapitanovič 2024); and thirdly, the increased confidence of the Muslim community, who may feel more at ease openly identifying as Muslims due to the establishment of Slovenia’s first official mosque in the capital city of Ljubljana. Conversely, the Protestant community experienced an almost twofold increase in its population from 2002 to 2018. As a result of a serious lack of research in this particular field, we are once again left with educated speculations. During the early 2000s, there was a notable revival of Pentecostalism in Ljubljana, leading to the establishment of several Pentecostal churches around Slovenia. In addition, the 2000s witnessed a notable expansion in Evangelical churches and communities in Slovenia. We believe these causes may account for the growth of the Protestant community. |

| 11 | Excluding Orthodox Christians, who are not relevant to our study, as they are part of the most established Christian churches in Slovenia. This will be expanded upon below. |

| 12 | See Note 10 above. |

| 13 | Additionally, STA only provides news clippings and does not offer television or radio services. |

| 14 | However, up until 2023, when a new law was introduced, the governing body of RTV SLO was mostly comprised of parliament-approved members. To depoliticize the public service provider, a new law governing RTV SLO was introduced (Novak 2023). Amongst the biggest changes was the dissolution of any power given to the parliament in the naming of members to the governing body of RTV SLO. |

| 15 | By 2012, Slovenia had 81 television and 90 radio stations—including public broadcasting services (Broughton Micova 2014, p. 33). |

| 16 | A detailed discussion of religious broadcasting and its historic development is beyond the scope of our discussion. For an introduction to religious broadcasting in the UK and the US, see Kay (2009). |

| 17 | This can also be thought of in terms of Hjarvard’s (2020) first form of mediated religion. |

| 18 | To the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies conducted—in Slovene or English—on religious broadcasting within Slovenia’s public broadcast provider. |

| 19 | It is crucial to remember that these rules apply to all content created by the religious broadcasting editorial office, not just one program. Nevertheless, they offer valuable parameters for our assessment. |

| 20 | To be fully transparent, it should be pointed out that the author worked as a journalist on the television show Duhovni utrip from January to June 2021. During that time, they produced a variety of content, including a brief documentary about Slovenia’s only Forest Buddhist hermitage, Samanadipa. Given this, the study’s threshold was purposefully set at the end of 2020 to account for the possibility that the author would have a direct impact on the production of the program under consideration. |

| 21 | The fully digitalized archive of the program can be accessed through the digitalized platform MMC RTVSLO: https://365.rtvslo.si/oddaja/duhovni-utrip/275 (accessed on 2 June 2024). |

| 22 | Throughout the article, the airtime of episodes and items is written in the form of hours:minutes:seconds. |

| 23 | The precise measurement of airtime is unattainable due to the inherent limitations of analyzing data using the official digital player, which may not provide perfect accuracy. Each item’s reported airtime has an estimated margin of error of two seconds. However, we believe that this fact should not affect our study as we have continuously utilized the same measuring technique, regardless of the occurrence or item in question. |

| 24 | As a method of studying religions, video analysis is still in its infancy (Knoblacuh 2011). Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out that it is primarily used as a method of studying religious material, not necessarily public media items, pertaining to religious communities. |

| 25 | For an introduction to the methods and theories informing film and television analysis, see Benshoff (2016). |

| 26 | We use the term religious community loosely. By “religious community”, we do not mean to focus only on the officially registered religious communities but also on other kinds of communities and organizations, such as associations and societies, whose bedrock and leadership are religious or spiritual. For example, a number of items covered the initiative undertaken by the Slovenian ADRA, that is, the Adventist Development and Relief Agency. As such, we categorized these episodes as pertaining to the Slovenian Adventist community. Similarly, those items that covered the events organized by the Vesela novice society, which is led by Zvonko Turinski, pastor of the Evangelical Christian church and officially tied to the Child Evangelism Fellowship, were categorized as belonging to the Evangelical Christian church. |

| 27 | In the majority of cases, each item focused on one particular religious community. When this was not the case, it was due to several evangelical communities participating in the same event, which was being covered by the show. |

| 28 | Additionally, it is worth noting that the large Christian churches, which have their own specialized television programming, receive a significant amount of coverage in terms of the number of items and airtime. |

| 29 | In our study, the label “Jewish community” pertains to any registered or non-registered Jewish community, not just the official Jewish Community of Slovenia. This is important to emphasize due to notorious differences in religious teachings and political views among Slovenian Jewish communities. |

| 30 | As is the case with the Jewish community, the label Muslim community, in our case, describes any Slovenian Muslim community, not just the largest one—the Islamic community of Slovenia. |

| 31 | Furthermore, one struggles to find any attention given to one of the fastest growing »religious« groups—the atheists or nones (Smrke and Uhan 2012). |

| 32 | Combining the following categories: »Evangelicals«, »ECC«, »Adventists«, »ICF«, and »Christian center«. |

| 33 | In Slovenia in general, Muslims–of whom the vast majority are of former Yugoslav descent–have been regular targets of prejudice, which is tied with the “pejorative association of ‘Non-Slovenian’s, ‘southerns’ or ‘Balkanites’” (Bajt 2008, p. 224). According to Bajt, “the prevalent negative stereotyping of members of other Yugoslav nations is tied with the fact that significant numbers of Muslims came to Slovenia as internal Yugoslav economic migrants who found work in low-skill sectors of industry” (Ibid.). Additionally, according to the SPOS, nearly 16% of Slovenians have a negative attitude toward Muslims, with 5% of them stating they have a very negative view of Muslims (Toš 2020, p. 189). The Jewish community is the second religious group that is most likely to be perceived unfavorably, with 8.4% of Slovenians expressing such views. |

| 34 | There is a telling example pertaining to the disparate coverage of religious holidays. The year under consideration is 2017 when the Islamic community celebrated 100 years of existence in Slovenia, a celebration linked to the 100th anniversary of the first Slovenian mosque in the village of Log pod Mangartom, established during World War I. At the same time, Slovene Protestants celebrated the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. In this year, the Islamic community was covered in four items, two of which were dedicated to their anniversary in Slovenia. On the other hand, smaller Christian communities, the vast majority of which represent a variety of Protestant, evangelical communities, were the subject of 41 items. Among them, 11 were directly dedicated to the celebration of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. |

| 35 | Such discussions are explicitly heteronormative. |

| 36 | It is likely that this holds true for other non-Christian communities as well—though a thorough discussion is beyond the scope of our paper. |

| 37 | Additionally, the editorial office for religious broadcasting famously employs a Franciscan nun who is the leading presenter of the Obzorja duha, the main program produced by the editorial office for religious broadcasting. |

| 38 | However, we cannot substantially claim that this is a result of any kind of explicit discrimination. |

| 39 | Furthermore, one could suggest that the coverage of Muslims reflects a confirmation bias, as in that the particular framing of Muslims and their underrepresentation is done to reflect common social representations about Islam. Our study cannot prove or disprove this; however, we would sooner state that this is not the case, as the two main causes of Muslim coverage are the supposed representational model of covering religious communities and the religious makeup of content creators. |

| 40 | It is important to mention that a shared characteristic across all the countries being discussed is the scarcity of resources available for providing airtime to religious organizations (Foblets and Alidadi 2013). |

References

- AAR. 2024. AAR Religious Literacy Guidelines. Available online: https://aarweb.org/AARMBR/AARMBR/Publications-and-News-/Guides-and-Best-Practices-/Teaching-and-Learning-/AAR-Religious-Literacy-Guidelines.aspx (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Abbas, Tahir. 2004. After 9/11: British South Asian Muslims, Islamophobia, Multiculturalism and the State. The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 21: 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, Philip. 2019. A Step-by-Step Guide to Qualitative Data Coding. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Saifuddin, and Jörg Matthes. 2017. Media Representation of Muslims and Islam from 2000 to 2015: A Meta-Analysis. International Communication Gazette 79: 219–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitamurto, Kaarina, and Scott Simpson, eds. 2013. Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Chris. 2010. Islamophobia. Farmham: Ashgate Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- AlSayyad, Nezar, and Manuel Castells, eds. 2002. Muslim Europe or Euro-Islam: Politics, Culture, and Citizenship in the Age of Globalization. Transnational Perspectives. Lexington Books. Berkeley: Center for Middle Eastern Studies, University of California at Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, Nancy Tatom. 2013. Spiritual But Not Religious? Beyond Binary Choices in the Study of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 258–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy Tatom. 2021. Studying Lived Religion: Contexts and Practices. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bajt, Veronika. 2008. Muslims in Slovenia: Between Tolerance and Discrimination. Revija za Sociologiju 39: 221–34. [Google Scholar]

- Baralt, Melissa. 2011. Coding Qualitative Data. In Research Methods in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Alison Mackey and Susan M. Gass. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 222–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belak, Mateja, Saša Babič, Andrej Pleterski, Katja Hrobat Virloget, Matjaž Bizjak, Cirila Toplak, Lenart Škof, Miha Mihelič, Rudi Čop, and Franc Šturm. 2022. Staroverstvo v Sloveniji: Med Religijo in Znanostjo. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benshoff, Harry M. 2016. Film and Television Analysis: An Introduction to Methods, Theories, and Approaches. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Maurits. 2014. A Brief History of Islam in Europe: Thirteen Centuries of Creed, Conflict and Coexistence. Leiden: Leiden University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter. 1980. The Heretical Imperative: Contemporary Possibilities of Religious Affirmation. Garden City: Anchor Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter. 2014. The Many Altars of Modernity: Toward a Paradigm for Religion in a Pluralist Age. Berling: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, Peter. 1994. Religion and Globalization. Theory, Culture & Society. London and Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Peter. 2011. Religious Pluralization and Intimations of A Post-Westphalian Condition. In A Global Society. Edited by Patrick Michel and Enzo Pace. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, Penny A., and Robert J. Nash. 2007. Teaching for Religious Literacy in Public Middle Schools. Middle School Journal 38: 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, Erik. 2011. What is Islamophobia and How Much is There? Theorizing and Measuring an Emerging Comparative Concept. Americal Behavioral Scientist 55: 1581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, Erik. 2012. Defining and Researching Islamophobia. Review of Middle East Studies 46: 180–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broughton Micova, Sally. 2014. Public Service Broadcasting in Slovenia: Creating Stars. In The Media in Europe’s Small Nations. Edited by David Huw. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Steve. 2011. Secularization. In Defence of an Unfashionable Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burch-Brown, Joanna, and William Baker. 2016. Religion and reducing prejudice. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 19: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, José. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cesari, Jocelyne, and Seán McLoughlin. 2016. European Muslims and the Secular State. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Črnič, Aleš. 2013. Neopaganism in Slovenia. In Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Edited by Kaarina Aitamurto and Scott Simpson. London: Routledge, pp. 182–94. [Google Scholar]

- Črnič, Aleš, and Gregor Lesjak. 2006. A Systematic Study of New Religious Movements – The Slovenian Case. In Religions, Churches and Religiosity in Post-Communist Europe. Edited by Irena Borowik. Krakow: Nomos, pp. 142–157. [Google Scholar]

- Črnič, Aleš, Mirt Komel, Marjan Smrke, Ksenija Šabec, and Tina Vovk. 2013. Religious Pluralisation in Slovenia. Teorija in Praksa 50: 205–32. [Google Scholar]

- Črnič, Aleš, and Anja Pogačnik. 2021. Religija in šola: Poučevanje o Religiji in njena Simbolna Prisotnost v javni šoli. Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, Založba FDV. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace, and Adam Dinham. 2019. Religious literacy in modern Europe. In Religious Literacy, Law and History. Edited by Alberto Melloni and Francesca Cadeddu. London: Routledge, pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dinham, Adam, and Matthew David Francis, eds. 2015a. Religious Literacy in Policy and Practice. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dinham, Adam, and Matthew David Francis, eds. 2015b. Religious Literacy: Contesting an Idea and Practice. In Religious Literacy in Policy and Practice. Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dinham, Adam, and Martha Shaw. 2017. Religious Literacy through Religious Education: The Future of Teaching and Learning about Religion and Belief. Religions 8: 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinham, Adam, and Stephen Jones. 2010. Religious Literacy Leadership in Higher Education. York: Religious Literacy Leadership in Higher Education Programme. [Google Scholar]

- Dragoš, Srečo. 2020. Erozija religioznosti v Slovenskem javnem mnenju in med študent(kam)i socialnega dela. Socialno Delo 59: 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Duderija, Adis. 2018. Islam and Muslims in the West: Major Issues and Debates. New York: Springer Science Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Justine Esta. 2023. The Politics of Religious Literacy. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Enstedt, Daniel. 2022. Religious Literacy in Non-Confessional Religious Education and Religious Studies in Sweden. Nordidactica–Journal of Humanities and Social science Education 1: 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Foblets, Marie-Claire, and Katie Alidadi. 2013. Summary Report on the RELIGARE Project. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/docs/results/244635/final1-religare-final-publishable-report-nov-2013-word-version.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Garner, Steve, and Saher Selod. 2014. The Racialization of Muslims: Empirical Studies of Islamophobia. Critical Sociology 41: 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, François. 2020. Religion, Modernity, Globalisation: Nation-State to Market. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Giorda, Maria Chiara. 2019. Different illiteracies for different countries. In Religious Literacy, Law and History. Edited by Alberto Melloni and Francesca Cadeddu. London: Routledge, pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Giordan, Giuseppe. 2014. Introduction: Pluralism as Legitimization of Diversity. In Religious Pluralism: Framing Religious Diversity in the Contemporary World. Edited by Giuseppe Giordan and Enzo Pace. New York: Springer, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Goody, Jack. 2008. Islam in Europe. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- GOV.SI. 2022. Media. Available online: https://www.gov.si/en/policies/culture/media/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Graber, Doris A. 1985. Approaches to Content Analysis of Television News Programs. Comm 11: 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjat, Abdellali, and Marwan Mohammed. 2023. Islamophobia in France: The Construction of the “Muslim Problem”. Athens: The University of Georgia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halafoff, Anna, Andrew Singleton, Gary Bouma, and Mary Lou Rasmussen. 2019. Religious literacy in Australia’s Gen Z teens: Diversity and social inclusion. Journal of Beliefs & Values 41: 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heelas, Paul, ed. 2005. The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion Is Giving Way to Spirituality. Religion and Spirituality in the Modern World. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2020. Three Forms of Mediatized Religion: Changing the Public Face of Religion. State Religion and Church in Russia and Worldwide 38: 41–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]