Shaping Urban Religious Topography in the Iberian Peninsula between the Fourth and Sixth Centuries: “Coopetitive” Rivalry and Social Power

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. From the Decline of Temples to the Rise of Basilicas

3. The “Coopetition” between Laypersons and Bishops for the Christian Building Projects

4. Tarraco, Barcino and Emerita in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries: Local and Regional “Coopetition”17

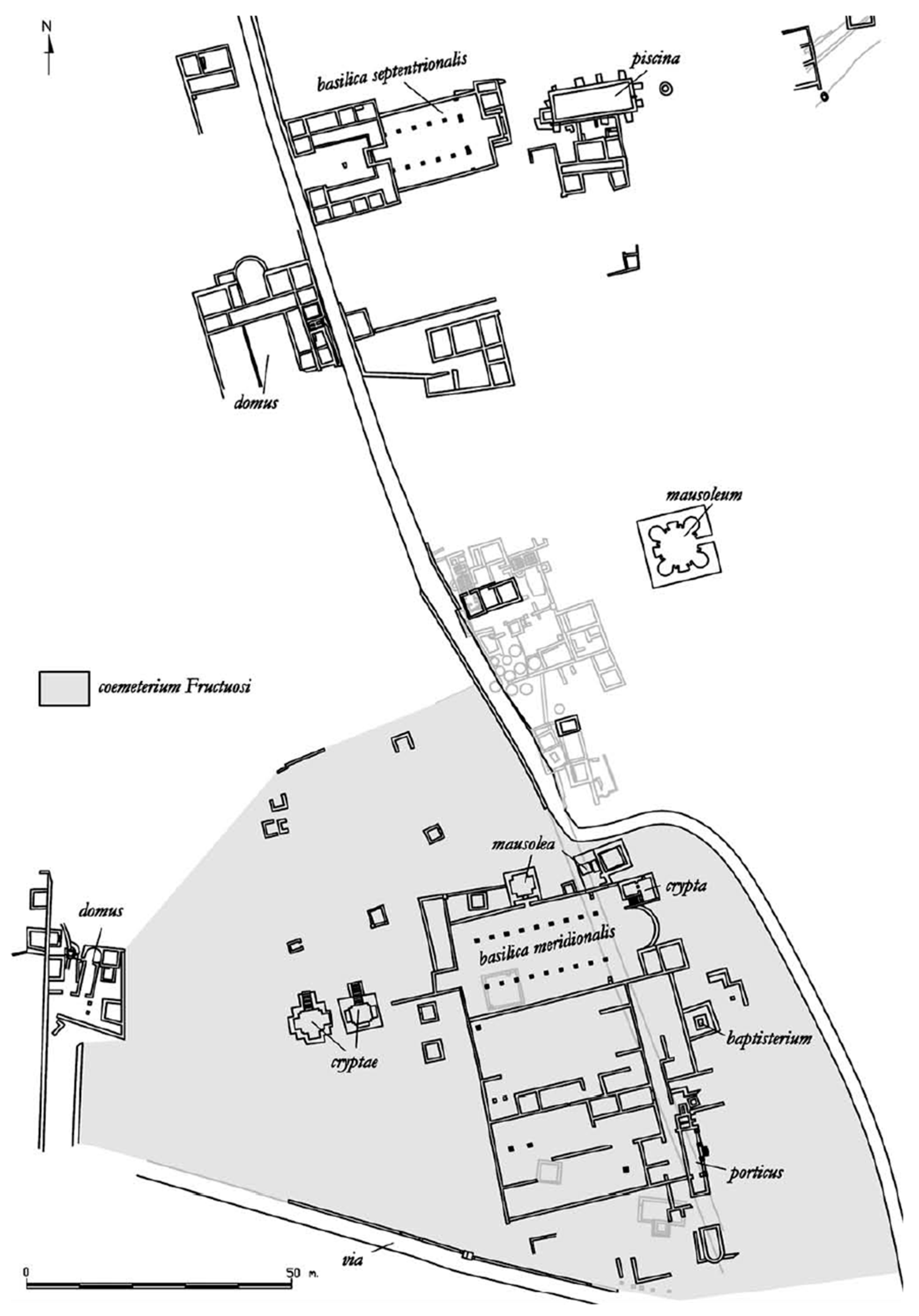

4.1. Tarraco

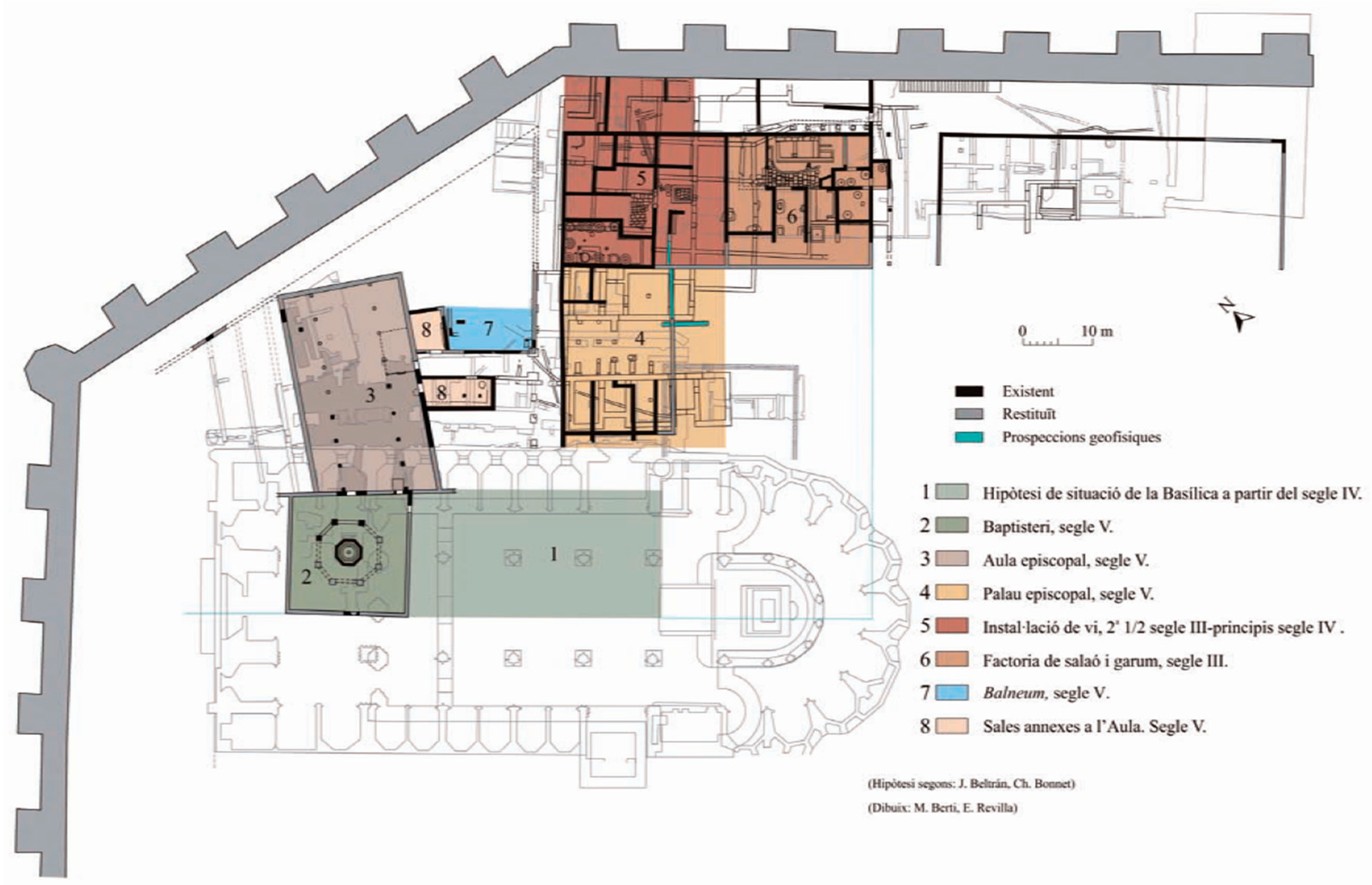

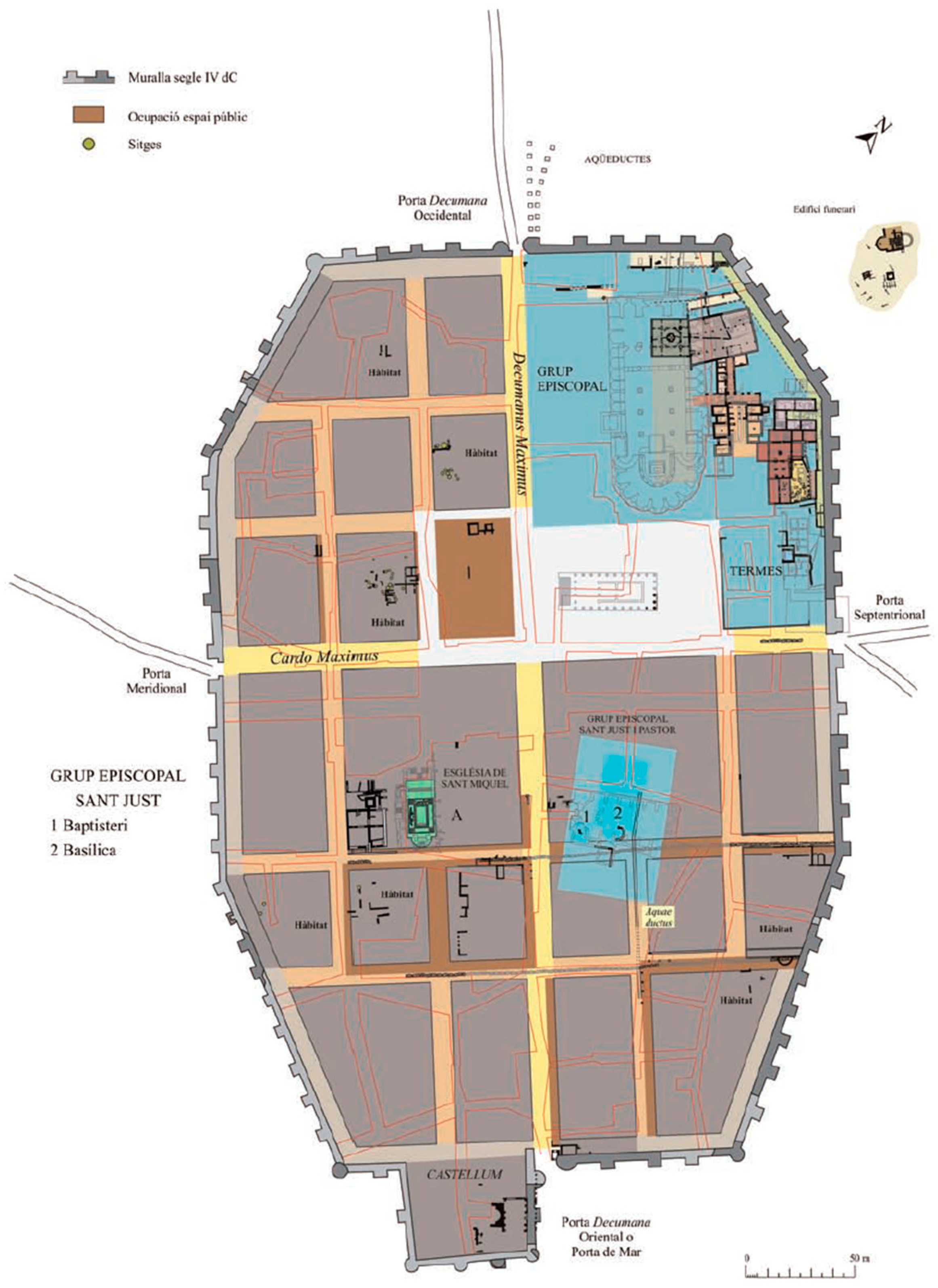

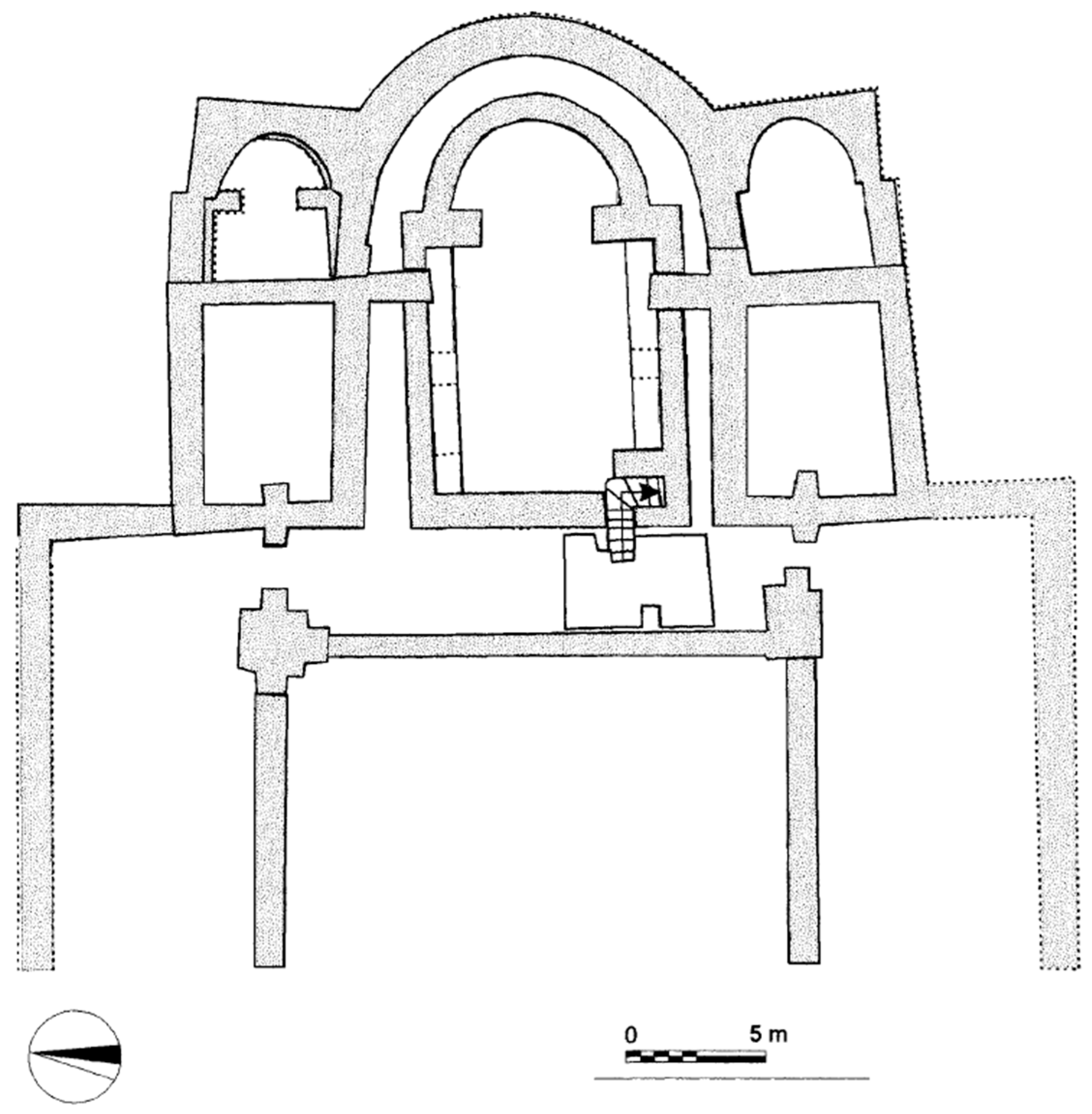

4.2. Barcino

4.3. Augusta Emerita

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Aude Busine discusses the process of “secularisation” of the pagan city after the collapse of the civic religion, following (Brown 1995, p. 52). |

| 2 | On the domestic spaces of Christian worship in the first three centuries of the era, see (Bremmer 2020, pp. 48–74). On the ongoing vitality of Christian private worship in the houses of the Roman aristocracy throughout the fourth century, see (Bowes 2008, pp. 99–103). |

| 3 | One of these domus ecclesiae may have been identified in Augusta Emerita (Mérida); however, the evidence consists solely of a non-dated chrismon painted on the wall of a cistern within the house. This alone is not compelling enough to conclusively identify this space as a domus ecclesiae (Sastre de Diego 2011, pp. 568–69). |

| 4 | In contrast to the Iberian situation, the African churches began to amass a rich heritage from the beginning of the fourth century (Buenacasa 2004, pp. 500–9), reflected in the archaeological and literary record, with the documentation of dozens of Christian basilicas dating back to the fourth century, e.g., (Gui et al. 1992, passim; Leone 2007, pp. 89–96; Baratte et al. 2014, passim). This spread of religious buildings was also associated with the competition between the Donatists and Catholics over the control of basilicas (Lander 2017, pp. 87–89, 119–29). |

| 5 | The prevalence of private churches in shaping Christian religious topography in Rome and Constantinople during the fourth century has been brilliantly analysed in (Bowes 2008, pp. 62–124). She convincingly argues that the Roman aristocracy, as in previous centuries, continued, to a large extent, to capitalise on the city’s religious offerings, outside episcopal oversight and control (p. 80). Similarly, in fourth century Aquileia, there may have been intense rivalry between aristocratic families and bishops over the control of Christian relics (Sotinel 2005b, pp. 67–71). |

| 6 | This is not to say that some intellectuals—already in fourth century Hispania—were acting as “religious entrepreneurs” (Rüpke 2018, p. 324), instrumentalising the religious capital offered by Christianity to provide an attractive liturgical and doctrinal offering. The paradigmatic case is that of Priscillian. |

| 7 | This is reflected in the anxiety shown by the bishops in the records of the Council of Iliberris (early fourth century) before the problems they had to face in what was a largely “pagan” society. |

| 8 | On this phenomenon in north Africa, see (MacMullen 2009, pp. 57–59). |

| 9 | According to (Ward-Perkins 1984, p. 70): “It is clear that for most of the propertied classes the construction of churches was a wholly new venture into public building, or a venture into it after several decades of inactivity”. To this renewed euergetism, (Peter Brown 2012, p. 88) adds the innovative element of eschatological reward: “For each gift opened up a path that led directly from earth to heaven”. |

| 10 | This is highlighted by (Lewis 2021, p. 122, figs. 5 and 10). The problems arising from these documentary sources are acknowledged by Lewis throughout his work, and he admits that it is highly probable that the participation of laymen is under-represented (pp. 124, 138, 267). |

| 11 | The same phenomenon is analysed in Rome by (Bowes 2008, p. 72). On the important role which small donors played in the embellishment and provision of goods for local churches, see (Brown 2012, pp. 39–42). |

| 12 | “Quant à toutes les basiliques qui ont été construites en divers lieux et se construisent chaque jour, il a paru bon, conformément à la règle des canons antérieurs, qu’elles demeurent sous l’autorité de l’évêque sur le territoire duquel elles sont situées” (Conc. Aurelian., c. 17, ed. Gaudemet and Basdevat 1989, p. 83). |

| 13 | “[…] Y si algún seglar desease consagrar una basílica edificada por él mismo, no se atreva en modo alguno a apartarla del régimen general de la diócesis, bajo el pretexto de que se trata de un monasterio, si no viviere allí una comunidad religiosa bajo una regla aprobada por el obispo” (Conc. Ilerd., c. 3, ed. Vives 1963, p. 56). |

| 14 | John Chrysostom in his homily 18 encouraged the domini to build churches in their states because of the many benefits that this would provide them, such as their personal enhancement through gaining an appropriate mausoleum for themselves and their families or the guarantee of a permanent evocation of their memory through the hymns and prayers sung there by the faithful. Martínez Maza (2021) has recently highlighted how the Christianisation of rural areas in Hispania during the fourth and fifth centuries would have been orchestrated mainly by the lay domini, through their own doctrinal and liturgical strategies. |

| 15 | The canons of the Hispanic councils from the sixth and seventh centuries seem to reflect a moral and economic competition between the laymen and bishops over the control of the churches and their goods. For example, in canon 3 of the Council of Lerida in 546, and citing canon 17 of the Council of Orleans, the bishops of Tarraco tried to prevent the loss of control of the goods of the basilicas founded by laymen, since they were fraudulently trying to pass these foundations off as monasteries. The case of the designation of Valerius of Bierzo (under episcopal confirmation) as priest of the Church of Ricimiro in Ebronauto, upon the proposal of the landowner himself, is one of the most symptomatic cases of the control which private individuals could exercise over their private churches (Ordo Quer. 10). On this subject, although oriented towards rural properties, see (Díaz Martínez 1986, p. 300; Fernández 2016, pp. 536–37; Fiocchi Nicolai 2017, pp. 218–22). |

| 16 | Sulpicius Severus (Chron. 1.23; 2.32 and 51) castigated the power struggles between bishops and urban ecclesiastical factions, which were partly responsible for his monastic retreat to his villa in Primuliacum. |

| 17 | On this concept, which seeks to define political and social interactions as a combination of cooperation and confrontation, see (Brandenburger and Nalebuff 1996). |

| 18 | Particularly noteworthy is the epitaph of Thecla, an elderly “virgin” from Egypt, who was buried in this complex (CIL II/2 14 2150). |

| 19 | This must be the complex that appears in Letter 11 of Consentius to St. Augustine, which had a church and a secretarium (Aug. Ep. 291, 9). This letter also alludes to the existence of a monastery in the city founded by Fronton at the beginning of the fifth century, although, as Arce points out, it would have been a simple cell where Fronton, in extreme poverty, would have lived in isolation (Arce 2005, p. 224). |

| 20 | Prud. Perist. 6.122–135, if this is the place to which Prudentius refers, as (Pérez Martínez 2019, pp. 50–51) suggests. |

| 21 | On the embellishment of the martyrial churches of Rome by wealthy laymen and various members of the ecclesiastical hierarchy to obtain privileged burial spaces, see (Spera 2012, pp. 42–45; Luciano 2021, pp. 89–90, 96–101). |

| 22 | For an architectural description of the basilica of the amphitheatre, see (Guidi 2010; Muñoz 2016, pp. 113–24). |

| 23 | On the boom experienced by the Tarraco episcopal see in the second half of the sixth century as a result of local economic prosperity, see (Pérez Martínez 2005, pp. 272–343; Muñoz 2016, pp. 107–13). On the Orationale Visigothicum and its influence on the development of the martyr cult and processional liturgy in Tarraco, see (Godoy and Muñoz 2019). |

| 24 | Vilella (n.d.), http://dbe.rah.es/biografias/17154/paciano (last consulted on 2 March 2023). Pacianus was the father of Nummius Aemilianus Dexter, who held the position of proconsul of Asia (379–387) and prefect of the praetorium of Italy (395). |

| 25 | The case may have similarities with the property donation received by Amatus, bishop of Auxerre, at the end of the sixth century from the vir clarissimus Ruptilius for the construction of a new cathedral at the town’s hearth (Vita Amat. 3.18–21). |

| 26 | On the role of the baths as places of social encounter and as spaces of religious experience, see (Steuernagel 2020). Cf., also Urciuoli’s reflections on the advantageous location chosen by Justin, who established his domestic school on top of one of the baths at Rome, (Urciuoli 2020, pp. 71–76). |

| 27 | According to (Beltrán de Heredia 2018b, pp. 21–22), the complex was built upon a temple from the early imperial period. However, the remains—the angle of a possible podium—are not clearly identifiable with those of a temple, nor does the stratigraphic sequence support the interpretation of a conversion of the building, as there is a gap of almost a century between the abandonment of the space found under the basilica and the construction of the church at the beginning of the sixth century. |

| 28 | On the possible causes of this destruction, see (Arce 2011, p. 498; Mateos 2018, p. 140). |

| 29 | (Poveda Arias 2023a) has also recently applied this concept to illustrate the power dynamics between lay elites and ecclesiastical authorities in the cities of the Visigothic kingdom. |

| 30 | On the implications of this conflict, see recent work by (Grotherr 2023). |

| 31 | Indeed, after the death of Liuvigild, when Masona returned from exile imposed by the crown, a section of the city’s lay elite, led by Bishop Sunna and some nobles such as Witteric, hatched a conspiracy against Masona and the Nicene policy of Reccared (VSPE, V. 10–11). |

| 32 | On the use of the term “urban aspirations” as applied to the religious attitudes of different groups and actors living together in a city, see (Rüpke 2020, pp. 99–100). |

| 33 | On this process, which shares close parallels with certain regions of Gaul, see (Loseby 2006, pp. 79–83; Lewis 2021, pp. 237–39). |

References

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

- Andreu Pintado, Javier. 2019. Challenges and Threats Faced by Municipal Administration in the Roman West during the High Empire: The Hispanic case. In Signs of Weakness and Crisis in the Western Cities of the Roman Empire (c. ii-iii AD). Postdamer Altertumswissenschaftliche Beiträge, 68. Edited by Javier Andreu Pintado and Aitor Blanco Pérez. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, pp. 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Arbeiter, Achim. 2006. Grabmosaiken in Hispanien. Römische Quartalschrift für Christliche Altertumskunde und Kirchengeschichte 101: 260–88. [Google Scholar]

- Arce, Javier. 2005. Bárbaros y Romanos en Hispania. Madrid: Marcial Pons Historia. [Google Scholar]

- Arce, Javier. 2011. Augusta Emerita: Continuidad y transformación (ss. IV–VII). In Actas Congreso Internacional 1910–2010: El Yacimiento Emeritense. Edited by José María Álvarez Martínez and Pedro Mateos Cruz. Mérida: Ayuntamiento de Mérida, pp. 491–504. [Google Scholar]

- Arce, Javier. 2018. De la ciudad pagana a la ciudad cristiana: El caso de Hispania (siglos iv-vi). In Entre Civitas y Madina. El mundo de las Ciudades en la Península Ibérica y el Norte de África (siglos iv-ix). Collection de la Casa de Velázquez, 167. Edited by Sabine Panzram and Laurent Callegarin. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez, pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Baratte, François, Fathi Bejaoui, Noël Duval, Sarah Berraho, Isabelle Gui, and Hélène Jacquest. 2014. Basiliques Chrétienes d’Afrique du Nord II. Monuments de la Tunisie. Bordeaux: Ausonius. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán de Heredia, Julia, and Charles Bonnet. 2005. Arqueología y arquitectura de los siglos VI–VII en Barcelona: La reforma y monumentalización del grupo episcopal. In Guerra y Rebelión en la Antigüedad Tardía. El Siglo VII en España y su Contexto Mediterráneo. Edited by Luis A. García Moreno and Sebastián Rascón Marqués. Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, pp. 155–80. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán de Heredia, Julia. 2001. De Barcino a Barcinona (Siglos I–VII). Los Restos Arqueologicos de la Plaza de Rey de Barcelona. Barcelona: MHCB-Ayuntamiento de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán de Heredia, Julia. 2010. La cristianización del suburbium de Barcino. In Las Áreas Suburbanas en la Ciudad Histórica. Topografía, Usos y Función. Monografías de Arqueología Cordobesa 18. Edited by Desiderio Vaquerizo. Córdoba: Universidad de Córdoba, pp. 363–96. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán de Heredia, Julia. 2013. Barcino. De colònia romana a sede regia visigoda, medina islàmica i ciutat comtal: Una urbs en transformació. Quarhis 9: 16–118. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán de Heredia, Julia. 2018a. Barcelona, la topografía de un centro de poder visigodo: Católicos y arrianos a través de la arqueología. In Territorio, Topografía y Arquitectura de Poder Durante la Antigüedad Tardía. Edited by Isabel Sánchez Ramos and Pedro Mateos Cruz. Mérida: Instituto de Arqueología de Mérida, pp. 79–125. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán de Heredia, Julia. 2018b. Origen y Antigüedad de la basílica de los Santos Justo y Pastor: El complejo cristiano del siglo VI y su precedente pagano. In Patrimoni, Arqueología i art a la Basílica dels Sants Màrtirs Just i Pastor. Studia Historica Tarraconensia 8. Edited by Julia Beltrán de Heredia. Barcelona: Ateneu Universitari Sant Pacià, pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bowes, Kim. 2008. Private Worship, Public Values, and Religious Change in Late Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburger, Adam M., and Barry J. Nalebuff. 1996. Co-Opetition. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer, Jan N. 2020. Urban Religion, Neighbourhoods and the Early Christian Meeting Places. Religion in the Roman Empire 6: 48–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Peter. 1995. Authority and the Sacred. Aspects of the Christianisation of the Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Peter. 2012. Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350–550 AD. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buenacasa, Carles. 2004. La creación del patrimonio eclesiástico de las iglesias norteafricanas en época romana (siglos II–V): Renovación de la visión tradicional. Antigüedad y Cristianismo 21: 500–9. [Google Scholar]

- Busine, Aude. 2015. Religious Practices and Christianisation in Late Anitiquity. In Religious Practices and Christianization of the Late Antique City (4th–7th Cent.). Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 182. Edited by Aude Busine. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chavarría, Alexandra. 2010. Suburbio, Iglesias y obispos. Sobre la errónea ubicación de algunos complejos episcopales en la Hispania tardoantigua. Monografías de Arqueología Cordobesa 18: 435–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dagron, Gilbert. 1989. Les sanctuaires et l’organisation de la vie religieuse a Constantinople. In Actes du Xle Congres International d’ Archeologie Chretienne, Lyon, Vienne, Grenoble, Geneve et Aoste. Publications de l’École française de Rome, 123. Roma: École Française de Rome, vol. 2, pp. 1069–85. [Google Scholar]

- Diarte-Blasco, Pilar. 2013. The creation of Christian urban landscapes in Hispania: A rather late development. In The Theodosian Age (A.D. 379–455): Power, Place, Belief and Learning at the End of the Western Empire. Edited by Rosa García-Gasco, Sergio González Sánchez and David Hernández de la Fuente. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Diarte-Blasco, Pilar. 2020. Actores principales y secundarios: Los agentes transformadores del modelo urbano en la Hispania tardoantigua y altomedieval. In Urban Transformations in the Late Antique West. Materials, Agents and Models. Edited by André Carneiro, Neil Christie and Pilar Diarte-Blasco. Coimbra: Coimbra University Press, pp. 351–79. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Martínez, Pablo de la Cruz. 1986. Iglesia propia y gran propiedad en la autobiografía de Valerio del Bierzo. In Actas I Congreso Internacional Astorga Romana. Astorga: Ayuntamiento de Astorga, vol. 1, pp. 297–303. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Damián. 2016. Property, Social Status and Church Building in Visigothic Iberia. Journal of Late Antiquity 9: 512–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiocchi Nicolai, Vincenzo. 2007. Il ruolo dell’evergetismo aristocratico nella construzione degli edifici di culti cristiani nell’hinterland di Roma. In Archeologia e Società tra Tardo Antico e Alto Medioevo. Edited by Gian Pietro Brogiolo and Alexandra Chavarría Arnau. Mantova: SAP, pp. 107–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fiocchi Nicolai, Vincenzo. 2017. Le chiese rurale di committenza privata e il loro uso pubblico. Rivista di Archeologia Cristiana 93: 203–47. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy, Cristina. 2013. L’arquitectura cristiana a Tàrraco: Ritus i litúrgia. In Tarraco Christiana Civitas. Edited by Josep María Macias and Andreu Muñoz. Tarragona: Institut Català d’Arqueologia Clàssica, pp. 163–80. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy, Cristina, and Andreu Muñoz. 2019. La basílica del anfiteatro, el oracional de Verona y el culto a los mártires Fructuoso, Augurio y Eulogio del siglo VII. In Tarraco Biennal. Actes 4t Congrés Internacional d’Arqueologia i Món Antic. VII Reunió d’Arqueologia Cristiana Hispànica. El cristianisme en l’Antiguitat Tardana. Noves Perspectives. Edited by Jordi López Vilar. Tarragona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Pallarés, Joan. 2002. Poesía Epigráfica Llatina als Països Catalans. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Grotherr, Kevin. 2023. Between Royal Power and Legitimacy—The Bishops of Mérida (6th–7th c.). In Bishops under Threat. Contexts and Episcopal Strategies in the Late Antique and Early Medieval West. Edited by Sabine Panzram and Pablo Poveda. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, Isabelle, Noël Duval, and Jean Pierre Caillet. 1992. Basiliques Chrétienes d’Afrique du Nord I. Inventaire de L’Algérie. Paris: Institut d’Études Augustiniennes. [Google Scholar]

- Guidi, José Javier. 2010. Spolia et Varietas, la construcción de los complejos cristianos de Tarraco. El caso de la basílica del Anfiteatro. In Tarraco: Construcció i Arquitectura d’una Capital Provincial Romana. Congrés Internacional en Homenatge a Th. Hauschild. Butlletí Arqueològic V, 32. Edited by Jordi López Vilar and Oscar Martín. Tarragona: Reial Societat Arqueológica Tarraconense, pp. 757–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kulikowski, Michael. 2004. Late Roman Spain and Its Cities. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lander, Shira L. 2017. Ritual Sites and Religious Rivalry in Late Roman North Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, Anna. 2007. Changing Townscapes in North Africa from Late Antiquity to the Arab Conquest. Bari: Edipuglia. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Joe. 2021. Christian Building Patronage in the Cities of Late Antique and Merovingian Gaul, c. 300–751. Ph.D. thesis, Balliol College, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- López-Gómez, José Carlos. 2021. El Ocaso de los Dioses en Hispania: Transformaciones Religiosas en el Siglo III. Anejos de AEspA 91. Madrid: CSIC. [Google Scholar]

- López-Gómez, José Carlos, and Jaime Alvar. 2021. Hacia un cambio de paradigma: Manifestaciones religiosas en la Hispania del siglo III. Hispania Sacra 73: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Vilar, Jordi. 2006. Les Basíliques Paleocristianes del Suburbi Occidental de Tarraco: El Temple Septentrional i el Complex Martirial de Sant Fructuós. 2 vols. Documenta 4. Tarragona: Institut Català d’Arqueologia Clàssica. [Google Scholar]

- López Vilar, Jordi, and Andreu Muñoz. 2019. L’arqueologia Cristiana de Tarragona. Balanç dels darrers 25 anys (1993–2018). In Tarraco Biennal. Actes 4t Congrés Internacional d’Arqueologia i Món Antic. VII Reunió d’Arqueologia Cristiana Hispànica. El cristianisme en l’Antiguitat Tardana. Noves Perspectives. Edited by Jordi López Vilar. Tarragona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, pp. 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- López Vilar, Jordi, Josep María Macias, and Andreu Muñoz. 2016. El cementiri i la basílica de Tarragona. In L’arquitectura Cristiana Preromànica a Catalunya. Edició Facsímil i Textos D’actualització. Edited by Josep Puig i Cadafalch, Antoni de Falguera and Josep Goday. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans, pp. 429–46. [Google Scholar]

- Loseby, Simon T. 2006. Decline and Change in the Cities of Late Antique Gaul. In Die Stadt in der Spätantike—Niedergang oder Wandel? Edited by Jens-Uwe Krause and Christian Witschel. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, pp. 67–104. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano, Alessandro. 2021. Santuari e Spazi Confessionali nell’Italia Tardoantica. Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- MacMullen, Ramsey. 2009. The Second Church: Popular Christianity. A.D. 200–400. Writings from the Greco-Roman World Supplements 1. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. [Google Scholar]

- Marrou, H. Irénée. 1970. Le dossier épigraphique de l’évêque Rusticus de Narbonne. Rivista di Archeologia Cristiana 46: 331–49. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Maza, Clelia. 2021. Lived Ancient Religion: Una nueva herramienta teórica para el estudio de los espacios rurales cristianos de la Hispania tardo-antigua (ss. IV–V). Hispania Sacra 73: 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, Pedro. 1999. La Basílica de Santa Eulalia de Mérida. Anejos de AEspA 19. Madrid: CSIC. [Google Scholar]

- Mateos, Pedro. 2018. De capital de la Diocesis Hispaniarum a sede temporal de la monarquía sueva. La transformación del urbanismo en Augusta Emerita durante los siglos IV y V. In Territorio, Topografía y Arquitectura de Poder Durante la Antigüedad Tardía. Edited by Isabel Sánchez Ramos and Pedro Mateos Cruz. Mérida: Instituto de Arqueología de Mérida, pp. 127–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mateos, Pedro, and Luis Caballero. 2011. El paisaje urbano de Augusta Emerita en época tardoantigua (siglos IV–VII). In Actas Congreso Internacional 1910–2010: El Yacimiento Emeritense. Edited by José María Álvarez Martínez and Pedro Mateos Cruz. Mérida: Ayuntamiento de Mérida, pp. 505–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mathisen, Ralph W. 1997. Barbarian Bishops and the Churches in barbaricis gentibus during Late Antiquity. Speculum 72: 664–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Andreu. 2016. La basílica visigótica del anfiteatro de Tarragona: Definición, técnicas constructivas y simbología de un templo martirial. Quarhis 12: 106–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Martínez, Meritxell. 2005. Tarraco Christiana. Cristianización y Organización Eclesiástica de una Capital Provincial Romana (siglos III al VII). Ph.D. thesis, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Martínez, Meritxell. 2019. Loca sanctorum Tarraconis. Els escenaris del culte als sants en la Tarraco de l’Antiguitat tardana (ss. IV al VIII). In Tarraco Biennal. Actes 4t Congrés Internacional d’Arqueologia i Món Antic. VII Reunió d’Arqueologia Cristiana Hispànica. El cristianisme en l’Antiguitat Tardana. Noves Perspectives. Edited by Jordi López Vilar. Tarragona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Martínez, Meritxell. 2023. Constructing New Leaders. Bishops in Visigothic Hispania Tarraconensis (Fifth to Seventh Centuries). In Leadership, Social Cohesion, and Identity in Late Antique Spain and Gaul (500–700). Late Antique and Early Medieval Iberia 11. Edited by Fernando Ruchesi and Dolores Castro. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 131–58. [Google Scholar]

- Poveda Arias, Pablo. 2018. Monarquía, Sociedad y Territorio en el Occidente Post-Imperial: Construcción de la Soberanía Regia en la Galia Merovingia y en el Reino Visigodo Hispano. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Poveda Arias, Pablo. 2023a. Coexisting Leadership in the Visigothic Cities. A coopetitive model. In Leadership, Social Cohesion, and Identity in Late Antique Spain and Gaul (500–700). Late Antique and Early Medieval Iberia 11. Edited by Fernando Ruchesi and Dolores Castro. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 159–84. [Google Scholar]

- Poveda Arias, Pablo. 2023b. Making loca sacra in Visigothic Iberia: The Case of Churches. Religions 14: 664. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/14/5/664 (accessed on 24 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Remolà, Josep Anton, and Ada Lasheras. 2019. Ad Suburbium Tarraconis. Del área portuaria al conjunto eclesiástico del Francolì. In Tarraco Biennal. Actes 4t Congrés Internacional d’Arqueologia i Món Antic. VII Reunió d’Arqueologia Cristiana Hispànica. El Cristianisme en l’Antiguitat Tardana. Noves Perspectives. Edited by Jordi López Vilar. Tarragona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, pp. 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ripoll, Gisella, and Javier Arce. 2015. De los cultos paganos al culto cristiano: El proceso de transformación en Hispania (siglos IV–VII). In Des Dieux Civiques aux Saints Patrons (IVe–VIIe Siècle), Textes. Edited by Jean-Pierre Caillet, Sylvain Destephen, Bruno Dumézil and Hervé Inglebert. Paris: Editions A. et J. Picard, pp. 341–51. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Vera, Diego. 2020. Acerca del inicio de la crisis urbana y municipal en la Hispania de época antonina. Revista de Historiografía 33: 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüpke, Jörg. 2018. Pantheon. A New History of Roman Religion. Translated by David Richardson. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rüpke, Jörg. 2020. Urban Religion. A Historical Approach to Urban Growth and Religious Change. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Salom, Cristòfor. 2019. El conjunt eclesiàstic de Tarragona. In Tarraco Biennal. Actes 4t Congrés Internacional d’Arqueologia i Món Antic. VII Reunió d’Arqueologia Cristiana Hispànica. El Cristianisme en l’Antiguitat Tardana. Noves Perspectives. Edited by Jordi López Vilar. Tarragona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, pp. 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sastre de Diego, Isaac. 2011. El cristianismo en la Mérida romana y visigoda. Evidencias arqueológicas y fuentes escritas. In Actas Congreso Internacional 1910–2010. El Yacimiento Emeritense. Edited by José María Álvarez and Pedro Mateos. Mérida: Ayuntamiento de Mérida, pp. 563–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sotinel, Claire. 2005a. Lieux de culte et sanctuaires dans le christianisme ancien. Enquête Bibliographique. Revue de L’histoire des Religions 222: 411–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotinel, Claire. 2005b. Identité Civique et Christianisme: Aquilée du IIIe au VIe Siècle. Bibliothèque des Écoles françaises d’Athènes et de Rome 324. Rome: École Française de Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Spera, Lucrezia. 2012. I santuari di Roma dell’antichità all altomedioevo: Morfologie, caraterri dislocativi, riflessa della devozione. In I Santuari d’Italia. Roma. Edited by Sofia Boesch Gajano, Tommaso Caliò, Francesco Scorza Barcellona and Lucrezia Spera. Roma: De Luca Editori d’Arte, pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Steuernagel, Dirk. 2020. Roman baths as locations of religious practice. In Urban Religion in Late Antiquity. Edited by Asuman Lätzer-Lasar and Emiliano R. Urciuoli. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 225–59. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Edward A. 1960. The Conversion of the Visigoths to Catholicism. Nottingham Medieval Studies 4: 4–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urciuoli, Emiliano R. 2020. La Religione Urbana. Come la Città ha Prodotto il Cristianesimo. Bologna: EDB. [Google Scholar]

- Urciuoli, Emiliano R., and Jörg Rüpke. 2018. Urban Religion in Mediterranean Antiquity. Relocating Religious Change. Mythos 12: 117–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilella, Josep. n.d. Paciano. Diccionario Biográfico Español de la Real Academia de la Historia. Available online: http://dbe.rah.es/biografias/17154/paciano (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Vives, José. 1963. Concilios Visigóticos e Hispano-Romanos. Barcelona and Madrid: CSIC. [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Perkins, Bryan. 1984. From Classical Antiquity to the Middle Ages: Urban Public Building in Northern and Central Italy, AD 300–850. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Ian. 1983. The Ecclesiastical Politics of Merovingian Clermont. In Ideal and Reality in Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Society. Edited by Patrick Wormald. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, pp. 34–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Ian. 2022. The Christian Economy in the Early Medieval West, Towards a Temple Society. Santa Barbara: Punctum Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Susan. 2006. The Proprietary Church in the Medieval West. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Gómez, J.C. Shaping Urban Religious Topography in the Iberian Peninsula between the Fourth and Sixth Centuries: “Coopetitive” Rivalry and Social Power. Religions 2023, 14, 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091124

López-Gómez JC. Shaping Urban Religious Topography in the Iberian Peninsula between the Fourth and Sixth Centuries: “Coopetitive” Rivalry and Social Power. Religions. 2023; 14(9):1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091124

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Gómez, José Carlos. 2023. "Shaping Urban Religious Topography in the Iberian Peninsula between the Fourth and Sixth Centuries: “Coopetitive” Rivalry and Social Power" Religions 14, no. 9: 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091124

APA StyleLópez-Gómez, J. C. (2023). Shaping Urban Religious Topography in the Iberian Peninsula between the Fourth and Sixth Centuries: “Coopetitive” Rivalry and Social Power. Religions, 14(9), 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091124