Ribât in Early Islamic Ifrîqiya: Another Islam from the Edge

Abstract

:1. Introduction1

2. Part I. A Historiography Undergoing a Major Renewal

2.1. Milestones for a Historiography of the Institution of Ribât in Medieval Ifrîqiya

2.2. The Institution of Ribât in Ifrîqiya According to Recent Historiography

3. Part II. The Formation of a Frontier Society

3.1. The Frontier as a Common Horizon

3.2. The Ifrîqiyan Version of the Ascetic Warrior

3.3. The Importance of Land Tenure

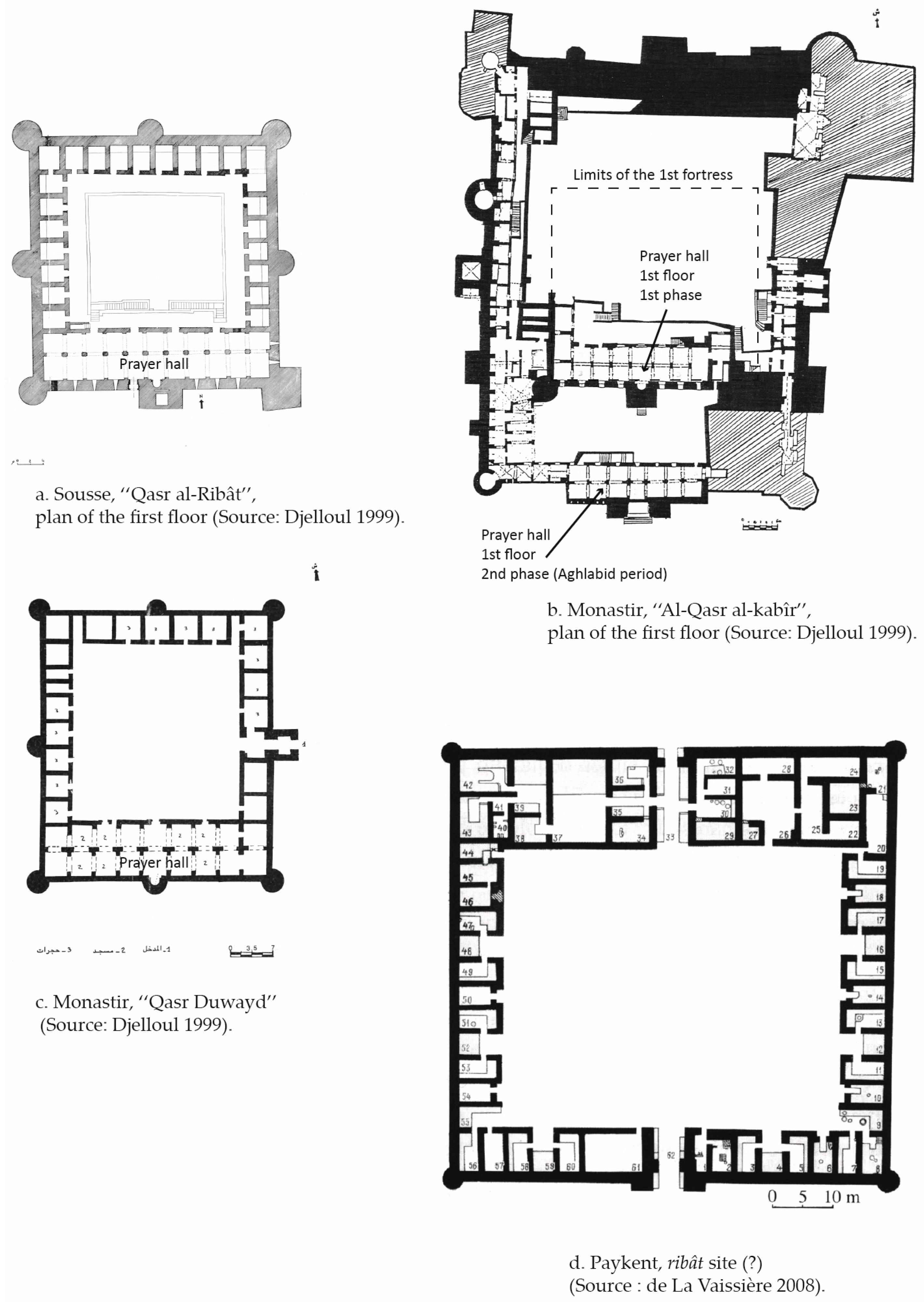

4. Part III. The Ribât Site: Building Context and Architectural Specificities

4.1. The Modalities of Building Patronage

4.2. A Specific Place at the Core of the Monument: The Mosque

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This research could not have been carried out without the impressive work done over the last decades by Tunisian colleagues and friends (N. Amri, F. Bahri, M. Chapoutot-Remadi, N. Djelloul, A. El Bahi, M. Hassen, F. Mahfoudh, R. M’rabet, C. Touihri), which constitutes the primary source of inspiration for my reflections: I would like to express my sincere thanks to them all. This article is also dedicated to my colleague and friend C. Picard; circumstances have deprived me of his precious advice. Finally, I would like to thank A. Prieto for his helpful and careful proofreading of the english version of this paper. |

| 2 | In order to ensure clarity, Arabic terms are transliterated here in a very simplified form. Similarly, dates are provided only according to the Gregorian calendar. |

| 3 | The quotation marks are placed here to respect the later designation of these buildings, which is in common use in Arabic today, while noting that this practice does not correspond to the meaning assigned to the word ribât during the period under study. |

| 4 | For this name, the initial Arabic definitive article al- (al-Qasr al-kabir) is omitted for convenience. |

| 5 | For textual analysis, see, among others, Idris (1962, t. I pp. 688–92) and, on the Tunisian side, Abd al-Wahhâb (1981, vol. 2, pp. 13–50). The archaeological approach, the more developed in this first historiographical stage, first gave rise to general remarks (Marçais 1925, 1926, pp. 47–50), before concentrating notably on the study of the “Qasr al-Ribat” of Sousse (Creswell 1979, pp. 167–70; Lézine 1956, 1968, 1971, pp. 82–88). Lézine’s pioneering publication of 1956 remains the only monograph to date devoted to the archaeological study (in the full sense of the term) of a ribât site. |

| 6 | Given the small number of Western scholars who are actually aware of an Arabic-language historiographical tradition, the efforts made by some Tunisian historians over the last fifteen years to publish overviews of their work in French should be noted (Hassen 2001; Amri 2011; Djelloul 2011; El Bahi 2018). However, the French language is in decline internationally and is no longer widely read in the Anglo-American world. The author modestly hopes that the present article, although limited in scope, will nonetheless stimulate further interest in the Tunisian bibliography. |

| 7 | For a more comprehensive overview on this issue, one may also refer now to the recent publication edited by Albarrán and Daza (2019). |

| 8 | Or even further: in this respect it is worth noting that, in the same period and a little later, the issue of the defence of the Syrian–Palestinian coastline has been the subject of a similar revival of interest (Khalilieh 1999; Masarwa 2006, 2011). |

| 9 | For other aspects of this historiographical assessment, now refer to Van Staëvel (2023). |

| 10 | As a matter of fact, several archaeological sites have been excavated but unfortunately not yet published (Mahfoudh 1999, p. 98). |

| 11 | After his victorious expedition in 779, Yahyâ b. Khâlid b. Barmak gained administrative control over Armenia, Azerbaijan and Ifriqiya; this was later confirmed in 785 (Bonner 1996, pp. 76, 144). |

| 12 | Tunisian historians emphasise the decisive role of Harthama b. A‘yân in the implementation of this new type of defensive warfare and connect it to the other regions where this high-ranking officer had stayed in an official capacity (Djelloul 1999, p. 200; El Bahi 2004, p. 578; El Bahi 2018, p. 329), but this contextualisation does not go further to consider Abbasid politics as a whole. |

| 13 | This point is also stressed by C. Picard and A. Borrut (Picard and Borrut 2003, p. 37; Picard 2015, pp. 100–1). |

| 14 | Chabbi (1995) provides a view of jihâd and ribât at the frontier of the Muslim world that differs considerably from the analysis provided by M. Bonner. C. E. Bosworth emphasises the importance of the institution of ribât, which is well-attested in the sources for Tarsûs, but he draws a picture that is too general and universalist, from Central Asia to al-Andalus (Bosworth 1992, pp. 284–85). |

| 15 | The semantic ambiguity and the silence of the texts thus explain why the institution of ribât and its role in the mobilisation of the defenders of the faith on the northern frontier have not received much attention from Bonner: in his book, the subject index does not even include an entry for the terms murâbit and ribât (Bonner 1996, p. 220). |

| 16 | Starting at the end of the 8th century, the Central Asian frontier seems to show a very different situation, with ribât settlements serving above all to accommodate a class of landowners who were able to bear arms and defend their territory against the Turks. The disagreement between the members of this landed warrior aristocracy and the ascetic scholars leads to the departure of the latter for the Arab–Byzantine frontier in the Near East (Bonner 1996, pp. 108–9, 139). |

| 17 | |

| 18 | Even if this opposition has probably been overstated for the Aghlabid period (Van Staëvel 2023, pp. 295–99). |

| 19 | The positions of C. Martínez Salvador (Martínez Salvador 1998, p. 267) and this author (Van Staëvel 2023) differ significantly from this common position in their reassertion of the role of state authority. The former, however, defends the hypothesis of a Muhallabid, and not an Aghlabid, origin of the main Tunisian fortresses. |

| 20 | In the following discussion, the focus is of course on the original architectural design of these monuments, leaving aside any later additions that may have obliterated all or part of the choices of design and layout made at the time of the foundation. |

| 21 | This applies to buildings founded during the Islamic period; Byzantine fortresses that were remodelled are not included in the analysis. |

| 22 | The excellent study proposed by Martínez Salvador (1998) does not dwell on this architectural specificity. |

| 23 | Some ribât sites seem to have assumed the basic form of a mosque (Djelloul 1999, p. 188). |

| 24 | The site of Las Dunas de Guardamar in Spain shows great consistency in its design of individual living spaces that also serve as places of devotion and are each equipped with a mihrab for that purpose. It includes also, however, an open-air oratory (musallâ), later turned into a proper building, which serves as a place of religious gathering (Azuar Ruiz 2004, pp. 26–27). In Igiliz, the ribât of the early Almohad period, no individual prayer space has been identified to date: the existence of a main place of worship, along with the small oratory located in the bailey of the Qasba, tends to emphasise a collective conception of prayer in this murâbitûn community (Ettahiri et al. 2013, pp. 1125–27). |

| 25 | The limited sample available to us obviously precludes the formulation of a general explanation for these undeniable similarities, at the risk of yielding to an overly simplistic diffusionism. |

| 26 | The other site excavated in Israel, Ha-Bonim/Kfar Lam, did not reveal a mosque (Raphael 2014, pp. 19, 21). |

| 27 | It is not known on what archaeological basis the building was identified as a ribât site. From a mere reading of its layout, it is indeed difficult to distinguish it from a caravanserai. |

| 28 | The hypothesis outlined here differs from that proposed by C. Martínez Salvador, who believes that the fortresses were initially built in the Muhallabid period to serve an administrative–military function and were subsequently transformed into ribât sites, namely by inserting a mosque into the preexisting buildings (Martínez Salvador 1998). |

| 29 | This unusual accommodation seems to have been in use only for a short period of time: a refurbishment, dating from the end of the 9th century at the latest, closed off the access (Lézine 1956, p. 18). |

| 30 | The erection of the watch-tower on the Sousse “Qasr al-Ribat” dates to the same year. |

| 31 | Another well-known mosque—that of Bû Futâta—was erected in 838 on the orders of Amir Abû ‘Iqâl. It does not seem to have served as a Friday mosque. |

| 32 | Picard and Borrut mention Lézine’s hypothesis, but they insist instead—probably wrongly, when one thinks of the defensive devices of the building—on the low initial military value of the “Qasr al-Ribat” (Picard and Borrut 2003, p. 38). |

| 33 | The problem of dating the small mosque at the foot of the “Qasr al-Kabir” is crucial here. Generally considered to be Aghlabid, it was rebuilt and extended by the Zirids in the 11th century. To our knowledge, no scientific excavation has ever been carried out there. |

References

Primary Sources

Mâlikî (al-). Kitâb Riyâd al-nufûs fî tabaqât ‘ulamâ’ al-Qayrawân wa Ifrîqiyya wa zuhhâdihim wa nussâkihim wa sayrun min akhbârihim wa fadâ’ilihim wa awsâfihim, éd. B. al-Bakkûsh et M. A. al-Matwî, Beyrouth, Dâr al-Gharb al-islâmî, 1994, 2 tomes.Secondary Sources

- Abd al-Wahhâb, Hasan Husnî. 1981. Waraqât, 3rd ed. 3 vols. Tunis: Maktabat al-Manâr. [Google Scholar]

- Albarrán, Javier, and Enrique Daza, eds. 2019. Fortificación, espiritualidad y frontera en el islam medieval: Ribâts de al-Andalus, el Magreb y más allá. Cuadernos de Arquitectura y Fortificación. Madrid: EDICIONES DE LA ERGÁSTULA, S.L., vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Amri, Nelly. 2001. Al-walāya wa-l-mujtamaʿ. Tunis: Faculté des Lettres de la Manouba. [Google Scholar]

- Amri, Nelly. 2011. Ribât et idéal de sainteté à Kairouan et sur le littoral ifrîqiyen du IIe/VIIIe au IVe/Xe siècle d’après le Riyâd al-nufûs d’al-Mâlikî. In Islamisation et arabisation de l’Occident musulman médiéval (VIIe–XIIe siècle). Edited by Dominique Valérian. Paris: Sorbonne, pp. 331–68. [Google Scholar]

- Azuar Ruiz, Rafael, ed. 2004. El ribât califal. Excavaciones e investigaciones (1984–1992). Madrid: Casa de Velázquez. [Google Scholar]

- Bahri, Fathi. 2003. Qasr al-‘Âliya (campagne de 1998). Rapport de fouille: 1ère partie. Africa 1: 31–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner, Michael. 1996. Aristocratic Violence and Holy War. Studies in the Jihad and the Arab-Byzantine Frontier. New Haven: American Oriental Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner, Michael. 2006. Jihad in Islamic History. Doctrines and Practice. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth, Edmund. 1992. Tarsus and the Arab-Byzantine Frontiers in Early and Middle ‘Abbâsid Times. Oriens 33: 268–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulliet, Richard W. 1994. Islam. The View From the Edge. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chabbi, Jacqueline. 1995. Ribāṭ. Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill, vol. VIII, pp. 493–506. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, Keppel A. C. 1979. Early Muslim Architecture. Vol. II: Early ‘Abbâsids, Umayyads of Cordova, Aghlabids, Tûlûnids and Samânids, A.D. 751–905. New York: Hacker Art Books. [Google Scholar]

- de La Vaissière, Etienne. 2008. Le Ribât d’Asie centrale. In Islamisation de l’Asie centrale. Processus locaux d’acculturation du VIIe au XIe siècle. Edited by Etienne de la Vaissière. Louvain: Peeters, pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Djelloul, Néji. 1999. Al-Ribâtât al-bahriyya bi-Ifrîqiya fī l-‘asr al-wasît. Tunis: Centre d’Études et de Recherches Économiques et Sociales. [Google Scholar]

- Djelloul, Néji. 2011. La voile et l’épée. Les côtes du Maghreb à l’époque médiévale. 2 vols. Tunis: Faculté de la Manouba. [Google Scholar]

- Eger, Asa E. 2012. Hisn, Ribât, Thaghr or Qaṣr? Semantics and Systems of Frontier Fortifications in the Early Islamic Period. In The Lineaments of Islam. Studies in Honor of Fred McGraw Donner. Edited by Paul Cobb. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 427–55. [Google Scholar]

- Eger, Asa A. 2015. The Islamic-Byzantine Frontier. Interaction and Exchange among Muslim and Christian Communities. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Ehinger, Jessica. 2019. The Ghâzî Movement Performative Religious Identity on the Byzantine-Islamic Frontier. In From Antiquity to Islam in the Mediterranean and Near East (6th–10th Century). Edited by Alain Delattre, Marie Legendre and Petra M. Sijpesteijn. Leyde: Brill, pp. 265–83. [Google Scholar]

- El Bahi, Ahmed. 2004. Sūsa wa al-Sāḥil fī al-‘ahd al-wasīt: Muhāwala fī al-ğuġrāfiyā al-tārīkhiyya. Tunis: Centre de Publication Universitaire. [Google Scholar]

- El Bahi, Ahmed. 2018. Les ribāṭ-s aghlabides: Un problème d’identification. In The Aghlabids and Their Neighbours. Art and Material Culture in 9th-Century North Africa. Edited by Glaire D. Anderson, Corisande Fenwick and Mariam Rosser-Bowen. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 321–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ettahiri, Ahmed S., Abdallah Fili, and Jean-Pierre Van Staëvel. 2013. Nouvelles recherches archéologiques sur les origines de l’Empire almohade au Maroc: Les fouilles d’Igîlîz. Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 157: 1109–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, Mohamed. 1999. Al-Madīna wa-l-bādiya bi-Ifrīqiya fī l-ʿasr al-ḥafṣī. 2 vols. Tunis: Faculté des Sciences Humaines et Sociales. [Google Scholar]

- Hassen, Mohamed. 2001. Les ribāṭ du Sahel d’Ifrîqiya. Peuplement et évolution du territoire au Moyen Âge. In Castrum 7. Zones côtières littorales dans le monde méditerranéen au Moyen Âge. Edited by Jean-Marie Martin. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez, pp. 148–62. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, Hady Roger. 1962. La Berbérie orientale sous les Zirides, Xe-XIIe siècles. 2 vols. Paris: A. Maisonneuve. [Google Scholar]

- Khalilieh, Hassan S. 1999. The Ribât System and its Role in Coastal Navigation. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 42: 212–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilieh, Hassan S. 2008. The Ribât of Arsūf and Coastal Defence System in Early Islamic Palestine. Journal of Islamic Studies 19: 159–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagardère, Vincent. 1995. Histoire et société en Occident musulman au Moyen Âge. Analyse du Miʿyâr d’al-Wansharîsî. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez. [Google Scholar]

- Lézine, Alexandre. 1956. Le ribat de Sousse, suivi de notes sur le ribat de Monastir. Tunis: Direction des Antiquités et Arts de Tunisie. [Google Scholar]

- Lézine, Alexandre. 1968. Sousse, les Monuments Musulmans. Tunis: Ceres. [Google Scholar]

- Lézine, Alexandre. 1971. Deux villes d’Ifriqiya. Paris: Geuthner. [Google Scholar]

- M’rabet, Riyad. 1988. Al-Ribât wa mujtama’ al-murâbitîn bi-Ifrîqiya ilâ nihâyat al-qarn al-thâlith. Certificat d’aptitude à la recherche. Tunis: Université de Tunis, I, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Mahfoudh, Faouzi. 1999. Qasr al-Tûb: Un ribat du Sahel tunisien. Cadre géographique et historique. Africa 17: 97–127. [Google Scholar]

- Marçais, Georges. 1925. Note sur les ribâts en Berbérie. In Mélanges René Basset, t. II: Etudes nord-africaines et orientales. Paris: Leroux. [Google Scholar]

- Marçais, Georges. 1926. Manuel d’art musulman. L’architecture (Tunisie, Algérie, Maroc, Espagne, Sicile). 2 vols. Paris: Picard. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Salvador, Carmen. 1998. Arquitectura del ribat en el Sahel tunecino. Modelo y evolución. Anales de Murcia 13–14: 251–69. [Google Scholar]

- Masarwa, Yumna. 2006. From a Word of God to Archaeological Monuments: A Historical-Archaeological Study of the Umayyad Ribâts of Palestine. Ph.D. thesis, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Masarwa, Yumna. 2011. The Mediterranean as Frontier: The Umayyad Ribâts of Palestine. In Western Monasticism Ante Litteram: The Spaces of Monastic Observance in the Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Edited by Hendrik Dey and Elizabeth Fentress. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 177–99. [Google Scholar]

- Nef, Annliese. 2021. Révolutions islamiques. Emergences de l’Islam en Méditerranée (VIIe-Xe siècle). Rome: Ecole Française de Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, Christophe. 2011. Les Ribâts au Portugal à l’époque musulmane: Sources et définitions. In Mil Anos de Fortificações na Península Ibérica e no Magreb (500–1500), Actas do Simpósio Internacional sobre Castelos 2000. Edited by Isabella Cristina Ferreira Fernandes. Lisbon: Edições Colibrí y Câmara Municipal de Palmela, pp. 203–12. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, Christophe. 2015. La mer des califes. Une histoire de la Méditerranée musulmane. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, Christophe, and Antoine Borrut. 2003. Râbata, Ribât, Râbita: Une institution à reconsidérer. In Chrétiens et musulmans en Méditerranée médiévale (VIIIe-XIIIe siècle). Echanges et contacts. Edited by Nicolas Prouteau and Philippe Sénac. Poitiers: Université de Poitiers, pp. 34–65. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael, Sarah Kate. 2014. Azdud (Ashdod-Yam). An Early Islamic Fortress on the Mediterranean Coast. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Sahner, Christian C. 2017. “The Monasticism of My Community is Jihad”: A Debate on Asceticism, Sex, and Warfare in Early Islam. Arabica 64: 149–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizgorich, Thomas. 2009. Violence and Belief in Late Antiquity. Militant Devotion in Christianity and Islam. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- Talbi, Mohamed. 1966. L’émirat aghlabide, 184-296/800-909. Histoire Politique. Paris: Adrien-Maisonneuve. [Google Scholar]

- Van Staëvel, Jean-Pierre. 2022. Echoes of Empire. Building Materials and Technical Systems in Ifrîqiya in Aghlabid and Fatimid Times (9th–10th Centuries). In Building between Eastern and Western Mediterranean Lands. Construction Processes and Transmission of Knowledge from Late Antiquity to Early Islam. Edited by Piero Gilento. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 201–24. [Google Scholar]

- Van Staëvel, Jean-Pierre. 2023. La dévotion avec la mer pour horizon. Fragments de la vie quotidienne dans les lieux de ribât du littoral ifrîqiyen entre la fin du IIe/VIIIe siècle et le milieu du VIe-XIIe siècle. In Mers et rivages d’Islam, de l’Atlantique à la Méditerranée. Mélanges offerts à Christophe Picard. Edited by Alexandra Bill, Antoine Borrut, Yann Dejugnat, Camille Rhoné-Queré and Jennifer Vanz. Paris: Editions de la Sorbonne, pp. 289–317. [Google Scholar]

- Van Staëvel, Jean-Pierre, and Abdallah Fili. 2006. Wa-wasalnâ ‘alâ barakat Allâh ilâ Îgîlîz: À propos de la localisation d’Îgîlîz-des-Hargha, le hisn du Mahdî Ibn Tûmart. Al-Qantara XVII: 153–94. [Google Scholar]

- Varela Gomes, Rosa, and Mário Varela Gomes. 2004. O Ribat da Arrifana (Aljezur-Algarve). Aljezur: Municipío de Aljezur. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Van Staëvel, J.-P. Ribât in Early Islamic Ifrîqiya: Another Islam from the Edge. Religions 2023, 14, 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081051

Van Staëvel J-P. Ribât in Early Islamic Ifrîqiya: Another Islam from the Edge. Religions. 2023; 14(8):1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081051

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Staëvel, Jean-Pierre. 2023. "Ribât in Early Islamic Ifrîqiya: Another Islam from the Edge" Religions 14, no. 8: 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081051

APA StyleVan Staëvel, J.-P. (2023). Ribât in Early Islamic Ifrîqiya: Another Islam from the Edge. Religions, 14(8), 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081051