Transforming Inner Alchemical Vision into Painting: Huang Gongwang’s Clearing after Sudden Snow

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Huang Gongwang and His Inner Alchemy Practice

3. Current Research on Huang Gongwang’s Inner Alchemical Landscape Paintings

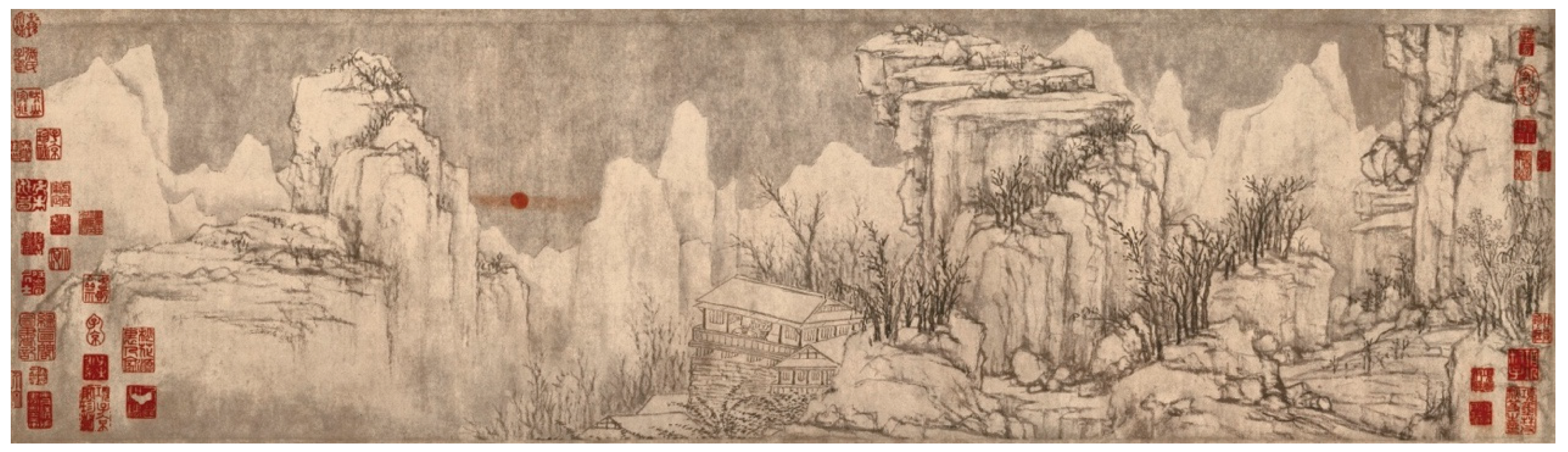

4. Clearing after Sudden Snow: The Resurgence of the Yang Force

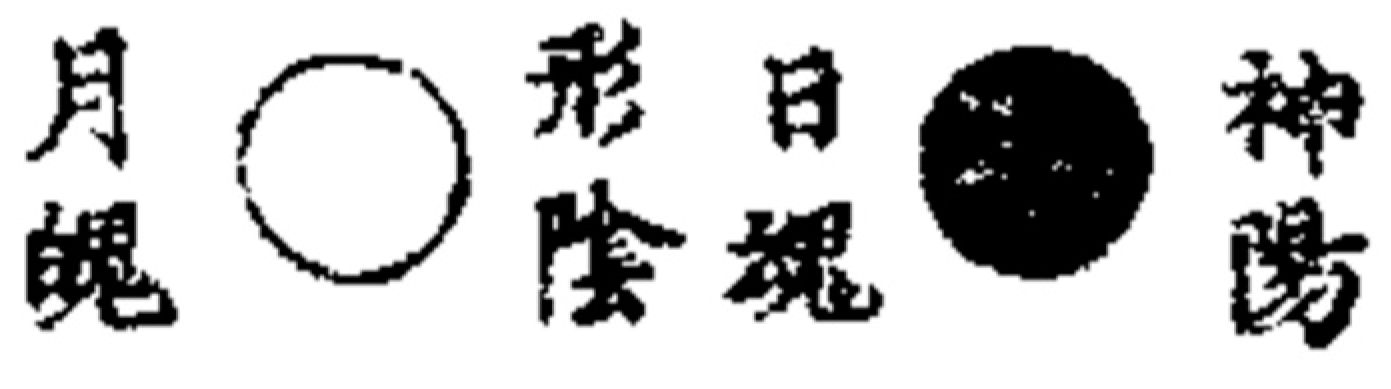

4.1. The Sun

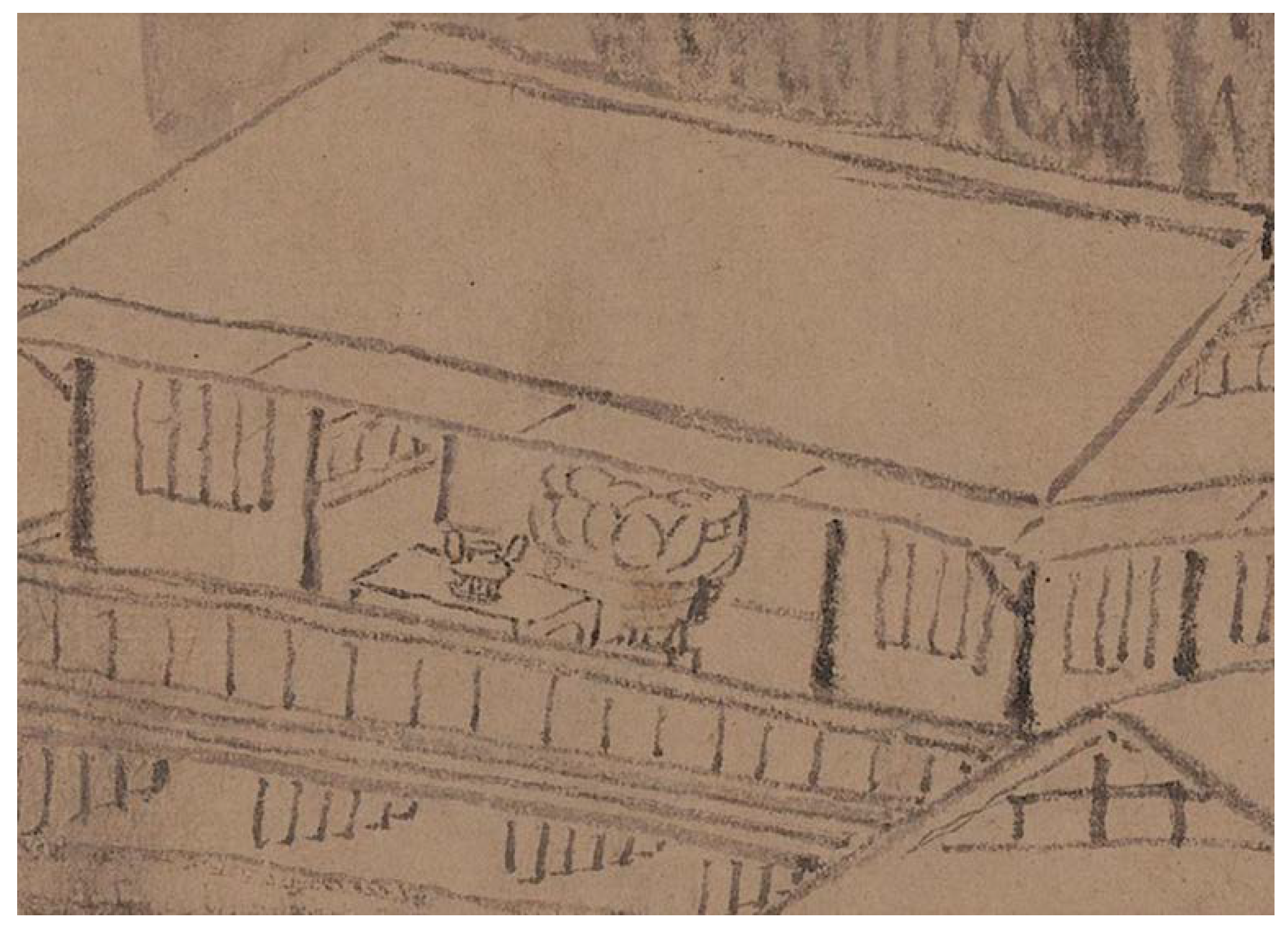

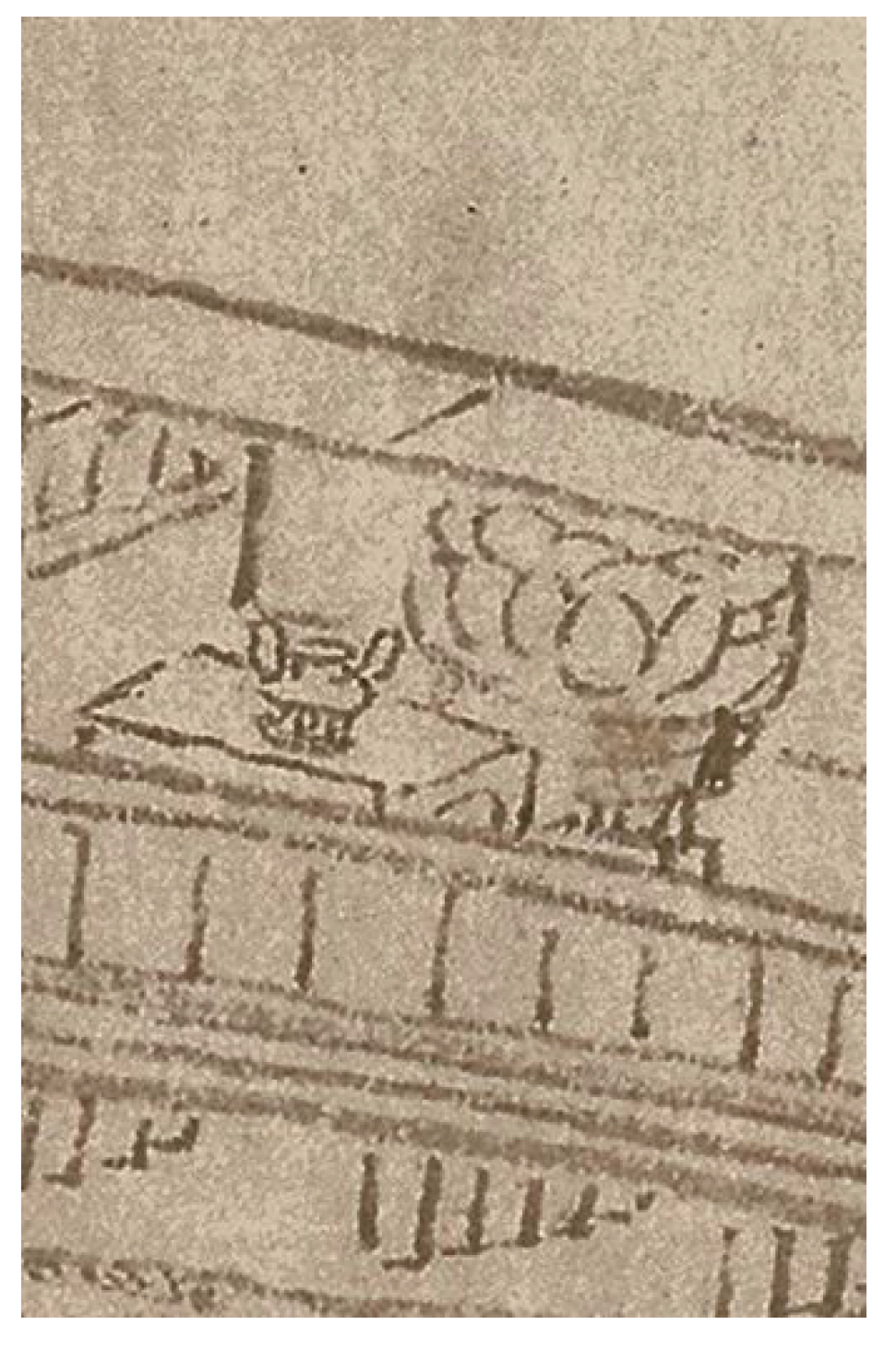

4.2. The Spirit Room

4.3. The Cliff and the Snowy Mountains

5. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Representations of the inner alchemical body were rarely found prior to the Song dynasty (960–1279), but the Song period clearly marks a turning point in the graphic representation of the body as in graphic representation in general. As Catherine Despeux elaborates, from the Song era onward, visual imagery comes to play a more significant role, not only as a record of knowledge, but also as a teaching aid, a mode of transmission, a mnemonic device, a visual translation of a text, and a representation of a certain reality, see Despeux (2005, p. 47). Anna Hennessey attributes this change to the development of Quanzhen Daoism and inner alchemy practice; just as internalization in the form of internal alchemy was becoming a focal component of Daoism, externalization in the form of alchemical representation was also rising as a tool through which this process of internalizing the religious experience could be actualized, see Hennessey (2011, p. 16). |

| 2 | In 2011, when the two pieces of his painting Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains 富春山居圖 reunited for the first time in the National Palace Museum in Taipei since their separation more than three and a half centuries ago, the exhibition attracted more than 840,000 visitors and remained as one of the most popular art shows ever since. See Exhibition and Museum Attendance Figures 2011 (2012, p. 35). |

| 3 | “Four Wangs” refer to Wang Shimin 王時敏 (1592–1680), Wang Jian 王鑑 (1598–1677), Wang Hui 王翬 (1632–1717), and Wang Yuanqi 王原祁 (1642–1715). |

| 4 | According to the Yuan dynasty anthology Ghost Notes 錄鬼簿, the earliest recording of Huang’s biography, Huang was adopted by the Huang Family 黃氏 of Wenzhou 溫州, Zhejiang Province. See Zhong (1991, p. 86). |

| 5 | Fuchun is located in the current Fuyang District, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province. Even though Huang Gongwang had lived in reclusion for many years, he still enjoyed a high-quality social life. Huang’s acquaintances include established Daoists, high-level officials and significant literati/painters. Since the Mongol reign barred educated Chinese from civil service exams, these disenfranchised literati frequently gathered in their estates and bequeathed each other paintings, poems, and inscriptions. Huang Gongwang formed a solid tie with Ni Zan 倪瓚 (1301–1374) and Zhang Yu 張雨 (1277–1348), both Daoists and painters. For an extensive analysis on Huang’s literati circle, see Augustin (2012, pp. 63–76); Halperin (2018, pp. 572–625). Also see Xie (2018, pp. 179–203). |

| 6 | Zhengtong Daozang 正統道藏 (hereby referred to as DZ) was printed under the Zhengtong (r. 1436–1449) reign in 1445. It is one of the most authoritative collections of Daoist texts, graphs, charts, maps, talismans, and so on. This paper uses the Daozang text published by the three publishing houses (sanjiaben 三家本), see Daozang (1988). This paper benefits greatly from Schipper (2005). The work number follows the title concordance of Schipper and Chen (1996). |

| 7 | 嗣全真正宗金月巖編, 嗣全真大癡黃公望傳. See DZ (242, 281, 576). |

| 8 | For example, the twelve pine trees carefully arranged in the right front corner of the painting can be read as the twelve-story tower, symbolizing the human trachea. |

| 9 | To avoid misunderstanding, I am not saying that we should always couple inner alchemy with Huang’s landscape paintings, nor that every painting from Huang Gongwang has an inner alchemical connotation. It is also not my intention to demarcate a fundamental boundary between the inner and outer realm of landscape paintings, nor between the presence and absence of the body. |

| 10 | Within the context of inner alchemy, the human body is viewed as a microcosm reflecting the macrocosmic order. It is divided into three distinct realms known as the upper cinnabar field, the middle cinnabar field, and the lower cinnabar field, which correspond symbolically to heaven, the central, and earth, respectively. The lower cinnabar field, referred to as the huangting黃庭or yellow court, resides approximately 1.3 inches below the navel and serves as the energetic center associated with essence. The middle cinnabar field, also known as jianggong 絳宮 or crimson palace, occupies the central region of the chest and represents the locus of breath. Finally, the upper cinnabar field, identified as niwan gong泥丸宮or palace of muddy pellet, and alternatively termed qiangong 乾宮 or palace of qian, denotes the brain region and serves as the seat of the spirit. These three fields, with their respective functions and locations within the body, constitute integral components of the intricate inner alchemical system. |

| 11 | 魂乃陽神,魄乃陰形,形借神靈,月望日明. (DZ 242). |

| 12 | 三火既定,并会于下丹田,聚烧金鼎,锻鍊玉炉,薰蒸关窍,使一身阴消阳长,太真阳气上下颠倒循环,自然锻鍊成一粒赫赤龙虎金丹大药也. (DZ 281). |

| 13 | 神室者,丹之所由,斯而修也。《龍虎經》曰:神室者,丹之樞紐。夫人之一身,臟腑窒塞,無些縫罅,惟神室空虛,方寸如室之空能容人,如器之空能容物。夫人以髓海為天,精房為地,陰陽二炁升降行乎其中矣。其神室在天地之中, 上有黃庭,下有關元. (DZ 576). |

| 14 | |

| 15 | 此身為天地爐竈, 中宮為鼎, 身外乃太虛。乾宮髓海, 坤宮精房, 神室丹鼎,名曰三宮. (DZ 90, 8a–b). |

| 16 | 神室者,元神所居之室,是也。人知立鄞鄂之造化,顯然彰露矣!抑不知有室而無主人,何取其為室哉!然主人雖無,而主人之胎,亦在乎一室之中矣!(DZ 240). |

| 17 | 性火不動者則神定,神定則氣定,氣定則精定. (DZ 281). |

| 18 | |

| 19 | 黃婆設盡千般計,金鼎開成一朵蓮 See Quan Tang Shi (1960, pp. 9710–11). Inner alchemy believes that the saliva of the spleen could nourish the other viscera, and the spleen is thereby called the “mother”. Since the spleen is associated with the earth and the yellow color, it is thus referred to as the yellow mother. |

| 20 | 不識玄中顛倒顛,爭知火裏好栽蓮. (DZ 263). |

| 21 | 火里不可栽蓮,男兒安得成孕?今修煉之道,乃玄中之玄,妙中之妙. 還返陰陽,顛倒造化,而使男子結胎以成丹,此猶火中栽蓮以結子也. |

| 22 | The motif also appeared in later time. For one instance, in the second chapter of Journey to the West, the master reveals the secret of immortality to Sun Wukong, saying: “The moon contains a jade rabbit, the sun a golden crow, the tortoise and the snake are always intertwined. Always intertwined, life and nature are firm, and one can plant a golden lotus in the fire. Grasp all the five elements and turn them upside down, and when you are successful, you can become a Buddha or an immortal.” 月藏玉兔日藏烏,自有龜蛇相盤結。相盤結,性命堅,卻能火裏種金蓮。攢簇五行顛倒用,功完隨作佛和仙 (Wu 2005, p. 18). Aside from all the alchemical metaphors, the master is telling Sun to revert yin and yang to generate the elixir (the lotus). |

| 23 | The collection of drawings is attributed to Longmei zi 龍眉子. The preface of the illustration dates to 1218, with the colophon dating to 1222. See Baldrian-Hussein (2005, pp. 832–34). |

| 24 | 上有三角,方廣萬裏,形似偃盆,下狹上廣,故名曰昆侖山三角 (Dongfang n.d.) |

| 25 | 雪山乃至陰之地. |

| 26 | 後腦陽光不照之處,卻有千年雪. For a detailed analysis of the body chart, see Fava (2013, pp. 88–91). |

References

- Augustin, Birgitta. 2012. Modern Views on Old Histories: Zhang Yu’s and Huang Gongwang’s Encounter with Qian Xuan. Arts Asiatiques 67: 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian-Hussein, Farzeen. 2005. Jinyi huandan yinzheng tu. In The Taoist Canon: A Historical Companion to the Daozang/from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Edited by Kristoffer Schipper. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 832–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, James. 1976. Hills Beyond a River: Chinese Paintings of the Yuan Dynasty, 1279–1368. New York: Weatherhill. [Google Scholar]

- Daozang 道藏 (The Daoist Canon). 1988. Sanjia ben 三家本. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, Shanghai: Shanghai Shuju, Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe, vol. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Despeux, Catherine. 2005. Visual Representations of the Body in Chinese Medical and Daoist Texts from the Song to the Qing Period (Tenth to Nineteenth Century). Asian Medicine: Tradition and Modernity 1: 10–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despeux, Catherine. 2019. Taoism and Self Knowledge: The Chart for the Cultivation of Perfection (Xiuzhen tu). Translated by Jonathan Pettit. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Dening 董德寧. 2015. “Wuzhenpian Zhengyi” 悟真篇正義 (The Correct Meaning of Wuzhen pian). In Wuzhen Pian Jishi 悟真篇集释 (Collected Commentaries of Wuzhen Pian). Edited by Boduan Zhang. Annotated by Baoguang Weng 翁葆光, Daoguang Xue 薛道光, Yuanding Xia 夏元鼎, Susi Tao 陶素耜, Dening Dong 董德寧 and Yiming Liu 劉一明. Beijing: Zhongyang Bianyi Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Dongfang, Shuo 東方朔. n.d. Shizhou ji. 十洲記 (Record of the Ten Island Continents). Available online: https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=gb&file=204853&page=27&remap=gb (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Esposito, Monica. 2008. Huohou. In The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Edited by Fabrizio Pregadio. Oxford: Routledge, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Exhibition and Museum Attendance Figures 2011. 2012. The Art Newspaper. No. 234. April, p. 35. Available online: https://www.skny.com/attachment/en/56d5695ecfaf342a038b4568/Press/56d56991cfaf342a038b64df (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Fan, Zhen. 2022. The Tripods in Daoist Alchemy: Uncovering a Material Source of Immortality. Religions 13: 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, Patrice. 2013. Aux portes du ciel: La statuaire taoïste du Hunan, Art et anthropologie de la Chine. Paris: Les Belles Lettres/ÉFEO, pp. 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, Mark. 2018. Explaining Perfection: Quanzhen and Thirteenth-century Chinese Literati. T’oung Pao 104: 572–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessey, Anna. 2011. Chinese Images of Body and Landscape: Visualization and Representation in the Religious Experience of Medieval China. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Shih-Shan Susan. 2012. Picturing the True Form: Daoist Visual Culture in Traditional China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Shih-Shan Susan. 2014. Xie zhenshan zhixing: Cong ‘shanshuitu’ ‘shanshui hua’ tan daojiao shanshuiguan zhi shijue xingsu 寫真山之形:從「山水圖」、「山水畫」談道教山水觀之視覺型塑 (Shaping the True Mountains: “Shanshui tu”, “Shanhui hua”, and Visuality in Daoist Landscape). Gugong Xueshu Jikan 故宮學術季刊 31: 121–204. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Ziyun. 2022. Visualizing the Invisible Body: Redefining Shanshui and the Human Body in the Daoist Context. Religions 13: 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meulenbeld, Mark. 2021. The Interiority of Landscape: Transcendence in a Late-Ming Painting of Snowy Mountains. Asia Major 34: 43–91. [Google Scholar]

- Pregadio, Fabrizio. 2021. The Alchemical Body in Daoism. Journal of Daoist Studies 14: 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan Tang Shi 全唐詩 (The Complete Collection of Tang Period Poems). 1960. Peng, Zhengqiu, ed. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 25 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, Kristofer, and Yaoting Chen. 1996. Daozang Suoyin: Wu Zhong Banben Daozang Tongjian 道藏索引:五種版本道蔵通檢 (Index to the Daoist Canon: Concordance of the Five Editions of the Daoist Canon). Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, Kristoffer. 2005. The Taoist Canon: A Historical Companion to the Daozang/from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, Shou-Chien. 2015. Cong Fengge Dao Huayi: Fansi Zhongguo Meishu Shi 從風格到畫意:反思中國美術史 (From Style to Huayi: Ruminating on Chinese Art History). Beijing: Shenghuo Dushu Xinzhi Sanlian Shudian. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Chengen 吳承恩. 2005. Xi You Ji 西遊記 (Journey to the West). Beijing: Renmin Wenxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Bo. 2018. Huazhi Shang de Daojing 畫紙上的道境 (The Visualization of Daoist Elysium). Chengdu: Sichuan Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Boduan. 2015. Wuzhen Pian Jishi 悟真篇集释 (Collected Commentaries of Wuzhen pian). Annotated by Baoguang Weng 翁葆光, Daoguang Xue 薛道光, Yuanding Xia 夏元鼎, Susi Tao 陶素耜, Dening Dong 董德寧 and Yiming Liu 劉一明. Beijing: Zhongyang Bianyi Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Sicheng 鍾嗣成. 1991. Jiaoding luguibu sanzhong 校訂錄鬼簿三種 (Three Revised Editions of Ghost Notes). Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Z. Transforming Inner Alchemical Vision into Painting: Huang Gongwang’s Clearing after Sudden Snow. Religions 2023, 14, 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070861

Liu Z. Transforming Inner Alchemical Vision into Painting: Huang Gongwang’s Clearing after Sudden Snow. Religions. 2023; 14(7):861. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070861

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ziyun. 2023. "Transforming Inner Alchemical Vision into Painting: Huang Gongwang’s Clearing after Sudden Snow" Religions 14, no. 7: 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070861

APA StyleLiu, Z. (2023). Transforming Inner Alchemical Vision into Painting: Huang Gongwang’s Clearing after Sudden Snow. Religions, 14(7), 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070861