Abstract

The Śyāma jātaka is renowned for its portrayal of a devoted son who cared for his blind parents. The story has been translated into various textual versions and depicted in reliefs and murals, gaining wide circulation in the Buddhist world. Previous scholarship on the story’s transmission in China has primarily focused on its representation of filial piety and its resonance with the Chinese context. However, a careful examination of surviving visual depictions of jātaka stories brings to light historical and regional disparities that have often been overlooked in relation to the reception of Śyāma jātaka’s didactic teachings in early medieval China. While the story has flourished in North China (including the Central Plain and the Hexi Corridor) from the late fifth century onwards, it was intriguingly absent from the region during the first half of the sixth century. This absence of the Śyāma jātaka stands in contrast to the popularity of other jātakas such as Sudāna and Mahasattva, which were widely circulated in China. In this article, I explore the uneven adaptation of the Śyāma jātaka within Chinese visual culture by placing the story’s textual and visual traditions within the broader historical milieu of depicting Buddhist stories and filial paragons in the sixth century. My study demonstrates that the story’s theme in multiple dimensions was simplified to filial piety during the textual translation process of the story in third- and fourth-century China. Moreover, it reveals that the story’s visual legacy faced challenges and negotiations when integrating into the local teaching of filial piety. This reluctance can be attributed to two historical factors: the revival of pre-existing visual traditions depicting Chinese filial sons, and the growing preference for other jātakas that embodied teachings on generosity in early sixth-century North China. Furthermore, this study sheds light on the tension between textual and visual traditions when incorporating Buddhist teachings into a new social context. While various rhetoric strategies were developed in text translation to integrate Buddhist teachings into existing Chinese thought, the visual tradition posed separate questions regarding its necessity, the didactic intentions of patrons, and the visual logic understood by viewers.

1. Introduction

The Śyāma jātaka,1 a story of a filial son supporting his blind parents, has been widely circulated in the Buddhist world. The story has been translated into multiple textual versions and depicted in various reliefs and murals. While the visual representation of the story became popular in fifth-century North China (including the Central Plain and the Hexi Corridor, see Figure 1), it soon declined duringthe first half of the sixth century. The story was later revived in the mid-sixth century in the Hexi Corridor 河西走廊 (approximately present-day Gansu 甘肅 province), a region connecting North China and Central Asia, however, in a completely new pictorial mode.2

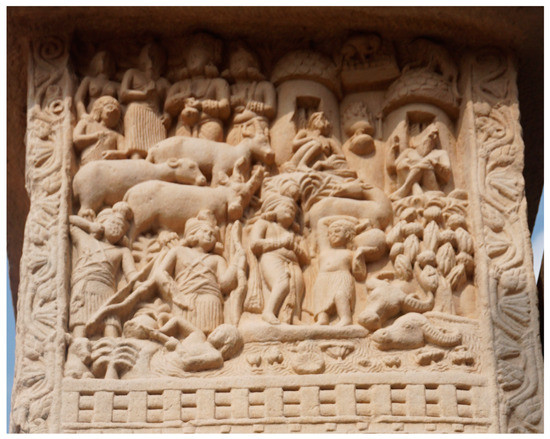

Figure 1.

Śyāma Jātaka. Pillar, west gate of the Great Stupa at Sañchī. Bhopal, India. First century BCE. Photo taken by author.

This study aims to unravel the imbalanced adaptation of the Śyāma jātaka in early medieval China by contextualizing its textual and visual traditions within the broader historical dissemination of Buddhist jātakas and the promotion of filial piety as a moral code. It examines how the storyline of the jātaka underwent certain degree of modifications in its Chinese translations made during the third and fourth centuries, how story’s visual tradition lost popularity from the North China art scene at the beginning of the sixth century, and how the story was perceived and received by local society. Previous work in Buddhist studies has used visual materials of the Śyāma jātaka as supporting evidence to emphasize the Chinese interest in filial piety, but often leaving the story’s visual representations unexamined in pictorial and historical contexts. This study addresses this gap by focusing on the tension between textual and visual traditions when incorporating Buddhist teachings into a new social context.

I propose two historical factors to understand the unexpected decline in popularity of the Śyāma jātaka in the early sixth century. The first factor is the replacement of the Śyāma jātaka with the Sudāna (Xudana 須大拏) jātaka, a different popular tale, to form a pair with the Mahasattva 萨埵 jātaka in major artistic venues. It suggests a shift in the emphasis of jātakas’ didactic purpose on filial piety. The second factor is the emergence of a new arena for teaching filial piety in early sixth-century North China, made available by the revived artistic tradition of portraying local Chinese filial paragons (xiaozi gushi 孝子故事).

The first factor is highlighted through the comparative study of the Śyāma jātaka with the Sudāna and Mahasattva jātakas. In the fifth century, the Mahasattva jātaka was always depicted together with the Śyāma jātaka on steles. However, in the sixth century, the Mahasattva jātaka started to be displayed together with the Sudāna jātaka. In other words, the Sudāna jātaka replaced the Śyāma jātaka to create a new pair of the popular jātakas since the early sixth century, or late Northern Wei 北魏 dynasty (386–534 CE). This study thus emphasizes the importance of studying jātakas in relation to one another and examines how Buddhist stories are appropriated in context, with a detailed dissection of the social, cultural, and artistic background of jātakas.

I propose a second factor that is rooted in the contemporaneous artistic developments in the capital region of Luoyang, where the popularity of the Śyāma jātaka declined and the depiction of the filial son stories rose to prominence in local burials. A careful examination of the early sixth century’s historical context points to the Sinicization reform, which was carried out during the reign of Emperors Xiaowen 孝文 (r. 471–499 CE) and Xuanwu 宣武 (r. 499–515 CE). This reform process aimed to adopt the Chinese cultural framework, which may have influenced the revival of depicting Chinese filial paragons.

These two factors contribute to our understanding of the fluidity of the concept of filial piety in the visual representation of the Śyāma jātaka. It also reveals the tension between the textual and the visual traditions in adapting Buddhist teachings into the indigenous Chinese social milieu. While various rhetoric strategies in text translation were developed to integrate Buddhist teachings into existing Chinese thoughts, the visual tradition encountered separate questions concerning the availability, the necessity, and the visual logic of viewers, etc. This study reveals that the visual tradition of jātaka stories not only conforms to the textual tradition but is also deeply intertwined with the cultural and social norms, state policies, patrons’ personal tastes, etc.

2. The Transmission of Śyāma Jātaka from India to China

Śyāma’s story narrates one of the previous lives of the Buddha, who was born as Śyāma. In this particular life, Śyāma resided with his blind parents in an ascetic lifestyle. One fateful day, while Śyāma was on his way to fetch water, an arrow struck him, mistakenly or intentionally (in different versions) shot by the king of Benares (or Kapilavastu in the story’s Chinese versions). Śyāma told the king about his concern for the plight of his blind parents. Out of fear, the king promised to take care of the elderly couple. Subsequently, the king discovered the blind couple and revealed the tragic incident involving Śyāma. Overwhelmed with sorrow, the couple wept upon Śyāma’s lifeless body. Witnessing Śyāma’s profound compassion, the God Sakka was deeply moved and descended to restore Śyāma back to life. Miraculously, the blind parents also regained their sight.3

Several earlier Chinese translations of the Śyāma jātaka were made during the third and fourth centuries, including a chapter in Liudu ji jing 六度集經 (Ṣaṭpāramitā-saṃnipāta Sūtra) (T03, no. 152, 24b-25a) by Kang Senghui 康僧會 from Wu 吳 (222–280), Foshuo Pusa Shanzi jing 佛說菩薩睒子經 (Śyāmakajātaka sūtra) (T03, no. 174, 438b-440a) by Shengjian 聖堅 of the Western Qin dynasty (385–431), Sengjialuocha suoji jing 僧迦羅剎所集經 (Sūtra Compiled by Saṅgharakṣa) (T04, no. 194, 116c-117a), and Za baozang jing 雜寶藏經 (Saṃyuktaratna Piṭaka Sūtra) (T04, no. 203).4 In these versions, Śyāma’s name is translated into Shanmo 睒摩 or Shanzi 睒子. Huijiao also mentions the story in his work Gaoseng zhuan 高僧傳 (Biographies of Eminent Monks).5 Additional references can be found in Buddhist encyclopedia works, such as Fayuan zhulin 法苑珠林 (T53, 656ff) and Jinglü yixiang 經律異相 (T53, no. 2121, 51b-52c). Xuanzang briefly mentions the story in his work Datang xiyu ji 大唐西域記 (T51, no. 2087, 881b). In the Song dynasty, the story was even adapted into popular literature and listed as one of the twenty-four standard models of piety (Xie 2001).

Overall, the emphasis on Śyāma’s act of filiality in the story’s Chinese versions is a noticeable modification that has been extensively examined in previous scholarship. This modification is used as primary evidence for the claim that Buddhist beliefs and practices were adapted to traditional Chinese values of filial piety and ancestor worship. In other words, the story is used as an example to expound how Buddhists conform to Chinese culture by emphasizing the moral teaching of filial piety in Buddhism. As Kenneth Ch’en argued, the teaching of filial piety was a distinctive aspect of Chinese Buddhism. The rhetoric strategy used in the literature of filial piety, such as the Śyāma jātaka, highlights how the monk achieves a unique position to convert his own parents to accept redemption and escape the endless cycle of suffering (Ch’en 1968, pp. 81–97). This argument is partially challenged by later scholarship that retrieves the importance of filial piety in Buddhist teachings prior to Buddhism’s dissemination in China.6 Although filial piety might not be fundamental to the belief system as it is for Confucian ethics, its practice has been always portrayed as the chief good karma in the Buddhist moral teaching.

The exact source text of the Chinese versions of the Śyāma jātaka remains unaddressed due to the scarcity of earlier texts that have survived. Scholars that write at length about the story usually focus on its Chinese lineage. The most cited version of the Śyāma jātaka is listed as number 540 in the Pāli collection of jātakas (Sāma in Pāli) and is categorized under the teaching of “loving-kindness,” the ninth perfection.7 This version features a highly detailed prelude, or the “story of the present” that sets the context for the jataka (Fausbøll 1896, pp. xiii–xv; Grey 1990; Shaw 2006, pp. 280–310). In this prelude, the protagonist faces the dilemma of either supporting his family or pursuing a monastic life, until the Buddha reveals a path where he can fulfill his duties as an ascetic to support his parents. It is within this context that the Buddha recounts the story of supporting blind parents in a previous life, namely, Śyāma’s story. The significance of “loving-kindness” is emphasized through the narrative, as none of the figures harbor any anger towards one another. The Sanskrit version of the story is found in the Mahāvastu and the jātakamālā (Jones 1952, vol. 2, pp. 199–231; Khoroche 2017, pp. 95–103). The two versions bear multiple different details, such as the occupation of the blind couple before their retreat into the forest, yet more similarities in the structure are found in the Sanskrit versions in comparison to the Pāli version. There is no frame story in either Sanskrit version, unlike the lengthy account of a separate story of an ascetic. The story is recounted in a lengthy version that reveals multiple plots and settings for the lives of Śyāma’s parents.

Previous scholarship on the Śyāma jataka’s Chinese popularity often attributes the story’s Chinese translations to the Pāli version for the frame story shared by them.8 The jātakamālā version has rarely been mentioned. Yet, a brief comparison of these later Pāli and Sanskrit versions with the surviving Chinese versions reveals multiple different accounts here and there, suggesting a more complicated history of transmission.9 The exact scriptures that the Śyāma jātaka’s Chinese translations are based on have been lost. It is beyond the scope of the present research to unravel the transmission lineage of the scripture of the Śyāma jātaka. However, several interesting alterations might be worth highlighting here. For instance, in the Foshuo Pusa Shanzi jing, after learning about Śyāma’s death, the blind parents uttered “the act of truth,” expressing that if Śyāma truly embodied filial piety and honesty, then let him be restored to life.10 Such an emphasis on the power of filial piety is not found in the Sanskrit or Pāli versions, although the Sanskrit versions also expound upon the foremost significance of supporting one’s parents. In comparison, the Pāli version lists a number of duties for the king to fulfill, rather than pinpointing the filial piety or Śyāma. The core teaching as propounded in the Pāli version primarily targets the king’s duty.

Another interesting difference also involves the king. In the Chinese texts and two Sanskrit versions, the king accidentally injures Śyāma because Syama is wearing deerskin coverings, rather than intentionally shooting Śyāma as described in the Pāli version. Realizing the consequences of his actions, the king in the Chinese translations experiences great remorse and offers to care for Śyāma’s blind parents, similar to the Sanskrit versions but differing from the Pāli version where the king informs Śyāma’s parents merely out of fear of retaliation. This distinction decides whether the king’s action is intentional or accidental, making the king himself a victim or not.

Not only has the textual tradition of the Śyāma jātaka undergone changes in the Chinese context, but the story’s visual representations found in reliefs and murals in China also exhibit a diverse range of iconography, styles, and compositions that deviate from earlier traditions in South Asia. The visual depiction of the story first emerged in India around the first century BCE, adorning monumental stūpas, and subsequently spread to major Buddhist sites throughout South Asia. For example, at the Great Stūpa at Sañchī, the story is rendered within a confined rectangular space on the inner face of the gateway pillar, with figures and elements from the Śyāma jātaka filling the space (Figure 1) (Marshall 1918, p. 73; Dehejia 1997, pp. 114–15). Surviving reliefs from the first century CE in Gandhāra (Figure 2), located in present-day northwestern India and Pakistan, employ a different narrative mode. Notably, for instance, two stair risers preserved in the British Museum show the story in a horizontal format, with scenes divided by trees that serve as a natural framing device. The staircase reliefs present three sequential scenes from the left to the right: (1) the king approaching the blind couple; (2) the king leading the couple towards the right; and (3) the couple collapsing by the body of Śyāma. This sequential arrangement demonstrates the use of the continuous, linear mode typical of Gandhāran art. In later depictions at Ajanta, specifically in murals found in Caves 10 and 17, the story is arranged according to location rather than following a strict chronological order.11

Figure 2.

Śyāma Jātaka. Stair-riser, Gandhara, 2nd–3rd Century CE, No. 1880.55. The British Museum.

Kizil cave temples, located on the northern edge of the Tarim basin, are the primary site in Central Asia where the Śyāma jātaka is frequently depicted (Figure 3).12 Like other jātakas in Kizil, the Śyāma jātaka is portrayed within rhombus-shaped spaces on vaulted ceilings or in rectangular sections on side walls.13 In these limited areas, the central scene captures the moment when Śyāma draws water from a pond while the king takes aim with his arrow. Occasionally, depictions of the blind parents sitting in huts can be seen in the background.

Figure 3.

Kizil Cave 198, west wall on tunnel ceiling. Zhongguo shiku: Kezier shiku, vol. 3, Figure 105.

In the heartland of China, the earliest depiction of the Śyāma jātaka can be found on the backscreen of four surviving statues dating back to the mid-to-late fifth century.14 These statues were unearthed near Pingcheng 平城, the capital city of the Northern Wei dynasty, and they share remarkably similar relief carvings on their backscreens. These reliefs illustrate Śyāma’s story in conjunction with the Mahasattva jātaka, which tells the story of Prince Mahasattva’s self-sacrifice to save a starving tigress and her cubs, as well as the life story of the Buddha.

For instance, one of the statues, dating back to 455 CE, features a backscreen divided into four registers (Figure 4). The upper register depicts scenes of the Buddha’s birth 樹下誕生 and first bath 九龍吐水, while the middle two registers showcase various scenes from the Śyāma jātaka. The lowest register is dedicated to the Mahasattva jātaka. The Mahasattva jātaka tells the story of how the prince Mahasattva offers his own body to feed a hungry tigress and her cubs so that the tigress would not have to eat her own children. In case the tiger would not eat him alive, the prince jumps off from the edge of a cliff. The right section shows the prince being surrounded by the cubs. The Śyāma jātaka unfolds chronologically from the upper left to the lower right, depicting Syama assisting his blind parents in the wilderness, fetching water, and being shot by the king, and concludes with the blind parents falling collapsed by Śyāma’s body. The other three statues feature reliefs similar to the one from 455, combining Śyāma and Mahasattva jātakas as well. The depiction of the Buddha’s birth and first bath became a convention in Buddhist statuary and steles from the mid-fifth century onwards in Pingcheng and Chang’an 長安. Hence, the combination of the Śyāma and Mahasattva jātakas emerges as a prominent feature these four statues.

Figure 4.

Zhang Yong statue. Circa 455 CE, Northern Wei. H. 35.5 cm. Repository: Yūrinkan Museum, Kyōto. (Sun 2005, pp. 255–57).

Two decades later, in the 470s, the Śyāma jātaka was depicted in three caves at Yungang 雲岡 cave-temples, located to the west of Pingcheng (Yagi 1997; Hu 2005; Yi 2017; Peng 2017). At Yungang, the story unfolds in a continuous mode, with the protagonist Śyāma appearing repetitively in each individual scene. For instance, in Cave 7, the story is organized in a rectangular space without a clear framing device between each scene, yet Śyāma is depicted repeatedly. In the upper left corner, Śyāma is shown taking care of his blind parents. The central scene portrays the king shooting at Śyāma, while the lower left shows Śyāma lying down with an arrow in his chest. The upper right section is damaged, but the lower right depicts Śyāma preaching to the king after his resurrection.

Reliefs in both Caves 1 and 9, which were excavated slightly later than Cave 7, present a more complete story in a continuous, linear mode (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Each individual scene is separated by pillars. Starting from the south wall and moving through the west and north walls, the story begins with a scene of the palace and the figures standing in a row, likely representing the king leaving the city. In the following scenes, we see the blind parents sitting in the same hut, while another figure kneels down with clasped hands and animals approaching in the background, symbolizing Śyāma leaving home to fetch water. The next cell, although partially damaged, is recognizable as the hunting scene, indicated by the arrangement of five figures riding on horses and holding bows. The last two scenes on the north wall depict the aftermath of the tragic event. The blind parents, sitting in huts, stretch out their arms, while a figure kneels down to the right side, representing the moment when the king informs the parents of Śyāma’s death.

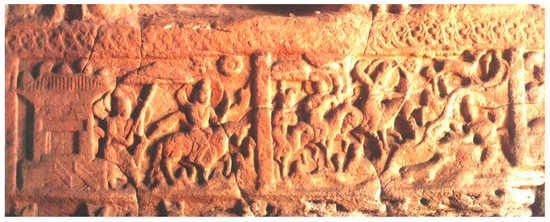

Figure 5.

Cave 1, Yungang. Circa 480s, Northern Wei. (Yungang shiku wenwu baoguansuo 1991–1994, vol. 1, Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Śyāma Jātaka. West and north walls of Cave 9. Yungang Grottos. Circa 490s. (Yungang shiku wenwu baoguansuo 1991–1994, Figures 20–25).

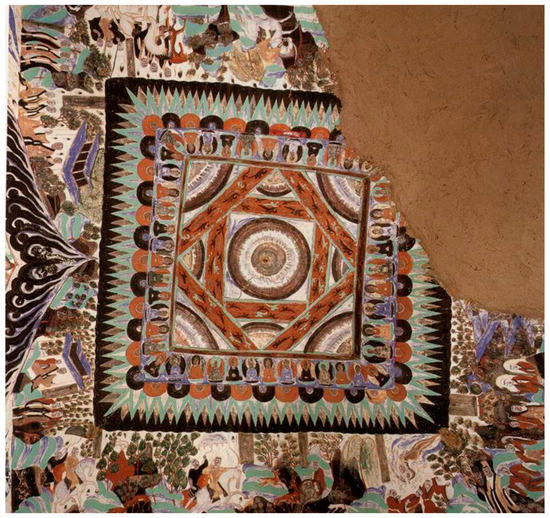

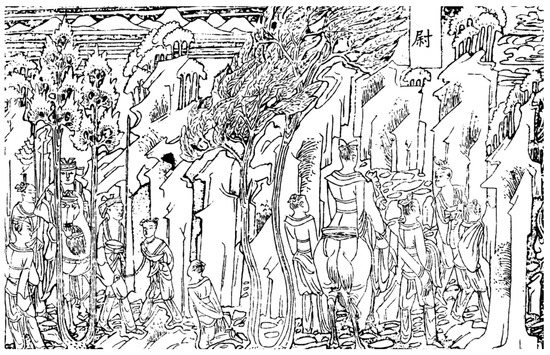

Although the compositional modes at Yungang vary, the visual narrative logic remains consistent. Śyāma appears as the dominant protagonist in every scene, driving the plot’s progression. Each scene is contained within a narrative cell that is separated from others by framing devices such as trees and pillars. This compositional feature aligns with the overall pattern of depicting narrative tales in Northern Wei and shows a certain degree of influence from Gandhara. However, examples from the Dunhuang and Maijishan cave-temples, which are located along the Hexi corridor, differ from the Yungang examples. At the Mogao cave-temples in Dunhuang, Śyāma jātaka decorates the ceiling space in seven caves, including four from the Northern Zhou 北周 (557–581 CE) and three from the Sui dynasty 隋 (581–618 CE).15 Taking Northern Zhou Cave 299 as an example, the story is situated on three sides of the ceiling’s edge (Figure 7), while the remaining space is filled with the Mahasattva jataka (Takada 1982; Dunhuang Wenwu Yanjiusuo 敦煌文物研究所 1980–1984; Li 2000, 2001; Xie 2001; Higashiyama 2011; Sha 2011; Gao 2017a, 2017b). On the left, the king is shown marching with his servants, while on the right, Śyāma’s parents are depicted sitting in their huts. The figures’ activities unfold in a landscape of hills, trees, and streams that divide the narrative cells. These new features signify a departure from the fifth-century tradition by emphasizing the king’s retinue, the natural setting, and, particularly, a non-linear narrative mode. These murals skillfully integrate natural and figural images, contrasting with the previous relief carving tradition in Chang’an and Pingcheng, which focused on depicting the movement of the protagonist Śyāma to unfold the story. Current studies suggest an influence from Maijishan on these Dunhuang murals of the Śyāma jataka (Donohashi 1978; Bell 2000; Li 2000; Cai 2004; Zheng and Sha 2004; Gao 2017a, 2017b).

Figure 7.

Ceiling, Mogao Cave 299. Northern Zhou, late sixth century. (Li 2001, Figure 110).

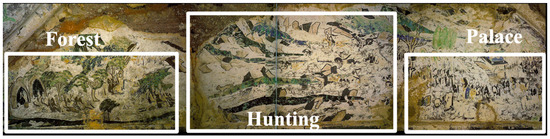

The Maijishan cave temples was carved into Maiji Mountain starting from the mid-fifth century onwards. The story of Śyāma is depicted on the front side of the sloping wall of Cave 127, which is dated to the 540s, Western Wei (Figure 8). Unfolding from right to left, identifiable scenes include the king leaving the palace, the hunting scene, the mistaken shooting at Śyāma, and the blind couple collapsing upon learning about Śyāma’s death. Overall, the composition and selection of scenes in Dunhuang and Maijishan murals diverge from the fifth-century Yungang tradition of the Northern Wei.

Figure 8.

Maijishan Cave 127, ceiling, front side. Western Wei, 540s. (Xia 1998, Figure 167). Annotated by author.

Nevertheless, more questions arise as we examine the Śyāma jātaka’s Chinese adaptations. Intriguingly, there is no trace of any depictions of the Śyāma jātaka from the 480s to the 540s when the Śyāma jātaka first appeared in Maijishan and Dunhuang. In other words, the Śyāma jātaka lost its popularity- in North China at the start of the sixth century.

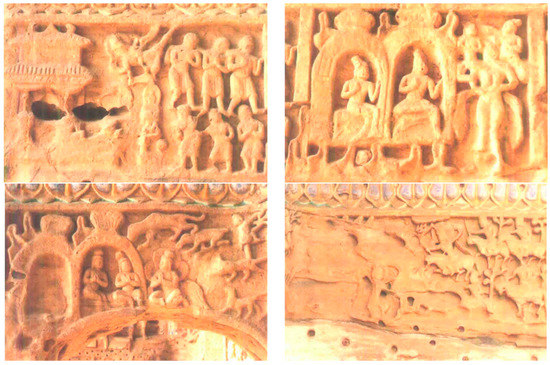

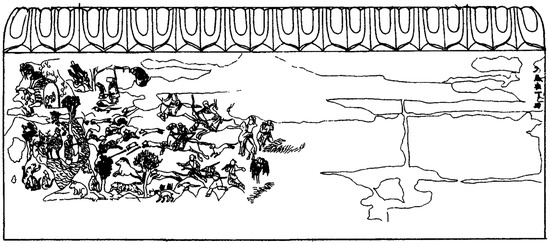

In north China, the only example of Śyāma jātaka from the sixth-century Central Plain is found carved on the pedestal of the Liubeisi 劉碑寺 Stele, which dates back to 557 CE (the eighth year of the Tianbao 天保 era), Northern Qi dynasty (Figure 9) (Wang 2006). While the right section of the relief is damaged, its middle section portrays a massive hunting scene, and the left section shows the story’s central plots. This tripartite composition is almost identical to the mural depicted in Maijishan Cave 127. This striking similarity indicates a direct influence from the Hexi Corridor, rather than adhering to the established tradition of fifth-century Pingcheng (see Figure 8). Consequently, it suggests the actual decline in the popularity of the Syama jataka in the Central Plain. Considering the geographical proximity of the Liubeisi Stele to the Central Plain rather than Maijishan, the preference for a Hexi prototype on the Liubeisi Stele may imply a lack of local references to depict the Śyāma jātaka. Thus, this circumstantially supports the argument that the Śyāma jātaka was not widely popular anymore during the early sixth century in the Central Plain.

Figure 9.

Liubeisi stele, 557 CE, Northern Qi. Southern Henan. (Wang 2006, Figure 6).

3. Śyāma Jātaka’s Rise to Prominence in the Fifth-Century Northern Wei Court

To better understand the story’s decline in popularity in the sixth century, it requires a closer analysis of factors contributing to its sudden rise to prominence in the fifth century. In the late fifth century, an influential translation project took place in Pingcheng, led by the renowned and enigmatic monk Tan Yao 曇曜. Notably, Tan Yao was also the chief designer of the initial construction of the Yungang cave temples.16 Assembling eminent monks near Yungang, Tan Yao embarked on a significant endeavor of translating sūtras, starting around 462.17 Among these translated sūtras is the Za baozang jing 雜寶藏經 (The Sūtra of the Miscellaneous Treasures), which Tan Yao collaborated on with Ji Jiaye 吉迦夜 in 472.

The stories and their arrangement in the Za baozang jing reveal the central role of the didactic teaching of filial piety in the sūtra. The stories in the sūtra are organized thematically, which is believed to have been re-edited by the translators. Most stories are also retold with certain degrees of discrepancy from the major versions. Liang Liling’s 梁麗玲 research suggests that the stories were initially retold by Ji Jiaye based on memory and later translated by Tanyao and the others. The first category of the sūtra is about filial piety, which includes four specific topics. The Śyāma jātaka is the second story listed in this category. The story itself also underwent certain modifications, as the introductory section discusses the offering of flesh to parents, which is not part of the storyline of the Śyāma jātaka. As proposed by Liang Liling, such an emphasis on filial piety is not seen in any other contemporaneously translated sūtras of Buddhist narratives (Liang 1998, pp. 117–25).

The direct religious and political context that influenced Tan Yao’s emphasis on filial piety in the sūtra is understood to be the persecution of Buddhism in the 450s. Emperor Taiwu 太武 (r. 423–452) issued the persecution, motivated by a conglomeration of interests, including the fear of social and economic disruption brought about by the expansion of the Sangha. Following the Taiwu persecution, Tao Yao’s translation project likely highlighted Buddhist stories that expounded on filial piety, a traditional Confucian moral teaching, in order to defend Buddhists against Confucian criticism. One of the main criticisms of Buddhism focused on the Buddhist ideals of renouncing family duties for a life of celibacy, which posed a possible threat to the Confucian emphasis on lineage continuity and social stability (Ch’en 1968, 1973). Considering Tan Yao’s influence in promoting Buddhism in court, the sūtra’s interest in filial piety would inherently have a significant impact in the capital area.

Another factor contributing to the rise of prominence of the Śyāma jātaka at Pingcheng can be attributed to the overall promotion of filial piety by the Northern Wei emperors since the early fifth century. Especially since the 460s, Emperor Xiaowen’s preference for the Xiao Jing 孝經 (Sūtra of Filial Piety) is evident in historical records.18 Xiaowen frequently quoted from the Xiao Jing19, likely influenced by his study with the chief master Feng Xi 馮熙, who was the elder brother of the Empress Dowager Wenming and known for advocating the Xiao jing.20 Several court orders regarding filial piety were issued in the 480s (Zou 2015, pp. 124–28, and chart 7). Zou Qingquan attributes this extravagant emphasis on filial son stories to the Dowager Empress regent Feng 馮太后, who endorsed these policies to indoctrinate the juvenile Emperor Xiaowen with Confucian values, ensuring his obedience to the Dowager Empress.

A recent study conducted by Xing Guang contributes another factor that highlights the importance of the Śyāma jātaka before the Tang dynasty. Guang argues that the Fumu en nanbao jing 父母恩難報經, an earlier translated text on filial piety, appears to conflict with Confucian filial piety by advocating leaving household life.21 In comparison, such a direct tone is not found in the story of the Śyāma jātaka. The frame story found in Śyāma jātaka’s Pāli version, about Śyāma’s parents leaving their household life for ascetic practice, is not absent in the story’s surviving Chinese versions.

4. From Pingcheng to Luoyang: Śyāma Jātaka’s Replacement by Sudāna Jātaka

Considering the particular importance of the Śyāma jātaka in the fifth-century Northern Wei in Pingcheng, its decline of popularity in the art scene in the early sixth century North China is indeed surprising. Why and how did the tradition of depicting the Śyāma jātaka completely disappear at the turn of the sixth century? What does this disappearance reveal about how Chinese Buddhism views filial piety? The above section examined the social context surrounding the Śyāma jātaka’s rise to prominence in the late fifth century, highlighting the sudden decline in its popularity by the beginning of the sixth century. In the following two sections, I argue for two historical factors that contributed to the waning popularity of the story: the new preference for other jātakas that embody teachings on generosity in early sixth-century North China, and the revival of the pre-existing visual tradition that depicts local Chinese filial paragons.

In terms of the immediate historical context, a pivotal event occurred in 494 CE when the Northern Wei court relocated its capital from Pingcheng to Luoyang. This shift marked a new phase of artistic production in various aspects. Following the establishment of the new capital, Buddhist steles experienced a flourishing period in the Luoyang region.22 Carved reliefs depicting jātakas can be found in Luoyang and its adjacent areas. Notably, the pair of the Mahasattva jātaka and the Sudāna jātaka emerged as the most popular theme, overshadowing the depiction of the Śyāma jātaka (Lee 1993; Hsieh 1999; Li 1996, 2016). No early or mid-sixth-century steles from the region have been found featuring any depiction of the Śyāma jātaka.

The Mahasattva jātaka is known to be carved in a pair with the Śyāma jātaka on the backscreen of statues in the previous tradition in fifth-century Pingcheng (see Figure 4). Therefore, the absence of the Śyāma jātaka in the early sixth century is accompanied by the rise of the Sudāna jātaka to prominence. In other words, since the early sixth century, the Śyāma jātaka was replaced by the Sudāna jātaka in forming a pair with the Mahasattva jātaka.

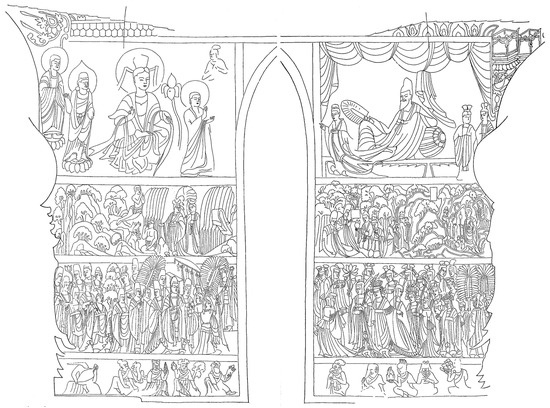

The first pairing of Sudāna jātaka and Mahasattva jātaka was found in the Binyang Central Cave 賓陽中洞 at Longmen 龍門, the most significant Buddhist cave temple site in present-day Henan Province (Figure 10). Together with two other cave temples, Binyang Central Cave was a project supported by the imperial-sponsored project (ca. 508–523 CE) during the late Northern Wei.23 It was sponsored by Emperor Xuanwu (r. 499–515 CE), Xiaowen’s son and successor, to commemorate his deceased parents. Binyang Central Cave includes fascinating images of exquisite craftsmanship. The cave’s entrance wall is divided into multiple horizontal registers, from top to bottom portraying the debate between Mañjuśri (Mile 彌勒) and Vimalakīrti (Weimojie 維摩詰),24 the Sudāna and Mahasattva jātakas, the imperial processions,25 and spirit kings. The paired composition of the two stories became widely spread in the next several decades, not only in North China but also in cave temples located along the Hexi Corridor (Li 1996, 2016).

Figure 10.

Second register of the relief to the right side of the doorway. Binyang Central Cave, Longmen 龍門 cave temples. Luoyang洛陽, Henan河南. Northern Wei, 520s. (Mizuno et al. [1941] 1980, Figures 18 and 19).

Why was the Śyāma jātaka replaced by the Sudāna jātaka? It is necessary to examine the didactic and religious significance of the three jātakas in the context of when and where they were depicted. It is because the Sudāna jātaka can serve two purposes that it rose to prominence and substituted the Śyāma jātaka. The two purposes include the teaching of generosity and the emphasis on transcendence seeking in two aspects.

Firstly, generosity, the virtue of gift-giving, one of the six pāramitās of Buddhism, is the fundamental teaching imbued in both the Sudāna jātaka and the Mahasattva jātaka. The Mahasattva jātaka tells the story of how the prince Mahasattva offers his own body to feed a hungry tigress and her seven cubs so that the tigress would not have to eat her own children. In case the tiger would not eat him alive, the prince jumps off from the edge of a cliff. In terms of the Sudāna jātaka (also called the Vessantara jātaka in major versions), the protagonist and his family are banished to exile after he gives away his kingdom’s magic elephant to Brahman emissaries from another region.26 After Sudāna settles down in the forest, a Brahman from a distant land finds Sudāna and makes the request of his two children.27 A visual representation of the Sudāna jātaka’s first occurred in India around the first century BCE in reliefs adorning monumental stūpas and was disseminated at major Buddhist sites across South Asia and Central Asia in the following centuries (Schlingloff 1988, 2013; Dehejia 1990).28 The pair of the Sudāna and Mahasattva jātakas can be understood as a site for the generation of merit, given the stories’ embodiment of charitable giving (McNair 2007, pp. 49–50).

The second factor contributing to the Sudāna jātaka’s rise to prominence derives from its newly coined teaching on the seeking of transcendence. Illustrations of jātakas from this period depict only a few select scenes to represent the story. In the case of the Sudāna jātaka, the most frequently depicted scenes shift from the act of giving to Sudāna’s exile. In previous South Asian and Central Asian traditions, as well as the Northern Wei reliefs from the fifth century, the selected scenes often center on Sudāna’s act of gifting, either an elephant, a chariot, or children. However, in the sixth-century Chinese cases, we found the outstanding emphasis on the scenes of exile. The perception of the knowledge, teaching, or message that is embedded in each group of episodes typically changes as the story focus changes from one set to the next (Dehejia 1990; Shih 1993; Murray 1995, 1998; Brown 1997). In the current case, the selection of the exile scene implies that the exile scenes grew significant enough to take the place of the previous emphasis on scenes of gifting.

A recent study shows that this shift in focus to the exile of Sudāna was partly shaped by the strengthened pursuit of practicing asceticism in early sixth-century Luoyang (Zhao 2021). According to the research, the depiction of Sudāna in exile echoes the elevated status of seeking transcendence in mountainous settings, a mentality shared by both Buddhists and Daoists at the time. This transition is interpreted through the study of new visual elements and selected scenes that were not developed until the early sixth century but exerted a huge influence in the following two decades in North China. The most crucial new visual element in reliefs of the Sudāna jātaka is the seated meditative monk, or sometimes a Daoist figure, in reliefs from sixth-century North China.29 A textual episode of the exile scene in two third-century Chinese translations sheds light on the current inquiry by revealing the identity of this figure in question as a rhetorical adaptation of Chinese immortals by translators.30 In both Taizi Xudana jing and Liudu ji jing, the figure sitting in the mountains is named Azhoutuo 阿州陀/阿周陀, who is famous for his virtue and longevity of five-hundred years, and his important role in guiding Sudāna during his exile in the mountains. His characteristics literally borrow lines describing Chinese immortals in contemporaneous writings such as Liexian zhuan and Baopuzi, rather than any earlier jātaka texts.31 Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the Sudāna jātaka’s prominence in the sixth-century visual tradition partly stems from the concept of ‘seeking transcendence,’ which had been developing as an underlying religious mentality ever since the third century. It was likely further advanced by the flourishing of Buddhist meditation practices at the time,32 a common interest in seeking transcendence at that time also connecting Buddhist and Daoist traditions (Poo 1995).

Furthermore, it is crucial to acknowledge that illustrations of these jātakas can be modified to fulfill ritualistic and symbolic purposes, underscoring the significance of shifts in the visual realm. Previous research on Buddhist narrative tales has demonstrated that the visual depictions could also serve the needs of various ritual practices (Wu 1992; Brown 1997). At the Central Bingyang Cave, an important imperial project being undertaken at Longmen, the mural illustration of Sudāna, the protagonist, alongside the ascetic figure in meditation, is positioned above the panels depicting an imperial procession. This arrangement carries particular significance during the late Northern Wei period. Not only does this composition speaks to the careful choice made in selecting the Sudāna and Mahasattva jātakas, but it also serves as a model and exemplar for future jātaka depictions in the subsequent decades. While not all Buddhist images from Northern Wei Luoyang can be directly attributed to court designs, the prominence of the pairing of the Sudāna and Mahasattva jātakas in the following years suggests that the artwork in Longmen acted as a pervasive model across the North. The imperial endeavor thus stands as a prototype or precedent for the later representations of jātakas in North China.

5. Filial Piety in Sixth-Century Funerary Context

The decline in the Śyāma jātaka’s popularity in the early sixth century can be attributed, as I argue, to a second factor: the resurgence of the pre-existing visual tradition of filial paragons in the Luoyang region. Concurrent with the disappearance of the Śyāma jātaka during this period, depictions of Chinese filial sons engaged in virtuous deeds experienced a revival within the funerary context in North China. This resurgence provides additional evidence to comprehend the perception of filial piety in the sixth century (Figure 11).33 At the new capital Luoyang in the early sixth century, the enhanced co-existence and equal importance of Buddhism and Han tradition inexorably encouraged the necessity of defining the ritual space as governed by the two traditions, respectively.

Figure 11.

Wang Lin story, stone sarcophagus. Nelson-Aktins Museum of Arts.

As I argue, the ritualistic and symbolic significance of filial piety as propounded in the Śyāma jātaka in the realm of Buddhism was challenged by the preference for filial paragons of the local tradition. The separation of the function of the Chinese ritual space from the Buddhist cave-temples was a natural outcome of the court’s supervision of constructions and designs, adhering to the traditional Han practices prevalent in Luoyang during the early sixth century. Against this historical backdrop, the Confucian moral teaching and ancestral worship inherent in filial piety predominantly found expression through traditional Chinese filial paragons in the funerary space. Conversely, the Buddhist cave temples were reserved for representing the teachings of Buddhism, emphasizing generosity and the pursuit of transcendence through the stories of Mahasattva and Sudāna.

While one could argue that the resurgence of filial paragons in Luoyang’s funerary art may not be directly responsible for the disappearance of the Śyāma jātaka in Buddhist art, both traditions derive their didactic significance from the focused teaching of filial piety. The Śyāma jātaka’s rise to fame in the fifth century in Pingcheng was influenced, to some extent, by the imperial court. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the sudden decline in the popularity of the Śyāma jātaka in the sixth century in Luoyang necessitates the consideration of the broader historical context of Sinicization (the assimilation of non-Han people into Chinese culture) and the rulers’ perception of filial piety during the Northern Dynasties.

The circulation of traditional Han filial stories dates back to at least the Warring States period and their maturity during the Han dynasty has been researched. Depicting the stories of historical personages, these filial paragons emerged as one of the most widely represented subjects for narrative illustrations alongside Buddhist stories in early medieval China. They were revered as embodiments of the quintessential Confucian morality. Although rich visual evidence in the form of relief carvings from the Han period has been unearthed in archaeological discoveries over the past few decades, very few visual remnants of these filial stories have survived from the subsequent two centuries. However, a notable shift occurred in the early sixth century in the Luoyang area, where stories of filial sons suddenly became the predominant subject depicted on stone funerary structures.

Filial stories were carved primarily on stone funerary structures, including stone coffins, mortuary couches, and house-shaped sarcophagi. The tradition of stone coffins, which prevailed during the Han dynasty, disappeared between the third and fifth centuries, only to be revived under the reign of the Northern Wei in Luoyang (Cheng 2011, pp. 191–218; Huang 1987). It is believed that the textual source for these stories during that time was the Xiaozi zhuan 孝子傳 (Accounts of Filial Offspring), a collection of popular didactic texts compiled in the early medieval period (Knapp 2005, pp. 46–82; Xu 2015; Xu 2017, pp. 105–12).34

According to recent scholarship, the reintroduction of stone mortuary equipment during the Northern Dynasties served not only as a symbol of political status but also as a means for non-Han Chinese to negotiate and establish their cultural and religious identities. Most of the surviving stone coffins belong to higher-ranking officials in the court of the Northern Wei. The elaborate illustrations of filial paragons on stone sarcophagi indicate the rapid popularity these tales gained within a relatively short period. The diverse pictorial programs showcased on the mortuary equipment serve as primary visual aids. Considering the historical backdrop of the state policy of Sinicization, the revival of stone coffins in Luoyang becomes more comprehensible (Huang 1987; Wu 2002).

The focus on Confucianism and the art and culture of the contemporaneous Southern Dynasties, which were founded by the Han Chinese, exemplify the process of Sinicization embraced by the rulers of the Northern Dynasties.35 The reform that took place during the Taihe 太和 period (477–499 CE) in Pingcheng redefined crucial aspects of the empire’s administration and laid the groundwork for localized court ceremonies and rituals. A more systematic and refined new style further developed after the Northern Wei court relocated to Luoyang in 494. According to the History of the Northern Wei, officials undertook construction and design projects for architecture and art that aimed to represent a more Sinicized concept of power. The newly constructed palaces and residences were meticulously planned in accordance with ancient ritual codes and drew inspiration from traditional styles and techniques (Tsiang 2002).

The profound impact of Sinicization on the art world has been extensively explored in recent scholarly works, illuminating that the Northern Wei was not a passive recipient of the new Han tradition. On the contrary, the magnitude of changes in the visual vocabulary and the rapidity with which they took place indicate a dynamic and active campaign to develop new imagery. Through historical records and the examination of stone and bronze artistic remains, scholars have demonstrated that late Northern Wei Luoyang Buddhist art was notably influenced by traditional Chinese sources, particularly the art of the Han dynasty and its contemporary counterparts in the Southern regions, which often featured an integrated and courtly style. Katherine R. Tsiang, for example, has conducted detailed research on the celestial or holy space within Luoyang Buddhist art, providing valuable insights into this specific area of investigation (Tsiang 2002).

Meanwhile, this remarkable preference for filial illustrations in Luoyang can be better comprehended by considering the geographical distribution of these illustrations. Although they were discovered in the north, most attributed authors of the Accounts of Filial Offspring hailed from the territory of the Southern Dynasties. This indicates a significant interaction and exchange between the Northern Wei and the Qi court in the South, as evidenced by recorded regular embassies between the two.

Furthermore, the Sinicization process in Luoyang not only facilitated the revival of filial paragons in the mortuary space but also suggested a deliberate separation of the roles and symbolic significance between the mortuary visual world from the Buddhist space. Through visual representation, the teachings of filial piety were potentially transferred from the Buddhist realm back to the context of ancestor worship within burials.

A crucial element in shaping this division between the mortuary and the Buddhist, as I argue, lies in the heightened significance of filial piety within the realm of rituals. The hierarchical structure within families is believed to be divinely sanctioned (孝悌之至,通于神明). Recent research conducted by Xu Jin highlights that filial illustrations on the mortuary equipment from Luoyang are often arranged in accordance with two principles: the family member principle and the principle of life and death. This theory diverges from the previous one that argues for a sequential order based on the textual references, indicating deliberate and thoughtful visual design choices. The principle of life and death distinguishes between stories that emphasize nurturing the living and those that focused on the deceased, underscoring the importance of these stories within the mortuary context. Additionally, the careful sequencing of these filial stories prominently features the parents’ scene at the center, reminiscent of the tradition of depicting portraits of the deceased couple to serve as the focal point of ancestral sacrifice and worship within the tomb space (Xu 2017, p. 172; Lin 2003, p. 222).

In addition, the emphasis of state policy on standardizing the visual representation of filial piety is further supported by the disappearance of filial paragons immediately following the division of North China between the Eastern Wei (534–550 CE) and the Western Wei (535–556 CE). From the mid-sixth century onwards, new pictorial programs featuring immortals and gatherings of nobility replaced the filial paragons on mortuary equipment (Xu 2017, Introduction). This transition, underscoring the evolving priorities and shifting cultural landscape during that period, attests to the crucial role of court sponsorship in this age of turmoil.

Considering the distinct symbolic and ritual significance associated with these filial paragons within the funerary setting, a clear separation between the mortuary and Buddhist realms becomes imperative. To put it another way, the need to impart the teachings of filial piety through the Buddhist narrative of Śyāma faced a formidable challenge posed by the growing importance of traditional Han filial paragons. As Keith Knapp aptly states, the prevalence of filial paragon illustrations helps elucidate how Confucianism successfully permeated and assumed dominance over the values and ritual practices of the literati, despite its waning philosophical vigor (Knapp 2005, p. 8).

6. Conclusions: In between the Visual and Textual Traditions

This study demonstrates that the acceptance of Śyāma jātaka within local Chinese society was not a straightforward and continuous procession. Its initial popularity in the fifth century was subsequently followed by a period of silence in the early sixth century. The story’s later revival in the second half of the sixth century was limited to the Hexi Corridor and executed in a completely new compositional style.

These visual pieces of evidence present a challenge to the conventional discourse that attributes the tale’s popularity solely to its teaching of filial piety, highlighting the dynamic and fluctuating nature of its reception and circulation within Chinese society. To a degree, the conventional discourse on filial piety was shaped by a preference of textual sources. My research offers an illustrative example of the complexities involved in the interaction between textual and visual mediums when transmitting Buddhist teachings in a changing cultural landscape. By arguing for the “tension between the textual and visual traditions,” I aim to highlight the different logic of transmitting didactic teachings to different groups of viewers, as well as the distinct capacities of textual and visual evidence in representing historical transitions. This study reveals the challenges associated with utilizing texts alone to reconstruct the popularity of certain narratives after their initial translation era. However, often, studies of certain visual representations of jātaka stories focus on aligning the images with surviving texts, treating the visual tradition of these stories primarily as a static portrayal of specific texts and a pure embodiment of the teachings of filial piety, disregarding the intricate nature of images in terms of dissemination, adaptation, and perception. In addition, it is important to recognize that illustrations of jātakas possess inherent ritual and symbolic functions that are shaped by the immediate political and cultural contexts in which they are created. By acknowledging the historicity and materiality of these visual sources in this study, a wealth of evidence emerges, providing a deeper understanding of how Buddhist jātakas were perceived and interpreted in early medieval China.

This study also offers an opportunity to reflect on the Sinicization model employed in previous scholarship to comprehend the concept of filial piety. In recent scholarship, the historical issues associated with the Sinicization model have been critically examined. As pointed out by John Kieschnick, the broad focus on Sinicization “is too crude to be useful” (Kieschnick 2003, p. 19). Embracing this revisionist perspective, it becomes evident that the transmission of the Śyāma jātaka in the visual culture is not solely a linear progression from India to China, nor is it confined to the emphasis on the teaching of the filial piety. Rather, it encompasses a multifaceted adaptation spanning various dimensions, including the geographical transition from Pingcheng to Luoyang, the temporal shift from the fifth to the early sixth century, and the constantly shifting interactions with the existing art tradition in China. By acknowledging the immediate pictorial, historical, and religious contexts, a more nuanced understanding can be achieved, providing a more comprehensive analysis of this complex subject matter.

Last but not least, another noteworthy aspect highlighted in this study is the importance of considering jātakas in relation to one another in order to fully comprehend the reception and localization of Buddhist narratives in China, especially the process of appropriating an unfamiliar narrative from a different cultural tradition. It is essential to analyze how jātakas were paired, which specific episodes were selected, and how the narrative emphasis of each story was modified.

Funding

Major project of the National Social Science Foundation of China: Indian Art and Literary Theories in Classical Sanskrit Literatures: Translation and Studies on Fundamental Works: 18ZDA286.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviation

| T. | Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō-era new edition of the Buddhist canon), 1924–1935, edited by Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎 (1866–1945) and Watanabe Kaikyoku 渡辺海旭 (1872–1932) et al. 100 vols (Tokyo: Taishō issaikyō kankōkai). |

Notes

| 1 | A Jātaka is a story about one of a past life of the Buddha. Therefore, jātakas are also called the birth stories of the Buddha. Many such stories form an important genre of Buddhist literature. See (Appleton 2020), https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780195393521/obo-9780195393521-0020.xml, accessed on 13 May 2023. |

| 2 | So far, no pictorial remains of jātaka tales survive from the Southern Dynasty. Overall, evidence of Buddhist art of the Southern Dynasties is extremely rare, with only a very small number of stone and bronze sculptures preserved in situ or discovered later. Yet, the influence exerted by the art of the Southern Dynasties on that of the Northern Dynasties has been a crucial question in debate among scholars. For a detailed discussion, see (Tsiang 2002, pp. 225–26.) |

| 3 | For more information of the storyline, also see (Wray et al. 1972; Shaw 2006). |

| 4 | Other than the two versions, another version is preserved in Dao’an’s 道安 catalogue, as recorded by Chu Sanzang Jiji 出三藏記集 by Sengyou 僧佑, T2145, vol. 3, pp. 17–18. This version is translated by an anonymous in the Western Jin. |

| 5 | Huijiao mentions Shan song 睒頌 (Eulogy of Shanzi). See T50, 415. A recent study of Xing Guang also discusses the reference of the Śyāma jātaka in Weimo yiji (A Commentary on the Vimalakīrti Nirdesa Sūtra), which was composed by Huiyuan 慧遠 during the Sui dynasty. See (Guang 2022, pp. 85–87). |

| 6 | See (Strong 1983; Schopen 1984, 1997). Guang Xing’s recent article combs through evidence in early Buddhist resources, the Nikāyas and Āgamas. See (Guang 2016a, 2016b). |

| 7 | For the Pāli version, see (Fausbøll 1896, vol. VI, pp. 68–95). For the English translation, see (Cowell and Rouse 1957, vol. VI, pp. 38–52). |

| 8 | See (Ch’en 1968, p. 83; Liu 2020). Guang pinpoints the Pāli and the Mahāvastu versions particularly, but not contending for any direct source text of the Chinese versions. See (Guang 2022, p. 90). |

| 9 | Surviving Sanskrit and Pāli texts are generally dated later than the earlier Chinese translations of Buddhist texts. For an overview, see (Nattier 2008). |

| 10 | This is an abbreviated version based on Kenneth Ch’en’s translation. See (Ch’en 1968, p. 85). Additionally, see Foshuo Pusa Shanzi jing, T03, no. 174. |

| 11 | It is a compositional feature that is unique at Ajanta to arrange murals based on locations where a plot takes place. In Cave 10, for instance, the story is shown in two main sections, the section centered on the forest life on the left, and that of the palace on the right, resulting in possible chronological difference among scenes taken place in the same location. See (Schlingloff 1988, 2013). The very similar composition of the Śyāma jātaka by location is also found employed in Thai murals dated in much later periods. Elizabeth Wray provided a focused study. See (Wray et al. 1972). |

| 12 | Despite the Śyāma jātaka’s popularity in general, it is not found prevalently prominent in major Gandharan or Central Asian sites. Remains from Bamiyan in Afghanistan and some Buddhist kingdoms located along the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert, such as Khotan, do not show traces of the story. |

| 13 | Similar to early Buddhist reliefs in Sanchi, Kizil jātaka illustrations adopt a synoptic mode that encapsulates multiple elements of the story into a single space with no chronological sequence. See Le Coq and Waldschmidt (1922–1933); Zhu (1993); Xinjiang Weiwuer zizhiqu wenwu guanli weiyuanhui et al. (1997); Schlingloff (2000). |

| 14 | As Gao Haiyan observed, it remains in question if the statue dated to 427 is a fakery copied after the statue of 455 according to their striking similarities, the scarcity of surviving statues from the early fifth century. See (Gao 2017a, 2017b). In addition, these statues, bearing execution dates in inscriptions, date about two decades earlier than reliefs in Yungang Grottoes. Therefore, some recent study that refers to Yungang reliefs as the earliest examples requires further revision. |

| 15 | The mural in Sui Cave 124 was brought away by the Oldenburg expedition of 1914–15 and is now in preservation in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. No. Dh 197–198. See (Giès and Cohen 1995; Yagi 2012). |

| 16 | Tan Yao directly participated in the design of the five colossal cave temples, which were considered in honor of the five emperors of the Northern Wei, from Taizu 太祖 onwards. See (Su 1996; Yagi 1997; Hu 2005; Peng 2017; Yi 2017). |

| 17 | See Fei Changfang 費長房, Lidai sanbao ji 歷代三寶記, T49, no. 2034, 85b05. Daoxuan 道宣, Xu Gaoseng zhuan 續高僧傳, T50, no. 2060, 427c27. Da Tang neidian lu 大唐內典錄, T55, no. 2149, 267b28. |

| 18 | On Xiao Jing, see (Cai 1970). |

| 19 | Such as “苟孝悌之至,无所不通” in his conversation with the official Mu Liang 穆亮. Wei Shu, vol. 27, p. 669. |

| 20 | Wei Shou, Wei Shu, vol. 83, p. 1819. |

| 21 | A constant tension between Buddhist practices and the Chinese traditional virtues lies in the contrast between monastic order of abstaining from household life and filial piety. See (Guang 2022, chp. 3, p. 83; Winston 2006). |

| 22 | For an overview of stele production in Henan in late Northern Wei, see (Wong 2004, chp. 6). |

| 23 | For a detailed study of the cave’s pictorial programme and relevant scholarship, see (McNair 2007). |

| 24 | The imagery represents the legendary discourse between the famous Buddhist layman Vimalakīrti and the Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī. The story was first translated into Chinese in the third century, whereas its artistic repertory developed without prototypes in southern China around the fourth century. Two versions of the story were circulating at the time: the Vimalakīrti Sūtra and the Lotus Sūtra. Yet, none of the temple paintings in the south have survived. Most surviving representations are stone reliefs from the north in the fifth and sixth centuries. See (Bunker 1968). Many studies have debated this issue. For its textual tradition, see (Zürcher 1959, pp. 50–70; Lamotte 1962). |

| 25 | The emperor’s procession relief is currently preserved in the Metropolitan Museum, while the empress’s procession is kept at the Nelson-Atkins Museum. |

| 26 | Surviving texts use different names to refer to the prince, indicating the circulation of various textual editions in both India and China. In this study, Sudāna (Xudana 須大拏) is used to refer to the prince, the other names for him being pointed out when relevant. Among the eight surviving Chinese texts, the prince is called Xudana in the two texts from the third century CE and three Dunhuang manuscripts, Yiqiechi 一切持 in the pseudo-Pusa benyuan jing of the sixth century, and Weishifu duoluo 尾施縛多羅 in Yijing’s translation from the seventh century. Xudana, the name most often used, derives from Sudāna in the early Indian texts. This is different from Vessantara in the Pali tradition and Viśvantara, another name used in the Sanskrit tradition. For major studies on the story’s textual tradition, see (Chen 2013a, 2013b; Nattier 2008; Bokenkamp 2006). |

| 27 | In some versions, to add to Sudāna’s problem, the god Śakra disguises himself as another Brahman and asks Sudāna for Mādrī. In the Pali tradition, the story’s status in depicting the last incarnation of the Buddha also indicates its importance for achieving Buddhahood. See (Kim 2009; Zhao 2017). |

| 28 | Its initial popularity at early Buddhist sites in India may have been related to the story’s sequence in the textual tradition, as it is considered to be the last incarnation of the Buddha in the Pali canon. For an overview of its dissemination in early Indian tradition. |

| 29 | In Binyang Central Cave, the figure is located to the right of the panel, sitting in a mountainous setting, and wearing a robe that covers his head (see Figure 10). His appearance is typical of representations of meditating monks in China since the late fifth century. See (Chen 2016). A figure rendered in a very similar way also appears in the Xiahou Xianmu 夏侯顯慕 Stele of the 560s. On excavation of the Xiahou Xianmu statue, see (Han 1980). However, in a relief carving on the pedestal from the Penn Museum, the figure is rendered completely differently in the look of a Daoist practitioner or laity holding a zhuwei 麈尾 in their hands. See (James 1989; Liu 1997, 2001; Abe 2001; Huang 2012). |

| 30 | Taizi Xudana jing, T. 171, 3. 421a. In Taizi Xudana jing, the episode starts with the following account: 山上有一道人名阿州陀,年五百歲,有絕妙之德。太子作禮,却住白言:“今在山中何所有好甘果泉水可止處耶?”阿州陀言:“是山中者普是福地,所在可止耳。”……道人問太子:“所求何等?”太子答言:“欲求摩訶衍道。”道人言:“太子功德乃爾,今得摩訶衍道不久也。太子得無上正真道時,我當作第一神足弟子。”道人即指語太子所止處,太子則法道人結頭編髮,以泉水果蓏為飲食…… There is an ascetic named Azhoutuo in the mountains, who is five hundred years old and renowned for his excellent virtue. The prince paid homage to him and said, ‘Are there any good places with fruits and springs where one can stay in the mountains?’ Azhoutuo replied, ‘All the places in this mountain are blessed land for residing.’ … The ascetic asked the prince, ‘What are you looking for?’ and the prince replied, ‘I am looking for the Mahāyāna path.’ The ascetic replied, ‘The prince has good virtue. You will achieve the Mahāyāna path soon. Once you achieve what you pursue, I would like to be your first follower.’ The ascetic showed the prince a place to reside. The prince learned from the ascetic how to braid hair and survive on springs, fruit, and vegetables… |

| 31 | Azhoutuo’s defining characteristics—his good moral deeds and his longevity—intriguingly coincide with the works by local Chinese authors about ascetics who seek immortality in the mountains. In indigenous Chinese writings on immortality, ascetics can live for five hundred years. Similar accounts of immortals living for five hundred years longevity are scattered throughout Baopuzi 抱樸子 and Shenxian zhuan 神仙傳. For major studies of Daoist ascetics and immortality, see (Kohn 1989; Poo 1995; Bokenkamp 1997; Campany 2002, 2009). On Boapuzi and Shenxianzhuan, see (Baopuzi neipian jiaoshi, 80–81; Shenxian zhuan 153). |

| 32 | For a glimpse of recent studies on the importance of meditation in early medieval Chinese Buddhism, see (Chen 2014; Greene 2014, 2021a, 2021b). On artistic traditions related to meditation, see (Liu 1978; He 1980; Hsu 2002). |

| 33 | For an overview of filial paragons in medieval China, see (Wang 1999, 2003; Knapp 2005, 2012; Zheng 2002, 2012, 2013; Xu 2015, 2017). |

| 34 | These accounts were usually privately compiled collections ranging in length from one to thirty chapters. The current title serves as a general reference. None of those dated to the Six Dynasties has survived. Most fragments were preserved in the Tang and Song encyclopedia. Only three fully intact versions survive today. One is attributed to Tao Yuanming, and two manuscripts have survived in Japan. |

| 35 | The southern influence in both style and subject matter on late Northern Wei art has long been a central topic of art historians. |

References

Primary Sources

Baopuzi neipian jiaoshi 抱朴子内篇校釋 (The Master Who Embraces Simplicity: Inner Chapters), by Ge Hong 葛洪 (283–343 CE), ed. Wang Ming 王明 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1985).Gaoseng zhuan 高僧傳 (Biographies of Eminent Monks), by Huijiao 慧皎. T. 50, no. 2059. Genben shuo yiqie youbu pinaiye posengshi 根本說一切有部毗奈耶破僧事, translated by Yi Jing 義淨 (635–713 CE) of Saṇghabheduvastu, T. 1448.Genben shuo yiqie youbu pinaiye yaoshi 根本說一切有部毗奈耶藥事, translated by Yi Jing 義淨 (635–713 CE) of Bhaiṣajyavast, T. 1450.Fayuan zhulin 法苑珠林 (A Grove of Pearls in the Garden of the Dharma). T. 53, no. 2122.Foshuo Pusa Shanzi jing 佛說菩薩睒子經 (Śyāmakajātaka sūtra). T. 3, no. 174; T. 3, no. 175a, c, translated by Shengjian 聖堅.Jātāka-mālā, by Āryaśura, ed. by Hendrik Kern (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1891).Jinglü yixiang 經律異相 (Peculiarities of the Sūtras and Vinayas), by Baochang 寶唱, T. 53, no. 2121.Liudu ji jing 六度集經 (The collection of scriptures on the six pāramitās), translated into Chinese and compiled by Kang Senghui 康僧會 (ca. 280 CE), T. 152, 3.7c28–11a26.Pusa benyuan jing 菩薩本緣經 (The sūtra of bodhisattva’s fundamental vows), probably translated into Chinese by Zhi Qian 支谦 (fl. 222–252 CE), T. 153.Sengjialuocha suoji jing 僧迦羅剎所集經 (Sūtra Compiled by Saṅgharakṣa), translated into Chinese by Saṁghabhūti and etc. T. 4, no. 194.Shenxian zhuan 神仙傳校释 (Traditions of divine transcendents), by Ge Hong 葛洪, ed. Hu Shouwei 胡守為 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2010).Taizi Xudana jing 太子須大拏經 (Sūtra of the prince Sudāna), translated into Chinese by Shengjian 聖堅 (fl. 400 CE), T. 171.Za baozang jing 雜寶藏經 (Saṃyuktaratna Piṭaka Sūtra), translated into Chinese by Tan Yao 昙曜 and Kekaya 吉迦夜, T. 4, no. 203.Secondary Literature

- Abe, Stanley K. 2001. Provenance, Patronage, and Desire: Northern Wei Sculpture from Shaanxi Province. Ars Orientalis 31: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, Naomi. 2020. Jātaka. Oxford Bibliographies. Available online: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780195393521/obo-9780195393521-0020.xml (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Bell, Alexander. 2000. Didactic Narration: Jataka Iconography in Dunhuang with a Catalogue of Jataka Representations in China. Hamburg and London: Lit Verlag Münster. [Google Scholar]

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R. 1997. Early Daoist Scriptures. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R. 2006. The Viśvantara-Jātaka in Buddhist and Daoist Translation. In Daoism in History: Essays in Honour of Liu Ts’un-Yan. Edited by Benjamin Penny. London: Routledge, pp. 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Robert. 1997. Narrative as Icon: The Jātaka Stories in Ancient Indian and Southeast Asian Architecture. In Sacred Biography in the Buddhist Traditions of South and Southeast Asia. Edited by Juliane Schober. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 64–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bunker, Emma C. 1968. Early Chinese Representations of Vimalakīrti. Artibus Asiae 30: 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Rukun. 1970. Xiaojing tongkao 孝經通考 (Study on ‘Xiao Jing’). Taipei: Shangwu yinshuguan. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Weitang. 2004. Dunhuang bihua zhong de Shanzi bensheng gushihua: Cong e‘cang Mogaoku di 433 ku Shanzi bensheng gushihua tanqi 敦煌壁畫中的睒子本生故事畫——從俄藏莫高窟第433窟睒子本生故事畫談起. Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 5: 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Campany, Robert F. 2002. To Live as Long as Heaven and Earth: A Translation and Study of Ge Hong’s Traditions of Divine Transcendents. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campany, Robert F. 2009. Making Transcendents: Ascetics and Social Memory in Early Medieval China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ch’en, Kenneth. 1968. Filial Piety in Chinese Buddhism. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 28: 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch’en, Kenneth. 1973. The Chinese Transformation of Buddhism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Ming. 2013a. Xinchu jiantuoluo yuben xudana taizi gushi bijiao yanjiu 新出犍陀羅語本須大拏太子故事比較研究 (A comparative Study of the Sudāna Jataka in the recently discovered Gandhari text). In Wenben yu yuyan: Chutu wenxian yu zaoqi fojing bijiao yanjiu 文本與語言——出土文獻與早期佛教比較研究 (Texts and languages: A comparative study of unearthed documents and early Buddhist). Edited by Ming Chen. Lanzhou: Lanzhou Daxue Chubanshe, pp. 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Ming. 2013b. Xinchu jiantuoluo yuben xudana taizi minghao jiqi yuanliu bianxi 新出犍陀羅語本須大拏太子名號及其源流辨析 (The appellation of prince Sudāna and its linguistic origin in the recently discovered Gandhari text). In Wenben yu yuyan: Chutu wenxian yu zaoqi fojing bijiao yanjiu 文本與語言——出土文獻與早期佛教比較研究 (Texts and languages: A comparative study of unearthed documents and early Buddhist). Edited by Ming Chen. Lanzhou: Lanzhou Daxue Chubanshe, pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jinhua. 2014. Meditation Traditions in Fifth-Century Northern China: With a Special Note on a Forgotten ‘Kaśmīri’ Meditation Tradition Brought to China by Buddhabhadra (359–429). In Buddhism Across Asia: Networks of Material, Intellectual and Cultural Exchange. Edited by Tansen Sen. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 1, pp. 101–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Suyu. 2016. Chanzong zushi xiang de tuxiang moshi yanjiu 禪宗祖師像的圖像模式研究 (Pictorial modes of Chan masters). Shijie zongjiao yanjiu 世界宗教研究 4: 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Bonnie. 2011. Exchange and a Renewed Perspective on Stone. In Gudai muzang meishu yanjiu 古代墓葬美術研究 (Study on the Ancient Tomb Art). Edited by Wu Hung and Zheng Yan. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, vol. 1, pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- Cowell, E. B., and W. H. D. Rouse. 1957. The Jātaka or Stories of the Buddha’s Former Births. London: Luzac, vol. VI. [Google Scholar]

- Dehejia, Vidya. 1990. On Modes of Visual Narration in Early Buddhist Art. The Art Bulletin 72: 374–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehejia, Vidya. 1997. Discourse in Early Buddhist Art: Visual Narratives of India. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. [Google Scholar]

- Donohashi, Akiho. 1978. Tonkō hekiga ni okeru honshōzu no zenkai 敦煌壁畫における本生圖の展開 (Narrative development in Dunhuang jataka painting). Bijutsushi 美術史 1: 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang Wenwu Yanjiusuo 敦煌文物研究所, ed. 1980–1984. Zhongguo shikusi: Dunhuang Mogaoku 中國石窟寺:敦煌莫高窟 (Chinese Grottoes: Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes). 5 vols. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, Tōkyō: Heibonsha. [Google Scholar]

- Fausbøll, V. 1896. Jātaka: Together with Its Commentary. London: Kegan Paul Trench Trübner & Co., Ltd., vol. VI. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Haiyan. 2017a. Sheshensihu bensheng yu Shanzi bensheng tuxiang yanjiu 捨身飼虎本生與睒子本生圖像研究 (Research on Mahasattva Jataka and Syama Jataka). Lanzhou: Gansu jiaoyu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Haiyan. 2017b. Shixi sheshen sihu Bensheng yu shanzi bensheng tuxiang de duiying zuhe guanxi 試析捨身飼虎本生與睒子本生圖像的對應組合關係 (On the Combination of Mahasattva Jātaka and Śyāma Jātaka). Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 165: 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Giès, Jaques, and Monique Cohen, eds. 1995. Sérinde, Terre de Bouddha (Catalogue of the Exhibition in the Grand Palais, Paris). Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Eric M. 2014. Healing Breaths and Rotting Bones: On the Relationship between Buddhist and Chinese Meditation Practices during the Eastern Han and Three Kingdoms Period. Journal of Chinese Religions 42: 144–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, Eric M. 2021a. Chan Before Chan: Meditation, Repentance, and Visionary Experience in Chinese Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Eric M. 2021b. The Secrets of Buddhist Meditation: Visionary Meditation Texts from Early Medieval China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, Leslie. 1990. A Concordance of Buddhist Birth Stories. Oxford: Pāli Text Society. [Google Scholar]

- Guang, Xing. 2016a. The Teaching and Practice of Filial Piety in Buddhism. Journal of Law and Religion 31: 212–26. [Google Scholar]

- Guang, Xing. 2016b. Wei Jin Nanbeichao shiqi de Fojiao xiaodao yanjiu: Yi ‘Shanzi jing’ he ‘Yulanpen jing’ weizhu 魏晉南北朝時期的佛教孝道研究:以《睒子經》和《盂蘭盆經》為主. Zongjiao Yanjiu 宗教研究 1: 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Guang, Xing. 2022. Filial Piety in Chinese Buddhism. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Ziqiang. 1980. Anhui Boxian Xianpingsi faxian Bei Qi shike zaoxiangbei 安徽毫縣鹹平寺發現北齊石刻造像碑 (Northern Qi stone statue discovered in Xianping Temple, County Bo, Anhui). Wenwu 文物 9: 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- He, Shizhe. 1980. Mogaoku Beichao shiku yu changuan 莫高窟北朝石窟與禪觀 (Northern Wei grottoes at Mogao and the practice of meditation). Dunhuang Xue Jikan 敦煌學輯刊 1: 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Higashiyama, Kengo. ; Translated by Li Mei. 2011. Dunhuang Benshengsheng gushihua de xingshi: Yi shanzi benshengtu wei zhongxin 敦煌石窟本生故事畫的形式——以睒子本生圖为中心 (Narrative illustrations from Dunhuang: A Case Study of Shanzi story). Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 2: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Chen-fa. 1999. Beichao zhongyuan diqu ‘Xudana bensheng tu’ chutan 北朝中原地區<須大拏本生圖>初探 (On representations of Sudāna Jataka from the central plain of the Northern dynasties). Meishushi Yanjiu Jikan 美術史研究集刊 6: 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Eileen Hsiang-Ling. 2002. Visualization Meditation and the Siwei Icon in Chinese Buddhist Sculpture. Artibus Asiae 62: 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Wenhe. 2005. Yungang shiku mouxie ticai neirong he zaoxing fengge de yuanliu tansuo 雲岡石窟某些題材內容和造型風格的源流探索 (A survey of the themes and stylistic features of stories depicted in the Yungang Grotto). In 2005 nian Yungang fuoji xueshu yantao hui lunwen ji 2005年雲岡國際學術研討會論文集 (Proceedings for the 2005 International Conference on Yungang). Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Minglan. 1987. Luoyang Bei Wei shisu shike xianhua ji 洛陽北魏世俗石刻線畫集. Beijing: Renmin meishu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Shih-shan Susan. 2012. Picturing the True Form: Daoist Visual Culture in Traditional China. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- James, Jean M. 1989. Some Iconographic Problems in Early Daoist-Buddhist Sculptures in China. Archives of Asian Art 42: 71–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J. J., trans. 1952. Mahāvastu: Translated from the Buddhist Sanskrit. London: Luzac and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Khoroche, Peter, trans. 2017. Once a Peacock, Once an Actress: Twenty-Four Lives of the Bodhisattva from Haribhaṭṭa’s “Jātakamālā”. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kieschnick, John. 2003. The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jinah. 2009. Illustrating the Perfection of Wisdom, The Use of the Vessantara Jātaka in a Manuscript of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitāsūtra. In Prajñādhāra Essays on Asian Art, History, Epigraphy and Culture, in Honour of Gouriswar Bhattacharya. Edited by Gerd J. R. Mevissen and Arundhati Banerji. New Delhi: Kaveri Books, vol. 2, pp. 261–72. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, Keith. 2005. Selfless Offspring: Filial Children and Social Order in Medieval China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’I Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, Keith. 2012. Sympathy and Severity: The Father-Son Relationship in Early Medieval China. Extreme-Orient Extreme-Occident Hors-Serie 1: 113–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, Livia, ed. 1989. Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lamotte, Etienne. 1962. L’Enseignement de Vimalakirti. Louvain: Publications Universitaires. [Google Scholar]

- Le Coq, Albert von, and Ernst Waldschmidt. 1922–1933. Die Buddhistische Spätantike in Mittelasien: Ergebnisse der Kgl.-Preussischen Turfan-Expeditionen. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Yu-min. 1993. Dunhuang 428 ku xin tuxiang yuanliu kao 敦煌四二八窟新圖像源流考 (Iconography in Dunhuang Cave 428). Gugong Xueshu Jikan 故宮學術季刊 4: 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Chongfeng. 2000. Dunhuang Mo Gaoku Beichao wanqi dongku de fenqi yu yanjiu 敦煌莫高窟北朝晚期洞窟的分期與研究 (Chronology of Dunhuang Mogao Cave-temples from the late Northern Wei). In Dunhuang yanjiu wenji: Dunhuang shiku kaogu bian 敦煌研究文集:敦煌石窟考古編 (Collections of Essays on Dunhuang Studies: Archaeology). Lanzhou: Gansu minzu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jingjie. 1996. Zoxiangbei fo bensheng benxing gushi diaoke 造像碑佛本生本行故事雕刻 (Buddhist jatakas and life stories of the Buddha on figured Steles). Gugong Bowuyuan Yuankan 故宮博物院院刊 4: 66–83. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jingjie. 2016. Nan Beichao Suidai Saduo taizi bensheng yu Xudana taizi bensheng tuxiang 南北朝隋代薩埵太子本生與須大拏太子本生圖像 (Images of Mahasattva and Sudāna jatakas from the Northern and Southern dynasties and the Sui dynasty). Shikusi Yanjiu 石窟藝術研究 1: 125–73. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yongning, ed. 2001. Dunhuang shiku quanji: Bensheng yinyuan gushi huajuan 敦煌石窟全集:本生因緣故事畫卷 (Dunhuang grottoes: Jatakas and Avadanas). Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Liling. 1998. ‘Za baozang jing’ jiqi gushi yanjiu 《雜寶藏經》及其故事研究 (Za baozang jing and Its Stories). Taipei: Fagu wenhua. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Sheng-chih. 2003. Hokuchou jidai niokeru sog uno zuzou to kino—Sekkanshou iei no hakanushi shōzō to koshidenzu o reitoshite 北朝時代における葬具の図像と機能石棺床囲屏の墓主肖像と孝子伝図を例として. Journal of the Japan Art History Society 154: 207–26. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Huida. 1978. Bei Wei shiku yu chan 北魏石窟與禪 (Northern Wei grottoes and the practice of meditation). Kaogu Xuebao 考古學報 3: 337–52. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Qian. 2020. Shanzi gushi de liubian 睒子故事的流變 (Evolution of the story of Shanzi). Zhongguo Guojia Bowuguan Guankan 中國國家博物館館刊 9: 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yang. 1997. Manifestation of the Dao: A Study in Daoist Art from the Northern Dynasty to the Tang (5th–9th Centuries). Ph.D. thesis, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yang. 2001. Origins of Daoist Iconography. Ars Orientalis 31: 31–64. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, John. 1918. A Guide to Sanchi. Bombay: Superintendent Government Printing. [Google Scholar]

- McNair, Amy. 2007. Donors of Longmen: Faith, Politics, and Patronage in Medieval Chinese Buddhist Sculpture. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, Seiichi 水野清一, Toshio Nagahiro 长广敏雄, and Zenryū Tsukamoto 塚本善隆. 1980. Kanan Rakuyō Ryūmon sekkutsu no kenkyū 河南洛陽龍門石窟の研究. 3 vols. Kyōto: Dōhōsha. First published 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Julia K. 1995. Buddhism and Early Narrative Illustration in China. Archives of Asian Art 48: 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Julia K. 1998. What is ‘Chinese Narrative Illustration’. The Art Bulletin 80: 602–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattier, Jan. 2008. A Guide to the Earliest Chinese Buddhist Translations: Texts from the Eastern Han and Three Kingdoms Periods. Tokyo: The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology, Soka University. [Google Scholar]