2. Gist of Images: Religious Concept of “Destiny Is Impermanent” and Confucian Regulation

Due to the open and compatible religious policy implemented by the rulers of the Yuan Dynasty, Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism were prevalent in Jianyang. Confucian doctrines were combined with Taoism and Buddhism. The phenomena of “three religions of the same source” and “three-in-one” were prominent. As an intuitive representative of the culture accepted by the masses, the images in Jianyang popular literature, such as “Three Points 三分事略”, “New Compilation of Lianxiang Soushen Guangji 新編連相搜神廣記”, and “Quanxiang Pinghua”, presented the multidimensional integration of the political and religious order of Confucianism and the religious concepts of Buddhism and Taoism. Among them, “Quanxiang Pinghua”, published by Jianyang Yushi, was engraved with 246 block prints on top of texts. It depicted the historical stories from the Warring States to the Three Kingdoms in a serial-picture form, comprehensively showcasing the rise and fall of dynasties, wars, fighting between gods and demons, legendary heroes, and other visual landscapes in the cultural perspective of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. Multi-religious cultures were practiced visually by the image symbols in the fiction through the relationship between religious concepts and power order.

The expression strategy of the images in “

Quanxiang Pinghua” was to construct a composite theme of Confucian order and the concept of “destiny is impermanent” in Buddhism and Taoism with the aid of graphic symbols. Qingkun Yang pointed out that the concept of “destiny is impermanent” was a new political and religious meaning proposed by Confucianism based on the “Yin-Yang and Five-Element 陰陽五行說” theory of Buddhism and Taoism. It provided an important foundation for imperial power, politically integrating a vast country. God’s will had the authority to govern local gods and beliefs. When kings and the common people disrupted the harmonious order of the universe, the response of God was to warn first and punish later. At the social level, the concept of “the god’s will” was accepted by Confucianism and formed a political and religious power system that was mighty and rich in moral connotation (

Yang 2007, p. 140).Through the narrative of religious images, “

Quanxiang Pinghua” constructed the concept of “destiny is impermanent” under Confucian regulation. For the convenience of discussion, the author compiled the narrative entries of the fiction’s illustrations, as shown in

Table 1.

Table 1 lists 61 religious images, accounting for a relatively high proportion. These images depict mythological landscapes of Buddhism and Taoism, such as the portrayal of the Taoist God Lei Zhenzi 雷震子 in “King Wen Met Lei Zhenzi” in the “

Book of Wu King Attacking Zhou”, Taoist immortals fighting with spells in the “Decoded the Enchantment Array” in the “Yueyi Tried to Obtain Qi Pinghua”, and the scene of Buddhist reincarnation in the “Zhongxiang judged cases in the Netherworld” in the “Records of the Three Kingdoms”. Illustrations assist the narrative of the fictional plots, which not only possess the characteristic of religious narrative, but also visually demonstrate ethical order. The macro narrative framework of “

Quanxiang Pinghua” constructs the concepts of “destiny is impermanent” and “Yin-Yang and Five-Element”. According to the historical outline, the editors of the fiction fictionalized the narrative of religion, such as the gods’ protection with their wings, gods helping people out of doom, fights between gods and devils, and the reincarnation of cause and effect. They infused these added immortal models with the Confucian ethics of “the five virtues are transferring, and the governance is appropriate for each 五德轉移, 治各有宜”. Then, how do the images associated with the texts of the fiction reflect the Confucian theme in public events, and how did the painters integrate religious images of Buddhism and Taoism? The premise for discussing the ethical cognition of Confucianism in the images of “

Quanxiang Pinghua” is, first of all, the illustrations shape religious images to meet the political and religious theme of Confucianism.

The illustrations of “

Quanxiang Pinghua” delicately construct Confucian political and religious principles through the portrayal of mythological images of Taoism and Buddhism. Taking the characterization of Lüshi in the image system of “the Sequel to the

Book of the Former Han Dynasty” as an example, in the context of texts, Lüshi played a key role in the fortune of the early Han Dynasty. She assisted the monarch in unifying the world, beheading Hanxin 韓信, and killing Yingbu 英佈, Pengyue 彭越, and other sages to consolidate power. After usurping the throne, she attempted to support the Lü family in substituting the Han Dynasty with a new regime. The series of illustrations in the novel put Lüshi in the visual field of “destiny” and “Confucianism”. “Hanxin’s Six Subordinate Generals Shot Empress Lü to Avenge Him 韓信下六將為主報仇射呂後圖” depicts that, before Empress Lü, who had subordinated to the force of the Emperor, murdered the virtuous and rebelled against the court, Sunan 孫安, and five other generals wanted to kill Lüji for taking revenge on Hanxin. “Empress Lü finally took the emperor’s blessing and suddenly saw a golden dragon to protect her”. She escaped the disaster (

Figure 1). Once Lüshi broke the order system and went against the will of the gods, the painters hinted at the disaster from the gods with the image of “Dreamed about the Eagle and Dog to Take Her Life.” (

Figure 2). Immediately, Lü’s three-thousand people were killed by Liu’s orthodoxy. Through Taoist symbols, such as the “real dragon” and the “eagle and dog”, the theme of the illustrations focuses on expressing the national order under the divine blessing. The pattern of destiny in the image here is “the divine grant of monarchy”. In the illustration, “the real dragon”, Liubang 劉邦, helps Empress Lü survive, and the six rebellious generals commit suicide in accordance with the scourge of the gods. When Liubang died, Empress Lü went against destiny and supported her own power, then “gods will seize her heart, and the disaster is coming 天奪其心,爵加於犬,近犬禍也”. Taoist symbols construct universal, stable, and unified images in image reading. The materialized dragon, eagle, and dog carry traditional imprints to awaken viewers’ experiences of culture, emotion, and sense. As stated earlier, the prevalent Confucian ideology in Jianyang society was transformed by Zhuxi based on the thought of destiny, “since the beginning of the world, the five virtues are transferring, and the governance is appropriate for each correspondingly. 稱引天地剖判以來,五德轉移,治各有宜,而符應若茲” (

Sima and Han 2022). The core is to make an analogy of the “five virtues of heaven and earth” with gold, wood, water, fire, and earth, which promote and restrain mutually, forming the society with “Yin-Yang the gas of Five-Element, and reconcile the principle of Five-Constancy” (

Li and Wang 1986, vol. 6, p. 101). In terms of the political system, it was characterized as the order of Confucian principles. The pattern of “destiny is impermanent” represented by the illustrations of “the Sequel to the

Book of the Former Han Dynasty” is closely connected with the Confucian principle of “benevolence, righteousness, courtesy, wisdom, and trust”. The painters put Empress Lü’s behaviors under the examination of orthodox ethics. The protection of the gods or the disaster from the gods depended on whether she violated Confucian ethics. Note that, in the “Empress Lü Held a Memorial Ceremony for the King of Han 呂後祭漢王圖” in the last volume, Empress Lü held a memorial ceremony for Liubang after she established her own regime. In the illustration, Liubang, along with the souls of Hanxin, Yingbu, and Pengyue, attacked Empress Lü. When Hanxin shot Empress Lü with an arrow, the “real dragon”, Liubang, was among the ministers (

Figure 3), forming a hostile relationship with the image of Empress Lü. Empress Lü was hit in her left breast by the arrow therewith, in sharp contrast with the scene where she was protected by the real dragon in

Figure 1. Therefore, the purport of “destiny is impermanent” constructed by the illustration is that destiny is the orthodoxy, representing the sacred status of the ruler of the Five Virtues in Confucian order. When the imperial power or the secular world had rebellions, conspiracies, broken proprieties, scourges, and other acts that violated the Confucian “reconcile the principle of five-constancy”, religious gods would use deified omens to warn and punish them and displace auspiciousness with misfortune.

“The Sequel to the Book of the Former Han Dynasty” manifests the ethical theme of benevolence, righteousness, filial piety, and loyalty in Confucian politics through a simple graphic symbol system of Taoism and Buddhism. The monarchy was granted by the gods. The operation of power and the replacement of dynasties should comply with the “Yin-Yang and Five-Virtue” of Confucianism. The religious gods protected the monarchy with “God’s vision”, representing the legitimacy of orthodoxy and auspiciousness. On the contrary, if having violated the “Yin-Yang and Five-Virtue”, the Emperor would be punished by the gods, who would change the Dynasty through invisible volition. In “the Book of King Wu Attacking Zhou”, “King Zhou Dreamed About the Jade Maiden Giving Him The Jade Belt 紂王夢玉女授玉帶圖”, “the Nine-Tailed Fox Exchanged for Daji’s Soul 九尾狐換妲己神魂圖”, and “King Wen was Imprisoned in Jiangli City 文王因囚姜裏圖” indicate the religious view of “destiny is impermanent”. In the first two pictures, the lustful King Zhou of Shang 商紂王 saw the Jade Maiden 玉女 in the ancestral temple 宗廟. The fox demon from Heaven was incarnated as this woman to bring disaster to the Shang Dynasty. In the third picture, when King Wen of Zhou was imprisoned in Jiangli City, a phoenix from Heaven came to worship him. King Wu 武王, the son of King Wen, soon overthrew the Shang Dynasty. In the volume of “Quanxiang Pinghua Records of the Three Kingdoms”, “Zhongxiang was Sent by Gods to be the Judge in the Nether World 天差仲相作陰君圖”, starting with Sima Zhongxiang’s 司馬仲相 trial of Hanxin, Pengyue, and Yingbu in the nether world, the golden-armored gods gave him the immortal Buddha’s ultimatum and conveyed the volition of the gods that Hanxin, Pengyue, and Yingbu would be reincarnated as Caocao, Liubei, and Sunquan and carve up the Han Dynasty, and Sima’s family would unite the three countries according to the volition of the gods. Additionally, through divine selection modes, such as the divine rights of kings, the protection from the gods, and the divine auspiciousness, the religious belief foundation was laid for the establishment of the Dynasty. These illustrations in the fiction reflect Confucian ethics and order in the theme of “the destiny is impermanent” through the creation of the images of Buddhist and Taoist deities and demons, such as the phoenix 天鳳, gold dragon 金龍, Feixiong 飛熊, Tiangong 天公, Shenbing 神兵, demon fox 妖狐, Yinsi 陰司, Hell Magistrate 地獄判官, and Raksha 羅刹.

Overall, the images of immortals in the fiction are the imagination and cognition of the bottom people about Taoism and Buddhism. The translation of its artistic medium is intertwined with the concept of “destiny is impermanent”. Through intuitive visual interpretation and construction, these images form a strong interaction with Confucian principles and ethics and construct the theme of “destiny is impermanent” in the visual relationship.

3. Religious Schema: Spatial Expression of Confucian Political and Religious Order

As a patriarchal ethical religion, Confucianism centered on the etiquette and order of politics and religion. According to Karl Kurger’s research, the concept of “destiny”, popular in Chinese society from the Emperor to ordinary people, contains the universal order of moral principles. Confucianism drew inspiration from the idea of human Heaven in Buddhism and Taoism and closely combined politics with enlightenment (

Karl 1987, p. 104). As Lizhu Fan once said, “The religious systems of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism have always focused on the multiple effects of political ethics and belief education on social order.” (

Fan and Cheng 2021, p. 112). The writing of religious images in the illustrations of “

Quanxiang Pinghua” is the spatial expression of Confucian political and religious order. In terms of the generation of religious images, the ethical enlightenment emphasized in texts determines its source of order. For example, in “Yueyi Tried to Obtain Seven Countries”, “Only by making the people stable can he become the Emperor. Then no one can resist him 保民而王, 莫之能御也”, “one, unfaithful, assist two rulers; two, impiety, far away from parents; three, injustice, try hard to induce the Emperor to commit evil 一不忠者, 佐二主; 二不孝, 远离父母; 三不义, 苦谏帝王行邪” (

Yu 1321–1323b); in the “Qin Merged Six Kingdoms Pinghua 秦併六國平話”, “I hear that those who obey virtue will prosper, those who disobey virtue will perish 吾闻顺德者昌, 逆德者亡” (

Yu 1321–1323b), and “To implement benevolence and justice, one should not rely on violence 夫仁不以勇, 义不以力”, all of them constitute the ethical foundation of Confucian politics and religion reflected in illustrations.

As the critical ending of “the

Book of King Wu Attacking Zhou”, “King Wu beheaded King Zhou and Daji” depicts the ceremony of the beheading King Zhou after he was defeated by King Wu of Zhou. On the right of the illustration, King Wu of Zhou sits in the center, with officials standing on both sides holding tablets 笏 and attendants standing behind holding Huagai 華蓋 (

Figure 4). The incarnation of the beheaded Daji, a nine-tailed demon fox with a human face, is on the left of the illustration, lying on the ground after being scolded by Jiang Ziya 姜子牙 with a demon-subduing mirror. Shangzhou, the King of the conquered nation, kneels and waits for the execution of the “Divine Axe” (

Figure 4). On the right side of the illustration, the center of the power field is shaped by the royal ceremony. Meanwhile, King Wu of Zhou and the kneeling Shangzhou form the order of figure structure’s “superiority and inferiority” based on the logic of social ranking. King Wu was the superior, and King Zhou was the inferior. The fight between Taoist Jiang Ziya and the nine-tailed fox represents the presence of Taoist gods and demons. In the illustration, King Wu watches the overall situation with a posture of sitting upright and looking down. The scenes of gods fighting with demons and the execution of King Zhou are under the inspection of Confucian order. The painters designed the Confucian monarch, Taoist gods and demons, and young servants within a rigorous ethical framework of “superiority and inferiority” of Confucianism. The mythological symbols in the illustrations of the fiction reveal the volition of “destiny is impermanent” and construct the spatial form of Confucian order, implying that both folk religions and royal society should comply with the order of Confucian ethics. Coincidentally, the ending of “the Sequel of Yueyi Tried to Obtain the Seven Countries 樂毅圖七國後集”, “Seven Countries submitted to Qi 七國順齊圖”, depicts the victory of Qi over the allied forces of Yan, Chu, Qin, and Wei, which then worshiped Qi and paid tributes every year. The image represents typical Confucian etiquette order. In the illustration, the regime of the King of Qi is on the left, and the regimes of the four countries are on the right as obedient ministers, constructing the symbolic order of the left outranking the right. The Emperor of the State of Qi, the King Xiang of Qi, sits upright in the middle. The Taoist gods, “Gui Guzi” and “Sun Tzu”, are listed on the left and right with fist-and-palm saluting (

Figure 5). Image symbols, such as landscape screens, Taoist deities, and the worship of obedient ministers, build the political authority of the monarch and highlight the core of Confucian political power, “King Xiang of Qi”. The illustration is themed around the state of Qi, which represents the orthodoxy of Confucian benevolence and righteousness. The assistants on the left and right are Guiguzi and Sun Tzu, proficient in the Taoist magics of gods, demons, and immortals. They have a dialogue with the aggressive politics of the four countries that violated ethical principles, creating a strong contrast in the form of spatial ritual. It metaphorically suggests that the Confucian power order governed Taoism, and feudal lords should comply with the Confucian ethical principle of benevolence and righteousness.

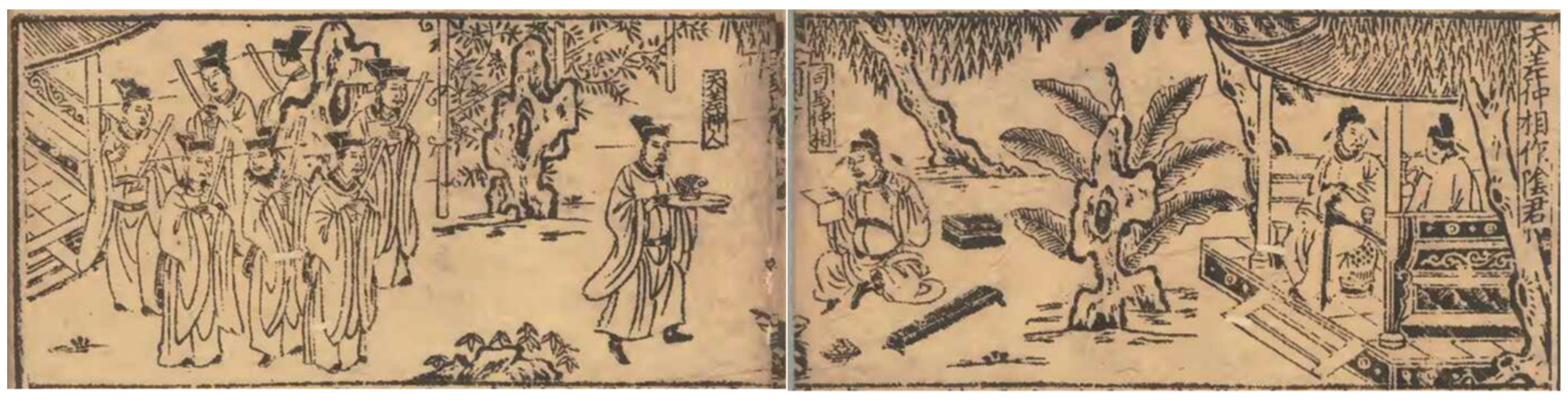

In the order system of illustrations, the order space of Confucianism is characterized by the superiority and inferiority of characters, the size of gods and demons, the importance of official positions, the complexity of ceremonies, and the height of buildings. Through a relatively complete order system, “Quanxiang Pinghua” reflects the ethical meaning of images, of which the gist is the universality of Confucian patriarchal hierarchy. The scene of the trial of Buddhism and Taoism portrayed in the fiction is the spatial expression of Confucian political and religious concepts of superiority, inferiority, loyalty, and filial piety. In the “Complete Records of the Three Kingdoms”, “Zhongxiang Judged Cases of the Netherworld” depicts that Sima Zhongxiang 司馬仲相 was summoned by the gods to Hell to hear the injustice of Hanxin, Yingbu, and Peng Yue in “the sequel to the Book of the Former Han Dynasty”.

The Hell scene in the text is described as “Go up to the hall, and see the golden chair of the Kowloon. Zhongxiang sits upright on the chair and is shouted to live long by ministers. Then eight people come to present 上殿,見九龍金椅。仲相上椅端坐,受其山呼萬歲畢,八人奏曰” (

Yu 1321–1323a). By contrast, in the image space, Sima Zhongxiang is on the right side of the illustration, sitting in the center with a flat crown, a dragon suit, a pair of worry-free shoes, a jade belt, and an oath sword. There is an official desk in front of him and a screen of the Emperor behind him. Eight attendants stand on the left and right, with long-winged hats and robes, holding Chaohu 朝笏. On the left side of the image, Hanxin and his servant kneel on the ground, with Pengyue, Yingbu, Han Gaozu, and Empress Lü standing on trial in turn (

Figure 6). The image space forms the social ranking of “superiority and inferiority”. The painters constructed the “hell scene” in Buddhism. The image writing of Hell has nothing to do with the images of the Buddhist underworld, such as cow ghosts, horse faces, and snake gods. It intends to highlight the form of Confucian power, such as the Emperor, the court, and Confucian scholars. The design logic aims to manifest Confucian political order. The construction of the religious schema of “superiority and inferiority” and the behavior of “abandoning gods” symbolize the infiltration of Confucian principles and ethics and manifest the prescriptive nature of the bottom people’s thinking about religious gods. The painting of the dream of the deification ceremony adopts the same strategy. “Yinjiao Dreamed About Gods Giving Him the Axe to Destroy Zhou” in the “

Book of King Wu Attacking Zhou” depicts the story of the prince, Yinjiao 殷郊. He fled from the imperial Zhaoge 朝歌 and arrived at a temple at night. He dreamed that “(gods) drank with him and gave him a big axe of a hundred jin, which was regarded as ‘the axe to defeat Zhou.’” (

Yu 1321–1323a). As shown in

Figure 7, the sleeping Yinjiao is on the right side of the illustration, and the ceremony of the gods granting the axe is painted on the left. The gods, attendants, and a table build the spatial hierarchy of the power field. The “divine axe” is granted by officials wearing long-winged hats and robes. The Taoist ritual space of “the immortals bestowing an axe on Yinjiao” was created independently from the text by the painters. The translation of the immortal images into the ritual scene of Confucian political order represents the public landscape of Confucian politics and religions. After “the prince told gods all his father’s unkind and immoral acts 太子具說父王不仁無道之事”, the gods gave him an axe to kill King Zhou, representing the image volition of the gods to change the designation of the imperial reign because King Zhou violated ethics and the Five Virtues and exhibiting the public’s recognition and acceptance of the Confucian ethics of benevolence, righteousness, and propriety. In these religious narrative images, including “King Zhou Dreamed About the Jade Maiden Giving Him The Jade Belt” and “King Wen Dreamed About the Flying Bear” in “the

Book of King Wu Attacking Zhou”, “Yingbu Shot King Han” in “the Sequel of the

Book of the Former Han Dynasty”, “Star Fell Down to Kongming’s Campsite” in “Records of the Three Kingdoms”, “the First Emperor of Qin Ordered Wangjian to Attack Zhao” in “Qin Merged Six Countries”, and so on, with the help of order symbols, such as the costume of the Emperor, the long-winged caps of the literary ministers, the armors and Confucian robes (round-neck robes) of the military generals, the screen of the Emperor, the plaque of the court, the trial table, and the deacon’s guard of honor, the painters of the fiction constructed the Confucian power field. The spatial form of Confucian political and religious ethics is shaped with the assistance of religious symbols, such as the immortals and Buddha fighting and the gods and demons helping the heresies, devils, ghosts, and Raksha. Therefore, the illustrations in “

Quanxiang Pinghua” are the conceptual expression of the painters based on Confucian political and religious order. Through the realistic imitation of the symbol rhetoric of texts and the images of Buddhism and Taoism, they make up for the incomplete concept of the deified images of the readers while depicting the order of superiority and inferiority in Confucian political and religious concepts.

In summary, the religious images in “Quanxiang Pinghua” present the public identification of the authors, painters, and engravers of popular literature and depict the space of Confucian political and religious order. The painters arranged the images in the fiction in a Confucian order of superiority and inferiority mainly by creating Buddhist and Taoist images. The construction of the symbols of the texts and images in the fiction reflects the influence of Confucian political and religious ethics on the spatial form of the religious images, highlighting the legitimate position of Confucianism in the visual aesthetic exploration of the illustrations in early Chinese fictions.

4. Religious Landscape: Public Construction and Moral Education of Rituals of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism

The narrative images of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism in “

Quanxiang Pinghua” shape religious ceremony activities, such as Dynasty sacrifice, prayer, repentance, resorting to magic arts, recitation of scriptures, and judgments of the gods and demons. E. Durkheim believed that “ritual is a component of all religions, just as essential as faith”. (

Durkheim and Zhou 2000, p. 84). Religious art historian Wallace also pointed out that “ritual is a fundamental component of religion. The basic category of religious behavior can only be found in the context of systematized before and after associations known as ‘ritual’”. Similarly, these rituals and related beliefs are components of a larger complex”. (

Wallace 1966, pp. 75–76). The complex of multiple rituals is defined by Wallace as a system of worship, and the blending of various forms of worship and beliefs forms a social religion. Religious rituals reflect the legitimacy and sanctity of institutions. Victor Turner pointed out that “religious rituals are beliefs in mysterious beings or powers, which are considered the primary and ultimate cause of all outcomes.” (

Fiona and Jin 2004, p. 176). Therefore, religious rituals can be seen as the public’s cognition and belief of the emergence of sacred beings and mysterious phenomena, as well as their worship behaviors based on it. The illustrations in “

Quanxiang Pinghua” construct the way for the public to observe religious ceremonies. The ritual landscape constructed by symbols of texts and images, such as the plots of deification and the images of deities and demons, is a manifestation of the bottom people’s acceptance of the compromised concepts of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. The religious ceremony images in “

Quanxiang Pinghua” portray the understanding of the religious ethics of the public through the shaping of the moral enlightenment concepts of the three religions.

The construction of religious ritual images in “

Quanxiang Pinghua” reflects the compromised moral enlightenment concepts of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism in Jianyang during the Yuan Dynasty. As we all know, there was a tripartite confrontation of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism in the Yuan Dynasty. The three fought and compromised with each other. The monks, Taoists, believers, and preaching methods had secularized characteristics (

Dai 2010, p. 75). According to the “

History of the Yuan Dynasty”, “officials below the ranks of commander and minister can take charge of monks, laymen, the military, and the people”. Monks could engage in politics and business as Confucian scholars. The masters and believers of mainstream Taoism in the Yuan Dynasty had the features of Confucian scholars, with the same distinctive characteristics of three-in-one and secularization. The True Unity Sect, which prevailed in the South, had doctrines in this world linked with secular moral norms, emphasizing the purpose of “serving relatives in advance, being honest and loyalty, and being the best person in the world”. (

Huang 1323, p. 36). The combination of the doctrines of Buddhism and Taoism with the Confucian principles of “benevolence and righteousness” and “loyalty and filial piety” generated the ethics and religious beliefs worshiped by the masses. This religious concept is reflected in the aspect of social law as great moral behaviors of “benevolence, righteousness, propriety, wisdom, and trustworthiness”. When reflecting on the level of cosmic order, it is the natural law of the “Five Virtues of Heaven and Earth”. The illustrations of the gods and devils trying cases and dynastic sacrifice in “

Quanxiang Pinghua” combine sacred power with ethics to highlight the rituals of belief in Jianyang society in the Yuan Dynasty. For example, in the “

Quanxiang Pinghua Records of the Three Kingdoms”, the ritual image of “Zhongxiang was Sent by Gods to be the Judge in the Nether World” depicts Sima Zhongxiang going down to the underworld to try injustices. As shown in

Figure 8, Sima Shi is on the right side of the picture, sitting on the ground in the attire of the Emperor, with eight gods standing on the left. The scene of the verdict ceremony is located in Hell. The gist of the picture combines god images with the ethical order of the human world using the pattern of Karmic repetition between the human world and Hell to promote the ethical concept of “destiny is impermanent” and the retribution of good and evil. The corresponding text in the fiction further interprets the relationship between Buddhism and social ethics in popular thinking. The conversation between the eight gods and Sima Zhongxiang in the illustration is as follows:

The people of Yao, Shun, Yu, and Tang worth rewards; the people of Jie and Zhou were executed. The people of a licentious monarch do evil. These are all the God’s will. 陛下道不得個隨佛上生, 隨佛者下生。 陛下看堯舜禹湯之民, 即合與賞;桀紂之民,即合誅殺。我王不曉其意, 無道之主有作孽之民, 皆是天公之意.

The content of the text carries distinct Buddhist preaching connotations. Buddhism’s upper life and lower life originate from the Maitreya Upper Life Sutra and Maitreya Lower Life Sutra, referring to the Buddhist concepts of “Maitreya’s Upper Life in Pure Land” and “Maitreya’s Lower Life to save mankind”, aiming to educate the secular world to have a clear understanding of nature, pay attention to moral cultivation, and ultimately, reach the realm of Mahayana. The editors compared Buddhist enlightenment with the benevolence and righteousness of Yao and Shun and the tyranny of Xiajie and Shangzhou, pointing out that the sacred power of Buddhism was linked with the order of the benevolence and righteousness of Confucianism and clarifying the belief of Caesaropapism in the just natural law and orderly good and evil. That is to say, the belief in respecting Buddha and the gods in the eyes of the secular world was combined with Confucian ethics principles, thus forming a widely recognized system of political ethics and belief education. The ceremony of the judgment in the illustrations of the fiction is established in the textual semantics of the reincarnation of natural law and the retribution of good and evil. Through the portrayal of Sima Zhongxiang’s Buddhist ceremony, it achieves the combination of the persuasion of being kind and establishing the virtues of Buddhism with political ethics order. For the “Caesaropapism” structure pointed out by Benjamin I. Schwartz, “There is a sacred space at the social apex. Those who control this position have transcendence power to change the society.” (

Ji and Song 2006, p. 25). Religious ritual activities, such as the judgments of the gods and devils and Dynasty sacrifice, are written by the symbols of images and texts to construct the interactive relationship between the underlying Confucian order and Buddhist enlightenment. With the help of transcendence power, the public aimed to pursue the interaction between the gods and humans and realize public order and good customs in social ethics.

The construction of Taoist rituals in the illustrations of the fiction also demonstrates the enlightenment concepts of loyalty, filial piety, benevolence, and righteousness. From the teachings and rituals of Taoism in the Yuan Dynasty, the Qi, Yin–Yang, Five-Element, and Eight Trigrams proposed by Taoism are social and ethical imitations of the physical compositions of the universe, and rituals are a way to connect the gods and humans into one. The prevalent rituals of Taoism in the Yuan Dynasty, Zhaijiao 斋醮 and Qirang 祈禳, contained various forms, such as offering sacrifices to ghosts, congratulating on birthdays, celebrating, greeting the Emperor, and praying. These rituals were widely accepted by society, from the court down to the people. They prayed for exorcism and blessing through these rituals. During the Song and Yuan Dynasties, with the acceleration of the secularization of Taoism, Taoist rituals for the communication between humans and the gods were adapted into the narrative theme of popular literature. Mark Meulenbeld believed that, after the Song Dynasty, these rituals became the materials for narrative fictions, and the same deities appeared in rituals and fictions (

Mark 2015, p. 224). “

Quanxiang Pinghua” contains a large number of illustrations of offering sacrifices to ghosts and praying. They preset the ethical theme of causality in previous lives and the retribution of good and evil with Taoist rituals. For example, for the “Picture of King Wen Praying” in the “

Book of Wu King Attacking Zhou”, the text in the fiction tells the story of King Wen of Zhou. After being imprisoned by Shang Zhou in Jiangli City, he divined daily: ”Every day, King Wen regarded the Eight Trigrams of Qian, Kan, Gen, Zhen, Xun, Li, Kun, and Dui as the main generals of immortals and the Taisui Gods of Liujia and Liuyi as deputy generals to calculate the Yin-Yang, Five-Element, and 28 star signs. Through the divination with the Eight Trigrams, he predicted future disasters and blessings (

Yu 1321–1323a) 長把乾、坎、艮、震、巽、離、坤、兌為神將大將軍,使六丁六甲力左右將軍,摘其中十幹五行,二十八宿定分,八卦爻象,逐年逐月逐日逐時,知吉凶主事”. Through the Taoist ceremony, Qirang, King Wen of Zhou foresaw human disasters and fortunes and auspicious and inauspicious fates, and then, he cared about people’s agricultural harvests, diseases, and injuries. Corresponding to the ceremony, gods bestowed the “heavenly phoenix of auspiciousness” to demonstrate King Wen of Zhou’s benevolence, righteousness, and love for the people. The illustration in the fiction focuses on the ceremony of “Worship of Phoenix 天鳳來儀”. In the image, King Wen of Zhou sits upright, holding a turtle shell in his left hand and a stone in his right hand. On the ground, there are talismans for Qirang (as shown in

Figure 9). “Phoenix” representing the divine will, stands beside King Wen of Zhou. The image construction of Taoist rituals reproduces the deified scene of the communication between Heaven and humans in textual symbols. In contrast, the image of “Tianfeng Laiyi” represents the theme of “destiny is impermanent” and the retribution of good and evil. On the one hand, the image depicts King Zhou’s tyranny of the people and his killing of loyal and upright persons, which violated the ethical virtue of “loyalty, filial piety, benevolence, and righteousness”. Therefore, the gods intended to change the Dynasty and choose King Wen of Zhou as the ruler, who was benevolent, righteous, and loving of the people. On the other hand, ritual landscapes demonstrate the public’s religious belief in mysterious forces. Regardless of who he is, the common people or the Emperor, his action should comply with the ethical principle of benevolence, filial piety, and kindness. Individuals or monarchs who violated ethical order would be condemned and punished by the gods. Similar images in the fiction, such as the “King Wen Met Lei Zhenzi” in the “

Book of Wu King Attacking Zhou”, the “Guigu Went Down the Mountain” in the “Yueyi Tried to Obtain Seven Countries”, and the “Liuwu Assassinated King Han” in “the Sequel of the

Book of the Former Han Dynasty”, demonstrate unadorned folk beliefs through Taoist rituals. These beliefs are integrated with Buddhist causality and Confucian benevolence and righteousness, with the apparent purpose of persuading the people to be kind. It is worth noting that, in the construction of Taoist ritual illustrations in “

Quanxiang Pinghua”, images of maids, servants, government officials, prisoners, soldiers, civilians, and young children are intensively woven into the illustrations by the painters, achieving the watching of religious ritual scenes by the bottom people (as shown in

Figure 9). The public’s watching composes the subjectivity of the illustrations. This has a visual exchange relationship with Taoist rhetorical symbols in the fiction and ultimately constructs religious beliefs and ethical colors in the eyes of secular viewers. The social ethics of benevolence, righteousness, and leading to goodness reflected in Taoist rituals in the fiction, as Zhaoguang Ge said, “are integrated with the idea of causal reincarnation in Buddhism and the ethical principles in Confucianism, highlighting the superstition of ghosts and gods and religious ethics in Taoism. With the characteristic of ‘good is rewarded with good, and evil is rewarded with evil’, they are penetrated into folk society.” (

Ge 1987, p. 251).

The preceding part discussed Buddhist and Taoist ritual landscapes in the illustrations of the fiction. The concepts of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism manifested in the images are not singular, but a reflection of the public’s acceptance of compromised religious ideas. In religious beliefs constructed by the masses, rituals are a behavioral pattern that manifests the moral education of benevolence and righteousness. They reflect the character of the bottom people’s religious thinking. The dissemination of the institutionalized religions of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism at the bottom of society has similarities with the core ideas of the folk religions in the Yuan Dynasty. Mingming Wang believed that “Chinese folk religions refer to the follows that are popular among the general public, especially farmers in China: (1) beliefs in gods, ancestors, and ghosts; (2) ancestral temples, annual sacrifices, and life cycle rituals; (3) ritual organizations of families and regional temples; (4) the symbolic system of world outlook and cosmology.” (

Wang 1997, p. 156). In the feudal society of China, with the patriarchal system as the core, the educational thinking of “fraternization”, “filial piety”, and “benevolence” formed by the compromise of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism has the same characteristics as the benevolence, righteousness, and propriety advocated by the gods, ancestral beliefs, and patriarchal orders in the folk religions. The ethical concepts, such as good and evil retribution, causality, and reincarnation, represented by the religious ritual images in “

Quanxiang Pinghua”, are symbols of the people’s belief in the gods, ancestors, and ghosts, as well as ethical educational thinking.

It can be seen that the religious ceremony illustrations in the Yuan Dynasty’s “

Quanxiang Pinghua” compromise the concepts of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism and reflect the theme of the enlightenment of benevolence and righteousness, loyalty and filial piety, and leading to goodness. With the help of religious scenes, such as retribution and good and evil karma, the rituals in the illustrations of the fiction construct moral concepts in the context of Caesaropapism. Daniel Stevenson believed that “in individual practice, these ritual programs are seen as indispensable supplements to observing behaviors and the mind. Their special logic presupposes the concepts of cause and effect in previous lives and good and evil karma, and their characteristics need to be described and processed to become an indispensable part of the training of practitioners”. The fiction’s illustrations are a portrayal of the folk religious concepts of leading to goodness, benevolence, righteousness, and filial piety in the Jianyang area during the Yuan Dynasty, reflecting the ethical enlightenment and belief standards of the public (

Daniel 1987, pp. 340–41).

5. Ethical Perspective: Compromise of Doctrines of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism and the Formation of Beliefs

E. Durkheim once proposed that “religions are a unified system comprised of beliefs and practices, connecting with sacred things. Religious practice is a clearly defined mandatory behavior, just like the practice of morality and law.” (

Durkheim and Zhou 2000, p. 84). As local institutionalized religions in China, Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism exhibit folk religious beliefs and moral practices in the illustrations of the fiction “

Quanxiang Pinghua”. Undoubtedly, the religious rituals depicted in the fiction’s illustrations contribute to promoting religious ideas. The specificity of religions is disseminated through the deification writing in the purpose of the illustrations, such as the divine will to change the Dynasty, the salvation of gods and demons, and the judgement in Hell. Therefore, why do the narratives of the texts and images of the fiction manifest the characteristics of religious compromise and moral enlightenment? This can be explained by the religious context and values of folk religious beliefs in the Jianyang area in the Yuan Dynasty.

During the Yuan Dynasty, Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism prevailed in the Jianyang region. They were dominated by Zhuxi’s Neo-Confucianism, Linji Sect, and Qingwei Sect, respectively. The three religions were prosperous. At that time, Jianning Prefecture governed seven counties and established a total of 21 Confucian academies, with an average of three in each county. There were 89 Taoist temples and 279 Buddhist temples, with averages of 12.71 and 39.86 per county, respectively (

Li 2018, pp. 60–78). According to the “

Jianyang County Annals” in Jiajing of the Ming Dynasty, there were 16 Confucian academies, 137 Buddhist temples, and 55 Taoist temples in Jianyang during the Yuan Dynasty. Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist institutions accounted for 76%, 49%, and 61% of Jianning Prefecture, respectively.

5 This implies that, during the Yuan Dynasty, Jianyang became an important area of religious activities in Jianning Prefecture and Fujian Province. In the context of the movements of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, the folk religion activities were complex, and the religious beliefs of the people contained multiple ethical factors. On the one hand, under the open-minded religious policy of the government in the Yuan Dynasty, the influences of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism were quite titanic. Among the masses centered around patriarchal and patriarchal systems, the ethical order of Confucianism occupied a central position. On the other hand, the institutionalized religions, Buddhism and Taoism in the Yuan Dynasty, controlled the behaviors of monks and Taoists through doctrines and ethics. However, they could not affect the social behaviors of the secular masses like Confucianism. In order to meet the needs of the public, the mainstream religions of the Yuan Dynasty not only drew lessons from the most-strategic essence of Confucian ethics, but also constantly compromised with it. The newly formed morality and ethics became the foundation of the order of the secular public’s social life.

The religious narrative illustrations in the fiction not only reflect the compromise of the religious concepts of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, but also constitute the regulation of social ethics order and moral education. First, at the level of Confucianism, the government adopted it as a national policy, “Moral conduct should be the priority in the selection of people, and the Confucian classics and skills should be the priority in the test of accomplishment” (

Song 1976, vol. 81, p. 2019). Building up the nation on Confucianism played a role in regulating and balancing local religions. Jianyang was the hometown of Zhuxi. According to the “

Jianyang County Annals”, “Zhuxi, Cai Yuanding, and other scholars of the Southern Song Dynasty advocated Neo-Confucianism. Jianyang became the town of morality and righteousness.” (

Feng 1549, p. 84). Zhuxi’s Neo-Confucianism was widely spread in Jianyang. A large number of Neo-Confucian books were published to promote Confucianism by local bookstores, including Yushi Qinyou Hall, Liushi Rixin Hall, and Yushi Wuben Hall. These books significantly affected the society of Jianyang. “Travelers of all directions have books of Jianyang version, from the Six Classics to Xunzhuan 訓傳.” (

Zhu 1997, p. 677). The Confucian ethics of “benevolence and righteousness”, “loyalty”, and “filial piety” reflected in the illustrations of “

Quanxiang Pinghua” are the core of Zhuxi’s Confucian enlightenment. The heart of Zhuxi’s proposal of “Yin-Yang the gas of Five-Element, and reconcile the principle of Five-Constancy” is that “For the god, it is gold, wood, water, fire, and earth. For the people, it is Li, containing etiquette, righteousness, benevolent, wisdom, and faith.” (

Zhu and Jin 2007, p. 24). He acknowledged the theory of Yin–Yang and Five-Element and raised it to the Confucian principle of human ethics. Zhu’s Neo-Confucian interpretation of Buddha and Taoism’s thoughts of the gods and demons became a trend in Jianyang’s secular society. “Conferring honors on husbands who value morality, wives who value chastity, and filial sons and grandsons to standardize folk customs and promote ethos. It will certainly implement the fine spirit and good moral integrity in society to alert and warn future generations” (

Chen 2001, vol. 6, p. 1148). In this context, the theme of “benevolence, righteousness, loyalty, and filial piety” repeatedly appears in the religious schemata of “

Quanxiang Pinghua”. Whether the imperial power, such as Emperors, dukes, generals, scholar-bureaucrats, or individuals, including rangers, thieves, travelers, and civilians, the Confucian core logic of “benevolence, righteousness, loyalty, and filial piety” formed the political and religious spatial order. Second, at the Buddhist level, the prevalent Linji Sect in Jianyang originated from the Chan Sect. The government of the Yuan Dynasty selected hundreds of temples to preach and serve Buddha. In the “Touchstone for Fu jian 閩中金石略”, “Other temples, nunneries, and halls receive money and fields, read the four major scriptures, ‘Huayan 華嚴’, and ‘Fahua 法華’, and ignite the Buddha’s eternal light.” (

Chen 1934, p. 122). Through the purport of the scriptures of the reincarnation of good and evil, “Huayan Jing”, “Fahua Jing”, and other scriptures preached by temple monks and believers promoted benevolence, righteousness, and good moral conduct. Buddhist Mi Liu said, “The Buddha establishes the religion based on five vehicles. For the human vehicle, one, not to kill; two, not to steal; three, not to be evil and lewd; four, not to speak falsely; five, not to drink; six, not to be talkative; seven, not to speak evil; eight, not to be jealous; nine, not to be angry; and ten, not to be persistent. Those who practice the ten virtues will be repaid with going to heaven.” (

Takakusu 1925, p. 781). These social acts of kindness summarized by Buddhists from classical teachings are the same as Confucian morality. Finally, at the level of Taoism, the Qingwei Sect, founded by Shunshen Huang from Jianyang in the Yuan Dynasty, blended the teachings of the Chan Sect’s “discovering one’s sincerity and nature” with the Confucian theory of “Li Qi 理氣” and had a significant impact on the people. The “Qingwei Zhai Law 清微齋法” pointed out that “the code of conduct of Taoism is actually the knowledge of Confucianism seeking knowledge from things. That is to say, Taoist behavior should be based on sincerity. If the heart is dishonest, one cannot understand physics, and if the mind is not sincere, one cannot communicate with the gods 道家之行持,即儒家格物之學也。蓋行持以正心誠意為主,心不正則不足以感物,意不誠則不足以通神.” (

Ren 1368, p. 781). The Qingwei Sect integrated Confucianism and Buddhism, promoted good and self-cultivation practices among the people, and conducted religious activities, such as applying incantation, exorcism, and transcendence for the dead, aiming to emphasize moral order and the norms of benevolence and righteousness. Shunshen Huang once said, “If one is accustomed to goodness, his heart will be vast and bright, matching with the merits of heaven. It is called white karma. If one is accustomed to evil, his heart will be blurred, despicable, and filthy like hell. It is regarded as black karma 若習於善則此心廣大光明,與天合德,是名白業;若習於惡則此心昏昧,慘塞同地卑污,是名黑業.” (

Ren 1368, p. 781). Encouraging people to be kind and emphasizing virtues are consistent with Confucian ethical norms. That is to say, although the institutionalized religions of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism have different doctrines, there is mutual convergence in terms of benevolence, righteousness, morality, and ethical order. Based on the Neo-Confucian concept of propriety, the bottom people drew inspiration from the practices of leading to goodness, benevolence, and righteousness of Buddhism and Taoism and ultimately formed folk complex religious beliefs.

From a religious perspective, “

Quanxiang Pinghua” in the Yuan Dynasty is a religious and cultural book in the Jianyang region. It blends the public’s moral and ethical beliefs in the three religions of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, such as leading to goodness and virtues. The symbols of images and texts in the fiction jointly exhibit the public’s criteria for social events. Hume pointed out that “among all the people who once believed in polytheism, the earliest religious ideas did not originate from meditation on the work of nature but from a concern for life events.” (

Hume 2003, p. 13). The illustrations of “

Quanxiang Pinghua” were produced in the Yuan Dynasty when the secularization of institutionalized religions of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism accelerated. The illustrations in the fiction are a visual representation of the evolution of religious history while demonstrating the public’s religious concepts about life, persons, and historical events. Focusing on Confucian political education and drawing on the ethical factors of goodness, righteousness, loyalty, and filial piety in Buddhism and Taoism, these concepts have complex ethical compositions and folk beliefs. The religious schemata in “

Quanxiang Pinghua”, including sacrifice, immortals, and matching magical powers, form a set of ideographic systems of “politics and religion with moral conducts”. Its compilation reflects the generation of religious beliefs among the people in Jianyang. The illustrations of the fiction depict a large number of immortals. Worshiped by the public, these gods had additive religious colors and a fixed pattern of being created. Yinjiao, Lei Zhenzi, Guanyu, Hanxin, Yingbu, and others were all deities demoted to the mortal world. The painters used graphic symbols to display the generation and evolution of religious gods from the public’s perspective. In the “

Book of King Wu Attacking Zhou”, the Taoist God, Taisui 太岁, descended to the world as the prince Yinjiao. “One day, Empress Jiang gave birth to a Prince. Because the mud god was defeated by the king, he was sent from Heaven and became Taisui”. Through depicting supernatural events, such as Yinjiao hitting Daji with a cup, obtaining the divine axe at the mountain-god temple, and beheading King Zhou and Daji, the illustrations in the fiction reflect the generation pattern of the beliefs in immortals among the bottom people, namely being born as a mortal, being loyal and filial piety, loving the people, suffering misfortunes, eliminating demons, and creating gods with beliefs. For example, the character of Taisui was shaped as an ordinary human by the painters. Moreover, Lei Zhenzi, originally belonging to the Taoist deity system, is described in the texts as having meat wings, a Thunder God’s mouth, and a black face, while in the illustrations, he is depicted as a warrior wearing armor(as shown in

Figure 10). The painters drew deities as mortals to highlight their human appearances. The characteristics of the deeds of Yinjiao, Lei Zhenzi, Guanyu, Hanxin, and others are loyalty, filial piety, benevolence, and righteousness, eliminating violence, and ensuring peace for the people. This image practice of de-divinization, such as the “Empress Lü Held a Memorial Ceremony for the King of Han” in the “Sequel to the

Book of the Former Han Dynasty”, the “Zhongxiang was Sent by Gods to be the Judge in the Nether World” in the “Pinghua of the Records of the Three Kingdoms”, and the “Enchanting Array” in the “Sequel to Yueyi Tried to Obtain the State of Qi”, not only imitates immortal images in “gods helping people out of doom”, “immortals giving presents”, and “gods and demons fighting with spells”, but also presents the rejection of image symbols towards immortals. Heidegger once put forward the mark of the progression of visual subjectivity, “metaphysical thinkers pursue truth. The progress in technology. Art enters the horizon of aesthetics and becomes the object of experience, and the behavior of ‘abandoning gods’”. Jianyang bookshops applied Confucian order to Taoist and Buddhist images with developed printing and engraving techniques, reflecting the practice of “abandoning gods” in the fiction’s deification narrative and marking the deconstruction and constraint of Confucian thoughts on the visual cultural field.

It should be noted that the immortals depicted in the fiction, including the Taisui Yinjiao, the Thunder God Lei Zhenzi, the Guansheng Emperor Guanyu, and the Hell Judge Sima Zhongxiang, play a leading role in the events of destiny, such as causal reincarnation and the retribution of good and evil. These characters reflect the ethical values of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. The stories of the gods in the images were passed down among the people during the Song and Yuan Dynasties, with a belief system of folk religions. On the one hand, the people set up temples for these gods to offer sacrifices, pray for blessing and harm-avoidance, and promote values and ethics. On the other hand, the masses had their own judgment on the value standards of religious beliefs. The value standard of the beliefs in immortals is recorded in the Annals of Jianyang County in the Yuan Dynasty. For example, the “Chen Lushi Temple” describes the construction of the immortal temple in the surname of Chen and the reason for worship. This belief standard is consistent with that in “Quanxiang Pinghua”.

According to the “

Annals of Jianyang County”, the immortal Chen An was once a county magistrate, always upright and outspoken. His three sons were known for their righteousness. During the Zhenguan period of the Tang Dynasty, he was killed due to slander. His body was abandoned in a stream, flowing for dozens of miles. At that time, a monk surnamed Fan led the people to establish an ancestral temple to worship him. In the Yuanfeng period of the Song Dynasty, he was named by the people as the Marquis of Weihui, and his three sons were all honored as the Marquis of Justice, the Marquis of Loyalty, and the Marquis of Relief. These gods repeatedly helped the people and were helpful to society. The people were grateful for their virtues and established ancestral temples to worship them. 舊志神姓陳諱岸,昔為邑錄事,以直方清粹稱,子三人俱以行義著。唐貞觀中被讒,父子三人同時遇害,棄屍於溪,沂流而上數十裏,時有範頭陀者率鄉人立廟以祀之。宋元豐中封威惠侯,……三子皆封侯,曰協義、曰協信、曰協濟。……神屢恩助國難,恩澤惠民,民懷其德,為之立廟,累之為王室 (

Feng 1549, p. 83).

Chen’s family was worshiped as immortals by the people of Jianyang because they had the virtues of benevolence, filial piety, loyalty, righteousness, protecting the country, and benefiting the people. According to the “

Jianyang County Annals-Sacrifice”, sacrificial ceremonies were used in national affairs and the people’s gratitude to the gods: “The gods taught the people etiquette, set an example of benevolence and righteousness for the people, protected the people, and drove out disasters 國之大事在祀,蓋所以崇報萃渙,懷柔百神也。其在祭,儀法祀於民者則祀之,以死勤事則祀之,以勞定國則祀之,能禦大災則祀之,能抵大患則祀之” (

Feng 1549, p. 82). In other words, the belief standards of the folk religions in Jianyang was that the individual deities must be represented in politics, religions, and etiquette and have exemplary functions of benevolence, righteousness, and morality in social life. They have model values in protecting the country, loving the people, advocating virtues, and enlightening customs. This is similar to the theme of “the destiny is impermanent”, the Confucian concept of the political and religious order, and the moral teachings of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism contained in the relationship between the images and texts of “

Quanxiang Pinghua”. The writing of folk religious beliefs in the fiction is a comprehensive manifestation of social etiquette, morality, and order, exhibited in specific events as loyalty to the monarch, loving the people as children, filial piety to elders, and resistance to disasters. Once deities violate the value standards, they will be criticized by the public’s ethics. If the gods protect the people, they will be enshrined. Otherwise, they will be destroyed.

From this, it can be seen that the deep ethics reflected in the relationship between the images and texts in “Quanxiang Pinghua” are the value system of folk religious beliefs in Jianyang. This has the utilitarian characteristics of Confucianism and is linked to the ethical teachings formed by Taoism and Buddhism, such as benevolence, filial piety, loyalty, and loving the people.