Abstract

The monastic archives of Iceland have rarely been made the subject of specific studies. This article is intended to survey the history of one such archive, belonging to the Benedictine Abbey of Þingeyrar in Northern Iceland, which was founded 1133 and dissolved 1551. Through its extraordinarily rich literary production this monastery left an indelible mark on the Northern-European cultural heritage. After the Reformation Þingeyrar Cloister remained a state-owned and ecclesiastical institution until modern times. Its archive, which is partly preserved to this day, is both the most extensive of its kind to survive in Iceland and uniquely remained in place for almost eight centuries, making it possibly the longest operated archive in the Nordic countries. The Icelanders may be better known for their sagas and mythological poetry, but their industrious literacy certainly extended to creating bureaucratic documents in accordance with the Roman tradition. French Benedictines were among the first in the world to turn the art of archival management into an academic discipline, and the Icelandic Professor Árni Magnússon (d. 1730), who is best known for his great collection of Old Icelandic manuscripts, was the first Nordic scholar to employ their methods effectively, which he used to investigate the Archive of Þingeyrar. Surveying the history of this Icelandic archive gives us insight into a constitutive science fundamental for our access to the past.

1. The Long Life of Þingeyrar Abbey and Cloister

The Benedictine Abbey at Þingeyrar, located by Húnaflói in Northern Iceland, was established in 1133, according to Icelandic annals (Storm 1888, p. 113). Although not the first monastic foundation on the island, it became the first permanent one. It had a supremely literate population, even according to Icelandic standards. When dissolved as late as 1551, during the Reformation in Iceland (Kristjánsdóttir 2021), the Abbey had been in operation for 418 years, and would through its extraordinarily rich literary production leave an indelible mark on Northern-European cultural heritage (Jensson 2021c). But even after Þingeyrar Abbey was dissolved in the middle of the 16th century, its successor institution, still referred to as Þingeyrar Cloister, was operated for another 261 years as a crown ecclesiastical and agricultural estate. In fact, if we leave aside the change in Christian denomination, Þingeyrar Abbey and Cloister existed as a religious or quasi-religious public institution for almost seven centuries. Finally, when the Danish Crown was much in need for ready funds after finding itself on the losing side in the Napoleonic Wars, the farm of Þingeyrar was sold to the resident steward in 1812. However, even then the new private owner of Þingeyrar Cloister continued to manage the unsold monastic lands, which after 1848 were transferred from crown to state ownership, as Denmark liberated itself from absolutism. As an agricultural conglomerate of 60–70 farms under central administration, Þingeyrar Cloister lasted until the late 19th to early 20th century, when its farms were gradually sold off. Today, almost nine centuries after the foundation of Þingeyrar Abbey, one of these farms, Saurbær, is still owned by the Icelandic state, while another, Steinnes, belongs to the National Church. These holdings are leftovers of the medieval institutional structure.

Other remnants from monastic and early modern times are the dozens of parchment charters and great many paper documents from Þingeyrar Abbey and Cloister preserved at the National Archives of Iceland (Þorkelsson 1910, pp. 311–14; Karlsson 1963a, 1963b). Exceptionally, most of these charters survived the centralization of manuscripts and ecclesiastical archives in Copenhagen during the 17th and 18th century. The Þingeyrar Archive even escaped the manuscript and document collection of Professor Árni Magnússon (d. 1730) of the University of Copenhagen, who was only allowed to borrow 44 of the oldest charters at Þingeyrar in 1703 to study them and have precise transcripts made. Without these transcripts we would not have known those of the charters that have perished since. Árni Magnússon returned the documents in 1712, and the archive was still at Þingeyrar during the late 18th century, as is evidenced by three unpublished inventories from this time (see Figure 1 and Figure 2, and Appendix A). Most anomalously for Icelandic parchment documents, these charters were never transferred to Copenhagen, but were delivered directly to the National Archives of Iceland at the turn of the 20th century.

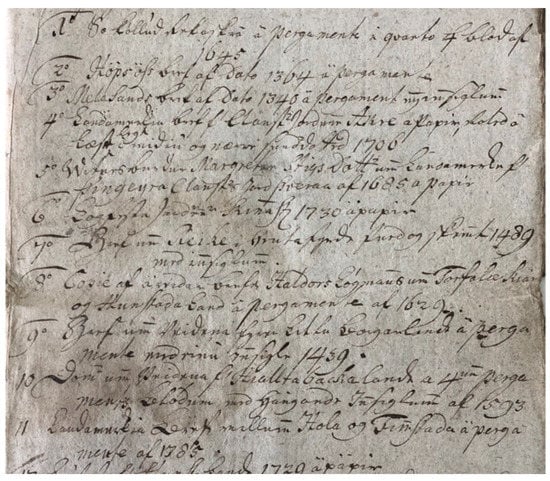

Figure 1.

Detail of leaf 9r in the appraisal of Þingeyrar 1773.

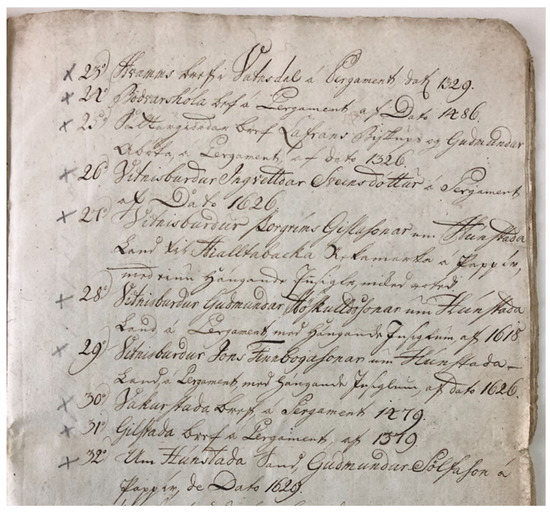

Figure 2.

Detail of leaf 8r in the appraisal of Þingeyrar 1783.

So rare is the history of these documents among Icelandic manuscripts that they were published in Diplomatarium Islandicum, the first volume of which came out in 1856–1876, while still at Þingeyrar, based on the transcripts made of them by Professor Árni Magnússon in 1703–1712. Remarkably, the Old Norse scholar Stefán Karlsson was unaware of their existence, until he was nearly finished preparing his important paleographical study and edition of original Icelandic charters from before 1450. When they were discovered, the main text of the edition was already set in led type, so that a special appendix had to be created at the end of the book for the new originals from Þingeyrar. Ironically, on that occasion they were sent to Copenhagen for the first time to be facsimilized, where Karlsson was working on his edition (Karlsson 1963a, p. XLII; 1963b, Preface).

2. The French Benedictine Diplomatics of Professor Árni Magnússon

After the Reformation and the concomittant appropriation of monastic properties in Iceland by the Danish-Norwegian Crown, an attempt was made by officials in Denmark to centralize Icelandic archives in Copenhagen and/or at Bessastaðir, the governor‘s residence in the south-west of Iceland (see Figure 3). Letters were issued requesting cartularies and original charters be handed over to the authorites (Laursen 1900, p. 353, letter dated 12 May 1578). The purpose was to document land ownership and other rights formerly belonging to the monasteries, which had now become crown property. Over a century later, during 1702–1712, Professor Árni Magnússon, who was responsible for the Royal Archives in Copenhagen, was in Iceland as royal commissioner, together with Lawman Páll Jónsson Vídalín (d. 1727), to document the land holdings, livestock, and population of Iceland, amongst other tasks. While there he collected the originals and copies of early Icelandic charters, which had been delivered to Bessastaðir, 121 items in all, although none of them were from Þingeyrar Cloister. He was able to track down a handful of Þingeyrar charters from other sources, documents that had strayed from Þingeyrar with officials, who had been stationed there at some point, such as Þórður Þorleifsson steward of Kirkjubæjarklaustur (d. 1738), from whom he received some charters, but he was still missing most of the originals from the Þingeyrar Archive.

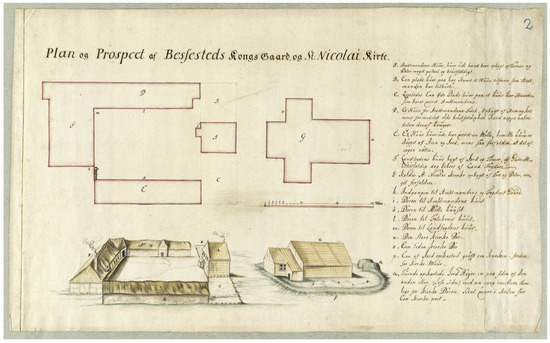

Figure 3.

Ground plan and perspective drawing of Bessastaðir 1720. The National Archives of Iceland.

Árni Magnússon was an expert historian, and his interest in medieval archives was exceptionally well informed for his time. In the years 1694–1696, before taking office as professor at the University of Copenhagen, he had travelled widely on the European continent. In Germany in particular, he excerpted church historical and other data from manuscripts and printed books. His large collection of notes in 18 volumes is preserved in Copenhagen, The Arnamagnæan Collection, AM 909 A-E, 4to (Rafnsson 1987; Halldórsson 1998). He showed particular interest in the work of the Maurists in Paris, Benedictine monks and scholars, the most famous of whom is Jean Mabillon (d. 1707), credited with developing a scientific method for the investigation of historical documents (Delumeau 2007). The discipline of diplomatics was originally developed to determine the authenticity of charters and diplomas issued by royal and papal chanceries. Subsequently, scholars realised that the tools and methods of diplomatics could be used in the study of historical documents in general, indeed also in forensics and to determine the provenance of digital or electronic documents. Although palaeography is important for diplomatics, it is only one of the many techniques used. As a whole the discipline has more in common with textual and historical criticism (Duranti 1989, p. 12). Diplomatics soon became an important auxiliary science to history, and in the 18th and 19th centuries, when history began to shed its ancient rhetorical origins and developed into the ruling academic discipline in European universities, its new and strict demand for documentation was much in the spirit of the French Benedictines.

Árni Magnússon seems to have become acquainted with the work of Mabillon, primarily his De re diplomatica libri sex (Paris 1681), when assisting the royal Danish antiquarian Thomas Bartholin jr. (d. 1690). Later he refers to Mabillon in his introduction to the Zealand Chronicle, which he published in Leipzig 1695 (Jensson 2021a, p. 92). Just as the Maurists, Árni Magnússson did not limit himself to transcribing original charters verbatim (orðrétt), he transcribed to-the-letter (stafrétt), period-correct (punktrétt), and stroke-correct (strikrétt). The transcriptions he made of medieval charters attempt to imitate the originals in all significant features, without however being drawings, such as for instance the copperplate facsimiles used to represent scribal hands in Old Icelandic editions from the late 18th century until the arrival of photographic facsimiles after the middle of the 19th century (Jensson 2021a, pp. 97–106; 2021b, pp. 196–200). Árni Magnússon also collected and investigated the seals attached to medieval and early modern letters, and had his assistant draw them up for reference. In Reykjavík, Stofun Árna Magnússonar, AM 217 8vo, a number of seals from Þingeyrar Abbey and other archives are drawn up, described, and reconstructed, if flawed or broken (Lárusson and Kristjánsson 1965–1967). For this study, he had access to letters carrying Þingeyrar seals at Þingeyrar Cloister, as is show by notations of the type: “This letter lies at Þingeyrar among the letters of the Cloister” (liggur þetta bref ä þingeyrum medal klaustursens brefa).

Árni Magnússon felt little need for distinguishing between the investigation of letters for the purpose of deciding whether they were authentic or counterfeit from a legal perspective, and the study of charters to harvest historical information from them. During his stay in Iceland as royal commissioner, he primarily resided in Skálholt with Bishop Jón Vídalín (d. 1720) (see Figure 4). One of the young men studying at the Cathedral School, Páll Hákonarson (d. 1742), who had a fine hand and a talent for drawing, received basic training in diplomatics from Árni Magnússon and became his assistant in transcribing and investigating charters. Occasionally, after transcribing and analyzing a charter, they would sign the transcription and put their seals under its analysis, which shows that they understood their engagement with the documents not just as historical research but also as archival inspection. Indeed, this work resulted in Árni Magnússon exposing a few counterfeits among the parchment charters he collected in Iceland.

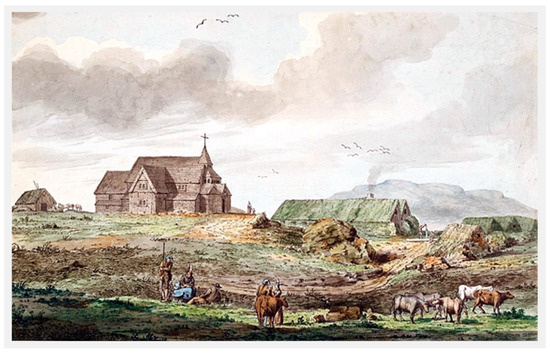

Figure 4.

The Cathedral and other buildings at Skálholt in 1772. Painting by John Clevely Jr.

The winter following his arrival in Iceland, Árni Magnússon arranged for his associate Lawman Páll Jónsson Vídalín to visit Þingeyrar Cloister to claim the oldest documents in its archive. This is shown by a receipt Páll Jónsson issued on 24 February 1703 to Lawman Lauritz Gottrup, steward of Þingeyrar Cloister (in office 1685–1721), for 44 charters, all but two on parchment, besides four paper slips. Lawman Vídalín promises that the documents will be returned in good condition but doesn’t say when. On 23 May 1703, Árni Magnússon acknowledges receiving these charters from Lawman Vídalín. As the years went on, Lawman Gottrup began to send him reminders to return the charters to Þingeyrar. The two men seem to have had little liking for each other, and since Árni Magnússon was known for his insatiable appetite for parchment documents, Gottrup’s insistance was not unwarranted. In a reply to Gottrup, dated 6 February 1711, Árni Magnússon promises to return the charters in the summer, during the General Assembly (alþingi) at Þingvellir (literally: Assembly Plains), though he doesn’t say what year. A year later, 13 August 1712, after the Assembly and just before sailing back to Denmark, he charged Lawman Vídalín with delivering the charters to Þingeyrar Cloister, as we gather from a receipt issued him by the lawman. These transactions are found in AM Dipl. Isl. Apogr. 500 with a draft of Árni Magnússon’s incomplete study of the abbots of Þingeyrar, which was one of the products of his investigation. The transactions are stored with the Cloister Archive transcriptions, the over-all call number series of which is Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar, AM Dipl. Isl. Apogr. 438–510. All these papers were transported to Copenhagen with the manuscripts and fragments Árni Magnússon collected in Iceland during the years 1702–1712, both in his capacity as royal archivist and private collector. After his death, his great collection, traditionally referred to as The Arnamagnæan Collection, remained in Denmark for centuries, until some parts of it, including these Þingeyrar papers, although by no means all the manuscripts originating from the Abbey, were returned to Iceland in the repatriations of 1904, 1928, and 1971–1997.

3. The Church of Þingeyrar Abbey and Cloister

The Archive of Þingeyrar provides valuable information on the material form of the Abbey and Cloister. Two unusually precise appreciations exist of the buildings there, one from 1684, when Lawman Lauritz Gottrup took up residence, and the other from 1704, made by Gottrup‘s men at the request of Lawman Vídalín and Professor Árni Magnússon as part of the registration of farms and farmland in Iceland (Jensson 2022, pp. 292–95). According to the latter, most of the buldings at Þingeyrar apparently stood to the south of the old church, surrounding a paved square, sometimes referred to as the Cloister Farm. The modern farm seems to be built on the same ground. This building complex south of the church consisted of almost 50 houses and huts of wood, stone, and turf, and was inhabited by a household of just under 40 people, according to the Icelandic Census of 1703, which is another accomplishment of the royal commission of Árni Magnússon and Páll Vídalín. Separate documents describe and appreciate the farmhouses on the monastic lands in the neighboring countryside. The immutability of living conditions in Iceland (the general population of Iceland is believed to have been comparatively stable in the period from 900 to 1900, at about 40.000 to 60.000 inhabitants) would seem to indicate that conditions at Þingeyrar at the beginning of the 18th century may not have been much different from those in the medieval Abbey. In any case, some of the houses constructed at Þingeyrar Abbey were still in use during the subsequent Cloister period, although they were no doubt often repaired and renovated with driftwood and/or imported timber from Scandinavia. According to the charters of the archive, Þingeyrar Abbey and Cloister had exclusive rights to much of the driftwood on the neighboring beaches, while the appraisal of 1684 reveals quantities of wood stored up on the premises.

In 1684 the oldest building at Þingeyrar was no doubt the church. The story of its foundation is told in the Saga of St. Jón of Hólar (d. 1121), originally composed in Latin shortly after 1200 by a member of the Þingeyrar community, Brother Gunnlaugur Leifsson (d. 1218/19): “the holy Bishop Jón took off his cloak and himself marked the foundation for the church“ (Cormack 2021, p. 47). The monks themselves thus remembered the foundation seventy years after. Based on Árni Magnússon’s transcription of one of the charters in the archive at Þingeyrar, the original of which is now lost, two Benedictine abbots, an Icelander and a Norwegian, also testified to the role of the priest Þorkell the Stick (trandill) (d. ca. 1117), minister at Þingeyrar, in preparing for the foundation. The charter is dated at Trondheim, Norway, 20 May 1320 (DI II 1893, no. 341). When the appraisals of 1684 and 1704 are read in the light of more charters, medieval annalistic entries, and the saga of Bishop Lárentius (d. 1331) (Grímsdóttir 1998), sources that provide additional information on its history, it seems probable that the monastic church survived for 562 years, albeit with renovations, reckoned from the year of the Abbey’s foundation, 1133, until it was torn down by the steward Lauritz Gottrup in 1695 (Jensson 2022, p. 278). This enterprising Danish steward had a new church constructed, largely from imported timber, as is detailed in the appraisal of 1704. It was a considerably simpler construction, and shorter by four meters compared to the monastic church (Jensson 2022, p. 279).

The monastic church was a large wooden stave church with a ground plan of approximately 20 × 10 m. The early modern annals claim that unspecified carpentry work was carried out on the church in 1619, when Páll Guðbrandsson (d. 1621) was steward. This was done in accordance with the king’s general wishes that the size of monastic churches be reduced. However, the king’s orders were not to use new timber, instead the wood from the old churches was to be reused. The continued excessive size of Þingeyrar church for a parish church, even after the renovations of 1619, argues against any major reduction in its measurements. More likely, the west end of the church with its narthex and bell tower(s) was removed in 1619, as is shown by the many displaced bells of the 1684 appraisal (Jensson 2022, pp. 273–74). The west end had probably been redesigned in the early 14th century, when the nave was rebuilt, according to medieval annals, making it necessary for the bishop of the diocese to reconsecrate the church in 1314. But the core of the church, the choir and the inner choir, most likely dated back to the early 12th century. The bell towers on the west façade are possibly depicted schematically on medieval seals from Þingeyrar Abbey that Árni Magnússon had drawn up for his study of seals in AM 217 8vo (see Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

The seal of the Convent Brothers at Þingeyrar, used 1424, 1489, and 1548.

Figure 6.

The seal of Abbot Gunnsteinn of Þingeyrar, used 1363 and 1373.

After the reconstruction, the church was still larger than any built since, including the present stone church. As to the timber, Árni Magnússon confirms in his draft study on the abbots of Þingeyrar, mentioned above, that the staves (stólpar) and some other timber of the monastic church could still be seen at Þingeyrar in his own day (AM Dipl. Isl. Apogr. 505: “whose staves and other timber are still visible there” [hvorrar stopla & annan vid ma þar enn sia]). Considering that he wrote this at the beginning of the 18th century, Árni Magnússon must have been referring to wood from the church described in the appraisal of 1684. As detailed in the appraisal of Lawman Gottrup’s new church in 1704 (built 1695), a few staves, studs, beams, and rafters from the old church were reused, and this wood is claimed to be even better and more durable than the imported Gotland timber used, “because of its choice quality as wood and hardening” (sökum viðarvals og herslu), evidently with reference to its great age (Jensson 2022, p. 320).

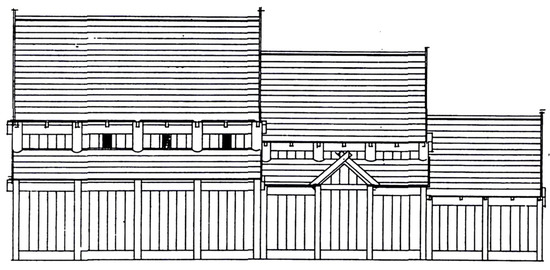

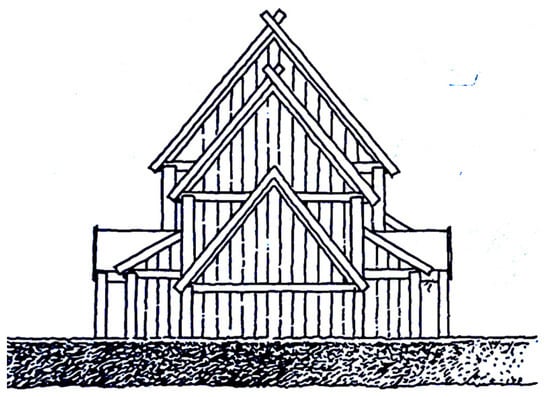

The late artist and scholar Hörður Ágústsson (d. 2005) has made some reconstructive sketches of the church described in the appreciation of 1684 (see Figure 7 and Figure 8; cf. Ágústsson 1972, 1990, 1989). The height of its ridge, according to the appraisal of 1684, was about 8 meters (the measurements are given in ells). The medieval nave with its side aisles, the choir with its side aisles and transepts, and the inner choir, where the high altar was located, these were likely still more or less intact in 1684. The construction of this church was carried by 42 staves in 4 rows, the height of its tallest staves five meters, while the shortest staves of the choir were probably only half of that. On top of the rows of staves rested the complicated roof structure, which originally must have had about 20 different surfaces, at least until the west end with its narthex and bell tower(s) was supposedly removed in 1619. The floor of the church was covered with wooden boards to the high altar. Similar stave churches are preserved in Norway to this day.

Figure 7.

Þingeyrar Church 1684, seen from the south. Drawing by Hörður Ágústsson.

Figure 8.

Þingeyrar Church 1684, from east. Drawing by Hörður Ágústsson.

The 1684 appraisal includes a description of a balcony inside the church with three vaulted ceilings underneath, called pulpitu(m). Such balconies in medieval churches served to divide the church between nave and choir, which were the spaces allotted to laymen and clergy respectively. A pulpitum also functioned as a pulpit, modern pulpits first appearing in Icelandic churches after the Reformation (Harðardóttir 2017, pp. 198–99). In each transept, there were two outer altars (útaltari), on the south side the altars of St. Benedict and St. Olaf, while in the north transept the Holy Cross was worshipped, which on the authority of a medieval annal bled miraculously from the foot in 1273 (Storm 1888, p. 331; Hagen 2021, pp. 114–15). The Virgin Mary likely also had an altar in the north transept, there being three effigies of her inside the church, two made of alabaster, according to Sigurðarregistur, which is our sole source of information about the items found inside the monastic church. According to this inventory, there were 20 effigies of saints and other holy persons among the artefacts in the church. The inner choir (ca. 4 × 4 m) in the east end of the church was elevated by a platform two steps higher than the rest of the wooden floor. There the high altar was located, the holy of holies, and by its walls, presumably in chests, was the archive and library of Þingeyrar Abbey (DI IX 1906–1913, no. 266–278 [pp. 312–16]; Jensson 2022, pp. 286–88).

The description of the library is less detailed than we would have liked. About forty Latin titles are listed, besides eleven Old Icelandic ones, the latter predominantly hagiographical texts translated from Latin (Jensson 2017; 2022, pp. 287–88). Most of the manuscripts must have been produced by the brothers themselves, who were no doubt also responsible for some of the Old Icelandic translations. However, in addition to books provided with titles, a blank reference is made to tantalizingly “many Latin books at the high altar, in good and bad condition” (J háalttari margar látinubækr godar og illar), while at the end of the list of Old Icelandic titles, we get another blank reference to an unspecified but more limited number of books: “additionally, occasional other books, rotten and old” (þar til hinar og adrar skrædur rottnar og gamlar), presumably these, too, in Old Icelandic. Immediately after the books, “six chests” (kistur .vj.) are inventoried, seemingly also placed by the high altar. Considering the order in which things are listed, although this is not always a reliable indicator, some of these chests were almost certainly book chests (Jensson 2022, p. 287).

What are we to make of the blank references to books in the library at Þingeyrar? To begin with, we need a proper context for this information. How many books were there in the other monastic libraries in Iceland? We can use the same inventory, Sigurðarregistur from 1525, to approximate the number of books in the other monastic libraries of the northern diocese of Iceland, Hólar. This data does not lend itself to presentation in table format, because of the inconsistency in the inventoried categories, and the lack of number for listed books, which the reader himself must count. But with these reservations, we can say approximately, that the Benedictine monastery at Munkaþverá, which was closely associated with Þingeyrar, had 66 Latin volumes, mostly liturgical texts, and 14 hagiographical books with translated sagas in Old Icelandic (DI IX 1906–1913, no. 266–278 [pp. 305–12]). The Benedictine convent at Reynistaður owned 30 Latin liturgical volumes, and an additional 12 with hagiography and Scripture in Old Icelandic (DI IX 1906–1913, no. 266–278 [pp. 320–22]). The Augustinian priory at Möðruvellir lists 71 books, apparently all in Latin (DI IX 1906–1913, no. 266–278 [pp. 316–20]). As for the southern diocese, we may for comparison use the inventories of Vilchinsmáldagi from 1397 (DI IV 1897, no. 17–300). According to it, the Benedictine convent at Kirkjubær in the south of Iceland had 59 books, approximately, including liturgical books, and most of them in Latin (DI IV 1897, no. 17–300 [p. 238]). Another Augustinian canonry, located on the island of Viðey, just outside the modern capital of Reykjavík, had a library consisting of 62 Latin books and 13 Old Icelandic ones (DI IV 1897, no. 17–300 [pp. 110–11]). The Augustinian monastery at Helgafell, in the west of Iceland, owned “close to 120 Latin books, the rest are books of hours” (nærre hvndrade latinvboka. annad eru tijdabækur), in addition to “thirty-five volumes in Old Icelandic” (halfur fiordi tugur norrænvboka). Even before this information is given, about 20 liturgical books have been listed in the inventory (DI IV 1897, no. 17–300 [pp. 165–72]). Vilchinsmáldagi does not, unfortunately, provide information about the early and presumably large Augustinian house of Þykkvibær in the south of Iceland.

If we review the description of Þingeyrar Abbey’s books in Sigurðarregistur in the light of this context, the only comparative library among the ones listed above seems to be that of Helgafell Abbey. There, too, the inventories provide a rough estimate: close to a (large) hundred (120) Latin books (nærri hvndrade latinvboka). The number is suspiciously rounded, and no titles are provided for these books, unless the 20 Latin liturgical books already given titles in the inventory are assumed to be part of these “almost a [large] hundred” books. Indeed, this number for the Helgafell Latin library may not have resulted from independent counting by the registrants of Vilchinsmáldagi, because we also find it in the Helgafell inventory from two centuries earlier (“a hundred books” [hundraþ bækr]; DI II 1587–1876, no. 69). The reason must be that the books of both libraries, Helgafell and Þingeyrar, were so many that it appeared too much of an effort for the registrants to count them, let alone to provide them with titles or content descriptions. Hence, the unknown blank references of “many Latin books” and “occasional other books” at Þingeyrar Abbey likely point to a larger number than the just over 50 books that are provided with titles in the inventory. Thus, there may have been a total number of books at Þingeyrar Abbey well above one hundred, that is, over 80 books in Latin, and over 20 in Old Icelandic. All these books were evidently stored in the six chests mentioned, but out of the six, one no doubt contained the archive (see below), and two or three likely textiles, which leaves two or three for books. To conclude, although we ultimately cannot know the exact number of books in the library at Þingeyrar, we can on reasonable grounds assume that (1) they were considerably more than one hundred, (2) most of them were in Latin, and (3) the library was perceived as being exceptionally large for its kind in Iceland (far beyond registering precisely).

Scraps from the library of Þingeyrar are accidentally preserved among the items of the archive, providing additional information about titles that were once found in its (two or three) book chests. In AM 279 a 4to, the so-called Book of Þingeyrar (Þingeyrabók), which contains instructions on how to divide driftwood and beached whales on the coasts to which the Abbey had rights, are found scraps of Rufinus‘ 4th-century Latin translation of the Greek Historia Ecclesiastica of Eusebius of Caesarea (d. 339). The Icelandic text is on the back of a leaf of the Latin Eusebius, originally an extensive text, which was evidently found in the church library. Likewise, AM Dipl. Isl. Fasc. V,12 (DI III 1896, no. 505), dated 2 Juli 1395, contains the charter of the Church of Our Lady at Höskuldsstaðir, not far from Þingeyrar Abbey. It is written by the local priest Þórður Þórðarsson (Karlsson 1963a, pp. LV-LVI) on the verso side of a leaf removed from a Roman Gradual from Þingeyrar Abbey. We know the provenance of the Gradual, because the Latin text is by the same hand as AM 595 a-b 4to (1325–1350), a manuscript preserving the older version of Rómverja saga (Helgadóttir 2010, p. xxx). This Icelandic saga is a translation of the Bellum Jugurthinum and Coniuratio Catilinae of the Roman historian Sallust (d. 34 BC) together with a prose paraphrase of the epic poem Pharsalia by Lucan (d. 65). AM 595 a-b 4to and the translation it contains are known to originate from Þingeyrar, and thus the Roman Gradual, together with copies of these Roman authors in both Latin and the vernacular, were evidently also found in the library of Þingeyrar Abbey.

Why were the library and archive of Þingeyrar Abbey and Cloister kept at the high altar? The answer to this question has to do with the magnetic pull of sacred locations. The high altar was the sanctum sanctorum, the holiest place in the church, and it was customary to store books and documents belonging to churches close to the altar (Þórólfsson 1953; Gunnlaugsson 2016). Indeed, everything of importance seems to have been kept close to the altar. At Þingeyrar Abbey, it was no doubt highly significant that Saint Jón of Hólar laid down his cloak, where the church of Þingeyrar was later built. The church was a place of great sanctity, and laymen would pay a considerable sum of money just to be buried in the floor of the bell tower, in the east end, the laymen’s end of the church, which was its least holy part. For this, and for having his and his wife Borghildur’s names included in the prayers and masses sung by the monks, the prudent farmer Benedikt Kolbeinsson made a large donation to Þingeyrar Abbey in his testament of 22 February 1363 (DI III 1896, no. 155).

Even in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Lutheran stewards of Þingeyrar Cloister had their graves located as close to the altar as possible. This is what Lawman Lauritz Gottrup did, when he had his mother buried at the altar of the still standing monastic church (Þorsteinsson 1922–1927, p. 405), and later himself with the rest of his family in the new church he built (Þorsteinsson 1922–1927, p. 518). Recent archeological excavation by archeologist Steinunn Kristjánsdóttir and her team have unearthed the graves of the stewards Jón Þorleifsson (d. 1682), Bjarni Halldórsson (d. 1773), and Oddur Stefánsson (d. 1803), close together in what is believed to be the west end of the church. The successive churches seem to have had their altars in the exact same spot. The idea that the proper location of a library was inside a church continued long into the 19th century in Iceland. The Old Icelandic scholar Guðbrandur Vigfússon (d. 1889), who lived at Oxford from 1866 to the end of his life, as a young man received financial aid from the builder of the present stone church, Ásgeir Einarsson (d. 1885). In return, he later contributed to a new bell for the church, and left his large private library to Christ Church in Oxford, and to the church at Þingeyrar, as the Icelandic professor Sigurður Nordal (d. 1974) recalls in an article published in the local journal Húnavaka (Nordal 1970).

4. The Archive of Þingeyrar

Although books in Icelandic churches were usually kept in chests, occasionally in late medieval cathedrals there would be armaria or bookcases (Wallem 1910). Archives, however, seem always to have been stored in chests (Þórólfsson 1953). Árni Magnússon refers, for instance, in his notes to the “region’s chest” (amtkista) at Bessastaðir, when he speaks of the archive there (Mósesdóttir 1996, p. 235). The archive of the Augustinian Abbey on the Island of Viðey, Viðeyjarklaustur, which was mentioned above, was stored in a locked chest of the same kind as that containing the textiles of the monastery: “The textiles and letters of Viðeyjarklaustur lie in two chests and Brother Peter has the key to them” (Kyerckenns klædir oc breff tiill Huidó clostir ligger ij ij kiister. Oc haffuir brodir Pedir nógelin tiill dennom). Within this chest, the charters were stored in two bags that could be sealed: “In one of these chests lie two bags with the letters of the monastery, which I Poul Huitfeldt have sealed” (Ij then eene kiiste ligger ij poeser mett klostirs breff huilche poser jegh Poffuell Huittfeldt haffuir besegliidt) (Mósesdóttir 1996, p. 222). The document just cited was made in 1553 for the Danish Governor of Norway, Poul Hvitfelt (d. 1592), and the named Brother Peter, entrusted with the key to the archival chest, was no doubt one of the monks from the monastery. The original charters referred to here are lost, but their contents are preserved in the first third (leaves 3–30v) of a copybook named after the Danish governor’s residence in Iceland, at Bessastaðir: Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar, AM 238 4to (Bessastaðabók). In this cartulary, we find 38 charters related to Viðeyjarklaustur, all of them having to do with landed property and rights, which was the main concern of royal officials.

We also know that charters were stored in this way in Norway, based on a Danish inventory of 1622, the Akershus Registry (Tank 1916). It contains a description of four archives from Norwegian Abbeys and Convents, the largest of which came from the Cistercian monastery of Hovedøya Island, just off the modern capital of Oslo. These archives were stored in six chests that were brought to the castle of Akershus in Oslo, the seat of the royal governor, after the dissolution of these religious houses around the time of the Reformation. The Akershus Registry is detailed in that it attempts a full description of the archives and gives plentiful information about them, which is fortunate, because the charters themselves are now lost, after being allegedly destroyed by a mad Danish nobleman in the late 18th century (Jensson et al. 2018, pp. 40–41). For instance, it is noted that these documents, like the ones from Viðeyjarklaustur in Iceland, were wrapped up in fabric that was sealable, perhaps like moneybags, and stored in chests. It is also often noted in the Akershus Registry which charters had seals and were bound together by the strips from which their seals were suspended. This form of archival organization, to tie letters together, was also practiced at Þingeyrar Abbey, as we gather from Árni Magnússon’s notes and copies of the Þingeyrar charters. Letters were not just bound together by the strips for the sake of facilitating archival organization, the interpretation of those letters that were bound together, literally depended on them being seen and read together (see for instance DI III 1896, no. 404, dated 1 October 1393). The strips themselves were often made of the discarded leaves of older charters, or charter drafts, and if they are sufficiently many attached to a single letter, occasionally the text of the discarded letter can be recovered by laying the strips side by side in the right order, as Árni Magnússon did on occasion, according to AM Dipl. Isl. Apogr. 465 (another example is Karlsson 1963b, p. 78).

The size of monastic archives seems to have varied greatly. The archive of Hovedøya Abbey was unusually large, according to The Akershus Registry, since it numbered over 800 charters, while the other archives kept in the same location were more modest in size. To give further comparisons from the Nordic countries, the cartulary of the Augustinian canonry of Æbelholt in Zealand, Denmark, contains transcriptions of 138 charters. The apparently complete monastic archive of the Franciscan Convent of St. Clara in Roskilde, Zealand, now in the Arnamagnæan Collection in Copenhagen, counts 471 charters. The St. Mary cartulary from Sorø Abbey, Zealand, has approximately 100 entries. The cartulary of the Cistercian monastery of Esrum, Zealand, holds transcriptions of 259 documents. The cartulary of the Benedictine monastery of Munkeliv, near Bergen, Norway, has just over 160 charters (Jensson et al. 2018, pp. 14–15).

The above-mentioned Augustinian house at Helgafell, in western Iceland, was among the richest monasteries in Iceland at the end of the Middle Ages. Shortly after 1513, a cartulary was made at the monastery containing copies of its charters concerning land ownership and other rights. The original charters are almost all lost, and the cartulary, which no doubt did not contain the whole archive, survives only in 17th-century copies. According to a modern reconstruction of this lost cartulary, the charters copied numbered 128 (Rafnsson 1979). Measuring the size of a monastic archive is however fraught with difficulty. Charters have different sizes, are often grouped together, and even of limited relevance to the religious houses where they were kept. Some are confirmations of the contents of other charters, so called vidisse, witnessed and sealed transcripts, even of letters that were still found, and there are many further variations. Counting charters is as difficult as counting manuscripts, which is essentially about counting stacks of leaves of different size and thickness, bound in a volume, each stack containing material that doesn’t necessarily belong together.

In accordance with their hybrid written/oral form, charters were designed to be both seen and heard– and no doubt touched and admired too (Green 1994, pp. 228–30; Anderson 2023). The formulaic language of most charters, although not the stylistically simpler máldagar, reveals quite well their hybrid function. Typically, it is a variation of the following: To all good men, who see and hear this letter, the authors send God‘s greeting and their own, making known that such and such holds true. (This is the substance of the letter.) In demonstration of said facts and conditions, and as a greater confirmation, we the aforesaid put our seals to the letter, which is signed in this place and on that day and year. Notwithstanding the vernacular medium, this charter formula or model is calqued from Latin and transparently Roman in origin. It may have come to Iceland from Saxony in the early days of Christianity. The charters are also as a rule dated in Latin, and in compliance with medieval Roman practice. It is worth noting, however, that no charters entirely written in Latin are now preserved in the Þingeyrar Archive. This demonstrates well the functionality of the vernacular as a business language in Iceland, but it obviously does not indicate any rule against using Latin in charters, or that the Thingeyrenses weren‘t able to use Latin. As we have seen, their library was full of Latin books, and besides, the monks of Þingeyrar Abbey were by far the most prolific authors of Latin texts in Iceland (Jensson 2017, 2021c), where charters in Latin are well attested and were often used.

Þingeyrar Abbey and Cloister was to some extent required to keep records and compile an archive. The earliest legally required documents in Iceland were church muniments (mál-dagar), which recorded the property and rights of a church, and the income it could expect. The Icelandic word máldagi refers to the “contract” that was entered into by those responsible for the church. According to the canon law section of the oldest preserved Icelandic law code, the so-called Grágás (literally: Grey Goose), which is transmitted in two manuscripts from the middle of the 13th century, the caretaker of a church was stipulated to register what he and others had donated to the church, and after making the donation to read its notation aloud at the general assembly or at smaller local assemblies. He was also required to read the document aloud once a year in church, at the occasion of a celebrated mass (Finsen 1852, p. 15). By 1281, when Iceland had become a dependency of Norway, a new law code was introduced, the so called Jónsbók (Jónsson 2004), which stipulated that any marriage arrangement or exchange of property above a certain amount, was to be documented in the presence of witnesses, naming place and date, and sealed by a lawman, a sheriff, or the seals of others present. Although not mentioned in this law code, the Icelanders could also ask the brothers of a nearby monastery to compose and seal a charter for them, when important arrangements or financial exchanges were made, as is abundantly exemplified in surviving charters.

It is doubtful, however, that this law was followed to the letter, expecially by laymen. Until the Reformation, no other archives are known in Iceland than those compiled at episcopal sees, monasteries, and, on a much smaller scale, in parochial churches. Secular officials, sheriffs, and district commissioners, usually kept no records. Only the laws and certain amendments, decrees, and responses, were put into writing by lay officials, but no decisions by assemblies or courts. Amazingly enough, until the 17th century, even capital punishment was meeted out without documentation. As for the episcopal sees and parochial churches, documents belonging to these institutions were sometimes difficult to distinguish from the private belongings of bishops and caretakers, whom they often followed. Hence, it was in the monasteries in particular, institutions that were managed by a collective of a sort, and virtually self-owned and self-governed, that archives could most easily form and survive for more than a few generations.

5. The Style and Contents of the Þingeyrar Charters

The stylistic precepts of medieval handbooks on charter writing, artes dictaminis and ars notaria, are discussed in a classic study by Charles H. Haskins (Haskins 1929, pp. 170–92). However, the handbooks included figures of style that were mostly ignored by the practitioners of charter writing, for instance the avoidance of hiatus (the awkward gaping of sounds, when a word preceding another starting with a vowel itself also ends on a vowel) or the preference for cursus (preestablished prosodic patterns of long and short or stressed and unstressed syllables at the end of a sentence). In fact, aesthetic stylistic criteria were generally pushed aside for the cultivation of a specifically precise and matter of fact diplomatic language, as is usefully illustrated in a study of Latin business notarial technique in the Ligurian area of Italy from A.D. 1150–1250. The author, John F. McGovern, defines the two cardinal virtues of notarial rhetoric as (a) clarity and (b) textual unity. As he points out, the high demand for precision in charters usually leads to “singularly graceless” documentary prose (McGovern 1972, p. 299). The unpleasing stylistics are worth enduring, however, for the obvious reasons that charters provide key insights into the function of societal institutions and give access to structural frameworks that impacted medieval (and postmedieval) society. The monastic archive of Þingeyrar Abbey was not just a record of its deeds and transactions, it was in a sense the concretization of its relations to the world. In modern times, it became a symbol of the injustices of colonialism, and subject to negotiations for the repatriation of cultural artefacts.

In this kind of letter writing, special attention was paid to expressions of time (usually in Latin, even in otherwise vernacular letters), descriptions and identifications of persons and places, and the clarification of special terminology. The second principle, the unity of the text, meant that if something was mentioned twice or more often, its secondary occurrences had to be related to its first mention, calling for an unusual frequency of qualifiers such as ‘said’, ‘aforesaid’, ‘selfsame’, ‘same’, and similar. As in other languages, this principle of unity in the Þingeyrar charters put unusual stress on the Icelandic vocabulary, for instance when the basic words -greindur and -nefndur (stated, named) took prefixes such as oft- and þrátt- (oft, continuously) to produce unheard of word formations like oftgreindur and þráttnefndur (DI III 1896, no. 228, DI IV 1897, no. 711). Striving after unity and clarity likewise called for the notary’s exaggerated fondness for conjunctions, adverbs, and participles, intended to bind together, as it were, parts of the document into a single textual unity. Yet another stylistic feature was to insist on the legality and accuracy of statements with abundant use of adj. and adv. such as ‘legally’, ‘inalienable’, and ‘permanent’, as if to magically conjure up an association between the facts and deeds certified by the charter and the wished-for impression of correctness and permanence.

To the same purpose statements of where precisely, even in what building or room of a building the agreement was entered into, often by swearing an oath or by handshake, constitute further forms of charter ritual to make the deeds certified by the charter more final. Incidentally, such charters provide data for building history by naming houses on the monastic premises. On 8 November 1363, Abbot Gunnsteinn of Þingeyrar, and others “in the Abbot Hall at Þingeyrar“ (í ábóta stofunni að Þingeyrum) witness a handshake agreement of the parties to the charter (DI III 1896, no. 170; see his seal in Figure 6). On 16 August, the same Abbot is now “in the Big Hall at Þingeyrar“ (í stóru stofu at Þingeyrum), when he as witness guarantees the veracity of the charter in question (DI III 1896, no. 197). On 8 May 1445, another abbot, Brother Jón of Þingeyrar, ordinis sancti Benedicti, greets everyone who sees or hears his letter, again “in the Big Hall at Þingeyrar” (í stóru stofunni á Þingeyrum) (DI IV 1897, no. 711). It is not impossible that the Abbot Hall was the same building as the Big Hall. The Big Hall may have survived into the 18th century, since it is mentioned in the appraisals of Þingeyrar in 1684 and 1704, where it is described as a large timber frame house with panelled turf walls, furnished with tables and benches, and a high table on a raised platform (Jensson 2022, pp. 304 and 309–10).

Sometimes medieval charters can preserve testimony to unexpected and revealing social circumstances. At Þingeyrar Abbey, 25 August 1437, Bishop Godswin of Hólar confirmed through his episcopal authority that the sisters at Reynistaður Convent in the vicinity had gathered together in the Capitulum building there, and elected as their abess Sister Þóra, whom they had earlier chosen for their prioress. The bishop also uses his authority to give Þóra a dispensation for her age, because she was one year shy of the required age to become abess (DI IV 1897, no. 609). The charter demonstrates that in Medieval Iceland there existed an ecclesiastical institution for women, which was governed by themselves, democratically. This is the same Reynistaður Convent that owned 42 books in Latin and Icelandic, according to Sigurðarregistur. Some charters in fact contain snippets of medieval life comparable to the anecdotes occasionally found in the miracle collections accompanying the many Icelandic lives of holy persons, martyrs, saintly kings, and bishop confessors. On 2 June 1401, it is attested that the priest Einar Þorvarðsson adopted his three illicit children at Þingeyrar Abbey, thus enabling them to inherit his property. The ritual described in the charter, seemingly devised for the occasion, involved him standing before the door of the monastic church at Þingeyrar Abbey together with his children, Magnús, Arngrímur, and Guðrún, and his two sisters, Járngerður and Guðrún, all of them holding on to the same book (it doesn‘t say which), while the said Einar swore an oath to adopt his children, and gave each of them a valuable item as souvenir (DI III 1896, no. 556). The originals of both of these truly wonderful charters are still preserved.

In some charters, it seems that the Abbey stands as guarantor and enabler for the agreement entered into, which is essentially the function of a notary. Sometimes the transactions are quite complicated, for instance, like-kind exchange of land or rights with payments included, the handing over of property or payments, i.e., proof of payment, title deeds etc., which makes it oportune for the eminently literate brothers at the Abbey to be summoned as registrants and witnesses to such deeds. Actually, in matters involving the two strands of medieval society, lay and clergy, the norm seems to have been that an equal number of witnesses from both groups put their seals under the deeds. Often the charter only registers that some other charter is correct and properly transcribed. Such is the transcript charter of 7 October 1441, made at Þingeyrar Abbey (DI IV 1897, no. 664). Abbot Jón and a layman, Þórður Magnússon, put their seals under a precise transcript of a letter from the Royal Cashier in Bergen and Governor of Iceland, Ólafur Nikulásson, regarding the office of his deputy and tax collector. The letter is confirmed by an abbot and a lay man, who thus act as representatives for the two halves of medieval Icelandic society.

While all medieval charters are a manifestation of the binding use of literacy, some make this function of the written word more imperative than others. An interesting case is a charter from Þingeyrar Abbey, dated 8 August 1377 (DI III 1896, no. 267). Bishop Jón the Bald of Hólar (in office 1358–1390), authors this charter at Svínavatn, where he has summoned Abbot Gunnsteinn of Þingeyrar, whom we have already met, and a layman, Bjarni Kolbeinsson, together with his mother Hallótta Pálsdóttir. The matter regards the late husband and father of these people, Kolbeinn Benediktsson, who reputedly at the farm Auðkúlustaðir (no date is given), while sitting on his horse and preparing to ride off to the Eastfjords, (in a fit of generosity?) promised to leave to Þingeyrar Abbey his part of the land belonging to the farm Höfn on Skagi after his death. According to two witnesses, Father Þorsteinn Gunnarsson and Ívar Kolbeinsson, said Kolbeinn Benediktsson shook hands with Father Þorsteinn, who we are told was his parish priest and father confessor, to confirm the donation. Handshakes and oaths made in the presence of witnesses are rituals that prevailed in contract making before the advent of literacy with its sealed charters. The name of this Kolbeinn Benediktsson might imply that he was related to the Benedikt Kolbeinsson, who fourteen years earlier (DI III 1896, no. 155) paid a small fortune to have himself buried under the bell tower (or under one of the two bell towers) of Þingeyrar Abbey Church, where his wife was already buried. According to Árni Magnússon, the present letter may originally have been attached to other charters documenting donations to Þingeyrar Abbey by said Kolbeinn Benediktsson. Evidently, the son and wife did not know of his alleged oral donation to the Thingeyrenses, or they did not wish to validate it, and Bishop Jón the Bald was performing charter magic on a family that had already given its fair share to the Abbey. The bishop does not hesitate to declare the land as legally belonging to the Abbey, and the witnesses are not even asked to swear an oath or to confirm with their seals, what they think they remember the putative dead donor as saying on horseback, before riding off to the east, at an unspecified date in the past.

A revealing letter, dated 20 May 1320, and transmitted only in 17th- and 18th-century copies (DI II 1893, no. 341), demonstrates the helplessness of those who have no charters to show for their property and rights, when this had become a requirement. This letter, which was briefly referred to above, was written in Trondheim, Norway. Brother Þórir, abbot of Munkaþverá, the fraternal monastery of Þingeyrar, and Grímur, abbot of Nidarholm, declare jointly that in the days of the priest Þorkell the Stick, who prepared for the foundation of Þingeyrar Abbey, the holy St. Jón, first bishop of Hólar, granted it the bishop‘s part of the tithe owed to 13 parishes west of the river Vatnsdalsá in the vicinity. They also declare that said tax had always been paid to Þingeyrar Abbey, during the reign of eight Hólar bishops, until Bishop Jörundur of Hólar (in office 1267–1313) by force and without legal investigation into the matter, deprived the Abbey of its share in this tax. The abbots declare further, that during Bishop Jörundur‘s long reign, Abbots Bjarni and Höskuldur of Þingeyrar did not dare to bring the matter before Archbishop Jörundur (in office 1288–1309; not to be confused with Bishop Jörundur), because of the bishop‘s tyrannical style of management (sakir ofríkis). It is stated further that the abbots had already taken the matter up with two archiepiscopal visitatores, who came to Iceland from Nidaros in 1307, although nothing came of it, because the two disagreed about the case among themselves. What the letter does not state, is that Abbot Þórir was one of the two, and the one who took the side of Þingeyrar. The two abbots add that they have ”seen” the men who collected this tax for the Abbey, and “heard” them speak on the matter, further underscoring the hybridity of medieval charter writing. Besides, Abbot Grímur of Nidarholm has sworn “on his soul” that his lord, Archbishop Jörundur, at some point said that Bishop Jörundur’s act was “unjust to the monastery” (órétt vera gjört vit klaustrit), while the priest Auðunn the Steep (bratti) has verbally qualified the inequity of the removal of the tax from Þingeyrar Abbey as “robbery in plain sight” (opinbert rán).

The background and occasion for this charter seems to be that the new and very active head of Þingeyrar, Abbot Guðmundur (in office 1310–1339), who had only a few years earlier rebuilt the nave of the church at Þingeyrar at a great cost to the Abbey, and provided it with new books for its library and bells for its belltower(s) (Storm 1888, p. 272), needed this tax to finance the project, but could not produce any documents to prove the Abbey’s rights to it. This also seems to be the reason why the Abbey lost the tax to Bishop Jörundur in the first place. The tax belonged to the bishop nominally, according to the tithe law, hence its name “Bishop’s Tithe”, which made it unproblematic for the bishop to reclaim it. Abbot Guðmundur was in Norway in the spring of 1320, and the letter looks like his attempt to establish a legitimate documentation for his Abbey’s rights to collect this tax. Of course, the point of the two abbots’ letter was not to provide information on the historical circumstances behind the foundation of Þingeyrar Abbey, although this is what they accidentally did, to the great satisfaction of historians. Nidarholm monastery may, in some sense, have been considered by the Thingeyrenses as their house of origin, hence the importance of the joint declaration of the two abbots about rights assigned to Þingeyrar at its foundation. Indeed, Abbot Guðmundur did not go unrewarded, because when his former client, Brother Laurentius, was consecrated bishop of Hólar (in office 1324–1331), he compensated Þingeyrar Abbey for the loss of this tax, now properly documented through the sworn statements of the two abbots, by donating to the Abbey the farm Hvammur in Vatnsdalur (DI II 1893, no. 363). The charter confirming this donation was among those kept in the archive at Þingeyrar Cloister until around 1900. Incidentally, in 1893, when the historian and archival scholar Jón Þorkelsson (d. 1924) published volume two of the Diplomatarium Islandicum in Copenhagen, he only had access to this charter’s early 18th-century transcription in the collection of Árni Magnússon, and was apparently unaware that the original parchment was still preserved in Iceland.

6. The Þingeyrar Archive Finds a New Home in Iceland

In the 19th century, the Archive of Þingeyrar was still kept in the church or farm of Þingeyrar and counted at least 26 original parchment documents, dating to the period 1200 to 1629, besides a copy of AM 279 4to from 1645 called Þingeyrabók or Rekaskrá. This is not counting the numerous younger documents in the archive. In this period, Björn Ólsen (d. 1850) and his son (Runólfur) Magnús Ólsen (d. 1860) were owners of Þingeyrar farm and held the stewardship of the crown lands of Þingeyrar. The latter, Magnús Ólsen, worked on a historical treatise about Þingeyrar Abbey, in particular its abbots and archive (Reykjavík, The National Library, JS 599 4to; ca. 1850). His son, Björn Magnússon Ólsen (d. 1919), wrote on Old Icelandic and Old Norse subjects, and was among the most astute scholars in the field. He became the first rector of the University of Iceland in 1911.

Around the middle of the 19th century, the expatriate intellectual and historian Jón Sigurðsson (d. 1879) in Copenhagen, who was the first editor of Diplomatarium Islandicum, had his assistant Arnljótur Ólafsson copy Reykjavík, The Arnamagnæan Institute AM 279 4to (Þingeyrabók) and most of the transcripts of the charters from Þingeyrar Archive that were found in the Arnamagnæan Collection in Copenhagen (AM Apogr. 438–504). Jón Sigurðsson himself corrected and certified these transcripts, 17 September 1852, after which they were sent to Magnús Ólsen with a letter from the Governing Council of Iceland in Copenhagen, dated 29 September 1852. Upon receiving the documents Árni Magnússon had transcribed accuratissime in the 18th century, Magnús Ólsen must have recognized among the copies some of the charters still at Þingeyrar. In 1855, Pétur Havsteen (d. 1875), who was governor (amtmaður) of the north and east district of Iceland, demanded that the original charters of Þingeyrar be handed over to the Danish authorities, a request that Magnús Ólsen resisted vehemently. An agreement was reached to the effect that Ólsen could keep the originals, while handing over certified copies. In Copenhagen, Jón Sigurðsson and his successor Jón Þorkelsson, who edited volume 1 (1857–1876) and 2 (1893) of Diplomatarium Islandicum, published the earliest Þingeyrar charters on the basis of Árni Magnússon‘s transcripts, without consulting the originals, which were either still at Þingeyrar or had by then been transferred to the National Library of Iceland.

The scholar Björn Magnússon Ólsen, after inheriting nine of the parchment charters from his father, presented them to the National Library of Iceland, which from 1881 was located in the new Parliament Building in Reykjavík. The National Library, in turn, as late as 1900, handed the letters over to The National Archives of Iceland, which that same year also moved into the Parliament Building. Later, the certified copies made by Magnús Ólsen for Pétur Havsteen were likewise delivered to The National Archives. The year after, 20 February 1901, Benedikt Blöndal (d. 1911), then steward of the Þingeyrar crown lands, turned over to the National Archives sixteen more original parchment charters from Þingeyrar, together with the 1645 copy of Þingeyrabók. Finally, on 20 May 1901, Bjarni Pálsson (d. 1922), priest of Þingeyrar, handed over to The National Archives of Iceland the last parchment charter still kept at Þingeyrar, the so-called “Steinnes Letter”. The history of these documents is briefly outlined in the section on Þingeyrar Archive in vol. 3 of Jón Þorkelsson’s catalogue of the holdings of The National Archives (Þorkelsson 1910, pp. 311–14). At the turn of the 20th century, the Icelandic charters in Copenhagen were still in the collection of Árni Magnússon, 2065 items in all, although 11 were unaccounted for, according to the then recent catalogue of that collection (Kålund 1889–1894, II, p. 612). Finally in 1904, the first of those charters were returned to the National Archives of Iceland, and again in 1928, a full third, while the rest were repatriated with the transcript collection in the great return of 1971–1997, and are now in Reykjavík at the Árni Magnússon Institute.

Funding

This research was funded by the Icelandic Research Fund, grant number 228576-052.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

- Charters and documents at Þingeyrar that were inventoried there in the appraisals of 1773, 17821, and 1783 (the list is not collated with preserved documents):

- “Driftwood and Whale Register” (so-called), parchment, 4to

- “Hóp Estuary Letter”, parchment, 1364

- “Melasandur Letter”, parchment with seals, 1340

- “Landmark Letter on Cloister Lands”, paper, rotten in the middle, there illegible, 1706

- “Margrét Stígsdóttir’s Testimony on Landmarks at Þverá Land”, paper, 1685

- “Legal Confirmation for Skinnastaðir Farm”, paper, 1730

- “Letter on Driftwood and Whale in Hrútafjörður”, illegible, in paper envelope, 1489

- Copy of “Lawman Halldór’s Landmark Letter on Torfalækur and Húnastaðir”, 1629

- “Testimony on Þingeyrar Fishing Rights off Syðriborg”, parchment, 1 seal, 1439

- Vidimus “Sentence on Salmon Fishing off Hjaltabakki”, parchment, 3 hanging seals, 1371 [original from 1359]

- “Landmark Letter between Hólar and Finnsstaðir”, parchment, 1 seal, 1387

- “Legalization of Húnastaðir Land”, paper, 1629

- “Convention with Undirfell Church on Driftwood and Whale on Þingeyrar Sand”, paper, 1724

- “Two Lawmen’s Decisions on Fishing in Hóp Estuary”, parchment, 1 seal, rotten (1310–1318)

- “Hurðarbak Letter”, parchment, 1365

- “Bessastaðir Letter”, parchment, rotten and difficult to read, 1527

- “Sentence on Hafnir Land”, parchment, rotten, 1377

- “Hóp Estuary Letter”, parchment, 1363

- “Torfalækur Letter” (so-called), paper, 1629

- “Akur Letter on Fishing in Húnavatn”, parchment, 1368

- “Donation Letter for Akur á Kólkumýrum”, parchment, poor condition, 1382

- “Guðmundur Sölvason’s Testimony on Húnastaðir Land”, parchment, 1626

- “Hvammur in Vatnsdalur Letter”, parchment, 1329

- “Böðvarshólar Letter”, parchment, 1486

- “Settlement between Bishop Laurentius and Abbot Guðmundur on Hvammur in Vatnsdalur and Húnastaðir”, parchment, 2 hanging seals, 1326

- “Testimony of Ingveldur Sveinsdóttir”, parchment, 1626

- “Þorgrímur Gíslason’s Testimony regarding Húnastaðir Land to Hjalltabakki Driftwood and Whale Landmark”, paper, 1 hanging seal, largely rotten

- “Guðmundur Höskuldsson’s Testimony about Húnastaðir Land”, parchment, 1 hanging seal, 1618

- “Jón Finnbogason’s Testimony about Húnastaðir Land”, parchment, 2 hanging seals, 1626

- “Vakurstaðir Letter”, parchment, 1479

- “Gilsstaðir Letter”, parchment, 1379

- “Guðmundur Sölvason on Húnstaðir Land”, paper, 1629

References

- Anderson, Joel D. 2023. Reimagining Christendom: Writing Iceland’s Bishops into the Roman Church, 1200–350. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ágústsson, Hörður. 1972. Stavbygning. Island. In Kulturhistorisk leksikon for nordisk middelalder XVII. Edited by Georg Rona and Allan Karker. Copenhagen: Rosenkilde og Bagger, pp. 90–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ágústsson, Hörður. 1989. Húsagerð á síðmiðöldum. In Saga Íslands IV. Edited by Sigurður Líndal. Reykjavík: Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag, pp. 293–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ágústsson, Hörður. 1990. Skálholt. Kirkjur. Reykjavík: Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag. [Google Scholar]

- Delumeau, Jean. 2007. Dom Mabillon, le plus savant homme du royaume. Comptes-rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 151: 1779–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diplomatarium Islandicum/Íslenzkt fornbréfasafn II. 1857–1876. Kaupmannahöfn: Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag.

- Diplomatarium Islandicum/Íslenzkt fornbréfasafn II. 1893. Kaupmannahöfn: Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag.

- Diplomatarium Islandicum/Íslenzkt fornbréfasafn III. 1896. Kaupmannahöfn: Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag.

- Diplomatarium Islandicum/Íslenzkt fornbréfasafn IV. 1897. Kaupmannahöfn: Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag.

- Diplomatarium Islandicum/slenzkt fornbréfasafn IX. 1906–1913. Kaupmannahöfn: Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag.

- Duranti, Luciana. 1989. Diplomatics: New uses for an Old Science. Archivaria 28: 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Finsen, Vilhjálmur, ed. 1852. Grágás. Islændernes lovbog i fristatens tid, udgivet efter Det Kongelige Bibliotheks Haandskrift [GKS 1157 fol.]. Copenhagen: Det Nordiske Literatur-Samfund. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Dennis Howard. 1994. Medieval Listening and Reading: The Primary Reception of German Literature 800–1300. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 228–30. [Google Scholar]

- Grímsdóttir, Guðrún Ása, ed. 1998. Lárentíus saga biskups. In Biskupasögur III. Íslenzk fornrit. Reykjavík: Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag, pp. 213–441. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnlaugsson, Guðvarður M. 2016. Voru scriptoria í íslenskum klaustrum. In Íslensk klausturmenning á miðöldum. Edited by Haraldur Bernharðsson. Reykjavík: Miðaldastofa, pp. 173–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen, Kaja Merete. 2021. O, Holy Cross, You are All Our Help and Comfort: Wonderworking Crosses and Crucifixes in Late Medieval and Early Modern Norway. Oslo: Department of Theology. [Google Scholar]

- Halldórsson, Ólafur. 1998. Árni Magnússon (1663–1730). In Medieval Scholarship. Biographical Studies on the Formation of a Discipline I–III. Edited by Helen Damico and Joseph B. Zavadil. New York & London: Garland, vol. II, pp. 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Harðardóttir, Guðrún. 2017. Innanbúnaður kirkna á fyrstu öldum eftir siðaskipti. In Áhrif Lúthers. Siðaskipti, samfélag og menning í 500 ár. Edited by Hjalti Hugason, Loftur Guttormsson and Margrét Eggertsdóttir. Reykjavík: Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag, pp. 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Haskins, Charles H. 1929. Studies in Medieval Culture. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helgadóttir, Þorbjörg, ed. 2010. Rómverja saga I–II. Reykjavík: Stofnun Árna Magnússonar. [Google Scholar]

- Jensson, Gottskálk. 2017. Latin Hagiography in Medieval Iceland. In Corpus Christianorum. Hagiographies: International History of the Latin and Vernacular Hagiographical Literature in the West from its Origins to 1550. Edited by Monique Gaullet. Turnhout: Brepols, vol. VII, pp. 875–949. [Google Scholar]

- Jensson, Gottskálk. 2021a. Udgivelse af norrøn litteratur indtil 1772. In Dansk Editionshistorie I–IV. Edited by Johnny Kondrup, Britta Olrik Frederiksen and Johnny Kondrup. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum, vol. II, pp. 47–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jensson, Gottskálk. 2021b. Lærdomshistorisk udvikling, motivering og metode. In Dansk Editionshistorie I–IV. Edited by Johnny Kondrup, Britta Olrik Frederiksen and Johnny Kondrup. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum, II, pp. 160–213. [Google Scholar]

- Jensson, Gottskálk. 2021c. Þingeyrar Abbey in Northern Iceland: A Benedictine Powerhouse of Cultural Heritage. Religions 12: 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensson, Gottskálk. 2022. Heimildir um klausturkirkjuna og bókasafnið á Þingeyrum. Gripla 33: 265–327. [Google Scholar]

- Jensson, Gottskálk, Alex Speed Kjeldsen, and Beeke Stegmann. 2018. A Fragment of Norwegian Royal Charters from ca. 1205: A Diplomatic Edition and Analysis. Opuscula 16: 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jónsson, Már, ed. 2004. Jónsbók. Lögbók Íslendinga hver samþykkt var á alþingi árið 1281 og endurnýjuð um miðja 14. öld en fyrst prentuð árið 1578. Reykjavík: Háskólaútgáfan. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, Stefán. 1963a. Islandske Originaldiplomaer indtil 1450 I. [Text.] Editiones Arnamagnæanæ, Series A. Vol. 7. Copenhagen: Munksgaard. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, Stefán. 1963b. Islandske Originaldiplomaer indtil 1450 II. [Facsimiles.] Editiones Arnamagnæanæ, Supplementum 1. Copenhagen: Munksgaard. [Google Scholar]

- Kaalund, Kristian. 1889–1894. Katalog over Den Arnamanæanske Handskriftsamling I–II. Copenhagen: Arnamagnæan Commission & Gyldendal. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjánsdóttir, Steinunn. 2021. Lokun íslensku miðaldaklaustranna. Ritröð Guðfræðistofnunar 53: 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, L., ed. 1900. Kancelliets Brevbøger vedrørende Danmarks indre forhold, i udrag. 1576–1579. Copenhagen: Rigsarkivet & Reitzel. [Google Scholar]

- Lárusson, Magnús Már, and Jónas Kristjánsson, eds. 1965–1967. Sigilla Islandica I–II. Reykjavík: Handritastofnun Íslands. [Google Scholar]

- McGovern, John F. 1972. The Documentary Language of Mediaeval Business, A.D. 1150–1250. The Classical Journal 67: 227–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mósesdóttir, Ragnheiður. 1996. Bessastaðabók og varðveisla Viðeyjarklaustursskjala. Saga. Tímarit Sögufélagsins 34: 219–54. [Google Scholar]

- Nordal, Sigurður. 1970. Bókasafnið á Þingeyrum. Húnavaka 10: 1, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rafnsson, Sveinbjörn. 1979. Skjalabók Helgafellsklausturs. Registrum Helgafellense. Saga. Tímarit Sögufélags 17: 165–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rafnsson, Sveinbjörn. 1987. Árni Magnússons historiska kritik. Till frågan om vetenskapssynen bakom Den Arnamagnaeanska samlingen. In Över gränser. Festskrift till Birgitta Odén. Edited by Ingemar Norrlid, Lars Olsson and Bengt Sandin. Lund: The Historical Institute & University of Lund, pp. 293–316. [Google Scholar]

- Storm, Gustav, ed. 1888. Islandske annaler indtil 1578. Oslo: Grøndal & Det norske historiske Kildeskriftfond. [Google Scholar]

- Tank, Gunnar, ed. 1916. Akershusregistret af 1622: Fortegnelse optaget af Gregers Krabbe og Mogens Høg paa Akershus slot over de derværende breve. Oslo: Den norske historiske Kildeskriftkommission. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by Cormack, Margaretand. 2021, The Saga of St. Jón of Hólar. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Þorkelsson, Jón. 1910. Skrá um skjöl og bækur í Landsskjalasafninu í Reykjavík III. Reykjavík: Gutenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Þórólfsson, Björn Karel. 1953. Íslenzk skjalasöfn. Skírnir 127: 112–35. [Google Scholar]

- Þorsteinsson, Hannes. 1922–1927. Annales Islandici Posteriorum Sæculorum/Annálar 1400–1800 I. Reykjavík: Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag. [Google Scholar]

- Wallem, Fredrik B. 1910. De islandske kirkers udstyr i middelalderen. Aarsberetning for Norske Oldtidsminnesmerkers Bevaring. Christiania: Grøndahl & søns bogtrykkeri. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).