Building a More Inclusive Workplace for Religious Minorities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Religion-Based Discrimination in the Workplace

1.2. Workplace Discrimination for Using the Islamic Veil

1.3. The Role of Religious Associations in Overcoming Workplace Discrimination

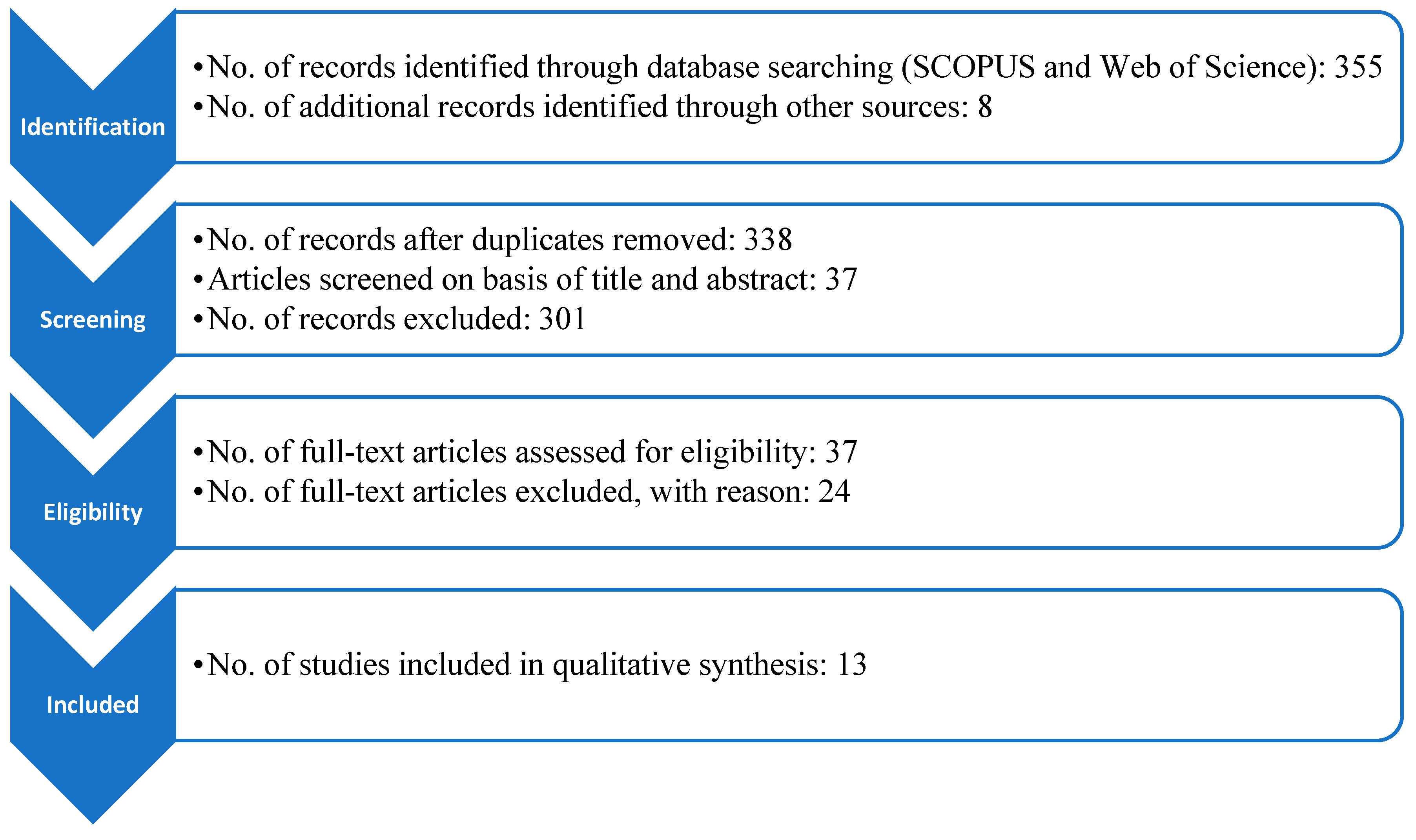

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. How to Overcome Discrimination? Employees’ Perspective

3.2. How to Overcome Discrimination? Companies’ Perspective

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al Ariss, Akram, and Yusuf M. Sidani. 2016. Understanding Religious Diversity: Implications from Lebanon and France. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management 23: 467–80. [Google Scholar]

- Alidadi, Katayoun. 2012. Reasonable accommodations for religion and belief: Adding value to article 9 ECHR and the European Union’s anti-discrimination approach to employment? European Law Review 37: 693–715. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Stuart, Peter Williams, and Danielle Allen. 2018. Human Resource Professionals’ Competencies for Pluralistic Workplaces. The International Journal of Management Education 16: 309–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, Adriana, Olga Serradell, and Marta Soler. 2013. Sharing the differences in the same space. Societal community or patriotism of the constitution? Scripta Nova-Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales 17: 427. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, Lia. 2016. Critical and Creative Research Methodologies in Social Work. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Campdepadrós-Cullell, Roger, Miguel Ángel Pulido-Rodríguez, Jesús Marauri, and Sandra Racionero-Plaza. 2021. Interreligious Dialogue Groups Enabling Human Agency. Religions 12: 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoffersen, Lisbet, and Niels Valdemar Vinding. 2013. Challenged Pragmatism: Conflicts of Religion and Law in the Danish Labour Market. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 13: 140–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Botton, Lena, Emilia Aiello, Maria Padrós, and Patricia Melgar. 2021a. Solidarity Actions Based on Religious Plurality. Religions 12: 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Botton, Lena, Raul Ramos, Marta Soler-Gallart, and Jordi Suriñach. 2021b. Scientifically Informed Solidarity: Changing Anti-Immigrant Prejudice about Universal Access to Health. Sustainability: Science Practice and Policy 13: 4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerflinger, Nadja, Dries Bosschaert, Adeline Otto, Tim Opgenhaffen, and Lander Vermeerbergen. 2021. Between Morals and Markets? An Interdisciplinary Conceptual Framework for Studying Working Conditions at Catholic Social Service Providers in Belgium and Germany. Journal of Business Ethics: JBE 172: 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2017. Communication of the Commission. A Better Workplace for All: From Equal Opportunities towards Diversity and Inclusion. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- European Network Against Racism (ENAR). 2015. Managing Religious Diversity in the Workplace: A Good Practice Guide. Brussels: European Network Against Racism. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. 2017. Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey: Muslims: Select Findings. Vienna: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. [Google Scholar]

- Flecha, Ramon. 2004. Laïcitat Multicultural. Papers. Revista de Sociología 44: 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Foblets, Marie-Claire. 2013. Freedom of Religion and Belief in the European WorkplaceWhich Way Forward and What Role for the European Union? International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 13: 240–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forstenlechner, Ingo, and Mohammed A. Al-Waqfi. 2010. ‘A Job Interview for Mo, but None for Mohammed’: Religious Discrimination against Immigrants in Austria and Germany. Personnel Review 39: 767–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frégosi, Franck, and Deniz Kosulu. 2013. Religion and Religious Discrimination in the French Workplace: Increasing Tensions, Heated Debates, Perceptions of Labour Unionists and Pragmatic Best Practices. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 13: 194–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Yeste, Carme, Ouarda El Miri Zeguari, Pilar Álvarez, and Teresa Morlà Folch. 2020. Muslim Women Wearing the Niqab in Spain: Dialogues around Discrimination, Identity and Freedom. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 75: 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Yeste, Carme, Lena de Botton, Pilar Alvarez, and Roger Campdepadros. 2021. Actions to Promote the Employment and Social Inclusion of Muslim Women Who Wear the Hijab in Catalonia (Spain). Sustainability 13: 6991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebert, Diether, Sabine Boerner, Eric Kearney, James E. King, Kai Zhang, and Lynda Jiwen Song. 2014. Expressing Religious Identities in the Workplace: Analyzing a Neglected Diversity Dimension. Human Relations 67: 543–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghumman, Sonia, and Ann Marie Ryan. 2013. Not Welcome Here: Discrimination towards Women Who Wear the Muslim Headscarf. Human Relations; Studies towards the Integration of the Social Sciences 66: 671–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girbés-Peco, Sandra, Regina Gairal-Casadó, and Luis Torrego-Egido. 2019. The Participation of Roma and Moroccan Women in Family Education: Educational and Psychosocial Benefits. Culture and Education 31: 754–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, Aitor, María Padrós, Oriol Ríos, Liviu-Catalin Mara, and Tepora Pukepuke. 2019. Reaching Social Impact Through Communicative Methodology. Researching with Rather Than on Vulnerable Populations: The Roma Case. Frontiers in Education 4: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halrynjo, Sigtona, and Merel Jonker. 2016. Naming and Framing of Intersectionality in Hijab Cases—Does It Matter? An Analysis of Discrimination Cases in Scandinavia and The Netherlands. Gender, Work, and Organization 23: 278–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambler, Andrew. 2016. Managing workplace religious expression within the legal constraints. Employee Relations 38: 406–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Riaz. 2019. Why size matters: Majority/minority status and Muslim piety in South and Southeast Asia. International Sociology 34: 307–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heliot, Ying Fei, Ilka H. Gleibs, Adrian Coyle, Denise M. Rousseau, and Céline Rojon. 2020. Religious identity in the workplace: A systematic review, research agenda, and practical implications. Human Resource Management 59: 153–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, Josef, and Sascha Kneip. 2020. The Rise of Faith-Based Welfare Providers in Germany and Its Consequences. German Politics 29: 244–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, Josef. 2017. From Private to Religious Patriarchy: Gendered Consequences of Faith-Based Welfare Provision in Germany. Politics and Religion 10: 515–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Itxaso, María Elósegui. 2019. The balancing and the open neutrality against the religious and racial discrimination in the sentence of the German Constitutional Court of 2015 about the use of the headscarf by teachers. Revista de Derecho Político 104: 295–347. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, Hanane. 2018. The Hijab and Work: Female Entrepreneurship in Response to Islamophobia. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 31: 421–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfaoui, Andrea, Rocío García-Carrión, Lourdes Villardón-Gallego, and Elena Duque. 2020. Help and Solidarity Interactions in Interactive Groups: A Case Study with Roma and Immigrant Preschoolers. Social Sciences 9: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfaoui, Andrea, Ana Burgués, Elena Duque, and Ariadna Munté. 2021a. Believers, Attractiveness and Values. Religions 12: 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfaoui, Andrea, Rocío García-Carrión, and Lourdes Villardón-Gallego. 2021b. A Systematic Review of the Literature on Aspects Affecting Positive Classroom Climate in Multicultural Early Childhood Education. Early Childhood Education Journal 49: 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liberati, Alessandro, Douglas G. Altman, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Cynthia Mulrow, Peter C. Gøtzsche, John P. A. Ioannidis, Mike Clarke, P. J. Devereaux, Jos Kleijnen, and David Moher. 2009. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 62: e1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Malović, Nenad, and Kristina Vujica. 2021. Multicultural Society as a Challenge for Coexistence in Europe. Religions 12: 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, David W., Faith WamburaNgunjiri, and James D. LoRusso. 2017. Human Resources Perceptions of Corporate Chaplains: Enhancing Positive Organizational Culture. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 14: 196–215. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G. Altman, and Prisma Group. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine 6: e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pio, Edwina, and Jawad Syed. 2018. To Include or Not to Include? A Poetics Perspective on the Muslim Workforce in the West. Human Relations; Studies towards the Integration of the Social Sciences 71: 1072–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigvert, Lidia, Elena Duque, Guiomar Merodio, and Patricia Melgar. 2022. A Systematic Review of Family and Social Relationships: Implications for Sex Trafficking Recruitment and Victimisation. Families, Relationships and Societies 20: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigvert, Lídia, Miranda Christou, and John Holford. 2012. Critical Communicative Methodology: Including Vulnerable Voices in Research through Dialogue. Cambridge Journal of Education 42: 513–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido Rodríguez, Miguel Ángel, and Lena de Botton Fernández. 2013. Une Nouvelle Laïcité Multiculturelle. RIMCIS. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences 2: 236–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido, Cristina M., Ana Vidu, Roseli Rodrigues de Mello, and Esther Oliver. 2021. Zero Tolerance of Children’s Sexual Abuse from Interreligious Dialogue. Religions 12: 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Sama, Gisela, Javier Díez-Palomar, Roger Campdepadrós, and Teresa Morlà-Folch. 2020. Communicative Methodology: Contributions to Social Impact Assessment in Psychological Research. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roda, Ferrán Camas. 2016. El Ejercicio del Derecho de Libertad Religiosa en el Marco Laboral. Albacete: Editorial Bomarzo. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Moya, Almudena. 2014. Religion in companies: Conflicts and solutions. Estudios Eclesiásticos 89: 817–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Montse, Montse Yuste, Lena de Botton, and Rosamaria Kostic. 2013. Communicative Methodology of Research with Minority Groups: The Roma Women’s Movement. International Review of Qualitative Research 6: 226–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekerka, Leslie Elizabeth, and Marianne Marar Yacobian. 2018. Fostering Workplace Respect in an Era of Anti-Muslimism and Islamophobia: A Proactive Approach for Management. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 37: 813–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, Amartya. 2012. The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian History, Culture and Identity. Daryaganj: Penguin Books India. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Reetesh K., and Mansi Babbar. 2021. Religious Diversity at Workplace: A Literature Review. Humanistic Management Journal 6: 229–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, Marta, and Aitor Gómez. 2020. A Citizen’s Claim: Science with and for Society. Qualitative Inquiry: QI 26: 943–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styhre, Alexander. 2014. Gender Equality as Institutional Work: The Case of the Church of Sweden. Gender, Work, and Organization 21: 105–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyeri-Erdemir, Tuğba, Zana Çitak, Theresa Weitzhofer, and Muharrem Erdem. 2013. Religion and Discrimination in the Workplace in Turkey: Old and Contemporary Challenges. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 13: 214–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, Memoona, and Jawad Syed. 2017. Intersectionality at Work: South Asian Muslim Women’s Experiences of Employment and Leadership in the United Kingdom. Sex Roles 77: 510–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torras-Gómez, Elisabeth, Mengna Guo, and Mimar Ramis. 2019. Sociological Theory from Dialogic Democracy. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences 8: 216–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, Floris, and Rabia El Morabet Belhaj. 2013. Accommodating Religious Claims in the Dutch Workplace: Unacknowledged Sabbaths, Objecting Marriage Registrars and Pressured Faith-Based Organizations. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 13: 113–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, Lucy. 2007. Religion and Belief Discrimination in Employment: The EU Law. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Vila Porras, Carolina, and Iván-Darío Toro-Jaramillo. 2020. Spirituality and Organizations: A Proposal for a New Company Style Based on a Systematic Review of Literature. Religions 11: 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Peter, and Stuart Allen. 2020. Designed for Inclusion: André Delbecq’s Approach in Multi-Faith Environments. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 17: 45–50. [Google Scholar]

| Reference | Context | Methodology | Participants | Outcomes to Overcome Discrimination | Policy Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tariq and Syed (2017) | The United Kingdom | Semi-structured interviews | 20 Muslim women from South Asian heritage who were in a managerial or a leadership position such as chief executive officer, company director, entrepreneur, or senior manager |

|

|

| Foblets (2013) | England, The Netherlands, Denmark, Bulgaria, France and Turkey | Conceptual | Socio-legal analysis | - |

|

| Al Ariss and Sidani (2016) | Lebanon, France | Conceptual | Historical analysis | - | Legislators and policy makers:

|

| Rodríguez Moya (2014) | Spain | Conceptual | Analysis | - | 1. Provide a welcoming environment devoid of strong religious identities. 2. Offer religious diversity seminars that allow employees to learn about different faiths, their history, and geographical location. 3. Explain the legal framework of religious freedom as a fundamental right. Content and limits. 4. Allow the expression of religious symbols of a personal nature. 5. Making the working hours as flexible as possible, to allow for fulfilment of religious duties. 6. Encourage a variety of menus in company canteens, if any. 7. Provide places for prayer. 8. Create a handbook on good practice of religious matters. |

| Christoffersen and Vinding (2013) | Denmark | Conceptual | Socio-legal analysis | - | It is necessary to ensure that a balance is maintained between the rights of the individual religious employee and the rights of the secular employer. |

| Elóstegui Itxaso (2019) | Germany | Conceptual | Legal analysis |

| - |

| Pio and Syed (2018) | The West | Conceptual | Poetics perspective | - |

|

| Allen et al. (2018) | The United States | Delphi Study | 16 highly experienced professionals in HR practice, research, and teaching | - |

|

| Sekerka and Yacobian (2018) | The United States | Conceptual | Analysis of representative Equal Employment Opportunity Commission cases | - | Managers need to foster organizational learning that tackles emerging forms of discrimination, such as Islamophobia. A sustained focus on moral development becomes imperative toward establishing an ethical climate and a workplace that fosters respect for all organizational members. |

| Miller et al. (2017) | The United States | Interviews | 10 with HR personnel ranging from chief HR officers to middle managers and their assistants |

| - |

| Tanyeri-Erdemir et al. (2013) | Turkey | Conceptual | Socio-legal analysis |

| - |

| Frégosi and Kosulu (2013) | France | Conceptual | Socio-legal analysis | - |

|

| Vermeulen and El Morabet Belhaj (2013) | The Netherlands | Conceptual | Socio-legal analysis |

| - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garcia-Yeste, C.; Mara, L.-C.; de Botton, L.; Duque, E. Building a More Inclusive Workplace for Religious Minorities. Religions 2022, 13, 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060481

Garcia-Yeste C, Mara L-C, de Botton L, Duque E. Building a More Inclusive Workplace for Religious Minorities. Religions. 2022; 13(6):481. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060481

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcia-Yeste, Carme, Liviu-Catalin Mara, Lena de Botton, and Elena Duque. 2022. "Building a More Inclusive Workplace for Religious Minorities" Religions 13, no. 6: 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060481

APA StyleGarcia-Yeste, C., Mara, L.-C., de Botton, L., & Duque, E. (2022). Building a More Inclusive Workplace for Religious Minorities. Religions, 13(6), 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060481