Jesus, the Anthropologist: Patterns of Emplotment and Modes of Action in the Parables

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (A)

- In Section 2 “Action & Narratives”, we first summarize some results of the aforesaid “anthropology of action”. Then, we will relate the modes of action it identifies to specific modes of emplotment. In other words, we will consider patterns of “action” and of “narration” as a whole.

- (B)

- In Section 3. “What Parables Did Jesus Tell?”, we examine which parables may be related to the historical Jesus with a higher degree of probability than other narratives do. We thus isolate a core group of four parables.

- (C)

- In Section 4. “Beyond Historical Attestations: The Rhetoric of the Parables”, we take into account some of the criticisms addressed to the probability approach used for the above-mentioned selection of four parables. We then insert these four core parables into networks of similar stories (narrative networks). We are thus enabled to work at two levels: (a) on a restricted corpus (i.e., the four parables) that provides basic modes of emplotment; (b) on an enlarged corpus characterized (at least in the view of some scholars) by a lower degree of probability as to its direct attribution to Jesus, but whose narrative logic fits into the patterns exhibited by the restricted corpus.

- (D)

- In Section 5. “Galilee: The Social & Mental”, we locate our stories in the context of Jesus’ time. We thus describe and assess local variables that bear upon a person or a community’s election of a course of action in a specified context.

- (E)

2. Action and Narration

2.1. Modes of Action: Towards a Typology

“The cultivation of yams (Dioscorea alata L.), as practiced by the Melanesians of New Caledonia, seems to me to be a good example of what I will call negative indirect action. There is never, so to speak, any brutal contact in space or simultaneity in time with the domesticated being. A ridge of topsoil is carefully constructed, then the seed yams are placed in it. If one wants to obtain a giant tuber, it is necessary to have arranged a vacuum there which this one will fill […] The breeding of the sheep, such as it was practised in the Mediterranean area, seems to me on the contrary the model of the positive direct action. It requires a permanent contact with the domesticated being. The shepherd accompanies his flock night and day […]. His action is direct: contact by the hand or the stick, clods of earth thrown with the rod, the dog which bites the sheep to direct it. His action is positive: he chooses the itinerary that he imposes on the herd at each moment”.

“The qualification of an action can only be relative each action being considered in relation to other alternative actions aiming at the same objective. Whatever the weight of the constraints, there are always several ways of doing things. What is significant is to know the choices made among several possible actions and to see whether, in these choices, a predilection or an aversion for certain types of action is manifest. […] Each society uses a whole range of types of action (direct and indirect, interventionist and passive, continuous and discontinuous, etc.), without it always being possible or desirable to deduce from this a general propensity for this or that mode of action. […] The lesson to be learned from Haudricourt is the proximity to the concrete. To know a little more about human beings, it is necessary to observe and describe their ways of acting as closely as possible”.

- (a)

- An action is passive, active, or interventionist. (Interventionism corresponds to the highest degree of activism, such as is the action of diverting the course of rivers; laissez-faire corresponds to the other extremity of the dimension here described.)

- (b)

- An action is endogenous (the agent acts by herself), exogenous (the agent makes a third player intervene on her behalf), or participative (the agent participates in a process that goes beyond her reach).

- (c)

- Direct action tends entirely toward its objective, while indirect action is oblique (a wheel transforms circular movement into linear movement).

- (d)

- An action is positive (it leads towards an objective), negative (it prevents the accomplishment of an alternative objective), or contrary (it runs counter to the intended objective).

- (e)

- The action can be “internal” (pruning the plants of a garden) or “external” (working the soil of the same garden so as to obtain a specified result over the plants).5

- (f)

- Finally, the continuous action works by repetition, the discontinuous action by the irreversibility of its consequences (Ferret 2012, p. 133).6

2.2. Enchainment of Actions as Narrative Plot

3. What Parables Did Jesus Tell?

3.1. Assessing Plausibility

3.2. Applying Criteria

4. Beyond Historical Attestations: The Rhetoric of the Parables

4.1. The Limits of Historical-Critical Methods

4.2. Networks of Stories

5. Galilee: The Social and the Mental

5.1. Scarcity and Reciprocity

5.2. Skills and Professional Culture

6. From Storytelling to a Specific Typology of Action

6.1. The Mustard Seed Storyline [Mk, Mt, Lk] and Related Parables; The Unlimited Potential of Discontinuous Actions

- -

- A comparison between the Kingdom of God and everyday realities is introduced.

- -

- A mustard seed (reported as the smallest of all the seeds in two of the versions) is sown in the soil, a field, and a garden.

- -

- This grain grows until it becomes “the largest vegetable plant” (two versions) which can be compared to a tree (two versions).

- -

- The result of the growth is that the birds lodge on the branches or in the shade of the shrub produced.

- (1)

- They all highlight an initial action—sowing or mixing yeast in the flour—which is discontinuous in nature: no subsequent action is required, and the consequences of the initiative turn out to be inescapable. In the case of the Mustard Seed story, the impression of inescapability is reinforced by choice of the species: Pliny writes of wild mustard that “it is extremely difficult to rid the soil of it when once sown there, the seed when it falls germinating immediately”. (Natural History, XIX-54 (Pliny the Elder 1856, p. 197)).

- (2)

- Maybe with the exception of the Darnel parable (although the final mention of the granaries where the wheat is gathered still introduces the theme of plentifulness), all stories emphasize the contrast between the minuteness of the initial action and of its object, on the one hand, and bountiful results, on the other hand. (In the case of the parable of the Sower, such consequence happens only in one of the cases being discussed, but, then, the harvest is described as being especially plentiful). An initial commitment is fraught with consequences that go beyond predictions—in this case, happy and fruitful consequences.

6.2. The Homicidal Vinedressers [Mk, Mt, Lk] and the Fig Tree: A Reverse Image of the Growth Process

- -

- An introduction sees an owner planting a vineyard and entrusting it to tenants.

- -

- The owner sends servants to claim the product of the vineyard. With variations from one version to another, the servants are rejected, beaten, or even put to death.

- -

- The owner sends his son, believing that he will be respected.

- -

- So as to monopolize the inheritance, the tenants kill the son, and they leave his corpse outside the vineyard without burial.

6.3. The Great Supper [Mt, Lk] and Related Stories: From Reciprocity to Gratuitousness

- -

- A man (perhaps a king) provides a great banquet (possibly a wedding feast for his son).

- -

- He sends one or more slaves to summon guests. These guests seem to have a certain social status and possess riches.

- -

- The same guests, pretexting their business, refuse to come (whereas things were undoubtedly already settled, which suggests an existing network of relationships between the different actors), thus causing a serious affront to the host.

- -

- Consequently, the latter sends his slaves to gather people of much more modest conditions, and the room of the banquet is eventually filled to capacity.

6.4. The Talents (or Mines) [Mt; Lk] and Related Stories: Growth as a Result of Risk-taking

- -

- A (noble) man goes on a journey and summons his slaves (three or ten).

- -

- He entrusts each one with a different amount of money, with the same instruction: to make it grow.

- -

- On his return, he settles the accounts with them.

- -

- The first servants happen to have secured exceptional returns, in absolute amount (Matthew) or in relative gain (Luke). The master congratulates them, and he entrusts them with accrued responsibilities.

- -

- A long, intense exchange follows. The remaining servant had buried his capital rather than make it bear fruit, afraid as he was (he explains) of the harshness of his greedy master. He returns the initial sum. The master severely blames him, and he transfers the deposit to the most deserving of the servants.

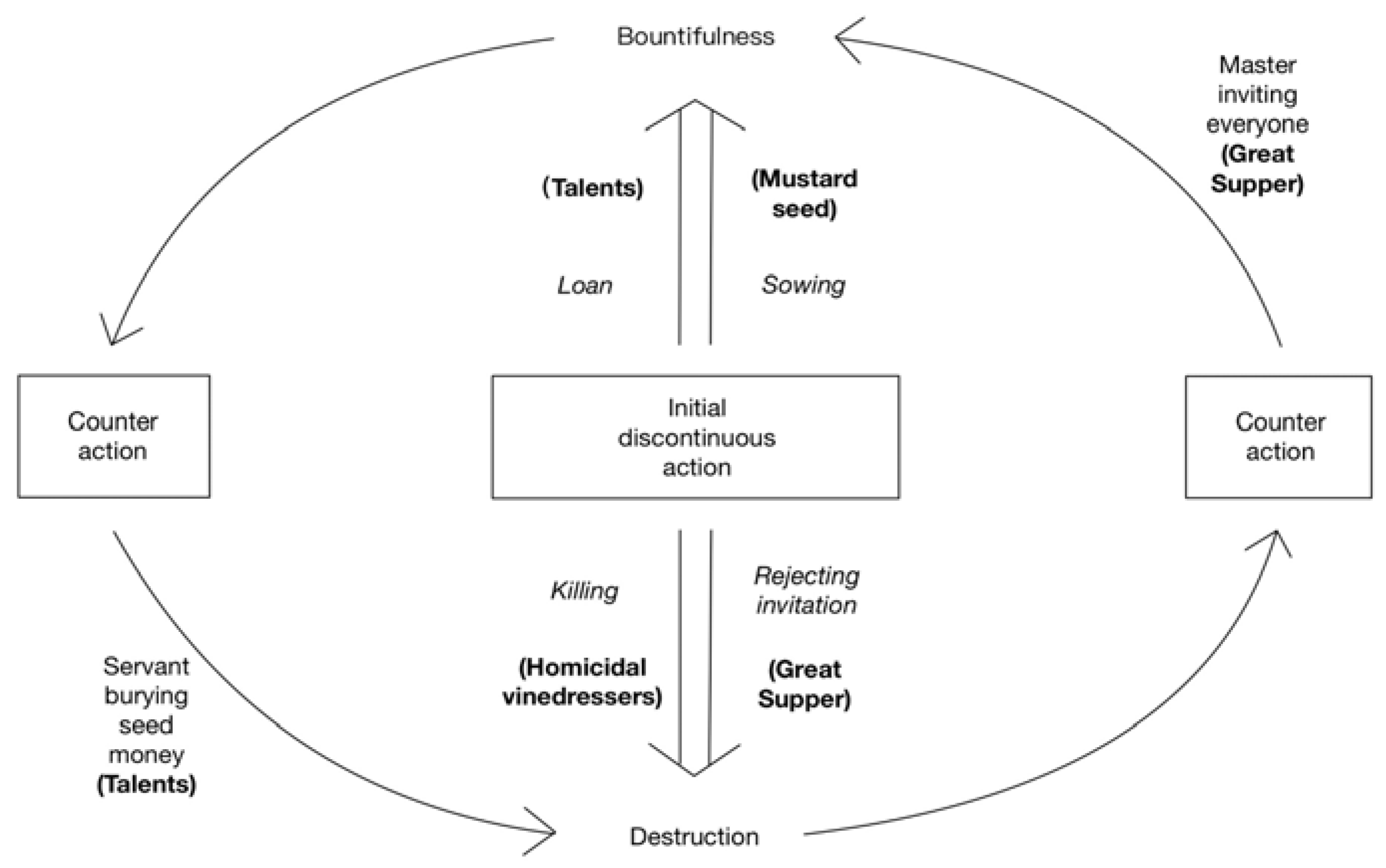

6.5. Unearthing a Meta-Narrative Matrix

6.6. Initiating and Re-Initiating

- -

- The lessons to be drawn from natural realities lead the wise observer to provide precedence to growth factors over any other consideration and to similarly prioritize processes conducive to growth in the social and supranatural realms.

- -

- The process of unimpaired growth is nurtured by a logic of uninterrupted exchange.

- -

- Exchange is activated by two mechanisms: obligation (contractual, statutory, or moral); and risk-taking.

- -

- Interrupting the exchange induces a reverse dynamic, that of destruction unless it can be restarted on the basis of an initiative (a discontinuous counter-action, often characterized by risk-taking) that will change the very nature of the relationships at stake.

- -

- In the end, our narratives illustrate the workings of the logic of reciprocity and risk-taking in society. They also exemplify the crises that the breaking-down of such logic produces, and they suggest to transmute reciprocity into gratuitousness so as to transcend the “inescapable” character attached to both the triggering of social mechanisms and the consequences of their dysfunctions.

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The Greek term of the Septuagint, parabolē translates the Hebrew māšāl, which is very polysemous. I do not enter here into the overabundant history of the interpretation of parables. One can consult, for example, (Snodgrass 2008), a late fruit of the exegetical schools developed since Adolf Jülicher (1857–1938) (on the latter’s exegetical principles, consult Van Eck 2009). |

| 2 | As one sees, my definition of “local knowledge” is larger than those that mainly focus on ecological or medicinal knowledge for instance. It understands local knowledge as an integrated system of representations that unify standpoints and experiences about relationships between persons, the community and its natural environment, and finally, humans and the supranatural world. |

| 3 | In addition to the obvious presence of several modes of action in the same society, the criticisms levelled at Haudricourt have also focused on the confusion he maintained between three levels of analysis: individual behaviors; representations of the human, society and nature; and the actual functioning of social systems. I will not go back over these criticisms, which are summarized in (Ferret 2012). |

| 4 | The concept of wu wei is sometimes translated as “action without effort”. This is indeed a type of indirect action, very close to the one that Haudricourt claims to be typical of “oriental” societies. A paradigmatic example of effortless action is provided by the legend of one of the mythical Chinese emperors sitting among the fishermen to engage in the same work. After he had spent one year with them, the fishermen were offering each other the fish and the best coves. It was the attitude of the Sage Emperor (not his words) that transformed their behavior. This story is mentioned in particular in the first chapter of the Huainanzi, a text whose overall orientation is close to that of the Guanzi, quoted just below. On the various variants of the wu wei concept, see (Slingerland 2003). |

| 5 | Note that Haudricourt was using the words “direct” and “indirect” for what Ferret terms as being “internal” and “external”. |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Since 1991, John P. Meier has developed an exegetical-historical work (A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus) of which, to date, five volumes have been published, the last, in 2016, devoted to the examination of the parables. |

| 8 | One often speaks of ‘authenticity criteria”. At least in the way Meier makes use of them it would be better to speak of “plausibility criteria”. |

| 9 | The “Q [Source]” (German: Quelle) is a term that refers to the hypothetical reconstruction of material common to the Gospels of Luke and Matthew and unknown to Mark. It would have formed a collection of sayings of Jesus made around the year 50. Debates about its composition and even its existence are still going on, even if the existence of such a document remains the dominant hypothesis. |

| 10 | The Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke are close enough that their episodes can be compared using a columnar reading, “at a glance” (synopsis). John’s follows an entirely different arrangement. |

| 11 | This is, moreover, the usual meaning of the term parabolē in the context of the gospel writings, and it is the exegetes who have subsequently extended its meaning. We do not, therefore, classify here the “similitudes” that are contained in a short sentence as parables proper. |

| 12 | A collection of sayings of Jesus, the earliest surviving manuscript version of which dates from the fourth century and was probably written in Coptic on the basis of a Greek original, the Gospel of Thomas continues to be the subject of heated debate as to its dating, its milieu of origin and inspiration, and its exegetical and historical authority. For Meier and others, the literary and lexical analysis of Thomas shows that, far from being a primitive set, it illustrates a tendency to harmonize earlier sources, tendency that can be found in other second-century Christian authors. |

| 13 | Matthew’s and (especially) Luke’s own traditions each contain more parables than Mark’s and Q’s traditions combined. Since the hypothesis of a chronological progression from Q to Luke prevails, the idea that many of the parables are literary creations of the late first century has become largely received. |

| 14 | Van Eck (2014) suggests that, in the parable of the Sower (Mk 4:1–9; Mt 13:1–9, Lk 8:4–8), the grains that fall on the path among the stones, or in the thorns, or yet are eaten by the birds, correspond to the various levies suffered by the Galilean farmer, with the portion that bears abundant fruit symbolizing the communal sharing of the untaxed harvest (see also Oakman 2012, p. 140). Similar to the vast majority of interpretations of the parables, and despite its statements of caution, this reading relies above all on the author’s creativity. |

| 15 | Their appearances in the gospels are frequent. Cf. in particular Lk 12:1–8; Mk 13:34–35. |

| 16 | A “Talent” (talanton, the unit chosen by Matthew) was approximately thirty years’ wages for a day laborer; a “Mine” (mna, Luke) was three months’ wages. Since Matthew always overstates the amounts of money in his stories, the Mine is probably the unit used in the original story. |

| 17 | The nobleman becomes a pretender to a throne, then a king; the story is thus inserted into Luke’s “meta-narrative” about Jesus’ destiny and status. |

| 18 | The expression “primitive narrative” does not mean, of course, that the parable was told only once. It refers to its theme, to the logic that conditions its development. |

| 19 | We were also presented with at least two counter-actions that are death-inducing: the killing of the son by the vinedressers is discontinuous/active; the hiding of seed money into a cloth is discontinuous/passive. |

References

- Alison, Dale. 2010. Constructing Jesus. Memory, Imagination, and History. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Janice C., and Stephen D. Moore. 1992. Mark & Method. New Approaches in Biblical Studies. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum, Shimon. 1977. Judaea as a Roman Province: The Countryside as a Political and Economic Factor. Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt 2: 355–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Kenneth E. 1983. Poet & Peasant and Through Peasant Eyes. A Literary—Cultural Approach to the Parables of Luke. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Warren C. 2016. A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus. Volume 5, Probing the Authenticity of the Parables by John P. Meier. Toronto Journal of Theology 32: 394–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, Thomas F. 1973. The Economies of Antiquity: Controls, Gifts and Trade. Lawrence: Coronado Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dinkler, Michal Beth. 2016. New Testament Rhetorical Narratology: An Invitation Toward Integration. Biblical Interpretation 24: 203–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, Charles Harold. 1935. The Parables of the Kingdom. London: Nisbet. [Google Scholar]

- Ferret, Carole. 2012. Vers une anthropologie de l’action. André-Georges Haudricourt et l’efficacité technique. L’Homme 202: 113–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferret, Carole. 2014. Towards an anthropology of action: From pastoral techniques to modes of action. Journal of Material Culture 19: 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiensy, David. 2007. Jesus the Galilean: Soundings in a First Century Life. Piscataway: Gorgias Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Martin. 1987. The Ruling Class of Judaea. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hägerland, Tobias. 2015. The Future of Criteria in Historical Jesus Research. Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus 13: 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, Kenneth C. 1997. The Galilean Fishing Economy and the Jesus Tradition. Biblical Theology Bulletin 27: 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, Kenneth C., and Douglas E. Oakman. 1998. Palestine in the Time of Jesus: Social Structures and Social Conflicts. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haudricourt, André-Georges. 1962. Domestication des animaux, culture des plantes et traitement d’autrui. L’Homme 2: 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haudricourt, André-Georges. 1964. Nature et culture dans la civilisation de l’igname: L’origine des clones et des clans. L’Homme 4: 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, Keith. 2002. Rome, Taxes, Rents and Trade. In The Ancient Economy. Edited by Walter Scheidel and Sitta Von Reden. Edinburg: Edinburg University Press, pp. 190–230. [Google Scholar]

- Jeremias, Joachim. 1963. The Parables of Jesus. New York: Charles Scribner’s Son. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Martin. 2007. Feast: Why Humans Share Food. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Käsermann, Ernst. 1969. New Testament Questions of Today. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, Chris. 2016. The Narratives of the Gospels and the Historical Jesus: Current Debates, Prior Debates and the Goal of Historical Jesus Research. Journal for the Study of the New Testament 38: 426–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kennedy, George A. 1984. New Testament Interpretation through Rhetorical Criticism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kloppenborg, John S. 2006. The Tenants in the Vineyard: Ideology, Economics, and Agrarian Conflict in Jewish Palestine. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Landé, Carl H. 1977. Introduction: The Dyadic Bases of Clientelism. In Friends, Followers, and Factions: A Reader in Political Clientelism. Edited by Steffen W. Schmidt, Laura Guasti, Carl H. Lande and James C. Scott. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. xiii–xxxvii. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, Edmund. 1969. Genesis as Myth and Other Essays. Lndon: Jonathan Cape. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, Edmund. 1983. Structuralist Interpretations of Biblical Myth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Amy-Jill. 2014. Short Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables of a Controversial Rabbi. New York: HarperOne. [Google Scholar]

- Malina, Bruce J. 1986. Christian Origins and Cultural Anthropology: Practical Models for Biblical Interpretation. Atlanta: John Knox. [Google Scholar]

- Malina, Bruce J. 1993. The New Testament World: Insights from Cultural Anthropology. Louisville: Westminster John Knox. First published 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Malina, Bruce J. 2002. The Social World of Jesus and the Gospels. Londres: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mauss, Marcel. 2016. The Gift. Translated by Jane L. Guyer. Chicago: Hau Books. First published 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, John P. 2016. A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol. 5: Probing the Authenticity of the Parables. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meynet, Roland. 2011. L’ Évangile de Luc. Pendé: Gabalda. [Google Scholar]

- Meynet, Roland. 2012. Treatise on Biblical Rhetoric. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Neyrey, Jerome H. 1998. Honor and Shame in the Gospel of Matthew. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neyrey, Jerome H., and Eric Steward, eds. 2008. The Social World of the New Testament: Insights and Models. Peabody: Hendrickson. [Google Scholar]

- Oakman, Douglas E. 2008. Jesus and the Peasants. Eugene: Cascade Books. [Google Scholar]

- Oakman, Douglas E. 2012. The Political Aims of Jesus: Peasant Politics in Herodian Galilee. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, Norman. 1967. Rediscovering the Teaching of Jesus. London: SCM. [Google Scholar]

- Pliny the Elder. 1856. Natural History. Translated by John Bostock, and Henry T. Riley. London: Henry G. Bohn, vol. IV. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads, David M., and Donald Michie. 1982. Mark as Story: An Introduction to the Narrative of a Gospel. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki, Marianne. 2000. Crossing Galilee: Architectures of Contact in the Occupied Land of Jesus. Harrisburg: Trinity Press International. [Google Scholar]

- Slingerland, Edward. 2003. Effortless Action. Wu-Wei as Conceptual Metaphor and Spiritual Ideal in Early China. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass, Klyne R. 2008. Stories with Intent: A Comprehensive Guide to the Parables of Jesus. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass, Klyne. 2017. Are the Parables Still the Bedrock of the Jesus Tradition? Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus 15: 131–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, Ernest. 2009. Interpreting the Parables of the Galilean Jesus: A Social-Scientific Approach. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 65: a308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, Ernest. 2014. The Harvest and the Kingdom: An Interpretation of the Sower (Mk 4:3b–8) as a Parable of Jesus the Galilean. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 70: a2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Hayden. 1973. Metahistory: The historical imagination in nineteenth-century Europe. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, Ruben. 2018. Memory and Jesus’ Parables. Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus 16: 156–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vermander, B. Jesus, the Anthropologist: Patterns of Emplotment and Modes of Action in the Parables. Religions 2022, 13, 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060480

Vermander B. Jesus, the Anthropologist: Patterns of Emplotment and Modes of Action in the Parables. Religions. 2022; 13(6):480. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060480

Chicago/Turabian StyleVermander, Benoît. 2022. "Jesus, the Anthropologist: Patterns of Emplotment and Modes of Action in the Parables" Religions 13, no. 6: 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060480

APA StyleVermander, B. (2022). Jesus, the Anthropologist: Patterns of Emplotment and Modes of Action in the Parables. Religions, 13(6), 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060480