Abstract

This article introduces and explores, for the first time in any Western language, the gilded-silver xiangnang 香囊 (spherical incense burner) from Famen Temple, one of the largest xiangnang incense burners found in the Tang dynasty. The spherical incense burner evolved from censers for bedclothes known as beizhong xianglu 被中香爐 (literally “perfume burner [to be placed] among the covers [of the bed], used as a warming device), which are chronicled as early as the Han dynasty in texts such as Xijing zaji 西京雜記 (Miscellaneous Records of the Western Capital). The silver spherical incense burner spread from China to the Islamic world and Venice, possibly influencing the development of the gyroscope for maritime navigation in Europe. This paper further examines the spherical incense burner’s relation to a device known as the Cardan Suspension (used to facilitate seafaring) and to the ritual of incense burning (imagined as a way to figuratively reach another world). It also discusses the spherical incense burner’s impact on similar objects from the Islamic world and Venice.

1. Introduction

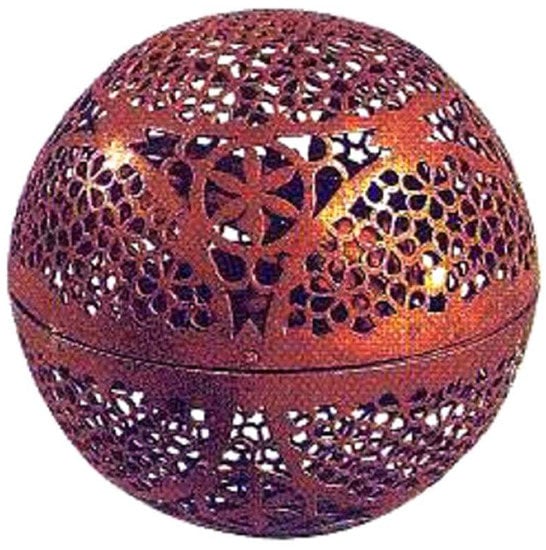

Fragrances are ephemeral and elusive scents meant to delight the senses; they are hardly replicable in a work of art, but their containers—in this case, incense burners—may be able to transport us back in time to recollect their fleeting aromas. In 1987, the excavation of Famensi, a Buddhist temple in the Famen town of the Tang Dynasty, unearthed two awe-inspiring, open-work, gilded-silver spherical incense burners with advanced gimbal systems that caught the attention of both art historians and historians of science. This type of spherical incense burner is not a stand-alone case; thirteen of them have been reported from the Tang period, eight of which are in China and three of which are in museums throughout the world, including the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Shang 2016, p. 54).

The Famensi double-bee, silver spherical censer (hereafter I will use “spherical censer” when referring to the spherical incense burner with a gimbal container), however, was one of the largest of its type found from the Tang dynasty, with a style of decoration and a gimbal system that originated from the type called beizhong xianglu 被中香爐 (literally “perfume burner [to be placed] among the covers [of the bed], used as a warming device), mentioned in Chinese texts as early as the Han dynasty (Figure 1). A Western Han source, Xijing zaji西京雜記 (Miscellaneous records of the Western Capital), a collection of 132 anecdotes pertaining to the Western Han dynasty,1 explains what the beizhong xianglu was used for:

However, Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide, does not list the Xijing zaji as a reliable source from antiquity.Ding Huan, a skilled craftsman from Chang’an, made an always-full lamp (changman deng). It had extraordinary decoration, sporting seven dragons and five phoenixes which were supported by lotus-shaped platforms resting on stalks. He also created an incense burner which lay on the bedclothes. It was also called the “censer amid the covers”. The technique is original from Fang Feng [a Han-dynasty skilled artisan], whose skills are unprecedented but now lost. It is not until Ding Huan that the technique is made possible again. To make it, Ding Huan fashioned [a series of] mechanically connected rings. The censer could roll in any direction, and yet the central incense-burning chamber could remain level. Thus, one could position it on the bed covers. This is how it acquired its name.2

Figure 1.

Liujin shuangfeng tuanhuawen loukong yin xiangnang鎏金雙蜂團花紋鏤孔銀香囊 (Gilt double-bee, cluster-pattern, openwork silver sachet) from Famensi. Gilded silver. Diameter: 12.8 cm. Weight: 547 g. Chain: 24.5 cm. Tang Dynasty (618–907).

In addition to the Tang dynasty Famensi censer, which has a chain, there was also a type that did not have a hook and chain and, therefore, might have been easier to set on or under the bedclothes. The description of the beizhong xianglu is even more akin to a larger, spherical censer that was made and collected in Japan and influenced by the Tang dynasty example. It is housed in the Shōsōin, a treasure house of the Tōdai-ji Temple in Nara, Japan, and is decorated with phoenix and lion patterns (Figure 2). When the xiangnang was introduced to Japan, it underwent significant transformation, becoming significantly larger in size (large enough to keep bedding warm) while maintaining its traditional design. As I will explain later, I assume that this large-scale incense burner might also have been utilized as a hand warmer in the winter.

Figure 2.

Silver incense burner. Horizontal diameter: 18 cm; vertical diameter: 18.8 cm; weight: 1550 g; upper diameter of foot: 9.6 cm; height of foot: 2.2 cm; overall height: 20 cm. Shōsōin, Tōdai-ji Temple, Nara, Japan.

Berthold Laufer (1874–1934), a German anthropologist and historical geographer with a specialization in East Asian languages, was among the first to write on the subject of the spherical censer in a 1916 article entitled “Cardan’s Suspension in China” (Laufer 1916). As implied by the title, the spherical censer was mostly addressed in the context of the history of science, specifically in relation to the Cardan suspension. Later, the historian and sinologist Joseph Needham made a significant addition to the topic in his chapter “Cardan Suspension” in volume four of his Science and Civilisation in China (1954) (Needham 1954, pp. 4.2: 228–36). The Cardan suspension, also known as a gimbal, is named after Gerolamo Cardano (1501–1576), an Italian polymath who described it in his 1550 book De subtilitate rerum but did not claim it as his own invention. A gimbal is a pivoting support that allows an object to rotate around an axis and maintain horizontal equilibrium with a seemingly simple combination of rings. Most people are acquainted with it because they have seen it in action in one of its most common Renaissance applications: the mounting of a mariner’s compass so that it is not affected by the motion of the ship. It is possible to preserve the original position of the center object even if the outer casing changes position. This may be accomplished by connecting three concentric rings in a series with pivots such that the axes of the pivots are alternately at right angles to one another (Needham 1954, pp. 4.2: 228–29).

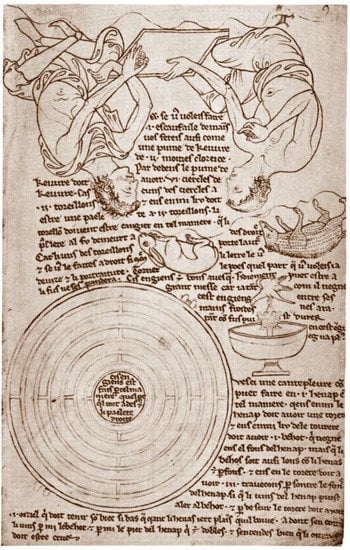

Although the gimbal system gained special prominence during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when it was first published by Cardan, it was already well-known in Europe long before Cardan’s time. The earliest known example of the gimbal device’s use in Europe is in a drawing found in the notebook of Villard de Honnecourt (a thirteenth-century artist from Picardy in northern France) in 1237 (Figure 3). The inscription on the page containing the drawing suggests that the figure with concentric circles on the left of the page is a hand warmer. The six concentric circles depict a gimbal’s rings, each with two pivots. The center is a brazier that is always upright since each ring bears the pivots of the others. The inscription says: “If you follow the instructions and the drawing, the coals will never drop out, no matter which way the brazier is turned” (de Honnecourt 1959, p. 66). This is a remarkably similar description to the Chinese bedclothes censer reported in the second-century Xijing zaji.

Figure 3.

The Cardan suspension in the notebook of Villard de Honnecourt, c. 1237.

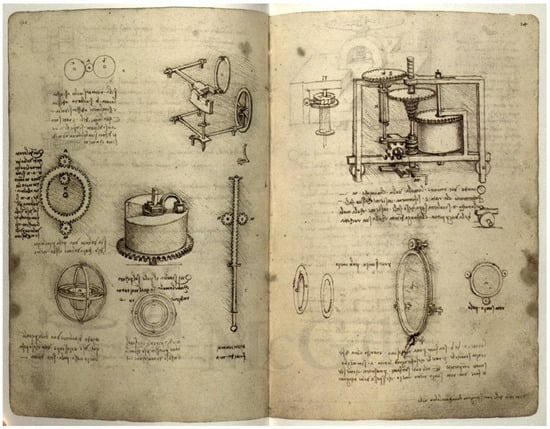

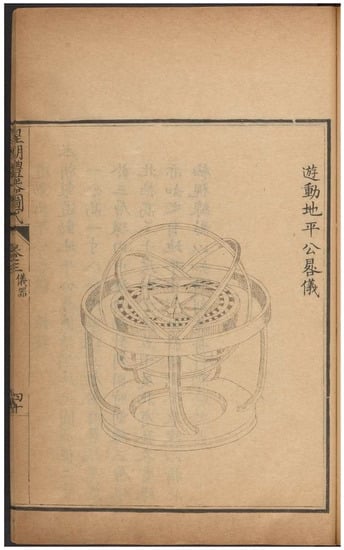

A gimbal was also sketched by Leonardo da Vinci around the year 1500, with the idea that it would be used as a gyrocompass (Figure 4). A gyrocompass is preferable to a magnetic compass when used in seafaring because it finds true north and is not impacted by the metal hull of the ship. The French inventor Jacques Besson (1540–1573) proposed in his 1567 book Le Cosmolabe that navigators take their observations while sitting inside large gimbals, allowing astronomical measurements to be taken from a steady position on board a ship. A drawing from the book (Figure 5) shows a gimballed chair in use. Needham also mentioned that during the seventeenth century, gimbals for ships’ compasses came into general use (Needham 1954, pp. 4.2: 228–29). A gimbal-mounted azimuth compass from eighteenth-century China is depicted in Huangchao liqi tushi皇朝禮器圖式 (The illustrated catalogue of imperial ritual instruments) (Figure 6). Next to the picture is an explanatory text mentioning that the gimbal-mounted azimuth compass system has been used in seafaring and time keeping as late as the Qianlong period (Yunlu 1759, p. 40).3

Figure 4.

Leonardo da Vinci, Codex Madrid I, Folio 13v. The gimbal in Leonardo’s drawings alludes to a mechanism used on ships to hold a mariner’s compass in place.

Figure 5.

Man seated in a gimballed chair aboard a ship, a drawing from Jacques Besson’s Le Cosmolabe, 1567, p. 29. Source: Gallica Ebooks.

Figure 6.

A Chinese, gimbal-mounted azimuth compass from Huangchao liqi tushi 皇朝禮器圖式 (The illustrated catalogue of imperial ritual instruments), vol. 3, p. 40. Published by Wuying dian 武英殿 in Qianlong’s reign (1759–1795). Harvard Yenching Library.

Needham realized that there is a Chinese narrative of the gimbal that dates to the second century CE, which is much earlier than anything related to this device that has been discovered in Europe. He went on to point out that even earlier than the beizhong xianglu account from Xijing zaji, Sima Xiangru司馬相如 (ca. 140 BCE) made reference to a jinza xunxiang 金鉔薰香 (the metal rings [containing the] burning perfume) in Meiren fu 美人赋 (Ode on beautiful women).4 This poem provided the setting for a couple of seduction episodes that were beautifully portrayed. In an empty palace or isolated imperial rest house, jinza xunxiang are among the furniture, hangings, bedclothes, and other such items that belong to the people who live there. In fact, the character za鉔 was created recent in history. Zhang Qiao’s章樵 annotated edition of Guwen Yuan古文苑 (The garden of ancient literature) mentions that za is xiangqiu, the censer can be rotated while the brazier will remain stable (Zhang 2009, p. 25).5 It was inferred that the jinza xunxiang was a device with a gimbal suspension just like the beizhong xianglu mentioned in Xijing zaji, meaning that it is conceivable that the invention belongs to the second century BCE rather than the second century CE. In other words, Needham believed that the Chinese were the first to invent the Cardan suspension system, which was later used in seafaring as early as the second century BCE (Needham 1954, pp. 4.2: 233–34).6

This article is the first comprehensive investigation of the spherical incense burner that originated in China. My research sheds fresh light on the subject by presenting new evidence from primary sources pertaining to the history of the spherical censer’s name; the ritual of incense burning as a means of reaching another world; and, for the first time, the history of the censer’s transmission to the Islamic world and Venice. This new research connects the Famensi censer to a broader and more connected global art history.

2. The Name and Function of the Spherical Incense Burner

Archaeologists referred to spherical incense burners as xiangqiu香毬 (perfume balls) until 1987, when they unearthed a stone stele named “yingcong chongzhensi sui zhenshen gongyang daoju ji enci jinyin qiwu baohan deng bing xin enci dao jinyin baoqi yiwuzhang”應從重真寺隨真身供養道具及恩賜金銀器物寶函等並新恩賜到金銀寶器衣物帳 (Inventory of veneration paraphernalia from the Chongzhen Monastery to accompany the True Body, imperially endowed gold- and silverware and treasure caskets, and gold and silver treasures newly given by the emperor, overseen by the commissioner for escorting the True Body), which inscribed words that further state there are two xiangnang weighing 15 liang 3 fen, or about 547 g. Thus, we know that the spherical incense burner of the Tang dynasty should be called a xiangnang. Although it has been given numerous names throughout Chinese history, I shall refer to it as a xiangnang.

The word xiangnang means “sachet,” and it is typically considered to be composed of cloth rather than metal. The discovery of the metalwork xiangnang thus resolves a perplexing mystery recounted in Tang Minghuang ku xiangnang 唐明皇哭香囊 (Tang Minghuang weeps over the sachet bag): when Emperor Xuanzong唐玄宗ordered to have uncovered the tomb of his famous and favorite imperial consort Yang Guifei楊貴妃, he discovers that Yang Guifei’s body has decayed, whereas the xiangnang buried with her was still in good condition, and it was presented to the emperor as a grievous memento. The xiangnang have long been understood as being made of silk, so one might wonder how Yang Guifei’s sachet could still have been intact. After the discovery of the metal xiangnang, however, its condition makes good sense.7

The xiangnang had two fundamental functions in the Tang Dynasty: it was primarily used as an incense burner, and secondarily as a hand warmer, which may also have been used in bed as both a warming device and an aromatherapy treatment. Bai Juyi白居易 (772–846), a prominent Tang-dynasty poet, mentions the term nuanshou xiaoxiangnang, 暖手小香囊which literally translates as “hand warming with a small xiangnang”.

A Tang monk and lexicographer, Huilin慧琳 (737–820), mentioned in Yiqiejing yinyi一切經音義 (Pronunciation and meaning in the complete Buddhist canon), written between 783 and 807, that xiangnang were not only made of silver but also of bronze, and were generally used by upper-class women such as the emperor’s consorts (Huilin 2009, p. 97).8

Although the metal spherical incense burner with a brazier and gimbal mechanism in its interior was known as a xiangnang during the Tang dynasty, there was no official name for it prior to that time; although earlier, during the Han dynasty, there was a somewhat similar device known as beizhong xianglu. However, a xianglu is usually larger than a xiangnang and usually does not feature a gimbal mechanism unless referred to as beizhong xianglu. Following the Tang dynasty, during the Song dynasty, this type of “smart” spherical gimbal incense apparatus was commonly referred to as xiangqiu, and it was typically larger in size.

Tang liudian 唐六典 (The six statutes of the Tang dynasty), which was compiled in 738, mentioned xianglu and xiangnang concurrently when recounting an occurrence in Hanshu tianwen zhi 汉书天文志 (The book of Han astronomy treatise) when Princess Guantao (Guantao gongzhu馆陶公主), the older sister of Emperor Ming of Han, asked the emperor for a position for her son. However, the emperor instead preferred to reward the young man with the equivalent of USD 10 million. “There is a constellation called Lang in the sky,” Emperor Ming of Han told his ministers, “and this official position corresponds to this constellation in the sky, and is therefore exceedingly important. If you accept this formal post, you will be responsible for managing a one-hundred-mile radius, which is a huge responsibility. If the wrong person is used, the people who live there will suffer greatly. As a result, I would rather give her son money than offer him a place in government”. The book then goes on to describe the numerous and sumptuous privileges that come with holding the government position known as the shanghshu lang 尚书郎 (royal secretariat). For example, when the shangshu lang was on night duty, he would be given opulent bedding and bed-curtains as well as food and fruits. Every five days, he would be fed delicacies rivaled only by those eaten by the emperor himself. To alleviate the loneliness and monotony of the night shift, the government appointed two handsome men and two beautiful ladies to look after him. The two ladies would enter the chamber while holding incense burners, a xianglu and a xiangnang, to prepare his bed and night attire.9 This detailed description of the benefits of the shangshu lang position, however, does not appear in the original copy of the Hanshu. Thus, this tale is a Tang-dynasty reinterpretation of what it meant to live luxuriously in the Han dynasty, one aspect of which was unquestionably the possession and use of the xiangnang.

In the Song-dynasty book Chenshi xiangpu陳氏香譜 (Chen family aromatic treatise), there is an entry citing Xijing zaji’s beizhong xianglu, and a comment about this item stating that it is “today’s” [the Song dynasty’s] xiangqiu. With this in mind, when I am referring to the spherical incense burners from the Song and subsequent dynasties, I shall refer to them as xiangqiu.

Although the spherical incense burner shown in Figure 1 would have been referred to as a xiangqiu after the Tang dynasty, during that dynasty the word had a different meaning. Several pieces of evidence suggest that a xiangqiu was a type of ball used in a drinking game popular at that time called paoda ling拋打令, where guests would sit in a circle and pass balls around while entertainers would play music and dance. When the music stopped, whoever had the ball had to take a drink. Zhang Hu 張祜 (791?–852), in his poem Pei Fan Xuancheng beilou yeyan陪范宣城北樓夜宴 (Joining the night banquet with Fan Xuancheng on Beilou), described a luxurious official banquet serviced by guanji 官妓 (literally, “official prostitute,” a government-assigned profession whose members provided entertainment and sex to government officials), who dressed up and passed a xiangqiu (a ball) to the guests with a flirtatious look.10

The sole time during the Tang dynasty that the word xiangqiu was used to refer to the spherical censer is in a poem titled Xiangqiu by the Tang poet Yuan Zhen元稹 (779–831). The poem was published in Yuanshi changqing ji元氏長慶集 (Collected works of Mr. Yuan of the Changqing era), the original Tang version of which was lost; what we have today is a Song-dynasty version with the title possibly given by a Song scholar who calls the spherical incense burner a xiangqiu.

Notably, multiple accounts in Song Shi宋史 (History of the Song dynasty), which records the history of the Song dynasty, documented the use of xiangqiu in the palace hall where the emperor received his audience.11 Xuanhe yishi 宣和遺事 (Remnant affairs of the Xuanhe reign) further supplements the story where, during the fifth year of Xuanhe, on July 1 of the lunar calendar, officials are waiting for the emperor at the audience hall. Shortly thereafter, the xiangqiu turns and the curtain rolls open.12 In other words, the xiangqiu was hung on the audience hall’s curtain while the emperor was receiving audience. In another anecdote about the crown prince’s official palace, Song Shi describes a situation in which a servant is holding a gold xiangqiu in his or her hands.13

During the Ming dynasty, the gimbal in the xiangqiu is compared to an armillary sphere, which is a representation of celestial objects consisting of a spherical framework of rings, centered on the earth or the sun, that depict lines of celestial longitude and latitude as well as other astronomically essential characteristics such as the ecliptic. The armillary sphere was created in ancient China and later used in the Islamic world and medieval Europe. In Tian Yiheng’s田藝蘅 Liuqing ri zha留青日札 (Daily jottings of Liuqing), he wrote:

Tian Yiheng was the first person to notice the connection between xiangqiu and the armilary sphere. His Liuqing entry was also recognized by Joseph Needham (Needham 1954, p. 4.2: 235, note b).Today’s gilded spherical incense burners are like an armillary sphere, in which three layers of mechanical rings are well-balanced in lightness and weight, and move without being stopped. Even when put under a quilt, the fire in the incense burner will not die. Its façade is decorated with flowers and the smoke can come out from all directions. It is a really elegant treasure of the boudoir.14

Apart from the xiangqiu’s function as an incense burner and hand warmer, it can also repel insects when used with the correct type of incense, as mentioned in a poem by the Ming-dynasty painter Xu Wei徐渭 (1521–1593).15 In the famous late Ming novel Jin Ping Mei 金瓶梅 (The Plum in the Golden Vase), a xiangqiu was mentioned several times. In chapter 21, for example, it says that Jinlian金蓮, one of the novel’s central female protagonist, stuck her hands under a quilt and discovered a silver xiangqiu for fumigating the bedclothes, and then exclaimed, “Sister Li has laid an egg!”16 This shows that xiangqiu were still utilized in the same way as beizhong xianglu were in the Han dynasty—tucked under the bedclothes.

A silver xiangqiu is referenced for the second time in chapter 58 of Jin Ping Mei, where it was determined by Li Ping’er to weigh 15 liang, which equals 559.5 g, comparable to the Famensi xiangnang, which weighs 547 g. The Famensi xiangnang is a bit lighter and thus smaller in diameter, measuring around 12.8 cm. Today, we can find a 13.3 cm Ming-period xiangqiu (Figure 7) in the National Museum of China, which is most likely the same kind as the one described in Jin Ping Mei.

Figure 7.

Spherical Censer. Ming dynasty, bronze. Height: 12.8 cm; diameter: 13.3 cm. National Museum of China.

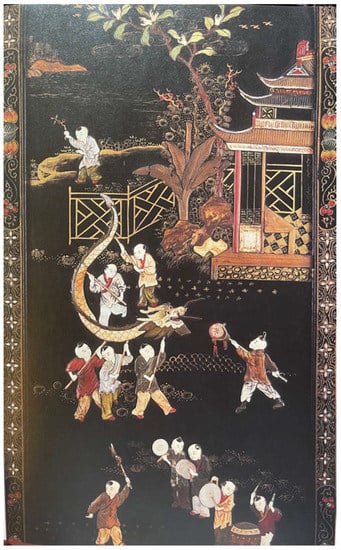

In addition to the xiangnang and xiangqiu, Needham mentioned gun deng滾燈 (rolling lamps, also called globe-lamps), which have a gimbal system that is comparable to the xiangnang’s in terms of mechanics. They are generally made of bamboo, with bamboo gimbals inside the globe that maintain the light’s steadiness. Figure 8 shows a detail of a lacquer screen depicting a child holding a rolling lamp, which is flourishing in front of a dragon in the procession (Needham 1954, p. 4.2: 231). Needham noted a source from Xihu zhi 西湖志 (Topography of the West Lake region of Hangzhou) that mentions in one of its supplements that guan li 關棙 (interlocking pivots) were mounted on certain occasions within paper lanterns and that “these were then kicked and rolled along the streets without the lamps inside being extinguished” (Needham 1954, p. 4.2: 235).

Figure 8.

Children taking part in a dragon parade, part of an inlaid lacquer screen in the collection of Dr. Lu Guizhen 魯桂珍 (1904–1991), a co-author of Joseph Needham’s Science and Civilisation in China and the second wife of Needham.

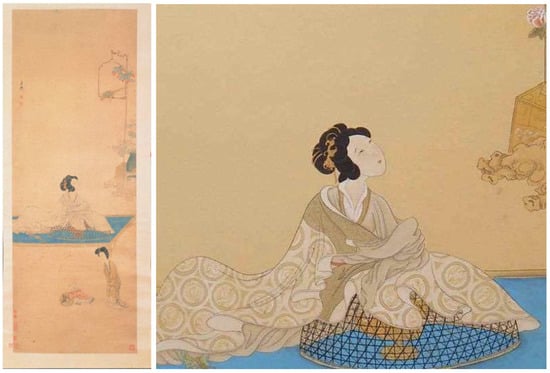

Needham also mentioned that certain old names, such as xun long 熏籠 (perfume basket) might also refer to the xiangnang (Needham 1954, p. 4.2: 235). In this particular instance I disagree, since the xun long is often woven from bamboo pieces and shaped like an open-work bamboo cage. Figure 9 shows a painting by Chen Hongshou陳洪綬 (1598–1652) that pictures a xun long.

Figure 9.

Left: Painting by Chen Hongshou 陳洪綬 depicting women using a xun long 熏籠 (perfume basket), damask silk, 129.6 × 47.3 cm. Shanghai Museum. Right: Detail of the painting.

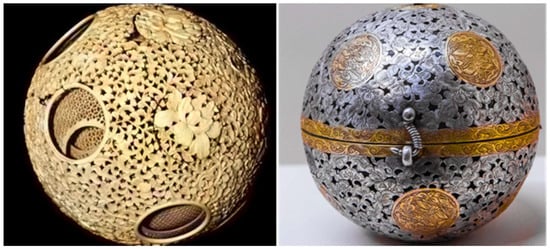

Needham also associated the production of xiangnang with the production of guigong qiu 鬼工球 (turned ivory balls) during the Song period. He pointed out that the turned ivory balls and the spherical incense burners are similar in that both are formed into a round shape using a lathe. I disagree with Needham’s dating, as in reality, the earliest known tangible evidence of concentric ivory spheres produced on a lathe dates no earlier than the seventeenth century. I find that the gilded-silver xiangnang from Famensi is reminiscent in its design of an eighteenth-century turned ivory ball with a floral, open-work pattern that was imported to Poland from China and is housed today in the Wilanow Palace Museum (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Left: Turned ivory ball imported to Poland from China in the late 18th century. Wilanow Palace Museum, Warsaw, Poland. Right: xiangnang from Famensi. Gilded silver. Diameter: 12.8 cm; weight: 547 g. Tang Dynasty (618–907).

It was necessary for incense burners to be of superior quality, due to the inherent value of incense itself. Many steps were necessary to create the ornate spherical incense burners of the Tang dynasty, including chasing and hammering, carving and hollowing, turning on a lathe, and gilding, among others. Hammering transforms gold and silver into very thin sheets of metal while also enhancing the sheen of the metal’s surface. Hollowing entails punching a hole in the material and then carving off the pieces using a thin saw. The Sassanian goldsmiths of Persia introduced these methods to Chinese craftsmen. Using the Silk Road, the Persian Sogdians brought the sophisticated metal workmanship of West and Central Asia to China, where it was much appreciated. Although textual evidence indicates that this form of incense burner was invented during the Han dynasty, its type of inlay and metalwork is unique to the Tang dynasty, following the cultural exchange with the Persian Sogdians in China. In other words, the beizhong xianglu from the Han dynasty may have differed slightly from the ones from the Tang era, although no one has ever seen one from the Han dynasty.

The workmanship of gold and silver sachets had already reached maturity during the Tang Dynasty, thanks to the development of increasingly skilled local craftsmanship. In particular, there was a group of artisans in the royal gold-and-silver workshops, the wensi yuan文思院, who worked on various imperial projects. Their craft was facilitated by China’s abundant supply of natural gold and silver and the well-developed gold-and-silver-mining industry operated by the Tang government, which even permitted private mining for a period of time.17 The abundance of gold and silver and the maturity of their workmanship made it feasible to create the xiangnang that we see today in Famensi.

3. The Power of Incense

The Sanskrit word for incense is gandha, which has a broader meaning than the Chinese word used for the same, xiang 香 (which can mean “fragrant,” “aromatic,” “perfume,” or “incense”), and refers to anything that can be smelled with the nose. Later, the term gandha was employed to imply “related to Buddha”. A gandhakuti (house of incense) was a temple, and the gods of smell and melody (gandharvas) dwelt on gandhamadana (incense mountain) (Bedini 1994, pp. 43–44). The Chinese character for incense (xiang 香) is written with two semantic components, according to Chinese philology. Grain (he 禾) is the top element, while sweet (gan 甘) is the lower. Its original meaning was “pleasant odor of grains”. Food, primarily grain, was placed in ritual bronze vessels such as ding鼎 and gui簋during ceremonies and offerings for ancestral tombs during the Shang Dynasty (c.1600BCE–c.1046 BCE) and Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046 BCE–256 BCE), with the primary objective of feeding the ancestors’ souls through the pleasant smell of the meal. Around 200 CE, when Indian Buddhists imported sandalwood incense to China, this character was used to name it (Habkirk and Chang 2017, p. 160). Following the introduction of Buddhism to China from Southeast Asia via Turkestan during the Han period, foreign aromatic herbs imported from overseas expanded the Chinese people’s knowledge and use of incense. In ancient Chinese rites, incense was not used to offer sacrifices. It was only after Buddhism arrived in China from India during the Han dynasty (about 150 CE) that it was used, and it continued to be used after the rise of Daoism. The central element of the Daoist ceremony is the incense burner on the altar. The furnace master (lu zhu爐主), who is selected yearly by lottery, and his helpers begin each liturgy with the lighting of the incense burner (fa lu 發爐). Since the fifth century, the rite has not changed. Due to the fact that Daoist incense was originally used for shamanic purposes as well as religious offerings to the gods, it is possible that the old Daoist incense produced hallucinogenic smoke (Bedini 1994, pp. 43–44).

Incense was traditionally believed to facilitate communication between humans, gods, and ghosts. During the Han dynasty, when the belief in immortals was prevalent, the practice of incense burning became popular. At this time, the introduction of new aromatics, which were brought into the empire by Emperor Wu of Han (157–87 BCE) as a result of significant trade connections established outside the empire, resulted in the creation of a vessel for burning them—the incense burner—which was used in an attempt to establish a connection with the immortals with the goal of living forever (Bedini 1994, pp. 27–28). The purpose of burning incense was to please the gods by allowing them to enjoy the fragrant scent. Incense possessed no magical power until it was burned; only incense fire (xianghuo 香火) and incense ash were considered to have magical power, assisted by an agent and by the participation of spirits. Burning incense was regarded as feeding food to the deities’ spirits, “an outcome of a historical transformation in Chinese religious offerings and cosmology”.18 If incense burning was considered providing food for the gods, then the incense burner became the bowl that held the food. Thus, incense ash and incense burners also became sacred relics and artifacts, which believers cherished and worshipped (Zhang 2006).

Buddhists consider incense particularly significant, believing that it has a direct effect on people’s bodies and minds and can reflect wisdom and virtue. As a result, a sage who has practiced Buddhist teachings successfully can even exude a unique fragrance. The Vimalakirti Sutra records a pure land of incense, describing it as a “fragrant land” 香積國土 where incense is not only used to create everything, such as clothes and dwellings, but is also used to enhance the teachings. It is also written in the Avatamsaka Sutra that the lotus world (huazang shijie華藏世界) is surrounded by countless seas of perfume, another allusion to incense.

Incense has long been linked with the worlds of superstition and magic. In the Tang dynasty sutra Dafo ding rulai mi yin xiu zhengliao yi zhu pusa wanxiang shoulengyan jing 大佛頂如來密因修證了義諸菩薩萬行首楞嚴經 (The Sūtra on the Śūraṅgama Mantra that is spoken from above the Crown of the Great Buddha’s Head and on the Hidden Basis of the Tathagata’s Myriad Bodhisattva Practices that lead to their Verifications of Ultimate Truth), usually abbreviated as Lengyan jing 楞嚴經,19 xiangnang was suggested as a method of storing a spell and protecting the user from all toxins in life,

if all sentient beings in all the lands of the ten worlds write this mantra with birch bark, shell leaves, plain paper, and white cloth that grow in their lands. Put it in a xiangnang, even if the person has a faint memory and he cannot recite it. As long as the person carries it on his body or writes it in his house, he should know that all kinds of poison will not harm him throughout his life.20

The haze created by burning incense is in keeping with the ambiance created by the gods themselves and is a material expression of the belief that the immaterial realm of Chinese spirits can be made physical and accessible to the general public. If a person wishes to worship and pray to the gods, he must burn incense. The gods will know if the smoke of the incense rises into the sky. In the opposite way, incense can also be used to convey the will of the gods to humans, making it a useful divination tool.

During the Sui and Tang dynasties, incense rituals were also incorporated into political life, where incense was used to signify solemnity on important occasions such as the revealing of civil exam ranks, sacrifice rituals, and the emperor’s morning audience. China’s strong power and its established land-and-sea transportation also facilitated the circulation of incense within the country as well as its importation from outside. By the Tang dynasty, incense had become an ingrained component of both secular and religious life, particularly among the aristocracy. It was widely included in love potions and lovemaking as well as used by both sexes of the higher classes for toiletries and for perfuming their houses, workplaces, and temples (Bedini 1994, p. 29). Several types of incense-burning commodities were invented during the Tang dynasty, such as incense pills, incense cake, and incense powder, many of which, in common with incense itself, do not release their fragrance until they are burned with charcoal. It was in this context that the Tang dynasty saw the widespread use of spherical censers among the gentry. Sui and Tang dynasties developed lightweight wearable spherical incense burners, such as the xiangnang. The xiangnang could also be hung indoors or placed in the bedroom to keep quilts warm, and they continue to be utilized in China through the Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties (Fu 2008, p. 68).

4. The Spread of Xiangnang to the Islamic World and Venice

The xiangnang spread to the Islamic world in the late twelfth century and was most frequently found in Egypt and Syria during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries—during the Mamluk period (1250–1517) in the Islamic world, which corresponds to the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) in China. Before the twelfth or thirteenth century, there is no conclusive evidence that people in Europe or the Islamic world were aware of the gimbal-powered, spherical incense burner invented in China (Ward 1990–1991, p. 74). Therefore, despite the fact that this censer was invented at least as early as sometime during the Tang dynasty (based on material evidence), I believe it was introduced to the Islamic world only during the Mongol Yuan dynasty. Why this exchange did not occur earlier is unknown; perhaps the conditions were not right for it until sometime during the Yuan.21

Despite the war and the deaths brought to the Islamic world by the arrival of the Mongol tribal confederation in the thirteenth century, the new Mongol dynasty, the Ilkhanate (ruled 1256–1335), quickly created conditions for the recovery of intellectual activities by encouraging exchange with their Chinese overlords, the Great Khans. This culminated in the historical period known as Pax Mongolica, Latin for “Mongol Peace,” which enabled communication and trade during the massive Mongol conquests by removing a plethora of tolls and other exactions and eliminating competing predators (Jackson 2018, p. 210). Notwithstanding the Mongols’ animosity for the Mamluks (who controlled Egypt and Syria from 1260 to 1517 and ultimately conquered the Crusaders), academic interactions between Egypt, Syria, Iran, Iraq, and Anatolia flourished throughout this time period, not only through the physical transfer of written texts and objects but also on a personal level (Brentjes 2018, p. 24). The development of the manufacture of metal objects with inlay that made the reputation of Damascus’ craftsmanship and more widely that of Syria and Egypt at the end of the Middle Ages is essentially due to craftsmen coming from Upper Mesopotamia and, in particular, from the city of Mosul. Faced with the Mongols, they emigrated to Damascus during the Ayyubid period, and then to Egypt under the Mamluks (Raby 2012).

Spherical censers became more common in the fifteenth century, when Egyptian and Syrian metalsmiths of the Mamluk dynasty introduced the Saracenic-style spherical incense burner (influenced by Chinese) to Venice and created a much larger group of Mamluk metalwork objects in a style known as “Veneto-Saracenic,” which were intended for export to Europe and display a mixture of Middle-Eastern and European stylistic elements. The influence of the Middle East can be seen in these objects in their inlay techniques as well as their ornate arabesques and pseudo-Arabic lettering. The European influence appears in the shields and sometimes the coats of arms that are etched into their surfaces (Ward 1990–1991, p. 76). The trading climate helped popularize the Veneto-Saracenic style: despite repeated papal injunctions, the Venetian Republic negotiated successive trading deals with Mamluk Egypt, and Florence followed suit (Auld 2007).

The Egyptian sultan established commercial centers (fondachi) at Alexandria and Damietta and subsequently in Cairo, as well as in Aleppo and Damascus, to facilitate trade with these cities. Similar to those who undertook the Grand Tours of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Europe, young men from the most prominent Venetian families were sent to the Levantine towns not only to study in preparation for their professions, but also as a last step in their preparation for life. As a result, despite their alleged isolation from the local populations, Europeans began to appreciate—and to purchase—Muslim items in large numbers (Auld 2007).

For example, Lorenzo de’ Medici’s (1449–1492) inventory of 1492 shows fifty-seven items classified as domaschini and approximately fifty more alla domaschina—words that may allude to divergent origins, such as Italian imitations—with a total value of more than 967 gold florins. It is noteworthy that the spherical incense burners are worth a significant amount more than the typical inlaid brassware, which is valued at around 10 florins on average. Depending on the size, a spherical incense burner might cost up to 34 florins (Mack 2001, p. 144). Two of the spherical censers in the Veneto-Saracenic style (both in the Bargello Museum) also belonged to the Medici family during the time of Cosimo I (1519–1574) and are “listed in an inventory of 1553 as ‘profumieri damasceni’“ (Contadini 2006, p. 309). The spherical censers might be connected to an embassy sent by the Sultan of Egypt to Lorenzo the Magnificent in 1487, which included gifts among its offerings: “a large amount of balsam … big porcelain vases that have never been seen before or that have been better crafted … big containers of sweetmeats, myrabolan and ginger”.22

In spite of the fact that Islamic culture does not regard incense in the same way that Buddhism does—incense never became an essential part of Islamic ritual—it was still widely used in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age (the eighth to the fourteenth century), when it was reserved for special occasions such as weddings and circumcisions and was used in special places such as mosques and shrines (Ward 1990–1991, p. 67). While the majority of Chinese spherical incense burners are made of silver, most of the Islamic examples are made of bronze, most likely owing to the large amounts of copper (a component of bronze) that were being transported from Europe to Islamic countries from the fifteenth century onward (La Niece 2010, p. 35).

Many museums, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum in London, and the Bargello Museum in Florence, now collect spherical incense burners made in the Islamic world, cataloging them variously as either hand warmers or incense burners. Scholars have debated the Islamic spherical censer’s function. Ward noted that the evidence for their employment as handwarmers comes from European sources, which mention them being used on church altars to warm priests’ hands during Mass (Ward 1990–1991, p. 78). I propose that they could have functioned as both hand warmers and incense burners, as they did in China, for incense plays an important role in Christian ritual. It was never only clergy who made use of the spheres as hand warmers; inventories of court treasuries contain references, although uncommon, to spherical objects made of precious metals that were used to warm the hands of members of the lay community as well. In some cases, it is probable that the use of the sphere to generate heat in Europe was a by-product of its earlier use as an incense burner (Auld 2004, p. 112).

Apart from the discussion about how the censers were utilized, there is also the issue of what was used to fill them. Rachel Ward suggests tentatively that the spherical censer would have contained perfumed candles (Ward 1990–1991, p. 80). That is unlikely, however, since candle wax, when heated, becomes liquid, and even with the presence of the gimbal in these incense burners, there was no guarantee that the liquid wax would not spill out. Furthermore, when candle wax is allowed to cool to room temperature, it becomes extremely difficult to clean from surfaces. Ward also cites the example of Chinese globe lamps (rolling lamps) to back up her case: “globes like these, with oil lamps set in the gimbals, are known to have been used as lighting devices. ‘Globe lamps’ are referred to in Chinese texts as early as the twelfth century” (Ward 1990–1991, p. 81). But globe lamps differ from the spherical incense burners in that they are much bigger and not made of metal, and they do not require the removal of the wax after their use. Furthermore, if Ward had read the Chinese original, she would have known that Chinese spherical incense burners used charcoal rather than wax. My guess is that incense wood or other aromatic substances would be placed on top of the charcoal to impart a pleasing aroma. Likewise, Villard de Honnecourt, in his description of a gimbal hand warmer (see Figure 4), also notes that the “coals” will never drop out, no matter which way the brazier is turned. Another piece of evidence against Ward’s argument is that the spherical incense burner was later referred to as a xunqiu; the term xun means “to smoke,” implying that charcoal, rather than wax, was used. In the archaeological field, there is still a great deal of uncertainty surrounding the study of early incense. It is difficult to establish with confidence what type of incense was burned in the Han Dynasty’s spherical incense burners, and it is prudent not to speculate. Perhaps hot charcoal ashes are pressed, and pieces of incense wood (combined with other aromatic substances) are baked on top of the charcoal to exude scent, like the Japanese Kōdō (香道, “Way of Fragrance”) are performed, a method that may have originated in 6th century China when Buddhism arrived during the Asuka period. The same period that the Chinese spherical incense burner found its way to Japan. Likewise, Christian church incense burners such as a thurible, smoke out the scent by placing incense on top of the charcoal. The metal censer is filled with burning charcoal, either straight into the bowl section or into a removable crucible if given, and incense (which comes in a variety of kinds) is placed on top of the charcoal, where it melts and produces a sweet-smelling smoke.

Except for a handful of spherical incense burners that carry the signatures of two Muslim metalsmith masters, Zain al-din and Mahmud al-Kurdi (a fifteenth-century Kurdish artist), the majority of these objects are unsigned. In the sixteenth century, Venetian artists copied Mamluk open-work spherical censers, which were supposed to have been manufactured for sale to European towns with colder climates. The style and ornamentation of the Venetian pieces are very comparable to those of the Mamluk examples. Some scholars argue that they were created by Muslim artists who immigrated to Venice in about 1500, notably Zayn al-Din and Mahmud al-Kurdi (Atil et al. 1985, pp. 172–73). Others, however, have questioned the idea that Muslim artists ever worked in Venice. In 1972, Hans Huth claimed that the Venetian guild system was so rigorous that Muslim immigrants would not have been allowed to work within it, implying that Muslim artists created their works in their native countries and then sold them in Europe (Auld 2007). There is also no archival evidence in Venice to suggest the existence of a group of Muslim immigrant metalsmiths of this nature (Ward et al. 1995, p. 243).

The British Museum has one of the earliest and finest silver-inlaid spherical incense burners from the Mamluk period (Figure 11), which was constructed in 1270 for Badr al-Din Baysari (d. 1298), a Syrian amir (prince). It is, without a doubt, one of the most arresting of these objects made in the Veneto-Saracenic style. It is far larger than Chinese spherical censers of the Tang period, with a diameter of 18.4 cm (7 1/4 inches), but almost equal in size to the Japanese example from the same era (see Figure 3). It appears that as the Chinese spherical censer spread throughout the world, its size grew in proportion. Two Mamluk sultans, Baybars (ruled 1260–77) and Baraka Khan (ruled 1277–79), are mentioned in the titular inscriptions, which implies that it dates from the reign of the latter sultan, Baraka Khan. Due to the fact that Baysari was based in Damascus for the most of his professional life, including these years, it is most likely that this piece was created in Damascus between 1277 and 1279 (Ward 1990–1991, p. 75).

Figure 11.

Brass incense burner. Made in Damascus. Diameter: 18.4 cm; height: 18.5 cm. British Museum.

5. Conclusions

This article tells the fascinating story of how the technology of a spherical incense burner with a gimbal system made its way from China to the Islamic world and subsequently to Venice, where it may have had an impact on the creation of the Cardan suspension system and contributed to seafaring, to maritime exploration, and to the development of a connected global history.

The Chinese spherical censer is likewise the product of a long and intertwined global art history. The metalwork utilized in the Tang dynasty censer is a consequence of the chasing and hammering techniques taught to the Chinese by the Sassanian goldsmiths of Persia, while the culture of burning incense is from Indian Buddhism. In Buddhism, the burning of incense carried one’s petitions to the gods; incense was also the messenger of sincere yearning, bringing Buddha’s compassion to the supplicant via its smoke (Bedini 1994, p. 26). It is believed that the smoke from the incense, in the course of sacrificial ceremonies, acts as a channel for conjuring up imaginary realms and as a gateway to a universe that is typically unavailable to humans (Milburn 2016). Incense burners were intricately constructed using costly metals in part because of the ceremonial significance associated with incense burning.

The history of the use of incense is steeped in a wealth of observable tradition, yet its nuanced fragrance is impossible to capture in a work of art. However, examining the incense burners that disseminate those fragrances can often lead to significant discoveries. This article has traced the nomenclature of the spherical incense burner, discussing references to it as both a xiangnang and a xiangqiu. These names are significant because they reveal the function of the object while also reflecting a rich history of how it has been understood. Based on tangible evidence, the spherical incense burners that became widespread in the Tang dynasty were not only used for the ritual of incense burning; when they made their way to the Islamic world under the Mongol Yuan dynasty, they also contributed to the Pax Mongolica, an era of booming trade and exchange, and eventually led to significant advancements in the gyroscope and, as a result, in seafaring, because of the gimbal technology employed in their construction. Whether the Cardan suspension, which helped in maritime exploration, was influenced by the fact that China brought the spherical censer to the Islamic world and ultimately to Venice is a question that deserves to be pondered.

The gimbals of the mariner’s compass are the most well-known implementation of the Cardan suspension system. The gyrocompass was destined to replace the magnetic compass. Ferromagnetic metals (such as iron, steel, cobalt, nickel, and other alloys) in a ship’s hull have no effect on the gyrocompass’s readings or accuracy. As a result, the gyrocompass, which is now widely used on steel ships and airplanes and shows true north rather than magnetic north, was developed. Gyroscopic stabilizers are used in ships and, more specifically, airplanes, where the “automatic pilot” has shown to be the most important component in the successful completion of long-distance and bad-weather flying missions (Needham 1954, pp. 4.2: 235–36). Nowadays, gyroscopes are most often used in automobile transmission shafts and in camera gimbals, where they work to stabilize video and pictures. This research reminds us that the origins of such an important piece of equipment may be traced back to spherical incense burners from the Tang dynasty, whose initial purpose was to burn incense, warm the hands, and pleasure the senses.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I sincerely thank Eugene Wang, Huaiyu Chen, Jinhua Chen, Yukio Lippit, Guan Liu, and this journal’s anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | David Knechtges and Taiping Chang note that “throughout its history, it [Xijing zaji] has been identified with five different authors or compilers: (1) Liu Xin 劉歆 (d. 23), (2) Ge Hong 葛洪 (283–363), (3) Wu Jun 吳均 (469–520), (4) Xiao Ben 蕭賁 (d. 549), and anonymous”(Knechtges and Chang 2010, p. 3: 1648). William Nienhauser, author of a large dictionary of Chinese literature, who also determined that the Xijing zaji is a compilation dating from around 500 AD, much of it copied from earlier sources. see (Nienhauser 1978). |

| 2 | Original: “長安巧工丁緩者,為常滿燈,七龍五鳳,雜以芙蓉蓮藕之奇. 又作臥褥香爐,一名被中香爐. 本出房風,其法後絕,至緩始更為之. 設機環轉,運四周而爐體常平,可置之被褥中,故以為名”. (Liu 2009, p. 4) |

| 3 | Original: “謹按, 本朝制遊動地平公晷儀, 鑄銅為之. 圓座徑二寸一分, 高一寸八分. 內遊環三層, 系日晷地平盤於三層環內, 中施指南針, 周圍時刻線三層, 依北極高三十度, 四十度, 五十度. 北有弧表, 畫線亦如之. 自地平中心出斜線對弧表線, 以指北極, 視線影以知時刻. 為舟行測驗之器”. |

| 4 | While some scholars believe that Meiren Fu was written by Sima Xiangru, others believe it was composed during the Qi or Liang dynasties and that it was not authored by Sima Xiangru. |

| 5 | Original: “鉔,音匝.香毬袵席間可旋轉者.西京雜記長安巧工丁緩,作被中香爐, 爲機環轉運四周, 而爐體常平”. |

| 6 | However, Zhang Baichan and Tian Miao argue that the theory of Needham’s global history of science, which highlights the spread of knowledge across cultures, is incorrect. They believe that in numerous situations, his “anticipations” and “disseminations” are flawed. Despite Needham’s assumption that Jinza xunxiang in Meiren Fu was a gimbal suspension, there were no explicit descriptions of this mechanism in Meiren Fu. See (Zhang and Tian 2019, p. 622). |

| 7 | Shang Gang尚刚disagrees with this theory, arguing that it could be a fabric xiangnang香囊 with gold thread. This is one speculation, but Shang Gang’s theory cannot preclude the possibility of a metal xiangnang. Moreover, the fact that the xiangnang was intact in comparison with the flesh of Yang Guifei’s body more likely means that she used a metal one. See (Shang 2016, pp. 54–57). |

| 8 | Original: “燒香器物也,以銅鐵金銀玲瓏圓作,內有香囊,機關巧智,雖外縱橫圓轉而內常平,能使不傾. 妃後貴人之所用之也”. see (Huilin 2009, p. 97). |

| 9 | Original: “漢書天文志: 南宮二十五星曰’哀烏郎位.’ 漢明帝時, 館陶公主為子求郎, 不許,而賜錢千萬; 謂群臣曰: ‘郎官上應列宿,出宰百里,非其人則民受其殃. ‘漢制: 尚書郎主作文書起草, 更直於建禮門內. 台給青纂白綾被, 或以錦被, 帷帳, 氈蓐, 畫通中枕太官供食物, 湯官供餅餌, 五熟果食, 五日壹美食,下天子一等. 給尚書郎指使二人, 女侍史二人, 皆選端正,執香爐, 香囊, 從入台, 護衣服”. see (Li 2009, p. 6). |

| 10 | Original: “華軒敞碧流, 官妓擁諸侯. 粉項高叢鬢, 檀妝慢裹頭. 亞身摧蠟燭, 斜眼送香毬. 何處偏堪恨, 千回下客籌”. see (Cao 2009, p. 3490). |

| 11 | Original: “殿上陳錦繡帷幟,垂香毬,設銀香獸前檻內,藉以文茵,設禦茶床、酒器於殿東北楹間”. see (Toqto 2009, p. 112: 6409). |

| 12 | Original: “宣和五年, 七月初一日, 昧爽, 文武百官, 聚集於宮省, 等候天子設朝, 須臾香球撥轉, 簾卷扇開”. see (Xuanhe yishi 2009, p. 24). |

| 13 | Original: “以皇太子府親事官充輦官, 前執從物, 儋子前小殿侍一人, 抱塗金香球”. see (Toqto 2009, p. 147: 1557). |

| 14 | Original: “今鍍金香毬,如渾天儀然,其中三層關棙,輕重適均,圓轉不已,置之被中,而火不覆滅. 其外花卉玲瓏而篆煙四,出真閨房之雅噐也”. see (Tian 2009, p. 178). |

| 15 | Original: “香毬不減橘團圓,橘氣毬香總可憐. 虮虱窠窠逃熱瘴,煙雲夜夜辊寒氈. 蘭消蕙歇東方白,炷插針牢北鬥旋. 一粒馬牙聊我輩,萬金龍腦付嬋娟”. See (Xu 2009, p. 62). |

| 16 | Original: “金蓮說著舒進手去被窩裡,摸見薰被的銀香球兒,“道:‘李大姐生了蛋了.’” See (Lanling Xiaoxiao Sheng 1916). |

| 17 | The use of gold- and silverware was also a sign of wealth and prestige. Further, the ancient Chinese believed that using gold- and silverware might extend one’s life, and that they also could be used for sacred purposes. |

| 18 | In traditional Chinese religion, the afterlife is analogous to human life, and ancestor ghosts need sustenance to survive. Many Daoist and Buddhist deities are powerful ancestors to petitioners and priests in ancient Chinese temples. Deities, ancestors, and hungry ghosts are flexible categories of spirits that define various states of existence in the afterlife. See (Habkirk and Chang 2017). Without communicating with each other, the Eastern Orthodox Church and Eastern Catholic Churches of the Byzantine Rite make considerable use of incense, which is viewed as a symbol of the Holy Spirit’s sanctifying grace and the prayers of the Saints ascending to heaven. |

| 19 | Despite the fact that the translation is credited to a Pāramiti (Bancimidi 般剌蜜諦) in 705 CE, the sutra has long been recognized as an apocryphal Chinese scripture, due to the lack of a known original Sanskrit form. |

| 20 | Original: “若諸世界, 隨所國土, 所有衆生, 隨國所生. 樺皮貝葉, 紙素白疊, 書寫此呪, 貯於香囊, 是人心惛, 未能誦憶, 或帶身上, 或書宅中, 當知是人, 盡其生年, 一切諸毒, 所不能害”. See (Lengyan jing 2009, p. 62). The translation is mine. |

| 21 | Claire Giraud-Héraud also establishes that the first spheres were of Chinese origin, and tracing their diffusion from the Islamic world to Europe. She consults valuable European sources and includes a table listing all of the incense spheres with Islamic ornamentation that she was able to identify. See (Giraud-Heraud 2004). |

| 22 | Original: “una grande ampolio di balsamo … vasi grandi di porcellana mai più veduti simili, nè meglio lavorati … vasi grandi di confectione, mirabolani e giengituo”. This was recounted in a letter sent by Pietro da Bibbiena, Lorenzo’s trusted secretary, to Clarice de’ Medici (1493–1528), who was then in Rome. See (Fabroni 1784, p. 2: 337). |

References

- Atil, Esin, William Thomas Chase, and Paul Jett. 1985. Islamic Metalwork in the Freer Gallery of Art. Washington, DC: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Auld, Sylvia. 2004. Renaissance Venice, Islam and Mahmud the Kurd: A Metalworking Enigma. London: Altajir World of Islam Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Auld, Sylvia. 2007. Master Mahmud and Inlaid Metalwork in the 15th Century. In Venice and the Islamic World, 828-1797. Edited by Stefano Carboni. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 212–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bedini, Silvio A. 1994. The Trail of Time: Time Measurement with Incense in East Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brentjes, Sonja. 2018. Teaching and Learning the Sciences in Islamicate Societies (800–1700). Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Yin 曹寅. 2009. Quan Tang shi 全唐诗 [Complete Poetry of Tang]. Vol. 510 of 900 vols. Beijing: Airusheng shuzihua jishu yanjiu zhongxin 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Contadini, Anna. 2006. Middle Eastern Objects. In At Home in Renaissance Italy. Edited by Marta Ajmar-Wollheim and Flora Dennis. London: V & A, pp. 308–21. [Google Scholar]

- de Honnecourt, Villard. 1959. The Sketchbook of Villard de Honnecourt. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fabroni, Angelo. 1784. Laurentii Medicis Magnifici Vita. Vol. 2 of 2 vols. Pisa: Gratiolius. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Jingliang 傅京亮. 2008. Zhongguo xiang wenhua中國香文化 [Chinese Incense Culture]. Jinan: Qilu shushe. [Google Scholar]

- Giraud-Heraud, Claire. 2004. Origine, provenance et fonction des globes à encens. Oriente Moderno 84: 477–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habkirk, Scott, and Hsun Chang. 2017. Scents, Community, and Incense in Traditional Chinese Religion. Material Religion 13: 156–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huilin 慧琳. 2009. Yiqiejing yinyi一切經音義 [Pronunciation and Meaning in the Complete Buddhist Canon]. Vol. 7 of 100 vols. Beijing: Airusheng shuzihua jishu yanjiu zhongxin. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Peter. 2018. The Mongols and the Islamic World: From Conquest to Conversion. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knechtges, David R., and Taiping Chang. 2010. Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide. 4 vols. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- La Niece, Susan. 2010. Islamic Copper-Based Metalwork from the Eastern Mediterranean: Technical Investigation and Conservation Issues. Studies in Conservation 55 S2: 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanling Xiaoxiao Sheng 蘭陵笑笑生 [The Scoffing Scholar of Lanling]. 1916. Jin Ping Mei/di 21 hui 金瓶梅/第21回-维基文库 [The Plum in the Golden Vase Chapter 21-Wikisource]. Available online: https://zh.wikisource.org/wiki/%E9%87%91%E7%93%B6%E6%A2%85/%E7%AC%AC21%E5%9B%9E (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Laufer, Berthold. 1916. Cardan’s Suspension in China. Holmes Anniversary Volume 29: 288–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lengyan jing [author unknown, this is the sutra’s abbreviated title]. 2009. Dafo Ding Rulai Mi Yin Xiu Zhengliao Yi Zhu Pusa Wanxiang Shoulengyan Jing 大佛頂如來密因修證了義諸菩薩萬行首楞嚴經 [The Sūtra on the Śūraṅgama Mantra That Is Spoken from above the Crown of the Great Buddha’s Head and on the Hidden Basis of the Tathagata’s Myriad Bodhisattva Practices That Lead to Their Verifications of Ultimate Truth]. Vol. 7 of 10 vols. Beijing: Airusheng shuzihua jishu yanjiu zhongxin. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Linfu 李林甫. 2009. Tang Liudian 唐六典 [The Six Statutes of the Tang Dynasty]. Vol. 1 of 30 vols. Beijing: Airusheng shuzihua jishu yanjiu zhongxin. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Xin 劉歆. 2009. Xijing Zaji西京雜記 [Miscellaneous Records of the Western Capital]. Edited by Hong Ge 葛洪. Vol. 1 of 6 vols. Beijing: Airusheng shuzihua jishu yanjiu zhongxin, pp. 284–364. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, Rosamond E. 2001. Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milburn, Olivia. 2016. Aromas, scents, and spices: olfactory culture in China before the arrival of Buddhism. Journal of the American Oriental Society 136: 441–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, Joseph. 1954. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Pt. 2, Mechanical Engineering. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nienhauser, William H., Jr. 1978. Once Again, the Authorship of the Hsi-Ching Tsa-Chi (Miscellanies of the Western Capital). Journal of the American Oriental Society 98: 219–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raby, Julian. 2012. The Principle of Parsimony and the Problem of the ‘Mosul School of Metalwork’. In Metalwork and Material Culture in the Islamic World: Art, Craft and Text. Edited by James W. Allan. London and New York: I.B. Tauris & Co., pp. 11–85. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Gang 尚刚. 2016. Datang xiangnang 大唐香囊 [Incense burner of the great Tang]. Yishu sheji yanjiu 藝術設計研究 [Art & Design Research] 1: 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Yiheng 田藝蘅. 2009. Liuqing ri zha 留青日札 [Daily Jottings of Liuqing]. Vol. 22 of 39 vols. Beijing: Airusheng shuzihua jishu yanjiu zhongxin. [Google Scholar]

- Toqto脫脫. 2009. Song shi 宋史 [History of the Song]. In Qing Qianlong Wenyuan ge siku quanshu chao neifu kanben清乾隆文淵閣四庫全書鈔內府刊本 [Qing Qianlong Wenyuan Pavilion Copy of the Imperial Collection of Four Treasuries]. 496 vols. Beijing: Airusheng shuzihua jishu yanjiu zhongxin. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Rachel. 1990–1991. Incense and Incense Burners in Mamluk Egypt and Syria. Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society 55: 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Rachel, Susan La Niece, Duncan Hook, and Raymond White. 1995. ‘Veneto-Saracenic’ Metalwork: An Analysis of the Bowls and Incense Burners in the British Museum. In Trade and Discovery: The Scientific Study of Artefacts from Post-Medieval Europe and Beyond. Edited by Duncan R. Hook and David R. M. Gaimster. London: British Museum, Department of Scientific Research, pp. 235–58. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Wei 徐渭. 2009. Xu Wenchang Wenji徐文長文集 [The Collected Works of Xu Wenchang]. Vol. 7 of 30 vols. Beijing: Airusheng shuzihua jishu yanjiu zhongxin. [Google Scholar]

- Xuanhe yishi 宣和遺事 [Remnant Affairs of the Xuanhe Reign]. 2009. Vol. 1 of 2 vols. Beijing: Airusheng shuzihua jishu yanjiu zhongxin.

- Yunlu 允禄. 1759. Huangchao liqi tushi 皇朝禮器圖式 [The Illustrated Catalogue of Imperial Ritual Instruments]; Vol. 3. 18 vols. Harvard-Yenching Library Chinese Rare Book Digitization Project. Peking: Wu ying dian. Available online: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:FHCL:10012889 (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Zhang, Baichun, and Miao Tian. 2019. Joseph Needham’s Research on Chinese Machines in the Cross-Cultural History of Science and Technology. Technology and Culture 60: 616–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Qiao 章樵. 2009. Guwen Yuan古文苑 [The Garden of Ancient Literature]. Vol. 3 of 21 vols. Beijing: Airusheng shuzihua jishu yanjiu zhongxin. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xun 張珣. 2006. Xiang zhi weiwu: Jinxing yishi zhong xianghuo guannian de wuzhi jichu香之為物:進香儀式中香火觀念的物質基礎 [Scent as substance: The material basis of Chinese incense-fire rituals and concepts]. Taiwan renleixue kan 4: 37–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).