Abstract

The study of social inequality has so far received little attention in religious education research, although this phenomenon has been studied in educational science and sociology of education research for fifty years. This article therefore aims to clarify the explanatory power of this research approach for research in religious education. Based on Bourdieu’s theory of cultural and social reproduction, a structural equation model is used to examine the extent to which students’ sex, socioeconomic status, and religious socialization determine unequal learning opportunities in religious education. The data basis of the study is a sample of 952 students from Germany who were interviewed by means of questionnaires. The results show that religious socialization and the students’ sex are relevant to unequal learning conditions, whereas the socioeconomic status of the family has a marginal influence. Unequal learning conditions are created in the classroom by differences in the perception of the relevance of the subject matter, and in the understanding of learning processes. Religious students are in both cases at an advantage compared to non-religious students.

1. Introduction

Social inequality in education is one of the greatest challenges for societies that strive to provide everyone with fair and good opportunities for participation and a self-determined life. As education is a key resource for personal development and access to other social goods, such as culture, health, or wealth, unequal educational opportunities threaten equality rights and human dignity in a fundamental way.

However, social inequality in education persists to this day, although researchers have been dealing with this problem for about fifty years (Becker 2003; Boudon 1974; Erikson and Jonsson 1996; Breen and Goldthorpe 1997; Shavit and Blossfeld 1993; Stocké 2007). The PISA studies in particular, which have been conducted regularly since 2000, have given new impetus to the discussion, and have led to educational innovations in many states. Surprisingly, this problem has hardly been discussed in religious education research, with a few exceptions (Grümme 2017, 2021; Unser 2016, 2019).

This article aims to explore the impact of social inequality in religious education. It demonstrates the explanatory power of this research approach, and proposes a conceptual model that can guide future research. To this end, it is necessary to clarify the concept of social inequality (Section 1.1) before discussing theories explaining social inequality in education (Section 1.2) and developing the conceptual model (Section 1.3), which is validated in the empirical part of this paper.

1.1. What Is Social Inequality?

The term social inequality refers to the phenomenon that people are different or unequal, but in a very specific sense. Not every difference between people is classified as social inequality. Therefore, it is helpful to distinguish social inequality from other forms of difference in order to give a clear definition of this term.

A first distinction can be made between “natural” and “social” inequality. People differ from each other in many characteristics that they were “born with”, such as shoe size or skin color. I refer to such differences here, for lack of a better term, as “natural inequality”. Social inequality can be distinguished from natural inequality in that social inequality does not refer to differences based on characteristics that are given to us at birth, but to differences that are socially made. Socially made differences are visible in their effect, expressed in terms of advantages or disadvantages; for instance, when people have unequal access to good jobs, health, or education (Breen and Jonsson 2005, p. 223; Kreckel 1992, p. 20). Such socially made differences can relate to natural differences, e.g., when people of color are excluded from educational institutions. However, the reason for their poor educational opportunities is, therefore, not their skin color, but racist rules and power structures in the education system. Their disadvantage is socially made, even if the social distinction refers to a natural characteristic in order to disguise the arbitrariness of such a distinction. The focus of the concept of social inequality is thus not on the description of characteristics of individuals (and the resulting differences to other individuals), but on the advantages and disadvantages associated with these characteristics in a society.

A second distinction must be made between individual and group inequalities. This distinction is particularly important in education, where terms such as talent, intelligence, or interest are used to describe and evaluate individual students. It is sometimes claimed that individual differences alone determine success or failure in education. Since social inequality, as explained above, refers to advantages and disadvantages caused by distinctions, rules, and power structures in our society (Kreckel 1992, pp. 15–16; Goldthorpe 2010, pp. 732–33), it would be wrong to call such individual differences social inequality. Instead, one speaks of social inequality when not only individuals, but entire social groups, are affected by advantages and disadvantages. Social inequality is thus not used to describe unequal opportunities based on individual abilities, talents, or gifts, but solely on the basis of belonging to a certain social group (such as women, migrants, or people from lower social classes). The crucial empirical question then, is how to distinguish precisely between individual and group inequalities.

A pragmatic and frequently used approach to address this problem is to analyze differences between social categories (e.g., between members of different social classes). According to this approach, differences between social categories are considered to be indicators of social inequality. What justifies this assumption? The argumentation builds on the insight that individual differences certainly exist, but that interaction with the social environment is an important factor in developing and benefiting from individual abilities. Consequently, members of a specific social category have better or worse chances of developing and benefiting from their abilities compared with others. If this is right, and if an examination considers the relevant social categories, then differences between social categories can be attributed to social factors, while differences within social categories can be ascribed to individual factors (Brake and Büchner 2012, p. 89). Rose et al. (1984) illustrate this argument with a metaphor:

“Suppose one takes from a sack of open-pollinated corn two handfuls of seed. There will be a good deal of genetic variation between seeds in each handful, but the seeds in one’s left hand are on the average not different from those in one’s right. One handful of seeds is planted in washed sand with an artificial plant growth solution added to it. The other handful is planted in a similar bed, but with half the necessary nitrogen left out. When the seeds have germinated and grown, the seedlings in each plot are measured, and it is found that there is some variation in height of seedling from plant to plant within each plot. This variation within plots is entirely genetic because the environment was carefully controlled to be identical for all the seeds within each plot. The variation in height is then 100 percent heritable. But if we compare the two plots, we will find that all the seedlings in the second are much smaller than those in the first. This difference is not at all genetic but is a consequence of the difference in nitrogen level. So the heritability of a trait within populations can be 100 percent, but the cause of the difference between populations can be entirely environmental.” (Rose et al. 1984, p. 118).

Following these considerations, the concept of social inequality is defined as follows for the field of education: “Social inequality in education describes unequal opportunities of students to attain educational achievement and to participate in learning processes due to their affiliation with a specific social category like women, migrants, or children from lower classes. Social inequality in education is indicated by significant differences between social categories (e.g., men and women; migrants and non-migrants) concerning their levels of educational achievement and participation.” (Unser 2019, p. 52).

1.2. Theories That Explain the (Re)production of Social Inequality in Education

There are two main theoretical approaches to explaining the (re)production of social inequality in education: Boudon’s theory of rational educational choices (Boudon 1974), and Bourdieu’s theory of cultural and social reproduction (Bourdieu 1977; Bourdieu and Passeron 1979, 1990). These two theories differ in terms of explaining the cause of social inequality in education, and in terms of their degree of formalization, which is illustrated and discussed below.

1.2.1. Boudon’s Theory of Rational Educational Choices

Boudon’s theory of rational educational choices, which has been further developed by others (Breen and Goldthorpe 1997), is currently the most influential, elaborate, and empirically tested sociological theory used to explain social inequalities in educational systems (Breen and Jonsson 2005, p. 227). The theory aims at explaining “the differences in level of educational attainment according to social background” (Boudon 1974, p. XI) by taking into account both individual will and social structure. Boudon assumes that people (parents or students) behave rationally when they choose a particular educational program for themselves or their children (Boudon 1974, p. 36). Two things are crucial for their educational decisions. First, people want to avoid social downward mobility. It is important to them that they, or their children, achieve educational qualifications that enable them to work at least at the level of other family members in terms of income and prestige. Second, they seek to maximize the utility of their educational choices, where utility is a ratio of (a) the benefits and (b) the costs of a particular educational program. The benefits and costs of an education program strongly depend on the social position of the respective family, as families from higher social classes need higher qualifications for their children in order to avoid social downward mobility (benefits), while families from lower social classes have fewer resources to bear the costs of long-term education programs (costs) (Boudon 1974, pp. 29–30). According to Boudon, these educational decisions, which are influenced by the social position of the family, are the main cause of social inequality in education (Boudon 1974, p. 84). In this context, he speaks of secondary stratification effects, which he distinguishes from primary stratification effects by which class-specific differences in students’ abilities are meant (Boudon 1974, pp. 29–30). While he attributes a central role in the reproduction of social inequality to secondary stratification effects, he sees the influence of primary stratification effects as marginal (Boudon 1974, pp. 114–15).

Although the theory of rational educational choices is consistent with most empirical data concerning class origin and the choice of educational programs (Breen and Jonsson 2005, p. 227; Vester 2006, p. 21), there are at least two reasons why this theory is not suitable for the study of social inequality in religious education. The first one is obvious: Boudon’s theory ignores processes of learning and teaching in the classroom due to the assumption that the school itself plays a negligible role in producing social inequality. Instead, the research focuses on decisions at educational transitions. Consequently, Boudon’s theory, which is a sociological one, and the pedagogical research on religious education do not have the same object of research (Unser 2014, p. 21). This observation alone would not justify giving preference to another theory if Boudon’s approach were empirically convincing. However, this is not the case. The second reason that speaks against the suitability of Boudon’s theory lies in the insufficient empirical measurement of decision-making processes that form the core of his theory. Many empirical studies that use the theory of rational educational choices as a theoretical background do not examine the decision-making process itself (Breen and Jonsson 2000; Jackson et al. 2007). Instead, they indirectly operationalize the parameters of the theoretical model (Stocké 2007, pp. 507–8), e.g., by deriving the costs for a family based on social class background. As a result, further untested auxiliary hypotheses (for example, that the perceived costs and perceived benefits of educational programs correlate strongly with social class background) are introduced. However, the few studies that directly operationalize decision-making processes have found that secondary stratification effects have either little (Becker 2003) or no effect (Stocké 2007) on explaining educational decisions. These two reasons taken together justify choosing a different theory to study social inequality in religious education.

1.2.2. Bourdieu’s Theory of Cultural and Social Reproduction

The second influential theoretical approach to explaining social inequality in education is Bourdieu’s theory of cultural and social reproduction. In contrast to Boudon’s approach, Bourdieu emphasizes the importance of classroom processes in the production of social inequality. In Bourdieu’s thinking, the school is an institution of the elite, by which he means members of the educated upper class. It helps this elite by legitimizing their definition of the right culture and reproducing their privileges (Bourdieu 1977, p. 488). This is done, firstly, by orienting the school to the lifestyle—“habitus” in Bourdieu’s terminology—of the elite in the selection of topics to be taught and techniques of cultural exploration. Thus, students from the educated upper class have an a priori advantage because they are already familiar with what is taught in school, while students from other classes cannot benefit from the socialization they have experienced in their families (Bourdieu and Passeron 1979, p. 24). Secondly, schools reproduce this a priori inequality by not helping underprivileged students develop the necessary knowledge, skills, and techniques to succeed in school (Bourdieu and Passeron 1979, pp. 69–70; Bourdieu 1977, p. 494). Instead, it takes inequalities for granted and reinterprets them as differences in abilities and talents. School thus becomes a game for the privileged (Bourdieu and Passeron 1979, pp. 21–22). For Bourdieu, this is reflected in communication and interaction during lessons. He assumes that teaching works with special codes, and that students from the privileged classes are better able to decode the communication and the interaction due to their habitus (Bourdieu 1977, pp. 493–94). In contrast, students from underprivileged backgrounds often perceive that this game is not made for them because they lack that natural access to education that is typical of their privileged classmates. According to Bourdieu, this leads them to choose less prestigious educational programs (Bourdieu 1977, p. 495; Bourdieu and Passeron 1979, pp. 2–5).

However, Bourdieu’s theory is also criticized. At least two points should be mentioned here. The first point is Margaret Archer’s criticism that Bourdieu’s theory of cultural and social reproduction is not universal, but deeply rooted in the French context. She argues that Bourdieu neglects that the French educational system in which he developed his theory has unique characteristics that make it impossible to apply the theory to other contexts and thus explain the emergence of social inequality in other national educational systems (Archer 1993, pp. 225–30). This comment must be taken very seriously. However, it does not question the value of Bourdieu’s work per se. Other scholars point out that Bourdieu does not formulate theories in the sense of a system of confirmed hypotheses, but rather works on theoretical concepts (such as “habitus”) that help him to understand reality. These concepts are “tools for thinking about specific sociological problems” and “were never intended as a set of self-sufficient theoretical entities” (Lane 2000, p. 3). Such an interpretation can build on Bourdieu’s self-interpretation (Bourdieu and Wacquant 2006, pp. 193–201). According to Bourdieu, his books and papers are nothing more than a demonstration of how to apply his concepts to specific problems.

The second point of criticism is clearly connected with the problem of generalizability just discussed, and also concerns the scientific status of Bourdieu’s work. Several authors criticize Bourdieu’s theory of being a collection of admittedly interesting, but barely empirically tested assumptions (Kramer 2011, p. 112) that are ideologically overloaded (Goldthorpe 2007, p. 19), or even falsified by other studies (Baumert and Schümer 2001, pp. 352–53). However, there are also a lot of studies building on some of Bourdieu’s concepts that are producing important findings on the reproduction of social inequality in educational systems (Jaeger 2011; Lareau and Weininger 2003; Kramer 2011; Büchner and Brake 2006; Grundmann et al. 2006). This mirrors exactly the discussion about the scientific status of Bourdieu’s work. Some scholars interpret Bourdieu’s thoughts as scientific theories lacking empirical validation, others interpret his work as a presentation of conceptual tools inspiring their own research. One can certainly agree with most of the critics that Bourdieu’s theoretical assumptions are barely empirically tested, or, even more so, that some of these assumptions are formulated in a way that makes it impossible to test them empirically at all. However, there are also good reasons to recognize that Bourdieu provides conceptual tools that inspire a lot of studies and have led to the formulation and examination of empirical theories.

What can be taken from Bourdieu, then, is not a well-articulated theory that can be easily transferred to the field of religious education, but his style of thinking and some of his conceptual tools. Building on this, however, requires the development of an appropriate conceptual model that goes beyond Bourdieu’s own research. The presentation and justification of such a model is the task of the next section.

1.3. A Conceptual Model for the Study of Social Inequality in Religious Education

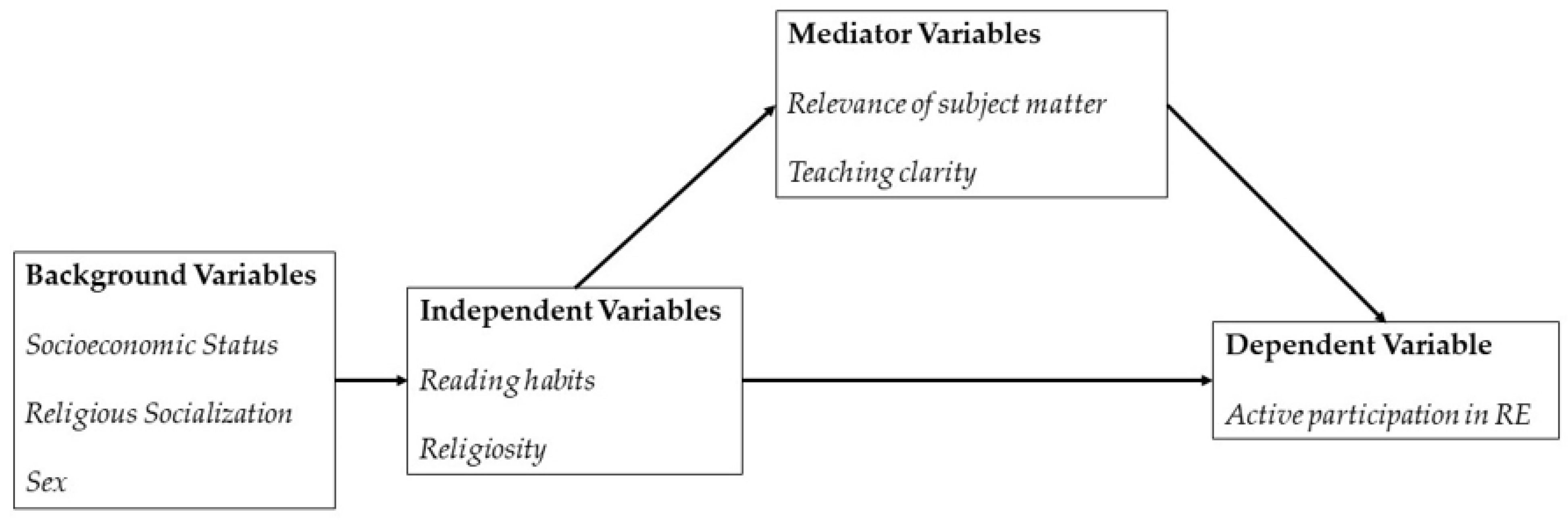

It is the aim of the following considerations to design a conceptual model that makes it possible to examine the influence of social inequality in religious education. The model is based on the definition of social inequality in education developed in Section 1.1. and on Bourdieu’s considerations. Bourdieu’s central assumptions are that differences in family socialization lead to the formation of a habitus in students, which has either a privileging or a disadvantaging effect at school. This is reflected in the classroom by the fact that the privileged students are more familiar with the subject matter, and better able to decode the demands of the lesson, compared to the non-privileged students. These assumptions are here transferred into an empirically testable model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of unequal learning opportunities in RE.

Several studies have shown that families with high socioeconomic status (SES) are better able to create socialization contexts in which children can develop intellectual and social skills (Conger and Dogan 2008, p. 446; Rogoff et al. 2008, p. 491), which in turn influences their school success and educational achievement (Jungbauer-Gans 2004, p. 393; Watermann and Baumert 2006, p. 77; Baumert et al. 2003, p. 63; De Graaf et al. 2000, pp. 103–4). In contrast, there are only a few studies in religious education research that examine the influence of SES on attitudes towards the subject matter (Gibson et al. 1990; Fulljames et al. 1991), the subject in general (Francis 1992), or active participation (Unser 2016, 2019). The effects found are thus mostly not significant or marginal.

Religious socialization refers here to all rites and practices in everyday family life that serve to introduce the child to a religious worldview, such as praying together, telling religious stories, or attending church services together. It is known from the literature that family religious socialization is the most important factor in explaining the religiosity of children and adolescents (De Hart 1990; Myers 1996; Martin et al. 2003; Sherkat 2003). Since the latter is relevant to religious education (see below), religious socialization is expected to play an important role in social inequality in religious education.

It is well documented that the sex of the students also plays an important role in religious education. Female students are, on average, more religious (Lewis et al. 2009, pp. 85–86; Ziebertz et al. 2003, pp. 133, 352–53) and show higher approval ratings of the subject matter and the subject itself compared to male students (Sjöborg 2013, pp. 46–48; Lewis et al. 2009, p. 84).

The next set of variables in the model, referred to here as independent variables, comprise two aspects of students’ habitus that impact religious education: reading habits and religiosity. It is assumed, as argued above, that reading habits depend on the SES of the family and religiosity on religious socialization. It is further assumed that sex has an effect on both variables in the sense that female students have, on average, higher values than male students.

Reading habits are a widely used indicator of what Bourdieu refers to as “cultural capital” (De Graaf et al. 2000; Lareau and Weininger 2003), i.e., the affinity for, and necessary skills in, dealing with culture. Several studies have shown that reading habits depend on the SES of the family, and that they are crucial for school success (Jungbauer-Gans 2004, p. 393; Watermann and Baumert 2006, p. 77; Baumert et al. 2003, p. 63; De Graaf et al. 2000, pp. 103–4). In the field of religious education, there is little research examining the influence of students’ reading habits, but the few that do exist point to a positive correlation with the level of active participation (Unser 2016, p. 89; 2019, p. 242). However, since learning processes in religious education—similar to many other subjects—often presuppose the mastery of certain cultural techniques, such as text analysis or argumentation, there are also good theoretical reasons for assuming that reading habits are important in this subject.

Religiosity is understood here, in the tradition of Charles Y. Glock (Glock 1962), as a construct that describes the intensity of personal acquisition of a religious tradition. Students who are very religious thus have a strong personal connection to the subject matter of religious education. This can be an advantage, for example, in the model of denominational religious education, as is the case in large parts of Germany, since the teaching also aims to address the existential significance of religion in addition to knowledge about it. Accordingly, there are several studies from Germany showing that students’ religiosity correlates positively with their affinity for religious education (Ziebertz et al. 2003, pp. 212–13; Ziebertz 2005, p. 217; Ziebertz and Riegel 2008, p. 147). However, this is not a purely German phenomenon. In countries that practice different models of religious education, such as Great Britain (Thanissaro 2012, pp. 203–5) or Sweden (Sjöborg 2013, p. 42), positive correlations between students’ religiosity and their attitudes towards religious education can also be found.

The third set of variables in the model, referred to here as mediator variables, includes two characteristics of religious education lessons as perceived by the students: the relevance of the subject matter and teaching clarity. These two variables will be used to test Bourdieu’s argument that students’ habitus play a role in the classroom, in that privileged students are more familiar with the subject matter, and better able to decode the demands of the lesson, than non-privileged students.

Relevance of subject matter here describes the students’ evaluation of the educational content as either relevant to mastering challenges in their everyday life or not. Several studies have found that learning achievement is improved when students perceive the subject matter as relevant to their everyday life (Hattie 2009, pp. 50–51), and that perceived relevance improves their motivation to dedicate themselves to learning tasks (Assor et al. 2002; Gaspard et al. 2015; Schreier et al. 2014). In the field of religious education, there are a few studies showing that relevance of subject matter positively influences students’ learning activities (Unser 2018, p. 108) and outcomes (van der Zee et al. 2008, p. 132). Furthermore, they have shown that perception of relevance correlates with their religiosity (Unser 2018, p. 110; van der Zee et al. 2006, p. 285), which is consistent with the findings of several other studies (Bucher 1996, p. 52; 2000, pp. 81–83; Lehman 1971, p. 38; Sjöborg 2013, p. 48).

Teaching clarity is commonly referred to in educational research as the teacher’s ability to formulate instructions and explain complex topics in such a way that “the desired meaning of course content and processes [arises] in the minds of students” (Chesebro and McCroskey 2001, p. 62). In slight contrast, this variable in the present study represents students’ ability to understand the structure of a lesson and the teacher’s instructions. Several studies have shown that well-structured lessons improve the effectiveness of learning processes (Klieme and Rakoczy 2003, p. 355; Lipowsky 2015, p. 81). However, Hattie found in his meta-analysis that students’ individual perception of structure has a significantly stronger influence on their learning success than a general assessment of the teacher’s performance (Hattie 2009, pp. 125–26). In the field of religious education, there are hardly any studies that examine the influence of teaching clarity on learning processes or outcomes. Nevertheless, the few existing studies on this topic found teaching clarity to have a positive influence of on students’ learning activities as well as a positive correlation with their religiosity (Unser 2018, p. 110; 2019, p. 291).

On the far right of the model is the dependent variable of the study, active participation in religious education (RE), which here means a committed engagement with the learning tasks of the lesson. In line with the definition of social inequality in education formulated above (see Section 1.1), the degree of active participation is understood here as an indicator of learning opportunities.

The model thus formulated is intended to answer the following three research questions (RQ):

- How well can the model explain differences in active participation in religious education?

- To what extent are differences in active participation related to students’ socioeconomic status, religious socialization, and sex?

- To what extent is the influence of reading habits and religiosity on active participation mediated by the relevance of the subject matter and the teaching clarity?

RQ 1 assesses the general explanatory power of the conceptual model, RQ 2 examines the impact of social inequality in religious education, and RQ 3 serves to test Bourdieu’s claims as possible explanations for social inequality in religious education.

2. Method

The following section serves to present the methodological approach of the present study. First, the design of the study and the process of data collection are outlined (Section 2.1). Subsequently, the instruments used to measure the variables of the model (Section 2.2) and the characteristics of the sample are presented (Section 2.3). Finally, the statistical procedure used to examine the research questions is explained (Section 2.4).

2.1. Design and Data Collection

The present study follows a quantitative, cross-sectional survey design. The questionnaire comprised four thematic blocks, which included questions on demographic characteristics, leisure time activities, religious education, and religiosity. Data collection took place between September 2014 and March 2015 among ninth graders participating in Catholic or Protestant religious education classes at public schools in southwestern Germany (state of Baden-Württemberg). The decision to focus on ninth graders was motivated by the fact that this is the last grade of the lowest educational program in the German school system. Since it is well documented that the educational trajectory and social background of students in the German system are correlated (Geißler 2014, p. 353), it is necessary to collect and compare data from all educational programs when studying social inequality in school.

Schools participating in the survey were randomly selected based on a list of administrative districts and schools in those districts. Upon agreement of participation, the headmasters and religious education teachers received by mail the necessary materials for the survey (including a brief introduction and consent forms to be signed by the students’ parents). Since the schools, but not the students, were randomly selected, this sampling strategy resulted in a cluster sample. In total, 38 schools with 1663 students agreed to cooperate, and 952 students actually participated in the survey. The response rate is therefore 57.2%.

Participating students were given the opportunity to complete an online questionnaire during religious education lessons. To ensure that only the selected students participated, teachers received a separate transaction number (TAN) for each student, which allowed exclusive access to the online questionnaire. The TANs lost their validity after a single use. Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous, of which the students were informed at the beginning of the questionnaire. They were also informed that the data collected would not be passed on to third parties (not even to their teachers). As the students studied were minors, they had to provide a signed consent form from their parents in order to be allowed to participate in the study.

2.2. Instruments

The wording of all items used to measure the variables of the model is provided in Table A1 of Appendix A.

The variable Active participation in RE is measured using five items developed specifically for this study (Unser 2019, pp. 177–96). The respondents were presented with case vignettes describing a typical learning situation in religious education. They were then presented with students who behaved differently in this situation (active participation, criticism of the learning task, withdrawal). Then, the respondents were asked to rate, on a five-point scale (from “not at all” to “completely”), to what extent they resembled these students in their own behaviour. The five items measuring active participation show acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.786).

The variable Relevance of subject matter is measured using four items that ask whether respondents can relate the lesson content to their everyday life (Klein-Heßling and Jerusalem 2002, p. 14). The wording of these items was adapted to refer to the teaching content of religious education. Respondents were asked to indicate the relevance they experienced, on a five-point scale (from “I totally disagree” to “I totally agree”). This scale has good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.860).

The variable Teaching clarity is measured using three items that were originally used in the first PISA study (Kunter et al. 2002, p. 259). The items ask whether respondents feel clearly instructed by their teacher. The wording of these items was adapted so that they clearly refer to religious education. Respondents were asked to indicate, on a four-point scale (from “never” to “in every lesson”), to what extent they perceived teaching clarity. This scale shows acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.756).

The variable Reading habits is measured using three items that ask about the extent to which respondents read outside of school. The items used here are from a questionnaire for adolescents on their leisure activities (Beckert-Zieglschmid and Brähler 2007, p. 132). Respondents were asked to indicate the frequency of their reading habits on a five-point scale (from “never” to “very often”). The internal consistency of this scale is acceptable (Cronbach’s α = 0.662).

The measurement of the variable Religiosity is oriented towards the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS) developed by Huber (Huber and Huber 2012). Although some of the items used here are not from the CRS, but are instead from a survey on the religiosity of young people (Ziebertz et al. 2003), their selection follows the conceptual idea of the CRS, which distinguishes between five dimensions of religiosity, namely the intellectual dimension (item 1) and the dimensions of religious experience (item 2), ideology (item 3), private (item 4) and public practice (item 5). According to the instructions in Huber and Huber (2012, p. 720), the two items measuring private and public practice were recoded so that all five items have a value ranging between 1 and 5. The five items measuring religiosity show acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.787).

The Socioeconomic status of the students is operationalized by the International Socio-Economic Index (ISEI) of their parents, a mixed index that takes into account income as well as occupational prestige and educational level (Ganzeboom et al. 1992). Students were asked, in open-ended items, what occupations their mother and father have and what exactly they do in their job. Based on this information, a specific ISEI value was assigned to the mother and father using the International Standard Classification of Occupations 1988 (ISCO-88). In cases with different values for mother and father, the higher value was used (HISEI). Three coders interpreted the students’ responses independently to ensure objectivity. The inter-coder reliability was acceptable (Krippendorff’s α = 0.765).

The variable Religious socialization is measured using five items that ask about religion-related activities in the family (Bucher 1996, pp. 51–52). Respondents were asked to indicate, on a four-point scale (from “never” to “very often”) how frequently they have experienced such activities. This scale has good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.855).

The last variable, Sex, was measured using an item asking respondents to indicate whether they were female or male.

2.3. Sample

The sample of the present study consists of 952 ninth graders who attended Catholic or Protestant religious education classes in the school year 2014/15 in the southwest of Germany (federal state of Baden-Württemberg). Most of the students were between fourteen and fifteen years old (89%), and about half of them are female (49%). There is a slight overrepresentation of students attending Catholic religious education classes (58.3%) compared to those attending Protestant religious education classes (41.7%). The majority of respondents (50.8%) attended the highest educational program in the German school system (Gymnasium), while 30.7% attended the middle (Realschule) and 18.5% the lowest (Hauptschule) program.

Table 1 gives an overview of the sample characteristics with regard to the variables used in the conceptual model.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the included variables.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

To answer the research questions of this article, a structural equation model is computed. This involves assessing whether the model fits the data structure (via absolute fit indices, such as RMSEA, and incremental fit indices, such as CFI and TLI), and whether the variables included contribute substantially to explaining social inequality in religious education (via explained variance and path coefficients). The structural equation model was computed using lavaan version 0.6–9, an SEM package for R (Rosseel 2012). The estimator used is maximum likelihood with robust standard errors and a Satorra–Bentler scaled test statistic.

3. Results

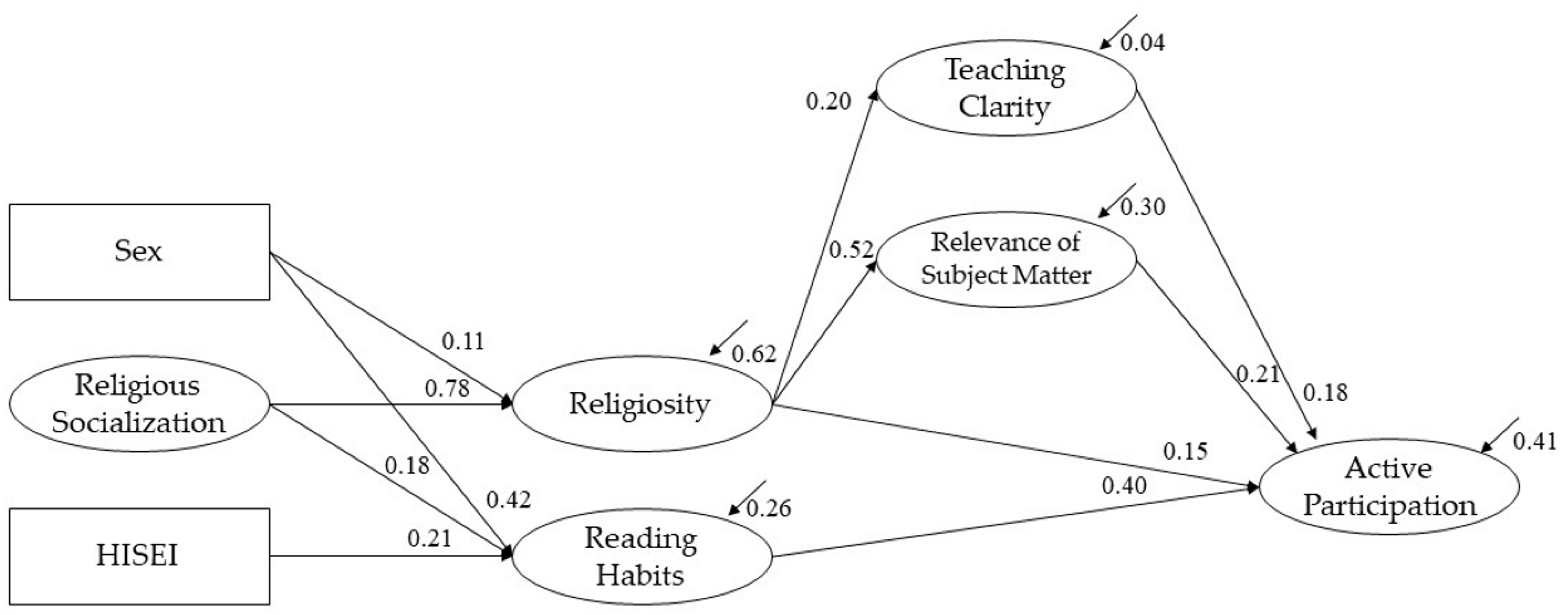

This section presents the results of the analysis, which are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structural equation model of unequal learning opportunities in RE. Note. Information about the model fit: χ2(d.f. = 307; N = 751) = 872.728 (p = 0.000); χ2/d.f. = 2.84; RMSEA = 0.052; CFI= 0.916; TLI = 0.924. Only those path coefficients that reach a significance level of p < 0.05 are documented in the figure. Further information on the confirmatory factor analyses of the scales included in the structural equation model can be found in Table A2 in the Appendix A.

A first look at the information regarding the model fit (χ2, χ2/d.f., RMSEA, CFI, and TLI) shows that the theoretical model fits the data structure sufficiently well, which is why the research questions can be answered in a second step.

The first research question was: How well can the model explain differences in active participation in religious education? A look at the explained variance of the latent variable “active participation” (indicated in Figure 2 by the slanted arrow at the upper right edge of the ellipse) shows that 41% of the differences in active participation in religious education can be explained by the model (R2 = 0.41). Following Cohen’s classification of effect sizes (Cohen 1992), the predictors of the model have a large effect on active participation (f2 = 0.69). Accordingly, the explanatory power of the model can be evaluated as quite good.

The second research question was: To what extent are differences in active participation related to students’ socioeconomic status, religious socialization, and sex? To answer this question, the indirect effects of the three background variables on the dependent variable have to be calculated. In the case of socioeconomic status (HISEI), there is only one indirect effect via the path HISEI → Reading Habits → Active Participation. In the case of sex and religious socialization, we have indirect effects from four paths each, which influence active participation via reading habits, religiosity, relevance of the subject matter, and teaching clarity. Taking all these paths together, the following indirect effects can be found. Students’ socioeconomic status has the smallest effect on their active participation in religious education (β = 0.08), followed by their sex (β = 0.20), and religious socialization (β = 0.30). In Cohen’s classification (Cohen 1992), the strength of the effect of sex can be described as small, and that of religious socialization as medium. The strength of the effect of socioeconomic status is marginal.

The third and last research question asked was: To what extent is the influence of reading habits and religiosity on active participation mediated by the relevance of the subject matter and the teaching clarity? Figure 2 shows that there is no significant influence of reading habits on students’ perception of teaching clarity or relevance of the subject matter in religious education. Thus, there are no mediation effects for this variable. In contrast, mediation effects are found with regard to students’ religiosity. On the one hand, there is an effect mediated by the relevance of the subject matter (β = 0.11); on the other hand, there is an effect mediated by the teaching clarity (β = 0.04). If one sums up these indirect effects, as well as the direct effect of religiosity (βtotal = 0.11 + 0.04 + 0.15 = 0.30), the share of mediation can be determined. Accordingly, 50% of the effect of religiosity is mediated by the two variables “relevance of subject matter” and “teaching clarity”; the share of the variable “relevance of subject matter” is higher (37%) than that of the variable “teaching clarity” (13%).

4. Discussion

The aim of this paper was to examine the influence of social inequality in religious education, and thus to assess the significance of this approach for religious education research. While questions of the structural disadvantage of certain social groups are long-standing in educational science and sociology of education research (Boudon 1974; Breen and Goldthorpe 1997; Baumert and Schümer 2001; Becker 2003; Breen and Jonsson 2005), there are only a few studies in the field of religious education that deal with this (Unser 2016, 2019; Grümme 2017, 2021). However, if religious education is to offer all students equal learning opportunities, phenomena of structural disadvantage must be investigated more thoroughly than before, and eliminated through pedagogical innovations.

This article makes a first contribution to this by showing to what extent the degree of active participation—understood here as an indicator of unequal learning opportunities—depends on the sex, religious socialization, and socioeconomic status of the students. Furthermore, following Bourdieu (Bourdieu 1977; Bourdieu and Passeron 1979), the hypothesis was examined that the perception of teaching clarity and relevance of subject matter can explain the unequal learning conditions. If this is the case, two characteristics of teaching would be identified, to which a pedagogical intervention could then be referred.

The results of the structural equation model show that the theoretical model has high explanatory power with regard to differences in active participation (R2 = 0.41). In fact, the different learning opportunities can be partly attributed to social causes, especially religious socialization and the students’ sex. The socioeconomic status of the family, on the other hand, has a marginal influence. These findings are consistent with a number of previous studies that have drawn attention to the importance of religiosity and gender in religious education (Lewis et al. 2009; Sjöborg 2013; Thanissaro 2012; van der Zee et al. 2006, 2008; Ziebertz 2005; Ziebertz et al. 2003). Likewise, the results are consistent with previous studies that have found a minor influence of socioeconomic status in relation to religious education (Francis 1992; Fulljames et al. 1991; Gibson et al. 1990).

What distinguishes the current article from the earlier studies, however, is the structural perspective. Through the structural equation model presented in Figure 2, it becomes clear that learning opportunities in religious education depend not only on individual characteristics of the students, but also on their socialization context and sex. Furthermore, it can be shown, at least for the variable religiosity, how a privileged position in religious education arises. It results from the fact that the perceptions of the relevance of the subject matter, and of the teaching clarity, increase with religiosity, and thus have a positive effect on active participation.

This finding must be taken seriously, especially as the number of religious students is declining in most countries, and the question of how to provide adequate religious education to non-religious students is becoming more pressing. However, if learning opportunities are dependent on being raised in a religious family, the acceptance of religious education in public education will continue to decline. Future studies can build on this finding and, for example, develop and test interventions that not only increase the perception of relevance, but also the understanding of learning processes in religious education among non-religious students.

Furthermore, future studies may look more intensively than before at characteristics of religious education lessons. In the present article, only two such characteristics (relevance of subject matter and teaching clarity) were examined. They were able to explain 50% of the influence of religiosity on active participation. However, this also means that another 50% awaits explanation. This is even more evident in the case of reading habits. Here, no explanatory mediation effects could be found at all. The analysis of such characteristics is becoming increasingly important, because only here can pedagogical changes be made. Scientific knowledge about this topic may help religious education teachers to better address the unequal learning conditions of their students.

However, at least two methodological limitations must be considered when evaluating the results of this study. The first limitation concerns the sample, and thus also the question of the generalizability of the results. In this study, a regional sample from the southwest of Germany was examined. Accordingly, the results found here can only be generalized for the federal state investigated. Thus, the validity of the findings for the whole of Germany or even for other countries remains to be proven in replication studies. This is also important because religious education in many countries differs considerably from the denominational approach prevalent in large parts of Germany. However, since results of studies in other countries, such as Great Britain (Thanissaro 2012), Sweden (Sjöborg 2013), and the Netherlands (van der Zee et al. 2008) point in a similar direction, one should not rashly attribute the results of the present study to the German denominational approach. Whether there are similar problems of social inequality in religious education in other countries remains to be investigated.

A second methodological limitation concerns the design of the study. The data were collected by a questionnaire. This means that all information on the variables of the model is based on self-reporting and self-assessment by the students. The advantage of such a survey design is that it is relatively easy to collect data from a large number of people. At the same time, however, the data can be influenced by social desirability or cognitive biases. Social desirability usually occurs with questions whose answers generate negative feelings in respondents. In the present study, this could be the case with the questions on active participation, when respondents deviate from the ideal of an engaged student. Therefore, it would be desirable if the results of this study could be replicated by other data sources, especially observational data from religious education lessons, which would allow the degree of participation to be recorded more objectively. Cognitive bias can be present when respondents do not have enough information to answer the questions. In the present study, this could concern the assessment of the relevance of the subject matter or the teaching clarity. In educational research, there is a methodological debate about whether such classroom characteristics can be validly measured by self-report or by external observers. As Hattie (2009, p. 126) has shown in his meta-analyses, students’ self-reports have a significantly stronger influence on their learning achievements than evaluations of observers or teachers. This is an argument for the methodological approach used in this study. However, supplementing these results with observational data would increase the reliability and robustness of the results presented here.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Documentation of the item wording.

Table A1.

Documentation of the item wording.

| Variable | Item Code | Wording |

|---|---|---|

| Active participation | Active_1 | Christine compiles two lists about her knowledge on mosques and churches. Then she considers what the commonalities and the differences might be. She writes her findings onto the exercise sheet. |

| Active_2 | Christine puts her hand up and asks the imam a question about the mosque. This question has been on her mind during the visit. | |

| Active_3 | Tobias considers the information in the movie and his own opinion. Then, he puts his hand up and presents his opinion with proper arguments. | |

| Active_4 | Tobias recollects what was taught in RE about Ramadan and Lent. He makes notes on his exercise sheet and distinguishes between commonalities and differences. | |

| Active_5 | Tobias puts his hand up and asks a question about the headscarf. This question has been on his mind since they discussed this movie about the headscarf in RE. | |

| Relevance of subject matter | Relevance_1 | What I learn in RE is useful even outside the school. |

| Relevance_2 | What I learn in RE helps me to solve problems in everyday life. | |

| Relevance_3 | What I learn in RE is relevant to my life. | |

| Relevance_4 | I learn in RE what I can do if I have problems in everyday life. | |

| Teaching clarity | Clarity_1 | Everything we are doing in RE is carefully planned. |

| Clarity_2 | Our RE teacher tells us at the beginning of the lesson what we should do. | |

| Clarity_3 | Our RE teacher clearly instructs us what we should do. | |

| Reading habits | Reading_1 | How often do you exercise the following leisure time activity: reading non-fiction books? |

| Reading_2 | How often do you exercise the following leisure time activity: reading newspapers or magazines? | |

| Reading_3 | How often do you exercise the following leisure time activity: reading novels? | |

| Religiosity | Religiosity_1 | How often do you think about questions of faith? |

| Religiosity_2 | People say that they have experienced a closeness to God because of their faith. Have you ever experienced a closeness to God? | |

| Religiosity_3 | There is a God who takes care of every person. | |

| Religiosity_4 | How often do you pray? | |

| Religiosity_5 | How often do you attend religious services? | |

| HISEI | HISEI | What is your mother’s/father’s profession (or what was the last job she/he worked in)? Can you describe what your mother/father exactly does (or did) in this job? |

| Religious Socialization | Socialization_1 | My parents attended religious services with me. |

| Socialization_2 | My parents told me about God. | |

| Socialization_3 | My parents said (or say) a prayer with me before going to bed. | |

| Socialization_4 | We prayed (or pray) at home before eating. | |

| Socialization_5 | My parents told (or tell) me biblical stories. | |

| Sex | Female_dummy | Are you female or male? |

Note. All wordings presented here are auxiliary translations of items originally written in German. The English translation has not been validated in a statistical sense. The original German items can be requested from the author.

Table A2.

Confirmatory factor analyses of the scales included in the structural equation model.

Table A2.

Confirmatory factor analyses of the scales included in the structural equation model.

| Factor | Item | Factor Loading | p | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active participation | Active_1 | 0.639 | 0.000 | 0.784 | 0.421 |

| Active_2 | 0.610 | 0.000 | |||

| Active_3 | 0.666 | 0.000 | |||

| Active_4 | 0.675 | 0.000 | |||

| Active_5 | 0.654 | 0.000 | |||

| Relevance of subject matter | Relevance_1 | 0.797 | 0.000 | 0.863 | 0.613 |

| Relevance_2 | 0.851 | 0.000 | |||

| Relevance_3 | 0.779 | 0.000 | |||

| Relevance_4 | 0.696 | 0.000 | |||

| Teaching clarity | Clarity_1 | 0.725 | 0.000 | 0.769 | 0.527 |

| Clarity_2 | 0.686 | 0.000 | |||

| Clarity_3 | 0.765 | 0.000 | |||

| Reading habits | Reading_1 | 0.585 | 0.000 | 0.663 | 0.404 |

| Reading_2 | 0.506 | 0.000 | |||

| Reading_3 | 0.783 | 0.000 | |||

| Religiosity | Religiosity_1 | 0.610 | 0.000 | 0.795 | 0.440 |

| Religiosity_2 | 0.638 | 0.000 | |||

| Religiosity_3 | 0.621 | 0.000 | |||

| Religiosity_4 | 0.646 | 0.000 | |||

| Religiosity_5 | 0.785 | 0.000 | |||

| Religious Socialization | Socialization_1 | 0.681 | 0.000 | 0.856 | 0.545 |

| Socialization_2 | 0.808 | 0.000 | |||

| Socialization_3 | 0.724 | 0.000 | |||

| Socialization_4 | 0.702 | 0.000 | |||

| Socialization_5 | 0.768 | 0.000 |

Note. χ2 (d.f. = 307; N = 751) = 872.728 (p = 0.000); χ2/d.f. = 2.84; RMSEA = 0.052; CFI = 0.916; TLI = 0.904.

References

- Archer, Margaret. 1993. Bourdieu’s Theory of Cultural Reproduction: French or Universal? French Cultural Studies 4: 225–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assor, Avi, Haya Kaplan, and Guy Roth. 2002. Choice Is Good, but Relevance Is Excellent: Autonomy-Enhancing and Suppressing Teacher Behaviours Predicting Students’ Engagement in Schoolwork. British Journal of Educational Psychology 72: 261–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumert, Jürgen, and Gundel Schümer. 2001. Familiäre Lebensverhältnisse, Bildungsbeteiligung Und Kompetenzerwerb. In PISA 2000: Basiskompetenzen Von Schülerinnen Und Schülern Im Internationalen Vergleich. Edited by Deutsches PISA-Konsortium. Opladen: Leske & Budrich, pp. 323–407. [Google Scholar]

- Baumert, Jürgen, Rainer Watermann, and Gundel Schümer. 2003. Disparitäten Der Bildungsbeteiligung Und Des Kompetenzerwerbs: Ein Institutionelles Und Individuelles Mediationsmodell. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 6: 46–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Rolf. 2003. Educational Expansion and Persistent Inequalities of Education: Utilising the Subjective Expected Utility Theory to Explain the Increasing Participation Rates in Upper Secondary School in the Federal Republic of Germany. European Sociological Review 19: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckert-Zieglschmid, Claudia, and Elmar Brähler. 2007. Der Leipziger Lebensstilfragebogen Für Jugendliche: Ein Instrument Zur Arbeit Mit Jugendlichen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Boudon, Raymond. 1974. Education, Opportunity, and Social Inequality: Changing Prospects in Western Society. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction. In Power and Ideology in Education. Edited by Jerome Karabel and Albert H. Halsey. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 487–511. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1979. The Inheritors: French Students and Their Relation to Culture. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1990. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Loic J. D. Wacquant. 2006. Reflexive Anthropologie. Frankfurt and Main: Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

- Brake, Anna, and Peter Büchner. 2012. Bildung Und Soziale Ungleichheit: Eine Einführung. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, Richard, and Jan O. Jonsson. 2000. A Multinominal Transition Model for Analyzing Educational Careers. American Sociological Review 65: 754–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, Richard, and Jan O. Jonsson. 2005. Inequality of Opportunity in Comparative Perspective: Recent Research on Educational Attainment and Social Mobility. Annual Review of Sociology 31: 223–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breen, Richard, and John H. Goldthorpe. 1997. Explaining Educational Differentials: Towards a Formal Rational Action Theory. Rationality and Society 9: 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, Anton A. 1996. Religionsunterricht: Besser Als Sein Ruf? Empirische Einblicke in Ein Umstrittenes Fach. Innsbruck: Tyrolia. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher, Anton A. 2000. Religionsunterricht Zwischen Lernfach Und Lebenshilfe: Eine Empirische Untersuchung Zum Katholischen Religionsunterricht in Der BRD. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [Google Scholar]

- Büchner, Peter, and Anna Brake, eds. 2006. Bildungsort Familie: Transmission Von Bildung Und Kultur Im Alltag Von Mehrgenerationenfamilien. Wiesbaden: Vs. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Chesebro, Joseph J., and James C. McCroskey. 2001. The Relationship of Teacher Clarity and Immediacy with Student State Receiver Apprehension, Affect and Cognitive Learning. Communication Education 50: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1992. A Power Primer. Psychological Bulletin 112: 155–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conger, Rand D., and Shannon J. Dogan. 2008. Social Class and Socialization in Families. In Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research. Edited by Joan E. Grusec and Paul D. Hastings. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 433–60. [Google Scholar]

- De Graaf, Nan D., Paul M. De Graaf, and Gerbert Kraaykamp. 2000. Parental Cultural Capital and Educational Attainment in the Netherlands: A Refinement of the Cultural Capital Perspective. Sociology of Education 73: 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hart, Joep. 1990. Impact of Religious Socialization in the Family. Journal of Empirical Theology 3: 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, Robert, and Jan O. Jonsson, eds. 1996. Can Education Be Equalized? The Swedish Case in Comparative Perspective. Oxford: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Leslie J. 1992. The Influence of Religion, Gender, and Social Class on Attitudes Toward School Among 11-Year-Olds in England. The Journal of Experimental Education 60: 339–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulljames, Peter, Harry M. Gibson, and Leslie J. Francis. 1991. Creationism, Scientism, Christianity and Science: A Study in Adolescent Attitudes. British Educational Research Journal 17: 171–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzeboom, Harry B. G., Paul M. De Graaf, and Donald J. Treiman. 1992. A Standard International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status. Social Science Research 21: 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaspard, Hanna, Anna-Lena Dicke, Barbara Flunger, Brigitte M. Brisson, Isabelle Häfner, Benjamin Nagengast, and Ulrich Trautwein. 2015. Fostering Adolescents’ Value Beliefs for Mathematics with a Relevance Intervention in the Classroom. Developmental Psychology 51: 1226–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geißler, Rainer. 2014. Die Sozialstruktur Deutschlands, 7th ed. Wiesbaden: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Harry M., Leslie J. Francis, and Paul R. Pearson. 1990. The Relationship Between Social Class and Attitude Towards Christianity Among Fourteen- and Fifteen-Year-Old Adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences 11: 631–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, Charles Y. 1962. On the Study of Religious Commitment. Religious Education 57: 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Goldthorpe, John H. 2007. “Cultural Capital”: Some Critical Observations. Sociologica 2: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Goldthorpe, John H. 2010. Analysing Social Inequality: A Critique of Two Recent Contributions from Economic and Epidemiology. European Sociological Review 26: 731–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grümme, Bernhard. 2017. Educational Justice Due to More Education? Requests for a Solution Strategy. Education Sciences 7: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grümme, Bernhard. 2021. Enlightened Heterogeneity: Religious Education Facing the Challenges of Educational Inequity. Religions 12: 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundmann, Matthias, Daniel Dravenau, Uwe H. Bittlingmayer, and Wolfgang Edelstein, eds. 2006. Handlungsbefähigung Und Milieu: Zur Analyse Milieuspezifischer Alltagspraktiken Und Ihrer Ungleichheitsrelevanz. Münster: LIT. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, John A. C. 2009. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Michelle, Robert Erikson, John H. Goldthorpe, and Meir Yaish. 2007. Primary and Secondary Effects in Class Differentials in Educational Attainment. Acta Sociologica 50: 211–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, Mads Meier. 2011. Does Cultural Capital Really Affect Academic Achievement? New Evidence from Combined Sibling and Panel Data. Sociology of Education 84: 281–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungbauer-Gans, Monika. 2004. Einfluss Des Sozialen Und Kulturellen Kapitals Auf Die Lesekompetenz: Ein Vergleich Der PISA 2000-Daten Aus Deutschland, Frankreich Und Der Schweiz. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 33: 375–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein-Heßling, Johannes, and Matthias Jerusalem. 2002. Alltagsrelevanz Von Unterrichtsinhalten. In Skalendokumentation Der Lehrer- Und Schülerskalen Des Projektes „Sicher Und Gesund in Der Schule". Edited by Matthias Jerusalem, Johannes Klein-Heßling and Inga Schlesinger. Berlin: Humboldt University Berlin, p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Klieme, Eckhard, and Katrin Rakoczy. 2003. Unterrichtsqualität Aus Schülerperspektive: Kulturspezifische Profile, Regionale Unterschiede Und Zusammenhänge Mit Effekten Von Unterricht. In PISA 2000: Ein Differenzierter Blick Auf Die Länder Der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Edited by Deutsches PISA-Konsortium. Opladen: Leske & Budrich, pp. 333–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Rolf-Torsten. 2011. Abschied Von Bourdieu? Perspektiven Ungleichheitsbezogener Bildungsforschung. Studien zur Schul- und Bildungsforschung 39. Wiesbaden: Vs. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Kreckel, Reinhard. 1992. Politische Soziologie Der Sozialen Ungleichheit. Frankfurt and Main: Campus Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kunter, Mareike, Gundel Schümer, Cordula Artelt, Jürgen Baumert, Eckhard Klieme, Michael Neubrand, Manfred Prenzel, Ulrich Schiefele, Wolfgang Schneider, Petra Stanat, and et al. 2002. PISA 2000: Dokumentation Der Erhebungsinstrumente. Berlin: Max-Planck Institute for Human Development. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, Jeremy F. 2000. Pierre Bourdieu: A Critical Introduction. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau, Annette, and Elliot B. Weininger. 2003. Cultural Capital in Educational Research: A Critical Assessment. Theory and Society 32: 567–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, Edward C. 1971. On Perceiving the Relevance of Traditional Religion to Contemporary Issues. Review of Religious Research 13: 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Christopher A., Sharon M. Cruise, Mike Fearn, and Conor McGuckin. 2009. Religiosity of Female and Male Adolescents. In Youth in Europe III: An International Empirical Study about the Impact of Religion on Life Orientation. Edited by Hans-Georg Ziebertz, William K. Kay and Ulrich Riegel. Münster: LIT, pp. 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lipowsky, Frank. 2015. Unterricht. In Pädagogische Psychologie, 2nd ed. Edited by Elke Wild and Jens Möller. Berlin: Springer, pp. 69–105. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Todd F., James M. White, and Daniel Perlman. 2003. Religious Socialization: A Test of the Channeling Hypothesis of Parental Influence on Adolescent Faith Maturity. Journal of Adolescent Research 18: 169–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Scott M. 1996. An Interactive Model of Religiosity Inheritance: The Importance of Family Context. American Sociological Review 61: 858–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoff, Barbara, Leslie Moore, Behnosh Najafi, Amy Dexter, Maricela Correa-Chávez, and Jocelyn Solís. 2008. Children’s Development of Cultural Repertoires Through Participation in Everyday Routines and Practices. In Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research. Edited by Joan E. Grusec and Paul D. Hastings. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 490–515. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Steven, Leon J. Kamin, and Richard C. Lewontin. 1984. Not in Our Genes: Biology, Ideology and Human Nature. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Yves. 2012. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software 48: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schreier, Brigitte M., Anna-Lena Dicke, Hanna Gaspard, Isabelle Häfner, Barbara Flunger, Oliver Lüdtke, Benjamin Nagengast, and Ulrich Trautwein. 2014. Der Wert Der Mathematik Im Klassenzimmer: Die Bedeutung Relevanzbezogener Unterrichtsmerkmale Für Die Wertüberzeugungen Der Schülerinnen Und Schüler. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 17: 225–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavit, Yossi, and Hans-Peter Blossfeld, eds. 1993. Persistent Inequality: Changing Educational Attainment in Thirteen Countries. Boulder: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat, Darren. 2003. Religious Socialization: Sources of Influence and Influences of Agency. In Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Edited by Michele Dillon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 151–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöborg, Anders. 2013. Religious Education and Intercultural Understanding: Examining the Role of Religiosity for Upper Secondary Students’ Attitudes Towards RE. British Journal of Religious Education 35: 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocké, Volker. 2007. Explaining Educational Decision and Effects of Families’ Social Class Position: An Empirical Test of the Breen-Goldthorpe Model of Educational Attainment. European Sociological Review 23: 505–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanissaro, Phra Nicholas. 2012. Measuring Attitude Towards RE: Factoring Pupil Experience and Home Faith Background into Assessment. British Journal of Religious Education 34: 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unser, Alexander. 2014. Wie Kann Sich Religionspädagogik Von Bildungsgerechtigkeit Herausfordern Lassen? Eine Entgegnung Auf Judith Könemann. Religionspädagogische Beiträge 71: 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Unser, Alexander. 2016. Soziale Ungleichheiten Im Religionsunterricht: Eine Quantitativ-Empirische Untersuchung Mit Blick Auf Die Religionspädagogische Debatte Um Bildungsgerechtigkeit. In Gerechter Religionsunterricht? Religionspädagogische, Pädagogische Und Sozialethische Orientierungen. Edited by Bernhard Grümme and Thomas Schlag. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, pp. 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Unser, Alexander. 2018. Is Religious Experience Necessary for Interreligious Learning? An Empirical Critique of a Didactical Assumption. In Religious Experience and Experiencing Religion in Religious Education. Edited by Ulrich Riegel, Eva-Maria Leven and Fleming Dan. Waxmann-E-Books Religion und Religionspädagogik Volume 11. Münster: Waxmann, pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Unser, Alexander. 2019. Social Inequality and Interreligious Learning: An Empirical Analysis of Students’ Agency to Cope with Interreligious Learning Tasks. Vienna: LIT. [Google Scholar]

- van der Zee, Theo, Chris Hermans, and Cor Aarnoutse. 2006. Primary School Students’ Metacognitive Beliefs About Religious Education. Educational Research and Evaluation: An International Journal on Theory and Practice 12: 271–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zee, Theo, Chris Hermans, and Cor Aarnoutse. 2008. Influence of Students’ Characteristics and Feelings on Cognitive Achievement in Religious Education. Educational Research and Evaluation: An International Journal on Theory and Practice 14: 119–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vester, Michael. 2006. Die Ständische Kanalisierung Der Bildungschancen: Bildung Und Soziale Ungleichheit Zwischen Boudon Und Bourdieu. In Soziale Ungleichheit Im Bildungssystem: Eine Empirisch-Theoretische Bestandsaufnahme. Edited by Werner Georg. Konstanz: Herbert von Halem Verlag, pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Watermann, Rainer, and Jürgen Baumert. 2006. Entwicklung Eines Strukturmodells Zum Zusammenhang Zwischen Sozialer Herkunft Und Fachlichen Und Überfachlichen Kompetenzen: Befunde National Und International Vergleichender Analysen. In Herkunftsbedingte Disparitäten Im Bildungswesen: Differenzielle Bildungsprozesse Und Probleme Der Verteilungsgerechtigkeit. Edited by Jürgen Baumert, Petra Stanat and Rainer Watermann. Wiesbaden: Vs. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 61–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ziebertz, Hans-Georg. 2005. Models of Inter-Religious Learning: An Empirical Study in Germany. In Religion, Education and Adolescence: International Empirical Perspectives. Edited by Leslie J. Francis, M. Robbins and J. Astley. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, pp. 204–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ziebertz, Hans-Georg, and Ulrich Riegel. 2008. Letzte Sicherheiten: Eine Empirische Untersuchung Zu Weltbildern Jugendlicher. Freiburg i. Br.: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Ziebertz, Hans-Georg, Boris Kalbheim, and Ulrich Riegel. 2003. Religiöse Signaturen Heute: Ein Religionspädagogischer Beitrag Zur Empirischen Jugendforschung. Freiburg i. Br.: Herder. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).