Embodied Objects: Chūjōhime’s Hair Embroideries and the Transformation of the Female Body in Premodern Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Women’s Bodies and the Problems of Salvation

3. The Emergence of Hair Embroidery

4. The Legends of Chūjōhime

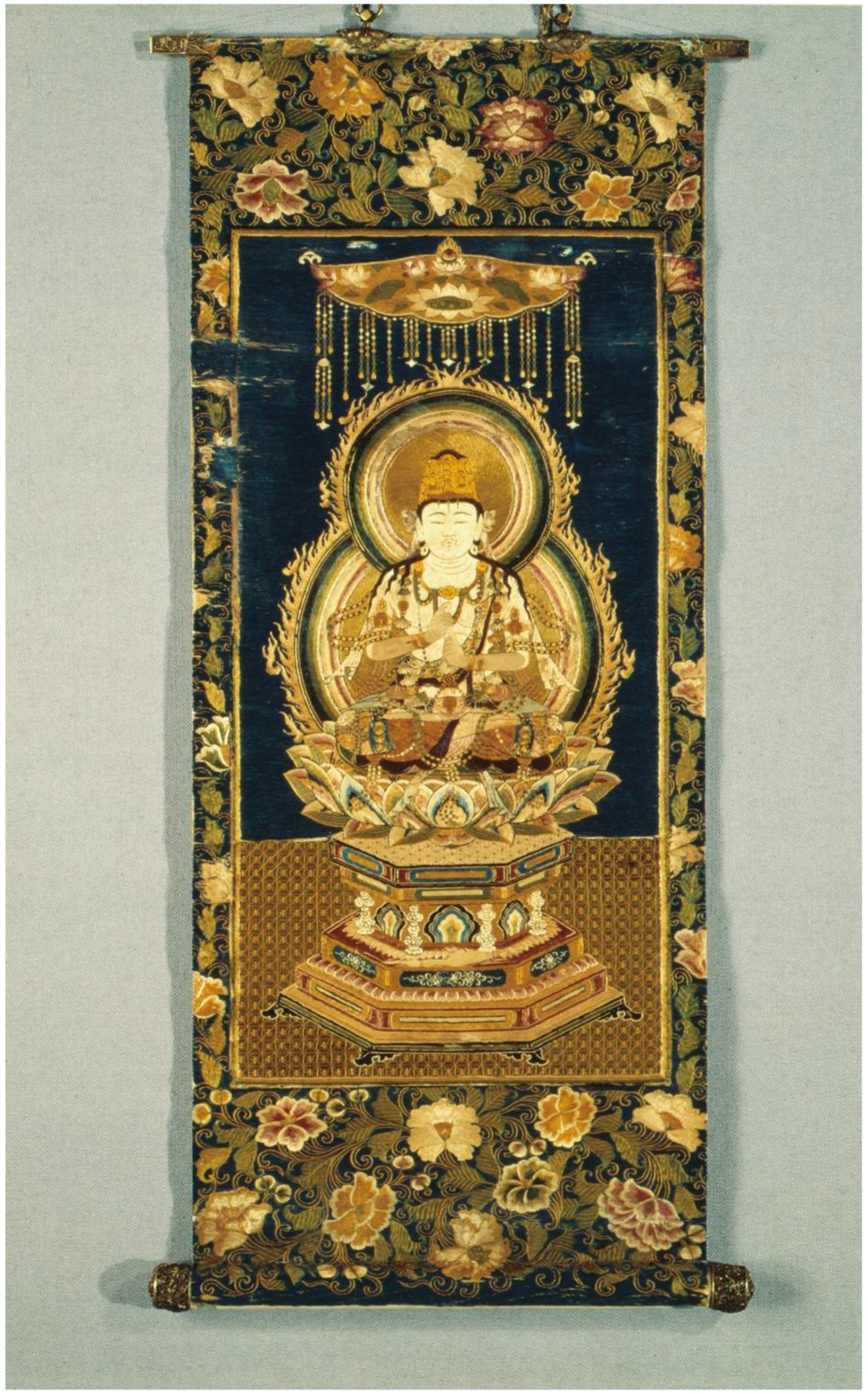

5. Chūjōhime’s Hair Embroideries

6. Embodied Images at Mt. Kōya

“Every sentient being has the Buddha nature. How could women be left out? This place of Buddhist practice is itself the Dharma World. How can we call another place [the Land of] Utmost Bliss? I hope that this act of blessing at this time by all means will secure Awakening in the next world… How can I not follow in the footsteps of the daughter of the Nāga King Sāgara? I will eradicate serious sins in order to seek the ninth level of rebirth in the Pure Land. I will revere the encompassing vows of the Buddha (Amida). The benefits of the Dharma world are limitless.”35

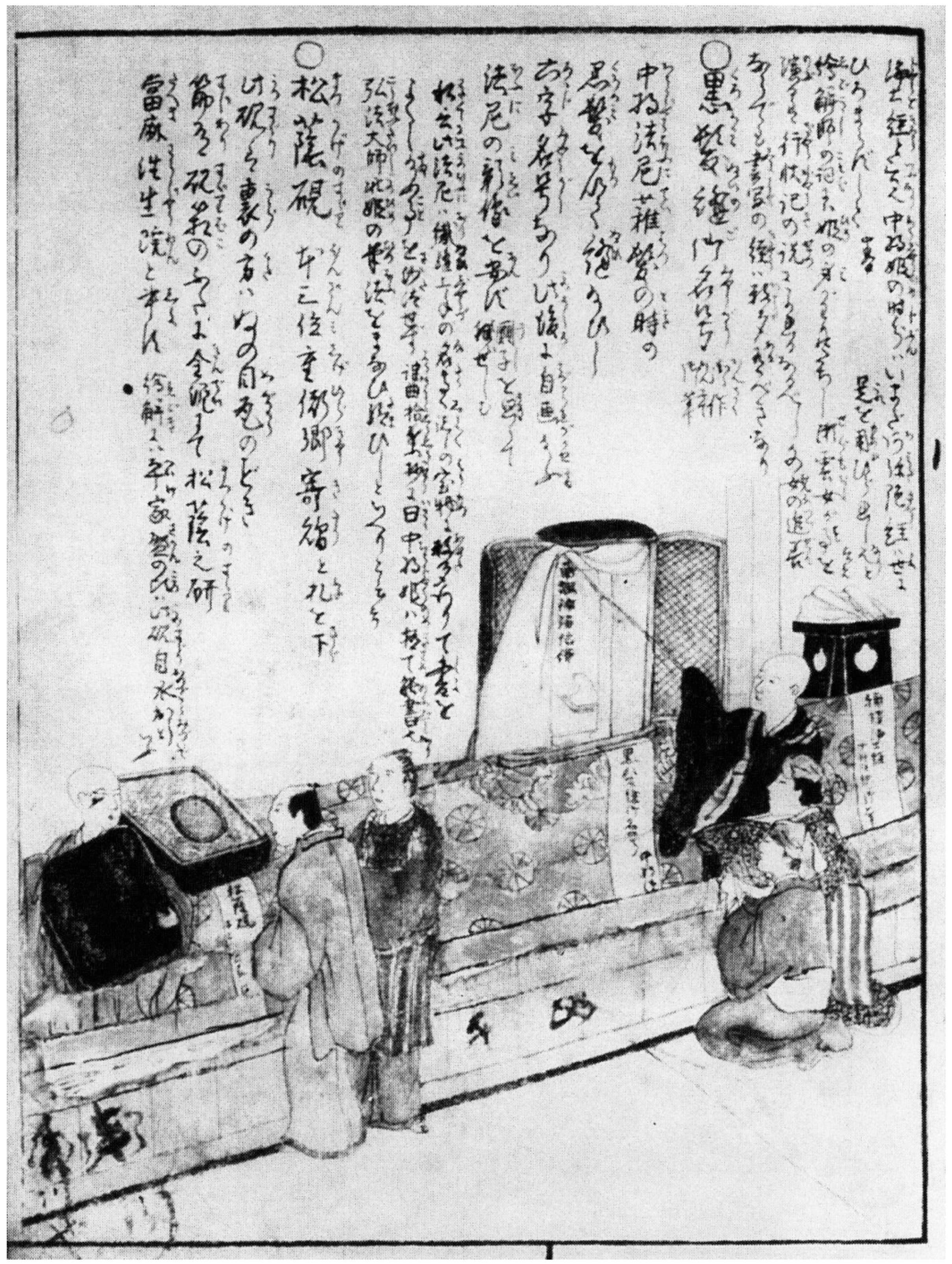

7. The Afterlives of Hair Embroidered Images

八月朔日より藤崎万日念仏堂ニ而旅僧参、曼荼羅継申候、此僧ハ上方より行脚之僧ニ候由、男女不寄老若、人之髪毛を集、其髪毛を集、其髪毛ニ而縫申候間、是奇代之名人と申候。参詣之男女髪を抜れながら難有と申候而銭ヲ出、拝み申候。“From the First of August, a traveling monk from Kamigata (Kyoto region) visited [Sesshūin] to create a [Taima] mandara. Hair was collected from both men and women, both the young and the old, because Kūnen wanted to use hair as the material for [the embroidery]. People referred to Kūnen as a master of conspiring wonderful feats. I witnessed male and female visitors alike, in the midst of prayer, offering coins and thanks, as their hairs were drawn [from their heads].”36

8. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | At least sixteen versions of the Blood Bowl Sutra circulated in Japan. The blood pools described in Chinese and early Japanese versions of the Blood Bowl Sutra initially only contained parturitive blood. By the seventeenth century, however, menstrual blood was also added to this polluted category (Takemi 1983, pp. 236–39; Williams 2005, pp. 125–28; Meeks 2020). |

| 2 | The other three categores of agency exhibited by religious women in Burke’s summary include “resistance agency” which is characterized by women’s desires to modify practices, “empowerment agency” which enables women to feel emotionally empowered by their practices, and “instrumental agency” in which material benefits are accrued through religious devotion. According to Burke, these categories are distinct but not mutually exclusive. (Burke 2012). |

| 3 | The five obstructions are also invoked by Śāriputra (Sharihotsu 舎利弗) in the Lotus Sutra as he remains deeply skeptical of women’s abilities to attain buddhahood due to their corporeal impurity (Moerman 2005, pp. 186–94). |

| 4 | The Blood Bowl Sutra was also used in Chinese Daoist practices and the earth god described here refers to a Daoist deity who later became popular in Japan (Yoshioka 1965, pp. 132–38). |

| 5 | Extant examples of the Kumano Heart Visualization and Ten World Mandala have fold lines which indicate that these paintings were not mounted like a hanging scroll but were carried along in traveling cases. These Kumana mandalas must have also been frequently used because most surviving examples are incredibly worn (Ruch 2002, pp. 566–75; Kaminishi 2006, pp. 137–63). |

| 6 | For an extensive iconographical analysis of the Kumano Heart Visualization and Ten World Mandala, see (Kuroda 2004, pp. 177–216). |

| 7 | This is an excerpt from an English translation of the Bussetsu Mokuren shōkyō ketsubon kyō 仏説目連正教血盆経, an undated woodblock printed version of a Blood Bowl Sutra discovered at Sōkenji 宗賢寺in Niigata Prefecture. |

| 8 | The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari 源氏物語) provides accounts of many aristocratic women participating in activities like embroidery as a method of self-fashioning and gift-giving. Court women embroidered pictures of famous places (meisho-e 名所絵) and lines from their favorite waka poems on their outermost garments to express their artistic sensibility and even gifted their textiles as mementos. The poetess Kenreimon’in 建礼門院 (1155–1213), for instance, embroidered her poems with purple floss onto a monk’s surplice (kesa 袈裟) and offered the garment to the poet, Fujiwara no Shunzei 藤原俊成 (1114–1204) (Genji monogatari 1997; Kenreimon’in ukyō no daibu shū 2001). |

| 9 | There are frequent references to the long hair of aristocratic women in premodern Japanese poetry and literature such as the early eleventh-century Tale of Genji. Women’s long thick hair was perceived as a sign of beauty, but it was also considered a material through which women’s desires and internal thoughts could be communicated. Disheveled hair, in particular, is associated with the passionate and unruly desires of women. The poet, Izumi Shikibu 和泉式部 (970–1030), for instance, deescribes her longing for a past lover though her unkempt hair 「黒髪の乱れも知らずうち臥せば・まづかきやりし人ぞ恋しき」 (Ebersole 1998, pp. 75–104; Pandey 2017, pp. 45–54). |

| 10 | 「かの髪をもつて、梵字を縫ひて、供養の願文の奥に、わが涙かかれとてしもなでざりし子の黒髪を見るぞ悲しき」 (Shasekishū 1943). |

| 11 | The Masukagami uses the term 「遊義門院の御ぐしにて」 to describe how Emperor Go-Uda accumulated Yūgimon’in’s hair. See (Masukagami 2007). |

| 12 | Known as tsuizen 追善, memorial services were performed not simply as events of commemoration but also as a place to transfer merit to the deceased by reciting prayers and bestowing precious offerings. Memorial services were performed at regular intervals every seventh day after a person’s death which culminated in the grand forty-ninth day service. The ceremony was followed then by a hundredth-day service, a first annual memorial service (ikkai ki 一回忌), and additional ceremonies continued to be performed each year on the anniversary of the individual’s death. For a study on death rituals in medieval Japan, see (Gerhart 2009). |

| 13 | The Azuma kagami was written between 1268 and 1301 to record the Kamakura administration’s policies and legitimize Hōjō rule. The text covers events from 1180 to 1266 and was compiled using a source of administrative documents, correspondences, reports, house records, diaries, and literary narratives. (Azuma kagami 1995). |

| 14 | The Azuma kagami states「 阿字一鋪(以御臺所御除髪被奉縫之)」 (Azuma kagami 1995). |

| 15 | Masako’s elder son, Yoriie, turned against his mother because he favored the advice of his wife’s family, the Hiki 比企 clan (Colcutt 1994). |

| 16 | This historical epic concerns Emperor Go-Daigo’s reassertion to the throne through the demise of the Hōjō shoguns from 1319 to 1367. There are multiple versions of the Taiheiki. The story concerning Toshimoto’s wife creating an embroidery is only featured in the Tenshō 天正 version (Taiheiki 1998). |

| 17 | On the significance of the forty-ninth day memorial service, see (Walter 2008, pp. 268–70). |

| 18 | The inscription on the back of the Welcoming Descent of Amida Triad embroidery from Shōchi’in’s 正智院 claims that this image embroidered with Chūjōhime’s hair is one of forty-eight embroideries made by her (Nara National Museum 2018, p. 274). |

| 19 | Scholars have four theories concerning the historical model for Chūjōhime, yet none have been proven as factual. One theory holds that Chūjōhime refers to the daughter of the nobleman, Fujiwara no Toyonari 藤原豊成 (704–765), while another claims that she is the wife of Toyonari, named Momoyoshi百能 (720–782), who commissioned a sculpture of Amida Buddha for the benefit of her family at Kōfukuji. A third theory states that she is Taima no Yamashiro 當麻山背, the daughter of Taima Mahirō 當麻真人老 who later married Prince Toneri 舎人親王 (676–735) and gave birth to the future Emperor Junnin 淳仁天皇 (733–765). For the fourth theory, scholars argue that she is Akirakeiko 明子 (829–900), who married Emperor Montoku 文徳天皇 (826–858) and gave birth to Empero Seiwa 清和天皇 (850–878). Akirakeiko was a fervent supporter of Enchin円珍 (814–891), a Tendai Buddhist monk who traveled to China and received several Buddhist embroideries that were commissioned by Empress Wu Zeitan 武則天 (624–705). It has been suggested that Enchin brought back the Taima mandara to Japan and Akirakeiko may have introduced this tapestry to the Japanese court (Tanaka 1970; Ten Grotenhuis 1980, pp. 174–77). |

| 20 | The sixteen meditations can be divided into two categories. The first category called the Thirteen Meditations includes features of the Pure Land that one should meditate upon at the moment of rebirth: (1) the sun (2) water (3) the ground (4) jeweled trees (5) the pond (6) pavilions (7) Amida’s Lotus Throne (8) the image of Amida Buddha (9) the body of Amida (10) the bodhisattva Kannon (11) the bodhisattva Seishi (12) the devotees achieving rebirth in the Pure Land and (13) smaller images of the Amida Buddha. The second category of the Sixteen Meditations includes a description of each of the three levels of rebirth. The Thirteen Meditations are depicted on the right panel while the levels of rebirth are illustrated in nine panels on the bottom register of the Taima mandara. |

| 21 | Texts from the Kamakura period that mention a female patron involved in the creation process of the Taima mandara are listed below in chronological order: Kenkyū gojunrei ki 建久御巡礼記 1191, Taima mandara chūki 當麻曼荼羅注記 1223, Taimadera ryūki 当麻寺流記 1231, Taimadera konryū no koto 當麻寺建立事 1237, Kokin mokurokushō 古今目録抄 1238, Yamatokuni Taimadera engi 大和國當麻寺縁起 1253, Kokin chakumonshū 古今著聞集 1254, Shishu hyakuin enshū 私聚百因縁集 1257, Washū Taimadera gokuraku mandara engi 和州當麻寺極楽曼荼羅縁起 1262, Zokukyō kunshō 續教訓抄 1270, Tohazugatari とはずがたり 1290, Ippen hijirie 一編聖絵 1299, and Genkō shakusho 元亨釈書 1322 (Ten Grotenhuis 1980, pp. 154–55). |

| 22 | These tales include the Chūjō hōnyo bikuni denki 中将法如比丘尼伝記 (1704), the Zenzen taiheiki 前々太平記 (1715), and the Chūjōhime gyōjōki 中将姫行状記 (1730). (Tanaka 2004, pp. 87–92). |

| 23 | There are two iconographical types of A-syllable icons based on whether the image is associated with the Diamond World Mandala or the Womb World Mandala. For a Sanskrit Seed-Syllable A embroidery referring to the Diamond World mandala, both the lotus pedestal and the syllable are depicted within a moon disk whereas for the Womb World mandala, the lotus pedestal rests outside of the moon disk. |

| 24 | Lotus flowers are an emblem of purity in a Buddhist context because, just as the lotus rises from the mud of the pond, so too, it was believed, that the being who achieves buddhahood rises above the impurity of this world. |

| 25 | The inscription states 「中将姫之御クシ之ケニテ御テツカラ御縫ヒ、蓮花其外ハ曼荼羅之糸ニテ御ヌイ也」 (Ishida and Nishimura 1964, p. 67). |

| 26 | The setsuwa tale, Shincho monjū 新著聞集 (1749 CE), and the Shinsen ōjōden 新撰往生伝, a collection of biographies of people who attained rebirth in the Amida Buddha’s Pure Land, discuss the practice of ingesting fibers from the image of the Taima mandara. The Mandarasan Tenshōji engi narabi hōmotsu raiyu 曼荼羅山天性寺縁起並宝物来由, a text concerning the origin of Tenshōji’s treasures, claims that the temple had three large grains and thirty-seven small grains of fibers that were extracted from the Tenshōji Taima mandara tapestry and then stored within the temple to be given to believers (Gangōji Bunkazai Kenkyūjo 1983, p. 103). |

| 27 | The inscription here uses the verb to stitch nui 縫, rather than the verb to make saku 作 that is commonly found on Buddhist images. This term saku can and is also used to refer to a patron not directly involved in the physical creation process of the image. By using the term nui instead, this text highlights Chūjōhime’s direct engagement with the object. |

| 28 | For a further discussion on the role of material culture in the spread of Chūjōhime’s cult see (Sekiyama 1985). |

| 29 | Scroll Eight of the Illustrated Biography of the Priest Ippen handscroll discusses Ippen’s visit to Taimadera (Komatsu 1981, pp. 223–26). |

| 30 | In Chūjōhime’s tales from the seventeenth century onwards, such as the Taima byakki 当麻白記 (written in 1614 and published in 1648), the Mirror for Women of Our Land (Honchō jokan 本朝女鑑; 1661 CE), a compilation of female biographies for the edification of women, and the Earlier Pre-Taiheiki (Zenzen taiheiki 前々太平記; 1715 CE), a tale concerning the events of the Nara-period court, Chūjōhime devotes herself to writing a thousand copies of the Sutra in Praise of the Pure Land (Shōsan jōdo kyō 称讃浄土経) for a full year before she encounters the Amida Buddha (Tanaka 2004, pp. 87–92). |

| 31 | Shōgon is a Japanese Buddhist term that can be translated into English as “pious adornment” and can be grouped into three types: (1) splendid things that adorn the Image Hall (2) splendid things that adorn the Buddha’s body and (3) virtues and good deeds with which Buddhas and bodhisattvas adorn themselves. The term originates from the Chinese word zhuangyan and combines two Ancient Indian concepts: alamkara meaning to “manifest the divine” and vyuha which means to “make perfect.” For a discussion on the soteriological benefits of shōgon, see (Mochizuki bukkyō daijiten 1958). |

| 32 | For sources concerning ritual practices related to the nenbutsu, see (Stone 2004, pp. 77–119). |

| 33 | An inscription on Shōchi’in’s Sanskrit Seed-Syllable A hair embroidery attributed to Chūjōhime, claims that this image had to be repaired and remounted in 1658. Shōchi’in owns another myōgō hair embroidery attributed to Chūjōhime that was also remounted by the same craftsmen (hyōgushi 表具師) five years later in 1663. |

| 34 | The doctrine of nonduality in the Vimalakirti Sutra (Yuimakyō 維摩経) describes this non-binary identity and claims that there is neither an absolute male nor absolute female identity. For a brief English translation and further discussion on this text, see (Kimbrough 2008, p. 195; Chūjōhime no honji 2002). |

| 35 | English translation of the Prayers for the dedication of Bodaishin’in Temple (Bodaishi’in kuyō ganmon 菩提心院供養願文) (Lindsay 2012, pp. 163–64). |

| 36 | English translation by author. |

| 37 | The English translation comes from the following sentence, “此因縁によりて先立父母は浄土に往生し、残し子孫は寿命長生ならん” |

References

Primary Sources

Genji monogatari 源氏物語. 1993. Shin Nihon koten bungaku taikei 新日本古典文学大系. Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, vol. 19.Secondary Sources

- Abé, Ryūichi. 2015. Revisiting the Dragon Princess: Her Role in Medieval Engi Stories and Their Implications in Reading the Lotus Sutra. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 42: 27–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambros, Barbara. 2008. Emplacing a Pilgrimage: The Ōyama Cult and Regional Religion in Early Modern Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ambros, Barbara. 2015. Women in Japanese Religions. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Azuma kagami 吾妻鏡. 1995. Kokushi taikei 国史大系. Tokyo: Yoshikawa kōbunkan. [Google Scholar]

- Benn, James A. 2007. Burning for the Buddha: Self-Immolation in Chinese Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bogel, Cynthea. 2009. With a Single Glance: Buddhist Icon and Early Mikkyō Vision. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brinker, Helmut. 2011. Secrets of the Sacred: Empowering Buddhist Images in Clear, in Code, and in Cache. Seattle: Spencer Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Kelsy C. 2012. Women’s Agency in Gender-Traditional Religions: A Review of Four Approaches. Sociology Compass 6: 122–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, Susan L. 2009. Marketing Health and Beauty: Advertising, Medicine, and the Modern Body in Meiji-Taisho Japan. In East Asian Visual Culture from the Treaty Ports to World War II. Edited by Hans Thomsen and Jennifer Purtle. Chicago: Paragon Books, pp. 173–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chūjōhime no honji 中将姫本地. 2002. Shinpen Nihon koten bungaku zenshū 新編日本文学. Tokyo: Shōgakukan. [Google Scholar]

- Colcutt, Martin. 1994. Religion in the Formation of the Kamakura Bakufu: As Seen through the ‘Azuma kagami’. Japan Review 5: 55–86. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1990. The Logic of Sense. Edited by Constantin V. Bounda. Translated by Mark Lester. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ebersole, Gary L. 1998. ‘Long Black Hair Like a Seat Cushion’: Hair Symbolism in Japanese Popular Religion. In Hair: Its Power and Meaning in Asian Cultures. Edited by Alf Hiltebeitel and Barbara D. Miller. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 75–104. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, Bernard. 2003. The Power of Denial. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gangōji Bunkazai Kenkyūjo 元興寺文化財研究所. 1983. Chūjōhime setsuwa no chōsa kenkyū hōkokusho 中将姫説話の調査研究報告書. Nara: Gangōji Bunkazai Kenkyūjo. [Google Scholar]

- Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: New York: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart, Karen. 2009. The Material Culture of Death in Medieval Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart, Karen, ed. 2018. Women, Rites, and Ritual Objects in Premodern Japan. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Glassman, Hank. 2004. ‘Show Me the Place Where My Mother Is!’ Chūjōhime, Preaching, and Relics in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan. In Approaching the Land of Bliss: Religious Praxis in the Cult of Amitābha. Edited by Richard K. Payne and Kenneth K. Tanaka. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 139–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara, Tatsuo 萩原龍夫. 1983. Miko to bukkyōshi: Kumano bikuni no shimei to tenkai 巫女と仏教史:熊野比丘尼の使命と展開. Tokyo: Yoshikawa kōbunkan. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, Cynthia. 2017. The Reliquary Effect: Enshrining the Sacred Object. London: Reaktion Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, Masahiko 林雅彦. 1995. Edo o itoite, jōdo e mairamu: Bukkyō bungaku ron 穢土を厭ひて浄土へ参らむ:仏教文学論. Tokyo: Meicho shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Hioki, Atsuko 日沖敦子. 2010. Taima mandara to Chūjōhime 当麻曼荼羅と中将姫. Tokyo: Bensei shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa, Caroline. 2013. Hell-Bent for Heaven in Tateyama Mandara: Painting and Religious Practice at a Japanese Mountain. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, Ian. 2012. Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships between Humans and Things. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, Nam-Lin. 2009. Invitation to the Secret Buddha of Zenkōji Kaichō and Religious Culture in Early Modern Japan. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36: 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, Tim. 2007. Materials against Materiality. Archaeological Dialogues 14: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, Tim. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge, and Description. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, Mosaku 石田茂作, and Hyōbu Nishimura 西村兵部. 1964. Shūbutsu 繍佛. Tokyo: Kadokawa. [Google Scholar]

- Itō, Shinji 伊藤信二. 2012. Chūsei shūbutsu no ‘shōgon yōshiki’ ni tsuite 中世繍仏の「荘厳様式」について. In Yōshikiron: Sutairu to mōdo no bunseki 様式論:スタイルとモードの分析. Edited by Hayashi On. Tokyo: Chikurinsha, pp. 390–407. [Google Scholar]

- Jakushōdō kokkyōshū: Jakushōdō kokkyō zokushū 寂照堂谷響集:寂照堂谷響續集. 1912. Dai Nihon bukkyō zensho 大日本文教全書. By Unshō (1614–1693). Tokyo: Bussho kankokai, vol. 149. [Google Scholar]

- Kamens, Edward. 1993. Dragon-Girl, Maidenflower, Buddha: The Transformation of a Waka Topos, ‘The Five Obstructions’. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 53: 389–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminishi, Ikumi. 2006. Explaining Pictures: Buddhist Propaganda and Etoki Storytelling in Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, Fusae. 2005. Behind the Sensationalism: Images of a Decaying Corpse in Japanese Buddhist Art. The Art Bulletin 87: 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenreimon’in ukyō no daibu shū 建礼門院右京大夫集. 2001. Shikishi Naishinnō shū, Kenreimon’in ukyō no daibu shū, Toshinari-kyō no Musume shū, Enshi 式子内親王集・建礼門院右京大夫集・俊成卿女集・艶詞. Waka Bungaku taikei vol. 23. Tokyo: Meiji Shoin. [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrough, Keller. 2008. Preachers, Poets, Women, and the Way: Izumi Shikibu and the Buddhist Literature of Medieval Japan. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, Shigemi 小松茂美. 1981. Ippen Shōnin eden一遍上人絵伝. Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, Hideo 黒田日出男. 2004. Kaiga shiryō de rekishi o yomu 絵画史料で歴史を読む. Tokyo: Chikuma shobō. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, Ethan Claude. 2012. Pilgrimage to the Sacred Traces of Kōyasan: Place and Devotion in late Heian Japan. Ph.D. thesis, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, Saba. 2004. Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Masukagami 増鏡. 2007. Kokushi taikei 国史大系. Tokyo: Yoshikawa kōbunkan, vol. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Meeks, Lori. 2010. Hokkeji and the Reemergence of Female Monastic Orders in Premodern Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meeks, Lori. 2020. Women and Buddhism in East Asian History: The Case of the Blood Bowl Sutra, Part II: Japan. Religion Compass 14: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki bukkyō daijiten 望月仏教大辞典. 1958. Edited by Mochizuki Shinkō 望月信亨. Tokyo: Sekai Seiten kankō kyōkai.

- Moerman, Max D. 2005. Localizing Paradise: Kumano Pilgrimage and the Religious Landscape of Premodern Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, Genzō 中野玄三. 2010. Raigōzu ronsō: “raigōzu no bijutsu” sairon 来迎図論争・「来迎図の美術」再論. In Hōhō to shiteno bukkyō bunkashi: Hito mono imēji no rekishigaku 方法としての仏教文化史:ヒト・モノ・イメージの歴史学. Edited by Nakano Genzō, Kasuya Makoto and Kamikawa Michio. Tokyo: Benseishuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Nara National Museum 奈良国立博物館. 2018. Ito no mihotoke: Kokuhō tuzureori Taima mandara to shūbutsu: Shūri kansei kinen tokubetsuten 糸のみほとけ:国宝綴織當麻曼荼羅と繍仏:修理完成記念特別展. Nara: Nara National Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiguchi, Junko 西口順子. 1987. Onna no Chikara: Kodai no Josei to Bukkyō 女の力:古代の女性と仏教. Tokyo: Heibonsha. [Google Scholar]

- Ohnuma, Reiko. 1998. The Gift of the Body and the Gift of the Dharma. History of Religions 37: 323–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, Rajyashree. 2017. Perfumed Sleeves and Tangled Hair: Body, Woman, and Desire in Medieval Japanese Narratives. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Richard K. 1998. Ajikan: Ritual and Meditation in the Shingon Tradition. In Re-Visioning “Kamakura” Buddhism. Edited by Richard K. Payne. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i, pp. 219–48. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Quitman E. 2003. Narrating the Salvation of the Elite: The Jōfukuji Paintings of the Ten Kings. Ars Orientalis 33: 120–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pradel, Chari. 2016. Fabricating the Tenjukoku Shūchō mandara and Prince Shōtoku’s Afterlives. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ruch, Barbara. 2002. Woman to Woman: Kumano bikuni Proselytizers in Medieval and Early Modern Japan. In Engendering Faith: Women and Buddhism in Premodern Japan. Edited by Barbara Ruch. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, pp. 537–80. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, Ernest Dale. 1960. Mūdra: A Study of Symbolic Gestures in Japanese Buddhist Sculpture. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sekiyama, Kazuo. 1985. Chūjōhime densetsu to Taima mandara. In Etoki. Edited by Etoki no kenkyū-kai. Tokyo: Yūseidō, pp. 127–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sharf, Robert H. 2011. The Buddha’s Finger Bones at Famensi and the Art of Chinese Esoteric Buddhism. The Art Bulletin 93: 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shasekishū 沙石集. 1943. Iwanami bunko 岩波文庫. Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, vols. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse. 2004. By the Power of One’s Last Nenbutsu: Deathbed Practices in Early Medieval Japan. In Approaching the Land of Bliss: Religious Praxis in the Cult of Amitābha. Edited by Richard Karl Payne and Kenneth Ken’ichi Tanaka. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 77–119. [Google Scholar]

- Sudō, Hirotoshi 須藤弘敏. 1989. Chūsonji konjikidō 中尊寺金色堂. In Chūsonji to Mōtsūji 中尊寺と毛越寺. Edited by Sudō Hirotoshi and Iwasa Mitsuharu. Osaka: Hoikusha, pp. 66–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sudō, Hirotoshi 須藤弘敏. 1994. Kōyasan Amida shōju raigōzu: Yume miru chikara 高野山阿弥陀聖衆来迎図:夢見る力. Tokyo: Heibonsha. [Google Scholar]

- Taiheiki 太平記. 1998. Shinpen Nihon koten bungaku zenshū 新編日本古典文学全集. Tokyo: Shōgakukan. [Google Scholar]

- Takemi, Momoko. 1983. ‘Menstruation Sutra’ Belief in Japan. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 10: 229–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Hisao 田中日佐夫. 1970. Chūjōhime densetsu o horu 中将姫伝説を掘る. Geijutsu Shinchō 芸術新潮 3: 120–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Takako 田中貴子. 1996. Seinaru onna: Saigū, megami, Chūjōhime 聖なる女:斎宮・女神・中将姫. Tokyo: Jinbun shoin. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Mie 田中美絵. 2004. Chūjōhime setsuwa no kinsei: Kangebon ‘Chūjōhime gyōjōki’ o jikuni 中将姫説話の近世・勧化本「中将姫行状記」を軸に. Denshō bungaku kenkyū 53: 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ten Grotenhuis, Elizabeth. 1980. The Revival of the Taima Mandala in Medieval Japan. Ph.D. thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ten Grotenhuis, Elizabeth. 2011. Collapsing the Distinction between Buddha and Believer: Human Hair in Japanese Esotericizing Embroideries. In Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. Edited by Charles Orzech and Richard Payne. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 876–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tonomura, Hitomi. 1990. Women and Inheritance in Japan’s Early Warrior Society. Comparative Studies in Society and History 32: 592–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Walter, Mariko Namba. 2008. The Structure of Japanese Buddhist Funerals. In Death and the Afterlife in Japanese Buddhism. Edited by Jacqueline I. Stone and Mariko Namba Walter. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 247–92. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Duncan Ryūken. 2005. The Other Side of Zen: A Social History of Sōtō Zen Buddhism in Tokugawa Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yiengpruskawan, Mimi Hall. 1993. The House of Gold: Fujiwara Kiyohira’s Konjikidō. Monumenta Nipponica 48: 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Kazuhiko. 2002. The Enlightenment of the Dragon King’s Daughter in the Lotus Sutra. In Engendering Faith: Women and Buddhism in Premodern Japan. Edited by Barbara Ruch. Translated by Margaret H. Childs. Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan, pp. 297–324. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka, Yoshitoyo 吉岡義豊. 1965. Dōkyō kenkyú 道教研究. Tokyo: Shōshinsha. [Google Scholar]

- Zōtanshū 雑談集. 1950. Koten bunko 古典文庫. Tokyo: Koten bunko, vol. 42. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wargula, C. Embodied Objects: Chūjōhime’s Hair Embroideries and the Transformation of the Female Body in Premodern Japan. Religions 2021, 12, 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090773

Wargula C. Embodied Objects: Chūjōhime’s Hair Embroideries and the Transformation of the Female Body in Premodern Japan. Religions. 2021; 12(9):773. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090773

Chicago/Turabian StyleWargula, Carolyn. 2021. "Embodied Objects: Chūjōhime’s Hair Embroideries and the Transformation of the Female Body in Premodern Japan" Religions 12, no. 9: 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090773

APA StyleWargula, C. (2021). Embodied Objects: Chūjōhime’s Hair Embroideries and the Transformation of the Female Body in Premodern Japan. Religions, 12(9), 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090773