Reconstructing Pure Land Buddhist Architecture in Ancient East Asia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptualization of the Pure Land in Buddhist Literature

For the attainment of welfare and happiness in both the worlds (ubhaya-loka-hita-sukha) and of Nirvana has erected this stone pillar (skambha), in the sixth year of (the reign of) King Siri-Virapurisadata, and the sixth fortnight of the rainy season, the 10th day. From the inscriptions of Nagarjunakonda Sites 1, 5, and 43.4

3. Embodiment of the Buddhist Pure Land in Transformation Tableaux

4. The Immortal Taoist Paradise and the Pure Land in Korean Society

5. Real World Representation of a Pure Land at Bulguksa Monastery

5.1. Common Views in Pure Land Scriptures

5.2. Architectural Characteristics of Transformation Tableaux

6. Construction of Pure Land Architecture: Bulguksa Monastery and Its Rituals vs. Hojoji and Byodoin Monasteries

6.1. Monastery Hojoji and Its Buddhist Rituals

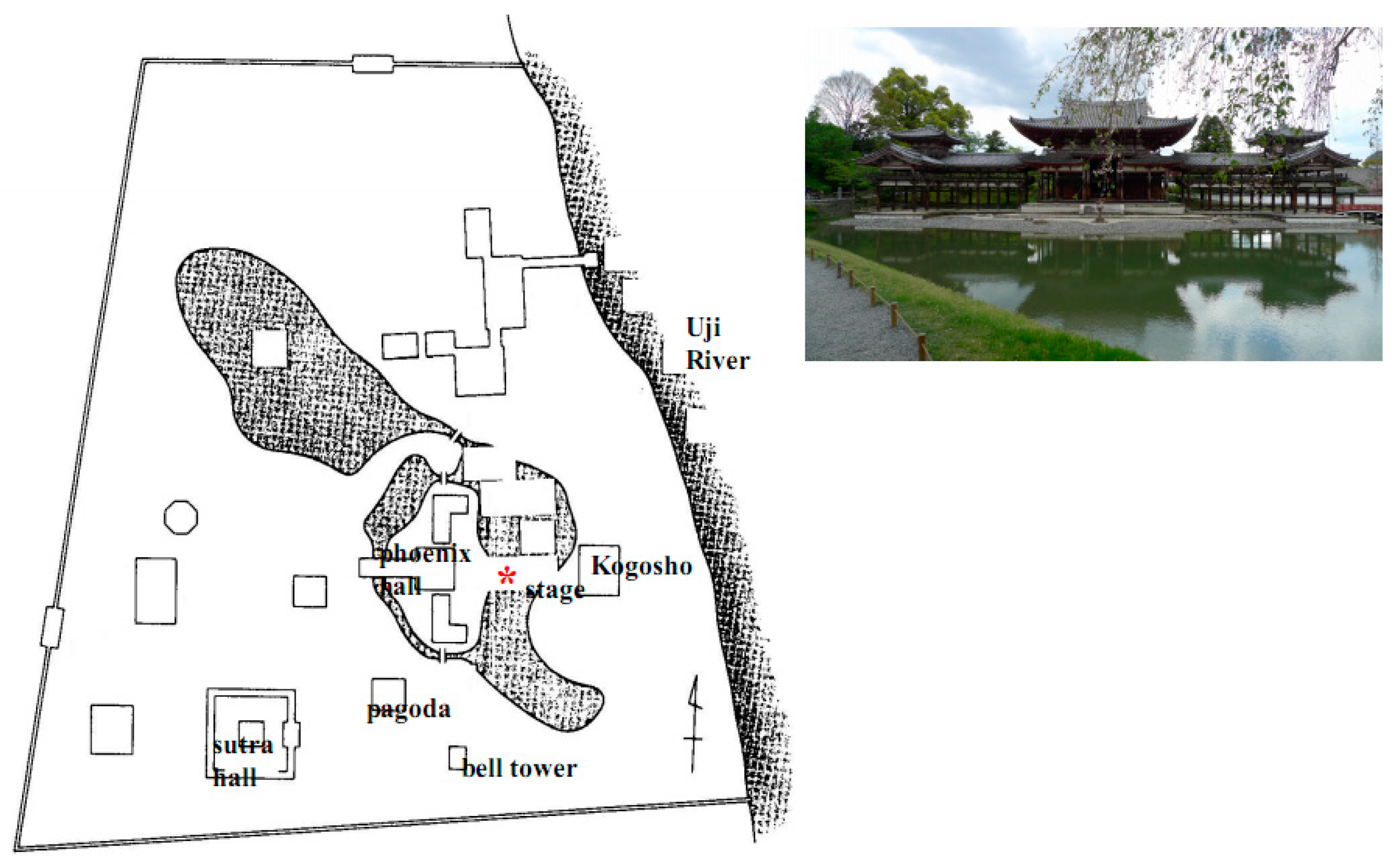

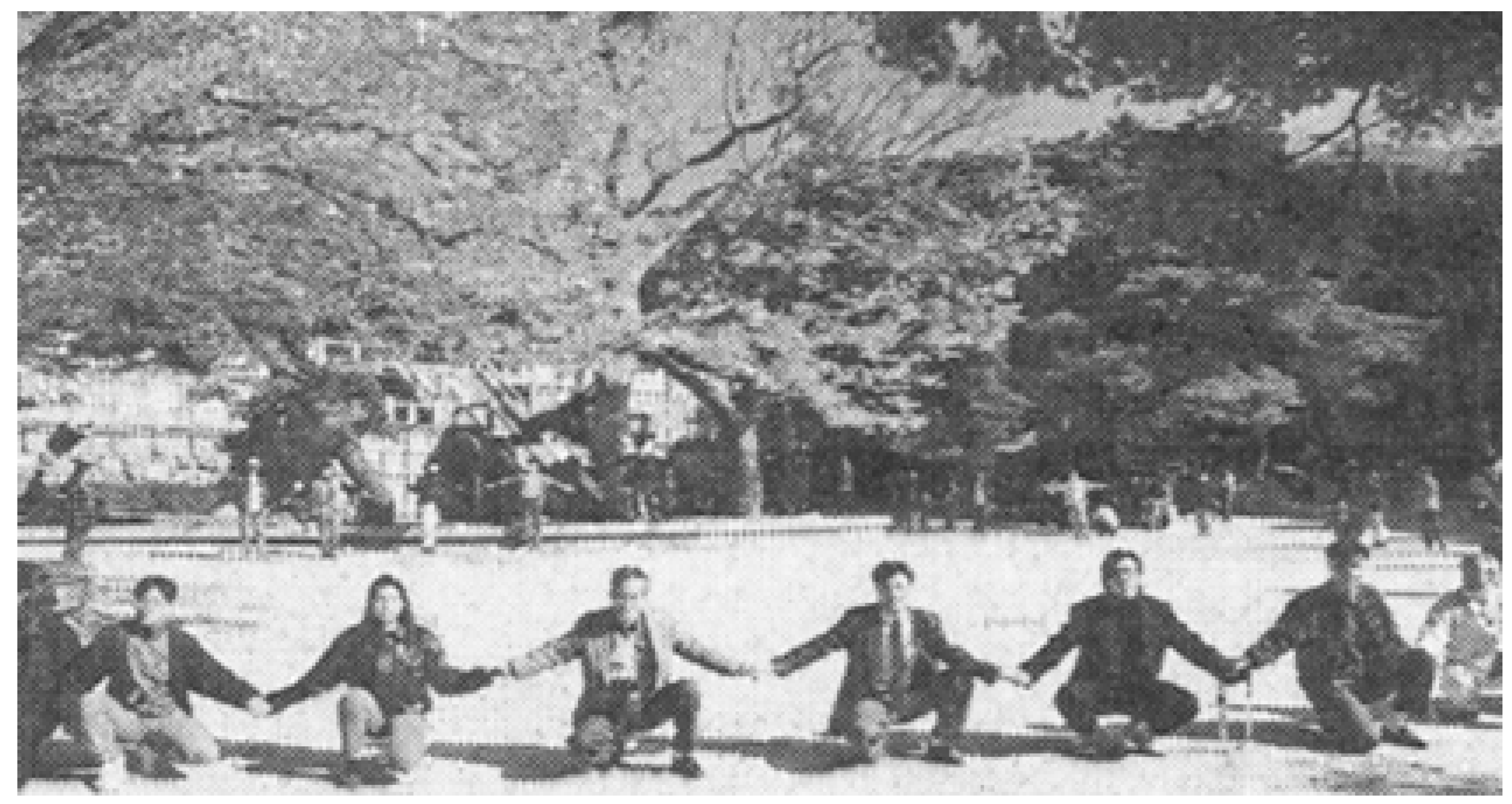

6.2. Byodoin Monastery and its Buddhist Rituals

6.3. Re-Interpreting Buddhist Rituals at Bulguksa Temple

7. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Four significant scriptures related with the Pure land tradition follow the Wuliang qingjing pingdengjue jing (Taisho12, no 361), the Foshuo amituo sanye sanfosalou guodu rendao jing (Taisho12, no 362), the Larger Sukhavati vyuha sutra (Taisho 12, no 360), and the Amitayurdhyana sutra (Taisho12, no 365). These Pure Land-related scriptures were translated from the Sanskrit version into the classical Chinese version, which influenced the establishment of Pure Land architecture in East Asia. These documents will be dealt with in detail in Section 5.1. |

| 2 | The Pure Land is interpreted as follows: Skt. Buddhaksetra; Ch. shatu, fotu, foguotu, foshentu; Kor. ch’altu, bulto, bulgukto, pulsint’o. The Pure Land is also translated into “jingtu” and “jile” for Sinification. It implies that the real world had been part of the existence of the living Buddha specifically in terms of sacred sites associated with key events in the Buddha’s life story; these places became important for traveling to get the merit (Bharati 1963, pp. 135–36). |

| 3 | The author referred to Tsukamoto’s two books. Tsukamoto re-organized the afore-mentioned inscriptions of other sites in India, including those of Nagarjunakonda sites (site 5 and site 43), and then compiled all Indian Buddhist inscriptions which were translated by Vogel, Sircar, Sarkar, Narasimha, Rama, Shizutani, and Sadakata. The first version of Nagarjunakonda inscriptions translated to English can be identified in Vogel’s works. (Vogel 1929–1930; Sircar 1963–1964; Tsukamoto 1986, 1996–1998; Rama 1967; Shizutani 1979; Sadakata 1994). |

| 4 | In particular, the well preserved text came from ayaka-pillar B5 (one of five pillars usually erected on the four cardinal directions), namely the fifth pillar on the south side of the great Buddhist Stupa at Site 1, Nagarjunakonda. This noted the gift of a stone pillar by the Mahadevi(Queen) Rudradharabhatarika, King Siri-Virapurisadata’s daughter from Ujjeni (Skt. Ujjayini), while the Mahachetiya (great stupa) was raised by the ladies, the Mahatalavaris, Chamtisitinika of (the family of) the Pukiyas. (Vogel 1929–1930, p. 19). |

| 5 | Nagarjuna wrote, “through proper honoring of stupas, you will become a Universal Monarch. Your glorious hands and feet marked with (a design of) wheels. Through the practices there are fame and happiness here, there is no fear now or at the point of death, in the next life happiness flourishes, therefore always observe the practices.” (Nagarjuna, Taisho 32 no 1656) Thus, we should note that the welfare and happiness of the entire world mean both the present world and posthumous future world as labeled on the inscriptions. Devotees at Nagarjunakonda and other areas have dreamt of the representation of the Pure Land or heavenly world in the real world from early Buddhist time. These epigraphical and literary proofs indicate that in ages past the monuments were crucial instruments for obtaining merit-transferring and merit-making devotees, and ultimately, for fulfilling Pure Land architecture. |

| 6 | The Amitabha not only means “measureless light,” but also “measureless wisdom.” In the Chinese translation, the jingtu, jile, and qingjing have a similar context. They refer to a pure, a no-ado, and an anle pleasure place, or an ideal nirvana. |

| 7 | The “qingjing” is similar in meaning to the “anle” and “jingtu,” which are frequently used in the Wuliangshoujing lun and Tan Luan’s Wuliangshoujing lunzhu. The term “jingtu” representing Amitabha’s religion is derived from the name of the Buddha in the Pingdeng juejing and Wuliang qingjing. |

| 8 | It was expressed in the text of the Ratnavali and the inscriptions of Nagarjunakonda (Walser 2005). |

| 9 | Afterwards, the ritual method was consistently followed by descendent monks. Xuanzang, a Tang monk, mediated upon the Bodhisattva Maitreya. He turned all his thoughts to the Heaven of the blessed one, praying ardently that he might be reborn there to pay homage to the Bodhisattva. His boat was once attacked by pirates who attempted to kill him as a sacrificial offering to the ferocious Sivaite goddess Durga, while a Silla monk, Wonhyo, proposed “there are three grades for people to cultivate the visualization, and the highest grades of people are those who either cultivate the Samadhi of Buddha visualization or repentance as their method of practice. In their present body, they will succeed in seeing Maitreya. According to the quality of their mind, the image they see will either be great or small.” (Sponberg and Hardacre 1988, pp. 94–95; Kitagawa 1988). |

| 10 | Lokasema’s translated texts in the second-century state the Buddha of the Ten Directions, “if one’s heart is focused on Amitabha one will be reborn in sukhavati, the Western Pure Land presided over by Amitabha.” Additionally, Huiyuan established a Buddhist center at Lushan, Jiangxi, and another at Xiangyang, Hubei. He described a miraculous sculpture at Xiangyang and a painting of the “shadow” or “reflection” of the Buddha (foyingxiang) at Lushan. The statue and picture might be related to meditation or visualization practices in the locales. |

| 11 | When Tanjie fell seriously ill, Daoan chanted continuously, the name of Maitreya Buddha never leaving his lips. Zhisheng (Taoan’s disciple), who waited on him in his illness, asked him why he did not want to be reborn in the Heaven of Peaceful Response (i.e., Amitabha’s paradise, sukhavati). Tanjie replied, “Together with the Reverend (Daoan) and eight others, I have vowed to be reborn in Tusita (i.e., Maitreya’s paradise). The Reverend, Daoan, and the others have already been born there, but I have not. That is why I have this wish” (Kieschnick 1997, p. 5). |

| 12 | “Dae Hwaeom Bulguksa birojanabulmun munsu bohyeon bosal chanbyeongseo is listed in the Bulguksa gogum changgi佛國寺古今歷代記. |

| 13 | The conquests of Asoka were realized through the imperial ideas of India. Through his strong espousal of the sangha communities, as well as the construction of 84,000 stupas all over the Jambudvipa, he was both a transformative body of the Buddha and a cakravartin (Strong 1989, p. 117). The cakravartin legends became an archetypal example of the Buddhist kingship, and were spread among several hagiographical works. |

| 14 | A similar record that the ruling class built a monument to protect his subjects appeared in an inscription that was manufactured for the repair works of the nine-story pagoda of Hwangnyongsa in the Silla period. The inscription writes, “Hitherto (The construction of the pagoda) has led to the peaceful and happy life of sovereign and subject 君臣安樂至今賴之.” As in the Hwangnyongsagucheungmoktap chaljubongi 皇龍寺九層木塔刹柱本記. in the 11th year (871) of Silla King Gyeongmun, the repair work began on a nine-story wooden pagoda at Hwangryongsa Monastery. In this process, Park Geo-Mul recorded the construction of the wooden Buddhist pagoda and repair process from 871 (the 11th regnal year of King Gyeongdeok) to 872 CE. |

| 15 | Korean Buddhism did not show political upheavals and heavily depended on the personal preferences of rulers, while at least four anti-Buddhist campaigns occurred in China in 446 (Northern Wei), 557 (Northern Zhou), 845 (Tang), and 955 (Later Zhou) in the contemporaneous period. |

| 16 | See the Gamsansa Seokjomireukbosaripsang Josanggi 甘山寺石造彌勒菩薩立像造像記. The inscription consists of 21 rows and 391 characters, which have been left on these images. The Taoist idea shows a teaching about the various disciplines for achieving “perfection” by becoming one with the unplanned rhythms of the universe called “the way” or “Tao,” in association with the faith of ancient East Asians who desired to become hermits in mountains or tall buildings after death (Gamsansa Seokjomireukbosaripsang Josanggi 720). |

| 17 | Recently, some scholars have argued that the completion of the main territory of a Buddha hall and Buddha pagodas had already been done before 742 CE, as determined by epigraphical evidence such as Bulguksa mugujeonggwangtap jungsugi 佛國寺無垢淨光塔重修記 (Bulguksa Mugujeonggwangtopjoongsugi 1024) and Bulguksa seoseoktap jungsu hyeongjigi 佛國寺西石塔重修形止記 (Bulguksa Seoseoktapjungsuhyeongjigi 1038). |

| 18 | Kim Daeseong and his father, Kim Munryang, of Samgukyusai, and Kim Daejeong and Kim Munryang of Samguksagi are the same person. Kim Munryang served as Prime Minister from 706–711 under King Seongdeok, and Kim Dae jeong served as King Gyeongdeok from 745–750. |

| 19 | Bulguksa mugujeonggwangtap jungsugi, Bulguksa seoseok-tap jungsu hyeongjigi, and Bulguksa jungsu bosimyeong gongjungsomyoeonggi show that the original names of the pagodas were not Tathagata Prabutaratna and Tathagata Sakyamuni Pagodas at the time of the first construction. (Cheon 1996). |

| 20 | The larger Sukhavativyuha sutra (The Sutra on the Buddha of Eternal Life), translated from the Sanskrit by F. Max Mueller, edited by Richard St. Clair. Available on: https://www.nanputuo.com/npten/html/201203/2816073173499.html (accessed on 10 June 2021). |

| 21 | In order to make an argument about historic shifts in style at Dunhuang, I utilize the reference scheme developed by the Dunhuang Research Academy. The number within the parentheses pertains to the number of caves allocated in the following periods: early-Tang 618–704 (40), high-Tang 705–80 (81), mid-Tang 781–847 (46), late-Tang 848–906 (60), Five Dynasties 907–59, Song 960–1035, and Western Xia (Xi xia) 1036–1226 (Xiao 1989, p. 30). |

| 22 | In particular, the lotus pond is a reminder of the “nine levels of rebirth” in the Amitayurdhyana sutra or the “three types of persons to be reborn” in the Larger Sukhavati vyuha sutra. |

References

Primary Sources

Larger Sukhavati Vyuha Sutra佛說無量壽經. Taisho 12, no. 360.Wuliang Qingjingpingdengjuejing無量清淨平等覺經. Taisho 12, no. 361,Foshuo Amituo Sanye Sanfosalou Guodu Rendao Jing佛說阿彌陀三耶三佛薩樓佛檀過度人道經. Taisho 12, no. 362.Amitayurdhyana Sutra佛說觀無量壽佛經. Taisho 12, no. 365.Amitayurdhyana Sutra (Smaller Sukhavati vyuha sutra)佛說阿彌陀經. Taisho 12, no. 366.Pratyupannasamadhi Sutra Banzhou Sanmei Jing般舟三昧經. Taisho 13, no. 418Suvarnaprabhasa sutra金光明經 (Golden Light Sutra). Taisho 16, no. 663.Guannian Amituofo Xiangbai Sanmei Gonde Famen Jing觀念阿彌陀佛相海三昧功德法門 (Meritorious Methods of Contemplating Amitābha Buddha). Taisho 47, no. 1959.Saddharmapundarika妙法蓮華經(Lotus Sutra). Taisho 9 no 262.Nagarjuna, Paramārtha. Ratnavali 寶行王正論 (Precious Garland), Taisho 32 no 1656.Dae Hwaeomjong Bulguksa Birojana Munsu Boheon Bosal Chanbyeongseo大華嚴宗佛國寺毘盧遮那文殊普賢像讚幷序.(Gamsansa Seokjomireukbosaripsang Josanggi 720) Gamsansa Seokjomireukbosaripsang Josanggi, 720, 甘山寺石造彌勒菩薩立像造像記 (the Dedicatory Inscriptions (Josanggi) on the Amitabha Buddha and the Maitreya Bodhisattva statues of Gamsansa Temple).(Ilyeon 1281) Ilyeon, Samguk Yusa. 1281. 三國遺事 (Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms).(Kim 1145) Kim, Busik. 1145. Samguk Sagi 三國史記 (History of the Three Kingdoms).(Hwaram Doeun 1740) Hwaram Doeun. 1740. Bulguksa Gogeum Changgi 佛國寺古今創記 (Architectural History of Bulguksa).(Beopgyedogi Chongsurok 1254) Beopgyedogi Chongsurok. 1254. 法界圖記叢隨錄 (Collected Essentials of Records on the Dharma Diagram).(Koen [1169] 1965) Koen, Katsumi Kuroita. 1965. Fuso Ryakki Teio Hennenki 扶桑略記 帝王編年記. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan. First published 1169.(Matsumura and Yutaka 1965) Matsumura, Hiroji, and Yutaka Yamanaka. 1965. Eiga Monogatari榮花物語. Nippon koten bungaku taikei 76, Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, a story from 1028 to 1107.(Fujiwara 1965) Fujiwara, Munetada. 1965. Chuyuki中右記, Zoho Shiryo Taisei Kankokai, Kyoto: Rinsen Shoten, Fujiwara’s diary written from 1087 to 1138.(Bulguksa Jungsubosimyeong Gongjungsomyoeonggi 1038) Bulguksa Jungsubosimyeong Gongjungsomyoeonggi. 1038. 佛國寺塔重修布施名公衆僧小名記 (Document on the Name of Almsgiving from Laypeople and Monks of Bulguksa).(Bulguksa Mugujeonggwangtopjoongsugi 1024) Bulguksa Mugujeonggwangtopjoongsugi. 1024. 佛國寺無垢淨光塔重修記 (Repair Report of Rasmivimalavisuddhaprabhadharani Cetiya (Endless Untainted Light Pagoda) of Bulguksa Monastery).(Bulguksa Seoseoktapjungsuhyeongjigi 1038) Bulguksa Seoseoktapjungsuhyeongjigi. 1038. 佛國寺西石塔重修形止記 (Repair Report of the West Stone Pagoda of Bulguksa Monastery).(Hwanglyongsa Gucheungmogtab Geumdongchaljubongi 871) Hwanglyongsa Gucheungmogtab Geumdongchaljubongi 皇龍寺九層木塔刹柱本記. 871. (Basic Annals concerning the Pillar of the Nine-story Pagoda of Hwangnyong-sa).(Gukgagirokwon 1918–1924) Gukgagirokwon 1918–1924, Restoration Plans of Monastery Bulguksa, Gukgagirokwon(National Archive of Korea).Anonymous, n.d. Western Paradise of the Buddha Amitabha(Northern Qi dynasty, 550-577), Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Available online: https://asia.si.edu/object/F1921.2/ (accessed on 26 June 2021).Secondary Sources

- Apte, Vaman Shivaram. 1957–1959. A Revised and Enlarged Edition of Prin. V. S. Apte’s The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Poona: Prasad Prakashan, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Bharati, Agehananda. 1963. Pilgrimage in the Indian Tradition. History of Religions 3: 135–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, David W. 1977. Chinese Buddhist Interpretations of the Pure Lands. In Buddhist and Taoist Studies I. Edited by Michael Saso and David Chappell. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, Haebong. 1996. Mugujeonggwangdaranigyeong無垢淨光大陀羅尼經, Hanguk Minjok Munhwa Daebaekgwasajeon. Available online: http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Item/E0018943 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Corless, Roger J. 1982. T’an-Luan: Taoist Sage and Buddhist Bodhisattva. Buddhist and Taoist Practice in Medieval Chinese Society. Edited by David W. Chappell. Buddhist and Taoist Studies 2. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, Kotatsu. 1970. Genshi Jodo Shiso No Kenkyu. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, pp. 141–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Edward Twitchell. 1966. The Hidden Dimension. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Jeongho. 2003. Silla seoktabui ijunggidan balsaengwonine daehan gochal (The Origination Cause of Double Deck Foundation of the Silla Stone Pagodas). Silla Munhwa-je Haksul Balpyohoe Nonmunjib 24: 61–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hanawa, Hokiichi. 1951. Zoku Gunshoruiju. Tokyo: Zoku Gunshoruiju Kanseikai, vol. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, John. 1999. Questions of influence in Chinese art history. Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 35: 240–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Poay-Peng. 1995. Paradise on earth: Architectural depiction in pure land illustrations of high Tang caves at Dunhuang. Oriental Art 41: 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto, Yutaka. 1978. Bukkyo Setsuwa no Densho to Shinko. Tokyo: Kaimei Shoin, pp. 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Katsuki, Genichiro. 1992. Tonko Mogaoku dai 220ku amida joudohenzo zu ko. Bukkyo Geijutsu 202: 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kieschnick, John. 1997. The Eminent Monk: Buddhist Ideals in Medieval Chinese Hagiography. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Young Jae. 2011. Architectural Representation of the Pure Land: Constructing the Cosmopolitan Temple Complex From Nagarjunakonda to Bulguksa. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Young Jae. 2018. The Origin and Development of the Pavilion at the Contact Points of the East and the West–Between Asia Minor and Indian Subcontinent. The Eastern Art 38: 34–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, Joseph M. 1988. “The Many Faces of Maitreya”. In Maitreya, the Future Buddha. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa, Harumura, and Bun’ei Tsunoda. 1969. Sadaie ason ki, Rekidai Zanketsu Nikki. Kyōto-shi: Rinsen Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Baijin. 2007. Tang Fengjian Zhuyingzao. Beijing: Zhongguo Jianzhu Gongye Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonell, Arthur Anthony. 1929. A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary with Transliteration, Accentuation, and Etymological Analysis Throughout. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, Victor H. 1986. Records of Transformation Tableaux (pienhsiang). T’oung Pao 72: 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamoto, Tsuneyori. 1965. Sakeiki左経記, Zoho ShiryoTaisei Kankokai 6. Kyoto: Rinsen Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsumori, Masashi. 1999. Kodai bukkyou jiin no reihai kuukan to reihai seki. In Bukkyo Bijutsu No Kenkyu. Kyoto: Jishosha, pp. 185–212. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, Seichi, and Nagahiro Toshio. 1941. Kanan Rakuyo Ryumon Sekkutsu No Kenkyu (Longmen Caves’ Study in Luoyang, Henan). Tokyo: Zauho kankoka. [Google Scholar]

- Motonaka, Makoto. 1994. Nippon Kodai No Teien to Keikan. Tokyo: Yoshikawako Bunkan. [Google Scholar]

- Munhwagongbobu, Munhwajaegwalliguk. 1976. Bulguksa Bokwongongsa bogoseo (Restoration Work Report of Bulguksa). Gyeongju: Gyeongju City Government. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Hajime. 1975. Jodo Kyoten no Seiritsu Nendai to Chiiki. In Jodo Sanbukyo. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Ota, Hirotaro. 1988. Byodo-in Taikan: Dai 1 Kan Kenchiku. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Ota, Seiroku. 2010. Shindenzukuri No Kenkyu. Shinsoban. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan, pp. 149–77, 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Pas, Julian. 1987. Dimensions in the Life and Thought of Shan-tao(613–681). In Buddhist and Taoist Practice in Medieval Chinese Society. Edited by David W. Chappell. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pyyhtinen, Olli. 2014. The Gift and Its Paradoxes: Beyond Mauss. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Rama, Rao. 1967. Inscriptions of the Andhradesa. 2 vols. Sri Venkatesvara University Historical Series, No. 5. Tirupati: Sri Venkatesvara University. [Google Scholar]

- Sadakata, Akira. 1994. Tōkai Daigaku kiyō Bungakubu 61 (Bulletin of the Faculty of Literature of Tokai University). Available online: https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/4227370 (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Shimizu, Hiroshi. 1986a. Hojo-ji no garan to sono seikaku. Nippon Kenchiku Gakkai Keikaku Kei Ronbun Houkoku Shu 363: 158–67. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, Hiroshi. 1986b. Byodo-in no garan to sono seikaku. Tokyokougei Daigaku Kougakubu Kiyou 8: 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Shizutani, Masao. 1979. Indo Bukkyō Himei Mokuroku (Catalog of Indian Buddha Monument Inscription). Kyōto: Heirakuji Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Sircar, D. C. 1963–1964. More Inscriptions from Nagrjunakonda. Epigraphia Indica XXXV: 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sponberg, Alan, and Helen Hardacre, eds. 1988. Maitreya, the Future Buddha. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama, Shinzo. 1981. Inka Kenchiku No Kenkyu. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Machi Koubun Kan. [Google Scholar]

- Tatara, Miharu, Andreas Hamacher, and Shirai Hikoe. 1998. Jodo teien no kuukan kousei nikansuru kousatsu: Hojo-ji oyobi Byodo-in o jirei toshite (Consideration on the spatial composition of the Pure Land Garden: Hojoji Temple and Byodoin Temple). Chiba Daigaku Engei Gakubu Gakujutsu Houkoku 52: 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tokyoteikokudaigaku Kokadaigaku. 1904. Kankoku kenchiku chōsa hōkoku韓國建築調査報告 (Research Report of Korean Architecture). Tokyo: Tokyo Teikoku Daigaku. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, Keisho. 1986. Hokekyo No Seiritsu to Haikei: Indo Bunka to Daijo Bukkyo 法華経の成立と 背景:インド文化と大乗仏教 (Formation and the Background of the Lotus Sutra: Indian Culture and Mahayanist Buddhism). Tokyo: Kosei. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, Keisho. 1996–1998. Indo Bukkyo Himei no kenkyuインド仏教碑銘の研究 (The Study of the Buddhism Epigraph). 2 vols. Kyoto: Heirakuji. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, J. P. 1929–1930. No. 1 Prakrit Inscriptions from a Buddhist Site at Nagarjunikonda. In Epigraphia Indica, XX ed. Hiranand Shastri and New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Walser, Joseph. 2005. Nagarjuna in Context: Mahayana Buddhism and Early Indian Culture. Columbia: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Dorothy C. 1998. Four Sichuan Buddhist Steles and the Beginnings of Pure Land Imagery in China. Archives of Asian Art 51: 56–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Dorothy C. 2008. The Mapping of Sacred Space Images of Buddhist Cosmographies in Medieval China. In The Journey of Maps and Images on the Silk Road. Edited by Andreas Kaplony and Philippe Foret. Leiden: E. J. Brill, pp. 66–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Arthur. 1948. Fo-t’u-teng, a Biography. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 11: 321–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Hung. 1992a. Reborn in Paradise: A Case Study of Dunhuang Sutra Painting and its Religious, Ritual and Artistic Context. Orientations 23: 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung. 1992b. What is Bianxiang? On the Relationship between Dunhuang Art and Dunhuang Literature. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 52: 111–92. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Mo. 1989. Dunhuang Jianzhu Yanjiu (Research on Dunhuang Architecture). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Chaohua. 1987. Er Ya Jin Zhu 爾雅今注. Tianjin: Nan Kai Da Xue Chu Ban She. [Google Scholar]

- Yijing, I.-Tsing, and J. Takakusu. 1970. A Record of the Buddhist Religion as Practiced in India and the Malay Archipelago. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher, Erik. 1959. The Buddhist Conquest of China. Leiden: E. J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

| Height (H) | Height of the Pagoda’s Foundation: A | Height of the Main Hall’s Foundation: B | Height Difference between A and B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bunhwangsa 634 CE | 1.50 | unknown | unknown | |

| Hwangnyongsa 645 CE | 1.60 | 1.10 | 0.50 (A/B = 1.45) | Buddha dais: 0.5. |

| Sacheongwangsa 679 CE | 1.50 | 1.15 | 0.35 (A/B = 1.30) | |

| Gameunsa 682 CE | 2.58 | 1.90 | 0.70 (A/B = 1.35) | Height of underground channels: 0.60 |

| Mangdeoksa 684 CE (or 679 CE) | 1.26 | 0.95 | 0.31 (A/B = 1.32) | |

| Bulguksa East Pagoda (EP) 742 CE | 1.97 | 1.53 Image (H): 1.66 Dais (H): 1.60 Total height: 4.79 | 0.44 (A/B = 1.29) | Height(E) to the platform above column network from the ground level: 4.59 Height(W) to the heavenly chamber from the ground level: 5.11 |

| Bulguksa West Pagoda (WP) 742 CE | 2.44 | 0.91 (A/B = 1.59) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y.-J. Reconstructing Pure Land Buddhist Architecture in Ancient East Asia. Religions 2021, 12, 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090764

Kim Y-J. Reconstructing Pure Land Buddhist Architecture in Ancient East Asia. Religions. 2021; 12(9):764. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090764

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Young-Jae. 2021. "Reconstructing Pure Land Buddhist Architecture in Ancient East Asia" Religions 12, no. 9: 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090764

APA StyleKim, Y.-J. (2021). Reconstructing Pure Land Buddhist Architecture in Ancient East Asia. Religions, 12(9), 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090764