Secular Dimensions of the Aśoka Stūpa from the Changgan Monastery of the Song Dynasty

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The History of the Site of the Changgan Monastery

3. The Association between the Aśoka Cult and Relic Worship at the Site

4. The Crypt of the Song Changgan Monastery

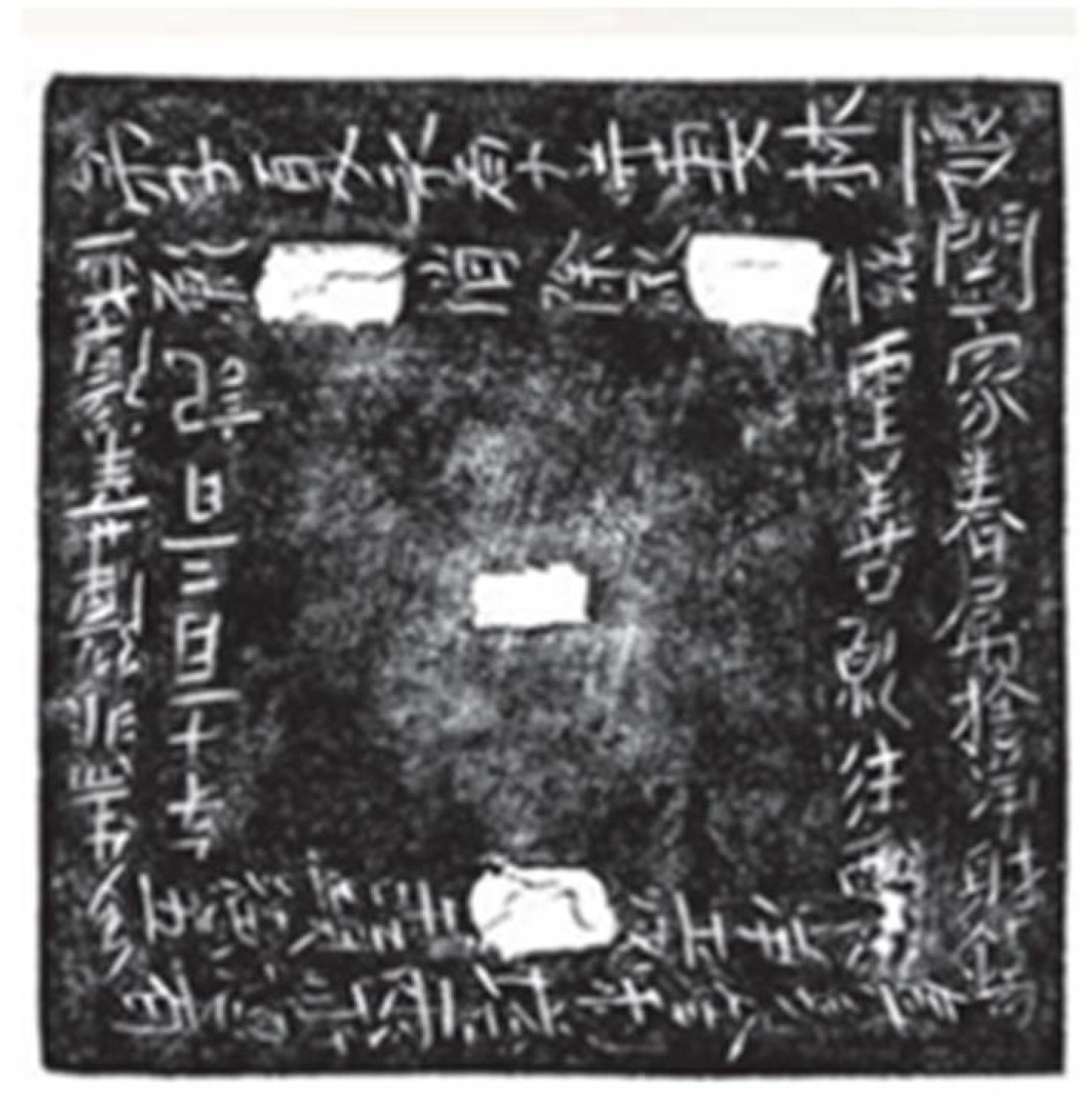

……大事既周,提河示寂,碎黃金相為設利羅,育王鑄塔以緘藏耶。舍手光而分佈,總有八萬四千所,而我中夏得一十九焉。金陵長幹寺塔,即第二所也…舊基空列於蓁蕪,峞級孰興於佛事。 每觀藏錄,空積感傷.。聖宋之有天下,封禪禮周,汾陰祀畢,乃有講律演化大師可政,塔就蒲津,願興墜典。言告中貴,以事聞天,尋奉綸言,賜崇寺、塔。 同將仕郎、守滑州助教王文,共為導首。率彼眾緣,於先現光之地,選彼名匠,造建磚塔,高二百尺,八角九層,又造寺宇。□□進呈感應舍利十顆,並佛頂真骨洎諸聖舍利,內用金棺,周以銀槨,並七寶造成阿育王塔,□以鐵□□函安置。 即以大中祥符四年太歲辛亥六月癸卯朔十八日庚申,備禮式設闔郭大齋,於皋際,庶□名數,永鎮坤維。....塔主演化大師可政。助緣管勾賜紫善來,小師普倫。導首將仕郎、守滑州助教王文,妻史氏十四娘,男凝、熙、規、拯…僧正賜紫守邈宣慧大師齊吉,賜紫文仲,僧仁相,紹之。舍舍利施護、守正、重航……

…When his business (teaching the laws) was done, the Buddha entered nirvāṇa. His golden body was broken to make Śarīras (relics), and King Aśoka constructed stūpas to encase them. The stūpas were broadly distributed and in the total number of eighty-four thousand, there are nineteen of them in our country—Zhongxia [China]. The stūpa at Changgan Monastery of Jinling is the second [Aśoka stūpa of China]… The old foundation of the stūpa [pagoda?] was seated alone in the wild, and the grand scale indicated that thriving Buddhist affairs had once taken place. Whenever I read its collections, I could do nothing but lament.Since the establishment of the sacred Song Dynasty, the Feng-Shan ceremony has been completed, and the Fen-Yin sacrifice has been finished. Then, the law-preaching Yanhua master Ke Zheng noted the pagoda’s tendency to decline and hoped for its revival for practicing rituals. He turned to dignitaries and let the heaven (emperor) know of his proposal. Consequently, Kezheng received the emperor’s decree and grant to revive the monastery and pagoda. With Wang Wen, a Jiang Shilang or assistant teacher in the Hua prefecture, Kezhang shared the role of head director. He led the laypeople and selected celebrated craftsmen to participate in the construction of the brick pagoda at the site where light had radiated throughout history. The pagoda is octagon-shaped and nine-storied, and is two hundred chi in height. Then, they continued to build structures in the monastery. □□ presented ten numinous-response relics, as well as the uṣṇīṣa of the Buddha and relics of holy monks. The relics are placed in nested reliquaries, which are golden, silver coffins, the Aśoka Stūpa made out of seven jewels, and the iron casket, in an outward order. On June 18, 1011, rituals were prepared and a large Zhai ceremony for the whole city was held. Next to the water, the interment is in hope for eternity.....The Yanhua master Kezheng in charge of the pagoda; Administrator of Buddhist affairs Shanlai; Monk Pulun; Head director Jiang Shilang; Assistant teacher of Hua Prefecture Wang Wen; his wife Shi Shisiniang; his sons Ning, Xi, Gui, Zheng … Monks: Qiji, Wenzhong, Renxiang, Shaozhi … Relic-donators: Shihu, Shouzheng, Chonghang …

5. The Analysis of the Seven-Jeweled Aśoka Stūpa

Interpretation of Distinguished Features from a Secular Perspective

高郵軍左廂招賢坊弟子荀懷義謹舍水晶杯一隻,碧琉璃杯一隻,白硨磲念珠一串,幸遇皇帝建金陵長幹寺阿育王所造釋迦佛真身舍利塔,下收葬供養舍利。 所願劫劫生生長承佛護。 時大宋大中祥符三年□月□日,弟子荀□記.Xun Huai, a Buddhist disciple from Zhaoxian Lane, Junzuo Xiang of Gaoyou, reverently donated a crystal cup, a green-glass cup, and a string of prayer beads made of white shells. Fortunately, I had a chance to contribute to the construction of the True-Body Pagoda, built by King Aśoka to intern the relics for enshrinement and worship, under the emperor’s commission. I wish for the eternal protection of the Buddha, in the date [?] of 1010, recorded by the disciple Xun [?].

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In recent years, a growing number of scholars have opposed the strict separation of the secular and the sacred in medieval Buddhist practice. Through a close reading of extant materials, they contend that many of the Buddhist practices of laypeople showed a mixture of sacred and secular features, incorporating a variety of factors such as religious imagination, socio-political contexts, and personal interests. See (Copp 2011; Sun 2019; Teiser 2020, pp. 171–72). Sun Yinggang 孫英剛 points out that the boundary between religious and secular texts, monastic and worldly identities, and beliefs and ideologies in medieval China was constantly changing (Sun 2020). |

| 2 | From his study of the family caves at Dunhuang built during the Tang Dynasty, Winston Kyan contends that the boundaries between secular and sacred spaces in these caves are ambiguous. Many murals show a mixture of Buddhist, Confucian, and Daoist icons, or flaunt the luxurious furnishings and material opulence belonging to this family. In addition, the images depicting ancestor worship directly reflect Confucian ideas, revealing the commissoner’s secular considerations. See (Kyan 2010). |

| 3 | Onishi Makiko 大西磨希子and Jinhua Chen have demonstrated the ideological meanings behind Emperor Wen’s distribution of relics across the country. In particular, the latter argues that this action was not only a device to legitimize the emperor’s rule, but also an aid in breaking down racial and cultural barriers to his reunification of the country. See (Chen 2002, p. 42; Onishi 2020). |

| 4 | The Edict on Building Stūpas Across the Sui State states that each monastic group should be cautious and diligent and travel taking good care of the relics. Before the groups enter their respective prefectures, ordinary people should have their homes cleaned of all filth. Regardless of belief and gender, people came from all over the city to welcome the returning monks. The prefectural supervisor, governor, and other officials stood along the street and led the team to their destination. The four sections of the people were all arrayed in a solemn manner. See (Yang, 1983, p. 213; Fairbank 1957, pp. 101–2). By analyzing Emperor Wen’s call to the whole state to participate in the ritual of relic worship and enshrinment, Zheng Yi 鄭弌argues that the emperor and nobles were primary beneficaries, despite the involvement of the alleged “all living beings”. Therefore, this case is different from the making of the Changgan stūpa, which allowed laypeople to be merit owners. See (Zheng 2016). |

| 5 | Wu Hung has summarized the scholarship on Liu Sahe and demonstrated how he became a religious icon in relation to relic worship in medieval China. See (Wu 1996, pp. 32–36). Although Liu’s miraculous deed—the discovery of the Buddha’s bodily relics beneath the Changgan stūp—is recorded in the History of Liang Dynasty, Chen Zhiyuan 陳志遠points out that the mystification of Liu first developed in central China, and then slowly expanded to the southeast of the country. See (Chen 2020). |

| 6 | Emperor Wu identified himself as the golden wheel-turning king/cakravartin, following Aśoka’s identification as the iron wheel-turning king. See (Endo 2021). |

| 7 | Zeng Liping曾立平 has researched the provenance of the bodily relics of the Changgan Monastery and briefly introduces the northern Indian monk Shihu and his donation of the uṣṇīṣa. See (Zeng 2011, p. 70). |

| 8 | The Ming gazette Jinling fancha zhi (A Record of Jinling Buddhist Monasteries金陵梵刹志) contains only a record of the history of the site where the Changgan Monastery had been located, but no details on the construction of the True-body Pagoda or the interment of the relics. These had been forgotten by later generations, and thus the crypt remained closed and intact from the Song Dynasty onward. See (Ge, 2007, pp. 459–93). |

| 9 | The record of Emperor Yang of Sui’s distribution of the relics is also included in Fayuan zhulin (The Pearl Forest in the Dharma Park法苑珠林), see (Shi Daoshi, 2003). The record of Li Deyu’s distribution is on the stone stele of the crypt of the Ganlu Monastery 甘露寺. A brief description of his actions can be found in (Mao 2009, pp. 212–20). |

| 10 | John Strong has carried out a meticulous study of King Aśoka’s act of building eighty-four thousand stūpas and its political implications. The king sought to identify himself as a cakravartin, the universal king in India culture. Strong also points out that rulers in other countries, such as Japan, emulated this act as a metaphor for their own political legitimacy. See (Strong 1983, pp. 109–25). |

| 11 | In a survey of the relic cult practised by rulers in medieval China, Liu Shufen discovered that they sought to legitimize their political authority via this cult. For example, Emperor Wen of the Sui Dynasty ordered a massive project of stūpa building across the country and asked that relics be interred simultaneously on the same day (Liu 2008, pp. 318–22). Shi Zhiru has studied the building of Aśoka stūpas and the acquisition of the Mao County Aśoka stūpa by the Wuyue kings, and concludes that as one of ten kings in China at that time, Qian Chu was anxious to justify and defend his political position by imitating King Aśoka’s contribution to Buddhism and expanding his own religio-political influence. See (Shi 2013, pp. 83–109). |

| 12 | For detailed information on the crypt of the Song Changgan Monastery, see (NMIA 2015, pp. 4–54). |

| 13 | For the entire inscription on the stele, see (NMIA 2015, pp. 14–15). |

| 14 | To read the full contents of some of the inscriptions, see (NMIA 2015, pp. 19–48). |

| 15 | Most of the gilt bronze stūpas were built in 955 CE, while the gilt iron ones were built in 965. The gap between the production of the two groups of stūpas led to nuanced differences (Chen 2011, pp. 29–30). Lee Seunghye also compared the features of the two groups, and found that major differences lay in the structure and Buddhist iconography. See (Lee 2013, pp. 57–60). |

| 16 | As Susan Whitefield points out, Buddhists and merchants established a “symbiotic” relationship as the former spread their religion to foreign areas along the trade routes (Whitefield 2018, p. 85). In another book, Whitefield demonstrates that the development of these trade routes, or the so-called Silk Road, largely resulted from the westward expasion of China since the second century BCE and the rise of the Kushan empire in the first century CE (Whitefield 2015, p. 2). Other scholars emphasize the importance of officials among this group of travelers. Dong Lili argues that soldiers and government officials constituted a large part of the travelers in the early Han Dynasty. One piece of evidence is that the Han emperors commanded military campaigns to combat Huns and therefore protect the western border for years (Dong 2021, pp. 25–26). Besides that, Emperor Wu, in particular, sent his envoy Zhang Qian 張騫 (ca.164–114 BCE) to the western kingdoms twice in order to form military allies. After Zhang’s final return in 126 BCE, the Han empire began expanding its control to the west (Hansen 2012, p. 14). |

| 17 | By examing the historical records, Xinru Liu stressed that in the first century CE, monks and their merchant patrons brought Buddhist texts and monasteries to China via the Silk Road. See (Liu 2010, pp. 58–59). |

| 18 | However, the four acroteria that often embellished Chinese Aśoka stūpas had no counterparts in ancient India or Gandhāra. Soper suggests, despite a lack of convincing evidence, that this unusual form might have developed from the harmikâ, a square-shaped fence standing on the top of early Indian stūpas. In this regard, Wang Chung-cheng’s 王鐘承 speculation may be more persuasive. Wang argues, through a comparision of acroteria and the architectural elements depicted in Han dynasty rubbings, that this distinctive form originated from the Chinese roof decoration on its wings. After being transformed and refined multiple times, the roof decoration lost its original function and became an eye-catching ornament on Chinese Aśoka stūpas. Therefore, acroteria can be seen as a symbol of the sinicization of Indian architecture. See (Wang 2012, pp. 116–17). |

| 19 | For a description of the Mao County stūpa, see (Shi Daoxuan, 1983, p. 404). Shi Zhiru translated the Chinese passage into English. See (Shi 2013, p. 92). Like the episode of Liu’s identification of the Changgan stūpa with the King Aśoka stūpas, his identification of the Mao County stūpa is also rife with myth and hyperbole. Scholars such as Wang Chung-cheng question the story’s reliability. However, its semi-fictionality does not change the fact that many noble people in medieval China worshiped this reliquary with great devotion. See (Wang 2012, pp. 123–26). |

| 20 | Zhejiang Museum (2008, p. 9). By comparing the images and compositions on several Chinese Aśoka stūpas, Hattori Atsuko suggests that since the Tang Dynasty, the designs of Chinese Aśoka stūpas had more or less been based on the Mao County stūpa, despite nuanced pictorial details. See (Hattori 2011, p. 125). |

| 21 | Shi Zhiru translated the Chinese passage into English. See (Shi 2013, p. 56). |

| 22 | Li Yuxin has collected and arranged information on excavated Aśoka stūpas, especially those built in the Wuyue period, and painstakingly lists many details about most of the excavated or extant Aśoka stūpas. See (Li 2009, pp. 36–41). |

| 23 | John Thompson articulates the construction and veneration of the many-jeweled stūpa described in the Lotus Sūtra. As its official name indicates, the Changgan stūpa can be categorized into this group, ranking the highest among all sorts of stūpas. See (Thompson 2008, pp. 126–27). |

| 24 | The average size was calculated by the present author, based on data from excavated Wuyue Aśoka stūpas, and the date taken from Li Yuxin’s article. See (Li 2009, pp. 36–41). |

| 25 | For the complete contents of Qian Chu’s dedicatory inscription, see (Zhejiang Museum 2008, p. 8). |

| 26 | Shi Zhiru has demonstrated the political motivations behind the Wuyue kings’ devotion to Buddhism by studying the Aśoka cult favored by the Qian family, their imitated act of the mass production of stūpas, and their ownership of aged Aśoka stūpas with symbolic meanings. See (Shi 2013, pp. 83–109). |

| 27 | Through an analysis of the production of Buddhist images by local people in southern China during the Tang and Song dynasties, Si Kaiguo summarizes the key characteristics of folk Buddhism as practicality and utility. The social status of the believers defined the quality of these two characteristics, meaning the eclectic and realistic selection of images emphasizes Buddhist beliefs, such as transmigration. See (Si 2013, pp. 210–13). |

| 28 | For more on the Song emperors ’attitudes and policies toward Buddhism, see (Pan 2000, pp. 476–79). |

| 29 | Lee’s dissertation argues that political and religious contexts must be considered in order to understand the contents of the dedicatory wishes. Most of the dedicatory wishes were written to protect the living or to ask for a better afterlife for deceased relatives. However, due to the unstable political and social environment of the Southern Song Dynasty, many votive inscriptions began with a blessing for the emperor. See (Lee 2013, p. 213). |

| 30 | Beginning with the introduction of Buddhism in the Eastern Han, relic veneration shifted from an event favored by the upper social classes to a publicly accessible affair. The watershed moment for this change was during the Tang and Song Dynasties. For more on this process, see (Liu 2008, pp. 322–27). |

References

Primary Sources

Ban, Gu 班固. 1962. Han shu 漢書. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.Ge, Yinliang 葛寅亮. 2007. Jinling fancha zhi 金陵梵刹志. Tianjin: Tianjin renmin chubanshe.Shen, Yue 沈約. 1983. Foji xu lue佛集序略. In Taishō shinshū dai zōkyō 大正新脩大藏經, vol. 52. Edited by Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎, Watanabe Kaikyoku 渡辺海旭, et al. Taipei: Xinwenfeng Press, pp. 201–2.Shi, Daoshi 釋道世. 2003. Fayuan zhulin 法苑珠林, vol. 3. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.Shi, Daoxuan 釋道宣. 1983. Ji shenzhou sanbao gantong lu集神州三寶感通錄. In Taishō shinshū dai zōkyō, vol. 52. Edited by Takakusu Junjirō, Watanabe Kaikyoku et al. Taipei: Xinwenfeng Press, pp. 404–35.Shi, Huijiao 釋慧皎. 1983. Gaoseng zhuan 高僧傳. In Taishō shinshū dai zōkyō, vol. 50. Edited by Takakusu Junjirō, Watanabe Kaikyoku et al. Taipei: Xinwenfeng Press, pp. 201–2.Shi, Zhiqin 釋志磐. 2012. Fozu tongji jiaozhu佛祖統紀校注, vol. 44. Shanghai: Shanghai guiji chubanshe.Yang, Jian 楊堅. 1983. Sui guoli shelita zhao 隋國立舍利塔詔. In Taishō shinshū dai zōkyō. vol. 52. Edited by Takakusu Junjirō, Watanabe Kaikyoku et al. Taipei: Xinwenfeng Press, pp. 97–363.Yao, Silian 姚思廉. 1973. Liang shu梁書. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.Secondary Sources

- Brose, Benjamin. 2015. Patrons and Patriarchs Regional Rulers and Chan Monks during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jinhua. 2002. Sarira and Scepter. Empress Wu’s Political Use of Buddhist Relics. Journal of International Association of Buddhist Studies 25: 33–150. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Lu 陳露. 2006. Cong bamianti fota kan Jiantuoluo yishu zhi dongchuan 從八面體佛塔看犍陀羅藝術之東傳. Xiyu yanjiu 西域研究 4: 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Ping 陳平. 2011. Bawan siqian ayuwang ta (shang)—Wuyue ayuwang ta shangjie八萬四千阿育王塔(上)—吳越阿育王塔賞介. Rongbao Zhai 榮寶齋 1: 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Zhiyuan 陳志遠. 2020. Handi sheli chongbai de xingqi—Nanchao fojiao guojiahua zhi yiduan漢地舍利崇拜的興起—南朝佛教國家化之一端. Paper presented at the “Keywords of the Liu-Song Dynasty劉宋關鍵詞國際學術研討會”; Taipei: Institute of Literature and Philosophy, Academia Sinica, December 14. [Google Scholar]

- CHGIS, 2016, Version: 6. (c) Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies of Harvard University and the Center for Historical Geographical Studies at Fudan University.

- Choi, Eung-Chon. 2003. Early Korean and Japanese Reliquaries in Relation to Pagoda Architecture. In Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan. Edited by Naomi Noble Richard. New York: Japan Society, pp. 178–89. [Google Scholar]

- Copp, Paul. 2011. Manuscript Culture as Ritual Culture in Late Medieval Dunhuang: Buddhist Talisman Seals and their Manuals. Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 20: 193–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Lili 董莉莉. 2021. Sichou Zhi Lu yu Han Wangchao de Xingsheng 絲綢之路與漢王朝的興盛. Ph.D. dissertation, Shandong University, Jinan, China. [Google Scholar]

- Endo, Yusuke 遠藤祐介. 2021. Ryō butei ni oke ru risō teki kōtei zō: Bosatsu kin rinō to shi te no kōtei 梁武帝における理想的皇帝像:菩薩金輪王としての皇帝. Journal of Institute of Buddhist Culture, Musashino University 37: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbank, John King. 1957. Chinese Thought and Institutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Jixi 高繼習. 2017. Zhongguo Gudai Sheli Digong Xingzhi Yanjiu 中國古代舍利地宮型制研究. Ph.D. dissertation, Shandong University, Jinan, China. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Zhaoguang 葛兆光. 1996. Nayige Fojiao, Nayige Daojiao: Tan Zhongguo Zongjiao yu Wenhua Yanjiu Zhongde Yige Wenti 哪一個佛教,哪一個道教-談中國宗教與文化研究中的一個問題. Dongfang 東方 3: 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Valerie. 2012. The Silk Road: A New History. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hattori, Atsuko 服部敦子. 2011. Aikuō tō no zōryū ni kansuru ichi kōsatsu—bukkyō zuzō no kentō o chūshin ni --阿育王塔の造立に関する一考察―仏教図像の検討を中心に―. In Wuyue shenglan guoji xueshu yantaohui lunwen ji 吳越勝覽國際學術研討會論文集. Beijing: Zhongguo shudian, pp. 107–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hurvitz, Leon. 1976. Scripture of the Lotus Blossom of the Fine Dharma. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jao, Tsung-I. 1990. Liu Sahe shiji yu ruixiang tu 劉薩訶事跡與瑞應圖. In Dunhuang Shiku Yanjiu Guoji Taolunhui Wenji 敦煌石窟研究國際討論會文集. Shenyang: Liaoning Meishu Chubanshe, pp. 336–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kyan, Winston. 2010. Family Space: Buddhist Materiality and Ancestral Fashioning in Mogao Cave 231. The Art Bulletin 92: 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Seunghye. 2013. Framing and Framed: Relics, Reliquaries, and Relic Shrines in Chinese and Korean Buddhist Art from the Tenth to the Fourteenth Centuries. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Seunghye. 2021. What Was in the ‘Precious Casket Seal’? Material Culture of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī throughout Medieval Maritime Asia. Religions 12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhengyu 李正宇. 1999. Tangsong Dunhuang Shisu Fojiao de Jingdian Jiqi Gongyong 唐宋敦煌世俗佛教的經典及其功用. Journal of Lanzhou Vocational Technical College 1: 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yuxin 黎毓馨. 2009. Ayuwang Ta Shiwu de Faxian yu Chubu Zhengli 阿育王塔實物的發現與初步整理. Cultural Relics of the East 31: 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shufen 劉淑芬. 2008. Zhonggu de Fojiao yu Shehui 中古的佛教與社會. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Xinru. 2010. The Silk Road in World History. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Ying 毛穎. 2009. Zhenjiang Ganlu Si Tangdai Sheli Yimai Zhidu ji Shelizi Yanjiu 鎮江甘露寺唐代舍利瘞埋制度及舍利子研究. Tangshi luncong 唐史論叢 1: 212–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Hajime 中村元. 1984. Zhongguo Fojiao Fazhanshi 中國佛教發展史. Translated by Wan-Chu Yu 余萬居. Taipei: Heavenly Lotus Publishing Co., Ltd., vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Hajime 中村元. 2013. 東洋人の思惟方法 (Ways of Thinking of Eastern Peoples: India, China, Tibet, Japan). Translated by Xu Fuguan 徐復觀. Taipei: Student Book Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nanjing Municipal Institute of Archaeology (NMIA). 2015. Nanjing Da Bao’en Si Yizhi Taji yu Digong Fajue Jianbao 南京大報恩寺遺址塔基與地宮發掘簡報. Cultural Relics 5: 4–54. [Google Scholar]

- Onishi, Makiko 大西磨希子. 2020. Sokuten bukō to aiku ō—Gihō nenkan no shari hanpu to『daiun he sho』o megu ^ te 則天武后と阿育王—儀鳳年間の舍利頒布と『大雲經疏』をめぐって. ” Dunhuang Nianbao 14: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, Antonello. 2012. Models of Buddhist Kinship in Medieval China. In Zhonggu Shidai de Liyi Zongjiao yu Zhidu 中古時代的禮儀、宗教與制度. Edited by Yu Xin. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, pp. 287–338. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Guiming 潘桂明. 2000. Zhonggu jushi fojiao shi中國居士佛教史. Beijing: China Social Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Haining 祁海寧, and Juping Gong 龔巨平. 2011. ‘Jinling Changgansi Zhenshenta Cang Sheli Shihan Ji’ Kaoshi ji Xiangguan Wenti ‘金陵長干寺真身塔藏舍利石函記’考釋及相關問題. Southeast Culture 1: 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Haining 祁海寧, and Juping Gong 龔巨平. 2012. Beisong Changgansi Gnashengta Digong Xingzhi Chengyin Chutan 北宋長干寺感聖塔地宮形製成因初探. Southeast Culture 1: 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Rhie, Marylin M. 2010. Early Buddhist Art of China and Central Asia. Leiden: Brill, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Lixin 尚麗新. 2007. ‘Dunhuang gaoseng’ Liu Sahe de shishi yu chuanshuo ‘敦煌高僧’劉薩訶的史實與傳說. Journal of Southwest Minzu University (Humanities and Social Science) 4: 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Hsueh-Man. 2019. Authentic Replicas: Buddhist Art in Medieval China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Zhiru. 2013. From Bodily Relic to Dharma Relic Stūpa: Chinese Materialization of the Aśoka Legend in the Wuyue Period. In India in the Chinese Imagination: Myth, Religion, and Thought. Edited by John Kieschnick and Meir Shahar. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 83–109. [Google Scholar]

- Si, Kaiguo 司開國. 2013. Tangsong Shiqi Nanfang Minjian Fojiao Zaoxiang Yishu唐宋時期南方民間佛教造像藝術. Beijing: China Social Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, Alexander C. 1940. Japanese Evidence for the History of the Architecture and Iconography of Chinese Buddhism. Monumenta Serica 4: 638–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, John. 1983. The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokavadana. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yinggang 孫英剛. 2019. Liangge Chang’an: Tangdai siyuan de zongjiao xinyang yu richang yinshi 兩個長安:唐代寺院的宗教信仰與日常飲食. Literature, History, and Philosophy文史哲 4: 38–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yinggang 孫英剛. 2020. Foguang xia de chaoting: Zhonggu zhengzhishi de zongjiao mian 佛光下的朝廷:中古政治史的宗教面. Journal of East China Normal University (Humanities and Social Science) 1: 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Teiser, Stephen F. 2020. Terms of Friendship: Bylaws for Associations of Buddhist Laywomen in Medieval China. In At the Shores of the Sky: Asian Studies for Albert Hoffstädt. Edited by Paul W. Kroll and Jonathan A. Silk. Leiden: Brill, pp. 154–72. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, John M. 2008. The Tower of Power’s Finest Hour: Stupa Construction and Veneration in the Lotus Sutra. Southeast Review of Asian Studies 30: 119–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiang, Katherine R. 2017. The ‘King Aśoka’ Type of Stūpa and Its Multivalent Meanings 阿育王式塔所具有的多種意義. Translated by Wang Pingxian. Dunhuang Research 2: 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chung-cheng 王鍾承. 2012. Wuyue guowang Qian Hongchu zao ayuwang ta吳越國王錢弘俶造阿育王塔. National Palace Museum Research Quarterly 29: 109–78. [Google Scholar]

- Whitefield, Susan. 2015. Life Along the Silk Road: Second Edition. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitefield, Susan. 2018. Silk, Slaves, and Stupas: Material Culture of the Silk Road. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung. 1996. Rethinking Liu Sahe: The Creation of a Buddhist Saint and the Invention of a ‘Miraculous Image’. Orientations 27: 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Yongquan 楊永泉. 2009. Nanjing zai zhongguo fojiao wenhua zhong de diwei 南京在中國佛教文化中的地位. Nanjing Journal of Social Sciences 南京社會科學 2: 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Xin 余新. 2011. Personal Fate and the Planets: A Documentary and Iconographical Study of Astrological Divination at Dunhuang, Focusing on the ‘Dhāraṇī Talisman for Offerings to Ketu and Mercury, Planetary Deity of the North’. Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 20: 163–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Anzhi 員安志. 1986. Shanxi fuxian shiku si kancha baogao 陝西富縣石窟寺勘察報告. Relics and Museology 6: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Liping 曾立平. 2011. Beisong jinling changgan si zhenshen ta digong fajue yu fo dingzhengu sheli chongguang 北宋金陵長干寺真身塔地宮發掘與佛頂真骨舍利重光. Identification and Appreciation to Cultural Relics 4: 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yuhuan 張馭寰. 2000. Zhongguo ta中國塔. Taiyuan: Shanxi People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zhejiang Museum, ed. 2008. Dongtu Foguang: Zhejiang Sheng Bowuguan Diancang Daxi 東土佛光:浙江省博物館典藏大系. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Ancient Books Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Yi 鄭弌. 2016. Daocheng sheli: Chongdu Renshou nianjian Suiwendi feng’an fo sheli shijian 道成舍利:重讀仁壽年間隋文帝奉安佛舍利事件. Art Research 藝術研究 3: 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Liyong 鄭立勇, and Songguang Lin 林松光. 1996. Shilun zhongguo minzhong de zhuti zongjiao yishi texing 試論中國民眾的主體宗教意識特性. Studies in World Religions 3: 11–16, 155–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Xueqin 周雪芹. 2005. Cong Dunhuang Fayuanwen Kan Tangsong Shiqi Minzhong de Fojiao Xinyang从敦煌愿文看唐宋时期民众的佛教信仰. Master’s thesis, Minzu University of China, Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dai, Y. Secular Dimensions of the Aśoka Stūpa from the Changgan Monastery of the Song Dynasty. Religions 2021, 12, 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110909

Dai Y. Secular Dimensions of the Aśoka Stūpa from the Changgan Monastery of the Song Dynasty. Religions. 2021; 12(11):909. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110909

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Yue. 2021. "Secular Dimensions of the Aśoka Stūpa from the Changgan Monastery of the Song Dynasty" Religions 12, no. 11: 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110909

APA StyleDai, Y. (2021). Secular Dimensions of the Aśoka Stūpa from the Changgan Monastery of the Song Dynasty. Religions, 12(11), 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110909