Saints, Sacred Trees, and Snakes: Popular Religion, Hierotopy, Byzantine Culture, and Insularity in Cyprus during the Long Middle Ages

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Aim and Structure

3. Methodological Concepts

3.1. Religious Groups

3.2. “Long Middle Ages”

3.3. Hierotopy

3.4. Ayios Iakovos and Shared Sacred Sites

4. Ayios Iakovos: Archaeology and History

4.1. Architecture

4.2. Byzantine Syrian Parallels

4.3. Historical Sources on Ayios Iakovos

5. Zooming in: Popular Religion and Hierotopy

5.1. Iconic Elements

5.2. Saint James the Persian

5.3. Sacred Trees

5.4. Snakes

5.5. “Snake Land”

5.6. Relationships of Iconic Elements

6. Zooming out: Insularity and Its Broader Contexts

6.1. Insular Identities: Fragmentation and Connectivity

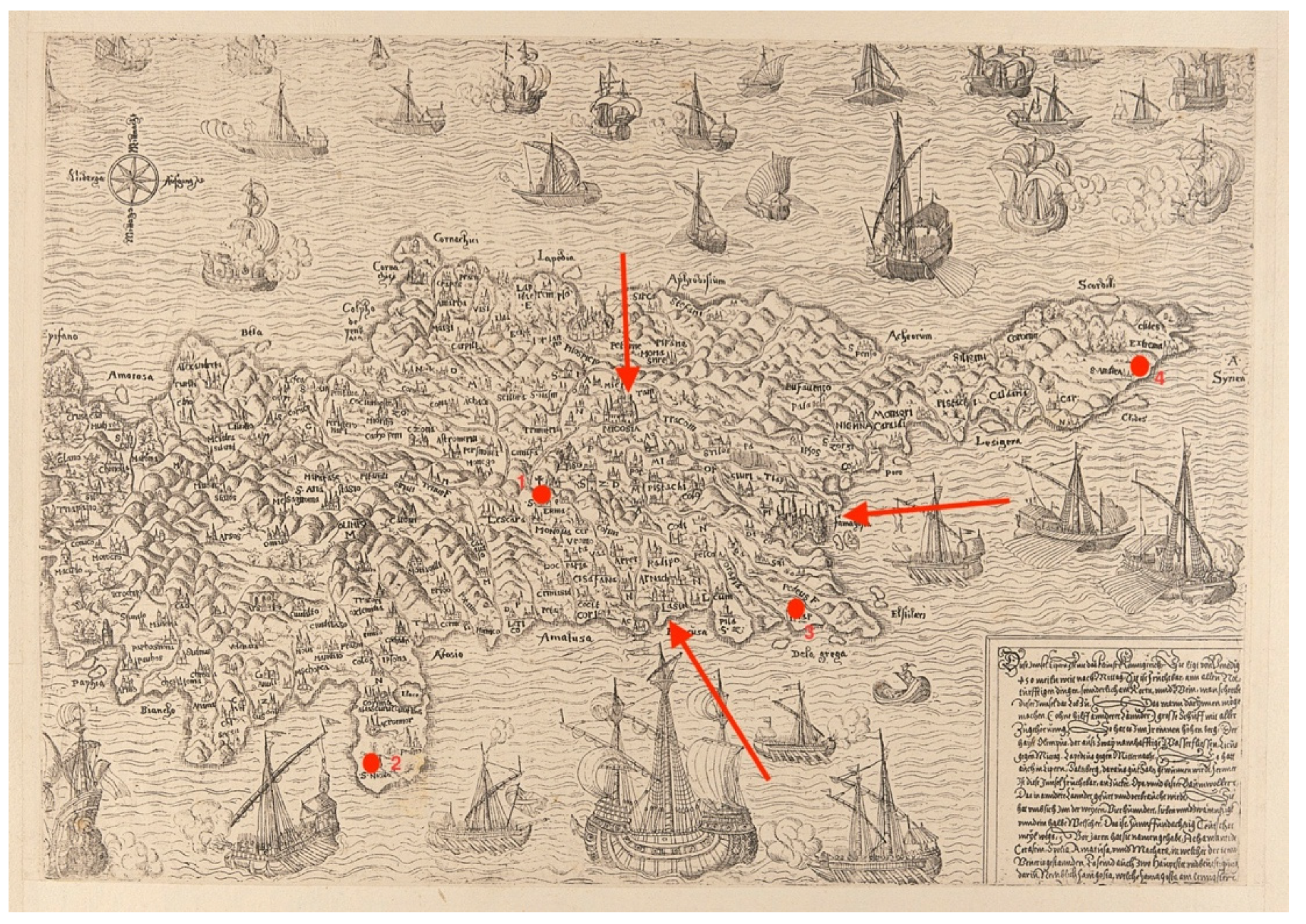

6.2. Trade, Pilgrimage, Mobility, and Sacred Landscapes

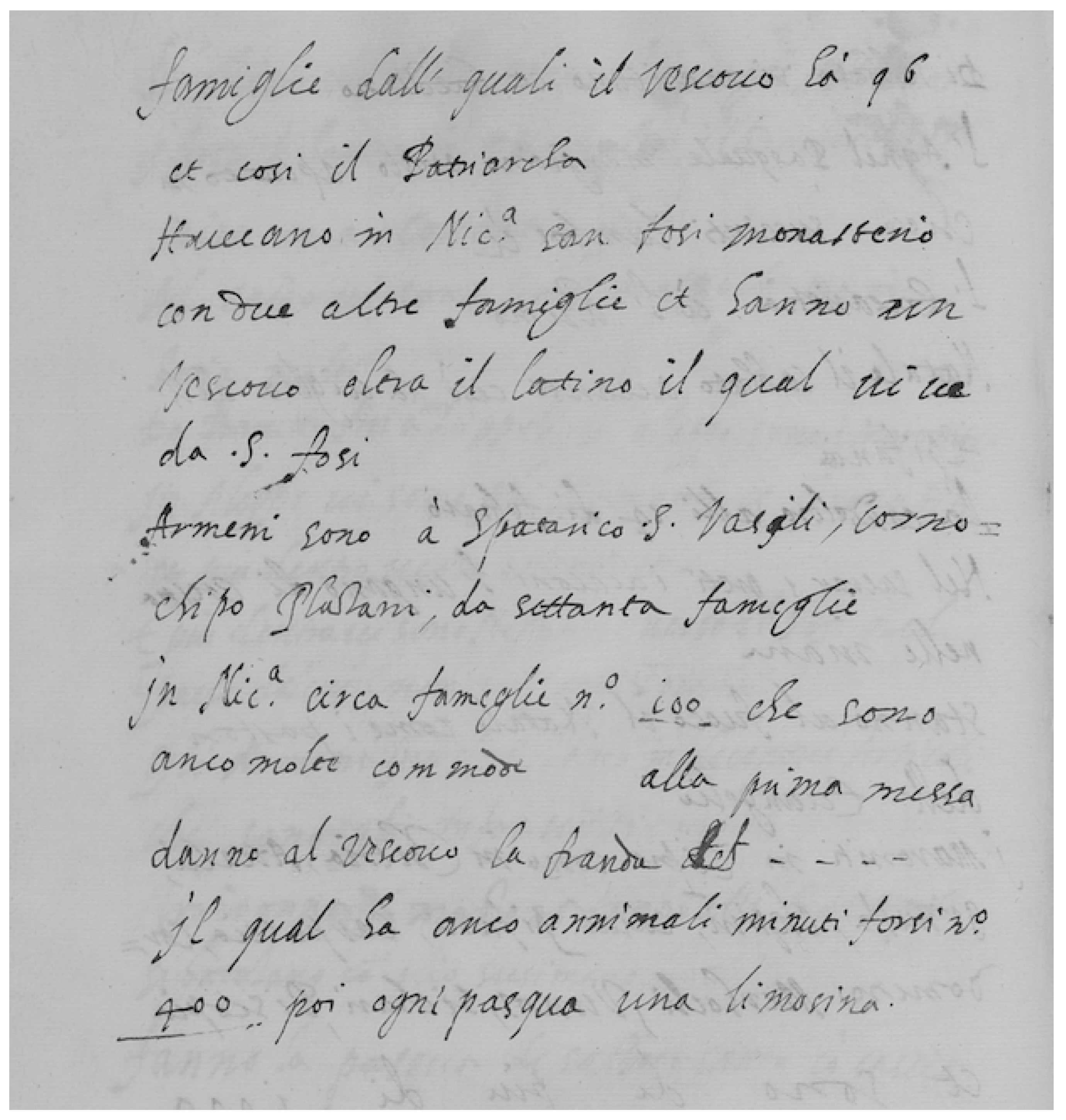

6.3. Cypriot Experiences of the Early Ottoman Rule

7. Conclusions

- (a)

- Ayios Iakovos as a multi-faith religious site. The historical exploration of the shrine has confirmed its role as a shared holy place and healing centre in the seventeenth century. The architectural survey has shown the existence of both Byzantine and Latin influences, suggesting syncretism and confessional co-existence. We have proposed that the origins of Saint James the Persian’s veneration in Cyprus could be traced back in Byzantine times, especially during the Byzantine rule in Cyprus and Syria between the tenth and twelfth centuries.

- (b)

- Details in the creative making of sacred landscape. There are three iconic elements in Ayios Iakovos’ hierotopic landscape: saint, cypress, and snake. The Byzantine dossier of liturgical and hagiographical texts on Saint James the Persian indicates an arboreal symbolism (the saint as a cypress tree) with roots in Syriac theology. The analysis of the three iconic elements connects Cyprus to Greater Syria, creating a familiar hieros topos for worshippers from different groups and the practice of healing. Apparently, this occurred without drawing a sharp line between official and popular religion. There are also some Cypriot parallels (Stavrovouni and Ayios Nikolaos at Akroteri), suggesting that the creative blending of iconic elements in Ayios Iakovos should be seen as part of the widespread perception of Cyprus as “snake land” after the fifteenth century.

- (c)

- Global, regional, and local developments. From ca. 1400 to ca. 1700, trade and pilgrimage mobility in the eastern Mediterranean were important for reasserting the significance of holy shrines in Cyprus, both in maritime areas and the mainland. The orientation of Cypriot economy and pilgrimage traffic was largely Levantine, which supports our earlier interpretation of hierotopic mobility from Greater Syria to Cyprus. At the same time, the bleak conditions of the early Ottoman rule, exacerbated by environmental anomalies, created a new dynamic for worshippers attracted to Saint James’ church at Nicosia. Ayios Iakovos encapsulates these broader tendencies, witnessing the interactive relationship (but not homogenisation) of different religious groups, each of whom had its own beliefs, anxieties, and expectations. Ultimately, Ayios Iakovos, with its healing powers and sacred iconic elements, provided the common ground for Orthodox, Maronites, Latins, crypto-Christians, and Muslims to co-exist and worship within its sacred enclosure.

- (d)

- Byzantine connectivities. In the 1600s, when Ayios Iakovos became a Latin cathedral under the shadow of the Ottomans, the spiritual message of Saint James’ story (sacrificial victory over death) seems to have become more relevant for Cypriot Christian believers, regardless of confessional identity. This was partly due to the revived interest of Muslim-ruled Cypriot Christians in the concepts of persecution and martyrdom. The theological symbolism of Saint James became possible through the translation of texts on his martyrdom from Syriac into Byzantine Greek (and later into Latin and other languages), initially in the tenth/eleventh century. Likewise, the emergence of the saint’s veneration in Cyprus seems to date around the period of Byzantine rule in the Levant. Although Ayios Iakovos changed hands throughout the centuries, the saint’s memory remained associated with his passion, bearing witness to the religious and cultural connectivities between Cyprus and the Byzantine world, as well as to the inclusive power of Saint James as a spiritual symbol.

- (e)

- Ayios Iakovos and other shared sacred sites. This case study, with its emphasis on interconnectivity and insularity, echoes the tendency of recent scholarship to examine shared sacred sites within a much broader nexus of exchanges and mobility. The hierotopic combination of the three iconic elements analysed here is crucial in understanding the distinctive physiognomy of Ayios Iakovos as an “imagined” (per Luig) hieros topos. Like other places of mixed worship, Ayios Iakovos should not be viewed as a “melting pot”, but rather as the home of various groups, who maintained their own traditions and remained open to syncretism. What is rather atypical in the case of Ayios Iakovos, is the fact that the church is not a rural one. According to Albera, “mixed attendance … tends to focus on very small rural shrines that are deep in the countryside and associated with rituals based on the farming calendar” (Albera 2012, p. 228). This could be probably the result of the long history of Ayios Iakovos changing hands as time went by. As suggested by seventeenth-century sources, the communities whose history remained associated with the site continued to be attracted by it, regardless of who possessed it. To remember Hayden, centrality indicates dominance and highlights the competitive co-existence of religious groups in mixed holy places. Clearly, this view is reflected in Vespa’s aforementioned statement in 1638 that Ayios Iakovos should become the Latin cathedral, because of its centrality in the Latin quarter and the city of Nicosia. The success of Ayios Iakovos as a shared sacred centre might have been also related to what Albera describes as “devotional ambivalence” (Albera 2012, p. 230). Due to his Persian/Syrian origins and popularity in East and West, Saint James belonged to everyone and was venerated by everyone, even if the cultures, beliefs, and expectations of his devotees were not always the same.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albera, Dionigi. 2012. Crossing the Frontiers between the Monotheistic Religions, an Anthropological Approach. In Sharing Sacred Spaces in the Mediterranean. Christians, Muslims, and Jews and Shrines and Sanctuaries. Edited by Dionigi Albera and Maria Couroucli. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, pp. 219–44. [Google Scholar]

- Albera, Dionigi, and Maria Couroucli, eds. 2012. Sharing Sacred Spaces in the Mediterranean. Christians, Muslims, and Jews and Shrines and Sanctuaries. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Albera, Dionigi, and John Eade, eds. 2017. New Pathways in Pilgrimage Studies: Global Perspectives. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Angel, Andrew R. 2006. Chaos and the Son of Man. The Hebrew Chaoskampf Tradition in the Period 515 BCE to 200 CE. London and New York: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Arbel, Benjamin. 2004. The Last Decades of Venice’s Trade with the Mamluks: Importations into Egypt and Syria. Mamluk Studies Review 8: 37–86. [Google Scholar]

- Arbel, Benjamin. 2007. Venetian Letters (1354–1512) from the Archives of the Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation and Other Cypriot Collections. Nicosia: Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Arbel, Benjamin. 2014. Maritime Trade in Famagusta during the Venetian Period (1474–1571). In “The Harbour of all this Sea and Realm”: Crusader to Venetian Famagusta. Edited by Michael J. K. Walsh, Tamás Kiss and Nicholas Coureas. Budapest and New York: Central European University Press, pp. 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud, Pascale. 2005. Les Routes de la Navigation Antique: Itinéraires en Méditerranée et Mer Noire. Paris: Errance. [Google Scholar]

- Asdrachas, Spyros I. 1988. Oικονομία και νοοτροπίες. Athens: Hermes. [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore, Wendy. 2004. Social Archaeologies of Landscape. In A Companion to Social Archaeology. Edited by Lynn Meskell and Robert W. Preucel. Malden and Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 255–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bacci, Michele. 2014. On the Holy Topography of Sailors: An Introduction. In The Holy Portolano. The Sacred Geography of Navigation in the Middle Ages. Edited by Michele Bacci and Martin Rohde. Berlin, Munich and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Barkan, Elazar, and Karen Barkey, eds. 2014. Choreographies of Shared Sacred Sites: Religion, Politics and Resolution. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. The Location of Culture. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bireley, Robert. 2014. Ferdinand II, Counter-Reformation Emperor, 1578–1637. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, Alexander. 2004. A Comparative Glossary of Cypriot Maronite Arabic. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, Glenn, ed. 2012. Sharing the Sacra. The Politics and Pragmatics of Inter-Communal Relations around Holy Places. New York and Oxford: Berhahn. [Google Scholar]

- Braudel, Fernand. 1990. La Méditerranée et le Monde Méditerranéen à l’époque de Philippe II. Paris: Armand Colin, vol. 1. First published 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, Colin. 2019. The early Ottomanization of urban Cyprus. Post-Medieval Archaeology 53: 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, Sebastian. 1987. The Syriac Fathers on Prayer and the Spiritual Life. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Calvelli, Lorenzo. 2014. Cypriot origins, Constantinian blood: The legend of the young Saint Catherine of Alexandria. In Identity/Identities in Late Medieval Cyprus. Edited by Tassos Papacostas and Guillaume Saint-Guillain. Nicosia: Cyprus Research Centre, pp. 361–90. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, Leo. 2011. A Persian Martyr in a Middle English Vernacular Exemplum: The Case of St James Intercisus. Medieval Sermon Studies 55: 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caseau, Béatrice, and Charis Messis. 2021. Saint Syméon Stylite le Jeune et son héritage au XIe–XIIe siècle. Βυζαντινά Σύμμεικτα 31: 241–80. [Google Scholar]

- Casson, Lionel. 1950. The Isis and her voyage. Transactions of the American Philological Association 81: 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catlos, Brian A. 2014. Muslims of Medieval Latin Christendom, c. 1050–1614. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chotzakoglou, Charalambos. 2017. H αρχιτεκτονική στους παλαιοχριστιανικούς και μεσοβυζαντινούς ναούς της Καρπασίας. In Καρπασία: Πρακτικά B΄ Επιστημονικού Συνεδρίου. Edited by Panayiotis Papageorghiou. Limassol: Free United Karpasia Association, pp. 269–93. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, David. 2018. A History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou, Georges, ed. 2009. Le Livre des Catéchèses de saint Néophyte le Reclus. Nicosie: Fondation de l’Archevêque Makarios III. [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou, Georgios. 2010. H συμβολή της ρωμαϊκής αριστοκρατίας στην εξέλιξη του αρχαίου μοναχισμού της Aνατολής: Sancta Paula Romana. In Καρπασία: Πρακτικά A΄ Επιστημονικού Συνεδρίου. Edited by Panayiotis Papageorghiou. Limassol: Free United Karpasia Association, pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Chrysochoides, Kriton. 2003. Ιερά Aποδημία. Το προσκυνηματικό ταξίδι στους Aγίους Τόπους στα μεταβυζαντινά χρόνια. In Το ταξίδι: από τους αρχαίους έως τους νεότερους χρόνους. Edited by Ioli Vingopoulou. Athens: National Hellenic Research Foundation, pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Chrysos, Evangelos. 2016–2017. Το Βυζάντιο: H Aυτοκρατορία της Κωνσταντινουπόλεως. Κυπριακαί Σπουδαί 78–79: 1005–22. [Google Scholar]

- Costantakopoulou, Christy. 2007. The Dance of the Islands. Insularity, Networks, the Athenian Empire and the Aegean World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Costantini, Vera. 2009. Il sultano e l’isola Contesa. Cipro tra Eredità Veneziana e Potere Ottomano. Milan: UTET Libreria. [Google Scholar]

- Coureas, Nicholas, Gilles Grivaud, and Chris Schabel. 2012. Frankish and Venetian Nicosia, 1191–1571. In Historic Nicosia. Edited by Demetrios Michaelides. Nicosia: Rimal, pp. 111–229. [Google Scholar]

- Couroucli, Maria. 2014. Shared Sacred Places. In A Companion to Mediterranean History. Edited by Peregrine Horden and Sharon Kinoshita. Malden and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 378–91. [Google Scholar]

- Creţu, Marianna-Stefania. 2015. Answer Given by Ms Creţu on Behalf of the Commission (Question Reference: E-008509/2014). European Parliament, Parliamentary Questions. January 7. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-8-2014-008509-ASW_EN.html (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Dafni, Amots. 2007a. Rituals, ceremonies and customs related to sacred trees with a special reference to the Middle East. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 3: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dafni, Amots. 2007b. The supernatural characters and powers of sacred trees in the Holy Land. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 3: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dandelet, Thomas James. 2014. The Renaissance of Empire in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dandini, Jerome. 1685. Voyage du Mont Liban, traduit de l’Italien. Paris: Louis Billaine [Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation, B-287]. First published 1675. [Google Scholar]

- Darkes, Antonios. 2017. Προσκυνητάριον τῶν Ἱεροσολύμων. Edited by Maroula Yiasemidou-Katzi, with contributions by Markos Foskolos and Nasa Patapiou. Limassol: Society of Kiolaniotes. First published 1645. [Google Scholar]

- Della Dora, Veronica. 2016. Landscape, Nature, and the Sacred in Byzantium. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Demesticha, Stella, Katerina Delouca, Mia Gaia Trentin, Nikolas Bakirtzis, and Andonis Neophytou. 2017. Seamen on Land? A Preliminary Analysis of Medieval Ship Graffiti on Cyprus. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 46: 346–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demilyürek, Mehmet. 2010. The Commercial Relations Between Venice and Cyprus After the Ottoman Conquest (1600–1800). Levant 42: 237–54. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Forests, Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment, Republic of Cyprus. 2012. Trees Nature Monuments of Cyprus. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cy/moa/fd/fd.nsf/F8684AD2DDA64365C22581290029A4E8/$file/Trees%20Nature%20Monuments%20of%20Cyprus%20-%20Four%20fold%20flyer.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Detoraki, Maria. 2014. Greek Passions of the Martyrs in Byzantium. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Byzantine Hagiography. Edited by Stephanos Efthymiadis. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate, vol. 2, pp. 61–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dever, William G. 2005. Did God Have a Wife? Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Grand Rapids and Cambridge: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Devos, Paul, ed. 1953. Le dossier hagiographique de S. Jacques l’Intercis (I). Analecta Bollandiana 71: 157–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devos, Paul, ed. 1954. Le dossier hagiographique de S. Jacques l’Intercis (II). Analecta Bollandiana 72: 213–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, Plácido. 2019. Open Letter to the Two Leaders of Cyprus (25 February 2019). Europa Nostra. Available online: https://www.europanostra.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/20190225-OpenLetter-PlacidoDomingo-CyprusLeaders-Nicosia.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Drakopoulou, Eugenia. 2013. In hoc Signo vinces between 1453–1571: The iconography of an encounter between art and history. НИШ И ВИЗАНТИЈА 12: 387–98. [Google Scholar]

- Eade, John, and Dionigi Albera. 2017. Pilgrimage Studies in Global Perspective. In New Pathways in Pilgrimage Studies: Global Perspectives. Edited by Dionigi Albera and John Eade. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Eger, A. Asa. 2013. (Re)Mapping Medieval Antioch. Urban Transformations from the Early Islamic to the Middle Byzantine Periods. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 67: 95–134. [Google Scholar]

- Eliades, Ioannis. 2017. Icons of Cyprus (1191–1300). In Maniera Cypria. The Cypriot Painting of the Thirteenth Century Between Two Worlds. Edited by Ioannis Eliades. Lefkosia: Archbishop Makarios III Foundation, pp. 80–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ephrat, Daphna. 2021. Sufi Masters and the Creation of Holy Spheres in Medieval Syria. Leeds: Arc Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eshel, Shay. 2018. The Concept of the Elect Nation in Byzantium. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Farahmand, Homayoun, and Harim R. Karimi. 2018. Old Persian cypress accessions, a rich and unique genetic resource for common cypress (Cupressus sempervirens L.) in the world. Acta Horticulturae 1190: 113–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febvre, Michel. 1682. Théâtre de la Turquie, Traduit d’Italien en François. Paris: Edme Couterot. [Google Scholar]

- Flourentzos, Panayiotis. 2001. H δεντρολατρεία στην αρχαία Κύπρο. Archaeologia Cypria 4: 123–28. [Google Scholar]

- Foulias, Andreas. 2005. Άγιοι Σαράντα/Kirklar Tekke. Μια νέα παλαιοχριστιανική βασιλική. Κυπριακαί Σπουδαί 69: 3–24, 247–72. [Google Scholar]

- Foulias, Andreas. 2020. Oι απαρχές της μονής. In H Ιερά Μονή του Aποστόλου Aνδρέα στην Καρπασία. Edited by Christodoulos Hadjichristodoulou and Andreas Foulias. Nicosia: Holy Bishopric of Karpasia, pp. 71–104. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, Laura. 2009. A Study of the Metaphrastic Process: The case of the unpublished Passio of St James the Persian (BHG 773), Passio of St Plato (BHG 1551–1552), and Vita of St Hilarion (BHG 755) by Symeon Metaphrastes. Ph.D. Thesis, Royal Holloway, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Frazee, Charles A. 1983. Catholics and Sultans. The Church and the Ottoman Empire, 1453–1923. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frazer, James G. 1922. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, Abridged ed. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Fumaroli, Marc. 1995. Cross, Crown, and Tiara: The Constantine Myth between Paris and Rome (1590–1690). Studies in the History of Art 48: 88–102. [Google Scholar]

- Galadza, Daniel. 2018. Liturgy and Byzantinization in Jerusalem. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, Delfin. 1991. Snakebite Problems in Europe. In Handbook of Natural Toxins. Edited by Anthony T. Tu. New York: Marcel Dekker, vol. 5, pp. 687–754. [Google Scholar]

- Goodison, Lucy. 2016. Holy Trees and Other Ecological Surprises. Dorset: Just Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grehan, James. 2014. Twilight of the Saints: Everyday Religion in Ottoman Syria and Palestine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grierson, Roderick. 2014. “One Shrine Alone”: Christians, Sufis, and the Vision of Mawlana. In The Philosophy of Ecstasy. Rumi and the Sufi Tradition. Edited by Leonard Lewisohn. Bloomington: World Wisdom, pp. 83–126. [Google Scholar]

- Grivaud, Gilles. 1995. Éveil de la nation chyproise (XIIe–XVe siècles). Sources Travaux Historiques 43–44: 105–16. [Google Scholar]

- Grivaud, Gilles. 1998. Villages désertés à Chypre = Μελέται και Υπομνήματα. Nicosia: Archbishop Makarios III Foundation, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjianastasis, Marios. 2009. Cyprus in the Ottoman Period: Consolidation of the Cypro-Ottoman Elite, 1650–1750. In Ottoman Cyprus: A Collection of Studies on History and Culture. Edited by Michalis N. Michael, Matthias Kappler and Eftihios Gavriel. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjikyriacou, Antonis. 2016. The Ottomanisation of Cyprus: Towards a spatial imagination beyond the centre-province binary. Journal of Mediterranean Studies 25: 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjikyriacou, Antonis. 2017. Envisioning Insularity in the Ottoman World. Princeton Papers: Interdisciplinary Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjikyriacou, Antonis. 2019a. Akdeniz Çerçevesi Içinde Osmanli Kibris’inda Tahil Üretimi. Meltem 6: 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjikyriacou, Antonis. 2019b. Beyond the millet debate: Communal representation in pre-Tanzimat-era Cyprus. In Political thought and Practice in the Ottoman Empire. Halcyon Days in Crete IX. Edited by Marinos Sariyannis. Rethymno: Crete University Press, pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Håland, Evy Johanne. 2011. Saints and Snakes: Death, Fertility, and Healing in Modern Ancient Greece and Italy. Performance and Spirituality 2: 111–51. [Google Scholar]

- Harmansah, Rabia. 2021. “Fraternal” Other: Negotiating Ethnic and Religious Identities at a Muslim Sacred Site in Northern Cyprus. Nationalities Papers, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, William. 2012. Lebanon: A History, 600–2011. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hasluck, Frederick W. 1929. Christianity and Islam under the Sultans. Oxford: Clarendon Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hassiotis, Ioannis K., ed. 2000. Πηγές της Κυπριακής Ιστορίας από το Ισπανικό Aρχείο Simancas: Aπό τη Μικροϊστορία της Κυπριακής Διασποράς κατά τον ΙΣΤ΄ και ΙΖ΄αιώνα. Nicosia: Cyprus Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Hassiotis, Ioannis K., ed. 2003. Ισπανικά έγγραφα της κυπριακής ιστορίας (ΙΣΤ΄-ΙΖ΄αιώνας). Nicosia: Cyprus Research Centre. First published 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Hassiotis, Ioannis K. 2010. Oι αντιτουρκικές κινήσεις στην Κύπρο και η στάση των ευρωπαϊκών δυνάμεων (από την οθωμανική κατάκτηση ως τις αρχές του 19ου αιώνα). In Κύπρος: Aγώνες Ελευθερίας στην Ελληνική Ιστορία. Edited by Andreas Voskos. Athens: National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, pp. 147–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hatay, Mete. 2015. “Reluctant” Muslims? Turkish Cypriots, Islam, and Sufism. The Cyprus Review 27: 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, Robert M. 2013. Intersecting Religioscapes and Antagonistic Tolerance: Trajectories of Competition and Sharing of Religious Spaces in the Balkans. Space and Polity 17: 320–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, Robert M., Tugba Tanyeri-Erdemir, Timothy D. Walker, Aykan Erdemir, Devika Rangachari, Manuel Aguilar-Moreno, Enrique López-Hurtado, and Milika Bakic-Hayden. 2016. Antagonistic Tolerance. Competitive Sharing of Religious Sites and Spaces. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Heyberger, Bernard. 2012. Polemic Dialogues between Christians and Muslims in the Seventeenth Century. Journal of Economic and Social History of the Orient 55: 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyden, Katharina. 2020. Construction, Performance, and Interpretation of a Shared Holy Place. The Case of Late Antique Mamre (Rāmat al-Khalīl). Entangled Religions 11: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horden, Peregrine, and Nicholas Purcell. 2006. The Mediterranean and “the New Thalassology”. The American Historical Review 111: 722–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovorun, Serhiy. 2003. Theological Controversy in the Seventh Century Concerning Activities and Wills in Christ. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Durham, Durham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Alisa. 2016. Reviving Roman Religion: Sacred Trees in the Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ionas, Ioannis. 2013. Δεισιδαιμονία και μαγεία στην Κύπρο του χτες. Nicosia: Cyprus Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Izmirlieva, Valentina. 2014. Christian Hajjis—The Other Orthodox Pilgrims to Jerusalem. Slavic Review 73: 322–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, David. 2016. Evolving routes of Western pilgrimage to the Holy Land, eleventh to fifteenth century: An overview. In Unterwegs im Namen der Religion II/On the Road in the Name of Religion II. Edited by Klaus Herbers and Hans Christian Lehner. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, pp. 75–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, Ronald C. 1988. The Locust Problem in Cyprus. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 51: 279–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, Ronald C. 1993. Christians and Muslims in Ottoman Cyprus and the Mediterranean World, 1571–1640. New York and London: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jestrzemski, Daniel, and Irina Kuzyakova. 2018. Morphometric characteristics and seasonal proximity to water of the Cypriot blunt-nosed viper Macrovipera lebetina lebetina (Linnaeus, 1758). Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases 24: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaffenberger, Thomas. 2020. Tradition and Identity. The Architecture of Greek Churches in Cyprus (14th to 16th Centuries). Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldellis, Anthony. 2019a. Byzantium Unbound. Leeds: Arc Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldellis, Anthony. 2019b. Romanland: Ethnicity and Empire in Byzantium. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kamberidis, Fr. Lambros. 2013. Hσυχασμός και Σουφισμός. Θεολογία 84: 209–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplanis, Tassos A. 2014. Antique Names and Self-Identification: Hellenes, Graikoi, and Romaioi from Late Byzantium to the Greek Nation-State. In Re-imagining the Past. Antiquity and Modern Greek Culture. Edited by Dimitris Tziovas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplanis, Tassos A. 2015. Νεόφυτος Ροδινός—Ιωακείμ Κύπριος: Λογοτεχνικές αποτυπώσεις της Κύπρου και ταυτότητες στο 17ο αι. Επετηρίδα Κέντρου Επιστημονικών Ερευνών 37: 283–10. [Google Scholar]

- Karagianni, Alexandra B. 2010. O Σταυρός στη Βυζαντινή Μνημειακή Ζωγραφική. H λειτουργία και το δογματικό του περιεχόμενο. Thessaloniki: Byzantine Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Kitromilides, Paschalis M. 2009. F. W. Hasluck and Christianity and Islam under the Sultans. In Scholars, Travels, Archives: Greek History and Culture through the British School at Athens. Edited by Michael Lewellyn Smith, Paschalis Kitromilides and Eleni Calligas. London: British School at Athens, pp. 103–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kitto, John. 1840. The Illustrated Commentary on the Old and New Testaments, Chiefly Explanatory of the Manners and Customs Mentioned in the Sacred Scriptures; and also of History, Geography, Natural History, and Antiquities; Being a Republication of the Notes of the Pictorial Bible of a Size Which Will Range with the Authorized Editions of the Sacred Text. London: Charles Knight & Co., vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, Arthur Bernard. 2007. Insularity and island identity in the prehistoric Mediterranean. In Mediterranean Crossroads. Edited by Sophia Antoniadou and Anthony Price. Athens: Pierides Foundation, pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinoftas, Kostis. 2018. H κοινότητα Καϊμακλίου και η σχέση της με το Άγιον Όρος. Εικονοστάσιον 10: 195–208. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinoftas, Kostis. 2019. Εξισλαμισμοί και επανεκχριστιανισμοί στην Κύπρο. Nicosia: Holy Monastery of Kykkos Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Kolovos, Elias, and Phokion Kotzageorgis. 2019. Searching for the “Little Ice Age” effects in the Ottoman Greek lands: The cases of Salonica and Crete. In Seeds of Power: Explorations in Ottoman Environmental History. Edited by Onur Inal and Yavuz Köse. Winwick: The White Horse Press, pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Koutelakis, Haris. 2010. Oι Γάτες του Aκρωτηρίου της Κύπρου. Κυπριακαί Σπουδαί 74: 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Krantonelli, Alexandra. 2014. Ιστορία της πειρατείας στους μέσους χρόνους της Τουρκοκρατίας, 1538–1669. Athens: Estia. First published 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Krstić, Tijana. 2021. Historicizing the Study of Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750. In Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750. Edited by Tijana Krstić and Derin Terzioğlu. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Archimandrite, Kyprianos. 1902. Ιστορία Χρονολογική της Νήσου Κύπρου. Nicosia. First published 1788. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou, Chrysovalantis. 2018. Orthodox Cyprus under the Latins: Society, Spirituality, and Identities, 1191–1571. New York and London: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou, Chrysovalantis, ed. 2019. Κυπροβενετικά. Στοιχεία θρησκευτικής ανθρωπογεωγραφίας της βενετοκρατούμενης Κύπρου από τον κώδικα Β-030 του Πολιτιστικού Ιδρύματος Τράπεζας Κύπρου. Εισαγωγή, διπλωματική έκδοση, μετάφραση και σχόλια. Nicosia: Holy Monastery of Kykkos Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou, Chrysovalantis. 2020a. Christian Diversity in Late Venetian Cyprus. A Study and English Translation of Codex B-030 from the Collections of the Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation. Lefkosia: Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou, Chrysovalantis. 2020b. The Byzantine Warrior Hero: Cypriot Folk Songs as History and Myth, 965–1571. New York and London: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou, Chrysovalantis. 2021. Πόλεμος της Κύπρου (1570–73) και χριστιανική ταυτότητα: μια νέα αφετηρία ιδεολογικών μετασχηματισμών. In Χριστιανική ετερότητα και συνύπαρξη πριν και μετά την οθωμανική κατάκτηση. H Κύπρος στο μεταίχμιο δύο κόσμων (16ος–17ος αι.). Edited by Chrysovalantis Kyriacou. Lefkosia: Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kyrris, Costas P., ed. 1987. The Kanakaria Documents, 1666–1850: Sale and Donation Deeds. Nicosia: Cyprus Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Lacarrière, Jacques. 2013. Λευκωσία: H Νεκρή Ζώνη. Translated by Voula Louvrou. Athens: Olkos. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goff, Jacques. 2015. Must We Divide History into Periods? Translated by Malcolm B. DeBevoise. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lepida, Styliani. 2015. O περιβαλλοντικός παράγοντας και ο ρόλος του στην κοινωνική και οικονομική ιστορία: η περίπτωση της οθωμανικής Κύπρου (17ος αιώνας). Βαλκανικά Σύμμεικτα 17: 188–208. [Google Scholar]

- Lidov, Alexei, ed. 2009. Hierotopy. The Creation of Sacred Spaces as a Form of Creativity and Subject of Cultural History. In Hierotopy. Spatial Icons and Image-Paradigms in Byzantine Culture. Moscow: Design. Information. Cartography, pp. 32–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lightbody, David Ian. 2011. Signs of conciliation: The hybridised “Tree of Life” in the Iron Age City Kingdoms of Cyprus. Cahiers du Centre d’Études Chypriotes 41: 239–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissovsky, Nurit. 2012. Sacred Trees—Holy Land. Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes: An International Quarterly 24: 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- Loukatos, Demetrios S. 1962. Άκουφος, Άγιος. In Θρησκευτική και Hθική Εγκυκλοπαιδεία. Directed by Athanasios Martinos. Athens: Athanasios Martinos, vol. 1, pp. 1224–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lounghis, Telemachos C. 2010. Byzantium in the Eastern Mediterranean: Safeguarding East Roman Identity. Nicosia: Cyprus Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Luig, Ute, ed. 2018. Approaching the Sacred. Pilgrimage in Historical and Intercultural Perspective. In Approaching the Sacred. Pilgrimage in Historical and Intercultural Perspective. Berlin: Topoi, pp. 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lusignan, Estienne de. 1580. Description de toute l’isle de Cypre. Paris: Guillaume Chaudiere. [Google Scholar]

- Marangou, Anna. 2019. Περπατώντας στην άκρη της γης μας. Athens: To Rhodakio. [Google Scholar]

- Marchesano, Louis. 2010. Charles Le Brun’s Constantine Prints for Louis XIV and Jean-Baptiste Colbert. In L’estampe au Grand Siècle. Études offertes à Maxime Préaud. Edited by Peter Fuhring, Barbara Brejon de Lavergnée, Marianne Grivel, Séverine Lepale and Véronique Meyer. Paris: École nationale des chartes/Bibliothèque nationale de France, pp. 463–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mariti, Giovanni. 1792. Travels through Cyprus, Syria and Palestine: With a General History of the Levant. Translated from the Italian. Charlestown: Pranava Books, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrojannis, Theodoros. 2015. Roman Temples of Kourion and Amathus in Cyprus: A Chapter in the Arabian Policy of Trajan. In Literature, Scholarship, Philosophy and History. Classical Studies in Memory of Ioannis Taifacos. Edited by Georgios A. Xenis. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, pp. 457–502. [Google Scholar]

- Menardos, Simos. 2001. Τοπωνυμικαί και λαογραφικαί μελέται. Nicosia: Cyprus Research Centre. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf, David M. 2009. Byzantine Cyprus, 491–1191. Nicosia: Cyprus Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, Maria. 2015. Ship graffiti in context: A preliminary study of Cypriot patterns. In Cypriot Cultural Details. Proceedings of the 10th Post Graduate Cypriot Archaeology Conference. Edited by Iosif Hadjikyriakos and Mia Gaia Trentin. Oxford and Philadelphia: Oxbow Books, pp. 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Miklosich, Francis, and Joseph Müller, eds. 1865. Acta et Diplomata Graeca Medii Aevi. Vienna: C. Gerold, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, F. Justus, ed. 1916. Ovid, Metamorphoses. London: Harvard University Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mlynarczyk, Jolanta. 1980. The Paphian Sanctuary of Apollo Hylates. In Report of the Department of Antiquities Cyprus. Cyprus: Department of Antiquities, pp. 239–52. [Google Scholar]

- Naaman, Abbot Paul. 2011. The Maronites: The Origins of an Antiochene Church. A Historical and Geographical Study of the Fifth to Seventh Centuries. Translated by the Department of Interpretation and Translation, Holy Spirit University. Trappist: Cistercian Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou-Konnari, Angel. 2000–2001. Ethnic names and the construction of group identity in medieval and early modern Cyprus: The case of Κυπριώτης. Κυπριακαί Σπουδαί 64–65: 259–75. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou-Konnari, Angel, and Chris Schabel. 2015. Limassol under Latin rule, 1191–1571. In Lemesos. A History of Limassol in Cyprus from Antiquity to the Ottoman Conquest. Edited by Angel Nicolaou-Konnari and Chris Schabel. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 195–361. [Google Scholar]

- Noonan, F. Thomas. 2007. The Road to Jerusalem. Pilgrimage and Travel in the Age of Discovery. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, Monique. 2017. Venice: City of merchants or city for merchandise? In The Routledge Handbook of Maritime Trade Around Europe, 1300–1600. Edited by Wim Blockmans, Mikhail Krom and Justyna Wubs-Mrozewicz. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 103–20. [Google Scholar]

- Oancea, Constantin. 2017. Chaoskampf in the Orthodox Baptism Ritual. Acta Theologica 37: 125–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogden, Daniel. 2013. Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ohnefalsch-Richter, Magda H. 2006. Greek Customs and Mores in Cyprus, with Comments on Natural History and the Economy and Progress under British Rule. Translated by Vassilis D. Angelis. Nicosia: Laiki Group Cultural Centre. First published 1913. [Google Scholar]

- Olympios, Michalis. 2013. Shared Devotions: Non-Latin Responses to Latin Sainthood in Late Medieval Cyprus. Journal of Medieval History 39: 321–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olympios, Michalis. 2015. Rummaging through ruins: Architecture in Limassol in the Lusignan and Venetian periods. In Lemesos. A History of Limassol in Cyprus from Antiquity to the Ottoman Conquest. Edited by Angel Nicolaou-Konnari and Chris Schabel. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 362–500. [Google Scholar]

- Pamuk, Şevket. 2001. The Price Revolution in the Ottoman Empire Reconsidered. International Journal of Middle East Studies 33: 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacostas, Tassos. 2005. In Search of A Lost Byzantine Monument: Saint Sophia of Nicosia. Επετηρίδα Κέντρου Επιστημονικών Ερευνών 31: 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- Papacostas, Tassos. 2012. Byzantine Nicosia, 650–1191. In Historic Nicosia. Edited by Demetrios Michaelides. Nicosia: Rimal, pp. 77–109. [Google Scholar]

- Papacostas, Tassos. 2015. Neapolis/Nemesos/Limassol: The rise of a Byzantine settlement from Late Antiquity to the time of the Crusades. In Lemesos. A History of Limassol in Cyprus from Antiquity to the Ottoman Conquest. Edited by Angel Nicolaou-Konnari and Chris Schabel. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 96–188. [Google Scholar]

- Papacostas, Tassos, Cyril Mango, and Michael Grünbart. 2007. The History and Architecture of the Monastery of Saint John Chrysostomos at Koutsovendis, Cyprus. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 61: 25–156. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoullos, Theodoros, ed. 1952. Εκ της αρχαιοτάτης ιστορίας του Πατριαρχείου Ιεροσολύμων. Το κείμενον αρχαίας παραδόσεως περί επισκέψεως της αγίας Ελένης εις Παλαιστίνην και Κύπρον. Νέα Σιών, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoullos, Theodoros. 1981. Το άσμα των διερμηνέων. Κυπριακαί Σπουδαί 45: 55–141. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorghiou, Athanasios. 1976. Byzantine Icons from Cyprus (Benaki Museum). Translated by Kay Tsitselis. Athens: Benaki Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorghiou, Athanasios. 2010. H χριστιανική τέχνη στο κατεχόμενο από τον τουρκικό στρατό τμήμα της Κύπρου. Nicosia: Holy Archbishopric of Cyprus. [Google Scholar]

- Papantoniou, Giorgos. 2012. Religion and Social Transformations in Cyprus: From the Cypriot Basileis to the Hellenistic Strategos. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Papantoniou, Giorgos. 2016. Cypriot ritual and cult from the Bronze to the Iron Age: A longue-durée approach. Journal of Greek Archaeology 1: 73–108. [Google Scholar]

- Patapiou, Nasa. 2009. Larnaka during Venetian rule from unpublished documents in the State Archive of Venice. Cyprus Today, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Patapiou, Nasa. 2010. H Aττάλου και η Μονή του Aγίου Γεωργίου. Σελίδες από την Ιστορία των Μαρωνιτών στην Κύπρο. Πολίτης Newspaper, December 12. [Google Scholar]

- Patapiou, Nasa. 2019. H Παναγία η Oδηγήτρια της Λευκωσίας. Καθεδρικός ναός των Oρθοδόξων από τον 4ο αιώνα έως το 1570. Ενατενίσεις 33: 101–7. [Google Scholar]

- Patlagean, Évelyne. 2014. O Ελληνικός Μεσαίωνας: Βυζάντιο, 9ος–15ος αιώνας. Translated by Despoina Lampada. Athens: Patakis. [Google Scholar]

- Perdikis, Stylianos, ed. 2004. Λογίζου Σκευοφύλακος, Κρόνικα. Nicosia: Holy Monastery of Kykkos Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Petra, Elissavet. 2014. Aνέκδοτο κοντάκιο του αγίου Ιακώβου του Πέρση. Βυζαντιακά 31: 129–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pieris, Michalis, and Angel Nicolaou-Konnari, eds. 2003. Λεοντίου Μαχαιρά, Χρονικό της Κύπρου. Παράλληλη διπλωματική έκδοση των χειρογράφων. Nicosia: Cyprus Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Pilides, Despina. 2012. A short account of the recent discoveries made on the hill of Ayios Yeorgios (PASYDY). In Historic Nicosia. Edited by Demetrios Michaelides. Nicosia: Rimal, pp. 212–14. [Google Scholar]

- Psychogiou, Eleni. 2008. “Μαυρηγή” και Ελένη, τελετουργίες θανάτου και αναγέννησης. Χθόνια μυθολογία, νεκρικά δρώμενα και μοιρολόγια στη σύγχρονη Ελλάδα. Athens: Academy of Athens. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, Jean, ed. 1981. Une famille de ‘Vénitiens blancs’ dans le royaume de Chypre au milieu du XVe siècle: Les Audet et la seigneurie du Marethasse. Rivista di Studi Bizantini e Slavi 1: 89–129. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, Jean, and Théodore Papadopoullos, eds. 1983. Le livre des remembrances de la secrète du Royaume de Chypre (1486–1469). Nicosie: Centre de Recherches Scientifiques. [Google Scholar]

- Rigsby, Kent J. 1996. Missing Places. Classical Philology 91: 254–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizopoulou-Egoumenidou, Euphrosyne. 2012. Nicosia under Ottoman Rule, 1570–1878, Part II. In Historic Nicosia. Edited by Demetrios Michaelides. Nicosia: Rimal, pp. 265–322. [Google Scholar]

- Römer, Claudia. 2001. The sea in comparisons and metaphors in Ottoman historiography in the sixteenth century. Oriente Moderno, Nuova Serie 20: 233–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellarios, Athanasios. 1868. Τα Κυπριακά. Athens: A. Sakellarios. [Google Scholar]

- Salibi, Kamal S. 1959. Maronite Historians of Mediaeval Lebanon. Beirut: American University of Beirut. [Google Scholar]

- Salvator, Louis. 1881. Levkosia, the Capital of Cyprus. Translated by the Chevalier de Krapf Liverhoff. London: C. Kegan Paul & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by Christopher Schabel. 2001, The Synodicum Nicosiense and Other Documents of the Latin Church of Cyprus, 1196–1373. Nicosia: Cyprus Research Centre.

- Scranton, Robert. 1967. The Architecture of the Sanctuary of Apollo Hylates at Kourion. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 57: 3–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seggiano, Ignazio da. 1962. L’opera dei Cappuccini per l’unione dei Cristiani nel Vicino Oriente Durante il Secolo XVII. Roma: Institutum Orientalium Studiorum. [Google Scholar]

- Simsky, Andrew. 2020. The Discovery of Hierotopy. Journal of Visual Theology 1: 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Skordi, Maria. 2019. Oι Μαρωνίτες της Κύπρου. Ιστορία και εικονογραφία (16ος–19ος αιώνας). Nicosia: UNESCO Chair on Digital Cultural Heritage, Cyprus University of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Smagas, Angelos, and Tryphonas Papagiannis. 2017. Εκκλησίες και εξωκκλήσια της δυτικής Καρπασίας. In Καρπασία: Πρακτικά B΄ Επιστημονικού Συνεδρίου. Edited by Panayiotis Papageorghiou. Limassol: Free United Karpasia Association, pp. 254–67. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Kyle. 2016. Constantine and the Captive Christians of Persia. Martyrdom and Religious Identity in Late Antiquity. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snelders, Bas, and Mat Immerzeel. 2012–2013. From Cyprus to Syria and Back Again: Artistic Interaction in the Medieval Levant. Eastern Christian Art 9: 79–106. [Google Scholar]

- Sophocleous, Sophocles. 2014. Cypriot Icons Before the Twelfth Century. In Cyprus and the Balance of Empires. Art and Archaeology from Justinian I to the Coeur de Lion. Edited by Charles Anthony Stewart, Thomas W. Davis and Annemarie Weyl Carr. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research, pp. 135–51. [Google Scholar]

- Soren, David, ed. 1987. The Sanctuary of Apollo Hylates at Kourion, Cyprus. Tuscon: The University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, Paul. 2016. The Serpent Column: A Cultural Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stouraitis, Yannis. 2017. Reinventing Roman Ethnicity in High and Late Medieval Byzantium. Medieval Worlds: Comparative & Interdisciplinary Studies 5: 70–94. [Google Scholar]

- Stylianou, Andreas, and Judith A. Stylianou. 1985. The Painted Churches of Cyprus. Treasures of the Byzantine Art. London: A. G. Leventis Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Tabak, Faruk. 2008. The Waning of the Mediterranean, 1550–1870: A Geohistorical Approach. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taft, Robert F. 1992. The Byzantine Rite: A Short History. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tannous, Jack. 2018. The Making of the Medieval Middle East. Religion, Society, and Simple Believers. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Theocharides, Ioannis P. 1987. Στοιχεία από την ιστορία της Κύπρου (μέσα του 17ου αι.). Δωδώνη 16: 209–23. [Google Scholar]

- Theodoropoulos, Panagiotis. 2021. Did the Byzantines call themselves Byzantines? Elements of Eastern Roman identity in the imperial discourse of the seventh century. Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 45: 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantaphyllopoulos, Demetrios D. 2015. Κωνσταντίνος και Μεγαλέξανδρος στα Ιωάννινα. Ιερο-κοσμικός χώρος στο Μεταβυζάντιο. In Aφιέρωμα στον ακαδημαϊκό Παναγιώτη Λ. Βοκοτόπουλο. Edited by Vasilis Katsaros and Anastasia Tourta. Athens: Kapon, pp. 527–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tsirpanlis, Zacharias N, ed. 1973. Aνέκδοτα Έγγραφα εκ των Aρχείων του Βατικανού (1625–1667). Nicosia: Cyprus Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Tsirpanlis, Zacharias N. 2006. O Κυπριακός Ελληνισμός της Διασποράς και οι Σχέσεις Κύπρου-Βατικανού (1571–1878). Thessaloniki: Ant. Stamoulis. [Google Scholar]

- Tsumura, David T. 2005. Creation and Destruction. A Reappraisal of the Chaoskampf Theory in the Old Testament. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Tully, Caroline Jane. 2018. Cultic Life of Trees in the Prehistoric Aegean, Levant, Egypt and Cyprus. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Harold W. 1979. From Temple to the Meeting House: The Phenomenology and Theology of Places of Worship. The Hague: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor, and Edith Turner. 1978. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture. Anthropological Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Villamont, Jacques de. 1609. Les Voyages du Seigneur de Villamont. Paris: Claude Lariot [Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation, B-166]. First published 1596. [Google Scholar]

- Vionis, Athanasios K., and Giorgos Papantoniou. 2019. Central Place Theory Reloaded and Revised: Political Economy and Landscape Dynamics in the Longue Durée. Land 8: 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walsh, Michael J. K. 2006. Martyrs and Mariners: Some Surviving Art in the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, Famagusta, Cyprus. Mediterranean Studies 15: 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Michael J. K. 2007. “On of the Princypalle Havenes of the See”: The Port of Famagusta and the Ship Graffiti in the Church of St George of the Greeks, Cyprus. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 37: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, Christopher. 2006. The Iconography of Constantine the Great, Emperor and Saint (with Associated Studies). Leiden: Alexandros Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wartburg, Marie-Louise von, and Yiannis Violaris. 2009. Pottery of a 12th-Century Pit from the Palaion Demarcheion Site in Nicosia: A Typological and Analytical Approach to a Closed Assemblage. In Actas del VIII Congreso Internacional de Cerámica Medieval en el Mediterráneo. Edited by Juan Zozaya, Manuel Retuerce, Miguel Ángel Hervás and Antonio de Juan. Ciudad Real: Asociación Espanõla de Arqueología Medieval, vol. 1, pp. 249–64. [Google Scholar]

- White, Sam. 2011. The Climate of Rebellion in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xoplaki, Elena, Jürg Luterbacher, Sebastian Wagner, Eduardo Zorita, Dominik Fleitmann, Johannes Preiser-Kapeller, Abigail M. Sargent, Sam White, Andrea Toreti, John F. Haldon, and et al. 2018. Modelling Climate and Societal Resilience in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Last Millenium. Human Ecology 46: 363–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, Robert J. C. 1995. Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Philip H. 2005. The Cypriot Aphrodite Cult: Paphos, Rantidi, and Saint Barnabas. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 64: 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Saint Helen | Cross | Drought |

|---|---|---|

| Founder of the monastery | Tree of Life | Evil |

| Saint Helen/Nicholas | Cats | Snakes |

|---|---|---|

| Divine protectors/patrons of the monastery | Protectors | Evil |

| Saint James the Persian | Cypress | Snake |

|---|---|---|

| Martyr/holy healer | Sacred Tree | Guardian of the sacred tree |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kyriacou, C. Saints, Sacred Trees, and Snakes: Popular Religion, Hierotopy, Byzantine Culture, and Insularity in Cyprus during the Long Middle Ages. Religions 2021, 12, 738. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090738

Kyriacou C. Saints, Sacred Trees, and Snakes: Popular Religion, Hierotopy, Byzantine Culture, and Insularity in Cyprus during the Long Middle Ages. Religions. 2021; 12(9):738. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090738

Chicago/Turabian StyleKyriacou, Chrysovalantis. 2021. "Saints, Sacred Trees, and Snakes: Popular Religion, Hierotopy, Byzantine Culture, and Insularity in Cyprus during the Long Middle Ages" Religions 12, no. 9: 738. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090738

APA StyleKyriacou, C. (2021). Saints, Sacred Trees, and Snakes: Popular Religion, Hierotopy, Byzantine Culture, and Insularity in Cyprus during the Long Middle Ages. Religions, 12(9), 738. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090738