Abstract

There is a mounting body of evidence for somatic exchange in burial practices within later British prehistory. The title of the present paper was sparked by a recent article in The Times (Tuesday 1 September 2020), which contained a description of human bone curation and body mingling clearly present in certain Bronze Age funerary depositional rituals. The practice of mixing up bodies has been identified at several broadly coeval sites, a prime example being Cladh Hallan in the Scottish Hebrides, where body parts from different individuals were deliberately mingled, not just somatically but also chronologically. This paper’s arguments rest upon the premise that somatic boundary crossing is reflected in Iron Age and later art, especially in the blending of human and animal imagery and of one animal species with another. Such themes are endemic in La Tène decorative metalwork and in western Roman provincial sacred imagery. It is possible, indeed likely, that such fluidity is associated with deliberate subversion of nature and with the presentation of ‘shamanism’ in its broadest sense. Breaking ‘natural’ rules and orders introduces edge blurring between material and spiritual worlds, representing, perhaps, the ability of certain individuals (shamans) to break free from human-scapes and to wander within the realms of the divine.

The premise of this paper is the growing weight of evidence for subversion of the ‘real’ in the production and consumption of imagery in both Iron Age, La Tène art and in the sacred depictive repertoire of the western Roman provinces. In both arenas, the representation of bodies sometimes challenges ‘normative’ visual recognitions and twists them so that they transgress the boundaries of gender and species. Additionally, recent studies of La Tène metalwork designs introduce other dimensions of artistic expression, notably the manipulation of space, time and— possibly—even worlds. One of the nodal issues of such a tenet is the recognition that what may be presented to the spectator’s gaze is the process of change, a subversion of norms, perhaps considered by the artist as more important in visualisation than change itself. My intention with this paper is to consider a selection of key images that appear to exemplify these freeze-framed change processes and then to consider the possible contexts for such imagery, not least the likelihood that the projection of shamanism might be a prime issue in the production of images that twist, subvert and meddle with the realities of the material world.

1. Dissolving Identities: Fluidity and Subversion in the British Bronze Age

Before proceeding to the ‘guts’ of the paper, I want to cast the net a little wider, for Iron Age and Roman-period images are not the only evidence for somatic subversion. Certain British Bronze Age burial customs exhibit the deconstruction, mingling and reincorporation of dead bodies to become different beings, associated with different timeframes, so that the remains of the earlier dead may be curated and then mixed up with other, later bodies and dwelling places. A prime example of such behaviour is represented at Cladh Hallan on South Uist in the Western Isles of Scotland, a site that dates to about 1000 BC (Parker Pearson et al. 2005; Booth et al. 2015). Bodies of the dead here were deliberately mummified and sometimes curated for up to 500 years before being interred beneath the houses of the living. The most likely method of preservation was first gutting and then placing them in an acidic environment, such as a peat bog (as evidenced by the state of the bones, which showed signs of severe demineralisation) (see Aldhouse-Green 2015a, pp. 50–65; Giles 2020, pp. 52–71 for an explanation of bog body preservation).

So, it appears that the bodies of certain deceased individuals were carefully treated in complex ritual ways, the end processes of which involved their removal from swamps after the preservative process had turned them into bog bodies, the wrapping of their remains and their curation over centuries before their deposition in the foundations of their descendants’ dwellings. It seems that underlying these complex procedures was the notion of connection: the perceived need to link the past and the present, the long-dead and the living. By changing dead bodies into lasting somatic memorials, the ancestors were enabled to reach out and engage with those living up to half a millennium later. However, connections were not only made over time; there is startling evidence, too, that these mummified bodies were treated in ways that defied and subverted their somatic identity. One interment, in particular, had been subject to some weird (to us) treatment prior to its final burial in house foundations, for it represented the remains, not of one, but of a mingled male ‘person’ made up of the body parts of three individuals: the head and neck of one, the jaw of a second and the remainder of the body that of a third. Not only were the remains those of a tripartite being but the chronology was also tampered with, for while the head was curated for about 300–400 years before being finally interred, the body was that of someone who died hundreds of years earlier. So, this composite body represents somatic exchange in both the mixing-up of body parts and in time-bending, not only in the original mummification but in the staggered chronology of curation.

Whatever the thinking behind such complex manipulation, it is clear that an important element was the subversion of original identities and of time itself. Was this an act designed to blow boundaries apart and present fluidity and connections in order to enable the crossing of thresholds? If so, then the ultimate deposition as a foundation ‘sacrifice’ seems to have fed into the significance of border porosity. The construction of houses penetrated ‘virgin’ land and transgressed the boundaries between the wild landscape and the order of the built environment. The appeasement of the local spirits by subverting human borders—both in terms of people’s bodily identity and the time–space continuum—may have been deemed an essential ritual for the settlement to thrive in borrowed space.

The odd, time-warping treatment of bodies was by no means confined to the Western Isles. Recent work by archaeologists led by Joanna Brück at Bristol University has thrown new light on funerary rituals associated with the building of Bronze Age houses and the interaction between the living and the dead (Bridge 2020, p. 15). There is evidence, for example, at Ingleby Barwick in North Yorkshire, that a woman’s body was interred with the remains of at least three other individuals: a pubescent female and an adult man and woman, perhaps quarried from a cache of curated remains hoarded to supply material for burial rituals. As at Cladh Hallan, there is evidence for the bending or subversion of chronology, for the human remains here are estimated as being more than 50 years older than objects buried with them. The interpretation offered by researchers at the site is that funerals were the context for the distribution of bones so that mourners could remember their dead and keep them alive through memory. Crucially, such events again took place at boundary places, such as house foundations, perhaps, as postulated for Cladh Hallan, to represent fluidity between different people in different time zones.

2. Connectivity in Iron Age European Figural Art

It has long been recognised that La Tène decorated metalwork is shot through with ‘surrealism’, the manipulation of themes associated with observed nature to be reborn within a repertoire of strange and powerful imagery. In my opinion, and that of other scholars, European Iron Age art was primarily a symbolic, religious presentation of the supernatural. It may even be, as John Creighton has suggested with respect to coin imagery (Creighton 1995), that the inspiration behind such art was directly associated with or driven by professional clergy, including the Druids of Gaul and Britannia (Aldhouse-Green 2010, 2021), who acted as conduits between the material and spiritual worlds. La Tène decorated metalwork represents a superlative artistic skillset combined with the mining of an incredible imaginative repertoire of symbols and images worthy of comparison with Greek myth. In fact, I would go so far as to argue that some of the more complex designs perhaps referenced ancient Iron Age oral traditions of storytelling. This is particularly relevant to one object considered later in this paper, the Gundestrup cauldron. First, I want to discuss three pieces of metalwork, each of which brings a different dimension to the theme of dissolved identities, shapeshifting and the subversion of time–space continua, from Weiskirchen and Reinheim in Germany and Tal-y-Llyn in North Wales.

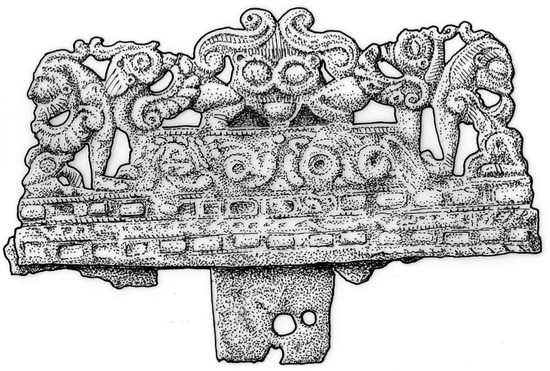

Sometime in the late fifth century BC, a skilled bronzesmith produced a highly complex belt clasp inlaid with red coral (Figure 1) (Megaw 1970, pp. 69–70, no. 62; Megaw and Megaw 1989, p. 66, fig. 65), which was perhaps worn by a high-ranking warrior in life, and after whose death it was placed in his grave with him (though, of course, the belt might have simply been placed with the corpse as a mark of honour). Inside the tomb, one of three barrows at Weiskirchen in Germany was a wooden chamber in which a number of rich grave goods were deposited, including a gold plaque from a brooch decorated with human faces (Megaw 1970, pp. 62–63, no. 46, pl. IIa) and a short iron sword in its decorated bronze scabbard. The belt clasp has been described by Vincent Megaw (1989, p. 66) as decorated with ‘Siamese twin sphinxes’ supporting a central human head. However, might not the piece have represented something more challenging—the idea of movement and differing perspectives in a single static image? Laurent Olivier (2014) and Jody Joy (2015, p. 39, fig. 19) have posited the notion that these figures may not represent three beings within a single plane but, instead, a single one envisaged from different viewpoints; in other words, what the artist intended the spectator to see was ‘the left- and right-hand sides of the same creature, together with a frontal view of its human-like face’. If this is right, and it is a persuasive argument, it means that the ‘gaze’ involved the understanding of complex design that subverted the single dimension and made one figure ‘move’ within its frame to display itself as if it were a living being—not just an image stuck within the rigidity of its bronze casing but leaping about, turning this way and that, to represent its essential vitality. In this way, what looks like a multiple being converts, by sleight of hand, into self-connected and animated oneness. What was the thinking behind such manipulation of imagery in space (and time)? Was the production of this ‘magic show’ merely an intellectual exercise or was something more profound intended? I suspect that one factor in the presentation of the weird and wonderful was the understanding that ancestral and other spirits were not bound by terrestrial laws of space and time, so it was apt that supernaturally driven imagery displayed similar freedoms beyond the bounds of what humans perceive as the real.

Figure 1.

Coral-inlaid bronze belt clasp from a man’s tomb at Weiskirchen, Germany; late fifth century BC. © Nick Griffiths.

Fluidity between forms of being is depicted in so much of Iron Age art. The issue of shapeshifting has already been touched on, but some pieces exhibit the merging of human and animal forms par excellence. In 1954, a rich female grave, dated to the early fourth century BC, was discovered at Reinheim (Germany) (Miron 1986, pp. 110–11). As at Wieskirchen, the body was interred in a wood-lined tomb beneath a barrow, accompanied by rich grave goods, including a mirror and a jewellery box full of at least 200 pieces. A quantity of the decorated metalwork buried with her exhibits shapeshifting imagery. The lid of a large bronze wine flagon bore a figure of a horse with a bearded human face (Aldhouse-Green 2001a, p. 207, fig. 1; 2004, p. 161, fig. 6.7) (Figure 2). (This is a theme taken up in later Iron Age coin art, where galloping steeds with human faces pulling chariots driven by horsewomen were frequently depicted, particularly among Breton tribes (Duval 1987, p. 46, 5B; Aldhouse-Green 2006, p. 30, fig. 2). The Reinheim horse has two other boundary-crossing features: its rounded ears are not equine but belong, perhaps, to a big cat, such as a leopard, or even a bear; it has three hooves and one foot that appears to end in human toes.

Figure 2.

Human-faced horse decorating the lid of a wine flagon from the Reinheim grave. © Anne Leaver.

The gold ring jewellery (neckrings or torcs and armrings) also features the fluidity and connectivity between human and animal forms, for a recurrent decorative theme is the merged images of a woman, laid out as if for burial, her arms folded on her breasts, and a bird of prey that perches on her head, only its long-beaked head and wings visible, as if emerging from her body (Megaw 1970, pp. 79–80, pls. 79–80; Megaw and Megaw 1989, pp. 90–91, figs. 116, 117) (Figure 3). Is it possible that the emergence of the bird reflects the dead woman’s apotheosis? Might the juxtaposed motifs of corpse and raptor represent something darker, though—the claiming of the dead for the underworld? It is tempting to imagine the death of someone, clearly significant in her society while living, as an apocalyptic event wherein the spirits of the otherworld were perceived to absorb the fleshly remains and thus deliver her to their realm. There is clearly a hidden ‘storyline’ written in the woman’s grave goods. The human/horse decorating the wine flagon might represent what might be identified as a shamanic figure, reflecting the intoxicant properties of strong wine that might enable altered states of consciousness and ‘soul flight’ between worlds. It may even be that the Reinheim woman was herself a spiritual leader, a shaman who had the ability to move between the material and supernatural worlds, and that she earned her grand tomb by reason of her skill as a religious practitioner. This notion has been explored in work by Chris Knüsel (2002).

Figure 3.

Detail of gold ring jewellery from a woman’s grave at Reinheim, Germany; fourth century BC. © Paul Jenkins.

The third piece of La Tène decorated metalwork comes from a very different time and geographical location from those found at Weiskirchen and Reinheim. It comprises a broken trapezoid plaque (originally one of a pair, the second now lost) of very thin sheet bronze, once mounted on a backplate, probably a shield. It is part of a hoard of metalwork, some military (including shield bosses and horse harnesses), found at Tal-y-Llyn, Merionethshire (North Wales), which includes both insular La Tène and Romano-British material. The cache includes objects of varying dates and is generally accepted as a metalworker’s collection of scrap to be melted down and recast.

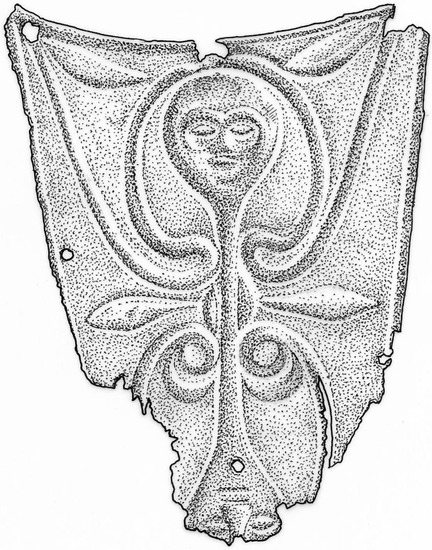

The surviving plaque is relevant to this study for its depiction of two identical human heads with hair en brosse, vertically opposed and joined together by a single long, thin neck (Savory 1976, p. 56, pl. IIIa). While Savory put a date in the Middle Iron Age (c. 300–200 BC) on the hoard, a more recent study (Macdonald 2007, pp. 160–61) suggests that it may date to sometime after the Roman conquest of Britain of the mid-first century AD, a view supported by the presence of zinc (adopted as an add-on in bronzemaking in the Roman period) in some of the copper alloy used in the hoard. The Tal-y-Llyn plaque is so fragmentary that only one of the two heads and the neck survive in toto; only the chin, mouth, most of the nose and the lower part of the eyes of the second head remain. Still, this is enough to indicate the identicality of the complete plaque. Swirling designs enclose both heads and there is a horizontal motif that serves to divide the two. What is depicted here is the essence of connection, separation and fluidity between the two heads. An important factor in unlocking their significance is their opposition: one is upside down in relation to the other.

I incline to the opinion, one shared by Ian Armit (2009), that a reasonable interpretation of the Tal-y-Llyn imagery is that it depicts the relationship between the worlds of the living and the dead. In speaking of the belief systems of the northern Sámi people, Richard Bradley discusses their view of these two realms and, in particular, their envisioning of the underworld as a mirror image of the mundane domain inhabited by the living. Bradley, building on Tim Ingold’s work, notes the frequent Sámi use of the inverted boles of trees as material for sacred image-making, and their credo that the reversal of features between the two worlds involves the imagining that dead people walked upside down, their feet in the footsteps of the living (Bradley 2000, p. 12, after Ingold 1986, p. 246). The interpretation of the opposed twin heads as imagery of two worlds, the upper and lower, the abodes of the living and the dead, raises a number of separate but related issues. The Tal-y-Llyn heads (Figure 4) might simply represent a generic image or, instead, it might be that they are depictions of a specific person, and one possibility is that they are ‘portraits’ of a shaman, someone who could traverse the divide between the earth and otherworld dimensions. Shamans display fluidity and subversion in their ability to take soul flight and engage with the denizens of the otherworld (Vitebsky 1995, pp. 38–39; Pentikäinen 1998, pp. 26–48; Price 2001; Séfériadès 2018). The Tal-y-Llyn double image might therefore represent the two personae of a local shaman at the point of his (or her) transition between worlds. Moreover, it should not be forgotten that there were originally two of these plaques, which might contribute further to the notion of ‘double spirit’ shamanic identities (Aldhouse-Green 2001b; Aldhouse-Green and Aldhouse-Green 2005, p. 205; Jacobs et al. 1997).

Figure 4.

Double-headed plaque from a hoard of late Iron Age or Roman period bronzes, from Tal-y-Llyn, Merionethshire, North Wales, UK. © Nick Griffiths.

There is another issue regarding the Tal-y-Llyn images that has relevance to their interpretation: their military context as shield adornments (martial art). Melanie Giles (2012) has argued convincingly for the importance of psychological warfare as an interpretation for the dramatic imagery on Iron Age swords, shields, war trumpets and other military regalia. In particular, the recurrent use of red enamel and red coral to signify drops of fresh blood bears testimony not just to the love of display but also to the visual power with which arms and armour might have been imbued. This power would have been designed both to bolster up and infuse the courage of the warrior and to put fear into the heart of the enemy. The combination of an aggressive brandishing of weapons and shields, some bearing fearful images of death, and the yells of combat undoubtedly employed in battle puts psycho warfare centre stage. Even in the case of small images, like the Tal-y-Llyn heads, the bearer of the shield upon which the plaques were mounted might have been comforted by their talismanic force, even if they were not highly visible to his opponent. Furthermore, of course, when new, the relief imagery of the heads would have stood out and glinted in the sun and so would clearly have been seen in close, hand-to-hand single combat. Maybe one visual message radiating out from these double heads was the recognition that though battle could result in death, the warrior in possession of such protective power would find solace in his rebirth in the spirit world, especially if so guided by a shamanic helper. Finally, the possible latest Iron Age or Roman conquest period date of the Tal-y-Llyn head plaques may be significant in terms of the broader context of the burgeoning of ‘frontier art’ in first century AD Wales (Davis and Gwilt 2008). It has been cogently argued that the stress of encroaching romanitas, particularly in south Wales in the later first century AD, was instrumental in an increase in high status and military decorated metalwork, with red hot-glass and enamel especially prominent. It may be that this represented a kind of ‘resistance’ art. Moreover, I wonder whether the recent discovery of a chariot burial in Pembrokeshire (BBC 2019; Hole 2020) might be part of the same local tribal ‘defiance’, for not only was this tomb situated hundreds of miles away from Brigantian territories in Yorkshire where nearly all other chariot burials have been found (one is from Newbridge in Scotland) but the Welsh example was centuries later, belonging to the mid-late first century AD, whereas those in the north belong to the middle Iron Age (400–200 BC). So, this deviant burial might have been that of a foreigner, but could it also be interpreted as a form of deliberate Britannitas in the face of the Roman threat? If the Tal-y-Llyn plaques can be dated to the post-conquest period, then it could be that the martial art of the shield represented something akin to what was going on in south Wales at this period.

3. Fluidity and Shamanism on the Gundestrup Cauldron

‘What comes after them is the stuff of fables—Hellusii and Oxiones with the faces and features of men, but the bodies and limbs of animals. On such unverifiable stories I will express no opinion’(Tacitus, Germania 46; trans. Mattingly 1948, p. 140)

At the end of his treatise on the Germani (by which he meant those Germanic communities whose territories lay east of the Rhine), Tacitus ventured into his furthest explorations, speaking not only of the fabled Hellusii and Oxiones but of a people called the Fenni who, he reported, lived close to the border with Sarmatia, a land east of the Danube. In his history of Roman Britain, David Mattingly (2006, p. 122) describes the deployment of Sarmatian cavalry by the emperor Marcus Aurelius in his attempt to control trouble in Britannia in the 170s AD. Mattingly speaks of the Sarmatians as ‘one of the most dangerous trans-Danubian peoples’. Tacitus is clearly alluding to what he considered to be the wild fringes of human civilisation, from hearsay and rumour (perhaps from travelling merchants). The important issue in the present context is that while Classical mythology is steeped in fantastic creatures that blend human and animal in a kind of supernatural soup, the wild otherness of far-off communities, way beyond the bounds of the Roman empire, was expressed by Tacitus (and other chroniclers, including Horace and Herodian) in terms of the grotesque somatic mingling of species.

The complex and wonderful imagery that decorates the great gilded silver late Iron Age cauldron from Gundestrup in Jutland is well-documented (Kaul 1991; Olmsted 1979). Probably dating to between 150 and 50 BC (Hunter et al. 2015, p. 262), and capable of holding up to 130 L of liquid, this vessel was found in 1891, deliberately dismantled into its 13 constituent plates and carefully deposited on a dry islet in the middle of a peat bog, presumably as part of a ritual event. The cauldron was constructed of 7 outer and 5 larger inner rectangular plates that form its walls, with a 13th circular base plate, which had been a phalera (a circular piece of decorative hose harness) before its reuse by the cauldron makers. Each plate is highly decorated in repoussé work, with images of human, animal and composite figures. The outer plates display busts of what are probably deities, but the inner plates appear to represent scenes from a narrative, perhaps a cultic, mythical tale that—in its way—might have been as significant to its producers and users as a written myth and, indeed, might have been deployed as a memory tool for a professional storyteller. The vessel has rightly been termed ‘a visual feast’ (Hunter et al. 2015, p. 270)

The cauldron’s geographical and cultural origins are complicated. Some iconographical detail (such as the weapons and armour worn by warriors depicted on one scene and the images of deities, such as Taranis, the wheel god, and Cernunnos, the antlered god) supports arguments for Gaulish influence. If it were to have been commissioned for use in Gaul, it could have been carried off as plunder by a warring northern tribe, such as the Germanic Cimbri, whose lands lay in northern Jutland, and who, as we know from written sources, raided Gallic territories. (Tacitus Germania 37; King 1990, pp. 40–41). However, some of the craftspeople responsible for producing the images (several different artists’ hands have been identified) had at least heard tales of highly exotic—though inaccurately depicted—beasts, including elephants, leopards and hyenas. Some elements of the iconography bear comparison with northern European traditions. The curveball to be thrown into the mix is that large-scale European Iron Age silverwork was almost invariably carried out in the workshops of Thrace, on the Black Sea.

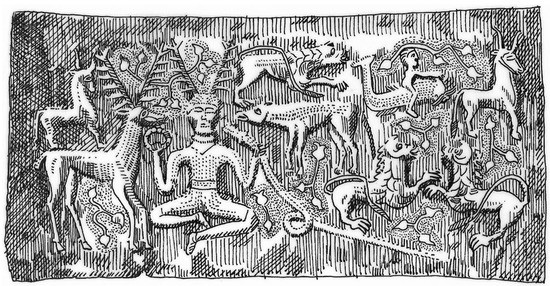

It is the imagery on one of the cauldron’s inner plates (Figure 5) that is of particular relevance to the themes of connectivity, porous boundaries and shamanism, for it clearly reflects the process of shapeshifting between animal and human form and, indeed, may represent the very act of transition. In the centre, although not precisely so positioned on the plate, is a human figure, seated cross-legged in the so-called ‘yogic’ position. The figure is almost certainly male, with no hint of female breasts. Around his neck is a plaited torc, and he holds up another, identical one in his right hand. In his left, he grasps a long serpent, gripping it just behind the head (as if to avoid being bitten, or simply as a sign of control over it). Both the cross-legged figure and his snake exhibit skin-turning: the reptile has the head and curly horns of a ram; the man sprouts antlers from his hair (each bearing six tines), and standing very close beside him is a stag (whose antlers possess seven tines each). The artistic treatment of the antlers is identical on the man and the beast, but the stag’s extra antler tines are a mark of a peak alpha male. I incline to the view that the image-maker’s intention was to display the actual act of shape change between person and stag. The discrepant number of tines on both sets of antlers suggests the direction of change: from human to animal form. The intimacy between the two images is intense; the stag faces the man, whose held torc skims the animal’s lower jaw; the man has adopted his companion’s antlers, yet his are yet to achieve full maturity. The other striking linkage between the two figures lies in the detail of the man’s clothing and the stag’s pelt and ribs; they are all depicted in identical stripes. So, subtle messages associated with movement, time and change are being expressed. The man’s face picks up on his ‘yogic’ pose; it is composed and serene, as if he is experiencing an out of body experience, an altered state of consciousness whereby, in a trance state, he can take soul flight—as a shaman—to connect with the spirits, the stag persona acting as his conduit to the otherworld (Aldhouse-Green 2001b).

Figure 5.

Detail of inner plate depicting an antlered ‘human’ figure, from the late Iron Age silver cauldron from Gundestrup, Jutland, Denmark. © Paul Jenkins.

Later in this paper, it is shown that the stag/human/snake image is by no means confined to the Gundestrup cauldron but appears several times in Roman Gaul and occasionally, too, in the westernmost Roman province of Britannia. However, before leaving the cauldron, it is pertinent to point out that the trope of transformation was not confined to the inner plate just discussed. It is presented on the other cauldron’s inner plates too, notably on the so-called ‘warriors scene’. Represented on the lower register is a procession of infantrymen marching left (for the viewer) towards a gigantic figure in human form, who seizes each one in turn, dips him into a vat and releases them transformed into cavalrymen who gallop off to the right in the upper register, divided from the lower by a horizontally positioned ‘sacred’ tree (Kaul 1991, p. 23, fig. 17). The link with the stag/antlered man plate is displayed by the presence, once again, of the ram-horned serpent, perhaps the shaman’s animal helper (or even the shaman himself), enabling transition over the threshold between the world of the living and the dead warriors who, perhaps, underwent a rebirth to fight again in the next world. The snake leads the line of horsemen as if to usher them into the realm of the spirits. (The same hybrid creature appears on a third of the inner plates, this time in company with a bearded ‘god’ figure being offered a large chariot or cartwheel by a small horned ‘acolite’ (Kaul 1991, p. 22, fig. 16).

The Gundestrup cauldron’s imagery discussed here abounds in threshold motifs. Antlers themselves signify change, the passage of time and the rhythm of the seasons. The sacred tree on the ‘warriors’ plate divides the upper and lower worlds; the vat of regeneration appears to transform foot soldiers into horsemen; composite creatures echo the theme of transition; and the most recurrent figure, the ram-headed serpent, supplies continuity to the mythic story (appearing on three of the ‘narrative’ scenes) whilst itself redolent with fluidity, connection and subversion of the ‘real’. The argument that this peculiar image represents a key component of a mythic composition is strengthened by its continued presence in Gallo-British sacred imagery into the Roman period, as is the likelihood that the sacrality of the cauldron’s figural art was driven by essentially Gaulish traditions of belief. Before leaving this remarkable and unique cauldron, I want to end with a quote from Celts, Art and Identity, the catalogue accompanying the eponymous exhibition held in 2015 at the British Museum in London:

“This one object shows artistic influences from Celtic, Thracian and Asian styles, was made in southeast Europe, and ended up in a Danish bog. We are dealing here with a connected world …”.(Hunter et al. 2015, p. 270)

4. From Gundestrup to Gloucestershire: The Corinium Sculpture

In his seminal work Contributions à L’Étude des Divinités Celtiques, Pierre Lambrechts (1942) was one of the first scholars to make connections between Gallo-Roman sacred images displaying persons seated in the ‘yogic’ position (i.e., cross-legged), their wearing of antlers and their recurrent association with ram-headed serpents (Lambrechts 1942, pp. 21–32, 45–63). This iconographic association is relatively common in Gaul but vanishingly rare in Britannia; the only certain stone image that bears a strong resemblance to the Gundestrup being is on a small plaque (Figure 6), a relief carving made of local limestone from Corinium (Roman Cirencester) in the Gloucestershire Cotswolds (Henig 1993, no. 93, pl. 26). Although the surface is worn, it is possible to identify a central ‘human’ figure seated cross-legged, with vestigial knobs of antlers on his head (perhaps signifying youth or seasonality). The most striking element, though, is the presence of two large ram-headed serpents grasped by the neck in his hands and, seemingly, replacing his legs. The proportions are interesting, for here the snakes are very large in proportion to the central human image. What is more, the reptiles appear each to be eating from an open bag of fruit or corn.

Figure 6.

Romano-British limestone relief carving of a composite human/animal figure, with antlers and ram-headed snakes; from the Roman town of Corinium (Cirencester), Gloucester, UK. © Nick Griffiths.

I suspect that this sculpture was commissioned by an immigrant from eastern Gaul rather than from a Briton. There is evidence for the presence of at least one high-ranking individual from Reims at Corinium: Lucius Septimius, a governor of Britannia Prima (one of four provinces into which Britain was divided by the emperor Diocletian in AD 296) (Collingwood and Wright 1976, pp. 30–31, no. 103). However, a British origin for the image type should not be dismissed since a late Iron Age silver coin from the English Midlands depicts an antlered human head (Boon 1982). The fluidity between species is particularly marked on the Corinium image. Not only does the central figure sprout antlers but the ram-headed snake, which, at Gundestrup, was a companion of the antlered being, has—at Corinium—morphed further to merge seamlessly and take the place of human lower limbs. So, the whole composition is full of restlessness, movement, change and porous boundaries. Humanitas has been triply subverted.

A further search into cognate imagery in Gaul reveals yet another twist of liminality: that of gender. It is likely that the antlers on Gaulish depictions (and probably also at Gundestrup) are those of red deer. In life, only the males grow antlers (the only species where both genders have antlers is the reindeer), but, occasionally, antlered human forms represented in Gallo-Roman figural imagery as copper alloy figurines, are women. One striking example, with no firm provenance but thought to be from the region of Clermont Ferrand (in south central France), depicts a mature woman seated cross-legged on a chair or stool, with large antlers sprouting from her hair (Figure 7). She holds a patera (offering plate) in her right hand while her left arm supports an immense cornucopiae overflowing with fruit (Lambrechts 1942, p. 25; Boucher 1976, no. 317; Aldhouse-Green 2001b, p. 87, fig. 7.10). These extra elements of subversion and transition are emphatically rendered on the multi-layered complexity of a stone sculpture from an important Gallo-Roman temple in Burgundy, now explored.

Figure 7.

Gallo-Roman figurine of an antlered goddess. Provenance uncertain but thought to be from the region of Clermont-Ferrand, Auvergne.

5. Transformation, Liminality and Gender Transference at Bolards

- ‘For spirits when they please

- Can either sex assume, or both: so soft

- And uncompounded is their Essence pure,

- Not tied or manacled with joint or limb,

- Nor founded on the brittle strength of bones,

- Like cumbrous flesh; but in what shape they choose

- Dilated and condensed, bright or obscure,

- Can execute their aery purposes,

- And works of love or enmity fulfil’

(John Milton, Paradise Lost I, lines 423–431: Irwin 1962, pp. 31–32)

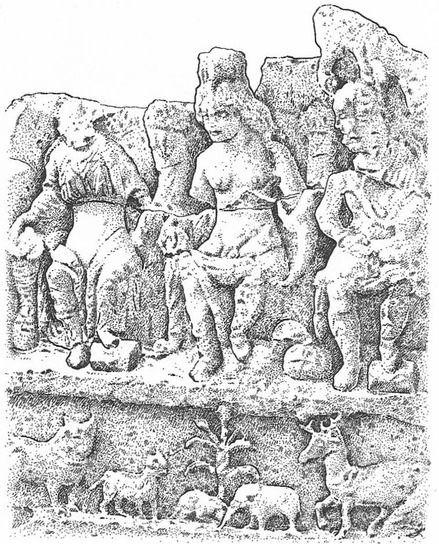

In a previous publication (Aldhouse-Green 2004, pp. 205–6), I highlighted a curious and complex piece of Gallo-Roman religious sculpture from the town at Bolards (Nuits-Saint-Georges) in Burgundy. Significantly, this settlement and its sanctuary were deliberately founded at the intersecting frontiers of three powerful eastern Gaulish tribes: the Sequani, Lingones and Aedui. The great temple was situated on the site of thermal springs and it was clearly a place of pilgrimage for the sick. There is evidence for its significance before the imposing stone building was constructed in the first century AD (Planson and Pommeret 1986, pp. 26–31). Investigation of the southern part of the religious precinct revealed what may have been the focal image; it has been dated to the second century AD. The stone relief carving (Figure 8) is divided into an upper and lower register. On the lower is a frieze depicting five animals centred upon a tree at the midline. The outermost creatures are a bull and a stag; in front of the bull is a dog, and before the stag is a wild boar, while in the middle, facing the boar, is a hare (both the boar and hare are apparently grazing beneath the tree). So, presented here is a deliberate amalgam of wild nature and domestication, separated by the tree, which, perhaps, represents the conduit or portal between the two states of being. On a jutting shelf above the animal frieze sit three much larger, anthropomorphic figures. On the viewer’s left is a woman dressed in a long flowing robe, with a cornucopiae and a basket brimming with food, above which she holds a patera; the central figure depicts a long-haired, semi-clad person with female breasts and male genitals, wearing a mural crown that may signify guardianship of the town and its temple; the third image is that of a bearded male. He is triple-faced, gazing front and to each side, and on his head are antlers. His emblem is a sack of bread (Deyts 2001, pp. 129–42; Pommeret 2001, no. 82, figs. 8 & 9).

Figure 8.

Stone carving depicting three ‘deities’, including a hermaphroditic image and a triple-faced person with antlers; from a Gallo-Roman temple at Bolards (Nuits-Saint-Georges), Burgundy, France. © Anne Leaver.

Bolards was a liminal, ‘thin’, threshold place; like many other Gallo-Roman temples (and some Iron Age ones, including the ‘war sanctuary’ at Gournay-sur-Aronde (Brunaux 1986, p. 7), it was deliberately sited in the no man’s land on the edge of several tribal polities. The shrine’s function was to act as a powerhouse for healing, a place the spirits visited, engaged with its priests and enabled the transformative process of curing the sick. Thus, the crossing of borders—between territories, between physical states and between the worlds of sacred and profane—all converged in this thermal sanctuary, which acted as a crossing place, a fluid and interactive zone, where boundaries might be dissolved. Furthermore, what of the sculpture, packed as it was with contradictory, yet fluid and connected symbolism? The zoomorphic frieze references the wild and the tamed (what the ancient Greeks termed nomos (order) and physis (chaos), as exemplified in Euripides’ tragic play, The Bacchae, first performed in 406 BC (Vellacott 1973, pp. 9, 30)) facing each other, with the crossing line represented not just by the sacred tree but also by the hare. This creature (according to Julius Caesar’s comments about Britannia (De Bello Gallico 5.12)) was regarded as special, protected by an embargo on hunting or eating the animal. Another British reference to hares, made by Dio Cassius in relation to Boudica’s rebellion (Roman History 62. 6), connects this animal with divine prophecy. If this pertained to Roman Gaul, it is permissible to suggest that it was itself a liminal creature, a wild but protected beast with a fast-track path to the spirit world.

The anthropomorphic figures inhabiting the upper register of the sculpture are rich in oppositional, yet fluidly connected imagery in blatant subversions of gender and species ‘norms’. The attributes with which these anthropomorphic images are associated are redolent with the themes of fertility and abundance, in celebration—perhaps—of the challenges to boundaries and the crossing of thresholds (always dangerous) that may have been regarded as essential in projections of healing and repair. Such border-referencing is carried through in the very placement of the shrine at Bolards at the nodal point between three tribes, in an ‘unordered’, fringe region, paradoxically belonging to no one but everyone, and particularly the gods. The triple-faced image on the triadic sculpture may, indeed, reflect its gaze, its role as protector of the three territories, its rotating view fixed in stone. It is worth taking a sideways glance at another provincial Roman healing sanctuary, in Britannia, far away from Bolards, at Lydney overlooking the great River Severn in Gloucestershire. Founded late in the Roman Empire, in the late third to fourth centuries.AD, Lydney was dedicated to a British healer deity, Nodens. The most prominent offerings to the god were the several small images of dogs, depicted in profile. One of them, though, is different; it shows the profile of a dog, but its head, turned full-face towards the viewer and with distinctly canine ears, displays a face that is wholly human (Figure 9) (Wheeler and Wheeler 1932, p. 89, pl. XXVI, no. 119). It is also the only one of the nine canine images from the temple that is visually gendered; a jagged row of teats suggests not only its female gender but also that she is lactating. This overt image of fertility echoes a small bone figurine, from the site, of a pregnant (or newly delivered woman), with a prominent navel and her hands clasping her abdomen (Wheeler and Wheeler 1932, p. 89, pl. XXVI, no. 122). At the risk of stretching the evidence too far, it seems to me as though these images project notions not only of fertility (closely linked with healing, as on many cognate sites) but also of the transition and change associated with pregnancy and birth.

Figure 9.

Bronze figurine of a human-faced dog, from the late Roman temple at Lydney, Gloucestershire, UK.

6. Thresholds, Subversion and the Carnivalesque: Theoretical Perspectives

My discussion of the case studies presented in this article resonates with the digressions from the ‘rules’ governing the material world as experienced in real time, as expressed in certain image forms, whether on decorative military Iron Age metalwork or on stone sculptures from Roman Gaul and Britain. What appears to have been happening is that, unlike modern outlooks on the world that see the naturalistic as normative, the archaeological material discussed in this paper persistently disrupts such ‘reality’ viewpoints. In this section, I want to explore possible paths of thinking, in terms of issues that may have been pertinent to the fluidity, surrealism and border-crossing expressed therein and perhaps associated with shamanism.

In a powerful and imaginative interpretation of some decorated Irish Neolithic passage graves—far away from the geo-chronological context of the imagery discussed here—Andrew Cochrane (2012, p. 133) examines the notion that images need not be treated simply as passive, gazed-at objects but as ‘collaborative and dynamic’, to be engaged with in an interactive manner. He speaks of the ability of such art to ‘subvert, invert and deceive the norm’ (Cochrane 2012, p. 135), and to express deep knowledge and issues that transcend the art itself but also address other spheres. These might include those associated with societal relationships, conflict, environment and religion. He goes on to examine the idea of the ‘carnivalesque’, something that happens when the themes of carnival invert, subvert or exaggerate real life. At its centre are the notions of fluidity, change and the desire to express ‘otherness’ in order to draw attention to the instability of and the need to challenge habit (Stam 1989, p. 86). Cochrane argues for the paradox of the ‘permanence of change’ (2012, 143), the celebration of the grotesque and the hidden. Subversion, in whatever form, creates connection by stimulating anxieties and shock that affect individuals but also groups, with a shared experience of the unexpected (Cochrane 2012, p. 154).

Granted that Cochrane is referring specifically to the tomb art inside Irish passage graves, is it appropriate to apply such thinking to any of the ‘subversive’ images from the Iron Age and Roman period considered in this paper? For instance, might the double heads on the Tal-y-Llyn shield plaques have been designed to unnerve, or the complicated and subversive images on the carving from Bolards to engender unrest? I am not saying that the desire to rock or shock was necessarily a primary intention, but that it is worth considering as a factor in the choice of image-making, especially in contexts that were themselves challenging, such as illness, war and death. The Gundestrup Cauldron, with its recurrent transitional, species-shifting imagery, may have been a piece of liturgical, even sacrificial regalia, associated with blood and killing. The subject matter of the circular basal plate might provide a clue to the vessel’s purpose, for it depicts a dying bull, perhaps a wild aurochs, its head once adorned with antlers that were perhaps inserted and removed according to changing seasons and/or changing rituals. However, when in place, the antlers would have stuck up from the bottom of the cauldron, perhaps rearing up from the blood or other liquid contained within it, to visualise and realise the act of sacrifice.

Acting as something akin to a ‘drone’ in bagpipe music or a subtle undertone to tropes of subversion and fluidity is the theme of the threshold, the subject of a major folklore colloquium hosted by the Katharine Briggs Club in the early 1990s (Davidson 1993b). Any threshold, whether physical or symbolic, involves concepts of both barrier and connection between ‘here’ and ‘beyond’. In many parts of the Indian sub-continent, notably in the states of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu in the south, thresholds are freighted with meaning, whether in domestic or sacred environments. In Tamil Nadu, sprawling and meandering designs, known as kolams and made with chalk powder, adorn the thresholds of houses. Drawn by women as soon as they prepare for the day’s work, these are gradually erased by foot traffic as the day wears on. ‘Thus begins the random process of erasure which is an integral part of the practice’ (Dohmen 2001, p. 9). Whilst nuanced interpretation of these designs is not easy for western academics to achieve (and the meanings associated with them are undoubtedly highly complex), there is some mileage in making links between kolams—and other Indian threshold art—and transition points, which can be perceived as ‘weak’ (Dohmen 2001, p. 14) and in need of strengthening. These might vary from ideas about protecting the home or private shrine from whatever may threaten it to the acknowledgement of calendrical changes. On a visit to Karnataka in January 2020, I was very aware of threshold rituals associated with major Hindu religious centres, such as Badami (Michell 2017, pp. 42–75); it is obligatory both to doff shoes before crossing into sacred space and to avoid treading on the decorated threshold stones themselves. (We can relate the latter to seasonal transitions in other cultures—from Hallowe’en to carnival festivals.) Hilda Ellis Davidson (1993a, p. 8) comments on the marking of such boundaries ‘sometimes by violence and mayhem, the permitted overturning of customary order during the time of transition, creating a period of confusion before normal living is restored’ (1993, p. 8).

A prime example of border-crossing from the past is the Roman festival of the Saturnalia, where, for a week in mid-winter, the world turned topsy-turvy, and slaves made merry, exchanged roles with their masters and were waited on at the dinner table. (Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.24. pp. 22–3; Beard et al. 1998a, p. 50; 1998b, p. 124). Rites of passage, too, are often associated with extreme and subversive behaviour; witness the sometimes-rowdy custom, in our own society, of stag and hen parties, including the wearing of bizarre costumes and excessive alcohol consumption, to mark and celebrate the change from single to married status. Thus, thresholds are acknowledged and breached, while a reference is always made to before and after and the connective bridge between. In a sense, shapeshifting is happening in all these examples, and running through many boundary rituals is the notion of risk. For instance, in Irish and Welsh mythology, junctions between temporal periods, such as May Eve, were perceived as perilous, perhaps because these were the times ‘of no being’, when the spirits could invade the world of the earth. In Ireland, the danger of May 1 was associated with threats to milk and butter (Lysaght 1993, p. 31). In the collection of Welsh medieval mythic tales, known as the Mabinogion, May Eve was the time when new-born babies might be spirited away from their parents, as in the story of Rhiannon, Pwyll and their infant son Pryderi (Davies 2007, pp. 16–20; Aldhouse-Green 2015b, pp. 82–83). This notion of danger feeds into the role of the shaman in many societies, past and present, someone who could assume many physical forms and, by so doing, was able to penetrate the otherworld and liaise with its spirit inhabitants. Each shamanic transition is in itself a perilous act that can result in severe injury or death to the shaman for trespassing in the spirit world.

7. Looking Both Ways: Fluidity, Subversion and Shamanism

Boundaries and thresholds look both ways (Richardson 1993, pp. 92–93) in material space, time and a host of other dimensions involving portals: towards the living and the dead; between illness and health; war and peace; the worlds of the earth and spirit; animal and human. Many are expressed or imaged in physical ways that exhibit oppositional forms possibly representing much broader issues. Such are all the images discussed in this paper, and, of course, the case studies selected are merely a tiny proportion of the whole panoply of material culture relating to the symbolic and often contrapuntal iconography of the Iron Age and Roman Britain and Europe.

Is there a case for making links between shamanism and the images considered here? To get a handle on this it is necessary first to set out some of the principles most commonly associated with shamans (past and present) and, second, to take another brief glance at the subjects of the case studies presented in order to test the viability of proposed connections. There is a multiplicity of literature on shamans and shamanism, but I always return to what for me is the most cogent and concise exploration set out by Piers Vitebsky (1995). Shamans are essentially ‘go-betweens’, their power residing in their ability to penetrate the boundaries between the earth and spirit worlds, for the purposes of divining the will of the spirits, liaising with them for the benefit (including healing) of people in their communities and maintaining fluid connections between the layers of the cosmos. Fluidity and elision are key elements to both the being and the expression of shamans. The capacity to segue between the porous borders (for them) may be displayed by gender-crossing, subverting species boundaries, transference from material to spirit realms and other forms of transgression, including time, and triplistic expression, which, in some cultures, taps into the notion of the three layers in cosmic geography (Vitebsky 1995, pp. 15–17). All of this ‘grammar’, perhaps interwoven with cosmic geographies and beliefs, occurs in one or another of the images referenced in this paper. I would not go so far as to identify any of the objects studied here as ‘shamanic equipment’ (Price 2001, p. 8), but it is—I think—permissible to allow thoughts about a possible shamanic background to the symbolism encountered therein. Might the triple-faced image at Bolards even reflect a shamanistic association between the three layers of the cosmos (upper, middle and underworld), such a central tenet in the near past and present of so many shamanic communities in the north?

If we are to acknowledge that shamanism might be associated with later prehistoric and provincial Roman cult expression, it is necessary to look at other elements in cognate material culture to see whether they offer support for this thesis. In ‘modern’ interpretations of shamanism, it is trance or ‘altered states of consciousness’ that provide portals for transgression and for entry into the spirit world (Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1990; Lewis-Williams 1997; Dronfield 1996). Vectors for the achievement of trance state—or out-of-body experience—vary across shamanistic cultures, but include altered breathing rhythms, dancing, drumming, chanting, overheating (for example, in First Nation American sweat lodges) and sensory deprivation (none of which leave firm archaeological footprints). However, other mechanisms for entering trance states can leave traces, particularly where psychotropic substances are involved. There is also some tangible evidence that hallucinogens were used in later prehistoric and Roman period Britain and Europe. Andrew Sherratt (1991, p. 52) alluded to the “abundant finds” of cannabis from the rich wagon burial of a chieftain at Hochdorf in Germany in the sixth century BC. Incense burners from a Gallo-Roman underground sanctuary at Chartres were clearly used in esoteric rituals; they are inscribed with obscure god names, summoned up by someone called Gaius Verius Sedatus, who claimed himself the guardian of the spirits (Joly 2012). The ‘Doctor’s Grave’ at Stanway, Camulodunum, dating to around the time of the Roman invasion of Britannia in the mid-first century AD, was that of a high-ranking individual of the East Anglian tribe of the Trinovantes. The objects placed in the tomb included medical equipment, sets of what might have been rods, perhaps used in divination, and a copper alloy bowl whose spout contained residues of Artemisia, a known psychotropic plant (Crummy et al. 2007, pp. 201–53). These are just three of many pieces of evidence suggesting the use of substances perhaps used by people who, in other societies, would be identified as shamans.

8. Conclusions

This paper has sought to offer a shamanic context to certain forms of symbolic image presentation. All the case studies considered here exhibit elements associated with liminality and the subversive manipulation of ‘norms’. Species and gender crossing, together with the expression of restless movement between states of being, all fit into a broadly shamanistic model, where change, fluidity and connections form a network of oscillations between realms of existence: between life and death; stasis and movement; illness and health; war and peace; and—ultimately—between the domains of material humanity and the spirits.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J. 2001a. Cosmovision and Metaphor: Monsters and Shamans in Gallo-British Cult-Expression. European Journal of Archaeology 4: 203–32. [Google Scholar]

- Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J. 2001b. Animal Iconographies: Metaphor, Meaning and Identity (or Why Chinese Dragons Don’t Have Wings). In TRAC 2000 (Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Theoretical Archaeology Conference London 2000), London, UK, 6–7 April 2000. Edited by Davies Gwyn, Gardner Andrew and Lockyear Kris. London: Institute of Archaeology, University College London, pp. 80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J. 2004. An Archaeology of Images. Iconology and Cosmology in Iron Age and Roman Europe. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J. 2006. Metaphors, meaning and money: Contextualising some symbols on Iron Age coins. In Celtic Coinage: New Discoveries, New Discussion. International Series no. 1532; Edited by P. de Jersey. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J. 2010. Caesar’s Druids. Story of an Ancient Priesthood. Newhaven & London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J. 2015a. Bog Bodies Uncovered. Solving Europe’s Ancient Mystery. London: Thames and Hudson, pp. 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J. 2015b. The Celtic Myths. A Guide to the Ancient Gods and Legends. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J. 2021. Rethinking the Ancient Druids: An Archaeological Perspective. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J., and Stephen H.R. Aldhouse-Green. 2005. The Quest for the Shaman. Shape-Shifters, Sorcerers and Spirit-Healers of Ancient Europe. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Armit, Ian. 2009. Janus in furs? Opposed human heads in the art of the European Iron Age. In Relics of Old Decency: Archaeological Studies in Later Prehistory (Festschrift in honour of Barry Raftery). Edited by Gabriel Cooney, Katharina Becker, John Coles, Michael Ryan and Susanne Sievers. Dublin: Wordwell, pp. 279–86. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. 2019. Pembrokshire Treasure Hunter Unearths Celtic Chariot. Available online: https://www.bbc.c.uk/news/uk-wales-46294000 (accessed on 9 July 2019).

- Beard, Mary, John North, and Simon Price. 1998a. Religions of Rome. Volume 1. A History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, Mary, John North, and Simon Price. 1998b. Religions of Rome. Volume 2. A Sourcebook. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, George C. 1982. A coin with the head of the Cernunnos. Seaby Coin and Medal Bulletin 769: 276–82. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, Thomas J., Andrew T. Chamberlain, and Mike Parker Pearson. 2015. Mummification in Bronze Age Britain. Antiquity 89: 1155–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, S. 1976. Recherches Sure les bronzes Figures de Gaule pré-Romaine et Romaine. Paris and Rome: Bibliothèque des Écoles Françaises d’Athènes et de Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Richard. 2000. An Archaeology of Natural Places. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, M. 2020. Play the thigh note: Ancient whistle made from human leg bone. The Times, September 1, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Brunaux, Jean-Louis. 1986. Les Gaulois. Sanctuaires et Rites. Paris: Errance. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, A. 2012. The Immanency of the Intangible Image. In Encountering Imagery. Materialities, Perceptions, Relations. Stockholm Studies in Archaeology No 57. Edited by Ing-Marie Back Danielsson, Fredrik Fahlander and Ylva Sjöstrand. Stockholm: Stockholm University, pp. 133–60. [Google Scholar]

- Collingwood, R. G., and R. P. Wright. 1976. The Roman Inscriptions of Britain. Volume I Inscriptions on Stone. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton, John. 1995. Visions of Power: Imagery and symbols in late Iron Age Britain. Britannia 26: 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crummy, P., S. Benfield, N. Crummy, V. Rigby, and D. Shimmin. 2007. Stanway. An Élite Burial Site at Camulodunum. Britannia Monograph Series No. 24; London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, H. E. 1993a. Introduction. In Boundaries and Thresholds. Edited by H. E. Davidson. Woodchester and Stroud: Thimble Press, pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, H. E., ed. 1993b. Boundaries and Thresholds (Papers from a Colloquium of the Katharine Briggs Club). Woodchester and Stroud: Thimble Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S. 2007. The Mabinogion. The Great Medieval Celtic Tales. A New Translation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Mary, and Adam Gwilt. 2008. Material, style and identity in first century AD metalwork, with particular reference to the Seven Sisters Hoard. In Rethinking Celtic Art. Edited by Duncan Garrow, C. Gosden and J. D. Hill. Oxford: Oxbo w, pp. 146–84. [Google Scholar]

- Deyts, S. 2001. La sculpture et les inscriptions. In Le Sanctuaire Antique à Nuits-Sant-Georges (Côte d’Or). Edited by Colette Pommeret. Dijon: Revue Archéologique de l’est. Seizième Supplément and Ministère de la Culture, Imprimerie Nationale, pp. 129–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dohmen, Renate. 2001. Liminal in more ways than one: Threshold designs in contemporary Tamil Nadu. In A Permeability of Boundaries: New Approaches to the Archaeology of Art, Religion and Folklore. British Archaeological Reports International Series No. 936; Edited by Robert Wallis and Kenneth Lyme. Oxford: Tempus Reparatsm, pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dronfield, Jeremy. 1996. Entering Alternative realities: Cognition, art and architecture in Irish passage-tombs. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 6: 37–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, P.-M. 1987. Monnaies Gauloises et Mythes Celtiques. Paris: Hermann, Editeurs des Sciences et des Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Melanie. 2012. A Forged Glamour: Landscape, Identity and Material Culture in the Iron Age. Oxford: Oxbow/Windjammer Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Melanie. 2020. Bog Bodies. Face to Face with the Past. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henig, Martin. 1993. Roman Sculpture from the Cotswold Region. Corpis Signorum Imperii Romani. Corpus of Sculpture of the Roman World. Great Britain, Volume I, Fascicule 7. London and Oxford: The British Academy/Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hole, K. 2020. Wildflame Television Productions, Cardiff, Wales. Personal communication. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, Fraser, D. Martin Goldberg, Julia Farley, and Ian Leins. 2015. Celtic Arts in the Long Term: Continuity, Change and Connections. In Celts, Art and Identity. London and Edinburgh: The Trustees of the British Museum/National Museums Scotland, pp. 261–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 1986. The Appropriation of Nature. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, G. C., ed. 1962. Paradise Lost. Books I and II. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Sue-Ellen, Wesley Thomas, and Sabine Lang, eds. 1997. Two Spirit People: Native American Gender, Sexuality and Spirituality. Campaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joly, D. 2012. La panoplie complete d’un magician dans la cave d’une domus à Autricum (Chartres-France): C. Verius Sedatus, Carnute, gardien des divinités. In Contesti Magici. Edited by M. Piramonte and F. Marco Simó. Rome: Ministero per I Beni Attività Culturali, pp. 211–23. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, Jody. 2015. Approaching Celtic Art. In Celts, Art and Identity. Edited by J. Farley and F. Hunter. London and Edinburgh: The Trustees of the British Museum/National Museums Scotland, pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kaul, Flemming. 1991. Gundestrupkedlen. Copenhagen: Nationalmuseet/Nyt Nordisk Arnold Busck. [Google Scholar]

- King, Anthony. 1990. Roman Gaul and Germany. London: British Museum Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Knüsel, Christopher. 2002. More Circe than Cassandra: The princess of Vix in ritualized social context. European Journal of Archaeology 5: 275–309. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts, Pieter. 1942. Contributions à l’Étude des Divinites Celtiques. Brugge and Bruges: Rijksuniversiteit te Gent. Werken Uitgegeven Door de Faculteit van de Wijsbegeerte en Letteren. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David. 1997. Harnessing the brain: Vision and shamanism in palaeolithic western Europe. In Beyond Art: Pleistocene Image and Symbol. Edited by M. W. Conkey, O. Soffer, D. Stratmann and N. G. Jablonski. San Francisco: Memoirs of the Californian Academy of Sciences, vol. 23, pp. 321–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David, and T. A. Dowson. 1990. On Palaeolithic art and the neuropsychological model. Current Anthropology 31: 407–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysaght, Patricia. 1993. Bealtaine: Irish Maytime Customs and the Reaffirmation of Boundaries. In Boundaries and Thresholds (Papers from a Colloquium of the Katharine Briggs Club). Edited by H. E. Davidson. Woodchester and Stroud: Thimble Press, pp. 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, P. 2007. Llyn Cerrig Bach. A Study of the Copper-Alloy Artefacts from the Insular la Tène Assemblage. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly, H. 1948. Tacitus on Britain and Germany. Harmondsworth: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly, David. 2006. An Imperial Possession. Britain in the Roman Empire. London: Penguin/Allen Lane. [Google Scholar]

- Megaw, John Vincent Stanley. 1970. Art of the European Iron Age. A Study of the Elusive Image. London: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Megaw, R., and V. Megaw. 1989. Celtic Art. From its Beginnings to the Book of Kells. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Michell, G. 2017. Badami, Aihole, Pattadakal. Mumbai: Jaico Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Miron, D. A. 1986. La tombe princière de Reinheim. in Association Abbaye de Daoulas. In Au Temps des Celtes. V-Ier Siècle Avant J.-C. Quimper: Association de Daoulas Musée Départemental Breton de Quimper, pp. 110–111. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier, Laurent. 2014. Les codes de representation visuelle dans l’Art celtique ancien. In Celtic Art in Europe. Making Connections. Edited by C. Gosden, S. Crawford and K. Ulmschneider. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted, Garrett S. 1979. The Gundestrup Cauldron. Its Archaeological Context, the Style and Iconography of its Portrayed Motifs and Their Narration of a Gaulish Version of Táin Bó Cúailnge. Brussels: Latomus Revue d’Etudes Latines, vol. 162. [Google Scholar]

- Parker Pearson, Mike, Andrew Chamberlain, Oliver Craig, Peter Marshall, Jacqui Mulville, Helen Smith, Carolyn Chenery, Matthew Collins, Gordon Cook, Geoffrey Craig, and et al. 2005. Evidence for Mummification in Bronze Age Britain. Antiquity 79: 529–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pentikäinen, J. 1998. Shamanism and Culture. Helsinki: Etnika Co. [Google Scholar]

- Planson, E., and C. Pommeret. 1986. Les Bolards. Paris: Ministère de la Culture. [Google Scholar]

- Pommeret, Colette. 2001. Le Sanctuaire Antique des Bolards à Nuits-Saint-Georges (Côte d’Or). Dijon: Revue Archéologique de l’Est, Seizième Supplément. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Neil S. 2001. An archaeology of altered states: Shamanism and material culture studies. In An Archaeology of Shamanism. Edited by Neil S. Price. London: Routledge, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, Ruth. 1993. Death’s Door: Thresholds and Boundaries in British Funeral Customs. In Boundaries and Thresholds (Papers from a Colloquium of the Katharine Briggs Club. Edited by H. E. Davidson. Woodchester, Stroud: Thimble Press, pp. 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Savory, Hubert Newman. 1976. Guide Catalogue of the Early Iron Age Collections. Cardiff: National Museum of Wales. [Google Scholar]

- Séfériadès, M. L. 2018. Shamans’ Landscapes: Note sur la psychologie du shaman pre et protohistorique plus particulierement en Eurasie. In Lands of the Shamans. Archaeology, Cosmology and Landscape. Edited by Dragos Gheorghiu, G. Nash, H. Bender and Pásztor. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Sherratt, Andrew. 1991. Sacred and Profane Substances: The Ritual Use of Narcotics in Later Neolithic Europe. In Sacred and Profane. Proceedings of a Conference on Archaeology, Ritual and Religion Oxford 1989. Monograph No. 32. Edited by P. Garwood, D. Jennings, R. Skeates and J. Toms. Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology, pp. 50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, Robert. 1989. Subversive Pleasures: Bakhtin, Cultural Criticism and Film. London: The John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vellacott, P., trans. 1973. The Bacchae and other Plays. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Vitebsky, Piers. 1995. The Shaman. Voyages of the Soul, Trance, Ecstasy and Healing. From Siberia to the Amazon. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, R. E. M., and T. V. Wheeler. 1932. Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Goucestershire. Oxford: Printed at Oxford University Press for The Society of Antiquaries, Burlington House, London. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).