Many indigenous groups throughout the world hold that spirits affect and structure reality (

Vitebsky 2001). This view typically takes the form of animism, an ontology that holds that spirit essences animate the universe, structure the world of the here-and-now, and are present in nature (e.g., the wind and thunder), in living plants and animals, and in many nonorganic objects (e.g., certain mountains, stones, and ponds). Some groups throughout Mesoamerica and North America believed spirits have weight and are material (

Carr 2020;

Carrasco 1999, p. 14;

Jones [1906] 1968). This entails that the spirit and physical worlds are not inherently separate, as they are typically considered in Western (Cartesian) perspectives. Given that spirits also have their own volition and agency, they can consequently impact the physical world. Spirits are therefore considered to be “other-than-human beings” that have a physical presence and agency that exists separate from humans, but they can interact with humans in cooperative or antagonistic ways (

Hallowell 1960; see also

Eliade 1964;

Vitebsky 2001, pp. 12–13). Interacting with these animated beings is a substantial focus of many cultural systems, given that there is often no distinction between the factors that affect daily life and the other-than-human beings that infuse the world (

Bird-David 2018;

Carr 2020;

Hallowell 1960;

Harvey 2005;

Stuckey 2010). For example, the treatment of illness in many cultures focuses on the underlying spiritual causes. Weather phenomena such as rain are brought by, and are indeed synonymous with, certain types of other-than-human beings. The migration of animals and the success of crops growing in the field is a result of the action of spirits (

Vitebsky 2001, p. 106), and so on. Completing any task or asking for any blessing is fundamentally based on social/reciprocal relationships between humans and other-than-human persons (

Eller 2007;

Halifax 1979, pp. 5–6,

1982;

Wallis 2013, p. 315). Thus, in these societies, there is no clear distinction between the physical and spiritual worlds, and most activities are reflective of social relationships among humans and non-human agents. In the North American Southwest, these spiritual relationships are so central and so pervasive that researchers such as

Fowles (

2013) contend the word

religion has no real analytic meaning in Puebloan culture. Efforts to negotiate with these spiritual relationships permeates daily activity—

religion, such as it is, is simply living the Puebloan way of life. This is true as well for many other Native American groups (

Lee 1952). Here, we explore the active role of art as a form of animism by using a cognitive archaeological approach. We demonstrate that art directly represents and links the physical and metaphysical/spiritual words, and thus acts as a direct conduit between worlds. It is therefore central to the creation and negotiation of the animated world of the Medio Period Casas Grandes people of the North American Southwest.

1. Cognitive Archaeology and the Casas Grandes Medio Period

Cognitive archaeology’s core goal is to use the archaeological record in combination with psychological and ethnographic models to understand past conceptual structures (

Renfrew 1994;

Whitley 2020). Culture provides people with a means of categorizing, organizing, and understanding their world, including its spiritual components. The conceptual structures are embedded in a culture’s cosmology (a metaphysical view that defines the nature and natural order of the universe) and ontology (view of the nature and structure of being), in that these create but are also challenged and/or are reinforced by the cultural framework. There are many ways that cultures can organize their world, but there are repeated ontological frameworks reflected across culture and through time. Human minds and human bodies lead to cultural similarities even as they produce cultural differences. One of the most common reoccurring patterns is animism, which is reflected cross-culturally in various ways. Even in Western society, animism is common as children often conceive of their toys as alive and as certain religions view otherwise inanimate objects as empowered with special spiritual potency (e.g., Catholic relics and many religious pilgrimage sites) (

Harvey 2013, p. 5). Yet, this kind of spiritual potency is especially common in hunting and gathering cultures and even among more politically complex cultures across the New World (

Bonvillain 2001, pp. 4–5;

Carr 2020;

Evans 2004, p. 34;

Friedel et al. 1993) (see also

Newman 2018, who talks about more implicit forms of animism in current American society). So prevalent is animism worldwide that Marvin

Harris (

1989, p. 399) suggests that it is “the basis of

all religious thought” (see also

Moro et al. 2008, p. 16; our emphasis).

The North American Southwest is one area where animism is common (

Brown and Walker 2008;

Conti and Walker 2015;

Mills and Ferguson 2008). This includes the Medio Period Casas Grandes occupation (AD 1200 to 1450) (

VanPool and Newsome 2012;

VanPool and VanPool 2016;

Walker and McGahee 2006). The Casas Grandes culture spread across northern Mexico (especially the northernmost portion of Chihuahua) and the southwestern United States (especially the southern edge of New Mexico). The Medio Period system was centered on Paquimé, a large settlement on the west bank of the Rio Casas Grandes (

Di Peso 1974;

Figure 1). Paquimé reflects a higher level of political complexity than is typical of surrounding communities (

Cunningham 2017;

Douglas and MacWilliams 2015;

Rakita 2009) and was a religious and political center that dominated a 100,000 square kilometer region (

Whalen and Pitezel 2015, p. 121). As the economic and ritual heart of the Medio Period system, Paquimé included a large apartment-like room block filled with habitation and ritual rooms, platform mounds where public ceremonies were completed, a reservoir system that brought running water through the community, two I-shaped ballcourts and a T-shaped ballcourt, and large agave roasting ovens (

Di Peso 1974). The architecture is atypical for most Southwestern groups in terms of its size and embellishment (

Figure 2). It is massively ‘overbuilt’ with adobe walls often over 50 cm thick and is ornately constructed (

Bagwell 2006;

Di Peso 1974;

Whalen and Minnis 2001). When the Spanish first visited the site in the 1500s, they likened its beauty to a Roman city, filled with colorful paved alleyways and beautifully painted mosaics on walls rising three or more stories tall (

Gamboa 2002, p. 41). The elites who lived there set themselves at the apex of one of the most politically complex New World cultural systems north of Mesoamerica (

Cunningham 2017).

We have suggested elsewhere that the underlying theme reflected in Paquimé’s architecture, pottery, and general material culture was the concept of shamanic transformation associated with the ruling elites (

VanPool 2003a;

VanPool and VanPool 2007). We based this argument on a curious design, the pound sign, that was primarily found on male effigies, painted figures with headdresses, and painted anthropomorphs. The male effigies were sometimes shown smoking cylinder pipes while kneeling on one knee or were simply shown kneeling. These male effigies depicted men wearing sashes and distinctive ceremonial sandals that were indicative of high-status clothing (

VanPool et al. 2017). The pound sign was also depicted on painted images of males wearing horned-plumed serpent headdresses, individuals with horns growing out of their heads, and anthropomorphic individuals with macaw heads who were shown interacting with supernatural creatures, including horned-plumed serpents (

Figure 4;

VanPool and VanPool 2007). These images reflected shamans starting their shamanic journey by smoking sacred (hallucinogenic) tobacco, dancing, and then becoming macaw-headed beings who flew to the spirit world to interact directly with spirits while in altered states of consciousness (

VanPool and VanPool 2007). They would then return to the mundane world of the here-and-now as they regained consciousness (

VanPool 2003a; see also

Wilbert 1987). Each stage of this transformation was reflected in the shamanic art depicted on the Casas Grandes polychromes (

Figure 4). No single vessel reflected the entire shamanic transformation and spirit journey. It was the pound sign that connected the male smoker effigies, the painted individuals in headdress, and the macaw-head anthropomorphs into a related class of shamanic vessels and imagery.

The Medio Period shamanic practice built on previous traditions found throughout West Mexico, northern Mexico, western Texas, and the preceding Mimbres Mogollon tradition (AD 1000 to 1115). These include shamanic traditions based on peyote, datura, tobacco, and other entheogens (

Berlant et al. 2017;

Boyd 1996;

Huckell and VanPool 2006;

Robinson et al. 2020). The type of shamanism practiced during the Medio Period may have spread into other areas of the Southwest.

VanPool (

2009) suggests that datura and tobacco, which produce different visual and neurological perceptions, were used in rituals at Pottery Mound based on kiva murals, recovered datura seeds, and pipes. Ethnographers debate the degree to which Southwestern people practiced shamanism, but it is generally agreed that a shamanic world view is present throughout the Southwest (

Ellis 1979, p. 444;

Hays-Gilpin and LeBlanc 2007, p. 127;

Lamphere 1983). In fact,

Lamphere (

1983, p. 755) states, “Pueblo religion seems to be based on an essentially shamanic worldview adapted to the needs of an agricultural people.” This includes the animistic perspective we discuss here.

2. Animism and Non-Human Agents

For animists, “humans” and “objects” are potentially equally “things” and “persons”—things-as-persons and persons-as-things—with diverse agentive qualities, situated within wider-than-human communities.

Related to the use of spiritual power within an animistic framework are concepts such as the “soul,” “personhood,” and “spirit.” A. Irving Hallowell was one of the first anthropologists to realize this. In his initial exploration of “Bear Ceremonialism,”

Hallowell (

1926) clearly showed that Cartesian ontology, which distinguishes between the spiritual and physical worlds and is the intellectual basis of modern Western science, was useless for understanding the Ojibwa (

Harvey 2005). The Ojibwa and many other Native American cultures did not adhere to the Cartesian divide (

Harvey 2005;

Morrison 2015;

Stuckey 2010;

VanPool and Newsome 2012). To the contrary, the world could only be understood within these frameworks as the union of spirit and matter—spirits have physical components and physical matter can be inalienably imbued with spirit. Underlying this union was spiritual power, either conceived of as an impersonal force that helped structure reality or, more common in New World native groups, as distinct, conscious entities that animated the world. Ojibwa and other Native North America ontologies generally focused on interacting with these forces.

Hallowell (

1960, p. 43) found that the Ojibwa conceived of the spirit agents as “persons,” with their own agency and volition. Humans were “persons” but there were other-than-human persons too. The other-than-human persons had emotional states and volition like humans, which allowed humans to interact with and negotiate with them.

Thus, for the Ojibwa and many other Native American groups, there is a world full of persons that have human qualities such as an internal vital essence, self-awareness, personal identity, autonomy, and volition, although it is equally important to note that not everything has a personhood (

Carr 2020;

Hallowell 1960;

Stuckey 2010). Some stones, plants, or walls are just stones, plants, or walls. This makes it even more important to recognize those objects that have personhood and treat them accordingly. Again, Southwestern Native American cultures reflect this general pattern. Entities such as the kachina animate and permeate the Puebloan worldview (

Parsons [1939] 1996) and have both a physical and spiritual presence that is tied to but not constrained by the kachina masks that masked dancers wear during ceremonies. The kachina themselves live in their own village as other-than-human persons and with their own social ties among each other and other spirit beings. The kachinas will leave their village for part of the year to inhabit the masks (

Bunzel 1992). The masks in part gain their volition and power from the fact that they accurately depict the kachina they represent. This complex relationship among humans, ceremonially created objects that are human-made other-than-human persons, and the underlying spirits is not unusual. Sometimes, the objects can actually become part of the spirit entity. For example, a stone in the plaza of Tsi’ya (Zia Pueblo) is animated with

Gacítiwa (Whiteman), an other-than-human person who is given offerings of ground maize and can grant supernatural power to virtuous people (

White 1962, p. 114). Rituals are used among the Pueblos and Navajo to animate houses.

Webster (

2010) notes that Navajo consider their

hooghan (a.k.a. hogan, which are semisubterranean structures traditionally used as houses and meeting places) as other-than-human persons who are created using the Blessingway ceremony, with the active participation of supernatural entities called to the event in part though sand paintings. The

hooghan mediate the social relationships among humans, directly reflect the structure of the Navajo universe (which is conceived of as a giant

hooghan), and share “blessings and a reciprocal relationship with the Diné [Navajo] who share his/her space” (

Webster 2010, p. 9). As such, the

hooghan “have rational faculties, will, voice, desires, and needs held in common with human persons” (

Webster 2010, p. 126).

We suggest that a Western scientific view that looks at hooghans as structures and kachina masks simply as ritual paraphernalia misses the important social and conceptual roles they play in creating and maintaining social relationships in Native culture. They are not objects but are instead people. From such an animistic perspective, the important issue is who they are as persons. This is remarkably different than the scientific perspective that tends to focus on functional/systemic classification related to what something is.

3. Shamans, Spirits, and Art

A Siberian shaman’s costume “represents the mysteries experienced by the shaman, and is the dwelling place of the spirits”.

Although everyone within animistic societies interacts with other-than-human persons, some individuals are specifically tasked with mediating human interaction with the potent spirits animating the world around them. The spirits themselves may select who they wish to serve in this role, often over the objections of the chosen humans (

Black 1973, p. 55;

Eliade 1964;

Vitebsky 2001). New World ethnographies are replete with examples of shamans, mediums, and other ritual specialists that actively resist the call to become a ritual specialist after a dream or other event made it clear they were selected (

Eliade 1964). These individuals frequently acquiesce to become shamans only after a prolonged illness forces them to obey the spirits’ call (

Eliade 1964;

Halifax 1979,

1982;

Vitebsky 2001, p. 57;

Whitley 2009). For example, shaman initiates among the Yuki of northern California reportedly are called by being directly confronted by

Taikomol (their chief deity) or another deity, which often causes the chosen person to bleed from “his body openings” (

Miller 1979, p. 24). Often, the only way to relieve themselves of the pain and physical ailments was to acknowledge the spirits and let them guide the afflicted through the transformation process to become a shaman (

Eliade 1964;

Kasten 1955, p. 64;

Vitebsky 2001). Incipient shamans among the Huichol of Western Mexico likewise are selected for their future profession by ‘Urukáme, a benevolent deity that helps with hunting, curing, fertility, and other beneficial aspects of human efforts (

Furst 1967, p. 101). When ‘Urukáme selects a man, he will become ill until cured by another shaman. The illness is easy to cure but can only be cured by a shaman recognizing the illness for what it is and performing the correct ritual to begin the process of transitioning the ill person into a shaman. The healing requires the new shaman to “journey to the Other world” (

Furst 1967, p. 101; see also

Eliade 1964;

Halifax 1979, p. 12). Quoting personal communication from Johannes Wilbert,

Furst (

1967, p. 102) suggests that the illness caused by ‘Urukáme is not a malicious act but is better understood as the recipient having not yet “transcended his physical limitations, i.e., [he] has not achieved that breakthrough in plane which is essential to shamanism and which manifests itself in the classic shamanic phenomena of initiatory ecstasy, sickness, death and rebirth.” In other words, ‘Urukáme has provided the incipient shaman with spiritual power his body and soul are not yet able to contain. Only through his own transformation into a shaman can the afflicted person gain the capability of dealing with the gifted spiritual power he cannot discard. Refusing to accept the spirits’ invitation can lead to death (

Kroeber 1970, p. 245;

Vitebsky 2001, p. 57).

While shamans hold a special place in animistic frameworks, other people are also impacted by and influence spirits and spiritual power. Here, we suggest that artists and craftsmen (who may or may not be shamans themselves) also serve a significant role. Within animistic systems, art transcends the physical presentation and contains active spiritual power (see also

Vitebsky 2001;

Zedeño 2009). Put more directly, the art can be and often is either its own other-than-human being or is a significant part of an other-than-human being that helps determine the entity’s characteristics. As such, it is a means of both invoking certain spiritual properties and negotiating with independently existing non-human agents. Our focus thus is on the active role artists play in regulating and fostering beneficial spiritual interactions among their people and the non-human agents that animate their world. Often, artists use their art in tandem with other practices. For example, shamans are frequently also significant artists in their societies. It is the spirits who guide shamans while they create their songs, poems, and images that are portrayed in various mediums, including paintings on wood and hides, carved wooden and stone effigies and palettes, sand paintings, and pecked or painted rock art. Much of the art itself acts as the conduit of literal interaction between humans and spirits (

Vitebsky 2001).

The intricate designs painted on the shaman’s drum often help him/her traverse the cosmos by providing a map, for example (

Halifax 1982;

Potapov 1999;

Vitebsky 2001, p. 82). Often, the designs on the shamans’ regalia and equipment are thought to be the spirits themselves (

Potapov 1999;

Vitebsky 2001, p. 83). These examples of art do not just symbolize the spirit world, but instead serve as active, spiritually potent participants in ritual, exercising their own volition that helps people transcend the world of the here-and-now. The drum as a map represents the reality of the realms that shamans travel through during ACS (

Potapov 1999;

Vitebsky 2001). The art’s very existence demonstrates the reality of these typically unseen worlds, just as a photograph of Niagara Falls reflects its reality to someone who has never visited them. As

Halifax (

1982, p. 11) paradoxically notes, then, “shamanic art is not art.” These items and images make the unknown knowable by materializing the metaphysical world. They also enable the shaman to have some control over the powerful forces of the

mysterium (

Halifax 1982, p. 11). Shamanic “art” itself thus has animistic powers, a view that exceeds the typical perspectives of Western, Cartesian ontology (see also

Roe 2004;

Wallis 2013). While Western scholars readily accept that art presents religious themes that describe aspects of the spirit world (e.g., the Sistine Chapel’s famous depiction of Adam and God reaching out to each other), art within New World societies is often an active, literal component of the spirit world. In fact, it can sometimes be understood (both in terms of its presence and its significance) based on its functional linkage to other aspects of reality (including spirits) (

Roe 2004, p. 101).

Our use of “art” also fits the processual relativist approach outlined by

Svašek (

2007), who suggests that it is more useful to define “when is art” instead of “what is art.” Art is discursive frameworks in which conceptual structures (in our case, a formalized religious and symbolic structure) and social structures (in our case, shamanic specialists) interact to give the art a social relevance. Such “expressive culture” facilitates and indeed requires discursive interactions, as the art prompts responses from those involved in its production and use. The production and use of art may not even be considered distinct steps, as illustrated by

Roe’s (

2004, p. 101) discussion of “doneness,” and the idea among many Native American groups that “art” is never completed. In our case study, discourse occurs at different scales: the shaman and the artist (who might be the same individual filling linked roles), the shaman and the object (as living beings), the object and the spirits (as distinct or possibly linked beings), and the shaman and the spirits (with their discourse facilitated by the object). This is an operational view of art, that defines it based on what it does, as opposed to what it is, but this approach also fits the creation of Navajo sand paintings used to gather and focus spiritual energy for healing, a shell trumpet used to summon the kachinas to human villages, spoken words and songs that are considered alive in-and-of-themselves, and other animated “art” found throughout the New World.

Shamanic “art” (and indeed shamanism itself) is inherently linked to animism. As such, shamans must

realistically portray the embodiment of spiritual principles and creatures. In other words, the art must accurately portray the underlying reality of the world, including the parts that are typically hidden (e.g., the physical reality of the Under World). A drum with incorrectly drawn designs will lead the shaman astray, potentially causing his spirit to endlessly wander the world looking for his way back to his people. Likewise, a poorly drawn sand painting will not attract the Holy Wind or will fail to place the spirits in the right framework to cooperate with humans (

Laughlin 2004). While Bear (a powerful spirit) can help Puebloan and other Native American healers cure illnesses, he can also cause human death (

Hallowell 1926;

Parsons [1939] 1996;

Vitebsky 2001). Bear and similar other-than-human persons must be approached carefully and with the proper respect, using the appropriate prayers, icons, and talismans. Failure to do so can be catastrophic for the individual and even a village. Art as volition is central to this effort. As a result, a significant part of shamanic ritual focuses on ensuring that the art properly reflects the other-than-human persons involved and to ensure they are approached in a manner that encourages their benevolence (

Goodman 1988,

1990;

Laughlin 2004).

In keeping with the general structure of animism, the ethnographic and archaeological records indicate that much of Southwestern art is focused on religious themes and establishing relationships with other-than-human beings. It might be created by either shamans/priests or under the direction of these religious specialists in order to facilitate human interaction with them. Take, for example, the Southwestern horned-plumed serpent, which is a powerful deity that can be benevolent or vengeful, depending on the context. The horned-plumed serpent (sometimes perceived as an individual and other times perceived as a race of creatures) spans and negotiates the Upper, Middle (terrestrial), and Lower Worlds. He can herd clouds in the air or move across the land to create arroyos, but most of the time he is an underground creature that can cause earthquakes and control underground water (which comes out as springs and ponds). When benevolent, he can provide gentle rains, snow, and allow springs and rivers to flow (

Dutton 1963, p. 49;

Parsons [1939] 1996;

Schaafsma 1980, p. 238). He is also associated with maize and natural fertility (

Taube 2000). He has prescribed rituals and sacred items that are used to communicate with him and to represent him in significant ceremonies. Some of these include a six-foot-long effigy used in Zuni ceremonies and shell trumpets that Puebloan priests blow to represent his voice (

Mills and Ferguson 2008, pp. 341–42;

Parsons [1939] 1996).

The horned-plumed serpent is also represented as painted images on pottery, pecked images on rock art, and in conjunction with Puebloan kachinas (

Frank and Harlow 1990: see inside of the bowl of Figure 57;

Schaafsma 1980). He is associated with clouds and frogs when depicted on historic pottery (

Frank and Harlow 1990, pp. 56, 66, 72;

Stevenson 1904: Plate XXXVI). The utility of these images is defined by how well they correspond to the underlying (culturally specific) reality of the spirit world. Further, the objects themselves are often other-than-human entities that are animated and work to negotiate among humans, the horned-plumed serpent, and other agents (e.g., the shell trumpets that call and impersonate the voice of the horned-plumed serpent are animated other-than-human beings (

Mills and Ferguson 2008). As

Mills and Ferguson (

2008, p. 343) observe, horned-plumed serpent effigies at Hopi and Zuni “are animated in these performances” and “are the beings they represent, not simply images of them, because their spiritual essence gives life to their physical form.”

Likewise, the prayer sticks of the Pueblos are created by combining specific elements, each with their own meaning based on color and material, into combinations that create a more elaborate spiritual message. Just as words can be used to create sentences, the various feathers, paints, clays, beads, and so forth used to make a prayer stick can be placed in specific combinations to carry the appropriate message/information (

Bunzel 1992;

Parsons [1939] 1996). The artisan is thus creating a new other-than-human person as they create a prayer stick, which helps the artisan interact with (previously existing) beings. This framework is made explicit in the following prayer recorded by

Bunzel (

1992, p. 485) that was said by Puebloan artisans as they made their prayer sticks:

We made our plume wands into living beings.

With the flesh of our mother,

Clay Woman,

Four times clothing our plume wands with flesh,

We made them into living beings.

Holding them fast,

We made them our representatives in prayer.

Animistic sensibility like that mentioned above is equally applicable to shamanic crafts. In the case of shamans, the creation of art can serve at least two purposes: it is a means by which they create spirit helpers imbued with the necessary characteristics, and it can record aspects of the spirit world, thereby making the intangible visible. This process parallels the process whereby the spirits reform and reconstruct the incipient shaman to be their own spirit helpers through shamanic illness and the subsequent transformation.

4. The Spirit in Casas Grandes Art

“Spiritual beings are held to affect or control the events of the material world, and man’s life here and hereafter…”

Southwestern art acts as a fulcrum for interacting with other-than-human beings. Shrines and religious structures like kivas can act as staging grounds where spiritual power and influence can be gathered and used. As illustrated above, artisans make new animated beings in the form of a shell trumpet, a kachina mask, a pottery effigy, a prayer stick, a shamanic drum, or innumerable other artifacts or features. When shamans are involved, it creates a circular, reciprocal relationship in that the spirits transform the shaman, the shaman makes spirit helpers (their ritual paraphernalia), and the spirit helpers in turn help interact with other-than-human persons. Shamanic creations thus enable shamans to have some control over powerful forces (

Halifax 1982, p. 11).

Harkening back to our previous discussion of animistic ontology, we think the subtle but major conceptual shift in archaeological perspectives, from studying

what something is to

who something is, is sometimes lost on some scholars who have written on indigenous materiality. Archaeologists and others who have studied prehistoric Southwestern art tend to think about “

what” is being portrayed on pottery, in rock art, murals, stone carvings, and other media. They may seek to identify the species of animals reflected in painted images (

Jett and Moyle 1986;

VanPool and VanPool 2009), the activities people are portrayed doing (

Munson 2000;

VanPool and VanPool 2006), the layout and design structure of decorated fields (

Di Peso et al. 1974;

Hendrickson 2003), and so forth. These studies are worthwhile, and we do not want to take away from them. Determining that a specific icon reflects a Mesoamerican-inspired horned-plumed serpent provides meaningful insight into past and present artist traditions (

Schaafsma 2001). However, in an animistic ontology, such an approach misses a central aspect of the art—its spirit. The spirit of the art may in fact be most central to understanding the art, given that it is the reason the artist made it in the first place (

Roe 2004).

For our analysis, we wish to grapple with who specific features and objects from the Medio Period are. One example, a pot, was likely made in conjunction with shamans to serve as a spirit helper. The other, a public ceremonial mound, was likely made at the community level, and likely had roles that tied into but also transcended individual shamans. Our approach to understanding these other-than-human individuals will focus on reconstructing their identity within the animistic world of the Medio Period. Identity is another great anthropological concept that is almost as old as animism. According to many anthropologists, social identity is multifaceted and situationally constructed to include aspects of age, gender, class, ethnicity, religion, and much more. For example,

Kroeber (

1917) found that the Zuni constructed their identities based on family units and clans, as well as on membership in fraternities and kiva societies. Furthermore, the Zuni share an identity as members of the Zuni Tribe, as Southwestern Pueblo people, and even more broadly as Native Americans (

Ferguson 2004). According to

Ferguson (

2004, p. 29), “individual Zuni people use all of these identities to define themselves in various social contexts.” This pattern of hierarchically and horizontally organized and context-flexible identity is typical for humans (

Jenkins 2014). Other-than-human persons likewise fit within social structures that shift based on context. As a result, these non-human agents have distinct identities that parallel the identities of humans. The Zuni kachina demonstrate this well, as their roles and relationships with humans shift based on the ceremonial calendar, the specific ceremony, and the requirements of the community (

Bunzel 1992).

Notions of personhood therefore necessarily involve issues of social identity, which we use as our foothold to consider the cognitive structure underlying examples of Casas Grandes art. The composition of the art, the context of its presentation, and its association with other objects (however defined) will provide information about the other-than-human person’s social identity. Medio Period art focuses on the horned-plumed serpent, the central deity of the Casas Grandes world. Although the horned-plumed serpent and its relationship to humans is literally emphasized in every aspect of Medio Period religious imagery, we focus here on two examples—a painted pot that reflects the structure of the Casas Grandes cosmos and an effigy mound used to divert water at Paquimé.

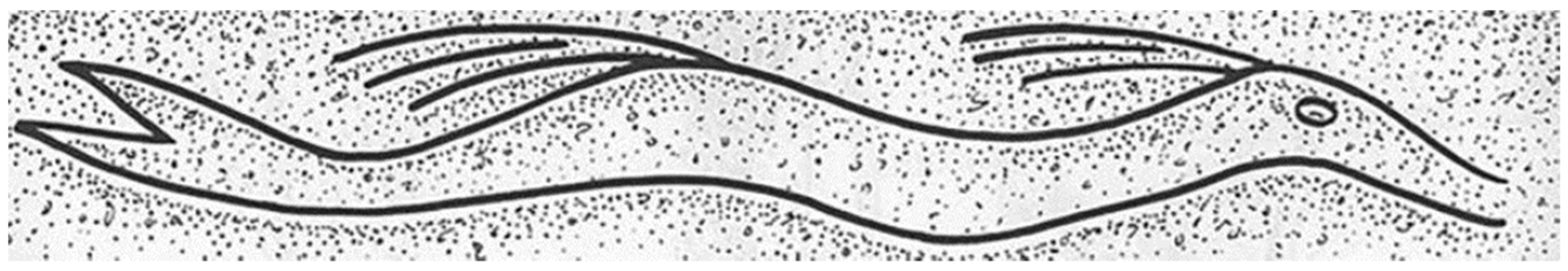

Our first example is painted designs on a Ramos polychrome that reflect the spirit world though which the Medio Period shamans travelled (

Figure 5).

Figure 4 shows a sequence of images reflecting the transformation of the shamans into macaw-headed anthropomorphs. Based on ethnographic analogy to New World shamans, as well as shamans from around the world, it is likely that these anthropomorphs could travel through the Middle World of the here-and-now but could also access the Upper World and Lower World, which are typically not fully visible. In their travels, they can perceive the animating essences of the animistic world in a way that emphasizes the spiritual relationships and characters of the other-than-human persons that animated the Casas Grandes world.

Figure 5 reflects this shift in perception and location, as the shamans interact with deities that are typically hidden in the world of the here-and-now. This is a rollout drawing of a jar portraying the macaw-headed anthropomorphs. These figures have pound signs on their chests, which reflect that they are part of the same cluster of individuals portrayed in

Figure 4 and are shown interacting with supernatural entities, including the horned-plumed serpent, the double-headed macaw diamond that is also portrayed on

Figure 3, and the bird spirit helper that is also depicted in

Figure 4. This vessel also lacks the highly structured layout typical of Ramos polychromes (and other Casas Grandes vessels). Most Medio Period polychromes (regardless of ceramic type) are decorated using two nearly identical panels limited only to the side of the vessels, such that the vessel can be spun to see a continuous band of similar designs reflected around the entire circumference of the vessel (e.g., the other side of the Ramos polychrome in

Figure 3 is similar to the visible side) (

Brooks 1973, p. 11;

Kidder 1916, p. 261). These panels are often divided into four triangular panels (

Hendrickson 2003, p. 23;

Kidder 1916, pp. 261–62). Only rarely do designs extend to the lip and bottom of the vessels, as is the case for the designs reflected in

Figure 5 (

Brooks 1973, p. 11). This repeated structure provides the Medio Period polychromes with a rigid, predictable layout, regardless of type (

VanPool and VanPool 2002). The image rolled out in

Figure 5 breaks these norms and is unique to our knowledge. The image extends to the bottom of the vessel and lacks the panels and subsequent symmetry reflected in nearly every known Medio Period polychrome. There is little “empty space” on the pot, and the iconography is more complex than typical of other vessels. The intentional abandonment of the normal Casas Grandes polychrome design layout likely reflects that the structure of the physical world of the here-and-now is gone. It instead reflects the world of the shaman, which is “the underlying chaos of the unconceptualized domain which has not yet been made a part of the cosmos by the cultural activity of naming and defining” (

Myerhoff 1976, p. 102), or, to use

Turner’s (

1969) term, they reached

antistructure. The shamans’ shift/return to the world of the here-and-now is implied by the fact that their journey is portrayed on this pot. This pot thus makes “the unobservable” visible and as such is a literal, physical depiction of the underlying nature of reality.

The reality of the spirits and the shaman are reflected in their repeated representation on other pots and various media, including rock art. In fact, the horned-plumed serpent as an icon is frequently pecked into rock faces at springs throughout the Casas Grandes region (

Schaafsma 1998). It is also painted as an icon and a motif on pottery and is disproportionately found on male effigies (

VanPool et al. 2017). Another important spirit being is the double-headed macaw diamond (

Figure 3 and

Figure 5). It is a painted design that is disproportionately associated with women effigies and other feminine designs (

VanPool et al. 2017). We do not know what the Casas Grandes people called the double-headed macaw diamond or what it meant, but we speculate that it brought together the concept of the twins in a single deity, with one looking up and the other looking down. Perhaps the directionality of one head pointing up and the other pointing down invokes the notion of rotation and the upper and lower worlds being united. Due to its placement with macaw-headed shamans, the horned-plumed serpent, and the tutelary birds (which we discuss in the next paragraph) in

Figure 5, we suggest that it was of comparable importance to the Casas Grandes folks as the horned-plumed serpent, although it is not as commonly depicted in other aspects of iconography.

We suggest that the distinctive bird represented with the shamans in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 is a tutelary spirit. Casas Grandes artisans frequently depicted animals with enough detail to allow their genus and even species to be determined; for example, effigies and painted images depict the same distinguishing characteristics modern biologists use to determine animal species (

VanPool and VanPool 2009). Among the animals that are clearly depicted are snakes (e.g., western coral snakes,

Micruroides euryzanthus; Sonoran Mountain kingsnakes/New Mexico milksnakes,

Lampropeltis pyromelana/L. triangulum; western diamondback rattlesnakes,

Crotalus atrox), birds (e.g., barn owls,

Tytonidae sp.; horned owls,

Bubo virginianus; killdeer,

Charadrius vociferus; as well as the previously mentioned macaws,

Ara macao and

Ara militaris), and even likely mud turtles (

Kinosternon sonoriense) (see

VanPool and VanPool 2007, p. 107;

2009). Yet, no bird in the Casas Grandes region has the distinctive characteristics of the tutelary bird, with its distinctive head crest and body shape. This bird is depicted in different styles (

VanPool 2003b), but it typically has a triangular body and two pairs of two feathers on its head, one pair of feathers are pointing forward and one pointing backward, or a set of feathers pointing straight up. Sometimes, it has explicitly human feet. Note that the feet of the bird shown in

Figure 4 are likewise odd, showing a bird with four toes as opposed to the anatomically correct pattern of three forward facing digits and a backward facing digit for stability and support. Based on the lack of correspondence to recognizable species and the occasional depiction of actual human feet, we conclude that these are not naturalistic representations of “real birds” (

VanPool 2003b, p. 166).

The tutelary bird is consistently portrayed with anthropomorphs (transformed shamans), but it sometimes occurs on the sternum of female effigies. Its association with transformed shamans prompts us to conclude it is a spirit creature that does not correspond to a typically observable animal, just as are the horned-plumed serpent and double-headed macaw diamond (i.e., they are deities typically hidden from view). We have also suggested that the association of the tutelary bird on the breastbone of female effigies indicates that females were active in aspects of shamanic rituals watching over the shaman as he made his soul flight into the spirit world (

VanPool and VanPool 2006).

The repeated nature of the three spirit creatures depicted in

Figure 5 attests to their reality in the Casas Grandes worldview, despite the fact that they do not correspond to physically observable creatures in the physical world. The artists painting pottery and making rock art chose to accurately portray their basic characteristics as described by Casas Grandes shamans. Shamans may in fact have been some of the artists themselves. We cannot overstate how much of the Casas Grandes art focuses on horned-plumed serpent imagery. It is reflected on nearly every Ramos polychrome in the form of the half-spade figure similar to the horned-plumed serpent held under the shaman’s arm in

Figure 4 (

Schaafsma 1998).

Di Peso (

1974, p. 548) considered it the patron deity of the Casas Grandes world. Again, shamans may have painted the pots with the actual icons, given their first-hand interaction with these deities. As icons, they normally have a forward pointing horn, often backward pointing plumes, a checkerboard collar, and a two-fin tail. We suggest that these repeated characteristics found on many pots indicate that they were as real in the minds of the artists as were coral snakes and the other serpents they accurately depicted. In fact, the accuracy of the representations was likely crucial to the shamans and other elites who focused on interacting with these other-than-human persons.

Another medium in which the horned-plumed serpent was portrayed is the Mound of the Serpent (

Figure 2). The Mound is a 113 m long, north–south-oriented mound. At one end is a raised platform (14.0 m long by 10.3 m wide by 1.2 m high) shaped like a serpent’s head; a road damaged the serpent’s horn/plume, preventing us from knowing its specific form. The head is attached to a sinuous body/retaining wall (70 cm high and ranging in width between 3.5 and 1.3 m). The Mound was an important water control feature that directed water away from the community (

Di Peso et al. 1974, p. 478). After the city was abandoned, an arroyo cut through the serpent’s body and damaged part of the site. The serpent’s tail points to a large spring 6 km away that is decorated with horned-plumed serpent rock art and is the source of water for Paquimé’s main canal (

Walker and McGahee 2006, p. 197;

Schaafsma 1998). Embedded in the Mound’s head were two caliche (stone) eyes. The eastern eye (which faced toward the city) had a mortar hole ground completely through it and may have been used for ceremonial grinding of maize or other materials. The western eye had an incised Mesoamerican-style “plumed serpent,” which is distinct from the Casas Grandes horned-plumed serpent (

Figure 6); it lacks a horn, is more sinuous compared to the more jagged body structure of the Casas Grandes serpent, and has feathers flowing from the top of the head and from the middle hump of the back. The horned-plumed serpent on pottery lacks the feathers coming off the middle of the back. These artistic differences are certainly intentional, and likely reflect distinctions in the spirits being referenced in the iconography.

Above, we said that the horned-plumed serpent had no physical counterpart, but that was not quite right. There is no animal that looks like the horned-plumed serpent, but the Mound of the Serpent gave it a real, physical presence at Paquimé that would be evident to everyone. It personified the horned-plumed serpent as a literal water-controlling, terrestrial serpent that was tied to the landscape both at Paquimé and the more distant spring, and the large head (14 × 10 m) was likely used for public ceremonies, as was the case for other platform mounds at Paquimé (

Di Peso et al. 1974, p. 478). In this personification, the horned-plumed serpent was an active agent impacting the daily life of Paquimé’s inhabitants. The eyes provide further insights. The etching on the western eye indicates that the Serpent Mound was either seeing a reflection of himself in the sky or was viewing another plumed serpent to the west. Given the morphological differences between the Casas Grandes horned-plumed serpents and the fact that the western eye’s serpent is different with feathers on its back, we suspect this second interpretation is more likely, and the Casas Grandes Mound serpent is seeing a different deity in the distance. The mortar hole in the eastern eye, which faces the city and its occupants, would have been of limited utility for grinding maize or other materials. Instead, it resembles a pupil, indicating that the serpent was keeping a watchful eye on the inhabitants. Thus, we suggest that Mound of the Serpent has one eye watching the spirit world while the other eye is watching the mundane world. Perhaps like Zia Pueblo’s

Gacítiwa, it could reward or punish people and the community based on how well they maintained their respectful relationships with the other-than-human persons that animated their world.