The Material Culture of Buddhist Propagation: Reinstating Buddhism in Early Colonial Seoul

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Reinscribing Korean Buddhism in Seoul: The Founding of a Propagation Space

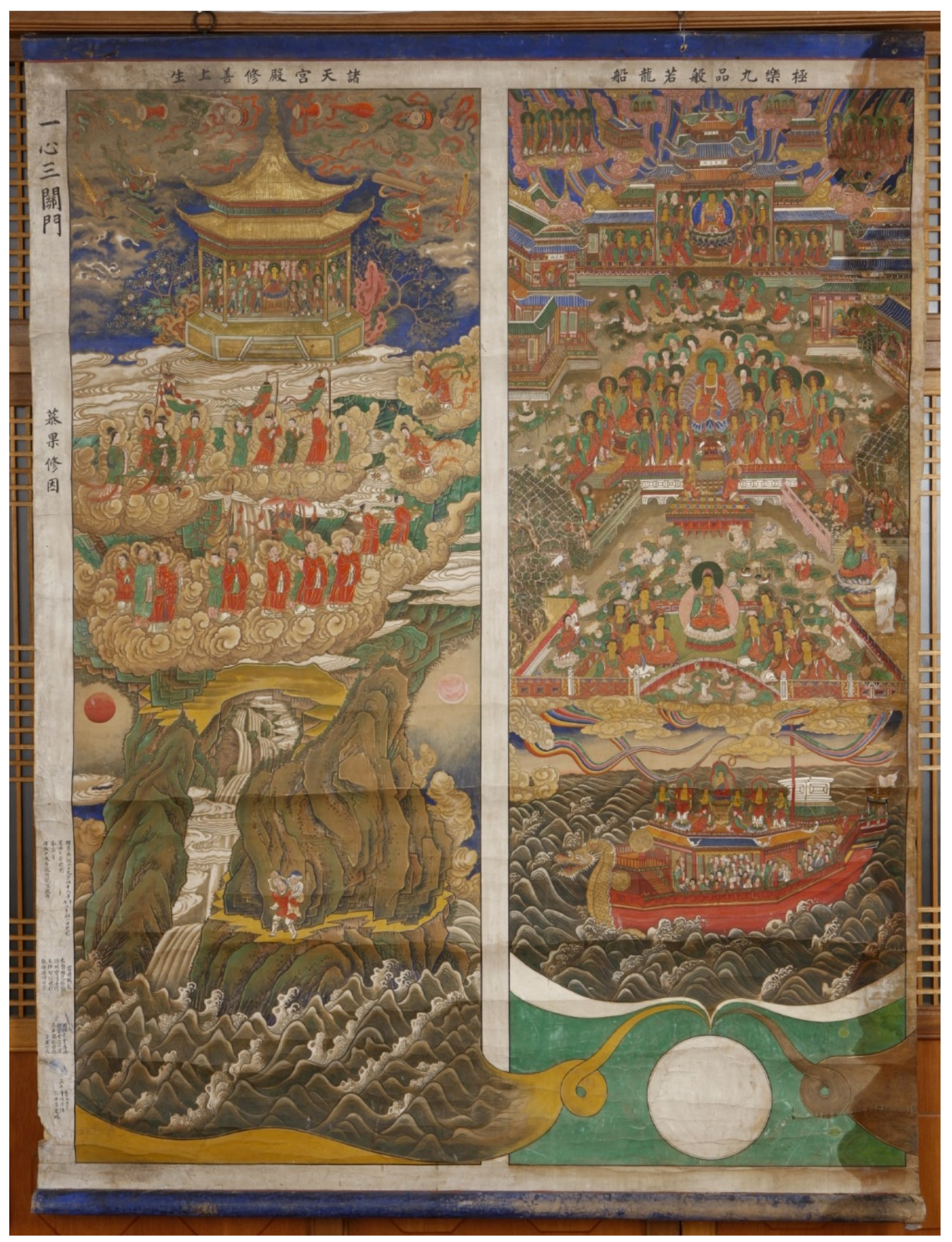

3. Creating a Visual Emblem of Propagation: The Painting and Its Iconography

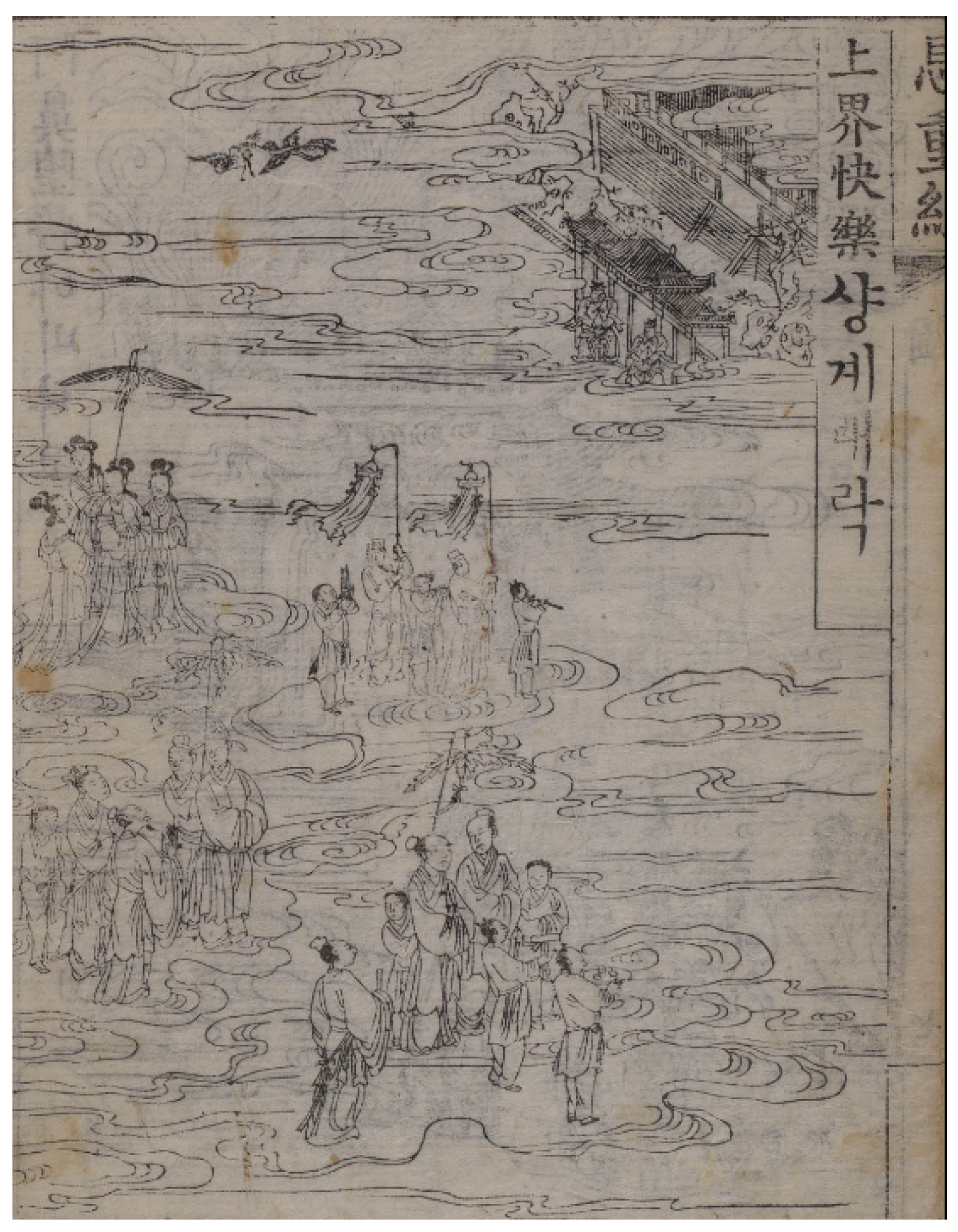

Began on the first day of the third lunar month in the sinyu year, the 2948th year since the birth of Śākyamuni, the honored one. Reported its completion on the day of bathing the Buddha. Enshrined in the Sŏlpŏpchŏn of the Buddhist Central Propagation Space. Staff at the time. Supervisor Hoegwang Sasŏn. Verifier Podam Poha. General affairs Chisang Sesin. Religious affairs Hwaryŏn Segwan. Financial affairs Taeun Chonu. Composition Kosan Chukyŏn. Painters Haksong Hangnul and Ch’oam Sebok. Painters responsible for composition of the wisdom boat. Novice Chŏngsun and layman Yi Pyŏnggu釋尊降誕二千九百四十八年辛酉三月初一日起始 灌佛日告功仍 奉安于 佛敎中央布敎所說法殿內 當時職員 監督晦光師璿 證明寶潭普荷 庶務智相世信 敎務活淵世觀 財務大雲尊雨 出草古山竺演 畵工鶴松學訥 草庵世復 般若船出草 畵工 淨順沙彌 信士李秉球

4. Propagating Buddhism in New and Old Styles

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The rescinding of this infamous law has been widely portrayed as the starting point of modern Korean Buddhism, see (Sŏ 1973, p. 41; 2006, p. 59; Kim 1998, p. 33). For more on this event and its historical implications, see (Kim 2012, pp. 123–28). |

| 2 | The religious topography of 1920s Seoul is outlined in (Kim 1924). The notion of competition for lay followers was shared by many Korean Buddhist reformers in the early colonial period. See (Nathan 2018, pp. 56–57). |

| 3 | By 1926, Christianity had expanded rapidly on the peninsula with a Korean congregation of more than 340,000, whereas Korean Buddhist temples had a native congregation of 210,000. See (Chōsen shyūkyōkai genjyō 1926). The article divides the number of followers into the three categories of Japanese settlers, Koreans, and foreigners, although it does not identify the source of these numbers. By the end of the Japanese colonial period in 1945, there were more than 400 Korean propagation establishments, the majority of which had been founded after the mid-1920s. See (H. Kim 2018, p. 234). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Hoegwang was his dharma sobriquet (pŏpho 法號). His ordination names (pŏmmyŏng 法名) were Sasŏn 師璿 and Yusŏn 有璿. |

| 6 | See (Kagan 1941, pp. 325–36). For more on his life, see (Kim 2012, pp. 230–234; Hyedam 2002, pp. 116–24). For a later critique of his pro-Japanese deeds, see (Im 2005, pp. 48–74). |

| 7 | The first Korean branch of the Higashi Honganji was established in Pusan in 1877. See (Kim 2012, pp. 109–18). |

| 8 | Tong’a ilbo 東亞日報, 3 July 1920. See also (H. Kim 2018, pp. 189–90). |

| 9 | The contents of the compact were reported in Maeil sinbo 每日申報, 2 April 1911. |

| 10 | Tong’a ilbo, 24 June 1920. In 1926, Yi Hoegwang made another failed attempt to build the great head temple of Korean Buddhism in Seoul, where Śākyamuni, Emperor Meiji 明治天皇 (r. 1867–1912) and Emperor Kojong 高宗 (r. 1864–1907) would be enshrined together. See Tong’a ilbo, 12 May 1926. |

| 11 | |

| 12 | Visual and textual sources related to the Sŏnwŏnjŏn area are collected in (Munhwajaechŏng 2014b). |

| 13 | The secret deals were first reported in Tongnip sinmun 獨立新聞, 8 January 1920. For the interview of the vice minister to the Office of Prince Yi Household, see Maeil sinbo, 19 January 1920. For more on the development of the events, see (C. Kim 2014b, p. 82; Munhwajaechŏng 2014b, pp. 117–19). |

| 14 | On 22 November 1919, Yun Ch’iho 尹致昊 (1865–1945), a politician and important activist, criticized Min Pyŏngsŏk 閔丙奭 (1858–1940) and Yun Tŏkyŏng 尹德榮 (1873–1940), the highest Korean officials of the Office of Prince Yi Household, for selling out the departed emperor’s palace and land within the Yŏngsŏngmun to the Japanese in his diary. See (S. Yi 2004b, pp. 178–79). |

| 15 | Maeil sinbo, 17 February 1920; 3 March 1920. See also Tong’a ilbo, 23 April 1920. |

| 16 | Tong’a ilbo, 15 May 1920. |

| 17 | The transfer of royal portraits was covered in Maeil sinbo, 18 February 1920. |

| 18 | Maeil sinbo, 11 May 1920. See also Tong’a ilbo, 15 May 1920; 25 July 1921. |

| 19 | Maeil sinbo, 22 December 1920. |

| 20 | For a reference to the Sambojŏn, see Maeil sinbo, 27 December 1920. A reference to the meditation room is found in (Koam 1990, p. 375). The Sŏlpŏpchŏn is mentioned in a votive inscription that I will examine in the next section. The two stone monuments have survived and now stand on the campus of Kyŏnggi Girls’ High School 京畿女子高等學校 in Seoul. See (Samp’ung enjiniŏring kŏnch’uk samuso 2005, pp. 183–84) for the arrangement of buildings in the late 1920s. |

| 21 | Maeil sinbo, 26 December 1920. |

| 22 | Maeil sinbo, 26 December 1920. |

| 23 | Maeil sinbo, 27 December 1920. |

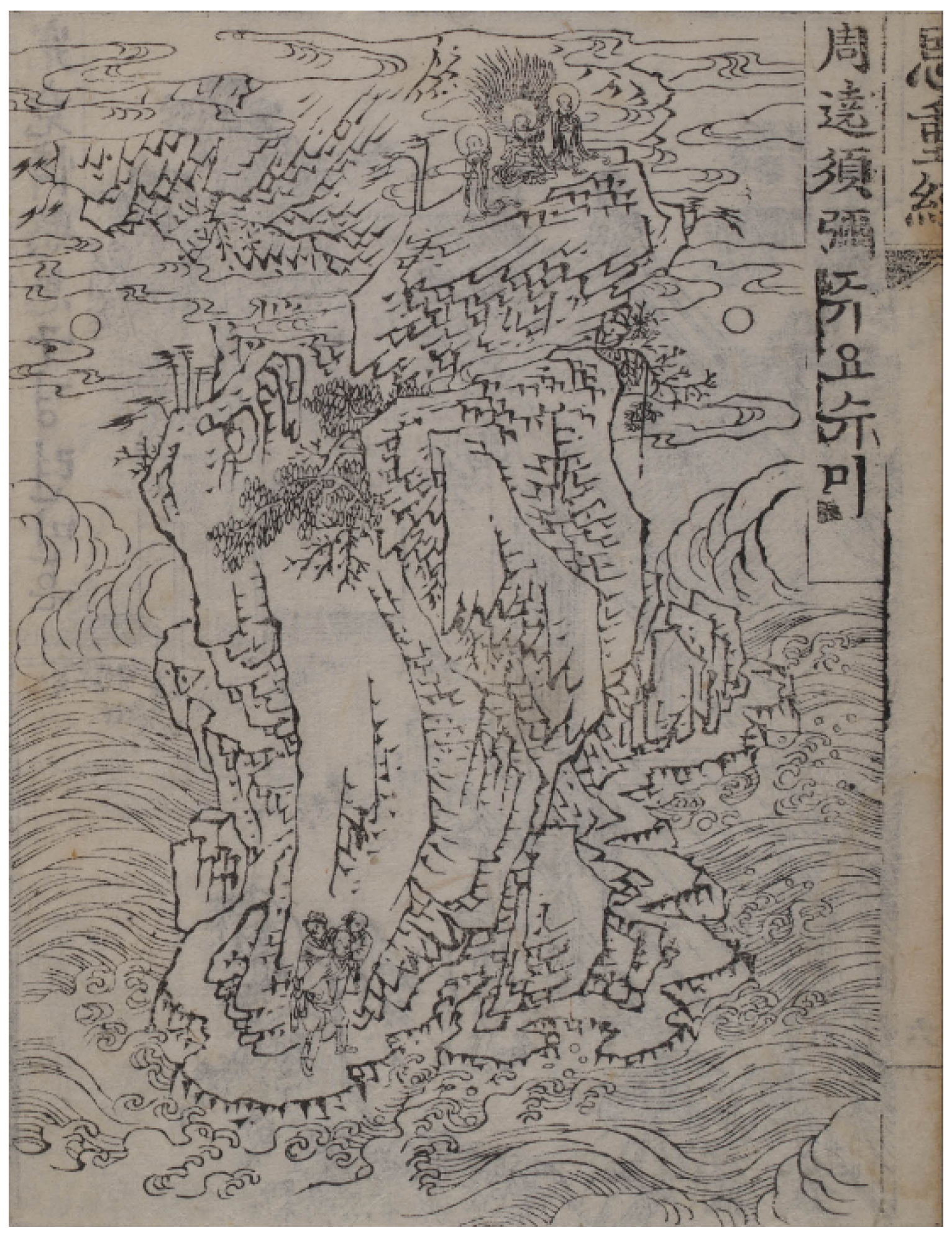

| 24 | Tong’a ilbo, 15 May 1921. For more on the celebrations for the Buddha’s birthday during the colonial period, see (P’yŏn 2002, pp. 73–103). |

| 25 | Tong’a ilbo, 25 May 1920. |

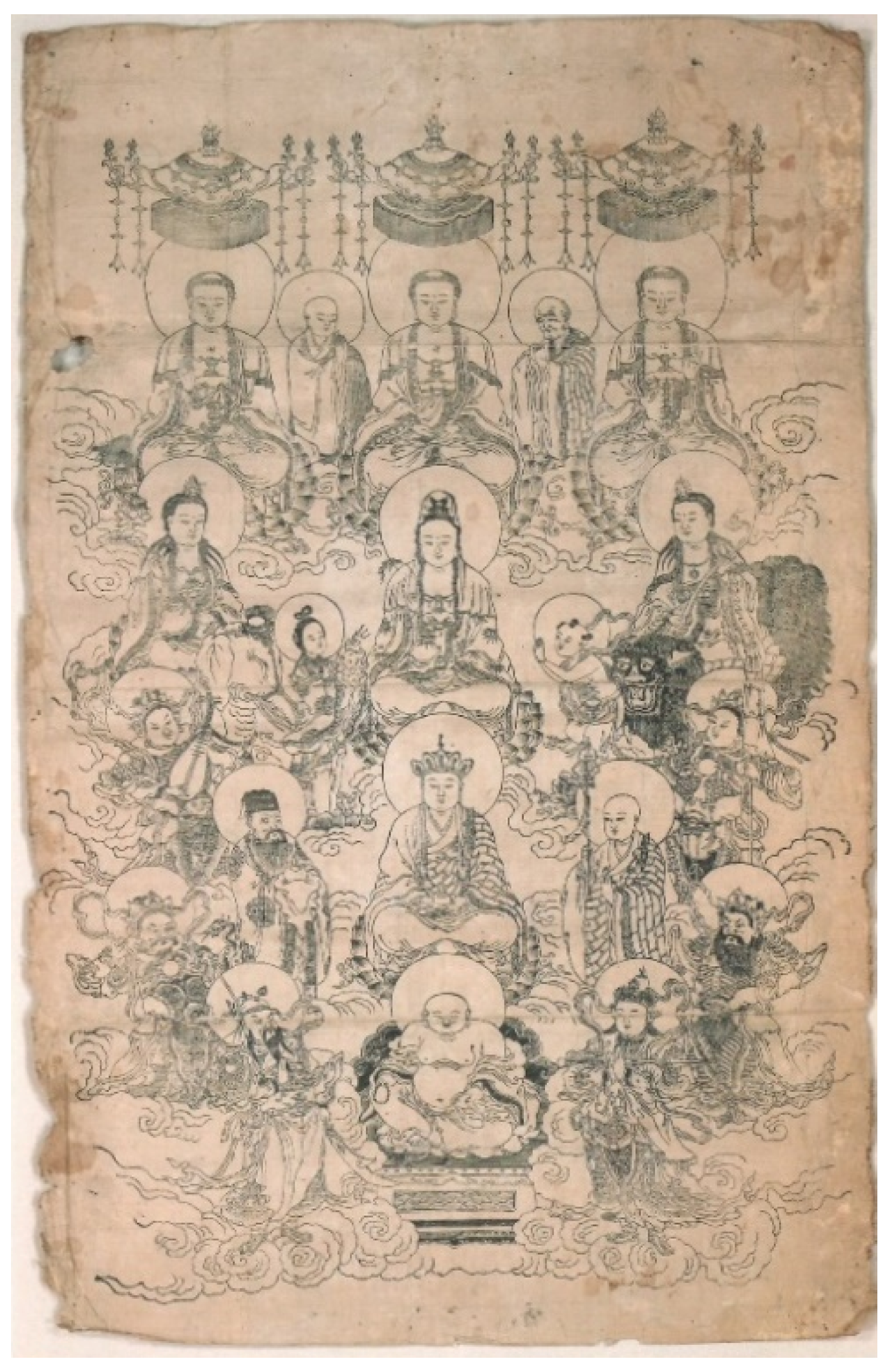

| 26 | Maeil sinbo, 5 May 1921. |

| 27 | I would like to thank Lee Jongsu for helping me grasp the meaning of this inscription. |

| 28 | The verifier of Buddhist paintings supervises whether the given works conform to Buddhist scripture and norms, and officiates various rituals that accompany their production. See (Chŏng 2016, p. 272). |

| 29 | See Maeil sinbo, 23 November 1915. |

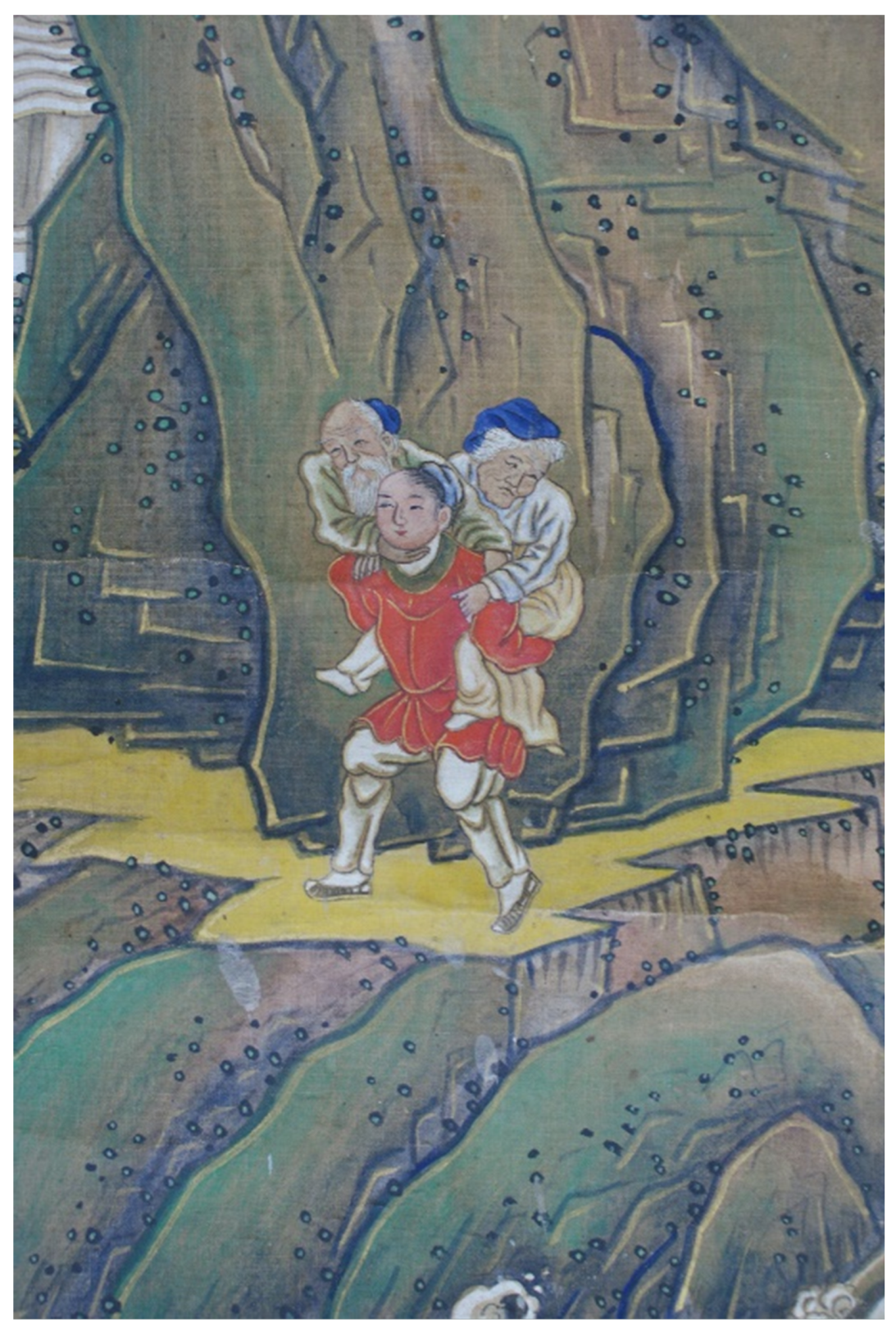

| 30 | See Maeil sinbo, 8 January 1915; 23 November 1915; 12 July 1916. See also (Ch’oe 2005, p. 167). |

| 31 | For votive inscriptions of the Tonghwasa paintings, see (Kogyŏng et al. 2011, pp. 237, 894). See (Kogyŏng et al. 2011, p. 616) for that of the Sŏnsŏksa painting and (Kogyŏng et al. 2011, pp. 255, 903–5, 1094–95) for those of the Taedunsa paintings. Ch’ukyŏn also worked with Yi Hoemyŏng 李晦明 (1866–1952), a dharma brother of Yi Hoegwang, on the production of Buddhist paintings at Yongjusa 龍珠寺 in 1913 and Chŏndŭngsa 傳燈寺 in 1916, both located in Kyŏnggi Province. See (Kogyŏng et al. 2011, p. 765) for a votive inscription of the Yongjusa painting and (Kogyŏng et al. 2011, pp. 448, 767) for those of the Chŏndŭngsa paintings. |

| 32 | For more on iconographic implications of the circle motif, see (Kang 2015). |

| 33 | For reproductions of relevant paintings, see (Pulgyo Chungang Pangmulgwan 2016, pp. 98–99, 160–169). See also (Mun 2019). |

| 34 | For more on this painting, see (Yi 2013, pp. 70–74). |

| 35 | Chŏngsun, who took a tonsure at Haeinsa in 1914, earned the dharma sobriquet of Songp’a 松坡. He was active as a painter from the early 1920s to the late 1940s. See (S. Yi 2005, p. 45). |

| 36 | Two other monk painters, Poŭng Munsŏng 普應文性 (1867–1954) and Kŭmyong Ilsŏp 金容日燮 (1900–1975), borrowed iconographic motifs from this print. Munsŏng adopted the two bodhisattvas and their attendants from the print with minor variations in the Amitābha Buddha’s Preaching Assembly, dated 1919, originally produced for Nam’am 南庵 of Chŏnghyesa 定慧寺 in Ch’ongyang, South Ch’ungch’ŏng Province. The painting is currently housed at Magoksa 麻谷寺, Kongju, South Ch’ungch’ŏng Province. Ilsŏp replicated the composition as a whole in his Assembly of All Deities from 1929 produced for Hŭngguksa 興國寺 in Yŏsu, South Chŏlla Province. A copy of the Chinese print is housed in the collection of Puyongsa 芙蓉寺, where Ilsŏp resided until 1950. See (Ch’oe 2014b, pp. 65–72). For illustrations of the relevant paintings, see (Kungnip Kongju Pangmulgwan 2012, pp. 144–49). |

| 37 | Taking cues from the mūdras and the signboards of the building, the art historian Kang Soyŏn has suggested that the scene illustrates the theme of the three bodies of buddhas ultimately being one. See (Kang 2010, pp. 171–72). |

| 38 | For more on the topic, see (Chŏn 2016, pp.173–78; Pulgyo Chungang Pangmulgwan 2020, pp. 68–72). |

| 39 | For reproductions of relevant materials in the Yongjusa collection, see (Chŏn 2016, pp. 195–97; Pulgyo Chungang Pangmulgwan 2020, pp. 73–76). |

| 40 | Ch’ukyŏn’s iconographical borrowing from folk paintings is discussed in (Ch’oe 2010, pp. 194–96; Chŏng 2020). |

| 41 | The collection is an offshoot of a nationwide survey of 3,156 Korean Buddhist paintings undertaken by the Sŏngbo Munhwajae Yŏn’guwŏn 聖寶文化材硏究院. The paintings and scholarly findings, published as a forty-volume series from 1996 to 2007, serve as one of the essential sources for the study of Korean Buddhist paintings. The collection also includes additional votive inscriptions examined by other scholars and the Pulgyo Munhwajae Yŏn’guso 佛敎文化財硏究所. |

| 42 | The proposals are part of Han Yong’un’s Treatise on the Restoration of Korean Buddhism (Chosŏn Pulgyo yusinnon 朝鮮佛敎維新論). This tract, together with other reform proposals by Kwŏn Sangno 權相老 (1879–1965) and Yi Yŏngjae 李英宰 (1900–1927), has been translated into English by Pori Park. For an English translation of the relevant passages, see (Gwon et al. 2016, pp. 130–34, 150–57). For a critical appraisal of Han Yong’un’s treatise and activities, see (Hur 2010). For more details on Buddhist reform proposals before the March First Movement of 1919, see (Park 2009, pp. 48–68). |

| 43 | A case of Anyang’am for which Ch’ukyŏn produced several Buddhist paintings provides an interesting comparison. See (Ch’oe 2010; Lee 2019). |

| 44 | The architectural types and features of these halls have been examined in (Kim 1999; Son 2007; Kim and Chŏn 2019, pp. 31–42). |

| 45 | For studies of the Unmunsa 雲門寺 case, see (Kim 2007, pp. 375–95; C. Kim 2018, pp. 130–39). |

| 46 | Tong’a ilbo, 28 October 1924. |

| 47 | A modern Korean translation of the piece is published in (Ch’inil Panminjok Haengwi Chinsang Kyumyŏng Wiwŏnhoe 2009, pp. 317–20). |

| 48 | Maeil sinbo, 27 May 1922. |

| 49 | Tong’a ilbo, 9 April; 23 April; 21 May; 28 May 1921. |

| 50 | Members of this lay Buddhist community held powerful positions in government, business, and the media in colonial Korea. The organization was renamed the Association of Korean Buddhism (Chōsen Bukkyōdan 朝鮮佛敎團) in 1925. For in-depth studies on the association, see (Yun 2017; H. Kim 2019). |

| 51 | See Maeil sinbo, 5 January; 14 February; 8 March; 25 March 1922. See also Tong’a ilbo, 5 January; 15 January; 5 February; 15 February; 5 March 1922. |

| 52 | Tong’a ilbo, 22 January 1922. |

| 53 | Tong’a ilbo, 10 July 1921. For the location of the school within the temple precinct, see (H. Yi 2005, pp. 183–84). |

| 54 | A monk surnamed Chin 陳, who worked as Yi Hoegwang’s translator, stole a large sum of money. See Tong’a ilbo, 7 August 1922. |

| 55 | Maeil sinbo, 2 September 1923. While the property of the propagation space was under Yi Hoegwang, that of the clinic belonged to Chang Il. See Chosŏn ilbo 朝鮮日報, 29 October 1924. The clinic had to shut down due to the financial difficulties caused by Chang Il’s fraud and embezzlement. See Tong’a ilbo, 3 October 1924; Chungoe ilbo 中外日報, 19 August 1927. |

| 56 | It is hard to fathom how appealing this was to urban residents due to the lack of supporting evidence. For a critical reassessment of propagation halls and propagators in the early colonial period, see (H. Kim 2018, pp. 239–42). |

| 57 | Maeil sinbo, 27 May 1922. |

| 58 | Maeil sinbo, 6 March 1920. |

| 59 | Tong’a ilbo, 7 August 1922; 28 October 1924. |

| 60 | Maeil sinbo, 13 February 1915. |

| 61 | For more on Empress Ŏm’s life, see (H. Han 2006). For her patronage of Buddhist paintings, see (Yu 2014). |

| 62 | |

| 63 | For instance, she patronized the dedication of the Amitābha Buddha’s Assembly (1891) and Guardian Deities (1891) of Pogwangsa 普光寺 in Kyŏnggi Province, Amitābha Buddha’s Assembly (1891) of Sugu’am 守口庵, a branch temple of Pogwangsa, and the Ksitigarbha, Guardian Deities, and Ten Kings of Hell of Sillŭksa (1906), among others (Kogyŏng et al. 2011, pp. 612, 751, pp. 957–58). See also (Ch’oe 2012a, pp. 55–57; Yu 2015, p. 173; Ch’oe 2019, p. 97). |

| 64 | The Simgŏmdang accommodated the Ten-Thousand-Day Buddha Recitation Assembly from 1934 to 1946. It was converted to the meditation hall in 1946 but is currently used as the monks’ academy (kangwŏn 講院). See (Yi 1992, pp. 614–15; Kim and Chŏn 2019, pp. 37, 41). For photographs of the two buildings, see (Munhwajaechŏng 2014a, vol. 1, pp. 276–76). |

| 65 | She is listed as the major benefactor in two records commemorating the completion of these buildings. For transcriptions of these records, see catalog entries 576 in (Pulgyo Munhwajae Yŏn’guso and Munhwajaech’ŏng 2011, p. 319) and 580 in (Pulgyo Munhwajae Yŏn’guso and Munhwajaech’ŏng 2011, p. 320). It should be noted that Lady Chŏn was a patron of Haeinsa before she met Yi Hoegwang. See catalog entry 652 in (Pulgyo Munhwajae Yŏn’guso and Munhwajaech’ŏng 2011, p. 325). |

| 66 | See catalog entry 365 in (Pulgyo Munhwajae Yŏn’guso and Munhwajaech’ŏng 2011, p. 308). |

| 67 | For her financial support for women’s education, see Hwangsŏng sinmun 皇城新聞, 16 January 1910; Maeil sinbo, 19 March 1914; Tong’a ilbo, 22 March 1921. |

| 68 | Tong’a ilbo, 3 October 1924; Sidae ilbo 時代日報, 21 May 1925. |

| 69 | Sidae ilbo, 21 May 1925. See also (Ch’oe 2019). |

| 70 | Tong’a ilbo, 14 August 1924. Properties of Haeinsa faced danger of being seized. See also Tong’a ilbo, 28 October 1924. The propagation space was temporarily closed in the spring of 1924 due to the conflict between Yi Hoegwang and Yi Wŏnsŏk, a key member of the Great Meeting of Korean Buddhism, who had bought buildings of the propagation space and 300 p’yŏng of its land. See Sidae ilbo, 39 April 1925; Maeil sinbo, 2 May 1925. |

| 71 | Monks of Haeinsa appealed the Government General of Korea to dismiss Yi Hoegwang from the abbotship because of his fraudulent act. See Tong’a ilbo, 14 October 1923. Yi Hoegwang, despite his campaign to remain in office, lost his abbotship the next year. See Tong’a ilbo, 16 September 1924. |

| 72 | Maeil sinbo, 31 March 1925; Tong’a ilbo, 20 May 1925; Sidae ilbo, 21 May 1925; Maeil sinbo, 17 August 1927; Chungoe ilbo, 19 August 1927. |

| 73 | See Chōsen Sōtokufu kanpō 朝鮮總督府官報 No. 2155, 19 March 1934. |

References

- An, Ch’angmo (Ahn Changmo 안창모). 2009. Tŏksugung: Sidae ŭi unmyŏng ŭl an’go cheguk ŭi chungsim e sŏda (덕수궁: 시대의 운명을 안고 제국의 중심에 서다). Seoul: Tongnyŏk. [Google Scholar]

- Buswell, Robert. 1993. The Zen Monastic Experience. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, P’ilgu (Chang Pilgu 장필구). 2014. 20segi chŏnban’gi Chosŏn wangsil ŭi pyŏnhwa wa Ch’angdŏkkung kŏnch’uk hwaltong ŭi sŏnggyŏk (20세기 전반기 조선왕실의 변화와 창덕궁 건축활동의 성격). Ph.D. dissertation, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, P’ilgu (Chang Pilgu 장필구), and Ponghŭi Chŏn (Bong-hee Jeon 봉희전). 2013. Kojong changnye kigan Sinsŏnwŏnjŏn ŭi chosŏng kwa Tŏksugung Ch’angdŏkkung kungyŏk ŭi pyŏnhwa (고종 장례 기간 신선원전의 조성과 덕수궁∙창덕궁 궁역의 변화). Taehan kŏnch’ukakoe nonmunjip kyehoekkye (大韓建築學會論文集 計劃系) 29: 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Hee Jung, and J. Keith Wilson. 2003. The Themes and Masters of Late Chosŏn and Twentieth-Century Korean Buddhist Brush Paintings. In Drawing of Faith: Ink Paintings for Korean Buddhist Icons. Los Angeles: Dongguk University Museum and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, pp. 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, Chunhyŏn (Jin Jun-hyeon 진준현). 1999. Tanwŏn Kim Hongdo yŏn’gu (단원 김홍도 연구). Seoul: Ilchisa. [Google Scholar]

- Ch’inil Panminjok Haengwi Chinsang Kyumyŏng Wiwŏnhoe (친일반민족행위진상규명위원회), ed. 2009. Ch’inil panminjok haengwi kwangye saryojip XIV: Ilche kangjŏmgi chonggyogye ŭi ch’inil hyŏmnyŏk (친일반민족행위관계사료집 XIV—일제 강점기 종교계의 친일협력—). Seoul: Ch’inil Panminjok Haengwi Chinsang Kyumyŏng Wiwŏnhoe. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Eunsu. 2003. Re-thinking Late 19th Century Chosŏn Buddhist Society. Acta Koreana 6: 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ch’oe, Yŏp (Choi Yeob 崔燁). 2005. Kosandang Ch’ukyŏn ŭi purhwa yŏn’gu (古山堂 竺演의 佛畵 硏究). Tong’ak misulsahak (東岳美術史學) 5: 165–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ch’oe, Yŏp (Choi Yeob 최엽). 2010. 20segi chŏnban purhwa ŭi saeroun tonghyang kwa hwasŭng ŭi ipchi: Sŏul Anyang’am ŭi purhwa rŭl chungsim ŭro (20세기 전반 佛畵의 새로운 동향과 畵僧의 입지: 서울 安養庵의 佛畵를 중심으로). Misulsahak yŏn’gu (美術史學硏究) 266: 189–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ch’oe, Yŏp (Choi Yeob 최엽). 2012a. Han’guk kŭndaegi ŭi purhwa yŏn’gu (韓國 近代期의 佛畵 硏究). Ph.D. dissertation, Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Ch’oe, Yŏp (Choi Yeob 최엽). 2012b. Kŭndaegi Pulgyogye wa purhwa ŭi chejak (근대기 불교계와 佛畵의 제작). Tong’ak misulsahak (東岳美術史學) 13: 269–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ch’oe, Yŏp (Choi Yeob 최엽). 2014a. Han’guk kŭndaegi purhwa ŭi taejung p’ogyojŏk sŏnggyŏk (한국 근대기 佛畵의 대중 포교적 성격). Misulsahak yŏn’gu (美術史學硏究) 281: 203–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ch’oe, Yŏp (Choi Yeob 최엽). 2014b. Yŏsu Hŭnguksa ŭi Chejon chiphoe to tosang yŏn’gu (여수 興國寺의 <諸尊集會圖> 도상 연구). Pulgyo misul (佛敎美術) 25: 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ch’oe, Yŏp (Choi Yeob 최엽). 2019. Sŭwisŭ sojae P’aju Pogwangsa Suguam hubulto yŏn’gu (스위스 소재 파주 보광사 수구암 후불도 연구). Misulsa nondan (美術史論壇) 48: 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ch’ŏn, Ilch’ŏng (쳔일청). 1911. Kisyŏ: Singyo puingye e iron ŭro kyŏnggo ham (긔셔: 信敎婦人界에 一言으로 경고함). Chosŏn Pulgyo wŏlbo (朝鮮佛敎月報) 3: 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Chŏn, Yŏnggŭn (Jeon Youngkeun 전영근). 2016. Naesa pulsŏ wa yangan (內賜佛書와 量案). In Hwasŏng Yongjusa (화성 용주사). Edited by Cho Wŏngyo (Jo Wongyo 조원교) and Yu Kyŏnghŭi (Ryu Kyunghee 유경희). Seoul: Kungnip Chungang Pangmulgwan, pp. 166–97. [Google Scholar]

- Chŏng, Chinhŭi (Jung Jinhee 정진희). 2020. Ch’isŏnggwang yŏrae to e kŭryŏjin sinsŏn munja tosang koch’al: Sŏul Anyang’am Kŭmnyunjŏn Ch’isŏnggwang yŏrae to rŭl chungsim ŭro (熾盛光如來圖에 그려진 神仙文字圖像 고찰—서울 안양암 금륜전 치성광여래도를 중심으로—). Han’guk minhwa (한국민화) 13: 138–63. [Google Scholar]

- Chŏng, Myŏnghŭi (Jeong Myounghee 鄭明熙). 2016. Chosŏn sidae Pulgyo ŭisik kwa sŭngnyŏ ŭi soim pyŏnhwa: Kamno to wa munhŏn kirok ŭl chungsim ŭro (조선시대 불교의식과 승려의 소임 변화—감로도와 문헌 기록을 중심으로). Misulsa yŏn’gu (美術史硏究) 31: 253–91. [Google Scholar]

- Chŏng, Wut’aek (Chung Woothak 정우택). 2007. Kŭngnak segye ŭi insik kwa misul (극락 세계의 인식과 미술). In Pulgyo misul, sangjing kwa yŏmwŏn ŭi segye (불교미술, 상징과 염원의 세계). Edited by Kuksa P’yŏnch’an Wiwŏnhoe. Seoul: Tusan Tong’a, pp. 127–65. [Google Scholar]

- Chōsen shyūkyōkai genjyō. 1926. Chōsen shyūkyōkai genjyō (朝鮮宗敎界現狀). Chōsen Bukkyō (朝鮮佛敎) 28: 54. [Google Scholar]

- Chōsen Sōtokufu. 1921. Chōsen: Shashinchō (朝鮮: 寫眞帖). Keijō: Chōsen Sōtokufu. [Google Scholar]

- Griffis, William Elliot. 1912. A Modern Pioneer in Korea: The Life Story of Henry G. Appenzeller. New York: Fleming H. Revell. [Google Scholar]

- Gwon, Sangro, Yi Yeongjae, and Han Yongun. 2016. Tracts on the Modern Reformation of Korean Buddhism. Translated and Introduced by Pori Park. Seoul: Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Hŭisuk (Han Heesook 한희숙). 2006. Kuhan mal Sunhŏn hwanggwibi Ŏm pi ŭi saengae wa hwaltong (구한말 순헌황귀비 엄비의 생애와 활동). Asia yŏsŏng yŏn’gu (아시아여성연구) 45: 195–239. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Tongmin (한동민). 2006. Sach’allyŏng ch’eje ŭi yŏksajŏk paegyŏng kwa ŭimi (寺刹令 체제의 역사적 배경과 의미). In Pulgyo kŭndaehwa ŭi chŏngae wa sŏngkyŏk (불교 근대화의 전개와 성격). Edited by Taehan Pulgyo Chogyejong kyoyukwŏn Purhak yŏn’guso (대한불교 조계종 교육원 불학연구소). Seoul: Chogyejong Ch’ulp’ansa, pp. 93–134. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Yong’un. 1913. Chosŏn Pulgyo yusinnon (朝鮮佛敎維新論). Kyŏngsŏng: Pulgyo Sŏgwan. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Todd A. 2007. Respatializing Chosŏn’s Royal Capital: The Politics of Japanese Urban Reforms in Early Colonial Seoul, 1905–19. In Sitings: Critical Approaches to Korean Geography. Edited by Timothy R. Tangherlini and Sallie Yea. Honolulu: University of Hwaii Press, pp. 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Todd A. 2014. Assimilating Seoul: Japanese Rule and the Politics of Public Space in Colonial Korea, 1910–1945. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoemyŏng (晦明). 1991. Hoemyŏng munjip (晦明文集). Edited and translated by Kwŏn T’aeyŏn (권태연). Seoul: Yŏrae. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, Nam-lin. 2010. Han Yong’un (1879–1944) and Buddhist Reform in Colonial Korea. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 37: 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyedam (혜담), ed. 2002. 22in ŭi chŭng’ŏn ŭl t’onghae pon kŭnhyŏndae pulgyosa (22인의 증언을 통해 본 근현대 불교사). Seoul: Sŏnu toryang Han’guk kŭnhyŏndaesa yŏn’guhoe. [Google Scholar]

- Im, Hyebong (임혜봉). 2005. Ch’inil sŭngnyŏ 108in: Kkŭnnaji anŭn yŏksa ŭi murŭm (친일 승려 108인: 끝나지 않은 역사의 물음). P’aju: Ch’ŏngnyŏnsa. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan (覺岸). 1941. Tongsa yŏlchŏn (東師列傳). Kyŏngsŏng: Chosŏnsa P’yŏnsuhoe. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Sŏkju (강석주), and Kyŏnghun Pak (경훈박). 2002. Pulgyo kŭnse paengnyŏn (불교근세백년). Seoul: Minjoksa. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Soyŏn (Kang Soyon 강소연). 2010. Kang Soyŏn ŭi misulsa kihaeng (9): Chŏnt’ong purhwa ŭi ch’angjojŏk chaehyŏn Ilsim samgwanmun t’aeng (강소연의 미술사기행(9): 전통불화의 창조적 재현 <一心三關門幀>). Munhak/Sahak/Ch’ŏrak (문학/사학/철학) 23/24: 166–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Soyŏn (Kang Soyon 강소연). 2015. Yŏngga ch’ŏndo ŭi tosang haesŏk ‘pyŏngnyŏn tae wa wŏnsang’: Chosŏn hugi kamno to wa kŭngnak kup’um to rŭl chungsim ŭro (靈駕薦度의 도상해석 ‘碧蓮臺와 圓相’—조선후기 甘露圖과 極樂九品圖를 중심으로—). Han’guk pulgyohak (韓國佛敎學) 73: 341–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Chihŏn (Kim Gee-heon 김지헌), and Ponghŭi Chŏn (Bong-hee Jeon 봉희전). 2019. 19segi wa 20segi ch’o yŏmbultang ŭi suyong (19세기와 20세기 초 念佛堂의 수용). Kŏnch’uk yŏksa yŏn’gu (건축역사연구) 28: 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Chiyŏn (Kim Jiyeon 김지연). 2014a. Chosŏn hugi panya yongsŏn to yŏn’gu (朝鮮後期 般若龍船圖 硏究). Misulsahak yŏn’gu (美術史學硏究) 281: 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Chŏngdong (김정동). 2004. Kojong hwangje ka saranghan Chŏngdong kwa Tŏksugung (고종황제가 사랑한 정동과 덕수궁). Seoul: Parŏn. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Chŏngdong (김정동). 2014b. Tŏksugung Sŏnwŏnjŏn yŏngyŏk ŭi yŏksa wa kojŭng yŏn’gu (덕수궁 선원전 영역의 역사와 고증 연구). In Tŏksugung Sŏnwŏnjŏn pogwŏn chŏngbi kibon kyehoek (덕수궁 선원전 복원정비 기본계획). Edited by Munhwajaechŏng. Taejŏn: Munhwajaechŏng, pp. 78–199. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Chŏnghŭi (Kim Junghee 김정희). 2018. Chosŏn hugi Unmunsa ŭi purhwa wa pulsa (조선 후기 운문사의 佛事와 불화). Kangjwa misulsa (講座美術史) 50: 109–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hwansoo Ilmee. 2012. Empire of the Dharma: Korean and Japanese Buddhism, 1877–1912. Boston: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hwansoo Ilmee. 2018. The Korean Buddhist Empire: A Transnational History, 1910–1945. Boston: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hwansoo Ilmee. 2019. Who Gets to Represent Korean Buddhism? The Contest to Control Buddhism in Colonial Korea, 1920–45. The Journal of Japanese Studies 45: 339–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hyogyŏng (金孝敬). 1933. Chōsen ni okeru shinkō no genjyō (朝鮮に於ける信仰狀態の現狀). Chōsen Bukkyō (朝鮮佛敎) 92: 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Kijŏn (金起田). 1924. Chae Kyŏngsŏng kak kyohoe ŭi ponbu rŭl yŏkbanghago (在京城 各敎會의 本部를 歷訪하고). Kaebyŏk (開闢) 48: 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Kwangsik (Kim Gwangsik 金光植). 1995. 1910nyŏndae Pulgyogye ŭi Chodongjong maengyak kwa Imejojong undong (1910年代 佛敎界의 曹洞宗 盟約과 臨濟宗 運動). Han’guk minjok undongsa yŏn’gu (한국민족운동사연구) 12: 97–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Kwangsik (Kim Gwangsik 김광식). 2003. Kakhwangsa ŭi sŏllip kwa unyŏng: Kŭndae Pulgyo ch’oech’o ŭi p’ogyodang yŏn’gu (각황사의 설립과 운영—근대불교 최초의 포교당 연구—). Taegak sasang (大覺思想) 6: 9–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Kyŏngjip (김경집). 1998. Han’guk kŭndae Pulgyosa (한국근대불교사). Seoul: Kyŏngsŏwŏn. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Migyŏng (Kim Migyeong 김미경). 2007. 19segi Manil yŏmbulhoe ŭi sŏnghaeng kwa Unmunsa purhwa (19세기 萬日念佛會의 성행과 雲門寺 불화). Pulgyo misulsahak (佛敎美術史學) 5: 375–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Paekyŏng (Kim Baek Yung 김백영). 2009. Chibae wa konggan: Singminji tosi Kyŏngsŏng kwa cheguk Ilbon (지배와 공간: 식민지도시 경성과 제국 일본). Seoul: Munhak Kwa Chisŏngsa. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sŏngdo (김성도). 1999. Chosŏn sidea mal kwa 20segi chŏnbangi ŭi sach’al kŏnch’ŭk t’ŭksŏng e kwanhan yŏn’gu: Sŏul, Kyŏnggi irwŏn ŭi pulchŏn ŭl chungsim ŭro (朝鮮時代末과 20世紀 前半期의 寺刹 建築 特性에 關한 硏究: 서울·경기 일원의 佛殿을 중심으로). Ph.D. dissertation, Korea University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sŏngsun (Kim Sung-soon 김성순). 2019. Chosŏn hugi yŏmbul kyŏlsa ŭi suhaeng munhwa koch’al: Chaegaja ŭi ch’amyŏ e ttarŭn yŏnghyang ŭl chungsim ŭro (조선후기 염불결사의 수행문화 고찰: 재가자의 참여에 따른 영향을 중심으로). Chŏngt’ohak yŏn’gu (淨土學硏究) 32: 245–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sunsŏk (Kim Sunseok 金淳碩). 1994. Kaehanggi Ilbon Pulgyo chongp’adŭl ŭi Han’guk ch’imt’u”: Ilbon sach’al kwa pyŏrwŏn mit p’ogyoso sŏlch’i rŭl chungsim ŭro (開港期 日本 佛敎宗派들의 韓國 浸透—일본 사찰과 별원 및 포교소 설치를 중심으로). Han’guk tongnip undongsa yŏn’gu (한국독립운동사연구) 8: 127–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Yongsuk (김용숙). 1987. Chosŏn cho kungjung p’ungsok yŏn’gu (朝鮮朝 宮中風俗 硏究). Seoul: Ilchisa. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Yunjŏng (Kim Yoonjeong 김윤정), Sŏ Ch’isang (Seo Chisang 서치상), and Yi Mina (Lee Mina 이미나). 2012. Kaehang ihu Ilbon Pulgyo ŭi ch’imtŭ e ttarŭn sawŏn ŭi kŏllip kwa kŏnch’uk t’ŭksŏng kaegwan (개항 이후 일본불교의 침투에 따른 사원의 건립과 건축특성 개관). Kŏnch’uk yŏksa yŏn’gu (건축역사연구) 21: 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Koam (고암). 1990. Chabi posal ŭi kil (慈悲菩薩의 길). Seoul: Pulgyo Yŏngsanghoebosa. [Google Scholar]

- Kogyŏng (고경), Songch’ŏn (송천), Yi Chongsu (이종수), Hŏ Sangho (허상호), and Kim Chŏngmin (김정민), eds. 2011. Han’guk ŭi purhwa hwagijip (韓國의 佛畵 畵記集). Yangsan: Sŏngbo Munhwajae Yŏn’guwŏn. [Google Scholar]

- Kungnip Kongju Pangmulgwan (국립공주박물관). 2012. Magoksa kŭndae purhwa rŭl mannada (마곡사 근대불화를 만나다). Kongju: Kungnip Kongju Pangmulgwan. [Google Scholar]

- Kwŏn, Sangno (權相老). 1917. Chosŏn Pulgyo yaksa (朝鮮佛敎略史). Kyŏngsŏng: Sinmungwan. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Seunghye. 2019. Aspirations for the Pure Land Embodied in a Modern Korean Temple, Anyang’am. Acta Koreana 22: 35–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Seunghye. 2021. Korea’s First Museum and the Categorization of “Buddhist Studies”. Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies 21: 51–81. [Google Scholar]

- Mun, Myŏngdae (Moon Myung-dae 문명대). 2019. Chosŏn malgi (19segi, Sunjong Sunjogi) Kŭngnak kup’um to ŭi tosanghak (조선 말기[19세기, 순종 순조기] 極樂九品圖의 圖像學). Kangjwa misulsa (講座美術史) 52: 331–43. [Google Scholar]

- Munhwajaechŏng (문화재청). 2014a. Hapch’ŏn Haeinsa chŏngmil silch’ŭk chosa pogosŏ (합천 해인사 정밀실측조사보고서). 2 vols, Taejŏn: Munhwajaechŏng. [Google Scholar]

- Munhwajaechŏng (문화재청). 2014b. Tŏksugung Sŏnwŏnjŏn pogwŏn chŏngbi kibon kyehoek (덕수궁 선원전 복원정비 기본계획). Taejŏn: Munhwajaechŏng. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan, Mark A. 2018. From the Mountains to the Cities: A History of Buddhist Propagation in Modern Korea. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oda, Shōgo (小田省吾). 1938. Tokujukyūshi (德壽宮史). Keijō: Riōshoku. [Google Scholar]

- Pak, Chŏngae (Park Jeongae 박정애). 2006. Yongjusa pon Pumo ŭnjung kyŏng p’anhwa wa Chosŏn hugi hoehwa (龍珠寺本 父母恩重經 版畵와 朝鮮後期 繪畫). Pulgyo misulsahak (佛敎美術史學) 4: 162–95. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Pori. 2009. Trial and Error in Modernist Reforms: Korean Buddhism under Colonial Rule. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pulgyo Chungang Pangmulgwan (불교중앙박물관). 2016. Kkumkkunnŭn chŭlgŏum, kŭngnak (꿈꾸는 즐거움, 극락). Seoul: Pulgyo Chungang Pangmulgwan. [Google Scholar]

- Pulgyo Chungang Pangmulgwan (불교중앙박물관). 2020. Hyosim ŭro nat’un pulsim ŭi segye: Hwasan Yongjusa (효심으로 나툰 불심의 세계: 花山 용주사). Seoul: Pulgyo Chungang Pangmulgwan. [Google Scholar]

- Pulgyo Munhwajae Yŏn’guso (불교문화재연구소), and Munhwajaech’ŏng (문화재청). 2011. Han’guk ŭi sach’al munhwaje: Chŏn’guk sach’al munhwajae ilche chosa Kyŏngsangnamdo III Charyojip (한국의 사찰문화재: 전국사찰문화재일제조사 경상남도 III 자료집). Seoul: Pulgyuo Munhwajae Yŏn’guso. [Google Scholar]

- P’yŏn, Muyŏng (편무영). 2002. Ch’op’ail minsongnon (초파일민속론). Seoul: Minsogwŏn. [Google Scholar]

- Samp’ung enjiniŏring kŏnch’uk samuso (삼풍엔지니어링건축사무소), ed. 2005. Tŏksugung: Pogwŏn, chŏngbi kibon kyehoek (德壽宮: 復元∙整備 基本計劃). 2 vols, Taejŏn: Munhwahaech’ŏng. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Sŏnyŏng (Shin Sun-young 신선영). 2014. Kaehanggi ‘Kim Hongdo p’ungsokhwa’ ŭi mobang kwa hwaksan (개항기 ‘김홍도 풍속화’의 모방과 확산). Misulsahak yŏn’gu (美術史學硏究) 283/284: 115–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sŏ, Chaeyŏng (Seo Jaeyeong 서재영). 2006. Sŭngnyŏ ŭi ipsŏng kŭmji haeje wa kŭndae Pulgyo ŭi chŏn’gae (승려의 입성금지 해제와 근대불교의 전개). Pulgyo hakpo (佛敎學報) 45: 37–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sŏ, Kyŏngsu (徐景洙). 1973. Han’guk Pulgyo paengnyŏnsa (韓國 佛敎 百年史). Sŏnggok nonch’ong (省谷論叢) 4: 37–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sŏkjŏng (石鼎). 1997. Haeinsa ponmalsa ŭi t’aenghwa (II) (海印寺 本末寺의 幀畵). In Han’guk ŭi purhwa (韓國의 佛畵). Edited by Sŏngbo Munhwajae Yŏn’guwŏn (聖寶文化財硏究院). Yangsan: Sŏngbo Munhwajae Yŏn’guwŏn, vol. 5, pp. 225–30. [Google Scholar]

- Son, Sinyŏng (Shon Shinyoung 손신영). 2007. 19segi Pulgyo kŏnch’uk ŭi yŏn’gu: Sŏul, Kyŏnggi chiyŏk ŭl chungsim ŭro (19世紀 佛敎建築의 硏究: 서울∙경기지역을 중심으로). Ph.D. dissertation, Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Sŏngbo Munhwajae Yŏn’guwŏn (聖寶文化財硏究院), ed. 1997. Han’guk ŭi purhwa (韓國의 佛畵). Vol. 5 Haeinsa ponmalsa p’yŏn (ha) (海印寺 本末寺篇[下]). Yangsan: Sŏngbo Munhwajae Yŏn’guwŏn. [Google Scholar]

- Taehan Pulgyo Chogyejong (대한불교조계종). 1998. Algi swiun Han’guk Pulgyo kŭnsesa (알기 쉬운 한국불교 근세사). Seoul: Chogyejong Kirrokwan. [Google Scholar]

- Tŏksugung Kwalliso (덕수궁관리소), ed. 2020. Taehan cheguk hwangje ŭi kunggwŏl (대한제국 황제의 궁궐). Seoul: Tŏksugung Kwalliso. [Google Scholar]

- U, Tongsŏn (우동선), and Sŏngjin Pak (성진박), eds. 2009. Kunggwŏl ŭi nunmul, paengnyŏn ŭi chi’immuk (궁궐의 눈물, 백년의 침묵). P’aju: Hyohyŏng Ch’ulp’an. [Google Scholar]

- Walraven, Boudewijn. 2000. Religion and the City: Seoul in the Nineteenth Century. The Review of Korean Studies 3: 178–206. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Chigwan (李智冠), ed. 1992. Haeinsa chi (海印寺誌). Seoul: Kasan Mun’go. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Hoegwang (李晦光). 1921. Chōsen Bukkyō no kakusei to shakai jigyō (朝鮮佛敎の覺醒と社會事業). Chōsen (朝鮮) 77: 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Hyewŏn (이혜원). 2005. Kyŏngun’gung kungyŏk ŭi pyŏnch’ŏn (경운궁 궁역의 변천). In Tŏksugung: Pogwŏn, chŏngbi kibon kyehoek (德壽宮: 復元∙整備 基本計劃). Edited by Samp’ung enjiniŏring kŏnch’uk samuso (삼풍엔지니어링건축사무소). Taejŏn: Munhwahaech’ŏng, vol. 1, pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Kanggŭn (이강근). 2005. Tŏksugung Sŏnwŏnjŏn pogwŏn ŭi che munje (덕수궁 璿源殿 복원의 제문제). Kŏnch’uk yŏksa yŏn’gu (建築歷史硏究) 14: 203–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Nŭnghwa (李能和). 1918. Chosŏn Pulgyo t’ongsa (朝鮮佛敎通史). 2 vols, Kyŏngsŏng: Sinmun’gwan. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Sŏngsi (Lee Sungsi 이성시). 2004a. Chosŏn wangjo ŭi sangjing konggan kwa pangmulgwan (조선왕조의 상징공간과 박물관). In Kuksa ŭi sinhwa rŭl nŏmŏsŏ (국사의 신화를 넘어서). Edited by Im Chihyŏn (Lim Jie-hyun 임지현) and Yi Sŏngsi (Lee Sungsi 이성시). Seoul: Hyumŏnisŭt’ŭ, pp. 265–95. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Sŭnghye (Lee Seunghye 李勝慧). 2005. Kŭndae purhwasŭng ŭi sŏyanghwapŏp suyong yŏn’gu (近代 佛畵僧의 西洋畵法 受容 硏究). Master’s thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Sunu (이순우). 2004b. T’erauch’i ch’ongdok, Chosŏn ŭi kkochi toeda (테라우치 총독, 조선의 꽃이 되다). Seoul: Hanŭljae. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Yŏnghwa (이영화). 2005a. Ilche sigi wa hyŏndae ŭi Tŏksugung pyŏnhyŏng (일제시기와 현대의 덕수궁 변형). In Tŏksugung: Pogwŏn, chŏngbi kibon kyehoek (德壽宮: 復元∙整備 基本計劃). Edited by Samp’ung enjiniŏring kŏnch’uk samuso (삼풍엔지니어링건축사무소). Taejŏn: Munhwahaech’ŏng, vol. 1, pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Yongyun (Lee Yongyun 李容胤). 2013. Chosŏn hugi Kyŏngsangdo chiyŏk esŏ chejaktoen Kwan gyŏng sibyukkwan pyŏnsang to wa yŏmbulsŏn (조선 후기 경상도 지역에서 제작된 觀經十六觀變相圖와 念佛禪). Misulsa nondan (美術史論壇) 36: 61–90. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Yŏnno (이연노). 2005b. Ilche kangjŏmgi Kyŏngun’kung ŭi kŏnch’ukchŏk pyŏnhwa (일제강점기 경운궁의 건축적 변화). In Tŏksugung: Pogwŏn, chŏngbi kibon kyehoek (德壽宮: 復元∙整備 基本計劃). Edited by Samp’ung enjiniŏring kŏnch’uk samuso (삼풍엔지니어링건축사무소). Taejŏn: Munhwahaech’ŏng, vol. 1, pp. 137–69. [Google Scholar]

- Yŏm, Pokgyu (Yum Bokkyu 염복규). 2016. Sŏul ŭi kiwŏn Kyŏngsŏng ŭi t’ansaeng: 1910–1945 tosi kyehoek ŭro pon Kyŏngsŏng ŭi yŏksa (서울의 기원 경성의 탄생: 1910–1945 도시계획으로 본 경성의 역사). Seoul: Idea. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Kyŏnghŭi (Ryu Kyunghee 유경희). 2014. Kojongdae Sunhŏn hwanggwibi Ŏmssi parwŏn purhwa (高宗代 純獻皇貴妃 嚴氏 發願 불화). Misul charyo (美術資料) 86: 111–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Kyŏnghŭi (Ryu Kyunghee 유경희). 2015. Chosŏn malgi wangsil parwŏn purhwa yŏn’gu (조선 말기 王室發願 佛畵 연구). Ph.D. dissertation, The Academy of Korean Studies, Gyeonggi-do, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, Kiyŏp (Yoon Ki-yeop 윤기엽). 2017. Ilche kangjŏmgi Chōsen Bukkyōdan ŭi yŏnwŏn kwa sachŏk pyŏnch’ŏn: Chōsen Bukkyōdan imwŏnjin ŭi kusŏng kwa iryŏk ŭl chungsim ŭro (일제강점기 朝鮮佛敎團의 연원과 史的 변천—조선불교단 임원진의 구성과 이력을 중심으로). Taedong munhwa yŏn’gu (대동문화연구) 97: 293–322. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S. The Material Culture of Buddhist Propagation: Reinstating Buddhism in Early Colonial Seoul. Religions 2021, 12, 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050352

Lee S. The Material Culture of Buddhist Propagation: Reinstating Buddhism in Early Colonial Seoul. Religions. 2021; 12(5):352. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050352

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Seunghye. 2021. "The Material Culture of Buddhist Propagation: Reinstating Buddhism in Early Colonial Seoul" Religions 12, no. 5: 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050352

APA StyleLee, S. (2021). The Material Culture of Buddhist Propagation: Reinstating Buddhism in Early Colonial Seoul. Religions, 12(5), 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050352