1. Introduction

According to the report The Swedes and the Internet 2019 (Svenskarna och internet 2019), 98% of the Swedish population has internet access and 91% report that they are online on a daily basis. Almost 90% percent make purchases online, and the vast majority feel secure transferring money online.

1 It has over time become more and more commonplace to buy different sorts of products and services online, and this development has created possibilities for a wide range of agents to present, spread, and sell their products or services over the Internet.

2 For example, a report from the Swedish Agency for Cultural Policy Analysis (Myndigheten för kulturanalys) that deals with the matter of how cultural operators may prosper by moving their business operations online emphasises how online social networks create new possibilities for marketing ideas and products and for reaching a larger audience. In the report, one can read that:

Ideas are spread from one’s own network via the networks of others into new networks. This opens possibilities for everyone, not the least for cultural operators, who are able to communicate their ideas to a larger audience and to look for financial backers.

3As will be argued in the following, this is true also for other agents such as, for example, missionising Salafi Muslims, the group upon which this article focuses. One way of using online platforms and networks to both market and finance ideas and activities is through crowdfunding, a term that has been defined as follows: a collective effort of many individuals who network and pool their resources to support efforts initiated by other people or organizations (

Marchegiani 2018, p. 144).

Crowdfunding, then, occurs when a group of people, the majority of whom do not know or have any form of contact with the others, help finance a product or a project that they in some way appreciate or believe in. Online platforms of different sorts are increasingly being used to entice people to make small (or large) contributions (i.e., microfunding) to various projects, and through crowdfunding entrepreneurs can make use of their social networks in order to raise capital for the purposes of funding their projects and products while simultaneously attracting new followers and strengthening the social identity of the in-group.

The entrepreneurs of interest for the present article comprise a group of Salafi Muslim missionaries operating in Sweden, and the aim of the article is in part to analyse how they use crowdfunding in order to gain capital to finance some of their activities, and in part to, by making use of concepts from the fields of consumer psychology and theories of markets and philanthropy, also try to analyse why their methods have been successful (in the sense that the results of their efforts seem to have exceeded their expectations).

2. Islam.nu

Islam.nu is the name of an organisation founded by a Salafi-oriented group that has operated for nearly twenty years. It is based in a neighbourhood in the northwestern corner of Stockholm, Sweden, and has a strong online presence, both in terms of its website (i.e., islam.nu) and its activities on a number of social media platforms.

4 The organisation is managed by three individuals, all of whom grew up in Sweden, converted to Islam, and have connections to Saudi Arabia, where they have studied, or are presently studying, at the Islamic University of Madinah (IUM). Their names are Abdulwadud Frank (b. 1974), Moosa Assal (b. 1984), and Abdullah as-Sueidi (b. 1985) (

Ismail 2017). On islam.nu’s website, it is stated that it is a non-profit organisation and that they, in order to protect their autonomy, do not accept any form of financial support from the Swedish government or any other state or organisation. They do, however, accept donations from private individuals who appreciate their work.

5 The tagline that appears on the different platforms they use—“For Islamic Knowledge in Sweden”—indicates their pronounced focus on spreading what they perceive as being correct Islam, and they offer sermons and lectures as well as online and offline courses that stretch over varying lengths of time. Sermons, lectures, and courses are held in their Stockholm centre, which is called Al-Andalus (previously the Ibn Abbas Center) as well as in mosques and congregations throughout the rest of the country, and it is also possible to follow these activities online (

Ranstorp et al. 2018, pp. 139–41). They also offer a range of other products, e.g., books on Islam and software applications for mobile phones.

6 3. Source Material and Methods

The organisation islam.nu as well as the three individuals running it are active on a number of social media platforms, e.g., Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube. The present article focuses on a specific campaign called #karavanen, the Caravan, and the primary source material investigated consists of posts on Instagram. Using the search function provided by Instagram, posts tagged with the hashtag #karavanen have been located, and, out of these, posts published on the account belonging to islam.nu or on Abdulwadud Frank’s, Moosa Assal’s, and Abdullah as-Sueidi’s individual accounts have been identified and analysed. The first post appeared on 7 March 2018, and material analysed was posted during a period of time spanning two years, i.e., that is until 7 March 2020.

7 During the period in question, 155 Instagram posts having the hashtag #karavanen were published (duplicate posts and instances of reposting excluded).

The campaign #karavanen developed over time and, according to the information provided on the Instagram accounts of interest for the present purposes, it was not strictly defined from the beginning. For instance, posts containing the hashtag sometimes deal with the missionary activities of islam.nu and its founders in general, but, more specifically, the campaign also concerned a number of books and what came to be known as “convert kits” that the group produced and distributed as a result of their crowdfunding activities. It is these particular products and the funding strategies used to finance them that are at the centre of my analysis. It is possible that additional posts relating to the campaign were published that do not, for one reason or another, make use of the hashtag. Such posts are not included in my sample material.

4. Karavanen—Themes and Products

The campaign was launched on the Instagram account belonging to islam.nu on 7 March 2018 (93 likes and no comments).

8 The post is comprised of a picture of three people riding camels in the desert at sunset together with the following message: “Join/the #caravan!/Moosa Assal./Thursday 8/3, 10:00 p.m./Live on Facebook.com/islam.nu.” In the lower left-hand corner, the logo of islam.nu is included (see

Figure 1).

The project is then further explained by Moosa Assal in a video posted on the Facebook page of islam.nu the day after. Two years later, the video had been viewed 10,000 times, had been shared 89 times, and had been commented upon 386 times. This far exceeds the response received by the post on Instagram (i.e., 93 likes and no comments)

9. In the video, Assal announces that they are now planning to take their

dawa (“call to Islam” or “invitation to Islam”) online and that their missionary activities will be labelled “the Caravan”. When one analyses the video, three themes stand out:

4.1. Muslims Need to Unite against Islamophobia

In Sweden, there is a lot of hatred for Islam and Muslims, but the Caravan is an attempt to do some good and therefore cannot be bothered by “all the trolls and haters”. Assal repeatedly refers to a “we” (which could be understood as themselves and their followers but potentially as all Swedish Muslims, collectively constituting the target of the haters) said to be in the caravan together. “When they attack the Qur’an, they attack our book. When they attack Islam, it is our religion they attack. We are all in this caravan together.”

4.2. Everyone Is Important. All forms of Help Are Valuable

Assal repeatedly states that they need “their”, i.e., the viewers’, help, support, and collaboration. “I want to collaborate with you. I need your help. I am just like you. I work and try to support my family and do this in my spare time […] You ought to know that you are important. You who have liked [this post]. You who have shared [it] and commented [upon it]. You are important. […] Your voice is important. Your opinion is important. The more likes and shares and comments [we get], the more people we reach because Facebook helps us to spread [our message].”

4.3. All Who Help Will Be Rewarded

“On the Day of Judgement you will receive a mountain of

hazanat [“rewards”], a mountain of rewards, because you were part of it. You were a piece of the puzzle. You were part of the [community] that spread good even if you just liked, just shared, or just commented […] May Allah reward you all.”

10Is Assal’s video, a discourse stressing the distinction between an in-group (Muslims) versus an out-group (Islamophobes) takes form. He also states that he/islam.nu and their followers are equals and that they (islam.nu) cannot manage without the help of their followers. Furthermore, he repeatedly emphasises that social media interactions—likes, comments, shares, and donations—are an important part of their missionary work (

dawa) and will be rewarded by God. In the end of the video, Assal says they are about to begin a new fundraising campaign so that they will have the means to print additional copies of a book they had previously published,

The Prayer Book (“Böneboken”), written by Yusuf Abdul Hamid, an individual also connected to the organisation.

11 He continues by stating that they are now planning to print more copies and to distribute them at no cost throughout Sweden. At the end of the video, Moosa Assal once again asks those watching to share it and to let other brothers and sisters know about the Caravan.

Even though the printing and distribution of The Prayer Book (and, by extension, the product that came to be known as a “convert kit”) were at the centre of the Caravan campaign, briefly examining all of the posts featuring the hashtag #karavanen yields results of interest for the purposes of the present article.

5. Posting Patterns

The posts provided with the hashtag #karavanen do not deal exclusively with book production and book distribution. They include information about a wide range of the activities and products offered by islam.nu. For example, on 8 March 2018, the day after the concept was launched, they made posts touching upon a variety of topics, e.g., upcoming lectures on such topics as the prophet Ayyub (64 likes and 1 comment); the hadith (54 likes and 1 comment); and Islamophobia (116 likes and no comments). None of the posts received much follower interaction, but we might notice that the post about Islamophobia has attracted double the number of likes compared to the ones about Ayyub/Job or the hadith. We might also notice that the post published on Instagram about the campaign directs those who see it to their Facebook page; the information to be found there indicates that the video about the campaign has been: viewed approximately 10,000 times, shared approximately 90 times, and commented upon approximately 386 times. Hence, although this article focuses on material posted on Instagram, it bears remembering that the campaign was promoted on several social media platforms where such posts received more attention.

The pattern of interspersing informative posts presenting the general activities of or products offered by islam.nu with posts focusing on what through time crystallised as the campaign #karavanen was repeated throughout the two-year period analysed. Posts belonging to the former category, i.e., those concerning lectures, activities, and projects organised by islam.nu, received significantly fewer discernible follower interactions than the latter grouping, i.e., posts about the campaign. For instance, on 9 March 2018, islam.nu published a post showing a picture of

The Prayer Book. It received 161 likes and was commented upon 5 times. The text that accompanies the picture tells the reader how the response to the publication has “been fantastic”. It inspired “a lot of people” to begin to pray for the first time, and it taught others to “pray correctly”. Moreover, the text continues to state that there was a great demand for the book nationwide. It was also announced that plans were being made for a second and much larger edition of the book to be printed, and those who read the post were invited to help them finance the project: “Swish your contribution to [xxxxx] and mark it

The Prayer Book. The fundraiser will run until next Sunday at the latest but will end as soon as we have reached 50,000 SEK.”

12 (See

Figure 2).

During the days that followed, however, a few posts received a greater degree of follower interaction. On 11 March 2018, for example, Abdullah as-Sueidi posted a text-image (i.e., text set over either a plain canvas, an illustration of some sort, or a photo) that contained the following message: “I have been a Muslim for over 15 years now, but I have never seen a time when so many Muslims and non-Muslims turn to Islam alhamdulillah!” (526 likes and 22 comments). On the same day, Moosa Assal posted a text-image saying, “Let the Lord come first in your life. Prayer is Step 1. #todaysadvice” (531 likes and 0 comments). On 14 March, Abdullah as-Sueidi posted a text-image informing readers that: “The posts on the FB page Islam Nu have reached 120,458 people over the last month. An increase of 67% from the month before. #Karavanen is at full speed!” (268 likes on 5 comments). On 19 March 2018, Assal posted a picture of himself together with three other young men outside of a school where he had been invited to give a talk. The photo received 958 likes and 10 comments, a much more enthusiastic response than the previous posts had received. The same day, Abdullah as-Sueidi published a text-post saying, “Just heard that a Swedish guy became a Muslim in [the city of] Växjö this Friday. May Allah keep him steady on the religious path. #Karavanen”. It received 433 likes and 10 comments. Later that same day, as-Sueidi published another post about a person who converted to Islam as a result of their work. This one received 350 likes and 8 comments. Another category that inspires a great deal of positive follower interaction consists of posts showing the books they have been able to produce and distribute through their crowdfunding efforts.

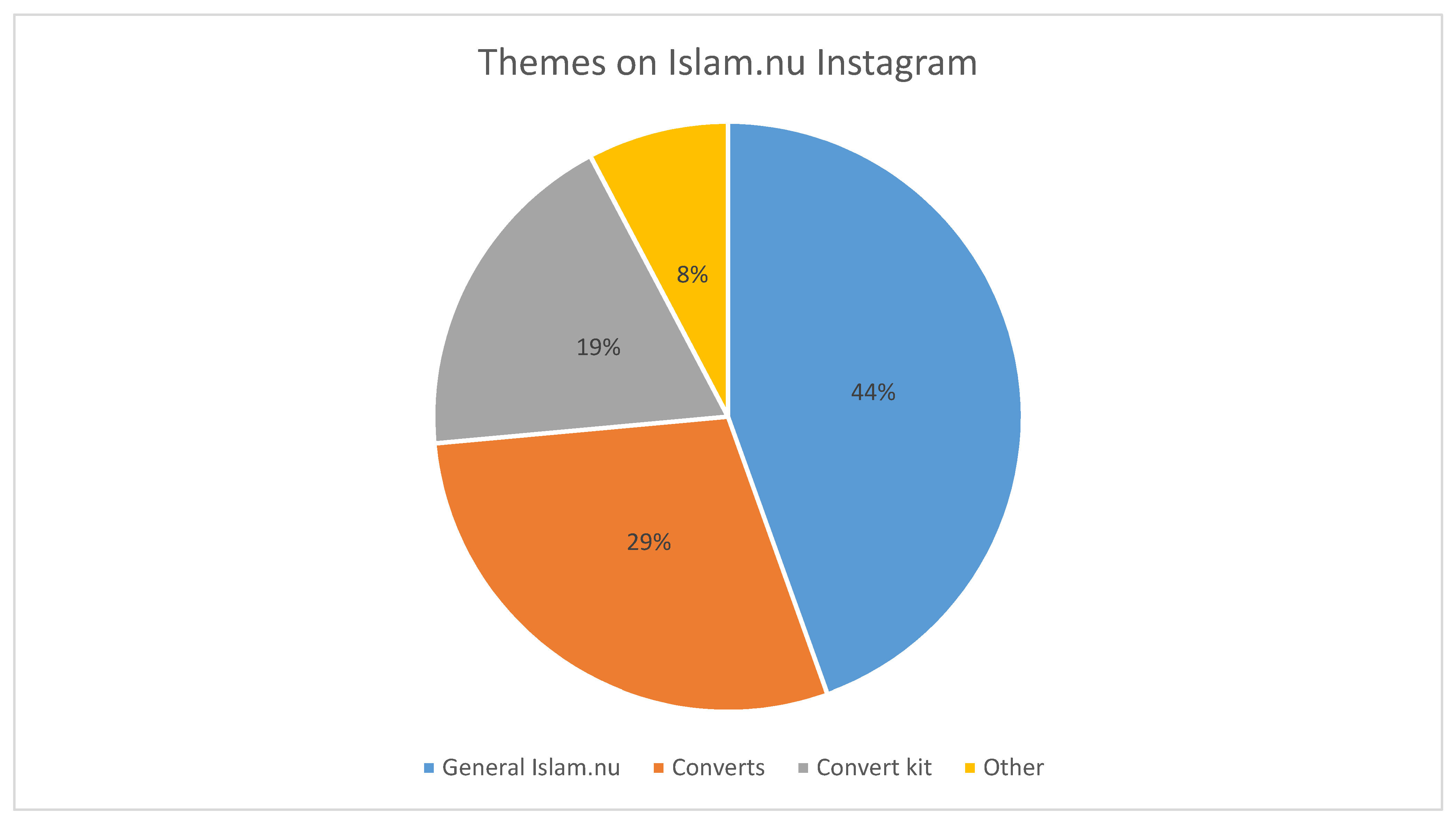

The themes described above can be said to be the most common ones found in connection with posts accompanied by the hashtag #karavanen published on the Instagram accounts of interest for the present article. Posts about lectures and courses attracted roughly between 50 and 100 likes while quotes, photos from visits to mosques in different parts of Sweden, information or updates about books the organisation was able to produce due to their crowdfunding efforts, and short texts mentioning recent conversions all received more likes during the period in question (see

Figure 3).

Regarding the last category, i.e., posts about recent conversions, these often concern “Swedes” who have converted, and the majority are about female converts denoted as “Swedish women” or “Swedish girls”. One example is found in a video posted by Abdullah as-Sueidi on 29 March 2018 in which he says:

“I just want to mention that things have been wonderful these past few days. Several people have contacted us and told us that they have become Muslims. Most of them are girls. Again, and again, girls contact us and tell us they have become Muslims, and other people turn [to us], telling us they have become Muslims, and still others have questions about Islam.”

At the end of the video, as-Sueidi explains what is actually involved in a conversion to Islam and encourages those who have any questions to contact islam.nu. According to the posts belonging to the category “converts”, 34 women and 12 men converted during the time period of relevance for this article. It is of course impossible to ascertain whether or not the information is correct, but, as suggested by a post published 11 May (see

Figure 4), islam.nu started an Instagram group for girls interested in Islam during Ramadan 2018 and one could speculate that it might have had an effect. There are also other sources suggesting that the majority of converts to Salafi Islam in Sweden are women. This was, for instance, a claim made by representatives of the Salafi

Dawa group studied by Susanne Olsson and upon which her monograph

Contemporary Puritan Salafism. A Swedish Case Study (2019) focuses (

Olsson 2019, p. 82).

For a period of time during the autumn of 2018, posts about people converting to Islam made up the majority of the sample material. One potential explanation for this is that those responsible for the content analysed the follower interaction and chose to publish more posts of a variety that tended to attract positive follower interaction. However, the fact that no similar increase occurred in connection with the most popular category of posts, i.e., photos of Moosa Assal together with other young Muslims in different cities, makes this seem unlikely. It could quite simply be the case that the increase is connected to a simultaneous increase in converts (which then might be connected to the initiative taken to start the above-mentioned Instagram group for young women). Another possible reason for the pattern might concern the matter of who was administrating the joint account during the period in question. If one turns to their individual accounts, Abdullah as-Sueidi was the only one posting about people converting on his individual account, and this could lead one to draw the conclusion that he was the one who had the greatest responsibility for managing the organisation’s account during the relevant period; this situation, then, could perhaps explain such a posting pattern.

6. The Convert Kit

Looking at the diagram above (

Figure 3), we notice how 48% percent, i.e., 74 out of 155 posts, could be assigned to the categories “convert kit” or “converts”. The fact that the majority of posts focus either on converts or the convert kit might not come as a surprise when one recalls that the organisation’s main objective is arguably to promote and spread what they consider to be correct Islam to old and new Muslims. The category “converts” concerns the sorts of posts discussed in the previous section, i.e., those announcing conversions resulting from the activities of islam.nu. The concept of a “convert kit” seems to have developed during the spring of 2018. On 9 March 2018, it was announced that they were raising money to print new copies of

The Prayer Book (161 likes and 6 comments), and on 17 March 2018 Abdullah as-Sueidi posted what he called a teaser on his account: “Keep a look out in the days ahead for incredibly good news for the Muslims of Sweden inshaAllah. It’s one of the most awesome projects in #

Karavanen!” (214 likes and 6 comments)

13 and on 29 March 2018 they introduced the “convert kit”. The picture posted shows a number of books:

The Prayer Book, which they have produced themselves; a Swedish translation of

200 Golden Hadiths from the Messenger of Allah by Abdul Malik Mujahid

14;

The Pillars of Islam and Iman (in English) by the Syrian theologian Muhammad Bin Jamil Zeno (1925–2010),

15 The Fortress of Muslims (in English) by the Saudi scholar (

al-Qahtani 2009) (b. 1951); and a Qur’an in English (in the photo posted, its cover is partly obscured by the other books, so it is impossible to see precisely which translation it is). In the accompanying text, one can read that during the last 24 h, four girls had contacted them and converted to Islam and that they had prepared four “convert kits” to send to them and to other new converts as a gift. They also ask of “all Muslims who follow the account to write a comment welcoming them [the convert girls] to the world’s largest family…#karavanen” (138 likes and 7 comments).

On 16 April 2018, another video was posted that announced the arrival of new convert kits for those who choose to accept Islam. “Already this week, a few Swedish girls have accepted Islam alhamdullilah. #karavanen” (192 likes and 4 comments). In the video, the convert kit is presented more closely. It consists of a white paper box with the logo of islam.nu printed in gold. The box contains a kufi (“if it’s a guy”) and a hijab (“if it’s a girl”), a prayer rug, argan oil, “the prayer book that you all have helped manifest”, the book The Fortress of Muslims (in English), the book 200 Golden Hadiths (in Swedish), and a white card with text in gold quoting a hadith (“Islam takes your sins away” (in Swedish)). Then, over a series of posts, images or videos of the books or the convert kits are published, as posts describe how “the Caravan is moving through Sweden” and how they are distributing the books in mosques in different cities.

On 21 December 2018, they published a video presenting a new book in Swedish that they seem to have produced themselves (and that appears to be a substitute for Muhammad Bin Jamil Zeno’s The Pillars of Islam and Iman), i.e., Islam and the Pillars of Faith (“Islam och trons pelare”), also written by Yusuf Abdul Hamid. In the post they thank all of those who have contributed financially to the campaign, while asking for further donations to print more copies of the prayer book (221 likes and 20 comments). The day after, 22 December, a post is published, saying “When we collected money for The Prayer Book, we got 90,000 SEK (approximately 9000 Euro) in 24 h. For the new book, we got 116,000 (approximately 11,000 Euro) in 2 h. #Karavanen is really moving forward.” (364 likes and 1 comment). Early the following year, on 10 January 2019, a post appeared, saying “in 2018 we sent more than 100 convert kits to new Muslims. In 2019 it will be more inshAllah! #karavanen” (327 likes and 6 comments).

On 2 February 2019, they were able to announce that they had printed 10,000 copies of

Islam & the Pillars of Faith. These are the books, they say in the video, that you, and no one else, have paid for: “May Allah reward you greatly for what you did. We will distribute these books for free in a structured way to Muslims and non-Muslims all over Sweden inshaAllah.” (242 likes and 6 comments). The day after, i.e., 3 February 2019, two ads were posted, the first of which (translated into English) reads:

ORDER BOOKS TOTALLY FOR FREE FOR YOUR MUSLIM ASSOCIATION!!

Do you run a mosque or a Muslim association or offer Islamic education for kids and need books?

Then we can send you books for free. The books we currently offer are:

(1) Islam & the Pillars of Faith.

It explains Islam and the Pillars of Faith in an easy and understandable way. It is appropriate for non-Muslims, those who recently have begun practicing, and for young people learning about Islam.

(2) The Prayer Book.

It explains the ablution and prayer in Islam in a simple way with pictures. We only accept serious requests from associations that can explain how the books will be distributed.

Fill in the form below in order to be able to receive the books for your association and we will send them to you next week insha’a Allah. (287 likes and 8 comments) (translation by the author)

In the second ad, the structure of #karavanen is also described.

Do you want to be able to influence the future of Muslims in Sweden in a positive way? Do you want to be part of spreading a nice and beautiful understanding of Islam in Sweden? Then you should support the Caravan!!

As a member of the Caravan you contribute to:

- (1)

Sweden’s most visited Islamic website.

- (2)

Sweden’s largest Islamic Facebook page.

- (3)

Sweden’s most used Islamic app.

- (4)

The convert kit, which is sent to new Muslims throughout the country.

- (5)

Printing Islamic books. which are [then] distributed freely all over the country.

- (6)

Making it possible for Muslim lecturers to hold lectures, classes, courses, and seminars across the country continuously.

- (7)

Inviting scholars from other countries who offer courses and organise conferences about Islam. And much, much more!

In order to be able to operate continuously and on a long-term basis, a lot of resources are needed. We have therefore established a direct debit account to which you can donate money on a monthly basis in a simple way. You decide yourself how much you are willing to contribute, and all sums are welcome.

Let’s all join this caravan and make it move ahead!! (146 likes and 2 comments) (translation by the author)

The posting pattern described above continues, and they soon post information about bank accounts not only for one-time donations (12 May 2019) but also for monthly donations (11 June 2019). The claimed success of the project is often stressed. For example, on 21 February 2019, they show how they visited a number of cities to distribute 1000 copies of Islam and the Pillars Faith (378 likes and 16 comments), and 25 March 2019, Abdullah as-Sueidi states that the islam.nu Facebook page is attracting more interaction than the Facebook page of the Church of Sweden (438 likes and 10 comments). On 11 July 2019, they announce that they had been able to produce yet another book, The Hajj Book (“Hadjboken”), with the help of follower donations and that they would soon be able to distribute this title as well to congregations throughout Sweden and for free to Muslims planning to perform the hajj (155 likes and 2 comments). In the text posted, Abdullah as-Sueidi also tells how “hajj firms”, i.e., travel agencies licensed to take Muslims to Mecca and Medina for the hajj and the umrah, can obtain the book to distribute to their customers.

7. Success

By following the development of #karavanen on the Instagram account of islam.nu and the individual accounts of the people behind the organisation, we can see how they successfully are able to attract followers willing to crowdfund the campaign through donations and how these donations are used to develop the campaign, i.e., through writing, printing, and distributing new books.

16 Hence, through crowdfunding they are able to spread the particular interpretation and expression of Islam they represent, both to old and to new Muslims in Sweden, and, what is more, it seems that they were also successful in having other institutions, e.g., mosques, congregations, and travel agencies, distribute the material for them. To what extent their books have been used by, e.g.,

hajj travel agencies or in local congregations in Sweden, would be an interesting topic for future research.

It seems, based upon the material examined, that #karavanen was successful in the sense that they managed to meet the goals set up for the campaign. Over a period of less than two years, they were able to produce a number of books, print them in large runs,

17 and have them distributed for free to congregations and individual Muslims all over Sweden. What reasons could account for the seeming success of the campaign? One way of trying to understand the efficacy of the campaign #karavanen is to make use of consumer theory to try to understand why a more than adequate for their purposes number of followers found the campaign attractive enough to invest their money in it.

8. The Values of Dawa

Marketing has been defined as a process or practice that facilitates an exchange or a transaction between two parties which trade something of value in return for something of greater value (

Holbrook 1996, p. 138;

Kotler 1991). “Perceived value” has therefore become a central concept within marketing research and is increasingly understood as a key factor in strategic management and marketing (

Sánchez-Fernández and Ángeles 2007). Stanley F.

Slater (

1997, p. 166) holds that “the creation of customer value must be the reason for [a] firm’s existence and certainly for its success.” A way, then, to analyse why a product sells or a campaign is successful is to discern which values inform consumer behaviour and, as is the case in this article, investigate which perceived values play a part in the marketing process. Consumer value is often perceived as a multidimensional construct, and in an influential study (

Sheth et al. 1991) five value factors that contribute to consumer decision making are enumerated:

Functional value, which reflects whether or not a product is able to perform its attribute-related, utilitarian, or physical purposes.

Social value, which refers to social and symbolic benefits offered by a product.

Emotional value, related to various affective states, experiential or emotional benefits deriving from a product (for example, joy or excitement).

Epistemic value, which concerns a desire for knowledge, whether motivated by intellectual curiosity or the seeking of novelty.

Conditional value, which reflects the fact that some market choices are contingent on the situation or set of circumstances faced by the consumers, for example in relation to some holiday (

Sheth et al. 1991).

All of the above factors do not need be present to explain a purchase, but a consumer choice might be informed by one, several, or all of the five consumer values in the model. There are, of course, differences between consumer behavioural and crowdfunding, which resembles philanthropy, but there are also sufficient significant similarities between the two to enable charitable originations to draw upon behavioural economics in their attempts to increase donations (

Aaker and Akutsu 2009;

Moysidou 2015). By combining perspectives from consumer and philanthropy studies, a study by

Karlan et al. (

2019) identifies six factors that increase the likelihood of donations being made:

Make giving easy: minimize the number of steps between impulse and transfer.

Make giving feel really good (immediately): we like doing things that give immediate positive response.

Spotlight social norms: Signal that target group peers are already contributing.

Prime the right identity: Everyone has multiple identifications, why words, images and arguments activating the right identity must be used.

Emphasize different attributes: we quickly grow used to our environments and products, which is why new and novel attributes tend to stand out.

Bundle short-term temptation with long-term benefits: Stress that contributing will give both quick results and long-term benefits.

Looking at the respective sets of five and six factors presented above, we may notice how some of them overlap, e.g., social and emotional values, function and access, and the attraction of novelty. We might also notice that many of these factors are discernible in the posts published by the individuals behind islam.nu. For example, already on 9 March 2019, when the campaign #karavanen was just starting to take form, a post informed followers about how easy they immediately could make a contribution by using the mobile payment system Swish, and throughout the time period analysed, payment options were continuously highlighted and developed. They also thanked all of their donors repeatedly and reported about how their contributions were giving immediate results: they were able to produce new books and products, and more and more people were converting. Their posts also contain reassurances that donors would receive hazanat, eternal divine rewards, in exchange for their generosity. Hence, mentions of both immediate and long-term results are discernible.

Islamic terms such as hazanat were used in a way that arguably could activate and prime followers’ Muslim identities, and by reporting the number of contributors and stressing the speed at which they were able to collect the money needed, they put both social value and the strong, positive emotions their mutual success brings in the spotlight.

We can also notice how they seem to work with what is called conditional value in the above through such efforts as distributing books, starting an Instagram group for women during Ramadan, and producing a book on the hajj to be distributed to pilgrims on their way to Saudi Arabia.

Because book production and book distribution for proselyting were financed through crowdfunding, the method utilised for raising funds can be understood, I argue, not only as a

means for mission, but also as a missionising

end in itself. Crowdfunding platforms can be understood not only as tools for community building, but also

as online communities in their own right Gerber and Hui state (2013, p. 15). Through calling out for, and contributing with, money for what is considered a good cause—in this case to spread Islam—crowdfunding platforms allow producers as well as funders to feel like valuable members of a shared community (

Aslanbay and Demiray 2016, p. 164). By contributing, followers engage in the community not only economically but also socially and emotionally. A further example of how crowdfunding possibilities were used to develop a strong sense of community and social belonging in regard to the activities of islam.nu can be seen in the case of the second of the ads quoted above, i.e., the one that invited funders to become “members” of the Caravan through their monetary donations.

Understood in relation to such a perspective, the campaign #karavanen, then, can be seen not only as being about producing new books used to spread Islam and attract new converts and followers but also as a way to engage and maintain an already existing following. Follower interaction is a result in and of itself and is thus not just a step towards future results. When focusing upon such community-building strategies visible in the source material, three themes or patterns stand out.

9. “I Am Just Like You”—In-Group Construction and Maintenance

A number of the points listed in the two studies referred to above emphasise social values and motivations, which makes crowdfunding a suitable means for religious community-building. In the material analysed, a strong tendency to use #karavanen both to strengthen the social identity of an existing group and to attract new followers can be identified. For example, in Assal’s video introducing the project as well as in later posts, we see how followers and funders are construed as an in-group, i.e., as a Muslim “we”, and that representatives of islam.nu stress how they are dependent upon their contributions. Previous studies have shown that supporters of crowdfunding campaigns are more willing to help initiators with whom they have a personal or extended connection. It is therefore imperative to establish, develop, and strengthen such relationships (

Gerber and Hui 2014, p. 14). Other studies emphasise the development of a stronger social identity and group affiliation as a vital driving force (e.g.,

Bagozzi and Dholakia 2006;

Martínez-López et al. 2016, pp. 144–46), and identification with a community has moreover been identified as a key mechanism for in-group favouritism (

Muller et al. 2014). Returning to the video from 8 March 2018 in which Moosa Assal introduces the campaign, a discourse arguably aiming at such in-group construction and maintenance might be identified as he both emphasises that he is just like them (i.e., the followers and donors), and that they are all doing the work together. The ambition and ability of the group responsible for islam.nu to communicate such reciprocity might then be understood as one factor behind the success of their campaign.

In addition to the above, he rhetorically constructed a “common enemy”—Islamophobic haters—while simultaneously stressing the need for a “we”—Muslims in general—to join forces. To designate and defy a common enemy is a common strategy for developing group identity and a rhetorical trope that also proves to be successful in online environments (

Graham 2016; see also

Coser 1956). It is also a strategy commonly and successfully used in missionary endeavours, as discussed by Luther P. Gerlach and Virginia H. Hine in their 1968 article

Five Factors Crucial to the Growth and Spread of a Modern Religious Movement.

Similar strategies for in-group construction and maintenance are also used offline in Swedish Salafi milieus. One relevant example can be found in Susanne Olsson’s study, referred to above, where Salafi teachers fostered in-group identity in almost every lecture that Olsson observed by reminding the audience that they were being oppressed by

kuffar (i.e., non-Muslims or infidels) (

Olsson 2019, pp. 166, 179). We might notice, however, that Assal, in his video, does not use the word

kuffar, which might have a divisive effect also on Muslims but instead highlights “Islamophobia” as a problem common to all Muslims. By mentioning how “haters” are attacking the Qur’an and the Prophet, he raises an issue everyone who self-identifies as a Muslim ideally could connect to rather than something that might divide them. The majority of the posts analysed for the purposes of this article are positive in nature, and this approach might also prove to be beneficial for islam.nu.

What their followers are asked to support, then, is not necessarily or primarily books and convert kits but rather something they all share: Islam. In addition to supporting community builders and entrepreneurs with whom they identify, the donors are also motivated to support a cause corresponding to their own personal beliefs and ideals that are consistent with an identity to which they aspire. These elements are also identified as motivating factors behind consumer action (

Gerber and Hui 2014, p. 16; see also

Aaker and Akutsu 2009).

10. “#Karavanen Is at Full Speed”—Success Is Attractive

The analysis of posting patterns presented above also suggests that posts showing positive results, i.e., those announcing that new books were being printed or new converts choosing Islam, resulted in higher levels of follower interaction. During the autumn of 2018, posts reporting new conversions were also among the most common, and followers were encouraged to welcome these new Muslims to the world’s largest family. Time and time again, positive messages were promoted. The individuals behind islam.nu could report about how “things have been wonderful” (29 March 2018). The response to The Prayer Book had “been fantastic”, “a lot of people [had] begun praying for the first time, while others [had] learned to pray correctly”, and more and more people wanted to contribute (9 March 2018). They had never before “seen a time when this many Muslims and non-Muslims turn to Islam alhamdulillah!” (11 March 2018) and are able to report a continuous increase in the number of new followers. By 3 February 2019 they claimed to run Sweden’s most visited Islamic website, Sweden’s largest Islamic Facebook page, Sweden’s most widely used Islamic app, and that their Facebook page attracted more interactions than the Facebook page of the Church of Sweden (25 March 2019).

Donors tend to follow the funding choices of other donors (

Herzenstein et al. 2010, a fact that is explicable in terms of the social value discussed by

Sheth et al. 1991) and the need to focus on social norms as taken up by

Karlan et al. (

2019). Hence, signalling success and repeatedly showing how money donated promptly gives positive results seem to be successful strategies.

In a number of the posts quoted above, we also saw how the organisers of islam.nu mentioned how quickly they were able to collect the funding they needed or that they would end the campaign as soon as they had received the money they required. Again, this corresponds to what has been identified as successful strategies to activate consumer decisions. For example,

Agrawal et al. (

2015) were able to demonstrate that those who support crowdfunding campaigns are more likely to invest in projects close to being fully realised (see also

Moysidou 2015). In line with such posts signalling success are of course the posts about new converts. Proselyting is arguably the central goal of all missionary efforts, and for this reason providing information about new converts is a good strategy for convincing donors that their money has been well spent. By contributing a sum of money, donors do not primarily, then, contribute to the printing of a book but to efforts to spread Islam, which means that the number of those belonging to the in-group increases, and they will therefore be rewarded by God. In a study of religious branding strategies, Sarah Banet-Weiser has pointed out similarities between investments in “green business” and “religious business”. While donations or investments in the former might make donors or consumers feel good because “buying good is doing good”, donations made to support religious endeavours may have the effect not only of doing good but of

being good because religion is “God’s business.” (

Banet-Weiser 2012, p. 176; see also

Baqutayan et al. 2018, for a discussion of motivation behind Muslim alms giving). Whether or not this is the case cannot be fully addressed within the scope of this study, but one could argue that the preachers behind islam.nu pursue a similar line of reasoning, i.e., that donations will be rewarded by God. This would presumably be a strong perceived value for the donors.

11. “More Likes and Shares and Comments”—Rings on the Water

Hence, we can see how the campaign #karavanen seems to have successfully managed not only to raise the funds needed to produce and distribute books but also to strengthen group identity while simultaneously trying to attract additional group members. A last theme to be considered in this article is how crowdfunding might be used to tap into new networks and to reach new groups or to use a more popular product in order to generate more interest in services that are less popular. As the above thematical analysis of the content of the Instagram accounts in question showed, the largest category of posts (44%, or 69 out of 155 posts), i.e., general information about activities organised and services provided by islam.nu, was also the category that attracted the lowest degree of follower interaction. Why, then, did they continue to make posts of a sort that did not provoke much follower interaction and that were not connected to the core of #karavanen, i.e., the production and distribution of books?

One way of understanding such a posting pattern is that the variety could have the effect of the more popular posts drawing attention to the less popular activities, i.e., those demanding more long-term engagement, e.g., lectures and courses, which, despite the lower level of exhibited interest, are of vital importance to the organisation. In other words, they used more popular posts to direct their follower’s attention to activities that seem to attract less attention by themselves. As a Dawa project, #karavanen, then, primarily sought to attract new followers in the hope of engaging them, as well as loyal followers, in courses offering opportunities for deepening their understanding of what the preachers running islam.nu consider to be correct Islam.

In a similar way, we were also able to see how they attempted to use the popularity of #karavanen to tap into other networks and other organisations’ core activities. For instance, the ads quoted above and a post made by Abdullah as-Sueidi offer the leaders of mosques, congregations, organisations, and Muslim schools, as well as travel agencies arranging trips for Muslim pilgrims wishing to perform the hajj, their books to distribute for free within their networks. This can be regarded as a way to encourage others to spread their message and products for them and to tap into new and expanding networks.

As stated in the introduction to this article, a report compiled by the Swedish Agency for Cultural Policy Analysis that analyses how cultural operators may prosper by moving their business online suggests that online social networks create new possibilities for marketing ideas and products and for reaching a larger audience: “Ideas are spread from one’s own network via the networks of others into new networks. [This] opens possibilities for everyone, not the least for cultural operators, who are able to communicate their ideas to a larger audience and to look for financiers.”

18 This also corresponds to one of the factors of religious diffusion discussed by the above-mentioned study by Gerlach and Hine in which “fervent and convincing recruitment along pre-existing lines of significant social relationships” is an important topic (

Gerlach and Hine 1968, p. 23). In the Instagram posts analysed for the purposes of this article, we can see how the material produced by islam.nu is offered to other organisations and institutions, e.g., travel agencies and mosques, to be to be distributed at no charge within their networks.

Through #karavanen, then, the individuals responsible for the activities of islam.nu were able to reach an already established network of followers and to expand by tapping into new networks and institutions that help them to spread their products, their religious authority and, ultimately, the Islam they are preaching. Furthermore, when they succeeded in attracting the interest of new followers, they made sure to inform them of their other activities, i.e., ones offering possibilities for gaining a greater knowledge and understanding of the Islam they preach, which also means possibilities for a deeper and more long-term engagement.

12. Conclusions

In this article, the missionaries behind islam.nu have been studied as entrepreneurs and influencers who skilfully use social media platforms and marketing strategies to promote and disseminate the specific interpretation of Islam they represent. The primary focus of the study has been a campaign called #karavanen, and the analysis has dealt with the ways in which they use crowdfunding in their missionary undertakings. When the material in question was examined in the light of multidimensional approaches to perceived value theory and theories about philanthropy, three themes emerged.

First of all, we saw how the group behind islam.nu emphasized (in the material examined here) social value in a way that can be understood as both strengthening an already existing social identity of the in-group they address and attempting to attract new followers. This was also done through the identification and mentioning of a common enemy, i.e., Islamophobic haters, in a way that was discussed in the above as being common in relation to both community building and missionary endeavours.

Secondly, the fact that the group behind islam.nu repeatedly posted positive messages and tended to focus on the progress and success of the campaign during the period in question was also discussed. When seen against the backdrop of previous studies on consumer behaviour, such a discourse can be understood in the light of studies demonstrating that donors to crowdfunding campaigns tend to be more willing to donate to successful projects, i.e., ones close to reaching their goals. The very common posts informing readers about people, primarily “Swedish girls”, converting to Islam through the activities of islam.nu were analysed with the help of this framework and were seen as a way of signalling success and as promoting functional, social and emotional value.

Lastly, we saw how islam.nu made use of their existing network to tap into other networks in order to further spread their influence in a way common to both marketing and missionising strategies, i.e., by asking followers to like and share their posts as well as by distributing the products they manufacture to other institutions that would in turn distribute them within their own networks. Here, an additional strategy was discerned according to which more popular posts could be used to draw attention to less popular ones having to do with activities of great importance for the organisation, i.e., ones aiming to deepen their followers’ engagement with Islam and with them as religious authorities.

Hence, the organisation islam.nu was successful in their crowdfunding efforts, which not only enabled them to produce and distribute books to other institutions as well as to new converts but which also served as a means to both strengthen the social identity of the existing in-group and attract additional followers to it. The fact that the campaign #karavanen was successful suggests, then, that crowdfunding can be understood not only as a means for missionary groups such as islam.nu but also as a missionising end in itself, as it was used to attract new followers and to fund a project aiming at proselytising while it simultaneously can be seen as a means to strengthen an already existing community.