2. The Primacy of Gestural Language

If a gesture is explained in terms of bodily movement that expresses intention,

2 we need to be careful to not collapse gesture into a subset of a proposition that is then deciphered in terms of sign and reference. This direction immediately separates our project from both structural analysis and prevalent semiotics. In the proposed definition of gesture as bodily movement that embodies intention, gestures are devices for immediate activation of experience. Rather than being distinct from the signified object, the body also

becomes what is signified while remaining the signifier, and this is where this reading of gesture departs from the tendencies that rely on the dichotomy that would separate the body and the gestural meaning. Moreover, when addressing tantric gestures, the subject expressing himself through prescribed movement is also the bodily subject, and this rejects the separation of the ego from the field of meaning. The gestural body is thus subject, object, and also the signifier, with the potential to shift the primacy among any of the poles, similar to the ways Merleau-Ponty explains the shift in polarities between the touching subject and the touched object. If we revisit meaning by grounding it on gestures and reexamine the philosophy of gestures based on tantric philosophy, we encounter a different model of meaning unfolding through action and revealing or expressing the self while being enacted. An integral understanding of gesture as both expressing and expressed becomes amplified in tantric gestures that go beyond mere dance and ritual gestures. While gestures in common are displayed and meant to convey something, they lack their subjectivity. Tantric gestures are not merely corporeal modes in the field of projection: they are emanations of the deities being invoked; they are the embodiment of the divinities while also being signs. The gestures we encounter in tantras are both private and public, and even among the private gestures, they are both corporeal or external and mental or internal. Gestures such as Śāmbhavī [referring to the meditation with closed eyes] and Bhairavī [referring to the meditation with open eyes] are not performed by merely closing and opening the eyes: they demand active transcendence and immanence, and a mere physical display fails to become these gestures. Tantric gestures in this light are not always intersubjective while still remaining meaningful. If we are to import the insights that we glean when reading gestures and apply them to a general theory of meaning, the paradigm becomes fluid, having a determined structure of language relevant only to some particular application. Humans did not develop language first and subsequently realize the usage of gestures. Gestures are primary and our understanding should be that language is an extension of the meaning of gestures, since common language itself is an extension of gestures. Furthermore, just as language is an extension of gestures, speech is an extended body. Accordingly, gestures are not some semantic devices imposed for the generation of meaning. The argument here resonates that of

Flusser (

2014, p. 166) that ritual gestures are directed back at themselves. As he argues, true ritual gestures are purposeless, as there is nothing for them to represent. But when we read meaning from the perspective of enactivism, the mechanisms for meaning generation are present in ritual gestures, as there is a constant interaction of the body with the environment, and like a comprehension of command, rituals do not refer to some image to mediate between what is conveying and that what is conveyed. Similar to speech acts, gestures along these lines instantaneously accomplish the task without relying on representation. We can get a cue for this from command language, as there is no additional act required in commanding than saying, “I command you.” Essentially, gestures are transformative devices that portray meaning by presenting the subject’s inner modes of being, allowing him to trace the original experience before its fragmentation into the poles of subject and object and as sign and reference. Gestures addressed here are not exhaustive nor are they read historically, as they are brought as examples for engaging a wider philosophy of meaning in order to explore the possibility of advancing the argument that gestural meaning should be foundational to any meaning theory. Tantric gestures are doubly construed. Not only do they retain the early evolutionary traits of somatic response, they also integrate meticulous conceptual representation and so we cannot address these gestures in any either/or paradigm.

Rituals in general rely on gestures. In the case of tantric rituals, whether Hindu or Buddhist, the rituals developed require gestural performance that initiates a ‘dialogue’ between the deity and the worshipper. There are specific gestures for welcoming the deity to the ceremony (

āvāhana mudrā), for offering her a seat (

āsanamudrā), for offering pleasing objects like flowers, and for bidding farewell to the deity. Along with these simple gestures, tantras provide some complex gestures (

mudrās) that the practitioner performs, such as

yoni mudrā or

Meru mudrā, that are integral to rituals and are performed during the course of enacting rituals. These gestures not only make the rituals an actual performance, they also mediate between the natural and the spiritual. Or, following the reading of

Nair (

2013), “

mudra connects the subjective and objective worlds of performance through movements.” It is in this enactment that the gestures mediate the subjects to give an exposure of the absolute, or they become the mirror image of the experiencing of the absolute. Gestures, however, are not merely the portrayal of meaning but rather they do actively constitute reality, with gestures expressing creativity embedded within self-consciousness. This is to say that gestures convey beyond what Merlin

Donald (

1993) has attributed to them; gestures convey human attempts to reconfigure reality and not just represent it. If we read tantric rituals in light of their intended magical effect, it is all the more vivid that the objective of gestures is not to represent but to create a new reality. Setting aside magical rituals, even the visualization and internal rituals (

antaryāga) are intended to transform the mental landscape of the performing subject, eventually to transform his personal experience. Whether the gesture is performed mentally or corporeally, the argument remains that gesture is inscribed in the body (

Ness 2008) when we consider the body as an extension of the mind. In this light, there is no categorical difference between a purely cognitive understanding of

khecarī or its corporeal expression in the Haṭhayoga manuals.

Tracing back to Donald’s 1993 thesis, he has argued that gestures can involve all the mimetic, mythic, and theoretic levels of human experience. It is through gestures that imaginative enactment of an event occurs. A mime, then, allows us to ‘re-live’ experience from the past, traversing episodes previously lived. Or the mime becomes an avatar for a game of counterfactuals, played now and projected into the future. This means that the mime requires acting out of a sequence of events that may happen or may have already happened. In addition to what the example of mimes reveals, gestures can express emotional attitudes, simple propositional states, or complex ideas where semantic and emotional aspects are infused. One should not think, then, that tantric gestures are only a set of gestures that do not address complex nuances. There is actually no clear demarcation between secular mimes, gestures from dance, and rituals and tantric gestures. While tantras introduce a new set of gestures, they nonetheless utilize existing gestures from the cultures of their origins. Tantric deities display the gesture of threat (

tarjanī), protection (

abhaya), giving (

dāna), to give a few examples from everyday life. The deities are portrayed in various dance gestures, making the philosophy of drama essential to understanding tantric iconography. Beyond the performance of gestures in rituals, the difference between dance and tantric gestures lies in the ways these metaphoric actions are deciphered. An understanding of Bharatanāṭyam is therefore incomplete so long as we do not engage the

Nāṭyaśāstra of Bharata (

Shastri 1971). Accordingly, reading tantric gestures simply based on ritual enactment fails to engage wealth of literature that share the meaning of gestures accreted for millennia. But we need to explore deeper, not just to discover some new meaning or complex process of enactment, but also to raise the question of ‘what does even ‘means’ mean.’ The more we engage tantric texts in deciphering and contextualizing gestures, the more we come to realize that not only are their meaning systems different, but that they are using the very concept of meaning differently. Most importantly, what is meant by ‘meaning’ here is a transformation of experience and not a representation of images. Tantric texts engage in the process of deciphering meaning, be that of gestures,

mantras, or

maṇḍalas, as mechanisms to trace consciousness back to its primordial nature, self-effulgent and non-directional while at the same time, filled with infinite potential. Therefore, reading tantric gestures is not about discovering features of a universal grammar. On the contrary, it is about how tantric rituals evade a universal appeal to representation and strive to re-live reality or reconstruct the given reality.

Along these lines, gestures are not a closure but an opening of anticipation (ākāṅkṣā). In common language, our anticipation is fulfilled when we understand X meaning Y. But gestures are not like that. There is no simple substitute of word to meaning or gesture to representation that can have the epistemic anticipation fulfilled. Even in the everyday exchange of gestures, a handshake is not just a handshake nor is Namaste just a Namaste. These gestures invite transformation, initiating an inter-subjective domain that creates a safe zone for dialogue. The point being, even the most common gestures go beyond representation and touch the heart of creativity. The gesture of invitation is about opening a space for the journey towards something unknown. When in choreography, depending upon a theme, even tears or screams of terror can be mimetic and not expressing grief or fear but humor. But the significance of gestures goes beyond this when anticipation through gesture becomes fulfilled in the realm of intersubjectivity. Our gestures are meant only to stimulate some certain responses. Our comical laughter or even cries merely stimulate humor in the audience if anticipation is fulfilled. An expression of emotions has a deeper intersubjective domain on which emotional gestures play their role.

We all are aware that natural language is deeply rooted in culture. Ritual gestures, tantric gestures in particular, go beyond a simple cultural basis, as they are metaphoric archaeological sites for cultural meaning accreted over periods of time. Stemming from the given cultural framework, these gestures express something “beyond,” but not knowing the “given” based upon which tantras layer new meaning, precludes the viewer from having direct exposure to the intended experience. Even when gestures are used as a means of communication, tantric gestures rarely fulfill any social function. We can say that these gestures are self-enclosed in this sense. Even then, these gestures are anticipated to be intersubjective and communicative, as the subjects performing rituals are ‘having’ dialogue with their intended deity. The gesture of welcoming, giving a seat, or that of farewell, constitute a dialogical sphere in which tantric subjects envision their active transaction with the deity. If their reality were to be tested on the grounds of efficacy (arthakriyā), these gestures give as much a sense of ‘direct encounter’ to the ritual subjects as our everyday social transactions. Subjects report the ‘presence’ of the deity, express their anguish and anticipations, and display the appropriate somatic response like goosebumps or tears.

Even then, what we derive from this conversation, is that the primacy of enactive meaning and the creative sphere of gestural expression open up a platform for a deeper exploration into the nature of meaning itself. What differentiates tantric gestures is not that they have an explicitly separate structure but that they subsume existing meaning when borrowing the existing ones, and whether the gestures are unique or common, tantras use them as devices of visualization and a mechanism for the transformation of experience. What the gestures mean is not erased in these new platforms. Instead, they only need to be uncovered from the layers of superimposed assumptions.

3. Theorizing Gestures

When we understand meaning as evolving from our embodied states and our interaction with the environment, we make our first attempt to free ourselves from the chain of representation. This helps us to naturalize meaning and at the same time this understanding makes it possible for a dialogue to occur between tantric philosophy and embodied phenomenology. This is not to say that these two systems can be fully mapped, or even that gestural meaning is identical in both systems. This is only to initiate a course that does not lead us to yet another dualism. Both systems initiate their conversation on bodily foundation. Gestures are not just the flesh; they are lived as they are performed, and bodily intentionality becomes central in performing some mimetic action and making some gestures. In contrast to the analytical philosophers who view meaning as propositional and conceptual, meaning in this account emerges from embodied experience, established in the process of the organism’s interaction with the environment. This is to say that even babies who do not have any propositional attitude can still have meaning. Merleau-Ponty posits on this backdrop:

The link between the word and its living meaning is not an external link of association, the meaning inhabits the word, and language ‘is not an external accompaniment to intellectual processes.’ We are therefore led to recognize a gestural or existential significance in speech, as we have already said. Language certainly has an inner content, but this is not self-subsistent and self-conscious thought. What then does language express, if it does not express thought? It presents or rather it is the subject’s taking up of a position in the world of his meaning.

Some cues can be gleaned from this statement to engage the tantric understanding of meaning, particularly in the context of gestures. The first is a confrontation with the way meaning has been understood by the analytic philosophers, and this liberates meaning and even experience from being cobbled to propositions. What language represents, in this paradigm, is something propositional, and concepts as well as experience are semantically structured. Consequently, infants are bereft of experiences so long as they are incapable of their own language. Looking for a meaning of mantras, maṇḍalas, or gestures would be pointless if we consider meaning only in propositional terms, because in that case, only sentences would be meaningful, and even that is due to their capacity to express propositions. Meaning, in this account, has no intrinsic relation to the human body. An enactive phenomenological reading grounds meaning to human interaction within an environment. Meaning, in this account, emerges in a “bottoms-up” process through interaction, and it is embodied. In other words, meaning emerges from basic human interactions with the environment and it is gradually evolving. This approach makes possible a dialogue with tantric epistemology where word and meaning become manifest and externalized from their primordial integral ground. They are therefore interwoven and interlinked, rather than vertically split from their origins. This is why when we display gestures, we don’t just indicate something but we also reveal ourselves: the means of suggesting something is at the same time an entity that is revealed. Reading gestures from the perspective of non-dual tantric philosophy thus offers an alternative to the chasm between the body and mind, while also engaging feelings and emotions in the discourse of meaning. Furthermore, this buttresses the argument that rather than merely representing already experienced meaning, “language presents and enacts meaning.” This helps to establish that gestures are a model for us to theorize meaning.

Furthermore, studying gestures is not about categorizing them. We can group them and call them gestures, we can group them either as secular or ritual gestures, as simple or complex gestures, or we can follow

McNeill’s (

1996) hierarchy of gestures as emphasis, for complementing verbal communication, or those displayed to express emotions. Or we can create new categories altogether. In all accounts, ritual gestures are an extension of everyday gestures and complex tantric gestures integrate different ritual mimes. In all accounts, our bodily gestures are intentional and this intentionality is not severed from our bodily being in any gestural expression.

Even though embodied phenomenology and tantras emphasize the body in addressing meaning, what embodiment constitutes in these systems is quite different. The material body, the expressed and the visible body, from the tantric paradigm, is an extension of subtle desire, which in turn is an expression of consciousness (

cit). Not that this is all that the body means. The body can metonymically refer to creation or to the cosmos. Even when the desire aspect is brought to the fore,

icchā, the Sanskrit term for which we are using ‘desire,’ a dictionary translation does not just mean ‘desire,’ as it encompasses volition, will, and any fundamental drive. Corporeality, in this account, does not juxtapose but merely extends the mind. Gestures, accompanied by speech, are both expressions of the potencies embedded within consciousness as well as a process for materializing volition. The very intentionality first expressed by means of gestures initiates a platform for the subject to have an interaction with his environment or with other subjects. And the other subjects can merely be fantasy objects. In so doing, tantras assign phonetic value to corporeal limbs, specifically, fingers, so that corporealization remains coextensive to phoneticization. But before engaging tantric philosophy, gestures need to be historically contextualized, and this is where the philosophy of dance comes to the stage. To begin with, basic tantric gestures are primarily derived from dance. Even when complex gestures are added in tantras, dance philosophy remains a primary source used to comprehend the system of gestures. Not just that most tantric deities are in one or another dance posture, they are also displaying dance gestures. Mapping these two systems is not farfetched, as the

Abhinavabhāratī, the most extensive commentary upon the

Nāṭyaśāstra of Bharata (

Shastri 1971), provides all the necessary elements.

To begin with, tantric rituals simulate theatrical performance in many regards, whether the audience is the deity alone (private rituals), or public spectators are involved. In the second case, the priest is either playing a lead role or is mediating between the deity and the audience, creating a dialogical sphere among three parties: the deities, the priest/s, and the audience. The privacy of gestures in this account rests merely on their non-vocality. At the end, the dialogue by means of gesture becomes a powerful tool to animate ritual, giving lifeblood to what is otherwise a mere fantasy, and transforming the experience of the participants. Gestural monologues thus become a dialogue and a trialogue when the ritual space phenomenologically transforms into sacred space, enabling participants to cultivate and transform experience. For this, we need to acknowledge that gestures are a form of language, even when they lack syntax and have no propositions to represent. Displaying gestures in the tantric context is not just about a dialogue with the deity but rather, a process through which the abstract becomes concrete and the non-differentiated consciousness assumes deity forms. Moreover, when participants copy the gestures the deities display, they are also mimicking, and in a sense ‘becoming’ the deity. And in this plane transformed by means of gestural expression, the priest mediates between the deity and the audience. Just as in a drama a character is recognized for the role he plays, the priest is identified with the deity as the ritual drama unfolds. The gestures, however, do not merely display what lies within the belly of the abstract meaning, they also allow subjects to return to the same primordial state. Mudrās in this sense function in the same role as that given to mantras. Displaying gestures, a process of creating meaning or being creatively engaged in the process of generating meaning, transforms otherwise random acts into a seamless series of actions.

Central to theatrics are that gestures initiate a trialogue among the audience, the characters and the actors. It is by employing gestures that the narrative becomes alive and the actor transforms into the character. This is where bhāva in the theatrical sense of emotions as well as their expressions becomes contextual. Moreover, the corporeal symptoms such as tears or trembling become part of bhāva (sāttvika bhāva), making the mimes central to a gestural discourse. It is in the kinesthetic gestures that the body becomes a visible language. Central to Bharata’s analysis of theatrics is rasa, an exotic emotional surge that embodies judgmental and appraised cognitive states. When we include emotional expression within the scope of meaning, displaying gestures becomes integral to both the revelation of the intimate modes of consciousness as well as refined modes of emotional expression. The difference between drama and ritual expression is, whereas the actor remains emotionally indifferent when expressing different emotions, ritual agents embody and transcend the displayed emotion by using a transcendental gaze to subsume violent or agitating emotions under a positive, blissful, and enlightened state of the mind. These gestures therefore do not just to share some propositional states but reveal the very being of the aspirants. One fundamental difference between theatrics and tantric ritual is, the second is mostly performed privately, lacking the audience to evaluate or to savor rasa. Another significant difference is, the ritual agent is not using gestures to merely communicate, but rather to transform external experiences into sublime ones. Rather than affirming his somaticity by means of expressing the self through gestures, the ritual agent is reversing the course of actions to encounter his foundational being, his original desire. The ritualized gesture is not merely a display of the body, as the flesh and blood in this account becomes transformed into a phonic body, with the aspirant installing (nyāsa) phonemes and mantras in his body. The lived body of the aspirant during the ritual is thus enmeshed with speech. The body has thus been transformed into a mantric structure and is felt as both a recipient of gaze and the agent of gestures.

4. Mudrā as Mirroring and Abstraction

In the above section, we discussed that the tantric application of

mudrās resembles the ways gestures are used in dance.

3 But before addressing gestures, it is contextual to engage

piṇḍībandha, group choreography, from the perspective of the Nāṭyaśāstra (NS) of Bharata (see

Shastri 1971). What these group formations convey is not just an object based on the shape expressed in choreography, but is also aesthetic savoring, the surge of wonder combined with a sudden flash of sublime experience. It is not the shape but the surge of wonder that animates the memes through choreography. Keeping this in mind, Abhinava explains that even when mere gestures (

karaṇas) are displayed, group choreography can be delightful for it indicates significant aspects of the corresponding deities.

4 In explaining the choreography of Śivaliṅga, Abhinava explains:

Since there is the primacy of the Lord himself, [he is the one] to be pleased. Therefore, he should be choreographed in the shape of Śhivaliṅga that corresponds to his manifest while non-particularized form, addressed by the term Īśvara.

5

Abhinava explains piṇḍībandha as:

The term “formation” (

piṇḍī) that refers to the configuration on the basis of the seat, corporeal limbs [application, and instruments for such applications] etc. Choreography refers to [forming] a specific shape that is brought to consciousness as a specific image whether it is concrete or abstract like the sky.”

6

To further link dance gestures with tantric ritual gestures, dance is integral to ritual worship in many temples. Even the memes and gestures discussed in NS are derived from the myths and in this regard, can be considered a mimetic reanimation of the myths through rituals. Abhinava explains this nexus along the lines that the deity should be pleased by performing a dance (

nṛtta) that should be accompanied by the corporeal gestures (

aṅga prayoga) that resemble the emotional state, action, vehicle, or weapon of the deity.

7Abhinava explains gestures in terms of ‘image consciousness’ (bimba). This is not about the representation of X in an image that resembles X. On the contrary, it is the retrieval of the original image that reflects (as does a mirror) into the manifold in our everyday experience. Abhinava, therefore, stresses that dance as such is not about mimicking:

Nothing in particular is mimicked by dancing with the assembly of gestures (

recaka) and gesticulations (

aṅgahāra). However, just as prosperity is accomplished by some specific

mantras or by some specific visualizations that indicate specific deities, this is also utilized in the case of singing [or dancing].

8

Abhinava rejects the meaning of gestures in a propositional sense. However, this does not mean that he rejects gestures as having meaning. This problematizes the ways meaning is understood in the dualistic framework. As said above, most of Abhinava’s exegesis of gesture rests on ‘mirroring’ (

pratibimba).

9 He says:

Gesture is of the character of mirroring (

mudrā ca pratibimbātmā) (TA 32.1) (

Shastri 1918).

He explains this statement further:

Mudrā is identified in texts as being that through which the joy [expressed in terms] of the actualization of the essential self-nature by means of the body is bestowed upon itself (TA 32.3).

The metaphor of mirroring serves two purposes here:

(1) rather than something else standing for what is being conveyed, it is directly presented by employing gestures. This helps explain the mimesis of gestures.

(2) Mirroring in Abhinava’s philosophy stands for a gestalt. It relates to an immediate presence of an integral entity, similar to an entire town being reflected in a mirror. It is about the body mirroring the most pristine form of experience, with the mind immanently experiencing its presence, without transcending or being split from the lived body. As it comes to defining the scope of gestures, echoes of Abhinava’s statement can be found in the position of Merlin Donald:

“There are four types of mudrās based on the distinction of the body, hand, speech, and mind.” (TA 32.9cd).

This is to argue that rather than dogmatically exploring meaning based on propositions or rejecting meaning altogether based on a perceived lack thereof, we should reverse our gaze and explore meaning on the basis of how gestures animate rituals and bring about transformed states of experience. On a deeper level, tantras recognize the gesture as a specific mode of experience, and our corporeal positions merely evoke this experience.

What constitutes gesture as a gesture, for Abhinava, is not even about the mimes or some conceptual images. This, for him, is about an unbound expression of the primordial bliss. And based on their ability to capture this experience, he categorizes gestures as abstract (

niṣkala) and concrete (

sakala) (TA 32.4-5) (

Shastri 1918), where the

khecarī gesture falls in the first category and the remaining gestures in the second.

10 One should keep in mind at this juncture that Abhinava is not referring to the specific gesture, also called

khecarī, that is performed by curling the tip of the tong back to the soft palate.

11 His is an inner gesture that is performed through visualization and is actualized through the transformation of consciousness. It is

khecarī, then, that becomes the real image, with other gestures mirroring

khecarī. Abhinava explains this based on the assumption that “it is the very

khecarī that is identified in various forms” (TA 32.6ab) (

Shastri 1918). Gesticulation, in this paradigm, is inherent to consciousness in its first orientation towards objects, even before any non-judgmental stimulation has occurred. The state of

khecarī demonstrates a process of moving inward by situating the mind from the base of the body. By gradually moving upward from the base of the spine to the navel, this gesture is performed by moving upward while being merged with the breath that is retained in the locations of

bindu, nāda, and

brahmarandhra, eventually entering to the higher states of

śakti, vyāpinī, and

samanā, and finally transcending these expressed states and merging in the absolute, identified as Parama Śiva (TA 32.10-11) (

Shastri 1918). Obviously, this is not a gesture in any ordinary sense. But this is where the tantric definition of gesture, that it is of the character of mirroring, comes into play. It is in the

khecarī state that the absolute mirrors itself. And this same concept is reiterated by Abhinava’s student, Kṣemarāja, when he explains

khecarī in terms of [the gesture] “that roams in the sky of consciousness”

12 This is not therefore a gesture of representing the mental or physical world but rather of revealing what lies beneath as the potential for the emergence of the expressed and expressing, sign and its reference. This becomes further clear when Abhinava addresses

trisūla or trident gesture:

Having abandoned the mode of being empty and having harmonized the ‘spoke,’ one presents oneself to mere being, staying as if fluid mixed in fluid.”

13

Abhinava explains the Bhairava gesture in terms of visualizing the entire body as a complex syllable, the mantra of Bhairava (TA 32.530) (

Shastri 1918). According to this system, any mental act becomes a gesture. This becomes further pronounced if we engage other Śākta philosophical texts, such as the

Cidgaganacandrikā (CGC) (

Tirtha 1937). or the

Mahārthamañjarī (MM) of Maheśvarānanda (

Dviveda 1992). Although these texts describe only a few gestures from the Krama system,

14 the examples here suffice to buttress the argument that gestures are used as devices in tantric practice to transform the everyday experience as well as a device to mirror non-dual experience:

“The gesture of

karaṅkiṇī leads one to the empty space of pure consciousness, transcending the twofold body comprised of hands [or motor organs] and internal rays [or the sensory faculties]” (CGC 117) (

Tirtha 1937). Maheśvarānanda defines this gesture as “perfect to dissolve the difference [constituted] by the body and the sensory faculties.”

15The gesture of

krodhinī relates to absorbing the duality extending from

prakṛti to earth. (CGC 118) (

Tirtha 1937). According to Maheśvarānanda, this gesture “brings back the collection of categories starting from earth to

prakṛti to its self-nature with fury characterized as the passion to reabsorb them.”

16The gesture of

bhairavī dissolves duality by means of piercing through the six-fold knots and uncovering pure consciousness (CGC 120) (

Tirtha 1937). Following Maheśvarānanda, the gesture of “

bhairavī has the character of full consciousness with a simultaneous [surge] of the entities that are external and internal.”

17The gesture of

lelihānā absorbs all the

vāsanās that emerge through cognitive and sensory faculties (CGC 121) (

Tirtha 1937). The gesture of

lelihānā, Maheśvarānanda explains, is “eager to absorb all the

vāsanas in the form of the subtle body, etc.”

18Khecarī dissolves the speech expressed in different stages from

parā or the absolute state to

vaikharī or the articulated speech (CGC 122) (

Tirtha 1937). Following Maheśvarānanda, this gesture has “the form identical to self-consciousness that transcends the boundaries of the channel of

suṣumnā, since it dissolves all stimulations in terms of conceptualization, for instance, the signified and the signifier, etc.”

19

While the description of Abhinava and what we can find in CGC of Śrīvatsa (

Tirtha 1937) or MM of Maheśvarānanda (

Dviveda 1992) describe the transformative dimension of gestures, with them harnessing everyday consciousness and transforming them to pure consciousness, these accounts fall short when it comes to engaging what we mean by gestures in everyday life, like the hand or bodily movements used to signal something. What can we glean, though, is even when tantras are using the same gestures from everyday experience or are borrowing gestures from dance and drama, their objective is different, as they are using them as a device to return to the deeper layers of experience. This is vivid in Abhinavagupta’s treatment of

khecarī, which he identifies as the foundational gesture, with the rest of the gestures being its limbs. When it comes to theorizing gestures in a commonsense understanding of the gestures that are displayed, the

Yoginīhṛdaya (YH) (

Kaviraj 1979) is a crucial resource. While located in the tradition of Tripurā and addressing only select gestures from within this tradition, we can utilize the philosophical framework from this text to address any other gestures.

5. Mudrā as the Distillation of Potencies

Viewing gestures in terms of mirroring, the Abhinavaguptian exposition is further articulated in Śākta philosophical texts and amplified in two commentaries upon the

Yoginīhṛdaya (YH), the

Dīpikā of Amṛtānanda (

Kaviraj 1979), and

Setubandha of Bhāskararāya (

Kaviraj 1979). Needless to say, the philosophical paradigm of the text and the commentaries are Abhinavaguptian, and most of these insights gleaned from the commentaries can be traced back to Abhinava’s writings. To begin with, consciousness or

caitanya, in this paradigm, is tripartite, having volition, cognition, and action as its integral aspects. If volition is the core of the being of a subject, the same volition expands as action, with the body is its expression. At the same time, the action is the blossoming of volition and so is the body. Following

Yoginīhṛdaya:The very power of action is called gesture for being one with [the world] and savoring it. (YH I.57). See (

Kaviraj 1979).

This interpretation is based on the etymology of mudrā as mud + drā, where the first or modana refers to the stimulation of the blissful state, whereas the second term, drāvaṇa, relates to being commingled with it (tadekarasībhāvaḥ). Amṛtānanda defines mudrā as:

When the power of reflexivity embodies the volition of manifesting in the form of the world, it becomes the power of action and attains the name

mudrā for savoring the world [the act of which is characterized] in terms of absolute bliss and awareness, where the world is its transformation, as well as for the mingling characterized in terms of being one with it.

20

Tantric epistemology rests on twofold acts of consciousness, actualizing itself in terms of the world and transcending the world’s constituted objectivity by merging with the ego. Amṛtānanda explains

mudrā as consisting of two terms (

modana +

drāvaṇa), with the characteristics of manifesting or expunging the world and commingling with the absolute (YH I.65-66) (

Kaviraj 1979) as mirroring the twofold acts of consciousness. From within this platform, gestures function both as (1) transcending or separating from the non-differentiated state and (2) actualizing singularity or returning to the primordial state, explained in terms of the commingling of two poles of illumination and reflexivity. Accordingly,

mudrā corresponds to the entire epistemic system, the ways that experience reveals itself by manifesting the two poles of subject and object, and returning to its nondifferentiated form.

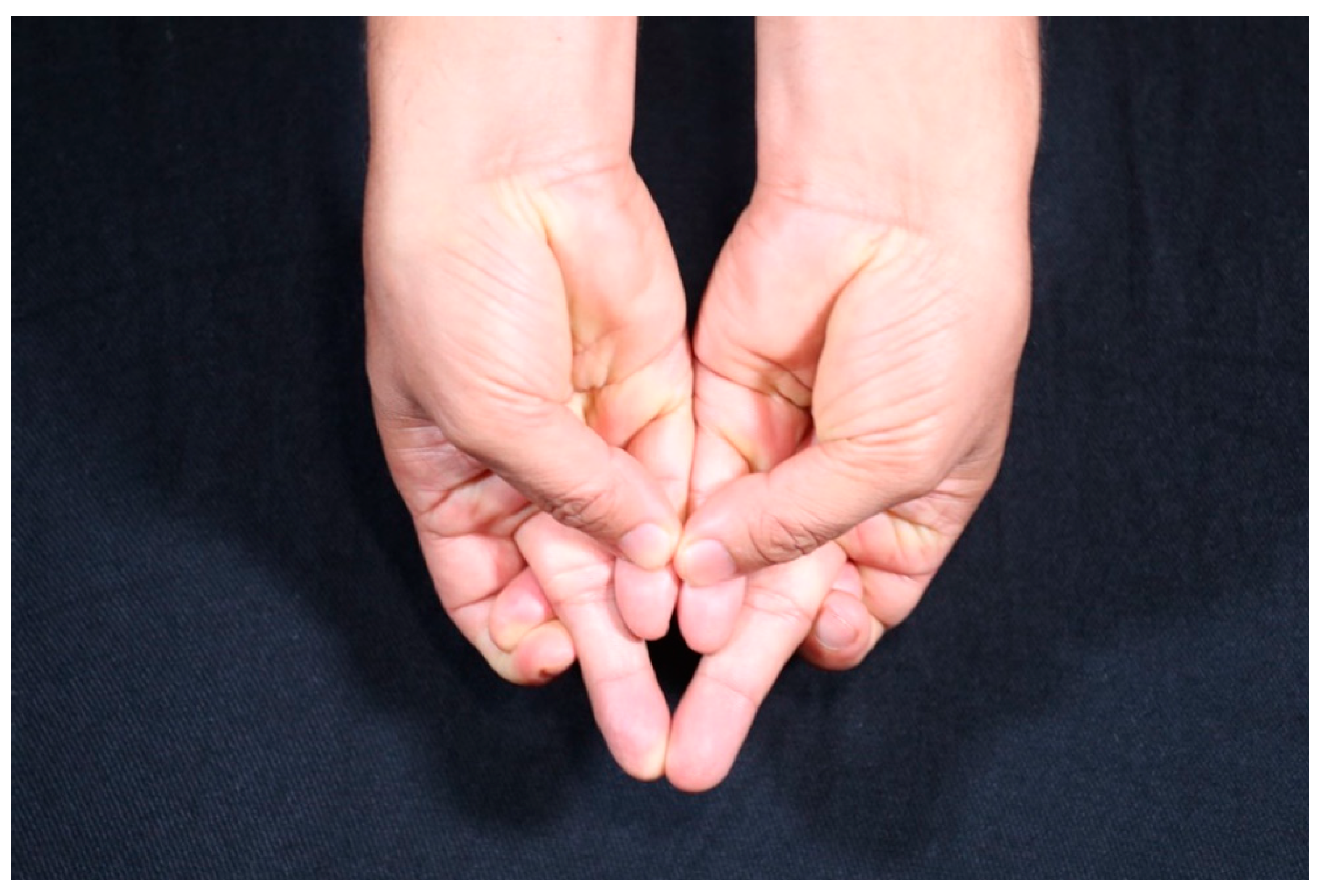

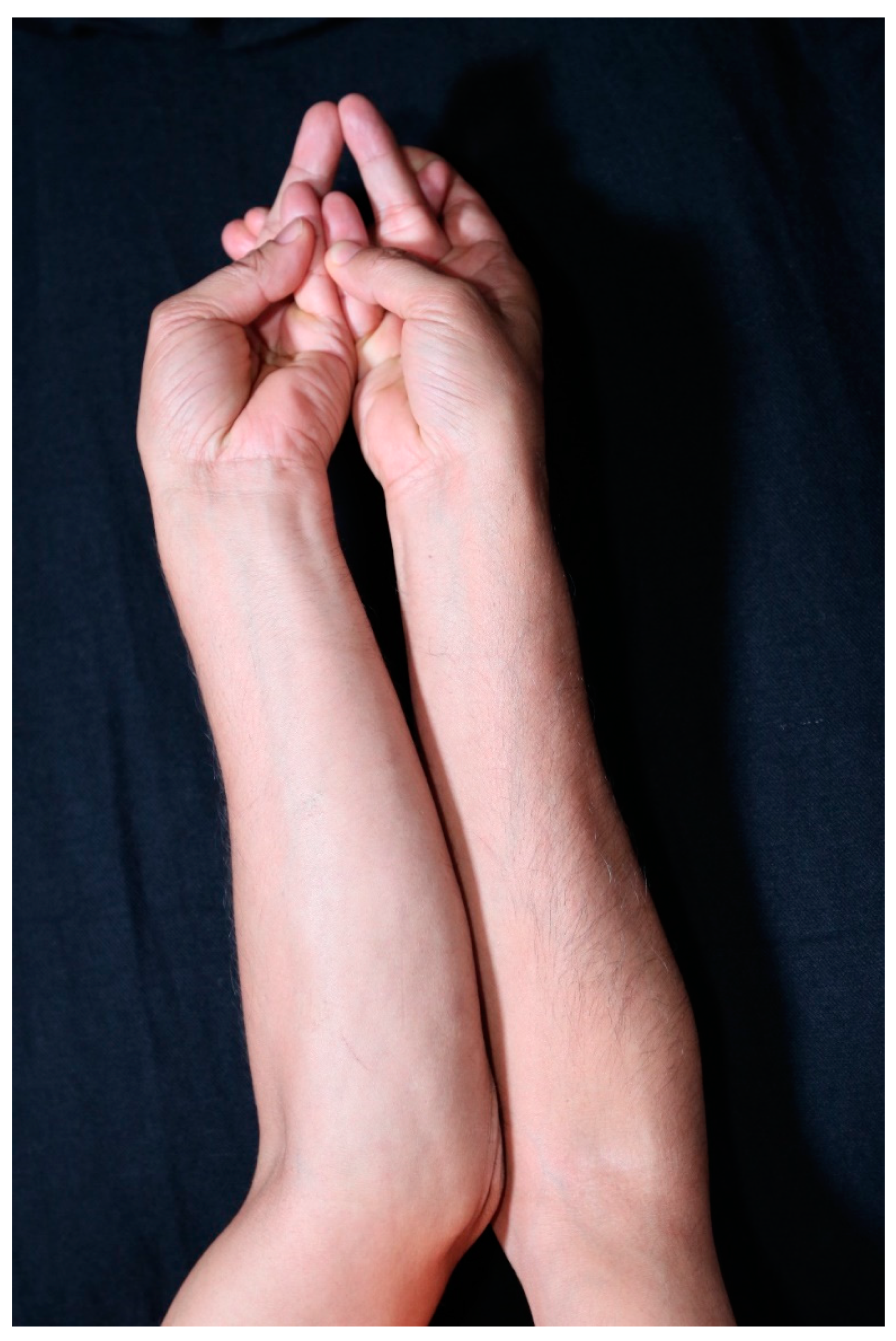

While addressing the seminal concept of

mudrā in the first chapter of the YH (

Kaviraj 1979), Amṛtānanda and Bhāskararāya correlate corporeality with the cosmic potencies, providing the blueprint for addressing all hand gestures. The essence of this discourse is that the body is the distillation of all cosmic energies, explained in terms of Śiva and Śakti, the primordial binary that functions as complementary in giving rise to the world. Śiva, according to this account, is the collection of four energies:

vāmā, jyeṣṭhā, raudrī, and

ambikā, while Śakti is the collection of four different energies:

icchā, jñānā, kriyā, and

śāntā. Additionally, each of these sets constitutes a collective single potency, making ten different energies. Śiva is depicted as luminosity or related to the manifesting aspect of consciousness which is therefore called

prakāśa, and Śakti is identified with reflexivity or

vimarśa. The entire reality is viewed in this paradigm as a fusion of these two polarities. The body, in this account, is a mirror image of the totality and therefore comprised of both these potencies. Accordingly, the right half of the body, the right limbs, such as the right hand, is considered to be Śiva, and the left half of the body and the left hand, Śakti. This imagery takes the androgynous form of Ardhanārīśvara one step closer, making our corporeality as a fusion of two sets of energies that can also be explained in terms of passive and active potencies. Concerning the potencies assigned to each Śiva and Śakti, these are then the potencies located in each of the fingers. In general, all gestures depend on bodily movement and are based on their position—whether the limb that has primacy in the gesture is right or left, the meaning of the gesture differs. For example, when the right palm is placed on top of the left and thumbs touching, the gesture is identified as Bhairava, and if the hand position is reversed, it is identified as Bhairavī. The body, in this account, is the field of energies and an extension of the will that transforms into the potency of action,

kriyā śakti. Accordingly, the body is also an expression of volition. This does not mean that volition as a distinct category is expressed through bodily gestures, but that the very volition is distilled in the form of corporeality and action. Making a gesture, according to this account, first actualizes our bodily being, but even more, this action acknowledges our physicality. Our corporeality, then, is not inertia, pure or otherwise, but rather the blossoming of the potentials embedded within consciousness.

The word

kara means both hands and the rays. By exploiting this polysemy, tantric texts correlate the

maṇḍala of the goddess with her physical appearance: the

marīcis or the rays of the goddess extend in the geometric

maṇḍalas, with the corporeal expression in the form of ten fingers. This polysemy underscores the meaning of gestures in the Śrīvidyā texts by correlating ten primary gestures visualized and worshipped in the ten layers of the

maṇḍala which is not different from the goddess then identified with the fingers of an aspirant. These ten gestures depict a shifting primacy of each of the potencies identified above, described in terms of the polarity of illumination and reflexivity,

prakāśa and

vimarśa. Following the above definition of gesture as essentially mirroring, these gestures express the mental states that mirror both cognitive and emotional states. The commentarial texts give a shifting primacy among different energies and based on their primacy, their significance varies accordingly. For instance, the potency of

vāmā is credited for giving rise to the world and is considered the fundamental force behind differentiation, whereas the potency of

jyeṣṭhā is credited for balance. Accordingly,

jyeṣṭhā harmonizes the flow of all the potencies and gives coherence so that the differentiated world endures in its structured form. What the gestures mean here is just a correlation with different potencies, and in this same framework, gestures resemble

mantras insofar as deciphering their meaning is concerned. YH provides the same format for deciphering gestures and

mantras: find a correlate, relate the entity with other tantric categories, establish the link between specific hand or finger movement, and establish a correlation between the categories and the gesture.

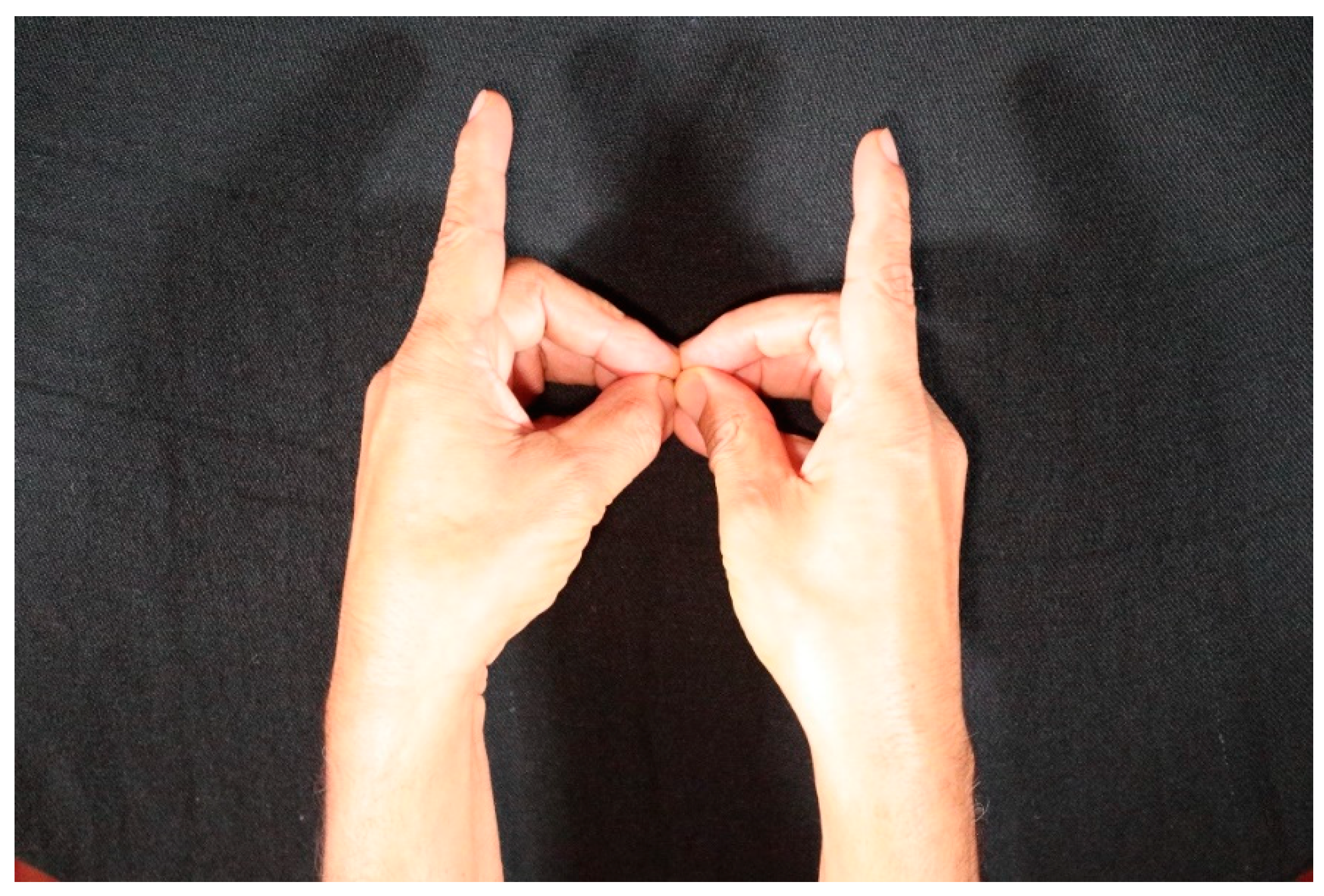

21 The gestures in the tradition of Tripurā are assigned names that anticipate their effects:

sarvākarṣiṇī (

Figure 1), for example, is for hypnotically attracting the subjects, whereas

sarvasaṃkṣobhiṇī (

Figure 2) is intended to generate shock or commotion. While these gestures have some magical applications, they are simultaneously used for liberation as well, and in that context,

saṃkṣobhaṇa stands for the primal agitation of the cosmic forces generating creation and at the same time, this also stands for the surge of bliss, as creation is the outpouring of bliss. Accordingly,

sarvonmādinī (

Figure 3) inflames everyone with love in the magical context, while in the context of liberation, this gesture intoxicates all by giving exposure to the absolute. Along the same lines,

mahāṅkuśā (

Figure 4) gesture refers to goading or bringing under control in the hypnotic sense, while in the context of liberation, it refers to the flow of the highest form of bliss which comes to expression with the fusion of the illuminating and reflexive aspects of consciousness. The point to take home is, these gestures do not exist within a fixed or predetermined sign reference system, and their significance varies according to ritual application. Even though some gestures are widely distributed throughout the Śākta pantheon, for instance,

yonimudrā (

Figure 5) that is displayed in most rituals worshipping the goddess, other gestures are specific to the pantheon of Tripurā. Except for the basic correspondence between the deity’s right and left hands with their correlation with Śiva and Śakti energies, or with the specific phonetic potencies related to the phoneme/

a/and/

h/, the correspondences seem arbitrary.

Gestures are meaningful only when their significance is comprehended in the context of the rituals in which they occur and are deciphered as the prescribed texts relate. For

mudrās do not have independent meaning to be universally derived. And in this regard, tantric gestures are not merely a subset of universal gestures shared across cultures. The gesture of

vidrāviṇī (

Figure 6), for example, designates arousal,

vaśaṅkarī (

Figure 7) aims to keep subjects under control, whereas the gesture

unmādinī (

Figure 3) intends to intoxicate and madden the subjects. The gesture

mahāṅkuśā (

Figure 4), along the same lines, is applied for the hypnotic purpose of keeping subjects under control, goading the subjects to keep them under control. There is nothing to inherently establish these gestures as expressing what is assigned. What is anticipated in this context is beyond a social convention, a tantric convention that is shared only among the initiates.

Deciphering a gesture from one tradition and imposing it on another can be misleading. For instance, the gesture

khecarī (

Figure 8), as depicted in the pantheon of Tripurā, is quite different from the popular

khecarī gesture in the Hatha yoga, Trika, and Krama systems. Some gestures mirror each other and complement meaning. For instance, the gesture

bījamudrā (

Figure 9) complements

yonimudrā (

Figure 5). In the very beginning of the conversation upon gestures,

Yoginīhṛdaya (I:58 and the commentaries thereon) describes

trikhaṇḍā (

Figure 10) as bestowing intimacy with the goddess Tripurā, as this permeates the entire Śrī Cakra. Whether this gesture is all-encompassing or has a more distinctive meaning depends on the way the Śrī Cakra is worshipped, as there are primarily three prominent traditions of worshipping Tripurā, ––Hayagrīva, Ānandabhairava, and Dakṣiṇāmūrti, and even among them, there are internal variations due to differences in

mantras, particularly apparent in the Kādi and Hādi systems. Amṛtānanda defines the gesture

trikhaṇḍā in the following words:

“The consciousness of the character of reflexivity is endowed with three aspects. Ambikā is the collection of the three aspects of Vāmā, Jyeṣṭhā, and Raudrī. And the mentioning of Ambika also elliptically implies [the aspect of]

Śāntā. The meaning is that [the pure consciousness] attains the form of

Śāntā that is of the character of the fusion of the potencies of volition, cognition, and action. [By the statement] ‘adopting the form of

trikhaṇḍā,’ what is intended is that [the very pure consciousness] acquires the gesture of

trikhaṇḍā having three sections wherein the fingers of the right hand identified as Vāmā etc. that are of the aspects of illumination and the fingers of the left hand, identified as volition etc. are of the aspects of reflexivity, and of the character of bondage, being the union of these two [potencies]. [She] always grants intimacy. She is therefore the one providing intimacy with the goddess Tripurā, the luminous being of consciousness. Since this is the foremost of the king of all the wheels [of the goddess] or [the best] of all the

yantras for worship, and is so identified as encompassing the king of the wheels [of the goddess].”

22

6. Central Mudrās in the Practice of Tripurā

The following images of mudras are central to the worship of Tripurasundarī. In the discussion above, these images are discussed thematically rather than in the sequence in which they occur in the ritual, as the objective here is to address gestural meaning.

Bhāskararāya explains that the gestures demonstrated above are the manifestation of the deity at the center, Tripurā.

23 That is, just as our corporeality is an expression of the energies inherent to the absolute, metaphorically explained in terms of the pair of luminosity and reflexivity, so also are the gestures an expression of the absolute or the mirroring of the totality. In other words, just as the

mantras are considered to be an expression of the deity, so also are the gestures. To recite the specific

mantras or to display the specific gestures is therefore considered to make the supplicant an embodiment of the deity. If a specific deity is a mirroring of a specific mode of being, an expression of consciousness and bliss expressed in a certain form, embodiment through displaying the corresponding gesture stands for mirroring the same experience. In other words, when we display certain gestures, we have already entered the paradigm of the goddess, as the very gestures are the divine emanations encircling the

maṇḍala while at the same time the mechanism for the transformation of our somatic experience into the liberating ones. If the body is the mirror image of the cosmos, individuals retain the same potentials in kind and the gestures make it possible to actualize this identity. The same cosmic forces can be traced in fragmented form in the individualized states, and these same forces are invoked in the

maṇḍalas. What can we glean from this internal account of the way gestures are explained is that meaning is fluid and determined in the context of performance; what is articulated has a direct constructive effect on the subject and his environment; and gestures and words express the same unfolding of the absolute.

Gestures are integral to rituals and are an expression of the potency of action since corporeality represents the potency of action. Generally speaking, performative rituals rely on a dichotomy between the worshipper and the worshipped. Ritual acts are grounded on differentiation where the agent actively engages with objects and uses them accordingly. This understanding is reversed in the non-dual tantric paradigm, where the ritual act becomes an expression of the fusion of agencies: it is in the act of ritual that the deity being worshipped melds with the subject worshipping her. While the image of a warrior, the horse he is riding, and his sword combine to show a perfect warrior, it is not a recognition of difference but a seamless unity or harmony that makes a perfect warrior. Likewise, the articulation of mantras, displaying gestures, and the acts of visualization are what bring the ritual acts to life. Gestures in this sense are the devices that bridge existing polarities. Maheśvarānanda’s statement underscores this seamless harmony in displaying gestures:

The state in which the establishment of the glory, characterized as the surge of higher and higher grounds corresponding to the splendor [itself] or the expression which [in other terms] is the flash of having the recognition as such of the bliss of the Supreme Lord––the luminous being who is characterized as the mingling of both the modes (

svabhāva) of being worshipped and being a worshipper as He is of the essence of the freedom in various forms of sporting or being victorious––resting on His nature, is directly experienced or apprehended without any doubt, that very state is recognized as

karaṅkiṇī or known [in other

āmnāyas] as

saṅkṣobhiṇī, etc.

24

From the above depiction, not only do gestures mirror inner mental states they also stimulate intended state when being displayed. It is in performing the specific gestures that Maheśvarānanda assigns the direct experience of the surge of bliss to the resting of the self in its primordial nature. These gestures are there to gradually cultivate the refined modes of consciousness, and as a consequence, the aspirant is thought to be able to experience oneness with the deity that he is worshipping. When we read the above passage in light of the five gestures that he elaborates upon, we also notice a successive progression towards the absolute, moving the mind from the external forms, corporeality, categories, or speech, to the inner modes of bliss and awareness.

In essence, gestures do not signify but express. As they convey the innermost modes of being, the blissful states that remain obscured in everyday experience that is determined by differentiation, these gestures also create something anew. Maheśvarānanda, therefore, etymologizes gesture as “mudaṃ rāti” as “that which bestows bliss.” The gestures that can be displayed, the corporeal gestures, are merely to evoke the specific states of the mind and are meant to be the conduit for the mind that is oriented outwards to turn its gaze inward, access its pristine modes, and eventually dissolve in the singularity of pure consciousness. Maheśvarānanda says that, keeping this in mind,

The extra-sensory experience of the character of the act of recognition is synonymous to the sudden flash (

camatkāra) of resting on one’s essential nature that is of the status of situating in a calm ocean by transcending the [corporeal] compression characterized by bending and curving the hands and feet, and for this very reason pulsating with all the external joys that are similar to the foam or bubble or drops, is called gesture by the definition that it bestows bliss, as it is the foundation for the surge and dissolution of other gestures such as

karaṅkiṇī.

25

According to this account, gestures uncover the primal modes of experience and facilitate access to the states of consciousness that are otherwise not readily attainable. Consciousness in this paradigm is defined as having the intrinsic nature of an impetus towards differentiation. Tantric philosophers such as Maheśvarāananda or Amṛtānanda are suggesting that the internalized forms of gesture assist in altering this trajectory. Returning the gaze to self-experience, accordingly, is an active bodily process, with gestures mediating the transformation. While what the gesture in its true sense reveals is the very awareness in its pristine form, even the corporeal gestures are identified for their ability to uncover the innermost blissful state. In essence, every external gesture evokes the internal, and the internal gesture is not explained in terms of sign-reference relationship but is recognized as a device for an instantaneous experience of the inner modes of the self.