Abstract

In April 2014, a new Church of England diocese was instituted, combining three smaller dioceses covering a large area of Yorkshire. To mark the development of this new ‘mega-diocese’, a group of motorcycling vicars began to meet regularly and undertake ‘rides out’ across the diocese and further afield. This paper explores research undertaken with these motorbiking priests and their companions. The study followed an ethnographic approach, as the researcher is an ordained clergyperson embedded within the ‘Biker Revs’ community, though not a biker. The research comprised semi-structured interviews and informal conversations with the Biker Revs over several years. This research investigates the Biker Revs’ experiences and motivations for undertaking pilgrimages together, by motorbike. On these performative journeys, the Biker Revs initially visited sacred sites across the United Kingdom. As a basis for comparison, this paper utilizes Michalowski and Dubisch’s 2001 iconic ethnographic research on an American motorcycle pilgrimage, to analyze the group’s activities. The ordained bikers identified the group as a safe space for clergy, outside their parishes, whilst their spouses recognized the benefits of spending time with ‘others like me who understand the pressures of clergy life’. For some participants these pilgrimages provide a religious retreat, as together, they explore sacred landscapes and learn the stories of their holy destinations.

Keywords:

pilgrimage; sacred sites; motorbiking; biker; Church of England; retreat; eventization of faith 1. Introduction

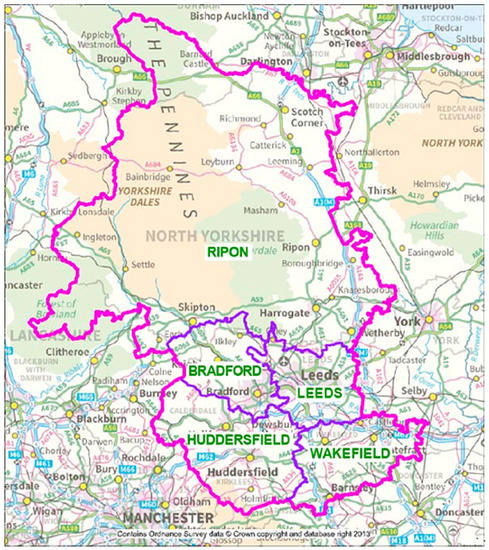

This research considers the impacts of a decision by two vicars to respond to an historic change to their local diocese. As background, in April 2014, a unique moment for the Church of England witnessed the merger of three existing Yorkshire dioceses into one, creating a new mega-diocese. Figure 1 below shows a map of this new diocese (Leeds Diocese 2014). The response from these two vicars to the creation of the new entity, was to form a group of motorbike enthusiasts, open to clergy and lay people across the wider geographical area. The group became known as the ‘Biker Revs’, with the purpose of bringing together lay and ordained people from across the new diocese in a shared activity—motorcycling. Mainly comprising vicars and their spouses, the Biker Revs have become a regular sight in the region, and beyond. Originally named the Diocese of West Yorkshire and the Dales, two years later, it became the Diocese of Leeds (Bogle 2016).

Figure 1.

Map of the new Diocese of West Yorkshire and the Dales (2014) (Leeds Diocese 2014).

On their first ‘ride out’, in October 2013, the group visited the cathedrals of the three dioceses that would soon be merged—Ripon, Bradford, and Wakefield. In addition to an average of four local day rides out each year, the group has also undertaken five longer motorbike pilgrimages (each five to six days in length). For their first pilgrimage, in April 2015, the Biker Revs visited the island of Iona, off the coast of western Scotland, widely regarded as the cradle of Christianity in the British Isles. In June 2016, for their second journey, the group travelled to Ballycastle in Northern Ireland, home of the peace and reconciliation Corrymeela Community (n.d.). In June 2017, continuing the theme of visiting places where the national saints of the United Kingdom are remembered, the Biker Revs rode to St David’s in Wales.

In October 2017 a select group ventured further afield, undertaking the Santiago de Compostela pilgrimage route by motorbike. In June 2019, they spent a week biking around the North Yorkshire coast, visiting Holy Island and the Lindisfarne Priory. In 2020 the group’s plans were curtailed by COVID-19 restrictions. The map of the United Kingdom in Figure 2 below shows the longer trips undertaken by the Biker Revs. In the Church of England, all clergy, whether paid or unpaid, full-time or part-time, are expected to go on ‘retreat’ for a week every year. In addition, after seven to ten years following ordination, clergy may apply for a three-month sabbatical, and many include an extended time for reflection on pilgrimage to a sacred destination. The originality of this research lies in its analysis of pilgrimages undertaken by a group of clergy by motorbike.

Figure 2.

Map of the United Kingdom showing Biker Revs trips (adapted from Google Maps).

The specific goal for the formation of the group was to build relationships between people from (clergy and non-clergy) motorbike enthusiasts from across the new diocese. The approach the group took to achieve this aim was to arrange day rides out and longer five- or six-day pilgrimages to sacred places, initially in the UK. This research investigates the motivations for these pilgrimages (a conventional form of religious tourism) of the Yorkshire Biker Revs as they visit sacred sites, and analyzes the group’s activities and experiences. It takes as a theoretical focus, the iconic ethnographic research undertaken by Michalowski and Dubisch (2001) on the motorbike pilgrimage route that reconnects American ex-servicemen with their Vietnam War historical roots, crossing the United States from California to Washington DC. It incorporates reflections on motorcycle pilgrimage by Dubisch (2004, 2008), and Dubisch and Winkelman (2005).

This paper also aims to contribute to an understanding of the concept of the eventization of faith, which has emerged from research by Pfadenhauer (2010) on the Roman Catholic World Youth Day. Pfadenhauer’s analysis identified connections between the developing popularity of secular music festivals, that had been adapted by the church as a form of marketing to reach young people. Further research has identified that this is a more complex concept that transcends marketing and impacts on a wide range of church-related activities. The Biker Revs have joined in the proliferation of events-based leisure activities through their organization of regular day rides out and longer pilgrimage trips, as they build relationships by visiting sacred places together. In previous research, Dowson et al. (2019) suggest that pilgrimage is a contributing activity to the eventization of faith, and consider the appropriateness of the use of church buildings for non-sacred events and activities (such as riding motorcycles into a cathedral, as shown in Figure 3, below).

Figure 3.

Biker Revs on their first ‘ride out’, inside Bradford Cathedral, October 2013. (Photograph Credit: Rev Stephen Kelly).

2. Literature Review

This section considers key areas of academic literature as it relates to my research questions, on the purpose and impacts of the group’s engagement with pilgrimage and motorcycling, both as a leisure activity and as a chosen mode of travel. The literature is applied to the context of the research subjects, and to the activities of these Biker Revs as they perform their pilgrimage journeys. Figure 3 below shows three of the Biker Revs on their motorcycles in the sacred space of Bradford Cathedral on their first ride out in October 2013.

2.1. Pilgrimage

The ancient concept of pilgrimage is found across major world religions; it focuses on a journey made towards reaching a sacred goal (Leppäkari and Griffin 2017). Historically, the journey is physical, often made through dangerous territory and strange lands, but has spiritual and other internal rewards. Pilgrimages vary even in their historical religious origins and purposes. Norman (2011) asserts the importance of the physical journey in addition to the arrival at a sacred destination. The characteristics and purposes of the pilgrimage journey are relevant (Cassar and Munro 2016), along with the eventual pilgrimage destination (Scriven 2014), and the emergence of the feeling of belonging and shared identity (Merkel 2015), or ‘communitas’ (Turner and Turner 1978), through shared activities. However, visiting pilgrimage sites such as war memorials (Shackley 2001), or places that contain sacred objects (du Cros and McKercher 2015), extends the diversity of what is conceived of as sacred. In the same way, the mode of travel has diversified, and this is reflected in Michalowski and Dubisch’s (2001) work on the motorbiking pilgrimage across the USA.

2.1.1. Pilgrim–Tourist

Theoretical explorations of the pilgrimage experience and the pilgrim journey inform a critical view of the pilgrim-tourist dichotomy, explored in depth by Cassar and Munro (2016). To what extent is a pilgrim also a tourist, and to what extent does the tourist become a pilgrim (Fladmark 1998; Raj and Griffin 2015) have been long-discussed. Sturm (2015, p. 237) addresses this type of relationship in a different context (cricket), concluding that there is a ‘fluidity’ between the roles of cricket spectator and tourist. This idea is applied to the pilgrimages of motorbiking vicars. Similarly, Dowson et al. (2019) analyze the role changes experienced by academics observing a tourist performance of the whirling dervishes in Konya, Turkey during a religious tourism conference. In this instance, the participants found themselves at different points on a pilgrim–tourist continuum. However, many observed the event as academics, and some also as worshipers. This positioning was found to vary at different points in the event (Dowson et al. 2019, pp. 3–4).

2.1.2. The Journey and the Destination—Motivations

Many pilgrims begin their journeys as individuals, setting out for a distant destination. However, as they journey, they meet others and bond together. Their motivations may be with different purposes in mind, including devotion, a search for miracles, ritual, and quest (Norman 2011; Kujawa 2017). Fladmark’s definition of spiritual motivations for pilgrimage is relevant: “the innate desire of the human heart to visit places made holy by the birth, life or death of a god or prophet” (Fladmark 1998, p. 45). The Biker Revs’ longer rides are such pilgrimages, connecting with British patron saints. Kaell argues that there is a specific Western perspective to pilgrimage, aiming to achieve “something ‘good’ in the lives of those who undertake it” (Kaell 2016, p. 6). The search for authentic, life-changing experiences through the pilgrimage journey (Abad-Galzacorta and Guereño-Omil 2016) also applies to the Biker Revs. There is growing popularity of pilgrimage by travelling a specific route, from the Camino de Santiago that originated in the late Middle Ages, to the Ignatian Way, a newly founded 21st century pilgrimage route (Abad-Galzacorta and Guereño-Omil 2016). As the Run for the Wall (Dubisch 2008) provides a transformational space for Vietnam war veterans, so the Biker Revs’ pilgrimages engage participants in opportunities for spiritual and physical renewal.

Michalowski and Dubisch summarise pilgrimage as combining “a ritual journey with seriousness of purpose, ending in the arrival at a sacred goal” (Michalowski and Dubisch 2001, p. 15). However, there is a symbolic role within the motorcycle journey, expressed as uniting biker pilgrims: “riding together … joins the participants … in a common brotherhood of the road” (ibid). At the same time, bikers are set apart from those other travelers who use “more ordinary (and more comfortable) means” of transport (ibid). The Biker Revs experience forms of this strong connection, as they lead or follow within the group. On occasional road traffic accidents involving Biker Revs on trips and rides out, the care shown is evident in the efforts made to ensure everyone is watched over during the journey. Further evidence for this caring element in the Biker Revs’ motivations is found in a social media post by one of the founders. His rationale for the group’s formation came from Richard Baxter, a 17th-century Puritan minister in the Church of England:

One of my pastoral and priestly heroes: ‘Ministers have need of one another and must improve the gifts of God in one another; and the self-sufficient are the most deficient, and commonly proud and empty.’ A good enough reason for a biker group!

2.1.3. Liminality

The concept of liminality is relevant to this study in a number of ways: liminality of physical space, liminality of space-time, the liminal experience of traveler, tourist and pilgrim, and the liminality of being both clergy and biker. Turner and Turner (1978) researched the liminal experience of travelers concluding that they experience a liminal space simply by travelling away from their daily lives. Norman (2011) highlights this contrast with everyday life, considering that tourism also provides such an experience. For religious or spiritual tourism, Norman (2011) suggests that this liminal element is explicitly different from the everyday, whether differences are spiritual, religious, or not. However, Norman (2011) concludes that pilgrimage offers availability and access to different kinds of spiritual and religious experiences compared to those at home. Dubisch observes that a pilgrimage undertaken by motorbike “distinguishes their journey from other mundane trips, and particularly from purely recreational motorcycle rides” (Dubisch 2004, p. 114). Whilst most Biker Revs are ‘recreational’ hobbyists, some rely on their bikes for day-to-day transport.

Motorbiking provides a space-time for bikers; as they travel, they are isolated from other riders, yet still connected to each other (Michalowski and Dubisch 2001). Even riding as a biker with a pillion passenger, the two are separated throughout the journey. Amongst the Biker Revs, several couples have an in-helmet intercom system to enable them to talk whilst riding. For one clergy couple, this was a short-term intervention. Both introverts, they valued the time and space to reflect during riding time, as they left “ordinary life” (Michalowski and Dubisch 2001, p. 166) behind. This is frequently viewed as retreat time, in silent contemplation of the landscapes they pass through (Norman 2011). Travel time removes the traveler from the usual distractions of life; traveling by motorbike more so (Dubisch 2004; Norman 2011; Scriven 2014). Motorbiking offers the opportunity for reflection and self-transformation (Michalowski and Dubisch 2001, p. 166), a vital time to see possibilities for change. Traveling by motorbike is not the most comfortable experience, especially in poor weather. Sitting in the same position for hours on end causes physical discomfort, requires perseverance, and regular stops. Little surprise then, that bikers inhabit a space on the edge, choosing physical hardship as well as thrills for their mode of transport, as they visit sacred sites, “spatially liminal locations separated from the normal world by virtue of their sacrality” (Norman 2011, p. 95). Whilst on rides out or on pilgrimage, the Biker Revs become a “transient, yet liminally-bonded community” (Norman 2011, p. 31), as they seek to reconnect with the other and with each other (Michalowski and Dubisch 2001). This liminal state is characterized by what Turner and Turner name “communitas” (Turner and Turner 1978), as the bikers develop a sense of belonging to one another during their time together.

2.1.4. Communitas

Turner and Turner (1978) introduced the new concept of communitas through their anthropological studies. As people engage in liminal activities together, a social relationship emerges, outside of normal hierarchies and bonds (Moore 2001). The social aspects of a ride out can lead to communitas—but a longer motorcycling pilgrimage is more likely to nurture this outcome. Esposito (2010) considers etymological differences between the Latin ‘communitas’—an expression of cooperative obligation in common with others–and the Greek ‘koinonia’ within its theological context—of joining together through participation in the Eucharist. The Biker Revs develop communitas on their sacred journeys, and they experience koinonia as they share in the sacred ritual of Holy Communion, whether on a beach on Iona or in Northern Ireland.

Michalowski and Dubisch note the impact of communitas on veterans as they bike their way from West to East across the United States, as “the ordinary divisions and distinctions of society are dissolved, at least for a time, and participants enter a state of equality and share experience” (Michalowski and Dubisch 2001, p. 166). For Biker Revs, distinctions between clergy and lay bikers fall away when riding out together; archdeacons ride alongside newly ordained curates, vicars accompany lay people.

2.2. Places of Pilgrimage

The Biker Revs decided to visit sacred places representing the patron saints of the four nations within the British Isles. These trips express the unity (Power 2006) of the nations, symbolizing for the group’s founders, the unity of the new mega-diocese of Leeds. Such spiritual destinations offer a sense of place, providing a “spiritual homeland” (Power 2006, p. 35) for pilgrims, and a sense of belonging. The Biker Revs also sought this sense of belonging, searching for a feeling of home in the new diocese and of belonging to each other, and a spiritual connection to their choices of sacred destinations. These pilgrimage destinations are all places of worship (Power 2006, p. 41), an important factor for clergy, enabling them to worship together as equal members of a congregation, in contrast to their everyday calling as leaders in the church. The destinations chosen by the Biker Revs are predominantly centers for Celtic spirituality, “thin places” (Béres 2012; Power 2006) connecting heaven and earth, the spiritual realm and the earthly realm, providing opportunities to connect with the divine.

Iona is known as the “cradle of Christianity” in Scotland but was equally the wellspring of Christian worship in the wider British Isles. Visitors and pilgrims to the island can stay in this monastic community, with shared meals and time to relax together, as experienced by the Biker Revs.

The Holy Island of Lindisfarne in Northumbria is recognized as the “cradle of English Christianity” (Symes 2009, p. 10), and resulted in the production of the most beautiful artwork treasures such as the Lindisfarne Gospels, and the promulgation of worship in the vernacular (English), rather than Latin (Symes 2009).

Power notes that “Corrymeela does not have the same ancient sense of place that make Iona and Holy Island… significant” (Power 2006, p. 47). However, it is a place of Christian forgiveness and reconciliation, established in the 1960s to promote theological and political values to emulate the Iona community, in response to the political and social context of Northern Ireland (Collins 2000; Power 2006).

For their trip to Wales, the Biker Revs stayed in the countryside, visiting St David’s Cathedral on a day ride out (Power 2006). Accommodation and catering arrangements for this trip differed from previous tours, as the group provided their own catering. The photograph in Figure 4 below shows members of the group relaxing outside in after-dinner sunshine.

Figure 4.

Biker Revs on their Welsh pilgrimage, June 2017. (Photograph Credit: Matthew Dowson).

Meal by meal, the group bonded on their Welsh trip in new ways, forming deeper relationships in the kitchen as they prepared food together. As with all pilgrimages, the Biker Revs return “to the quotidien life” (Scriven 2014, p. 252), renewed after completing acts of devotion in sacred places.

2.3. Motorcycle Research

The International Journal of Motorcycle Studies considers cultural aspects of motorcycling, from experiential perspectives, technical aspects and the use of motorcycles in film and literature. Relevant publications outline the range of motorcycle writing and research (Alford and Ferriss 2006) providing autoethnographic studies. e.g., the social identity of a military motorcycle club (Wiggen 2019). Literature on Christian motorbikers has several perspectives: retelling personal experiences (Stillman 2018), and exploring stories of Christian motorcyclers (Remsberg 2000; The 59 Club n.d.). However, of more interest is the work of American researchers, Michalowski and Dubisch (2001), on the pilgrimage aspects of a longer ride supplemented by Dubisch’s other works (Dubisch 2004, 2008). The underlying assumptions of Michalowski and Dubisch’s work support their search for meaning in the aftermath of the Vietnam War, and the roles played by the US military in that conflict, that subsequently impacted on so many veterans’ mental and physical wellbeing (Michalowski and Dubisch 2001, p. x).

The concept of motorcycle pilgrims is well-documented by Michalowski and Dubisch (2001), through their participation in an annual pilgrimage by motorbikers, ‘Run for the Wall’ which has taken place since 1989. This journey begins in California and draws in war veteran riders along the way to the memorial wall commemorating American soldiers who lost their lives in the Vietnam War. A compellingly told narrative, the account explores the motivations and emotional experiences of those seeking healing, making meaning and reconstructing community memory along the route and at the destination, which for many has become a sacred place.

According to Michalowski and Dubisch, the reasons for undertaking pilgrimage include the acquisition of “spiritual benefits”, seeking “healing for physical or psychological problems”, an opportunity “to honour the holy places of their religious traditions”, “to establish or affirm their own religious, cultural or personal identity”, and “to express political or social protest” (Michalowski and Dubisch 2001, p. 15). Each day begins with religious rituals, including shared prayers, led by accompanying chaplains. Every stop, during the day or at night, finds local hosts providing free hospitality—accommodation, food, and refreshments. New “deep and sustaining bonds of friendship” (Michalowski and Dubisch 2001, p. 19) are made, and existing attachments renewed.

Michalowski and Dubisch emphasize the differences between this trip and other bike rides out, asserting that they were “not on a pleasure jaunt … we were pilgrims on a mission” (Michalowski and Dubisch 2001, p. 15). Some of the characteristics of biking pilgrimage match those of pilgrimage through other means, as Michalowski and Dubisch observe that “motorcycle pilgrimages are more than rides … journeys that change the traveler” (Michalowski and Dubisch 2001, p. 64). Whilst this is ostensibly a secular pilgrimage, it clearly incorporates Christian rituals and other forms of spirituality.

3. Method and Limitations

This paper unashamedly espouses the ethnographic approach, which is common to academic research on churches and their congregations (Scharen 2012; Ward 2012). Ward asserts that “methods of research are never neutral” (Ward 2012, p. 9), and I concur with this view. As a researcher, I am situated within the area that I study. Like Ward (2012), this influences not only the topics that I research, but also what I observe, what I take note of, and what I write. There are benefits to this qualitative ethnographic approach that enable the voice of the research to emerge. In some quarters of the academy, there are still those who question the validity of such research approaches and claim their own objectivity. However, increasingly, in a range of fields, strong considerations of emerging perspectives of authenticity and credibility resist and replace the dominant traditional (quantitative) research discourse of validity and reliability (Frisk and Östersjö 2013).

Of the main methods of qualitative research, this ethnographic study has involved observation (Ward 2012, p. 8) of the group of Biker Revs as it has developed over a period of seven years. The observation method is fundamental to research in the fields of sociology and anthropology, and is the “chosen method to understand another culture” (Silverman 2019, p. 42). Research into church communities also relies on observational studies to “develop a picture of the lived experience” (Ward 2012, p. 8). This study has been based around opportunities to observe a community from inception, as the group of motorbiking vicars has developed strong relational bonds through their pilgrimages and day rides out. As the spouse of one of the initial members, I have been able to connect with the group, even though I do not ride with them. As a result of receiving an annual retreat grant from the diocese, I was able to accompany them on two pilgrimages (to meet them at the destination), to Northern Ireland in 2016, and the following year, to Wales.

The photograph in Figure 5 below shows the Biker Revs group outside the interfaith peace-making Corrymeela Community that hosted their stay in Northern Ireland.

Figure 5.

Biker Revs on Pilgrimage, Corrymeela Community, Northern Ireland, June 2016. (Photograph Credit: Stephen Kelly).

It was on the trip to Northern Ireland in 2016 that I first experienced the sense of belonging to this community, as we shared meals and worshipped together, and explored the area nearby (although my exploration was mostly on foot, as I am not a biker).

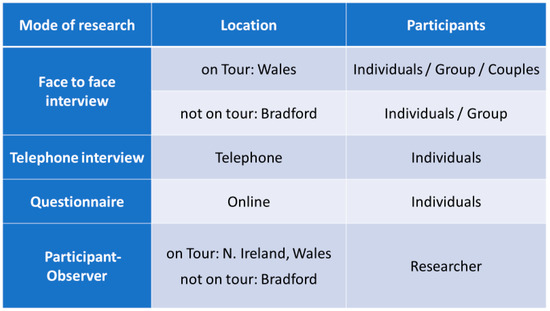

This trip also inspired my research, and the following year, having obtained ethical approval for my research, I accompanied the group to Wales. We stayed in self-catering accommodation, where the kitchen became the hub of all interaction, as together, we prepared meals. Silverman (2019) highlights the important role of interviews in qualitative research, in which the responses to open-ended questions can be coded to identify themes. Silverman (2019) and Ward (2012) argue that authenticity is key to qualitative research interviews, rather than the number of interviews that are conducted. The primary research interviews with the Biker Revs explored motivations, views, and experiences in building a sense of kinship and passion for a shared pursuit, that perhaps differentiates bikers from other leisure activities. Figure 6 below summarizes details of the research modes, locations, and participants.

Figure 6.

Details of research mode, location and participants.

The interviews were recorded and later transcribed, undertaken in the Welsh countryside, sitting in the lounge or relaxing outside. Some interviews took place in small groups, some with couples together, and some with individuals. Prior to and after the trip, I also undertook interviews by phone to include other members of the group who had not been able to participate in the five-day pilgrimage.

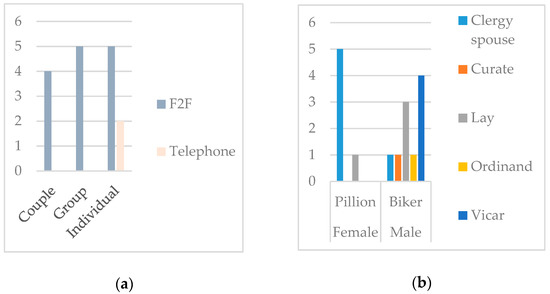

Figure 7 below displays the demographic details of interviewees. Figure 7a shows the split between face to face and telephone interviews, as well as how the interviews were undertaken (individual/couple/group). Figure 7b depicts the numerical gender, seating and role differences of those interviewed (the numbered axis represents the totals of individuals in each grouping).

Figure 7.

Demographic research details. (a) modes and types of interviews, (b) gender, seating and role differences.

On the Wales pilgrimage, it happened that all the bikers were male, and all the pillion riders were female. However, although this is a typical biker pattern, there are now more female bikers in the group (who are all clergy) and on the Northern Ireland trip there was one female biker (who was on honeymoon, having married the weekend prior to the trip). Within the research analysis, there emerge questions of whether there are differences between the views of clergy and non-clergy; stipendiary (full-time paid clergy) and non-stipendiary ordained (unpaid ‘volunteer’ clergy) participants; the roles of vicars, curates, ordinands, clergy spouses, and lay people; and bikers for whom their bike is their primary mode of transport as opposed to those for whom biking is a hobby—even if the hobbyists have three or more motorbikes in their garage.

My research includes personal reflections on accompanying the Biker Revs (as a non-biker priest, whose non-Rev husband is one of the founder members of the group) on two of their pilgrimage rides, to Wales and Northern Ireland. In this role, I was a pilgrim but not a Biker. Michalowski and Dubisch describe their motorcycle pilgrimage research as ethnography of a cyclic ritual, and their participation as being “motivated by strong feelings that we had to go” (Michalowski and Dubisch 2001, p. 20). This paper’s primary research shares that ethnographic perspective, with my role as researcher situated within the group, as a participant-observer reflecting on subjective, personal experiences (Béres 2012; Scharen 2012). In common with the group’s founders, I share the characteristics of being ordained, located within the Diocese of Leeds, and, whilst not a biker myself, I am married to a biker who is a member of this group. As a Participant-Observer (Béres 2012; Scharen 2012), and as an ordained person who has accompanied the group on several longer trips, I concur with Michalowski and Dubisch, who observed that

We could not separate our personal identities from our professional selves … experiences bound us to the other riders and enabled us to understand their cause more than any statement of purpose or ideology from them could ever have done.(Michalowski and Dubisch 2001, p. 20)

4. Results and Discussion

The research results of interviews with the Biker Revs have been compared with the pilgrimage research outcomes of Michalowski and Dubisch (2001), especially with regard to the identified purpose of the rides, and of group identity. The initial trigger for the Biker Revs group was the creation of a new diocese, bringing together three former dioceses and additional geographic area changes, a unique event in the history of the Church of England. The purpose of setting up this group was to do something that helped both ordained and lay people from across the new diocese to “come together and get to know each other”, through a “shared interest”, —motorbiking.

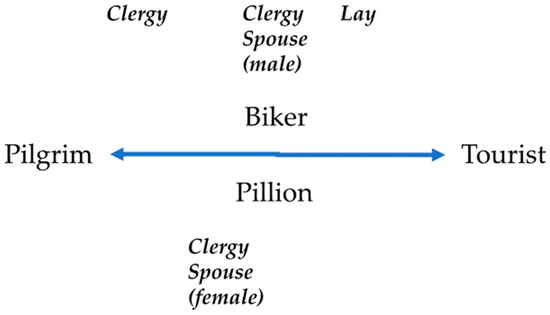

The Biker Revs’ experience of pilgrimage is applied to the Pilgrim-Tourist dichotomy, as the roles of biker/pillion rider and ordained clergy/spouse of ordained clergy/lay person also impact on the experience of pilgrimage and tourism, as expressed in Figure 8, below. This visually expresses an output of the research, demonstrating differences between the different roles. At the time of the research, all the bikers were male, and most bikers were also clergy. Similarly, all pillion riders were female, and most were clergy spouses. Figure 8 is my attempt to provide a summary interpretation of data from interview transcripts of responses to questions regarding the positioning of participants on the pilgrim–tourist scale (the bold line, left—pilgrim, to right—tourist).

Figure 8.

Pilgrim–tourist continuum applied to the Biker Revs.

I have positioned the labels in a way that attempts to represent the grouped positionings on the pilgrim–tourist axis. So, for example, (male) clergy bikers were most likely to define the longer trips as “pilgrimage”, and most likely to articulate reasons for motivation and experience that matched the academic definitions of characteristics of pilgrimage, such as being on a journey with a sacred purpose and destination, a sense of shared identity and belonging to the group, and personal spiritual benefits.

Female clergy spouses (all pillion riders) were most articulate on the benefits of being part of the group, also with a spiritual perspective of the experience:

It’s meeting other people, the companionship and actually the support for each other I think that’s built up over the different residentials, particularly. I would say that as a spouse you’re able to chat to people–like-minded people without any other distractions, and support each other;Sometimes I can’t face going on a retreat because I just don’t feel holy enough, I just feel I’ve had enough of trying to be holy and I don’t want any more;I suppose it’s being in an atmosphere where you can just be yourself really, there’s no expectations as a clergy spouse, particularly you feel as though you have a lot of expectations on you.

The male clergy spouse and the lay members of the group saw the longer trips as slightly less of a religious pilgrimage and slightly more like a holiday, although all participants acknowledged and valued the religious practices that the group undertook together. This was especially noticeable on the first trip, to Iona, where the group followed the Anglican daily office of Morning Prayer together and celebrated Holy Communion on the beach in Iona. On the trip to Corrymeela, the group joined with the community in their daily acts of worship, a different experience from Iona, but recognized for its spiritual significance. However, in Wales, the group chose to have personal prayer times rather than corporate acts of worship, and this change was appreciated by some, who valued the aspect of being on a religious retreat, which is also a requirement for Anglican clergy. One participant explained that in Wales they would have “felt a duty” to come to Morning Prayer because that is “what’s expected”, but they appreciated the opportunity to continue their own practice instead.

The American Run for the Wall motorcycle pilgrims and the Biker Revs shared the ritual of fellowship and prayer before setting off each day, and the Biker Revs celebrated Holy Communion on their travels, generally holding daily services (Morning Prayer and/or Compline). They recognized in their motorcycle rides, that kinship was a motivating factor; more than a “common interest”, it was a “shared passion”. Whether they used their motorbikes as their daily means of travel, or were leisure bikers, each told a story about their spiritual journey as bikers.

One interviewee (now a curate) used his motorbike as the focus for his presentation at the interview for discerning whether he should go forward for ordination training:

Like any other biker, I am passionate about my bike and the possibility of riding the open road on a warm summer’s day.

Recognising that historically, bikers were seen as “lawless and aggressive…biker gangs [are] still known as Hell’s Angels or the Devil’s Disciples”, he was able to develop close (male) friendships through biking together, and could “combine our love of bikes with our love of Christ”. Another interviewee recounted the story of two incidents that demonstrated the fearful response that they sometimes experienced as a biker group. The first took place on a day ride out in North Yorkshire as the group arrived and parked up. They asked a passer-by, a woman with two small children, to take a photograph of the group. The woman recoiled, and they all realized that she was petrified, as she grabbed her children, saying, “My husband’s at the bottom of the hill, he’s coming up”. The group leader explained that they were all vicars, so the woman relaxed visibly and took the photos. On another trip the group arrived at a local biker café in North Yorkshire, shortly followed by the arrival of another group of bikers, who approached them. When the Biker Revs said “oh, we’re vicars”, the new arrivals “backed away and left the café”. These incidents indicate the extent to which powerful negative stereotypes of both bikers and vicars can instil fear and trepidation. This connects with the sense of liminality in belonging to both groups—bikers and clergy.

When reflecting on the journey and destination, the motivations of the Biker Revs emerged. As Christians and especially those who are ordained, the idea of visiting a holy place is important, and such destinations are viewed as enabling authentic life-changing experiences. The longer trips, in particular, are viewed as transformational spaces. Several interviewees explained the vital role that the longer trips had played in their lives. For one spouse, facing a difficult work situation, the supportive relationships that were built up in this environment enabled sharing of problems and time for reflection, resulting in a positive decision to change direction. This interviewee had not previously known any of the other Biker Revs members, “it felt a bit daunting at first because I didn’t know anybody”, but the atmosphere was found to be open and welcoming. Another interviewee reflected on the transformative impact of each of the trips he had participated in. The Iona trip took place just before he was ordained and the Northern Ireland trip was a few weeks before his priesting, providing much needed time to unwind as well as “a lot of thinking time”; trips that were “very significant in where they’ve fallen in my Christian journey”. The Biker Revs’ longer trips provide space for physical and spiritual renewal, especially for clergy and their spouses, as well as an opportunity to receive pastoral care outside the parish. Most clergy interviewees and their spouses value the nature of the group as providing a “safe space”, where they are able to be themselves. “Friendship” and “fellowship” describe the impact of belonging to the group.

Other aspects of transformation have emerged from being part of the group. One surprising example was the change in attitude towards biking. One clergy spouse had never been on a long bike trip prior to coming to Iona, and so her biker husband had gone on earlier trips with their son. But she had always wanted to visit Iona, so she plucked up her courage and went on the trip. The following year, despite not liking boat travel, she joined the Biker Revs in Northern Ireland, which involved a ferry trip each way. Since that time, their joint holidays have been bike trips, including a trip to Europe by ferry. This was an unlikely transformation, made in part because of the strong relationships formed within the group.

Aspects of liminality emerged throughout the interviews, in terms of the physical space that biking embodies. Biking is a solitary experience, an escape, a time when bikers and pillion riders are able to be alone, even when riding alongside others. Kujawa (2017) notes the focus on internalized reflection during pilgrimage, citing Jung’s psychological typology that recognises the greater need for space and “alone-time” of introverts. In the interviews, it became apparent that all but one of the interviewees self-identified as introverts. The time whilst biking, even with a spouse, still incorporates separation from the world and from each other. Despite the availability of two-way intercoms, this communication option is often not employed because of their preference for silence. Clergy undertake training in understanding personality preferences as a matter of course, and many are familiar with the concepts of introversion and extroversion, referring to them in the interviews. In particular, one interviewee values the fact that whilst biking he does not “have to talk to people during the day”, noting that:

in this group there are a lot of people with the same sort of character as me so it’s not a problem if you don’t speak to them … it’s not strange.

Additionally, the shared interest of biking and the common professional role as clergy provide a focus for conversation, as well as practical aspects of the trip, such as meal arrangements and journey logistics.

Longer trips provide a liminal space, as participants are removed from the distractions of life, with time for reflection whilst riding. It is significant that the full-time clergy members of the Biker Revs group found the group as providing a “safe space”, where they could “be themselves”, outside of the confines of their parishes. For clergy and their spouses, Biker Revs trips provide an escape from the constant pressures of parish life, a time shared with others in similar situations, a place of friendship, sharing, openness and honesty, acceptance, freedom to be who they are, without being called on to help and support others “24/7”, and time “without being judged”, a place “where vicars can have real friends”. This sense of communitas is palpable, as participants relate to each other as equals, outside of normal church hierarchies. Not all Biker Revs are ordained; some have joined the group whilst on the journey to ordination and some are lay people, but on the road, there is no hierarchy. The shared experience of biking, whether bikers use their bikes for day-to-day transport, or are leisure riders, connects group members together with strong supportive bonds. Importantly, the main aim for founding the group, to bring people together from across the three former dioceses, has been successful, embedding a sense of belonging to the new diocese as bikers undertake geographic and spiritual journeys towards their sacred destinations.

Michalowski and Dubisch (2001) provided useful insights for interviewing Biker Revs. The spiritual benefits of the longer trips are evident, along with a sense of identity and belonging to the group, whether bikers or pillion riders. It became apparent that bikers and their pillion passengers had different motivations for participating. For the bikers, their bikes and biking were usually their passion, and whether they use their bikes for practical travel purposes in their daily lives, or as their ‘hobby’, whilst the perspectives of pillion passengers are notable in their diversity. One pillion-rider clergy spouse admitted that, “I hate speed, but it’s a gift to my husband£, an honoring of the depth of their marriage relationship that places the other first. This was echoed by another clergy spouse pillion rider who also expressed biking activity as a “gift” to their spouse. These articulations were especially humbling for me, because as a non-biker spouse of a biker, I recognize that I would not be willing or able to give the same gift to my own (much-loved) spouse. In contrast, another pillion rider was “brought up on a pillion with Dad”, so biking became second nature. When asked if the Biker Revs longer trips were “more than a holiday”, responses were similar across all interviewees, irrespective of their work roles. Clergy emphasized that this was more of a retreat than a holiday, placing themselves firmly in the pilgrimage category; for them, this is not a pleasure jaunt, but an opportunity to be “in a place with others of a like mind”. This phrase “like-minded people” —came up time and time again, especially from clergy, female clergy spouses, and ordinands.

This research has identified some key differences: firstly, that there are two key identifiable groupings: on the one hand, clergy with their spouses, and on the other hand, lay people. Having personally experienced the group dynamics it is possible that for clergy, the Biker Revs might emulate the emotional connections forged in pre-ordination training, which can be particularly strong, as clergy meet up for years afterwards with members of their prayer and study groups from theological college. Longer-term research would ask whether participants develop long-lasting, deep relationships through the Biker Revs activities. However, there is definitely a sense of belonging and a clear acknowledgement of identity in the group as it currently exists. The research identified impacts of personality, gender and role differences (clergy/spouse/lay) on responses. Whilst clergy and spouses value the distinctive nature of the group, another interviewee suggested that it was “an open group” with potential to become a “tool for evangelism”. Another contrast in impact was of the type of trip. Day rides out had a different outcome and atmosphere, compared to the longer trips which were viewed more as pilgrimage. There was unexpected learning about the positive well-being impact of the group, especially for vicars and their spouses, and discussions on benefits of the group for male spirituality that is not met by the usual church men’s groups and related activities.

5. Conclusions

The research indicates that the interviewee’s role in the church impacts on responses; these roles include vicars, curates, ordinands, clergy spouses and lay people. Future research might examine the impact of gender, as at the time of my research, the Biker Revs group only included one female vicar, and all the women rode pillion. Since 2018, there have been more ordained women bikers joining the Biker Revs group. The results of this research suggest that there is a significant relationship between engaging in a shared leisure pursuit (in this case, motorbiking), and developing strong interpersonal relationships and supportive friendships that carry on beyond the scope of the activity itself. This is particularly true for clergy and their spouses, which is useful for those organisations responsible for clergy wellbeing and motivation (such as dioceses and national church organisations).

Ordained bikers identified the group as a safe space for clergy, outside the parish, where “I can be me”, whilst spouses of clergy recognized the benefits of spending time with “others like me who understand the pressures of clergy life”, beyond the usual (and apparently less effective) clergy groups or clergy spouse support networks. Overall, the motivations for members of the Biker Revs group match those of traditional pilgrims and other biker pilgrims, such as those who participate in the ‘Run for the Wall’. Stipendiary clergy, in particular, value the benefits of this close community, where they find the freedom to act as they wish, safe amongst their peers. Finally, the trigger and purpose of the Biker Revs group has achieved its objective–to bring clergy and laity together from across the new diocese, building new relationships and support mechanisms, especially for clergy.

This paper offers substantive and literature-supported analysis of the diversification of motivations, perception of sacred journeys and authentic emotions accompanying pilgrimages; it presents the relationship between pilgrimage, the mission of proclaiming God’s word, and a type of religious tourism, in the context of the sense of community as well as time for contact with the sacred; it takes a qualitative ethnographic approach and considers the emerging perspectives of authenticity and credibility; and interprets sacred space through the analysis of its perception and shaping the sense of social ‘communion’.

The primary data demonstrates that this topic has future research potential in many areas, including the development of social capital and informal networks that thrive in this context; comparative studies with other biker groups, in the UK and internationally; male spirituality; personality and biking; transformational aspects of pilgrimage; life-changing impacts of biking trips for clergy; the development of clergy support networks and relationships; and the continuing development of the concept of eventization of faith.

Funding

This research was partially funded by retreat grants from The Diocese of Leeds (Anglican).

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the Biker Revs for their time, to colleagues at the International Conference on Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage in 2017 for their encouragement, and to the three peer reviewers for their helpful feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Abad-Galzacorta, Marina, and Basagaitz Guereño-Omil. 2016. Pilgrimage as Tourism Experience: The Case of the Ignatian Way. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 4: 48–66. [Google Scholar]

- Alford, Steven, and Suzanne Ferriss. 2006. Classifying Motorcycle Writing: A preliminary consideration. International Journal of Motorcycle Studies. Available online: http://ijms.nova.edu/July2006/IJMS_Resources.AlfordFerriss.html (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Béres, Laura. 2012. A Thin Place: Narratives of Space and Place, Celtic Spirituality and Meaning. Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought 31: 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogle, Alison. 2016. Diocese to be known as ‘Diocese of Leeds’. Leeds Diocese. April 13. Available online: http://www.westyorkshiredales.anglican.org/content/maps-and-information-about-deaneries-and-parishes (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Cassar, George, and Dane Munro. 2016. Malta: A Differentiated approach to the pilgrim-tourist dichotomy. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 4: 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Michael H. 2000. Christian Forgiveness in Northern Ireland. Contemporary Review 276: 235–39. [Google Scholar]

- Corrymeela Community. n.d. Available online: http://www.corrymeela.org/about/our-history (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Diocese of West Yorkshire and the Dales. 2014. Map of the new Diocese of West Yorkshire and the Dales. Available online: http://www.westyorkshiredales.anglican.org/content/maps-and-information-about-deaneries-and-parishes (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Dowson, Ruth, Jabar Yaqub, and Razaq Raj. 2019. Spiritual and Religious Tourism: Motivations and Management. Wallingford: CABI. [Google Scholar]

- du Cros, Hilary, and Bob McKercher. 2015. Cultural Tourism, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dubisch, Jill. 2004. ‘Heartland of America’: Memory, Motion and the (Re)construction of History on a Motorcycle Pilgrimage. In Reframing Pilgrimage: Cultures in Motion. Edited by Coleman Simon and Eade John. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dubisch, Jill. 2008. Sites of Memory, Sites of Sorrow: An American Veterans’ Motorcycle Pilgrimage. 2008. In Shrines and Pilgrimage in the Modern World: New Itineraries into the Sacred. Edited by Peter J. Margry. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dubisch, Jill, and Michael Winkelman. 2005. Pilgrimage and Healing. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, Roberto. 2010. Communitas: The Origin and Destiny of Community. Translated by Campbell Timothy. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fladmark, Jan M., ed. 1998. In Search of Heritage: As Pilgrim or Tourist? Aberdeen: The Robert Gordon University Heritage Library. [Google Scholar]

- Frisk, Henrik, and Stefan Östersjö. 2013. Beyond Validity: Claiming the Legacy of the Artist-Researcher. Svensk Tidskrift för Musikforskning 95: 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kaell, Hillary. 2016. Notes on Pilgrimage and Pilgrimage Studies. Practical Matters Journal 9: 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa, Joanna. 2017. Spiritual Tourism as a Quest. Tourism Management Perspectives 24: 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeds Diocese. 2014. Available online: www.leeds.anglican.org (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Leppäkari, Maria, and Kevin Griffin, eds. 2017. Pilgrimage and Tourism to Holy Cities: Ideological and Management Perspectives. Wallingford: CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Merkel, Udo, ed. 2015. Identity Discourses in International Events, Festivals and Spectacles. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Michalowski, Raymond, and Jill Dubisch. 2001. Run for the Wall: Remembering Vietnam on a Motorcycle Pilgrimage. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Robert L. 2001. The Archetype of Initiation: Sacred Space, Ritual Process and Personal Transformation–Lectures and Essays. Edited by Max J. Havlick, Jr. Bloomington: Xlibris Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, Alex. 2011. Spiritual Tourism: Travel and Religious Practice in Western Society. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Pfadenhauer, Michaela. 2010. The Eventization of Faith as a marketing strategy: World Youth Day as an innovative response of the Catholic Church to pluralization. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 15: 382–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, Rosemary. 2006. A Place of Community: ‘Celtic Iona and Institutional Religion. Folklore 117: 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Raj, Razaq, and Kevin A. Griffin, eds. 2015. Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Management: An International Perspective. Wallingford: CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Remsberg, Rich. 2000. Riders for God: The Story of a Christian Motorcycle Gang. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scharen, Christian B., ed. 2012. Explorations in Ecclesiology and Ethnography. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Scriven, Richard. 2014. Geographies of Pilgrimage: Meaningful Movements and Embodied Mobilities. Geography Compass 8: 249–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackley, Myra. 2001. Managing Sacred Sites: Service Provision and Visitor Experience. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, David. 2019. Interpreting Qualitative Data, 6th ed. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Stillman, Sean. 2018. God’s Biker: Motorcycles and Misfits. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm, Damion. 2015. ‘Fluid Spectator-Tourists’: Innovative Televisual Technologies, Global Audiences and the 2015 Cricket World Cup. Communicazioni Sociali 2015: 230–40. [Google Scholar]

- Symes, Colin. 2009. Early Northumbrian Spirituality: The Fruit of Straitened Circumstances. Journal of European Baptist Studies 10: 6–18. [Google Scholar]

- The 59 Club. n.d. Available online: https://www.the59club.co.uk/history-c1d3n (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Turner, Victor, and Edith Turner. 1978. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture. New York: Colombia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Peter, ed. 2012. Perspectives in Ecclesiology and Ethnography. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggen, Todd C. 2019. An Autoethnographic Exploration of Social Identity and Leadership within a Motorcycle Club. Journal of Motorcycle Studies 15: 2019. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).