Constructing and Contesting the Shrine: Tourist Performances at Seimei Shrine, Kyoto

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods

3. The Case of Seimei Shrine, Kyoto

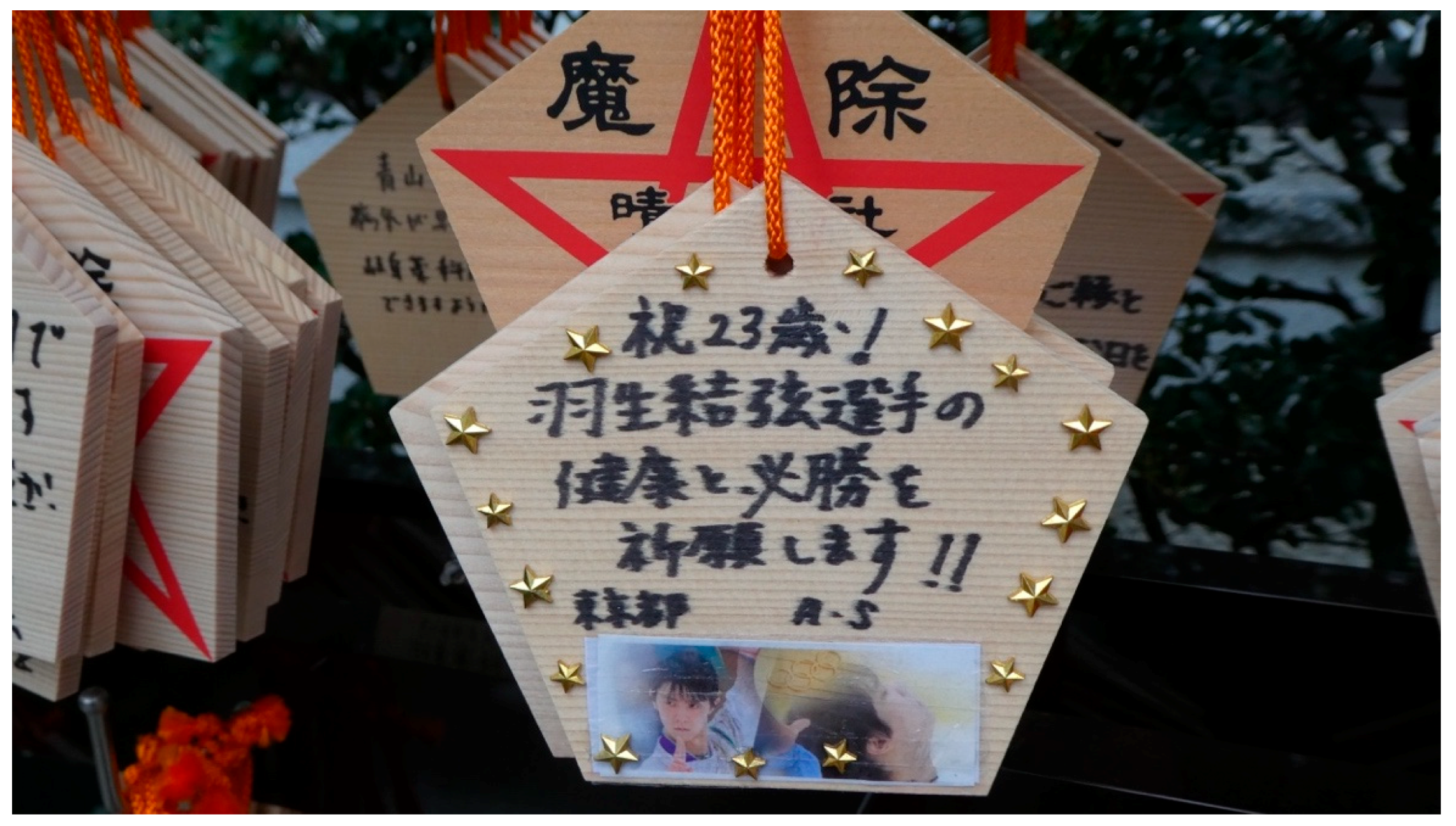

On the 2nd of July, [Hanyu] visited Seimei Shrine in order to get a deeper understanding [of Abe no Seimei]. Immediately after entering the shrine premises, he showed wariness and said ‘I can feel ki [energy]’. He suddenly realized that he will perform the actual presence of a god. He was shown the portrait of Abe no Seimei from the shrine’s private collection. Also by placing his hands on it, he received power from the 300 year old sacred tree. Almost as if he was asking Abe no Seimei for permission [to perform], he walked around the shrine premises for an hour, although it would normally take only ten minutes.

4. Constructing, Performing and Contesting Seimei Shrine

4.1. The Construction of Seimei Shrine—Theming the Shrine

For most visitors, the different signs act as the main source of information. They are ‘on-site markers’ (MacCannell 1999), which also affect the visitors’ interpretations and behavior, showing them what is ‘worth seeing’ at the shrine. The explanations use different narrative elements in order to convey the official interpretations of the objects as well as the general theme of the shrine. Connecting the peach statue to famous folktales enhances the story-like theme of the shrine, whereas by encouraging physical engagement, the peach is given a certain spiritual status as an object that wards off evil, thus combining mythical elements with a concrete suggestion of action (Figure 1). The sign also has a commercial function, as below the explanation the shrine promotes a special peach amulet sold at the shrine office.Since ancient times, in China as well as in the practice of Onmyōdō, the peach has been told to be a fruit that protects against misfortune. Even in Kojiki and Nihonshoki, the peach has been described as warding off evil. This can be seen as the origin of the folktale Momotarō, too. Everyone has their own bad luck and misfortunes. By stroking away the bad luck onto this peach, you can feel refreshed.(Sign explaining the statue)

Visitor A: Shimogamo Shrine has a lot of green. It’s a forest, so I received power [energy] there. I wonder what the difference [with Seimei Shrine] is? It feels more sacred there. It might be because Seimei Shrine has too many visitors? And the trees are all planted.Visitor B: It feels more sacred, when there’s nature.Visitor A: Of course [Seimei Shrine] is sacred. But because there are a lot of people here, Shimogamo Shrine feels more soothing.(Visitors in their 30s)

4.2. Performing the Shrine—The Different Meanings People Bring to the Shrine

[Seimei Shrine] has become a famous shrine. Compared to before, this is all thanks to Hanyu (laugh). I do not think that people really knew much about onmyōji or Abe no Seimei, that is why [it became famous].(Visitor in their 50s)

For this visitor, the fact that the goshuin was not handwritten led them to the decision not to acquire one. On the other hand, the following comment shows the perceived importance of the appearance of the goshuin:“(Seimei Shrine is) a power spot I have wanted to visit. I was surprised by the constant flow of visitors. I wanted to get the goshuin but it was pre-written.”(Posted by Eightwalker 2018)

From these comments, one can see that the visitors have their own criteria of authenticity apart from the religious context. From the shrine’s point of view, the goshuin are authentic—handwritten or not. However, the visitors think that the actual act of writing is a vital part of the authenticity of the goshuin. This can be said to reflect the way visitors perceive shrines and the objects there as something traditional, opposed to something seemingly premade or mass produced, such as a stamped goshuin. The fact that the shrine staff ask whether it is ok that the goshuin is stamped or not, shows that the shrine has also adapted to the visitors’ needs.“No part of the goshuin was handwritten, even the date was a stamp. At least they were honest about it when they confirmed whether it was ok that it was all stamped. You cannot tell whether it is handwritten or not from the quality of the goshuin. At least is better than the poor goshuin written by a part-timer with a dried up calligraphy pen at the famous Tenjin-san14.”(Posted by (418ken 2017))

As I said before, I got a favor from the shrine a while ago. When I started working at my company, I had an unkind colleague. When I bought a talisman and placed it beneath my desk every day, the colleague went away [from the company]. I was very grateful because of that. Based on this experience, I can say that [the shrine] is very effective.(Visitor in their 40s)

4.3. Contesting the Shrine—The Souvenir Dispute

From the official announcement, we can see that souvenirs and their authenticity are in the center of this conflict. The official announcement also tells us that there are three different actors involved in the dispute—the shrine, the souvenir shop and the visitors. All of these actors involved had their own meanings and sense of authenticity, which is constituted in different ways.The ‘Onmyōji goods’ and ‘Good luck goods’ sold close to the shrine by the Tajima orimono kabushikigaisha16 (Onmyōji honpo), have not been purified or blessed at the shrine. We have nothing to do with them.Selling these kinds of objects close to the shrine is inappropriate and desecrates the divine virtues of Abe no Seimei considerably and we have asked the shop to stop selling them. However, the problem has not been solved and the situation is getting serious. For everyone visiting the shrine, please understand the situation and be careful of the following things.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 418ken. 2017. “Goshuin Ga …” TripAdvisor. Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.jp/ShowUserReviews-g298564-d1568228-r463974741-Seimei_Shrine-Kyoto_Kyoto_Prefecture_Kinki.html (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- Amada, Akinori. 2020. Sairei No Chūshi, Yōkai No Ryūkō—‘Ekibyō Yoke’ Wo Tegakari Ni. In Ajia Yūgaku 253: Posuto Korona Jidai No Higashi Ajia. Edited by Mooam Hyun and Yohei Fujino. Tokyo: Bensei Shuppan, pp. 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, Dale K. 2014. Genesis at the Shrine: The Votive Art of an Anime Pilgrimage. In Mechademia 9. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 217–33. [Google Scholar]

- Asahi Shimbun. 2010. (Shun-Kan) Pawā, Kitemasu (Osaka). Asahi Shimbun, November 6. [Google Scholar]

- Bærenholdt, Jørgen Ole, Michael Haldrup, Jonas Larsen, and John Urry. 2004. Performing Tourist Places. London: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, Edward M. 2005. Culture on Tour: Ethnographies of Travel. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, Alan. 2004. The Disneyization of Society. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Caleb. 2018. Power Spots and the Charged Landscape of Shinto. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 45: 145–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidester, David, and Edward T. Linenthal. 1995. Introduction. In American Sacred Space. Edited by David Chidester and Edward T. Linenthal. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Erik. 1979. A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences. Sociology 13: 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Erik, and Scott A. Cohen. 2012. Authentication: Hot and Cool. Annals of Tourism Research 39: 1295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, Noga. 2020. A Review of Research into Religion and Tourism Launching the Annals of Tourism Research Curated Collection on Religion and Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 82: 102892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, Inge. 2003. Scooping, Raking, Beckoning Luck: Luck, Agency and the Interdependence of People and Things in Japan. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 9: 619–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, Inge. 2012. Beneficial Bonds: Luck and the Lived Experience of Relatedness in Contemporary Japan. Social Analysis 56: 148–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, Tim. 1998. Tourists at the Taj. Performance and Meaning at a Symbolic Site. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Edensor, Tim. 2000. Staging Tourism: Tourists as Performers. Annals of Tourism Research 27: 322–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, Tim. 2001. Performing tourism, staging tourism: (Re)producing tourist space and practice. Tourist Studies 1: 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eightwalker. 2018. “Pawāsupotto.” TripAdvisor. Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.jp/ShowUserReviews-g298564-d1568228-r639327485-Seimei_Shrine-Kyoto_Kyoto_Prefecture_Kinki.html (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- Einstein, Mara. 2007. Brands of Faith: Marketing Religion in a Commercial Age. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Michael Dylan. 2020. Eloquent Plasticity. Journal of Religion in Japan 9: 118–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldrup, Michael, and Jonas Larsen. 2010. Tourism, Performance and the Everyday: Consuming the Orient. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, Makoto, and Matthias Hayek. 2013. Editors’ Introduction: Onmyodo in Japanese History. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 6: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Leighanne, and Kathy Hamilton. 2020. Pilgrimage, Material Objects and Spontaneous Communitas. Annals of Tourism Research 81: 102855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, Noboru. 2015. Hatsumōde No Shakai Shi. Tetsudō Ga Unda Goraku to Nashonarizumu. Tokyo: Tokyo Daigaku Shuppan-kai. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschkind, Charles. 2006. The Ethical Soundscape: Cassette Sermons and Islamic Counterpublics. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Horie, Norichika. 2017. The Making of Power Spots: From New Age Spirituality to Shinto Spirituality. In Eastspirit: Transnational Spirituality and Religious Circulation in East and West. Leiden: BRILL, pp. 192–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, Norichika. 2019. Poppu Supirichuariti: Media Ka Sareta Shūkyō. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Industry and Tourism Bureau. 2019. “Kyōto Kankō Sōgō Chōsa.” City of Kyoto. Available online: https://www.city.kyoto.lg.jp/sankan/page/0000271459.html (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Ishii, Kenji. 2010. Purorōgu: Jinja Shintō Wa Suitai Shita No Ka. In Shintō Wa Doko E Iku Ka. Edited by Kenji Ishii. Tokyo: Perikansha, pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Isomae, Jun’ichi. 2012. The Conceptual Formation of the Category ‘Religion’ in Modern Japan: Religion, State, Shintō. Journal of Religion in Japan 1: 226–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isomae, Jun’ichi. 2014. Religious Discourse in Modern Japan: Religion, State, and Shintō. Leiden: BRILL. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Siân. 2010. Negotiating Authentic Objects and Authentic Selves. Journal of Material Culture 15: 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephson, Jason Ānanda. 2012. The Invention of Religion in Japan. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kadota, Takehisa. 2013. Junrei Tsūrizumu No Minzoku Shi—Shōhi Sareru Shūkyō Keiken. Tokyo: Shinwasha. [Google Scholar]

- Kadota, Takehisa. 2016. Seichikankō No Kūkanteki Kōchiku–Okinawa, Sefa-Utaki No Kanrigihō To “Seichirashisa” No Seisei Wo Megutte. Kankogakuhyōron 4: 161–75. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, Webb. 2007. Christian Moderns: Freedom & Fetish in the Mission Encounter. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, Webb. 2008. On the Materiality of Religion. Material Religion 4: 230–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, E. Frances. 2010. Material Religion and Popular Culture. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnard, Jacob N. 2014. Places in Motion: The Fluid Identities of Temples, Images, and Pilgrims. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kopytoff, Igor. 1986. The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process. In The Social Life of Things. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 64–92. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer, Hans Martin. 2013. How ‘Religion’ Came to Be Translated as Shukyo: Shimaji Mokurai and the Appropriation of Religion in Early Meiji Japan. Japan Review 25: 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, Jonas. 2006. Geographies of Tourism Photography: Choreographies and Performances. In Geographies of Communication: The Spatial Turn in Media Studies. Edited by André Jansson and Jesper Falkheimer. Gothenburg: Nordicom, pp. 243–60. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, Dean. 1973. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. American Journal of Sociology 79: 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, Dean. 1999. The Tourist. A New Theory of the Leisure Class. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit, David Morgan, Crispin Paine, and S. Brent Plate. 2010. The Origin and Mission of Material Religion. Religion 40: 207–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Birgit. 2009. Introduction: From Imagined Communities to Aesthetic Formations: Religious Mediations, Sensational Forms, and Styles of Binding. In Aesthetic Formations. Edited by Birgit Meyer. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Laura. 2008. Extreme Makeover for a Heian-Era Wizard. In Mechademia 3. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, David, ed. 2010. Religion and Material Culture: The Matter of Belief. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Nigel, and Annette Pritchard. 2005. On Souvenirs and Metonymy: Narratives of Memory, Metaphor and Materiality. Tourist Studies 5: 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan Inc. 2001. 2001-Nen (Heisei 13-Nen) Kōshū 10-Oku En Ijō Bangumi. Available online: http://www.eiren.org/toukei/img/eiren_kosyu/data_2001.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Murakami, Koichi. 2012. Kyoto, Seimei Jinja vs. Seimei Kun. Asahi Shimbun, December 26. [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi, Yuji. 2018. Shintoism and Travel in Japan. In Tourism and Religion: Issues and Implications. Edited by Richard Butler and Wantanee Suntikul. Bristol: Channel View Publications, pp. 68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, John K. 1996. Freedom of Expression: The Very Modern Practice of Visiting a Shinto Shrine. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 23: 117–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, John K. 2000. Freedom of Expression: The Very Modern Practice of Visiting a Shinto Shrine. In Enduring Identities: The Guise of Shinto in Contemporary Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 22–52. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, Ryosuke. 2015. Seichi Junrei—Sekai Isan Kara Anime No Butai Made. Tokyo: Chuōkōron Shinsha. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, Ryosuke. 2019a. Pilgrimages in the Secular Age: From El Camino to Anime. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture (JPIC). [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, Ryosuke. 2019b. Practicing without Believing in Post-Secular Society: The Case of Power Spot Boom in Contemporary Japan. Jōchi Daigaku Yōroppa Kenkyū Sōsho 12: 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, Ryosuke. 2020. Jenerikku Shūkyō Shiron. In Gendai Shūkyō To Supirichuaru Māketto. Edited by Hiroshi Yamanaka. Tokyo: Kōbundō, pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Paine, Crispin. 2019. Beyond Museums: Religion in Other Visitor Attractions. ICOFOM Study Series 47: 157–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcu, Elisabetta. 2012. Observations on the Blurring of the Religious and the Secular in a Japanese Urban Setting. Journal of Religion in Japan 1: 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcu, Elisabetta. 2013. Sacred Spaces Reloaded: New Trends in Shinto. In Self-Reflexive Area Studies. Edited by Matthias Middell. Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag, pp. 279–94. [Google Scholar]

- Porcu, Elisabetta. 2014. Pop Religion in Japan: Buddhist Temples, Icons, and Branding. Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 26: 157–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambelli, Fabio. 2007. Buddhist Materiality: A Cultural History of Objects in Japanese Buddhism. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reader, Ian, and George Tanabe. 1998. Practically Religious: Worldly Benefits and the Common Religion of Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reader, Ian. 1991. Letters to the Gods: The Form and Meaning of Ema. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1: 24–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reader, Ian. 2014. Pilgrimage in the Marketplace. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rots, Aike P. 2017. Public Shrine Forests? Shinto, Immanence, and Discursive Secularization. Japan Review 30: 117–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rots, Aike P., and Mark Teeuwen. 2017. Introduction: Formations of the Secular in Japan. Japan Review 30: 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sano, Kazufumi. 2007. Ujiko. In Encyclopedia of Shinto. Tokyo: Kokugakuin University. Available online: http://eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp/modules/xwords/entry.php?entryID=1161 (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Seimei Shrine. 2012. “Seimei Jinja Yori Taisetsuna Oshirase [Important Announcement from Seimei Shrine].” 2012. Available online: https://www.seimeijinja.jp/archives/date/2011/10?cat=3 (accessed on 8 October 2018).

- Shigeta, Shin’ichi. 2013. A Portrait of Abe No Seimei. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 40: 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, Kiran A. 2013. “Re–Scripting the Legends of Tuḷjā Bhavānī: Texts, Performances, and New Media in Maharashtra”. International Journal of Hindu Studies 17: 313–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, Kiran A. 2020. Religious Theme Parks as Tourist Attraction Systems. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonoda, Minoru. 1975. The Traditional Festival in Urban Society. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1: 103–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suga, Naoko. 2010. Pawāsupotto to Shite No Jinja. In Shinto Wa Doko e Iku Ka. Edited by Kenji Ishii. Tokyo: Perikansha, pp. 232–52. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Ryotaro. 2020. Shōhi Sareru Basho, Datsu Shōhin Ka Sareru Tabi: Pawāsupotto Kankō to Ryokō Sangyō No Henyō. In Gendai Shūkyō To Supirichuaru Māketto. Edited by Hiroshi Yamanaka. Tokyo: Kōbundō, pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Takaba, Mizuho. 2015. Hanyu Narikitta Onmyoji Sekai Ni ‘wa’ Mitomesaseta. Nikkan Sports. November. Available online: https://www.nikkansports.com/sports/news/1572765.html (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Terzidou, Matina. 2020. Re-Materialising the Religious Tourism Experience: A Post-Human Perspective. Annals of Tourism Research 83: 102924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timm Knudsen, Britta, and Anne Marit Waade. 2010. Performative Authenticity in Tourism and Spatial Experience: Rethinking the Relations between Travel, Place and Emotion. In Re-Investing Authenticity: Tourism, Place and Emotions. Edited by Anne Marit Waade and Britta Timm Knudsen. Bristol and Buffalo: Channel View Publications, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada, Hotaka, and Toshihiro Omi. 2011. Gendai Nihon ‘Shūkyō’ Jōhō No Hanran. Shin Shūkyō, Pawāsupotto, Sōgi, Butsuzō Ni Chūmoku Shite. In Gendai Shūkyō 11: Gendai Shūkyō No Naka No Shūkyō Dentō. Tokyo: Akiyama Shoten, pp. 284–307. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, John, and Jonas Larsen. 2011. The Tourist Gaze 3.0. London: SAGE Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, John. 1990. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, Manuel A. 2011. More Than Belief: A Materialist Theory of Religion. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Ning. 1999. Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Experience. Annals of Tourism Research 26: 349–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, Takayoshi. 2015. Contents Tourism and Local Community Response: Lucky Star and Collaborative Anime-Induced Tourism in Washimiya. Japan Forum 27: 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, Hiroshi. 2012. Shūkyo To Tsūrizumu Kenkyū Wo Mukete. In Shūkyō To Tsūrizumu. Edited by Hiroshi Yamanaka. Kyoto: Sekaishishosha, pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka, Hiroshi. 2015. Tsūrizumu To Konnichi No Seichi—Nagasaki No Kyōkaigun No Sekai Isan Ka Wo Chūshin Ni Shite. Shigaku 85: 581–610. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka, Hiroshi. 2016. Shūkyō Tsūrizumu To Gendai Shūkyō. Kankogakuhyōron 4: 149–59. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka, Hiroshi. 2017. Shōhishakai Ni Okeru Gendai Shūkyō No Henyō. Shūkyō Kenkyū 90: 255–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka, Hiroshi. 2020. Gendai Shūkyō To Supirichuaru Māketto. In Gendai Shūkyō To Supirichuaru Māketto. Edited by Hiroshi Yamanaka. Tokyo: Kōbundō, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For example, in a Kyoto tourism survey, shrines and temples were given as the most popular reason for traveling to Kyoto for both Japanese as well as foreign visitors (Industry and Tourism Bureau 2019). |

| 2 | In Japanese, tourism in religious places is called shūkyō tsūrizumu (literally, religion tourism), which is not the exact equivalent of religious tourism. The term itself does not take a stance on whether the tourist is traveling for religious reasons or not, whereas the English term includes religious motivation behind travel. This can be seen as a major difference in the focus of the field in Japan. |

| 3 | The term power spot refers to a location in which one can feel a strong, invisible spiritual power, energy or ki (Japanese for qi) (Horie 2017, p. 192). While the idea of power spots emerged in the mid-1980s via the global New Age movement (Carter 2018), it entered the vocabulary of mainstream Japanese society in the 2010s through media representations, such as women’s magazines (Tsukada and Omi 2011). Many pre-existing religious places, such as Shinto shrines, have been reframed as power spots by the mass media (Okamoto 2019a). |

| 4 | Onmyōji is a practitioner of Onmyōdō, which can be translated as ‘The Way of Yin-yang’. In the Heian period, onmyōji were civil servants in the Onmyōdō bureau in the ritsuryō system of governance. They were experts in astrology, calendar studies and divination. There are debates whether Onmyōdō should be considered a religion or a technique (see Hayashi and Hayek 2013). |

| 5 | On recent discussion about tourism and festivals (matsuri), see the Special Issue of Journal of Religion in Japan Vol. 9 (2020). |

| 6 | This paper focuses on visitors from outside of the shrine. However, the special relationship between the local community and the shrine should be noted, as many neighborhoods are closely linked to the area’s Shinto shrine. As the local deity (ujigami) of the neighborhood is revered in the shrine, the ‘group from the land surrounding the areas dedicated to the belief in and worship of one shrine; or, the constituents of that group’ are traditionally referred to as ujiko (Sano 2007). For more on ujiko and the role they play in for example local festivals, see (Porcu 2012; Sonoda 1975). In addition, the term sūkeisha is used, but ‘the two are distinguished by a geographical classification with ujiko referring to the person from that shrine’s ujiko district and sūkeisha referring to the person from outside the district’ (Sano 2007). Ishii has noted that the role of sūkeisha will become greater due to the weakening of the consciousness of belonging to one’s local shrine (Ishii 2010). In fact, Seimei Shrine established an organization (sūkeikai) for patrons outside of the local community to which anyone can participate by paying a membership fee |

| 7 | In popular culture, Abe no Seimei has become a sorcerer-type hero figure, who protects the Heian court from evil spirits and other enemies. For details of Abe no Seimei’s life based on historical records, see for example Shigeta (2013). For more on the so-called Seimei boom, see Miller (2008). This paper will not focus on the worship of Abe no Seimei or the practice of Onmyōdō, but the process through which the shrine has become a tourist attraction. |

| 8 | The movie was released outside Japan under the title of Onmyoji: The Yin Yang Master (2001). With a box-office gross of approximately 3 billion yen, the movie was the fourth most popular movie of the year 2001 (Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan 2001). |

| 9 | All the translations are by the author. |

| 10 | For example, a Special Issue of the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 45/2 (2018) was dedicated on the topic. |

| 11 | Onmyōdō is a Japanese esoteric cosmology, which is based on ancient Chinese philosophy. The pentagram (gobōsei) is said to symbolize the five elements (gogyō), which are the basic principles of Onmyōdō along with yin-yang (onmyō). It is also used as the logo of Seimei Shrine and can be found in different forms around the shrine. |

| 12 | Interestingly, while the statue is made based on a Heian-era portrait of a middle-aged Abe no Seimei, the illustrations on the picture boards feature Abe no Seimei as a handsome young man, adapting to the current image of the wizard. |

| 13 | Not only between individual Shinto shrines and visitors, this gap can be observed on a national level. For example, the umbrella organization for Shinto shrines, Jinja Honchō, has dismissed the popularity of power spots as a short-term trend that does not support long-term engagement (Carter 2018, p. 162). Carter argues that by delineating power spot related practices, the organization attempts to establish a set of norms for shrine worship, which points to an underlying concern regarding Jinja Honchō’s authority over ritual and practice (Carter 2018, p. 163). |

| 14 | It is not clear which shrine the commentor is referring to, as the name Tenjin-san is often used to refer to shrines of Sugawara no Michizane (845–903), nowadays revered as Tenman-Tenjin, the god for learning. From the context, the comment could be referring to Kitano Tenmangū Shrine in Kyoto, located fairly close to Seimei Shrine. |

| 15 | Miller has noted that Shinto shrines dedicated to Abe no Seimei started producing and selling religious paraphernalia targeted especially towards young girls during the Seimei boom (Miller 2008, p. 36). Seimei Shrine sells both souvenirs and religious objects within its premises. The religious objects are mainly sold at the shrine office, whereas souvenirs are sold at Kikyōan. At the time of my fieldwork, religious objects, such as 16 different types of amulets (omamori), three types of talismans (ofuda), and purifying sand were sold at the shrine office. There are also special amulets, only available during certain periods or events. However, the shrine office also sells seemingly secular items such as a small comic book about Abe no Seimei’s life, as well as special stationery. |

| 16 | The textile company, which owned the souvenir shop. |

| 17 | The osamefudadokoro is a box in which old religious objects are placed when brought back to the shrine. There is a custom that old religious objects should be ritually disposed of at a shrine. Many of the visitors interviewed in January 2018 brought back their old amulets to Seimei Shrine. |

| 18 | Yakudoshi are certain ages when people are thought to be especially open to misfortune. The years before and after are also considered dangerous. According to Reader and Tanabe, ‘praying for the eradication of dangers is a major category of benefit seeking, and yakudoshi-related prayers and actions are one of the most prevalent occasions when this occurs’ (Reader and Tanabe 1998, p. 62). |

| 19 | From a historical point of view, this can also be linked to the separation of the religious and the secular in the modernization of Japan, especially with the formation and use of the term religion (shūkyō). As a political choice, to distinguish Shinto (or specifically State Shinto) from Buddhism and Christianity, Shinto was classified as morality instead of a religion (Isomae 2012). As an in-depth discussion of the topic is beyond the scope of this article, see for example (Isomae 2012, 2014; Josephson 2012; Krämer 2013; Rots and Teeuwen 2017). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tillonen, M. Constructing and Contesting the Shrine: Tourist Performances at Seimei Shrine, Kyoto. Religions 2021, 12, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010019

Tillonen M. Constructing and Contesting the Shrine: Tourist Performances at Seimei Shrine, Kyoto. Religions. 2021; 12(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleTillonen, Mia. 2021. "Constructing and Contesting the Shrine: Tourist Performances at Seimei Shrine, Kyoto" Religions 12, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010019

APA StyleTillonen, M. (2021). Constructing and Contesting the Shrine: Tourist Performances at Seimei Shrine, Kyoto. Religions, 12(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010019