3.1. The Sanctuary in the City Space

Sanctuaries, through their architectural form and functions, mark their presence in the urban space. They constitute a significant, symbolic space, often with great religious and cultural potential. Their impact on the city may be of a different nature and may have various effects (

Figure 2). The conducted research on selected European Catholic sanctuaries has made it possible to distinguish three important spatial scales of the described phenomena (

Sołjan 2012), (

Figure 2):

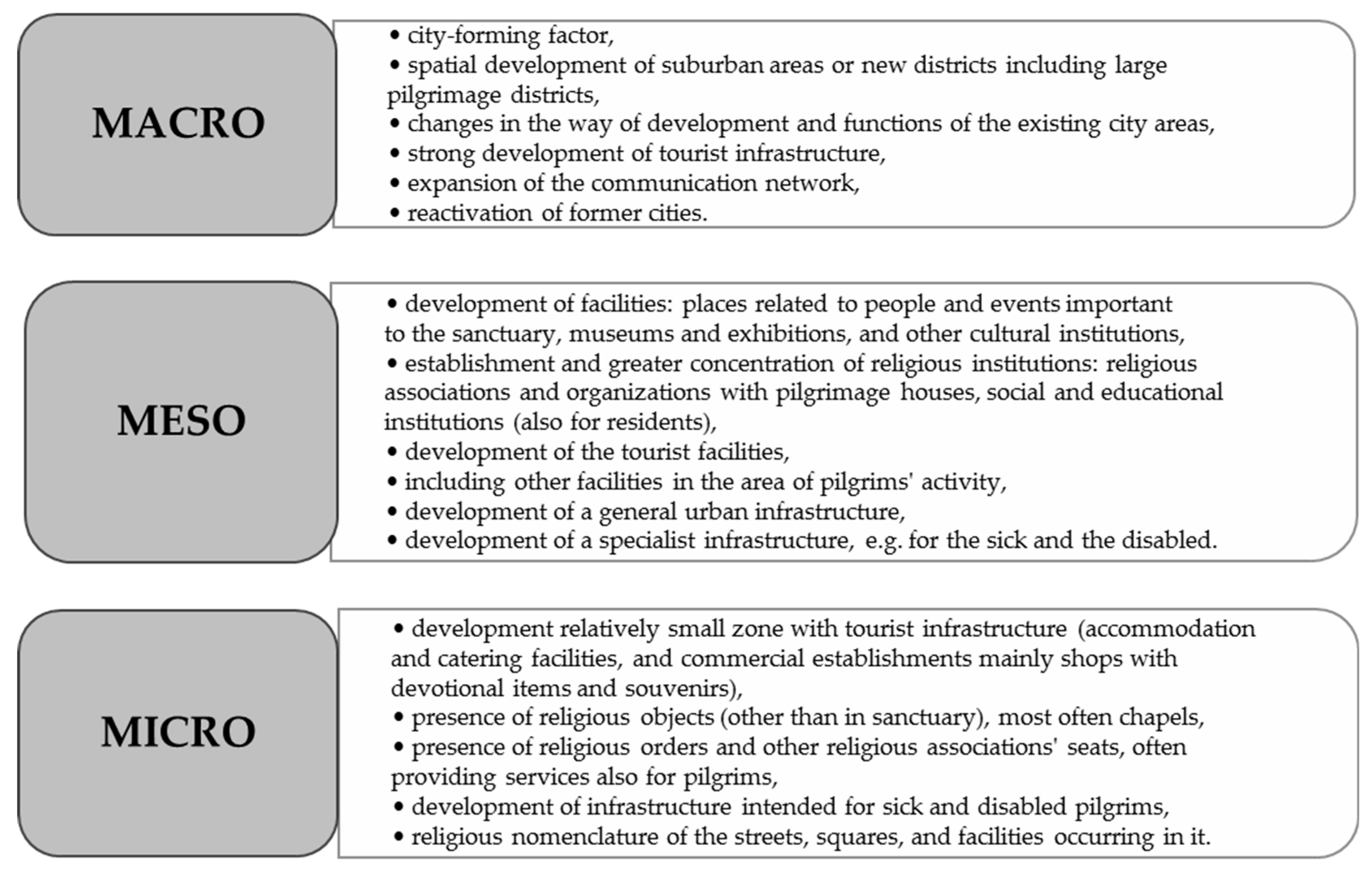

I. Changes on a macro scale: these are the greatest changes taking place in the city under the influence of the pilgrimage center, leading to fundamental changes in the urban structure and its functions.

II. Changes on a meso scale: the impact of the pilgrimage center on a meso scale is manifested in the creation of various objects, institutions, and places in the city space related thematically or functionally to it, which are located outside the sanctuary and its immediate surroundings.

III. Changes on a micro scale: the impact on a micro scale leads to changes in the urban space only in the immediate vicinity of the sanctuary. The effect of the discussed influence of the pilgrimage center is a relatively small zone with service infrastructure used by pilgrims and tourists developing around it.

3.1.1. Macro-Scale Impact on City Space

The greatest influence of a pilgrimage center on the organization of the space and structure of a city, defined as a macro-scale impact, takes place when there are serious spatial and functional changes in the urban structure, covering even entire settlement units in the case of smaller city centers, or significant parts of them (in the case of larger cities). Among these types of changes, the most important are changes:

Resulting in the emergence of a city center;

Leading to the spatial development of an existing city and the emergence of new districts, including large sanctuary service zones (pilgrimage district);

In the way of development and functional changes in the already existing city areas;

Causing the reactivation of former cities.

All these processes are generally long term, observed from a multiyear historical perspective, fundamentally changing the urban landscape. They occur mainly in the case of highly renowned (international and national) pilgrimage centers with several million people each year. They also depend on the stage of development of a given city, as well as on many social conditions, including urban policy, and sometimes even the policy of state authorities (the example of Fatima).

The city-forming function of pilgrimage centers was observed as early as in ancient times, in many now forgotten religions, such as Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt and Greece. In Western Christianity, the Middle Ages were a period favorable for the development of cities based on sanctuaries. The best example here is Santiago de Compostela, today a city with 100,000 inhabitants in Spanish Galicia, the origin of which was the tomb of St. James the Apostle discovered there at the beginning of the 9th century. Miraculous events such as this attracted the local population and aroused the interest of the church hierarchy, which resulted not only in establishing a holy place, but also in the development of settlements around it. Despite the change in social and political paradigms, the end of the Middle Ages did not stop these processes and new sanctuaries and new cities continued to emerge. Such aspirations were fostered, for example, by counter-reformation trends aimed at renewing and reviving Catholicism. In 1602, the first Calvary was founded in Poland, and the settlement which developed around the Calvary and the monastery was granted a town charter as Nowy Zebrzydow as early as in 1640. The current name of Kalwaria Zebrzydowska was not adopted until the 19th century. Additionally, in Poland, the establishment of Kalwaria Wejherowska in Pomerania was associated with the simultaneous location of the city of Wejherowo, which was granted a city charter in 1648. In modern times, despite the basic formation of the settlement network in many European countries, it also happened that a religious center was the factor behind the foundation of a village, and then a city. Fatima is worth mentioning here, established in ‘cruda radice’ around the site of Our Lady’s revelations in 1917. This small city has served 7–9 million pilgrims and tourists annually in recent years.

Under the influence of the pilgrimage center, a strong transformation of the spatial structure of already existing cities may also take place. The emergence of a sanctuary at a certain stage of a town’s development may cause far-reaching changes in the organization of the center’s space, as long as it is a dynamically developing sanctuary and its impact extends well beyond the borders of the region, or even the country. It is worth mentioning here the example of Lourdes, which was a little known town before the Marian revelations in 1858, serving as a local administrative and service center. As the result of the actions of the sanctuary, church policy, and widely publicized information about the revelations, both by the church and the media, already 50 years after the first revelations it was the most important Marian pilgrimage center in the world, visited by hundreds of thousands of pilgrims. The pilgrimage function of the city, which was also backed by the municipal authorities, caused a strong transformation of the urban structure, including the demolition of a number of houses and the construction of a new communication artery leading to the sanctuary. On previously undeveloped areas, the so-called lower town, a large pilgrimage district, the Grotto zone, was built with a strongly developed tourist infrastructure intended for visitors to the place of revelations. We observe a similar scenario of the development of San Giovanni Rotondo, a city famous for the sanctuary of St. Padre Pio, one of the most popular saints today. The expansion of the tourist infrastructure here runs in two ways, i.e., both in the historic part of the city and in the area of the pilgrimage center, where territorial resources make it possible to construct numerous buildings, mainly service facilities. Since the day of Padre Pio’s canonization in San Giovanni Rotondo, the construction of 120 hotels has started, which shows the scale of these transformation processes (

Giovine 2015).

A sanctuary may not only cause the creation of new areas in a city, but also change the development and functions of the existing districts. Highly renowned pilgrimage centers may displace other functions of the district, in which the pilgrimage function becomes the most important. This scenario generally concerns large, multifunctional cities, such as Cracow. In one of the districts of Cracow, in Podgorze, or more precisely in Łagiewniki and Borek Fałęcki, we currently have two large sanctuaries of international range, i.e., the Divine Mercy Sanctuary and the John Paul II Centre, still under development. The emergence of this sacred complex, and especially the strong development of the pilgrimage movement since the 1990s, has contributed to a change in the nature of the district, currently performing the pilgrimage function as the leading one. Following this, appropriate communication solutions are introduced, fundamentally changing the solutions in this area in the district, and thus in the city. Only commemorative plaques remind us of the old quarries and factories once present in these areas.

The city reactivation as a result of pilgrimage center is extremely rare. In this context, New Pompeii with the sanctuary of the Queen of the Holy Rosary can be mentioned. The ancient city was completely destroyed after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. At the end of the 19th century, as a result of the missionary activity of Bl. Bartolo Longo, New Pompeii began to emerge from the surrounding settlements. Striving for the religious revival of the local population, he promoted the cult of Our Lady of the Rosary. Residential infrastructure and other public utility buildings developed around the church built from social donations. In 1927, New Pompeii received the status of an independent commune.

3.1.2. Meso-Scale Impact on City Space

The term meso-scale impact is defined as the presence in a city of places and institutions that are thematically or functionally related to the pilgrimage center, located in other parts of the city, outside the zone of direct impact of the sanctuary (

Figure 2). These can be sacred buildings, places related to people and events important for the sanctuary, museums and religious exhibitions, as well as tourist facilities. Institutions functionally related to the pilgrimage center are primarily religious associations and organizations. This type of impact is not common and is more often observed in small urban centers which are large pilgrimage centers at the same time. In Fatima, approx. 2 km from the sanctuary, in Aljustrel—the home town of the visionaries Lucia, Francisco, and Jacinta)—a sacred and service zone complementary to the pilgrimage center was created. In addition, the monumental, so-called Great Stations of the Cross were established. In Lourdes, apart from the pilgrimage district clearly formed around the sanctuary, two large complexes serving pilgrims were established, i.e., the town of Cité Saint Pierre and the Youth Village. Cité Saint Pierre started to function in 1995 on an area of 32 ha. Six infrastructure buildings were built there, which can accommodate 500 people at a time. The Youth Village was built in 1988, in the middle of the forest, on the site of a former French Scout camp. Every year, several thousand young people from many countries of the world stay here.

The presence in the urban space of objects (or their complexes) thematically related to the sanctuary is important from the point of view of the development of the city and the pilgrimage center. It can lead to the activation of pilgrims, and thus enlarge their activity in the city. This, in turn, may increase the duration of pilgrims’ stay and, taking into account the multiplier effects, it may increase the city income and the state of the economy. That is why the influence of a pilgrimage center on a meso scale is so important for smaller cities, which primarily perform the pilgrimage function. The impact on a meso scale depends not only on a sanctuary’s hosts, but also on the activity of other entities, especially church and city authorities. In recent decades, owing to the development of religious tourism, many cities, including large ones, have marked out tourist routes based on religious potential and linked them to sanctuaries. In San Giovanni Rotondo, the city authorities took the initiative to attract pilgrims from strictly the area of the sanctuary to the historic city center. For this purpose, since the 1990s, the churches located in it began to be restored and promoted, emphasizing not only their religious and historical values, but above all their connections with St Padre Pio. In Lourdes, as part of the celebration of the 150th anniversary of the revelations, a special thematic path ‘In the Footsteps of St Bernadette’, and in Cracow, in order to arouse interest of those coming to the Divine Mercy Sanctuary and the John Paul II Centre in other tourist areas of the city, the route of St Faustina and the route of St John Paul II were created.

Pilgrimage centers may also affect the location of tourist facilities in parts of the city. Among the visitors to pilgrimage centers, there are also those who are looking for silence and want to spend time in concentration, away from the bustling zone filled with numerous hotels, restaurants, and shops.

Another effect of the impact of a pilgrimage center on a city on a meso scale may be a greater concentration of religious institutions, mainly religious congregations and associations. Some of the monasteries run retreat houses and provide accommodation services for pilgrims (e.g., in Fatima, Czestochowa, Cracow, Tuchow, and Zakopane). The presence of monastic facilities also favors the creation of educational institutions run by the church in the city (e.g., in Pompeii). Thus, the impact of a pilgrimage center on a city can be multifaceted, directed not only at the pilgrims arriving at the city, but also directly on its residents (thus, it is also an endogenous impact).

The presence of a pilgrimage center in a city may also lead to the development of infrastructure related to a specific group of pilgrims. In recent years, most attention—not only in pilgrimage centers—has been given to the sick and the disabled, and it results in adapting, e.g., railway stations, airports, or parking lots.

3.1.3. Micro-Scale Impact on City Space

Changes on a micro scale are the most common changes resulting from the existence and development of a pilgrimage center. Their effect is the development of a service zone around the sanctuary, adapted to serve pilgrims. However, this zone is relatively small, with a poorly developed tourist infrastructure, limited to a few or a dozen or so facilities (

Figure 2). It is usually located in the streets or street adjacent to the pilgrimage center. We observe such a model of impact of a pilgrimage on a city in the following cases:

In small sanctuaries, most often of regional range;

Accumulation of tourist infrastructure within the pilgrimage center;

As a certain transitional stage in the development of the pilgrimage center and the sanctuary service zone;

Lack of adequate territorial facilities in the vicinity of pilgrimage center;

Low activity of the entities administering the pilgrimage center and city, the residents.

Since the impact on a micro scale is limited mainly to the formations of sanctuary service zones, this issue will be discussed in detail in the manuscript’s next sub-section.

3.2. Sanctuary Service Zones

The most visible manifestation of the impact of a pilgrimage center on the urban landscape is the emergence of a zone around it, serving pilgrims and tourists. It is primarily of a service and commercial nature, but can also be filled with objects of religious character. However, also in the case of the religious function of objects functioning in this zone, such as seats of religious congregations, they often provide tourist services for pilgrims, e.g., by providing accommodation. Historically, the zones in question have emerged for two main reasons:

Necessity to strictly separate the sacred and profane zones, justified by religious requirements;

Visitor needs other than spiritual or religious.

The separation of the sacred zone from the profane zone is related to the very idea of a sacred place, i.e., one dedicated to God (a deity), where appropriate rituals and rules of behavior apply. The separation of the sacred space took place both realistically by establishing the boundaries of the sanctuary, and symbolically by the performance of cleansing rites by the people arriving. Referring to the biblical description of Jesus’s anger seeing merchants in the Jerusalem temple, for centuries attempts have been made to avoid any gainful activity in their area as unworthy of such places and offensive to God. The sphere of such activities was situated outside the walls of the pilgrimage center.

On the other hand, for the pilgrimage center visitors, especially arriving from afar, and spending a longer time in the city, a natural need was to provide a place to sleep, eat, and buy souvenirs. It favored the development of tourist and commercial facilities. However, it should be noted that even in the Middle Ages, stalls with devotional items, souvenirs, or jewelry were most often put up near the temple. Pilgrims spent nights away from the pilgrimage center, often on the outskirts. This was the case, for example, in Santiago de Compostela, where in the 10th century, owing to the growing importance of the sanctuary, urbanization processes in suburban settlements began (e.g., Lucio, Pinario). At the beginning of the 12th century, along with the construction of the new cathedral, the adjacent areas began to be developed, numerous shops and currency exchange points were built and, in the previously undeveloped areas, residential houses and facilities for pilgrims were constructed. This pattern was repeated over centuries in large pilgrimage centers, with urban development providing a commercial infrastructure expanding around the sanctuary.

However, the model that has been in force for centuries has undergone fundamental changes in modern times, especially since the 1980s. Undoubtedly, these changes were based on social transformations and, with them, patterns of religious devotion and the perception of a holy place (

Sołjan and Liro 2020). Currently, in numerous pilgrimage centers, the presence in the strictly sacred zone of typical tourist infrastructure, with pilgrimage houses, gastronomic establishments, and commercial points, is increasingly often marked. This leads to inhibiting the development of sanctuary service zones, because their functions are taken over by pilgrimage centers. The problem is significant because in the described situation, it is not only about changing the entity generating economic profits, since it is also in sanctuary service zones that church authorities often owned many facilities, but about a paradigm shift, a qualitative change of the essence of the holy place and, in this context, the pilgrimage center. What has been forbidden and stigmatized so far for religious reasons and motives is slowly becoming a new norm. Commercialization enters pilgrimage centers increasingly from sanctuary service zones. Owing to the processes presented above, the formation of sanctuary service zones is not observed in the vicinity of many modern and dynamically developing pilgrimage centers, or their development is minimal.

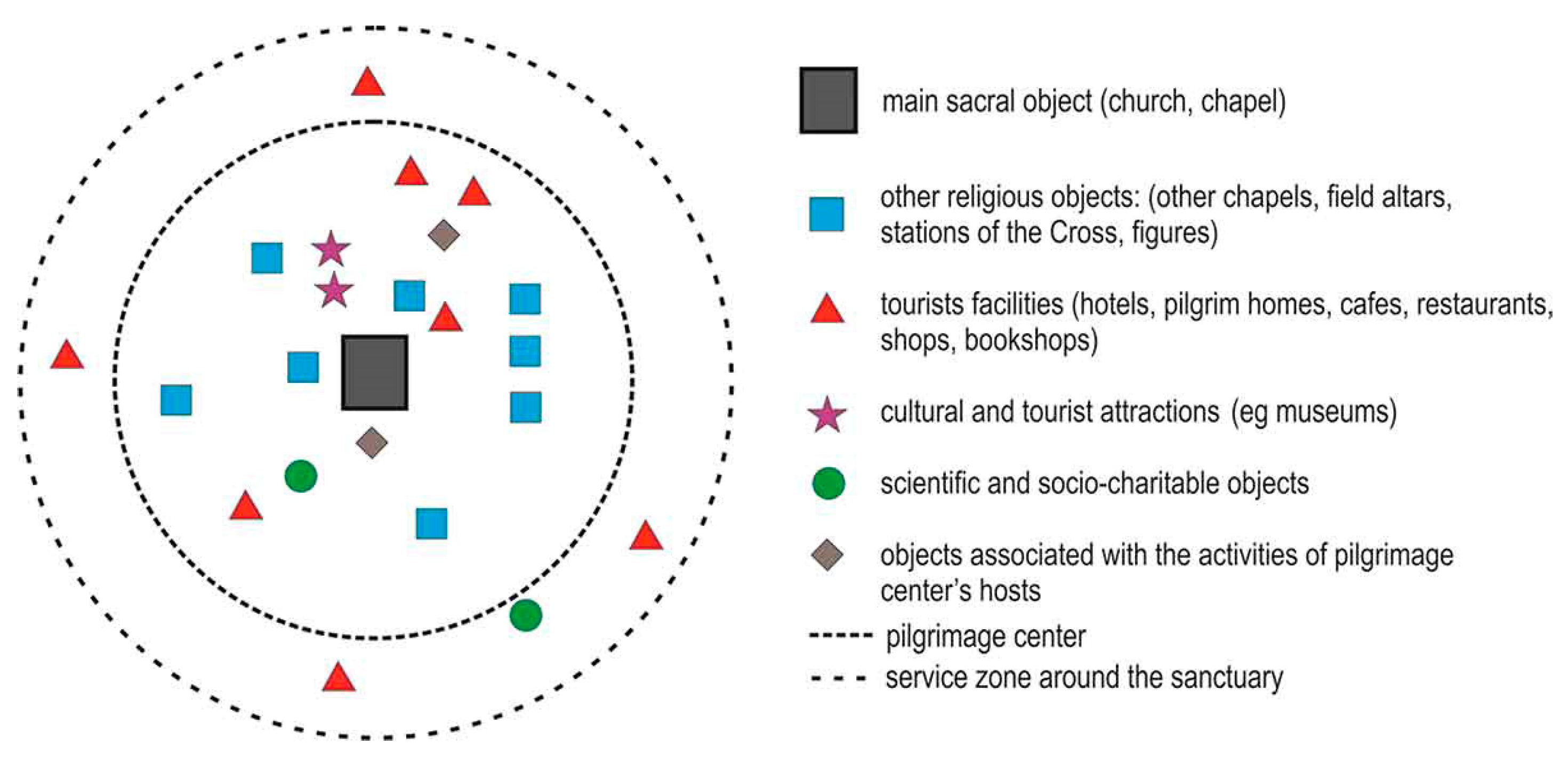

Since so far in the state of knowledge, sanctuary service zones have not been defined or terminologically determined, we propose to assume that a sanctuary service zone is one that develops directly around the pilgrimage center, functionally complementary to it, developing within a radius of approx. 1000 m and performing primarily service functions for pilgrims and tourists.

The distinctive features of a sanctuary service zone include the presence of tourist infrastructure, which makes it possible to satisfy the needs of pilgrims. These are accommodation facilities, catering establishments, and commercial points (mainly shops with devotional items and souvenirs). Owing to the religious dimension of the pilgrimage center, sanctuary service zones are often also characterized by other features, which, however, are not necessary for their existence (

Figure 2). These can include

The presence of religious orders and seats of other religious movements and associations, often providing services also for pilgrims;

The presence of museums and other cultural institutions, the subject matter and activities of which are related to the sanctuary;

The presence of infrastructure intended for sick and disabled pilgrims;

The religious nomenclature of streets, squares, and objects occurring in it.

An important prerequisite for the efficient functioning of sanctuary service zones is also the accessibility of pilgrimage centers in terms of communication accessibility and communication solutions inside them.

The designation of sanctuary service zones was based on two criteria:

a. The morphological structure of the area, including all service facilities and other objects and institutions serving pilgrims;

b. The range of the area of pilgrim activity, the area outside the pilgrimage center. This area was designated by drawing the isochrones of pedestrian access to the sanctuary along the main communication routes leading to it. The 15 min isochrone of walking to the pilgrimage center was adopted as the maximum (

Sołjan 2012). Based on the conducted surveys and polls in the analyzed pilgrimage centers (

Sołjan 2012), the maximum range of sanctuary service zones was assumed at 1000 m, and the service infrastructure for pilgrims in this area was analyzed.

The areas around pilgrimage centers can be developed in various ways and their nature can also be different. Sometimes, it is only a single object, e.g., a pilgrim’s house, a shop with devotional items, or a restaurant. A noticeable regularity in sanctuary service zones is the increasing concentration of commercial services, especially shops with religious items, as they approach the pilgrimage center (

Rinschede 1988,

1995). The size of the zones varies. They usually stretch along the main communication routes at a distance of 300–500 m (at most 1000 m) from the borders of the pilgrimage center (

Sołjan 2012).

Before the characteristics of sanctuary service zones will be discussed, it is worth emphasizing that in the case of many pilgrimage centers, the above-mentioned zones are not formed at all and no changes are observed. Such a state may result from the two most common scenarios:

- I.

This is typical of pilgrimage centers of lesser range, where the the number of visitors throughout the year or the pilgrimage season is small and irregular. The emergence of even a small sanctuary service zone requires systematic pilgrimage movement and a relatively constant number of visitors throughout the year. The lack of a sanctuary service zone in smaller pilgrimage centers is associated with the short stay of pilgrims in them, and, certainly, has economic consequences. For many pilgrimage centers of regional range and almost all centers with a smaller range, the lack of the discussed sanctuary service zone is typical, or there is only a single facility there. In the latter case, it will be the initial sanctuary service zone.

- I.

Sanctuary service zones do not develop in the vicinity of large pilgrimage center complexes with a very extensive and varied infrastructure, as was discussed earlier.

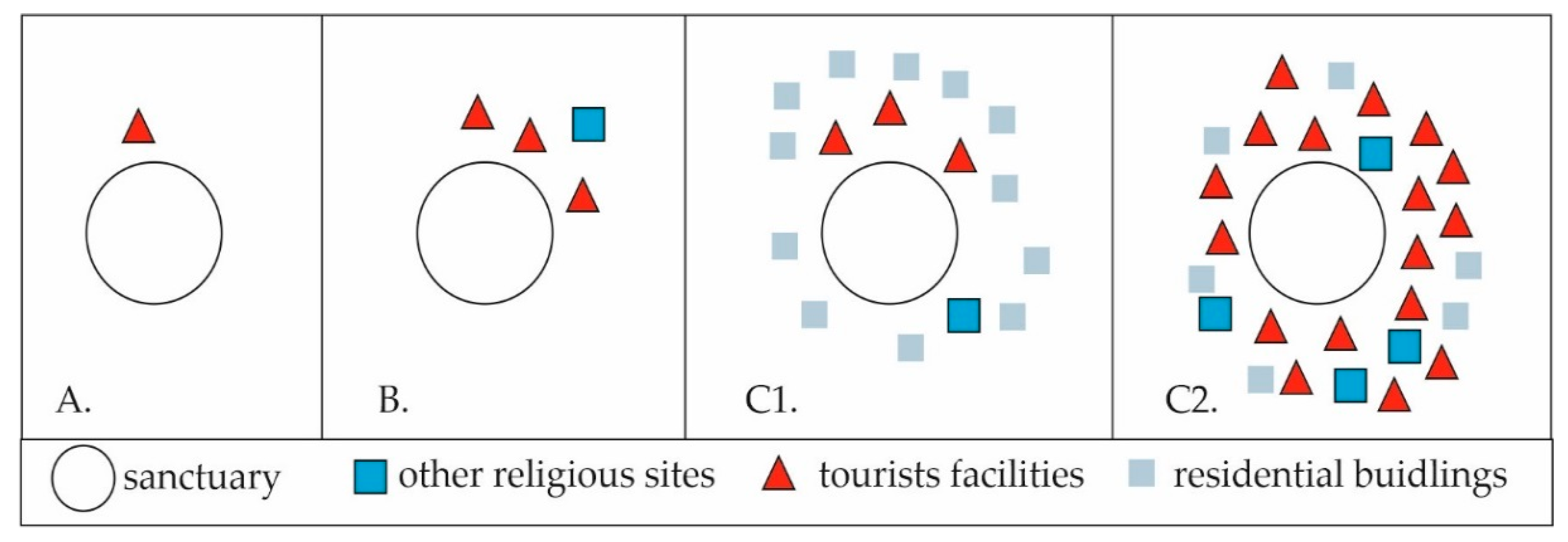

Depending on the way the space around the pilgrimage center and the functions accumulating in sanctuary service zones are organized, they have the following character (

Figure 3):

Initial—only with individual facilities for pilgrims;

Mixed (dispersed);

Compact, specialized only in serving pilgrims, with the following subtypes that can be distinguished here: C1—compact linear zones; C2—pilgrimage districts.

In initial sanctuary service zones (

Figure 3A), there is only a single service facility related to the pilgrimage center, typically with a smaller range, especially if these facilities are not present within the pilgrimage center itself.

In mixed (dispersed) zones (

Figure 3B), the facilities characteristic of the zone are integrated into the urban development, and functions related to the service of pilgrims coexist with other urban functions. In the landscape of such zones, facilities serving pilgrims are intertwined with facilities for other purposes, most often residential or public buildings, e.g., municipal institutions or educational facilities. The buildings that exist here are usually of dual purpose, with their lower floors occupied by commercial premises, i.e., shops with devotional items, restaurants, and cafés, with the upper floors intended for residential purposes. The mixed sanctuary service zone is the most common zone in large pilgrimage centers. It is characteristic of cities where the pilgrimage center was or is located in the city center, and the spatial development of the city was closely related to it. The city developed around the sanctuary along with (and often much later) pilgrimage infrastructure.

Compact sanctuary service zones (

Figure 3(C1,C2)) are observed in the two most common cases: when they are small and cover the nearest area adjacent to the pilgrimage center, most often a street (or even a part of it) or a square, or when they occupy such a large area that they constitute a separate district. A small, compact sanctuary service zone was created, among others, in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska and in Syracuse. A similar zone exists in Cracow-Łagiewniki, which is now starting to transform into a mixed zone. Fatima and Lourdes are typical pilgrimage districts among the surveyed contemporary sanctuaries. A similar district is increasingly visible in San Giovanni Rotondo. Hotel buildings of various sizes and standards are a characteristic type of development in pilgrimage districts. The mentioned San Giovanni Rotondo (especially the part around the sanctuary) has remained a great construction site since Padre Pio’s beatification in 1999 and canonization in 2002. The first hotel in Fatima was opened in 1929, and now there are over 50 of them, almost 40 of which are in the pilgrimage district (

Sołjan 2012). While new hotels are still being built in San Giovanni Rotondo and Fatima, the hotel base in Lourdes has been stable in recent years, especially in the area near the pilgrimage center.

The hotel infrastructure in the zones in question is complemented by other accommodation facilities belonging mainly to church entities (to sanctuary, religious orders, or associations). Fatima is the leader in this aspect, with accommodation services provided by many monastic houses. A well-developed accommodation base can also be found in mixed zones (e.g., Czestochowa and Loreto). The church facilities are a big competition for other facilities.

Apart from the actual areas of sanctuaries, sanctuary service zones are the most significant example of the organization of urban space determined by the pilgrimage function. This is due both to the concentration of facilities and services for pilgrims, unprecedented in other parts of the city, and to the exceptional volume of pilgrimage movement there.

The religious nature of the zones is emphasized by the names of the streets or facilities that are typically religious or otherwise related to the sanctuary.

A noticeable change taking place today in the zones is the appearance of hotel facilities of an increasingly higher standard (e.g., in Lourdes, Fatima, San Giovanni Rotondo, and Czestochowa). At the same time, the number of uncategorized and lowest standard hotels (one- and two-star hotels) is decreasing.

All sanctuary service zones are fairly uniform in terms of the services provided for pilgrims, primarily those related to accommodation and catering. They may be supplemented by photo points, post offices, banks, and ATMs. Additionally, commercial facilities have a very narrow profile of activity. Apart from the numerous shops with devotional items with a fairly wide assortment, there are also jewelry shops with wares traditional for a given region, and bookshops. General grocery shops and chemist’s shops are rare.

The infrastructure for the sick and the disabled is not sufficiently developed in all sanctuary service zones (Lourdes is an exception).

Apart from the size of the pilgrimage movement, environmental conditions are a decisive factor in the development and shape of sanctuary service zones. A pilgrimage district may develop, if there is large undeveloped space around a sanctuary, as was the case in Lourdes, Fatima, San Giovanni Rotonto, and the two analyzed sanctuaries in Cracow.

The presented zones are of a conceptual nature. In fact, there are zones with a much more complex structure and difficult-to-define boundaries. This is especially the case when the pilgrimage center itself has open borders—for example, in the case of Altötting, where there is a clear overlap between the sanctuary and the sanctuary service zone. It is worth noting that even among the international and national centers selected for the analysis, there are two, Paris and Levoča, in which a sanctuary service zone has not developed at all. An atypical sanctuary service zone may also be created when a sanctuary is located at a short distance from an object of high tourist attractiveness (in Syracuse and Cracow). This mainly applies to cities with a developed tourist function. This zone serves both pilgrims and tourists, so it partially loses the features typical of a sanctuary zone.