Are Roadside Crosses in Poland a Religious or Cultural Expression?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

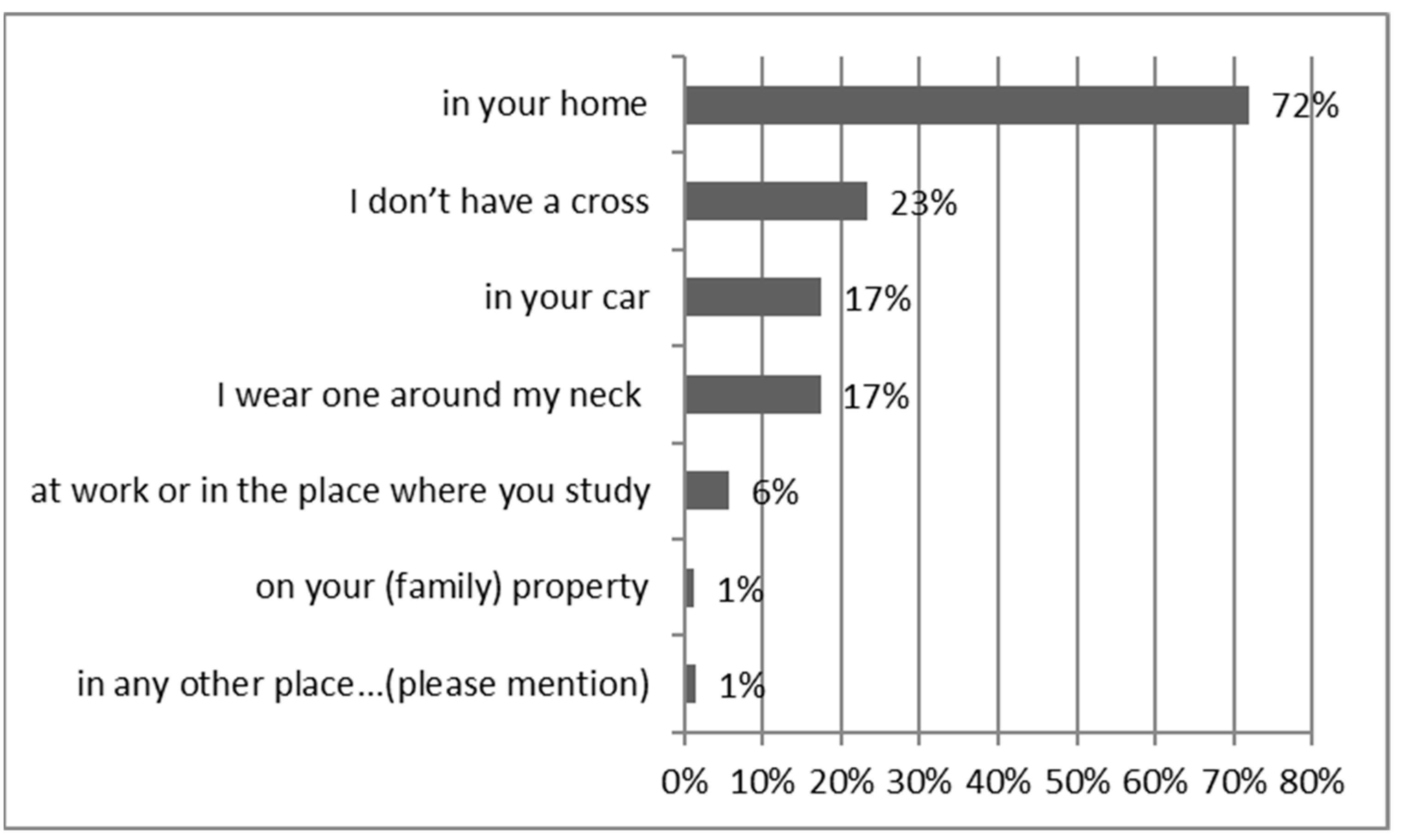

3. Literature Review on the Widespread Use of the Cross in Roadside Memorialisation

Crosses in Polish Roadscape

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Roadside Crosses Questionnaire

References

- Adamowski, Jan, and Marta Wójcicka, eds. 2011. Krzyże i kapliczki przydrożne jako znaki społecznej, kulturowej i religijnej pamięci [Wayside Crosses and Chapels as Social, Cultural and Religious Signs]. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS. [Google Scholar]

- Bednar, Robert M. 2013. Killing memory. Roadside Memorial Removals and the Necropolitics of Affect. Cultural Politics 9: 337–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, Lauren Jennifer. 2006. Silenced Voices. Experiences of Grief Following Road Traffic Crashes in Western Australia. Ph.D. dissertation, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Brien, Donna Lee. 2014. Forging continuing bonds from the dead to the living: Gothic commemorative practices along Australia’s Leichhardt Highway. Journal of Media and Culture 17. Available online: http://journal.media-culture.org.au/index.php/mcjournal/article/view/858 (accessed on 29 December 2017).

- Byrd, Rachael M. 2016. Rest in place: Understanding traumatic death along the roadsides of the Southwestern United States. Arizona Anthropologist 26: 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, Jose. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, Anthony, and Richard Tay. 2008. An Assessment of Roadside Memorial Policy and Road Safety. Canadian Journal of Transportation 2: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cicharska, Aleksandra. 2019. Social and demographic changes and their influence on space management. In Space Management. Interdisciplinary Approach. Evidence from Poland. Edited by Grażyna Chaberek. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego, pp. 143–63. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Jennifer. 2008. Challenging motoring functionalism. Roadside memorials, heritage and history in Australia and New Zealand. Journal of Transport History 29: 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Jennifer, and Ashley Cheshire. 2004. RIP by the roadside: A comparative study of roadside memorials in New South Wales, Australia, and Texas, United States. Omega: The Journal of Death and Dying 48: 203–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Jennifer, and Majella Franzmann. 2006. Authority from Grief, Presence and Place in the Making of Roadside Memorials. Death Studies 30: 579–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Erik. 2012. Roadside memorials in Northeastern Thailand. Omega. Journal of Death and Dying 66: 342–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Charles O., and Charles D. Rhine. 2003. Roadside memorials. Omega: The Journal of Death and Dying 47: 221–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, George E., and Heath C. Hoffmann. 2010. Roadside memorial politics in the United States. Mortality 15: 154–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1987. The Sacred and the Profane. The Nature of Religion. Orlando-London: Hardcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, Holly. 2000. Roadside crosses and Memorial Complexes in Texas. Folklore 111: 91–118. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, Holly. 2002. Roadside Crosses in Contemporary Memorial Culture. Denton: University of North Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gajewska, Małgorzata, and Piotr Pawliszak, eds. 2012. Polisemia krzyża w praktykach społeczeństwa polskiego [Multivocality of cross in Polish society practice]. Miscellanea. Anthropologica et Sociologica 13. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Barbara. 2017. The Material Culture of Remembrance in Ireland. Roadside Memorials as Contested Spaces. In Public Performances: Studies in the Carnivalesque and Ritualesque. Edited by Jack Santino. Logan: Utah State University Press, pp. 239–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Dorota. 2016. W poszukiwaniu miejsca. Chrześcijanie LGBT w Polsce [In Search for Place. LGBT Christians in Poland]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo IFiS PAN. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, Kate V., and Kevin M. Dunn. 1998. Roadside Memorials: Interpreting New Deathscapes in Newcastle, New South Wales. Australian Geographical Studies 36: 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henzel, Cynthia. 1991. A Cultural Geography Analysis and Interpretation of Roadside Shrines in Northeast Mexico. Master’s thesis, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, David. 2001. Religion and the ‘Great Transformation’ in Poland and East Germany. In Religion and Social Transformations. Edited by David Herbert. Ashgate: Aldershot-Burlington-Singapore-Sydney, pp. 13–63. [Google Scholar]

- Janicka-Krzywda, Urszula. 1999. Kapliczki i krzyże przydrożne polskiego Podkarpacia [Wayside Chapels and Crosses of Polish Carpathia]. Warszawa: Towarzystwo Karpackie. [Google Scholar]

- Klaassens, Mirjam, Peter Groote, and Paulus P. P. Huigen. 2009. Roadside memorials from a geographical perspective. Mortality 14: 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassens, Mirajm, Peter D. Groote, and Frank M. Vanclay. 2013. Expressions of private mourning in public space: The evolving structure of spontaneous and permanent roadside memorials in the Netherlands. Death Studies 37: 145–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klima, Ewa. 2011. Przestrzeń religijna miasta [City’s Religious Space]. Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego. [Google Scholar]

- Kulczyńska, Katarzyna, and Natalia Marciniak. 2018. Miejsca nagłej śmierci w Poznaniu—ich typologia i formy upamiętnienia [Places of sudden deaths in Poznań—their typology and forms of commemoration]. Rozwój Regionalny i Polityka Regionalna 44: 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek, Monika. 2019. Sekularyzacja czy może pluralizm i indywidualizacja? Rozważania o charakterze religijności Polaków (na przykładzie badań) [Secularization or maybe pluralism and individualisation? The reflections on the religiosity of Poles (on the example of research)]. Przegląd Religioznawczy 3: 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nešporová, Olga. 2011. Private Grief in Public Space: Roadside Memorials in the Czech Republic. In Dying and Death in 18th-21st Century Europe. Edited by Marius Rotar and Adriana Teodorescu. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 331–50. [Google Scholar]

- Nešporová, Olga. 2015. Pomníčky u Silnic v Longitudinální Perspektivě. Český Lid 102: 173–98. [Google Scholar]

- Nešporová, Olga, and Irina Stahl. 2014. Roadside memorials in the Czech Republic and Romania: Memory versus religion in two European post-communist countries. Mortality 19: 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, Maida. 2011. Louisiana Roadside Memorials: Negotiating an Emerging Tradition. In Spontaneous Shrines and the Public Memorialization of Death. Edited by Jack Santino. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 119–45. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Chris C. 1994. Sacred Worlds. An Introduction to Geography and Religion. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Petersson, Anna. 2009. Swedish Offerkast and Recent Roadside Memorials. Folklore 120: 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylska, Lucyna. 2015. Memorial crosses in Poland: a commonplace and contested element of public roads. Geografie 120: 507–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylska, Lucyna. 2016. Roadside memorial crosses in Poland: A form of sacralization of public spaces. Siedlungsforschung. Archäologie Geschichte Geographie 33: 245–64. [Google Scholar]

- Przybylska, Lucyna. 2020. Forms and the Role of Roadside Memorials in the Gdańsk Agglomeration, Poland. In Baltic Region—The Region of Cooperation. Springer Proceedings in Earth and Environmental Sciences. Edited by Grennady Fedorov, Alexander Druzhinin, Elena Golubeva, Dmitry Subetto and Tadeusz Palmowski. Cham: Springer, pp. 217–26. [Google Scholar]

- Przybylska, Lucyna, and Małgorzta Flaga. 2019. The anonymity of roadside memorials in Poland. Mortality 25: 208–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylska, Lucyna, Justyna Liro, Grażyna Holly, and Ewa Klima. 2019. Inscriptions on roadside memorials in Poland. Death Studies 44: 419–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, Amanda. 2013. Private Memorials on Public Space: Roadside Crosses at the Intersection of the Free Speech Clause and the Establishment Clause. Nebraska Law Review 92: 124–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, Jon K., and Cynthia L. Reid. 2001. A cross marks the spot: A study of roadside death memorials in Texas and Oklahoma. Death Studies 25: 341–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowski, Łukasz. 2012. Niewidzialne miasto jako przestrzeń synkretyczna i kulisy życia społecznego. Na przykładzie sakralne. [Invisible city as syncretic space and backstage of social life. The case study of the sacred]. In Niewidzialne miasto [Invisible City]. Edited by Marek Krajewski. Warszawa: Fundacja Nowej Kultury bęc Zmiana, pp. 117–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sadłoń, Wojciech. 2016. Differentiation, polarization and religious change in Poland at the turn of 20th and 21st century. The Religious Studies Review 4: 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Santino, Jack. 2011. Introduction. In Spontaneous Shrines and the Public Memorialization of Death. Edited by Jack Santino. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Shiner, Larry E. 1972. Sacred Space, Profane Space, Human Space. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 40: 425–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, Irina. 2013. Sudden Death Memorials in Bucharest: Mortuary Practices and Beliefs in an Urban Context. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 92: 893–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, Irina, and Barry L. Jackson. 2019. Sudden death memorials in Bucharest: Distribution in time and space. Yearbook of Balkan and Baltic Studies 2: 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland. 2018. Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/statistical-yearbooks/statistical-yearbooks/statistical-yearbook-of-the-republic-of-poland-2018,2,19.html (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Tay, Richard. 2009. Drivers’ perception and reactions to roadside memorials. Accident Analyses and Prevention 41: 663–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, Richard, Anthony Churchill, and Alexandre G. de Barros. 2011. Effects of roadside memorials on traffic flow. Accident Analysis and Prevention 43: 483–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, Susan Margaret. 2017. Private Sorrow in the Public Domain: The Growing Phenomenon of Roadside Memorials. Ph.D. dissertation, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, Thomas A. 2010. Roadside Memorials in Five South Central Kentucky Counties. Master’s thesis, Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green, KY, USA. [Google Scholar]

| Fieldwork | |

| (Brien 2014; Byrd 2016; Clark 2008; Clark and Cheshire 2004; Clark and Franzmann 2006; Cohen 2012; Henzel 1991; Kulczyńska and Marciniak 2018; Przybylska 2016; Przybylska et al. 2019; Reid and Reid 2001) | |

| Fieldwork and other methods | |

| Mass media analysis | (Owen 2011; Przybylska 2015) |

| Interviews | (Everett 2000; Graham 2017; Klaassens et al. 2013; Klaassens et al. 2009; Nešporová 2011; Nešporová 2015; Nešporová and Stahl 2014; Przybylska and Flaga 2019; Stahl 2013; Stahl and Jackson 2019; Welsh 2017) |

| Mass media analysis and Interviews | (Zimmerman 2010) |

| Survey | (Przybylska 2020) |

| Interviews and survey | (Everett 2002; Hartig and Dunn 1998) |

| Other methods | |

| Mass media analysis | (Bednar 2013) |

| Experiment | (Tay et al. 2011) |

| Survey | (Churchill and Tay 2008; Dickinson and Hoffmann 2010) |

| Experiment and survey | (Tay 2009) |

| Interviews | (Breen 2006; Petersson 2009) |

| Law review | (Reid 2013) |

| In your life, the symbol of the cross is… | I believe in God % | I neither believe nor disbelieve in God % | I do not believe in God % | |

| important | 87 | 24 | 15 | |

| neither important nor unimportant | 10 | 53 | 20 | |

| unimportant | 2 | 24 | 66 |

| Roadside crosses are an expression of… | I believe in God % | I neither believe nor disbelieve in God% | I do not believe in God% | |

| the religiosity of the people displaying these crosses | 21 | 16 | 13 | |

| the custom of marking places of death with crosses in Poland | 29 | 40 | 55 | |

| both the religiosity of the people displaying these crosses and the custom of marking places of death with crosses in Poland | 50 | 44 | 31 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Przybylska, L. Are Roadside Crosses in Poland a Religious or Cultural Expression? Religions 2021, 12, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010008

Przybylska L. Are Roadside Crosses in Poland a Religious or Cultural Expression? Religions. 2021; 12(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010008

Chicago/Turabian StylePrzybylska, Lucyna. 2021. "Are Roadside Crosses in Poland a Religious or Cultural Expression?" Religions 12, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010008

APA StylePrzybylska, L. (2021). Are Roadside Crosses in Poland a Religious or Cultural Expression? Religions, 12(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010008