Abstract

This article presents a validation study of the short forms of the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS) in Romania, followed by an examination of religious individualism among Orthodox and Pentecostal Christians. In a first step, the validity and reliability of the short forms of the CRS, namely the Abrahamitic CRS-5 and the interreligious CRSi-7, are tested in Romania. In a second step, the differences in attitudes regarding calling—a Weberian concept—are examined between Orthodox and Pentecostal Christians in Romania. For these examinations, we used data from a survey conducted in Romania in 2018 (). The results show that the CRS performs well in the Orthodox () and Pentecostal subsamples (). Moreover, based on the applied confirmatory factor and path analyses, on the one hand, we propose that calling attitudes stand out among Pentecostal Christians compared to Orthodox Christians. On the other hand, the Orthodox Christians make more use of religious advisers (priests), hereby expressing a different individual religious attitude of preferring to be advised rather than called. Furthermore, path analyses suggest that calling has neither a direct nor an indirect effect on religiosity among the Orthodox Christians while Pentecostal Christians’ religiosity is not directly linked to an adviser but to calling. The gender of the respondents is identified as a factor that is, directly and indirectly, related to religiosity. The results are discussed in the frame of religious individualism.

1. Introduction

This study makes use of the concept of “religious individualism”. Taking into account the particular characteristics of both Orthodoxy and Pentecostalism Christianity, a few brief explanations are needed for further interpretations. Religious individualism is used in the text in the meaning of ideas, such as autonomy from a hierarchical religious community, personalization of religion, and religious identity which develops via personal experience with transcendence. Thus, religious individualism embraces the dynamics of religiosity—an individual characteristic—and not of the social interactions among the religioners.

1.1. Emerging Religious Individualism

Within the Protestant Church, the idea of religious individualism stems from the self-understanding as a common priesthood of the believers. In comparison to medieval Catholicism, the connection between priesthood and any form of prophethood acquires new valences in Protestantism, a fact highlighted by Weber (1963, pp. 46–47) in the Sociology of Religion: “the personal call is the decisive element that distinguishes the prophet from the priest. The latter lays claim to authority by virtue of his service in a sacred tradition, while the prophet’s claim is based on personal revelation and charisma. It is no accident that almost no prophets have emerged from the priestly class… The priest, in clear contrast, dispenses salvation by virtue of his office.”

According to Weber, Protestantism (particularly Calvinism) and Catholicism differ in one integral aspect. Protestantism is marked by the uncomfortable pressure, even anxiety, regarding damnation without the possibility of change through the priest or sacraments. This concept strongly contrasts Catholic ideas. Additionally, this inner tension is underlined by the doctrine of predestination, which generated the need for a systematic, rationalized and diligent ethical code of conduct for everyday issues: “The rationalization of the world, the elimination of magic as a means to salvation, the Catholics had not carried nearly so far as the Puritans (and before them the Jews) had done. To the Catholic, the absolution of his Church was a compensation for his own imperfection. The priest was a magician who performed the miracle of transubstantiation, and who held the key to eternal life in his hand. One could turn to him in grief and penitence. He dispensed atonement, the hope of grace, the certainty of forgiveness, and thereby granted release from that tremendous tension to which the Calvinist was doomed by an inexorable fate, admitting no mitigation. For him, such friendly and human comforts did not exist. He could not hope to atone for hours of weakness or of thoughtlessness by increased goodwill at other times, as the Catholic or even the Lutheran could. The God of Calvinism demanded of his believers not single good works, but a life of good works combined into a unified system. There was no place for the very human Catholic cycle of sin, repentance, atonement, release, followed by renewed sin. Nor was there any balance of merit for a life as a whole which could be adjusted by temporal punishments or the Churches’ means of grace.”

This new religious “status” implied a different path to salvation for every true believer. In this new system, salvation could solely be attained through true belief, without any direct “magical” help, with no need for the priest and sacraments, the Church, or even God (Weber 2005, p. 61). The rejection of any institutional intermediation went so far that even the most common funeral rituals and ceremonies were eradicated: “The genuine Puritan even rejected all signs of the religious ceremony at the grave and buried his nearest and dearest without song or ritual in order that no superstition, no trust in the effects of magical and sacramental forces on salvation, should creep in.” (Weber 2005, p. 61).

Moreover, it is clearly stated that “Combined with the harsh doctrines of the absolute transcendentality of God and the corruption of everything pertaining to the flesh, this inner isolation of the individual contains, on the one hand, the reason for the entirely negative attitude of Puritanism to all the sensuous and emotional elements in culture and in religion, because they are of no use toward salvation and promote sentimental illusions and idolatrous superstitions. Thus, it provides a basis for a fundamental antagonism to a sensuous culture of all kinds. On the other hand, it forms one of the roots of that disillusioned and pessimistically inclined individualism which can even today be identified in the national characters and the institutions of the peoples with a Puritan past, in such a striking contrast to the quite different spectacles through which the Enlightenment later looked upon men.” (Weber 2005, pp. 61–62).

In contrast to Lutheranism, a very obvious reference to religious individualism (the circumvention of the private confession) and inner isolation, Calvinism captures a radically new perspective towards a mundane life, in the sense that every believer should have increased their level of morality in the absence of the regular confession of sins (Weber 2005, pp. 62–63). Furthermore, in terms of guiding each life to salvation, Weber insisted on the fact that “In practice, this means that God helps those who help themselves. Thus, the Calvinist, as it is sometimes put, himself creates his own salvation, or as would be more correct, the conviction of it. But this creation cannot, as in Catholicism, consist in a gradual accumulation of individual good works to one’s credit, but rather in a systematic self-control which at every moment stands before the inexorable alternative, chosen or damned.” (Weber 2005, pp. 69–70). Therefore, this newly introduced religious perspective based on uncertainty and isolation was not seen as fatalism. On the contrary, it was seen as a psychological trigger and stimulus for a more diligent, rational, and systematic way of acting successfully in a mundane environment. In short, this presented the only way a believer could ensure his or her possible election (Holton 1985, p. 110).

Taking together the ideas of Max Weber, one can conclude that he considered that capitalism may have developed based on the new understanding of the position a believer has had toward God by adopting the concept of calling (German original: Berufung, the term is written in italic in the text for discrimination of the concept from any other English meaning). He appealed to the Pauline idea of calling, emphasizing one of the best-known Biblical references for the later Calvinist idea of predestination (Ghosh 2014, p. 233): “For many are called, but few are chosen.” (Matthew 22: 14).

For instance, the root of the term “Beruf” has a double meaning in its original German language. The first one relates to religious calling, while the second one stems from carrying out an economic profession (Ghosh 2014, p. 239). In this sense, Weber (2005, p. 63) stated that “Already with Luther, we found that work in a calling, within an economy with a division of labor, was derived from the ideal of “brotherly love”. However, what remained for Luther an unstable, purely conceptual construction became, for the Calvinists, a central component of their ethical system. “Brotherly love”, because it can only be in service to God’s glory and not to fulfill physical desires, is expressed primarily in the fulfillment of the tasks of a calling, tasks that are given by lex naturae (natural law). In the process, work in a calling becomes endowed with a peculiarly objective, impersonal character, one in the service of the rational formation of the societal cosmos surrounding us. The marvelously purposeful construction and furnishing of this cosmos, which is apparently designed to serve the usefulness of the human species (according to the revelation of the Bible as well as natural insight), in fact, allows work in the service of all impersonal, societal usefulness to promote the glory of God—and hence to be recognized as desired by Him.

Another noteworthy concept we have to deal with is humility. It was noted that Weber made a clear distinction between humility among Lutherans and calling in the case of Calvinists or between “asceticism-mysticism” (Zabaev and Prutskova 2019). Accordingly, Weber (2005, p. 58) stated that “the church fathers of Lutheranism took a firm stand on this doctrine: salvation can be lost (amissibilis), but it can be won back through penitent humility and faithful trust in the word of God and the sacraments.” Moreover, while humility “is commonly equated with a sense of unworthiness and low self-regard, true humility is a rich, multifaceted construct that is characterized by an accurate assessment of one’s characteristics, an ability to acknowledge limitations, and a ‘forgetting of the self’.” (Tangney 2002, p. 411). The same author underlines the six facets of humility: “the key elements of humility seem to include: an accurate assessment of one’s abilities and achievements (not low self-esteem, self-deprecation); an ability to acknowledge one’s mistakes, imperfections, gaps in knowledge, and limitations (often vis-a-vis a “higher power”); openness to new ideas, contradictory information, and advice; keeping one’s abilities and accomplishments—one’s place in the world—in perspective (e.g., seeing oneself as just one person in the larger scheme of things); a relatively low self-focus, a “forgetting of the self,” while recognizing that one is but part of the larger universe; an appreciation of the value of all things, as well as the many different ways that people and things can contribute to our world” (Tangney 2002, p. 413). Similarly, Powers et al. (2007) define humility as conduct that should promote the relinquishment of every haughty, conceited, arrogant, egotistical, and narcissistic trait in favor of a rational-objective observation of an individual in relation with other people, while implying respect and forgiveness. Other scholars found that humility or being humble is highly linked with positive psychology (Peterson and Seligman 2004), job performance (Johnson et al. 2011), the capacity to strengthen social relationships (Davis et al. 2013), the inner desire to accept criticism (Delbecq 2006), the ability to be more helpful (LaBouff et al. 2012), generous (Exline and Hill 2012), thankful to others (Dwiwardani et al. 2014) and, extremely important, cooperative (Hilbig and Zettler 2009). Therefore, humility emerges as another personal characteristic of believers which should at least facilitate or even support the adaptation to new situations without emphasizing the inner command to become active as in contrast to calling. Hence, humility is a further alternative for religious individualism for a believer according to a certain tradition of which Orthodoxy is one example.

Between Eastern Orthodoxy and Western religious paradigms, there are important differences in the sense that the first one also promotes salvation through humility, following the words of Paul: “This saying is trustworthy and deserves full acceptance: Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners. Of these I am the foremost.” (1 Timothy 1: 15) and “Nothing is to be done out of jealousy or vanity; instead, out of humility of mind everyone should give preference to others.” (Philippians 2: 3). Therefore, an Orthodox Christian may cultivate the virtue of considering himself/herself the worst among all. However, this is done with a pedagogical purpose, without any kind of despair. On the contrary, it is done with joy and hope in the face of a merciful, powerful, and omniscient God (Gassin 2001) and the belief that the ultimate task of a faithful person is life in the afterlife. Further, it underlines a dissonance between Eastern Orthodoxy and Western secular psychology based on the fact that the latter emphasizes justice and individual rights and not the spiritual act of forgiveness of the sinner (Gassin 2001).

Zabaev (2015) found that humility and obedience are essential moral ingredients that influence the economic thinking of Russian monastic Orthodoxy. In the Christian Orthodox tradition, humility, as well as the sense of regret over sin, play an important role in the way that a person enriches their spiritual life through purification and redemption (Chirkov and Knorre 2015).

Zabaev (2015, pp. 162–63) emphasized the aspect that “the specific character of Orthodoxy is that it regards not vocational or professional activities as a means to salvation, but obedience and humility in relation to a (spiritually) more experienced person or a person at a higher place in the hierarchy.” Such a person with a higher position in the hierarchy in the Orthodox church is represented by a priest. Thus, humility as a kind of conduct implies that its religious facet involves the omnipotence of an omniscient God (Templeton 1997). Interestingly enough, other scholars emphasized that humility can be compared to an open-minded perspective about life and salvation and a true desire to learn from mistakes (Hwang 1982).

1.2. Religious Individualism and Collectivism in Orthodox Christianity

Orthodox Christianity preaches the unity between salvation and the Church, as stated in the old Latin principle “Extra Ecclesiam nulla salus”. The Orthodox Church has been organized hierarchically since ancient times and transmitted its tradition, above all the revelation embedded in the human community, the Church (Stăniloae 1997, vol. 1). Different new religious denominations challenged the roles of priests; however, one can find verses from the Bible supporting the significance of the hierarchy, e.g. “And in the same way, let the younger men be ruled by the older ones. Let all of you put away pride and make yourselves ready to be servants: for God is a hater of pride, but he gives grace to those who make themselves low.” (1 Peter 5: 5).

The older ones are represented by the more experienced and educated believers who took the office to serve the community. Deacon David concludes on the legitimation of the priest by pointing to the fact that through the Holy Spirit, Jesus gave his Apostles the power to help correct sins and finally, to offer their forgiveness through Eucharist. This power was later passed on to the bishops and priests (David 1994, p. 278): “Then he breathed on them and said, Receive the Holy Spirit; If you forgive anyone’s sins, they will be forgiven. But if you don’t forgive their sins, they will not be forgiven.” (John 20: 22–23). Thus, in the Orthodox Church the priest is vested with the power to perform all of the Church’s holy mysteries. Moreover, in Matthew (28: 19), the priests’ mission is obvious: “Go then, and make disciples of all the nations, giving them baptism in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit”. Hence, the mission has been put in the hands of a legitimate individual but to build up a community. While building up is the first step, the maintenance of a religious community is always a threat by a division. In deacon David’s book (David 1994, p. 286), he sums up the teaching of the bible by saying that there should not be any division between the Church and priesthood, as was experienced by Jesus through His Apostles. After His Resurrection, Jesus instituted for all His teachings to be transmitted around the world and also that the believers should take care of the communion and not be divided by individual aspirations. A striking passage to this notion is written by Apostle Paul to the Corinthians: “For even as the body is one and yet has many members, and all the members of the body, though they are many, are one body, so also is Christ. For by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body, whether Jews or Greeks, whether slaves or free, and we were all made to drink of one Spirit. For the body is not one member, but many.” (1 Corinthians 12: 12–14).

Believers should consider that they have their path and freedom for salvation. Nonetheless, the path alone is not enough, efforts should only be assessed within the Body of Christ, the Church, and through the grace of the Holy Trinity (Stăniloae 1997, vol. 3). Thus, individuals’ efforts for salvation through faith and good deeds should be complemented with a regular and reasonable struggle to receive the benefits given by Holy Sacraments within the Church (Stăniloae 1997, vol. 2). A believer receives the grace of salvation which should, however, be further accompanied throughout life by spiritual effort, perseverance, and will. In sum, it is considered that Orthodox believers need to behave according to their faith and good deeds, to receive inside the Church, in community, the divine grace which, further, could be kept only through an active personal spiritual struggle and effort (Stăniloae 1997, vol. 2). Moreover, the priest has an important role in this process.

1.3. Hypotheses and Study Goals

The hermeneutical analysis so far has let us contrast two ideas. In the first place, Christian Orthodox tradition will rather let believers follow an authorized religious person even when they feel the calling of God. In the second place, Christian Protestant tradition will detach a believer from religious authorities and let him or her follow God’s calling rather than being guided by a religious leader. Therefore, we expect that for an Orthodox believer, a priest will play (directly and indirectly) a greater role than a pastor to a Protestant one. Conversely, calling for a Protestant will be more salient than for an Orthodox. Finally, we expect that the Orthodox have more humility, i.e., higher values than Protestants.

To analyze these hypotheses, we resort to the measurements of religiosity, humility and calling, and assessment of the presence of religious authority in the social realm of the believer. The variables are analyzed via path analyses, which means that path regression coefficients will be consulted to test the formulated hypotheses. In the present study, Orthodox Christians are represented by the Romanian Christian Orthodox parishioners and as an instance, for the Protestants, we aimed at the Romanian minority of Pentecostal Christian parishioners.

In brief, this study aims to validate the short forms of the Centrality of Religiosity Scale and explore the pathways of religious traditions of Orthodoxy and Pentecostalism in their effects on the religiosity of a believer. To achieve the goal, in the first step, the two short forms of the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS-5, CRSi-7, Huber 2012) are validated via factorial analysis. In a second step, the version that performs better is used for a path analysis of the religious traditions with the identified relevant religious and demographical variables.

2. Method

Throughout the method, results, and discussion sections, we will make use of specific abbreviations in the subscription, such as “Orth.” (with and without a capitalized “O/o”) and “Pent.” (with and without a capitalized “P/p”), to mark the Orthodox and Pentecostal Christians subsamples.

2.1. Sample

In total, 643 participants ( and ) from different Romanian counties in the East and North-East, such as Iași, Suceava, Botoșani, Bacău, Neamț, Vaslui, Vrancea, and Galați, were questioned for our analysis. From this total number, we analyzed only 547 participants ( and ). See Table 1 for more details on the demographic composition of the final sample. Some participants were excluded because we intentionally restricted the analyses to only those respondents who answered all CRS-5 items, the whole Calling-Scale, and the items on making use of religious advisers, as well as their advice on everyday issues.

Table 1.

The demographic composition of the sample in Romania for Orthodox and Pentecostal Christians.

The data were collected in 2017 and 2018 within the “Project on Religion and Economics in Russia, Georgia, Romania, and Switzerland”. The sample is a convenience sample, consisting of respondents who were neither pre-selected by any strategy nor part of a group of already available people, e.g., university undergraduates or social survey pools. While this type of sampling strategy bears the major problem of limiting the main results to the targeted Orthodox and Pentecostal subsamples provided in our analysis, we consider the main findings vital for interreligious studies between Orthodox and Pentecostal traditions.

The paper-pencil questionnaires were physically distributed and collected in parishes or churches by the research team members and assistants or through the support of priests and pastors. The questionnaires were completed following the ethical norms regarding the assurance of total anonymity and confidentiality. The reason for the survey was clearly emphasized to the interviewees, especially in the case of those belonging to a minority denomination, like Pentecostalism, who proved to be a little bit reserved towards the scientific investigation.

Most of the respondents live in urban areas (91%). Women represent 60.5% of the total sample. Moreover, 35.3% of the interviewees are currently students, 47.2% of the respondents live together with a spouse or partner, and 38% have one or more children.

In this sample, the mean age of Orthodox respondents was and within the Pentecostal subsample. In terms of the level of education, the Orthodox sample contains more individuals with higher levels of education in comparison to the Pentecostal one. Nonetheless, across the board, both groups had individuals with at least basic secondary up to academic education completed.

2.2. Instruments and Analyses

2.2.1. The Centrality of Religiosity Scales CRS-5 and CRSi-7

In the case of the Romanian samples, we refer to both the CRS-5 and CRSi-7 scales (Huber and Huber 2012). The CRS-5 is suitable for research in Abrahamitic contexts, i.e., Judaism, Islam, Christianity, whereas the CRSi-7 is designed to be applied within religious traditions that do not only acknowledge one God but many deities and different images of Gods, e.g., like in Hinduism or Buddhism to name a few. In short, all items on the CRS-5 are included in the CRSi-7, but not vice-versa.

The CRS is widely used in various studies related to religiosity (e.g., some recent publications, Zarzycka et al. 2020; Riegel 2020; Ackert et al. 2020a, 2020b; Esperandio et al. 2019; Huza 2018; Fradelos et al. 2018). The Centrality of Religiosity Scale has a comprehensive and economic way of assessing personal religiosity by including the dimensions associated with ideology, intellect, religious experience, private, and public religious practices. In the CRS-5, each of these five dimensions is linked to a particular item, while the CRSi-7 contains two additional items related to private practice (meditation along with prayer) and religious experience (participative along with interactive pattern). The items are formulated concerning the salience or frequency of the religious attitudes, experience, and behavior. The answers are given on 5 to 7-point Likert scales depending on the items (see Table A1 in Appendix A for more details) which are finally transformed to a 5-level scale according to the recommendations made by the authors (Huber and Huber 2012). After the transformation and recoding, the items have the same standard interpretation from low to high with a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 5. Therefore, the interpretation of the answers becomes straightforward with a higher score showing higher levels of the Centrality of Religiosity when condensed to an index.

2.2.2. Core Dimensions of the CRS

The dimension of ideology deals with the probability of the existence of transcendence. The item associated with it is “To what extent do you believe that God or something divine exists?”.

In terms of the intellectual dimension of religiosity, an individual who often thinks about religious issues is more predisposed to increase the stock of religious knowledge and, thus, to facilitate the ease of acquiring hermeneutical skills. Accordingly, the corresponding item is “How often do you think about religious issues?”.

When it comes to the dimension of religious experience, it is considered that a person who often feels or perceives the existence of God or something divine intervening in his or her life is more open to understand and practice religiosity. The associated question from the CRS-5 is: “How often do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that God or something divine intervenes in your life?”. Additionally, the CRSi-7 includes a further item for this dimension: “How often do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that you are one with everything?”.

The dimension of private practice concerns behaviors, such as prayer or meditation, aimed at connecting with something superior to worldly, material reality. If an individual uses such practices more frequently, then he/she is more connected with the divine. The corresponding question on the CRS-5 is: “How often do you pray?”, and “How often do you meditate?” on the CRSi-7.

The last dimension on the Centrality of Religiosity Scale concerns the public practice of religiosity. The more frequently a person participates in religious services, the more connected his/her religious life is with a social body. The associated item for this dimension is: “How often do you take part in religious services?”. The English–Romanian translations of the items of the CRS-5 and the CRSi-7 are presented in Table A1 in Appendix A.

2.2.3. CRS Index

The items of the CRS can be summed up in a unifying index. The CRS-5 index is the average score of all 5 items and can range from 1 to 5.

Two additional items are needed to compute the CRSi-7 index: “How often do you meditate?” and “How often do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that you are one with all?”. Therefore, the core dimensions of experience and private practice have two items each in the CRSi-7, rather than one item like the other dimensions. To compensate, only the item with the higher value is taken into account in further analysis. The CRSi-7 index is then calculated as the average of the remaining 5 values resulting in a possible range of 1 to 5. The authors of the scale proposed to divide the scores into 3 categories. Individuals with a score ranging from 1.00 to less than 2.00 are considered not religious, from 2.00 to 4.00 religious, and those with a score of 4.00 to 5.00 as highly religious. These three CRS index categories facilitate the description of the sample and comparisons concerning religiosity.

2.2.4. Translation of CRS

The translation of the original items of the CRS-5 into Romanian received special attention. Previously, Huza (2018) made the first attempt to translate the long version of the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS-15) into Romanian. The Romanian translation presented in this article differs from Huza’s in several ways. The changes mainly stem from the desire to address a model with a higher generality and a lower religious specificity related to concepts and terms of different religious traditions, therefore, making it more broadly applicable. We propose that the items are worded in a more general manner and can hence, not only be understood by the parishioners belonging to certain religious denominations but by any spiritual and religiously unaffiliated person.

Moreover, we took three requirements for the operationalization of the specific items of the CRS into consideration. The first one is based on the consideration that each of the five dimensions of the CRS should be extremely concise and precise. Secondly, one must take a crystal-clear distinction between indicators and different theological contents into account, to systematically analyze the distinct effects of these two components of religiosity. Finally, the third requirement concerns the general methodology of self-report measures in social sciences. From the initial scale construction on, one of the key aspects was the parsimoniousness of the scale (Huber 2003, pp. 228–30), which was considered in the present translation. Thus, the translation shown in Table A1 in Appendix A was done in an interactive consultation with the author of the scale to fulfill the requirements1.

2.2.5. Calling and Humility Scale

As shown in Table A2 of Appendix A, the scale for Calling and Humility consists of 25 specific items presenting different perspectives an individual can have towards economic exchange. The respondents were asked to rate various statements about characteristics of persons (Zabaev and Prutskova 2019), with answer options ranging from 1 to 6 (1—“very much like me”; 2—“like me”; 3—“moderately like me”; 4—“a little like me”; 5—“not like me”; 6—“not at all like me”; 99—“hard to answer”).

The Calling and Humility Scale has 4 distinct subscales, namely Calling, Humility, Careerism, and Ressentiment, nonetheless, in the path-analyses we only use the Calling subscale scores. In a preliminary data check, the Humility subscale has proven not useful in our sample as it did not distinguish between the two denominations and therefore was excluded from path-analyses . Thus, we renounce the description of the subscales calculation but report the items of it for transparency in Table A3 of Appendix A. The computation of the Calling subscale is an elementary average of its component items.

2.2.6. Questions on Religious Adviser and Advice

The survey included certain items particularly related to the practice of asking a priest or pastor for advice on everyday issues. Firstly, the respondents indicated by a dichotomous option (yes—1; no—0) whether they had a religious adviser. Secondly, they stated how often they seek advice on a 5-step scale (1—“never”, 2—“rarely”, 3—“occasionally”, 4—“often”, 5—“very often”, and 99—“hard to answer”). Besides the Calling scale, both previous items operationalize the concept of religious individualism, an element that was under investigation in this article.

A person who is with sincerity and consent attached to a priest or pastor, asking for real advice in different contexts, is naturally considered a religious one. With caution, it could be stated that such a person is attached to an exogenous factor and therefore, does not present the same values as an individualist person, understood in the Protestant way. More specifically, it is possible that a non-religious person would ask for religious services if he/she were superstitious and thought such a person could fulfill or accomplish various desires (winning a lottery or a better job) or emotional needs and expectations.

2.2.7. Demographic Variables

The survey included a set of demographic variables (i.e., gender, age, completed level of education, current educational status, main occupation, relationship status, marital status, number of children, cohabitation with the partner, and area of living). From this set, gender was chosen as an exogenous variable for personal religiosity in the path analyses by examining the results of the correlational analyses among the demographic and religiosity related variables.

2.2.8. Psychometric Properties of the CRS

Descriptive statistics (i.e., means and standard deviations) are reported along with the -equivalent reliability estimate of internal consistency, widely known as Cronbach’s alpha for the CRS-5 and the CRSi-7. Besides -equivalent reliability, McDonald’s omega () is conveyed as an estimate of congeneric reliability. The core dimensions of the scales are presented as bivariate correlations to demonstrate the inner associations of the scale’s indicators. The dichotomous variables of gender and the presence of a religious adviser are correlated by point-biserial correlations, while Bravais–Pearson correlations are calculated for the variables of Calling and the use of the advice with the total scores of the CRS-5 and the CRSi-7.

2.2.9. Confirmatory Factor Analyses

The CRS has undergone confirmatory factor analyses many times in different linguistic and cultural contexts (some recent examples: e.g., Esperandio et al. 2019; Huza 2018; Ackert et al. 2020a, 2020b). In Huza’s case, the CRS-15 was tested in Romania with 4 different confessions (Orthodox, Catholic, Pentecostal, and Seventh-day Adventist), whereby the Orthodox element comprised 68% of the total sample (). In the present study, the focus lies on both the Abrahamitic and the interreligious short forms, compared to the long Abrahamitic form used by Huza. This analysis supplements the previous and current empirical investigation with the analysis of the CRS in Romania.

The authors intentionally leave out the exploratory factor analysis of the short forms of the CRS in this study before the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) because of the empirical evidence of the one-factor model with the CRS-5 and the CRSi-7 in the literature (e.g., Ackert et al. 2020a, 2020b; Kambara et al. 2020). Nevertheless, the correlations of the core dimensions are reported and checked for suitability for the CFA. This means that they should be neither too high, which would signal collinearity, nor too low, so as not to indicate independence of the core dimension from each other.

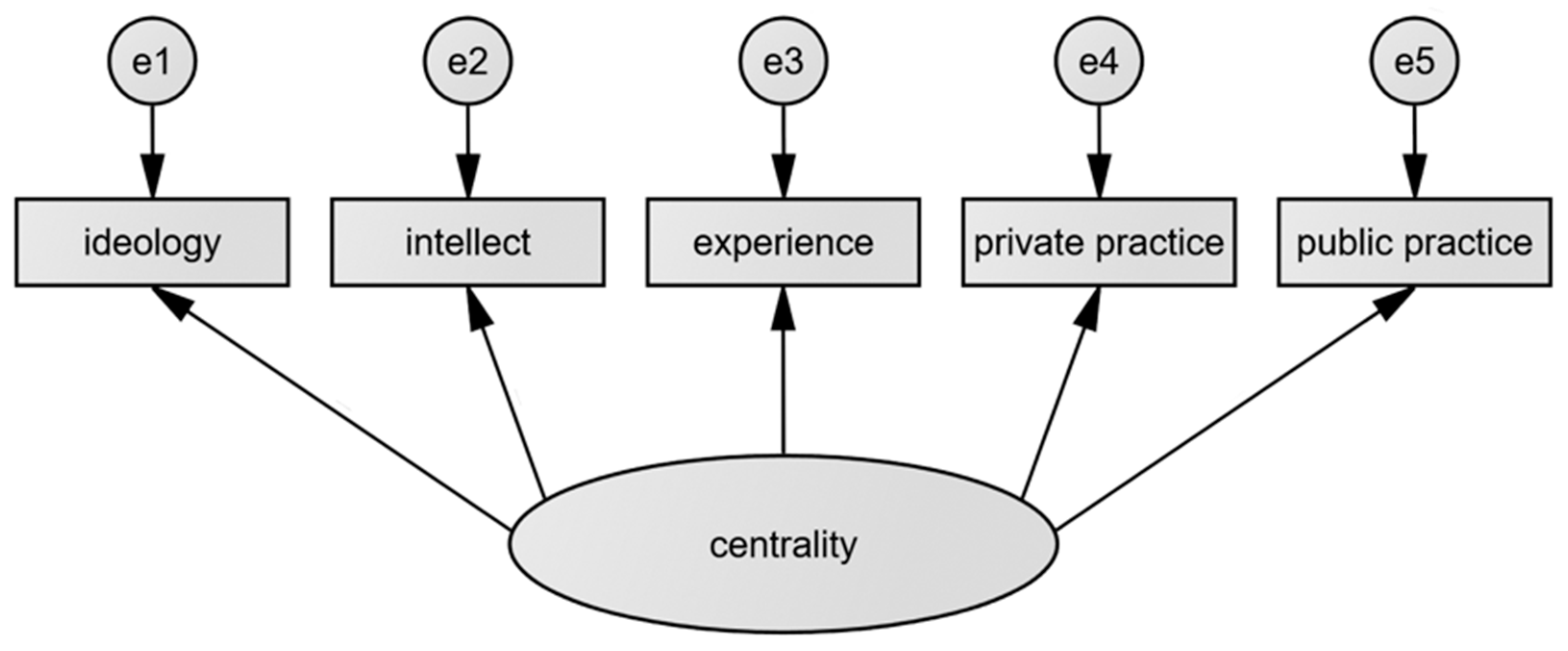

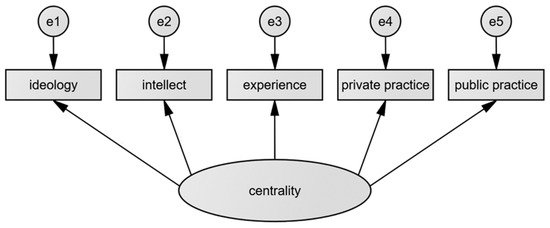

As the short forms both result in 5 manifest indicators with one per core dimension (ideology, intellect, experience, private, and public practice) and one latent variable of Centrality of Religiosity, the postulated models for the CRS-5 and CRSi-7 are built around the centrality, as a latent variable with 5 reflective indicators with uncorrelated residuals (see Figure 1 for a schematic depiction). The models are identified with the factor weight of public practice restricted to equal 1. Starting with a model with uncorrelated residual modification indices greater than per degree of freedom (which is round up to 4.00 for practical reasons) leads to an iterative model modification. Model modification is repeated until the global fit indices are met. The final models of the CRS-5 and CRSi-7 with the Orthodox and Pentecostal subsamples should comply with the recommendations by Hu and Bentler (1999). Thus, the CFI (Comparative Fit Index), the TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index), the RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation), the SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Residual) are examined to meet the following values: , , with a 90% confidence interval of and a non-significant closeness of fit test statistics (). The SRMR should be less than or equal to 0.08 (). Absolute, relative, and parsimony-related indices are combined to achieve a comprehensive, conservative, and reliable evaluation of the calculated statistical models.

Figure 1.

The scheme of the confirmatory factor analysis model of the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS) short forms. The rectangles show indicators, the circles depict residuals, the oval represents the latent variable, while the straight lines are regressions.

With a sample size of and in the subsamples, the non-significant -test () seems plausible. The reason for that is that the -test statistics are sensitive to sample size and, therefore, do not work as an absolute normed standard. Considering the -test statistics, the focus of the evaluation of the global model fit primarily lies in the characteristics listed above the -test.

Models are computed with raw data and the bootstrap procedure is applied in the CFA with a to obtain 90% bootstrap corrected confidence intervals for the parameter estimates. The confidence intervals are reported along with the point estimates throughout the result and discussion sections, where possible. The following designation with Greek letters is used in the result and discussion section: —factor loading, —with one-digit subscript for the variance of a residual and with two digits subscript for the covariance of residuals. Any statistical parameter linked to ideology receives an , intellect , experience , private practice , and public practice subscripts. For example, the correlation of the residuals of ideology and public practice will appear as in the text sections.

The analyses are run with the IBM SPSS (version 27) and AMOS (version 26) software packages. The calculations of the scale reliability are done with the “psych”-package (Revelle 2020) in R (R Core Team 2020).

2.2.10. Path Analyses

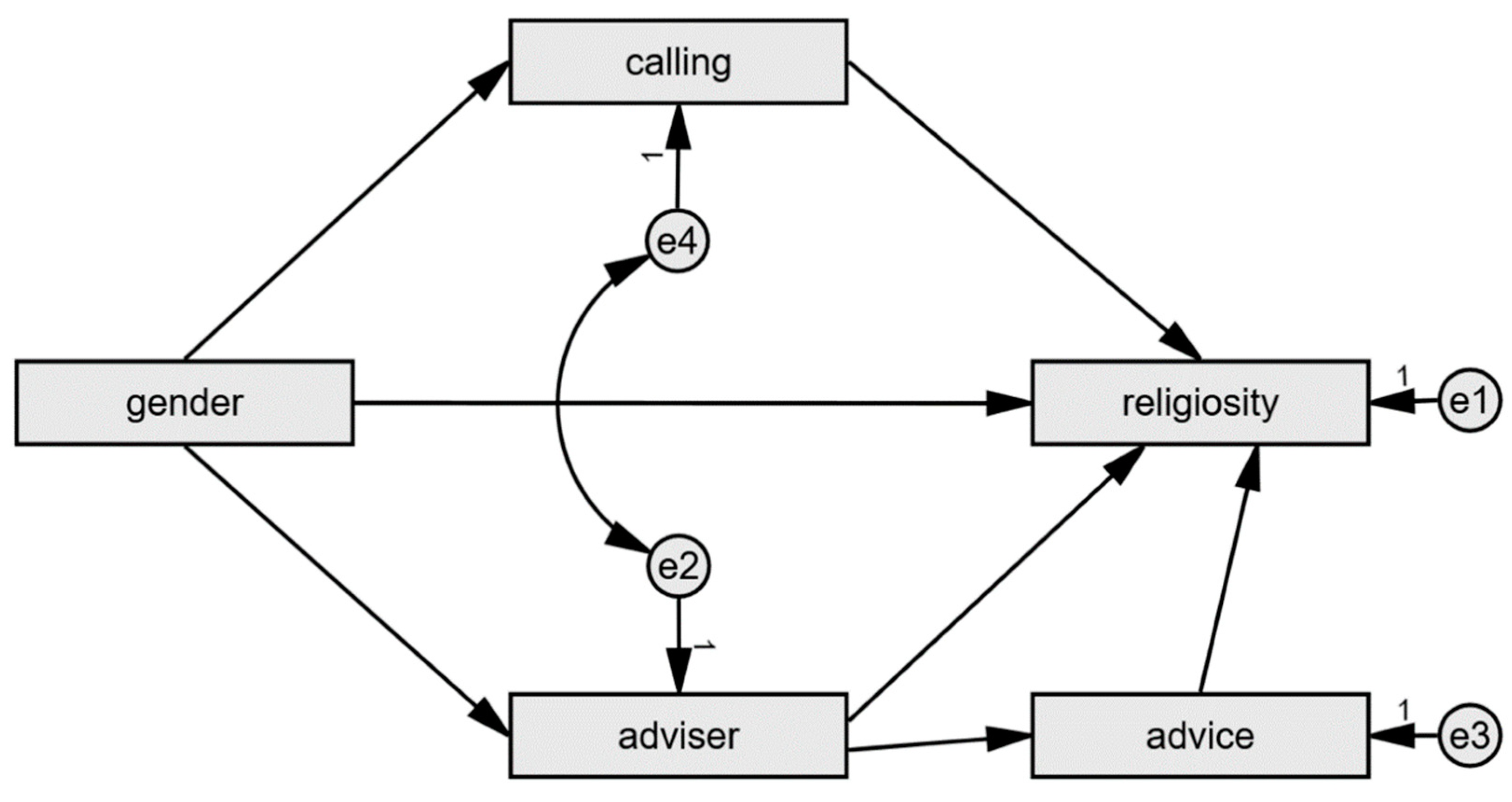

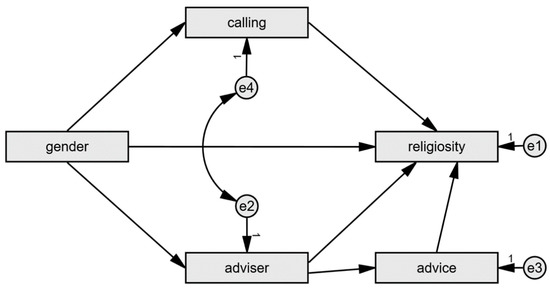

The path analyses are split in two. Identical models are run with the Orthodox and Pentecostal subsamples. The models comprise 5 manifest variables: gender, calling, presence of a religious adviser, advice, and the target variable of religiosity, which is the CRSi-7 score, because of its more general-purpose compared to the CRS-5 and a slightly better model fit in the CFA. Gender is the only exogenous variable, with both direct and indirect paths to religiosity. The indirect channels are mediated by calling on the one hand, and religious adviser with advice on the other one. The residuals of calling and the presence of a religious adviser are allowed to correlate in the model after an iterative model modification process. The final model is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Path analytical model of religious individualism for Orthodox and Pentecostal Christians in Romania. The rectangles stand for manifest variables, the circles depict residuals, the curved arrows show covariances, and the straight arrows present regressions.

In the case of the Orthodox subsample, the direct paths from gender to calling and from calling to religiosity are restricted to zero (the top of the model in Figure 2). For the Pentecostal model, the direct channels from gender to religious adviser and from religious adviser to religiosity, as well as the correlation between the residuals of calling and religious adviser are set to zero (bottom of the model in Figure 2). These changes were introduced to the models after an iterative process by which non-significant paths were restricted after verification of the results. On the one hand, such restrictions result in the gain of some degrees of freedom and, on the other hand, a stricter model test about the established hypotheses. The final models are evaluated according to the same quality assessment criteria as the CFA (see the section on Confirmatory Factor Analyses).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The examination of the CRSi-7 index shows that both subsamples have a high proportion of highly religious persons: Pentecostal 96.0% and Orthodox 70.7%, with 2.9% and 26.4% for religious, and 1.1% and 2.9% non-religious, respectively. Therefore, the conclusions from these samples can be viewed as statements, especially for highly religious believers. These observations are supported by the figures in Table 2. With a range of 1 to 5, all core dimensions indicate a tendency towards the maximum of the scale distribution, especially in the Pentecostal subsample (see the difference of the means). Standard deviations for short forms of the CRS are higher in the Orthodox subsample by all core dimensions and for total scores.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations with the difference of the core dimension of the CRS-5, CRSi-7, calling, and frequency of advice for Orthodox and Pentecostal subsamples.

The Calling scale has a range of a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 6. It shows a statistically significant difference between the two groups two-tailed. The mean difference with the corresponding 95%-confidence interval (CI) is and an effect size of Cohen’s with a 95%-CI .

The last metric scale examined is the use of the advice which ranges from a minimum of 1 to a maximum of 5. An independent t-test shows a statistically non-significant difference between the two groups: two-tailed. The mean difference with the corresponding 95%-confidence interval is . Details of the examined scales and their subscales can be found in Table 2.

3.2. Psychometric Properties of CRS-5

The Cronbach’s of the CRS-5 for the Orthodox subsample is good with , the corresponding McDonald’s is . The -coefficient for the Pentecostal group is slightly lower and acceptable with , while the corresponding McDonald’s is . The reason for the drop in the alpha coefficient within the Pentecostal group can be seen in the lower correlations of the core dimensions among each other.

As can be seen in Table 3 all except for the one between prayer and public practice are higher within the Orthodox subsample. Regarding the Orthodox respondents, the range of correlations goes from a minimum of (intellect with ideology and prayer) to a maximum of (ideology and prayer). In contrast, the Pentecostal subsample’s range has slightly wider boundaries with a minimum of (intellect and public practice) and a maximum of (prayer and public practice).

Table 3.

The correlations of the core dimensions of the CRS-5 in the Christian Orthodox and Pentecostal subsamples.

3.3. Psychometric Properties of CRSi-7

Besides the calculation of the internal consistency of the CRS-5, the reliability estimation of the CRSi-7 for the Orthodox subsample is good , with a corresponding McDonald’s of . The -coefficient for the Pentecostal group is again, the same as for the CRS-5, a little lower , which is an acceptable value. The corresponding McDonald’s has the same value as . Table 4 presents the correlations of the core dimensions among each other for the CRSi-7. The values range between medium and strong correlations suggesting that the core dimensions have at least weak but mostly strong communalities.

Table 4.

The correlations of the core dimensions of the CRSi-7 in the Christian Orthodox and Pentecostal subsamples.

3.4. Correlational Analyses

In preparing the path analyses, the bivariate Pearson correlations between the two short CRSs, calling and the use of advice, show that the CRS-5 and CRSi-7 are strongly correlated in both groups. Further, it demonstrates that calling is positively associated with the Centrality of Religiosity (CRS) in the Pentecostal group and has an opposite association in the Orthodox one. While calling has no association with the use of the advice in the case of the Pentecostals, it is weakly associated with the Orthodox subsample. The use of advice has a strong association with the Centrality of Religiosity (CRS) of Orthodox people and a moderately strong correlation for the Pentecostals (see Table 5 for more details).

Table 5.

The correlation analysis of the variables Calling and religious adviser with the CRS-5 and the CRSi-7 split for the two subsamples of Orthodox and Pentecostal Christians.

For the dichotomous variables of interest (i.e., gender and the presence of a religious adviser), the point-biserial correlation between them is significant for the Orthodox sample with and non-significant for Pentecostals on a conventional 5% -level. Gender (0—female, 1—male) is negatively correlated with the Centrality of Religiosity, as measured by the CRS in both groups. The correlation between gender and calling is non-significant for the Orthodox but statistically significant with an for the Pentecostals. Regarding the association between Gender and the use of advice, the correlation is negative in the Orthodox group ), while non-significant in the Pentecostal one.

Considering the associations of the presence of a religious adviser in the life of the Orthodox believers, there is a moderate, negative association with calling and strong, positive correlations with the Centrality of Religiosity and the use of advice. The pattern is somewhat different for the Pentecostal subsample, in which the association of the presence of a religious adviser and calling is not significant. While the correlations between the presence of a religious adviser and the use of advice for daily problems are moderate, the associations with the Centrality of Religiosity are small and both are statistically significant (see Table 6 for more details).

Table 6.

The point-biserial correlations of CRS-5, CRSi-7, Calling, advice with the dichotomous variables gender and religious adviser, split for the two subsamples of Orthodox and Pentecostal Christians.

3.5. Confirmatory Factor Analyses

In terms of global fit, the models were iteratively modified according to the proposed modification indices (MI) until the set-up goodness of fit criteria were met, resulting in models with correlated residuals. Although covariance of residuals is the only possible point of modification in the models, it took up to two residual correlations to get good-to-very good global model fits. The introduced residual correlations differ between the CRS-5 and the CRSi-7 models, as well as between Orthodox and Pentecostal samples, except for the correlated residuals of the indicators of intellect and religious experience– which is common to all models. The generated correlations are reported together with the estimated model parameters in the subsequent sections and discussed in the general discussion section of this paper.

3.5.1. CFA of the CRS-5

Regarding the correlations of the CRS-5 indicators (see Table 3), the associations are stronger—in other words, higher correlations—for Orthodox than for Pentecostals, except for the combination of private and public practice with an in favor of the Pentecostal subsample. The same can be said about the point estimate of the factor loadings of the Centrality of Religiosity factor on the indicators of the five core dimensions in the CFAs. Considering the global fit, both models achieve excellent results, except for the RMSEA.

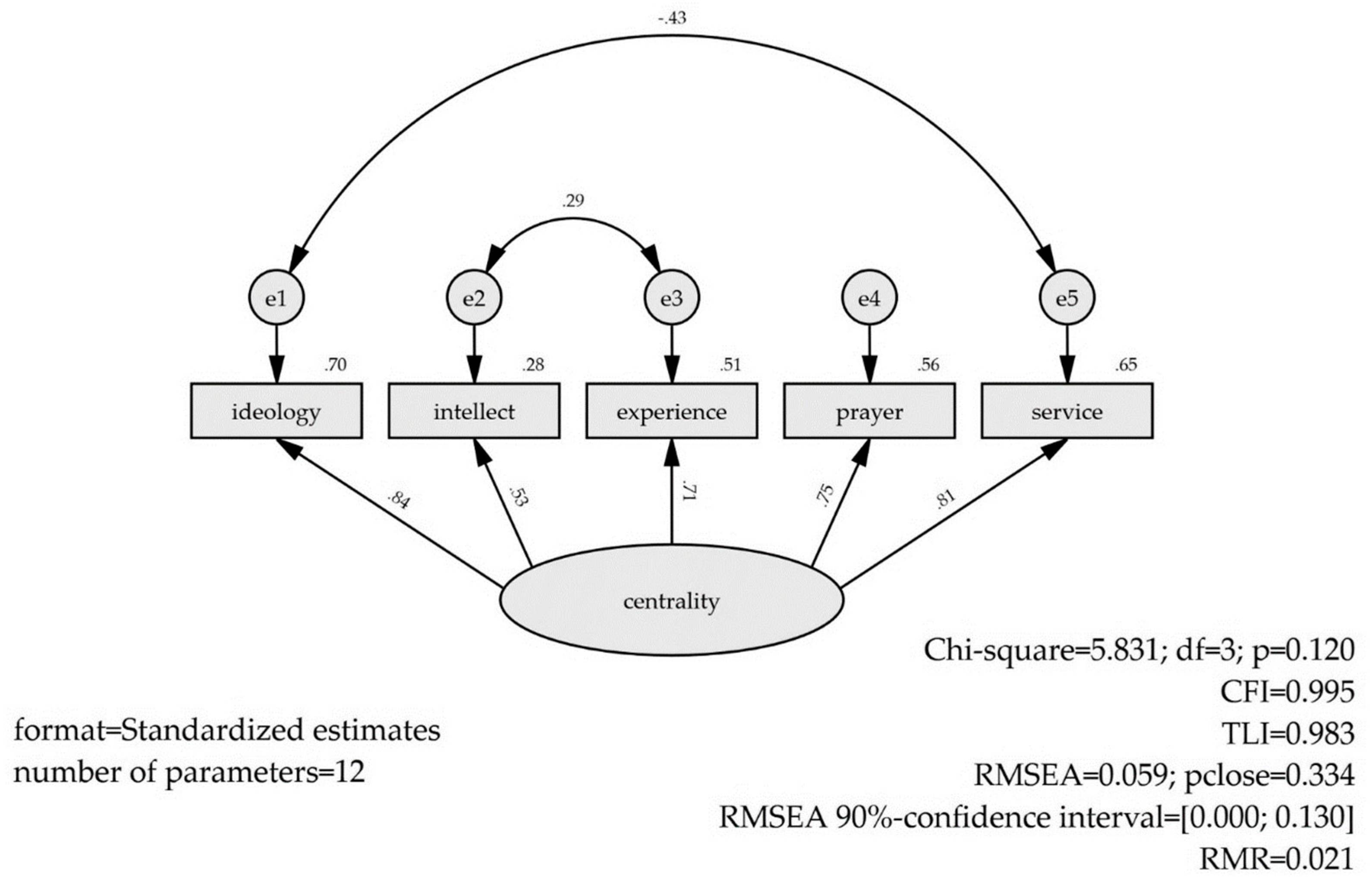

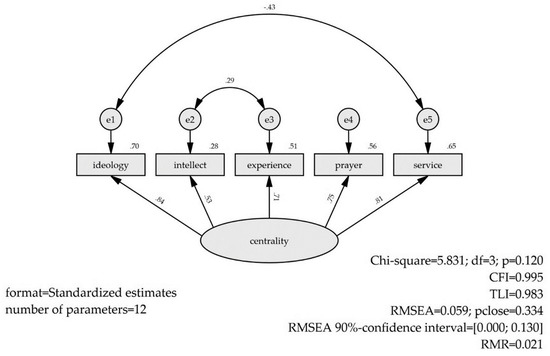

CFA of the CRS-5 in the Orthodox Subsample

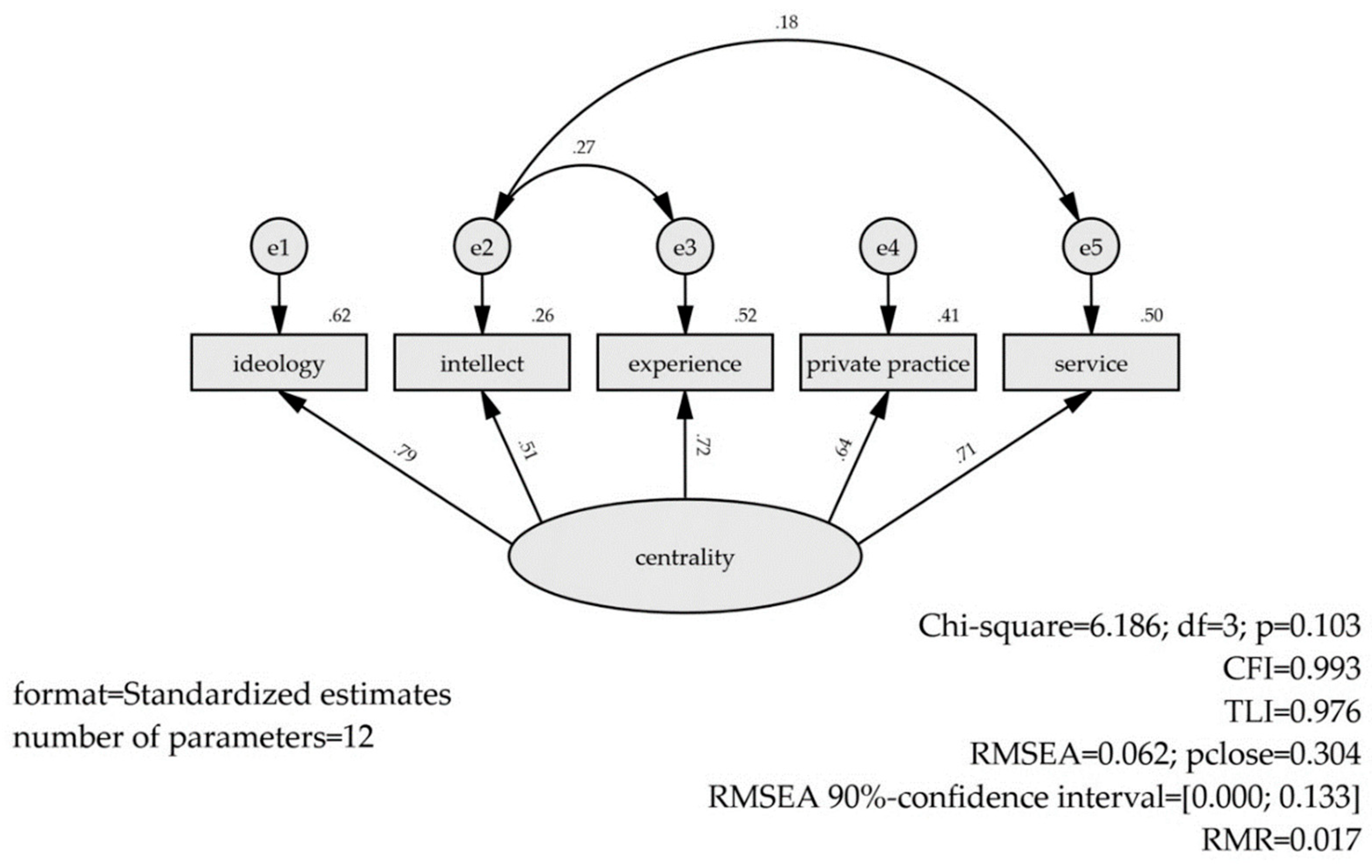

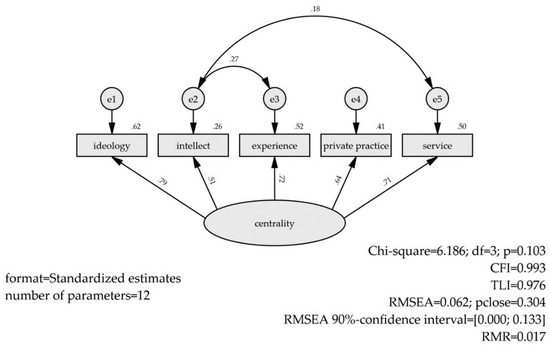

Seen globally, the model that received correlated residuals of ideology and public practice , as well as intellect and experience , performs well according to all established goodness of fit criteria, i.e., , , , , . From all model fit indices, only the upper bound of the 90% confidence interval of the RMSEA violates the conventional goodness of fit, which is still acceptable seeing the non-significant closeness of fit probability test value of the RMSEA. Figure 3 presents the graphical representation of the model and the results.

Figure 3.

The Centrality of Religiosity Scale, CRS-5, Romania 2019, Orthodox Christians subsample.

The local fit shows no local points of weaknesses. Each factor loading is statistically significantly different from zero on the level. The factor weights mark at least a salient to a substantial presence of the Centrality of Religiosity factor in the variance of the corresponding indicator. Most unexplained variance is left in the indicator of intellect. With 71% of explained variance, the indicator ideology is best predicted by the latent variable of the Centrality of Religiosity.

According to modification indices, the CFA model received two covaried residuals, the first one from intellect and experience with 90% CI , the second one of the residuals is from ideology and public practice is . See Table 7 for a detailed overview of the factor loadings and explained variance of the indicators with the corresponding bootstrap CIs and Figure 3 for the structural representation of the results.

Table 7.

The overview of the parameter estimates in the confirmatory factor analysis of the CRS-5 in the Orthodox subsample.

CFA of the CRS-5 in the Pentecostal Subsample

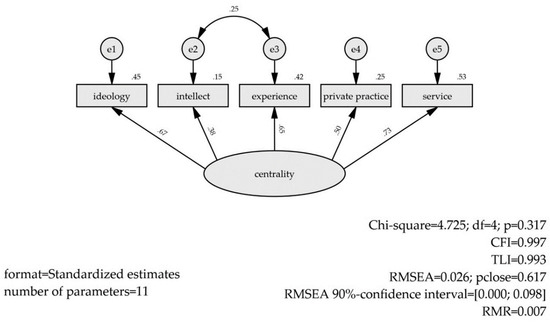

The results of the global fit model test propose a very good model fit of the CFA of the CRS-5 in the Pentecostal group with a CFI of , a TLI of , a Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation with its 90% bootstrapped corrected confidence interval of , an SRMR of , and a chi-square test of . All but the upper boundary of the RMSEA confidence interval comply with the setup goodness of fit criteria. Still, the closeness of fit probability value is non-significant for the RMSEA which means that the RMSEA in the population is not statistically higher than 0.05. Figure 4 shows the graphical representation of the model results.

Figure 4.

The Centrality of Religiosity Scale, CRS-5, Romania 2019, Pentecostal Christians subsample.

Local fit indices show no points of weakness. All factor loadings are statistically different from zero corroborating the indicators as a part of a whole. However, the factor loading of intellect is relatively weak with an explained variance portion of only 11%. The strongest factor loading among the five indicators is with public practice. The factor loadings of ideology and experience explain 31% each, while prayer explains 55% of the variance in their corresponding indicators, respectively. See Table 8 for more details on the factor loadings and explained variance with their bootstrapped bias-corrected confidence intervals.

Table 8.

The overview of the parameter estimates in the confirmatory factor analysis of the CRS-5 in the Pentecostal subsample.

Modification indices indicated two points of improvement in the model. These are the covariances of the residuals of intellect and experience with 90% CI and the ones of ideology and experience with 90% CI .

3.5.2. CFA of CRSi-7

For the CRSi-7, the correlations are higher in the Orthodox subsample for all combinations of core dimensions compared to Pentecostals (see Table 4). If compared to the correlations of the CRS-5 core dimensions, differences can be expected for every bivariate combination with the contribution of either experience or private practice, because these two receive different values in the CRSi-7 and the CRS-5 version. Indeed, the correlations drop remarkably in each of the combinations with the two mentioned indicators. Furthermore, the change in the correlation of private and public practice, which decreases by an in the Pentecostal group and in the Orthodox one, is noteworthy. Nonetheless, the CFA models demonstrate decent results.

CFA of the CRSi-7 in the Orthodox Subsample

Regarding the absolute indices, the CFA of the CRSi-7 shows good parameter values, with an SRMR of , and chi-square of . The relative fit indices of a CFI of and a TLI of also demonstrate that the model reproduces the data well. Only the upper boundary of the RMSEA crosses the set-up quality criteria . The non-significant closeness of fit probability value still shows a population RMSEA lower than 0.05. Figure 5 demonstrates the results of the CFA in a graphical form.

Figure 5.

The Centrality of Religiosity Scale, CRSi-7, Romania 2019, Orthodox Christians subsample.

Regarding the local fit, no points of model weakness can be identified. Factor loadings have at least a salient weight. The corresponding values have a range of a minimum of 26% for the core dimension of intellect to a maximum of 62% for the core dimension of ideology. The explained variances in the indicators of religious experience, private and public practice are 52%, 41%, and 50%, respectively. Table 9 presents the results in a structured form and with details.

Table 9.

An overview of the parameter estimates in the confirmatory factor analysis of the CRSi-7 in the Orthodox subsample.

Modifications have been made concerning the covariances of the residuals of intellect and experience reported with 90% CI and the covariance of the residuals of intellect and public practice .

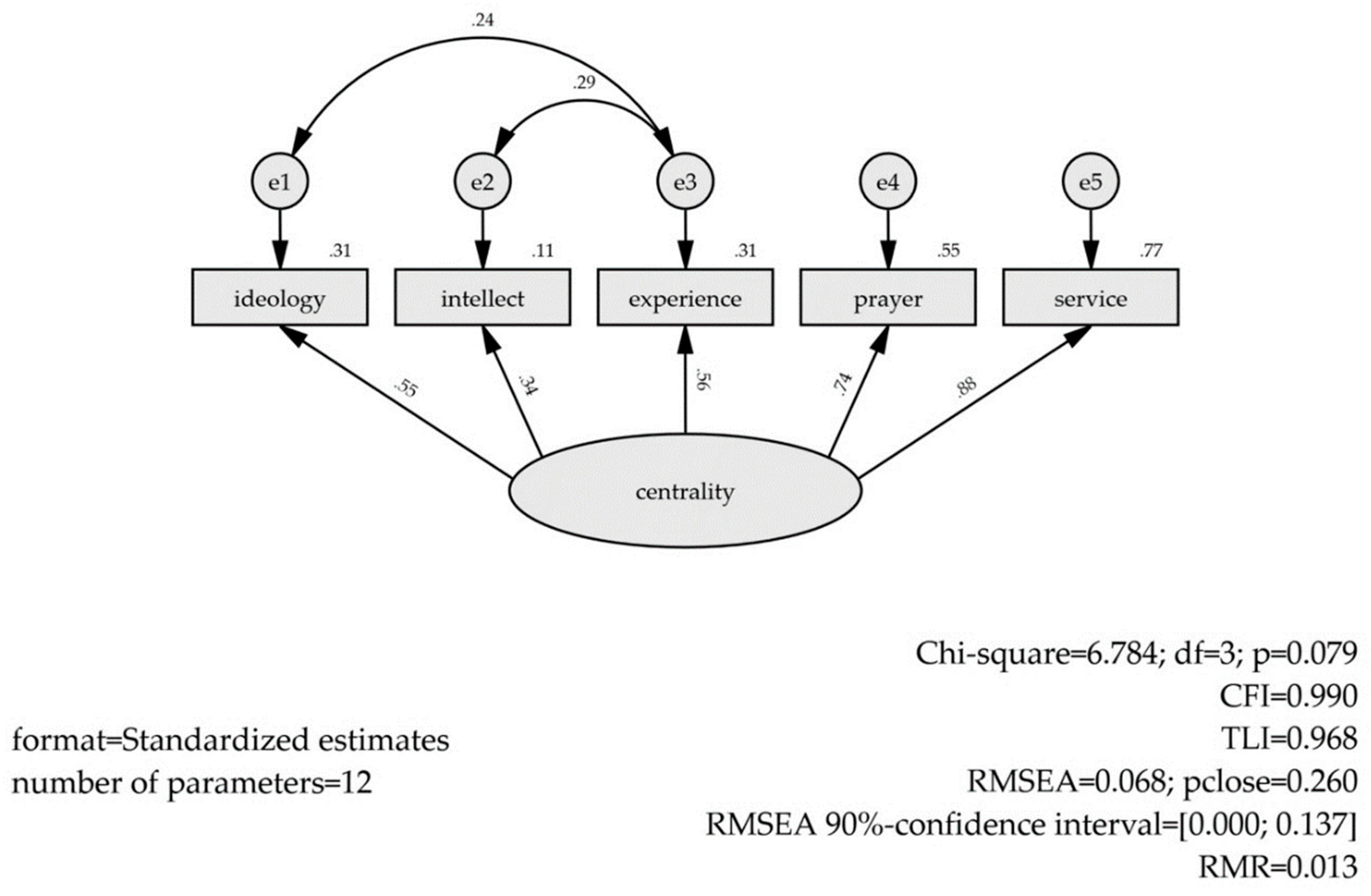

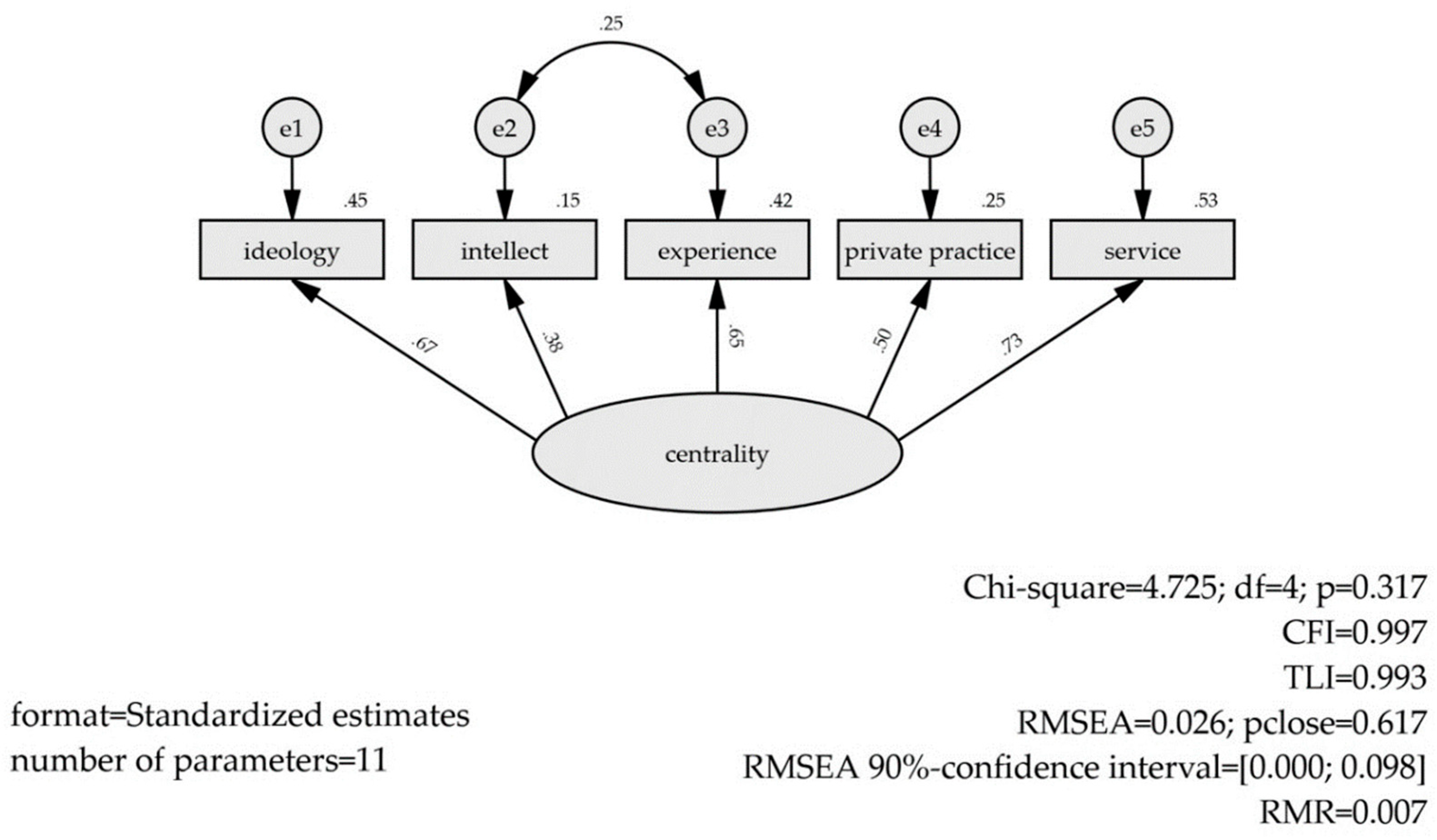

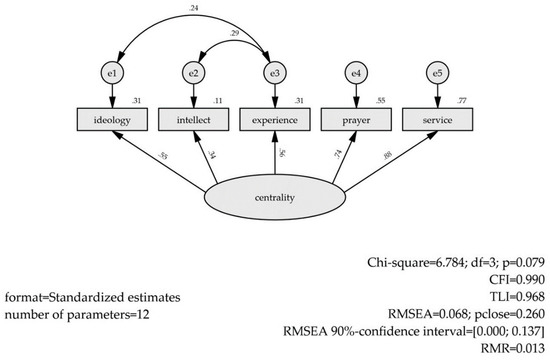

CFA of the CRSi-7 in the Pentecostal Subsample

The last of the four CFA models is the confirmatory factorial test of the CRSi-7 in the Pentecostal subsample. With a and , it shows a very good model fit in terms of relative fit indices. In terms of absolute model indices, the same conclusion can be made with an SRMR of and a chi-square test value of . Only the upper bound of the 90% confidence interval of the RMSEA violates the set-up goodness of fit criteria . The non-significant closeness of fit test demonstrates that the RMSEA in the population is less than 0.05. A graphical demonstration of the CFA results is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The Centrality of Religiosity Scale, CRSi-7, Romania 2019, Pentecostal Christians subsample.

The smallest factor loading is shown for the indicator of intellect, while the biggest factor loading relates to public practice. Thus, the explained portions of variances in the indicators range between 15% of intellect and 53% of public practice. Values lying in between are the explained variances of the indicators of private practice, religious experience, and ideology with 25%, 42%, and 45%, respectively. Table 10 shows more details on the factor loadings and the explained variance of the indicators.

Table 10.

The overview of the parameter estimates in the confirmatory factor analysis of the CRSi-7 in the Pentecostal subsample.

One modification is proposed for the CFA by the modification indices with the covariance of the residuals of intellect and experience with its 90% CI .

3.6. Path Analyses

Generally, models were first run without any restrictions on the parameters, in a second step non-significant paths (parameter estimates) were iteratively restricted to be zero, following the hypotheses of this study. Presented models are the results of that iterative process. Both path analytical models demonstrate a very good model fit in terms of the set-up quality criteria. The model for the Orthodox subsample received one less restriction—that of the covariance of the residuals of calling and the presence of a religious adviser—than the model for the Pentecostal group. Therefore, their fit indices are not directly comparable. Still, with satisfactory global fits, the paths in the models show some mechanisms which distinguish the religious cultures of these two presented Christian denominations. The gender variable, as a central exogenous demographic determinant of religiosity, serves as a starting point for the interpretation of the path analyses, which is done in the subsequent paragraphs.

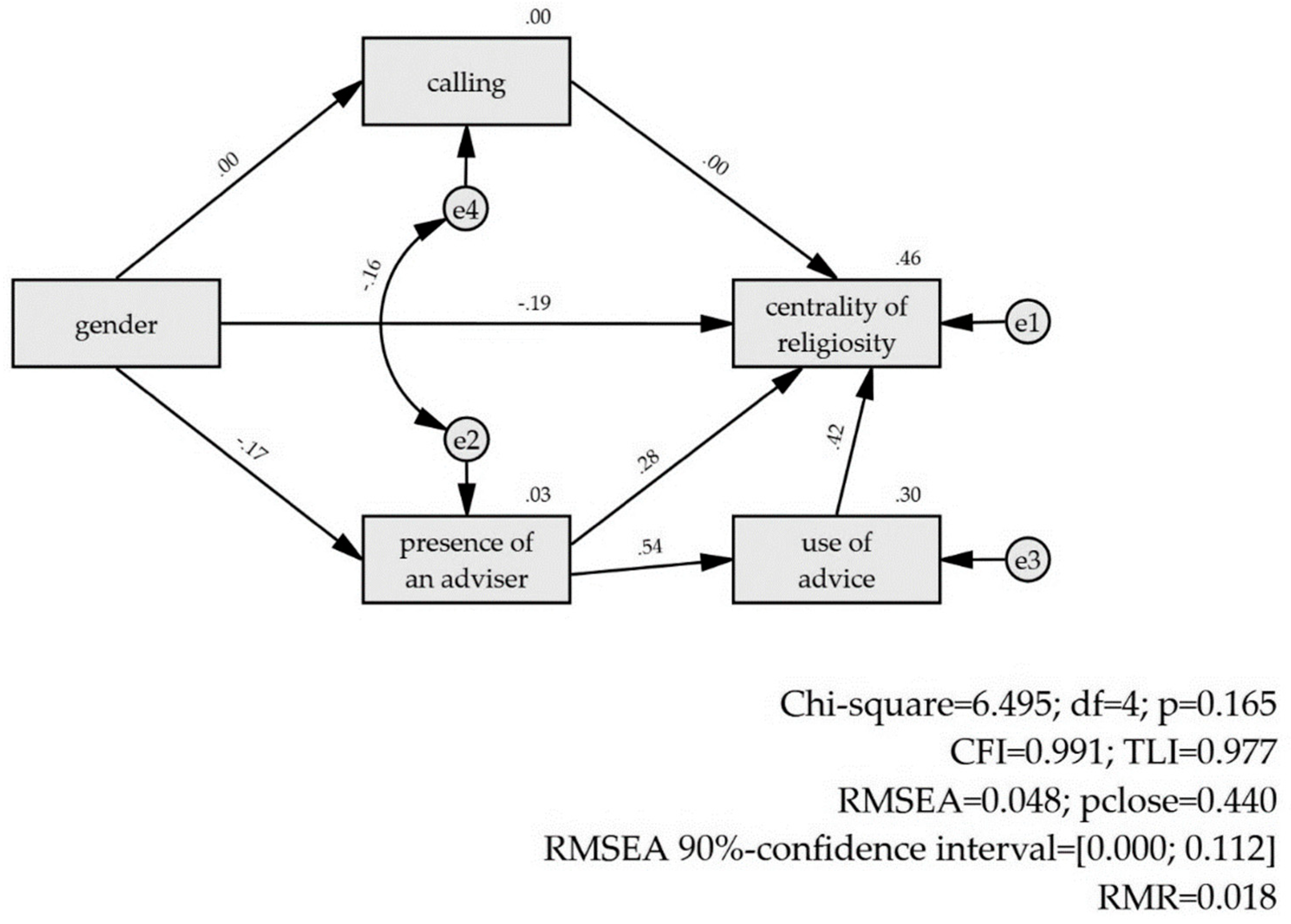

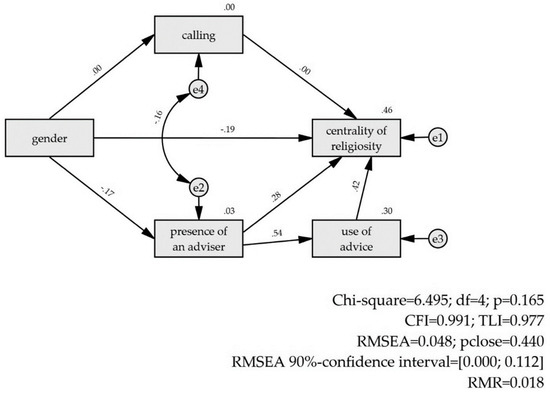

3.6.1. Path Analysis in the Orthodox Subsample

With a CFI of , TLI of , RMSEA with its 90% CI of , SRMR of , and chi-square test value of , the path analysis of the Orthodox subsample shows a very good global model fit. Only the upper bound of the 90% CI of the RMSEA crosses the goodness of fit index of 0.08. With a non-significant closeness of fit p-value, it can be assumed that the RMSEA is not higher than 0.05 in the population. The review of the local parameter estimates shows no non-significant paths, except for those which were intentionally set to be zero according to the hypotheses.

As shown in Figure 7, the whole path from gender to religiosity via calling is non-significant in the Orthodox subsample. Gender has a direct effect regarding both the presence of a religious adviser and the Centrality of Religiosity while indicating that men are less connected with advisers , and that they are less religious . Furthermore, gender has an indirect effect on religiosity through the mediating variables of the presence of a religious adviser, and the advice on everyday issues; the total effect of gender on religiosity is .

Figure 7.

Path analysis of the influence of religious culture on Centrality of Religiosity of Orthodox Christians.

The presence of a religious adviser has a direct effect on the use of the advice with an , while the use of advice has a direct effect on religiosity with . Combined, the variable presence of a religious adviser has both direct and indirect effects on religiosity, the indirect path being a bit weaker than the direct one: , while , and a total effect of . The residuals of calling and the presence of a religious adviser correlate weakly .

The Centrality of Religiosity receives a total of four paths with the explained portion of the variance being .

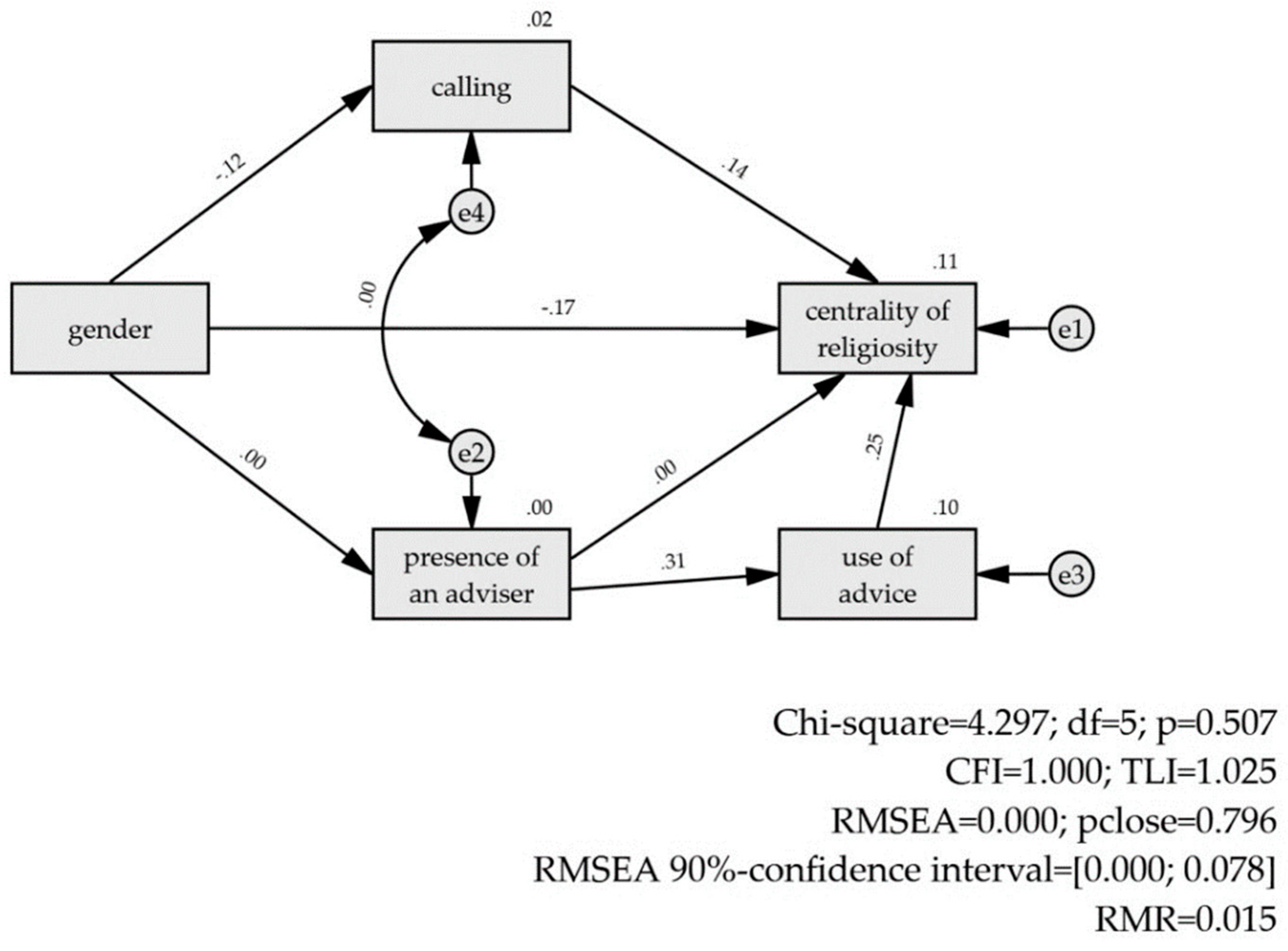

3.6.2. Path Analysis in the Pentecostal Subsample

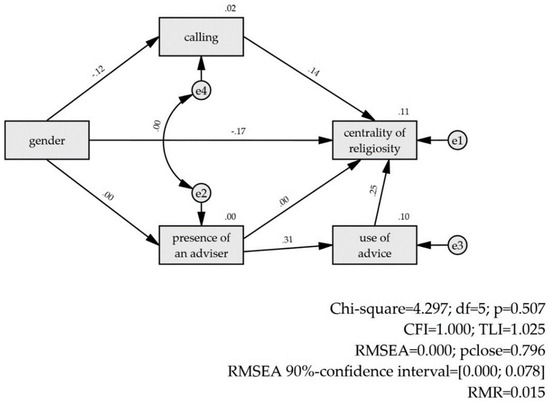

A path analytical model of the Pentecostal group shows a very good model fit with a CFI of , TLI of , RMSEA with its 90% CI of , SRMR of , . The global fit indices allow for a meaningful interpretation of the local paths in the model of which none have been identified as non-significant except for those which were set to be equal to zero, corresponding to the hypotheses of the present study.

In the case of the Pentecostal subsample, the variable gender has a direct effect on the Centrality of Religiosity , but not on the presence of a religious adviser. Men are less religious, a result that is comparable to that of the Orthodox subsample. Furthermore, no indirect effect was found on religiosity through the mediating variable the presence of a religious adviser. Moreover, gender has a direct, but small, effect on calling , and it exerts a low indirect effect on religiosity through calling. The direct effect of calling on the Centrality of Religiosity is small but present . Added together the total effect of gender on religiosity is .

The presence of a religious adviser has a direct effect on the use of the advice with , while the latter has a direct effect on the Centrality of Religiosity with . Taken together, the indirect effect of the presence of a religious adviser is .

The Centrality of Religiosity receives a total of four paths with an overall proportion of the explained variance of . See Figure 8 for a graphical representation of the results.

Figure 8.

Path analysis of the influence of religious culture on Centrality of Religiosity of Pentecostal Christians.

3.6.3. Summary of the Path Analyses

In conclusion, both subsamples show that gender is an important demographic determinant for religiosity in both direct and indirect ways. When taking into account the direct effect of gender, we found that men are less religious than women both in the case of the Orthodox and Pentecostal subsamples. Moreover, we found an indirect influence of gender through the mediation of either the variables calling or the presence of a religious adviser on the religiosity of Pentecostals and Orthodox believers, respectively. In both subsamples, the analyses show that both the presence of a religious adviser and the use of advice act as an indirect path for personal religiosity.

4. Discussion

Following the structure of the method section, the results of the confirmatory factor analyses are discussed before moving on to debate the results of the path analyses. In the last step, a general summary is made and the strengths and limitations of the present study are noted. However, we would like to draw the reader’s attention first to the fact that humility was not distinguishing between the two samples of Orthodox and Pentecostal Christians in Romania.

The hypothesis of difference in humility had to be rejected in the preliminary data check. A possible reason for the equality in humility in both groups is the high share of highly religious respondents. This might lead to a high expression of religious characteristics—here humility—and thus to no substantial difference between the groups. We could not check whether the groups would differ if we took only the non-religious and religious categories. For this, we did not have enough respondents. The religious and non-religious categories were too small in the subsamples of Orthodox and Pentecostal in the present investigation.

A further aspect of the non-significant results concerning humility is the fact that the Calling Humility Scale was developed in the context of market exchange to capture the different basic economical notions of Orthodox and Protestant denominations. The formulation of the items is indirect (“this person is…”) and should facilitate the identification with the statement but it might have a differential effect with the Calling and the Humility scales when applied with highly religious respondents. We can only speculate that humility applies rather in a different context than market exchange or that because of the high proportion of highly religious respondents, humility is expressed in both denominations to an extent that the particularity which was expected to appear in the Orthodox sample is removed. Taking Zabaev’s (2015) findings we cannot confirm that humility is a distinct Orthodox characteristic or even a virtue in Romania compared to the findings in Russia.

Calling and humility both do not rule out the subordination of a believer to a higher power or an “earthly” figure. While calling has only one reference point which can be, for example, an institutional authority or God, humility is a general interpersonal attitude that can refer to anyone. Therefore, it may explain why both Orthodox and Pentecostal Christians have high humility scores, but only the Pentecostals have a distinct calling aspect expressed because the path of authority in their faith life is not directly linked with their religiosity via an adviser. Speaking about religiosity and the effects on it lead to its assessment with the CRS. Before further discussing the results of the path-analyses, the role of calling, advice, and adviser, some words are said on the validity of the CRS-5 and CRSi-7 in the Romanian sample. Readers interested in the discussion of the results of the path-analyses may go over to the discussion of the results of path-analyses.

4.1. Discussion of the Results of Confirmatory Factor Analyses

The main result of the confirmatory factor analysis is that a one-factor model with five reflective indicators worked with, on the one hand, both the CRS-5 and CRSi-7 data and, on the other hand, with the Orthodox and Pentecostal subsamples. Further, in all models the indicator of the intellectual dimension received the weakest factor loading, leaving a great portion of the variance of the indicator to be explained by the residual. Moreover, in all models, the residual for the intellectual dimension correlated with the residuals of the indicator of the religious experience dimension. The algebraic sign and size of the correlations among these residuals are relatively stable considering the bootstrapped confidence intervals. In light of this stable correlation of the residuals of intellect and religious experience, other residuals’ correlations (i.e., ideology with experience, ideology with public practice, intellect, and public practice) appear to be methodological artifacts. Indeed, checking, for example, the negative correlation of the residual of ideology and public practice in the CFA of the CRS-5 in the Orthodox group reveals the following: when controlling for the effect of centrality, some small numbers remain on the secondary diagonal, i.e., the higher the participation in Sunday Service, the lower the belief in God. Therefore, the authors argue that on a group level, there is some systematic association between the core dimensions of intellect and religious experience for highly religious people which takes place outside of the Centrality of Religiosity. With the two subsamples, where the proportion of highly religious believers of either Orthodox or Pentecostal Christians is over 80% (see Table 2), this might be an observation that should be considered in future investigations with the Centrality of Religiosity Scale.

A methodological point of discussion is the correlation between the total score of the CRS-5 and CRSi-7 with their respective indicators. The numbers show that the total score’s correlation with either of the indicators is always higher than the correlations among themselves. That means that each indicator adds a substantial value to the full scale. Thus, it seems logical that none of the indicators’ factor loadings are statistically non-significant or drop lower than , which would be less than the salient presence of a factor in an indicator (Brown 2015). Another methodological issue with highly religious people is that the restriction of variance becomes a reason for reduced correlation sizes. The means of the core dimensions are higher, and the variance is more restricted for the Pentecostals. In such conditions, the correlations do not behave the same as in a sample with a majority of religious individuals. That might be one possible reason why the correlations are higher in the Orthodox subsample, where the proportion of the “religious” category is higher. Still, the scale shows no substantial points of CFA model weakness.

Additionally, in terms of sample size, the almost-balanced groups of Orthodox persons, a religious majority in Romania, and Pentecostals, a religious minority, allow for a comparison of highly religious believers within the country. This mainly plays its role within the discussion of path analyses in this study.

4.2. Discussion of the Results of the Path-Analyses

Firstly, path analyses demonstrate that gender is an important demographic determinant of religiosity regardless of the denomination (Orthodox or Pentecostal). Secondly, the presence of a religious adviser is not an exclusively Orthodox phenomenon. However, while the presence of a religious adviser is common in both groups of believers, as expected, the Orthodox believers use advice more frequently than the Pentecostals. In the Orthodox sample, the presence of a religious adviser is directly linked with the Centrality of Religiosity, which means that such a person has a direct effect on religiosity, whereas for Pentecostals the effect is only mediated via the frequency of advice-taking. The presence of a religious adviser does not depend on gender in the Pentecostal subsample unlike in the Orthodox subsample. These findings are a strong indicator of the Pentecostals’ preference for religious individualism. The last variable in the analyses is calling. Calling itself is a within-person variable that is not linked to an external factor, e.g., the religious advisor in our analyses. Therefore, the finding of a small but significant path in the Pentecostal group leading from gender to calling and religiosity demonstrates a further element related to religious individualism in the case of Pentecostal believers. In contrast, it is a path that is non-significant within the Orthodox group, meaning that despite being familiar with the concept of calling, the religiosity of Orthodox is not affected by it. Overall, we can partly confirm the theses of Weber, that there is a distinct calling aspect which differentiates the Protestant tradition from others, while it is not strong it is present and has an effect on the personal religiosity. While calling is supported by the results as a unique characteristic of Protestants of which Pentecostals are an example, humility cannot be said to be a unique characteristic of Orthodox Christianity. If there is an opportunity to test the hypothesis about the difference in humility between Protestant and Orthodox there should be a representative sample where the share of “religious” category forms the majority.

For the Orthodox subsample, the overall effect on religiosity is much more determined by the identified mechanisms in comparison with the Pentecostal one (46% of the explained variance in religiosity compared to 11% in the latter case), expressing more of a guided religiosity (religious collectivism) rather than an individualistic one (religious individualism). The results show that the role of a religious adviser—which we think of as a priest in our example—is more important for the personal religiosity of an Orthodox Christian in a direct and mediated way. In comparison to the Pentecostals, the results show that the presence of an adviser for the Orthodox Christian is less optional and that the frequency of advice-taking is higher. We are not eager to generalize these findings to everyday life, but if we imagine that this pattern would apply in economical behavior, the thesis of Weber would have corroboration in our data insofar that Protestants have more of “Berufung” and transfer it to the “Beruf”. Thus, they take more action by themselves in solely reference to God, while for the Orthodox person it might be more of a guided path.

4.3. Summary

One problem of the empirical results concerning our hypotheses is that there was no significant mean difference between the Orthodox and Pentecostal groups concerning calling and humility. Therefore, we need to control for the level of religiosity via the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). The higher the CRS, the more the specific religious content of a member belonging to a certain religious denomination becomes relevant. This allows for comparisons without the confounding factor of religiosity. After performing a correlation analysis, we found a negative correlation between the CRS and calling in the case of the Orthodox group and a positive one for the Pentecostal sample. This is presented in Table 5. Moreover, the CRS is positively correlated with the CRS for both the Orthodox and Pentecostal groups. The score of humility still shows indifferent results even when controlling for the centrality of religiosity.

Returning to the antagonistic correlations between the CRS and calling for Orthodox and Pentecostal persons, we can support this argument by comparing these religious denominations, taking into account other dependent variables, namely:

- Having a confessor or personal priest or spiritual adviser (because the practice of confessing to a priest is fundamental for the forgiveness of sins and the attainment of salvation in Christian Orthodoxy, as estimated, we found a much higher correlation in the case of the Orthodox subsample compared to Protestant individualism); thus, guided faith life is more expressed in the Orthodox community.

- The practice of asking a priest or pastor for advice on everyday issues (the same as in the case of the previous idea, we expected and found a higher correlation in the Orthodox sample and a much lower one for the Protestant group); thus, while taking a piece of advice is not exclusive for Orthodox persons, it has a higher frequency for this group, which supports the idea of guided faith life.

Therefore, we consider that the item related to the practice of asking a priest or pastor for advice on everyday issues is a good predictor of religious individualism besides asking for calling and the presence of a religious adviser.

Overall, we found empirical support to argue that the CRS correlates with specific features that are typical of certain Christian denominations. Therefore, the calling framework is a rational deduction from this general thesis of Weber. In the Orthodox subsample, the results are in line with the previous idea that emphasized that its specific framework is based on an intimate and direct relationship with a priest (religious adviser) to search and fight for salvation rather than other traits related to calling, and therefore, confirming the findings of Zabaev (2015) related to the difference between Protestant and Orthodox Christians. Hence, in the case of the Pentecostal group, the vocational and personal effects are essential for these believers, being much more conducted by religious individualism than their Orthodox counterparts. These results are complementary to the findings of Weber (1963, 2005).

5. Strengths and Limitations

The presented study has some strong points and some potential points of critique. First of all, there is a unique almost-balanced sample of Orthodox and Pentecostal Christians in this study. Having in mind that in Romania, the Orthodox are the majority and Pentecostals are a minority, having these samples to compare introduces a rare study to the field of the comparative study of religiosity. A further aspect of the samples is the high proportion of highly religious participants. Such samples offer an exceptional opportunity to explore the psychosocial patterns of the highly religious believers of each of the denominations, which is done in the present investigation. The confirmatory analyses can be seen as the basis for the study of religiosity in Romania with the CRS and the multidimensional model of religiosity included. The path analyses deliver arguments for the distinguished sociological mechanism within parishes of Pentecostal and Orthodox believers.

While strong on the methodological side, there are some restrictions with the present samples. These samples are neither representative of the majority of the believers in the country nor are they representative of the composition of the religious denominations themselves. Looking at the determinants of religiosity it is clear that a lot of factors are not included in the analyses, e.g., age, level of education, occupational and marital status. Therefore, we encourage further investigations to pay special attention to the small proportion of explained variance of religiosity for the Pentecostal group.

A further point, which is more of a theoretical decision, is the causal paths drawn in the path analyses. It might be equally true to draw the regression lines from the Centrality of Religiosity to the variables which represent the calling, presence of an adviser, and use of advice. Imaginable is a reciprocal loop where the aspects of calling and religious adviser/advice are positively associated with an increasing Centrality of Religiosity and vice versa. This question has not been examined, although it is desirable for further immersion into the matter related to religious individualism.

6. Conclusions

Regarding the performance of the short versions of the CRS, CRS-5, and CRSi-7, it can be said that the scales work well and can be used for studies related to religiosity with the adopted Romanian translation (see Table A1 in Appendix A for the wording of the items and the answer options)2.

The path analyses of the religious culture of the Orthodox and Pentecostal Christians show that religiosity should be considered as a variable that not only captures the psychological dimension of faith but should also be included in social mechanisms. Distinctive differences between the two Christian denominations are calling for Pentecostals and the direct influence of a religious adviser on the religiosity of Orthodox believers.

Having done the study with samples of predominantly highly religious respondents leaves an ambiguous impression. On the one hand, asking highly religious believers about religious phenomena elicits the effects of faith on many aspects of their faith life. We assume that some of the phenomena would not be captured if the samples would be rather dominated by religious or non-religious respondents. Maybe this aspect can be balanced if the sample size gets bigger implying higher statistical power. On the other hand, having predominantly highly religious respondents restricts the variance in the variables of interest. For example, the authors wanted to report the reliability coefficients with their corresponding statistical confidence intervals. However, this was not possible because in the calculation with the Pentecostal subsample an error occurred reporting singularity of the data.

Two perspectives for the study of religiosity and religious individualism which arise from the current investigations are the integration of the individualization theses and the application of the intermediate or long form of the CRS. Generally speaking, the comparison of different religious traditions under the perspective of the individualization theses will put religious individualism in a theoretical frame where the question would be whether the ongoing individualization will have the same or different effects on distinct religious traditions or not. A methodological aspect of the study of religiosity is the degree of fineness which is achieved with different psychometrical instruments. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale has, besides its short versions—which were applied in these analyses—intermediate versions (CRS-10 and CRSi-14) and long versions (CRS-15 and CRSi-20). The intermediate and long versions have the same underlying multidimensional model of religiosity but capture additional aspects of each of the five dimensions. Therefore, if the interest is to go into the detail of the religiosity construct, these versions offer an instrument to do so.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and A.-P.P.; Data curation, M.A. and A.-P.P.; Formal analysis, M.A.; Funding acquisition, M.A.; Investigation, A.-P.P.; Methodology, M.A.; Project administration, A.-P.P.; Resources, M.A. and A.-P.P.; Software, M.A. and A.-P.P.; Supervision, M.A. and A.-P.P.; Validation, M.A. and A.-P.P.; Visualization, M.A.; Writing—original draft, M.A. and A.-P.P.; Writing—review & editing, M.A. and A.-P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundations (SNSF) in a form of a grant. The grant was provided to the University of Bern (project № IZLRZ1_163880). The APC was funded by Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number IZLRZ1_163880).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the international nature of the project from which the data was taken. Therefore, the data sharing is restricted by different national standards.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefan Huber from the University of Bern, Switzerland for his advice and consulting during the writing of the manuscript. We acknowledge the administrative support and assistance of Sabrina Marie Sovilla, in Psychology at the University of Bern, Switzerland.

Conflicts of Interest