How Religion, Social Class, and Race Intersect in the Shaping of Young Women’s Understandings of Sex, Reproduction, and Contraception

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Religion and Knowledge about Reproduction and Contraception

2.1. Religious Ideology

2.2. Personal Religiosity

2.3. Religious Service Attendance

3. Factoring in Complex Religion

3.1. Considerations of Social Class

3.2. Considering Race

3.3. Considering Race and Social Class Simultaneously

4. This Study’s Approach

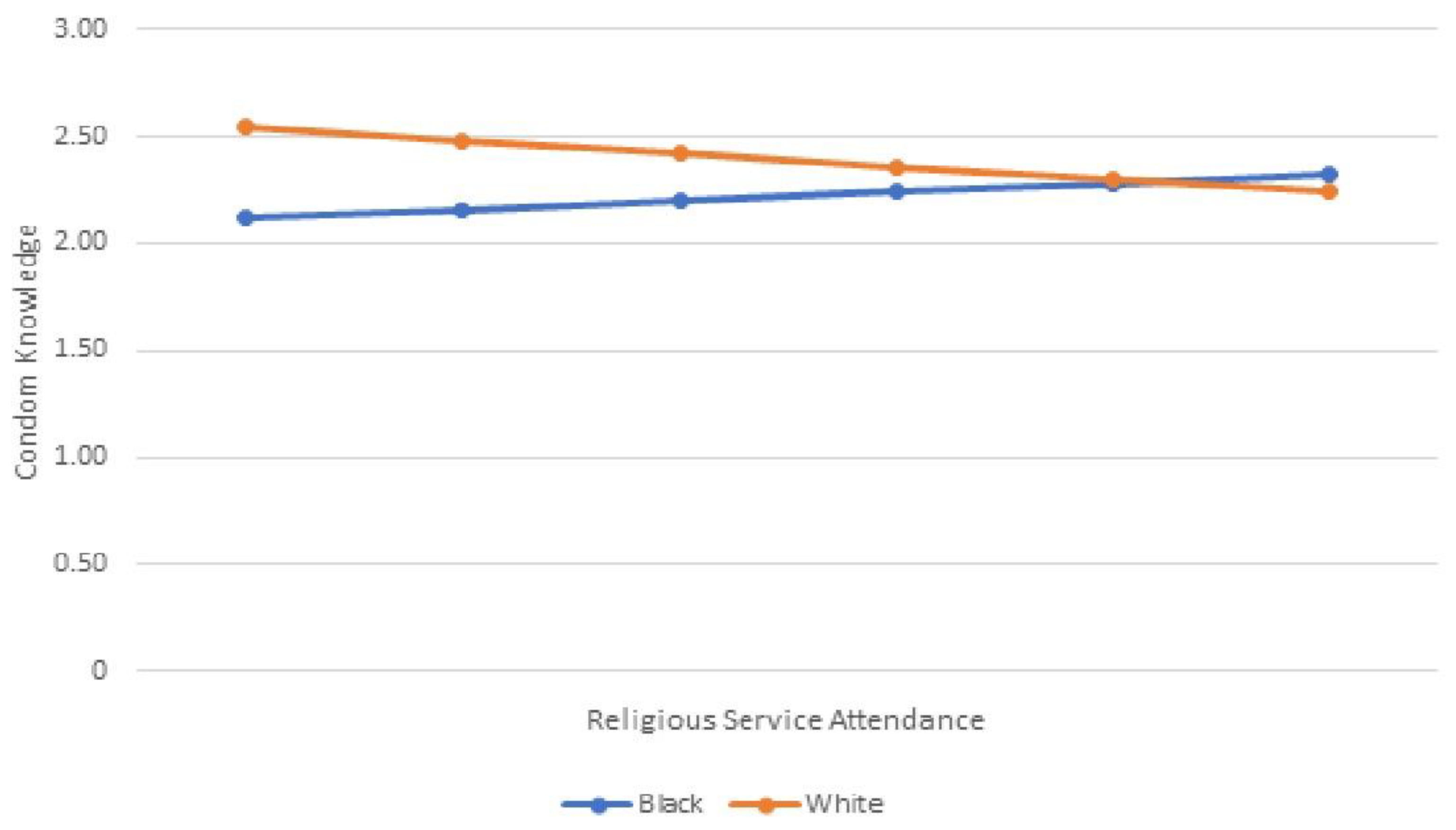

5. Quantitative Data and Findings

5.1. Relationship Dynamics and Social Life (RDSL) Survey Data

5.2. Findings

6. Qualitative Data Analysis and Findings

6.1. National Study of Youth and Religion (NSYR) Interview Data

6.2. Findings

6.2.1. White Women with Higher Parental Education: Religion Alters Personal Strategies

Ultimately, her religious project is grounded in having the right beliefs and doing her best to embody those beliefs in her daily practices, although she believes there is room for improvement.I think, like, if you have like faith in God, in Jesus and like he rose from the dead, then I definitely think that you’re going to have morals different than like a person that’s secular, and I don’t really… [pause] I know there’s so many beliefs out there, I don’t really, I don’t know, just like to other people what’s wrong is definitely not going to be wrong. But to me, like it would be wrong. I don’t know how to describe it.

6.2.2. White Women with Lower Parental Education: Religion Is Neutral When Misinformation Is High and Opportunity Costs Are Low

I’m actually on birth control right now, but, you know, it’s just to try and get started on it. I don’t really, I mean I see the need in it, but then I don’t see the need in it I guess. I feel like if you’re gonna get pregnant, you’re gonna get pregnant.

6.2.3. Black Women with Low Parental Education: Religion as a Resource for Social Mobility

It’s 100% [a] concern because disease is spreading fast and you can ask a person if they have something and they can lie to you and say they don’t and they could have it all the while and you make the choice to do something like that and you expose yourself to catching it. So it’s a concern to everyone, it’s 100% concern.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamczyk, Amy. 2012. Investigating the Role of Religion-Supported Secular Programs for Explaining Initiation into First Sex. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 324–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, Jennifer, Yasamin Kusunoki, and Heather H. Gatny. 2011. Design and implementation of an online weekly journal to study unintended pregnancies. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research 9: 327–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baunach, Dawn Michelle. 2012. Changing Same-Sex Marriage Attitudes in America from 1988 through 2010. Public Opinion Quarterly 76: 364–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, Robert W., Trisha Beuhring, Marcia L. Shew, Linda H. Bearinger, Renée E. Sieving, and Michael D. Resnick. 2000. The effects of race/ethnicity, income, and family structure on adolescent risk behaviors. American Journal of Public Health 90: 1879–84. [Google Scholar]

- Borch, Casey, Matthew West, and Gordon Gauchat. 2011. Go Forth and Multiply: Revisiting Religion and Fertility in the United States, 1984–2008. Religions 2: 469–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdette, Amy M., and Terrence D. Hill. 2009. Religious Involvement and Transitions into Adolescent Sexual Activities. Sociology of Religion: A Quarterly Review 70: 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdette, Amy M., Christopher G. Ellison, and Terrence D. Hill. 2005. Conservative Protestantism and Tolerance toward Homosexuals: An Examination of Potential Mechanisms. Sociological Inquiry 75: 177–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdette, Amy M., Terrence D. Hill, and Kyl Myers. 2015. Religion, Sexuality, & Sexual Health. In Handbook of the Sociology of Sexualities. Edited by John DeLamater and Rebecca F. Plante. New York: Springer, pp. 349–70. [Google Scholar]

- Campa, Mary I., and John J. Eckenrode. 2006. Pathways to Intergenerational Adolescent Childbearing in a High-Risk Sample. Journal of Marriage and Family 68: 558–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, Hae Yeon, and Myra Marx Ferree. 2010. Practicing Intersectionality in Sociological Research: A Critical Analysis of Inclusions, Interactions, and Institutions in the Study of Inequalities. Sociological Theory 28: 129–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clydesdale, Timothy T. 1999. Toward Understanding the Role of Bible Beliefs and Higher Education in American Attitudes Toward Eradicating Poverty, 1964–1996. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 38: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, Lester M., and Adrienne Testa. 2008. Sexual Health Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviours: Variations among a Religiously Diverse Sample of Young People in London, UK. Ethnicity and Health 13: 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosby, Richard A., and William L. Yarber. 2001. Perceived versus Actual Knowledge about Correct Condom Use among U.S. Adolescents: Results from a National Study. Journal of Adolescent Health 28: 415–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, Christina J., and Jeremy E. Fiel. 2016. The Effect(s) of Teen Pregnancy: Reconciling Theory, Methods, and Findings. Demography 53: 85–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgell, Penny, and Eric Tranby. 2007. Religious Influences on Understandings of Racial Inequality in the United States. Social Problems 54: 263–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edin, Kathryn, and Maria J. Kefalas. 2005. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood before Marriage. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Korie L. 2008. The Elusive Dream: The Power of Race in Interracial Churches. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elizabeth, Vivienne. 2017. Custody Stalking: A Mechanism of Coercively Controlling Mothers Following Separation. Feminist Legal Studies 25: 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, Aaron B., and Jenna Griebel. 2013. Understanding a Cultural Identity: The Confluence of Education, Politics, and Religion within the American Concept of Biblical Literalism. Sociology of Religion 74: 521–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, Jennifer J., Susheela Singh, and Lawrence B. Finer. 2007. Factors Associated with Contraceptive Use and Nonuse, United States, 2004. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 39: 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, Melanie A., Jennifer E. Wolford, Kym A. Smith, and Andrew M. Parker. 2004. The Effects of Advance Provision of Emergency Contraception on Adolescent Women’s Sexual and Contraceptive Behaviors. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 17: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsoulin, Margaret E. 2010. Gender Ideology and Status Attainment of Conservative Christian Women in the 21st Century. Sociological Spectrum 30: 220–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorry, Devon. 2019. Heterogeneous Consequences of Teenage Childbearing. Demography 56: 2147–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, Karen Benjamin, and Sarah Hayford. 2012. Race-Ethnic Differences in Sexual Health Knowledge. Race and Social Problems 4: 158–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadden, Jeffrey K. 1969. The Gathering Storm in the Churches. Garden City: Double Day. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, Elizabeth, Diana Gordon, Isabel Osgood-Roach, Jeffrey Jensen, and Jennifer Aengst. 2014. Conceptualizing Risk and Effectiveness: Women’s and Providers’ Perceptions of Nonsurgical Permanent Contraception in Portland, Oregon. Contraception 90: 128–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Jenny A., and Irene Browne. 2008. Sexual Needs, Control, and Refusal: How ‘Doing’ Class and Gender Influences Sexual Risk Taking. Journal of Sex Research 45: 233–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, Jennifer S., and Shamus Khan. 2020. Sexual Citizens: A Landmark Study of Sex, Power, and Assault on Campus. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, John P., and John P. Bartkowski. 2008. Gender, Religious Tradition, and Biblical Literalism. Social Forces 86: 1245–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, Jessica, and Perry N. Halkitis. 2019. Towards a More Inclusive and Dynamic Understanding of Medical Mistrust Informed by Science. Behavioral Medicine 45: 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, Rachel K., Jacqueline E. Darroch, and Susheela Singh. 2005. Religious Differentials in the Sexual and Reproductive Behaviors of Young Women in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health 36: 279–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Shamus R., Jennifer S. Hirsch, Alexander Wamboldt, and Claude A. Mellins. 2018. “I Didn’t Want to Be ‘That Girl’”: The Social Risks of Labeling, Telling, and Reporting Sexual Assault. Sociological Science 5: 432–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Michael R., Carol J. Rowland Hogue, and Laura M. D. Gaydos. 2007. Noncontracepting Behavior in Women at Risk for Unintended Pregnancy: What’s Religion Got to Do with It? Annals of Epidemiology 17: 327–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Natasha, and Joanna D. Brown. 2016. Access Barriers to Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives for Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 59: 248–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kusunoki, Yasamin, and Dawn M. Upchurch. 2011. Contraceptive Method Choice among Youth in the United States: The Importance of Relationship Context. Demography 48: 1451–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusunoki, Yasamin, Jennifer S. Barber, Elizabeth J. Ela, and Amelia Bucek. 2016. Black-White Differences in Sex and Contraceptive Use Among Young Women. Demography 53: 1399–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Bo Hyeong Jane, and Lisa D. Pearce. 2019. Understanding Why Religious Involvement’s Relationships with Education Varies by Social Class. Journal of Research on Adolescence 29: 369–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Bo Hyeong Jane, Lisa D. Pearce, and Kristen M. Schorpp. 2017. Religious Pathways from Adolescence to Adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 678–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefkowitz, Eva S., Tanya L. Boone, and Cindy L. Shearer. 2004. Communication with Best Friends about Sex-Related Topics during Emerging Adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 33: 339–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, Laura, John Santelli, and Sheila Desai. 2016. Understanding the Decline in Adolescent Fertility in the United States, 2007–2012. Journal of Adolescent Health 59: 577–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvicini, Peter G. 1999. Constructing ‘Composite Dialogs’ from Qualitative Data: Towards Representing and Managing Diverse Perspectives. In Annual Adult Education Research Conference, Proceedings of the 40th Annual Adult Education, DeKalb, IL, USA, 21–23 May 1999. De Kalb: Northern Illinois University. [Google Scholar]

- Manlove, Jennifer S., Elizabeth Terry-Humen, Erum N. Ikramullah, and Kristin A. Moore. 2003. The Role of Parent Religiosity in Teens’ Transitions to Sex and Contraception. Journal of Adolescent Health 39: 578–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manlove, Jennifer, Suzanne Ryan, and Kerry Franzetta. 2007. Teens’ Sexual Relationships: The Role Histories. Demography 44: 603–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Joyce A., Brady E. Hamilton, Michelle J. K. Osterman, Anne K. Driscoll, and Patrick Drake. 2018. Births: Final Data for 2016. CDC NVSS National Vital Statistics Reports 67: 7–54. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, Gladys M., and Joyce C. Abma. 2020. Sexual Activity and Contraceptive Use Among Teenagers Aged 15–19 in the United States, 2015–2017. CDC: National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS Data Brief 366: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- McCree, Donna Hubbard, Gina M. WIngood, Ralph DiClemente, Susan Davies, and Katherine F. Harrington. 2003. Religiosity and Risky Sexual Behavior in African-American Adolescent Females. Journal of Adolescent Health 33: 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Lisa, and Merav Gur. 2002. Religiousness and Sexual Responsibility in Adolescent Girls. Journal of Adolescent Health 31: 401–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Timothy. 2008. At Ease with Our Own Kind: Worship Practices and Class Segregation in American Religion. In Religion and Class in America: Culture, History, and Politices. Edited by Sean McLoud and Bill Mirola. Boston: Brill, pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ogland, Curtis P., and John P. Bartkowski. 2014. Biblical Literalism and Sexual Morality in Comparative Perspective: Testing the Transposability of a Conservative Religious Schema. Sociology of Religion: A Quarterly Review 75: 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, Lisa D., and Arland Thornton. 2007. Religious Identity and Family Ideologies in the Transition to Adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family 69: 1227–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, Lisa D., Jeremy E. Uecker, and Melinda Lundquist Denton. 2019. Religion and Adolescent Outcomes: How and Under What Conditions Religion Matters. Annual Review of Sociology 45: 201–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2009. A Religious Portrait of African Americans. Pew Research Religion and Public Life Project, Washington, DC. Available online: http://www.pewforum.org/2009/01/30/a-religious-portrait-of-african-americans/ (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Pew Research Center. 2014. Interpreting Scripture. Pew Research Center: Religious Landscape Study. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/interpreting-scripture/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Piper, Heather, and Pat Sikes. 2010. All teachers are vulnerable but especially gay teachers: Using composite fictions to protect research participants in pupil–teacher sex-related research. Qualitative Inquiry 16: 566–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, Kaitln N., Tyler J. Fuller, Amy A. Ayers, Danielle N. Lambert, Jessica M. Sales, and Gina M. Wingood. 2020. A Qualitative Exploration of Religion, Gender Norms, and Sexual Decision-Making within African American Faith-Based Communities. Sex Roles 82: 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, Cynthia, Taleria R. Fuller, William L. Jeffries, IV, Khiya J. Marshall, A. Vyann Howell, Angela Belyue-Umole, and Winifred King. 2018. Racism, African American Women, and Their Sexual and Reproductive Health: A Review of Historical and Contemporary Evidence and Implications for Health Equity. Health Equity 2: 249–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnerus, Mark D. 2005. Talking about Sex: Religion and Patterns of Parent-Child Communication about Sex and Contraception. The Sociological Quarterly 46: 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnerus, Mark D. 2007. Forbidden Fruit: Sex & Religion in the Lives of American Teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus, Mark D. 2010. Religion and Adolescent Sexual Behavior. In Religion, Families, and Health: Population-Based Research in the United States. Edited by Christopher G. Ellison and Robert A. Hummer. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Rocca, Corinne H., and Cynthia C. Harper. 2012. Do Racial and Ethnic Differences in Contraceptive Attitudes and Knowledge Explain Disparities in Method Use? Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 44: 150–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, Lisa, and Marci Lobel. 2018. Gendered Racism and the Sexual and Reproductive Health of Black and Latina Women. Ethnicity & Health 25: 367–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky, Sharon S., Mark D. Regnerus, and Margaret L. C. Wright. 2003. Coital Debut: The Role of Religiosity and Sex Attitudes in the Add Health Survey. Journal of Sex Research 40: 358–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostosky, Sharon Scales, Brian L. Wilcox, Margaret Laurie Comer Wright, and Brandy A. Randall. 2004. The Impact of Religiosity on Adolescent Sexual Behavior: A Review of the Evidence. Journal of Adolescent Research 19: 677–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Suzanne, Kerry Franzetta, and Jennifer Manlove. 2007. Knowledge, Perceptions, and Motivations for Contraception: Influence on Teens’ Contraceptive Consistency. Youth and Society 39: 182–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2018. Sexual Orientation and Social Attitudes. Socius 4: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2020. Religion across Axes of Inequality in the United States: Belonging, Behaving, and Believing at the Intersections of Gender, Race, Class, and Sexuality. Religions 11: 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwadel, Philip. 2011. The Effects of Education on Americans’ Religious Practices, Beliefs, and Affiliations. Review of Religious Research 53: 161–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwadel, Philip. 2020. The Politics of Religious Nones. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 59: 180–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shattuck, Rachel M. 2019. Preferences Against Nonmarital Fertility Predict Steps to Prevent Nonmarital Pregnancy. Population Research and Policy Review 38: 565–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Grace, Eric Vittinghoff, Jody Steinauer, and Christine Dehlendorf. 2011. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Contraceptive Method Choice in California. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 43: 173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekeste, Mehrit, Shawnika Hull, John F. Dovidio, Cara B. Safon, Oni Blackstock, Tamara Taggart, Trace S. Kershaw, Clair Kaplan, Abigail Caldwell, Susan B. Lane, and et al. 2018. Differences in Medical Mistrust Between Black and White Women: Implications for Patient-Provider Communication about PrEP. AIDS and Behavior 23: 1737–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton-Davis, Karen. 2015. Subverting Gendered Norms of Cohabitation: Living Apart Together for Women Over 45. Journal of Gender Studies 24: 104–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzman, Abigail, Jennifer S. Barber, Yasamin Kusunoki, and Paula England. 2017. Desire for and to Avoid Pregnancy During the Transition to Adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family 79: 1060–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilde, Melissa J. 2017. Complex religion: Interrogating Assumptions of Independence in the Study of Religion. Sociology of Religion 79: 287–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, Melissa J., and Lindsay Glassman. 2016. How Complex Religion Can Help Us Understand Politics in America. Annual Review of Sociology 42: 407–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, Melissa J., and Patricia Tevington. 2017. Complex Religion: Toward a Better Understanding of the Ways in Which Religion Intersects with Inequality. Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, Melissa J., Patricia Tevington, and Wensong Shen. 2018. Religious Inequality in America. Social Inclusion 6: 107–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, Tracey A., Courtney Miller, Samantha Rafie, Sharon Cohen Landau, and Sally Rafie. 2018. Older Teen Attitudes toward Birth Control Access in Pharmacies: A Qualitative Study. Contraception 97: 249–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, Rebecca. 2017. How members of parliament understand and respond to climate change. Sociological Review 66: 475–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, Rebecca. 2019. The use of composite narratives to present interview findings. Qualitative Research 19: 471–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancey, George, and Michael O. Emerson. 2018. Having Kids: Assessing Differences in Fertility Desires between Religious and Nonreligious Individuals. Christian Scholar’s Review 47: 263–79. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | As a reminder, we are presenting composite cases, comprised of the experiences and expressions of multiple women in each category, and as such, the names are pseudonyms. |

| Reproductive Female Biology Knowledge | Percent Correct |

|---|---|

| 39% |

| 64% |

| 68% |

| Condom Knowledge | |

| 81% |

| 61% |

| 93% |

| Lower Parental Education (n = 669) | Higher Parental Education (n = 271) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Range | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Difference |

| Female reproductive biology knowledge | 0–3 | 1.65 | 0.90 | 1.87 | 0.96 | * |

| Condom knowledge | 1–3 | 2.35 | 0.68 | 2.40 | 0.71 | |

| Biblical literalism | 0–1 | 0.24 | 0.24 | |||

| Personal religiosity | 1–5 | 3.28 | 1.21 | 3.30 | 1.19 | |

| Religious service attendance | 1–6 | 2.97 | 1.64 | 3.48 | 1.67 | * |

| Age | ||||||

| 18 years | 0–1 | 0.40 | 0.44 | |||

| 19 years | 0–1 | 0.51 | 0.47 | |||

| 20 years | 0–1 | 0.09 | 0.09 | |||

| Race | ||||||

| Black (ref = White) | 0–1 | 0.41 | 0.21 | * | ||

| Family Structure | ||||||

| Two parent family | 0–1 | 0.45 | 0.71 | * | ||

| Single biological parent only | 0–1 | 0.45 | 0.25 | * | ||

| Other | 0–1 | 0.10 | 0.04 | * | ||

| Reproductive Knowledge Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

| Lower Parental Education (n = 669) | Higher Parental Education (n = 271) | Lower Parental Education (n = 669) | Higher Parental Education (n = 271) | |

| Religion Measures | ||||

| Biblical literalism | −0.06 | −0.30 * | −0.23 | −0.19 |

| (0.09) | (0.14) | (0.15) | (0.17) | |

| Private religiosity | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.05 |

| (0.04) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.07) | |

| Religious service attendance | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.05) | |

| Religion and Race Interactions | ||||

| Biblical literalism * Black | 0.28 | −0.40 | ||

| (0.19) | (0.31) | |||

| Private religiosity * Black | 0.01 | 0.18 | ||

| (0.09) | (0.15) | |||

| Religious serv attend * Black | 0.03 | 0.05 | ||

| (0.06) | (0.10) | |||

| Control Variables | ||||

| Age (Ref: 18 years) | ||||

| 19 years | 0.14 + | −022 + | 0.14 + | −0.22 * |

| (0.08) | (0.11) | (0.08) | (0.11) | |

| 20 years | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| (0.13) | (0.19) | (0.13) | (0.20) | |

| Race (Ref: White) | ||||

| Black | −0.40 *** | −0.41 ** | −0.60 * | −1.17 |

| (0.09) | (0.15) | (0.29) | (0.63) | |

| Family Structure (Ref: Two parents) | ||||

| Single bio parent only | −0.27 *** | −0.02 | −0.27 *** | −0.02 |

| (0.08) | (0.13) | (0.08) | (0.13) | |

| Other | −0.31 * | 0.26 | −0.32 * | 0.31 |

| (0.13) | (0.28) | (0.13) | (0.28) | |

| Intercept | 1.91 *** | 2.23 *** | 1.93 *** | 2.31 *** |

| (0.12) | (0.18) | (0.14) | (0.19) | |

| R-squared | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Condom Knowledge | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

| Lower Parental Education (n = 669) | Higher Parental Education (n = 271) | Lower Parental Education (n = 669) | Higher Parental Education (n = 271) | |

| Religion Measures | ||||

| Biblical literalism | −0.10 | −0.05 | −0.06 | −0.02 |

| 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.13 | |

| Private religiosity | −0.003 | −0.0001 | −0.01 | −0.07 |

| 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |

| Religious service attendance | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.06+ | −0.02 |

| 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |

| Religion and Race Interactions | ||||

| Biblical literalism * Black | −0.05 | −0.25 | ||

| 0.15 | 0.24 | |||

| Private religiosity * Black | 0.06 | 0.44 *** | ||

| 0.07 | 0.11 | |||

| Religious serv attend * Black | 0.09 * | 0.06 | ||

| 0.04 | 0.08 | |||

| Control Variables | ||||

| Age (Ref: 18 years) | ||||

| 19 years | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.03 |

| 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.08 | |

| 20 years | −0.11 | 0.13 | −0.11 | 0.17 |

| 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.15 | |

| Race (Ref: White) | ||||

| Black | −0.19 ** | 0.03 | −0.69 ** | −1.81 |

| 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.48 | |

| Family Structure (Ref: Two parents) | ||||

| Single bio parent only | −0.02 | −0.14 | −0.03 | −0.15 |

| 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.10 | |

| Other | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.22 | |

| Intercept | 2.53 *** | 2.55 *** | 2.66 *** | 2.72 *** |

| 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.15 | |

| R-squared | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Religious | Not Religious | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Black women | Higher parental education | ** Too few women in this subgroup to analyze | Sexual activity is connected to maturity and to adulthood project—must be able to understand risks (pregnancy and STDs) and to take them seriously. |

| Lower parental education | Sexual activity is connected to maturity and to adulthood project, rather than to religious project (which is still salient). | Sexual activity is framed as risky, yet contraceptive use is inconsistent. | |

| White women | Higher parental education | Abstinence for them to accomplish their own religious project, but choice and pregnancy avoidance for others. | Emphasis on choice (for themselves and others) in becoming sexually active and pregnancy avoidance. |

| Lower parental education | Abstinence is understood in moral/absolute terms as part of their religious project, and birth control is viewed with skepticism. | Emphasis on choice (for themselves and others) in becoming sexually active and protection against STDs and pregnancy. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krull, L.M.; Pearce, L.D.; Jennings, E.A. How Religion, Social Class, and Race Intersect in the Shaping of Young Women’s Understandings of Sex, Reproduction, and Contraception. Religions 2021, 12, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010005

Krull LM, Pearce LD, Jennings EA. How Religion, Social Class, and Race Intersect in the Shaping of Young Women’s Understandings of Sex, Reproduction, and Contraception. Religions. 2021; 12(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrull, Laura M., Lisa D. Pearce, and Elyse A. Jennings. 2021. "How Religion, Social Class, and Race Intersect in the Shaping of Young Women’s Understandings of Sex, Reproduction, and Contraception" Religions 12, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010005

APA StyleKrull, L. M., Pearce, L. D., & Jennings, E. A. (2021). How Religion, Social Class, and Race Intersect in the Shaping of Young Women’s Understandings of Sex, Reproduction, and Contraception. Religions, 12(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010005