2. Literature Review

Many research studies have been done on tax evasion over the past few decades (

Collymore 2020a). One of the earliest, best, and most comprehensive theoretical studies was done by

Martin Crowe (

1944), a Catholic priest who wrote a doctoral dissertation on the ethical duty of paying just taxes. He examined 500 years of religious and philosophical writings on tax evasion; most of them were written in Latin. Thus, he offered the English-speaking world an opportunity to explore formerly unknown literature.

The Bible (Matthew 22:17, 21; Romans 13:1–2) supported the view that individuals had a moral duty to pay taxes to the secular authority (

Schansberg 1998). Some Catholic and other Christian scholars made an exception for rulers who were corrupt (

Crowe 1944). Other scholars made exceptions in cases where there was an inability to pay (

LeCard 1869;

Morales 1998) or where the tax burden was too high (

Crowe 1944;

McGee 2012a). Some other scholars held the view that there was little or no duty task to pay taxes (

Spooner 1870;

Block and Torsell 2020). More recent scholarship has applied just war theory to tax evasion and held that there may be an ethical duty

not to support an unjust war (

Pennock 1998).

The Christian literature on tax evasion is diverse. At one extreme is the Mormon view, which holds that tax evasion can never be justified. A review of the Mormon literature did not find a single exception that would justify tax evasion (

Smith and Kimball 1998). However, a study of Mormon university students showed that they were more flexible on the topic, justifying tax evasion in several cases (

McGee and Smith 2007), in particular in cases where the government takes part in human rights abuses, but also in other cases, such as where the government is corrupt or where the tax funds are wasted.

Most of the Christian literature would permit tax evasion in certain situations, most notably where the government is corrupt, where there is an inability to pay, or when tax rates are excessively high (

McGee 2012a, pp. 201–10;

McGee and Benk 2019). Some Christian literature takes a classic liberal approach (

Gronbacher 1998).

The literature of the Baha’i religion is nearly as strict as that of the Mormons, holding that tax evasion can only be justified when the government oppresses members of the Baha’i faith. (

DeMoville 1998). They believe that they have an ethical duty to pay taxes, even to Hitler, as long as he does not persecute members of their faith.

The Jewish literature is highly opposed to tax evasion, at least the majority of the time. There are mainly three reasons for this strong aversion to tax evasion. There is a strain of opinion in the Jewish literature that one must never do anything to disparage another Jew. A second reason not to evade taxes is that doing so might cause one to go to prison, making it difficult or impossible to perform mitzvot (good works). The third reason might be summarized as “the law is the law” (

Cohn 1998,

2012;

Tamari 1998), which means that there is always a duty to obey every law.

All three of these views are open to criticism. It could be argued that there is no moral duty to behave in a certain manner just so that some segment of the general public will not look down on other members of a religious or ethnic group. An extreme case would be that the Jews have a moral duty to pay taxes, even to the likes of Hitler, so that other Jews in the community will not be viewed as tax evaders.

The view that paying taxes is required in order that they will not be prevented from performing good deeds also falls apart upon analysis. It might actually be possible to do more good deeds in a jail, where prisoners are compelled to act so in repentance.

The claim that “the law is the law” also does not hold up to analysis. The example of Hitler given above may be used again to show the weakness of this position. Martin

Luther King (

1963) and others (

Thoreau 1849) have argued that there is a moral duty to defy bad laws.

Relevant also is the confrontation “if you don’t like it, leave it”. It is very popular in the United States at the moment, not so much for tax evasion, but for individuals who strongly dislike whoever the current president is. This hostility is not necessarily Jewish or Christian in nature but a secular one. The problem with such a strong discontent is that individuals who leave one regime because they do not like the tax system simply enter into another regime and a new tax system that they may not like, either. For those who feel that all taxation is nothing short of theft (because it involves the confiscation of a portion of the fruits of one’s labor), the “if you don’t like it, leave” stance is akin to telling a slave that if you do not like your current slave master, you can go to work for one you like better.

The Islamic literature is seemingly at both ends of the spectrum, at least on the surface (

McGee 2012b). On one end, two Muslim scholars have the opinion that there is no moral obligation to pay taxes that are based on income or that cause prices to rise. Thus, there is no moral duty to pay income taxes, sales taxes, or tariffs, which are another form of taxation (

Ahmad 1995;

Yusuf 1971).

At the other end of the spectrum, another Muslim scholar interprets the Muslim literature to state that tax evasion is never justified, but only in situations where the government is run by Sharia law, because evading taxes in such a case would be stealing from Allah (

Jalili 2012). However, this scholar avoided discussing whether tax evasion would be unethical in a country that is not run by Sharia law.

In recent years, there have been several empirical papers on the ethics of tax evasion. One set of studies involved the distribution of an 18-statement survey to various groups. Each statement began, “Tax evasion would be ethical if …”. The sentences ended with a variety of reasons that have been given in the past to justify tax evasion. Many of the questions used in these surveys were based on the issues that

Crowe (

1944) uncovered in his examination of Christian literature on the subject.

McGee (

2012a) added three questions dealing with various human rights abuses.

In general, these studies found that some opinions to justify tax evasion were more robust than others, and that there was a cognizable support for tax evasion, but then, that opposition to evasion was usually quite strong. The instances where tax evasion was most strongly justified were in cases where the government was involved in human rights abuses, where the government was corrupt, where tax rates were too high, or where there was an inability to pay. Tax evasion was found to be more justifiable in cases where the taxpayer did not receive much in exchange for the tax payments, and was less justifiable in cases where taxpayers received substantial benefits, or where the government spent tax funds efficiently (

Kandri and Mamuti 2019;

Collymore 2020b). Many of these studies are summarized in

McGee (

2012a).

Several studies over the years have found that evasion increases as tax rates increase (

Alm et al. 1992;

Slemrod 1985), which makes sense because the risk–reward ratio increases. Another study found that tax evasion decreases as audits increase (

Cebula and Saadatmand 2005).

Demographic variables were sometimes examined to determine whether certain groups had varying opinions. In most studies, women were either significantly more opposed to tax evasion than men (

Collymore 2020b;

McGee and Guo 2007;

McGee et al. 2008), or both genders were equally opposed to tax evasion (

McGee et al. 2012b). In some cases, men were found to be significantly more opposed to tax evasion (

McGee et al. 2011). The studies that examined age demography generally found that young people were less opposed to tax evasion than older people (

McGee 2012a, pp. 441–49). Level of education sometimes was correlated to acceptance of tax evasion, but the various studies conducted over the years have reached different conclusions. In some cases, the more education a person had, the higher the aversion to tax evasion, but in other cases, the relationship was just the opposite (

McGee 2012a, pp. 451–57).

Another group of studies used World Values Survey data to discover the extent of support for tax evasion. The World Values Surveys involved asking thousands of people in dozens of countries questions on a wide range of subjects. One question was related to whether it would be justified to cheat on taxes if you could. Respondents were asked to pick a number from 1 to 7 to signify the extent of their agreement or disagreement with the statement.

These studies generally unveiled that there was fairly strong opposition to tax evasion, although the extent varied by country. People in the former Soviet Union countries or Soviet satellite countries tended to be less opposed to tax evasion than people in western European countries or the United States (

Alm et al. 2006;

McGee and Maranjyan 2008;

McGee et al. 2008,

2012a;

McGee 2012a). Demographic differences were also found. Although women were often more opposed to tax evasion, the difference in mean scores was not always significant. Older people tended to be more opposed to tax evasion than younger people. Views toward tax evasion were regional, in the sense that opposition was stronger in some geographic locations than others (

Alm and Torgler 2006;

Alm et al. 2006;

Alm and Martinez-Vazquez 2010;

McGee 2012a;

Torgler 2012).

Benk et al. (

2009) surveyed Turkish business students on six ethical topics that were covered in the World Values Surveys. They concluded that paying cash to avoid paying a sales/VAT tax was substantially more attractive than cheating on taxes if you have a chance. Women were generally more opposed to evading sales/VAT taxes by paying cash than were men.

5. Conclusions

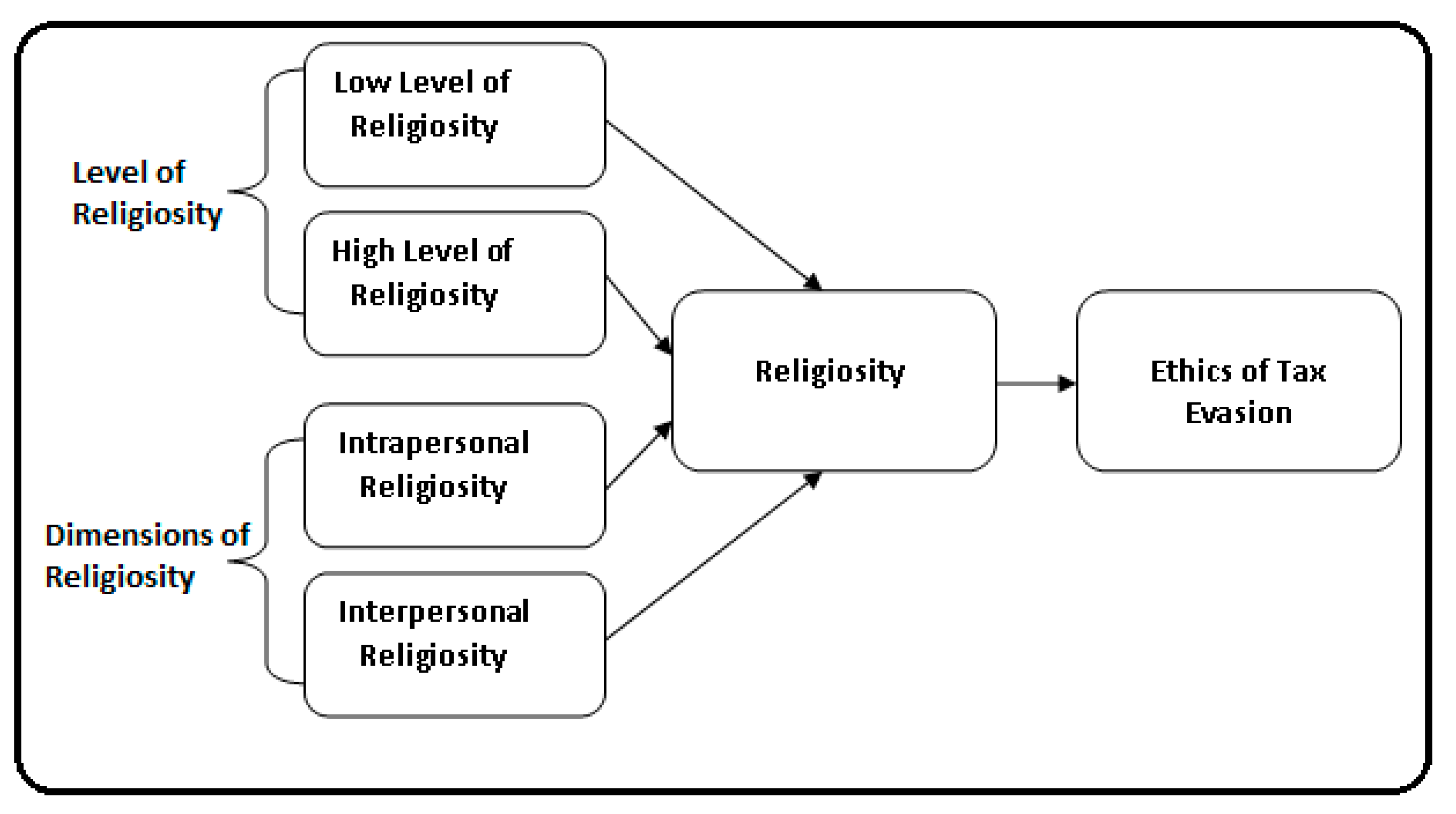

This empirical study finds that there is an important relationship between both interpersonal and intrapersonal religiosity as well as views on the ethics of tax evasion. The research uncovered that various reasons used to justify tax evasion had been put forward by participants in similar circumstances with strong feelings against the government. This, however, cannot be construed as a conclusive finding to show that those who have deployed justifications throughout the 500 years and in different nations have done so. The strongest assertions to justify tax evasion appeared to be the ones that involve human rights abuses. On the other hand, the weakest justifications were those where the taxpayer benefited from the taxes paid or where the funds were spent intelligently, where the risk of getting caught was low, or where everybody else was doing it.

The relative strength of the various reasons that have been advanced to justify tax evasion over the years remain similar to the findings of other studies based on the

McGee (

2012a) survey instrument, although the ranking of the 18 arguments may differ slightly from survey to survey. The present study, however, differs in that it has aimed to seek the opinions of a wider segment of the population. Many (not all) of the McGee surveys gathered student opinions, which is a subset of the general population. Thus, the findings of the present survey may be seen as more representative of the general population.

This current research can be replicated and expanded in various ways. Interpersonal and intrapersonal religiosity has thus far been underexplored in the literature. For that reason alone, this topic is ripe for future study. The present study did not attempt to investigate whether differences may exist for some of the demographic variables, such as age, gender, education, or marital status. Some of the McGee studies have explored these variables as part of the various 18-statement surveys but exploring male and female differences or differences based on age, marital status, or education level have not been done in the areas of interpersonal and intrapersonal religiosity.

The present study explored the Turkish opinion. Turkey is more than 98 percent Muslim, mostly Sunni Muslim (

Wikipedia 2020). The present study could be replicated in other Sunni Muslim countries as well as Shia Muslim countries and non-Muslim countries to see whether the results are similar or different. Several studies have examined religious differences of opinion on the ethics of tax evasion in general, often using the 18-statement survey, but that survey did not include religiosity questions. Thus, examining the religiosity of other religions, such as Christianity, Buddhism, and Hinduism, among others, might be fruitful. Prior research has found that differences of opinion exist between and among the various religions (

Bose 2012;

Cohn 1998,

2012;

DeMoville 1998;

Jalili 2012;

McGee 2012a;

Mohd Ali 2013;

McGee and Benk 2019;

Schansberg 1998;

Smith and Kimball 1998;

Tamari 1998;

Worthington et al. 2003) when it comes to tax evasion, but religiosity has not been the focus, therefore largely underexplored. Indeed, it is quite possible that Baptist Christians would have different mean scores than Catholic Christians, for example, or that Buddhists would have different views than Hindus or Muslims.