Religiosity and Generosity: Multi-Level Approaches to Studying the Religiousness of Prosocial Actions

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Philanthropy, Generosity, and Prosociality

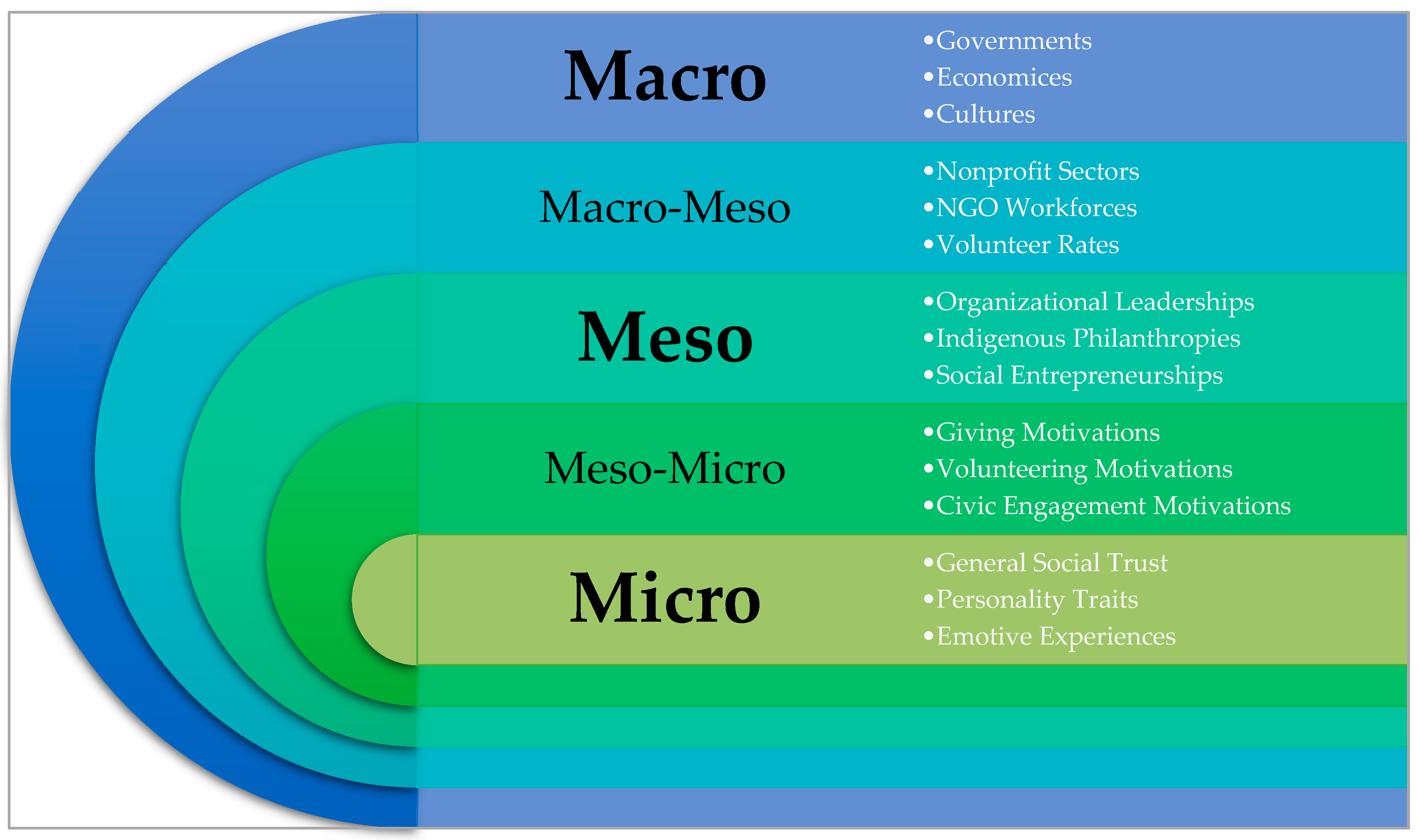

1.2. Levels of Analysis

1.2.1. Macro-Level Generosity

1.2.2. Meso-Level Generosity

1.2.3. Micro-Level Generosity

2. Methods

2.1. Discovery Search

2.2. Systematic Search

2.2.1. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion

2.2.2. Voluntas

2.3. Informational Interviews

2.3.1. Researcher Positionality

2.3.2. Informational Interview Process

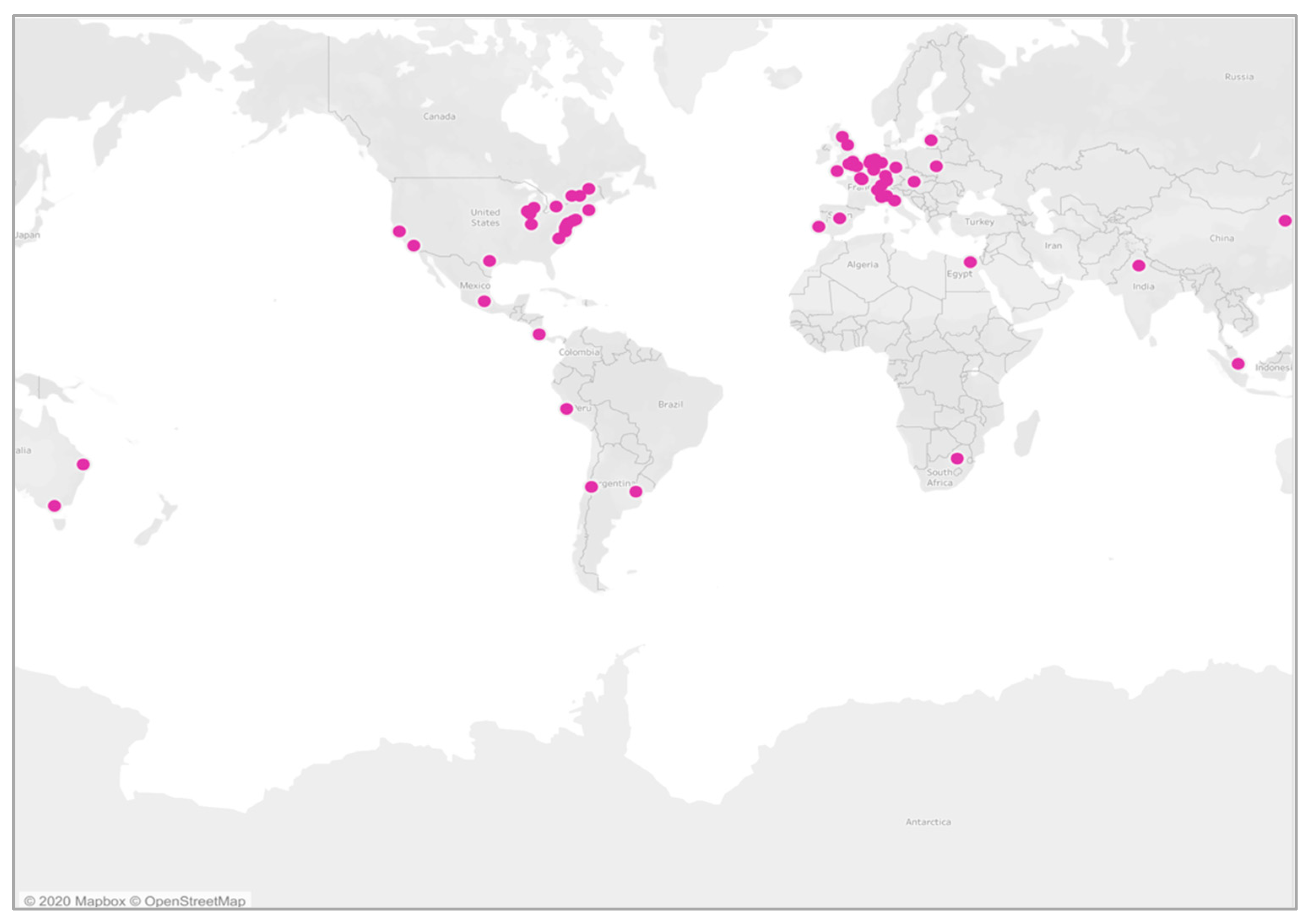

2.4. Geographic Scope

3. Results

3.1. Discovery Search Results

3.1.1. Macro-Level Intersections

Religious affiliation and attendance at faith services has been a strong predictor of giving and volunteering, and religion is still the primary destination of philanthropy in many countries. However, religious attachment (particularly among Christians) is declining rapidly in many European and North and South American countries, and the composition of religions among once quite homogenous populations is changing due to immigration. Globally, Islam is significant for its growth.

Macro-Level Religion and Trust

Macro-Level Religion and Volunteering

Macro-Level Religion and Civil Society

3.1.2. Meso-Level Intersections

Meso-Level Religion, Giving, and Volunteering

Meso-Level Religion and Civic Engagement

Meso-Level Religion and NGOs

Meso-Level Religion and Conflict

3.1.3. Micro-Level Intersections

Micro-Level Religion, Giving, and Volunteering

Religion, Altruism, and Helping

3.1.4. Summary of Discovery Results

3.2. Systematic Search Results

3.2.1. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion

3.2.2. Voluntas

3.3. Informational Interviews

3.3.1. Philanthropy

3.3.2. Generosity

3.3.3. Religiosity

3.3.4. Spirituality

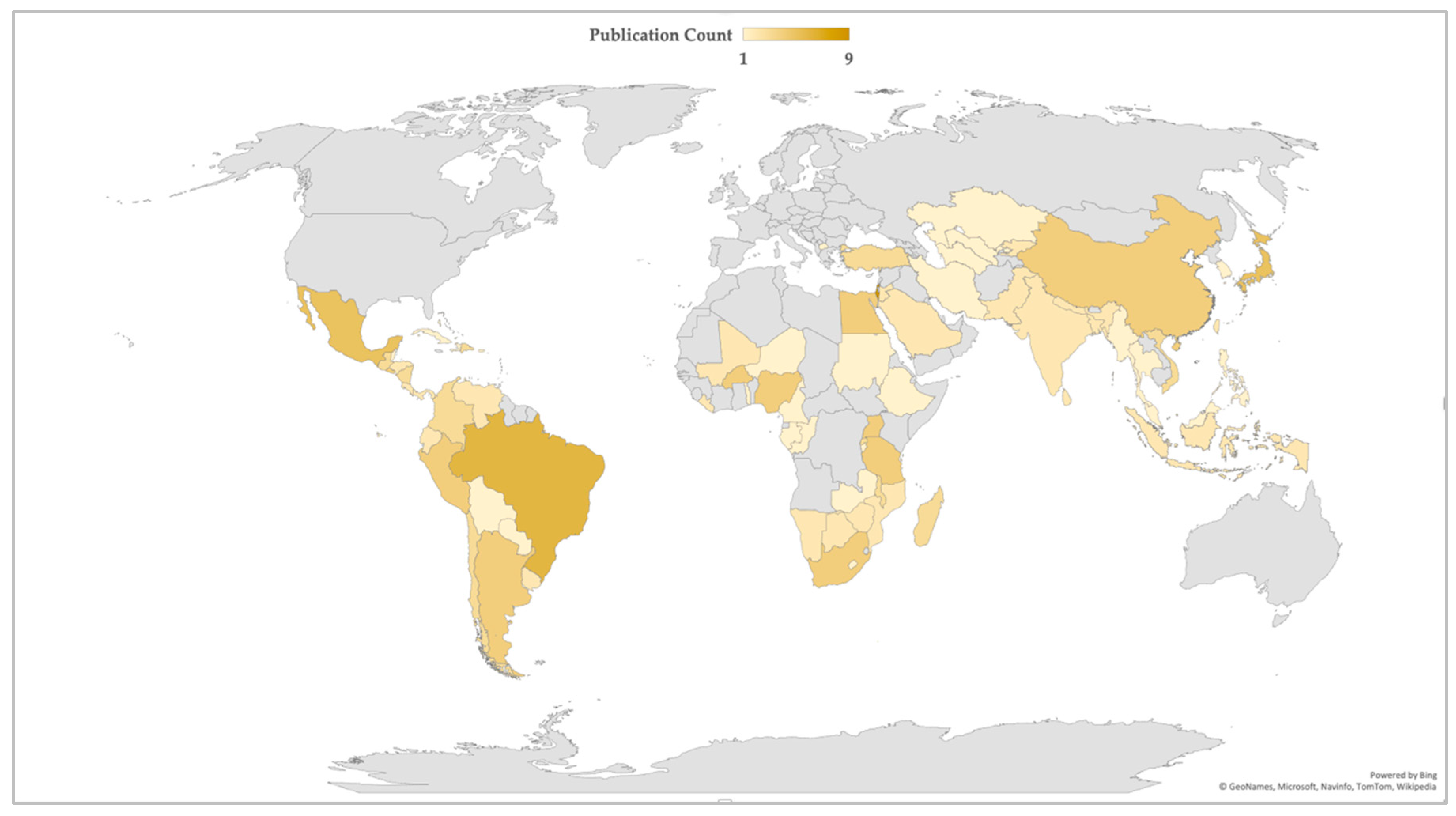

3.4. Geographic Scope

3.4.1. Africa

3.4.2. Asia

3.4.3. Latin America

Studies of Latin American philanthropic practices reveal diverse mechanisms for mutual aid and collective assistance practised among those who sought to survive economic poverty and preserve their cultural traditions in the face of political or ethnic persecution (Sanborn 2005, 7). For example, the ayllu (or wachu in Peru) has been revitalized by indigenous societies in Bolivia and Ecuador. Ayllu is an ancient concept of community based on territorial federation, characterized by rotating leadership, extensive consultation, with the goals of communal consensus and an equitable distribution of resources (Korovkin 2001, 38). Béjar (1997, 379) shows that there are thousands of what he calls peasant and native communities in Peru, involved in “communal work, and in use and free disposition of land, as well as in economic and administrative operation”. These autonomous organizations have substituted or complemented the state’s role in the building and maintenance of mainly communication, irrigation channels and schools.

3.4.4. Middle East

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abreu, Madalena Eça De, Raul M. S. Laureano, Sharifah Faridah Syed Alwi, Rui Vinhas Da Silva, and Pedro Dionísio. 2015. Managing Volunteerism Behaviour: The Drivers of Donations Practices in Religious and Secular Organisations. Journal of General Management 40: 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamek, Margaret, Messay Gebremariam, and Abraham Zelalem. 2019. Aging in Rural Ethiopia: Impact on Filial Responsibility and Intergenerational Solidarity. Innovation in Aging 3 Suppl. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, Gary J., and Stephen Offutt. 2017. The Gift Economy of Direct Transnational Civic Action: How Reciprocity and Inequality Are Managed in Religious ‘Partnerships’. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 600–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Amy L., Roslyn Richardson, Carol Plummer, Christopher G. Ellison, Catherine Lemieux, Terrence N. Tice, and Bu Huang. 2013. Character Strengths and Deep Connections Following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita: Spiritual and Secular Pathways to Resistance Among Volunteers. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 537–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, Tade Akin, and Bhekinkosi Moyo, eds. 2013. Giving to Help, Helping to Give: The Context and Politics of African Philanthropy. Dakar-Fann: Amalion Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Akboga, Sema, and Engin Arik. 2019. The Ideological Convergence of Civil Society Organizations and Newspapers in Turkey. Voluntas 31: 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagidede, Paul, William Baah-Boateng, and Edward Nketiah-Amponsah. 2013. The Ghanaian Economy: An Overview. Ghanaian Journal of Economics 1: 4–34. [Google Scholar]

- Alias, Siti Moormi, and Maimunah Ismail. 2013. Conceptualizing Philanthropic Behaviour and Its Antecedents of Volunteers in Health Care. Paper presented at Graduate Research in Education, Seri Kembangan, Malaysia, June 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Almog-Bar, Michal, and Ester Zychlinski. 2014. Collaboration between Philanthropic Foundations and Government. International Journal of Public Sector Management 27: 201–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, Phillipp, Deniz Gunce Demirhisar, and Jacob Mwathi Mati. 2016. Social Movements in the Global South. Some Theoretical Considerations. In Emulations: Perspectives on Social Movements, Voices from the South. Louvain-la-Neuve: UCL Presses universitaires de Louvain, pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Shawna L. 2010. Conflict in American Protestant Congregations. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, Etin. 2004. ‘Directed’ Women’s Movements in Indonesia: Social and Political Agency from Within. Hawwa 2: 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, Etin. 2010. Gendered Space and Shared Security: Women’s Activism in Peace and Conflict Resolution in Indonesia. In Women and Islam. Women and Religion in the World. Westport: Praeger, pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Appe, Susan, and Allison Schnable. 2019. Don’t Reinvent the Wheel: Possibilities for and Limits to Building Capacity of Grassroots International NGOs. Third World Quarterly 40: 1832–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, Enrique. 2010. The Relationship Between Latino Culture and Giving Opportunities. Ph.D. dissertation, American Jewish University, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, Adam. 2015. Witchcraft, Justice, and Human Rights in Africa: Cases from Malawi. African Studies Review 58: 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswad, el-Sayed. 2015. From Traditional Charity to Global Philanthropy: Dynamics of the Spirit of Giving and Volunteerism in the United Arab Emirates. Horizons in Humanities and Social Sciences 1: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Audette, Andre, and Christopher Weaver. 2016. Filling Pews and Voting Booths: The Role of Politicization in Congregational Growth. Political Research Quarterly 69: 245–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audette, Andre P., Mark Brockway, and Rodrigo Castro Cornejo. 2020. Religious Engagement, Civic Skills, and Political Participation in Latin America. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 59: 101–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, Thad. 2017. Giving USA Special Report on Giving to Religion. Giving USA. Available online: https://givingusa.org/just-released-giving-usa-special-report-on-giving-to-religion/ (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Awofeso, Niyi, Mohammed Guleid, and Moyosola Abiodun (Angel II) Bamidele. 2017. Perceptions and Motivations of Volunteers in the United Arab Emirates -Health Services & Implications. Worldwide Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Research 3: 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Babis, Deby, Agnes Meinhard, and Ida Berger. 2018. Exploring Involvement of Immigrant Organizations With the Young 1.5 and 2nd Generations: Latin American Associations in Canada and Israel. Journal of International Migration and Integration 20: 479–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Janel Kragt. 2011. Molding Mission: Collective Action Frames and Sister Church Participation. The Review of Faith & International Affairs 9: 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Sandra L. 2005. Black Church Culture and Community Action. Social Forces 84: 967–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Sandra L. 2013. Black Church Giving: An Analysis of Ideological, Programmatic, and Denominational Effects. SAGE Open 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, Michael N, and Janice Gross Stein. 2012. Sacred Aid: Faith and Humanitarianism. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassoli, Matteo. 2017. Catholic Versus Communist: An Ongoing Issue—The Role of Organizational Affiliation in Accessing the Policy Arena. Voluntas 28: 1135–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassous, Michael. 2015. What Are the Factors That Affect Worker Motivation in Faith-Based Nonprofit Organizations? Voluntas 26: 355–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béjar, Héctor. 1997. Non-Governmental Organisations and Philanthropy: The Peruvian Case. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 8: 371–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, René, and Theo Schuyt. 2008. And Who Is Your Neighbor? Explaining Denominational Differences in Charitable Giving and Volunteering in the Netherlands. Review of Religious Research 50: 74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Beldad, Ardion, Jordy Gosselt, Sabrina Hegner, and Robin Leushuis. 2015. Generous But Not Morally Obliged? Determinants of Dutch and American Donors’ Repeat Donation Intention (REPDON). Voluntas 26: 442–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellegy, Benjamin, Muriel Asseraf, Caroline Hartnell, and Heather Knight. 2018. The Global Landscape of Philanthropy. Sao Paulo: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Matthew R., and Christopher J. Einolf. 2017. Religion, Altruism, and Helping Strangers: A Multilevel Analysis of 126 Countries. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 323–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyerlein, Kraig, and Mark Chaves. 2003. The Political Activities of Religious Congregations in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42: 229–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyerlein, Kraig, Jenny Trinitapoli, and Gary Adler. 2011. The Effect of Religious Short-Term Mission Trips on Youth Civic Engagement. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 780–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielefeld, Wolfgang, and William Suhs Cleveland. 2013. Defining Faith-Based Organizations and Understanding Them Through Research. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 42: 442–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, Warren. 2019. 2019 State of Giving. Winchester: Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability (ECFA). Available online: https://www.ecfa.org/Content/2016-State-of-Giving (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Body, Alison, and Beth Breeze. 2016. What Are ’unpopular Causes’ and How Can They Achieve Fundraising Success? International Journal of Nonproift and Voluntary Sector Marketing 21: 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bok, Jared. 2020. Inner-Worldly and Other-Worldly Outreach: Organizational Repertoires of Protestant Mission Agencies. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 17: 159–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchgrevink, Kaja. 2017. NGOization of Islamic Charity: Claiming Legitimacy in Changing Institutional Contexts. Voluntas 31: 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, Erica. 2012. Disquieting Gifts: Humanitarianism in New Delhi. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brass, Jennifer N. 2017. Allies or Adversaries: NGOs and the State in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, Oonagh. 2016. Minding the Pennies: Global Trends in the Regulation of Charitable Fundraising. In The Routledge Companion to Philanthropy. Edited by Tobias Jung, Susan D. Phillips and Jenny Harrow. Philadelphia: Routledge, pp. 229–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton, Luke. 2015. Resurrecting Democracy: Faith, Citizenship, and the Politics of a Common Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton, Luke. 2019. Christ and the Common Life: Political Theology and the Case for Democracy. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Timothy T. 2009. The Economics of Religious Altruism: The Role of Religious Experience. State College: Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). Available online: http://www.thearda.com/rrh/papers/altruism.asp (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Butcher, Jacqueline. 2010. Volunteering in Developing Countries. In Third Sector Research. New York: Springer, pp. 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, Jacqueline, and Christopher J. Einolf, eds. 2017. Perspectives on Volunteering Voices from the South. Nonprofit and Civil Society Studies. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, Jacqueline, and Santiago Sordo. 2016. Giving Mexico: Giving by Individuals. Voluntas 27: 322–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, Matti Ullah, Yu Hou, Kamran Ahmed Soomro, and Daniela Acquadro Maran. 2017. The ABCE Model of Volunteer Motivation. Journal of Social Service Research 43: 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadge, Wendy, and Mary Ellen Konieczny. 2014. ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’: The Significance of Religion and Spirituality in Secular Organizations. Sociology of Religion 75: 551–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadge, Wendy, Peggy Levitt, and David Smilde. 2011. De-Centering and Re-Centering: Rethinking Concepts and Methods in the Sociological Study of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 437–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calfano, Brian R., and Elizabeth A. Oldmixon. 2018. The Influence of Institutional Salience on Political Attitudes and Activism among Catholic Priests in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57: 634–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cametella, Andrea, Ines Gonzalez Bombal, and Mario Roitter. 1998. Argentina: Defining the Nonprofit Sector. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies. Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2014/09/Argentina_CNP_WP33_1998.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Campbell, David A., and Ali Çarkoğlu. 2019. Informal Giving in Turkey. Voluntas 30: 738–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çarkoğlu, Ali, Selim Erdem Aytaç, and David A. Campbell. 2017. Determinants of Formal Giving in Turkey. Journal of Muslim Philanthropy & Civil Society 1: 74–93. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Vernon B., and Jerry Marx. 2007. What Motivates African-American Charitable Giving. Administration in Social Work 31: 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, John. 2016. Comparing Nonprofit Sectors Around the World: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It? Journal of Nonprofit Education and Leadership 6: 187–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavendish, James C. 2002. Church-Based Community Activism: A Comparison of Black and White Catholic Congregations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 39: 371–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakamera, Chengete, and Paul Alagidede. 2018. Electricity Crisis and the Effect of CO2 Emissions on Infrastructure-Growth Nexus in Sub Saharan Africa. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 94: 945–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, Mark, and Allison J. Eagle. 2016. Congregations and Social Services: An Update from the Third Wave of the National Congregations Study. Religions 7: 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, Mark, and Sharon L Miller. 2008. Financing American Religion. Lanham: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jose Chiu-C, and Min-Hsiu Chiang. 2010. Policy Foresight on the Institutional Reform of Civil Service Training for Taiwan’s High-Rank Officials. Working Paper. Portland, OR. Available online: https://fdocuments.in/document/policy-foresight-on-the-institutional-reform-of-civil-foresight-on-the-institutional.html (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Chilimampunga, Charles, and George Thindwa. 2012. The Extent and Nature of Witchcraft-Based Violence against Children, Women and the Elderly in Malawi. Lilongwe: Association of Secular Humanists and Royal Norwegian Embassy. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Meehee, Mark A. Bonn, and Su Jin Han. 2018. Generation Z’s Sustainable Volunteering: Motivations, Attitudes and Job Performance. Sustainability 10: 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnaan, Ram. 2010. Sacred Places: The Economic Halo Effect of Historic Sacred Places. Philadelphia: Partners for Sacred Places. Available online: https://sacredplaces.org/uploads/files/16879092466251061-economic-halo-effect-of-historic-sacred-places.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Cnaan, Ram A., and Stephanie C. Boddie. 2001. Philadelphia Census of Congregations and Their Involvement in Social Service Delivery. Social Service Review 75: 559–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cnaan, Ram A., and Daniel W. Curtis. 2013. Religious Congregations as Voluntary Associations An Overview. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 42: 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnaan, Ram A., Anne Birgitta Pessi, Sinisa Zrinscak, Femida Handy, Jeffrey L. Brudney, Henrietta Grönlund, DebbieHaski Haski-Leventhal, Kirsten Holmes, Lesley Hustinx, Chul Hee Kang, and et al. 2012. Student Values, Religiosity, and Pro-Social Behaviour. Diaconia 3: 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, James R., Deborah McFarland, and Gary R. Gunderson. 2014. Mapping Religious Resources for Health: The African Religious Health Assets Programme. In Religion as a Social Determinant of Public Health. Edited by Ellen L. Edler. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Steven M., Jim Gerstein, and J. Shawn Landres. 2014. Connected to Give: Synagogues and Movements, Findings from the National Study of American Jewish Giving. Los Angeles: Jumpstart. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Adam B., Gina L. Mazza, Kathryn A. Johnson, Craig K. Enders, Carolyn M. Warner, Michael H. Pasek, and Jonathan E. Cook. 2017. Theorizing and Measuring Religiosity Across Cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 43: 1724–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compion, Sara. 2017. The Joiners: Active Voluntary Association Membership in Twenty African Countries. Voluntas 28: 1270–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, Anabel. 2013. Is Civil Society in the Southern Cone of Latin America at a Crossroad? Development in Practice 23: 678–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, Daniel W., Van Evans, and Ram A. Cnaan. 2013. Charitable Practices of Latter-Day Saints. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 44: 146–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, Daniel, Ram A. Cnaan, and Van Evans. 2014. Motivating Mormons. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 25: 131–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Jingyun, and Anthony Spires. 2018. Advocacy in an Authoritarian State: How Grassroots Environmental NGOs Influence Local Governments in China. In The China Journal. vol. 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, John-Michael. 2019. Comparing the Prevalence and Organizational Distinctiveness of Faith-Based and Secular Development NGOs in Canada. Voluntas 30: 1380–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denbel, Jima Dilbo. 2013. Transitional Justice in the Context of Ethiopia. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences 10: 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, Rose Anne, and Wenzhuo Zhao. 2017. Philanthropic Behaviour of Quebecers. Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, Ian D. 2013. Witchcraft Accusations amongst the Muslim Amacinga Yawo of Malawi and Modes of Dealing with Them. Australasian Review of African Studies 34: 103. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, Kathryn, Khuat Thu Hong, Bridget Haire, and Heather Worth. 2020. Historic and Contemporary Influences on HIV Advocacy in Vietnam. Voluntas. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djupe, Paul A. 2014. The Effects of Descriptive Associational Leadership on Civic Engagement: The Case of Clergy and Gender in Protestant Denominations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53: 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolacis, Valters, and Dace Dolace. 2018. The Contribution of Ecclesia Communities to the Development of Community Work: Working Religious Capital. Tiltai 79: 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dollhopf, Erica J. 2013. Decline and Conflict: Causes and Consequences of Leadership Transitions in Religious Congregations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 675–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollhopf, Erica J., Christopher P. Scheitle, and John D. McCarthy. 2015. Initial Results from a Survey of Two Cohorts of Religious Nonprofits. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 156–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, Robert, and Ani Sarkissian. 2017. The Roman Catholic Charismatic Movement and Civic Engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 536–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreessen, Erwin A. J. 2000. What Do We Know About the Voluntary Sector? An Overview; Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

- Drezner, Noah D., Itay Greenspan, Hagai Katz, and Galia Feit. 2016. Philanthropy in Israel 2016: Patterns of Individual Giving. The Institute for Law and Philanthropy. Tal Aviv: Tel Aviv University. [Google Scholar]

- Drydakis, Nick. 2010. Religious Affiliation and Employment Bias in the Labor Market. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 49: 477–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebaugh, Helen Rose, Janet S. Chafetz, and Paula F. Pipes. 2006. Where’s the Faith in Faith-Based Organizations? Measures and Correlates of Religiosity in Faith-Based Social Service Coalitions. Social Forces 84: 2259–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisha, Omri. 2011. Moral Ambition Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches. The Anthropology of Christianity. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson, Stephen, Vernon A. Woodley, and Anthony Paik. 2012. The Structure of Religious Environmentalism: Movement Organizations, Interorganizational Networks, and Collective Action. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 266–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, Yomna. 2018. At the Intersection of Social Entrepreneurship and Social Movements: The Case of Egypt and the Arab Spring. Voluntas 29: 819–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, Bernadene, and Peter John Morey. 2016. Faith-Based Volunteer Motivation: Exploring the Applicability of the Volunteer Functions Inventory to the Motivations and Satisfaction Levels of Volunteers in an Australian Faith-Based Organization. Voluntas 27: 1343–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Van, Daniel W. Curtis, and Ram A. Cnaan. 2013. Volunteering Among Latter-Day Saints. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 827–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Crystal A., Gregory R. Evans, and Lorin Mayo. 2017. Charitable Giving as a Luxury Good and the Philanthropic Sphere of Influence. Voluntas 28: 556–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayos Gardó, Teresa, Martina G. Gallarza Granizo, Francisco Arteaga Moreno, and Elena Floristán Imizcoz. 2014. Measuring Socio-Demographic Differences in Volunteers with a Value-Based Index: Illustration in a Mega Event. Voluntas 25: 1345–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, Roger, and Robert R. Martin. 2014. Ensuring Liberties: Understanding State Restrictions on Religious Freedoms. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53: 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, Robert M., Carlos Gervasoni, and Keely Jones Stater. 2015. Inequality and the Altruistic Life: A Study of the Priestly Vocation Rate. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 575–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Edward Orozco, and Jennifer Elena Cossyleon. 2016. ‘I Went Through It so You Don’t Have To’: Faith-Based Community Organizing for the Formerly Incarcerated. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 662–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, Alan. 2016. Changing Direction: Adapting Foreign Philanthropy to Endogenous Understandings and Practices. In Philanthropy in South Africa, Centre for Civil Society, University of KwaZulu Natal, Forthcoming. Edited by Shauna Mottiar and Mvuselelo Ngcoya. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) Press, pp. 155–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, Alan, and Kees Biekart. 2017. Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives for Sustainable Development Goals: The Importance of Interlocutors. Public Administration and Development 37: 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, Alan, and Jacob Mwathi Mati. 2019. African Gifting: Pluralising the Concept of Philanthropy. Voluntas 30: 724–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, Alan, and Susan Wilkinson-Maposa. 2013. Horizontal Philanthropy among the Poor in South Africa: Grounded Perspectives on Social Capital and Civic Association. In Giving to Help, Helping to Give: The Context and Politics of African Philanthropy. Edited by Tade Akin Aina and Bhekinkosi Moyo Dakar-Fann. Senegal: Amalion Publishing, pp. 105–30. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Richard. 2015. Why Do Balinese Make Offerings? On Religion, Teleology and Complexity. Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia 171: 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freston, Paul. 2001. Evangelicals and Politics in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freston, Paul. 2008. Evangelical Christianity and Democracy in Latin America. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Jacqui, and Penny Edgell. 2017. Distinctiveness Reconsidered: Religiosity, Structural Location, and Understandings of Racial Inequality. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuist, Todd Nicholas. 2014. The Dramatization of Beliefs, Values, and Allegiances: Ideological Performances Among Social Movement Groups and Religious Organizations. Social Movement Studies 13: 427–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuist, Todd Nicholas. 2015. Talking to God Among a Cloud of Witnesses: Collective Prayer as a Meaningful Performance. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 523–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, Brad R., and Richard L. Wood. 2017. Achieving and Leveraging Diversity through Faith-Based Organizing. In Religion and Progressive Activism. Edited by Ruth Braunstein, Todd Nicholas Fuist and Rhys H. Williams. New York: New York University Press, pp. 29–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, Brad R., and Richard L. Wood. 2018. Civil Society Organizations and the Enduring Role of Religion in Promoting Democratic Engagement. Voluntas 29: 1068–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furneaux, Craig, and Jo Barraket. 2014. Purchasing Social Good(s): A Definition and Typology of Social Procurement. Public Money & MAnagement 34: 265–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallet, Wilma. 2016. Christian Mission or an Unholy Alliance?: The Changing Role of Church-Related Organisations in Welfare-to-Work Service Delivery. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Melbourne, Melboure. [Google Scholar]

- García, Alfredo, and Joseph Blankholm. 2016. The Social Context of Organized Nonbelief: County-Level Predictors of Nonbeliever Organizations in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, Andrew M., Brian B. Drwecki, Colleen F. Moore, Katherine V. Kortenkamp, and Matthew D. Gracz. 2014. The Oneness Beliefs Scale: Connecting Spirituality with Pro-Environmental Behavior. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53: 356–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Mark M., Thomas P. Gaunt, and Carolyne Saunders. 2013. U.S. Catholic Online Giving. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA). [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Christine L., Brian W. Pence, Lynne C. Messer, Jan Ostermann, Rachel A. Whetten, Nathan M. Thielman, Karen O’Donnell, and Kathryn Whetten. 2016. Civic Engagement among Orphans and Non-Orphans in Five Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Globalization and Health 12: 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaus-Pasha, Aisha, and Muhammad Asif Iqbal. 2003. Pakistan: Defining the Nonprofit Sector. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies. Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2011/09/Pakistan_CNP_WP42_2003.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Gidron, Benjamin, and Hagai Katz. 1998. Israel: Defining the Nonprofit Sector. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies. Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2011/09/Israel_CNP_WP26_1998.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Givens, Roger J. 2012. The Study of the Relationship Between Organizational Culture and Organizational Performance in Non-Profit Religious Organizations. International Journal of Organization Theory and Behavior; Boca Raton 15: 239–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanville, Jennifer L., Matthew A. Andersson, and Pamela Paxton. 2013. Do Social Connections Create Trust? An Examination Using New Longitudinal Data. Social Forces 92: 545–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanville, Jennifer L., Pamela Paxton, and Yan Wang. 2016. Social Capital and Generosity: A Multilevel Analysis. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 45: 526–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, Ross, Phil Zuckerman, Luke Galen, David Pollack, and F. LeRon Shults. 2019. Good Without God? Connecting Religiosity, Affiliation And Pro-Sociality Using World Values Survey Data And Agent-Based Simulation. Working Paper. College Park: SocArXiv, University of Maryland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GPEI. 2018. Global Philanthropy Environment Index 2018, European ed. Indianapolis: Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. Available online: https://globalindices.iupui.edu/doc/gpei18-europe.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- GPEI. 2019. Global Philanthropy Environment Index 2018, Asia-Pacific ed. Indianapolis: Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. Available online: https://globalindices.iupui.edu/doc/regional-brief-asia-pacific.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Greenspan, Itay. 2014. How Can Bourdieu’s Theory of Capital Benefit the Understanding of Advocacy NGOs? Theoretical Framework and Empirical Illustration. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 43: 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths-Dingani, Kate. 2012. The Prosperity Gospel in Times of Austerity: Global Evangelism in Zimbabwe and the Diaspora. Anthropology Now 4: 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grim, Brian J, and Melissa E Grim. 2016. The Socio-Economic Contribution of Religion to American Society: An Empirical Analysis. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 12: 31. [Google Scholar]

- Hager, Mark A., and Eri C. Hedberg. 2016. Institutional Trust, Sector Confidence, and Charitable Giving. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 28: 164–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hameiri, Lior. 2019. Executive-Level Volunteers in Jewish Communal Organizations: Their Trust in Executive Professionals as Mediating the Relationship Between Their Motivation to Volunteer and Their Pursuit of Servant Leadership. Voluntas 30: 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Jun. 2017. Social Marketisation and Policy Influence of Third Sector Organisations: Evidence from the UK. Voluntas 28: 1209–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Ling, Swee-Sum Lam, and Joanna Zhi Hui Hioe. 2019. Grassroots Philanthropy in Singapore in the New Millennium. Philanthropy in Asia. Singapore: Asia Centre for Social Entrepreneurship and Philanthropy, National University of Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Tobias. 2012. How to Establish a Study Association: Isomorphic Pressures on New CSOs Entering a Neo-Corporative Adult Education Field in Sweden. Voluntas 23: 182–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Yvonne, Vic Murray, and Chris Cornforth. 2013. Perceptions of Board Chair Leadership Effectiveness in Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Organizations. Voluntas 24: 688–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havens, John J., and Paul G. Schervish. 2001. The Methods and Metrics of the Boston Area Diary Study. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 30: 527–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, Myriam El. 2017. Corporate Fundraising at Médecins Sans Frontières: A Review, a Strategy and a Case Study. Neuchâtel: University of Neuchatel. [Google Scholar]

- Hayford, Sarah R., and Jenny Trinitapoli. 2011. Religious Differences in Female Genital Cutting: A Case Study from Burkina Faso. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 252–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, Naomi. 2012. Pentecostalism and the Morality of Money: Prosperity, Inequality, and Religious Sociality on the Zambian Copperbelt. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 18: 123–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiphetz, Larisa, and Liane L. Young. 2019. Children’s and Adults’ Affectionate Generosity Toward Members of Different Religious Groups. American Behavioral Scientist 63: 1910–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiphetz, Larisa, Elizabeth S. Spelke, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. 2013. Patterns of Implicit and Explicit Attitudes in Children and Adults: Tests in the Domain of Religion. Journal of Experimental Psychology General 142: 864–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, Patricia Snell. 2020. Global Studies of Religiosity and Spirituality: A Systematic Review for Geographic and Topic Scopes. Religions 11: 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, Patricia Snell, David P. King, Rafia A. Khader, Amy Strohmeier, and Andrew L. Williams. 2020. Studying Religiosity and Spirituality: A Review of Macro, Micro, and Meso-Level Approaches. Religions 11: 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess. 2018. Exploring the Epistemological Challenges Underlying Civic Engagement by Religious Communities. The Good Society 26: 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Jonathan P., and Kevin R. den Dulk. 2013. Religion, Volunteering, and Educational Setting: The Effect of Youth Schooling Type on Civic Engagement. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 179–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, Virginia A. 2003. Volunteering in Global Perspective. In The Values of Volunteering: Cross-Cultural Perspectives. Edited by Paul Dekker, Loek Halman Nonprofit and Civil Society Studies. New York: Springer, pp. 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz-Rozen, Shani. 2018. Framing Philanthropy in Time of War. International Journal of Communication 12: 269–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, Hsin-Huang Michael. 1990. Emerging Social Movements and the Rise of a Demanding Civil Society in Taiwan. The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, 163–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Hsin-Huang Michael. 2011. Social Movements in Taiwan: A Typological Analysis. In East Asian Social Movements. Nonprofit and Civil Society Studies. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustinx, Lesley, Fernida Handy, Ram Cnaan, Jeffrey L. Brudney, Anne Birgitta Pessi, and Naoto Yamauchi. 2010. Social and Cultural Origins of Motivations to Volunteer: A Comparison of University Students in Six Countries. International Sociology 25: 349–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPF. 2017. Global Indices: Compartive Index of Philanthropic Freedom (IPF) Questionnaire. Indianapolis: Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. [Google Scholar]

- Irarrazaval, Ignacio. 1994. Community Organizations in Latin America. Inter-American Development Bank Series; Washington, DC: Centers for Research in Applied Economics. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/Community-Organizations-in-Latin-America.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Irarrazaval, Ignacio, Eileen M. H. Hairel, S. Wojciech Sokolowski, and Lester M Salamon. 2006. Chile: Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project National Report. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies. Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2011/08/Chile_CNP_NationalReport_Espanol_2006.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Jansons, Emily, and Femida Handy. 2016. The Geographies and Scales of Philanthropy: Philanthropy in India. In The Routledge Companion to Philanthropy. Edited by Tobias Jung, Susan D. Phillips and Jenny Harrow. Philadelphia: Routledge, pp. 119–23. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Kathryn A., Adam B. Cohen, and Morris A. Okun. 2013. Intrinsic Religiosity and Volunteering During Emerging Adulthood: A Comparison of Mormons with Catholics and Non-Catholic Christians. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 842–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Kathryn A., Joshua N. Hook, Don E. Davis, Daryl R. Van Tongeren, Steven J. Sandage, and Sarah A. Crabtree. 2016. Moral Foundation Priorities Reflect U.S. Christians’ Individual Differences in Religiosity. Personality and Individual Differences 100: 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, Joseph B. 2013. Religion and Volunteering Over the Adult Life Course. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 733–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Jong Hyun. 2012. Islamophobia? Religion, Contact with Muslims, and the Respect for Islam. Review of Religious Research 54: 113–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Chul Hee, Femida Handy, Lesley Hustinx, Ram Cnaan, Jeffrey L. Brudney, Debbie Haski-Leventhal, Kirsten Holmes, Lucas C. P. M. Meijs, Anne Birgitta Pessi, Bhagyashree Ranade, and et al. 2011. What Gives? Cross-National Differences in Students’ Giving Behavior. Social Science Journal 48: 283–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Hagai, and Itay Greenspan. 2015. Giving in Israel: From Old Religious Traditions to an Emerging Culture of Philanthropy. In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Philanthropy. Edited by Pamala Wiepking and Femida Handy. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 316–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Sabith. 2016. New Styles of Community Building and Philanthropy by Arab-American Muslims. Voluntas 27: 941–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khvorostianov, Natalia, and Larissa Remennick. 2017. ‘By Helping Others, We Helped Ourselves:’ Volunteering and Social Integration of Ex-Soviet Immigrants in Israel. Voluntas 28: 335–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılınç, Ramazan, and Carolyn M. Warner. 2015. Micro-Foundations of Religion and Public Goods Provision: Belief, Belonging, and Giving in Catholicism and Islam. Politics and Religion 8: 718–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Inchoon, and Changsoon Hwang. 2002. Defining the Nonprofit Sector: South Korea. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies. Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2011/09/Korea_CNP_WP41_2002.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Kim, Jungsook, and Heon Joo Jung. 2020. An Empirical Analysis on Determinants of Aid Allocation by South Korean Civil Society Organizations. Voluntas. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, David P. 2019. God’s Internationalists: World Vision and the Age of Evangelical Humanitarianism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinney, Nancy T. 2015. Structure, Context, and Ideological Dissonance in Transnational Religious Networks. Voluntas 26: 382–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korovkin, Tanya. 2001. Reinventing the Communal Tradition: Indigenous Peoples, Civil Society, and Democratization in Andean Ecuador. Latin American Research Review 36: 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Krindatch, Alexei D. 2015. Exploring Orthodox Generosity: Giving in U.S. Orthodox Parishes. South Bound Brook: Assembly of Canonical Orthodox Bishops of the USA. [Google Scholar]

- Krull, Laura M. 2020. Liberal Churches and Social Justice Movements: Analyzing the Limits of Inclusivity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 59: 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, Muthusami, and Joanna Pappas. 2012. Managing Voluntourism. In The Volunteer Management Handbook: Strategies for Success. Indianapolis: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Kushnirovich, Nonna, and D. Ribovsky. 2012. Determinants of Volunteering and Charitable Giving. Economic Herald of the Donbas 4: 205–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kumi, Emmanuel. 2019. Aid Reduction and NGDOs’ Quest for Sustainability in Ghana: Can Philanthropic Institutions Serve as Alternative Resource Mobilisation Routes? Voluntas 30: 1332–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Swee-Sum, Gabriel Henry Jacob, and David Jeremiah Seah. 2011. Framing the Roots of Philanthropy. Asia Centre for Social Entrepreneurship & Philanthropy (ACSEP) Basic Research Working Paper. Singapore: National University of Singapore, Report Number 2. Available online: https://bschool.nus.edu.sg/acsep/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/10/BRWP2.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Lam, Swee-Sum. 2014. Framing the Roots of Philanthropy. ACSEP Research Working Paper Series No. 14/03; Singapore: Asia Centre for Social Entrepreneurship & Philanthropy, National University of Singapore. Available online: https://bschool.nus.edu.sg/Portals/0/images/ACSEP/Publications/ACSEP%20Working%20Paper%2014_03a.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2019).

- Landres, J. Shawn, Jim Gerstein, and Steven M. Cohen. 2013. Dataset: The National Study of American Jewish Giving (NSAJG). New York: Berman Jewish Databank. Available online: https://www.jewishdatabank.org/databank/search-results/study/731 (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Langdon, Lauren. 2017. Universities with Philanthropy Centres Across the World. Tableau Public. Available online: https://public.tableau.com/profile/laurenlangdon#!/vizhome/Universitieswithphilanthropycentres/Dashboard1 (accessed on 27 June 2020).

- Lasker, Judith N. 2016. Global Health Volunteering; Understanding Organizational Goals. Voluntas 27: 574–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launiala, Annika, and Marja-Liisa Honkasalo. 2010. Malaria, Danger, and Risk Perceptions among the Yao in Rural Malawi. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 24: 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, Michael D. 2013. Shared Destiny, Shared Responsibility: Growing Binational Philanthropy for a Stronger U.S.-Mexico Partnership. Washington, DC: U.S.-Mexico Foundation. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/8810810/Shared_Destiny_Shared_Responsibility_Growing_Binational_Philanthropy_for_a_Stronger_U.S.-Mexico_Partnership_2013_ (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Layton, Michael D., and Alejandro Moreno. 2014. Philanthropy and Social Capital in Mexico. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 19: 209–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazăr, Adela Răzvana, and Adrian Hatos. 2019. Religiosity and Generosity of Youth. The Results of a Survey with 8th Grade Students from Bihor County (Romania). Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala 11: 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledvinová, Jana. 1997. Money, Money Everywhere: Grassroots Fundraising. Building Sustainable Non-Profit Organizations. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Institute for Policy Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Cheng-Pang. 2018. Making Taiwan Relevant to Sociology: Turning Contingencies into Puzzles. Paper presented at 3rd World Congress of Taiwan Studies (WCTS), Taiwan, China, September 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Cheng-Pang, and Ling Han. 2016a. Faith-Based Organizations and Transnational Voluntarism in China: A Case Study on Malaysia Airline MH370 Incident. Voluntas 27: 2353–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Cheng-Pang, and Ling Han. 2016b. Mothers and Moral Activists: Two Models of Women’s Social Engagement in Contemporary Taiwanese Buddhism. Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 19: 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, Robert, David Horton Smith, Cornelia Giesing, Maria José León, Debbie Haski-Leventhal, Benjamin J. Lough, Jacob Mwathi Mati, Sabine Strassburg, and Paul Hockenos. 2011. State of the World’s Volunteerism Report, 2011: Universal Values for Global Well-Being. Bonn: United Nations Volunteers. Available online: https://researchers.mq.edu.au/en/publications/state-of-the-worlds-volunteerism-report-2011-universal-values-for (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Lewis, Valerie A., Carol Ann MacGregor, and Robert D. Putnam. 2013. Religion, Networks, and Neighborliness: The Impact of Religious Social Networks on Civic Engagement. Social Science Research 42: 331–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Chaeyoon, and Carol Ann MacGregor. 2012. Religion and Volunteering in Context Disentangling the Contextual Effects of Religion on Voluntary Behavior. American Sociological Review 77: 747–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, D. Michael, and Robert Wuthnow. 2010. Financing Faith: Religion and Strategic Philanthropy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 49: 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Jiahuan. 2017. Does Population Heterogeneity Really Matter to Nonprofit Sector Size? Revisiting Weisbrod’s Demand Heterogeneity Hypothesis. Voluntas. (published online). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, Trina. 2011. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination. Evaluation & Research in Education 24: 303–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luria, Gil, Ram A. Cnaan, and Amnon Boehm. 2017. Religious Attendance and Volunteering: Testing National Culture as a Boundary Condition. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 577–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussier, Danielle N. 2019. Mosques, Churches, and Civic Skill Opportunities in Indonesia. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 58: 415–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luwaile, Amos. 2015. Faith and Health: An Appraisal of the Work of the African Religious Health Assets (ARHAP) among Faith Communities in Zambia. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal. Available online: https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10413/12248/Luwaile_Amos_2015.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- Maki, Alexander, Joseph A. Vitriol, Patrick C. Dwyer, John S. Kim, and Mark Snyder. 2017. The Helping Orientations Inventory: Measuring Propensities to Provide Autonomy and Dependency Help. European Journal of Social Psychology 47: 677–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelker, Lauren. 2020. What Makes Us Give? A Consideration of Factors Influencing Philanthropy in Canada. Work in Progress. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/4851902/What_Makes_Us_Give_A_Consideration_of_Factors_Influencing_Philanthropy_in_Canada (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Manuel, Paul Christopher, and Miguel Glatzer. 2019. Faith-Based Organizations and Social Welfare: Associational Life and Religion in Contemporary Western Europe. Religion, Politics, and Policy. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, Katherine. 2013. Global Institutions of Religion: Ancient Movers, Modern Shakers. Philadelphia: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mati, Jacob Mwathi. 2017. Emergence of Inter-Identity Alliances in Struggles for Transformation of the Kenyan Constitution. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 9: 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mati, Jacob Mwathi, Fengshi WU, Bob Edwards, Sherine N. El Taraboulsi, and David H. Smith. 2016. Social Movements and Activist-Protest Volunteering. In The Palgrave Handbook of Volunteering, Civic Participation, and Nonprofit Associations. Edited by David Horton Smith, Robert A. Stebbins and Jurgen Grotz. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 516–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manglos-Weber, Nicolette D. 2017. Identity, Inequality, and Legitimacy: Religious Differences in Primary School Completion in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 302–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, Yoshiho, Naoto Yamauchi, and Naoko Okuyama. 2010. What Determines the Size of the Nonprofit Sector?: A Cross-Country Analysis of the Government Failure Theory. Voluntas 21: 180–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, Sally. 2018. Confronting the Colonial Library: Teaching Political Studies Amidst Calls for a Decolonised Curriculum. Politikon 45: 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrl, Damon. 2018. The Judicialization of Religious Freedom: An Institutionalist Approach. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57: 514–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, Jennifer. 2013. Sources of Social Support: Examining Congregational Involvement, Private Devotional Activities, and Congregational Context. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 698–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, Jennifer M. 2017. ‘Go and Do Likewise’: Investigating Whether Involvement in Congregationally Sponsored Community Service Activities Predicts Prosocial Behavior. Review of Religious Research 59: 341–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendry-Smith, Emily. 2016. ‘Baba Has Come to Civilize Us’: Developmental Idealism and Framing the Strict Demands of the Brahma Kumaris. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullin, Caitlin, and Chris Skelcher. 2018. The Impact of Societal-Level Institutional Logics on Hybridity: Evidence from Nonprofit Organizations in England and France. Voluntas 29: 911–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, Thomas. 2015. Development, Witchcraft and Malawi’s Elite. Australasian Review of African Studies 36: 74. [Google Scholar]

- Mejova, Yelena, Venkata Rama Kiran Garimella, Ingmar Weber, and Michael C. Dougal. 2014. Giving Is Caring: Understanding Donation Behavior through Email. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing—CSCW ’14. Baltimore: ACM Press, pp. 1297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Katherine, Eileen Barker, Helen Rose Ebaugh, and Mark Juergensmeyer. 2011. Religion in Global Perspective: SSSR Presidential Panel. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 240–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgbako, Chi Adanna, and Katherine Glenn. 2011. Witchcraft Accusations and Human Rights: Case Studies from Malawi. George Washington International Law Review 43: 389. [Google Scholar]

- Minton, Elizabeth A., Lynn R. Kahle, Tan Soo Jiuan, and Siok Kuan Tambyah. 2016. Addressing Criticisms of Global Religion Research: A Consumption-Based Exploration of Status and Materialism, Sustainability, and Volunteering Behavior. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 365–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogahed, Dalia, Faiqa Mahmood, David King, Rafia Khader, and Shariq Siddiqui. 2019. American Muslim Philanthropy: A Data-Driven Comparative Prifole. Indianapolis: Lake Institute on Faith & Giving, Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, David, Larissa Shamseer, Mike Clarke, Davina Ghersi, Alessandro Liberati, Mark Petticrew, Paul Shekelle, Lesley A. Stewart, and PRISMA-P Group. 2015. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Systematic Reviews 4: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottiar, Shauna, and Mvuselelo Ngcoya. 2016. Indigenous Philanthropy: Challenging Western Preconceptions. In The Routledge Companion to Philanthropy. Edited by Tobias Jung, Susan D. Phillips and Jenny Harrow. Philadelphia: Routledge, pp. 151–61. [Google Scholar]

- Moulin-Stożek MSc, Daniel, and Alfonso Osorio. 2018. Relationships between Religion, Risk Behaviors and Prosociality among Secondary School Students in Peru and El Salvador. Journal of Moral Education 47: 466–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, Joanne M., A. John Sinclair, and Harry Spaling. 2012. Working for God and Sustainability: The Activities of Faith-Based Organizations in Kenya. Voluntas 23: 959–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, Bhekinkosi. 2010. Philanthropy in Africa: Functions, Status, Challenges and Opportunities. In Global Philanthropy. New York: MF Publishing, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, Bhekinkosi. 2011a. The Bellagio Initiative: The Future of Philanthropy and Development in the Pursuit of Human Wellbeing; Bellagio Initiative. Dakar: TrustAfrica. Available online: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/3718/Bellagio-Moyo.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Moyo, Bhekinkosi. 2011b. Transformative Innovations in African Philanthropy. In The Bellagio Initiative: The Future of Philanthropy and Development in the Pursuit of Human Wellbeing. New York: Institute of Development Studies, Resource Alliance, Rockefeller Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, Bhekinkosi. 2013. Trends, Innovations and Partnerships for Development in African Philanthropy. In Giving to Help, Helping to Give: The Context and Politics of African Philanthropy. Edited by Tade Akin Aina and Bhekinkosi Moyo. Dakar-Fann: Amalion Publishing, pp. 37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, Bhekinkosi, and Katiana Ramsamy. 2014. African Philanthropy, Pan-Africanism, and Africa’s Development. Development in Practice 24: 656–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundey, Peter, David P King, and Brad R Fulton. 2019. The Economic Practices of US Congregations: A Review of Current Research and Future Opportunities. Social Compass 66: 400–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Bryant. 2011. Walking with the Poor: Principles and Practices of Transformational Development, Revised ed. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Natal, Alejandro. 2018. Civil Society and Political Representation in Mexico. In Civil Society and Political Representation in Latin America. New York: Springer, pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Katherine M., Achim Schlüter, and Colin Vance. 2018. Distributional Preferences and Donation Behavior among Marine Resource Users in Wakatobi, Indonesia. Ocean & Coastal Management 162: 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumayr, Michaela, and Femida Handy. 2019. Charitable Giving: What Influences Donors’ Choice Among Different Causes? Voluntas 30: 783–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhina, Tamara G., and Aigerim R. Ibrayeva. 2013. Explaining the Role of Culture and Traditions in Functioning of Civil Society Organizations in Kazakhstan. Voluntas 24: 335–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Ann W., Robert Joseph Taylor, and Linda M. Chatters. 2016. Church-Based Social Support Among Caribbean Blacks in the United States. Review of Religious Research 58: 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noetel, Michael, Peter Slattery, Alexander K Saeri, Joannie Lee, Thomas Houlden, Neil Farr, Romy Gelber, Jake Stone, Lee Huuskes, Shane Timmons, and et al. 2020. How Do We Get People to Donate More to Charity? An Overview of Reviews. Charlottesville: PsyArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novis-Deutsch, Nurit. 2015. Identity Conflicts and Value Pluralism-What Can We Learn from Religious Psychoanalytic Therapists? Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior 45: 484–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyasulu, Timothy Kabulunga. 2020. Witchcraft Accusation and Church Discipline in Malawi. OKH Journal: Anthropological Ethnography and Analysis Through the Eyes of Christian Faith 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offutt, Stephen. 2011. The Role of Short-Term Mission Teams in the New Centers of Global Christianity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 796–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offutt, Stephen, LiErin Probasco, and Brandon Vaidyanathan. 2016. Religion, Poverty, and Development. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 207–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Aya, Yu Ishida, Takako Nakajima, and Yasuhiko Kotagiri. 2017. The State of Nonprofit Sector Research in Japan: A Literature Review. Voluntaristics Review 2: 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Aya, Yu Ishida, and Naoto Yamauchi. 2018. In Prosperity Prepare for Adversity: Use of Social Media for Nonprofit Funding in the Times of Disaster. In Innovative Perspectives on Public Administration in the Digital Age. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 42–64. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, Chitu. 2015. A Guide to Conducting a Standalone Systematic Literature Review. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okulicz-Kozaryn, Adam. 2010. Religiosity and Life Satisfaction across Nations. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 13: 155–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, Sophie, and Kristian Stokke. 2007. Political Polemics and Local Practices of Community Organizing and Neoliberal Politics in South Africa. In Contesting Neoliberalism: Urban Frontiers. Edited by Jamie Peck, Helga Leitner and Eric Sheppard. New York: Guildford Press, pp. 139–56. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier, Jill. 2010. In Search of Common Ground for Interdisciplinary Collaboration and Communication: Mapping the Cultural Politics of Religion and HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11427/12388 (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- Ottoni-Wilhelm, Mark. 2010. Giving to Organizations That Help People in Need: Differences Across Denominational Identities. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 49: 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Torró, Lluís. 2019. Meaning and Religion: Exploring Mutual Implications. Scientia et Fides 7: 25–46. Available online: https://dadun.unav.edu/handle/10171/58309 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Özer, Dr Mustafa, S Wojciech Sokolowski, Megan A Haddock, and Lester M Salamon. 2016. Turkey’s Nonprofit Sector in Comparative Perspective. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies. Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2017/01/Turkey_Comparative-Report_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, and David Moher. 2018. Updating the PRISMA Reporting Guideline for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. OSF Registries. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, Oona. 1996. Benevolent Altruism or Ordinary Reciprocity? A Response to Austins View of the Mindanao Hinterland. Human Organization 55: 241–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, Oona. 2017. Custom and Citizenship in the Philippine Uplands. In Citizenship and Democratization in Southeast Asia. Boston: Brill, pp. 155–77. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes, Oona. 2019. Preserving ‘Tradition’: The Business of Indigeneity in the Modern Philippine Context. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 50: 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, Denise Linda, and Jon Welty Peachey. 2013. A Systematic Literature Review of Servant Leadership Theory in Organizational Contexts. Journal of Business Ethics 113: 377–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawson, Ray. 2006. Evidence-Based Policy: A Realist Perspective. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, Pamela, and Jennifer L. Glanville. 2015. Is Trust Rigid or Malleable? A Laboratory Experiment. Social Psychology Quarterly 78: 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, Pamela, Nicholas E. Reith, and Jennifer L. Glanville. 2014. Volunteering and the Dimensions of Religiosity: A Cross-National Analysis. Review of Religious Research 56: 597–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pell, Christopher, Arantza Meñaca, Florence Were, Nana A. Afrah, Samuel Chatio, Lucinda Manda-Taylor, Mary J. Hamel, Abraham Hodgson, Harry Tagbor, and Linda Kalilani. 2013. Factors Affecting Antenatal Care Attendance: Results from Qualitative Studies in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. PLoS ONE 8: e53747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Samuel L. 2013. Social Capital, Race, and Personal Fundraising in Evangelical Outreach Ministries. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 159–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, Marie Juul. 2010. International Religious NGOs at the United Nations: A Study of a Group of Religious Organizations. Journal of Humanitarian Assistance 11. Available online: https://sites.tufts.edu/jha/archives/847 (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- Petersen, Marie Juul. 2012. Islamizing Aid: Transnational Muslim NGOs After 9.11. Voluntas 23: 126–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Susan, and Mark Blumberg. 2016. International Trends in Government-Nonprofit Relations: Constancy, Change, and Contradictions. In Nonprofits and Government: Collaboration and Conflict. Edited by Elizabeth T. Boris and C. Eugene Steuerle. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 313–42. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Susan, and Steven Rathgeb Smith. 2016. Public Policy for Philanthropy: Catching the Wave or Creating a Backwater. In The Routledge Companion to Philanthropy. Edited by Tobias Jung, Susan D. Phillips and Jenny Harrow. Philadelphia: Routledge, pp. 213–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pousadela, Ines M., and Anabel Cruz. 2016. The Sustainability of Latin American CSOs: Historical Patterns and New Funding Sources. Development in Practice 26: 606–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, Roshini, and Pauline Tan. 2015. Philanthropy on the Road to Nationhood in Singapore. Working Paper No. 1. Philanthropy in Asia. Singapore: Asia Centre for Social Entrepreneurship and Philanthropy (ACSEP). [Google Scholar]

- PRIA. 2000. Defining the Sector in India: Voluntary, Civil or Non-Profit. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies, Society for Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA). Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2011/09/India_PRIA_WP_1_2000.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- PRIA. 2003. India: Exploring the Nonprofit Sector in India: Some Glimpses from Maharashtra. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies, Society for Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA). Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2011/09/India_PRIA_WP_10_2003.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- PRIA. 2004. Dimensions of Giving and Volunteering in Delhi. Working Paper Number 13. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies, Society for Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA). Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2011/09/India_PRIA_WP_13_2004.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Popplewell, Rowan. 2018. Civil Society, Legitimacy and Political Space: Why Some Organisations Are More Vulnerable to Restrictions than Others in Violent and Divided Contexts. Voluntas 29: 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prouteau, Lionel, and Boguslawa Sardinha. 2015. Volunteering and Country-Level Religiosity: Evidence from the European Union. Voluntas 26: 242–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probasco, LiErin. 2016. Prayer, Patronage, and Personal Agency in Nicaraguan Accounts of Receiving International Aid. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 233–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proeschold-Bell, Rae Jean, Nneka Jebose Molokwu, Corey L. M. Keyes, Malik Muhammad Sohail, David E. Eagle, Heather E. Parnell, Warren A. Kinghorn, Cyrilla Amanya, Vanroth Vann, Ira Madan, and et al. 2019. Caring and Thriving: An International Qualitative Study of Caregivers of Orphaned and Vulnerable Children and Strategies to Sustain Positive Mental Health. Children and Youth Services Review 98: 143–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Robert D., and David E. Campbell. 2010. American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert D., Thomas Sander, and David E. Campbell. 2011. Dataset: Faith Matters Survey. Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). Available online: http://www.thearda.com/Archive/Files/Descriptions/FTHMAT11.asp (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Radovanović, Bojana. 2019a. Altruism in Behavioural, Motivational and Evolutionary Sense. Filozofija I Društvo 30: 122–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, Bojana. 2019b. Rational Choice Theory and Charitable Giving. Socioloski Pregled 53: 445–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, Bojana. 2019c. Volunteering and Helping in Serbia: Main Characteristics. Sociologija 61: 133–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, Jean-Pierre, and Sarah Pitcher. 2015. Religion and Revolutionary We-Ness: Religious Discourse, Speech Acts, and Collective Identity in Prerevolutionary Nicaragua. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, Amy, and Stephen Offutt. 2013. Global Poverty and Evangelical Action. In The New Evangelical Social Engagement. Edited by Brian Steensland and Philip Goff. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 242–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribberink, Egbert, Peter Achterberg, and Dick Houtman. 2017. Secular Tolerance? Anti-Muslim Sentiment in Western Europe. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 259–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridge, Natasha, and Susan Kippels. 2016. What Is the Status of State-Funded Philanthropy in the United Arab Emirates? Policy Paper. Ras Al-Khaimah: Al Gasimi Foundation for Policy Research, Report Number 15. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Nathaniel. 2016. To Be Cared For: The Power of Conversion and Foreignness of Belonging in an Indian Slum. The Anthropology of Christianity. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roodman, David, and Scott Standley. 2006. Tax Policies to Promote Private Charitable Giving in DAC Countries. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. [Google Scholar]

- Roszak, Piotr. 2020. Mute Sacrum. Faith and Its Relation to Heritage on Camino de Santiago. Religions 11: 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, Rebecca. 2011. Faith-Based Social Services: Saving the Body or the Soul? A Research Note. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 201–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamon, Lester M., and Wojciech Sokolowski. 2001. Volunteering in Cross-National Perspective: Evidence from 24 Countries. Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies. Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2011/09/CNP_WP40_2001.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Salamon, Lester M, Helmut K. Anheier, Regina List, Stefan Toepler, and S. Wojciech Sokolowski. 2004. Global Civil Society: Dimensions of Non-Profit Sector, V2. Bloomfield: Kumarian Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Salamon, Lester M., Stephanie L. Geller, and Chelsea L. Newhouse. 2012. What Do Nonprofits Stand For? Renewing the Nonprofit Value Commitment. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies. Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/12/What-Do-Nonprofits-Stand-For_JHUCCSS_12.2012.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Salamon, Lester M., S. Wojciech Sokolowski, Megan A Haddock, and Helen S. Tice. 2013. The Global Civil Society and Volunteering: Latest Findings from the Implementation of the UN Nonprofit Handbook. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies. Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2013/04/JHU_Global-Civil-Society-Volunteering_FINAL_3.2013.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Sanborn, Cynthia. 2005. Philanthropy in Latin America: Historical Traditions and Current Trends. In Philanthropy and Social Change in Latin America. Edited by Cynthia Sanborn and Felipe Portocarrero. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkissian, Ani. 2012. Religion and Civic Engagement in Muslim Countries. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 607–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpaci, Joseph L., and Ignacio Irarrazaval. 1994. Decentralizing a Centralized State: Local Government Finance in Chile Within the Latin American Context. Public Budgeting and Finance 14: 120–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schedneck, Brooke. 2015. Thailand’s International Meditation Centers: Tourism and the Global Commodification of Religious Practices. Philadelphia: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schedneck, Brooke. 2017a. Beyond the Glittering Golden Buddha Statues: Difference and Self-Transformation through Buddhist Volunteer Tourism in Thailand. Journeys 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schedneck, Brooke. 2017b. Presenting ‘Lanna’ Buddhism to Domestic and International Tourists in Chiang Mai. Asian Journal of Tourism Research 2: 101–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schedneck, Brooke. 2018a. Transcending Gender: Female Non-Buddhists’ Experiences of the Vipassanā Meditation Retrea. Religions 9: 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schedneck, Brooke. 2018b. Religious Others, Tourism, and Missionization: Buddhist ‘Monk Chats’ in Northern Thailand. Modern Asian Studies 52: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schedneck, Brooke. 2019a. Thai Buddhist Monastic Schools and Universities. Education about Asia 24: 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Schedneck, Brooke. 2019b. The Promise of the Universal: Non-Buddhists’ Accounts of Their Vipassanā Meditation Retreat Experiences. Religion 49: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiber, Laura. 2016. How Social Entrepreneurs in the Third Sector Learn from Life Experiences. Voluntas 27: 1694–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheitle, Christopher P., and John D. McCarthy. 2018. The Mobilization of Evangelical Protestants in the Nonprofit Sector: Parachurch Foundings Across U.S. Counties, 1998–2016. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57: 238–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Hillel, and Shaul Bar Nissim. 2016. The Globalization of Philanthropy: Trends and Channels of Giving. In The Routledge Companion to Philanthropy. Edited by Tobias Jung, Susan D. Phillips and Jenny Harrow. Philadelphia: Routledge, pp. 162–77. [Google Scholar]

- Schnable, Allison. 2015. Religion and Giving for International Aid: Evidence from a Survey of U.S. Church Members. Sociology of Religion 76: 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnable, Allison. 2016. What Religion Affords Grassroots NGOs: Frames, Networks, Modes of Action. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 216–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequera, Victoria. 2020. Self Report Measures for Love and Compassion Research: Helping Others. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/35673555/Self_Report_Measures_for_Love_and_Compassion_Research_Helping_Others_VOLUNTEER_FUNCTIONS_INVENTORY_VFI_Reference (accessed on 23 January 2020).

- Seymour, Jeffrey M., Michael R. Welch, Karen Monique Gregg, and Jessica Collett. 2014. Generating Trust in Congregations: Engagement, Exchange, and Social Networks. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53: 130–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shachar, Itamar Y. 2014. The White Management of ‘Volunteering’: Ethnographic Evidence from an Israeli NGO. Voluntas 25: 1417–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, Larissa, David Moher, Mike Clarke, Davina Ghersi, Alessandro Liberati, Mark Petticrew, Paul Shekelle, and Lesley A. Stewart. 2015. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and Explanation. British Medical Journal 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharak, Farzaneh Motamedi, Bagher Ghobari Bonab, and Mina Jahed. 2017. Relationship between Stress and Religious Coping and Mental Health in Mothers with Normal and Intellectually Disabled Children. International Journal of Educational and Psychological Researches 3: 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, Shane. 2019. Prayer and Charitable Behavior. Sociological Spectrum 39: 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaul Bar Nissim, Hanna. 2017. The Adaptation Process of Jewish Philanthropies to Changing Environments: The Case of the UJA-Federation of New York Since 1990. Contemporary Jewry 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaul Bar Nissim, Hanna, and Matthew A. Brookner. 2019. Ethno-Religious Philanthropy: Lessons from a Study of United States Jewish Philanthropy. Contemporary Jewry 39: 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, Eran, and David J. Roelfs. 2013. The Longevity Effects of Religious and Nonreligious Participation: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 120–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidel, Mark. 2016. Philanthropy in Asia: Evolving Public Policy. In The Routledge Companion to Philanthropy. Edited by Tobias Jung, Susan D. Phillips and Jenny Harrow. Philadelphia: Routledge, pp. 260–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sider, Ronald J., and Heidi Rolland Unruh. 2004. Typology of Religious Characteristics of Social Service and Educational Organizations and Programs. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 33: 109–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silber, Ilana F. 2011. Emotions as Regime of Justification: The Case of Civic Anger. European Journal of Social Theory 14: 301–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silber, Ilana F. 2012. The Angry Gift: A Neglected Facet of Philanthropy. Current Sociology 60: 320–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silber, Ilana F. 2016. The Cultural Worth of ‘Economies of Worth’: French Pragmatic Sociology from a Cultural Sociological Perspective. In What Used to Be Called “the New French Pragmatic Sociology” Is Not so New Anymore. Twenty-Fur Years since Uc Boltanski and Laurent Thevenot Published Their Landmark Treatise. Edited by David Inglis and Anna-Mari Almila. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd., pp. 159–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, Jill Witmer. 2013. Unintended Consequence of the Faith-Based Initiative: Organizational Practices and Religious Identity Within Faith-Based Human Service Organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 42: 563–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, Peter, Richard Vidgen, and Patrick Finnegan. 2020. Winning Heads and Hearts? How Websites Encourage Prosocial Behaviour. Behaviour & Information Technology. first published online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilde, David, and Matthew May. 2010. The Emerging Strong Program in the Sociology of Religion. SSRC Working Papers. Brooklyn: Social Science Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Gregory Allen. 2008. Politics in the Parish: The Political Influence of Catholic Priests. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jesse M. 2013. Creating a Godless Community: The Collective Identity Work of Contemporary American Atheists. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Karen A., Kirsten Holmes, Debbie Haski-Leventhal, Ram A. Cnaan, Femida Handy, and Jeffrey L. Brudney. 2010. Motivations and Benefits of Student Volunteering: Comparing Regular, Occasional, and Non-Volunteers in Five Countries. Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research 1: 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, David H., Boguslawa Sardinha, Alisa Modavanova, Hsiang-Kai Dennis Dong, Meenaz Kassam, Young-joo Lee, and Aminata Sillah. 2017. Conducive Motivations and Psychological Influences on Volunteering. In The Palgrave Handbook of Volunteering, Civic Participation, and Nonprofit Associations. Edited by David Horton Smith, Robert A. Stebbins and Jurgen Grotz. New York: Springer, pp. 702–51. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, Mark, and Patrick C. Dwyer. 2012. Altruism and Prosocial Behavior. In Handbook of Psychology, 2nd ed. Personality and Social Psychology. Indianapolis: John Wiley & Sons Inc., vol. 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolowski, S Wojciech. 2014. Measuring Social Consequences of Non-Profit Institution Activities: A Research Note. Working Paper Number 50. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies. Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2014/02/CNP-WP50_Reaserch-Note_Sokolowski_2.2014.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Sori, Assefa Tolera. 2012a. The Synergistic Effects of Socio-Economic Factors on the Risk of HIV Infection: A Comparative Study of Two Sub-Cities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Eastern Africa Social Science Research Review 28: 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sori, Assefa Tolera. 2012b. Poverty, Sexual Experience and HIV Vulnerability Risks: Evidence from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Journal of Biosocial Science 44: 677–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southby, Kris, Jane South, and Anne-Marie Bagnall. 2019. A Rapid Review of Barriers to Volunteering for Potentially Disadvantaged Groups and Implications for Health Inequalities. Voluntas 30: 907–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spires, Anthony. 2017. China. In Routledge Handbook of Civil Society in Asia. Routledge Handbooks. Philadelphia: Routledge, pp. 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Spires, Anthony. 2018. Chinese Youth and Alternative Narratives of Volunteering. China Information 32: 203–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S. S., Rajesh Tandon, S. K. Gupta, and S. K. Dwivedi. 2003. Dimensions of Giving and Volunteering in West Bengal. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies. Available online: http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2011/09/India_PRIA_WP_7_2003.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Starks, Brian, and Christian Smith. 2012. Unleashing Catholic Generosity: Explaining the Catholic Giving Gap in the United States. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Institute for Church Life. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, Kathryn S., Patrick M. Rooney, and William Chin. 2002. Measurement of Volunteering: A Methodological Study Using Indiana as a Test Case. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 31: 484–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strichman, Nancy, Fathi Marshood, and Dror Eytan. 2018. Exploring the Adaptive Capacities of Shared Jewish–Arab Organizations in Israel. Voluntas 29: 1055–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, Shelley. 2009. The Kalamazoo Promise: A Study of Philanthropy’s Increasing Role in the American Economy and Education. International Journal of Educational Advancement 9: 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]