Taking Lacquer as a Mirror, Expressing Morality via Implements: A Study of Confucian Ritual Spirituality and the Concept of Consumption in the Ming and Qing Dynasties

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ritual System and Lacquer Art

2.2. Confucian Ritual Spirituality

2.3. Development of the Concept of Consumption

3. Research and Analysis

3.1. Confucian Ritual Spirituality and the Concept of Consumption

3.1.1. Analysis of Confucian Ritual Spirituality in the Ming and Qing Dynasties

3.1.2. Influence of Confucian Thought on Social Consumption

3.2. Ritual Expression in Lacquer Art Design in the Ming and Qing Dynasties

3.2.1. Food as the First Necessity: Style and Ornamentation of Lacquer Art Tableware in the Ming and Qing Dynasties

3.2.2. Cleanness and Solemnness: Style and Ornamentation of Lacquer Art Vessels in the Ming and Qing Dynasties

3.2.3. Ancient Charm and Elegance: Style and Ornamentation of Lacquer Art Stationery in the Ming and Qing Dynasties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baudrillard, Jean. 2017. Consumer Society. Nanjing: Nanjing University Press. [Google Scholar]

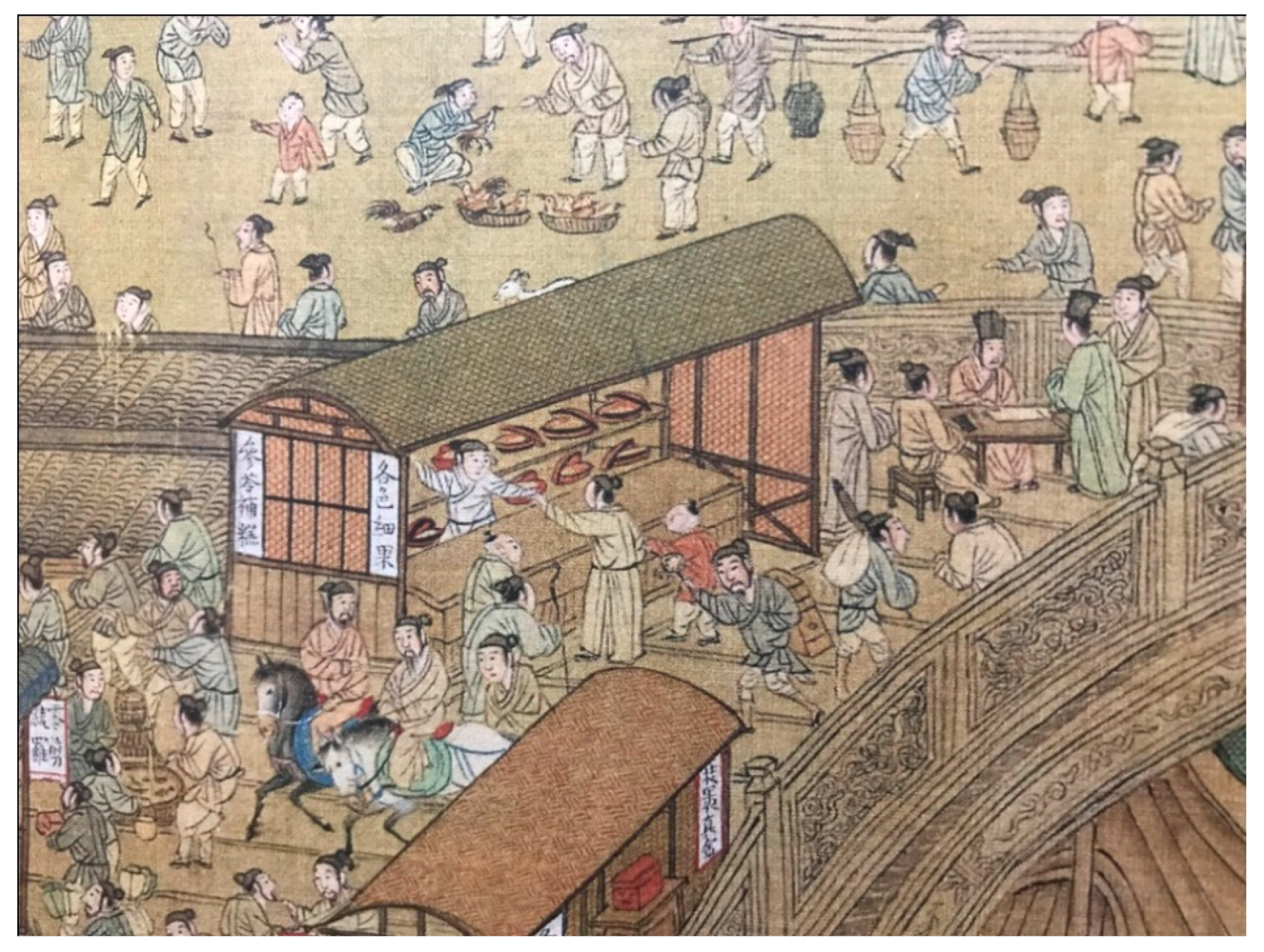

- Cao, Yanwei. 2013. Along the River During the Qingming Festival. Hefei: Anhui Art Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Jiandun. 2015. From Ritual System to Ritual Study—Exploration on Rite and Morality by Pre-Qin Confucianism. Hebei Academic Journal 2: 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Chengshuang. 2016. Three Kinds of Hierarchies in Confucian tradition: Illustrated by example of Xunzi. Journal of Anhui Normal University (Humanities and Social Sciences) 1: 112–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Dongdong. 2012. Analysis on Consumption Behavior and Consumption Ethics of Contemporary Middle Class. Commercial Times 9: 141–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Ying. 2016. Consumer Behavior in Nostalgia Consumption. China Market 22: 101–2. [Google Scholar]

- Clunas, Craig. 2016. Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Ling. 2012. Consumption Ethics and Modern Consumerism Culture Spirituality. The Northern Forum 2: 145–48. [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Board of Ci Hai. 1998. Ci Hai. Shanghai: Shanghai Lexicographic Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- E-Ertai, and Tingyu Zhang. 1987. The History of the Palace. Beijing: Beijing Ancient Books Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Lihua. 2018. Good Tools, Prerequisite for Successful Execution. Education for Chinese After-school (First Half Month) 11: 150. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Shan. 2016. The Books of History: The Book of Rites. Beijing: China Federation of Literary and Art Circles Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Xiaoyan. 2017. Influence of Confucian Thoughts on Chinese Consumer’s Consumption Psychology. Market Weekly 5: 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Shanshan. 2018. Discussion on Diverse Religious Culture in Tang Dynasty—Taking Bronze Mirror Ornamentation as Example. Journal of Literature and History 1: 83–85. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Dongmei. 2012. Construction of Sustainable Consumption Ethics in Modern Society. Journal of Changchun Education Institute 11: 70–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, Del I., and David L. Mothersbaugh. 2014. Consumer Behavior. Beijing: China Machine Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, Bingdi. 2019. An Essay on the History of Ming and Qing Dynasties. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Dunbing. 2013. Preliminary Discussion on New Change of Consumption Ethics Values and Social Transformation during Ming and Qing Dynasties. Journal of Hubei University of Economics 3: 103–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Douyong. 2011. Business Sense of Profits on Loyalty: Culture of Confucian Businessman. Jinan: Shandong Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zehou. 2001. Journey of Beauty. Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Qiang. 2010. Take History as A Mirror, Approach to Ups and Downs. Businesses Economic Review 4: 99–100. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Junfang. 2014. Study on Administration Ritual of Emperors in Han Dynasty. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Cunguang, and Chang’an Hou. 2011. Dialogue with Authority: Confucian Political Culture. Jinan: Shandong Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Zongxu. 2015. The Concise History of Modern World. History Teaching (College) 24: 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Jinyou. 2019. A Study on the Phenomenon of Lacquer Ware Reflecting Ritual During the Pre-Qin Period. Social Sciences in Shenzhen 2: 96–105. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, Yulie. 2013. Confucian Rites and Music Moralization. Spiritual Civilization 9: 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Li. 2013. Brief Discussion on Confucian Consumption Ethics Thinking and Practical Enlightenment. Journal of Jiamusi Education Institute 4: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Xiaochen. 2013. Brief Discussion on Influence of Confucian Thoughts on Lacquerware Fabrication in Han Dynasty. Literature Life: Literature Theory 9: 153. [Google Scholar]

- Min, Junrong. 2018. Hu Shang: 11 Renaissance of Ancient Lacquerware. Hangzhou: Xiling Seal Engraver’s Society Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Quanrong. 2017. Contemporary Interpretation of Marx’s Consumption Theory. Beijing: Xinhua Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Huanhuan. 2013. About Order: Female Consumption Ethics in Song Dynasty—Focusing on the Female in gentry—Civilian landlord class. Science Economy Society 3: 164–69. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Fang. 2016. Confucianism Civilization of Rites and Music. Tribune of Political Science and Law 6: 183–88. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, Michael R. 2014. Consumer Behavior. Beijing: China People’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Houyi. 2013. Discussion on Relevance between Ritual System and Grass-roots Society Control in Song Dynasty. Teachers 6: 27. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Chunchen. 2015. Pre-Qin Confucian Ritual Ethics and its Modern Values. Studies in Ethics 5: 40–44, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Veblen, Thorstein B. 2014. The Theory of the Leisure Class. Wuhan: Wuhan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xianshen. 2003. Han Feizi Variorum. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Zhenheng. 2017. Superfluous Things. Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Zhenheng. 2019. Superfluous Things. Beijing: China Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Renshu. 2012. Taste of Luxury. Taipei: Academia Sinica Linking Publishing Co., Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Yingshi. 2015. Influence of Rites-Music Tradition and Confucian Thoughts on Jade Culture in Han Dynasty. Young Writers 2: 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Zhenping. 2017. Craftl Rheology and Aesthetics of orientally-imported Lacquer. Art Observation 11: 122–23. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Wang. 2018. Exploration on Cultural Consumption Ethical System Construction under Consumption Society. Hundred Schools in Arts 3: 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Bingquan. 2019. The Beauty of the Confucian “Ritual”. Journal of Linyi University 2: 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Xun, Zi. 2015. Xunzi. Changchun: Jilin University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Zhishui. 2017. Newly Organized Xenia: Delicate Discovery from Ancient Relics (Volume Two). Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Jing, and Yifeng Wu. 2012. Discussion on the Contemporary Significance oF Pre-Qin Confucian Consumption Ethics Thinking. Journal of Hebei Youth Administrative Cadres College 2: 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Jinfeng. 2013. Living Skills and Consumption Ethics of Scholar Officials in Song Dynasty—Focusing on Family Instruction on Living in Song Dynasty. Master’s thesis, Hebei University, Baoding, China. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Feilong. 2006. The Historic Origins of Chinese Lacquer Culture. Journal of Chinese Lacquer 1: 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Feilong. 2014. Ritual of Lacquerware: Lacquer Culture in Ritual System of Pre-Qin Dynasty. Journal of Chinese Lacquer 4: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Zhong. 2008. Influence on Confucian Ritual Concept on China’s Traditional Interior Space and Furniture Form. Beauty and Times (First Half Month), 56–59. [Google Scholar]

| Level of Imperial Harems | Allocation Standard of Lacquerware |

|---|---|

| Empress Dowager 皇太后 | Two imported Japanese lacquer low tables, thirty lacquer boxes, fifteen lacquer tea trays, twenty five lacquer leather trays |

| Empress 皇后 | Two imported Japanese lacquer low tables, twenty six lacquer boxes, fifteen lacquer tea trays, twenty five lacquer leather trays |

| Imperial Noble Consort 皇貴妃 | Four lacquer boxes, two lacquer tea trays |

| Noble Consort 貴妃 | Two lacquer boxes, two lacquer tea trays |

| Consort 妃 | Two lacquer boxes, two lacquer tea trays |

| Concubine 嬪 | Two lacquer boxes, one lacquer tea tray |

| Noble Lady 貴人 | One lacquer box, one lacquer tea tray |

| First Attendant 常在 | One lacquer tea tray |

| Second Attendant 答應 | One lacquer tea tray |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, K.-K.; Li, X.-H. Taking Lacquer as a Mirror, Expressing Morality via Implements: A Study of Confucian Ritual Spirituality and the Concept of Consumption in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Religions 2020, 11, 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090447

Fan K-K, Li X-H. Taking Lacquer as a Mirror, Expressing Morality via Implements: A Study of Confucian Ritual Spirituality and the Concept of Consumption in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Religions. 2020; 11(9):447. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090447

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Kuo-Kuang, and Xue-Hui Li. 2020. "Taking Lacquer as a Mirror, Expressing Morality via Implements: A Study of Confucian Ritual Spirituality and the Concept of Consumption in the Ming and Qing Dynasties" Religions 11, no. 9: 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090447

APA StyleFan, K.-K., & Li, X.-H. (2020). Taking Lacquer as a Mirror, Expressing Morality via Implements: A Study of Confucian Ritual Spirituality and the Concept of Consumption in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Religions, 11(9), 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090447