Studying Religiosity and Spirituality: A Review of Macro, Micro, and Meso-Level Approaches

Abstract

| Table of Contents |

| 1. Introduction |

| 2. Methods |

| Publication Sources |

| 3. Results |

| 3.1. Levels of Analysis |

| 3.1.1. Macro-Level Approaches |

| Religious Demography |

| Political and Economic Geographies |

| Trans-national and Sub-national Cultures |

| Summary of Macro-Level Approaches |

| 3.1.2. Micro-Level Approaches |

| Belonging |

| Behaving |

| Believing |

| Bonding |

| Spiritual Identities and Religious Salience |

| Combinational Micro-Level Approaches |

| Summary of Micro-Level Approaches |

| 3.1.3. Meso-Level Approaches |

| Religiosity and Social Networks |

| Religiosity and Occupations |

| Religiosity and Organizations |

| i. Denominations |

| ii. Congregations |

| Faith-Based Organizations |

| Summary of Meso-Level Approaches |

| 3.1.4. Need for Multi-Level Approaches |

| 3.2. Beyond Western-Centrism |

| 3.2.1. Africa |

| 3.2.2. Asia |

| 3.2.3. Latin America |

| 3.2.4. Summary of Beyond-Western Scholarship |

| 4. Discussion |

| 4.1. Strengths and Limitations |

| 4.2. Future Studies |

| 4.3. Conclusions |

| References |

1. Introduction

2. Method

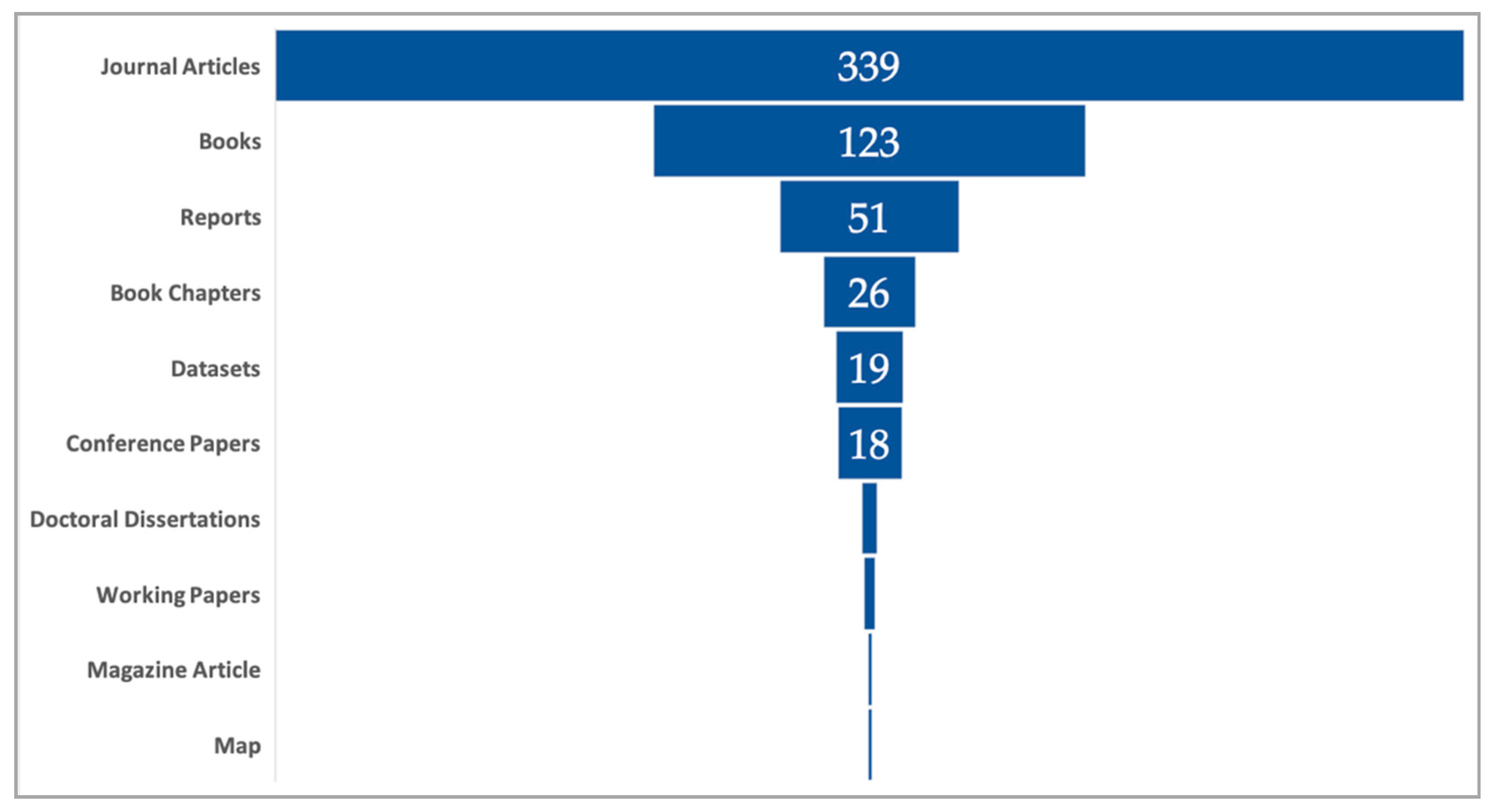

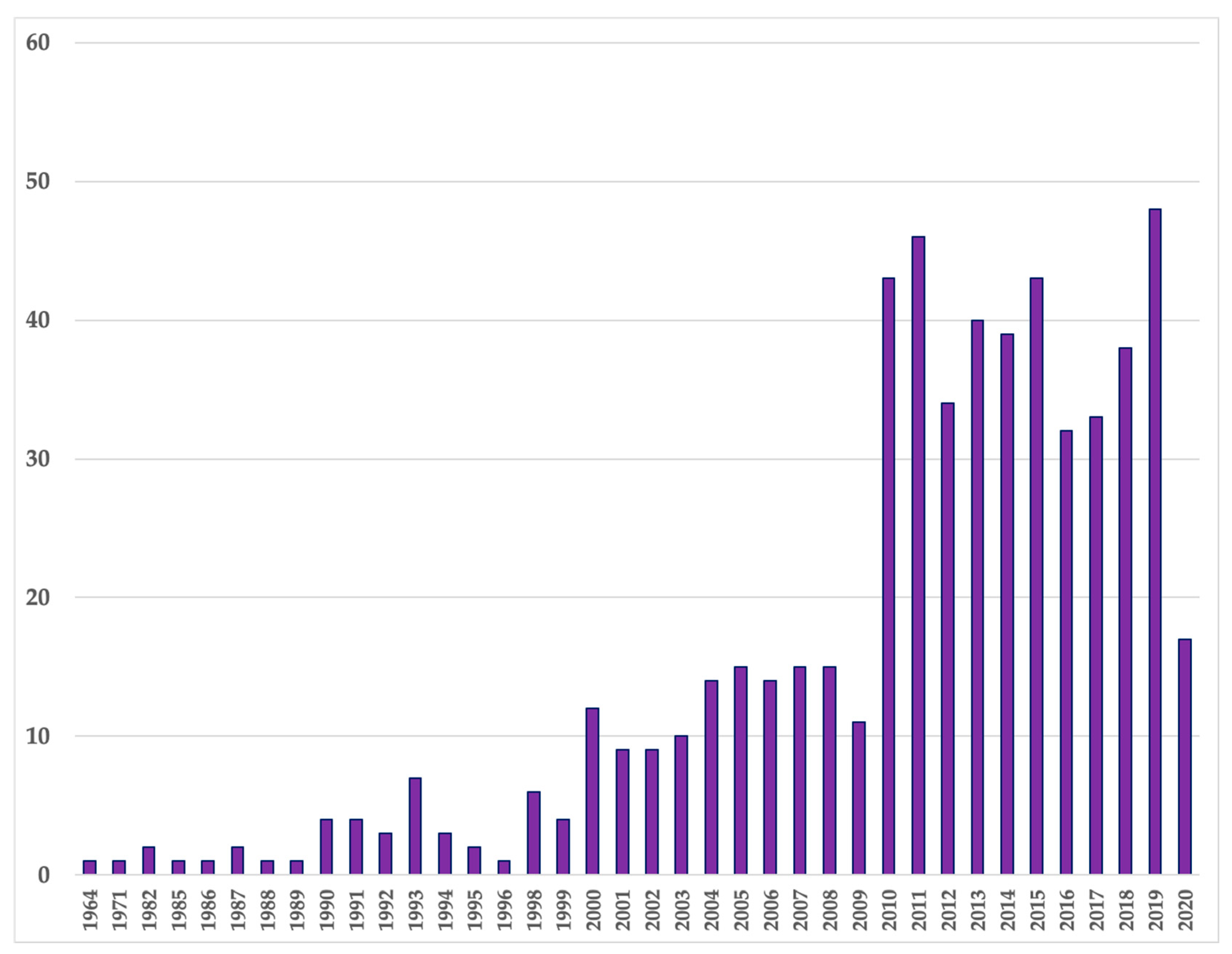

Publication Sources

3. Results

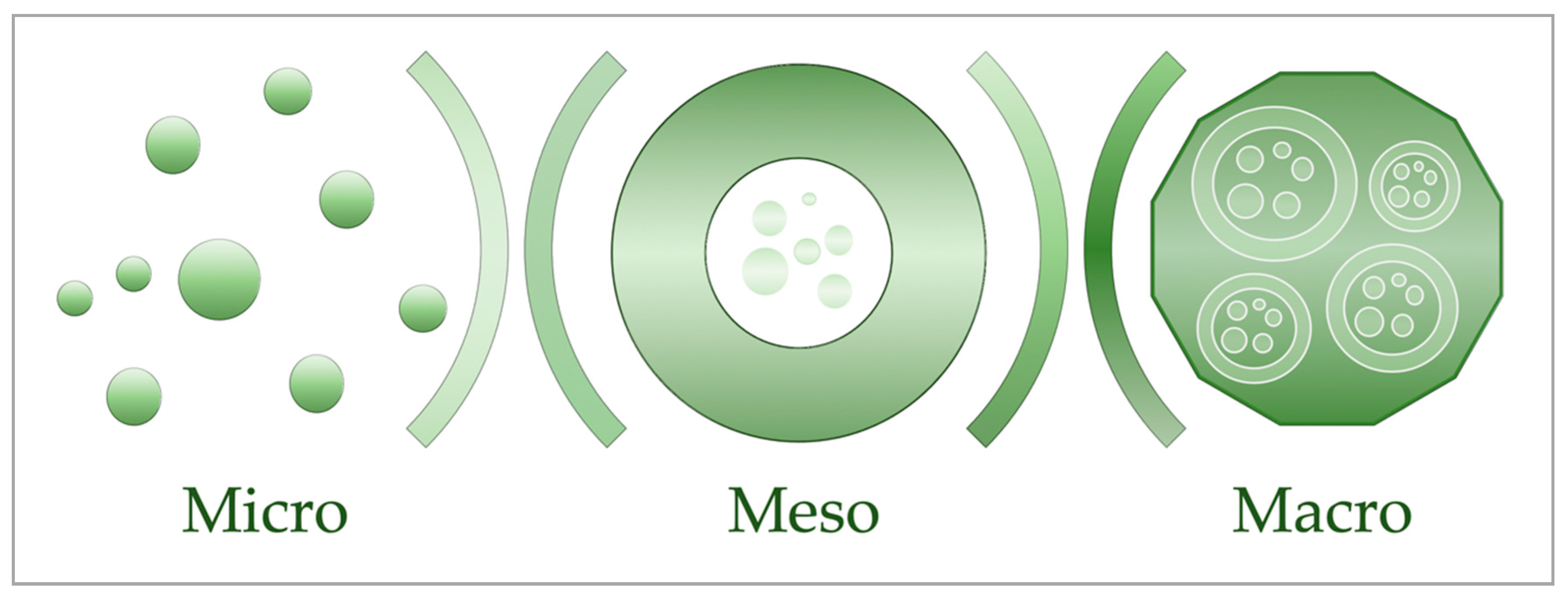

3.1. Levels of Analysis

3.1.1. Macro-Level Approaches

Religious Demography

Political and Economic Geographies

Trans-National and Sub-National Cultures

Summary of Macro-Level Approaches

3.1.2. Micro-Level Approaches

Belonging

Behaving

Believing

Bonding

Spiritual Identities and Religious Salience

Combinational Micro-Level Approaches

Summary of Micro-Level Approaches

3.1.3. Meso-Level Approaches

Religiosity and Social Networks

Religiosity and Occupations

Religious Organizations

- National Congregations Study (NCS): (Anderson et al. 2010; Anderson 2010; Baker 2010; Brauer 2017; Chaves 2017; Chaves and Anderson 2014; Chaves et al. 2014; Chaves and Eagle 2015; Chaves and Miller 2008; Chou 2008; Dollhopf 2013; Dougherty and Emerson 2018).

- U.S. Congregational Life Survey (US-CLS): (Dougherty and Whitehead 2011; Draper 2014; Krause et al. 2014; Martinez and Dougherty 2013; McClure 2013, 2014; McClure 2017; Mundey et al. 2019; Thomas and Olson 2010; Whitehead 2010; Woolever and Bruce 2010; Woolever et al. 2009, 2001)

- U.S. Religion Census, or the Religious Congregations and Membership Studies: (Bacon et al. 2010; Grammich et al. 2012; Olson and Perl 2011).

- National Study of Congregations’ Economic Practices (NSCEP): (newly created in 2019, publications thus far: Fulton 2020; Mundey et al. 2019).

Faith-Based Organizations

Summary of Meso-Level Approaches

3.1.4. Need for Multi-Level Approaches

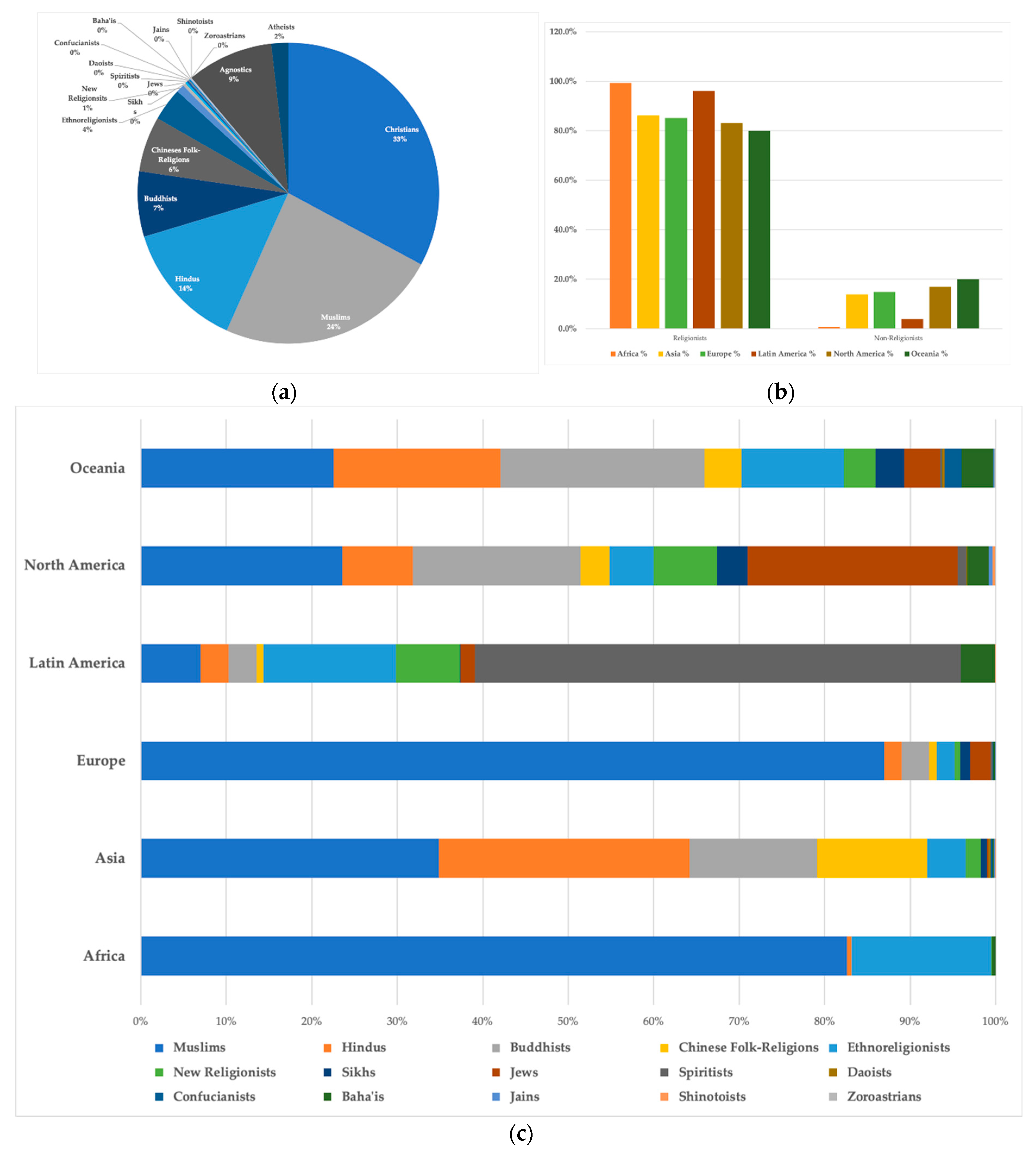

3.2. Beyond Western-Centrism

On one hand, the study of global religion is the study of religion in its global contexts, and involves the study of religious diasporas, the global spread of religious ideas, and the emerging spiritual and moral sensibilities of globalized, multicultural societies (Juergensmeyer 2005). But on the other hand, the global study of religion can affect all dimensions of religious and ideological studies—it involves taking a perceptual stance that is relevant to every aspect of the study of religion, whether the subject matter is local or far away, historical or contemporary, textual or social. The global perceptual stance is one that attempts to see all religious phenomena as part of a global drama, and to understand it through many eyes, from multiple frames of reference.

3.2.1. Africa

3.2.2. Asia

3.2.3. Latin America

3.2.4. Summary of Beyond-Western Scholarship

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Studies

4.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Existing Measures by Level

Appendix A.1. Macro-Level Measures

Appendix A.2. Micro-Level Measures

- Sectarian Protestant (e.g., Baptists, Seventh Day Adventists, and Jehovah’s Witnesses)

- Moderate Protestants (e.g., Lutherans, Methodists, nondenominational)

- Liberal Protestants (e.g., Episcopalians, Presbyterians)

- Catholics

- Other Religions

- Mormon

- No Identification

- Religious Disaffiliation Reasons (Thiessen and Wilkins-Laflamme 2017)

- Parents allowed children to decide whether to continue their affiliation with a religious tradition

- Had intellectual disagreements over core issues in religious tradition

- Developed doubts about religious tradition

- Friends left the religious tradition

- Life transitions that disrupted participation (e.g., changed jobs, got divorced, left to attend a university)

- Lost a parent or grandparent who was the main influence on the family’s religious tradition

- Religious Reorientation Reasons (Bakker and Paris 2013)

- Deepened religious conviction

- Resumed religious affiliation

- Renewed spiritual interests

- More than once a week

- Once a week

- Once or twice a month

- A few times a year

- Seldom or never

- Prayer FrequencyAside from religious services, how often do you pray?

- Several times a day

- Once a day

- A few times a week

- Once a week

- A few times a month

- Seldom

- Never

- Prayer Experiences (e.g., Ozorak 2003, p. 289)

- I feel very close to God when I pray.

- Most of my prayers are for God to solve problems for me.

- Confessing my sins to God helps me live a better life.

- I often ask God to strengthen me so that I may help others.

- When I pray, I feel secure.

- I often pray on behalf of other people.

- When God has answered my prayers, I always give thanks.

- When I pray alone, I have a ritual that I adhere to strictly.

- Beliefs about God and Divine Activities (select any that apply: e.g., Smith and Snell 2009; Wuthnow 2010a)

- God (or Allah, Yhwh, Tzevaot, Almighty, Creator, universal energy) exists.

- God (or Allah, Yhwh, Tzevaot, Almighty, Creator, universal energy) rewards the faithful.

- God (or Allah, Yhwh, Tzevaot, Almighty, Creator, universal energy) punishes sinners.

- Certain religious texts are the word of God (or Allah, Yhwh, Tzevaot, Almighty, Creator, universal energy).

- Certain people or prophets are messengers of God (or Allah, Yhwh, Tzevaot, Almighty, Creator, energy).

- I have a warm relationship with God (or Allah, Yhwh, Tzevaot, Almighty, Creator, universal energy).

- The host, or eucharist, is an instantiation of the incarnate.

- The host, or eucharist, is a symbol in the form of bread and wine.

- Angels exist.

- Because of karma, good or bad things can return to a person based on their actions.

- People can reincarnate after death into other animals or humans.

- The universe has some control over human lives.

- The four aims of life are pleasure, prosperity, cosmic order, and liberation from rebirth.

- Nothing is fixed or permanent; change is always possible.

- The path to Enlightenment is through meditation, wisdom, and living a moral life.

- I feel peace and harmony with all of humanity.

- Positive Religious Coping Subscale (Pargament et al. 2011, p. 57):

- Looked for a stronger connection with God

- Sought God’s love and care

- Sought help from God in letting go of anger

- Tried to put plans into action together with God

- Tried to see how God might be trying to strengthen through this situation

- Asked forgiveness for sins

- Focused on religion to stop worrying about problems

- Negative Religious Coping Subscale (Pargament et al. 2011, p. 57):

- Wondered whether God had abandoned

- Felt punished by God for lack of devotion

- Wondered what I did for God to punish

- Questioned God’s love for self

- Wondered whether church had abandoned

- Decided the devil made this happen

- Questioned the power of God

- Intimacy (Manglos-Weber et al. 2016, p. 9):

- Have a close, warm relationship with God

- Ties to God are strong

- God is a close companion in life

- Consistency (Manglos-Weber et al. 2016, p. 9):

- God has always been there when needed

- God is a steady and dependable presence in life

- Can always rely on God

- Anxiety (Manglos-Weber et al. 2016, p. 9):

- Often worry about whether God is pleased with self

- Worry a lot about damaging relationship with God

- Often get anxious about how choices may affect relationship with God

- Anger (Manglos-Weber et al. 2016, p. 9):

- Often feel angry at God for letting bad things happen to self

- Often get angry with God for not taking care of self as much as would like

- Often feel angry at God for seeming to ignore pleas

- Awe of God (Krause and Hayward 2014, p. 227):

- Beauty of the world that God has made leaves breathless

- Mind-boggling to think self is a small part of the infinite university that God has made

- Astonished by how little one understands about the universe and all that is in it

- Unlimited power of God fills with amazement

- Ageless and timeless nature of God fills with awe

- Filled with wonder when thinking about the limitless wisdom of God

- Although I feel bad at first when I mess up, over time I can give myself some slack.

- I hold grudges against myself for negative things I have done.

- Learning from bad things that I have done helps me get over them.

- It is really hard for me to accept myself once I’ve messed up.

- With time I am understanding of myself for mistakes I’ve made.

- I do not stop criticizing myself for negative things I’ve felt, thought, said, or done.

- Forgiveness of Others (Heartland Forgiveness Scale: Webb et al. 2005; Thompson et al. 2005a, 2005b):

- I continue to punish a person who has done something that I think is wrong.

- With time I am understanding of others for the mistakes they have made.

- I continue to be hard on others who have hurt me.

- Although others have hurt me in the past, I have eventually been able to see them as good people.

- If others mistreat me, I continue to think badly of them.

- When someone disappoints me, I can eventually move past it.

- Forgiveness of Situation (Heartland Forgiveness Scale: Webb et al. 2005; Thompson et al. 2005a, 2005b):

- When things go wrong for reasons that cannot be controlled, I get stuck in negative thoughts about it.

- With time I can be understanding of bad circumstances in my life.

- If I am disappointed by uncontrollable circumstances in my life, I continue to think negatively about them.

- I eventually make peace with bad situations in my life.

- It is really hard for me to accept negative situations that are not anybody’s fault.

- Eventually I let go of negative thoughts about bad circumstances that are beyond anyone’s control.

- I have forgiven those who hurt me. (1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = often, 4 = always) (Jang et al. 2018)

- Is forgiving dependent on something else happening first? (Tarusarira 2020, e.g., pre-condition: truth-telling)

- I am grateful to God for all He has done for me.

- I am grateful to God for all He has done for my family members and close friends.

- Extremely important

- Very

- Fairly

- Somewhat

- Not very

- Not important at all

- Group Identities (Political Attitudes and Identities Survey: Curtis 2013, p. 157):

- Europe

- The European Union

- The United Kingdom

- Your region

- Your town or village

- Your current or previous occupation

- Your race or ethnic background

- Your gender

- Your age group

- Your religion

- Your preferred political party, group, movement

- Your family or marital status (husband/wife, mother/father, son/daughter, grandparent, etc.)

- Your social class

- Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy scale (FACIT) (Bredle et al. 2011)

- I feel peaceful

- I have a reason for living

- My life has been productive

- I have trouble feeling peace of mind

- I feel a sense of purpose in my life

- I am able to reach down deep into myself for comfort

- I feel a sense of harmony within myself

- My life lacks meaning and purpose

- I find comfort in my faith or spiritual beliefs

- I find strength in my faith or spiritual beliefs

- My illness has strengthened my faith or spiritual beliefs

- I know that whatever happens with my illness, things will be okay

- Spirituality Referent: 13 (Steensland et al. 2018: “dimensions are distinct but not mutually exclusive”):

- Monotheistic deity

- Higher being

- Supernatural phenomena

- Transcendence

- The unknown

- Organized religion

- Juxtaposition to organized religion

- Nonreligious authority

- Other people

- Self

- Natural world

- The past

- The afterlife

- Spirituality Orientation: 6 (Steensland et al. 2018: “dimensions are distinct but not mutually exclusive”):

- Cognitive

- Behavioral

- Ethical

- Emotional

- Relational

- Existential

- Spirituality Classes: 7 (Steensland et al. 2018, pp. 460–64):

- 1.

- Spirituality as Organized Religion: “People who define spirituality in terms of organized religion are much less likely to consider themselves spiritual or attend church, and are more likely to be unaffiliated with a religious tradition.”—7 percent of respondents; similar to Ammerman (2013)’s “belief and belonging” view

Orientations Toward God- 2.

- Spirituality as Belief in God and Praying: “associate spirituality with belief in God with a secondary emphasis on religious practices oriented to God, usually prayer”—17 percent of respondents; high proportion Catholic

- 3.

- Spirituality as Relationship with God and Belief: “view spirituality as having a relationship with God with a secondary emphasis on belief”—17 percent of respondents; high proportion evangelical Protestant

Beliefs Outside Particular Traditions- 4.

- Spirituality as Belief in a Higher Being: “associate spirituality with belief in a higher being, sometimes using references to a higher power or supreme being and God interchangeably”—4 percent of respondents; high proportion among respondent with a moderate degree of religious affiliation

- 5.

- Spirituality as Belief in Something Beyond and Relational: belief in supernatural entities (spirits, ghosts, souls), something transcending individuals and with mysterious sources—13 percent of respondents; high proportion Jewish and unaffiliated

Relational Spirituality- 6.

- Spirituality as Holistic Connection: “most diffuse perspective on spirituality, with a primary focus on connections with and feelings toward self, nature, and other people, with a secondary focus on supernaturalism and transcendence”—6 percent of respondents; high proportion younger generations

- (Links to #3: Spirituality as Relationship with God and Belief)Ethical Action

- 7.

- Spirituality as Ethical Action: “associate spirituality with ethical action with a. prominent secondary theistic association with belief in God”—5 percent of respondents; higher proportion older generations

- Extrinsic Religiosity (Allport and Ross 1967; Gorsuch and McPherson 1989; Cohen et al. 2017, p. 11):

- Attend religious services because it helps make friends (behavior, belonging, social reward)

- Attend religious services mainly because I enjoy seeing people know (behavior, belonging, social)

- Pray mainly to gain relief or protection (behavior, religious coping)

- What religion offers most is comfort in times of trouble or sorrow (behavior, religious coping)

- Prayer is for peace and happiness (behavior, religious coping)

- Attend religious services mostly to spend time with friends (behavior, belonging, social)

- Intrinsic Religiosity (Allport and Ross 1967; Gorsuch and McPherson 1989; Cohen et al. 2017, p. 11):

- Enjoy reading about my religion (behavior, emotive and cognitive experience)

- Important to spend time in private thought and prayer (behavior, salience)

- Have often had a strong sense of God’s presence (belief, emotive experience)

- Try hard to live all life according to religious beliefs (beliefs, salience)

- Whole approach to life is based on religion (behavior, salience)

- Although I believe in religion, many other things are more important in life (belief, salience)

- Spiritual Experience Index indicators (Genia 1997, p. 345):

- Transcendent relationship to something greater than oneself

- Consistency of lifestyle, including moral behavior, with spiritual values

- Commitment without absolute certainty

- Appreciation of spiritual diversity

- Absence of egocentricity and magical thinking

- Equal emphasis on both reason and emotion

- Mature concern for others

- Tolerance and human growth strongly encouraged

- Struggles to understand evil and suffering

- A felt sense of meaning and purpose

- Ample room for both traditional beliefs and private interpretation

- Spiritual Support Subscale (Genia 1997, p. 361):

- Often feels strongly related to a power greater than one’s self

- Faith gives one’s life meaning and purpose

- Often thinks about issues concerning one’s faith

- One’s faith is an important part of one’s individual identity

- One’s relationship to God is experienced as unconditional love

- One’s faith helps to confront tragedy and suffering

- Gains spiritual strength by trusting in a higher power

- One’s faith is often a deeply emotional experience

- Makes a conscious effort to live in accordance with one’s spiritual values

- One’s faith enables experience of forgiveness when acts against moral conscience

- Sharing one’s faith with others is important for one’s spiritual growth

- One’s faith guides whole approach to life

- Spiritual Openness Subscale (Genia 1997, p. 361):

- Believes that there is only one true faith (reverse scored)

- Ideas from faith different from own may increase understanding of spiritual truth

- One should not marry someone of a different faith (reverse scored)

- Believes that the world is basically good

- Learning about different faiths is an important part of one’s spiritual development

- Feels a strong spiritual bond with all of humankind

- Never challenges the teachings of one’s faith (reverse scored)

- One’s spiritual beliefs change as encounter new ideas and experiences

- Persons of different faiths share a common spiritual bond

- Believes that the world is basically evil (reverse scored)

- Religious Organizational and Non-Organizational Activity (Koenig and Büssing 2010, p. 79):

- Frequency of church attendance or other religious meetings (behavior: ORA)

- Frequency of time spent in private religious activities, such as prayers, meditation or Bible study (behavior: NORA)

- Religious Belief or Experience (IR) (Koenig and Büssing 2010):

- In one’s life, experiences the presence of the Divine (i.e., God) (bonding, beliefs)

- One’s religious beliefs are what really lies behind whole approach to life (beliefs, salience)

- Tries hard to carry out one’s religion over into all other dealings in life (salience)

- Intellect (Huber and Huber 2012, p. 717):

- Frequency thinks about religious issues (behavior, salience)

- Interest in learning more about religious topics (salience)

- Frequency informs about religious questions via radio, television, internet, newspapers, or books (behavior)

- Ideology (Huber and Huber 2012, p. 717):

- Extent believes that God or something divine exists (belief)

- Extent believes in an afterlife—e.g., immortality of the soul, resurrection of the dead or reincarnation (belief)

- Probability that a higher power really exists (belief)

- Public Practice (Huber and Huber 2012, p. 717):

- Frequency takes part in religious services (behavior)

- Importance of taking part in religious services (salience, behavior)

- Importance of being connected to a religious community (salience, belonging)

- Private Practice (Huber and Huber 2012, p. 717):

- Frequency of prayer (behavior)

- Frequency of meditation—for interreligious scale (behavior)

- Importance of personal prayer (salience, behavior)

- Importance of meditation—for interreligious scale (salience, behavior)

- Frequency prays spontaneously when inspired by daily situations (behavior, salience)

- Frequency tries to connect to the divine spontaneously when inspired by daily situations—for interreligious scale (behavior, salience)

- Experience (Huber and Huber 2012, p. 717):

- Frequency experiences situations in which has feeling that God or something divine intervenes in one’s life (bonding, belief)

- Frequency experiences situations in which has feeling that are in one with all—for interreligious scale (bonding, belief)

- Frequency experiences situations in which has feeling that God or something divine wants to communicate or reveal something to self (bonding, belief)

- Frequency experiences situations in which has feeling that God or something divine is present (bonding, belief)

Appendix A.3. Meso-Level Measures

- Types of Faith-Based Organizations (other than Religious Congregations and Denominations):

- Umbrella organizations, such as national health care systems, accrediting agencies (e.g., Wittberg 2013)

- Inter-faith coalitions that mobilize for civic engagement (e.g., Wood and Fulton 2015; Fulton and Wood 2017)

- Private, grantmaking foundations (e.g., Lindsay and Wuthnow 2010; May and Smilde 2018);

- Social service nonprofits (e.g., Bielefeld and Cleveland 2013; Ebaugh et al. 2006; Cnaan and Boddie 2001)

- International aid NGOs (e.g., McCleary and Barro 2006; Clarke and Ware 2015; Lloyd 2007; Bielefeld and Cleveland 2013; Jeavons 2004; Sider and Unruh 2004)

- Organizational Elements Employed to Parse Faith-Based Organizations (Sider and Unruh 2004, pp. 112–15):

- Mission statement

- Founding

- External affiliation

- Controlling board selection

- Senior management selection

- Other staff selection

- Financial support and nonfinancial resources

- Organized religious practices of personnel

- Religious environment

- Religious content of program

- Form of integration of religious content with other program components

- Expected connection between religious content and desired outcomes

- Service Religiosity: 10 items (Ebaugh et al. 2006, p. 2264)

- Distribute religious materials to clients

- Help clients join congregations

- Pray with individual clients

- Pray with groups of clients

- Use religious beliefs to instruct clients

- Encourage client religious conversion

- Use religion to encourage clients

- Provide information about local congregations

- Programs require religious conversion

- Policy regarding religious discussion with clients

- Staff Religiosity: 5 items (Ebaugh et al. 2006, p. 2264)

- Pray at staff meetings

- Favor religious job candidate

- Put religious principles into action

- Demonstrate God’s love to clients

- Inspire clients’ faith via staff’s actions

- Formal Organizational Religiosity: 3 items (Ebaugh et al. 2006, p. 2264)

- Religiously explicit mission statement

- Organizational leader ordained clergy

- Sacred images in public spaces

- Social Trust: General (Dingemans and Ingen 2015, direct quotes from p. 745):

- Social trust is in the literature often measured with the same question, namely: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?”

- Sometimes, respondents can choose one of the two options, while in other surveys they have to give a score on a scale from one to ten.

- In EVS (the European Values Survey), the dichotomous answer format was used in which people could answer: (1) “Most people can be trusted,” or (2) “Can’t be too careful.”

- In line with standards in logistic analysis techniques, the “can’t be too careful” category is recoded to a score of 0, and therefore, results represent the likelihood of trusting people instead of not trusting people.

- Social Trust: Within-Congregations (Seymour et al. 2014, direct quotes from pp. 133–35):

- Our measure of within-congregation trust is a binary measure based on the original item-wording used in the PALS survey and asks respondents if they “have been able to trust completely” members of their congregation during the 12-month period prior to the interview (yes = 1, no = 0).

- Compared to some other research on the determinants of trust, our dependent measure differs somewhat in both the perceived target and expressed magnitude of trust.

- Given our focus on a type of trust that occurs within localized domains, standard questions used to measure generalized trust (e.g., “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?”) are inappropriate. Instead, the PALS item that we use asks respondents explicitly whether they trust others within their particular congregations.

- The wording for this item differs from some other ordinal measures used to represent generalized or particularized trust, although it does follow Welzel (2010) and (Wollebæk et al. 2012) in using “trust completely” as a response category to represent the highest rated level of trust.

- We believe that the wording of the dependent measure is not only acceptable for examining the trust that congregation members have for one another, but may have the advantage of being more focused and less likely to evoke ambiguous, indiscriminate, or unreflective responses from respondents.

- In future research, it would be useful to compare the specific item wording used in this measure of trust in congregants against other possible variations.

- Religious Diversity (Dingemans and Ingen 2015, direct quotes from p. 746):

- Religious diversity equals 1 minus the Herfindahl index of the different religious groups in a country, etc. (i.e., the answer categories are based on those religious groups that exist in a certain country).

- The nonreligious were included in this measure because they also represent an important and often substantial subgroup in the religious composition of a country.

- Our measure correlated highly (r = .81) with the well-known religious fractionalization measure by (Alesina et al. 2003) and by Alesina and Zhuravskaya (2011).

- Religious Leader Relationship (Seymour et al. 2014, direct quotes from p. 135):

- How close do you feel to the primary religious leader at your congregation? (coded “not at all close” = 0 to “extremely close” = 4; loading = .88)

- How often do you talk with the religious leader at your congregation, not including just saying ‘hello’ after worship services? (coded “never” = 0 to “every day” = 6; loading = .88).

- Religious Network (Seymour et al. 2014, direct quotes from p. 136):

- PALS asks respondents to nominate up to four individuals outside of their home that they “feel closest to.”

- The percentage of a respondent’s friendship network identified as a congregation member (ranging from 0 to 100 percent, mean = 26.2 percent) is a measure of relative congregational influence within a friendship network.

- It should be noted that these nominations are based solely on each respondent’s account of these friendships, and we cannot be certain whether these relationships are reciprocated.

- It seems likely, however, that a congregant’s perception of his or her network’s composition is sufficient to influence many beliefs and attitudes, including the propensity to affirm trust.

- Religious and Social Otherness (Salvatore et al. 2020, direct quotes from pp. 111–12):

- Religious and Social Groups: 3—Islam/Muslim, Immigration/Immigrant, LGBTQ+ Community

- Lines of Semiotic Force: 3 (presentation of religious and social groups in relation to mainstream society)

- Foe vs. Friend: Degree to which social institutions are trusted, have positive connotations, are viewed to be more favorable than were in the past, are reliable, are willing to take care of people’s requests

- Passivity vs. Engagement: Degree to which people are viewed to be dependent on social institutions, agencies and primary networks; degree to which can cope with an uncertain world; engagement is characterized by the sense of agency, fostered by trust in people and institutions; concerns the meaning of the world as the source of the action directed towards the subject (i.e., passivity) or, in contrast, as the goal of the subject’s investment (i.e., engagement)

- Demand for Systemic Resources vs. Community Bonds: Concerns conforming to norms and rules due to reliance on those who have power and are part of the majority for functional devices and services needed to address a challenging and uncertain world; versus a need to make life meaningful through vital participation in community bonds that undergirds a sense of agency and control over one’s life

- Semantic Structures: 2 (similarity vs. difference combined with degree of exposure to otherness)

- Normality vs. Deviance: otherness as opposed to identity; characterizes a person in said religious or social group as bad, a negative object in opposition to the valorized image of ‘people like us’

- Domestic vs. Foreign: in the case of Islam, the extent to which was characterized as an issue that needed to be addressed by local, domestic policies versus something lying outside the subjective sphere of action, viewed from an external point of observation, as foreign affairs

| Scales *Italics Indicates the Scale is Studied with but not about Religiosity or Spirituality | No. of Pubs. |

|---|---|

| Allport-Ross Intrinsic-Extrinsic Religiosity Scale (IR) | 2 |

| Awe of God (AoG) | 1 |

| Bason Quest Religious Orientations (BQRO) | 1 |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | 1 |

| Collaborative Problem-Solving Style Scale (CPSS) | 1 |

| Controlling God Scale (CGS) | 1 |

| David and Spilka Prayer Scale (DSPS) | 1 |

| Duke University Religion Index (DUREL) | 2 |

| Forgiveness of Other Scale (FOS) | 1 |

| General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) | 1 |

| Health Related Quality of Life Scale (HRQQL) | 1 |

| Heartland Forgiveness Scale (HFS) | 3 |

| Helping Orientations Inventory (HOI) | 1 |

| Implicit Association Test (IAT) | 1 |

| Loving God Scale (LGS) | 1 |

| Mature Faith Scale (MF) | 1 |

| Moral Foundations Theory/Questionnaire (MFT/MFQ) | 2 |

| Psychosocial Adjustment Adjectives (PAA) | 1 |

| Quest Scale (QS) | 2 |

| Questionnaire on Resources and Stress (QRS) | 1 |

| Religion Among Academic Scientists Study (RAAS) | 5 |

| Religious Coping Scale (RCOPE) | 2 |

| Religious Fundamentalism Scale (RF) | 1 |

| Religious Orientation Scale (ROS) | 1 |

| Religious Tradition (RELTRAD) | 2 |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) | 1 |

| Sense of Spiritual Satisfaction Scale (SSS) | 1 |

| Spiritual Experience Index (SEI) | 1 |

| Spiritual Well-Being (SWB) | 1 |

| Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-sp) | 1 |

| State Self-Esteem Scale (SSES) | 1 |

| Values, Collectivism and Individualism | 2 |

| Studies | No. of Pubs. |

|---|---|

| Brazilian Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) | 1 |

| Brazilian Social Research Survey (BSRS) | 1 |

| eDarling Online Dating Data (EDODD) | 1 |

| European Social Survey (ESS) | 1 |

| European Values Survey (EVS) | 3 |

| Faith Communities Today (FACT) | 5 |

| Faith Matters Survey (FMS) | 1 |

| General Social Survey—U.S. (GSS-US) | 5 |

| Chana Living Standards Survey (GLSS) | 1 |

| Giving in the Netherlands Panel Survey (GNPS) | 1 |

| Islamic Social Attitudes Survey (ISAS) | 1 |

| LDS Church Almanac (LCA) | 1 |

| National Congregations Study (NCS) | 9 |

| National Jewish Population Survey (NJPS) | 2 |

| National Study of American Jewish Giving (NSAJG) | 2 |

| National Study of American Religious Giving (NSARG) | 1 |

| National Study of Youth and Religion (NSYR) | 2 |

| Nondenominational Congregations Study (NDCS) | 1 |

| Organizing Religious Work (ORW) | 1 |

| Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) | 1 |

| Panel Study on American Religion and Ethnicity (PS-ARE) | 1 |

| Pew Global Religious Landscape (Pew-GRL) | 1 |

| Pew National Survey of Mormons (Pew-NSM) | 1 |

| Pew Portrait of Jewish Americans (Pew-PJA) | 1 |

| Pew Religion in Latin America Survey (Pew-RLA) | 1 |

| Political Attitudes and Identities Survey (PAIS) | 1 |

| Portrait of American Life Survey (PALS) | 3 |

| Religion and State Project (RSP) | 1 |

| SDA Annual Statistical Report (SDA-ASR) | 1 |

| Spiritual Life Study of Chinese Residents (SLSCR) | 1 |

| Synagogues 3000 Study (FACT-S) | 1 |

| U.S. Congregational Life Survey (USCLS) | 8 |

| U.S. Congregational Life Survey ELCA (USCLS-ELCA) | 1 |

| U.S. Congregational Life Survey PCUSA (USCLS-PCUSA) | 4 |

| U.S. Parish Life Study (CARA) | 1 |

| U.S. Religious Congregations and Membership Study (RCMS) | 3 |

| World Values Survey (WVS) | 4 |

| Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses | 1 |

References

- AAR. 2020. The American Academy of Religion. Available online: https://www.aarweb.org/ (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Aarfreedi, Navras J. 2019. Antisemitism in the Muslim Intellectual Discourse in South Asia. Religions 10: 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, Gabriel A., and Sarah Shah. 2015. Sectarian Affiliation and Gender Traditionalism: A Study of Sunni and Shi’a Muslims in Four Predominantly Muslim Countries. Sociology of Islam 3: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackah, William, Jualynne E. Dodson, and R. Drew Smith, eds. 2017. Religion, Culture and Spirituality in Africa and the African Diaspora. Philadelphia: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, Julio Cezar. 2018. Preaching Promise and Hope: Models of Preaching and Lived Religion in Latin America. International Journal of Practical Theology 22: 174–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adogame, Afe, and Ruth Amwe. 2019. Trumping the Devil: Engendering the Spirituality of the Marketplace within Africa and the African Diaspora. Paper presented at the Spirituality Conference 2019: Social Dimensions of Spirituality, Indianapolis, IN, USA, April 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Afifuddin, Hasan Basri, and A. K. Siti-Nabiha. 2010. Towards Good Accountability: The Role of Accounting in Islamic Religious Organisations. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology 66: 1133–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agadjanian, Victor, and Scott T. Yabiku. 2015. Religious Belonging, Religious Agency, and Women’s Autonomy in Mozambique. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 461–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, Amy L., Jeffrey P. Bjorck, Hoa B. Appel, and Bu Huang. 2013. Asian American Spirituality and Religion: Inherent Diversity, Uniqueness, and Long-Lasting Psychological Influences. In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality (Vol 1): Context, Theory, and Research. APA Handbooks in Psychology. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 581–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, Alberto, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya. 2011. Segregation and the Quality of Government in a Cross Section of Countries. American Economic Review 101: 1872–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, Alberto, Arnaud Devleeschauwer, William Easterly, Sergio Kurlat, and Romain Wacziarg. 2003. Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth 8: 155–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, Gordon W., and J. Michael Ross. 1967. Personal Religious Orientation and Prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alumkal, Antony W. 2008. Analyzing Race in Asian American Congregations. Sociology of Religion 69: 151–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2013. Spiritual but Not Religious? Beyond Binary Choices in the Study of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 258–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2014. Finding Religion in Everyday Life. Sociology of Religion 75: 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2015. Lived Religion. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Indianapolis: John Wiley & Sons Inc., pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2016. Denominations, Congregations, and Special Purpose Groups. In Handbook of Religion and Society. Edited by David Yamane. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 133–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy Tatom, Jackson W. Carroll, Carl S. Dudley, and William McKinney. 1998. Studying Congregations: A New Handbook. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Shawna L. 2010. Conflict in American Protestant Congregations. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Allan, Michael Bergunder, Andre F. Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan, eds. 2010. Studying Global Pentecostalism Theories and Methods. In The Anthropology of Christianity. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, Adam. 2015. Witchcraft, Justice, and Human Rights in Africa: Cases from Malawi. African Studies Review 58: 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astor, Avi, Marian Burchardt, and Mar Griera. 2017. The Politics of Religious Heritage: Framing Claims to Religion as Culture in Spain. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 126–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audette, Andre P., Mark Brockway, and Rodrigo Castro Cornejo. 2020. Religious Engagement, Civic Skills, and Political Participation in Latin America. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 59: 101–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, Rachel, Roger Finke, and Dale Jones. 2010. Merging the Religious Congregations and Membership Studies: A Data File for Documenting American Religious Change. Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). Available online: http://www.thearda.com/workingpapers/download/Merging%20RCMS%20Files.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Bagby, Ihsan. 2011. The American Mosque 2011: Basic Characteristics of the American Mosque, Attitudes of Mosque Leaders. Mosque Study Project. Washington: Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR). [Google Scholar]

- Bagby, Ihsan, Paul M. Perl, and Bryan T. Froehle. 2001. The Mosque in America: A National Portrait. Mosque Study Project. Washington: Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR). [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Jospeh O. 2010. Social Sources of the Spirit: Connecting Rational Choice and Interactive Ritual Theories in the Study of Religion. Sociology of Religion 71: 432–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Janel Kragt, and Jenell Paris. 2013. Bereavement and Religion Online: Stillbirth, Neonatal Loss, and Parental Religiosity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 657–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, Emily. 2017. The Social Bases of Philanthropy. Annual Review of Sociology 43: 271–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Sandra L. 2005. Black Church Culture and Community Action. Social Forces 84: 967–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Sandra L. 2009. Enter into His Gates: An Analysis of Black Church Participation Patterns. Sociological Spectrum 29: 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Sandra L. 2011. Black Church Culture: How Clergy Frame Social Problems and Solutions. Contemporary Journal of Anthropology and Sociology 1: 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Barter, Shane, and Ian Zatkin-Osburn. 2014. Shrouded: Islam, War, and Holy War in Southeast Asia. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53: 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basedau, Matthias, Georg Strüver, Johannes Vüllers, and Tim Wegenast. 2011. Do Religious Factors Impact Armed Conflict? Empirical Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Terrorism and Political Violence 23: 752–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. Daniel. 1976. Religion as Prosocial: Agent or Double Agent? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 15: 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Sedefka V., and Sara J. Gundersen. 2016. A Gospel of Prosperity? An Analysis of the Relationship between Religion and Earned Income in Ghana, the Most Religious Country in the World. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 105–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellah, Robert N. 2011. Religion in Human Evolution: From the Paleolithic to the Axial Age. Cambridge: Belknap Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, Courtney. 2011. Heaven’s Kitchen: Living Religion at God’s Love We Deliver. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, Courtney. 2013. Religion on the Edge: De-Centering and Re-Centering the Sociology of Religion. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Matthew R., and Christopher J. Einolf. 2017. Religion, Altruism, and Helping Strangers: A Multilevel Analysis of 126 Countries. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 323–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter L. 1999. The Desecularization of the World: A Global Overview. In The Desecularization of the World: Resurgent Religion and World Politics. Edited by Peter L. Berger and William B. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Company, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Peter, and Lori G. Beaman. 2007. Religion, Globalization and Culture. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielefeld, Wolfgang, and William Suhs Cleveland. 2013. Defining Faith-Based Organizations and Understanding Them through Research. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 42: 442–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borell, Klas, and Arne Gerdner. 2013. Cooperation or Isolation? Muslim Congregations in a Scandinavian Welfare State: A Nationally Representative Survey from Sweden. Review of Religious Research 55: 557–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, Erica. 2012. Disquieting Gifts: Humanitarianism in New Delhi. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers Du Toit, Nadine. 2019. Does Faith Matter? Exploring the Emerging Value and Tensions Ascribed to Faith Identity in South African Faith-Based Organisations. Hervormde Teologiese Studies 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, Beauty, James Manigault-Bryant, Mario Chandler, Darryl Dickson-Carr, John C. Hawley, Kameelah L. Martin, and Georgene Bess Montgomery. 2015. Literary Expressions of African Spirituality. Edited by Carol P. Marsh-Lockett and Elizabeth J. West. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brauer, Simon G. 2017. How Many Congregations Are There? Updating a Survey-Based Estimate. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 438–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredle, Jason M., John M. Salsman, Scott M. Debb, Benjamin J. Arnold, and David Cella. 2011. Spiritual Well-Being as a Component of Health-Related Quality of Life: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Religions 2: 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenneman, Robert. 2011. Homies and Hermanos: God and Gangs in Central America. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brenneman, Robert. 2019. Gifts, Weapons, and Values: The Language of Spirituality in 21st Century Central America. Paper presented at the Spirituality Conference 2019: Social Dimensions of Spirituality, Indianapolis, IN, USA, April 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bromley, David G. 2011. New Religions as a Specialist Field of Study. In The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Edited by Peter B. Clarke. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Candy Gunther, ed. 2011. Global Pentecostal and Charismatic Healing. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Candy Gunther. 2019. Debating Yoga and Mindfulness in Public Schools: Reforming Secular Education or Reestablishing Religion? Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Karen McCarthy, and Claudine Michel. 2011. Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn, 3rd ed. With a New Foreword by Claudine Michel edition. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brunn, Stanley D. 2015. Changing World Religion Map: Status, Literature and Challenges. In The Changing World Religion Map: Sacred Places, Identities, Practices and Politics. Edited by Stanley D. Brunn. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 3–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruntz, Courtney, and Brooke Schnedeck, eds. 2020. Buddhist Tourism in Asia. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, David T., and Luis Felipe Mantilla. 2013. God and Governance: Development, State Capacity, and the Regulation of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 328–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdette, Amy M., Terrence D. Hill, Noah S. Webb, Jason A. Ford, and Stacy H. Haynes. 2018. Religious Involvement and Substance Use among Urban Mothers. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57: 156–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadge, Wendy. 2008. De Facto Congregationalism and the Religious Organizations of Post-1965 Immigrants to the United States: A Revised Approach. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 76: 344–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cadge, Wendy, and Mary Ellen Konieczny. 2014. ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’: The Significance of Religion and Spirituality in Secular Organizations. Sociology of Religion 75: 551–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadge, Wendy, Peggy Levitt, and David Smilde. 2011. De-Centering and Re-Centering: Rethinking Concepts and Methods in the Sociological Study of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 437–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo, Jonathan E., and Stanley R. Bailey. 2015. Latino Religious Affiliation and Ethnic Identity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, José. 2011. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cavendish, James C. 2002. Church-Based Community Activism: A Comparison of Black and White Catholic Congregations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 39: 371–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwin, Jospeh. 2020. Overt and Covert Buddhism: The Two Faces of University-Based Buddhism in Beijing. Religions 11: 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, Mark. 1993a. Denominations as Dual Structures: An Organizational Analysis. Sociology of Religion 54: 147–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, Mark. 1993b. Intraorganizational Power and Internal Secularization in Protestant Denominations. American Journal of Sociology 99: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, Mark. 2004. Congregations in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, Mark. 2017. American Religion: Contemporary Trends. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, Mark, and Shawna L. Anderson. 2014. Changing American Congregations: Findings from the Third Wave of the National Congregations Study. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53: 676–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, Mark, and Allison Eagle. 2015. Religious Congregations in 21st Century America. National Congregations Study. Durham: Duke University. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, Mark, and Sharon L. Miller. 2008. Financing American Religion. Lanham: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, Mark, Shawna L. Anderson, and Alison J. Eagle. 2014. National Congregations Study: Cumulative Codebook for Waves I, II, and III (1998, 2006-07, and 2012). Durham: Duke University. Available online: http://www.soc.duke.edu/natcong/Docs/2012_NCS_Codebook_Cumulative_Sept2014.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Cherkaoui, Mohamed. 2020. Essay on Islamization: Changes in Religious Practice in Muslim Societies. Youth in a Globalizing World. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, Sing-Hang, C. Harry Hui, Esther Yuet Ying Lau, Shu-Fai Cheung, and Doris Shui Ying Mok. 2015. Does Church Size Matter? A Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Study of Chinese Congregants’ Religious Attitudes and Behaviors. Review of Religious Research 57: 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilimampunga, Charles, and George Thindwa. 2012. The Extent and Nature of Witchcraft-Based Violence against Children, Women and the Elderly in Malawi. Research Report. Lilongwe: Association of Secular Humanists and Royal Norwegian Embassy. [Google Scholar]

- Chiswick, Carmel U. 2014. Judaism in Transition: How Economic Choices Shape Religious Tradition. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, Hui-Tzu G. 2008. The Impact of Congregational Characteristics on Conflict-Related Exit. Sociology of Religion 69: 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichelli, Vincenzo, Slvie Octobre, and Viviane Riegel, eds. 2020. Aesthetic Cosmopolitanism and Global Culture. Youth in a Globalizing World. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Matthew. 2013. Good Works and God’s Work: A Case Study of Churches and Community Development in Vanuatu. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 54: 340–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Matthew, and Vicki-Anne Ware. 2015. Understanding Faith-Based Organizations: How FBOs Are Contrasted with NGOs in International Development Literature. Progress in Development Studies 15: 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnaan, Ram A., and Stephanie C. Boddie. 2001. Philadelphia Census of Congregations and Their Involvement in Social Service Delivery. Social Service Review 75: 559–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cohen, Steven M. 2004. Philanthropic Giving among American Jews: Contributions to Federation, Jewish and Non-Jewish Causes. United Jewish Communities Report Series on the National Jewish Population Survey 2000-01. New York: United Jewish Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Steven M., and Lawrence A. Hoffman. 2011. Conservative & Reform Congregations in the United States Today: Findings from the FACT-Synagogue 3000 Survey of 2010. New York: Berman Jewish Policy Archive. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Steven M., Jim Gerstein, and J. Shawn Landres. 2014. Connected to Give: Synagogues and Movements, Findings from the National Study of American Jewish Giving. Los Angeles: Jumpstart. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Adam B., Gina L. Mazza, Kathryn A. Johnson, Craig K. Enders, Carolyn M. Warner, Michael H. Pasek, and Jonathan E. Cook. 2017. Theorizing and Measuring Religiosity across Cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 43: 1724–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Randall. 2010. The Micro-Sociology of Religion: Religious Practices, Collective and Individual. State College: Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). Available online: http://www.thearda.com/rrh/papers/guidingpapers/Collins.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Conway, Brian, and Bram Spruyt. 2018. Catholic Commitment around the Globe: A 52- Country Analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57: 276–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, Katie E., David Pettinicchio, and Blaine Robbins. 2012. Religion and the Acceptability of White-Collar Crime: A Cross-National Analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 542–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Matheus. 2019. Daoism in Latin America. Journal of Daoist Studies 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranney, Stephen. 2017. Why Did God Make Me This Way? Religious Coping and Framing in the Virtuous Pedophile Community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 852–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, Katherine Amber. 2013. The Psychology of Political-Territorial Identification. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/dc99/d68ba03a5ec34aa3225ed175b9ce87763462.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Curtis, K. Amber, and Laura R. Olson. 2019. Identification with Religion: Cross-National Evidence from a Social Psychological Perspective. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 58: 790–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, Daniel W., Van Evans, and Ram A. Cnaan. 2013. Charitable Practices of Latter-Day Saints. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, Daniel, Ram A. Cnaan, and Van Evans. 2014. Motivating Mormons. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 25: 131–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antonio, William V., Michele Dillon, and Mary L. Gautier. 2013. Dataset: American Catholic Laity Poll, 2011. Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). Available online: http://www.thearda.com/Archive/Files/Descriptions/CATH2011.asp (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Davie, Grace. 2011. Thinking Sociologically about Religion: A Step Change in the Debate? ARDA Guiding Paper Series; State College: Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). Available online: http://www.thearda.com/rrh/papers/guidingpapers/Davie.asp (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- De la Torre, Renée de la, and Eloisa Martín. 2016. Religious Studies in Latin America. Annual Review of Sociology 42: 473–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelis, Reed T., John P. Bartkowski, and Xiaohe Xu. 2019. Scriptural Coping: An Empirical Test of Hermeneutic Theory. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 58: 174–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, Ian D. 2013. Witchcraft Accusations amongst the Muslim Amacinga Yawo of Malawi and Modes of Dealing with Them. Australasian Review of African Studies 34: 103. [Google Scholar]

- Dingemans, Ellen, and Erik Van Ingen. 2015. Does Religion Breed Trust? A Cross-National Study of the Effects of Religious Involvement, Religious Faith, and Religious Context on Social Trust. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 739–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djupe, Paul A. 2000. Dataset: The 2000 American Rabbi Study. Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). Available online: http://www.thearda.com/Archive/Files/Descriptions/RABBI.asp (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Djupe, Paul A., and Christopher P. Gilbert. 2000. Dataset: ELCA-Episcopal Church Study, 1999-2000. Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). Available online: http://www.thearda.com/Archive/Files/Descriptions/ELCA2000.asp (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Dollhopf, Erica J. 2013. Decline and Conflict: Causes and Consequences of Leadership Transitions in Religious Congregations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 675–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, Kevin D., and Michael O. Emerson. 2018. The Changing Complexion of American Congregations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57: 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, Kevin D., and Andrew L. Whitehead. 2011. A Place to Belong: Small Group Involvement in Religious Congregations. Sociology of Religion 72: 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, Kevin D., Mitchell J. Neubert, and Jerry Z. Park. 2019. Prosperity Beliefs and Value Orientations: Fueling or Suppressing Entrepreneurial Activity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 58: 475–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, Caitriona. 2015. Cultural and Religious Demography and Violent Islamist Groups in Africa. Political Geography 45: 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, Robert, and Ani Sarkissian. 2017. The Roman Catholic Charismatic Movement and Civic Engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 536–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, Scott. 2014. Effervescence and Solidarity in Religious Organizations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53: 229–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Uttaran. 2019. Sufi and Bhakti Performers and Followers at the Margins of the Global South: Communication Strategies to Negotiate Situated Adversities. Religions 10: 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebaugh, Helen Rose, Jennifer O’Brien, and Janet Saltzman Chafetz. 2002. The Social Ecology of Residential Patterns and Membership in Immigrant Churches. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 39: 107–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebaugh, Helen Rose, Janet S. Chafetz, and Paula F. Pipes. 2006. Where’s the Faith in Faith-Based Organizations? Measures and Correlates of Religiosity in Faith-Based Social Service Coalitions. Social Forces 84: 2259–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecklund, Elaine Howard. 2010. Science vs. Religion: What Scientists Really Think. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ecklund, Elaine Howard. 2020. Diversifying the Social Scientific Study of Religion: The Next 70 Years. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 59: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecklund, Elaine Howard, and Kristen Schultz Lee. 2011. Atheists and Agnostics Negotiate Religion and Family. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 728–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecklund, Elaine Howard, and Elizabeth Long. 2011. Scientists and Spirituality. Sociology of Religion 72: 253–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecklund, Elaine Howard, and Christopher P. Scheitle. 2017. Religion vs. Science: What Religious People Really Think. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ecklund, Elaine Howard, Jerry Z. Park, and Katherine L. Sorrell. 2011. Scientists Negotiate Boundaries Between Religion and Science. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 552–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecklund, Elaine Howard, David R. Johnson, Christopher P. Scheitle, Kirstin R. W. Matthews, and Steven W. Lewis. 2016. Religion among Scientists in International Context: A New Study of Scientists in Eight Regions. Socius 2: 2378023116664353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecklund, Elaine Howard, David R. Johnson, Brandon Vaidyanathan, Kirstin R. W. Matthews, Steven W. Lewis, Robert A. Thomson, Jr., and Di Di. 2019. Secularity and Science: What Scientists Around the World Really Think About Religion. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Korie L. 2008a. Bring Race to the Center: The Importance of Race in Racially Diverse Religious Organizations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47: 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Korie L. 2008b. The Elusive Dream: The Power of Race in Interracial Churches. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Korie L. 2019. Presidential Address: Religion and Power—A Return to the Roots of Social Scientific Scholarship. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 58: 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, Michael O., and Karen Chai Kim. 2003. Multiracial Congregations: An Analysis of Their Development and a Typology. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42: 217–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, Michael O., and Christian Smith. 2001. Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Michael O., David Sikkink, and Adele D. James. 2010. The Panel Study on American Religion and Ethnicity: Background, Methods, and Selected Results. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 49: 162–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, John L. 2010. Rethinking Islam and Secularism. ARDA Guiding Paper Series; State College: Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). Available online: http://www.thearda.com/rrh/papers/guidingpapers/esposito.asp (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Feldman, David B., Ian C. Fischer, and Robert A. Gressis. 2016. Does Religious Belief Matter for Grief and Death Anxiety? Experimental Philosophy Meets Psychology of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 531–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, Roger. 2014. Going Global: Testing Theories with International Data. Seminar on Religion and Culture in a Globalized World. Antwerp: University Centre Saint Ignatius Antwerp. Available online: http://www.thearda.com/workingpapers/download/Going%20Global%20--%20Finke.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Finke, Roger, and Christopher D. Bader, eds. 2017. Faithful Measures: New Methods in the Measurement of Religion. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finke, Roger, and Rodney Stark. 2011. The Churching of America, 1776-2005: Winners and Losers in Our Religious Economy. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finke, Roger, Christopher D. Bader, and Edward C. Polson. 2010. Faithful Measures: Developing Improved Measures of Religion. ARDA Guiding Paper Series; State College: Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). Available online: http://www.thearda.com/rrh/papers/guidingpapers/finke.asp (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Fox, Nicole. 2012. ‘God Must Have Been Sleeping’: Faith as an Obstacle and a Resource for Rwandan Genocide Survivors in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuist, Todd Nicholas. 2015. Talking to God among a Cloud of Witnesses: Collective Prayer as a Meaningful Performance. Progressive Religion 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, Brad. 2020. Religious Organizations: Crosscutting the Nonprofit Sector. In The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook, 3rd ed. Edited by Walter W. Powell and Patricia Bromley. Redwood City: Stanford University Press, pp. 579–97. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, Brad R., and Richard L. Wood. 2017. Achieving and Leveraging Diversity through Faith-Based Organizing. In Religion and Progressive Activism. Edited by R. Braunstein, T. N. Fuist and R. H. Williams. New York: New York University Press, pp. 29–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gathogo, Julius. 2019. Steve de Gruchy’s Theology and Development Model: Any Dialogue with the African Theology of Reconstruction? Stellenbosch Theological Journal 5: 307–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, Thomas P. 2017. The CARA Report: Fall 2017. U.S. Parish Life Study. Washington: Centere for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA), Georgetown University. Available online: https://cara.georgetown.edu/CARAServices/emergingmodels.html (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Gebauer, Jochen E., Constantine Sedikides, and Wiebke Neberich. 2012. Religiosity, Social Self-Esteem, and Psychological Adjustment: On the Cross-Cultural Specificity of the Psychological Benefits of Religiosity. Psychological Science 23: 158–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genia, Vicky. 1997. The Spiritual Experience Index: Revision and Reformulation. Review of Religious Research 38: 344–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giving USA. 2019. Giving USA 2019: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2018. Available online: https://givingusa.org/ (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Glanville, Jennifer L., Matthew A. Andersson, and Pamela Paxton. 2013. Do Social Connections Create Trust? An Examination Using New Longitudinal Data. Social Forces 92: 545–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanville, Jennifer L., Pamela Paxton, and Yan Wang. 2016. Social Capital and Generosity: A Multilevel Analysis. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 45: 526–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, Charles Y. 1962. On the Study of Religious Commitment. Religious Education 57: 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, Charles Y. 1973. Religion in Sociological Perspective: Essays in the Empirical Study of Religion. Belmont: Wadsworth Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- González, Alessandra L. 2011. Measuring Religiosity in a Majority Muslim Context: Gender, Religious Salience, and Religious Experience Among Kuwaiti College Students—A Research Note. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 339–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, Richard L., and Susan E. McPherson. 1989. Intrinsic/Extrinsic Measurement: I/E-Revised and Single-Item Scales. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 28: 348–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GPEI. 2018. Global Philanthropy Environment Index 2018: European Edition. Indianapolis: Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. Available online: https://globalindices.iupui.edu/doc/gpei18-europe.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- GPEI. 2019. Global Philanthropy Environment Index 2018: Asia-Pacific Edition. Indianapolis: Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. Available online: https://globalindices.iupui.edu/doc/regional-brief-asia-pacific.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Graham, Jesse, and Jonathan Haidt. 2010. Beyond Beliefs: Religions Bind Individuals Into Moral Communities. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 140–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammich, Clifford, Kirk Hadaway, Richard Houseal, Dale E. Jones, Alexei Krindatch, Richie Stanley, and Richard H. Taylor. 2012. 2010 U.S. Religion Census: Religious Congregations & Membership Study. Lenexa: Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Don, Jeff Sallaz, and Cindy Cain. 2016. Bridging Science and Religion: How Health-Care Workers as Storytellers Construct Spiritual Meanings. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 465–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, Peter, Jenny Su, and David Schak. 2012. Toward the Scientific Study of Polytheism: Beyond Forced-Choice Measures of Religious Belief. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 623–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, R. Marie, and Barbara Dianne Savage. 2008. Women and Religion in the African Diaspora Knowledge, Power, and Performance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Dingani, Kate. 2012. The Prosperity Gospel in Times of Austerity: Global Evangelism in Zimbabwe and the Diaspora. Anthropology Now 4: 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grim, Brian J., and Roger Finke. 2010. The Price of Freedom Denied: Religious Persecution and Conflict in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grim, Brian J., and Melissa E. Grim. 2016. The Socio-Economic Contribution of Religion to American Society: An Empirical Analysis. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 12: 31. [Google Scholar]

- Grim, Brian, Johnson Todd, Vergard Skirbekk, and Gina Zurlo. 2015. Yearbook of International Religious Demography 2015. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, Mathew. 2017. The Emerging Church in Transatlantic Perspective. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Güngör, Derya, Marc H. Bornstein, and Karen Phalet. 2012. Religiosity, Values, and Acculturation: A Study of Turkish, Turkish-Belgian, and Belgian Adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, Conrad. 2014. Seven Things to Consider When Measuring Religious Identity. Religion 44: 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Lloyd. 2016. Gathered: The Essential Nature of a Congregational Church. International Congregational Journal 15: 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, Ahmad Fauzi Abdul. 2013. The Aurad Muhammadiah Congregation: Modern Transnational Sufism in Southeast Asia. In Encountering Islam: The Politics of Religious Identities in Southeast Asia. Edited by Yew-Foong Hui. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies Publishing, pp. 66–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hann, Chris, and Hermann Goltz, eds. 2010. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective. The Anthropology of Christianity. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayford, Sarah R., and Jenny Trinitapoli. 2011. Religious Differences in Female Genital Cutting: A Case Study from Burkina Faso. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 252–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, Naomi. 2012. Pentecostalism and the Morality of Money: Prosperity, Inequality, and Religious Sociality on the Zambian Copperbelt. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 18: 123–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, Lynn M., Todd Matthews, and John Bartkowski. 2012. Trust in a ‘Fallen World’: The Case of Protestant Theological Conservatism. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 522–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, H. Jurgens. 2004. Studying Congregations in Africa. London: Lux Verbi. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Edwin I., Sergio Hernandez, Mario Negrete, Ramona Perez-Greek, Johnny Ramirez, Caleb Rosado, Saul Torres, and Alfonso Valenzuela. 1994. Dataset: A Study of the North American Hispanic Adventist Church-Youth Survey. Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). Available online: http://www.thearda.com/Archive/Files/Descriptions/HYOUTH.asp (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Herzog, Patricia Snell. 2020. Global Studies of Religiosity and Spirituality: A Systematic Review for Geographic and Topic Scopes. Religions 11: 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschle, Jochen. 2013. ‘Secularization of Consciousness’ or Alternative Opportunities? The Impact of Economic Growth on Religious Belief and Practice in 13 European Countries. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 410–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelm, Titus. 2018. Peter L. Berger and the Sociology of Religion: 50 Years after the Sacred Canopy. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Hoge, R. 1972. A Validated Intrinsic Religious Motivation Scale. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 11: 369–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Seung Min. 2018. Exegetical Resistance: The Bible and Protestant Critical Insiders in South Korea. Religions 9: 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Yŏng-gi, and Sŏng-hun Myŏng. 2011. Charis and Charisma: David Yonggi Cho and the Growth of Yoido Full Gospel Church. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock. [Google Scholar]

- Houle, Robert. 2018. From Burnt Bricks to Sanctification: Rethinking ‘Church’ in Colonial Southern Africa. South African Historical Journal 70: 348–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoverd, William James, Quentin D. Atkinson, and Chris G. Sibley. 2012. Group Size and the Trajectory of Religious Identification. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Anning, Xiaozhao Yousef Yang, and Weixiang Luo. 2017. Christian Identification and Self-Reported Depression: Evidence from China. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 765–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Ke-hsien. 2016. Sect-to-Church Movement in Globalization: Transforming Pentecostalism and Coastal Intermediaries in Contemporary China. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 407–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerman, Daniel M. 2011. Rethinking the Study of Religious Markets. In The Oxford Handbook of the Economics of Religion. Edited by Daniel M. Hungerman and Rachel M. McCleary. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 256–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, James Davison. 2001. Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America. New York: BasicBooks. [Google Scholar]

- Hustinx, Lesley, Fernida Handy, Ram Cnaan, Jeffrey L. Brudney, Anne Birgitta Pessi, and Naoto Yamauchi. 2010. Social and Cultural Origins of Motivations to Volunteer: A Comparison of University Students in Six Countries. International Sociology 25: 349–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannaccone, Laurence R., and Feler Bose. 2011. Funding the Faiths. In The Oxford Handbook of the Economics of Religion. Edited by Rachel M. McCleary. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismailbekova, Aksana, and Emil Nasritdinov. 2012. Transnational Religious Networks in Central Asia: Structure, Travel, and Culture of Kyrgyz Tablighi Jama’at. Transnational Social Review 2: 177–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivakhiv, Adrian. 2006. Toward a Geography of ‘Religion’: Mapping the Distribution of an Unstable Signifier. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 96: 169–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, Sriya, and Shareen Joshi. 2013. Missing Women and India’s Religious Demography. Journal of South Asian Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, Sriya, Chander Velu, and Abdul Mumit. 2014. Communication and Marketing of Services by Religious Organizations in India. Journal of Business Research 67: 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JAAR. 2020. Journal of the American Academy of Religion. OUP Academic. 2020. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/jaar/jaar (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Jain, Andrea. 2014. Selling Yoga: From Counterculture To Pop Culture. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Andrea R. 2020. Peace, Love, Yoga: The Politics of Global Spirituality. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Sung Joon, Byron R. Johnson, Joshua Hays, Michael Hallett, and Grant Duwe. 2018. Existential and Virtuous Effects of Religiosity on Mental Health and Aggressiveness among Offenders. Religions 9: 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeavons, Thomas H. 2004. Religious and Faith-Based Organizations: Do We Know One When We See One? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 33: 140–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Philip. 2014. The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jeppe Sinding, Jensen. 2013. Normative Cognition in Culture and Religion. Journal for the Cognitive Science of Religion 1: 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeung, Russell. 2005. Faithful Generations: Race and New Asian American Churches. New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Todd, and Peter F. Crossing. 2019a. The World by Religion. Journal of Religion and Demography 6: 1–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Todd, and Peter F. Crossing. 2019b. Religions by Continent. Journal of Religion and Demography 6: 215–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Todd M., and Brian J. Grim. 2013. The World’s Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography. Indianapolis: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Todd M., and Brian J. Grim. 2020. World Religion Database (WRD). Brill. Available online: https://www.worldreligiondatabase.org/ (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Johnson, Todd, and Kenneth Ross, eds. 2009. Atlas of Global Christianity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Juergensmeyer, Mark. 2005. Religion in Global Civil Society. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Jong Hyun. 2012. Islamophobia? Religion, Contact with Muslims, and the Respect for Islam. Review of Religious Research 54: 113–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, Linda Van De, and Rijk Van Dijk. 2010. Pentecostals Moving South-South: Brazilian And Ghanaian Transnationalism In Southern Africa. Religion Crossing Boundaries, 123–42. [Google Scholar]

- Karpov, Vyacheslav, Elena Lisovskaya, and David Barry. 2012. Ethnodoxy: How Popular Ideologies Fuse Religious and Ethnic Identities. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 638–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keysar, Ariela. 2017. Religious/Nonreligious Demography and Religion versus Science. In The Oxford Handbook of Secularism. Edited by Phil Zuckerman and John R. Shook. New York: Oxford University. [Google Scholar]

- Kılınç, Ramazan, and Carolyn M. Warner. 2015. Micro-Foundations of Religion and Public Goods Provision: Belief, Belonging, and Giving in Catholicism and Islam. Politics and Religion 8: 718–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Andrew Eungi. 2002. Characteristics of Religious Life in South Korea: A Sociological Survey. Review of Religious Research 43: 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, David W., and Won-il Bang. 2019. Guwonpa, WMSCOG, and Shincheonji: Three Dynamic Grassroots Groups in Contemporary Korean Christian NRM History. Religions 10: 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, David P. 2019. God’s Internationalists: World Vision and the Age of Evangelical Humanitarianism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, Lee A., and Ralph W. Hood. 1990. Intrinsic-Extrinsic Religious Orientation: The Boon or Bane of Contemporary Psychology of Religion? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 29: 442–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G., and Arndt Büssing. 2010. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): A Five-Item Measure for Use in Epidemiological Studies. Religions 1: 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczny, Mary Ellen, Loren D. Lybarger, and Kelly H. Chong. 2012. Theory as a Tool in the Social Scientific Study of Religion and Martin Riesebrodt’s The Promise of Salvation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrath, Sara H., Edward H. O’Brien, and Courtney Hsing. 2011. Changes in Dispositional Empathy in American College Students over Time: A Meta-Analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review 15: 180–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]