Abstract

This article examines two ambitious enactments of the Rama story or Rāmāyaṇa, side by side: the 17th-century painted Mewar Rāmāyaṇa and Vālmīki’s epic poem (ca. 750–500 BCE). Through a formal analysis of two crucial episodes of the tale, it highlights the creative tactics of each medium and stresses their separate aesthetic interests and autonomy. While A. K. Ramanujan’s notion of the “telling” has been immensely influential in South Asian studies to theorize the Rāmāyaṇa’s multiplicity, that concept tends to privilege speech-based embodiments. I propose, by contrast, that ekphrasis may be a more broadly applicable lens. Understanding ekphrasis as an enactment of the Rama story in any medium or in interart media, I advocate for considering poetry and painting on an equal plane as opposed to the standard view of the Mewar paintings as visual translations of linguistic phenomena. Ekphrasis, as a gateway to the maker’s creative process and preoccupations, is central to the paper’s argument, as is the role receivers play in the act of Rāmāyaṇa making.

The plurality of Rāmāyaṇa traditions is a truth universally acknowledged: We encounter not the Rāmāyaṇa but rather three hundred, three thousand, or even three hundred thousand Rāmāyaṇas.1 The truism holds for Rāmāyaṇas produced in historical periods as well as those that continue to be performed, staged, sculpted, painted, and written. Leading South Asianist scholar and poet, A. K. Ramanujan, proposed a seminal framework for understanding the relationships within this multiplicity.2 Taking literary translation as a model, Ramanujan coined the widely adopted term “telling” for Rāmāyaṇas in the world. Specifically, he suggested three types of translations—iconic, indexical, and symbolic—with varied connections, from faithful to radically reworked, to a Rāmāyaṇa that provides the scaffold for other Rāmāyaṇas within its sphere of influence.3 One such text, and one that I will consider in greater depth in this essay, is the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa. Originally sung by bards and circulating orally for as long as a millennium, it was written down in epic verse form (kāvya) around 750–500 BCE.4 Composed in Sanskrit, this earliest textual Rāmāyaṇa is attributed to the authorship of Vālmīki. Since then, the Rāma tale (or Rāmāyaṇa) has been retold in the dazzling spectrum of the subcontinent’s languages and in Southeast Asian ones besides. Now, in the visual realm, too, the Rāma story’s variety dazzles: Action-heavy sculpture animates the walls of medieval stone temples (Figure 1); lavishly illustrated manuscripts were made for early modern courts (Figure 2); and hand-painted ceremonial textiles depicting the epic’s climactic battle scene circulated between South and Southeast Asia (Figure 3). One such visual magnum opus was created for the Mewar kingdom’s Rana Jagat Singh (r. 1628–52 CE) and includes both words and pictures. In this painted Rāmāyaṇa, which I will examine alongside Vālmīki’s “first” poem (ādi kāvya), over four hundred vibrant painted pages tell the tale of Rāma and his adventures.

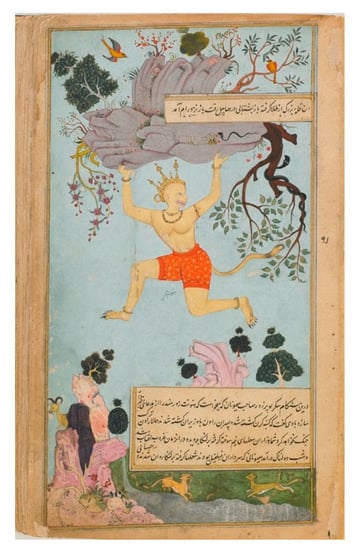

Figure 1.

Ramayana sculpture, southern elevation, Papanatha Temple, ca. 8th century CE, Pattadakal, Karnataka, India. Photo: Caleb Smith.

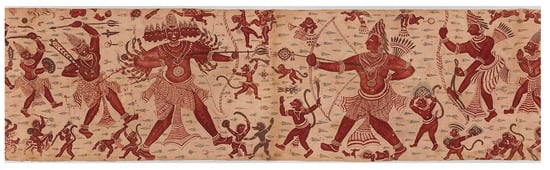

Figure 2.

Folio from the Freer Ramayana, 1597–1605, Mughal India, ink, opaque water color and gold on paper. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1907.271.173-346.

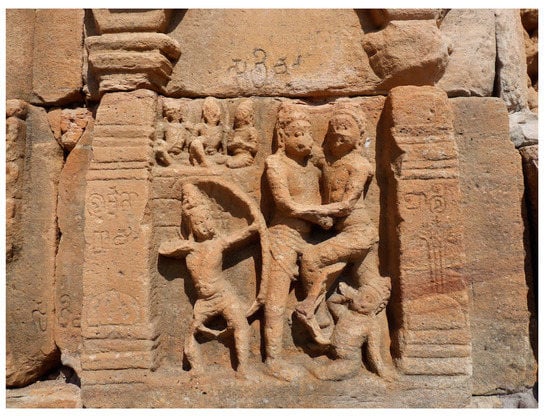

Figure 3.

The Combat of Rama and Ravana, late 18th century, India, Coromandel Coast, painted and mordant-dyed cotton. Accession Number: 2008.163, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2008.

While Ramanujan’s concept of the telling remains immensely influential in South Asian studies, I want to suggest that ekphrasis may be a more broadly applicable lens for thinking about the polyglot and polymorphous Rāmāyaṇa traditions. In its modern meaning, ekphrasis refers to a poetic description of a work of visual art that enlivens the work for the reader.5 Another way of saying it is that ekphrasis is a verse genre that speaks to, for, or about an artwork.6 Homer’s description of Achilles’ shield in the 18th book of The Iliad is considered the archetype in the western European canon.7 Yet, as Ruth Webb’s smartly observed corrective notes, works of art were of no particular importance for the ancient Greek rhetorical system that first defined and discussed ekphrasis.8 For the ancient rhetoricians, what differentiated ekphrastic texts from other texts was their vividness (energeia) and the effect they produced on the receiver; their subject matter could be anything: persons, places, events, or objects.9 Modern understandings of the term have accreted around John Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn, and are both various and enduring. Keats’ poem closes with the famous lines: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty, and that is all/Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” As the couplet suggests, ekphrastic poems may germinate from artful descriptions of a thing in the world, but their truth and their beauty reside in the insight they offer into their creator’s preoccupations. At their best ekphrastic poems are not mere linguistic transcriptions of objects, but philosophical meditations, commentaries, ruminations, interrogations, provocations, or fictions; made things that are less portraits of their subjects and more portraits of their makers. This idea of ekphrasis as a gateway to the creator’s artistic process will be central to the way I see ekphrasis in this essay. Of course, one may justifiably ask if I am taking advantage of the ambiguity of the term and its diverse and divergent modern definitions to apply it to a set of traditions with which it has no business being connected.10 But ekphrasis is a genre as flexible in its ambit and interests as the Rāmāyaṇa and can, I believe, not only withstand such a use but the application promises to enrich critical thinking on both Rāmāyaṇa traditions and ekphrasis.

In the pages that follow, I aim to do two things. First, I carry out a formal analysis of two pivotal episodes from the Vālmīki and Mewar Rāmāyaṇas to consider those books’ ekphrastic resources. In other words, I analyze how these two Rāmāyaṇas, with engagements in the literary and visual realms, respectively, vivify their subjects as well as the events and places in which those beings find themselves. Second, I ask what happens when we place these two ekphraseis up close to, and beside, one another. In particular, what role do audiences play in Rāmāyaṇa making and in the ensuing ekphrastic exchanges that transform word into image and image into word? But it is important to define at the outset that I regard ekphrasis as a creative response in any medium for which the Rāma story provides the genre, site, vehicle, or vessel. I do not elevate speech acts over enactments in other media, nor do I think of ekphrasis as just “the verbal representation of visual representation.”11 Rather, I want to suggest, building off of the originary meaning of ekphrasis as telling (phrazo) in full (ek),12 that, in the context of the constellation of Rāmāyaṇas, ekphrasis is enacting or performing the Rāma story in full, in such a way that its characters and their circumstances are brought to life for their receivers. It is worth stating that I prefer “enactment” to Ramanujan’s widely-adopted “telling,” which I believe privileges speech-based embodiments of the Rāma story as well as a one-way movement between a creator who tells and a receiver who listens and absorbs. Moreover, I am interested in juxtaposing ekphrastic instances and the discoveries that entails. On the one hand, we are in a position to discover the imaginative powers of the makers of words and pictures—we may tremble in Vālmīki’s literary jungles, say, and unravel the Mewar paintings’ skein of time—and on the other, we are able to measure poetry’s faculties against those of painting and find the situations that render each medium mute or immobile. Finally, as receivers of manifold ekphraseis, manifold Rāmāyaṇas, we are in the exhilarating position of stitching together media and leaping across their respective silences.

1. Teaching Rāmāyaṇas

This essay grew out of my interest in thinking about and teaching the Rāmāyaṇa from the point of view of a practicing poet and art historian. That is, from an aspiration to bring my two métiers to bear on a story and tradition that I, like countless others, have known, loved, and experienced from an early age. As a writer of lyric poetry, I have drawn inspiration from the Rāma story (or should I say, stories)—I have been fascinated by its female characters in particular, and am attracted to the tragic love story at its core. Indeed, the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa self-reflexively comments on its own creation and the theme of grief in separation that unifies the poem. Yes, it involves the longing of lovers for one another, like that experienced by the protagonists Rāma and Sītā during the forced parting that forms the story’s heart, but it also includes the intense losses suffered by parents, children, siblings, friends, and subjects. The text informs us that Vālmīki was so moved by the piercing cries of a krauñca bird (curlew) who had lost its mate that he found the meter (śloka) for his epic poem in the expression of the bird’s sorrow (śoka). This kind of aesthetic self-knowledge and mischievous double entendre—discovering the śloka because of śoka—are characteristic of this great poem and of Sanskrit verse more generally. Although I will return to the notion of self-reflexivity and how it relates to ekphrasis, here I want to stress that ekphrasis as a mode of writing has equipped me with the poetic tactics to rewrite the Rāmāyaṇa’s women and reimagine the theater of their feelings. The second and related point is that the tradition’s established history of such rewritings has given me the encouragement to do so.

Ekphrasis in the Rāmāyaṇa and ekphrasis as a practice that students develop in their writing were the two organizing principles of a graduate seminar I taught recently. The seminar posed a number of pedagogical challenges, however. First, how to present the complexities and attractions of this tradition and dive into it deeply in the relatively short time span of a standard academic semester? Second, and perhaps more crucially, how to do these things in a North American university setting with students not only untrained in South Asia but also with no prior knowledge of the Rāma story? For the vast majority of people in the subcontinent and in Southeast Asia, the Rāma story is an integral part of their visual and performative milieus. But this was not true for my students: The Rāma story was not in their air, nor was it embedded in everyday discourse and metaphor.

To see what I mean, consider this colorful and popular idiom in the Telugu language for describing a man’s infidelity. It goes like this: inṭilō Rāmuḍu, vīdhilō Kṛiṣṇuḍu, or “Rama at home and Krishna about town,” meaning that the man gives the impression of a loyal husband, affecting the behavior of the Rāmāyaṇa’s eponymous hero, but is actually a ladies’ man. For Telugu speakers, regardless of their social situation or religious affiliation, no more needs to be said. The signifier “Rāma” (Rāmuḍu or Rāmayya in Telugu) is enough to suggest a man faithful to one woman, who pined for her in her absence and moved mountains to win her back (of course, that is only one aspect of the story, as many of us know). Take another instance of the ubiquity of Rāmāyaṇa symbolism. A young person insecure about how she will perform in a school exam might be advised to take courage from Hanumān, Rāma’s monkey general. The son of the wind god, Hanumān, has magical powers, and is a shapeshifter (kāmarūpin) like many of the creatures in the tale: He is swift, powerful, and can grow as big as a building or shrink to the size of an ant. Despite his extraordinary powers, Hanumān is believed to lack self-confidence. He developed it only by doing, by literally leaping across the sea and moving a mountain (Figure 2). In the past few centuries, the cult of Hanumān has grown independent of Rāma so much so that monumental images of the monkey hero punctuate subcontinental landscapes and loom over subway lines, highways, and skyscrapers in contemporary India (Figure 4). Hanumān temples too have proliferated, while temples to Rāma are relatively few. I should point out that, for many South Asians, Rāma is not only the hero of the epic but also a divine figure, an incarnation of the Hindu god Viṣṇu, and therefore an embodiment of values such as righteousness, filial piety, martial power, and just governance. Philip Lutgendorf argues that Hanumān as a “second-generation god” possesses personality traits—combining ingenuity, physical strength, and intense devotion—that are particularly attractive to the needs and aspirations of middle-class South Asians.13 All of this is to say that my students had no such reference points to the Rāmāyaṇa’s tapestry of associations and meanings, although they were enthusiastic about the tale and eager to write imaginatively in response to its poetics.

Figure 4.

Image of Hanuman, Karol Bagh, Delhi, India.

A number of strategies helped organize the course and steer us through the material. First and foremost, I wanted students to grasp the broad lineaments of the Rāma narrative and come to know its dramatis personae, even if they did not yet have the kind of shorthand available to native interlocutors. Contemporary adaptations, especially film, comic book, and graphic novel forms proved useful. Both undergraduate and graduate students responded to the Rāmāyaṇa comic produced by the Amar Chitra Katha imprint in the early 1970s. For, in a mere 90 pages, the epic story unfolds in fast-paced, easily readable, polychrome frames. While I was mindful of this enactment’s partisan viewpoint and its class, color, and gender biases, such problems could eventually be explored once students had gained greater familiarity with the tradition.14 Other Rāmāyaṇas, such as the novelist R. K. Narayan’s “shortened modern prose version”, also had the advantage of introducing the whole story in brief, and importantly, in lively and literary English.15 Nina Paley’s 2009 animated film Sita Sings the Blues gripped students in ways that most other enactments did not, and excited them about the ekphrastic opportunities that this tale furnished even to non-native makers. Paley’s ekphrasis is remarkable for its incorporation of a range of art forms: literature, painting, puppetry, music, and of course animation. Moreover, its focus on the tale’s female protagonist, Sītā, and the juxtaposition of Sītā’s love story with Paley’s own autobiographical account, emphasized the Rāmāyaṇa’s adaptability to the maker’s concerns. That is, the Rāmāyaṇa was flexible enough to be made into a Sītāyana, a vehicle for a feminist voice that could challenge Vālmīki or any other patriarchal stance.

Still, the aim of the course was not to have students absorb the epic in its entirety, from beginning to end, but rather to dip in and out, inhabit some rooms and leave others for another visit. After all, this is how most people come to the Rāmāyaṇa and contend with, and appreciate, the oceanic vastness of the traditions. Their immersion in the story and apprehension of its themes builds, changes, and develops in one direction or another as they encounter more and more enactments over the course of a lifetime. This seems to be how many people experience weeks-long Rāmāyaṇa performances in northern India, known as the Rāmlīlā, and this may be how members of the court experienced painted manuscripts like the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa, which in its extant form contains a staggering 414 paintings out of an original 450.16 These were further divided across seven books (kāṇḍas) to correspond with the organization of the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa.

Possibly no painted Rāmāyaṇa manuscript comes close to the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa in terms of comprehensiveness and ambition. It is an excellent resource to teach the epic, not least for this reason, but also because much of what is extant is available in digital form even while individual kāṇḍas are dispersed across collections in London, Mumbai, Udaipur, and Baroda. Art historian J. P. Losty has dedicated his life’s work to the book and calls it “one of the most important monuments of seventeenth-century Indian art and one of the greatest of all Indian manuscripts.”17 The book was produced for Rana Jagat Singh who ruled the Rajput kingdom of Mewar from 1628 to 1652 CE, and was known for his patronage of a range of painted manuscripts in a near-quarter-century reign. While the manuscript’s accompanying Sanskrit verses were written by a single scribe, scholars trace at least three different visual styles and attribute the paintings to the ateliers of two known Mewar master painters—Sahibdin and Manohar—and an unknown painter of possible Deccan origins.18 One of the singular features of this manuscript—set of manuscripts, actually—besides its sheer magnitude is its relative intactness. Unlike the vast majority of Rāmāyaṇa manuscripts, which have been broken up into individual folios that are now dispersed in global collections, the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa volumes have remained together. Indeed, the British Library possesses four entire books of this Rāmāyaṇa, thus making this artifact uniquely valuable for study alongside other complete Rāmāyaṇas like the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa. Moreover, both text and image maintain many meaningful relationships with the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa, as we shall see.

This brings me to the other important Rāmāyaṇa that I consider here: the equally ambitious English translations of the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa, undertaken by a team of leading Sanskritists and shepherded by the husband and wife team of Robert Goldman and Sally Sutherland Goldman.19 Begun in the 1970s, the translation project took over four decades to complete and speaks to the magnitude of the task: At 24,000 verses that are organized into seven books, the text is four times the combined length of the Iliad and Odyssey. The Goldman translations stand on impeccable scholarly footing for various reasons20. They are based on the critical edition of the Valmiki text produced by the Oriental Institute of Baroda, during the 1960s and ‘70s, which edition was reconstructed from scores of manuscripts from different parts of the subcontinent, written in a variety of Indic scripts. The translators have drawn, too, on the centuries-long tradition of commentaries on the Rāmāyaṇa. In addition to these scholarly bonafides, which include scrupulous annotations and essays that shed light on the historicity of the Rāmāyaṇa and its significant themes, this is an eminently readable text. It is a joy to read and a pleasure to teach with, for the translations create their own “word-magic” that speaks to our cultural moment.21 When Rāma warns Sītā about the dangers of forest-living in Sheldon Pollock’s fine translation of Vālmīki’s second or Ayodhyā book, undergraduate students with little prior exposure to the Rāma story respond viscerally. They are moved by the sound and sense of the poetry. Like the cry of the grieving curlew (krauñca), this moment of pure lyric beauty pierces the reader who requires scarce context to feel its emotional pull. Pollock finds ways to vary the phrase “the forest is a place of pain,” so that its affective power builds with each repetition.22 He conveys the sonic effects and tropic language of the original—its exhaustive repetitions, the astonishing nature imagery, and alliterative forward movement—in language that is absolutely contemporary without sacrificing literary merit.

These two Rāmāyaṇas, then, took us through the semester’s thirteen weeks. We looked and read, read and looked, moving back and forth and interrupting any sense of a singular perspective by bringing other Rāmāyaṇas and artistic traditions into the fray.

2. Ekphrastic Exchanges

Before proceeding further, a brief recounting of the tale itself is in order, with the obvious and necessary disclaimer that mine is only one among innumerable possible accounts, and moreover reflects my slant. The epic establishes, almost at the outset, the uncanny rapport between its two central protagonists—Princess Sītā of Videha and Prince Rāma of Kosala. Theirs was a coup de foudre: They fell in love simply by catching sight of one another, a commonplace motif of ancient Indian tales. Rāma then won the right to marry Sītā through an act of strength unmatched by Sītā’s other suitors. He effortlessly lifted the bow of the god Śiva, and even broke it because of his preternatural strength. Rāma and Sītā married and relocated to Rāma’s home in the beautiful city Ayodhyā in the Kosalan kingdom. Then, on the eve of Rāma’s coronation, Daśaratha, Rāma’s father and king of Kosala, exiled Rāma for fourteen years. Kaikeyī, Daśaratha’s favorite wife, orchestrated the banishment as she wanted the throne for her own son Bharata. Rāma’s loyal brother, Lakṣmaṇa, and Sītā accompanied Rāma in his exile. A period of idyll followed for Rāma and Sītā in lovely forest hermitages, away from palace life. But Sītā’s abduction harshly disrupted these moments of mutual absorption for our heroine and hero, for Rāvaṇa, the powerful lord of Lanka, carried off Sītā. A long and lonely separation ensued, while Sītā was held against her will in the island state and Rāma searched desperately for her across the span of the Indian subcontinent. But readers and spectators know not to expect a happy denouement for the lovers with the defeat of Rāvaṇa after a strenuous siege and battle. In most accounts, Sītā was first subjected to an examination by fire to prove her purity before Rāma could publicly accept her back and before their return to Ayodhyā. Even afterwards, Rāma abandoned her because of persistent whispers against her character. Sītā retired to Vālmīki’s hermitage, where she gave birth to twin sons. Her sons learned the chronicle of Rāma from the sage, and eventually encountered Rāma and brought about a reunion of sorts. But alas, no reconciliation awaited Rāma and Sītā, as Sītā, in a final agentive act, rejected Rāma and was reabsorbed into the earth.

A majority of Rāmāyaṇa receivers know the broad outlines I have sketched: They are well-versed with a canonical version of the tale. Yet the significant point is that the canon itself is not fixed. Its forms and internal relations depend on the specific social culture and linguistic universe to which our audiences belong—Kashmiri, Telugu, Hindi, Dalit, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Jain—to name only a fraction of the possibilities and the junctures in an intricate social Venn diagram. The pleasure receivers take in the tale, their engagement with it will depend on the ways in which a specific embodiment chooses to enact the tale. As Ramanujan observes, each “telling” has its own weave, texture, and colors: “part of the aesthetic pleasure in the later poet’s telling derives from its artistic use of its predecessor’s work, from ringing changes on it.”23 The widespread use of the term “telling” that Ramanujan’s essay popularized reflects its enduring influence. Undoubtedly, he has given us a masterful paradigm for interrelating language-based Rāmāyaṇas: grouping them along “family resemblances.”24

But what about visual ways of enacting the Rāma story? These, I believe, and not surprisingly, pursue their own logic and follow sovereign aesthetic interests. Besides, the experience of viewing a painted manuscript like the Mewar book is different from that of reading the Vālmīki text or listening to it; so too is the feel of moving around a temple to engage with sculpted Rāmāyaṇa imagery. For one, the perception of narrative time is altogether independent. Consider, for example, the Rāmāyaṇa scenes on the southern elevation of the Papanatha Temple (mid-8th century CE) at Pattadakal in northern Karnataka (Figure 1). This sandstone temple is probably one of the earliest with such a full visual program and boasts over twenty-five sculpted panels that recount the tale, starting with Daśaratha’s yajña to obtain male heirs and ending with Rāma’s coronation after Rāvaṇa’s defeat. Whereas a devotee performing ritual worship must move around the temple in a clockwise manner, an individual interested in the Rāma story sculpted on the temple walls must perforce reverse that movement.25 That is, if the aim is to follow the story’s arc from “beginning to end.” The Rāma tale in fact progresses from west to east rather than the east-to-west motion required of ritual circumambulation.26 But what if these relief images were never meant to be viewed causally but rather discretely or as smaller sequences? Perhaps eighth-century spectators moved back and forth as we do in an art gallery or museum, or possibly they stopped at certain spots along the temple depending on their preferences. Such haptic dimensions and the kinds of visual and spatial relationships that spectators could create among scenes are unique to this building’s spatial aesthetics and its sculptural decor. Moreover, these dimensions not only alter one’s experience of narrative time but also depend on the body’s motion and position. For it is only through the body poised in space that such connections are forged. Examples like the Papanatha temple lead me to ask if we can find an approach to the Rāmāyaṇa that is both broadly applicable across media, while also recognizing the aesthetic autonomy of each medium. In other words, I am interested in an analytic that does not view creative productions in any art form as secondary to or beholden to those in another.

I am also interested in material structures and their potential relations to textual means. In some cases, there may be convergences or parallels between visual and verbal representations, but in others we will surely encounter divergence, dissonance, and slippage. The makers of this same medieval Deccan temple also included lithic texts naming the drama’s key characters (Figure 5). How were these words “seen”, and how were the accompanying pictures “read”? And, moreover, what part did spectators play in seeing-reading? It would be useful at this stage to introduce W. J. T. Mitchell’s idea of the ekphrastic exchange. Mitchell discusses two types of transformation that occur in the creation and experience of an ekphrastic text: First, the creator fashions a verbal representation from a visual one; then this verbal representation has to be transformed back into the visual by the audience who encounters the text.27 But what happens in the minds of receivers when text and image live side by side as at the Papanatha Temple, or in the far more complex configuration of the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa? It seems to me that it would be a mistake to downplay the involvement of the recipient who forms one vertex of this triangle whose other vertices are words and pictures.

Figure 5.

Rama Kills Valin, Papanatha Temple, ca. 8th century CE, Pattadakal, Karnataka, India. Photo: Caleb Smith.

3. Rāmāyaṇa Time, Rāmāyaṇa Space

Because it would be impossible to do justice to a single enactment, let alone two complex ones, in the span of an article, I concentrate on two crucial and contentious episodes in the Vālmīki and Mewar Rāmāyaṇas. This allows for a consideration of the creative resources of each book as well as those books’ approaches to two standard subjects of ekphrasis: time and space (or events and places).

Let me begin with the event that is essential for the Rāmāyaṇa’s dramatic arc, and propels it forward: Queen Kaikeyī’s demand that Daśaratha exile Rāma. The Mewar Rāmāyaṇa devotes two paintings to these developments, while the same action plays out in three chapters (sargas) of Vālmīki’s text. Image first, then text, starting with folio 24 of Mewar’s Ayodhyā book (Figure 6), which the artist ingeniously organized to simultaneously depict the sequence of interactions between Daśaratha and Kaikeyī. A vivid red enlivens this painted world and its four architectural subdivisions. The artist repeated Kaikeyī four times, and Daśaratha thrice. In a series of foundational publications, Vidya Dehejia has unpacked the narrative conventions of premodern Indian art and developed a handy set of terms to explain their representational strategies.28 She has shown, for instance, that the recursions of the Mewari painting, which she identifies as a synoptic narrative mode, were meant to signify independent temporal moments.

Figure 6.

Kaikeyi Demands Her Boon, folio from Jagat Singh’s Ramayana manuscript, Mewar, ca. 1650-2, watercolor on paper. Courtesy: The British Library Add. MS 15296(1).

Building on that work, which concentrates on “reading” these paintings through literary categories, I want to focus on how these paintings denote temporal experience and describe space differently from textual ways of doing so. For instance, unlike the feel of reading or recounting the corresponding events, which unfold chronologically, the viewer can access multiple temporalities at a single glance. In the painting’s left, Kaikeyī sulks on the floor in a large chamber that takes up almost the entire left half of the painting. The artist depicted her as if seen from above, lying on a white mat that he tilted up to accentuate the queen’s hourglass figure. But wait. Kaikeyī appears again, in the very same space, standing across from Daśaratha, presumably moments later. Because I have no recourse but to turn to language to describe these pictorial modus operandi, they still seem to unfold sequentially. Yet this does not correspond with our ocular experience. For optically, we can absorb the entire image.

This is equally true for the action occurring in the painting’s other rooms. Turning our attention to the right side of the painting means perceiving two other moments at once. There, two smaller rooms are stacked one above the other. In the top room, a standing Kaikeyī confronts a seated and stunned Daśaratha who listens to her, while the bottom space finds a kneeling Daśaratha entreating her for mercy. Like a lyric poem that compresses universes within its economic form, the artist managed to condense one more temporal pulse into the picture. I refer to the lone male figure at the very center of the image, in the foyer-like space connecting the painting’s two parts. Those unfamiliar with the intricacies of the Rāmāyaṇa and the convention of depicting Rāma with blue skin are quick to suggest that the figure is Rāma. But in fact, this is the king’s charioteer Sumantra, whom the queen summoned at dawn after a long night of tears, accusations, curses, supplications, and impasses. There is also the matter of the landscape peeping over the wall behind Sumantra. How was the viewer meant to comprehend this space? It is tempting to suggest that it and the sky’s silvery outline hint at the sun’s first illuminating rays. The painting, then, encompasses the hours between Daśaratha’s arrival at Kaikeyī’s apartments in the evening up until Sumantra’s tentative entry the morning after.

According to Vālmīki, these intervening hours passed agonizingly slowly for Daśaratha: “to the anguished king lost in lamentation, the night, adorned with the circlet of the moon, no longer seemed to last a mere three watches.”29 As an aubade bemoans the arrival of day and the inevitable separation of lover and beloved, the king addresses the sky, first asking for a cessation of time. “I do not want you to bring the dawn—here, I cup my hands in supplication,” he begged.30 Then, changing his mind almost right away, he begged instead for time’s hastening so that he may escape the misery of Kaikeyī’s company: “But no, pass as quickly as you can, so that I no longer have to see this heartless, malicious Kaikeyī, the cause of this great calamity.”31 To my mind, the Mewar painting enacts some of the temporal phenomena that Vālmīki describes, and more. In the painted universe, time contracts and rushes ahead as if beyond one’s control. Moments are stacked one on top of the other like the chambers of the palace, and evening becomes dawn in an instant. At the same time, the painting makes possible other temporal effects: Viewers may immerse themselves in any room, that is, in any event; they may circle back in time, they may spring forward, and they may experience the drama as many times as they wish, as if in an endless loop, thus staying time indefinitely. Phyllis Granoff has observed that time operates similarly in the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa.32 Looking, for instance, at the dizzying temporal shifts the text makes in recounting premonitions that are told in the future tense while being anchored in a present by which point some of the events are already past or will become the present, she says that past, present, and future are “slippery concepts that slide one into the other and cannot be defined except with reference to each other.”33 In another example, when, in the poem’s first book, author Valmiki learns of the tale of Rama that he must set down, he finds out not only what Rama has done (past) but also what Rama will do (future).34 The Mewar painting, then, presents viewers with an analogously unstable experience of time.

If the painting invites us to “feel” time—its compression, superposition, acceleration, and suspension—then reading Vālmīki invites us to visualize, to “see” (and hear) the encounter between Kaikeyī and Daśaratha. Kaikeyī shamed and harangued Daśaratha into keeping his promise by invoking righteous kings who were true to their word even upon pain of fatal injury. In characteristic Rāmāyaṇa fashion, we get a list. This is no ordinary, colorless catalogue of words, however, but one that bristles phenomena into being. First, the shrewd queen called forth Śaibya, who fed his flesh to a hungry hawk; then, she recalled Alarka, who plucked his eyes out for a learned brahmin. As if the vision of a man wrenching his eyeballs from their bloody sockets were not rhetorically sufficient, Kaikeyī went oceanic on Daśaratha. The ocean, too, that “lord of rivers,” she claimed, did not go back on his word, and “in accordance with the truth does not transgress the shore he pledged to keep.”35 Kaikeyī and Daśaratha’s interactions advance and recede like the waves the poet evokes, with Vālmīki shifting from one viewpoint to the other using both dialogue and ekphrastic description. Daśaratha cajoled, he ranted, he cried, he fainted, and he started again. Kaikeyī pouted, she demanded, she sneered, she insisted, and the text jumps between them cinematically, quickly, rather than through long monologues as it does in the encounter between Rāma and Vālin that I will examine later. After Kaikeyī’s onslaught, Vālmīki zoomed in on the king with a simile that packs a sensory punch. Daśaratha’s heart “began to beat wildly, his face was drained of color, he was like an ox struggling between the yoke and wheels.”36 Even then, Daśaratha manages to marshal some reserve energy to launch a final volley at Kaikeyī, but she crushed him once and for all. It is at that point that she called for the charioteer Sumantra.

Without a doubt, Vālmīki’s imagistic language moves us. It makes the pair and their night-long conflict come alive. Yet the poet did not simply conjure the characters from the Rāma tale, so that we picture them pacing and arguing in the palace’s interior, he augmented the dramatic tensions between them through citations well outside his main narrative frame. Whereas the painting’s red and yellow borders contain Kaikeyī, Daśaratha, and Sumantra, and only those three, Vālmīki faced no such limitations. Śaibya and Alarka create additional references in interlocutors’ minds to those conflicts, both inner and outer, as do the sensory allusions to the ocean’s restive movement and the ox heaving and laboring under its burden. Thus, one of the attractions of looking and reading is that the aesthetic means of one medium are foregrounded in contradistinction to the silences of the other. If looking at the Mewar folio permits an experience of time altogether different from the linear experience of unfolding events, then reading Vālmīki permits a fuller sensory enactment of the conflict between Kaikeyī and Daśaratha, which allows us not only to see them but to hear them and imagine sensations and conflicts beyond the confines of the rooms in which these characters find themselves.

The representation of space—architecture in particular—is another dimension that brings the aesthetic faculties of each medium to the fore and the unique thrill of placing literary texts and visual material in dialogue with one another. As we know, Kaikeyī’s and Daśaratha’s encounter took place in the Kosalan capital Ayodhyā, in the queen’s inner apartments. The question I would like to explore first is how the epic text imagines Ayodhyā and its built spaces. It is perhaps befitting as the home of righteous Prince Rāma that Vālmīki’s Ayodhyā is enchanting and orderly, like Amarāvatī, the heavenly city of Indra, the lord of the gods. Its palaces are jeweled palaces and its royal highway fragrant and flower-strewn. Surrounded by water and impregnable walls, the city is endowed with the most beautiful women and people of excellent character. Sweet water and plentiful sustenance nurture its inhabitants, who delight in music, drama, and poetry, and relax in shady parks and mango orchards. Seemingly, bards can only rhapsodize about this city, as Vālmīki does in Book I:

It was a great and majestic city, twelve leagues long and three wide, with well-ordered avenues.

It was adorned with a great and well-ordered royal highway, always strewn with loose blossoms and constantly sprinkled with water.

…

It was a fortress with a deep moat impossible to cross, was unassailable by its enemies, and was filled with horses, elephants, cows, camels, and donkeys.

It was splendid with hills and palaces fashioned of jewels. Bristling with its rooftop turrets, it resembled Indra’s Amaravati.

Colorful, laid out like a chessboard, and crowded with hosts of the most beautiful women, it was filled with every kind of jewel and adorned with palatial buildings.

Situated on level ground, its houses were built in close proximity to one another, without the slightest gap between them. It held plentiful stores of śāli rice, and its water was like the juice of sugar cane.

Loudly resounding with drums and stringed instruments—dundubhis, mṛdañgas, lutes, and paṇavas—it was truly unsurpassed on earth.

The outer walls of its dwellings were well constructed, and it was filled with good men. Indeed, it was like a palace in the sky that perfected beings had gained through austerities.37

Vālmīki appeals to our senses of sight, sound, smell, and taste, and employs some eye-popping metaphors like the city’s intricate chessboard grid. Despite such literary verve, however, it is impossible to picture this colorful city. What does this “palace in the sky” populated by “perfected beings” look like? Indeed, many of the same tropes, most notably the comparison to Indra’s Amarāvatī, find their way into descriptions of Laṅkā, demon-king Rāvaṇa’s stronghold. Similarly, the palace in which Kaikeyī and Daśaratha struggle does not come into view, for it simply “resembled Indra’s great abode.”38 Descriptions of Rāma’s palace are equally allusive, even if ravishing in their nature imagery: “It resembled a mountain peak or a motionless cloud, with a complex of buildings more splendid than aerial palaces, and the charioteer made his way through it unchecked, like a dolphin through the gem-stocked sea.”39

Now, contrast Vālmīki’s Ayodhyā with that of Mewar’s folio 24 (Figure 6). Whereas the epic poem presents an unimaginable ideal—an ineffable city of cloud mansions and celestial palaces—the Mewar manuscript is of this earth, grounded in particularities rendered in vivid line and vibrant color. These people have flesh, these spaces have contours. Moreover, in a fashion characteristic of much premodern South Asian art, the beholder experiences space from multiple viewpoints at once. Like the experience of time discussed previously, space too is layered, along the horizontal and vertical axes. Interiors and exteriors are visible simultaneously as are multiple stories of the palace. The palace’s elevation, with its grey sloping eaves and painted rooflines, is juxtaposed with an interior view of its rooms. Inside spaces are lavish, colorful stages for the narrative action. Niches outlined in white paint—against bright red backgrounds—showcase gold vessels. In the largest chamber, a gold door decorated with eight-pointed stars serves as a backdrop for the conversation between our two protagonists.

That these offer glimpses into the material culture of seventeenth-century Mewar is a tantalizing proposition. Is this an “indexical translation”, to use Ramanujan’s concept, that indigenizes the Rāmāyaṇa by incorporating local color, customs, and traditions?40 A brief excursus into dress and ornament, and the appreciative detail with which the artist outlines them, seems to say yes. From the crisscross pattern the men’s jama makes on their chests to its looping side fasteners, from the effortless translucence of the jama’s billowing muslin skirt to its pairing with patterned cummerbunds and dapper pajamas, the painting shirks no detail of Daśaratha’s and Sumantra’s dress. The same could be said for Kaikeyī’s attire. Her lower garment echoes the red of her spatial surround in a checkerboard design the painter contrasts with a short blue blouse, highlighted in gold zari at the sleeves and neck, and further accentuated with a transparent veil draping the queen’s head and upper body. Whereas Vālmīki’s Kaikeyī is bereft of ornament by the time the king comes to see her, Mewar’s Kaikeyī is sumptuously adorned. It is worth taking a moment to pause over this slippage between text and image. Although most scholars highlight the slavish fidelity of the Mewar paintings to Vālmīki’s text, I would venture that these painted worlds declare their sovereignty. Another arena in which the visual pursues its own path is in the lapidary treatment of ornament, which also helps to showcase the Mewar painter’s talents. Using precisely calibrated dots of white paint, he spells out, individual bead by individual bead, anklets, earrings, delicate nose rings, pendants, and the silhouette of Daśaratha’s golden crown. Save one pair of hoop earrings and a necklace, which lie desultorily before Kaikeyī, the rest of the jewels remain attached to bodies.

While there is no denying my own evident enjoyment in the ekphrastic opportunities the painting presents, I am not convinced that it and others like it “picture” seventeenth-century Rajasthan in any illusionistic sense. Obviously, the painted architecture in these pictorial worlds bears a passing resemblance to contemporaneous Rajput (and Mughal) buildings: The interiors of the latter also feature scalloped niches for the display of decorative objects; chatri pavilions mark rooflines, arched apertures punctuate elevations, and deep eaves provide relief from the sun, to cite a few parallels. Yet it seems to me that the Jagat Singh Rāmāyaṇa is less informative about the particulars of that ruler’s Mewar than it is about the procedures and protocols of painting in his epoch. What these paintings reveal is how painters thought about time, space, things, the human figure, urban environments, landscapes, and other subjects of painterly interest. They are valuable for their insight into image-making in premodern western India, not as documentary accounts of this place at this time.

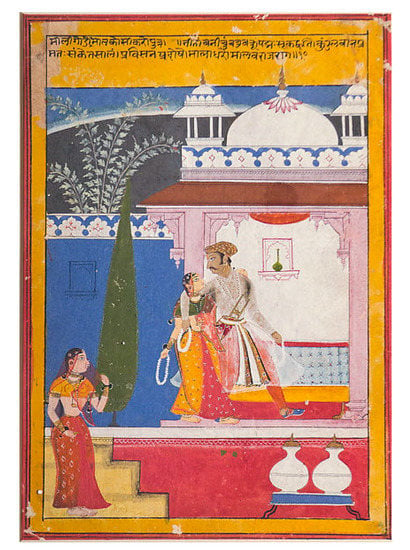

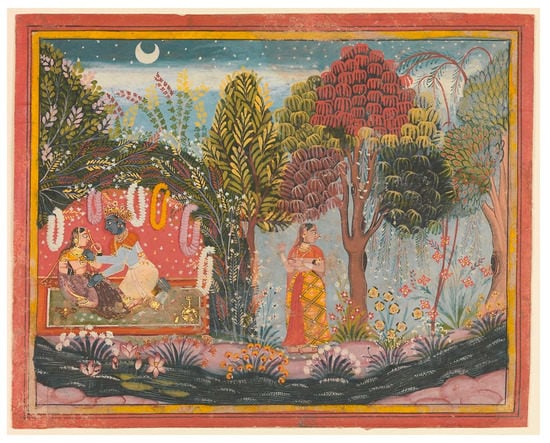

Because space does not permit an extensive substantiation of my claim, one distinctive example will have to suffice: a Rāgamālā painting in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Figure 7), also attributed, like the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa’s Ayodhyā book, to master painter Sahibdin (c. 1620—55). Dated to 1628, the Met image predates our illustrated Rāmāyaṇa by at least a couple of decades. By comparison, the Ayodhyā book’s 68 paintings were likely completed between 1648 and 1652.41 Rāgamālā refers to a genre of painting that was popular at the Rajput courts, whose workshops produced collections or garlands (mālās) of paintings to allegorize musical modes (rāgas), which were expressively associated with a specific time of day, season, and gender. A two-line inscription at the top of the Met painting hints at the evening atmosphere that the painting evokes. But, unlike the Rāmāyaṇa folio, the Met’s lovers gaze ardently at one another and step towards a chamber, arm in arm, where a bed awaits. A second female figure, possibly a servant, looks on discreetly from a level below, her backdrop a set of abstracted stairs like those behind Sumantra in the Rāmāyaṇa page. Although temporally distant, the resemblances between the two images are uncanny. Pictorial space is characteristically two-dimensional: Depth is conveyed by vertical arrangements rather than through the illusion of spatial recession. Unmodulated bands of bold color serve to foreground figures, who are enframed in stage-like architectural settings. The eaves of buildings are treated exactly alike, while the painted pattern of the roofline and the wall border is almost identical. Landscapes too are eerily familiar—from the high grey horizon with its silvery outline to the tall palm-like fronds in the foreground. In the treatment of the human figure, the same profile views of the head and details of costume confront the viewer. Certain specifics, like the stairways behind the subsidiary figures that indicate an interstitial moment or intermediary space, in my view, are too idiosyncratic to be attributed to mere chance.

Figure 7.

Malavi Ragini: Folio from a Ragamala Series, Artist: Sahibdin, 1628 CE, opaque watercolor and ink on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Lent by Private Collection.

What does all this mean in the context of this essay’s interests in looking and reading? On the one hand, Vālmīki’s Ayodhyā is a divinized, dreamy realm that is difficult to picture, even if the corresponding passages are affectively rich. We might say this is a notional ekphrasis, meaning the representation of an imaginary subject in which language displaces rather than discloses the subject.42 On the other hand, and in sharp contrast, Mewar’s Ayodhyā is patently visible, given the very nature of the medium being considered. Still, it would be a mistake to correlate this city and the one that would have been breathing outside the page. The cityscapes in the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa are not “portraits” of Udaipur, Rana Jagat Singh’s lakeside capital, even in the loosest sense of that term. The parallels, rather, are with other paintings such as the Met’s Rāgamālā painting, which served in all likelihood as visual models for Rama’s Ayodhyā. Andrew Topsfield finds that Sahibdin perfected his treatment of space in a number of earlier projects, including the Rāgamālā series, but also in Gīta Govinda, Bhāgavata Purāṇa, and Rasikapriya manuscripts.43 In depicting Ayodhyan architecture, Topsfield writes that Sahibdin “relies on the conventional single or two-storeyed pavilion types of the 1628 rāgamālā, enlarged, elaborated, and multiplied to fill the lengthened pothi page.”44 It is worth noting that the Rāgamālā series, consisting of 42 painted pages, was Sahibdin’s earliest known work and was completed soon after Jagat Singh ascended the Mewar gaddi.45 Certainly, as Topsfield points out, those earlier paintings are vertically oriented while the Rāmāyaṇa pages follow the older, horizontal pothi format; nonetheless, Sahibdin used the same stacking and segmenting tactics to fashion built spaces. The use of strong background colors, too, to depict palace interiors is a conventional schema, worked out in those earlier works.46 Look, for example, at the red interior of the bower in which Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā meet in a Mewar Gīta Govinda folio currently in the Met’s collections, also attributed to Sahibdin (Figure 8). It is clear that whether the painting’s protagonists find themselves in an outdoor or a court setting, the same bright red interior sets them off, like the red and yellow borders of the pictures. Some of the same unmistakable pictorial strategies characterize Rāvaṇa’s Laṅka in the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa’s sixth book, the Yuddhakāṇḍa or Battle Book, also credited to Sahibdin’s hand.47

Figure 8.

Krishna and Radha in a Bower: Page from a Dispersed Gita Govinda, Artist: Sahibdin, ca. 1665, ink and opaque watercolor on paper. Accession Number: 1988.103, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ernest Erickson Foundation, 1988.

In an important sense, the formal strategies of Vālmīki and Sahibdin are identical. They both rely on hard-won conventions, consistent and legible schemata—one linguistic, the other pictorial—to represent diverse spaces, be they in Rāma’s kingdom or demon-king Rāvaṇa’s fortress. Yet, of course, Ayodhyā and Laṅkā are the epic’s two moral poles, representing righteousness and its assailants. Similarly, the epic text’s author invests its antagonists, the rākṣasas (demons), with many of the same virtues as their human counterparts—valor, learning, loyalty, filial piety, and physical allure.48 Rāvaṇa’s downfall is his transgressive desire for another man’s wife. Visual representations of the epic’s supposed opposites, too, share affinities: rendered through similar perspectival, coloristic, and technical strategies. Historians of literature and visual art, however, have pursued such representations for their referential insight into existing geographies and peoples. One view is that Vālmīki describes ancient Indian landscapes and cityscapes as they were, while Sahibdin gives us the palaces and pavilions of Rajput lords and ladies. Likewise, the denizens of these worlds must correspond with contemporary social groups: Rāma and his clan representing ancient India’s desirable social order and the demons standing in for groups who threatened that order, possibly tribal people or those falling outside the caste hierarchy. Some have even pointedly equated the Mewar book’s rākṣasas with the Rajput kingdom’s Mughal adversaries.49

However, as Sheldon Pollock has sharply responded, this kind of historicizing is the least interesting thing we can do.50 It fails to adequately recognize these painted worlds and textual universes as works of the imagination. So how then do figures like the rākṣasas signify in these constructed realms? Rākṣasas, Pollock proposes, embody the fears of Brahmanical India: fear of the unknown, fear of the theft of its women, and fear of miscegenation.51 Pollock’s rejoinder is convincing not because it stands on formal, aesthetic, or sociological grounds but rather on psychological terrain. I include it not to foreclose other readings but to signal the kind of interpretive work that remains to be done, and to invite us to think about what the makers of the Rāma story reveal about themselves. That is, to shift from thinking about the Rāma story’s ekphrastic tactics to the Rāma story as ekphrasis.

4. Sugrīva’s Garland and Social Difference

This brings me to another contentious encounter in the Rāmāyaṇa—Rāma’s slaying of monkey-king Vālin. As one of the episodes that exposes the moral complexities of the epic and the failings of its virtuous hero, the affair has rightly generated considerable interest from Rāmāyaṇa commentators, theologians, creative artists, performers, and audiences. In addition, I want to suggest that how makers chose to enact this episode is a major tell. Such exercises in Rāmāyaṇa making are self-portraits, revealing makers’ and making cultures’ preoccupations and positionality.

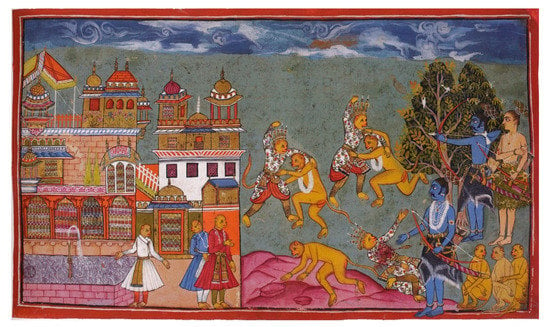

The incident springs from Rāma’s involvement with Kiṣkindha, the vānara, or the monkey kingdom to which he and Lakṣmaṇa travel in search of Sītā. Like the rākṣasas, the vānaras are fascinating creatures described by various Sanskrit terms, of which the most significant is kāmarūpin (“changing form at will”) to suggest their extraordinary magical powers.52 They seem to occupy an intermediate zone between human and animal, leaning towards one or the other depending on the situation and the Rāmāyaṇa enactment. On the one hand, they exhibit most human traits—they dwell in houses, wear dress and ornament, and uphold the manners of kingship and kinship—and on the other, their capabilities to leap immense distances and their unruly and immoderate personalities emphasize their beastly natures.53 Through the vānaras, Rāma learns more about Sītā’s abduction, and the path Rāvaṇa followed when he forcibly took her to Laṅkā. The vānaras are eager to help Rāma look for Sītā, but there is a catch, of course. Rāma must first help Sugrīva, an exile like himself. Banished by his brother, Vālin, who is also Kiṣkindha’s reigning king, Sugrīva has been reduced to wandering the forests with a band of loyal followers. A second parallel between Rāma and Sugrīiva is their forced separation from their wives because Vālin has appropriated Sugrīva’s mate after evicting him from their homeland. Indomitable warrior though Vālin is, Rāma manages to kill him swiftly. But it is the manner of the killing that gets to the core of the ethical quandary, as Rāma shoots Vālin from a hiding place, without provocation, while Vālin is deep in hand-to-hand combat with Sugrīva.

Each of our two Rāmāyaṇas deals with this troubling incident through their distinct imaginaries. Vālmīki seems primarily concerned with asserting cultural differences (between human society and that of the vānaras) and articulating the nature of just kingship. Mewar grounds us firmly in time and space and uses the synoptic mode once again to collapse a number of temporal moments into a single dense frame. Vālmīki devotes one entire chapter (sarga) to Vālin’s bitter take-down of Rāma for his cowardly behavior, following Vālin’s mortal injury:

Since I didn’t see you, I had no idea you would strike me when I was in the heat of battle with another, heedless of you.I did not know that your judgment was destroyed and that you were a vicious evildoer hiding under a banner of righteousness, like a well overgrown with grass.I did not know that you were a wicked person wearing the trappings of virtue, concealed by a disguise of righteousness like a smoldering fire.54

Even though the poet lets Vālin speak first and at length, he nonetheless gives Rāma the final sarga-length word. Rāma outlines the hierarchical values of Brahmanical society (particularly regarding the correct attitude towards a younger brother’s wife), the prerogatives of ancient Indian kingship, and his right, as the proxy of the lawful human king, to punish Vālin, a mere monkey. Rāma explains his actions by invoking his promise to aid Sugrīva as well as his right to censure Vālin for claiming Sugrīva’s wife. What is important here is that the idea of unchecked desire and the usurpation of a woman is a theme that runs through this episode, as it does through the entire Rāmāyaṇa; and Rāma’s punishment of Vālin prefigures his actions in the book’s penultimate War book with his killing of Rāvaṇa for a similar crime.

Rosalind Lefeber proposes that Sugrīva and Rāma found themselves in a similar bind—deprived of kingship and deprived of wifely love—and so turned to each other for mutual support.55 Rāma interfered in the brothers’ dispute out of self-interest. With Vālin out of the way and Sugrīva installed as Kiṣkindha’s ruler, Rāma could gain access to the material might of the vānara legions essential to his search for Sītā. Consequently, Rāma justifies an action that would have been unjustifiable even by the ethical precepts of his own kind. Vālmīki’s Rāma repeatedly emphasizes Vālin’s alterity. He asserts Vālin’s subhuman position, far below the social realm to which he and his warrior (kṣatriya) clan belonged. Moreover, human moral codes must be clarified for these “monkeys.” Vālmīki’s Rāma is most egregious, surely, when he claims his inalienable right to hunt Vālin, because the latter is, after all, only an animal. In a formulation all too familiar from present-day articulations of racial prejudice, Rāma claims that he has trouble distinguishing between Sugrīva and Vālin, and gives Sugrīva a flower garland to wear so that he can aim his arrow at the correct vānara!

I should point out that Sugrīva challenges Vālin to fight upon Rāma’s urging, so as to give Rāma the opportunity to kill Vālin, but in the first encounter, Rāma does not shoot as he could not tell Vālin and Sugrīva apart. This necessitates a second challenge and the flower garland. Strikingly, Sugrīva’s garland finds a visual counterpart in the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa.

Indeed, though painters were faithful to this aspect of Vālmīki, the paintings establish difference in their own way. As my students are quick to point out, no one could mistake Vālin and Sugrīva (let alone Rāma) in the painted Kiṣkindha. The paintings use a number of strategies to disaggregate vānaras, of which the most important is dress. Dress differentiates forest-dwelling vānaras from their urban (and urbane) counterparts, and high-ranking individuals from those in the working classes. In both pages of the Kiṣkindha book that depict the battle between Sugrīva and Vālin (folios 16 and 18), the visual artist invests Vālin with the attributes of kingship as understood in seventeenth-century Mewar. A beautiful, floral-pattern jama covers much of Vālin’s body in folio 18 (Figure 9), and a jewel-studded crown sits above his head even while he is wrestling with Sugrīva. Sugrīva, by contrast, is not only naked except for his garland, but artists emphasize his red posterior (a detail that does not fail to delight viewers). This detail, along with a pink snout, characterizes many of the Kiṣkindha book’s naked vānaras. Another careful costume effect is the change that occurs in Sugrīva himself: Sugrīva resembles a forest-dweller during his exile (meaning he is naked), but appears with proper royal regalia including diadem, jama, and parasol after his coronation. Thus, unlike the Sanskrit epic, there is no ambiguity in these painted pages between the king, Vālin, and his exiled brother, Sugrīva.

Figure 9.

Rama Kills Valin, folio from Jagat Singh’s Ramayana manuscript, Mewar, ca. 1650-2, watercolor on paper. Courtesy: The British Library Add. MS 15296(2).

The Mewar Rāmāyaṇa’s sartorial manners find no equivalent in Vālmīki. Vālmīki is not particularly concerned with the visual details of the vānaras or their kingdom. True to their metamorphosing nature, Sugrīva and Hanumān assume human form in certain interactions with Rāma and Lakṣmaṇa and change back to their “true form” after, but it is unclear how readers should visualize that form.56 Meanwhile, Mewari painters appear to have resolved such questions. Take the vānaras on the edges of folio 18 (Figure 9). The three on the left, who are also the only individuals in an architectural setting, are clearly meant to be high-society beings. They are bipedal, attired in jama, pajama, and cummerbund, with tails tucked away; their only simian features are their faces. Their three counterparts in the right corner, however, are conspicuously naked, seated on their haunches and with those characteristic pinkish faces and bottoms I mentioned before. The painted milieus thus pursue their own logic: Painters use dress and ornament to communicate social difference in the monkey kingdom.

A few words also need to be said about the palaces and landscapes that adorn these pages to enliven the vānara realm. It is interesting to note that Kiṣkindha’s palaces are posh, multi-storied dwellings equipped with a variety of roof types: domes, Bangla roofs and chatris. Courtly pleasures are suggested by fountains and lotus-filled pools in courtyards surrounded by shady arcades. Lattice window screens and breezy rooftop pavilions further heighten this atmosphere of luxury and sensory delight. Rather than assert any mimetic relationship between Kiṣkindha and Mewar, though, what these pages show then are painterly ways of making Kiṣkindha and its denizens present. They capitalize on visual means: scale, color, perspective, and visual ways of representing bodies, architecture, and landscape features. Even though painters include a detail like the garland from the Sanskrit text, they contradict the text and depart from its intent in clearly distinguishing Vālin and Sugrīva as individuals occupying vastly different social stations.

Taken together, looking and reading uncover striking convergences between our two Rāmāyaṇas, such as Sugrīva’s flower garland or a shared sense of time’s instability, as well as aesthetic strategies reflective of the resources of each medium. Recall Sahibdin’s partitioning tactic for envisioning Ayodhyan and Lankan palaces and Vālmīki’s metaphor of celestial Amarāvatī to conjure the very same places. There can be no doubt that the charged dialogue between Vālin and Rāma is a tour de force of the Vālmīki text for which there is no analogue in painting. In a like manner, the Mewar paintings’ talent for conjuring people, places, and movement is unparalleled by textual media. Foregrounding such jealousies between media is possibly one thrill of looking at the Mewar folios while reading Vālmīki alongside. It is in the spirit of paragone, an ekphrastic stance defined by interart rivalry, wherein art forms compete against one another in adversarial relationships that measure the representational capabilities of one against those of the others;57 a painting’s ability to show, for instance, versus poetry’s ability to sing and say. But if art forms work against one another in some instances, they also serve to bridge silences in others, so that looking and reading side by side is akin to juxtaposing an open mouth with the accompanying speech and having one Rāmāyaṇa enactment leap across another’s reticence. Looking and reading, then, activate each one of the senses and all of our imaginative powers so that we receivers make the Rāma story together with painters and poets.

5. Rāmāyaṇa Making as Ekphrasis

The colophon of Mewar’s Ayodhyā book tells us it was made for the viewing pleasure of Rana Jagat Singh;58 however, the Rāmāyaṇa itself was not complete during Jagat Singh’s lifetime, but only a year into his successor’s reign in 1653.59 Yet it seems inconceivable that the Rana waited for the completion of the whole book to immerse himself in the already finished folios. In any case, given the sheer volume of paintings (circa 450 total painted pages), it would have been difficult for the ruler or other members of his court to view all the books together. It is far more likely, because the folios were unbound, that individual paintings were passed around in viewing sessions,60 and like my ekphrasis seminar, or this article for that matter, people focused on a certain number of paintings, perhaps striking sequences like the killing of Vālin or salient themes such as kingship.

And what about the relationship between the energetic painted imagery and the accompanying Sanskrit text? Art historians have been fascinated by this topic. And most scholars who have written on the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa have reflected on this question.61 More to the point, they accord primacy to the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa, which they believe guided pictorial decisions and visual forms: The images are considered visual articulations of linguistic or narrative phenomena. Yet it is difficult to reconcile such views with the pictorial evidence of the book. Granted, I could examine a mere fraction of it here, but the proof is in the paintings’ details: Sugrīva’s garland, say, or Kaikeyī’s ornaments. While the inclusion of Sugrīva’s garland may indeed be an instance of the visual behaving as “a literal translation of the verbal,”62 as we have just seen, the paintings have their own mind and do not simply ape the text. So how about Kaikeyī’s ornaments? According to Vālmīki, by the time Daśaratha arrived at the queen’s chambers, “the lady put all her jewelry aside and lay down upon the ground bare of any spread, like a fallen kimnara woman.”63 In other words, the unadorned Kaikeyī was lying upon barren ground. And yet, clearly, Sahibdin and the painters of Mewar’s Ayodhyā book have taken a different tack for enacting this episode between king and queen. The painter situated Kaikeyī on a white mat, diagonally arrayed and tilted up to foreground the queen’s body, and moreover, though he scatters a necklace and earrings on the floor before Kaikeyī as a nod to Vālmīiki (or possibly local/oral knowledge of the tale), the queen is amply adorned, as we already saw (Figure 6).64 Here we must conclude that articulating the queen’s social status through her richly ornamented and finely attired body is more important than any interest in translating textual protocols. After all, Kaikeyī had to be visually legible as a queen to her seventeenth-century Mewari audience.

What I have tried to argue in this essay is that the Mewar paintings and the Vālmīki text are both ekphrastic responses to the Rāma story: each enactment an independent creative endeavor engaged in the act of Rāmāyaṇa making. It is worth emphasizing again that I think of ekphrasis, not only as a rhetorical tactic for making pictures speak, but also as an embodiment of the Rāma story in any medium or in interart media. The crucial point is the visibility that ekphraseis offer of their makers’ aesthetic preoccupations and resources. Contemporary American poet J.D. McClatchy writes in the edited volume, Poets on Painters, that in ekphrasis artists “found ways to describe themselves, or more generally, to describe the creative process itself.”65 Ekphrasis, McClatchy adds, “represents a portrait of the artist’s mind, an image for states of feeling, and planes of thought, an embodied temperament.”66 Of course, this is not to say that we have access to the subjectivities or sensibilities of premodern makers or to deny the inappropriateness of perceiving their agency in terms of the interests or motivations of twentieth-century artists. Indeed, both Vālmīki and Mewar are incredibly heterogeneous productions and neither can be attributed to a single maker. Still, the preceding pages revealed Vālmīki’s and Mewar’s distinct aesthetic procedures for enlivening the Rāma story’s characters and situations.

Though Vālmīki’s historicity is uncertain, the tradition unequivocally attributes authorship to such a figure. 67 Moreover, that tradition is self-conscious about the epic poem’s creation as well as its aesthetic commitments. Vālmīki is integral to the origin narrative of the poem and plays an essential part in its frame story. Vālmīki is both author of, and character in, the work. We learn early on, for instance, how he came to the story of Rāma and found the meter and mood for the poem. Vanishing from the narrative after this point, he reappears again in the last book, thus bookending the proceedings. In this seventh book, the Uttarakāṇḍa, after Rāma abandons Sītā she finds sanctuary at Vālmīki’s ashram, where she gives birth to her twin sons Lava and Kuśa. Growing up at the hermitage, the twin boys learn the story of Rāma (the Rāmāyaṇa) under Vālmīki’s tutelage and eventually recite it for Rāma and his court. Vālmīki thus not only describes his creative process (to take up McClatchy’s point again) but also records his poem’s transmission and reception. The Mewar Rāmāyaṇa does not transmit such self-awareness in words, but through the grammar and conventions of painting. That is the important idea that bears repeating and is worth exploring in future studies. We are fairly confident of Sahibdin’s involvement in the Ayodhyā book and Manohar’s in the first book, the Bālakāṇḍa68. The Kiṣkindha book, which I also examined here, is more varied in its visual enactments, and is attributed to an unknown Deccan artist based on stylistic grounds. But only visual analysis can give us insight into these artists’ respective painterly processes, which is a topic that a number of scholars of Rajput painting have explored. I have relied on their findings to foreground Sahibdin’s embeddedness in seventeenth-century painting as well as his commentary on his art-making in the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa. What is at stake in ekphrasis, then, is representation itself, and examining each of these Rāmāyaṇas through the lens of ekphrasis has drawn attention to their distinct creative processes.

One of the surprising discoveries one makes by teaching premodern South Asia is that its protocols of representation tend to be uncharted and unsettling terrain for undergraduate and graduate students alike. Students find that time and space behave in bewildering ways (as do the human figure, the natural world, and other subjects of representation, but those will have to await another day). By looking and reading side by side, my seminar could enter into and tackle such issues of representation. In the visual domain, students learned how to “read” perspective (because works present multiple viewpoints) and unpack pictures governed by some of the temporal and spatial rules I have outlined here. In the realm of literature, too, certain guideposts helped students navigate textual representation. Vālmīki deployed figurations that drew parallels between Ayodhyā and heavenly realms and relied on notable Sanskrit alaṃkāras as well as ornamental tropes such as beautiful women and virtuous people—and a catalogue of sights, sounds, tastes, and smells to embellish his account. Understanding that alamkāra (typically translated as “ornament”) was both a literary device and a wider cultural lens or figuration through which courtly India saw and represented itself gave insight into how Vālmīki’s inventory of Ayodhyā’s multisensorial charms worked on its receivers.69 Similarly, Sahibdin resorted to techniques such as vertically and horizontally arranged spatial compartments, bold background colors, and proscenium-like spaces to vivify Rāma’s city in Mewar’s Ayodhyā book. In the process of analyzing the paintings and reading the epic poem, we interrelated premodern South Asia’s literary and visual representational tactics, and measured one medium against another. We placed ourselves within the imaginative universe of the Rāmāyaṇa and pictured princes and princesses, magical shapeshifting creatures and dangerous forests, and jeweled palaces. We were seized by the moral questions raised by Rāma’s killing of Vālin and wondered how Kaikeyī might be written differently. We were moved by Sītā’s situation and fashioned alternate story arcs for her. We engaged in our own making processes to create the Rāma story anew. As a theater for representation, ekphrasis is an invitation to think about the wider and vaster world of embodiments of the Rāma story and intermedial exchanges beyond words and pictures.70

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the editors, Phyllis Granoff and Sonya Rhie Mace, for the invitation to write and for their thoughtful suggestions for improvement. Many thanks, too, to Joseph Wakeling and the anonymous reviewers of the article for responding to earlier versions of this essay. Finally, I must also thank the students of my Ekphrasis and the Arts of South Asia and Epic India seminars for the conversations and insights that spurred this essay.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources

Goldman, Robert P., trans. and ed. 1984–2014. The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vols. 1–7.Goldman, Robert P., trans. 1984. The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India, vol. 1, Bālakāṇḍa. Edited by Robert P. Goldman. Princeton: Princeton University Press.LeFeber, Rosalind., trans. 1994. The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India, vol. 4, Kiṣkindhakāṇḍa. Edited by Robert P. Goldman. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Narayan, R. K. 2006. The Ramayana: A Shortened Modern Prose Version of the Indian Epic. (suggested by the Tamil version of Kamban). New York: Penguin Books.Pollock, Sheldon I., trans. 1986. The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India, vol. 2, Ayodhyākāṇḍa. Edited by Robert P. Goldman. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Jagat Singh. Rāmāyaṇa. Available online: http://www.bl.uk/turning-the-pages/?id=68b0d8eb-787f-4609-9028-8cd17ff05c96&type=book (accessed on 1 May 2020).Secondary Sources

- Ali, Daud. 2004. Courtly Culture and Political Life in Early Medieval India. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, Jorge Luis. 2000. This Craft of Verse. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, Cathleen. 1999. Composition and Narrative in the Ayodhyakanda of the Jagat Singh Ramayana: A Study of Text and Image in an Indian Manuscript. Master’s thesis, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dehejia, Vidya. 1990. On Modes of Narration in Early Buddhist Art. Art Bulletin LXXII: 374–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehejia, Vidya. 1996. The Treatment of Narrative in Jagat Singh’s Rāmāyaṇa: A Preliminary Study. Artibus Asiae 56: 303–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehejia, Vidya. 2009. The Body Adorned: Dissolving Boundaries between Sacred and Profane in India’s Art. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, Robert P. 1984. History and Historicity. In The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India, vol. 1, Bālakāṇḍa. Edited by Robert P. Goldman. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 14–59. [Google Scholar]

- Granoff, Phyllis. 2019. Is there a Future? Some Answers from Indian Philosophical and Narrative Literature. Global Journal of Human-Social Science XIX: 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hedley, Jane. 2009. Introduction: The Subject of Ekphrasis. In In the Frame: Women’s Ekphrastic Poetry from Marianne Moore to Susan Wheeler. Edited by Jane Hedley, Nick Halpern and Willard Spiegelman. Newark: University of Delaware Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan, James A. W. 1993. Museum of Words: The Poetics of Ekphrasis from Homer to Ashbery. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, John. 1995. The Gazer’s Spirit: Poems Speaking to Silent Works of Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- LeFeber, Rosalind. 1994. Rama’s Allies. In The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India, vol. 4, Kiṣkindhakāṇḍa. Edited by Robert P. Goldman. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Losty, Jeremiah P. 1994. Sahib Din’s Book of Battles: Rana Jagat Singh’s Yuddhakanda. In The Legend of Rama: Artistic Visions. Edited by Vidya Dehejia. Bombay: Marg Publications, pp. 101–16. [Google Scholar]

- Losty, Jeremiah P. n.d. The Mewar Rāmāyaṇa Manuscripts. Available online: https://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/whatson/exhibitions/ramayana/pdf/mewar_ramayana_manuscripts.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Lutgendorf, Philip. 2007. Hanuman’s Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McClatchy, Joseph Donald, ed. 1988. Poets on Painters: Essays on the Art of Painting by Twentieth-Century Poets. Berkeley and Los Angeles: UCLA Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, William J. T. 1994. Ekphrasis and the Other. In Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 151–82. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Sheldon. 1999. Rākṣasas and Others. In The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India, vol. 3, Araṇyakāṇḍa. Edited by Robert Goldman. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 68–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett, Frances. 1996. The World of Amar Chitra Katha. In Media and the Transformation of Religion in South Asia. Edited by Lawrence Babb and Susan Wadley. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 76–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanujan, Attipate Krishnaswami. 1999. Three Hundred Rāmāyaṇas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translation. In The Collected Essays of A.K. Ramanujan. Edited by Vinay Dharwardker. New Delhi and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 131–60. [Google Scholar]

- Topsfield, Andrew. 2002. Court Painting at Udaipur: Art under the Patronage of the Maharanas of Mewar. Ascona: Artibus Asiae Publishers, Zurich: Museum Rietberg. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, Ruth. 1999. Ekphrasis ancient and modern: the invention of a genre. Word and Image 15: 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, Helen J. 1994. Royal Legitimation: Ramayana Reliefs on the Papanatha Temple at Pattadakal. In The Legend of Rama: Artistic Visions. Edited by Vidya Dehejia. Bombay: Marg Publications, pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

| 1. | I am riffing on the title of Ramanujan’s pathbreaking essay. See (Ramanujan 1999, pp. 131–60). |

| 2. | Ibid. |

| 3. | Ibid., pp. 156–58. |

| 4. | For a discussion about the dates of composition, see (Goldman 1984, pp. 14–23). |

| 5. | Webb traces the beginnings of this understanding precisely to 1955 and the writings of Leo Spitzer. See (Webb 1999, p. 10). |

| 6. | For more on these varied ekphrastic stances that a poem can take vis-à-vis its subject, consult (Hollander 1995). |

| 7. | Heffernan begins his genealogy of ekphrasis with this claim, and moreover, finds ekphrasis to be “as old as writing itself in the western world.” See (Heffernan 1993, p. 9). |

| 8. | (Webb 1999, p. 11). |

| 9. | Ibid., p. 13. |

| 10. | Webb suggests that modern critical writers have treated the term cavalierly, bent it to suit their purposes, and been largely unmindful of its ancient meaning and literary history. Ibid., p. 8. |

| 11. | Both Heffernan and Mitchell offer this succinct and powerful definition of ekphrasis. See (Heffernan 1993, p. 3; Mitchell 1994, #1). |

| 12. | Webb finds this to be at the heart of the ancient definition. See (Webb 1999, p. 13). |

| 13. | See (Lutgendorf 2007). |

| 14. | For an extended treatment of such issues see (Pritchett 1996, pp. 76–106). |

| 15. | See R.K. Narayan, The Ramayana: A Shortened Modern Prose Version of the Indian Epic (suggested by the Tamil version of Kamban) (New York: Penguin Books, 2006). |

| 16. | I have relied on Losty’s excellent account of the Mewar book for many of the factual details about the manuscript. (Losty n.d., p. 17). |

| 17. | Ibid, p. 16. |

| 18. | (Dehejia 1996, pp. 303–4). |

| 19. | See Robert P. Goldman, trans. and ed. The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India, vols. 1–7 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984–2014). |

| 20. | For a detailed introduction to the translation project and the translators who worked on the epic’s seven books consult the research note produced by the University of California at Berkeley, where the Goldmans are based. http://southasia.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/shared/documents/Ramayana_FINAL.pdf. Accessed on: May 1, 2020. |