1. Introduction

As

Finke and Martin (

2012) have noted, the study of religious freedom from a sociological perspective is a comparatively new enterprise. Cross-national data collection on religious freedom began to emerge from around 2000, with the development of religious-freedom indexes applied internationally (

Grim and Finke 2006). During the last three decades social scientists have investigated religious freedom in contexts of varying religious diversity and pluralism, governance systems and human-rights cultures (

Richardson 2006;

Sullivan 2005;

Finke 2013;

Giordan and Pace 2014;

Fokas 2015;

Fox 2015;

Hurd 2015).

Finke (

2013) identified a number of factors influencing religious freedom, namely the presence or absence of one dominant religion, the religious minority/majority nexus, types of formal/informal social and political control, levels of social isolation, and acceptance/rejection of religious rights.

Whether religious freedom is analysed at the governmental-policy level, in reference to the institutionalization of human-rights standards in a particular society, or as a value and element of human-rights culture at the more everyday/lived level, studying it empirically, cross-nationally reveals both theoretical and methodological constraints (

Breskaya et al. 2018). How are we to compare views of religious freedom in various cultural and political contexts when differences are historically rooted and embedded in legal traditions? For example, how do we operationalize “manifestation of religion” if in one country the possibility of praying in school is seen as an individual religious expression and is allowed by the state (

Botvar 2018), and in another it is prohibited because the state considers it a violation of the neutrality of public space (

Breskaya 2017)?

This article aims to compare two social contexts that affect religious freedom in contrasting environments—Belarus and Norway—countries that, prima facie, have more differences than similarities pertaining to religious composition, political conditions and legal frameworks for the implementation of human rights. The presence of a majority religion—Eastern Orthodoxy in Belarus and Lutheran Protestantism in Norway—is a notable similarity. Based on previous research on human-rights attitudes, applying a single-country model of analysis (

Breskaya and Döhnert 2018;

Botvar 2018) and a multiple-country comparison (

Breskaya et al. 2019), we discovered that levels of religiosity, secularism, and trust in institutions affected human-rights cultures both in Eastern-European Orthodox and Nordic countries. We observed that religiosity performs a similar role in understanding women’s rights in all these countries regardless of the differences in religious affiliation, which did not have a strong impact, at least not compared to other factors.

In this article, we present the results of a primary-data analysis comparing the views of young Belarusians (N = 677) and Norwegians (N = 1001) on religious freedom, where we addressed the following research questions:

- (1)

To what extent do religious affiliation, religiosity and spirituality/faith experiences influence views on religious freedom?

- (2)

To what degree does openness to cultural- and religious-diversity contexts affect views on religious freedom?

- (3)

To what degree does trust in institutions in both democratic and non-democratic regimes influence attitudes toward religious freedom?

In answering these research questions, firstly, we set out to assess the arguments of

Modood (

2013) and

Giordan (

2016) by measuring whether levels of religiosity and/or spirituality influence views on religious freedom alongside religious affiliation. Secondly, we were interested in understanding how levels of openness to religious diversity produce various patterns of attitudes towards religious freedom and governance, applying and testing

Richardson’s (

2014) hypothesis about these relationships. Thirdly, we investigated if trust in institutions in democratic and non-democratic regimes leads to pro-religious freedom attitudes drawing on the work of

Devos et al. (

2002). Finally, we discussed the challenges of a two-country comparison

1 on religious freedom in cases where there are significant differences between the countries. To answer these research questions, we have used frequency analysis, t-test, ANOVA, ANCOVA and regression analysis.

2. Theoretical Perspectives

During the last decade, the growing body of literature in social sciences has examined the concept of religious freedom in its diverse dimensions. The complex relationship among religious freedom and legal pluralism (

Richardson 2014), political and legal secularism (

Fox 2015;

Sullivan 2010), multiculturalism (

Modood 2013), social and cultural pressures on minority religions (

Finke 2013), democratic/non-democratic conditions (

Staerklé et al. 1998) and religiosity (

Van der Ven and Ziebertz 2012,

2013;

Sjöborg 2012) was explored. The relationship between religious freedom and religion can also be seen as unilateral, as soon as religious freedom produces the conditions for individualization of religion in liberal democracies. As Tariq

Modood argues (

2013), according to the right to freedom of religion, religion is transformed into “something which the state could not prevent you from professing or worshipping in your chosen way” (

Modood 2013, p. 22). Thus, on the one hand, the principle of religious freedom advances the diversification and variability of choices about religion. On the other hand, practices of religious freedom implementation question the relationship between religious and non-religious actors/citizens as well as between religious majorities and minorities. How do these relationships influence the enforcement of religious freedom ideas in a concrete society, or impede them, and how do religious freedom policies structure majority/minority nexus? These questions become central for the analysis of political secularism and for the study of the meaning of religious freedom in society.

Modood (

2013) noted that:

“Whether the decline of traditional religion is being replaced by no religion or new ways of being religious or spiritual, neither is creating a challenge for political secularism. Non-traditional forms of Christian or post-Christian religion in western Europe are in the main not attempting to connect with or reform political institutions and government policies; they are not seeking recognition or political accommodation or political power”.

This statement emphasizes that political secularism has to be understood in terms of political and government policies, which are separated from the realm of religious and non-religious values and meanings. We are not questioning in this article the way religion intervenes in political arena and the implications of the public role of religion for modern politics, we are interested in considering this statement with socio-religious inquiry—how religious and non-religious identities affect the meaning of religious freedom. What kind of difference, if any, does the identity of belonging to a Christian religious majority, religious minorities or non-religious groups make in relation to views on religious freedom in two different political, religious, and human rights contexts? We will respond to this inquiry with an analysis of the effects of religious identity, religiosity, cultural and religious diversity, and trust in governmental institutions on views about the religious freedom. These concepts seen together allow for differentiating individual religious factors from social context of cultural and religious diversity, and attitudes towards political institutions that will provide us with empirical evidence about the structure of religious freedom views. As

Giordan (

2014) noted, the analysis of a growing religious diversity demonstrates that policies of pluralism lead to “the transformation of the self and of the way of believing” (

Giordan 2014, p. 6) because the individualization of religion produces new forms and patterns of personal engagement with the search of meaning not just accepting “normative answers that come from outside” (

Giordan 2014, p. 6). As well, the concept of spirituality “emerges into the sociological ambit of religion from this context of contemporary pluralism” (

Giordan 2007, p. 162) and “the spiritual perspective” consists of “on the one hand, the gradual establishment of the freedom of choice of the subject, and on the other hand, the experience of diversity and religious pluralism” (

Giordan 2016, p. 201). Thus, understanding the relationship between religiosity/spirituality and cultural and religious diversity will be analysed together in their relationship with religious freedom views.

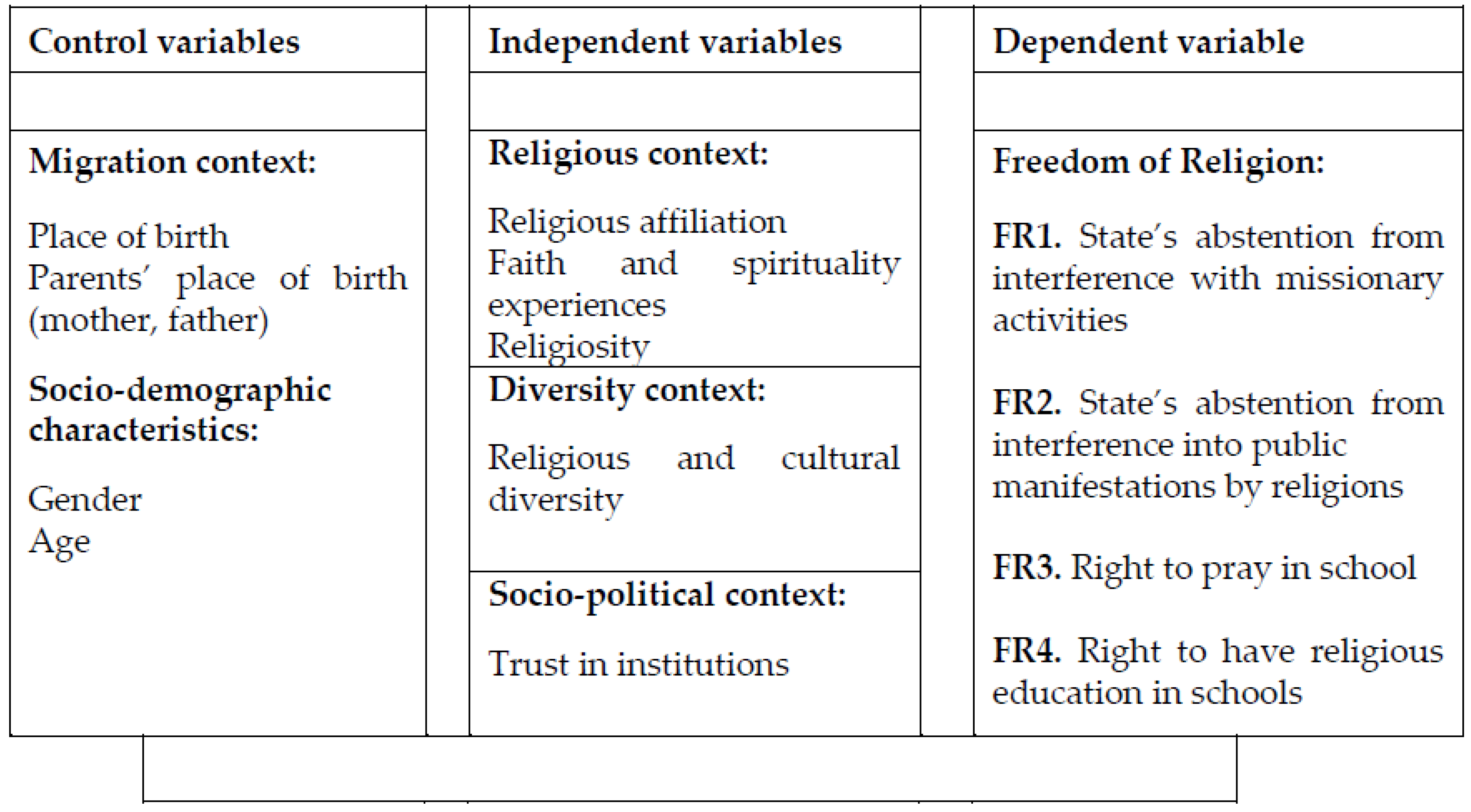

The religious, diversity, and socio-political contexts are conceptualized in this article with the application of theoretical ideas of sociology of religion, sociology of law, and the social representation approach. The religious context of this research implies the concepts of religious identity and religiosity, as well as regards the theoretical discussions on the religiosity and spirituality nexus. The religiosity context is considered in a broader socio-religious perspective in our research. We considered the ongoing sociological debates which discern the concept of spirituality with religiosity in various ways starting from the 1980s. The relationship between the two concepts has been interpreted in terms of changing patterns of relationship with the sacred (

Wuthnow 1998), with complementary modalities not opposed to each other (

Roof 1993,

2003;

Ammerman 2013) or in a mutually exclusive way (

Heelas and Woodhead 2005) with the assumption that the expansion of holistic milieu goes hand in hand with the decrease of the congregational domain. Our article explores the effects of the respondents’ religiosity/spirituality experiences on the perception of religious freedom as a governing principle in two different societies. We are interested in understanding if religious identity, religiosity, and faith/spirituality experiences have a predictive power vis-à-vis the views on religious freedom (negative and positive state obligations) for young people in Belarus and Norway. Moreover, we are interested in analysing how the context of cultural and religious diversity produces various patterns of attitudes towards religious-freedom by applying the socio-legal theory of

Richardson’s (

2014) about the relationship between religious diversity, legal pluralism, and religious freedom. According to this perspective, the societal values supporting openness and flexibility towards religious minorities and welcoming religious diversity, on the one side, and legal pluralism, on the other, have to be taken into consideration together in order to understand how religious freedom functions in a society.

Richardson stated (

2014) that:

If there is openness and flexibility, with religious diversity actually being promoted by a society, then minority groups may be more prone to come into that society, and indigenous religious groups may also be encouraged to develop. If there is a perception that the society is closed and unwelcoming of religious diversity, this may discourage attempts to develop different religious traditions within the society, which also would mean less legal pluralism.

In this perspective, the relationship between religious minorities and religious majority has to be taken into account while the state guarantees religious freedom. Thus, religious freedom implies the integrity of legal and social conditions for its proper functioning in a society.

The socio-political context, conceptualized in this research with the application of social representation theory (

Staerklé et al. 1998;

Devos et al. 2002;

Staerklé et al. 2011), helps us to understand how religious freedom views correlate with the attitudes towards governmental institutions in democratic and non-democratic countries. The analysis of religious freedom with the help of the social representation approach contributes to the sociological study of religious freedom. This approach suggests considering how various social groups construct shared meaning of human rights related to political knowledge and action. Staerklé, Clémence, and Spini stated that “individuals elaborate common understandings of social reality which then enables them to communicate in order to take action on the basis of this shared knowledge” (

Staerklé et al. 2011, p. 760). This approach encourages us to study human rights, including religious freedom, at various levels of national societies as well as cross-nationally, in order to understand how normative principles, inform political and social actions. One specific hypothesis of

Devos et al. (

2002) will be considered for the study of views on religious freedom. The trust in governmental institutions tends to have different predictive power for human rights in democratic and non-democratic countries (

Staerklé et al. 1998) as soon as institutions often “contribute to the preservation and transmission of traditions and ensure the stability and continuity of society” (

Morselli et al. 2012, p. 49). Thus, the analysis of religious freedom in two contrasting political cultures will allow us to test if the degree of trust in governmental institutions has different effects on religious freedom views. In this research, four items construct the dimensions of religious freedom (see

Figure 1). However, these items do not exhaust the meaning of the concept. We follow the operationalization of human rights and the religious-freedom scheme that was established by the international research project, “Religion and Human Rights” (

Van der Ven and Ziebertz 2012,

2013).

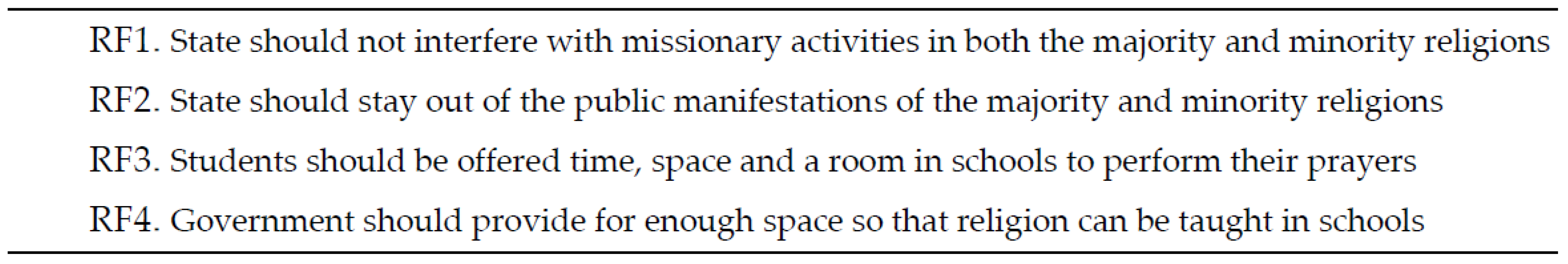

Two items (RF1, RF2) covered the dimension of the state’s negative obligations interpreted as “refrain from interfering in rights” by the European Court of Human Rights’ Guide to Article 9 (

ECtHR Guide to Article 9 2019, p. 19). Two items (RF3, RF4) covered the perspective of the positive obligation of the state concerning religious freedom, i.e., to enable people to practice their belief. For the measurement of the religious-freedom concept, a 5-point Likert-type response scale was suggested.

4. Method, Sample, and Population Description

This study was conducted in the period from 2014 to 2015 in or around the biggest cities in Belarus and Norway within the international empirical research project “Religion and Human rights.”

2 The questionnaire was translated into Russian and Norwegian and submitted to the respondents. For the Belarusian respondents, the online survey system was created by the project coordinating team and students at the undergraduate university level participated in the survey. Participation in the online survey was secured through the individual’s password access. Around 2500 passwords were distributed, and 677 respondents (16–20 years old) completed the survey. With the 11-year secondary education system in Belarus, the age of Belarusian students attending the first and second year of university education is up to 20 years old. This age cohort is comparable with the age of upper secondary school students in Norway. Students, mostly from Minsk, as well as Vitebsk, Brest, Hrodna, Gomel, Mogilev and other smaller towns participated in the online survey. The convenience sample of 677 respondents is analysed in this paper.

In Norway, the sample was collected from 20 upper secondary schools in the Oslo area, on average two classes from each participating school. The survey was conducted in the classrooms, resulting in a response rate of around 90%. The students completed the questionnaires in religious education or social studies classes during the school day, using paper and pencil. Being in the 16–20 age group, the sample is regarded as representative of those attending this public-school level. Most of the respondents had studied the subject of religion and ethics during the year. This probably made them more prepared than other students to answer questions relating to human rights and religion. Due to differences in state regulations and infrastructure, the method for data collection used in Norway is not accessible in a country such as Belarus.

Both Belarus and Norway have a dominant religious tradition: with around eighty-two percent of believers belonging to Eastern Orthodoxy in Belarus

3 and seventy-two percent of the population belonging to Evangelical Lutheran Christianity in Norway.

4 However, the political regime, according to the

Democracy Index 2016, was assessed as “authoritarian” in Belarus and “democratic” in Norway (

Democracy Index 2016). According to the Association of Religious Data Archives (ARDA) Religious Freedom Index Report 2008

5, Belarus had “low freedom,” and Norway had “high freedom, with only one or two minor problems” rating. Yet, the

Government Favouritism of Religion Index demonstrated that the Belarusian state exercised less favouritism towards religious groups compared to Norway (5.2/10 against 6.8/10). Meanwhile, the level of

Government Regulation of Religion had more than ten times greater value of that index in Belarus than in Norway (7.7/10 against 0.7/10).

In the 1990′s, independent Belarus proclaimed adherence to the ideals of the democratic and secular state based on the rule of law. Religious freedom was declared as an inalienable constitutional right of Belarusians. The early 1990′s opened the prospects for the construction of a secular model of governance in which believers were provided guarantees for the freedom of public expression of their views, and religious institutions were granted the freedom to participate in the public sphere. Individual religious freedoms have been guaranteed by the Constitution since 1994. In 2002, the new version of the Act “On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations” contained in its preamble a classification of religions in terms of identity, as “traditional” and “historical” for Belarus. The Orthodox Church was recognized as having the determining role in the historical formation and development of the spiritual, cultural and state traditions of the Belarusian people. To the Catholic Church was prescribed a spiritual, cultural and historical role in Belarus. The Evangelical Lutheran Church, Judaism and Islam were recognized as being of high significance to many of the Belarusian people.

6 By 2018, twenty-five religious organizations were officially registered in Belarus. In Norway, a resurgence of religion in the public sphere took place at the turn of the 21st century, in spite of the country’s widespread secularization. The relationship between church and state in Norway could until recently be described as a state church system. However, in 2012 this system was formally abandoned when the Norwegian Parliament voted to amend the 1814 Constitution. The Lutheran church was a state church up until 2017. Also, under these conditions, the principle of religious freedom was fully implemented in Norwegian law and in constitutional law. The state church system was attacked during later years mainly because of two reasons: (1) the state had the last word when bishops were appointed in the church, and (2) the economic support system was accused of giving privileges to the Lutheran church at the expense of the minority churches and religions. Still today, after the formal abandonment of the state church system the financial system remains the same as before. It is an open question whether the system will change in the future. The main distinction between the old and the new system is thus that the bishops are appointed by church bodies and not by the government. This has led to a discussion about whether the bishops are representing the church members in a good way or not, meaning that there were no major obstacles to religious freedom in the old system and the new system is also imperfect.

The relationship between church and state is still a heated topic of public debate as the majority church retains some privileges compared to other religions in Norwegian society. The state church system favouring the national Lutheran church came under pressure because of the country’s growing religious diversity. The close relationship between church and state was thus seen as problematic vis-à-vis the principle of religious freedom. In recent years, Muslims have become the second largest religious group and today account for about 14% of the population, with Muslims comprising around 30% of the population in the capital of Oslo. When comparing the data related to the country of origin, we see that Norway has a higher score than Belarus. Norwegian society is also more multicultural and religiously diverse than the Belarusian society, with many more young people, and their parents having another country of origin than Norway. This is also reflected in the data concerning religious affiliation.

In Belarus and Norway, the average age of young people who participated in the survey was 18.2 years (see

Table 1). In Belarus, 67% of the online survey respondents were females, while in Norway the ratio of male and female respondents was equal. The migration context for respondents differs in the assessed countries. Among the 677 Belarusian respondents, 56.3% belong to the majority religion, 10.6% to religious minorities, 8.4% to “non-affiliated,” and 24.7% to the non-religious group. Among the 1001 young Norwegians who participated in the survey, 32.2% identify as belonging to the Lutheran Church, 16.5% as belonging to minority religions, 3.9% as belonging to the “non-affiliated” group and 47.4% are non-religious.

The number of respondents whose mothers and fathers were born outside the country was higher in Norway. One-third of the respondents in Belarus and Norway regularly think about religion. Nearly half of the Belarusian respondents have a religious belief and one-fifth express that they practice regular weekly prayer and one-tenth participate in religious services monthly. We observed slightly lower values for religious belief and prayer in the Norwegian sample. However, monthly attendance in religious services has nearly the same value as in Belarus. The experiences of faith/spirituality have greater value in Norway than in Belarus and almost one-fifth of the Norwegian respondents (21%) confirmed that they had experiences of spirituality in their lives.

5. Empirical Findings

In this section, we will present the descriptive statistics of the respondents’ views on the four dimensions of religious freedom, comparing the two countries and reporting on the t-test and ANCOVA analyses for the Religious Freedom Index. Second, we will compare the variance among the religious majority, religious minority and non-religious groups within and across the countries by applying ANOVA. Third, the reliability of different scales for independent variables will be reported. Finally, results of the regression models will be presented for the discussion on the challenges of multiple-country research on religious-freedom views.

5.1. Starting from the Difference: Views on Four Dimensions of Religious Freedom in Belarus and Norway

The empirical data show that support for the three dimensions of religious freedom (RF1, RF2 and RF3) was stronger among Belarusian young people, while RF4 (teaching of religion) was more strongly appreciated in the Norwegian sample (see

Table 2). The mean for the Religious Freedom Index had a slightly greater value (M = 3.13) in Belarus compared to Norway (M = 3.02). Young people in Belarus gave the greatest support to the “negative obligations of the state” (M = 3.36 for RF2 and M = 3.24 for RF1). With respect to Norway, the highest support was given to RF4 (M = 3.47) and RF1 (M = 3.15).

A greater degree of disagreement was noticeable in the Norwegian sample with respect to the RF1 and RF2 categories, which indicates the importance of the regulating role of the state in religious-freedom protection. The greater degree of agreement with these statements was convenient for the Belarusian sample, especially state non-interference with public manifestations of religion (45% against 23.4% in Norway). According to our results, the “Neither disagree nor agree” category occupied the central modality of responses. We found that it was due to the controversy of the religious freedom policy and governance in Belarus and sensitivity to this issue in multicultural Norway. Additionally, we can see that for each item of religious freedom, the level of uncertainty was expressed somewhat more strongly by Belarusian youth than Norwegian youth. Generalizing the answers, we can conclude that for young people in Norway, religious freedom has less uncertain meaning, and religious regulations by the state are supported, especially in the public space, along with support for the significant role of the state in providing religious education. This tendency can be explained by the growth of religious diversity in Norway due to the migration flow and a long-standing practice of teaching religion, even if its content has changed over time (

Botvar 2017), whereas the teaching of religion in public school in Belarus is a subject of special regulations relating to state neutrality (

Breskaya 2017).

The independent-samples t-test was performed to verify the hypothesis that Belarusian and Norwegian young people have statistically significantly different views on religious freedom. There was a significant difference in the scores for the Religious Freedom Index in the Belarusian sample (M = 3.13, SD = 0.696) and in the Norwegian sample (M = 3.02, SD = 0.791); t (1666) = 2.89, p = 0.04. These results suggest that country variance has a statistical effect on religious-freedom views. A one-way ANCOVA was conducted to determine a statistically significant difference between the countries while controlling for religious affiliation. The results showed that there was no statistical effect of countries on religious-freedom views after controlling for religious affiliation, F(1, 1651) = 1.13, p = 0.228. Our first hypothesis (H1), that religious affiliation contributes to the difference in views on religious freedom for majority/minority nexus between the countries has not been proven.

5.2. Religious Affiliation and Views on Religious Freedom: Two Similarities

In this section, we will present the analysis of variances in views on religious freedom among three sub-groups of respondents, affiliated with a religious majority, religious minorities and non-religious youth, so that we can test our second hypothesis (H2). It states that religious affiliation produces the difference in views on religious freedom for majority/minority nexus within Belarus and Norway. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to compare the effect of religious belonging on the Religious Freedom Index. We found that there was a significant effect of religious belonging on the Religious Freedom Index at the p < 0.05 level for the three groups in Belarus [F(2, 674) = 23.28, p = 0.000]. Post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that there was a significant statistical difference between the scores in all three groups when it came to their attitudes to the Religious Freedom Index. However, respondents affiliated with minority religions (M = 3.35, SD = 0.735) had a stronger difference compared to the non-religious (M = 2.84, SD = 0.796) than with those affiliated with Orthodoxy (M = 3.18, SD = 0.589). For the Belarusian sample, a divide in perception of religious freedom could be seen between the religious minority group and the non-religious respondents.

The same analysis was conducted for the Norwegian sample. As in Belarus, we found a significant effect of religious belonging on religious freedom at the p < 0.05 level for the three groups [F(2, 974) = 34.82, p = 0.000]. Post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicate that there was significant statistical difference in variance of attitudes to religious freedom produced by the religious minority (M = 3.36, SD = 0.771) the non-religious (M = 2.83, SD = 0.772) and religious majority (M = 3.08, SD = 0.746). Taken together, these results suggest that the Religious Freedom Index used in this survey produces two similar patterns in both countries:

- (a)

There is a significant statistical difference between the religious majority, religious minorities and non-religious groups in their views on religious freedom.

- (b)

There is a greater statistical difference in scores between non-religious young people and religious minorities than between the religious majority and religious minorities in their attitudes to religious freedom.

This finding enables us to prove that religious affiliation produces the difference in views on religious freedom for the majority/minority nexus within Belarus and Norway (H2 is proved). We can also report a significant divide between religious minority/non-religious youth nexus.

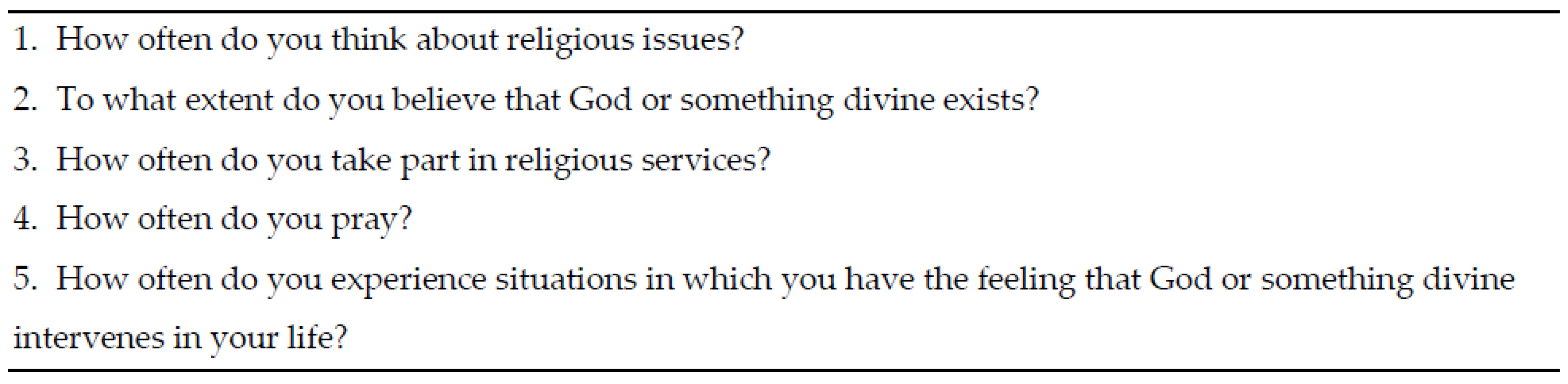

5.3. Religiosity and Faith/Spirituality Experiences

The religiosity of the Belarusian and Norwegian youth had means of 2.52 and 2.18, respectively, which is quite low as the middle category is three (see

Table 3). However, this can be explained by the fact that this is the value for the whole sample that also includes the non-religious students. A one-way ANCOVA was conducted to determine a statistically significant difference between the countries when controlling for religiosity. The results show that there was no statistical effect of the countries on religious-freedom views after controlling for religiosity, F(1, 1643) = 0.04, p = 0.841. Considering these findings, we conclude that the first part of our third hypothesis (H3) has been proven.

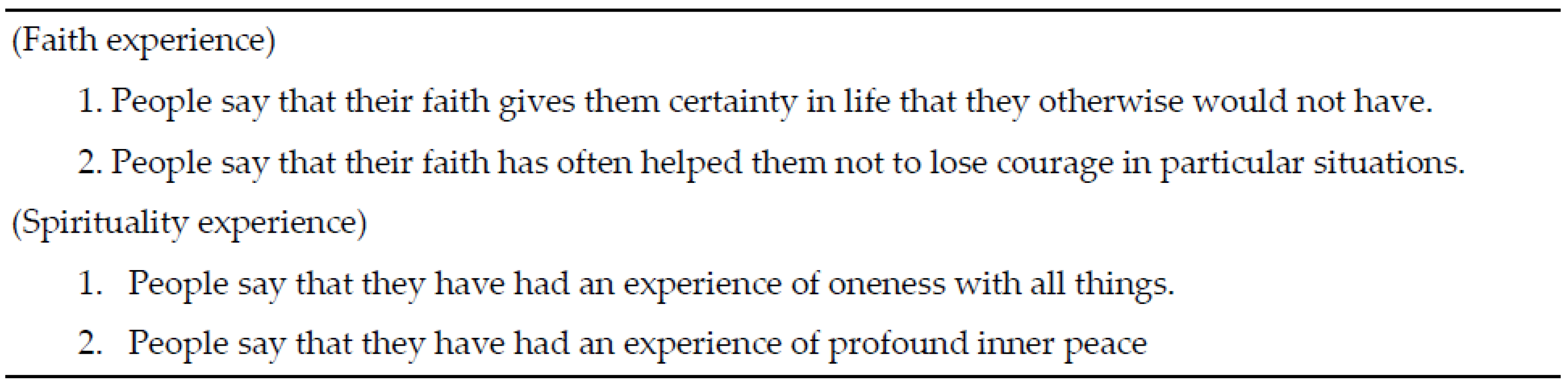

The results of means and standard deviations for the faith experiences had greater value in Norway (M = 3.26) than in Belarus (M = 2.92), as well as for the spirituality experience (M = 2.74 v M = 2.41). This finding shows that experiences of a holistic milieu are more relevant to the Norwegian sample and experiences of the congregational domain are more important for the Belarusian sample. A one-way ANCOVA reveals that there was a statistically significant difference between the views of young Belarusians and Norwegians (country effect) when controlling for spirituality experiences, F(1, 1647) = 16.63, p = 0.000., and faith experiences, F(1, 1652) = 16.63, p = 0.000. Additionally, through using one-way ANCOVA we have observed a significant effect of the majority-religion, minority-religion and non-religious affiliation on religious freedom in Belarus, F(1, 673) = 23.19, p = 0.000, and Norway, F(1, 956) = 13.79, p = 0.000., after controlling for spirituality experiences. Thus, we can conclude that the first part of the fourth hypothesis (H4) is false.

The results of the descriptive analysis of faith/spirituality experience show interesting similarities between the Belarusian and Norwegian samples (

Table 4). The following answers are summarized in this table: 4 = “I often had”; 5 = “I very often had.” Young people belonging to religious minority groups were more likely to admit the presence of faith/spirituality experiences if compared to a religious majority and non-religious youth. One exception is the faith experiences of the religious majority in Belarus, which has a greater frequency value than other groups in the country.

In the two countries, non-religious youth can be compared with the majority and minority religions when it comes to the intensity of faith/spirituality experiences. This observation allows us to consider the relationship of religiosity/spirituality, not only in terms of subjective and individual versus institutional and collective practices but through the common experiences of non-religious and religious young people. As

Heelas (

2008) noted, understanding of the centrality of the experiential dimension for the debate on religiosity and spirituality can help sociologists to deal with the ambiguity of the spirituality concept. We also consider that the modalities of spirituality experiences for young people in Belarus and Norway are produced by the accompanying “cultural packages” (

Ammerman 2013) that can have different socio-cultural meanings in countries with Eastern Orthodoxy and Lutheran Protestantism.

5.4. Cultural Diversity and Trust in Institutions

For the general samples (see

Table 3), diversity was more appreciated in Norway (M = 3.91) than in Belarus (M = 3.49). A one-way ANCOVA revealed a statistically significant result: views on religious freedom were statistically different between the three groups (majority, minority, non-religious) when controlling for diversity in Belarus, F(1, 673) = 25.88, p = 0.000, and in Norway, F(1, 973) = 41.92, p = 0.000. If controlling for diversity, the country effect (Belarus, Norway) was statistically significant as well, F(1, 1664) = 28.70, p = 0.000.

We also had similar statistically significant results for the trust in institutions concept while testing the effect of the religious affiliation (with majority, minority, non-religious groups). Results from a one-way ANCOVA showed that the difference in religious-freedom views was statistically significant between the three groups when accounting for trust in institutions, F(1, 673) = 29.79, p = 0.000 (for Belarus), and F(1, 971) = 38.34, p = 0.000 (for Norway). Additionally, the countries had statistical differences in views on religious freedom when controlling for trust in institutions, F(1, 1663) = 4.98, p = 0.026.

Table 5 shows the reliability of all independent variables which were used in a regression analysis for the religious-freedom concept. All the variables fulfil the criterion for acceptable reliability, except one. The value of the Cronbach’s alpha is slightly below the minimum value of 0.60 for only the cultural diversity scale. However, we considered accepting the diversity scale for further regression analysis as the reliability value is slightly different from the conventional criteria.

5.5. Regression Analysis

The regression model (

Table 6) explains 20% and 25% of the variances in the dependent variable in the Belarusian and Norwegian samples, respectively, which is an average in social sciences. In two samples, the residuals showed random patterns, suggesting that both models were systematically correct. For Belarus and Norway in our samples, the similar variables which had the strongest predictive power for the religious-freedom views were religiosity (positive), diversity (positive) and gender (positive). Trust in institutions has strong predictive power vis-à-vis the views on the Religious Freedom Index however, with opposite directionality in the assessed countries—with a negative effect for Belarusian youth and a positive effect for young people in Norway.

Our research questions were related to three contexts (religious, diversity, and trust in institutions) and attitudes to religious-freedom views. The empirical analysis shows that from the religious-context point of view, religiosity predicts support for religious freedom; however, the majority/minority nexus has almost no predictive power. Only in one case in the Belarusian data did we observe that the Orthodox youth agreed significantly more strongly with religious freedom than non-religious respondents (beta = 0.119). Moreover, spirituality experiences had a significant influence on religious-freedom views in Belarus (beta = 0.111). As for the diversity and socio-political contexts, we can conclude that two concepts (diversity and trust in institutions) contribute to the model and have a significant influence on how young people address religious freedom in society. We conclude that the statistical analysis proves four hypotheses out of six. However, some aspects still require more detailed discussion. The controlled variables relating to the migration context have no effect, while gender is a significant predictor. Females are more supportive of religious freedom, which is most relevant for the Belarusian sample. However, age in Norway has a negative effect on the dependent variable which can be explained by the tendency of less importance of religious expression for those who become non-religious with the ages.

6. Conclusions/Discussion

In this article, our aim has been to compare two contrasting social contexts and analyse the implications they have for religious-freedom views. Considering the limitations of our sampling methods and comparing the area-sample with the convenience sampling, we found that the validity is limited to this population. However, it was possible to identify similar patterns of statistically significant relationships between the variables in the perspective of future studies with the representative samples. The authors are also aware of the ongoing debate on the validity of using the means scores and parametric analyses for the Likert scale data. However, there is evidence that parametric tests can be used with ordinal data, such as data from Likert scales (

Norman 2010;

Sullivan and Artino 2013). Some experts assert that if there is an adequate sample size (at least 5–10 observations per group), and if the data are normally distributed (or nearly normal), parametric tests can be used with Likert scale ordinal data (

Jamieson 2004).

Applying the statistical methods, we confirmed the difference between Belarus and Norway when it comes to views on religious freedom. The first research question: to what extent do religious affiliation, religiosity and spirituality/faith experiences influence the views on religious freedom was examined according to four hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H4). We found that religious affiliation does not produce this difference between the countries (H1 is false). However, we observed similar internal country dynamics for religious affiliation. In Belarus and in Norway, the statistical differences were greater between non-religious young people and religious minorities than between the religious majority and religious minorities when it came to views on religious freedom (H2 proved with specification). This finding makes it clear that comparing different countries gives us a better understanding of the differences in religious-freedom culture and also in views towards religious governance, than do single-country analyses.

Moreover, the finding related to the religious minority/non-religious youth nexus allows us to consider

Modood’s (

2013) theoretical arguments about the (lack of) implications religious and spiritual traditions have on political secularism. According to our results, religious freedom policy and religious-governance principles are considered differently by groups with non-religious and religious affiliations. This means that greater attention needs to be given to the contrasts between these two groups and the tensions between them. Finally, our finding shows that studies on religious freedom that have paid attention to organized religion and lived religion (

Hurd 2015) have to be sensitive also to the non-religious category.

Furthermore, our research has confirmed that religiosity produces no difference in religious-freedom views between the countries (the first part of H3 proved) and the regression analysis gave us evidence that religiosity had a significantly positive influence on religious-freedom views in both countries (the second part of H3 proved). Again, the similarity between the countries shows that regardless of religious traditions and the religion-state relationship religiosity (being the most robust predictive variable in our model) is an important explanatory factor vis-à-vis the governance of religious freedom.

The empirical findings show us that the faith/spirituality experiences factor is slightly more important among Norwegian youth than among Belarusian. Religious minority groups in both Belarus and Norway confirmed that they had more experiences of spirituality than other groups. The faith/spirituality experiences produce differences in views on religious freedom both between and within each country (the first part of H4 is false). The predictive power of spirituality experiences on religious-freedom views is significant only for the Belarusian sample, not the Norwegian one (the second part of H4 is proved for Belarus only). We know from the regression analyses that we performed for each group separately and for each item from the Religious Freedom Index, that spirituality is the significant predictor for RF3 (possibility to pray in school) for the religious minorities in the two countries. These findings provide us with evidence that in countries with different religious-freedom records, the concept of spirituality produces different effects on religious freedom. Considering the relevance of the spirituality concept for religious freedom (

Giordan 2007,

2016) and evaluating H1, H2, H3, H4, we can conclude that the religious context matters and that faith/spirituality experiences have an impact on how religious and non-religious youth understand the governing principles of religious freedom.

The second context—of cultural diversity—has a strong predictive (positive) effect in Norway and Belarus (H5 proved). Thus, religious governance can be seen in parallel with religious self-governance as being dependent on religious diversity (

Richardson 2006,

2014). Diversity produces differences between the countries and within the three groups of religious affiliation regarding the religious-freedom views. Moreover, we observed that diversity is more appreciated in Norway than in Belarus.

The third context, socio-political environment measured by trust in institutions, has a positive influence on religious-freedom views in Norway and a negative influence in Belarus. This means that the hypothesis of

Staerklé et al. (

1998) and

Devos et al. (

2002) related to trust in institutions (H6) is supported. This demonstrates a relationship between democratic/non-democratic regimes and support for religious freedom. This finding also questions the role of democratic and non-democratic populations in the human rights protection questioning if the strong negative impact of trust in institutions on religious freedom views has to be seen together with the less responsibility for human rights by citizens as they rely more on the state responsibility in human rights issues. As

Staerklé et al. (

1998) explained, in democratic societies citizens “should be considered more responsible for the respect of human rights than the government” (

Staerklé et al. 1998, p. 211). This statement allows us to understand better the different degree and opposite effects of trust in institutions in Belarus and Norway.

In our study, the comparison between Belarus and Norway applied both deductive and inductive approaches (

Anckar 2008). By testing the theoretical hypotheses and using explorative research strategy, we found similar patterns in religious-freedom views in two very different countries both culturally and politically. When we find similar patterns of relationship between independent variables and religious-freedom views in such different countries, we can conclude that it is likely that the findings are relevant also for other countries. Finding similar patterns in varying contexts make the results more valid and secure. Nonetheless, more research on the relationship between socio-political and socio-religious contexts and views on religious freedom is important for a better understanding of observed patterns in other religious and political contexts of religious freedom governance. Hence, there is a necessity of further analytics work in the area of conceptualization of religious freedom in empirical sociological studies. Furthermore, finding three similarities in different cultural contexts hints at a youth culture that is somewhat universal/international across religious and political borders and that the idea of religious freedom transcends governance models. Religious freedom is a complex social phenomenon that integrates individual religious autonomy and engagement, and which requires a welcoming diversity culture and trust in governing institutions.